Abstract

Purpose

Treatment of patients with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) using mandibular advancement appliances enhances the airway and may be an alternative to continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) in individuals with reduced adherence to CPAP therapy. The effectiveness as well as improved patient compliance associated with these appliances may improve the quality of life in patients with OSA. The aim of this systematic review of studies was to determine the improvement in quality of life amongst patients with OSA who were treated with an oral appliance.

Methods

The research study was registered on the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO: CRD42021193386). A search was carried out using the search engines Google Scholar, PubMed, Ovid, Cochrane Trial Registry, and LILACS. Patients with OSA treated with oral appliance therapy to advance the mandible were studied. Twenty-five studies were identified through the literature search and all had varying control groups for assessment of quality of life. Seventeen studies were included for the quantitative synthesis.

Results

QoL, evaluated by the Functional Outcomes of Sleep Questionnaire (FOSQ), significantly improved in patients treated with oral appliance therapy. There was a mean difference of 1.8 points between the baseline scores and the scores following treatment with an oral appliance.

Conclusion

Overall, a significant improvement in the QoL was observed with the Functional Outcomes of Sleep Questionnaire, following oral appliance therapy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Sleep plays a vital role in maintaining good health and well-being throughout life. Quality of sleep helps protect mental health and physical health and thus the quality of life [1]. Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is characterized by repetitive collapse of the upper airway during sleep. The upper airway comprises the nose, the nasopharynx, the retropalatal oropharynx, the hypopharynx, and the larynx. The muscles that control the upper airway or the pharyngeal airway also play a role in swallowing and speech. These muscles can be categorized into muscles that control the shape and position of the tongue and palate, muscles that influence the position of the hyoid bone, and pharyngeal constrictor muscles. They are in turn activated by respiratory stimuli such as a decrease in oxygen levels and an increase in levels of carbon dioxide. During sleep, however, there is a decrease in the responsiveness of the muscles, which then makes the pharyngeal airway more vulnerable to collapse [2].

Approximately 3 to 7% of adult men and 2 to 5% of adult women are affected by OSA [3]. Findings of narrow airway or reports of heavy snoring are possibly indicative of respiratory pattern abnormalities causing arousals during sleep. OSA can be of particular significance to the dental surgeon as observation of the oropharyngeal structures forms an important part of routine oral examination [4, 8].

While the primary role of an orthodontist is not to diagnose OSA, an opportunity for screening exists. In patients with OSA, orthodontic therapy forms part of the multidisciplinary approach in treatment [5]. This is because orthodontists have the knowledge of facial growth along with an understanding of oral devices. A patient with OSA may be referred by a physician if an oral appliance or any other orthopedic/orthodontic adjunctive therapy has been prescribed. Oral appliances for OSA are mandibular advancement appliances or tongue retaining devices. Oral appliances may be used in the treatment of mild to moderate OSA and also in patients who have severe OSA, but are unwilling to use the CPAP (continuous positive airway pressure). These appliances work by holding the mandible and the associated tissues forward, thereby increasing the caliber of the upper airway [6].

Schwartz et al. concluded that even though CPAP was significantly more efficient in reducing Apnea–Hypopnea Index (AHI) (with a moderate quality of evidence), compliance was lower with CPAP, with no differences between Mandibular Advancement Appliance (MAA) and CPAP in terms of cognitive or functional outcomes [7]. Ferguson et al., through a short-term controlled trial, showed that MAA was associated with greater patient satisfaction than CPAP [8]. Johnston et al. showed that based on the reduction of the AHI and the oxygen-desaturation index (ODI), the success rate of the MAA was 33 and 35%, respectively [9].

In recent times, the measurement of patient centered outcomes has gained precedence over outcomes that measure other aspects of successful treatment. Recommendations by health agencies such as the World Health Organization (WHO) suggest that quality of life measures should be included in clinical studies. Research on quality of life (QoL) has increased in the last few decades [10]. QoL is defined by the WHO as “individuals’ perceptions of their position in life in the context of the culture and value systems in which they live and in relation to their goals, expectations, standards and concerns” [11].

