Abstract

Research on entrepreneurial intentions, as an important step in the decision to undertake an entrepreneurial career, tends to position career actors as choosing entrepreneurship as a first career decision. However, most scholars agree that entrepreneurs emerge from existing organizations, not from college dorm rooms. Therefore, individuals choosing to enter entrepreneurship typically do so after having made previous career decisions to work in paid-employment careers. Despite the usefulness of the accumulated knowledge of individual and contextual antecedents to entrepreneurial intentions, few studies offer a careers theory-based explanation for why some people who have previously decided to pursue paid-employment careers view moves to entrepreneurial careers as feasible and desirable as proposed by entrepreneurial intentions-based models. In this paper, we extend boundaryless and protean career orientations, established theoretical career concepts, to explain the entrepreneurial intentions of actors already working in wage-employment careers. Our theoretical integration sheds new light on entrepreneurial intentions research and fills important gaps in our understanding of the mindsets of those inclined towards entrepreneurial careers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Entrepreneurship through new venture creation is a key driver of economic growth and prosperity in both developed and emerging contexts (Carree and Thurik 2003; Van Praag and Versloot 2007). As such, scholars focus a great deal on uncovering predictors, especially of a psychological nature, of individual inclinations towards careers as entrepreneurs (Do Paço et al. 2015; Frese and Gielnik 2014; Mitchell et al. 2007; Zhao et al. 2010). Examinations of these cognitive underpinnings often analyze samples of individuals who have yet to make their first career decisions (Kolvereid and Isaksen 2006). These studies have significantly increased our understanding of “how entrepreneurs think” (Mitchell et al. 2007 p. 3) differently than other people in terms of career motivations and drivers to begin entrepreneurial careers (Henderson and Robertson 2000). However, recent evidence suggests that in fact most entrepreneurs do not emerge directly from college dormitories but from organizations (Sørensen and Fassiotto 2011). Thus, the vast majority of individuals thinking about undertaking new venture creation are not making first career decisions, suggesting a need for greater understanding and insight into the cognitive processes shaping these career moves.

Career theory suggests that individuals make important career decisions based in part on their orientations or views of careers. A career orientation refers to the “career values and attitudes such as preferences regarding self-determination, advancement, mobility, organizational support, and security” (Tschopp et al. 2014, p. 152) of individual career actors. “New career theory” offers career orientation conceptualizations that allow the career actor a greater role in determining career paths (Reitman and Schneer 2008). For example a protean career orientation refers to an “individual’s attitude towards developing his/her own definition on what constitutes a successful career” and being motivated to achieve success even in the face of a change environment (Gubler et al. 2013, p. 23). Likewise, a boundaryless career orientation is characterized by a view that organizational and career boundaries “can be transcended” (Briscoe and Finkelstein 2009, p. 243).

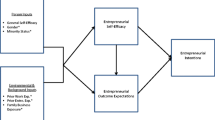

While initial preferences for certain types of work may drive initial career decisions, career orientations often evolve through career experiences and changing life experiences (Rodrigues et al. 2013) and are therefore useful in evaluating decisions beyond first career choice intentions. For example, these “new career” views are have been used to explain career decisions involving intentions to quit or leave an organization (Skromme Granrose and Baccili 2006; Supeli and Creed 2016), remain with an organization (Briscoe et al. 2012), retire (De Vos and Segers 2013), change employers and/or careers (Hess et al. 2012), and reject future employment opportunities (Gubler et al. 2013). As such, we argue these concepts are useful in explaining and predicting the intentions of individuals to move from paid-employment to entrepreneurship. Existing cognitive, intentions-based models of entrepreneurial intent have been criticized for lacking a career actor agentic component that explains how individuals navigate their own careers (Townsend et al. 2015). In this regard, boundaryless and protean career orientations emphasize individual agency in their cognitive properties focusing on how career decision making is primarily under individual control (Tams and Arthur 2010). Hence, the theoretical model put forth in this paper posits that wage-employed individuals considering moves to entrepreneurship who hold boundaryless and protean career orientations are more equipped to perceive feasibility and desirability in moving from wage-employment to entrepreneurship than those with other career views (See Fig. 1). We conceptually link these orientations with the desirability and feasibility components of other entrepreneurial intentions-based models. Further, we explore a few of the possible wage-employment experience boundary conditions such organizational tenure and organizational culture on the proposed relationships.

Certainly, the study of both entrepreneurial intentions and career orientations has been fruitful and useful; however, important questions remain. This paper attempts to provide answers to some of these questions through a career-theoretical lens (e.g., Liguori et al. 2018) and in doing so makes important theoretical contributions to entrepreneurship research. First, while the protean and boundaryless career orientations have been suggested by some scholars as related to entrepreneurial careers (Mallon and Cohen 2001; Marshall 2016; Van Gelderen et al. 2008) few, if any, have conceptualized their relationships with the entrepreneurial intentions of wage-employed career actors. In doing so, we offer a careers-based model for understanding entrepreneurial intentions in a more realistic careers context; after making previous career choices. Second, we answer recent calls by scholars for more theoretical integrations, interaction explorations, and contextual understanding of entrepreneurial intentions (Krueger 2009; Fayolle and Linan 2014; Schlaegel and Koenig 2014). By conceptualizing the effects of career orientations and entrepreneurial intentions of those who have previously made career choices, we begin to understand how one’s view of a career interacts with work experiences and other work factors to influence the some people, but not others, to pursue new venture creation (Lee et al. 2011). Third, our model offers a conceptualization of entrepreneurial intentions that emphasizes career actor agency missing in previous cognitive approaches to understanding entrepreneurial intent (Townsend et al. 2015). Fourth, from a practice standpoint, our model may help individuals thinking about making a career change to entrepreneurship to recognize their own cognitive limitations associated with career boundary crossing and career self-management and motivate them to either remain in careers more closely aligned with their career views or develop capabilities necessary for making major career transitions.

