Abstract

Food waste has influenced food security for poor people, food safety, economic development, and the environment. The objective of this paper is to examine the food waste reduction behavior in a sample of Iran households. The study used the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) as its conceptual framework and further attempted to extend the TPB by incorporating the addition of new variables (e.g., marketing addiction, the perceived ascription of responsibility, moral attitude, waste-preventing behavior, and socio-demographic characteristics). Data was gathered using a systematic random sampling technique and analyzed with structural equation modeling (SEM). The sample size used in the study was 382. The results revealed that TPB and Extended Theory of Planned Behavior (ETPB) models exhibited a reasonable fit to the data. If key goals are to predict intention to reduce food waste (IRFW), the TPB is preferable due to a smaller quantity of comparison criteria. However, if the key goal is to explain IRFW, the ETPB is preferable due to higher R2 compared with others. Besides, the variable “waste-preventing behavior” was the most significant variables influencing the intention to reduce food waste. Socio-demographic characteristics such as age, level of education, and income were found to be statistically significant predictors of intention. Finally, the implication for management and the scope for future research have been discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The global issue of food waste

On a global scale, one-third of produced food for human consumption is converted to waste. Its amount is about 1.3 billion tons per year (Gustavsson et al. 2011; Lipinski et al. 2013). According to the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) (Zaki n.d.), about 50 million metric tons of food produced is lost in the oriental sub-region of the Middle East. Iran is responsible for 2.7%, equivalent to around 35 million tons of the total. The waste mostly includes bread, fruit, vegetables, and rice ((FAO) 2013). The distribution of food waste differs among nations and individuals. For instance, the developed countries in Europe and North America have higher food waste compared with developing countries in Sub-Saharan Africa (Papargyropoulou et al. 2014). In Iran, similar to other medium- and high-income countries, food is wasted to a significant extent during the consumption stage of the food supply chain (Nakouzi 2017).

Food waste has influenced on food security for poor people, food safety, economic development, and environment (Buchner et al. 2012; Geislar 2019). From a moral point of view, such a large amount of food waste when more than 800 million people around the world are suffering from hunger or malnutrition should affect us to change our collective and individual behavior which has afflicted to a large part of the world’s population (Hossain 2017; Silva 2016). Besides, the economic avoidable food losses have a direct and negative impact on the farmer and consumer incomes. The cost of food waste and waste production on both sides of the food supply chain can be very significant. From the environmental aspect, it is obvious that a large number of resources are used to produce unwanted food. The process of producing these waste products emits greenhouse gases that can be avoided (Scherhaufer et al. 2018; Tonini et al. 2018). Food is wasted at different parts of the food chain, from harvesting, transportation, processing, to consumption in private households (Wahlen and Winkel 2017). The last one has the most contribution and needs a complex set of management behaviors (BIOIS 2010). A superior comprehension of these behaviors can be utilized to help improve the proficiency of household food management and decline food waste generation.

The theoretical background of the study

Recently, the studies on the factors affecting food waste generation at the customer level have been considered and are still under discussion (Abdelradi 2018; Mondéjar-Jiménez et al. 2016; Quested et al. 2013). Previous research has shown that there are many reasons and multiple behaviors that lead to food waste and suggests it as a complex behavior. Therefore, finding the proper conceptual framework that can explain this behavior is necessary. In this regard, some works proposed a model based on the TPB for analyzing food waste behavior. For example, van der Werf et al. (2019) suggested a TPB model for exploring food waste behavior in London, Canada, based on following constructs: attitudes, perceived behavioral control, subjective norms, personal norms, good provider identity, intentions, and household planning habits. Furthermore, Mondéjar-Jiménez et al. (2016) explored food waste behavior of Spanish and Italian youths within the framework of the TPB by considering these constructs: concern about food waste, moral attitude, subjective norms, perceived behavior control, marketing/sale addiction, intention, and positive behavior. In addition, Stefan et al. (2013) explored the effect of consumers’ food waste behavior among Romanian peoples with its possible drivers including moral attitudes, lack of concern, subjective norms, perceived behavioral control, shopping routines, planning routines, and intention not to waste food. Nevertheless, the use of the TPB model to investigate food waste behavior corresponds to some limitations. For example, due to the multidisciplinary nature of the food waste subject, the TPB has a moderate explanatory power for behavioral intention (Karim Ghani et al. 2013; Stefan et al. 2013; van der Werf et al. 2019). Thus, in order to obtain a better understanding of food waste behavior, Abdelradi (2018) developed a conceptual framework for the analysis of the consumers’ behavior regarding food waste in Egypt. The constructs, including waste reuse, waste recycling, waste minimization, food choice, food expenditures, personality, religion, knowledge, and materialistic values, were tested. He concluded that the above-mentioned parameters had a significant effect on food waste behavior and need to be incorporated into the TPB in future studies. Anyway, to better understand the food waste intention and behavior, considerable researches covering more factors are still required.

