Abstract

Previous studies suggest that individual career satisfiers such as earning wealth and developing relationships with employees are important drivers of intentions to start an entrepreneurial career. However, less is known about their effects on broader, downstream career decisions such as intentions to remain in entrepreneurial careers. Based on data from 228 business owners, we find that employee relationship career satisfiers drive intentions to remain in entrepreneurship while status-based career satisfiers do not. Further, our study reveals that the cognitive relationships between career satisfiers and career continuance intentions are socially situated such that emotional support from family changes these relationships, especially when examined between owners of family and nonfamily businesses.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Of the nearly 50% of new businesses that close within 4 years of creation, 17% are considered by the owner to be operating successfully (Headd 2003), suggesting that business owners often decide to exit their ventures for a variety of reasons beyond financial stress and failure (DeTienne 2010). While entrepreneurial exit research has improved our understanding of possible triggers that lead owners to close their business (DeTienne and Cardon 2012), it has not addressed the deeper, cognitive motives underlying broader entrepreneurial career continuance issues. That is to say, we seem to know a great deal about why entrepreneurs decide to exit their ventures, but we know very little about why some choose to remain in entrepreneurial careers rather than choose other forms of employment. Exploring these deeper career desires can provide a more complete picture of entrepreneurial career decisions beyond simply the initial decision to start a business (Caliendo et al. 2014) and therefore may help to explain why some business owners close their doors despite financial success.

Entrepreneurship scholars suggest that understanding the dynamic relationship between career motives and career intentions is best understood from a socially situated cognition perspective (Bacq et al. 2017; Mitchell et al. 2011). This entails identifying both cognitive drivers of entrepreneurial career intentions and socio-environmental influences of these cognitive relationships (Smith and Semin 2004). Research shows that while starting an entrepreneurial career is often motivated by economic desires such as earning wealth and growing successful businesses (Carter et al. 2003; Cassar 2007), it can also be motivated by a variety of non-pecuniary career elements such as passion, favorable job characteristics, and pursuit of one’s own ideas (Benz 2009; Burke et al. 2002; Shane et al. 2003; Werner et al. 2014). Hence, the cognitive factors driving entrepreneurial continuance are likely based on satisfying career preferences for both achieving status, such as being recognized for business success, and more socioemotional preferences, rooted in the development of meaningful interpersonal relationships with employees (Eddleston and Powell 2008). Consequently, our aim is to link these two important career satisfiers related to status and employee relationships with intentions to remain in entrepreneurship.

In terms of important social factors that alter cognitive relationships between career satisfiers and intentions to remain an entrepreneur, entrepreneurship and careers literatures often point to the important influence of one’s family (Aldrich and Cliff 2003; Lent et al. 1994). In considering how individuals become embedded in their careers and committed to an occupation, research stresses how individuals take their family into account before making changes (Feldman and Ng 2007). Similarly, the family embeddedness perspective of entrepreneurship highlights how the intertwining of one’s family and business has a profound impact on entrepreneurial experiences (Aldrich and Cliff 2003; Powell and Eddleston 2013), suggesting that the family provides “the oxygen that feeds the fire of entrepreneurship” (Rogoff and Heck 2003: 559). Such research, therefore, suggests that a theory of entrepreneurial career continuance is incomplete without considering familial influence. Accordingly, we posit that relationships between the career satisfiers and intentions to remain an entrepreneur are contingent on entrepreneurs’ perceptions of emotional support from their families.

Further, since research drawing from the family embeddedness perspective suggests that the active involvement of family members in family firms creates a shared destiny among the family and fosters resiliency for an entrepreneur (Cruz et al. 2012), we also investigate socio-cognitive career relationship differences between owners of family and nonfamily firms. Specifically, because of the increased role of family members in family businesses (Powell and Eddleston 2017), we contend that the moderating effects of emotional support from family on the cognitive relationships between career preferences and intentions to remain an entrepreneur are intensified for entrepreneurs who own family businesses.

Analysis of 228 entrepreneurs provides evidence that career satisfiers related to the development of employee relationships are important drivers of increased intentions to remain an entrepreneur, while status-based drivers are not. Further, our findings provide support for social-cognitive approaches to entrepreneurial career decisions in that emotional support from family interacts with individual career satisfiers to predict intentions to stay in entrepreneurship. However, the results highlight the complexity with which family support influences entrepreneurs’ career decisions by revealing that family support can strengthen one’s resolve to remain in entrepreneurship when it is properly aligned with the career goals of the entrepreneur, but it can also be a hindrance to continued entrepreneurship when misaligned. Additionally, we find that these relationships change depending on whether the entrepreneur owns a family or nonfamily business. For owners of family businesses, high perceived emotional support from family has the greatest impact on intentions to remain in entrepreneurship for those who place little importance on employee relationships. Thus, contrary to our hypotheses, it appears that family relationships may substitute employee relationship cognitive drivers. For owners of nonfamily businesses, high perceived emotional support from family amplifies the positive effect of employee relationships on intentions to remain in entrepreneurship.

In examining intentions to remain in entrepreneurial careers, we provide a more nuanced view of entrepreneurial career theory (Burton et al. 2016; Dyer 1994) by moving beyond a singular focus on drivers of simply entering entrepreneurship to factors explaining commitment to the entrepreneurship career path. Further, this study pushes researchers to consider the underlying cognitive and socio-emotional mechanisms of entrepreneurial decision making beyond those tied to specific ventures (Shepherd et al. 2015). By explaining the interactive effects of cognitive career drivers and emotional support from family in both family and nonfamily businesses, we answer calls for integrative cognitive and socio-emotional-based models in entrepreneurship studies (Dew et al. 2015; Mitchell et al. 2011). Practically, explaining what compels entrepreneurs to continue in their current career paths aids in understanding why some owners exit ventures despite financial success. In doing so, this study makes ancillary contributions to theory at the entrepreneurship-family interface (Jennings and McDougald 2007) and social-contextual effects in entrepreneurial processes (Zhara 2007).

2 Theory and hypotheses

2.1 A socially situated cognitive perspective on remaining in an entrepreneurial career

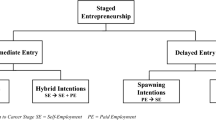

Entrepreneurial career theory is concerned with explaining “the careers of those who found organizations” (Dyer 1994: 8). As a unique and distinct career path, an entrepreneurial career may span the entirety of an individual’s career life or merely explain a phase in one’s overall career journey (Hytti 2010). Entrepreneurial careers encompass a host of career progression dilemmas influenced by stress, hiring employees, balancing work and family, managing firm growth, developing an organizational hierarchy, maintaining control of the venture, succession planning, and business survival (Dyer 1994; Katz 1994). Based on these career challenges, career-related decisions often concern issues of entrepreneurial career continuance (DeTienne 2010). However, few studies have adequately addressed intentions to remain in an entrepreneurial career (Feldman and Bolino 2000). Intentions to remain an entrepreneur reflect a business owner’s emotional linkage to an entrepreneurial career based on value fulfillment and needs satisfaction (Felfe et al. 2008). Hence, we posit that an entrepreneur’s intention to continue in an entrepreneurial career signifies a desire to satisfy career needs through continued business ownership rather than other forms of employment.

