Abstract

Background

Aquatic exercise programs can enhance health and improve functional fitness in older people, while there is limited evidence about the efficacy of aquatic-exercise programs on improving well-being and quality of life.

Aim

The purpose of this study was to determine the effects of a supervised water fitness program on subjective well-being in older women.

Methods

The study group included 166 active older women (> 65 years), divided into water-based (WFG) and land-based (CG) training groups. They filled out 3 questionnaires to assess their amount of physical activity (IPAQ), subjective well-being (PANAS) and mental and physical health status (SF-12).

Results

Results showed that subjective well-being, physical activity level, perceived mental and physical status had higher values in the WFG compared to CG.

Conclusions

We found that older women practicing water fitness tend to have a better subjective physical and mental well-being than those who exercise in a land-based context.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Aging is a biological process characterized by the progressive development, maturation and decline of the organism from birth to death [1]. In particular, aging has been associated with decreased muscle mass, and consequently, reduced muscle strength [2]. In addition, the aging process has been found negatively associated with psychological well-being (CIT), and as shown by Wassink-Vossen et al. (CIT) and Rejeski et al. (CIT), older physically inactive adults are more inclined to be depressed and to have a low quality of life.

From the other hand, PA practice and correct fitness education could play a relevant role to counteract poor biomarkers commonly associated with aging [3]. Therefore, in older adults, regular exercise practice positively alters depression symptoms, promotes mental health, influencing motor and cognitive skills that may prevent the onset of different mental illnesses and delay mental decay [4,5,6].

In fact, women who pass menopause face many changes that may lead to loss of health-related fitness [7], because menopause leads to several changes in women's body resulting the precursor of sleep disturbances, fatigue, aches and pains, altered cognitive functions and weakness of muscular system [8]. Despite this, older women could counteract short and medium-term effects of decline with regular exercise practice [9]. In particular, aerobic combined with resistance training (RT) is likely to preserve normal bodyweight, preserve bone mineral density, increase muscle strength and cardiorespiratory fitness [10]. In both the studies by Padilla Colón et al. [11] and Distefano et al. [12], exercise and PA influenced attenuated age-related decreases in muscle mass, strength, and regenerative capacity. In addition, a recent study by Brock Symons et al. (2015) demonstrated that PA practice improves muscle and movement ability, slows or prevents impairments in muscle metabolism [4].

PA carried out in a water environment allowed older people to gain all the advantages of land-based exercise reducing the impact, stress and strain on arthritic joints [13] and increasing bone density [14]. In fact, water based exercise was effective in health-related achievements as showed by Bocalini et al. with 12 weeks of exercise that improved the functional fitness outcomes and quality of life in older women [15]. Moreover, there is evidence that aquatic exercise programs can enhance the cardiovascular system output, increase muscular strength, decrease body fat, and ameliorate body balance [16]. In fact, Nikolai et al. showed that water aerobic exercises, as land-based exercises, help older adults to reach the amount of daily PA necessary to improve and maintain cardiorespiratory fitness suggested by the guidelines [17, 18]. In addition, the result obtained in the study by Da Silva et al. [19] showed that aquatic exercise programs reduce depression and anxiety, improve functional autonomy and decrease oxidative stress in depressed olders. According to a study conducted by Haynes et al. water exercises are particularly beneficial for a person with orthostatic hypertension, because pressure of the water, surrounding the body, helps to maintain normal blood pressure [20]. In addition, the warm water encourages body flexibility reducing spasticity with positive effects on the daily activities execution [13, 21]. These benefits are related to specific water physical properties that could improve physical exercise adherence or health-oriented recreation practice in the water context [22] but there is a limited knowledge of the possible effects on psychological well-being of it.

So, since a water-fitness program can improve physical fitness in older adults, but it is unclear how it influences well-being, the aim of our study was to understand if a supervised water-fitness program was able to obtain greater quality of life and/or subjective well-being in PA compared to a land-training program in active older women.

Methods

Study design and participants

A total of 211 older women (age: 72.93 ± 6.08 years) freely participated in this cross-sectional study through an online survey developed by Sports scientists on Google Form (Google LLC) in Italy. The inclusion criteria were defined as follows: age more than 65 years, being physically active, not having any history of musculoskeletal or neurologic injury, conditions, or syndromes diagnosed in the past 6 months. The exclusion criteria were chronic or metabolic diseases, orthopedic injuries in the last 6 months and the Inactive group, according to IPAQ-SF categories.

