Abstract

In response to the increasing global concerns about food waste and its effects on human communities, the present study aims to identify food waste behavior antecedents for households during the COVID-19 pandemic in Iran. An integrated framework was proposed grounded on the Theory of Planned Behavior and the Protection Motivation Theory. Based on a survey with 405 respondents, the underlying determinants of food waste behavior among Iranian households were identified and data were analyzed with Covariance based Structural Equation Modeling. In this study, perceived behavioral control, attitude, and coping appraisal were found to impact households’ intention to reduce food waste positively. Conversely, subjective norms and threat appraisal were not found to positively impact such intention. Furthermore, a slight negative effect of the intention to reduce food waste on this FW reduction behavior was observed. The threat of COVID-19 infection did not influence consumers’ intention to reduce food waste, nor did the opinion of close friends and family. This study fills a theoretical research gap in food waste behavioral studies by proposing a novel integrated framework based on the Protection Motivation Theory, which is deemed suitable under high-risk contexts such as pandemics. Moreover, the results provide relevant implications for managers, policymakers, and future research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Food waste (FW) is a primary concern all over the world (Rodgers et al., 2021) in such a manner that its reduction supports the achievement of the United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) number 12 (responsible consumption and production) (Ananda et al., 2023; Fami et al., 2021; Obuobi et al., 2023; Principato et al., 2019). FW is produced during different stages, such as food processing, production, distribution, and consumption (Y. Zhu et al., 2021). Widespread evidence shows that large quantities of edibles are wasted yearly (Stancu et al., 2016) and households are known to be the biggest food wasters (Visschers et al., 2016). In fact, household food waste (HFW) is around 30% of total food waste (Jribi et al., 2020). Since prevention is considered a crucial pathway to address HFW (Stancu et al., 2016), research on HFW behavior has substantially increased (Russell et al., 2017). Accordingly, mitigating and reducing HFW is urgent (Coşkun & Yetkin Özbük, 2020; Visschers et al., 2016).

Several changes to people’s food behaviors and routines were observed during the COVID-19 pandemic (Boulet et al., 2021). The main changes in food consumption behavior involved concerns about price increases, FW awareness, safety (Ranjbari et al., 2022), storage constraints, increased cooking, hoarding (Bender et al., 2021), shifting towards healthier diets, and increased consumption of domestic products and online food shopping (Amicarelli et al., 2021; Yetkin Özbük et al., 2021). A particular concern regarding changing food habits relates to the pandemic’s effect on HFW. There is a need to assess how households behave during a crisis, such as the coronavirus outbreak, and the dynamics of HFW (Filimonau et al., 2021) because an outbreak as the COVID-19 pandemic is considered an external risk factor that can influence consumers’ food purchasing and consumption behavior (Li et al., 2022). Moreover, not much is known about how people perceive risks related to food waste in the context of emerging infectious diseases (Deliberador et al., 2023).

Although literature regarding the effects of COVID-19 on food systems is growing, changes in the household food supply, consumption, and waste behavior are still poorly understood (Babbitt et al., 2021). Less attention has been paid to the study of FW in understanding the relevant determinants of consumer behavior, especially in household contexts (Russell et al., 2017; Stancu et al., 2016; Stefan et al., 2013; Visschers et al., 2016). Comprehending FW antecedents is required to investigate this subject (Lourenço et al., 2022) and design FW reduction policies. Notably, consumer behavior has been considered crucial to identify FW causes and consequences and design initiatives to reduce them (Wilson et al., 2017). Indeed, any effective intervention aimed at HFW reduction requires acknowledging the relevant FW background (Graham-Rowe et al., 2015).

Since different factors contribute to the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on consumer behavior (Hassen et al., 2021) and given that HFW behavior is considered a complex phenomenon driven by multiple motivations (Mondéjar-Jiménez et al., 2016; Quested et al., 2013; Russell et al., 2017), more comprehensive modeling is needed for the study of HFW behavior during the COVID-19 outbreak. Few comprehensive frameworks of HFW and consumer behavior are, in fact, available to support specific initiatives and guide further studies (Boulet et al., 2021). Besides, Visschers et al. (2016) pointed out the lack of a comprehensive model explaining consumer behavior towards FW (Russell et al., 2017).

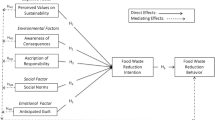

In order to fill these research gaps, this study’s goal was to identify the determinants of HFW behavior during the COVID-19 pandemic. To do so, we developed a comprehensive framework built upon the integration of the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) (Ananda et al., 2021; Graham-Rowe et al., 2015; Lin & Guan, 2021) and Protection Motivation Theory (PMT) (Adunlin et al., 2021; Chen, 2020; Rather, 2021), which are commonly established frameworks in consumer behavior. The identification of the determinants of HFW will support the design of FW reduction programs focused on elements that contribute to increase people’s intention to reduce FW. Therefore, this study provides guidelines for how policies, programs, and campaigns should explore consumers’ vulnerability and exposure to the risk of serious complications resulting from disruptions to reduce food waste.

Some of these study’s contributions are addressed to scholars, practitioners, and policymakers. The proposed integrative framework combines the TPB and PMT to identify food waste behavior’s background in the context of the pandemic. To the extent of our knowledge, the integrated use of both theories in FW studies is novel, mainly when applied in studies framed in the pandemic context. Moreover, from a methodological perspective, studies about HFW behavior determinants often take a qualitative approach (Russell et al., 2017), with only a limited number of quantitative studies published (Attiq et al., 2021). This research extends previous studies by using structural equation modeling (SEM) as a well-established quantitative method for analyzing the integrated theoretical framework. Finally, this study also contributes to the design of solutions to mitigate HFW in emerging economies.

2 Contextual background

The proposed integrated framework was assessed in Iran. This choice was made based on evidence that Middle Eastern countries have a high share of food waste (Heidari et al., 2020). In Iran, an emergent economy with a young population and an agri-food system under transition (Ghaziani et al., 2021), the amount of food waste and loss almost reaches twice the world average, especially for fruit and vegetable residues (Esmaeilizadeh et al., 2020). Therefore, researchers claim the need to implement food consumption management programs as well as food waste control practices (Fami et al., 2021) to support the reduction of the environmental problems faced by the country (Shafiei & Maleksaeidi, 2020). Data about HFW in the country are scarce and fragmented and mostly focused on specific locations (Allahyari et al., 2022). Besides, FW interventions have been mostly investigated in North America and Europe, so studies in the Middle East are still lacking (Abdelaal et al., 2019), being this region underrepresented in FW research (Rolker et al., 2022). According to FAO, in Middle East countries, inadequate data, lack of awareness, inappropriate public policies and regulations, and lack of resources undermine FW reduction initiatives (FAO, 2015). During the pandemic in Iran, food waste, the number of shopping trips, and the amount of money spent on groceries were reduced (Allahyari et al., 2022), but there is still a gap concerning the determinants of HFW in the pandemic’s context in the country. Moreover, little is known about FW management behaviors, attitudes, and beliefs (Abadi et al., 2021). Therefore, understanding this conduct in Iran is very important for ensuring the sustainability of its economic development and decreasing food insecurity in Iranian households (Fami et al., 2021).

3 Literature review hypotheses formulation

Different household factors influence the adoption of measures against FW, such as the cultural background (Ananda et al., 2021), some socio-demographic factors, FW knowledge, personal beliefs, social guidelines, and the complexity of food management practices (Cerciello & Garofalo, 2018; Vargas-Lopez et al., 2021), besides extreme and atypical conditions—such as lockdowns triggered by the COVID-19 pandemic—which can influence food consumption behavior (Eroğlu, 2020; Hobbs, 2020a; Islam et al., 2021).

Distinct types of consumption habits have been observed across the world as well as during different phases of the pandemic, with several effects on FW behavior. For example, customers modified their consumer behavior, increasing their food consumption at home and shopping of local products (Blazy et al., 2021). The pandemic also led to price spikes, panic buying (Galanakis et al., 2021), an increase in the demand for ready-meals (Hobbs, 2020b), and the fear of food shortages, which made customers look for alternative sources of supply, probably buying items in larger amounts (Zhu & Krikke, 2020). Consumer FW behavior can be observed during shopping habits, food storing and conservation, and eating habits and serving food (Aydın & Yildirim, 2020; Wansink, 2018). Some habits that characterize FW behavior are, for example, not preparing a shopping list prior to grocery shopping; not storing food correctly, and cooking too much food (Principato et al., 2020a).