This study focuses on citizens from different regions in the metropolitan of Mashhad. It is the second most populated city in Iran, with a population size of 3 million people in 2016. By use of SEM for analyzing waste behavior, this paper has twofold goals: first, TPB is proved to be able to explain the individual’s pro-environmental behavior. Therefore, it is necessary to determine whether its main variables (attitude, subjective norm, perceived behavior control, intention) and the addition of the new variables (marketing addiction, perceived ascription of responsibility, moral attitude, and waste-preventing behavior) have any influence on the intention to reduce food waste at the consumer level. As mentioned before, food waste is those of high-quantity waste in the Middle East countries. There are few kinds of literature assessing the determinants for such a high share of food waste in those countries. Hence, the second aim of this project is to answer this question: what makes the households to generate food waste more than the global average.

Research hypotheses

This study used the TPB model to explain the behavioral intention to reduce food waste in Iran. TPB model is a theory, which widely applied to explore human behaviors through a cognitive approach (Ajzen 1991; Gao et al. 2017; Halder et al. 2016; Fishbein and Ajzen 1975). In fact, this approach emphasizes the attitude and belief. TPB claims that the intention is the best predictor of behavior. In TPB, the intention is determined by three constructs including attitude, subjective norm, and perceived behavioral control. Attitude is an individual’s favorable or unfavorable assessment of the performance of a given behavior (Ajzen 1991). It seems that attitude is one of the main determinants of behavioral intention like wasting food (Graham-Rowe et al. 2014; Visschers et al. 2016). In other words, people with a more negative attitude are more negative in behavioral intention and vice versa (Taylor and Todd 1995). Subjective norms refer to an individual’s perception of social pressure or support to perform or not to perform a given behavior. People’s behavior can likely be affected by social pressure from others who are close or important to the person (Ajzen 1991). Subjective norm is a determinant of specific behavior like wasting food via intention (Graham-Rowe et al. 2014; Stefan et al. 2013). Perceived behavioral control refers to the individual’s perception of the easiness or obstacle related to performing a given behavior (Ajzen 1991). Perceived behavioral control has an influence on intention associated with a specific behavior such as reducing food waste (Graham-Rowe et al. 2014; van der Werf et al. 2019) or planning and shopping for food (Stefan et al. 2013). In addition, the current research is interested to examine the impact of additional variables and the mediating role of TPB constructs. For example, marketing strategies refer to product promotions, attractive packaging, and special offers. It means that they encourage consumers to buy excessive amounts of food, which is one of the main variables behind food waste (Lyndhurst 2007). The marketing strategies could have an influence on food waste behavior (Mondéjar-Jiménez et al. 2016). Accordingly, the research hypotheses were formed and the proposed model is presented in Fig. 1.

H1. Perceived ascription of responsibility positively related to moral attitude towards household food waste.

H2. Moral attitude had a positive influence on attitude towards household food waste.

H3. Perceived ascription of responsibility positively affects the subjective norm of reducing household food waste.

H4. Attitude towards household food waste positively influences the subjective norm.

H5. Perceived ascription of responsibility has a positive influence on perceived behavioral control over reducing household food waste.

H6. Perceived behavioral control positively affects the subjective norm of reducing household food waste.

H7. Attitude towards household food waste positively influences perceived behavioral control.

H8. Marketing addiction has a negative influence on perceived behavioral control over reducing household food waste.

H9. Perceived behavioral control positively affects household food waste preventing the behavior.

H10. Subjective norm positively affects an individual’s intention to reduce household food waste.

H11. Perceived behavior control positively affects an individual’s intention to reduce household food waste.

H12. Waste-preventing behavior has a positive influence on the intention to reduce household food waste.

H13. City region negatively affects an individual’s intention to reduce household food waste.

H14. Age of respondents positively affects an individual’s intention to reduce household food waste.

H15.Gender of respondents positively affects an individual’s intention to reduce household food waste.

Methodology

Data collection and measurement

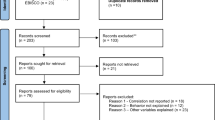

The survey was conducted in Mashhad, the second largest city in Iran, from October to December 2017. The data were collected through means of face-to-face interviews by questionnaire. Systematic random sampling technique was used to select respondents. For sampling, the urban community in Mashhad was categorized based on social stratification in the upper, middle, and lower classes. In each class, three regions were chosen as a representative area. The number of houses in each representative area was selected using the Cochran formula while their locations were determined randomly using Google Earth Software. A total of 382 questionnaires were distributed among the selected homes at nine regions. If the individual in the house had not responded, the neighbor was chosen. The response rate to the questionnaires was 100%.