The socially situated cognitive perspective of entrepreneurship stems from Bandura’s (1989) theory of social cognition which proposes that human agency to act or intend to act is part of a causal structure in which cognitive and environmental factors interact. Thus, applying a socio-cognitive lens to the study of entrepreneurial careers calls for the explanation and examination of both cognitive and social-environmental factors associated with career-related intentions such as embarking on an entrepreneurial career (Bacq et al. 2017) and future career plans (Marshall 2016). Socio-cognitive career perspectives in particular suggest that contextual factors such as family influences, “fuel personal interests and choices and comprise the real and perceived opportunity structure within which career plans are devised and implemented” (Lent et al. 1994: 107). Hence, in our socially situated cognition framework of entrepreneurial career continuance, career satisfiers represent the cognitive factors that drive intentions to remain an entrepreneur, while emotional support from family and the status of the entrepreneur as a family versus nonfamily business owner represent the socio-environmental factors that interact with cognitive career satisfiers to explain intentions to remain.

2.2 Cognitive factors—status-based and employee relationship career satisfiers

The careers and entrepreneurship literatures suggest that career choices are influenced by perceptions of the degree to which elements of a career meet the needs of the career actor (Carter et al. 2003; Eddleston and Powell 2008; Mitchell et al. 2001). Accordingly, intentions to remain an entrepreneur are likely influenced by one’s preference for, and satisfaction with, certain types of career work (Feldman and Bolino 2000). One method of determining career preferences is accomplished by examining individual career satisfiers. Career satisfiers represent what individuals are looking for in their careers (Eddleston et al. 2006). While prior studies on sources of entrepreneurial career satisfaction have tended to concentrate on economic and financial measures (i.e., status-based career satisfiers), research has begun to acknowledge the importance many entrepreneurs place on non-pecuniary sources of career satisfaction (Shane et al. 2003), especially those associated with interpersonal relationships (Walker and Brown 2004). Sources of career satisfaction are important to study as they may help explain why some entrepreneurs decide to leave an entrepreneurial career for an alternative career path and shed light on what factors keep them engaged in entrepreneurship. Accordingly, we consider two primary sources of career satisfaction in which entrepreneurs may place career importance: status-based and employee relationship satisfiers.

The value an entrepreneur places on achieving prestige, social status, and making money represents status-based career satisfiers (Eddleston and Powell 2008). While many entrepreneurs are motivated to pursue entrepreneurial careers for purely economic reasons (Carsrud and Brännback 2011), the effects of status-based satisfiers on downstream, important career decisions such as intentions to remain an entrepreneur are relatively unknown. An individual who believes that entrepreneurship is the most effective means through which needs for achieving status can be satisfied is likely to possess a strong desire to continue with an entrepreneurial career. For entrepreneurs driven by the pursuit of wealth (Carter et al. 2003) and a sense of leadership and/or status (Eddleston and Powell 2008), we posit that they will intend to continue with entrepreneurship because they perceive this career as both a desirable and feasible medium to satisfy status-based motives. While status can also be gained through wage-employment careers, hierarchical structures make it difficult and time consuming for individuals to achieve high ranking leadership positions and to consistently gain salary increases. As such, a traditional career path is often described as a tournament whereby only the top performers gain significant status and earnings (Rosenbaum 1979). However, freedom and independence are valued elements of entrepreneurial careers (Benz and Frey 2008) that are particularly conducive to gaining prestige and financial success through the founding, leading, and growing of a world class business (Eddleston and Powell 2008). As a result, entrepreneurs who highly value status-based career satisfiers are likely to possess strong intentions to remain an entrepreneur.

Hypothesis 1: Status-based career satisfiers are positively related to intentions to remain in an entrepreneurial career.

The importance placed on fostering positive relationships with employees and developing a work environment that is friendly and supportive characterizes employee relationship career satisfiers (Eddleston and Powell 2008). This career satisfier is grounded in more socioemotional and non-pecuniary desires than in economic-based motives (Eddleston et al. 2006). Accordingly, the development of meaningful relationships with employees and members of their entrepreneurial teams creates value and satisfaction for entrepreneurs thereby enhancing emotional attachment to their respective careers (Berrone et al. 2010).

For individuals placing importance on satisfying the need to foster positive interpersonal relationships with employees, entrepreneurship may be the feasible and desirable means for creating such workplace environments. Business owners possess a great degree of control over venture operations such as human resource functions (selection, retention) and therefore can hire and retain employees who best aid in fulfilling needs for meaningful, positive employee relationships. Indeed, business owners play a significant role in creating and sustaining their organization’s culture (Schein 1995) which allows them to create and nurture a workplace emphasizing their vision for positive employee relationships. In turn, those who highly value employee relationships likely possess strong intentions to remain as entrepreneurs because they feel responsible for the overall well-being and job security of their employees. Research on occupational commitment highlights how strong interpersonal relationships keep individuals from changing their current employment situations (Feldman and Ng 2007) because the loss of such relationships would be seen as a significant sacrifice (Mitchell et al. 2001). Applying this logic to entrepreneurs, leaving entrepreneurial careers would not only mean the potential loss of employee relationships but also the sacrifice of their employees’ jobs, a sacrifice they are likely unwilling to make if they possess high employee relationship career satisfiers. Accordingly, entrepreneurs possessing employee relationship career satisfiers will exhibit greater intentions to remain an entrepreneur.

Hypothesis 2: Employee relationship career satisfiers are positively related to intentions to remain in an entrepreneurial career.

2.3 Social influence—perceived emotional support from family

Research on occupational embeddedness (Feldman and Ng 2007) and the family embeddedness perspective of entrepreneurship (Aldrich and Cliff 2003) suggests that frameworks aiming to understand career decisions are incomplete without considering the role of one’s family. Studies of career decision making often highlight the important role family plays in shaping individual career decisions (e.g., Chope 2005; Feldman and Ng 2007) such as occupational choice (Maertz and Griffeth 2004) and career change (Feldman and Ng 2007). Additionally, entrepreneurship research acknowledges how family support can motivate individuals to launch a business (Aldrich and Cliff 2003; Rogoff and Heck 2003) and can enrich entrepreneurial experiences (Jennings and McDougald 2007). Given our focus on understanding entrepreneurs’ career continuance, it is necessary to consider the way in which perceptions of family support alter relationships between career satisfiers and intentions to remain an entrepreneur.