Due to the first lockdown measures, consumers stockpiled products fearing price increases and food availability concerns (Bender et al., 2021). Panic buying made people purchase excessive amounts of food, leading to subsequent struggles over the use of these surpluses (Ananda et al., 2021). However, ethical food management practices, such as shopping lists and meal plans, have been implemented, which reduced FW. Without any other alternative but shopping only a few times a week during restricted periods, most people came to manage their domestic food consumption more carefully, resulting in less waste (Vargas-Lopez et al., 2021). Other measures adopted to decrease FW amounts during the pandemic include improvements in food management and cooking tasks (Masotti et al., 2023).

Although awareness of environmental issues in society has increased, it would be plausible to observe some weakening toward adopting sustainable initiatives in households due to the challenges and changes imposed by the pandemic. In this regard, the Theory of Planned Behavior—used to predict behavioral intentions—has been predominantly adopted in the environmental research field, especially in topics related to FW reduction and management (Ananda et al., 2021; Graham-Rowe et al., 2015; Lin & Guan, 2021; Stancu et al., 2016; Stefan et al., 2013; van der Werf et al., 2019; Visschers et al., 2016). This theory considers the intention to conduct a particular behavior as its most important driving force. In this case, intention refers to an individual’s willingness and commitment to adopt FW management practices (Wang et al., 2019). Under this theory, three constructs determine someone’s intention to behave in a certain way: attitude, subjective norm, and perceived behavioral control (Heidari et al., 2020), as follows.

Perceived behavioral control (PBC) refers to an individual’s perception of the ease or difficulty associated with performing a particular conduct (Ajzen, 1991). It reflects the individual’s perception of their ability to engage with the behavior (Lin & Guan, 2021). For instance, in an FW context, it could indicate a person’s subjective belief regarding the ease or difficulty when implementing FW initiatives (Wang et al., 2019), such as reducing FW or planning and shopping for food (Heidari et al., 2020). Some scholars have demonstrated that the PBC positively influences consumers’ intention to reduce FW (Abadi et al., 2021; Mondéjar-Jiménez et al., 2016; Russell et al., 2017; Visschers et al., 2016), while others did not corroborate this relationship (Graham-Rowe et al., 2015; Stancu et al., 2016; Stefan et al., 2013). Further research is needed to assess the influence of the PBC on the intention to reduce FW, especially in studies performed within the pandemic context. Thus, the first hypothesis of this study is presented:

Hypothesis 1

The perceived behavioral control has a significant positive effect on the food waste reduction intention.

The second component of the TPB relates to subjective norms, which refers to an individual’s perception of the social pressure to perform a given behavior (Ajzen, 1991; Lin & Guan, 2021). It is determinant of specific behaviors, such as the one addressed to FW disposal (Graham-Rowe et al., 2015; Heidari et al., 2020; Stefan et al., 2013), and summarizes the social pressures to reduce FW (Wang et al., 2019). There has been increasing pressure from external stakeholders like governments (Lin & Guan, 2021), non-governmental organizations, and society to implement sustainability measures (Barbosa & Oliveira, 2021; Filatotchev & Stahl, 2015). Consumers are likely to feel this pressure, and this perception might reflect on their FW reduction intentions and behavior. Indeed, it has been found that subjective norms greatly influence the intention to perform environmental behaviors (Ranjbar et al., 2022). While some researchers consider subjective norms as significant intention predictors to reduce FW (Abadi et al., 2021; Russell et al., 2017; van der Werf et al., 2019), Stefan et al. (2013) did not corroborate this idea, showing that further research is still needed to clarify this relationship. In this context, our second hypothesis is presented:

Hypothesis 2

Subjective norms have a significant positive effect on food waste reduction intention.

Attitude is an individual’s favorable or unfavorable assessment when implementing a certain behavior (Ajzen, 1991), and it measures their belief coming from the outcome of that behavior (Lin & Guan, 2021). It is one of the main determinants of behavioral intentions, like wasting food (Graham-Rowe et al., 2015; Visschers et al., 2016). People with higher negative attitudes have a greater negative behavioral intention and vice versa (Heidari et al., 2020). Besides, the available literature has indicated a positive effect of attitude over the intention to reduce FW (Abadi et al., 2021; Stancu et al., 2016; Stefan et al., 2013). However, a study conducted by Russell et al. (2017) did not yield such result. In this context, our third hypothesis is presented:

Hypothesis 3

Attitude has a significant positive effect on the food waste reduction intention.

Despite the established usefulness and essential role of the TPB in the theoretical development and behavioral analysis of FW prevention behavior, this theory has been criticized (Attiq et al., 2021; Burlea-Schiopoiu et al., 2021; Graham-Rowe et al., 2015; Mondéjar-Jiménez et al., 2016; Schmidt, 2019; Stancu et al., 2016; Stefan et al., 2013; Visschers et al., 2016), especially regarding the model suitability for designing behavior change interventions. Some authors consider it has a moderate explanatory power for behavioral intention (Heidari et al., 2020). Consequently, by associating the TPB with other theories, researchers could identify different factors affecting consumers’ behavior and support models with higher prediction power (Fozouni Ardekani et al., 2021). Therefore, several studies, including research carried out during the pandemic context, have called for an integrated or extended TPB-based model (Chu & Liu, 2021; Cobelli et al., 2021; Guidry et al., 2021; Prasetyo et al., 2020; Si et al., 2021; Xia et al., 2021). Since FW management is a multi-dimension problem, an integrated model is considered more suitable to investigate this phenomenon (Wilewska et al., 2020). One theory used along with the TPB in food behavior research is the Protection Motivation Theory (Mullan et al., 2016). Therefore, this study used it as a theoretical model to extend TPB since it is suitable for risk-intense environments like the one emerged from the pandemic context.

Several studies have applied the PMT as a predictive framework in human behavioral and motivational studies, particularly the ones that came up from the COVID-19 pandemic context (Farooq et al., 2020, 2021; Laato et al. 2020a, 2020b; Ling et al., 2019; Tang et al., 2021). Initially proposed by Rogers (1975), this theory predicts that the components of a person’s fears about an event or outcome could promote a behavioral change to protect them from that same event (Adunlin et al., 2021). It further considers the impact of fear appeals on attitudes and behavior (Mullan et al., 2016) in a way that fearful emotions motivate people to protect themselves from potential threats by changing their attitudes and behaviors (Chen, 2020). Consequently, people tend to change their behavior if they believe such a change will be effective against a threat, as well as beneficial and cost-effective (Hanson et al., 2021). Hence, PMT assumes that an individual’s decision to adopt risk-preventive behaviors is made based on their desire to protect themselves from threats like pandemics (Adunlin et al., 2021).

PMT addresses both risk and adaptation by taking into account two cognitive processes: threat and coping appraisal (Villamor et al., 2023). Adaptation is a process that supports the reduction of existing threats. Hence, in FW management contexts, adaptation refers to someone’s ability to cope with the changes associated with food availability (Zobeidi et al., 2021).

The theory hypothesizes that people take protective actions against threats after thoroughly assessing them and implementing coping mechanisms (Wang et al., 2019), which predicts one’s behavioral intention. Threat appraisal identifies whether an individual believes they are vulnerable to the threat and if its impact would be severe (Mullan et al., 2016). It is the result of one’s perceived vulnerability to the adverse consequences of the threat (Eberhardt & Ling, 2021). Threat appraisal refers to the degree to which one perceives a situation (e.g., a pandemic) as serious and considers being vulnerable; it also involves concerns about harm to oneself and to friends (Tang et al., 2021).

In this sense, threat appraisal assesses adverse risks considering their perceived severity and vulnerability (Chen, 2020; Rather, 2021), which reflects how serious an existing risk is perceived (Wang et al., 2019). Perceived severity refers to the degree of someone’s perception regarding the harmfulness of a given threat, while perceived vulnerability refers to the assessment of the chance to experience a particular threat (Tang et al., 2021). In this study, perceived severity refers to how people were aware of the adverse effects caused by the pandemic, while perceived vulnerability states how likely they are to suffer the consequences of a COVD-19 infection.