A two-section questionnaire was developed based upon various literature about waste behavior (Abdelradi 2018; Karim Ghani et al. 2013; Mondéjar-Jiménez et al. 2016; Schmidt 2016). The first section illustrated items that are applied to measure the constructs of the theoretical models. According to the recommendation of Ajzen (1991), each construct had multiple items. For each item, respondents were requested to reveal the level of their agreement to the given statement on a 5-point Likert scale (1, strongly disagree; 5, strongly agree; 3, neither agree nor disagree). All the constructs along with their statements and the source of adoption are listed in Table 1. The second section was a set of items that asked the participants about socio-demographic characteristics (age, gender, educational level, income, occupation, and city region). Moreover, to check the validity and reliability of the questionnaire, a pilot test was conducted.

Data analysis

SPSS, version 22 (SPSS Inc., Chicago IL) and AMOS 24 (SmallWaters Corp., Chicago IL) were used to perform the statistical analysis of the data. Descriptive statistics, Cronbach’s alpha, Pearson correlation coefficient, and missing data were calculated by SPSS. The measure had less than 1% missing data for most of the items. Furthermore, the two-stage modeling process proposed by Bamberg (2003) was used to evaluate model fit, which is conducted in AMOS. First, the measurement models and then the structural models were examined. Maximum likelihood method was used to estimate the parameters in both steps. To evaluate the absolute fitness of the theoretical models, some indexes were used: the chi-square test (χ2), the likelihood ratio (χ2/df), the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), the Goodness-of-Fit Index (GFI), the Adjusted Goodness-of-Fit Index (AGFI), the Parsimony Goodness-of-Fit Index (PGFI), and the Incremental Fit Index (IFI). Besides, the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), the Browne and Cudeck Criterion (BCC), and the Expected Cross-Validation Index (ECVI) are utilized for comparing the goodness-of-fit of competing models (Arbuckle 2013; Hair et al. 1998). Table 4 presented the lowest acceptance quantities for these indices.

Results and discussion

Respondent profiles

Table 2 displays the demographic characteristics of respondents. 63.2% of the percipients were female and 35.8% were male. Participants’ age ranged from 17 to 70 years with a mean of 30 (SD = 21.85). A majority of survey participants were younger than 34 years old (71.50%) and the average age was 31 years. About 67.10% of respondents had college degrees. Self-employment (29%), housekeeper (23.20%), and student (21.40%) were the highest respondents’ occupation. The average income of the participants was 450.25 $ (SD = 165.18) and most of them (85.90%) had low income (below 750 $). According to the 2016 census (SCI 2019), the population of Iran has the following characteristics: its sex ratio is 102; the percentage of population aged 25–64 years is 50; people employed in the public sector is 16.7%; the average household income is about $ 720; The GINI index for urban area is reported at 0.37, and the unemployment rate is 11%. Therefore, the community studied in this survey could almost be a suitable representative of the Iranian population from gender and age distribution of 25–64 aspects.

Measurement model

Table 3 summarized the mean, the standard deviation, and the correlation among the latent variables. As can be seen from this table, there is a positive significant correlation between attitude (M = 4.27, SD = .54, p < .01), subjective norm (M = 3.75, SD = .69, p < .01), perceived behavior control (M = 3.78, SD = .63, p < .01), waste-preventing behavior (M = 3.54, SD = .63, p < .01), intention to reduce waste (M = 3.77, SD = .66, p < .01), perceived ascription of responsibility (M = 4.16, SD = .57, p < .01), and moral attitude (M = 4.23, SD = .55, p < .01). Moreover, the marketing addiction (M = 2.83, SD = .95, p < 0.05) had only a negative significant relationship with two of the parameters (perceived behavior control and intention to reduce waste).

Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was carried out for eight constructs to assess the validity of the measurement model (Table 4). As stated by Hair et al. (1998) CFA was used to examine identification problems such as the high correlation between coefficients and big standard error. The goodness-of-fit of the model is presented in Table 4. The value of χ2/df for CFA model was lower than 2, which fell within the accepted range of 1 to 3. RMSEA was 0.043. It was less than the acceptable value of 0.08. GFI, AGFI, CFI, and IFI have exceeded the recommended values of 0.9. The PGFI is over than 0.5, showing an acceptable model fit.