The paper proceeds with a brief review of the entrepreneurial intentions and career orientations literature. We then explain how prevailing theories of entrepreneurial intentions relate to “new career” perspectives (Briscoe and Finkelstein 2009), and propose relationships between protean and boundaryless career orientations and entrepreneurial intent for individuals already working in paid employment settings. We then draw on entrepreneurial learning theory, self-efficacy, and the concept of embeddedness to conceptualize how work experiences might influence the relationship between one’s career orientation and view of a career and the intentions to pursue entrepreneurship. We conclude with implications and future directions for research.

Literature review

Entrepreneurial intentions

Entrepreneurial intentions represent inclinations to engage in the venture creation process and embark on an entrepreneurial career (Krueger 2009). Researchers have demonstrated that entrepreneurial intentions are robust predictors of future entrepreneurial behaviors and actions (Ajzen et al. 2009; Carsrud and Brännback 2011). Successfully borrowing theories from other fields such as psychology and sociology, scholars laid the groundwork for considerable research concerning the cognitive processes of enterprising individuals by exploring these entrepreneurial intentions (Krueger et al. 2000). Hence, the study of entrepreneurial intentions typically follows a theoretical framework based on the theory of planned behavior (Ajzen 1991) and/or the entrepreneurial event model (Shapero and Sokol 1982). These frameworks explain that intentions are driven, in part, by attitudes toward the intended entrepreneurial behavior. Thus, favorable attitudes toward entrepreneurial career moves are influenced by individual perceptions of desirability and feasbility regarding entrepreneurial career entry.

The degree to which one is interested in, and attracted to, entrepreneurship represents perceived desirability (Shapero and Sokol 1982). Perceived feasibility refers to one’s belief that resources (both physical assets and human capabilities) can be acquired to undertake new venture creation (Shapero and Sokol 1982). Feasibility can also represent the cognitive properties of an individual career actor to include perceptions of control over making career decisions stemming (Krueger et al. 2000). In our model, we contend that favorable attitudes (desirability and feasibility) toward entrepreneurial career and the development of entrepreneurial intentions are shaped by career orientations of potential entrepreneurs emerging from existing wage-employment career contexts.

Career orientation

A career involves both observable work activities and non-observable attitudes toward work behaviors (Gunz 1988). A major part of attitudes toward work behaviors are career orientations. Career orientation is a reflection of an individual’s attitudes and preferences toward a career type (Gerber et al. 2009). The historical approach to career orientation involves the perception of the organization as the driving force of one’s career path such that an individual believes that career development and progression is achieved primarily through organizational hierarchies (Reitman and Schneer 2008). This approach however, has generally lost favor in the career literature, giving way to more self-directed and self-managed career attitudes, which characterize protean career orientations (Hall 1976). The protean career orientation represents greater independence from organizational career hierarchies in order to achieve career success and satisfaction (Baruch 2004) and in making career change-decisions (Hall 1996). A career actor holding a protean orientation is more ready and willing to adapt to forced career changes and more open to voluntary career changes (Briscoe and Hall 2006).

Another advancement in career theory is the concept of a boundaryless view of careers. While this view of careers can refer to a particularly broad career perspective through which scholars and practitioners explain career movements, it also refers to a specific individual mindset toward career decision making and trajectory (Briscoe and Finkelstein 2009). This orientation represents perceptions of career paths that cross various organizational and employment boundaries (Arthur and Rousseau 1996). A boundaryless view also describes an individual’s psychological mindset, in which reaching across organizational boundaries to develop working relationships with others is desirable (Briscoe et al. 2006). Together, the protean and boundaryless career orientations represent the “new career” concept (Briscoe and Finkelstein 2009).

Career orientation and entrepreneurship

Historically, individuals who undertook new venture creation were thought to have embarked on an entrepreneurial career. The entrepreneurial career has generally been viewed as a separate career choice, distinct from more common career descriptions (Dyer 1994). Within this view, the study of entrepreneurial intentions has focused mainly on the determinants of entrepreneurship as an end-state career choice (Carroll and Mosakowski 1987; Baron 1998; Krueger et al. 2000; Townsend et al. 2010; Zellweger et al. 2010). While it is true that some individuals do spend their entire careers in entrepreneurship, there are hosts of individuals who experience new venture experience in disparate “chunks” of time throughout the duration of their careers (Henderson and Robertson 2000).

An entrepreneurship decision is a career choice much like any other vocational decision. Moreover, for many people, entrepreneurship is not a decision made solely at the beginning of one’s career. Rather, some individuals begin their working lives as entrepreneurs but move into paid employment for a variety of reasons (Parker and Belghitar 2006), while others move from paid employment into entrepreneurship for other reasons (Dawson and Henley 2012). The point, is that entrepreneurship as a career choice is not typically a static, final career move, but a dynamic phase in one’s overall career path (Hytti 2010). Significant research explains many of the drivers of entrepreneurial career choices (Henderson and Robertson 2000; Douglas and Shepherd 2002; Carter et al. 2003; Zellweger et al. 2010). All of these factors point to the notion that a person’s desire to pursue entrepreneurship may change over time; before or after periods of paid employment, suggesting the need to identify the entrepreneurial intentions of individuals at different points in their careers as their career orientations and views may change.

Protean career orientation

A protean career orientation relates well to the concept of entrepreneurship. An individual with a protean career orientation relies heavily on individual motivation and determination in order to progress and succeed in a career (Gubler et al. 2013). Likewise, the entrepreneur is almost completely self-reliant for opportunity recognition and new venture creation (George et al. 2016; Sexton and Bowman 1986). Additionally, the entrepreneur must rely heavily on self-motivation and determination in order to be successful. Therefore, the self-directed and self-managed nature of the protean orientation as it relates to entrepreneurial intentions is explained by the positive attitude toward entrepreneurial behavior construct of the theory of planned behavior (Kautonen et al. 2013). The attitude of an individual with a protean orientation toward self-management also drives perceived feasibility of entering entrepreneurship as individuals who are used to relying on themselves to move their careers forward may see greater feasibility in pursuing an entrepreneurial career in which self-reliance is key to success (Sexton and Bowman 1986).