Malocclusion is known to be associated with facial and dental appearance-related self-concept issues [10]. While it is only fair to expect that orthodontic treatment should result in enhanced self-esteem and improved QoL, the evidence is highly conflicting as a result of differences in design, tools for assessment, and populations. Patients with OSA have impaired HRQL (health-related quality of life) when compared to healthy age- and gender-matched controls [12].

Several studies have assessed the changes in the quality of life (QoL) of patients treated with (Mandibular Advancement Device) MAD [20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44]. A few have been described in a literature review on the efficacy of oral appliances for the treatment of OSA by Sutherland et al. [13]. Some show significant improvement in QoL across all parameters used for assessment, some showing improvement in specific domains, and while others not showing any significant improvement at all.

In a systematic review by Kuhn et al., the quality of life of patients treated with both CPAP and mandibular appliances was assessed. However, the outcome measured was restricted to general health-related quality of life (HRQL) and did not include sleep specific changes in quality of life [14].

Therefore, this review aimed to determine the improvement in quality of life amongst patients with OSA who were treated with an oral appliance.

Materials and method

This systematic review was conducted and reported in accordance with the PRISMA guidelines (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta analyses). The proposal was registered on the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO: CRD42021193386).

A search was carried out using online databases — Google Scholar, PubMed, Ovid, LILACS, and the Cochrane Trial Registry. The following criteria were used to assess eligibility.

Inclusion criteria

-

1.

Studies that have assessed the quality of life of patients with OSA treated with an MAA/MAD

-

2.

Studies that have assessed the quality of life using valid questionnaires

-

3.

Full-length articles

-

4.

Study design: experimental studies, randomized and non-randomized studies, observational studies, cross-sectional studies, case–control studies, and cohort studies

-

5.

All published data, until March 3rd, 2021, in the English language

Exclusion criteria

-

1.

Studies that assessed the quality of life of patients who were given continuous positive airway pressure alone or other appliances, other than the mandibular repositioning splint

-

2.

Studies that have not assessed QoL using valid questionnaires

-

3.

Foreign language articles

-

4.

Unpublished articles

-

5.

Case reports and case series

-

6.

Studies without a valid statistical analysis

Information sources

Online database searched with Google Scholar, Cochrane Trial Registry, PubMed, LILACS, and Ovid.

Search strategy

The keywords used were “obstructive sleep apnea,” “quality of life,” “health-related quality of life,” “oral appliance,” “mandibular advancement appliance,” and “apnea” (Table 1).

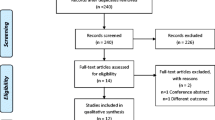

A total of 2680 articles were obtained, from which 1411 were removed as duplicates using automation tools. A total of 1269 titles were screened; 33 full-text articles were retrieved. Out of the 33 articles, 8 were excluded for various reasons. Twenty-five studies were selected for inclusion in this systematic review (Fig. 1).

Data were collected and analyzed independently by two reviewers. These data sets were then examined by a third reviewer in order to reach a common consensus. Automation tools used were the Zotero reference manager software for the removal of duplicates.

Data outcomes and variables

The primary outcomes sought were total QoL scores at baseline and total scores following oral appliance therapy, evaluated using the FOSQ (Functional Outcomes of Sleep Questionnaire) [15], the Mental and Physical Components of the SF-36 (Short Form-36) questionnaire [16], and the Sleep Apnea Quality of Life Index (SAQLI) [17].

Data variables were patient demographics, AHI (Apnea–Hypopnea Index) at baseline, control groups, and appliance characteristics.

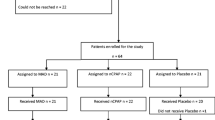

Risk of bias

Risk of bias for the randomized studies was assessed using the Cochrane tool, which has been represented using a traffic signal plot (Fig. 2). The risk of bias for the non-randomized studies was calculated using the ROBINS-1 tool (Table 2) [18, 19].

Data extraction and analysis

Data extraction was done by a single author and verified independently by two authors. RevMan 5.4.1 was used for data analyses. A random-effects model was employed to present the continuous data as a mean difference with a confidence interval of 95%. Heterogeneity was detected using the chi-squared test as well as I2 statistics.

Result

Study selection

The database search resulted in a total of 2410 articles, out of which 25 were included in this systematic review [20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44].