According to careers research, one of the primary types of support provided by one’s family is emotional (Adams et al. 1996; King et al. 1995). Emotional support reflects the encouragement, understanding, and positive regard a family bestows an entrepreneur regarding their business (Powell and Eddleston 2013). For example, family members who provide emotional support can embolden one’s career choice to be an entrepreneur or empathize with frustrations arising from entrepreneurial participation (Powell and Eddleston 2013). Further, research on the work-family interface suggests that when individuals feel positive in their family domain and supported by family members, persistence in their careers is enhanced (Greenhaus and Powell 2006). For entrepreneurs, emotional support from family is an important source of work-family enrichment that helps entrepreneurs navigate the challenges of business ownership and gain resilience (Powell and Eddleston 2013). That is to say, because emotional support often includes encouragement and reassurance, perceptions of emotional support from family should act as a form of positive reinforcement to an individual’s career satisfiers. Consequently, when individuals perceive a great deal of emotional support from family regarding their businesses, their own career motives (satisfiers) are reinforced and intentions for continued entrepreneurship increase. For example, entrepreneurs driven to continue in entrepreneurship based on employee relationships should feel even more inclined to do so when they perceive their family supports entrepreneurial activities. Therefore, family emotional support is expected to strengthen the positive effects of the career satisfiers on intentions to remain an entrepreneur.

In contrast, a lack of perceived emotional support from family is likely to have the opposite effect thereby weakening the influence of career satisfiers on intentions to remain an entrepreneur. Inadequate support systems may be perceived as impediments to translating career interests into goals and actions (Lent et al. 2000). For instance, it has been argued that college students perceiving a lack of parental support for their chosen majors often eventually view their majors as barriers to satisfying career goals and subsequently change majors to those more congruent with parental expectations (Lent et al. 2000). As such, a perceived lack of family support for one’s business may signal to the entrepreneur that he/she will not be able to satisfy career needs through an entrepreneurial career path thereby weakening the cognitive relationships between career satisfiers and intentions to remain.

Hypothesis 3: Perceived emotional support from family moderates the relationship between status-based career satisfiers and intentions to remain an entrepreneur such that the relationship will be stronger at higher levels of perceived emotional support from family.

Hypothesis 4: Perceived emotional support from family moderates the relationship between employee-relationship career satisfiers and intentions to remain an entrepreneur such that the relationship will be stronger at higher levels of perceived emotional support from family.

2.4 Environmental contextual factors—status as a family or nonfamily business owner

An embedded view of socially situated cognition (Dew et al. 2015) advocates that variations in inner socio-cognitive interactions (e.g., interaction of career satisfiers and emotional support from family on intentions to remain) are affected by closely related outer environmental contexts (Mitchell et al. 2011, 2014). Given our contention regarding the important role of family influence in the relationships between career preferences and career intentions, family businesses represent an important context in which these relationships are likely changed. This line of reasoning closely aligns with research demonstrating that family businesses represent an extreme form of family embeddedness whereby the family’s influence on the business has a particularly profound effect on the entrepreneur and related career decisions (Cruz et al. 2012; Rogoff and Heck 2003). In family businesses, the boundaries between the family and business are more porous and there exists greater potential for spillover between the two domains in comparison to nonfamily businesses (Sundaramurthy and Kreiner 2008). This spillover can either enrich the experiences of entrepreneurs or hamper their ability to effectively make leadership decisions (Jennings and McDougald 2007). Therefore, we investigate the moderating effects of perceived emotional support from family on the career satisfiers-intentions to remain an entrepreneur relationship for family and nonfamily businesses to uncover how entrepreneurs who work with family members are affected differently by family emotional support than those who own a business which does not involve family ownership or employment.

Studying the intentions of family and nonfamily business owners to remain in entrepreneurship is important because each type of entrepreneur faces a different set of career pressures and challenges which may affect decisions to remain in entrepreneurship. For example, owners of family businesses are often concerned with generational ownership (Ibrahim et al. 2001) and protecting future employment for family members which likely affect commitment to entrepreneurial careers. Conversely, nonfamily business owners are less concerned with employing family members and succession and tend to focus on their own independence and autonomy (Barnett et al. 2009). These entrepreneurs are also less concerned with creating synergy between family and business than owners of family businesses (Pearson et al. 2008) which should make emotional support from family less important to their career decisions. As such, emotional support from family in enhancing cognitive relationships between career satisfiers and intentions to remain are likely to vary between entrepreneurs of family versus nonfamily businesses.

In terms of the effects of emotional support on the relationships between an entrepreneur’s career satisfiers and intentions to remain an entrepreneur, our basic premise is that because the family system is so uniquely intertwined with the business system in family firms (Sharma 2004), owners of these types of ventures are likely to experience more intensified and pronounced effects of perceptions of emotional family support on their career satisfier-career intentions relationships than nonfamily business entrepreneurs. Because in family businesses, the dual systems of family and business interact and overlap to a far greater degree than in nonfamily businesses (Beehr et al. 1997; Moshavi and Koch 2005), the family business owner may be better able to extract and apply benefits from family emotional support than nonfamily business owners. The inextricable link between work and family for family business owners may also make the degree of family emotional support highly salient in making career decisions (Barnett et al. 2009). Accordingly, high perceptions of emotional support from family are expected to more strongly augment the career satisfiers-intentions to remain relationships for entrepreneurs operating family businesses than for those running traditional, nonfamily firms.

In contrast, for those family business owners who lack emotional support from family, the expected positive effects of status-based and employee relationship career satisfiers on intentions to remain an entrepreneur should be reduced. For these family business owners, the lack of family support is expected to mitigate the cognitive benefits of career satisfiers in motivating intentions to remain. In other words, intentions to remain an entrepreneur are much more dependent on emotional support from family for the family business entrepreneur than for the nonfamily business entrepreneur. Indeed, owners of family businesses perceiving a lack of support often struggle to achieve their individual career goals (Van Auken and Werbel 2006). Accordingly, family firm entrepreneurs perceiving high emotional support from family should report strong intentions to remain in entrepreneurial careers when they place a great deal of importance on status-based and employee relationship career satisfiers. These perceptions of emotional support from their families should help entrepreneurs to feel that their career interests are obtainable through continued family business ownership. Hence, we hypothesize the following:

Hypothesis 5: Perceived emotional support from family more positively moderates the relationship between status-based career satisfiers and intentions to remain an entrepreneur for owners of family firms than nonfamily firms.

Hypothesis 6: Perceived emotional support from family more positively moderates the relationship between employee relationship career satisfiers and intentions to remain an entrepreneur for owners of family firms than nonfamily firms.