The internal consistency among the constructs was examined by Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability (Table 1). Kline (2011) suggested that reliability coefficients around 0.9 are categorized as excellent, around 0.8 as very good, between 0.7 and 0.6 as adequate, and below 0.5 as unacceptable. In this study, the reliability coefficients for subjective norm (β = 0.72, p < 0.001), intention to reduce food waste (β = 0.74, p < 0.001), perceived behavior control (β = 0.60, p < 0.001), marketing addiction (β = 0.72, p < 0.001), waste-preventing behavior (β = 0.70, p < 0.001), and moral attitude (β = 0.63, p < 0.001) were adequate. Reliability coefficients of two latent variables—attitude (β = 0.64, p < 0.001) and perceived ascription of responsibility (β = 0.60, p < 0.001)—were considered as acceptable to adequate. Such a low level has been reported in the literature (Abdelradi 2018; Bortoleto et al. 2012; Nguyen et al. 2015).

Structural model

Modeling comparisons

Two models including TPB and ETPB were independently examined and their results were compared using SEM (Table 4). Generally, all structure models showed an adequate fit to data, according to the suggested fit criteria. TPB model provided the best goodness-of-fit due to better-fit indexes, especially smaller value of comparison criteria (e.g., AIC = 145, BIC = 263, BCC = 147, and ECVI = .380). The three constructs in TPB (attitude, subjective norm, and perceived behavior control) described 43.4% of the total variance in waste reduction intention. Eventually, the ETPB model presented a good model fit. All constructs within this explained 62.3% total of variance in intention. TPB and ETPB models were compared against exploratory power for explaining food waste reduction intention. Huh et al. (2009) stated that if the key objective of a study is to explain behavioral intention, the R2 value (proportions of variance) would be preferable to be compared with other model criteria. Thus, ETPB was the best model for the explanation of the intention to reduce food waste. Fitness metrics were used in order to know the predictive power of the models. The goodness-of-fit comparative indexes such as AIC, BIC, BCC, and ECVI of the TPB model, which were presented in Table 4, were lower than another model. Thus, the TPB model can better predict the intention to reduce food waste.

Role of demographic variables

Chi-squared test (χ2) was conducted to evaluate whether socio-demographic profile (gender, age, level of education, income, occupation, and city region) has any effect on the respondents’ intention to reduce food waste. Table 7 presents the statistics of the influence of socio-demographic variables on TPB constructs. As shown in Table 7, there was a statistically significant relationship between some of the socio-demographic characteristics and TPB constructs. For example, gender exhibited significant effect on moral attitude (p > .05) and perceived behavioral control (p > .001). Age had a significant effect on perceived behavioral control (p > .05), intention to reduce food waste (p > .05), and perceived ascription of responsibility (p > .05). In addition, there was a statistically significant relationship between the levels of education, attitude (p > .05), intention to reduce food waste (p > .001), and perceived ascription of responsibility (p > .05). Besides, income had meaningful influence on subjective norm (p > .001), waste-preventing behavior (p > .05), and intention to reduce food waste (p > .001). Moreover, it was found that there was a significant relationship between occupation, subjective norm (p > .001), perceived ascription of responsibility (p > .05), and moral attitude (p > .01). Further, the city region had a significant influence on the perceived ascription of responsibility (p > .05). Marketing/sale addiction do not appear to be statistically significant for any of the socio-demographic variables.

Hypothesis testing

Table 5 and Fig. 2 represent the results of the hypothesis testing based on the ETPB model. The estimates of standardized coefficients indicated perceived ascription of responsibility significantly and positively linked to moral attitude (β = .865, p ≤ .0001), subjective norm (β = .413, p ≤ .0001), and perceived behavioral control (β = .235, p ≤ .05), respectively. Hence, the hypothesis H1, H3, and H5 were supported. Besides, a significant positive effect of moral attitude (β = .527, p ≤ .0001) was observed on attitude towards food waste, which confirms hypothesis H2. In addition, attitude (β = .219, p ≤ .05) positively affected the subjective norm; this provides support on hypothesis H4. Further, attitude (β = .316, p ≤ .001) and marketing addiction (β = .141, p ≤ .05) had a significant positive and negative influence on perceived behavior control, respectively, which supports hypotheses H7 and H8. Also, perceived behavioral control (β = .703, p ≤ .0001) significantly related to waste-preventing behavior, which provided support on hypothesis H9. In contrast, perceived behavioral control had not a significant (p > .05) influence on the intention to reduce food waste. Thus, hypothesis H11 was not supported. The results also indicated that there is a positive significant relationship between subjective norm (β = .238, p ≤ .05) and the waste-preventing behavior (β = .729, p ≤ .05) with people’s intention to reduce food waste, which supports the hypotheses H10 and H12. Besides, socio-demographic variables such as age (p ≤ .05) had a significant effect on the intention to reduce food waste while gender and city region (p ≥ .05) did not have a significant influence. These results provided support for H14 and not supported the H13 and H15 hypotheses.