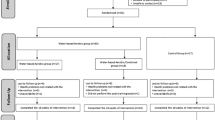

We considered only the sufficiently physically active women (Mets/sett > 600) and according to the survey responses, 82 women were identified as participating in the water fitness (WFG) and 84 women were included in the comparison group (CG). The recruiting process is summarized in the flowchart below (Fig. 1).

WFG is composed of women who perform aerobic and resistance exercises in the water environment, while the CG practiced the same exercise typology in a land-based context. Both groups participated in two training sessions per week that lasted 50 min. In particular, WFG performed a combination of running, kicks, jumps exercises in place or displacement on different planes, such as jumping jack, cross country, ski, twist, jump-tuck, jump frog, cheerleader, jump rock jump in place or displacement on different planes in water. CG performed a combination of running, kicks, jumps exercises, such as skip, behind kicks, leaps, squat jump, lounge in a land-based context. The main phase of training lasted 35 min. Both groups, prior to the training performed 10 min of warm-up consisting of mobility exercises for neck, trunk, arms pelvis and lower limbs and 5 min of stretching of the main muscular groups.

All the participants filled out the written informed consent after the explanation of the procedure of the study and they are free to withdraw from the study at any moment. The study protocol was approved by the Internal Board of University of Pavia and in accordance with the ethical procedure as described by the Declarations of Helsinki as revised in 2018. In Fig. 1, we presented a flowchart for the study design.

Questionnaires

Participants were asked to fill out three questionnaires of multiple features to assess their amount of PA through the Short-form of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ-SF), subjective well-being through the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS) and life quality related to mental and physical health status through the Short Form of health status questionnaire (SF-12). All the questionnaires were executed 1 week after the end of both group activities to avoid any possible influence.

Short-form of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ-SF)

The IPAQ-SF is a reliable and valid method to assess the amount of weekly PA in adults (Cronbach Alpha = 0.60) [23]. This questionnaire investigates 3 days and minutes spent doing specific types of activities: walking, moderate-intensity activities and vigorous-intensity activities. The purpose of this questionnaire is to provide common instruments that can be used to obtain internationally comparable data on health-related PA.

METs are a measure used to compare different types of activity based on their level of energy expenditure and they were obtained by multiplying the minutes spent during the week doing PA, obtained with the IPAQ-SF answers, with the value based on the type of activity: 3.3 for walking, 4 for moderate, and 8 for vigorous activities by Ainsworth et al. [24].

All the activities that lasted less than 10 min were not considered.

Positive and negative affect schedule (PANAS)

PANAS is a self-assessment questionnaire for measuring people's emotions, feelings and subjective well-being. It’s a list of 20-item self-reported measures of affect and each item is rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = not at all, 2 = a little, 3 = moderately, 4 = quite a bit, 5 = extremely). Positive and negative items are separately tallied to provide an overall picture of the mood. Positive and negative items range from 10 to 50 and total score is calculated by their sum. For the positive, a high score means the tendency to experience positive emotion and low score indicates a tendency to experience negative emotion. While for the negative, a high score means the tendency to experience negative emotion and low score indicates a tendency to experience positive emotion. PANAS recognize that you can feel positive and negative emotion at the same time. Positive items are indicated with odd numbers while negative are even numbers. These are two orthogonal dimensions. Scale reliability ranged between 0.86–0.90 for positive affect and 0.84–0.87 for negative affect [25].

12-item Short form Health Questionnaires (SF-12)

SF-12 is taken from the extensive version of SF-36 and it investigates the psychophysical perception and conditions of individuals. It is composed of 12 questions that cover domains of health. Scores synthesis allows to build of two health state indices: Physical Component Summary (PCS), which is about the physical state, and Mental Component Summary (MCS), which is correlated to the emotional statement. Range values are from 10,5 to 69,7 for PCS and from 7,4 to 72,1 for the MCS: high indices correspond to better psychophysical health while at low levels (≤ 20 points) indicates a condition of self-care in physical, personal and social limitations, a frequent fatigue [26].

Statistical analysis

All quantitative data were summarized as mean ± SD or median (range) as appropriate. To analyze the different levels of PA, we considered the total MET per week, the MET for walking, moderate and vigorous activities. The Shapiro–Wilk test was used to determine the assumption of data normality. To assess the differences of IPAQ-SF, PANAS and SF12 between the two groups, WFG and CG, a Welch’s T test was used. All the significance was set at a p value less than 0.05. Cohen’s d was used to estimate the size of the effect. Regarding the sample size, with a power of 0.90 and an alpha error of 0.05, we conveniently enrolled an initial sample of at least 100 women for each group [27]. Statistical analyses were performed using “The Jamovi project (2021). Jamovi Version 1.6 for Mac [Computer Software], Sydney, Australia; retrieved from https://www.jamovi.org.