3 Methodology

3.1 Sample

Given that our study aims to analyze intentions to remain in entrepreneurial careers, it was critical to gather responses from individuals who had already entered the entrepreneurship career field and were actively participating in business ownership. Reponses from individuals who have already exited entrepreneurship or who are only considering entering entrepreneurship would likely bias results a great deal as new entrants would have strong inclinations toward continuance and former business owners may have already undergone career transitions. Hence, we wanted to capture variations in intentions for continued entrepreneurship for entrepreneurs between the nascent and retirement career stages. Therefore, we utilized alumni mailing lists from two entrepreneurship centers located in Northeast USA. We sent survey questionnaires to 1290 participants and received 247 useable responses from individuals indicating current participation in entrepreneurial careers.

Responses came from owners of for-profit, privately held firms averaging 10.17 full-time employees. Other attributes of the sample include the following: race/ethnicity (83% Caucasian, 10% African-American, 4% Asian-American, 2% Hispanic, 1% other); average age of the owner (46.10 years); marital status (61% married, 23% single, 12% divorced, 2% separated, 1% widowed); average number of children (0.66); and the average number of years in business (11.69). The sample was slightly skewed toward females (n = 148) over males (n = 99) because one of the sources of data focused on women in business. Sampled businesses came from a range of industries (services = 71; retail = 34; health = 28). A series of ANOVAs were conducted to gauge the effects of industry on the studied constructs, and no significant differences were found (p > .05).

With the data collection occurring at one point in time and from one respondent, we tested for the potential effects of common methods bias through principal component analysis with all constructs. If only one factor emerged with greater than 50% of the explained variance, this might suggest the potential for common method bias. We conducted the analysis with no rotation of the items employed in the study, resulting in the emergence of seven factors with Eigenvalues greater than 1. The first factor accounted for 20% of the total explained variance of 60% indicating that common methods should not influence the results (Harman 1967). To further gauge the effects of common method bias in our sample, we compared a measurement model with the relevant latent constructs to a measurement model with the same constructs and an additional single common latent factor. If the measurement model with the single common construct was to explain more than 25% relative to the measurement model without the common latent factor, then the effects associated with common method bias would be prevalent in our sample (Carlson and Kacmar 2000). The variance difference between the hypothesized measurement model and the common method factor measurement model was only 1.34%, which is well below the 25% threshold, indicating that the effects of common method bias are limited.

3.2 Measures

Dependent variable

We measured intentions to remain an entrepreneur using a four-item scale created by Feldman and Bolino (2000). It is important to note that in the career literature, intentions to remain in one’s current job have repeatedly been demonstrated to reliably predict actual behavior (Griffeth et al. 2000). This seven-point Likert-type scale is anchored from strongly disagree to strongly agree. The coefficient alpha for the scale is 0.79. All items that comprise this scale as well as the other scales used in our study are listed in the Appendix.

Independent variables

To measure both status-based and employee relationship career satisfiers, we utilized scales developed by Eddleston and Powell (2008). Each of these five-point Likert-type scales is anchored from unimportant to very important. The importance of status-based career satisfiers demonstrates good internal consistency (α = .75), and a sample item includes indicating the importance of “having high prestige and social status” in one’s career. Reliability of the importance of employee relationships career satisfiers is acceptable (α = .80), and a sample item for items includes importance of “developing mutually beneficial relationships with employees” in one’s career.

Moderating variables

Powell and Eddleston (2013) provide a process for adapting an emotional support scale from King et al.’s (1995) emotional sustenance items from the family support inventory. Following this guidance, we adapted four items from King et al.’s (1995) family support inventory to create a more parsimonious instrument applicable to business owners. An example item from the scale includes “when I talk with them about my business, family members don’t really listen” (reverse-coded). The Likert-type measure is anchored from strongly disagree to strongly agree on a seven-point scale and is reliable (α = .83). Ventures were classified as family/nonfamily (family firm status) in accordance with leading family business research (e.g., Zahra et al. 2008). We asked respondents to self-identify as owning a family-owned firm and indicate the degree to which family members, not including the entrepreneur, worked in the business (i.e., number of family employees). This resulted in 108 family business owners and 110 nonfamily firm owners, with 27 ventures failing to provide adequate information. Dummy variables for family firms were coded as 1 and nonfamily firms as − 1 (Miller et al. 2014).

Control variables

A number of control variables deemed important to understanding the hypothesized relationships were included in the analysis. Gender, number of children, age of the business owner, education, and career salience (importance one places on his/her career in general—Barnett et al. 2009; three item scale; α = .65) have all been shown to influence career choice decisions (e.g., Lobel and St. Clair 1992); hence, we partial out these effects. We also controlled for the number of full-time employees and current venture growth (two Likert-type items, asking respondents to compare their ventures to their competitors; α = .77), as these variables influence decisions related to progress in one’s venture and subsequent continued participation in entrepreneurship (e.g., Wiklund et al. 2009).

3.3 Analyses and results

The descriptive statistics and correlation matrix are provided in Table 1. The results indicate that the correlation among different constructs is within an acceptable range (r = − .20 to r = .43) suggesting few signs of collinearity, with variance inflation factor scores under 3.8. We employed confirmatory factory analysis with maximum likelihood estimation to test for measurement invariance. Except for two items, convergent validity was attained with all standardized loadings for the different items being above .40 and statistically significant (p < .05) in the unconstrained factor model. Items dropped from further analysis came from the status-based career satisfier’s scale (earning a lot of money, being highly regarded in my field). For the unconstrained factor model, the different constructs are allowed to covary, while in the constrained factor model, all constructs in the Φ matrix are set to one. We then tested for differences between the unconstrained factor model (χ2 = 362.37; df = 237; p < .05; CFI = .95; RMSEA = .052; SRMR = .061) and the constrained factor model (χ2 = 1406.31; df = 230; p < .05; CFI = .57; RMSEA = .15; SRMR = .13). The chi-square difference test (Δχ2 = 1043.94; df = 7; p < .05) indicates that the unconstrained factor model significantly fits the data better than the constrained factor model. Average variance extracted (AVE) of the studied constructs ranged from a low of .40 (status-based satisfiers) to a high of .56 (perceived emotional support from family). Discriminant validity was supported, as the squared correlation between pairs of constructs did not exceed the AVEs. Also, composite reliabilities ran from .76 for status-based satisfiers to .83 for perceived emotional support.

For hypothesis testing, we followed the guidance provided by Le et al. (2013) and employed OLS regression, as we are examining interaction terms using cross-sectional data. All measurement scores were standardized for each construct to reduce the effects of collinearity in interaction terms.