Beyond the self-directed and self-managed attitudinal linkage of protean career orientations and entrepreneurial intentions through perceived feasibility, entrepreneurship provides a vehicle for protean individuals to fulfill their value-driven view (Van Gelderen et al. 2008). Individuals with protean career orientations are driven by their own value systems rather than the value sets of others such as the organization (Briscoe et al. 2006), and entrepreneurship allows an individual to completely express their own values. For example, an individual possessing a protean orientation may be driven more by challenging, autonomous, and self-fulfilling work as opposed to typical measures of career success such as compensation or benefits (Segers et al. 2008; Reitman and Schneer 2008). This component of the protean orientation aligns with the perceived desirability construct of the entrepreneurial event model as an individual driven by self-expression and self-fulfillment may desire a context, such as entrepreneurship, to fully realize these values.

Proposition 1

A protean career orientation will positively affect entrepreneurial intentions via perceptions of desirability and feasibility regarding entrepreneurial career entry.

Boundaryless career orientation

Entrepreneurship as a career move or transition relates well with the boundaryless career orientation. While most discussions of a boundaryless career orientation are characterized by attitudes favoring inter/intra firm mobility (Inkson et al. 2012), it also describes positive mindsets toward transitions to and from entrepreneurship (Cohen and Mallon 1999; Van Gelderen et al. 2008). An individual employing a boundaryless view does not feel dependent on, or constrained by, traditional career boundaries such as continuous work within wage-employment settings which drives both the perceived desirability and feasibility of future entrepreneurial behaviors. Indeed, studies of boundaryless careers often involve an element of entrepreneurship such as the entrepreneurial culture of boundaryless technology professionals in Silicon Valley (Arthur and Rousseau 1996) or a transition to a “portfolio career” (Cohen and Mallon 1999). Additionally, boundaryless orientations are characterized by autonomous mentalities, which motivate attitudes toward crossing organizational and employment boundaries (Bird 1994) in order to work with others. Furthermore, entrepreneurial careers are typically highly autonomous such that an entrepreneur must establish important social networks in order to accomplish entrepreneurial activities (Greve and Salaff 2003).

The pursuit of entrepreneurship involves an inherent risk in leaving the potential security offered within an organization (Simon et al. 1999). However, a boundaryless attitude likely reduces this perceived risk thereby increasing the perceived feasibility of leaving paid employment for entrepreneurship. In other words, an individual with a boundaryless mindset will feel unconstrained by employment boundaries and perceives greater feasibility of entrepreneurial entry than someone without a boundaryless view. In this way, a boundaryless orientation provides an individual with a self-confidence, or potentially even overconfidence, in the ability to move freely between paid and entrepreneurship, reducing the percieved risks and increasing perceived feasibility of new venture creation. For example, an individual may believe that based on their self-investments (education, work experience, or strong social network ties), they will be able to move back to paid employment if their new venture fails (Marshall 2016).

Proposition 2

A boundaryless career orientation will positively affect entrepreneurial intentions via perceptions of desirability and feasibility regarding entrepreneurial career entry.

Protean and Boundaryless orientations interaction

Despite the empirical and conceptual distinctions between protean and boundaryless orientations (Briscoe et al. 2006), many scholars often refer to them together in discussing new career theory. In a similar nature, we propose that these orientations interact and reinforce each other in driving the desirability and feasibility attitudes leading to entrepreneurial intentions. Prior research supports a reinforcing nature between these constructs as well. For example, studies show that an individual with a self-directed orientation may demonstrate some boundaryless attributes by working in several different organizations in order to achieve personal goals and values (Baruch 1998). Additionally, an individual with a boundaryless view may rely on autonomy and self-direction in order to reach across organizational boundaries and work with others (Briscoe et al. 2006; Segers et al. 2008).

As such, career actors with boundaryless orientations likely see greater desirability and feasibility of future entrepreneurial entry if they also possess a protean orientation. A boundaryless orientation makes entrepreneurship as a career more feasible in believing that few boundaries exist which might prevent entry but the protean, self-direction attitude strengthens boundaryless perceptions and provides greater preparation and readiness to move beyond employment boundaries. Furthermore, a boundaryless attitude towards careers is useful in reinforcing and allowing a protean-oriented individual to cognitively explore self values. For example, an individual with a protein orientation may be limited in expressing individual values because they percieve employment boundaries as restrictive. However, a boundarlyess mindset is freeing of these restrictions thereby opening up the mind of the career actor to consider entrepreneurship as a means through which values can be expressed.

Proposition 3

Protean and boundaryless career orientations will interact to strengthen each construct’s impact on entrepreneurial intentions via perceptions of desirability and feasibility regarding entrepreneurial career entry.

Moderating effects of wage-employment work experiences

Because most entrepreneurs are employed in wage-employment contexts first, it is important to consider how certain elements of wage-employment experiences shape individual career orientation-entrepreneurial intentions relationships. Additionally, entrepreneurial intentions are, at least somewhat, socially constructed and it is likely that experiences associated with wage-employment will influence the degree to which individual career orientations shape intentions for entrepreneurship. For example, previous studies point out that the knowledge and abilities gained through certain types of wage-employment such as small business or startup experiences can increase entrepreneurial intentions (Quan 2012; Politis 2005). Other studies show that many entrepreneurs gain certain industry expertise through their work experiences which may result in break-off ventures (Fritsch and Falck 2007; Politis 2005). More specifically, research shows that workplace peers (Nanda and Sørensen 2010), bureaucracy (Sørensen 2007), culture-person fit (Lee et al. 2011), prior corporate job rank (Quan 2012), managerial experience (Kim et al. 2006), and job satisfaction (Cromie and Hayes 1991) are all important work experiences influencing inclinations toward entrepreneurship.