Results

The final sample consists of 82 subjects in WFG (age 72.05 ± 5.47 years) and 84 in CG (age 72.90 ± 6.44 years).

Table 1 shows the differences in the PA level between the two groups.

Our results showed differences in the amount of METs per week (p < 0.001; effect size = 0.530) and the METs of Vigorous activities (p < 0.001; effect size = 0.790 between the two groups). The analysis did not show any significant differences in the METs of Moderate activities and the METs of Walking activities between the WFG and the CG.

Table 2 shows the comparison between WFG and CG groups. Our results showed that there was a difference between the self-report well-being of the two groups.

Results showed that PANAS positive outcomes have higher values in WFG compared to CG (p < 0.001; effect size = 0.990). While PANAS negative outcomes have lower values in WFG compared to CG (p < 0.001; effect size = − 0.739).

The PCS-12 was higher in WFG compared to CG (p < 0.001; effect size = 0.772) and, also, the MCS-12 was higher in the WFG compared to the CG (p < 0.001; effect size = 0.607).

Discussion

Our study aimed to investigate the effect of water-based training on self-reported PA engagement, physical and psychological well-being compared to land-based training in older women.

Our results highlight that WFG had better outcomes for physical and psychological well-being than CG, supporting the benefit of PA practice in water environment for older women. The investigation of the psychological well-being through PANAS questionnaire showed that the WFG group feels less depressed, irritable and stressed than the CG.

In accordance with our results, Yoo et al. (2020) reported mood amelioration and decreased tension after water-based exercise [28] with augmented motivation to continue the water-based training [29]. Moreover, Delevatti et al. (CIT) found a greater improvement in quality of life and sleep quality in adults with type 2 diabetes undergoing a water-based exercise intervention compared to land-based intervention.

Although a great difference in well-being, both groups showed good physical and mental well-being perceptions. As shown by several studies in decades, PA practice has wide and positive effects on mental health in older adults [30] METTERE CIT DA 32 A 37 NO36. For example, Haller et al. showed that people enrolled in an exercise intervention increased self-efficacy and reduced depressive symptoms compared to sedentary peers [31]. Moreover, Zamani et al. found an association between PA and self-esteem, quality of life and positive affect, which seems to be mediated by physical self-perception [32].

Our results highlighted also that WFG had a higher level of PA mainly due to the higher vigorous activities compared to the CG [16, 33]. This result is interesting since suggests that older people who exercise in a water-based context seem to have fewer barriers to high-intensity exercise/activities, which are not usually practiced in this age [27]. In fact, additionally, aquatic exercise allows the application of the physical stress theory for individuals who cannot tolerate the stresses of land-based exercises [20]. Water acts as a counterbalance to the force of gravity having a reduced impact on joints and these types of exercises are effective to increase older people participants physical strength, flexibility, and agility [22]. Denning et al. confirmed this, who showed that older adults that consistently exercise on an underwater treadmill improve flexibility, sleep patterns and joint pains [34]. Muscular resistance caused by the water is 12 times higher than that of the air and, therefore, during the exercises is required more work of the motor cortex [35]. This could be a possible cause that lead our WFG to report a higher level of vigorous-intensity PA and to well perceive the effort during the water-based training. Even if the PA level was assessed only through questionnaire, we aimed to evaluate the relationship between psychological outcomes and the perception of PA level in water environment. In fact, older people difficulty reaches the amount of PA recommended by the guidelines and a better/positive self-perception of own feelings about PA and well-being, as showed by our results specifically for the water environment, could play a key role in the PA engagement. Further studies are necessary to evaluate the relationship between objective and reported PA level and psychological outcomes.

We recognize that our study had some limitations. First, we did not assess older women's physical fitness contributing to a potential limitation in the real assessment of functional capacities. Moreover, since we considered only the self-perceived data, our results could be influenced by possible misperceptions.

Nevertheless, to the best of our knowledge, these are the first Italian data that investigated PA, feelings and perceptions of older women highlighting better psycho-physical well-being in water practitioners. In general, physical activity is a safe way to improve health and to promote health aging [10] as improves strength and cardiorespiratory parameters in elderly women [32]. However, physical activity in aquatic environment seems to encourage people more [15] because of weight discharge benefits [7] and sensations experienced after the practice.