As seen in Table 2 Model 5, intent to remain an entrepreneur was significantly impacted by career salience (b = .29; p < .01) and current venture growth (b = .16; p < .01). All other control variables (gender, number of children, age, education, number of employees) exhibited non-significant relationships with intentions to remain in entrepreneurship. Overall, the full model has an adjusted R2 of .198.

As seen in Model 5, Hypothesis 1, which predicted that status-based career satisfiers would positively predict intentions to remain an entrepreneur, was not supported (b = − .06; p > .05). However, support is garnered for Hypothesis 2 with a positive relationship between employee relationship satisfiers and intentions to remain (b = .31; p < .01). Taken together, these results suggest that the importance placed on employee relationships is more likely to keep entrepreneurs committed to an entrepreneurial career than status-based career satisfiers.

In Hypotheses 3 and 4, we argued positive moderating effects of perceived emotional support from family on both career satisfier-intentions to remain relationships. While the status-based satisfier × perceived emotional support interaction term is significant (b = − .17; p < .05), the graphical representation of the relationship suggests that greater emotional support actually reduced intentions to remain for high status-based entrepreneurs. The interaction term for employee relationship satisfiers and perceived emotional support from family is also significant (b = .20; p < .05) and the graphical representation of this relationship supports Hypothesis 4. (Fig. 1).

The remainder of our hypotheses focus on the threeway interactive effects of career satisfiers, perceived emotional support from family, and the entrepreneurs’ status as a family or nonfamily business owner. We followed the guidance set forth by Dawson and Richter (2006) for testing three-way interactions (Hypotheses 5 and 6). Results provide initial support for both hypotheses, as the three-way interaction terms are significant: status × emotional support × family firm status (b = .31; p < .01) and employee relationship × emotional support × family firm status (b = − .46; p < .01). Given the dichotomous nature of the second moderating variable of family firm status, we followed the approach suggested by Bing and Burroughs (2001) for graphing these interactions. As illustrated in Fig. 2, there is a positive relationship between status-based career satisfiers and high perceived emotional support from family for entrepreneurs of family-owned businesses. Conversely, we see a negative relationship for nonfamily business owners, providing support for Hypothesis 5. Thus, increased perceptions of emotional support from family are associated with higher intentions to remain an entrepreneur for family business owners driven by status, but the opposite is true for nonfamily business owners.

Surprisingly, the graphical depictions in Fig. 3 Hypothesis 6 results indicate that increases in perceptions of emotional support from family appear to most strongly enhance intentions to remain an entrepreneur for nonfamily business entrepreneurs who are driven by employee relationship career satisfiers, while the relationship appears unaffected for family firm owners perceiving a great deal of emotional support from family. This is contrary to our prediction and leads to a rejection of this hypothesis. We address this interesting finding in greater depth in Sect. 4.

As a robustness check, we conducted additional analyses to confirm differences between family and nonfamily business owners. Following Cruz et al. (2010), we conducted Chow tests between family and nonfamily business entrepreneurs for the regression equation with intentions to remain an entrepreneur as the dependent variable. The results indicate that family and nonfamily entrepreneurs’ responses are significantly different (F-value = 4.40; p < .05; d.f. = 28, 152). Similarly, the graphical interpretations were in a comparable directional pattern as presented in Figs. 2 and 3. The slope difference testing at plus/minus one standard deviation (Dawson and Richter 2006) additionally confirms significant differences between the interaction slopes for family and nonfamily business relationships on the studied constructs, providing additional support for our earlier findings.

4 Discussion of results, future research implications, and study limitations

Our understanding of the cognitive, decision making processes of individuals in entrepreneurial careers have mainly been confined to intentions to enter entrepreneurship and decisions to exit a specific venture (Shepherd et al. 2015). However, entrepreneurship scholars have recently called for increased research attention to the decisions entrepreneurs make about their careers beyond those associated with simply whether or not to enter entrepreneurship (Burton et al. 2016). Therefore, our aim in this study was to contribute to this expanded view of entrepreneurial careers by focusing on continued commitment to entrepreneurship as a career. Specifically, we focused on explaining some of the underlying socio-cognitive mechanisms of intentions to remain in entrepreneurial careers and believe that the results of this study have important implications for future research on entrepreneurial career decision making and socially situated cognition perspectives in entrepreneurship.

Based on the socially situated cognition perspective of entrepreneurship, we examined how two important career satisfiers impact an individual’s intentions to continue as an entrepreneur. Interestingly, we found little evidence to support our assertion that status-based career satisfiers were important drivers of remaining an entrepreneur. This is surprising given the historically important role that financial incentives and social prominence play in driving initial entrepreneurial entrance decisions (Carsrud and Brännback 2011). We did find support for increased intentions to remain an entrepreneur for those placing high import on establishing positive relationships with employees. Our results build on research highlighting the motivational power of non-pecuniary elements associated with entrepreneurial participation (Burke et al. 2002; Georgellis et al. 2007) in suggesting that entrepreneurs may be more motivated to continue down an entrepreneurial career path based on interpersonal factors than financial rewards. Future research should therefore address how other socially influenced career motivators such as the desire for work-family balance or to affect social change impact intentions to remain an entrepreneur versus the initial decision to enter entrepreneurship.

Additionally, our model and findings extend socially situated cognitive approaches (Mitchell et al. 2011) in entrepreneurship by highlighting the important role of emotion (Cardon et al. 2012) and family embeddedness (Aldrich and Cliff 2003; Powell and Eddleston 2013) in entrepreneurial career decision making. Our results point to a potentially intriguing phenomenon in terms of the role of family and their emotional support in entrepreneurial decision making processes. That is, high emotional support appears to positively impact career decisions motivated by socioemotional reasons but has a negative effect when motivated by status-based satisfiers. Thus, in conjunction with other socio-cognitive studies (Lent et al. 1994), we find that in some cases, emotional support can both reinforce and impede an entrepreneur’s own career desires.

From a practical standpoint, these results are important for business owners and their families in recognizing that emotional support from others may be a hindrance in terms of continuing an entrepreneurial career if it does not align with the career goals of the owner. For example, a family providing a great deal of emotional support may do more harm than good for an owner driven by achieving status but who fails to see continued entrepreneurship as a means to achieve this goal. Conservation of resources theory (Hobfoll 1989) might support this finding such that an entrepreneur may become disenchanted with future business ownership if the type of resources received (emotional support) does not align with his/her career desires. Again, this may suggest that family support can sometimes be viewed as constrictive instead of supportive and facilitative. Additionally, prior research demonstrates that those who highly value status in their careers often find it difficult to feel a sense of achievement or accomplishment (Eddleston and Powell 2008), and family support may make this feeling more salient, further decreasing intentions to continue down an entrepreneurial career path. In contrast, for those valuing interpersonal relationships, family emotional support might align nicely with career goals and help the entrepreneur feel a sense of career accomplishment, driving intentions to continue in the career even higher.

