Abstract

Extensive use of engineered nanoparticles has led to their eventual release in the environment. The present work aims to study the removal of Polyvinylpyrrolidone-coated silver nanoparticles (PVP-Ag-NPs) using Aspergillus niger and depict the role of exopolysaccharides in the removal process. Our results show that the majority of PVP-Ag-NPs were attached to fungal pellets. About 74% and 88% of the PVP-Ag-NPs were removed when incubated with A. niger pellets and exopolysaccharide-induced A. niger pellets, respectively. Ionized Ag decreased by 553 and 1290-fold under the same conditions as compared to stock PVP-Ag-NP. PVP-Ag-PVP resulted in an increase in reactive oxygen species (ROS) in 24 h. Results show an increase in PVP-Ag-NPs size from 28.4 to 115.9 nm for A. niger pellets and 160.3 nm after removal by stress-induced A. niger pellets and further increased to 650.1 nm for in vitro EPS removal. The obtained findings show that EPS can be used for nanoparticle removal, by increasing the net size of nanoparticles in aqueous media. This will, in turn, facilitate its removal through conventional filtration techniques commonly used at wastewater treatment plants.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Engineered nanoparticles (ENPs) are produced in different shapes and forms. ENPs are widely used in gene therapy, drug delivery, agriculture, industry, cosmetics, bioremediation, imaging, and diagnostics (Missaoui et al. 2018). In particular, silver nanoparticles (Ag-NPs) are considered one of the most produced nanoparticles due to their diverse applications. ENPs are used as an anticancer agent (Almalki and Khalifa 2020), anti-inflammatory and antioxidant (Alkhalaf et al. 2020). They are used for dye degradation (Kazancioglu et al. 2021), removal of anthropogenic pollutants from water (Sherin et al. 2020), for treatment of wastewater (Qu et al. 2013), in biosensors (Tran et al. 2020), signal amplification (Hou et al. 2020), and in detection of SARS-COV2, treatment of COVID-19 and in preparation of SARS-COV vaccines (Duan et al. 2021). According to EPA fact sheet nanomaterials (EPA 2017), 1800 consumer nanomaterial products have reached the market since 2014.

Unfortunately, the enormous development in nanomaterial fabrication and applications has prompted questions about their long-term accumulation in the environment and human surroundings (Radziun et al. 2011; Kik et al. 2020). Accidental release into soil and sewer systems was reported to affect the viability of soil microflora and activated sludge bacteria which eventually affect their performance (Gomaa 2014). ENPs can easily reach water and drinking facilities (Lawler et al. 2013), resulting in acute toxicity and bioaccumulation of Ag-NPs aquatic organisms (Lacave et al. 2017). They reside, eventually, in aquatic sediments leading to their predominance as an environmental exposure path to plants and animals posing risks to human health via the food chain (Zhao et al. 2021). Different toxicity studies were conducted to evaluate the extent of damage exerted by ENPs (Marimon-Bolívar et al. 2019; Liu et al. 2019). The toxicity can take place via skin, inhalation, and ingestion and can cause oxidative stress, inflammation, DNA damage, apoptosis, and translocation inside organs and tissues leading to secondary toxicity (Missaoui et al. 2018). ENPs are coated with different organic materials for biocompatibility. Coatings such as citrate, polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) and branched polethyleneimine (BPEI) are added to provide stability and effective dispersion (Silva et al. 2014). Wang et al. (2021) reported that PVP coating reduces the size of ENPs and this makes them travel faster within soil due to the increased steric hindrance as compared to bare Ag-NPs.

ENPs, in general, have been reported to be successfully removed via coagulation, flocculation, filtration (Lawler et al. 2013), biotransformation (Marimuthu et al. 2020) and aggregation (Zhang et al. 2020). However, bioremoval, using microorganisms and their metabolites, is still considered cost-effective, efficient, and environmentally friendly as compared to other chemical and physical treatments (Khan et al. 2012; Oh et al. 2015). The interaction between microbes and metals can take place via metabolism-dependent or independent pathways, rendering the metals less toxic or less available to prevent their leaching in the environment magnifying the problem (Gupta and Diwan 2017). By analogy, ENPs removal is approached in a way that resembles heavy metal removal.