Study characteristics

The study characteristics obtained were patient demographics, baseline AHI score, appliance description, quality of life questionnaire, and control/comparison groups. Fourteen out of the 25 studies were randomized studies. The sample size ranged from 11 to 158. All participants in the studies were 18 years old and above (Table 3). The most common control/comparison was the continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) (Table 4).

Quality assessment

The quality for these studies was assessed using the Cochrane tool for randomized and the ROBINS-1 tool for non-randomized studies. A high risk of bias was observed in four studies.

Results of individual studies

Out of twenty-five studies, 11 studies had reported the total scores at baseline and post-appliance therapy from the FOSQ. One study reported the mean scores and another, the median, with the interquartile range. Amongst the studies that had used the SF-36 questionnaire, 5 reported Physical Component Scores (SF-36 PC) from the SF-36 questionnaire and 6 had reported the total Mental Component Scores (SF-36 MC). Three studies reported total scores from the SAQLI (Table 5).

Use of a single questionnaire

Six out of 25 studies used the FOSQ alone to evaluate changes in quality of life, and a significant improvement was reported by 4. Eight studies used only the SF-36, of which 6 did not show significant improvement and 2 studies used a single SAQLI to evaluate QoL changes. Both studies reported significant QoL changes.

Combined questionnaires

The remaining nine studies used a combination of questionnaires. Out of 9 studies, seven had combined SF-36 and FOSQ and one had combined SF-36 with SAQLI 6; Six amongst these, showed a significant improvement in quality of life.

Individual domains

The SF-36 questionnaire has 8 individual domains. In the study by Lam et al. [26], there was a significant improvement in the “general health,” “vitality,” and “role-emotional” domains. In the study by Johal et al. [25], significant differences in the “vitality” and “physical role limitation” domains were observed. In 5 studies, there was no significant improvement in SF-36 scores.

Three studies had reported the total scores from the SAQLI. Machado et al. had used the Calgary SAQLI and reported important minimum difference (IMD) between pre-treatment and post-treatment quality of life. All participants had shown small to excellent improvement.

Meta-analysis

Seventeen studies were included in the quantitative synthesis. A statistically significant improvement in quality of life was seen only with the FOSQ (Fig. 3a) with a mean difference of 1.8 between the baseline and the post-treatment scores. The mean differences for the SF-36 PC, SF-36 MC, and SAQLI scores were 0.4, 3.11, and 1.43, respectively. This was not statistically significant (Fig. 3 b,c and d).

Discussion collected and analyzed independently by two reviewers

This review demonstrateed significant improvement in QoL, measured using sleep-specific questionnaires, following oral appliance therapy. QoL enables orthodontists to look at treatment from the patient’s perspective and evaluate whether the treatment rendered provides a holistic improvement in their lives. Mandibular appliances (MAA/MAD) have been pegged by orthodontists for treatment of OSA, owing to the reduced patient compliance exhibited by the CPAP.

Previous systematic reviews show that mandibular appliances are effective in treating mild to moderate OSA [45]. QoL changes following oral appliance therapy can be explained by various factors — objective reduction in the number of apneic events, appliance design, construction, characteristics, and subjective daytime sleepiness.

Apnea–Hypopnea Index

Improvement in QoL is likely to be associated with improvement in disease symptoms. An objective way to assess this is through polysomnographic measurements such as AHI.

In the study by Hoekema et al., no significant QoL change was observed [27]. This is possibly because of the severity of disease in the participants, represented by a baseline AHI of 39.4 ± 30.8.

In all except 4 studies, where this outcome was not mentioned, there was a significant reduction in AHI following oral appliance therapy.

In one study, by Ruiter et al. [44], it was demonstrated that there was no correlation between AHI scores and quality of life. In another study by Bhushan et al. [39], AHI had a mild inverse correlation with QoL scores.

Questionnaires

Another factor that determined improvement in the studies was the specificity of the questionnaire.

Each questionnaire has domains, pertaining to the various aspects of QoL. The domains, the number of questions, the type of questions, and the scoring system vary from one questionnaire to another. The FOSQ was developed by Weaver et al., in 1997, and was the first self-report measure for assessing the impact of sleepiness on quality of life [15]. Therefore, it is a questionnaire that specifically targets OSA patients. Another sleep-specific questionnaire, SAQLI, was also used in the studies.