Regarding the mediating effects, the bootstrapping bias-corrected confidence interval procedure in SEM was used (Table 6). Table 7 presents the mediating relationships existing in the ETPB model. The results show a significant indirect effect of PAR (β = .089, p ≤ .05) on IRFW through SN. In addition, AT (β = .064, p ≤ .05) had a statistically meaningful indirect effect on IRFW through SN. The findings also supported the mediation effect of WPB in the relationship between the PBC (β = .423, p ≤ .01) and IRFW. PAR (β = .022, p ≤ .05) had an indirect influence on IRFW through the mediation of MA, AT, and SN. Meanwhile, a significant indirect effect of MA (β = .030, p ≤ .05) on IRFW through the mediation of AT and SN was found. Generally, the findings revealed that subjective norm had a mediating role in the relationship between perceived ascription of responsibility, attitude, and moral attitude to an individual’s intention to reduce food waste at the household level.

Discussion and implication

This study seeks to provide a deep understanding of the intention to reduce food waste by incorporation of different variables (e.g., attitude, moral attitude, perceived ascription of responsibility, marketing addition, subjective norm, perceived behavioral control, waste-preventing behavior, and intention) into two models (TPB and ETPB), in addition, to investigate whether the demographic variables have a significant effect on the TPB constructs. Also, which theoretical models can better explain the intention to reduce food waste.

This work compares two competing theoretical models (TPB and ETPB) to explain and predict the intention to reduce food waste at the consumer level. As shown in Table 4, the two models showed a reasonable fit to the data, but the ability to explain and predict the intention to reduce food waste was different. If the key goals are to predict the IRFW, the TPB is preferable due to a smaller quantity of comparison criteria (e.g., AIC, BCC, BIC, and ECVI). However, if the key goal is to explain IRFW, the ETPB is perforable due to higher R2 compared with others. This result is inconsistent with Huh et al. (2009), Bai et al. (2014), and Heidari et al. (2018). They concluded that it is better to use a smaller comparative criterion and R2 value to predict and explain behavioral intention, respectively.

The study found that people who have a positive and moral attitude towards the environment and the importance of food waste have a greater intention to reduce food waste, although this influence is developed through the impact on subjective norm and attitude. Mondéjar-Jiménez et al. (2016) investigated the behavior of food waste among Spanish and Italian youth and found similar results. They suggested that the moral attitude plays a significant role in the intention to reduce food waste. Second, perceived behavioral control affects the intention to reduce food waste in a similar way and is one of the variables that can explain the intention to reduce food waste. This is in accordance with our previous studies (e.g., Sánchez et al. (2018), Yadav and Pathak (2017), Mondéjar-Jiménez et al. (2016)). Third, the subjective norm proved to be one of the important factors in explaining the intention to reduce food waste, confirming previous works (Heidari et al. 2018; Mondéjar-Jiménez et al. 2016; Sánchez et al. 2018; Yadav and Pathak 2017). Fourth, waste-preventing behavior was found to be the most important predictor of intention to reduce food waste. That is, individuals who have done activities such as waste reuse, waste minimization, and waste recycling are more likely to produce less food waste. This result, in conjunction with the study of Abdelradi (2018), suggests that waste behavior including reuse, recycling, and minimization have a positive and significant effect on food waste behavior. Besides, waste-preventing behavior mediated the effect of perceived behavioral control on the intention to reduce food waste. Fifth, the sale and marketing strategies which promoted by supermarkets has a direct and significant impact on the perceived behavior control. Mondéjar-Jiménez et al. (2016) concluded that the purchase context could increase the generation of food waste at the customer’s level and have a strong direct impact on their behavior. Sixth, perceived responsibility for environmental issues directly affects moral attitude, subjective norm, and perceived behavioral control. It also indirectly had a significant influence on the moral attitude and subjective norm. In other words, it indirectly had a significant contribution to the explained variance of intention to reduce food waste. We have previously confirmed the same results (Heidari et al. 2018).

