Abstract

The challenge for economies lies in boosting employment growth, not just by fostering entrepreneurship, but also by improving the growth potential of existing firms. Consequently, many studies have focused on assessing the dynamism of firms, and especially the capacity of high-growth firms (HGFs) to generate employment. This study aimed to identify HGFs in Spain during two periods, 2003–2006 and 2007–2010 and to analyse their characteristics and territorial distribution during the initial years of the economic crisis. Accordingly, a key area of inquiry of the study was the influence of agglomeration (in metropolitan areas, industrial districts and technological districts) on the locations of HGFs. To analyse the influence of location on the probability of firms being HGFs, a logit model was estimated. The main results supported the study’s hypotheses that technological districts and large urban areas are significantly associated with the probability of firms being HGFs, because firms profit from comparative locational advantages offered by these areas. The importance of HGFs requires special emphasis in relation to Spain’s context of economic crisis and high unemployment levels because of their significant contribution to employment generation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In the last few decades, business dynamics has emerged as an attractive field of research. The focus of recent studies has been on the potential growth of firms and their capacity to create jobs as basic conditions for improving the adverse circumstances prevailing in many countries, such as Spain, as a result of the financial and economic crisis. Based on the premise that firms are the central pillars for improving economic growth, these studies have primarily focused on the capacity of firms to generate employment, especially in a context of high levels of unemployment. Thus, researchers have emphasised the pivotal role of entrepreneurship in fostering economic growth within countries. The failure of a single definition of entrepreneurship to emerge undoubtedly reflects the fact that it is a multidimensional concept (Audretsch 2003): new venture creations, new self-employment, intra-entrepreneurship… Therefore, the challenge for economies lies in boosting employment growth, not just by fostering new entrepreneurial activities, but also by improving the growth potential of existing firms.

Consequently, many studies have centred on an analysis of the dynamism of firms, and especially on the capacity of high-growth firms (HGFs) to generate employment. Despite the application of different methodologies in these studies, their results have revealed the same general pattern in relation to the remarkable contribution of a small group of firms to national employment growth. These firms have been defined as HGFs, with the youngest of them being termed ‘gazelles’ (Birch 1979; Gallagher and Miller 1991a; Birch and Medoff 1994; Kirchhoff 1994; Storey 1994; Birch et al. 1995; Autio et al. 2000; Schreyer 2000; Davidsson and Delmar 2003, 2006; Delmar et al. 2003; Acs and Mueller 2008; Bos and Stam 2011).

The concepts of HGFs and gazelles have been widely accepted and used to identify firms with a high rate of annual growth over a period of 3–4 years. Despite the application of varying definitions to these concepts, a generally valid conclusion is that a significant percentage of net employment has been generated by HGFs (Audretsch 2012). Furthermore, a positive relationship has been demonstrated between the existence of a significant percentage of HGFs and higher employment growth rates in many OECD countries (Hoffman and Junge 2006). The critical importance of these firms for national employment has sparked growing interest among scholars who have analysed the main characteristics of HGFs, focusing their attention on key elements of HGFs that contribute to processes of growth and employment generation.

Many of these studies have focused on the characteristics of firms and industries, identifying a set of internal factors such as age, size, behaviours and strategies that have an impact on the developmental process of HGFs (Delmar et al. 2003; Davidsson and Delmar 2006; Moreno and Casillas 2007; Anyadike-Danes et al. 2009; Falkenhall and Junkka 2009; Levratto et al. 2010; Bjuggren et al. 2010; Daunfeldt et al. 2013).

Focusing on the Spanish case, HGFs have mainly been analysed from a regional perspective (Hernández et al. 1999; Correa et al. 2003; Galve and Hernández 2007; Moreno and Casillas 2007; Amat et al. 2010) and, therefore, there are few findings that apply at the national level (López-García and Puente 2012; Segarra and Teruel 2014). In some cases, national level analyses have been conducted although only focused on gazelles (De la Vega 2007; EOI 2007). In general, these studies have highlighted the significant capacity of HGFs, such as the youngest HGFs in Catalonia, to create employment (Hernández et al. 1999; Amat et al. 2010). López-García and Puente (2012) have noted that at the national level, fast-growing firms, categorised according to OECD indicators, created more than 250,000 net jobs within just 3 years. Moreover, these firms only represented the 1.5 % of the total population of firms. It is clear that HGFs are an important source of employment (Segarra and Teruel 2014). In addition, based on their analyses of HGFs’ contribution to employment, several international studies ranked Spain among the most dynamic European economies (Schreyer 2000; Hoffman and Junge 2006; BERR 2008; Hölzl and Friesenbichler 2010).

Despite an increasing focus on HGFs, the review of the literature shows a clear lack of studies about the performance of HFG during the first years of the current economic crisis. The latest studies have been all conducted before the onset of the current economic crisis and, moreover, the most recent studies (Daunfeldt et al. 2015; Segarra and Teruel 2014) do not completely cover the initial years of the economic crisis. Due to a lack of evidence, this study tries to enhance the knowledge about the location and performance of HGF during a period characterised by an intense decline of the economic activity and high rates of unemployment.

Furthermore, little is known about the impact of location on the growth of firms (Acs and Armington 2004; Audretsch and Dohse 2007; St-Jean et al. 2008; Barbosa and Eiriz 2011; Bogas and Barbosa 2013). There are some studies that analyse the location of HGFs at regional level or in urban areas (Acs and Mueller 2008) although there is still not enough evidence about the influence of spatial agglomeration areas on the location of HGFs. The concentration of firms in areas as technological districts or large urban areas should be a factor with a significant influence on the location decision of firm. In addition, firms should also find the best conditions to achieve high-growth rates because the competitive advantages that are generated inside these areas. In that sense, this study tries to provide new evidence about the influence of location and, more specifically some types of agglomeration areas, on the probability of firms obtaining high-growth rates and, therefore, being HGFs.

Therefore, this study had two main objectives. The first objective was to identify HGFs and assess their contribution to employment during two periods, namely, 2003–2006 and 2007–2010, corresponding to the years before the onset of the economic crisis and the initial years after its onset, respectively. The selection of these two periods is appropriate given our intention to contribute to the literatures on entrepreneurship and the business cycle (Fritsch et al. 2013; Alcalde and Guerrero 2014; Sanchís et al. 2015). The analysis of location of HGFs was the second objective and, more specifically, to analyse the location of HGF in Spain and, more specifically, the location of HGF in different types of spatial agglomerations as industrial districts, technological districts, large firm areas and urban areas, especially large urban and metropolitan areas. Different competitive advantages generated inside these areas (i.e. easier access to advanced business services) could explain why concentrate a significant percentage of HGFs rather than in other locations.