The SF-36 questionnaire is a generalized questionnaire. It contains 36 items, which assess 8 health concepts [16], including physical function, role-physical, bodily pain, general health, vitality, social function, mental health, and role-emotional.

Two studies that had used only the FOSQ did not show a significant change in quality of life. The study by Ruiter et al. [44] was a 2-year follow-up of the study by Benoist et al. [40]. The authors had pitted the sleep position trainer against the oral appliance. Both studies had a high dropout rate. One-third of the patients had been lost to follow-up. The authors believe that this was because of a delay in patient intake due to change in the location of appliance fitting, which might have caused reduced patient commitment. While the quality of life mildly improved, no clinically significant value was obtained [40, 44].

With the general SF-36 questionnaire, some domains showed a significant improvement, while others did not. Vitality was seen to significantly improve in 4 studies [25, 26, 36, 43]. Vitality represents energy level and fatigue. It comprises 4 questions [16].

Combining questionnaires is justified in order obtain a sleep specific as well as a general perspective. In the study by Blanco et al. [23], the FOSQ questionnaire was used along with SF-36 for evaluation. It is possible that the specificity of the FOSQ questionnaire to OSA patients could have caused a difference in the scores of the two questionnaires. One study by Quinnell et al. [36] also included EuroQoL to calculate quality-adjusted life years (QALY).

Appliance design

Extent of advancement

An oral appliance works by repositioning the mandible in an increased vertical or open position. It also holds the mandible in a forward position relative to the maxilla and improves airway patency. This is done by increasing pharyngeal volume and/or by improving muscles tone to reduce airway collapsibility [1,2,3].

The therapeutic window for mandibular advancement is typically in the 50–75% range of the maximum mandibular protrusion [2]. The advancement also depends on the severity of the disease [45]. A titration approach involves gradual increments of advancement with time, which was followed by nineteen out of twenty-five studies in the current review.

Adjustability

The appliance should be adjustable and so that it can be modified to fit new dental restorations and be relined for better retention. Another characteristic feature of the appliance is that it should cover the teeth fully in order to prevent tooth movement or unwanted supraeruption and maintain teeth in the pre-treatment position [1,2,3]. In the study by Engleman et al. [20], two mandibular appliances with variations in extent of occlusal coverage were compared. One had less coverage than the other. Both the appliances showed an improvement in quality of life with no significant difference between the two.

Fabrication of the appliance

In terms of fabrication, the appliances can either be customized or thermoplastic. Two studies in this review, one by Gagnadoux et al. [41] and the other by Quinell et al. [36], have compared custom made and thermoplastic devices. In the study by Gagnadoux et al., thermoplastic appliances were associated with increased tooth pain, self-reported occlusal changes, and decreased compliance. In both studies, however, there was no difference in quality of life scores between the two appliances [36, 41]. An improvement was seen from baseline with both appliances. Customized appliances are made by registering the patient’s bite, whereas thermoplastic appliances are fabricated by placing the heated material in the patient’s mouth and asking them to bite on it in an ideally advanced position. The thermoplastic appliances are a less expensive and less time consuming alternative to customized appliances [40, 44]. A randomized crossover trial found a lower rate of treatment success and lower patient adherence associated with thermoplastic appliances. A majority of patients had preferred the customized appliance. The lower rates of adherence were attributed to insufficient retention of thermoplastic appliances during sleep [47].

The extent of vertical opening with the appliances was mentioned in 5 studies. In two of these studies, a 5-mm vertical opening was employed. In the studies by Lam et al. and Aarab et al., the extent was based on the patient’s comfort [26, 31]. Lawton et al. had compared two types of mandibular appliances — one that was similar to the Herbst appliance and the other that was designed like the Twin Block appliance. The height of the wax bite for the Twin Block group was 2–3 mm greater than for the Herbst group. The authors found that with the Twin Block group, there was lesser prevalence of muscular and temporomandibular joint discomfort and they attributed this to the downward rotation of the mandible as it came forward, relieving the pressure on the muscles of mastication and the temporomandibular joint [24]. Increased vertical opening can possibly increase the collapsibility of the pharyngeal airway [46], but there is evidence that points to no effect on treatment success [47].