While these studies certainly demonstrate the link between wage-employment work experiences and potential for entrepreneurship, they do not explain how work experiences interact with an individual’s own career attitudes in driving entrepreneurial intentions. Therefore, in our model we argue that organizational climates and tenures are critical elements affecting career orientation-intentions relationships. Similar to the approach taken by some researchers to explain the development of entrepreneurial expertise, we propose that entrepreneurial work experience (climate and tenure) act as “critical development experiences” (Krueger 2007) in shaping relationships between career orientation and entrepreneurial intentions.

Organizational climate of individual empowerment

Organizational climate refers to the shared perceptions of organizational members concerning the employee attitudes and behaviors that organizational leaders desire (Schneider and Reichers 1983). In other words, through policies, procedures, directions, and reward systems, organizational leaders encourage and emphasize the attitudes and behaviors of employees in specific ways. For example, some organizations highlight innovation and creativity which may lead to the development of entrepreneurial intentions (Lee et al. 2011). In our study, we focus on organizational climates which emphasize self-direction and empowerment because of the close relation to boundaryless and protean career attitudes. We posit that climates accentuating self-management concepts are likely to strengthen the effects of boundaryless and protean career orientations on the desirability and feasibility of entrepreneurial entry.

An organizational climate of individual empowerment reflects a high level of information sharing, autonomy, and accountability (Blanchard et al. 1995). When managers expect employees to share critical insights, important learning, and other knowledge and abilities with one another, members within an organization are better equipped and informed to make important decisions (Seibert et al. 2004). When individuals work in organizations that empower them through important knowledge sharing activities, it is likely that boundaryless and protean career orientations can more effectively lead them to see feasibility and desirability in entrepreneurial careers. As noted earlier, the very nature of entrepreneurial work is self-directed; meaning that entrepreneurs rely heavily on themselves for a variety of tasks including decision-making (Busenitz and Barney 1997) and therefore, when organizations encourage similar behaviors, the self-directed and self-managed career elements of boundaryless and protean orientations are reinforced in driving entrepreneurial intentions.

Climates that empower individuals also provide conditions through which employees can engage in autonomous decision making. When organizations set clear expectations and foster cooperation and teamwork in the workplace, employees are empowered to make autonomous decisions without a great deal of guidance or direction from others (Seibert et al. 2004). As such, individuals with protean and boundaryless career orientations employed in these types of organizations are experienced in relying on their own thinking to make important decisions. In particular, protean attitudes which deemphasize reliance on organizational structures for career advancement which motivate desires for entrepreneurial behaviors are strengthened under conditions of high organizational autonomy.

Furthermore, organizational climates which give rise to individual empowerment reflect patterns of employee accountability in decision making situations. That is to say, employees perceiving empowerment climates in their organizations believe organizational leaders hold them responsible for their actions (Seibert et al. 2004). As individuals make autonomous decisions and are held responsible for their actions, they develop confidence in their own abilities and greater trust in their own instincts and decision-making capabilities (Zhang and Bartol 2010). For these individuals the transition to entrepreneurial careers likely becomes more feasible and desirable given their beliefs in abilities to make critical career decisions and engage in entrepreneurial behavior. Thus, organizational empowerment climates can strengthen boundaryless and protean attitudes directed towards entrepreneurial careers and enhance the feasibility and desirability of such.

Proposition 4a

Organizational empowerment climate moderates the relationship between protean career orientations and entrepreneurial intentions via perceptions of desirability and feasibility of entrepreneurial career entry such that the relationship will be more positive under conditions of high empowerment climate.

Proposition 4b

Organizational empowerment climate moderates the relationship between boundaryless career orientations and entrepreneurial intentions via perceptions of desirability and feasibility of entrepreneurial career entry such that the relationship will be more positive under conditions of high empowerment climate.

Wage-employment tenure

While a career orientation may be an underlying mechanism guiding entrepreneurial intentions, the effects of prior career choices should not be ignored. In particular, the length of time an individual has been a wage-employee can significantly shape their future career choices (Mitchell 1981). Research regarding employment tenure and career moves (here we consider the turnover literature to be representative of a career move) generally considers elements such as organizational commitment (Jaros 1997), job satisfaction (Tett and Meyer 1993), and switching costs (Mitchell et al. 2001). However, the career orientation-entrepreneurial intentions relationship eliminates these arguments, as protean and boundaryless individuals are less concerned with these constraints.

Some models of employee career change take into account the fact that some employees leave their jobs for reasons beyond low job satisfaction or commitment such as for new opportunities (Lee and Mitchell 1994) or for non-work, life reasons (Lee and Maurer 1999). These models tend to more accurately align with an entrepreneurial learning perspective; the intention to start a business is not influenced so much by a dissatisfaction with wage-employment but by the amount of entrepreneurial learning and experience that has increased the individual’s positive attitudes (desirability and feasibility) toward entrepreneurial careers thereby increasing entrepreneurial intentions.

Even for individuals possessing a protean orientation and boundaryless view, it may take some time to gain the experience, knowledge, and ability that allows them to determine that they may be suited for an entrepreneurial career and also well-equipped for entrepreneurial engagement. For some, this may come early in a career, for others, quite later. Indeed, there exists a great deal of literature regarding more experienced and higher-aged workers and entrepreneurial intentions (Singh and DeNoble 2003). While those with protean and boundaryless views may, at any time during their wage-employment careers transition into entrepreneurship, we argue that the effects of career orientations on entrepreneurial intentions is most probably during early to middle stages of wage-employment careers. In other words, we anticipate that protean and boundaryless career orientations drive entrepreneurial intentions most strongly for people with minimal time spent in wage-employment careers. We ground this argument in organizational/job embeddedness theory (Mitchell et al. 2001).