Our data were primarily obtained from the Iberian Balance Sheet System (SABI) developed by Bureau van Dijk. The methodology entailed three steps: identification of HGFs, and their contribution to employment during two periods (2003–2006 and 2007–2010); a descriptive analysis of HGFs during the recession; and estimation of a logit model to test the influence of spatial agglomeration to ascertain whether agglomeration in areas such as large urban areas or technological districts influenced the probability of a firm being a HGF even in a general context of decrease in economic growth and rising unemployment.

The paper is organized as follows. The second section presents a review of the literature on HGFs, linking location with processes for developing high growth. The third section identifies HGFs in Spain and their locations based on an empirical study. The fourth section presents the results of estimation with a logit model to determine the main factors that influence the probability of firms being HGFs, with a particular focus on location. The final section presents the main conclusions of the study, highlighting its contributions, limitations and implications for future research.

A review of the literature on HGFs

Location as a factor in the development of high-growth firms

Location is considered an influential factor in the development of HGFs as this process can depend on the characteristics of the geographical environment (Acs and Armington 2004; Hoogstra and van Dijk 2004; Audretsch and Dohse 2007; St-Jean et al. 2008; Barbosa and Eiriz 2011; Bogas and Barbosa 2013).

Few studies have focused on the territorial dimension of HGFs, thereby providing empirical evidence on their locations. The conclusions of these studies also differ. Within the literature, there is agreement that HGFs can be found in all regions and in other types of territorial units. However, some studies have found that HGFs are disproportionately concentrated in urban areas (Acs and Mueller 2008) or in certain regions (Gallagher and Miller 1991b; Stam 2005). Conversely, others did not find any location effect (Vaessen and Keeble 1995; Davidsson et al. 2002; Audretsch 2012).

Thus, a review of the literature was conducted to compile empirical evidence that highlights the importance of agglomeration in relation to firms’ locations specifically in industrial districts (ID), local manufacturing systems of large firms (LFS), technological districts (TD) and large urban areas (LUA), and its influence on the competitiveness and growth of firms.

In general, locational benefits are associated with comparative advantages in terms of inputs, costs or market locations. They are also related to the effects of spatial agglomeration on firms. The literature on industrial districts and large firm systems and clusters reveals that environment is a key element that determines the competitiveness of firms concentrated within these spatial agglomerations. Several studies have emphasised the positive influence of intense interactions and cooperative links forged between firms and institutions located within industrial districts and clusters on the competitiveness of local firms (Becattini 1992; Bellandi 1986; Sforzi 1992; Brusco 1992; Porter 1990, 1998; Boix and Trullén 2011). In that sense, firm’s performance could be enhanced and, as a consequence, more employment can be generated in these areas. On the basis of these arguments, we propose the following hypothesis:

-

Hypothesis 1. A firm’s location in an Industrial District (ID) has a positive and significant effect on the probability of it being a HGF.

-

Hypothesis 2. A firm’s location in a Large Firm System (LFS) has a positive and significant effect on the probability of it being a HGF.

Many studies have emphasized that firms located in high technology areas can benefit from agglomeration economies and enhance their competitive advantages through easier access to knowledge flows generated by firms, public and private research centres and training institutes. Knowledge production by these agents represents the critical mass required to promote R&D projects (Camagni 1991; Audretsch and Feldman 1996; Russo 2002; Cooke et al. 2004; Acosta et al. 2011; Molina-Morales et al. 2014). Location within high-tech areas can, therefore, be considered an influential factor in the development of HGFs.

Based on these arguments, we hypothesize that:

-

Hypothesis 3. A firm’s location in a Technological District (TD) has a positive and significant effect on the probability of it being a HGF.

The environment of firms can also contribute to their growth, especially in metropolitan areas (Wiklund 1998). Large urban areas can facilitate firms’ access to advanced services, highly skilled workers within labour markets, knowledge, financial resources, risk capital firms, and high levels of public infrastructure and services (Glancey 1998; Eberts and McMillen 1999; Fujita et al. 1999; Fujita and Thisse 2002; Rosenthal and Strange 2004; Espitia-Escuer et al. 2015). The probability of achieving high growth is greater for firms located in areas characterised by industrial diversity and agglomeration of services than for firms that are not located in such areas. Thus, HGF status can be attributed to a significant extent to the environment of firms.

On the basis of these arguments, we propose the following hypothesis:

-

Hypothesis 4. A firm’s location in a Large Urban Area (LUA) has a positive and significant effect on the probability of it being a HGF

Characteristics of HGFs

Studies conducted on the characteristics of HGFs have provided strong empirical evidence of the existence of an inverse relationship between the size and age of a firm and its growth (Delmar et al. 2003; Davidsson and Delmar 2006; Moreno and Casillas 2007; Anyadike-Danes et al. 2009; Falkenhall and Junkka 2009; Levratto et al. 2010; Daunfeldt et al. 2013). Specifically, an inverse relationship between the age and growth of firms has been confirmed by studies conducted in countries such as the UK (Dunne and Hughes 1994; Storey 1999), Italy (Arrighetti and Lasagni 2013) and Spain (López-García and Puente 2012).

Moreover, studies of HGFs have revealed that a sector of activity has an ambiguous effect on the process of growth of these firms. Cross-sectoral studies have revealed overrepresentation of HGFs in the service sector (Henrekson and Johansson 2010). Other studies have determined that there is a higher probability of finding HGFs within knowledge-intensive sectors than within traditional manufacturing sectors that are associated with a very low HGF presence (Levratto et al. 2010). However, some researchers have argued that other elements such as marketing activities and successful strategic management can generate competitive advantages that determine a firm’s expanded growth (Porter 1998). Although the percentage of HGFs in sectors characterized by low technology, mature markets or economic decline should be lower in comparison to contrasting sectors, these firms can, in fact, be found within any economic sector (Davidsson and Delmar 2006; Anyadike-Danes et al. 2009; Coad and Hölzl 2010).

In relation to the internal variables of firms, both financial and capital structures have been found to influence the growth process of small and medium enterprises (Moreno and Casillas 2007; Bjuggren et al. 2010; Levratto et al. 2010). Specifically, in their analysis of a firm’s profit, Moreno and Casillas (2007) found that HGFs had lower solvency and liquidity than other firms.