We further extend the socially situated cognitive perspective in entrepreneurship and entrepreneurial career theory by exploring how socio-cognitive career relationships vary in unique business contexts, family versus nonfamily businesses. Unique contextualizations of important entrepreneurship questions aid in filling theoretical gaps in our knowledge about how diverse types of entrepreneurs might approach important entrepreneurial career decisions (Zahra 2007). We found that for family firm entrepreneurs, a great deal of emotional support from family has a positive effect on the relationship between status-based career satisfiers and intentions to remain an entrepreneur but may not have the same effect for employee relationship satisfiers. These results speak to a possible social substitution effect in that a great deal of emotional support from family may satisfy an owner’s interpersonal career needs and simply maintain a steady level of interest in pursuing positive relationships with employees through continued entrepreneurship. Figure 3 suggests that perhaps high emotional support from family compensates for a lack of interest in employee relationships which drive greater intentions to remain an entrepreneur, but for those high in employee relationships, emotional support does very little in affecting intentions to remain. However, we do not see a similar effect for nonfamily firm entrepreneurs. Instead, high emotional support from family intensifies the positive effect of importance placed on employee relationship career satisfiers on intentions to remain an entrepreneur.

These findings have implications for family business research. We found that when family support is high, family business entrepreneurs driven by status-based satisfiers may actually intend on remaining in entrepreneurship more than those driven by employee relationships. This may be somewhat contrary to prevailing assumptions regarding firms and their family dynamics. Specifically, research suggests that family business entrepreneurs are generally more driven by non-status-based motives (Gomez-Mejia et al. 2011) and that family members play a central role in influencing these motives (Chrisman et al. 2012). However, this research typically has not considered how the entrepreneur feels about his/her career. Therefore, our findings speak to the intriguing possibility that perhaps entrepreneurs in family firms feel responsible for providing financially for the family, and family support for financially driven motives increases intentions for continued entrepreneurship. Future family business research would do well to consider the effects individual entrepreneur career motivations have on venture outcomes and the impact of alignment (misalignment) with the goals of the owning family.

Despite these interesting findings, this study has a number of limitations. First, while it was critical, our sample includes entrepreneurs currently engaged in business ownership to assess intentions to remain, and there is potential for selection bias affecting the study’s results. Because we drew responses from entrepreneurs who at one time had been associated with entrepreneurship centers, it is possible that these individuals already have higher intentions to remain given that they may have sought support in the past for their entrepreneurial pursuits. However, these individuals may also possess greater understanding of varying problems and challenges associated with venturing and the future viability of their businesses, thereby allowing them to provide more informed intentions to remain responses and more robust insights into socio-cognitive mechanisms affecting these intentions. While we believe that the number of entrepreneurs in our sample actively involved in entrepreneurship centers is small, and therefore any selection bias in our results marginal, future research would certainly benefit from considering entrepreneurial continuance of individuals from various sample settings and contexts, such as entrepreneurs with limited access to entrepreneurial educational resources. Second, this data sample was collected at a single point in time making it difficult to infer causality. For example, we assume that emotional support from family affects the cognitive relationships between career satisfiers and intentions. However, it is possible that an entrepreneur’s career motives actually affect or elicit an emotional response from the family members. This is a particularly intriguing avenue for future entrepreneurship and careers research. Future longitudinal research designs with multiple respondents from within an entrepreneur’s network will help attenuate the effects of these limitations. We point out that the statistically significant interaction terms alleviate some concerns regarding any common methods bias (Siemsen et al. 2010). Third, the family firm status as a moderator could potentially confound the hypothesized effects. For example, family firm owners may feel obligated to remain in entrepreneurship based on a sense of duty to family (Sharma and Irving 2005). Our results indicate differences in responses between family and nonfamily owners, and we encourage future research to further study the careers of family business entrepreneurs and to explore how it differs from an entrepreneur who does not own a family business. Fourth, while we controlled for several important variables, there are a number of factors, in addition to career satisfiers, that likely affect intentions to remain, some of which have been studied elsewhere (Cassar 2007; Feldman and Bolino 2000). Future studies focused on explaining why some entrepreneurs remain in their careers would benefit from inclusion of psychological, social, and contextual variables such as autonomy and self-efficacy to identify which variables are most impactful.

5 Conclusion

Moving beyond intentions to enter entrepreneurship, this study examines intentions to remain in entrepreneurial careers. Based on a socially situated cognition theoretical lens, individual career satisfiers such as desires to develop meaningful relationships with employees are important for continued entrepreneurship. In alignment with the family embeddedness perspective of entrepreneurship, emotional support from family is an important social condition of cognitive satisfier-to-intentions to remain relationships and status as a family firm owner plays a social-environmental role in contextualizing social-cognitive relationships.

References

Aldrich, H. E., & Cliff, J. E. (2003). The pervasive effects of family on entrepreneurship: toward a family embeddedness perspective. Journal of Business Venturing, 18, 573–596. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-9026(03)00011-9.

Adams, G. A., King, L. A., & King, D. W. (1996). Relationships of job and family involvement, family social support, and work-family conflict with job and life satisfaction. Journal of Applied Psychology, 81, 411–420. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.81.4.411.

Bacq, S., Ofstein, L. F., Kickul, J. R., & Gundry, L. K. (2017). Perceived entrepreneurial munificence and entrepreneurial intentions: a social cognitive perspective. International Small Business Journal, 35(5), 639–659. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242616658943.

Bandura, A. (1989). Human agency in social cognitive theory. American Psychologist, 44(9), 1175. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.44.9.1175.

Barnett, T., Eddleston, K. A., & Kellermanns, F. W. (2009). The effects of family versus career role salience on the performance of family and nonfamily firms. Family Business Review, 22(1), 39–52. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894486508328814.

Beehr, T. A., Drexler Jr., J. A., & Faulkner, S. (1997). Working in small family businesses: empirical comparisons to non-family businesses. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 18, 297–312.

Benz, M. (2009). Entrepreneurship as a non-profit-seeking activity. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 5(1), 23–44.

Benz, M., & Frey, B. S. (2008). Being independent is a great thing: subjective evaluations of self-employment and hierarchy. Economica, 75(298), 362–383 https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0335.2007.00594.

Berrone, P., Cruz, C., Gomez-Mejia, L., & Larraza, M. (2010). Socioemotional wealth and organizational response to institutional pressures: do family controlled firms pollute less? Administrative Science Quarterly, 53(1), 82–113. https://doi.org/10.2189/asqu.2010.55.1.82.

Bing, M. N., & Burroughs, S. M. (2001). The predictive and interactive effects of equity sensitivity in teamwork-oriented organizations. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 22(3), 271–290. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.68.