The interaction between ENPs and biological material is controlled by different parameters; one of the most critical parameters controlling this nano-bio interaction was reported to be surface charge (Silva et al. 2014). The surface charges are the result of the presence of different functional groups in a biological material. Fungi are known to remove heavy metals and other pollutants through interaction between metal cations and fungal cell wall functional groups such as carboxylic, hydroxyl, amine, sulfate and phosphate groups through complexation, ion exchange, or through physical adsorption (Viraraghavan and Srinivasan 2011; Qin et al. 2020). Fungi can also produce exopolysaccharides (EPS) in the presence of heavy metals as a result of stress. This stress response produced EPS can help in the exclusion of heavy metals from the media and can be used in heavy metal removal strategies (Mohite et al. 2017). Fungal EPS are macromolecular structures with unique conformations, interesting properties for industrial, medical, and environmental applications. Its production is highly dependent on the media composition and physical growth conditions (Mahapatra and Banerjee 2013). EPS can be produced and remain bound to the surface or released in the media, while the latter can be collected, purified, the former provides an additional layer to fungi, thus providing a larger surface area for metal or ENPs adsorption. From this standpoint, the present work aims to provide insight on PVP-Ag-NPs removal from aqueous media using Aspergillus niger and to depict the role of exopolysaccharides in the bioremoval process.

Materials and methods

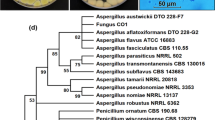

Fungi and growth under exopolysaccharide producing conditions

Aspergillus niger isolated and characterized in previous work (Gomaa et al. 2013). A proper dilution of A. niger spore suspension was used to inoculate exopolysaccharide (EPS) producing media in g/l: Glucose 60, Peptone 20, MgSO4. 7H2O 2, KH2PO4 2, FeSO4.7H2O 0.05, pH 5.8 (Li et al. 2012), CaCl2 1 M was added to the cultivation media on the day of inoculation to induce stress (Gomaa et al. 2013). Different glucose concentrations were used (0, 15, 30, 60, and 120 g/l). The flasks were incubated for 4 days at 30 °C and 150 rpm. At the end of incubation, fungal pellets were separated from media using Mira cloth filtration, fungal pellets were weighed after removing excess liquid. The extracellular fluid for each flask was aliquoted in a sterile 50 ml falcon tube, 2 volumes of 95% ethanol were added to each sample and were left for 48 h at 4 °C on a shaker. Samples were centrifuged at 1780 g for 15 min using Thermo Scientific SORVALL LEGENT TR + centrifuge. The supernatant was discarded and the pellets formed were used for EPS analysis. EPS was measured as total carbohydrates using phenol sulfuric method described in Biovision total carbohydrate colorimetric kit user instructions. The absorbance was read at 490 nm using SpectraMax M3, MultiMode Microplate reader, Molecular Devices, San Jose, CA, USA. For blank samples, water was used instead of sample. Concentrations were calculated from a standard curve, glucose was used as the standard. Concavalin A conjugate (Invitrogen detection technologies) molecular probe was used to label free and mycelial bound EPS. Fluorescence was detected at 555/580 nm using SpectraMax M3, MultiMode Microplate reader, Molecular Devices, San Jose, CA, USA. Images of EPS containing A. niger were captured using Leica model TCS SP5; Leica Microsystems CMS GmbH, Mannheim, Germany.

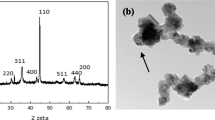

Engineered nanoparticles (ENPs) under study

ENP in this study was Ag-Polyvinylpyrrolidone (Ag-PVP) Biopure nanospherical particles were purchased from nanocomposix (San Diego, CA, USA), 99.99% silver purity, Zeta potential -32 mV, diameter (TEM) 20.5 ± 3.6 nm. Stock suspensions were prepared using deionized water and sonicated for 30 s at 50 W prior to each experiment to ensure uniform particle distribution.

A. niger growth and reactive oxygen species (ROS) in the presence of PVP-Ag-NPs

PVP-Ag-NPs were added to 24-h-old A. niger pellets in 100 ml Erlenmeyer flasks in the following final concentrations: 0, 25, 50, and 100 ppm. The flasks were incubated for 24 h at 30 °C in a rotatory shaker at 150 rpm. Fungal weight was performed as described above. Reactive oxygen species detection was performed according to Kenne et al. (2018). Equal weights (0.5 g) of fungal pellets of each flask was transferred into 9 well plate. 2’,7’-Dichlorofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA) was used to quantify ROS. For each well, 1 µm DCFD-A was added to 1 ml Phosphate Buffer Saline (PBS), mixed well, and left to incubate at room temperature for 4 h in dark. Five hundred µl taken from each well was transferred to microfuge for a quick spin, 100 µl was transferred to 96 well plate. Readings were recorded at 490/525 nm using SpectraMax M3, MultiMode Microplate reader, Molecular Devices, San Jose, CA, USA.