The embeddedness concept describes an individual’s link to people within organizations and occupational employment types, and the fit between employment and personal life (Mitchell et al. 2001). As individuals progress in their wage-employment tenures, they become increasingly attached to, and embedded in, their careers and employing organizations. It is likely that embedded employees, despite protean and/or boundaryless orientations, set aside desires for new venture creation until eventual retirement from current wage-employment careers. However, we have argued that a great deal of entrepreneurial learning takes place during one’s tenure as well. Early stage employees may have no intentions of entrepreneurship until a sufficient amount of knowledge and abilities have influenced self-efficacy regarding new venture creation, or career views have changed. Therefore, we posit a wage-employment tenure, curvilinear influence on the relationship between career orientations and entrepreneurial intentions such that the early and middle stage tenure will strengthen the relationship until a certain point in which the effect levels out or actually weakens the relationship.

Proposition 5a

Wage-employment tenure moderates the relationship between protean career orientations and entrepreneurial intentions via perceptions of desirability and feasibility regarding entrepreneurial career entry in a curvilinear manner.

Proposition 5b

Wage-employment tenure moderates the relationship between boundaryless career orientations and entrepreneurial intentions via perceptions of desirability and feasibility regarding entrepreneurial career entry in a curvilinear manner.

Discussion

Studies seeking to explain entry into entrepreneurial careers through examination of entrepreneurial intentions typically rely on conceptualizations and data samples of individuals making initial or first career choices. However, most people entering entrepreneurship do so after having decided to work in wage-employment careers. The conceptual model of entrepreneurial intentions presented in this paper reconciles this flawed assumption positioning the career actor as having already made initial career decisions to enter wage-employment and have inclinations or aspirations to move to entrepreneurial careers. We proposed that individual cognitive concepts associated with “new career theory” offer an explanation of entrepreneurial intentions capable of explaining decisions to enter entrepreneurship not from the college dorm room but from existing organizations. Specifically, we argued that boundaryless and protean career orientations allow career actors the agency and capabilities necessary for viewing entrepreneurial careers as feasible and desirable.

Accordingly, individuals possessing boundaryless career orientations are more likely than other career actors to see beyond employment boundaries between wage-employment and entrepreneurial careers. Individuals with protean career views possess the cognitive self-management propensity and confidence necessary for making these types of career moves. Further, we argued that individual possessing high levels of both career orientations are even more likely to have high entrepreneurial intentions given that boundaryless orientations are inherently career actor agentic focused and protean orientations are ability centric. In other words, boundaryless views set the stage for confidently seeing entrepreneurship as a viable career change.

We theorized further that culture and experience associated with wage-employing organizations are important moderators of career orientation-entrepreneurial intentions relationships. In particular, we posited that cultures emphasizing self-direction and autonomy for employees would reinforce one’s boundaryless and protean orientations in driving entrepreneurial intentions. Furthermore, we argued that employees with longer tenures become more embedded in their organizations thereby reducing the influence that career views have on entrepreneurial intentions; a type of substitute effect. Therefore, newer employees with boundaryless and protean orientations may be most equipped to see entrepreneurship as a desirable and feasible career choice.

Theoretical implications

Our theory and model has important implications for entrepreneurship and management research. By viewing within the context of a career, we shed light on the problematic assumptions associated with entrepreneurial intentions as a first career choice (Burton et al. 2016). However, our career theoretical perspective more accurately describes aspiring entrepreneurs as employees thereby fundamentally changing cognitive questions related to why some people choose entrepreneurship while others do not; instead, the question becomes, why do some people chose to leave previously desired careers for entrepreneurial ones. We argue that this more realistic view of entrepreneurial intentions enriches what we know about aspiring entrepreneurs and sheds light their cognitive motivations for leaving behind wage-employment careers for entrepreneurship.

In terms of entrepreneurial intentions-based models, boundarlyess and protean career views aide in placing a greater amount of career actor agency in the hands of the career actor. That is to say, many intentions based models used in understanding entrepreneurial cognition have been criticized for assuming entrepreneurs merely process information and subsequently make decisions instead of taking career decision making into their own hands (Townsend et al. 2015). As noted earlier, our career perspective of entrepreneurial intentions places greater emphasis on an entrepreneur’s ability to see beyond employment boundaries and take action based on skills developed through self-managed thinking. Thus, we move cognitive individual differences research, specifically studies of entrepreneurial intentions to a more agency-based approach in which entrepreneurs take career decision making in their own hands instead of simply processing available information regarding opportunities for venture creation.

Finally, our paper has implications for practicing entrepreneurs as well. In our view, individuals thinking about moving from wage-employment to entrepreneurship must recognize their own cognitive limitations to crossing career boundaries and having confidence in making career related decisions. While boundaryless and protean views may be somewhat inherent in some individuals and not in others, there is no reason why these orientations cannot be learned and acquired. A recognition that boundaries do exist between employment domains may be the first step in seeing beyond those boundaries and developing the confidence to cross them. Further, for managers of individuals with boundaryless and protean views, it may be useful to provide more opportunities for enactment of entrepreneurial behaviors.

Future research directions

Future entrepreneurship research should adopt a careers perspective in analyzing other important outcomes beyond entrepreneurial intentions. For example, career concepts like boundaryless and protean views may be useful in explaining the types of businesses entrepreneurs tend to create (Morris et al. 2016). For example, given that many entrepreneurs move from wage-employment, why do some individuals pursue salary replacement, lifestyle-based, or high growth types of ventures given differences in boundaryless and protean views? It may be the case that only high protean, high boundaryless individuals pursue high growth ventures given the higher levels of risk.