Even though there has been an increasing focus on HGFs and their relevance, there is still no evidence regarding the performance of HGFs in Spain during the last economic crisis. Moreover, a review of the literature revealed the absence of location as an explanatory factor in HGF development. Our study, therefore, contributes to the literature through an analysis of the characteristics of HGFs and their contribution to employment in Spain in the context of business cycles, while enhancing the knowledge base regarding the location of HGFs in Spain.

An empirical analysis of HGFs in Spain

Methodology and data

The study applied the definition of HGF provided by the OECD (2007) to identify such firms and their locations within Spain. Following this definition, here a HGF refers to a firm with an average annualised growth in employment, or turnover, exceeding 20 % in a 3-year period.Footnote 1 In addition, firms must have 10 or more employees at the beginning of the analysis period to qualify as HGFs.

Our data were primarily obtained from SABI which provides information on 1.25 million firms in Spain.Footnote 2 A data set was selected with representatives from all sectors reflecting the evolution of firms between 2003 and 2010. This period was then divided into two phases: 2003–2006 and 2007–2010. The latter period encompassed the initial years of the economic crisis and constituted the main analysis period. There were two prerequisites for selecting firms. The first was a minimum firm size comprising 10 employees at the beginning of each period. The second was the stipulation that the selected firms were active at the end of each period. Application of these filters yielded data on 126,330 firms for the first period and 84,861 firms for the second period. Growth criteria based on OECD’s (2007) definition of HGFs were then applied to these datasets.

The location analysis is focused on the following three categories:

-

Specialised areas: industrial districts (IDs), local manufacturing systems of large firms, or large firm systems (LFSs) and technological districts (TDs);

-

Urban areas, including small urban areas (SUAs) with populations of between 10,000 and 50,000 inhabitants and large urban areas (LUAs) with more than 50,000 inhabitants;

-

The metropolitan areas of Madrid, Barcelona, Valencia, Sevilla and Bilbao.

The location analysis of HGF in industrial districts uses the identification of 205 industrial districts in Spain carried out by Boix and Galletto (2006). These authors identify local labour systems of small and medium firms that are specialised in manufacturing. In addition, the main industry in which the district is specialised is also comprised by small and medium enterprises. In general, IDs are associated with traditional and mature industrial sectors (textiles, footwear, ceramic tiles and other low-tech sectors. In the case of Manufacturing Local Systems of Large Firms, Boix and Trullén (2011) identified 66 manufacturing systems with a predominance of large firms in the main industrial specialisation. Finally, we define technological districts as territorial agglomerations that concentrate not only high technology manufacturing but also high technology research. In general, TDs are associated with high-tech sectors (industry and services), and agglomeration advantages are based on urbanisation and structural diversification. To identify HGF in these areas, we use the contribution by Santa María et al. (2012) in which 39 technological districts are identified in Spain. We followed the definitions of urban areas contained in the Statistical Atlas of Urban Areas of the Spanish Infrastructures Ministry for LUAs and SUAs.Footnote 3

Identification of HGFs and their contribution to employment

The results of the analysis indicate that between 2003 and 2006 when the Spanish economy was still growing, percentages of HGFs by employment and turnover of firm populations were 5.7 and 13.2 %, respectively (see Table 1). This percentage rose to 15.5 % when both variables in the definition of HGFs were used indistinctly. When they were applied together to identify HGFs, the percentage was 3.4 %.

Comparing these results with those obtained for the period 2007–2010, the percentages for the latter period were significantly lower. HGFs by employment represented only 2.8 % of firms, while the percentage of HGFs by turnover was 7.8 %. Moreover, the percentage of HGFs by employment, or by turnover, declined to 9 % and further to just 1.6 % when both variables were used together to identify these firms.

During both periods, percentages of HGFs corresponded with those obtained by other studies. According to a study by OECD (2009), the number of HGFs, defined by employment, ranged from 3 to 6 % and those defined by turnover ranged from 8 to 12 %. In the case of Spain, it is evident that during the growth period (2003–2006) percentages of HGFs remained close to the upper limit of the range. However, with the onset of recession, they dropped below the minimum values of the ranges cited for the OECD study.

During the first expansionary period, 565,000 new employment positions were created by HGFs, resulting in a growth rate of 71.8 %. By contrast, other firms suffered a total loss of nearly 875,000 jobs.Footnote 4 Because of these different paths in the evolution of employment between 2003 and 2006, the weight of HGFs increased from 12 % to more than 22 % of the total population of firms. The remarkable increase in turnovers (128.7 %) achieved by HGFs during this period is noteworthy, while the turnovers of other firms grew by just 5.9 %.

Despite the economic crisis that prevailed during the period 2007–2010, the employment growth rate achieved by HGFs in Spain exceeded 50 %, implying the creation of 200,000 new jobs, while 600,000 jobs were lost in other firms during the same period.Footnote 5 These results highlight the considerable importance of HGFs as these firms were able to create employment even during an economic crisis. Similarly, turnovers of HGFs were high (70.1 %), while other firms experienced a drop of 20 % in turnovers. As a result, the weight of HGFs in the total population of firms grew during this period, not only because of their own growth, but also because of the job losses and turnover reduction of other firms.

Therefore, the positive expansion of HGFs has contrasted markedly with the general tendency of decreasing employment and turnovers caused by the recession that Spain has endured since 2008. Evidently, employment created by HGFs has reduced or even counteracted the impacts of massive job cuts implemented by other firms.

Location and characteristics of HGFs during the period 2007–2010

Rising interest in HGFs and their performance between 2007 and 2010Footnote 6 can be attributed to their capacity to create new employment not only during a period of economic growth, but also during the crisis years when Spain recorded its highest unemployment rate in decades. As previously discussed, although HGFs represented only 9 % (by employment or turnover) of the total number of firms, they have been able to generate more than 200,000 new jobs.

As Table 2 shows, a significant percentage of HGFs (36.2 %) can be defined as gazelles (in existence for five or less years). These younger firms have contributed 22.6 % of the overall employment generated by HGFs. In addition, a higher percentage of HGFs correlates with a decrease in the age of firms. This confirms our assumption that there is an inverse relationship between age and a high level of growth of firms, discussed in section two.