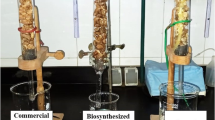

PVP-Ag-NPs removal by A. niger experiments

To depict the mechanism of PVP-Ag-NPs bioremoval, 24-h-old A. niger pellets (1 g), A. niger culture media containing EPS (10 ml) and EPS-induced A niger pellets (1 g), were each placed in a separate flask, 50 ppm PVP-Ag-NPs was added and cultures incubated at 150 rpm, 30 °C for 24 h. PVP-Ag-NPs concentration and size were assayed as mentioned below. A schematic representation of the experiment is shown in Fig. S1.

PVP-Ag-NPs UV–Vis spectrum, concentration and size

To follow up the bioremoval of PVP-Ag-NPs from the media, Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) was used. A dual-beam UV absorbance spectrometer (UV–vis) (Shimadzu UV-2600 spectrophotometer, Co., Kyoto, Japan) at a resolution of 1 nm from 200 − 800 nm wavelength range at room temperature. Quartz glass cuvettes with an optical path length of 10 mm, requiring. Ultrahigh purity water was used as the reference sample to take the blank spectrum for all measurements. Dynamic light scattering (DLS) was used to determine the particle size distribution (z-average) of the PVP-Ag-NPs suspensions, A. niger, EPS-induced A. niger and in vitro EPS using a Zetasizer (Nano-ZS, Malvern Instruments Ltd., MA, USA). Inductively coupled plasma-atomic mass spectroscopy (ICP-MS) was used to measure Ag ENPs concentration. The samples were acidified in 68–70% nitric acid (HNO3), trace metal grade (Fisher Scientific, MA, USA), and then diluted 100-fold in 1% of HNO3, this was used for analysis using ICP-MS (NexIONTM 350 D, PerkinElmer Inc., Waltham, MA, USA).

Bioremoval and adsorptive capacity

To determine the bioremoval and adsorptive capacity of A. niger, EPS-induced A. niger, and in vitro (free) EPS. Initial and residual PVP-Ag-NPs concentrations were measured as previously described. The removal was calculated by the following equation:

where Ci and Cf are the initial and final lead concentrations, respectively.

While the adsorptive capacity was calculated by the following equation:

where Ci is the initial concentration, Cf is the final concentration, W is the weight of the immobilized fungal mycelia (adsorbent) in gm, V is the volume of the sample. All the data presented are the mean value of three readings ± SE.

Results

Exopolysaccharide production using Aspergillus niger

The increase of glucose concentration to A. niger growth media has led to an increase in both released and surface-bound EPS production. Figure 1a shows that EPS released in the media increased from 12.05 to 34.2 mg/ml as concentrations increased from 0 to 120 g/l, respectively; on the other hand, surface-bound glucose increased from 10.8 to 46.07 mg/ml, respectively. Despite the increase in EPS production, yet the fungal growth reached its peak weight of 18.3 g/100 ml at 60 g/l glucose concentration, but dropped to 14 g/100 ml at 120 g/l. For the upcoming experiments, 60 g/l glucose was used for media preparation. To increase EPS production, calcium chloride was added to the media on the day of inoculation. Figure 1b shows that EPS released in the media increased from 16.6 to 19.7 mg/ml in the absence and presence of calcium chloride, respectively, while surface-bound EPS increased from 25.7 to 34.3 mg/ml in the absence and presence of calcium chloride, respectively. On the other hand, the presence or absence of calcium chloride did not affect fungal growth. Figure 1c represents the appearance of EPS as fluorescent spots in A. niger grown in the absence and calcium chloride-containing media.

a Effect of increasing glucose concentration on surface bound EPS, released EPS and fungal weight after incubation at 30 °C at 150 rpm for 4 days. b Released and surface bound EPS production and fungal growth in presence and absence of calcium chloride. c Images of A. niger grown in the presence (B) and absence of calcium chloride (A). Images captured using fluorescent microscope, concavalin A was used to stain EPS

Aspergillus niger stress response to Ag-PVP nanoparticles

The exposure of A. niger to PVP-Ag-NPs has resulted in an increase in reactive oxygen species (ROS) of about 4.41-fold in intensity. The increase was directly proportional to the concentration of nanoparticles present in the media (Fig. 2). Although the fungus showed ROS upon exposure to the used nanoparticles, yet the fungal growth was not compromised.