Recently, some studies have dealt with the interaction between socio-demographic variables and the TPB constructs in pro-environmental behaviors (e.g., recycling and energy saving) (Botetzagias et al. 2015; Botetzagias et al. 2014). Hence, the effect of demographic variables on the TPB variables was tested. The results showed that some of the demographic variables have a statistically significant influence on TPB constructs. In general, among all socio-demographic characteristics, only age, level of education, and income had a significant impact on the intention to reduce household food waste. It should be noted that the socio-demographic variables together with the other TPB constructs could explain the intention to reduce household food waste. These findings were inconsistent with previous studies (Ajzen 1980; Botetzagias et al. 2015; Heidari et al. 2018).

Visschers et al. (2016) and van der Werf et al. (2019) recommend that food waste reduction interventions should focus on TPB construct such as intention, perceived behavioral control, and attitude. Our findings generally comply with that. Moreover, we suggest that waste-preventing behavior as an additional factor in TPB is a key determinant of intention to reduce food waste. In other words, the results of this study also provide some important practical implications for municipalities and other related organizations to encourage individuals to reduce food waste at home. First, since the attitude, the moral attitude, and the perceived behavioral control have an influence on food waste, some lectures and programs on the topic of environmental protection and the environmental impacts of food waste by organizations could be helpful. These activities can make people understand the consequences of food waste and try to reduce it. In addition, these measures help individual comprehend that they have the ability as well as the responsibility to decrease their food waste. Second, considering the importance of subjective norm on the reduction of food waste, measures should be taken to promote the waste reduction behaviors in the community and make culture. This means the interventions are developed that aims to strengthen the subjective norm as well as the personal attitude that wasting food is not right and should be reduced. It additionally implies raising people’s sustenance education by providing information that enables them to improve their household planning habits. Third, it was found that waste-preventing behaviors could directly affect food waste. Diaz-Ruiz et al. (2015) and Abdelradi (2018) also suggested that waste prevention behavior directly influenced food waste behavior. It means that people who present more positive prevention behavior (such as reuse of old items or not purchasing the unnecessary product) are expected to have a greater intention to reduce food waste. On the other hand, the planning and implementation of solid waste management programs such as 3Rs (Reduce, Reuse, and Recycle) in the city can increase intent to decrease food waste. Finally, marketing and sale strategies such as “buy one, get one free later” and attractive packaging proved to increase food waste generation. Findings from Mondéjar-Jiménez et al. (2016) confirmed that offers, advertisements, and the layout of goods in supermarkets can significantly affect food waste production. Therefore, policymakers should deliberate the role of food companies and retailers when implementing food waste programs.

Limitation and future research

Despite the effectiveness of the results of this study and its practical applications, some limitations should be taken into consideration. First, the study adequately expanded the original TPB model; more extensive variables (e.g., food expenditures, religion, financial attitudes) should be incorporated into this model. Such efforts would help to provide a more comprehensive understanding of intention and behavior to reduce household food waste. In another word, the explanatory power of the proposed framework was 62.3% (i.e., R2 = 0.623), so further studies integrating more effective constructs are still needed to enhance the predictive power of the models. Second, the study is constrained to measuring intention, not real behavior. Thus, future researches should investigate the actual food waste behavior so that the linkage between intention and behavior will be established and the findings will be generalized. Third, a limitation refers to the main outcome measure. It means that the data was collected by the self-report method. In general, the limitation related to self-report measures leads to some errors (e.g., respondents might exaggerate their report of intention to reduce food waste), which may have a negative impact on data quality (Schmidt 2016). Therefore, future studies should try to prevent these errors, for example, at least use forgiving words or, if possible, investigate experimentally the effect of variables on food waste behavior in the community. Forth, our research concentrated on a sample from Iran with the aim to evaluate the intention to reduce household food waste. However, this study provides a basis for initiating further research on why food is wasted in other countries especially in the Middle East.

The evidence presented here deliver several practical applications for future studies on the prevention of household food waste. For example, future research should focus more on (1) assessing other factors that have influence on food waste prevention behavior through TPB model, such as religion, personality, and situational factors, (2) implementation and evaluation the marketing strategy (discounts, size of food packages, etc.) on food waste generation by examining several experimental and control groups over a specified period of time, (3) transferring the results of this research to other samples (samples with larger population size and heterogeneous socio-demographic characteristics), especially in other countries, exploring the effect of cultures on food waste-preventing behavior, and (4) identifying incentives and barriers to reducing food waste at household level.