Our analysis of the size of firms revealed over-representation of small and medium HGFs, although large HGFs (with more than 250 employees) had significant weight in their size category. Evidently, large firms are an important source of jobs in absolute terms. However, small and medium HGFs have made a greater contribution to net employment growth as their average growth rate is near 60 %.

We analysed the firms’ technological intensity levels by applying the technological classification framework developed by the Spanish National Statistics Institute (INE). This classification framework, using the National Classification of Economic Activities, includes three main categories: high-tech manufacturing activities, medium-high-tech manufacturing activities and high-tech services.Footnote 7 The results of our analysis, shown in Table 3, reveal that HGFs were mainly concentrated in high-tech sectors, especially high-tech services for which the percentage of HGFs was significantly higher than that of HGFs engaged in other activities.

The location analysis is focused on industrial or technological activities specialised areas, such as industrial or technological districts, as well as on metropolitan or large urban areas.Footnote 8

As Table 4 shows, the density of HGFs in Spain was greater in TDs than in other specialised areas. Thus, 45.64 % of HGFs (3481 firms) were located in TDs, accounting for 10 % of the total firm population in these areas. These results correlate with the empirical evidence (reviewed in section two) on the high probability of finding HGFs in knowledge-intensive and high-tech service sectors. Conversely, numbers of HGFs located in IDs and LFSs were significantly lower than those in TDs. It was observed that the average employment growth of HGFs in all four specialised areas was at least 40 % higher during the period 2007–2010, while employment was slashed by the rest of the firms during this period.

The results of the analysis also revealed a high concentration of HGFs in LUAs (50.3 % of all HGFs) and especially in the metropolitan areas of Madrid and Barcelona (30 % of all HGFs). This latter percentage is remarkable as these metropolitan areas represent 24 % of the total population of firms. In addition, it should be noted that these metropolitan areas have also been identified as TDs. These results support the hypothesis that urbanisation economies are a significant factor in the location of HGFs that aim to profit from the comparative advantages offered by urban areas.

At the municipal level, some municipalities have a relatively high number of HGFs considering their firm populations. To identify the most dynamic municipalities, two filters were applied. The first stipulation was that a municipality should have at least five HGFs. The second stipulation was that the percentage of HGFs in relation to the total population of firms was at least twice the national average. The application of these filters yielded 36 municipalities, that is, 4.14 % of the total number of HGFs, with these firms also representing 18–30 % of the total firm population. Table 5 shows that of the top 10 municipalities, ranked by the number of HGFs within them, Alcobendas and Tres Cantos, in the Madrid region, accounted for 71 HGFs or 22 % of the HGFs in the 36 municipalities analysed in the study. These two municipalities were characterised by their proximity to the main towns (less than 15 km). In addition, they belonged to Madrid’s metropolitan area. The results of the analysis for the municipality of La Rinconada, which is located in close proximity to Seville, were similar.

In sum, a significant percentage of HGFs were concentrated in TDs (which include both metropolitan and other urban areas such as Madrid or Barcelona). Therefore, the potential growth in employment of these areas could have been greater than that in other areas because of high-tech activities developed within them. The next section presents a more in-depth analysis to estimate the influence of these areas and other variables on the probability of a firm achieving high growth.

Econometric analysis

We analysed the influence of the selected variables on the probability of a firm being an HGF during the period 2007–2010.Footnote 9 To do so, we estimated a logit model where the dependent variable was defined as a binary variable, with a value of 1 assigned to HGFs and 0 to other firms. The logit model was expressed as follows:

The probabilities of the dependent variable indicating ‘success’ (being an HGF) and ‘failure’ (not being an HGF) were defined as follows:

A logit model is more efficient than a linear probability model at estimating probability related to a binary variable. For example, marginal effects are taken as fixed in the linear probability model as Pr(Y=1/X) increases linearly with X. However, because probability in a logit model is expressed as a non-linear function that includes independent variables, marginal effects can be estimated to enable changes in Pr(Y=1/X) to be observed when one independent variable varies in one unit.

Specifically, we used the following specifications for the logit model:

where HGF, as the dependent binary variable, took a value of 1 if firm i was identified as an HGF (a firm that had achieved high growth in employment and/or turnover). For other firms, a value of 0 was assigned.

Based on the data, and on the theoretical and empirical perspectives discussed in section two, we considered the following explanatory variables included in the vector Loci as dummy variables: IDs, LFSs, TDs, and LUAs (this category includes metropolitan areas and urban areas with more than 50,000 inhabitants).

We proposed four hypotheses to test locational influence in relation to agglomeration:

-

H1. A firm’s location in an ID has a positive and significant effect on the probability of it being a HGF.

-

H2. A firm’s location in an LFS has a positive and significant effect on the probability of it being a HGF.

-

H3. A firm’s location in a TD has a positive and significant effect on the probability of it being a HGF.

-

H4. A firm’s location in a LUA has a positive and significant effect on the probability of it being a HGF.

To control for firm-specific characteristics, we added the following internal variables. Agei was the firm’s age at the beginning of the analysis period (2007). Log_Employmenti was the log of the number of workers at the beginning of the analysis period. Economic Profitabilityi was the ratio of operational results before interest and tax to total assets at the beginning of the analysis period. Debt Ratioi was the ratio of total debt to total assets at the beginning of the analysis period. Techi was a vector that included dummy variables for the technological levels of firms, with the category ‘non-technological firms’ used as the base reference for the parameter estimation. The last variable, \( {\varepsilon}_i, \) was a random error term. Each of these variables is listed and described in Table 6 which also indicates the expected effect for location variables. As the last step, four models were estimated for each type of area included in the variable Loci.

Here, we discuss some considerations related to the database used for our study. Our sample entailed a sizeable gap in the number of firms included in each of the two groups of firms (HGFs and non-HGFs). Thus, the ratio of HGFs to the total sample was 1 to 10. In a seminal work, Cramer (1999) posited that if the number of HGFs was very low compared with that of the rest of the firms, estimation of the probabilities associated with HGF = 1 could be lower than those related to non-HGFs. Consequently, the goodness-of-fit of the logit model could have been poor because of the unbalanced sample.Footnote 10 Therefore, we obtained a random stratified sample by size and activity sector for non-HGFs for the estimation of our logit model. Consequently, the sample for non-HGFs was also balanced in terms of size and sector of activityFootnote 11 compared with the same categories for HGFs. In addition, a multicollinearity test was applied to all of the variables.Footnote 12

Table 7 shows the results of the estimation. It includes information on the values used for testing the goodness-of-fit of the model and on the Hosmer-Lemeshow values regarding the predictive capacity of the model. The Cox-Snell R-squared and Nagelkerke R-squared values indicated that the model was robust and that its predictive value was 64 %.