Burke, A. E., Fitzroy, F. R., & Nolan, M. A. (2002). Self-employment wealth and job creation: the roles of gender, non-pecuniary motivation and entrepreneurial ability. Small Business Economics, 19(3), 255–270.

Burton, M. D., Sørensen, J. B., & Dobrev, S. D. (2016). A careers perspective on entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 40(2), 237–247 https://doi.org/10.1111/etap.12230.

Cardon, M. S., Foo, M. D., Shepherd, D., & Wiklund, J. (2012). Exploring the heart: entrepreneurial emotion is a hot topic. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 36(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2011.00501.

Carlson, D. S., & Kacmar, K. M. (2000). Work–family conflict in the organization: do life role values make a difference? Journal of Management, 26(5), 1031–1054. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920630002600502.

Carter, N. M., Gartner, W. B., Shaver, K. G., & Gatewood, E. J. (2003). The career reasons of nascent entrepreneurs. Journal of Business Venturing, 18(1), 13–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-9026(02)00078-2.

Carsrud, A., & Brännback, M. (2011). Entrepreneurial motivations: what do we still need to know? Journal of Small Business Management, 49(1), 9–26. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-627X.2010.00312.

Cassar, G. (2007). Money, Money, Money? A longitudinal investigation of entrepreneur career reasons, growth preferences, and achieved growth. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development, 19, 89–107. https://doi.org/10.1080/08985620601002246.

Chope, R. C. (2005). Qualitatively assessing family influence in career decision making. Journal of Career Assessment, 13(4), 395–414. https://doi.org/10.1177/1069072705277913.

Chrisman, J. J., Chua, J. H., Pearson, A. W., & Barnett, A. T. (2012). Family involvement, family influence, and family centered non-economic goals in small firms. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 36(2), 267–293 https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2010.00407.

Caliendo, M., Fossen, F., & Kritikos, A. S. (2014). Personality characteristics and the decisions to become and stay self-employed. Small Business Economics, 42(4), 787–814.

Cruz, C. C., Gómez-Mejia, L. R., & Becerra, M. (2010). Perceptions of benevolence and the design of agency contracts: CEO-TMT relationships in family firms. Academy of Management Journal, 53, 69–89. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMJ.2010.48036975.

Cruz, C., Justo, R., & De Castro, J. O. (2012). Does family employment enhance MSEs performance?: integrating socioemotional wealth and family embeddedness perspectives. Journal of Business Venturing, 27(1), 62–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2010.07.002.

Dawson, J. F., & Richter, A. W. (2006). Probing three-way interactions in moderated multiple regression: development and application of a slope difference test. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91(4), 917. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.91.4.917.

DeTienne, D. R. (2010). Entrepreneurial exit as a critical component of the entrepreneurial process: theoretical development. Journal of Business Venturing, 25(2), 203–215. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2008.05.004.

DeTienne, D. R., & Cardon, M. S. (2012). Impact of founder experience on exit intentions. Small Business Economics, 38(4), 351–374.

Dew, N., Grichnik, D., Mayer- Haug, K., Read, S., & Brinckmann, J. (2015). Situated entrepreneurial cognition. International Journal of Management Reviews, 17(2), 143–164. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijmr.12051.

Dyer, W. G. (1994). Toward a theory of entrepreneurial careers. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 19, 7–21.

Eddleston, K. A., & Powell, G. N. (2008). The role of gender identity in explaining sex differences in business owners’ career satisfier preferences. Journal of Business Venturing, 23, 244–256. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2006.11.002.

Eddleston, K. A., Veiga, J. F., & Powell, G. N. (2006). Explaining sex differences in managerial career satisfier preferences: the role of gender self-schema. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91(2), 437–445. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.91.2.437.

Feldman, D. C., & Bolino, M. C. (2000). Career patterns of the self-employed: career motivations and career outcomes. Journal of Small Business Management, 38(1), 53–67.

Feldman, D. C., & Ng, T. W. (2007). Careers: mobility, embeddedness, and success. Journal of Management, 33(3), 350. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206307300815.

Felfe, J., Schmook, R., Schyns, B., & Six, B. (2008). Does the form of employment make a difference? Commitment of traditional, temporary, and self-employed workers. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 72, 81–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2007.10.008.

Georgellis, Y., Sessions, J., & Tsitsianis, N. (2007). Pecuniary and non-pecuniary aspects of self-employment survival. The Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance, 47(1), 94–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.qref.2006.03.002.

Gomez-Mejia, L. R., Cruz, C., Berrone, P., & DeCastro, J. (2011). The bind that ties: Socioemotional wealth preservation in family firms. The Academy of Management Annals, 5(1), 653–707. https://doi.org/10.1080/19416520.2011.593320.

Greenhaus, J. H., & Powell, G. N. (2006). When work and family are allies: a theory of work-family enrichment. Academy of Management Review, 31(1), 72–92. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMR.2006.19379625.

Griffeth, R. W., Hom, P. W., & Gaertner, S. (2000). A meta-analysis of antecedents and correlates of employee turnover: update, moderator tests, and research implications for the next millennium. Journal of Management, 26(3), 463–488. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920630002600305.

Harman, D. (1967). A single factor test of common method variance. Journal of Psychology, 35, 359–378.

Headd, B. (2003). Redefining business success: distinguishing between closure and failure. Small Business Economics, 21(1), 51–61.

Hobfoll, S. E. (1989). Conservation of resources: a new attempt at conceptualizing stress. American Psychologist, 44(3), 513. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.44.3.513.

Hytti, U. (2010). Contextualizing entrepreneurship in the boundaryless career. Gender in Management: An International Journal, 25, 64–81. https://doi.org/10.1108/17542411011019931.

Ibrahim, A. B., Soufani, K., & Lam, J. (2001). A study of succession in a family firm. Family Business Review, 14(3), 245–258. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-6248.2001.00245.

Jennings, J. E., & McDougald, M. S. (2007). Work-family interface experiences and coping strategies: implications for entrepreneurship research. Academy of Management Review, 32(3), 747–760. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMR.2007.25275510.

Katz, J. A. (1994). Modelling entrepreneurial career progressions: concepts and considerations. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 19(2), 23–39.

King, L. A., Mattimore, L. K., King, D. W., & Adams, G. A. (1995). Family support inventory for workers: A new measure of perceived social support from family members. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 16, 235–258. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.4030160306.

Le, S. A., Kroll, M. J., & Walters, B. A. (2013). Outside directors’ experience, TMT firm-specific human capital, and firm performance in entrepreneurial IPO firms. Journal of Business Research, 66(4), 533–539. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2012.01.001.