PVP-Ag-NP removal by Aspergillus niger pellet and growth media

A. niger pellets removed about 74% of PVP-Ag-NPs, while 26% was removed by A. niger growth media (Fig. 3a). The UV–Vis spectrum reveals the disappearance of the Ag distinct peak at 392–400 nm, the overall absorbance increased which reflects the presence of organic macromolecules (Fig. 3b).

PVP-Ag-NPs bioremoval using Aspergillus niger

Figure 4a shows that the removal of PVP-Ag-NP increased after adding EPS-induced A. niger pellets. The ionized Ag decreased 552 and 1290-fold after removal using A. niger pellets and EPS-induced A. niger pellets, respectively. Figure 4b shows the UV–Vis spectrum before and after ENPs removal, the peak at 400 nm distinct for Ag disappeared after using A. niger pellets and the overall absorbance increased.

Table 1 represents the change in sizes for the different Ag-PVP-NPs samples. The results show that PVP-Ag-NP sizes increased from 28.8 to 115.9 nm after incubation with A. niger pellets, 160.3 nm after incubation with EPS-induced A. niger pellets, and 650.1 nm when A. niger growth media containing 100 mg/ml EPS was used for bioremoval. The adsorptive capacity of the different samples increased from 1.28 to 2.85 mg/g and further increased to 3.45 mg/g when EPS (100 mg/ml) from media was used.

Discussion

Exopolysaccharides are omnipresent biomolecules that have functional groups and can adsorb different pollutants (Banerjee et al. 2021). Both media composition and physical conditions play an integral role in the production and composition of EPS by fungi (Mahapatra and Banerjee 2013). While it is commonly reported that glucose, peptone, and magnesium sulfate are the key elements in EPS production by fungi (Li et al. 2012, Sharmila et al. 2017), yet stress was also reported to induce EPS production as means of protection (Mohite et al. 2017). In previous work, calcium chloride was reported to induce stress in A. niger (Gomaa et al. 2013). Calcium chloride was also reported to be among the media components inducing EPS production in fungi (Mahapatra and Banarjee 2013). The increase in fluorescence spots in A. niger grown in calcium chloride supplemented cultures reflects the increase in EPS production confirming that calcium chloride can induce EPS in the present study. The fluorescent spots reflected the intensity of the mannose and glucose binding conjugate dye Concavalin A used to tag EPS.

EPS produced from bacterial, algal, and fungal origin are recommended as surface-active agents for heavy metal removal via adsorption of heavy metal cations onto the negative charge of EPS functional groups, this process is metabolism-independent (Rasulov et al. 2013). PVP-Ag-NPs have a net surface charge of -32 mV (according to the manufacturer’s certificate of analysis), this suggests that removal of the ENPs will not depend on physicochemical adsorption since EPS also has a net negative charge. EPS is polyanionic due to the different functional groups comprising its backbone (Banerjee et al. 2021). However, in the presence of PVP-Ag-NPs, ROS was found to increase upon the increase in NPs concentration in the media. On the other hand, fungal growth was not affected by the presence of PVP-Ag-NPs. This result is an indication that sublethal doses of nanoparticles are still a threat and can cause stress to living cells. PVP coating of nanoparticles is used to avoid agglomeration, decrease particle size and ensure uniform dispersion (Gharibshahi et al. 2017). Silva et al. (2014) reported that the difference in net surface charge between the nano-bio interface can be the cause behind toxicity. This places PVP-coated ENPS at the lower end of the toxicity spectrum (as compared to the other tested organo-coatings) since both EPS and PVP-Ag-NPs have net negative charges. Although this explains the viability of A. niger after the addition of PVP-Ag-NPs, yet it doesn’t mean that they present no toxicity. The obtained results show ROS as a stress response to PVP-Ag-NPs. Moreover, ROS production was reported to cause the removal of PVP coat from PVP-Ag-NPs (Zhang et al. 2020), thus exposing Ag divalent cation. This, in turn, can result in adsorption of Ag++ to the negatively charged EPS or negatively charged fungal cell wall (Gupta and Diwan 2017). This renders ROS production a mechanism for PVP removal, Ago would undergo oxidative dissolution to Ag++, which in turn facilitates biotransformation via chlorination, oxidation or sulfidation to produce AgCl, Ag2O, and Ag2S; this reduces its toxicity and is considered another path toward nanotoxicity mitigation (Marimuthu et al 2020).