Several studies have observed a positive relationship between the perceived severity, intention and behavior in different contexts (Ling et al., 2019; Prasetyo et al., 2020). In COVID-19 settings, Farooq et al. (2020) observed that perceived severity positively impacted self-isolation intention, while Tang et al. (2021) found that perceived severity directly influenced information security behavior toward pandemic scams. In an environmental context, Janmaimool (2017) identified that the perceived severity of the adverse effects of pollutants could significantly explain waste disposal, reuse, and recycling behaviors. Finally, severity positively affected the substandard food purchase intention (Jang & Lee, 2022).

However, there is little consensus on the relationship between perceived vulnerability, intention, and behavior. While some researchers have found such influence to be positive (Ling et al., 2019; Tang et al., 2021), others observed a significant but rather indirect effect on intention (Prasetyo et al., 2020) and a partial effect on behavior (Janmaimool, 2017), or even found that vulnerability does not impact intention at all (Jang & Lee, 2022).

As food waste-related risk perceptions may differ among individuals and contexts, FW behavior is considered an essential factor in people’s decision-making process. We understand that using the PMT can probably improve our understanding of FW behavior concerning the COVID-19 pandemic, including people’s perceptions of the pandemic’s risks and consequences. This context leads to the presentation of our fourth hypothesis:

Hypothesis 4

Threat appraisal has a significant positive effect on food waste reduction intention.

As previously mentioned, PMT states that individuals take protective measures against threats after assessing risks and coping mechanisms. Upon perceiving a threat, the individual selects adaptive or preventive initiatives to reduce the negative emotional state caused by it. This process is known as a coping appraisal (Mullan et al., 2016). Coping appraisal is the personal assessment of an individual’s ability to deal with a threat based on response efficacy, self-efficacy, and response costs (Farooq et al., 2020; Teasdale et al., 2012). Response efficacy refers to the perceived effectiveness of the recommended risk preventive measures, i.e., the individual is not only willing to adopt these measures but is motivated enough to keep up with them despite eventual personal discomfort, perceived lack of results, or slowness in implementing these measures (Adunlin et al., 2021). Therefore, individuals expect and adopt recommended behaviors to remove the threat. In other words, a recommended response will effectively avoid an adverse risk. Self-efficacy is a person’s expected capability to perform a recommended coping behavior (Wang et al., 2019), and it deals with their perceived ability when performing specific actions in a situation. Thus, protection motivation is higher for people with greater access to several resources to eliminate or reduce the threat (Chen, 2020). The response cost is the cost of carrying out the recommended behavior, including all perceived costs associated with protective measures. A high cost of preventive measures will discourage people from adopting these recommended behaviors (Adunlin et al., 2021).

Other studies have assessed coping appraisal dimensions’ effects on intention in different contexts. While most studies show positive impacts of response efficacy on the intention and protective behavior (Jang & Lee, 2022; Ling et al., 2019; Tang et al., 2021), Janmaimool (2017) found that response efficacy was not a significant predictor of all behaviors studied and did not find any relationship between response efficacy and self-isolation intention during the pandemic (Farooq et al., 2021). Furthermore, researchers have established a consensus regarding the relationship between self-efficacy and intention. They observed that self-efficacy positively impacts the intention in different contexts (Farooq et al., 2020; Jang & Lee, 2022; Janmaimool, 2017; Ling et al., 2019; Tang et al., 2021). The relationship between self-efficacy and protection motivation has been considered the most consistent across the PMT elements (Mullan et al., 2016). Regarding response costs, negative correlations between costs and intention were found in the literature under different circumstances (Farooq et al., 2020, 2021; Wang et al., 2019). However, Ling et al. (2019) did not observe the predicting role of this variable toward intention.

PMT hypothesizes that, when facing a threat to their health, individuals are likely to adopt a protective behavior if they believe they would be more vulnerable to that threat if they do not do it. Therefore, adopting such protective behavior will reduce that threat (Eberhardt & Ling, 2021). For this study, we believe people adopt FW management initiatives if they feel they are likely to suffer from the negative consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic. This context leads to our fifth hypothesis:

Hypothesis 5

Coping appraisal has a significant positive effect on food waste reduction intention.

The best way to predict behavior is to analyze the intention to perform it (Mondéjar-Jiménez et al., 2016). Behavioral intentions describe the degree to which people are willing to have the referred behavior. The stronger someone acknowledges the intention to perform a specific behavior, the more likely that person will conduct it (Lin & Guan, 2021). For PMT and TPB, behavioral intention is an essential precursor to behavior and indicates one’s readiness to implement a behavior (Eberhardt & Ling, 2021; Hanson et al., 2021). For PMT, intention most closely predicts behavior (Eberhardt & Ling, 2021). In this regard, the relationship between FW reduction intention and FW behavior has shown contradictory results. Graham-Rowe et al. (2015) and Prasetyo (2020) found that intention was a significant predictor of behavior. Abadi et al. (2021) found that behavioral intention strongly influences FW management behavior. Van der Werf et al. (2019) observed that intention has a limited impact on predicting FW behavior. Russel et al. (2017) and Luu (2021) observed a negative impact of intention to decrease FW on FW behavior; that is, the higher the intention to reduce FW, the lower the amount of food wasted. Finally, Stefan et al. (2013) did not observe this relationship between intention and behavior. Since the effects of FW reduction intention on FW are still not apparent, especially under the pandemic context, the sixth hypothesis of this study is presented:

Hypothesis 6

Food waste reduction intention has a significant negative effect on food waste behavior.

The theoretical framework of this study, including the six hypotheses, is presented in Fig. 1.

4 Methodology

This section presents the study’s methodology, which is composed of the following steps: (1) instruments, (2) participants, (3), data collection, and (4) data analysis. Figure 2 presents a flowchart of the main phases of our study, which will be described as follows.

4.1 Instruments

A standardized questionnaire was developed based on the different constructs of the theoretical framework derived from extant scientific literature (Table 1). All constructs’ measurement items have been validated by previous studies and are shown in Appendix 1. All items were measured using a five-point Likert scale, ranging from “1” (strongly disagree) to “5” (strongly agree). A pilot study was conducted with 30 respondents to test the survey and consumers’ understanding of its content. Results confirmed the internal consistency and reliability of the different theoretical constructs.

4.2 Participants

Table 2 displays the profile of the sample of 405 Iranian respondents of the survey. Most of the respondents are female (65.4%), single (59.30%), young (average age = 31.12 years) and most of them have at least a bachelor’s degree (88.70%). Our sample is similar to the one reported by Allahyari et al. (2022) in a study of Iranian household FW behavior during the COVID-19 era. According to the researchers, the characteristics of the sample are influenced by the way data was collected (through social media and Internet), which are mostly used by educated and young users with specific knowledge and skills.

According to Davern et al. (2005), people's lack of interest in expressing their income is one of the challenges of income measurement. Asking questions about income is sensitive and undesirable for respondents and might lead to an increase of the probability of missing data occurrence. Therefore, this paper used the measurement items that minimize the occurrence of such a challenge, following recommendations published in the literature (Hassen et al., 2021).

4.3 Data collection

This study was conducted using an online survey in Iran. The target population was Iranian adults with a minimum age of 18. Due to implementation of COVID-19 restrictions by the Iranian government and the necessity of social distancing while conducting the research, online survey, random and snowball sampling were used. The use of this method is acceptable because, under the COVID-19 epidemic limitations, the success of other methods is unlikely and the use of snowball sampling has important advantages for research (Allahyari et al., 2022). Therefore, a standardized questionnaire was developed in English, translated into Persian, and sent to participating Iranian consumers through email and a social network professional platform, Porsline (https://survey.porsline.ir). No monetary incentive was given for their participation in the survey. The confidentiality and anonymity of respondents’ answers were also assured.