Conclusion

The individual’s intention to reduce household food waste in the city of Mashhad, Iran, was successfully modeled. For this, many factors including the TPB main variables (attitude, subjective norm, perceived behavior control, and intention) and the new constructs (marketing addiction, the perceived ascription of responsibility, moral attitude, and waste-preventing behavior) combined in a hypothesized model. The extended TPB model improved the explanatory power of the proposed framework in measuring the intention to reduce household food waste. Waste-preventing behavior appeared to be the main predictor of intention to reduce household food waste and interventions should concentrate on establishing this determinant. This can be practiced through further initiation of attitude, moral attitude, the perceived ascription of responsibility, and marketing addiction. Overall, it was found that perceived behavioral control positively affected the subjective norm. Subjective norm also had a mediating role in the relationship between perceived ascription of responsibility, attitude, and moral attitude to intention to reduce household food waste. Finally, age, level of education, and income were those of demographic characteristic which had a significant influence on intention to reduce food waste.

References

(FAO), 2013. Food wastage footprint. Impacts on natural resources, BIO-Intelligence Service, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), 978-92-5-107752-8. http://www.fao.org/3/i3347e/i3347e.pdf

Abdelradi F (2018) Food waste behaviour at the household level: a conceptual framework. Waste Manag 71:485–493

Ajzen I, F.M., 1980. Understanding attitudes and predicting social behavior. NJ: Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs

Ajzen I (1991) The theory of planned behavior. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process 50:179–211

Arbuckle, J.L., 2013. IBM® SPSS® Amos™ 22 User’s Guide. Chicago, IL 60606, USA.

Bai L, Tang J, Yang Y, Gong S (2014) Hygienic food handling intention. An application of the Theory of Planned Behavior in the Chinese cultural context. Food Control 42:172–180

Bamberg S (2003) How does environmental concern influence specific environmentally related behaviors? A new answer to an old question. J Environ Psychol 23:21–32

BIOIS, 2010. Preparatory Study on Food Waste across EU 27., European Commission (DG ENV) Directorate C-Industry, 10.2779/85947, https://ec.europa.eu/environment/eussd/pdf/bio_foodwaste_report.pdf

Bortoleto AP, Kurisu KH, Hanaki K (2012) Model development for household waste prevention behaviour. Waste Manag 32:2195–2207

Botetzagias I, Malesios C, Poulou D (2014) Electricity curtailment behaviors in Greek households: different behaviors, different predictors. Energy Policy 69:415–424

Botetzagias I, Dima A-F, Malesios C (2015) Extending the Theory of Planned Behavior in the context of recycling: the role of moral norms and of demographic predictors. Resour Conserv Recycl 95:58–67

Buchner B, Fischler C, Gustafso E, Reilly J, Riccardi G, Ricordi C et al (2012) Food waste: causes, impacts and proposals. BCFN Foundation. https://www.barillacfn.com/m/publications/food-waste-causes-impact-proposals.pdf

Diaz-Ruiz R, Costa-Font M, Gil J (2015) Are households feeding habits and waste management practices determinant in order to swing over food waste behaviours? The case of Barcelona Metropolitan4 Area., international conference of agricultural economists, Milan, Italy

Fishbein M, Ajzen I (1975) Belief, attitude, intention and behavior: an introduction to theory and research. Addison-Wesley, Reading

Gao L, Wang S, Li J, Li H (2017) Application of the extended theory of planned behavior to understand individual’s energy saving behavior in workplaces. Resour Conserv Recycl 127:107–113

Geislar S (2019) The determinants of household food waste reduction, recovery, and reuse: toward a household metabolism. In: Ferranti P, Berry EM, Anderson JR (eds) Encyclopedia of food security and sustainability. Elsevier, Oxford, pp 567–574

Graham-Rowe E, Jessop DC, Sparks P (2014) Identifying motivations and barriers to minimising household food waste. Resour Conserv Recycl 84:15–23

Gustavsson, J., Cederberg, C., Sonesson, U., van Otterdijk, R., Meybeck, A., , 2011. Global Food Losses and Food Waste: Extent, Causes and Prevention. Rome, Italy. https://ec.europa.eu/knowledge4policy/publication/global-food-losses-food-waste-extent-causes-prevention_en

Hair JF, Anderson RE, Tatham RL, Black WC (1998) Multivariate data analysis, 8th edn. Prentice-Hall, Inc, Upper Saddle River

Halder P, Pietarinen J, Havu-Nuutinen S, Pöllänen S, Pelkonen P (2016) The Theory of Planned Behavior model and students' intentions to use bioenergy: a cross-cultural perspective. Renew Energy 89:627–635

Heidari A, Kolahi M, Behravesh N, Ghorbanyon M, Ehsanmansh F, Hashemolhosini N, Zanganeh F (2018) Youth and sustainable waste management: a SEM approach and extended theory of planned behavior. J Mater Cycles Waste Manage 20:2041–2053

Hossain N (2017) Inequality, Hunger, and Malnutrition: Power Matters. Global Hunger Index. http://www.globalhungerindex.org/issues-infocus/2017.html.