The influence of agglomeration appeared to be significant. As the results for Model 3 indicate, a firm located in a TD had a significant probability of being an HGF. Conversely, a negative and significant effect was associated with IDs (Model 1). These contrasting results can be attributed to the defining characteristics of these two areas in relation to agglomeration. Therefore, it is difficult for a firm located in one ID to find opportunities to achieve strong growth within a short period of time, despite the competitive advantages offered by these areas. By contrast, the a combination of competitive advantages (e.g., knowledge spillovers, highly qualified human capital and advanced services) in TDs, and high growth rates of some sectors (e.g., internet services), places firms in a better position to achieve high growth at a fast pace.

The results for Model 4, relating to the effects of urban economies and other competitive advantages, support the assertion that LUAs have a positive and significant effect on the probability of a firm being a HGF. As many TDs are also LUAs, this result was anticipated. It also indicated that the values of the coefficients for TDs and for LUAs were very similar. Lastly, our results indicated that LFSs as firm locations (Model 2) did not favour the presence of HGFs despite offering the advantages of specialisation.

In sum, the results obtained for the models confirmed hypotheses H3 and H4. However, there was no evidence to support hypotheses H1 and H2.

These results confirm the importance of location in high-tech areas. Firms can benefit from agglomeration economies and enhance their competitive advantages through easier access to knowledge flows generated by firms, public and private research centres and training institutes. (Camagni 1991; Audretsch and Feldman 1996; Russo 2002; Cooke et al. 2004; Acosta et al. 2011; Molina-Morales et al. 2014).

Also, our results imply that the environment of firms can also contribute to their growth, especially in metropolitan areas (Wiklund 1998). Large urban areas can facilitate firms’ access to advanced services, highly skilled workers within labour markets, knowledge, financial resources, risk capital firms, and high levels of public infrastructure and services (Glancey 1998; Eberts and McMillen 1999; Fujita et al. 1999; Fujita and Thisse 2002; Rosenthal and Strange 2004; Espitia-Escuer et al. 2015).

Our findings differ from those by the literature on industrial districts and large firm systems and clusters reveal that environment is a key element that determines the competitiveness of firms concentrated within these spatial agglomerations (Becattini 1992; Bellandi 1986; Sforzi 1992; Brusco 1992; Porter 1990, 1998; Boix and Trullén 2011). The different results may depend on differences in the time period considered (great economic and industrial recession).

As it has mentioned in “Location as a factor in the development of high-growth firms” subsection, different studies about the location of HGFs points out to the argument that HGF are not concentrated in any particular region or at any special location and, moreover, tend to be diffused across geographic space (i.e. Audretsch 2012). However, our results suggest that HGFs tend to benefit from being located in geographic clusters and agglomerations, especially technological districts and metropolitan areas. These results are, therefore, in line with those obtained by authors as Stam (2005) or Acs and Mueller (2008) about the concentration of these firms in specific areas or regions.

The results obtained for the control variables were stable for all of the models, and the estimated parameters conformed to the empirical evidence discussed in section two. The results also indicated that there was an inverse and significant relationship between the ages of firms and the probability of their being HGFs. This result corresponds to that of other empirical studies (discussed in “A review of the literature on HGFs” section). Moreover, it supports the hypothesis that younger firms may show a higher probability of achieving high growth than older firms. The variables of economic profitability and debt ratio were also found to be significant, implying that they may play an important role in the growth process of firms. When the technology level of firms was introduced within the model, high-tech industries and, especially services, were found to have strong and positive effects on the probability of a firm being a HGF.

Conclusions

Studies that have focused on the dynamics of firms have highlighted the considerable importance of HGFs. Although these firms represent a low percentage of the total population of firms they contribute significantly to employment creation. Consequently, they have been the focus of this study, given that Spain is undergoing a deep economic crisis associated with the highest levels of unemployment within the European Union. Since 2008, unemployment figures have steadily risen, although a group of firms (mainly HGFs) have been able to generate new jobs. The descriptive analysis conducted for this study provides evidence on the positive contribution of HGFs during the economic recession between 2007 and 2010, despite the fact that they only represented 9 % of the total firm population. Net employment within HGFs grew by 54.1 %, although these new jobs were not sufficient to counteract the strong growth of unemployment. The economic importance of HGFs was evident during both expansionary and recessionary periods. These findings are transferable for conducting international comparative studies using a methodology to identify HGFs that is endorsed by the OECD.

Therefore, an essential aspect of fostering economic development is providing support to HGFs, because these firms usually lead innovation and employment generation. The findings of this research show that HGFs are mainly associated with high-tech activities, and especially high-tech services, with significantly higher percentages of HGFs engaged in these activities compared with other activities. We also examined the locations of HGFs, focusing, in particular, on the role of spatial agglomeration. Overall, the results of the study indicated that the high probability of a firm being an HGF could be linked with the following profile: a high-tech firm (especially a high-tech services firm) located within a TD or a LUA.

A number of policy recommendations can be drawn from these results. First, however, we wish to emphasise that heterogeneity in the characteristics of HGFs hinders the design of an overall policy to support the development and consolidation of such enterprises. A micro-level policy design that is territorially and/or sectorally based may be the most appropriate one in this context. Therefore, a priority for policymakers should be to encourage the creation of firms within areas that specialise in high-tech industrial sectors and services, not only to boost the probability of creating new employment, but also to foster the creation of new firms based on innovation, R&D and knowledge activities. Another argument that support this statement is that a significant percentage of young firms (the 22 % of firms up to 5 years old) are HGF; so, it is essential to introduce policy initiatives that support and promote new firms as a path towards the creation of employment opportunities to reduce the current high levels of unemployment.

Several studies have noted that the process of determining which firms will become HGFs and when this will occur is very complex. Nevertheless, there are some economic policy measures that can be applied to foster the growth of firms. These include enhancement of the entrepreneurial environment, promotion of entrepreneurship, helping firms (especially small and medium-sized firms) to access more financial resources or fostering R&D and innovation activities. In the same line, as Davidsson and Delmar (2006) suggest, economic policies should be designed to support HGFs within every sector to promote employment generation.