A total of 412 participants replied to the questionnaire and 405 valid responses were obtained. This sample size fulfills two criteria frequently used to assess its adequacy: 10 times the most significant number of structural pathways or formative items measuring a construct and a minimum of five respondents per measurement item (Attiq et al., 2021). Moreover, to identify the necessary sample size (n) for performing the structural equation analysis, we used the formula proposed by Westland (2010):

in which:

Therefore, for this study, n should be greater than 96, a value far exceeded by the number of valid questionnaires (405); the sample size was considered acceptable. Regarding the analysis, all data were checked regarding missing and outlier values. In addition, the suggested items by Marquart (2017) and Laher (2016) studies, about rigor analysis in quantitative research, were considered separately in all stages of the study (planning, data collection, analysis, and reporting). Therefore, this study followed rigor procedures suggested in the literature.

4.4 Data analysis

Data were analyzed with Structural Equation Modelling (SEM) using IBM SPSS 22 and LISREL 8.5. In this study, since the number of studied samples was greater than 400 and normality indices were at an acceptable level, the Covariance based Structural Equation Modeling (CB-SEM) was adopted. Although CB-SEM and PLS-SEM methods usually provide similar results, researchers have acknowledged that, for a factor-based model, CB-SEM should be employed. Moreover, CB-SEM often provides better fit indices when compared to PLS-SEM (Dash & Paul, 2021).

The research model was appraised in two stages: measurement model and structural model. The first stage (i.e., confirmatory factor analysis) evaluated the construct reliability, convergent validity, and discriminant validity. The second step (i.e., path analysis) involved developing the structural model and measuring the structural relationships represented by the model’s hypotheses (Jöreskog et al., 2016)). Path coefficients and coefficients of determination (R2) were determined for each relationship. The overall fit of the research model was evaluated using the goodness-of-fit (GoF) indices. Assessing a model’s fit is necessary to assure that researchers have not incorrectly omitted important effects. The evaluation of the measurement and the structural model together with fit tests allow the researcher to confirm or reject the proposed research hypotheses (Joreskog & Sorbom, 2006).

SEM is a valuable statistical tool for empirical research that has been extensively adopted in several research areas. This method fulfills the increasing requirements for scientific rigor in academia. SEM is an estimation technique based on regressions focused on the prediction of a set of hypothesized relationships of a research model that maximizes the explained variance in the dependent variables (Dash & Paul, 2021; Nam et al., 2018). For this reason, it is a suitable method to fulfill this study’s objectives.

Before assessing the measurement model, Harman’s one-factor analysis was carried out to detect Common Method Bias (CMB) (Tehseen et al., 2017). Results showed that the total variance extracted by one factor equals 16.17%, less than the acceptable threshold of 50%. As no single factor has emerged accounting for most of the covariance, CMB is considered not to be an issue. Besides, Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) values ranged from 1.05 to 1.68, which is smaller than the threshold of 4 (O’Brien, 2007). Therefore, the model does not present any multicollinearity problems.

5 Results and discussion

5.1 Measurement model

Table 3 displays the Goodness-of-Fit indices used to assess the measurement model’s quality and overall prediction performance. In this regard, all estimated values met the recommended threshold values derived from the literature. Hence, the fit of the research model is demonstrated.

Factor loadings, average variance extracted (AVE), and composite reliability (CR) were assessed (see Appendix 1) to evaluate convergent validity. All factor loadings were higher than 0.5 and significant at p < 0.01. Additionally, AVE and CR values exceeded the minimum threshold values (greater than 0.5 and 0.7, respectively), demonstrating that relevant constructs were estimated (Kline, 2015). Discriminant validity was confirmed based on the findings of the Fornell-Larcker criterion, as the square root of AVE values are greater than the inter-construct correlations, as shown in Table 4 (Fornell & Larcker, 1981).

5.2 Structural model

Following our measurement model, estimates were obtained for the structural model relationships, which represent the hypothesized associations among constructs.

Table 5 shows each hypothesis’ path coefficients (β) and t-values. Path coefficients can be interpreted as the standardized beta coefficients in a regression equation, varying between − 1 and + 1. Values close to + 1 represent strong positive relationships, while values close to − 1 represent strong negative relationships. When the exogenous construct is changed by one unit, the endogenous construct is changed by the value of the path coefficient considering the other elements of the model remain constant.

The results confirmed hypothesis H1, demonstrating that perceived behavioral control significantly and positively impacts consumers’ intention to reduce FW (β = 0.11). However, no significant effect of subjective norms on the intention to reduce FW was observed. Therefore, hypothesis H2 was rejected. A significant and positive effect of attitude on the intention to reduce FW (β = 0.55) was identified, supporting hypothesis H3. Hypothesis H4 was rejected since no direct and significant influence of threat appraisal on the intention to reduce FW was reported. Coping appraisal has a significant, positive influence on the intention to reduce FW (β = 0.18), in line with H5. Furthermore, the findings further confirmed that the influence of the intention to reduce FW on food waste behavior was significant and negative (H6: β = − 0.26). Regarding all relationships, attitude appears to be the main factor explaining consumers’ intention to reduce FW.

One of the commonly used measures to evaluate the structural model’s predictive power is the coefficient of determination (R2). It is calculated as the squared correlation between a specific endogenous construct and predicted exogenous variables. It represents the amount of variance in the endogenous constructs explained by all the exogenous constructs related to it. In marketing research, an R2 value of 50% is considered moderate. Figure 3 depicts the path coefficients and R2 values obtained in this study for the structural model. The coefficient of determination was relatively high for the intention to reduce FW (42%) but surprisingly low for FW behavior (6.5%).

5.3 Discussion

Every year, nearly one-third of the food is wasted or lost worldwide, leading to environmental degradation, food security problems, and economic inefficiency. Given that households produce the most significant proportion of FW (Lin & Guan, 2021), this kind of FW is considered a crucial challenge for governments to support a sustainable food system (Everitt et al., 2021). Moreover, the latest disruptions caused by the COVID-19 outbreak affected food consumption, further impacting the supply chain through product shortages and price spikes, influencing consumer preferences. Besides, changes regarding consumers’ FW management and practices during the pandemic stimulated organizations and public institutions to prioritize FW challenges (Vittuari et al., 2021). These challenges and changes associated with consumer behavior during the COVID-19 pandemic also led researchers to question the use of established theoretical models previously developed and validated in non-pandemic settings (Burlea-Schiopoiu et al., 2021). As current theoretical models alone might not be sufficient to describe FW behavior in pandemic times, this study proposes an integrated framework.

In light of the universal need to consider FW as a present and future concern (Rodgers et al., 2021; Russell et al., 2017), especially when it comes to consumer behavior at the household level (Russell et al., 2017; Stancu et al., 2016; Stefan et al., 2013; Visschers et al., 2016) and during the COVID-19 era (Babbitt et al., 2021), this study investigated households’ intention and behavior related to FW mitigation during the COVID-19 outbreak. It combined the TPB and PMT to determine the intention’s background that led to FW reduction and behavior. Although past research also adopted similar integrated models to study FW management (Attiq et al., 2021; Burlea-Schiopoiu et al., 2021; Schmidt, 2019; Stancu et al., 2016), to the best of our knowledge, the application of this combined theoretical framework within the COVID-19 pandemic context in a developing country had not been carried out so far.

Our findings showed that factors grounded in the TPB and PMT could explain 42% of the variance in consumers’ intention to reduce FW. Among all the different paths through which potential factors can lead to an increased intention to reduce FW, several constructs from both theories influence households’ intention to reduce FW. This great explanatory power contrasts with the finding that the intention to reduce FW only explained 6.5% of the variance in FW behavior.

While few studies on FW reduction reported a lack of significance for attitude (Russell et al., 2017) and the PBC (Graham-Rowe et al., 2015; Stancu et al., 2016; Stefan et al., 2013), our study demonstrated a positive influence of both concepts for consumer’s intention to reduce FW, with attitude as the dominating factor. This outcome corroborates previous research on the role of PBC (Abadi et al., 2021; Mondéjar-Jiménez et al., 2016; Russell et al., 2017; Visschers et al., 2016) and attitude (Abadi et al., 2021; Stancu et al., 2016; Stefan et al., 2013) on FW reduction intentions in other contexts. Hence, Iran’s pandemic experience did not seem to have worsened people’s attitude and motivation to reduce FW. Instead, in line with Lamy et al. (2022), people reported a serious concern with FW. As previously observed, the pandemic might have encouraged pro-environmental attitudes leading to an increased intention to reduce FW (Jian et al., 2020).