In conclusion, since physical and mental condition are at the base of senior autonomy and well-being, we found that older active women practicing water fitness tend to have a better level of self-reported physical fitness and self-perception feeling better than those who exercise in a land based context. Considering the relevance of PA role in this age for health reasons, water based exercise should be promoted with adapted programs in our communities.

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Taylor D, Gill J (2012) Active ageing: live longer and prosper. University College London, p 7

Csapo R, Alegre LM (2016) Effects of resistance training with moderate vs heavy loads on muscle mass and strength in the elderly: a meta-analysis. Scand J Med Sci Sports 26(9):995–1006. https://doi.org/10.1111/sms.12536

Li L (2012) People can live longer by being physically more activity. J Sport Heal Sci 1(1):7–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jshs.2012.02.001

Brock Symons T, Swank AM (2015) Exercise testing and training strategies for healthy and frail elderly. ACSM’s Heal Fit J 19(2):32–35. https://doi.org/10.1249/FIT.0000000000000104

Rebar AL, Stanton R, Geard D, Short C, Duncan MJ, Vandelanotte C (2015) A meta-meta-analysis of the effect of physical activity on depression and anxiety in non-clinical adult populations. Health Psychol Rev 9(3):366–378. https://doi.org/10.1080/17437199.2015.1022901

Bridle C, Spanjers K, Patel S, Atherton NM, Lamb SE (2012) Effect of exercise on depression severity in older people: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Br J Psychiatry 201(3):180–185. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.111.095174

Rotstein A, Harush M, Vaisman N (2008) The effect of a water exercise program on bone density of postmenopausal women. J Sports Med Phys Fitness 48(3):352–359

Asbury EA, Chandrruangphen P, Collins P (2006) The importance of continued exercise participation in quality of life and psychological well-being in previously inactive postmenopausal women: a pilot study. Menopause 13(4):561

Aibar-Almazán A, Hita-Contreras F, Cruz-Díaz D, de la Torre-Cruz M, Jiménez-García JD, Martínez-Amat A (2019) Effects of Pilates training on sleep quality, anxiety, depression and fatigue in postmenopausal women: a randomized controlled trial. Maturitas 124:62–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2019.03.019

Chavez A, Scales R, Kling JM (2021) Promoting physical activity in older women to maximize health. Cleve Clin J Med 88(7):405–415. https://doi.org/10.3949/CCJM.88A.20170

Colón CJP et al (2018) Muscle and bone mass loss in the elderly population: advances in diagnosis and treatment. J Biomed 3(672):40–49. https://doi.org/10.7150/jbm.23390

Distefano G, Goodpaster BH (2018) Effects of exercise and aging on skeletal muscle. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. https://doi.org/10.1101/cshperspect.a029785

Simas V, Hing W, Pope R, Climstein M (2017) Effects of water-based exercise on bone health of middle-aged and older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Open Access J Sport Med 8:39–60. https://doi.org/10.2147/oajsm.s129182

Zeng CY, Zhang ZR, Tang ZM, Hua FZ (2021) Benefits and mechanisms of exercise training for knee osteoarthritis. Front Physiol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2021.794062

Bocalini DS, Serra AJ, Rica RL, dos Santos L (2010) Repercussions of training and detraining by water-based exercise on functional fitness and quality of life: a short-term follow-up in healthy older women. Clinics 65(12):1305–1309. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1807-59322010001200013

Wu ZJ, Wang ZY, Gao HE, Zhou XF, Li FH (2021) Impact of high-intensity interval training on cardiorespiratory fitness, body composition, physical fitness, and metabolic parameters in older adults: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Exp Gerontol 150(1):111345. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exger.2021.111345

Nikolai AL, Novotny BA, Bohnen CL, Schleis KM, Dalleck LC (2009) Cardiovascular and metabolic responses to water aerobics exercise in middle-age and older adults. J Phys Act Health 6(3):333–338. https://doi.org/10.1123/jpah.6.3.333

Lopez JF et al (2021) Systematic review of aquatic physical exercise programs on functional fitness in older adults. Eur J Transl Myol. https://doi.org/10.4081/EJTM.2021.10006

da Silva LA et al (2019) Effects of aquatic exercise on mental health, functional autonomy and oxidative stress in depressed elderly individuals: a randomized clinical trial. Clinics 74:1–7. https://doi.org/10.6061/clinics/2019/e322