Additionally, our model implies that the link between wage-employment and entrepreneurship is important for understanding entrepreneurs and the process through which they enter entrepreneurial careers. In this regard, future research should consider how other career concepts and theories predict future entrepreneurial activity among wage-employees. For example, it would be interesting to explore how the Kaleidoscope career model (KCM) might differentially explain decision-making at the wage-employment-entrepreneurship nexus (Mainiero and Sullivan 2005). This model relies on career parameters such as authenticity, balance, and challenge in explaining career decision making. How these concepts that characterize the impact and meaning that different forms of careers have on career actors and their decisions would be particularly interesting in the context of entrepreneurial intentions as entrepreneurs tend to differ in terms of the degree to which they have always felt “entrepreneurially” in their careers (Matthews et al. 2010).

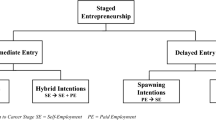

Other career concepts such as hybrid (Mainiero and Sullivan 2005), post corporate (Peiperl and Baruch 1997), and happenstance (Mitchell et al. 1999) careers could all similarly add richness to our understanding of entrepreneurial career intentions models. For example, research suggests that most entrepreneurs stage entry into entrepreneurial careers while remaining employed for wages (Folta et al. 2010) while a great deal of research also focuses on whether entrepreneurs are pulled or pushed into entrepreneurial careers due to employment environments (Amit and Muller 1995). These phenomena lack a career theoretical framing and inclusion of important career theoretical concepts to explain their existence and yet each are tied to the intersection of wage-employment and entrepreneurial careers.

Future research should also seek to establish additional contextual and explanatory mechanisms of our proposed model. For example, while self-efficacy is closely related to protean career orientations, it differs in that it focuses on self-belief rather than self-direction and management. However, this is a critical variable in entrepreneurship research (Zhao et al. 2005) and likely helps in explaining why some employees with certain career orientations are more inclined than others towards entrepreneurship. Additionally, while our model does include an environmental condition (organizational climate), it is important to consider other moderators of social context. For example, the entrepreneurial intentions of wage-employees are influenced by the entrepreneurial experiences and attitudes of peers (Nanda and Sørensen 2010). Therefore, it would be interesting to explore the moderating effects of workplace peer career attitudes on career orientations-entrepreneurial intentions relationships. Doing so will certainly enrich the utility of career-based models in entrepreneurship research.

Conclusion

The aim of this paper was to shed light on the fact that while many people do not chose entrepreneurship as a first career, entrepreneurial intentions models typically conceptualize the decision as such. We argue that career orientations, which explain initial career decisions, might shed greater light on why some individuals are inclined to leave wage-employment for entrepreneurship while others are not.

References

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50, 179–211.

Ajzen, I., Csasch, C., & Flood, M. G. (2009). From intentions to behavior: Implementation, intention, commitment, and conscientiousness. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 39(6), 1356–1372.

Amit, R., & Muller, E. (1995). “Push” and “pull” entrepreneurship. Journal of Small Business & Entrepreneurship, 12(4), 64–80.

Arthur, M. B., & Rousseau, D. M. (1996). The boundaryless career: A new employment principle for a new organizational era. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Baron, R. A. (1998). Cognitive mechanisms in entrepreneurship: Why and when entrepreneurs think differently than other people. Journal of Business Venturing, 13(4), 275–294.

Baruch, Y. (1998). The rise and fall of organizational commitment. Human Systems Management, 17(2), 135–143.

Baruch, Y. (2004). Transforming careers, from linear to multidirectional career paths: Organizational and individual perspectives. Career Development International, 9(1), 58–73.

Bird, A. (1994). Careers as repositories of knowledge: A new perspective on boundaryless careers. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 15, 325–344.

Blanchard, K. H., Carlos, J. P., & Randolph, W. A. (1995). The empowerment barometer and action plan. Escondido, CA: Blanchard Training and Development.

Briscoe, J. P., & Finkelstein, L. M. (2009). The "new career" and organizational commitment. Career Development International, 14(3), 242–260.

Briscoe, J. P., & Hall, D. T. (2006). The interplay of boundaryless and protean careers: Combinations and implications. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 69, 4–18.

Briscoe, J. P., Hall, D. T., & DeMuth, R. L. (2006). Protean and boundaryless careers: An empirical exploration. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 69, 30–47.

Briscoe, J. P., Henagan, S. C., Burton, J. P., & Murphy, W. M. (2012). Coping with an insecure employment environment: The differing roles of protean and boundaryless career orientations. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 80(2), 308–316.

Burton, M. D., Sørensen, J. B., & Dobrev, S. D. (2016). A careers perspective on entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 40(2), 237–247.

Busenitz, L. W., & Barney, J. B. (1997). Differences between entrepreneurs and managers in large organizations: Biases and heuristics in strategic decision-making. Journal of Business Venturing, 12, 9–30.

Carree, M. A., & Thurik, A. R. (2003). The impact of entrepreneurship on economic growth. In Handbook of entrepreneurship research (pp. 437–471). Springer US.

Carroll, G. R., & Mosakowski, E. M. (1987). The career dynamics of entrepreneurship. Administrative Science Quarterly, 32, 570–589.

Carsrud, A., & Brännback, M. (2011). Entrepreneurial motivations: What do we still need to know? Journal of Small Business Management, 49(1), 9–26.

Carter, N. M., Gartner, W. B., Shaver, K. G., & Gatewood, E. J. (2003). The career reasons of nascent entrepreneurs. Journal of Business Venturing, 18(1), 13–39.

Cohen, L., & Mallon, M. (1999). The transition from organisational employment to portfolio working: Perceptions of 'boundarylessness'. Work, Employment, & Society, 13, 329–352.

Cromie, S., & Hayes, J. (1991). Business ownership as a means of overcoming job dissatisfaction. Personnel Review, 20(1), 19–24.

Dawson, C., & Henley, A. (2012). "push" versus "pull" entrepreneurship: An ambiguous distinction? International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behaviour & Research, 18(6), 697–719.

De Vos, A., & Segers, J. (2013). Self-directed career attitude and retirement intentions. Career Development International, 18(2), 155–172.