Moreover, this study showed that coping appraisal positively affects the intention to reduce FW. Coping appraisal is related to response efficacy (perceived effectiveness of preventive measures), self-efficacy (a person’s expected capability in performing a behavior), and response costs (the cost of performing the recommended behavior). Facing the threats brought on by the pandemic, respondents’ capacity and perception towards the preventive measures adopted to deal with the outbreak positively influenced their intention to reduce FW. The more consumers considered themselves ready to adopt these actions and believed that these risk responses were adequate to maintain their living conditions during the COVID-19 pandemic, the more positive they intended to reduce FW.

Hence, this study has found that the determinants of the intention to reduce FW in pandemic contexts under the TPB and PMT are attitude, perceived behavioral control, and coping appraisal. These findings are summarized in the proposed model, depicted in Fig. 4, that shows the determinants of the intention to reduce food waste in pandemic contexts.

Hypothesis H2, which stated that subjective norms could have a significant positive effect on the intention to reduce FW, was rejected. This finding contradicts other studies (Abadi et al., 2021; Russell et al., 2017; van der Werf et al., 2019) but agrees with Stefan et al. (2013). Aligned with our results, La Barbera and Ajzen (2020) and Abu Hatab et al. (2022) observed that subjective norms are relatively unimportant in determining behavioral intentions. Armitage and Conner (2001), in a review of TPB studies, identified subjective norm as the weakest predictor of intentions. Although subjective norms have been found to influence the intention to perform environmental behaviors (Ranjbar et al., 2022), we have not observed such relationship regarding FW reduction. Since FW behavior might be less visible than other pro-environmental behavior, such as recycling, subjective norms are less likely to be an essential driver of FW behavior (Russell et al., 2017). In our study, the consciousness level about the importance of minimizing FW might not be high enough to exert influence on others. Given that reducing HFW is an individual behavior dependent also on other people’s behavior (La Barbera & Ajzen, 2020), the lack of predictive power for subjective norms might imply that public policy interventions should play an important role in promoting FW behavior at the societal level (Abu Hatab et al., 2022).

Additionally, this study pointed out that threat appraisal does not significantly affect the intention to reduce FW, which led to the rejection of Hypothesis H4. This issue relates to the perception level of household consumers regarding COVID-19. At the time this study was conducted, some of the respondents still did not consider the disease as a threat to themselves and their relatives, or at least did not take it seriously. Moreover, the risk of getting COVID-19 was not assessed as severe by consumers, nor did they consider themselves vulnerable to the virus to the extent that it would have influenced their intention to reduce FW. Aligned with our previously reported results, households probably considered themselves ready to face the negative consequences of the pandemic. They also might have considered that the preventive measures already implemented have been efficient, reducing the perceived severity of health and pandemic-related risks. Although previous research proved that, under PMT, threat appraisal predicts protective motivation to undertake preventive measures against the pandemic (Bashirian et al., 2020), our study showed that these preventive measures did not influence consumers’ intention to reduce FW. The level of threat consciousness and its impact might be linked to the (type of) information people can access. For instance, it has been observed that social media usage is associated with FW behavior (Lahath et al., 2021).

Finally, our study showed that the FW reduction intention has a direct negative effect on FW behavior, confirming hypothesis H6, which corroborates previous studies (Abadi et al., 2021; Mondéjar-Jiménez et al., 2016; Russell et al., 2017). As noted by van der Werf (2019), our study identified a limited effect of FW reduction intention across FW behavior, which might indicate the presence of further factors equally influencing FW behavior, such as planning and shopping routines (Stefan et al., 2013). The low correlation between the intention to avoid wasting food and the reported FW behavior in our study could be explained, in part, by the fact that both constructs refer to opposite actions. However, measuring the intention to avoid FW seems more natural since expecting consumers to have the intention to waste food is rather peculiar. Moreover, the extant literature also identifies a phenomenon called the green intention-behavior gap, which occurs when a consumer declares a positive intention towards an environmental behavior, but does not behave as described (Frank & Brock, 2018). Hence, environmental concerns are insufficient to influence consumers’ green behavior (ElHaffar et al., 2020). This gap occurs for different reasons, such as the perception of risks related to sustainable goods (price and availability) (Kim & Rha, 2014), education, income (Park & Lin, 2020), or even due to methodological biases (lack of rigorous methods or measurement limitations) (ElHaffar et al., 2020). Researchers have called for studies that further investigate this weak relationship (Park & Lin, 2020), also observed in our findings. This work is left as future research.

6 Conclusion and policy implications

This study proposed an integrated model for explaining FW behavior antecedents during the COVID-19, grounded on two behavioral theories (TPB and PMT). Data were collected through a survey among Iranian households and analyzed with SEM. Our findings demonstrated that, under the pandemic context, attitude and perceived behavioral control positively and significantly influenced the intention to reduce FW. Among PMT dimensions, coping appraisal also positively affected the intention to reduce FW; however, this effect was not observed for threat appraisal. Findings indicate that the risk of COVID-19 infection and its negative impacts on human health were insufficient to encourage consumers to adopt a FW reduction behavior during the pandemic. It was also found that the intention to reduce FW has a slightly negative influence on FW behavior, i.e., the higher the intention to reduce FW, the lower the amount of food wasted. Researchers and policymakers can use these findings to design solutions and programs to reduce HFW, a major global challenge.

This study identified important gaps in food waste research, specially under pandemic and high-risk environments. The proposed integrated framework, assessed in a survey with Iranian households, fills in these gaps and presents solid and novel contributions to scholars, managers, and policy makers. Table 6 presents and summarizes this study’s main contributions and novel implications in four different dimensions: theoretical, practical, local, and policy making. The study’s contributions are presented in detail as follows.

As previously stated, this study presents practical and theoretical contributions extending the literature on FW intention and behavior considering the context of the COVID-19 pandemic and offering new insights into mitigating and reducing FW, along with implications for future studies. As for its theoretical contributions, our study integrates TPB and PMT to identify the FW behavior background within the pandemic context, increasing the prediction power of the proposed research model. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to embrace both theories in FW contexts. Recently, Jang and Lee (2022) applied PMT to predict people’s behavioral intention to purchase substandard food in response to concerns about environmental problems caused by FW. Besides, previous research grounded on PMT has explored waste management and recycling behavior (Janmaimool, 2017). However, our study is the first to propose an integrated model regarding FW within the pandemic’s context, answering calls made by researchers for further discussion about the relationship between the TPB and PMT (Prasetyo et al., 2020) and for research models that extend TPB (Liu et al., 2022).

Our study extends previous research that has found out that, in Iran, PMT can explain a significant portion of the variance in people’s pro-environmental behavior (Shafiei & Maleksaeidi, 2020). Previous researchers suggested using PMT and TPB together since they could holistically measure environmental behaviors (Ong, 2022) and provide a comprehensive and integrated environmental socio-psychological model to study environmental behavior. Integrated TPB and PMT can be used jointly to exploit their complementary benefits, which allows deeper and more comprehensive understanding of the driving forces behind the environmental behavior and intention (Wang et al., 2019), thus providing a theoretical basis for managing and controlling FW.

This study also provides recommendations for policymakers based on the evidence regarding our model’s significant and non-significant relationships. For instance, the threat of getting infected by the virus has not been considered severe enough to positively impact people’s intention to reduce FW. Thus, policies and activities aimed at exploring consumers’ vulnerability and exposure to the risk of serious infections will not be impactful enough toward the intention to mitigate FW. However, other potentially relevant factors could be linked to economic losses (van der Werf et al., 2019) and the unavailability of resources (Berthold et al., 2022) in disruptive environments.