From our perspective, both fungi and their produced EPS represent a low-cost, highly efficient adsorbing material that can remove PVP-Ag-NPs from aqueous media. The macromolecular structure and net negative charge of both fungi (Viraraghavan and Srinisivan 2011) and EPS provide a suitable matrix for entrapment of pollutants and thus, it is used as flocculants (Sharmila et al. 2014) in addition to its use as a bioadsorbent for heavy metals (Gupta and Diwan 2017). In the present study, EPS-induced A. niger pellets removed the majority of PVP-Ag-NPs from aqueous media as opposed to a smaller fraction when using EPS-containing media.

It was noted that the UV–Visible spectrum in our study showed that the broadness and intensity of PVP-Ag-NPs peaks increased after its incubation with EPS in its fungal bound form, stress induced form and free form. Changes in size and concentration of nanoparticles can be detected using UV–Visible spectroscopy (Haiss et al. 2007). Baset et al. (2011) reported that the width of the UV–Visible profile has been related to NP size, while the intensity of absorption spectra is related to the dielectric constant and interband transition of metal nanoparticles. The present study also shows that PVP-Ag-NPs size has increased after removal by A. niger, EPS-induced A. niger, media, and in vitro EPS. The diameter of particles contributes to the aggregation and flocculation of Ag-NPs (Oh et al. 2015; Zhang et al. 2020). The increase in size suggests that bioremoval took place and is relevant to the adsorptive capacity of the used adsorbent in the present study. The obtained results suggest also that in vitro EPS can be used for NP removal and this will be our focus in the future.

Based on the current findings, it can be confirmed that A. niger is responsible for the majority of PVP-Ag-NPs removal. It can be depicted that the removal takes place via one of the three following mechanisms; (1) EPS bound to A. niger pellets is responsible for removal, by providing more surface area for entrapment, (2) EPS can be induced by exposing A. niger to stress, this increases EPS production and therefore increases the entrapment, and (3) increasing the size of PVP-Ag-NPs, through coating by free EPS or binding to it, or through aggregation (Fig. 5).

Conclusion

The study concludes that A. niger can efficiently remove PVP-Ag-NPs from aqueous media. The bioremoval process can take place via different mechanisms with EPS playing an integral role. The results depict that the possible mechanisms involved for the removal is based on entrapment within the EPS in its free or fungal bound forms. This entrapment coats the ENPs, increasing its size, and therefore, making it practical to remove using filtration as a preliminary step in wastewater treatment plants. EPS is easily produced and can be used in partially purified form; it can be combined with other biomaterials to provide an efficient biofilter with enhanced mechanical properties. Moreover, it is biodegradable and therefore, is considered ecofriendly and cheap.

Data availability

Data will be shared upon request.

References

Alkhalaf MI, Hussein RH, Hamza A (2020) Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles by Nigella sativa extract alleviates diabetic neuropathy through anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects. Saudi J Biol Sci 27(9):2410–2419. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sjbs.2020.05.005

Almalki MA, Khalifa AYZ (2020) Silver nanoparticles synthesis from Bacillus sp KFU36 and its anticancer effect in breast cancer MCF-7 cells via induction of apoptotic mechanism. J Photochem Photobiol B 204:111786

Banerjee A, Sarkar S, Govil T, Gonzalez-Faune P, Cabrera-Barjas G, Bandopadhyay R, Salem D, Sani R (2021) Extremophilic exopolysaccharides: biotechnologies and wastewater remediation. Front Microbiol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2021.721365

Baset S, AkbariH ZH, Shafie M (2011) Size measurement of metal and semiconductor nanoparticles via UV-Vis absorption spectra. Digest J Nanomaterials and Biostructures 6:709–716

Duan Y, Wang S, Zhang Q, Gao W, Zhang L (2021) Nanoparticle approaches against SARS-CoV-2 infection, Current Opinion in Solid State and Materials Sci 25:100964

Environmental Protection Agency Fact Sheet (2017) https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2014 03/documents/ffrrofactsheet_emergingcontaminant_nanomaterials_jan2014_final.pdf