The contribution of HGFs to growth and employment has evidently been outstanding considering the negative consequences of the recent economic crisis such as the record level of unemployment in Spain. Furthermore, HGFs can continue to play a key role once the Spanish economy returns to a path of positive economic growth. Because a significant number of HGFs are associated with innovative and high-tech activities, their contribution is essential for strengthening the structure of the Spanish economy over the coming years. These findings should influence the design of economic policies in support of business growth.

Two recent studies have sought to illustrate the best approaches for orienting policy-makers to support fast-growing companies. The first study by Kolar (2014), conducted for the European Union, analysed policies for supporting high-growth innovative enterprises. The second study, conducted by Brown and Mason (2013), focused on policies that support emerging growth companies.

In addition, the literature identifies a number of key policies to promote high growth firms. One important policy is to improve the business environment. A particular emphasis should be on reducing or removing obstacles to growth, such as regulatory burdens and administrative red tape. These barriers to growth should be investigated in-depth, as Audretsch (2012) suggest, to increase the efficiency of those policies designed to promote HGFs. Nevertheless, the Spanish Government have introduced a restrictive tax regulation that reduce the incentives for firms to increase their size. As a higher fiscal tax is applied when a turnover of more than six million euros is reached, firms are discouraged to growth up to this level. Moreover, different regional regulations and limitations to access to financial external resources are also elements that are hindering firm’s growth in Spain.

This study is not without limitations. First, the database used for the study did not provide exhaustive information about multi-plant firms and, therefore, the location analysis was limited to firm-level data. In addition, information about mergers and acquisitions was also not available. Other limitations were associated with the OECD definition of HGF used in the study. On the one hand, this definition did not take into account businesses with less than 10 employees (thereby excluding the dynamics of micro-firms). However, the OECD (2007) recommends not to include these firms as the analysis can be biased as firms growing from only one to two employees would be considered a HGF despite their micro size. On the other hand, only firms that were active at the beginning and at the end of the analysis period were considered. Thus, new jobs created by new firms during the analysis period, as well as the effect of closure of companies, were not considered. Finally, the location analysis is limited as it has been only focused on areas of agglomeration and, also, a comprehensive analysis was not conducted for the period of economic prosperity.

Moreover, some issues of inquiry will need to be addressed in future studies. These include an analysis of a specific group of HGFs such as gazelles (the youngest HGFs), in-depth analysis of location based on other types of territorial units or to include new explanatory frameworks such as the relevance of economies of agglomeration or the performance of HGFs that are located in rural areas.

Notes

Other studies have used indicators such as Birch’s index that defines growth of employment, turnover or other variables as (Xt1 - Xt0)(Xt1/Xt0), where X is the variable being analysed.

This database does not provide exhaustive information about multi-plant firms as it only includes information about the firm’s headquarters. Therefore, location analysis was limited to firm-level data. Information about mergers and acquisitions was also not provided.

This publication defines LUAs as areas that have just one municipality with more than 50,000 inhabitants or a group of municipalities with at least one of them comprising more than 50,000 inhabitants. SUAs are defined as follows: cities with a population of between 20,000 and 50,000 inhabitants and urban municipalities with a population of between 10,000 and 20,000 inhabitants. There are 748 LUAs and 325 SUAs in Spain.

The dataset used here only includes firms with 10 or more employees. Therefore, new jobs created by smaller and new firms established during the periods 2003–2006 and 2007–2010 were not considered in this analysis.

A greater reduction of employment must be considered in light of the number of firms that closed down during the period 2007–2010. These are not included here.

Analysis for the period 2003–2006 was not possible as enterprise-level microdata were not available for this period.

A complete list of the economic sectors included in each category can be viewed at: http://www.ine.es/en/daco/daco43/notaiat_en.pdf (accessed January 28, 2015).

A high level of regional concentration can be clearly observed, with four regions accounting for 60 % of HGFs: Catalonia (21.1 %), Madrid (13.3 %), Andalucía (12.5 %) and the Valencian Region (11.5 %). A large number of specialised areas in Spain are also concentrated in these regions.

Estimation was not possible for the period 2003–2006, because enterprise-level microdata were not available for this period.

The estimation of the model using the whole dataset showed 97 % predictive accuracy (Total). However, only 3 % was correctly predicted for HGF = 1 (Yes)

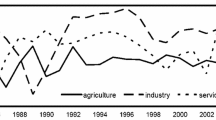

The sample was obtained using the following basic sectoral classification: agriculture, industry, services and construction.

A linear regression was estimated to obtain collinearity statistics, enabling the removal of those variables with a Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) higher than 10. This process was carried out repeatedly to obtain the final data set.

References

Acosta, M., Coronado, D., & Flores, E. (2011). University spillovers and new business location in high-technology sectors: Spanish evidence. Small Business Economics, 36, 365–376. doi:10.1007/s11187-009-9224-4.

Acs, Z. J., & Armington, C. (2004). The impact of geographic differences in human capital on service firm formation rates. Journal of Urban Economics, 56(2), 244–278. doi:10.1016/j.jue.2004.03.008.

Acs, Z. J., & Mueller, P. (2008). Employment effects of business dynamics: mice, gazelles and elephants. Small Business Economics, 30(1), 85–100. doi:10.1007/s11187-007-9052-3.

Alcalde, H., & Guerrero, M. (2014). Open business models in entrepreneurial stages: evidence from young Spanish firms during expansionary and recessionary periods. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 1–21. doi: 10.1007/s11365-014-0348-x.

Amat, O., Fontrodona, J., Hernández, J. M., & Stoyanova, A. (2010). Les empreses d’alt creixement i les gaseles a Catalunya. Papers d’Economia Industrial, 29, Generalitat de Catalunya.

Anyadike-Danes, M., Bonner, K., Hart, M., & Mason, C. (2009). Measuring business growth. High-growth firms and their contribution to employment in the UK. London: NESTA.

Arrighetti, A., & Lasagni, A. (2013). Assessing the determinants of high-growth manufacturing firms in Italy. International Journal of the Economics of Business, 20(2), 245–267. doi:10.1080/13571516.2013.783456.

Audretsch, D. B. (2003). Entrepreneurship: A survey of the literature. Enterprise Papers, 14, European Commission.

Audretsch, D. B. (2012). Determinants of high-growth entrepreneurship. OECD/DBA International Workshop on “High-growth firms: local policies and local determinants”, Copenhagen, 28 March 2012. http://www.oecd.org/cfe/leed/Audretsch_determinants%20of%20high-growth%20firms.pdf. Accessed 5 Mar 2014.