This study provides contributions to households. Our study showed that perceived behavioral control has a positive and significant effect on households' intention to reduce FW. This means that the ease or difficulty people face to reduce FW influence their intention to reduce FW. Our study also showed that people's attitude towards FW reduction has a positive effect on their intention to reduce FW. This means that there should be more education programs to teach people initiatives and develop in them habits aimed at FW reduction. It is also important that a shared vision of the benefits of FW reduction be shared among citizens, especially with the younger ones. On the other hand, our study showed that subjective norms do not have a significant effect on people's intention to reduce FW. This implies that households are not influenced by others' opinions and beliefs. Instead, an internal vision and motivation towards FW reduction should be developed in the society.

This study also provides contributions to the society. The study showed that, although some determinants of FW intention during the pandemic were identified, these determinants are not sufficient to promote FW reduction behavior. So, we expect this study stimulates households to develop FW reduction habits, that is, households put their intention into practice, by implementing initiatives that will reduce FW at home.

Iran is located in a severely water-stressed region of the Middle East where water crises have often led to negative consequences such as food shortage and insecurity due to the impacts in the country’s agricultural production (Pakmehr et al., 2020). So, to Iran, this study specifically presents important contributions. Due to the relevance of FW in the country, a stream of studies has been observed, which are often focused on the behavioral dimension of food consumption management and its affecting factors at the household level (Heidari et al., 2020; Khosravani et al., 2015; Soorani & Ahmadvand, 2019a, 2019b, 2019c). Just a few recent studies have analyzed the effects of Covid-19 on food consumption and waste. Consequently, there is a significant data gap on FW at the household level, especially in developing countries (Ghaziani et al., 2022). In Iran, accurate and official statistics about FW, especially at the household level, have not been reported so far (Soorani & Ahmadvand, 2019a). Nevertheless, the analysis of relevant studies shows a high and significant amount of FW in Iran. Soorani and Ahmadvand (2019c) reported that the average annual FW among Iranian households is high and alarming, which requires a detailed investigation of the damages and different economic, social, and environmental consequences to the country. The largest volume of waste has been reported regarding bread, rice, and fresh vegetables and fruits (Soorani & Ahmadvand, 2019a). Moreover, few studies have been conducted regarding consumers’ behavior and their antecedents, and a lack of a behavioral-psychological framework is observed (Soorani & Ahmadvand, 2019a, 2019c). Allahyari et al. (2022) also believe that reducing FW is important in order to have sustainable access to food in Iran because the country is facing an economic recession caused by the international sanctions of the United States and its consequences such as reducing purchase power, especially in facing of the Covid-19 outbreak. In addition, Ghaziani et al. (2022) consider the existence of these sanctions as one of the challenges for quantifying and reducing FW in Iran. Due to the reported context of the country, our study presents important contributions and findings that can support public policies aimed at FW reduction in Iran.

From a sustainability point of view, waste reduction is a problem for all three sustainability dimensions, i.e., environmental, social, and economic (Abadi et al., 2021). From an environmental perspective, waste is linked to overproduction and contradicts the pro-environmental approach of a circular food economy (Heidari et al., 2020). This topic is particularly relevant in Iran, a country characterized by problems with water scarcity and pollution in various regions (Karandish et al., 2020). From a social perspective, reducing FW contributes to minimizing hunger-related problems, while from an economic point of view, it can help companies and individuals to optimize their resources. Therefore, this study highlights the importance of designing effective policies to address the challenges and problems caused by FW in all three dimensions of sustainability.

It also provides valuable information for other emerging economies. By identifying FW behavior antecedents within the pandemic context, our study elaborates on previous research, pointing out dimensions to be strengthened by marketing and public campaigns, as well as educational programs on FW aimed at motivating people to engage in an FW-reducing behavior. Thereby, campaigns should be designed to amplify the population’s consciousness and internal motivation of the importance of reducing FW.

This quantitative study had some limitations to be considered when interpreting its findings. The first one relates to the application of self-reported data. Especially in the case of pro-environmental behavior, social desirability bias might be present. This kind of bias occurs when respondents give answers to questions that they believe will make them look good to others. Nevertheless, our study focused more on the relationships between the constructs of the theoretical framework rather than on the values of the (intended) behavior, so we understand that this bias has been reduced. Second, this study adopted quantitative methods only. The adoption of qualitative methods, such as interviews or focus groups, could help to examine the risk of these biases in the study environment and better understand the deeper motivations behind food waste reduction behavior, especially when analyzing the reasons behind hypotheses H2 and H4 rejection. Third, although integrating the TPB and PMT increases the explanatory power of the research model, other possible external components and impacts caused by the pandemic could have influenced food waste behavior and are worthwhile to examine in future research. Fourth, although this study was conducted at a specific timeframe during the COVID-19 pandemic, different waves have been observed worldwide with different effects on people’s lives and health conditions. Consequently, many changes have occurred in household food consumption, public education, health government, and media advice and orientation, which can profoundly affect households’ behavior. Hence, future research must implement behavioral studies comparing different waves, similar to what Vandenhaute et al. (2022) have done. Moreover, longitudinal studies could analyze how household FW behavior has evolved during different waves of the pandemic.

Besides working on the previously presented study’s limitations, future research should assess this study’s research model comparing different groups of households, for example, young, adult, and older people, vaccinated and non-vaccinated people, male and female. It is important to know if there are substantial differences among these groups of people regarding their fear of the COVID-19 pandemic and its consequences. Also, future work should explore differences among types of FW (solid versus beverage) as well as explore settings other than households (restaurants, food retailers, and suppliers). We also suggest that future research analyzes the relationship between FW reduction behavior and other types of pro-environmental behaviors in households, for example, reducing water consumption and avoiding wasting water at home.

Data availability

Datasets generated or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author under reasonable requests.

References

Abadi, B., Mahdavian, S., & Fattahi, F. (2021). The waste management of fruit and vegetable in wholesale markets: Intention and behavior analysis using path analysis. Journal of Cleaner Production, 279, 123802. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.123802

Abdelaal, A. H., Mckay, G., & Mackey, H. R. (2019). Food waste from a university campus in the Middle East: Drivers, composition, and resource recovery potential. Waste Management, 98, 14–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2019.08.007

Abu Hatab, A., Tirkaso, W. T., Tadesse, E., & Lagerkvist, C.-J. (2022). An extended integrative model of behavioural prediction for examining households’ food waste behaviour in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 179(September 2021), 106073. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2021.106073

Adunlin, G., Adedoyin, A. C. A., Adedoyin, O. O., Njoku, A., Bolade-Ogunfodun, Y., & Bolaji, B. (2021). Using the protection motivation theory to examine the effects of fear arousal on the practice of social distancing during the COVID-19 outbreak in rural areas. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 31(1–4), 168–172. https://doi.org/10.1080/10911359.2020.1783419

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

Allahyari, M. S., Marzban, S., El Bilali, H., & Hassen, T. B. (2022). Effects of COVID-19 pandemic on household food waste behaviour in Iran. Heliyon, 8(February), e11337. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e11337

Amicarelli, V., Lagioia, G., Sampietro, S., & Bux, C. (2021). Has the COVID-19 pandemic changed food waste perception and behavior? Evidence from Italian consumers. Socio-Economic Planning Sciences. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seps.2021.101095

Ananda, J., Gayana, G., & Pearson, D. (2023). Has the COVID-19 pandemic changed household food management and food waste behavior? A natural experiment using propensity score matching. Journal of Environmental Management, 328, 116887. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2022.116887

Ananda, J., Karunasena, G. G., Mitsis, A., Kansal, M., & Pearson, D. (2021). Analysing behavioural and socio-demographic factors and practices influencing Australian household food waste. Journal of Cleaner Production, 306(April), 127280. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.127280

Anderson, C. L., & Agarwal, R. (2010). Practicing safe computing: A multimethod empirical examination of home computer. Source: MIS Quarterly, 34(3), 613–643. https://doi.org/10.2307/25750694

Armitage, C. J., & Conner, M. (2001). Efficacy of the Theory of Planned Behaviour: A meta-analytic review. British Journal of Social Psychology, 40, 471–499. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466601164939

Attiq, S., Habib, M. D., Kaur, P., Hasni, M. J. S., & Dhir, A. (2021). Drivers of food waste reduction behaviour in the household context. Food Quality and Preference, 94, 104300. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2021.104300