Do Paço, A., Ferreira, J. M., Raposo, M., Rodrigues, R. G., & Dinis, A. (2015). Entrepreneurial intentions: Is education enough? International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 11(1), 57–75.

Douglas, E. J., & Shepherd, D. A. (2002). Entrepreneurship as a career choice: Attitudes, entrepreneurial intentions, and utility maximization. Entrepreneurship theory and practice, 26(3), 81–90.

Dyer, W. G. (1994). Toward a theory of entrepreneurial careers. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 19, 7–21.

Fayolle, A., & Linan, F. (2014). The future research on entrepreneurial intentions. Journal of Business Research, 67, 663–666.

Folta, T. B., Delmar, F., & Wennberg, K. (2010). Hybrid entrepreneurship. Management Science, 56(2), 253–269.

Frese, M., & Gielnik, M. M. (2014). The psychology of entrepreneurship. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 1(1), 413–438.

Fritsch, M., & Falck, O. (2007). New business formation by industry over space and time: A multi-dimensional analysis. Regional Studies, 41, 157–172.

George, N. M., Parida, V., Lahti, T., & Wincent, J. (2016). A systematic literature review of entrepreneurial opportunity recognition: Insights on influencing factors. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 12(2), 309–350.

Gerber, M., Wittekind, A., Grote, G., & Staffelbach, B. (2009). Exploring types of career orientation: A latent class analysis approach. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 75(3), 303–318.

Greve, A., & Salaff, J. W. (2003). Social networks and entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 28(1), 1–22.

Gubler, M., Arnold, J., & Coombs, C. (2013). Reassessing the protean career concept: Empirical findings, conceptual components, and measurement. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 35, 23–40.

Gunz, H. (1988). Organizational logistics of managerial careers. Organization Studies, 94, 529–554.

Hall, D. T. (1976). Career in organizations. Santa Monica, CA: Goodyear Publishing Company.

Hall, D. T. (1996). Protean careers of the 21st century. Academy of Management Executive, 10(4), 8–16.

Henderson, R., & Robertson, M. (2000). Who wants to be an entrepreneur. Career Development International, 5(6), 279–287.

Hess, N., Jepsen, D. M., & Dries, N. (2012). Career and employer change in the age of the ‘boundaryless’ career. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 81(2), 280–288.

Hytti, U. (2010). Contextualizing entrepreneurship in the boundaryless career. Gender in Management: An International Journal, 25, 64–81.

Inkson, K., Gunz, H., Ganesh, S., & Roper, J. (2012). Boundaryless careers: Bringing back boundaries. Organization Studies, 33(3), 323–340.

Jaros, S. J. (1997). An assessment of Meyer and Allen's (1991) three-component model of organizational commitment and turnover intentions. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 51(3), 319–337.

Kautonen, T., Van Gelderen, M., & Tornikoski, E. T. (2013). Predicting entrepreneurial behaviour: A test of the theory of planned behaviour. Applied Economics, 45(6), 697–707.

Kim, P. H., Aldrich, H. E., & Keister, L. A. (2006). Access (not) denied: The impact of financial, human, and cultural capital on entrepreneurial entry in the United States. Small Business Economics, 27(1), 5–22.

Kolvereid, L., & Isaksen, E. (2006). New business start-up and subsequent entry into self-employment. Journal of Business Venturing, 21(6), 866–885.

Krueger NF (2007) What lies beneath? The experiential essence of entrepreneurial thinking. Entrep Theory Pract, 31(1), 123–138

Krueger, N. F. (2009). Entrepreneurial intentions are dead: Long live entrepreneurial intentions. In A. L. Carsrud & M. Brannback (Eds.), Understanding the entrepreneurial mind, international studies in entrepreneurship (pp. 51–72). New York: Springer.

Krueger, N. F., Reilly, M. D., & Carsrud, A. L. (2000). Competing models of entrepreneurial intentions. Journal of Business Venturing, 15, 411–432.

Lee, T. W., & Maurer, S. D. (1999). The effects of family structure on organizational commitment, intention to leave and voluntary turnover. Journal of Managerial Issues, 11(4), 493–513.

Lee, T. W., & Mitchell, T. R. (1994). An alternative approach: The unfolding model of voluntary employee turnover. Academy of Management Review, 19(1), 51–89.

Lee, L., Wong, P., Foo, M. D., & Leung, A. (2011). Entrepreneurial intentions: The influence of organizational and individual factors. Journal of Business Venturing, 26, 124–136.

Liguori, E. W., Bendickson, J. S., & McDowell, W. C. (2018). Revisiting entrepreneurial intentions: a social cognitive career theory approach. Int Entrep Manag J, 14(1), 67–78.

Mainiero, L. A., & Sullivan, S. E. (2005). Kaleidoscope careers: An alternate explanation for the opt-out revolution. The Academy of Management Executive, 19(1), 106–123.

Mallon, M., & Cohen, L. (2001). Time for a change? Women's accounts of the move from organizational careers to entrepreneurship. British Journal of Management, 12(3), 217–230.

Marshall, D. R. (2016). From employment to entrepreneurship and back: A legitimate boundaryless view or a bias-embedded mindset? International Small Business Journal, 34(5), 683–700.

Matthews, R. B., Stowe, C. R. B., & Jenkins, G. K. (2010). Entrepreneurs - born or made? Proceedings of the Academy of Entrepreneurship, 17(1), 49–55.

Mitchell, J. O. (1981). The effects of intentions, tenure, personal and organizational variables on management turnover. Academy of Management Journal, 24(4), 742–751.

Mitchell, K. E., Levin, S., & Krumboltz, J. D. (1999). Planned happenstance: Constructing unexpected career opportunities. Journal of Counseling & Development, 77(2), 115–124.

Mitchell, T. R., Holtam, B. C., Lee, T. W., Sablynski, C. J., & Erez, M. (2001). Why people stay: Using job embeddedness to predict voluntary turnover. Academy of Management Journal, 44(6), 1102–1121.