Gharibshahi L, Saion E, Gharibshahi E, Shaari AH, Matori KA (2017) Influence of poly(vinylpyrrolidone) concentration on properties of silver nanoparticles manufactured by modified thermal treatment method. PLoS ONE 12(10):e0186094. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0186094

Gomaa OM (2014) Removal of silver nanoparticles using live and heat shock Aspergillus niger cultures. World J Microbiol Biotechnol 30(6):1747–1754

Gomaa OM, Selim NS, Linz JE (2013) Biochemical and biophysical response to calcium chloride stress in Aspergillus niger and its role in malachite green degradation. Cell Biochem Biophys 65:413–423

Gupta P, Diwan B (2017) Bacterial exopolysaccharide mediated heavy metal removal: a review on biosynthesis, mechanism and remediation strategies. Biotechnol Rep (amst) 23(13):58–71

Haiss W, Thanh N, Aveyard J, Fernig D (2007) Determination of size and concentration of gold nanoparticles from UV-Vis spectra. Anal Chem 79:4215–4221

Hou L, Huang Y, Hou W, Yan Y, Liu J, Xia N (2020) Modification-free amperometric biosensor for the detection of wild-type p53 protein based on the in situ formation of silver nanoparticle networks for signal amplification. Int J Biol Macromol 5(158):580–586

Kazancioglu EO,Aydin M, Arsu N (2021) Photochemical synthesis of bimetallic gold/silver nanoparticles in polymer matrix with tunable absorption properties: superior photocatalytic activity for degradation of methylene blue, Materials Chemistry and Physics 269:124734

Kenne G, Gummadidala P, Omebeyinje M, Mondal AK, Bett D, McFadden S, Bromfield S, Banaszek N, Velez-Martinez M, Mitra C, Mikell I, Chatterjee S, Wee J, Chanda A. (2018) Activation of aflatoxin biosynthesis alleviates total ROS in Aspergillus parasiticus MDPI toxins 10:57; doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins10020057

Khan SS, Mukherjee A, Chandrasekaran N (2012) Adsorptive removal of silver nanoparticles (SNPs) from aqueous solution by Aeromonas punctata and its adsorption isotherm and kinetics. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces 1(92):156–160

Kik K, Bukowska B, Sicińska P (2020) Polystyrene nanoparticles: sources, occurrence in the environment, distribution in tissues, accumulation and toxicity to various organisms. Environ Pollut 262:114297

Lacave JM, Fanjul Á, Bilbao E, Gutierrez N, Barrio I, Arostegui I, Cajaraville MP, Orbea A (2017) Acute toxicity, bioaccumulation and effects of dietary transfer of silver from brine shrimp exposed to PVP/PEI-coated silver nanoparticles to zebrafish. Comp Biochem Physiol C Toxicol Pharmacol 199:69–80

Lawler DF, Mikelonis AM, Kim I, Lau BL, Youn S (2013) Silver nanoparticle removal from drinking water: flocculation/sedimentation or filtration? Water Sci & Technol: Water Supply 13:1181–1187

Li P, Xu L, Mou Y, et al. (2012) Medium optimization for exopolysaccharide production in liquid culture of endophytic fungus Berkleasmium sp. Dzf12. Int J Mol Sci 13(9):11411–11426

Liu CH, Chiu HC, Sung HL, Yeh JY, Wu KC, Liu SH (2019) Acute oral toxicity and repeated dose 28-day oral toxicity studies of MIL-101 nanoparticles. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yrtph.2019.104426

Mahapatra S, Banerjee D (2013) Fungal exopolysaccharide: production, composition and applications. Microbiol Insights 29(6):1–16

Marimon-Bolívar W, Tejeda-Benítez L, Núñez-Avilés C, Léon-Péreza D (2019) Evaluation of the in vivo toxicity of green magnetic nanoparticles using Caenorhabditis elegans as a biological model. Environ. Nanotechnol. Monitoring & Manag 12: 100253

Marimuthu S, Antonisamy AJ, Malayandi S, Rajendran K, Tsai PC, Pugazhendhi A, Ponnusamy VK (2020) Silver nanoparticles in dye effluent treatment: a review on synthesis, treatment methods, mechanisms, photocatalytic degradation, toxic effects and mitigation of toxicity. J Photochem Photobiol B: Biol 205:111823

Missaoui WN, Arnold RD, Cummings BS (2018) Toxicological status of nanoparticles: what we know and what we don’t know. Chem Biol Interac 1(295):1–12