Aydın, A. E., & Yildirim, P. (2020). Understanding food waste behavior: The role of morals, habits and knowledge. Journal of Cleaner Production, 280 Part I(20 January 2021), 124250. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.124250

Babbitt, C. W., Babbitt, G. A., & Oehman, J. M. (2021). Behavioral impacts on residential food provisioning, use, and waste during the COVID-19 pandemic. Sustainable Production and Consumption, 28, 315–325. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spc.2021.04.012

Barbosa, M. W., & Oliveira, V. M. (2021). The corporate social responsibility professional: A content analysis of job advertisements. Journal of Cleaner Production, 279, 123665. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.123665

Bashirian, S., Jenabi, E., Khazaei, S., Barati, M., Karimi-Shahanjarini, A., Zareian, S., Rezapur-Shahkolai, F., & Moeini, B. (2020). Factors associated with preventive behaviours of COVID-19 among hospital staff in Iran in 2020: An application of the Protection Motivation Theory. Journal of Hospital Infection, 105(3), 430–433. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhin.2020.04.035

Bender, K. E., Badiger, A., Roe, B. E., Shu, Y., & Qi, D. (2021). Consumer behavior during the COVID-19 pandemic: An analysis of food purchasing and management behaviors in U.S. households through the lens of food system resilience. Socio-Economic Planning Sciences. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seps.2021.101107

Berthold, A., Cologna, V., & Siegrist, M. (2022). The influence of scarcity perception on people’s pro-environmental behavior and their readiness to accept new sustainable technologies. Ecological Economics, 196, 107399. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2022.107399

Blazy, J. M., Causeret, F., & Guyader, S. (2021). Immediate impacts of COVID-19 crisis on agricultural and food systems in the Caribbean. Agricultural Systems, 190, 103106.

Boulet, M., Hoek, A. C., & Raven, R. (2021). Towards a multi-level framework of household food waste and consumer behaviour: Untangling spaghetti soup. Appetite, 156(February 2020), 104856. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2020.104856

Burlea-Schiopoiu, A., Ogarca, R. F., Barbu, C. M., Craciun, L., Baloi, I. C., & Mihai, L. S. (2021). The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on food waste behaviour of young people. Journal of Cleaner Production, 294, 126333. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.126333

Byrne, B. M. (1998). Structural equation modeling in LISREL, PRELIS, and SIMPLIS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming. Erlbaum.

Cerciello, M., & Garofalo, A. (2018). Estimating food waste under the FUSIONS definition: What are the driving factors of food waste in the Italian provinces ? Environment, Development and Sustainability. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-017-0080-0

Chen, M. F. (2020). Moral extension of the protection motivation theory model to predict climate change mitigation behavioral intentions in Taiwan. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 27(12), 13714–13725. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-020-07963-6

Chu, H., & Liu, S. (2021). Integrating health behavior theories to predict American’s intention to receive a COVID-19 vaccine. Patient Education and Counseling, 104(8), 1878–1886. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2021.02.031

Cobelli, N., Cassia, F., & Burro, R. (2021). Factors affecting the choices of adoption/non-adoption of future technologies during coronavirus pandemic. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 169(April), 120814. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2021.120814

Coşkun, A., & Yetkin Özbük, R. M. (2020). What influences consumer food waste behavior in restaurants? An application of the extended theory of planned behavior. Waste Management, 117, 170–178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2020.08.011

Dash, G., & Paul, J. (2021). CB-SEM vs PLS-SEM methods for research in social sciences and technology forecasting. Technological Forecasting & Social Change, 173(August), 121092. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2021.121092

Davern, M., Rodin, H., Beebe, T. J., & Call, K. T. (2005). The effect of income question design in health surveys on family income, poverty and eligibility estimates. Health Services Research, 40(5 Pt 1), 1534–1552. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6773.2005.00416.x

Deliberador, L. R., Santos, A. B., Carrijo, P. R. S., Batalha, M. O., César, A. da S., & Ferreira, L. M. D. F. (2023). How risk perception regarding the COVID-19 pandemic affected household food waste: Evidence from Brazil. Socio-Economic Planning Sciences, 87(Part A), 101511. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seps.2023.101511

Díaz, A., Soriano, J. F., & Beleña, Á. (2016). Perceived vulnerability to disease questionnaire: Factor structure, psychometric properties and gender differences. Personality and Individual Differences, 101, 42–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.05.036

Eberhardt, J., & Ling, J. (2021). Predicting COVID-19 vaccination intention using protection motivation theory and conspiracy beliefs. Vaccine, 39(42), 6269–6275. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.09.010

ElHaffar, G., Durif, F., & Dubé, L. (2020). Towards closing the attitude-intention-behavior gap in green consumption: A narrative review of the literature and an overview of future research directions. Journal of Cleaner Production, 275(1 December), 122556. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.122556

Eroğlu, H. (2020). Effects of Covid-19 outbreak on environment and renewable energy sector. Environment, Development and Sustainability. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-020-00837-4

Esmaeilizadeh, S., Shaghaghi, A., & Taghipour, H. (2020). Key informants’ perspectives on the challenges of municipal solid waste management in Iran: A mixed method study. Journal of Material Cycles and Waste Management, 22(4), 1284–1298. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10163-020-01005-6

Everitt, H., Van Der Werf, P., Seabrook, J. A., Wray, A., & Gilliland, J. A. (2021). The quantity and composition of household food waste during the COVID-19 pandemic: A direct measurement study in Canada. Socio-Economic Planning Sciences. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seps.2021.101110

Fami, H. S., Aramyan, L. H., Sijtsema, S. J., & Alambaigi, A. (2021). The relationship between household food waste and food security in Tehran city: The role of urban women in household management. Industrial Marketing Management, 97(August 2019), 71–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2021.06.016

FAO. (2015). Regional strategic framework: reducing food losses and waste in the Near East & North Africa region.

Farooq, A., Laato, S., Islam, A. K. M. N., & Isoaho, J. (2021). Understanding the impact of information sources on COVID-19 related preventive measures in Finland. Technology in Society, 65(April), 101573. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2021.101573

Farooq, A., Laato, S., & Najmul Islam, A. K. M. (2020). Impact of online information on self-isolation intention during the COVID-19 pandemic: Cross-sectional study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 22(5), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.2196/19128

Filatotchev, I., & Stahl, K. (2015). Towards transnational CSR: Corporate social responsibility approaches and governance solutions for multinational corporations. Organizational Dynamics, 44, 121–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orgdyn.2015.02.006

Filimonau, V., Vi, L. H., Beer, S., & Ermolaev, V. A. (2021). The COVID-19 pandemic and food consumption at home and away: An exploratory study of English households. Socio-Economic Planning Sciences. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seps.2021.101125

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. https://doi.org/10.2307/3151312

Fozouni Ardekani, Z., Akbari, M., Pino, G., Zúñiga, M. A., & Azadi, H. (2021). Consumers’ willingness to adopt genetically modified foods. British Food Journal, 123(3), 1042–1059. https://doi.org/10.1108/BFJ-04-2019-0260

Frank, P., & Brock, C. (2018). Bridging the intention–behavior gap among organic grocery customers: The crucial role of point-of-sale information. Psychology and Marketing, 35(8), 586–602. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.21108

Galanakis, C. M., Rizou, M., Aldawoud, T. M. S., Ucak, I., & Rowan, N. J. (2021). Innovations and technology disruptions in the food sector within the COVID-19 pandemic and post-lockdown era. Trends in Food Science and Technology, 110(July 2020), 193–200. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tifs.2021.02.002

Ghaziani, S., Ghodsi, D., Dehbozorgi, G., Faghih, S., Ranjbar, Y. R., & Doluschitz, R. (2021). Comparing lab-measured and surveyed bread waste data: A possible hybrid approach to correct the underestimation of household food waste self-assessment surveys. Sustainability. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13063472

Ghaziani, S., Ghodsi, D., Schweikert, K., Dehbozorgi, G., Faghih, S., Mohabati, S., & Doluschitz, R. (2022). Household food waste quantification and cross-examining the official figures: A study on household wheat bread waste in Shiraz, Iran. Foods, 11, 1188. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods11091188