Mitchell, R. K., Busenitz, L. W., Bird, B., Marie Gaglio, C., McMullen, J. S., Morse, E. A., & Smith, J. B. (2007). The central question in entrepreneurial cognition research 2007. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 31(1), 1–27.

Morris, M. H., Neumeyer, X., Jang, Y., & Kuratko, D. F. (2016). Distinguishing types of entrepreneurial ventures: An identity-based perspective. Journal of Small Business Management. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12272,

Nanda, R., & Sørensen, J. B. (2010). Workplace peers and entrepreneurship. Management Science, 56(7), 1116–1126.

Parker, S. C., & Belghitar, Y. (2006). What happens to nascent entrepreneurs? An econometric analysis of PSED. Small Business Economics, 27(1), 81–101.

Peiperl, M., & Baruch, Y. (1997). Back to square zero: The post-corporate career. Organizational Dynamics, 25(4), 7–22.

Politis, D. (2005). The process of entrepreneurial learning: A conceptual framework. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 29(4), 399–324.

Quan, X. (2012). Prior experience, social network, and levels of entrepreneurial intentions. Management Research Review, 35(10), 945–957.

Reitman, F., & Schneer, J. A. (2008). Enabling the new careers of the 21sst century. Organization Management Journal, 5, 17–28.

Rodrigues, R., Guest, D., & Budjanovcanin, A. (2013). From anchors to orientations: Toward a contemporary theory of career preferences. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 83, 142–152.

Schlaegel, C., & Koenig, M. (2014). Determinants of entrepreneurial intent: A meta-analytic test and integration of competing models. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 38(2), 291–332.

Schneider, B., & Reichers, A. E. (1983). On the etiology of climates. Personnel Psychology, 36(1), 19–39.

Segers, J., Inceoglu, I., Vloeberghs, D., Bartram, D., & Hendrickx, E. (2008). Protean and boundaryless careers: A study of potential motivators. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 73, 212–230.

Seibert, S. E., Silver, S. R., & Randolph, W. A. (2004). Taking empowerment to the next level: A multiple-level model of empowerment, performance, and satisfaction. Academy of Management Journal, 47(3), 332–349.

Sexton, D. L., & Bowman, N. (1986). The entrepreneur: A capable executive and more. Journal of Business Venturing, 1(1), 129–140.

Shapero, A., & Sokol, L. (1982). The social dimensions of entrepreneurship. In C. A. Kent, D. L. Sexton, & K. H. Vesper (Eds.), Encyclopedia of entrepreneurship (pp. 72–90). Englewoods Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Simon, M., Houghton, S. M., & Aquino, K. (1999). Cognitive biases, risk perception, and venture formation: How individuals decide to start companies. Journal of Business Venturing, 15, 113–134.

Singh, G., & DeNoble, A. (2003). Early retirees as the next generation of entrepreneurs. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 27(3), 207–226.

Skromme Granrose, C., & Baccili, P. A. (2006). Do psychological contracts include boundaryless or protean careers? Career Development International, 11(2), 163–182.

Sørensen, J. B. (2007). Bureaucracy and entrepreneurship: Workplace effects on entrepreneurial entry. Administrative Science Quarterly, 52(3), 387–412.

Sørensen, J. B., & Fassiotto, M. A. (2011). Organizations as fonts of entrepreneurship. Organization Science, 22(5), 1322–1331.

Supeli, A., & Creed, P. A. (2016). The longitudinal relationship between protean career orientation and job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and intention-to-quit. Journal of Career Development, 43(1), 66–80.

Tams, S., & Arthur, M. B. (2010). New directions for boundaryless careers: Agency and interdependence in a changing world. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 31(5), 629–646.

Tett, R. P., & Meyer, J. P. (1993). Job satisfaction, organizational commitment, turnover intention, and turnover: Path analyses based on meta-analytic findings. Personnel Psychology, 46(2), 259–293.

Townsend, D. M., Busenitz, W. B., & Arthurs, J. D. (2010). To start or not to start: Outcome and ability expectations in the decision to start a new venture. Journal of Business Venturing, 25, 192–202.

Townsend, D. M., Mitchell, J. R., Mitchell, R., & Busenitz, L. (2015). The eclipse and new dawn of individual differences in research (charting a path forward) (pp. 89–101). Routledge, New York, NY: The Routledge Companion to Entrepreneurship.

Tschopp, C., Grote, G., & Gerber, M. (2014). How career orientation shapes the job satisfaction–turnover intention link. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 35(2), 151–171.

Van Gelderen, M., Brand, M., Van Praag, M., Bodewes, W., Poutsma, E., & Van Gils, A. (2008). Explaining entrepreneurial intentions by means of the theory of planned behaviour. Career Development International, 13(6), 538–559.

Van Praag, C. M., & Versloot, P. H. (2007). What is the value of entrepreneurship? A review of recent research. Small Business Economics, 29(4), 351–382.

Zellweger, T., Sieger, P., & Halter, F. (2010). Should I stay or should I go? Career choice intentions of students with family business background. Journal of Business Venturing, 26(5), 521–536.

Zhang, X., & Bartol, K. M. (2010). Linking empowering leadership and employee creativity: The influence of psychological empowerment, intrinsic motivation, and creative process engagement. Academy of Management Journal, 53(1), 107–128.

Zhao, H., Seibert, S. E., & Hills, G. E. (2005). The mediating role of self-efficacy in the development of entrepreneurial intentions. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(6), 1265–1272.

Zhao, H., Seibert, S. E., & Lumpkin, G. T. (2010). The relationship of personality to entrepreneurial intentions and performance: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Management, 36(2), 381–404.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Marshall, D.R., Gigliotti, R. Bound for entrepreneurship? A career-theoretical perspective on entrepreneurial intentions. Int Entrep Manag J 16, 287–303 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-018-0523-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-018-0523-6