Mohite BV, Koli SH, Narkhede CP, Patil SN, Patil SV (2017) Prospective of microbial exopolysaccharide for heavy metal exclusion. Appl Biochem Biotechnol 183:582–600

Oh S, Sung H, Park C, Kim Y (2015) Biosorptive removal of bare-, citrate-, and PVP-coated silver nanoparticles from aqueous solution by activated sludge. J Industrial Eng Chem 25:51–55

Qin H, Hu T, Zhai Y, Lu N, Aliyeva J (2020) The improved methods of heavy metals removal by biosorbents: a review. Environ 258:113777

Qu X, Alvarez PJ, Li Q (2013) Applications of nanotechnology in water and wastewater treatment. Water Res. 1;47(12):3931–46

Radziun E, Dudkiewicz Wilczyńska J, Książek I, Nowak K, Anuszewska EL, Kunicki A, Olszyna A, Ząbkowski T (2011) Assessment of the cytotoxicity of aluminium oxide nanoparticles on selected mammalian cells. Toxicol in Vitro 25(8):1694–1700

Rasulov B, Yili A, Aisa H (2013) Biosorption of metal ions by exopolysaccharide produced by Azotobacter chroococcum XU1. J Environ Protection 4:989–993

Sharmila K, Thillaimaharani KA, Durairaj R, Kalaiselvam M (2014) Production and characterization of exopolysaccharides (EPS) from mangrove filamentous fungus Syncephalastrum Sp. African J Microbiol Res 8:2155–2161

Sherin L, Sohail A, Amjad U, Mustafa M, Jabeend R, Ul-Hamide A (2020) Facile green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Terminalia bellerica kernel extract for catalytic reduction of anthropogenic water pollutants. Colloid and Interface Sci Comm 37: 100276

Silva T, Pokhrel L, Dubey B, Tolaymat T, Maier K, Liu X (2014) Particle size, surface charge and concentration dependent ecotoxicity of three organo-coated silver nanoparticles: comparison between general linear model-predicted and observed toxicity Sci Total Environ 468–469: 968–976

Tran H, Nguyen N, Tran C, Tran L, Le T, Tran H, Piro B, Huynh C, Nguyen T, Nguyen N, Hue Dang T, Nguyen H, Tran L, Phan N (2020) Silver Nanoparticles-Decorated Reduced Graphene Oxide: a Novel Peroxidase-like Activity Nanomaterial for Development of a Colorimetric Glucose Biosensor Arabian J Chem 13:6084–6091

Viraraghavan T, Srinivasan A. (2011) Fungal biosorption and biosorbents. Microbial biosorption of metals. Springer. p. 143–158

Wang K, Zhang Y, Sun B, Yang Y, Xiao B, Zhu L (2021) New insights into the enhanced transport of uncoated and polyvinylpyrrolidone-coated silver nanoparticles in saturated porous media by dissolved black carbons. Chemosphere 283:131159

Zhang ZG, Wu QT, Shang E, Wang X, Wang K, Zhao J, Duan J, Liu Y, Li Y (2020) Aggregation kinetics and mechanisms of silver nanoparticles in simulated pollution water under UV light irradiation. Water Environ Res 92(6):840–849

Zhao J, Wang X, Hoang SA, Bolan NS, Kirkham MB, Liu J, Xia X, Li Y (2021) Silver nanoparticles in aquatic sediments: occurrence, chemical transformations, toxicity, and analytical methods. J Haz Mat 418: 126368

Funding

This work was part of Fulbright 2018/2019 fellowship awarded to Ola M. Gomaa to Department of Health Sciences, Arnold School of Public Health, University of South Carolina, SC, USA.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Ola Gomaa contributed with the idea, plan of work, experimental, writing the manuscript, and editing the final version.

Amar Yasser Jassim contributed through experimental work of sample preparation and ICP-MS measurements, size characterization using DLS, and Anindya Chanda contributed through technical support and fruitful discussion.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable. No use of human or animal samples or tissues.

Consent for publication

All authors agree to the content of this manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Additional information

Responsible Editor: Diane Purchase

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gomaa, O.M., Jassim, A.Y. & Chanda, A. Bioremoval of PVP-coated silver nanoparticles using Aspergillus niger: the role of exopolysaccharides. Environ Sci Pollut Res 29, 31501–31510 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-021-18018-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-021-18018-9