Graham-Rowe, E., Jessop, D. C., & Sparks, P. (2015). Predicting household food waste reduction using an extended theory of planned behaviour. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 101, 194–202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2015.05.020

Guidry, J. P. D., Laestadius, L. I., Vraga, E. K., Miller, C. A., Perrin, P. B., Burton, C. W., Ryan, M., Fuemmeler, B. F., & Carlyle, K. E. (2021). Willingness to get the COVID-19 vaccine with and without emergency use authorization. American Journal of Infection Control, 49(2), 137–142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajic.2020.11.018

Hanson, C. L., Crandall, A., Barnes, M. D., & Novilla, M. L. (2021). Protection motivation during COVID-19: A cross-sectional study of family health, media, and economic influences. Health Education and Behavior, 48(4), 434–445. https://doi.org/10.1177/10901981211000318

Hassen, T. B., El Bilali, H., Allahyari, M. S., Berjan, S., & Fotina, O. (2021). Food purchase and eating behavior during the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional survey of Russian adults. Appetite, 165(May), 105309. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2021.105309

Heidari, A., Mirzaii, F., Rahnama, M., & Alidoost, F. (2020). A theoretical framework for explaining the determinants of food waste reduction in residential households: A case study of Mashhad, Iran. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 27, 6774–6784. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-019-06518-8

Hobbs, J. E. (2020a). Food supply chains during the COVID-19 pandemic. Canadian Journal of Agricultural Economics, 68(2), 171–176. https://doi.org/10.1111/cjag.12237

Hobbs, J. E. (2020b). The Covid-19 pandemic and meat supply chains. Canadian Journal of Agricultural Economics. https://doi.org/10.1111/cjag.12237

Hooper, D., Coughlan, J., & Mullen, M. (2008). Structural equation modelling: Guidelines for determining model fit. Electronic Journal of Business Research Methods, 6(1), 53–60.

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

Islam, T., Pitafi, A. H., Arya, V., Wang, Y., Akhtar, N., Mubarik, S., & Xiaobei, L. (2021). Panic buying in the COVID-19 pandemic: A multi-country examination. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 59(March), 102357. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2020.102357

Jang, H. W., & Lee, S. B. (2022). Protection motivation and food waste reduction strategies. Sustainability. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14031861

Janmaimool, P. (2017). Application of protection motivation theory to investigate sustainable waste management behaviors. Sustainability, 9(7), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9071079

Jian, Y., Yu, I. Y., Yang, M. X., & Zeng, K. J. (2020). The impacts of fear and uncertainty of COVID-19 on environmental concerns, brand trust, and behavioral intentions toward green hotels. Sustainability, 12(20), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12208688

Jöreskog, K. G., & Sörbom, D. (1993). Structural equation modeling with the SIMPLIS command language.

Jöreskog, K. G., Olsson, U. H., & Wallentin, F. Y. (2016). Multivariate analysis with LISREL. Springer.

Joreskog, K. G., & Sorbom, D. A. (2006). LISREL 8.80. Scientific Software International Inc.

Jribi, S., Ben, H., Doggui, D., & Debbabi, H. (2020). COVID-19 virus outbreak lockdown: What impacts on household food wastage? Environment, Development and Sustainability, 22(5), 3939–3955. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-020-00740-y

Karandish, F., Hoekstra, A. Y., & Hogeboom, R. J. (2020). Reducing food waste and changing cropping patterns to reduce water consumption and pollution in cereal production in Iran. Journal of Hydrology, 586(December 2019), 124881. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2020.124881

Khosravani, F., Pezeshki Rad, G. R., & Farhadian, H. (2015). Analyze of component consumer behavior toward food waste in Tehran. Journal of Food Science and Technology, 13(53), 173–183.

Kim, S.-Y., & Rha, J.-Y. (2014). How consumers differently perceive about green market environments: Across different consumer groups in green attitude-behaviour dimension. International Journal of Human Ecology, 15(2), 43–57. https://doi.org/10.6115/ijhe.2014.15.2.43

Kline, R. B. (2015). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (4th ed.). The Guilford Press.

La Barbera, F., & Ajzen, I. (2020). Control interactions in the theory of planned behavior: Rethinking the role of subjective norm. Europe’s Journal of Psychology, 16(3), 401–417. https://doi.org/10.5964/ejop.v16i3.2056

Laato, S., Islam, A. K. M. N., Farooq, A., & Dhir, A. (2020a). Unusual purchasing behavior during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic: The stimulus-organism-response approach. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 57(March), 102224. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2020.102224

Laato, S., Islam, A. K. M. N., & Laine, T. H. (2020b). Did location-based games motivate players to socialize during COVID-19? Telematics and Informatics, 54(April), 101458. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2020.101458

Lahath, A., Omar, N. A., Ali, M. H., Tseng, M. L., & Yazid, Z. (2021). Exploring food waste during the COVID-19 pandemic among Malaysian consumers: The effect of social media, neuroticism, and impulse buying on food waste. Sustainable Production and Consumption, 28, 519–531. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spc.2021.06.008

Laher, S. (2016). Ostinato rigore: establishing methodological rigour in quantitative research. South African Journal of Psychology, 46(3), 316–327. https://doi.org/10.1177/0081246316649121

Lam, L. W. (2012). Impact of competitiveness on salespeople’s commitment and performance. Journal of Business Research, 65(9), 1328–1334. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2011.10.026

Lamy, E., Viegas, C., Rocha, A., Lucas, M. R., Tavares, S., Capela e Silva, F., et al. (2022). Changes in food behavior during the first lockdown of COVID-19 pandemic: A multi-country study about changes in eating habits, motivations, and food-related behaviors. Food Quality and Preference, 99(July), 104559. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2022.104559

Li, H., Cao, A., Chen, S., & Guo, L. (2022). How does risk perception of the COVID-19 pandemic affect the consumption behavior of green food? Environment, Development and Sustainability. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-022-02819-0

Lin, B., & Guan, C. (2021). Determinants of household food waste reduction intention in China: The role of perceived government control. Journal of Environmental Management, 299(January), 113577. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2021.113577

Ling, M., Kothe, E. J., & Mullan, B. A. (2019). Predicting intention to receive a seasonal influenza vaccination using Protection Motivation Theory. Social Science and Medicine, 233(May), 87–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.06.002

Liu, Z., Yang, J. Z., Clark, S. S., & Shelly, M. (2022). Recycling as a planned behavior: The moderating role of perceived behavioral control. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 24, 11011–11026. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-021-01894-z

Lourenço, C. E., Porpino, G., Araujo, M. C. L., Vieira, L. M., & Matzembacher, D. E. (2022). We need to talk about infrequent high volume household food waste: A theory of planned behaviour perspective. Sustainable Production and Consumption, 33(September), 38–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spc.2022.06.014

Luu, T. T. (2021). Can food waste behavior be managed within the B2B workplace and beyond? The roles of quality of green communication and dual mediation paths. Industrial Marketing Management, 93(June), 628–640. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2020.07.012

Marquart, F. (2017). Methodological rigor in quantitative research. In C. S. D. and R. F. P. J. Matthes (Ed.), The international encyclopedia of communication research methods. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118901731.iecrm0221

Martens, M., De Wolf, R., & De Marez, L. (2019). Investigating and comparing the predictors of the intention towards taking security measures against malware, scams and cybercrime in general. Computers in Human Behavior, 92(May 2018), 139–150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.11.002

Masotti, M., Van Der Haar, S., Janssen, A., Iori, E., Zeinstra, G., Bos-brouwers, H., & Vittuari, M. (2023). Food waste in time of COVID-19: The heterogeneous effects on consumer groups in Italy and the Netherlands. Appetite, 180(January), 106313. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2022.106313

Milne, S., Orbell, S., & Sheeran, P. (2002). Combining motivational and volitional interventions to promote exercise participation: Protection motivation theory and implementation intentions. British Journal of Health Psychology, 7, 163–184. https://doi.org/10.1348/135910702169420

Mondéjar-Jiménez, J. A., Ferrari, G., Secondi, L., & Principato, L. (2016). From the table to waste: An exploratory study on behaviour towards food waste of Spanish and Italian youths. Journal of Cleaner Production, 138, 8–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.06.018