Huh HJ, Kim T, Law R (2009) A comparison of competing theoretical models for understanding acceptance behavior of information systems in upscale hotels. Int J Hosp Manag 28:121–134

Karim Ghani WAWA, Rusli IF, Biak DRA, Idris A (2013) An application of the theory of planned behaviour to study the influencing factors of participation in source separation of food waste. Waste Manag 33:1276–1281

Kline RB (2011) Principles and practice of structural equation modeling, third edition. The Guilford Press, New York

Lipinski B, Hanson C, Lomax J, Kitinoja L, Waite R, Searchinger T (2013) Reducing food loss and waste. UNEP. https://pdf.wri.org/reducing_food_loss_and_waste.pdf

Lyndhurst B (2007) Food behaviour consumer research e findings from the quantitative survey. , Briefing Paper, WRAP, UK

Mondéjar-Jiménez J-A, Ferrari G, Secondi L, Principato L (2016) From the table to waste: an exploratory study on behaviour towards food waste of Spanish and Italian youths. J Clean Prod 138:8–18

Nakouzi, S.R., 2017. Is food loss an issue for Iran? United Nations Iran.

Nguyen TTP, Zhu D, Le NP (2015) Factors influencing waste separation intention of residential households in a developing country: evidence from Hanoi, Vietnam. Habitat Int 48:169–176

Papargyropoulou E, Lozano RK, Steinberger J, Wright N, Ujang Zb, (2014) The food waste hierarchy as a framework for the management of food surplus and food waste. Journal of Cleaner Production 76, 106-115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2014.04.020

Quested TE, Marsh E, Stunell D, Parry AD (2013) Spaghetti soup: the complex world of food waste behaviours. Resour Conserv Recycl 79:43–51

Sánchez M, López-Mosquera N, Lera-López F, Faulin J (2018) An extended planned behavior model to explain the willingness to pay to reduce noise pollution in road transportation. J Clean Prod 177:144–154

Scherhaufer S, Moates G, Hartikainen H, Waldron K, Obersteiner G (2018) Environmental impacts of food waste in Europe. Waste Manag 77:98–113

Schmidt K (2016) Explaining and promoting household food waste-prevention by an environmental psychological based intervention study. Resour Conserv Recycl 111:53–66

Statistical Center of Iran, 2019. Population. Iran. https://www.amar.org.ir/english.

Silva JGD (2016) Food losses and waste: a challenge to sustainable development, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). http://www.fao.org/save-food/news-and-multimedia/news/news-details/en/c/429182/.

Stefan V, van Herpen E, Tudoran AA, Lähteenmäki L (2013) Avoiding food waste by Romanian consumers: the importance of planning and shopping routines. Food Qual Prefer 28:375–381

Taylor S, Todd P (1995) Understanding household garbage reduction behavior: a test of an integrated model. J Public Policy Mark 14:192–204

Tonini D, Albizzati PF, Astrup TF (2018) Environmental impacts of food waste: learnings and challenges from a case study on UK. Waste Manag 76:744–766

van der Werf P, Seabrook JA, Gilliland JA (2019) Food for naught: Using the theory of planned behaviour to better understand household food wasting behaviour. The Canadian Geographer / Le Géographe canadien 63(3):478–493. https://doi.org/10.1111/cag.12519

Visschers VHM, Wickli N, Siegrist M (2016) Sorting out food waste behaviour: a survey on the motivators and barriers of self-reported amounts of food waste in households. J Environ Psychol 45:66–78

Wahlen S, Winkel T (2017) Household food waste, in: Smithers, G.W. (Ed.) Reference Module in Food Science. Elsevier.

Yadav R, Pathak GS (2017) Determinants of consumers’ green purchase behavior in a developing nation: applying and extending the theory of planned behavior. Ecol Econ 134:114–122

Zaki M (n.d.) Reducing food loss and waste in the Near East and North Africa, Regional Conference for the Near East (NERC-32). Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge Dr. Mahdi Kolahi and all the people who completed the survey questions. In addition, special thanks go to the Faculty of Natural Resources and Environment of the Ferdowsi University of Mashhad for creating a research opportunity for us.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Responsible editor: Philippe Garrigues

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Heidari, A., Mirzaii, F., Rahnama, M. et al. A theoretical framework for explaining the determinants of food waste reduction in residential households: a case study of Mashhad, Iran. Environ Sci Pollut Res 27, 6774–6784 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-019-06518-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-019-06518-8