Haynes A et al (2020) Land-walking vs. water-walking interventions in older adults: Effects on aerobic fitness. J Sport Heal Sci 9(3):274–282. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jshs.2019.11.005

McPhee JS, French DP, Jackson D, Nazroo J, Pendleton N, Degens H (2016) Physical activity in older age: perspectives for healthy ageing and frailty. Biogerontology 17(3):567–580. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10522-016-9641-0

Santos CC, Barbosa TM, Costa MJ (2020) Biomechanical responses to water fitness programmes: a narrative review. Motricidade 16(3):305–315. https://doi.org/10.6063/motricidade.20052

Biernat E, Stupnicki R, Lebiedziński B, Janczewska L (2008) Assessment of physical activity by applying IPAQ questionnaire. Phys Educ Sport 52:46–52. https://doi.org/10.2478/v10030-008-0019-1

Ainsworth BE et al (2000) Compendium of physical activities: an update of activity codes and MET intensities. Med Sci Sports Exerc 32(9 Suppl):S498-504. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005768-200009001-00009

Vera-Villarroel P et al (2019) Positive and negative affect schedule (PANAS): psychometric properties and discriminative capacity in several chilean samples. Eval Heal Prof 42(4):473–497. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163278717745344

Ware JE, Kosinski M, Keller SD (1996) A 12-item short-form health survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care 34(3):220

Neiva HP, Faíl LB, Izquierdo M, Marques MC, Marinho DA (2018) The effect of 12 weeks of water-aerobics on health status and physical fitness: an ecological approach. PLoS ONE 13(5):1–15. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0198319

Yoo JH (2020) The psychological effects of water-based exercise in older adults: an integrative review. Geriatr Nurs (Minneap) 41(6):717–723. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gerinurse.2020.04.019

Katsura Y et al (2010) Effects of aquatic exercise training using water-resistance equipment in elderly. Eur J Appl Physiol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00421-009-1306-0

Miller KJ, Mesagno C, McLaren S, Grace F, Yates M, Gomez R (2019) Exercise, mood, self-efficacy, and social support as predictors of depressive symptoms in older adults: direct and interaction effects. Front Psychol 10:1–11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02145

Haller N et al (2019) Individualized web-based exercise for the treatment of depression: randomized controlled trial. JMIR Ment Health 5(4):698. https://doi.org/10.2196/10698

Farinha C et al (2021) Impact of different aquatic exercise programs on body composition, functional fitness and cognitive function of non-institutionalized elderly adults: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Environ Res Public Health. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18178963

Vandoni M, Codrons E, Marin L, Correale L, Bigliassi M, Buzzachera CF (2016) Psychophysiological responses to group exercise training sessions: does exercise intensity matter? PLoS ONE 11(8):e0149997. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0149997

Denning W, Bressel E, Dolny D (2010) Underwater treadmill exercise as a potential treatment for adults with osteoarthritis. Int J Aquat Res Educ. https://doi.org/10.25035/ijare.04.01.09

Ochoa Martínez P, Hall-López J, Meza EI, Díaz D, Dantas E (2014) Effect of 3-month water-exercise program on body composition in elderly women. Int J Morphol 32:1248–1253. https://doi.org/10.4067/S0717-95022014000400020

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi di Pavia within the CRUI-CARE Agreement.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, M.D.B, L.B., E.L. and L.C.; methodology, M.D.B, M.V., V.C.P. and N.L.; software, A.G.; formal analysis, A.G. and A.P.; investigation, V.C.P., E.L. and F.B., data curation, A.G., M.V., A.P. and V.C.P.; writing—original draft preparation, M.V., V.C.P., A.G. and A.P.; writing— review and editing, N.L., M.V and M.D.B.; visualization, M.D.B.; supervision, M.V and N.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The author declares no conflict of interest, financial or otherwise.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Internal board of University of Pavia and all participants gave a written informed consent.

Human and animal rights

No animals were used for studies that are the basis of this research. This research was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2013 (http://ethics.iit.edu/ecodes/node/3931).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Del Bianco, M., Lovecchio, N., Pirazzi, A. et al. Self-reported physical activity level, emotions, feelings and self-perception of older active women: is the water-based exercise a better enhancer of psychophysical condition?. Sport Sci Health 19, 1311–1317 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11332-023-01094-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11332-023-01094-4