Audretsch, D. B., & Dohse, D. (2007). Location: a neglected determinant of firm growth. Review of World Economics, 143(1), 33–45. doi:10.1007/s10290-007-0099-7.

Audretsch, D. B., & Feldman, M. P. (1996). R&D spillovers and the geography of innovation and production. American Economic Review, 86, 630–640.

Autio, E., Arenius, P., & Wallenius, H. (2000). Economic impact of gazelle firms in Finland, Working Papers Series, 2000(3). Helsinki University of Technology, Institute of Strategy and International Business.

Barbosa, N., & Eiriz, V. (2011). Regional variation of firm size and growth: the Portuguese case. Growth and Change, 42(2), 125–158. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2257.2011.00547.x.

Becattini, G. (1992). El distrito industrial marshalliano como concepto socioeconómico. In F. Pyke, G. Becattini, & W. Sengenberger (Eds.), Los distritos industriales y las pequeñas empresas I. Distritos industriales y cooperación interempresarial en Italia (pp. 61–79). Madrid: Ministerio de Trabajo y Seguridad Social.

Bellandi, M. (1986). El distrito industrial en Alfred Marshall. Estudios Territoriales, 20, 31–44.

BERR (Department for Business, Enterprise and Regulatory Reform) (2008). High growth firms in the UK: Lessons from an analysis of comparative UK performance. Economics Paper, 3.

Birch, D. L. (1979). The job generation process. Cambridge: Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Birch, D. L., & Medoff, J. (1994). Gazelles. In L. C. Solmon & A. R. Levenson (Eds.), Labor markets, employment policy and job creation. Boulder: Westview Press.

Birch, D. L., Haggerty, A., & Parsons, W. (1995). Who’s creating jobs? Boston: Cognetics.

Bjuggren, C.M., Daunfeldt, S.O., & Johansson, D. (2010). Ownership and high-growth firms. Working Paper, 147. Stockholm: The Ratio Institute.

Bogas, P., & Barbosa, N. (2013). High-growth firms: what is the impact of region-specific characteristics? NIPE Working Papers, 19/2013. NIPE - Universidade do Minho.

Boix, R., & Galletto, V. (2006). El nuevo mapa de los distritos industriales de España y su comparación con Italia y el Reino Unido. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting for the Spanish Regional Science Association, Ourense, November 16–28.

Boix, R., & Trullén, J. (2011). La relevancia empírica de los distritos industriales marshallianos y los sistemas productivos locales manufactureros de gran empresa en España. Investigaciones Regionales, 19, 75–96.

Bos, J., & Stam, E. (2011). Gazelles, industry growth and structural change. Working Paper, 11–02. Utrecht School of Economics.

Brown, R., & Mason, C. (2013). Creating good public policy to support high growth firms. Small Business Economics, 40(2), 211–225.

Brusco, S. (1992). El concepto de distrito industrial: su génesis. In F. Pyke, G. Becattini, & W. Sengenberger (Eds.), Los distritos industriales y las pequeñas empresas I. Distritos industriales y cooperación interempresarial en Italia (pp. 25–37). Madrid: Ministerio de Trabajo y Seguridad Social.

Camagni, R. (1991). Innovation networks: Spatial perspectives. London: Belhaven.

Coad, A., & Hölzl, W. (2010). Firm growth: Empirical analysis. Papers on Economics and Evolution, 1002. Max Planck Institute of Economics.

Cooke, P., Heidenreich, M., & Braczyk, H. J. (2004). Regional innovation systems: The role of governance in a globalized world. London: Routledge.

Correa, A., Acosta, M., González, A. L., & Medina, U. (2003). Size, age, activity sector on the growth of the small and medium firm size. Small Business Economics, 21, 289–307. doi:10.1023/A:1025783505635.

Cramer, J. S. (1999). Predictive performance of the binary logit model in unbalanced samples. The Statistician, 48(1), 85–94. doi:10.1111/1467-9884.0017.

Daunfeldt, S. O., Elert, N., & Johansson, D. (2013). The economic contribution of high-growth firms: do policy implications depend on the choice of growth indicator? Journal of Industry, Competition and Trade. doi:10.1007/s10842-013-0168-7.

Daunfeldt, S. O., Elert, N., & Johansson, D. (2015). Are high-growth firms overrepresented in high-tech industries? Industrial and Corporate Change. doi:10.1093/icc/dtv035.

Davidsson, P., & Delmar, F. (2003). Hunting for new employment: The role of high-growth firms. In D. A. Kirby & A. Watson (Eds.), Small firms and economic development in developed and transition economies: A reader (pp. 7–19). Hampshire: Ashgate.

Davidsson, P., & Delmar, F. (2006). High-growth firms and their contribution to employment: The case of Sweden. In F. Delmar & J. Wiklund (Eds.), Entrepreneurship and the growth of firms (pp. 156–178). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Davidsson, P., Kirchhoff, B., Hatemi-J, A. & Gustavsson, H. (2002). Empirical Analysis of Employment Growth Factors Using Swedish Data. Journal of Small Business Management, 40(4), 332--349.

De la Vega, I. (Ed.) (2007). Análisis de crecimiento en la empresa consolidada española. Dirección General de Política de la Pequeña y Mediana Empresa. Madrid: Ministerio de Industria, Turismo y Comercio.

Delmar, F., Davidsson, P., & Gartner, W. B. (2003). Arriving at the high-growth firm. Journal of Business Venturing, 18, 189–216. doi:10.1016/s0883-9026(02)00080-0.

Dunne, P., & Hughes, A. (1994). Age, size, growth and survival: UK companies in the late 1980’s. Journal of Industrial Economics, 422, 115–140. doi:10.2307/2950485.

Eberts, R. W., & McMillen, D. P. (1999). Agglomeration economies and urban public infrastructure. In P. Cheshire & E. S. Mills (Eds.), Handbook of regional and urban economics (Vol. 3, pp. 1455–1495). Amsterdam: Elsevier Science.

Escuela de Organización Industrial. (2007). La creación de empresas en España: Un enfoque sectorial y territorial. Madrid: Escuela de Organización Industrial.

Espitia-Escuer, M., García-Cebrián, L. I., & Muñoz-Porcar, A. (2015). Location as a competitive advantage for entrepreneurship an empirical application in the Region of Aragon (Spain). International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 11(1), 133–148.