Lent, R. W., Brown, S. D., & Hackett, G. (1994). Toward a unifying social cognitive theory of career and academic interest, choice, and performance. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 45(1), 79–122. https://doi.org/10.1006/jvbe.1994.1027.

Lent, R. W., Brown, S. D., & Hackett, G. (2000). Contextual supports and barriers to career choice: a social cognitive analysis. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 47(1), 36. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.47.1.36.

Lobel, S. A., & St. Clair, L. (1992). Effects of family responsibilities, gender, and career identity salience on performance outcomes. Academy of Management Journal, 35(5), 1057–1069. https://doi.org/10.2307/256540.

Maertz, C. P. Jr, & Griffeth, R. W. (2004). Eight motivational forces and voluntary turnover: A theoretical synthesis with implications for research. Journal of Management, 30(5), 667–683. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jm.2004.04.001.

Marshall, D. R. (2016). From employment to entrepreneurship and back: a legitimate boundaryless view or bias-embedded mindset? International Small Business Journal, 34(5), 683–700. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242615581853.

Miller, D., Breton-Miller, L., Minichilli, A., Corbetta, G., & Pittino, D. (2014). When do non-family CEOs outperform in family firms? Agency and behavioural agency perspectives. Journal of Management Studies, 51(4), 547–572. https://doi.org/10.1111/joms.12076.

Mitchell, J. R., Mitchell, R. K., & Randolph-Seng, B. (Eds.). (2014). Handbook of Entrepreneurial Cognition. Edward Elgar Publishing.

Mitchell, T. R., Holtom, B. C., Lee, T. W., Sablynski, C. J., & Erez, M. (2001). Why people stay: using job embeddedness to predict voluntary turnover. Academy of Management Journal, 44(6), 1102–1121. https://doi.org/10.2307/3069391.

Mitchell, R. K., Randolph-Seng, B., & Mitchell, J. R. (2011). Socially situated cognition: imagining new opportunities for entrepreneurship research. Academy of Management Review, 36(4), 774–776. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2011.0001.

Moshavi, D., & Koch, M. J. (2005). The adoption of family-friendly practices in family-owned firms: paragon or paradox? Community, Work, and Family, 8(3), 237–249. https://doi.org/10.1080/13668800500142210.

Pearson, A. W., Carr, J. C., & Shaw, J. C. (2008). Toward a theory of familiness: a social capital perspective. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 32(6), 949–969. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2008.00265.

Powell, G. N., & Eddleston, K. A. (2013). Linking family-to-business enrichment and support to entrepreneurial success: do female and male entrepreneurs experience different outcomes. Journal of Business Venturing, 28, 261–280. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2012.02.007.

Powell, G. N., & Eddleston, K. A. (2017). Family involvement in the firm, family-to-business support, and entrepreneurial outcomes: an exploration. Journal of Small Business Management, 55(4), 614–631. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12252.

Rogoff, E. G., & Heck, R. K. Z. (2003). Evolving research in entrepreneurship and family business: recognizing family as the oxygen that feeds the fire of entrepreneurship. Journal of Business Venturing, 18(5), 559–566. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-9026(03)00009-0.

Rosenbaum, J. E. (1979). Tournament mobility: career patterns in a corporation. Administrative Science Quarterly, 220–241.

Schein, E. H. (1995). The role of the entrepreneur in creating organizational culture. Family Business Review, 8(3), 221–238. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-6248.1995.00221.

Shane, S., Locke, E. A., & Collins, C. J. (2003). Entrepreneurial motivation. Human Resource Management Review, 13(2), 257–279. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1053-4822(03)00017-2.

Sharma, P. (2004). An overview of the field of family business studies: current status and directions for the future. Family Business Review, 17(1), 1–36. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-6248.2004.00001.

Sharma, P., & Irving, P. G. (2005). Four bases of family business successor commitment: antecedents and consequences. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 29(1), 13–33. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2005.00067.

Shepherd, D. A., Williams, T. A., & Patzelt, H. (2015). Thinking about entrepreneurial decision making: review and research agenda. Journal of Management, 41(1), 11–46. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206314541153.

Siemsen, E., Roth, A., & Oliveira, P. (2010). Common method bias in regression models with linear, quadratic, and interaction effects. Organizational Research Methods, 13, 456–476. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428109351241.

Smith, E. R., & Semin, G. R. (2004). Socially situated cognition: cognition in its social context. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 36, 53–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2601(04)36002-8.

Sundaramurthy, C., & Kreiner, G. E. (2008). Governing by managing identity boundaries: the case of family businesses. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 32(3), 415–436. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2008.00234.x.

Van Auken, H., & Werbel, J. (2006). Family dynamic and family business financial performance: spousal commitment. Family Business Review, 19(1), 49–63. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-6248.2006.00059.x.

Werner, A., Gast, J., & Kraus, S. (2014). The effect of working time preferences and fair wage perceptions on entrepreneurial intentions among employees. Small Business Economics, 43(1), 137–160.

Wiklund, J., Patzelt, H., & Shepherd, D. A. (2009). Building an integrative model of small business growth. Small Business Economics, 32(4), 351–374.

Walker, E., & Brown, A. (2004). What success factors are important to small business owners? International Small Business Journal, 22, 577–594. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242604047411.

Zahra, S. A. (2007). Contextualizing theory building in entrepreneurship research. Journal of Business Venturing, 22(3), 443–452. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2006.04.007.

Zahra, S., Hayton, J., Neubaum, D., Dibrell, C., & Craig, J. (2008). Culture of family commitment and strategic flexibility: the moderating effect of stewardship. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 32, 1035–1054. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2008.00271.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Full-item scales for dependent and independent variables

Intentions to remain an entrepreneur (α = .79):

I am going to remain self-employed, no matter what the problems are.

I often think about leaving self-employment and going back to work for an organization again (Reverse coded).

I fully intend to continue with my current self-employment situation.

If I have my own way, I will be self-employed 3 years from now.

Importance of status-based career satisfiers (α = .75)

Earning a lot of money

Having high prestige and social status

Being in a leadership role

Being highly regarded in my field

Growing a world-class business

Importance of employee relationship career satisfiers (α = .80)

Working with friendly and congenial people

Working as part of a team

Having supportive employees

Providing comfortable working conditions

Developing mutually beneficial relationships with employees

Perceptions of emotional support from family (α = .83)

When I talk with them about my business, family members don’t really listen (reverse coded).

When I have a problem at work, members of my family express concern.

Members of my family are interested in my business.

When I’m frustrated by my business, someone in my family tries to understand.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Marshall, D., Dibrell, C. & Eddleston, K.A. What keeps them going? Socio-cognitive entrepreneurial career continuance. Small Bus Econ 53, 227–242 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-018-0055-z

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-018-0055-z