Falkenhall, B., & Junkka, F. (2009). High-growth firms in Sweden 1997–2007. Characteristics and development patterns. Stockholm: The Swedish Agency for Growth Policy Analysis.

Fritsch, M., Kritikos, A., & Pijnenburg, K. (2013). Business cycles, unemployment and entrepreneurial entry-evidence from Germany. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 11(2), 267–286.

Fujita, M., & Thisse, J. F. (2002). Economics of agglomeration. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Fujita, M., Krugman, P., & Venables, T. (1999). The spatial economy: Cities, regions, and international trade. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Gallagher, C., & Miller, P. (1991a). New fast-growing companies create jobs. Long Range Planning, 241, 96–101. doi:10.1016/0024-6301(91)90029-n.

Gallagher, C., & Miller, P. (1991b). The performance of new firms in Scotland and the South East, 1980–7. Royal Bank of Scotland Review, 170, 38–50.

Galve, C., & Hernández, A. (2007). Empresas gacela y empresas tortuga en Aragón. Working Paper, 37. Fundación Economía Aragonesa.

Glancey, K. (1998). Determinants of growth and profitability in small entrepreneurial firms. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behaviour & Research, 4(1), 18–27.

Henreksson, M., & Johansson, D. (2010). Gazelles as job creators: a survey and interpretation of the evidence. Small Business Economics, 35, 227–244. doi:10.1007/s11187-009-9172-z.

Hernández, J.M., Amat, O., Fontrodona, J., & Fontana, I. (1999). Les empreses gasela a Catalunya. Papers d’Economia Industrial, 12. Generalitat de Catalunya.

Hoffman, A. N., & Junge, M. (2006). Documenting data on high-growth firms and entrepreneurs across 17 countries. Copenhagen: FORA-The Danish Enterprise and Construction Authority’s Division for Research and Analysis.

Hölzl, W., & Friesenbichler, K. (2010). High-growth firms, innovation and the distance to the frontier. Economics Bulletin, 30(2), 1016–1024.

Hoogstra, G. J., & van Dijk, J. (2004). Explaining firm employment growth: does location matter? Small Business Economics, 22, 179–192. doi:10.1023/b:sbej.0000022218.66156.ac.

Kirchhoff, B. A. (1994). Entrepreneurship and dynamic capitalism. Westport: Praeger.

Kolar, J. (2014). Policies to support high growth innovative enterprises. 2014 ERAC Mutual - learning seminar on research and innovation policies. Brussels: European Commission.

Levratto, N., Tessier, L., & Zoukiri, M. (2010). The determinants of growth for SMES. A longitudinal study from French manufacturing firm. Working Paper, 28. CNRS-Economix, Université de Paris Ouest Nanterre La Défense.

López-García, P., & Puente, S. (2012). What makes a high-growth firm? A dynamic probit analysis using Spanish firm-level data. Small Business Economics, 39(4), 1029–1041. doi:10.1007/s11187-011-9321-z.

Molina-Morales, F. X., García-Villaverde, P. M., & Parra-Requena, G. (2014). Geographical and cognitive proximity effects on innovation performance in SMEs: a way through knowledge acquisition. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 10, 231–251.

Moreno, A. M., & Casillas, J. C. (2007). High growth SMEs versus non-high-growth SMEs: a discriminant analysis. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development, 19(1), 69–88. doi:10.1080/08985620601002162.

OECD. (2007). Eurostat-OECD Manual on business demography statistics. Paris: European Commission-OECD.

OECD. (2009). Measuring entrepreneurship: A collection of indicators (2009th ed.). Paris: OECD-Eurostat Entrepreneurship Indicators Programme.

Porter, M. E. (1990). The competitive advantage of nations. London: Macmillan.

Porter, M. E. (1998). Clusters and the new economics of competition. Harvard Business Review, 77–90.

Rosenthal, S. S., & Strange, W. C. (2004). Evidence on the nature and sources of agglomeration economies. In J. V. Henderson & J. F. Thisse (Eds.), Handbook of urban and regional economics (Vol. 4, pp. 2119–2172). Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Russo, M. (2002). Innovation Processes in Industrial Districts. Venezia: ISCOM Project.

Sanchís, J. A., Millán, J. M., Baptista, R., Burke, A., Parker, S. C., & Thurik, A. R. (2015). Good times, bad times: entrepreneurship and the business cycle. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 11(2), 243–251.

Santa María, M. J., Fuster, A., & Giner, J. M. (2012). Identification of technological districts: the case of Spain. Sviluppo Locale, 39, 45–74.

Schreyer, P. (2000). High-growth firms and employment, OECD Science. Technology and Industry Working Papers, 3. Paris: OECD.

Segarra, A., & Teruel, M. (2014). High-growth firms and innovation: an empirical analysis for Spanish firms. Small Business Economics, 43(4), 805–821. doi:10.1007/s11187-014-9563-7.

Sforzi, F. (1992). Importancia cuantitativa de los distritos industriales marshallianos en la economía italiana. In F. Pyke, G. Becattini, & W. Sengenberger (Eds.), Los distritos industriales y las pequeñas empresas I. Distritos industriales y cooperación interempresarial en Italia (pp. 111–145). Madrid: Ministerio de Trabajo y Seguridad Social.

Stam, E. (2005). The geography of gazelles in The Netherlands. Tijdschrift voor Economische en Sociale Geografie, 96(1), 121–127. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9663.2005.00443.x.

St-Jean, E., Julien, P. A., & Audet, J. (2008). Factors associated with growth changes in ‘gazelles’. Journal of Enterprising Culture, 16, 161–188. doi:10.1142/S0218495808000089.

Storey, D. J. (1994). Understanding the small business sector. London: Routledge.

Storey, D. J. (1999). The ten percenters. Fast growing SMEs in Great Britain (Fourth report). London: Deloitte & Touche International.

Vaessen, P., & Keeble, D. (1995). Growth-oriented SMEs in unfavourable regional environments. Regional Studies, 29(6), 489–505. doi:10.1080/00343409512331349133.

Wiklund, J. (1998). Small firm growth and performance: Entrepreneurship and beyond. JIBS Dissertation Series, 3. Jönköping International Business School.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank two anonymous reviewers for their valuable and helpful comments. The usual disclaimer applies.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Giner, J.M., Santa-María, M.J. & Fuster, A. High-growth firms: does location matter?. Int Entrep Manag J 13, 75–96 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-016-0392-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-016-0392-9