Appliance side effects

The various side effects of using oral appliances are possible reasons for the lack of a significant improvement in quality of life scores. These include excessive salivation, muscle pain, temporomandibular disorders, changes in occlusion, and a dry mouth on waking up. The other disadvantages include loosening of the appliance with a lack of soft tissue adaptation. An increase in age can result in reduced muscular tone of the genioglossus muscle resulting in poor retention of these appliances [23, 24].

Patient compliance

While compliance was assessed subjectively by either maintaining a diary, or through assessment of efficacy, only one study [40] objectively evaluated compliance using a temperature sensitive micro-chip which was embedded on to the oral appliance and assessed over a period of 100 days. The percentage of compliance was found to be 60.5%.

Daytime sleepiness

Amongst the various subjective symptoms, daytime sleepiness was found to be significantly improved following oral appliance therapy in majority of the studies. The Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS) was used for evaluation of the same [49].

Limitations

A large clinical diversity was present amongst the studies observed in terms of the type of appliance, control/comparison group, duration of appliance wear, and severity of the disease. Despite low risk of bias scores, 10 studies did not perform randomization. Amongst the randomized controlled trials, 8 had low risk of bias, while in the other studies, the risk of bias was either unclear or high.

Conclusion

-

Overall, a significant improvement in the quality-of-life was observed with the Functional Outcomes of Sleep Questionnaire, following oral appliance therapy.

-

High-quality randomized studies that make use of sleep-specific questionnaires to evaluate QoL are needed.

-

Further research is required to identify the correlation between disease severity, subjective day time sleepiness, compliance, and QoL.

References

Vanarsdall RL (1994) Orthodontics: current principles and techniques. CV Mosby

White DP, Younes MK (2012) Obstructive sleep apnoea, Comprehensive Physiology

Garvey JF, Pengo MF, Drakatos P, Kent BD (2015) Epidemiological aspects of obstructive sleep apnea. J Thorac Dis 7(5):920–929

Attanasio R, Bailey DR (2009) Dental management of sleep disorders. John Wiley & Sons

Rangarajan V (2019) Sleep-related disorders and its relevance in dental practice. Journal of Interdisciplinary Dentistry 9(2):49

Behrents RG, Shelgikar AV, Conley RS, Flores-Mir C, Hans M, Levine M, ..., Hittner J (2019). Obstructive sleep apnea and orthodontics: an American Association of Orthodontists White Paper. American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics, 156(1), 13-28

Schwartz M, Acosta L, Hung YL, Padilla M, Enciso R (2018) Effects of CPAP and mandibular advancement device treatment in obstructive sleep apnea patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep and Breathing 22(3):555–568

Ferguson KA, Ono T, Lowe AA, Al-Majed S, Love LL, Fleetham JA (1997) A short-term controlled trial of an adjustable oral appliance for the treatment of mild to moderate obstructive sleep apnoea. Thorax 52(4):362–368

Johnston CD, Gleadhill IC, Cinnamond MJ, Gabbey J, Burden DJ (2002) Mandibular advancement appliances and obstructive sleep apnoea: a randomized clinical trial. The European Journal of Orthodontics 24(3):251–262

Cunningham SJ, O’Brien C (2007) Quality of life and orthodontics. In Seminars in Orthodontics (Vol. 13, No. 2, pp. 96–103). WB Saunders

World Health Organization. The world health organization quality of life (WHOQOL)-BREF. No. WHO/HIS/HSI Rev. 2012.02. World Health Organization, 2004

Moyer CA, Sonnad SS, Garetz SL, Helman JI, Chervin RD (2001) Quality of life in obstructive sleep apnea: a systematic review of the literature. Sleep Med 2(6):477–491

Sutherland K, Vanderveken OM, Tsuda H, Marklund M, Gagnadoux F, Kushida CA, Cistulli PA (2014) Oral appliance treatment for obstructive sleep apnea: an update. J Clin Sleep Med 10(2):215–227

Kuhn E, Schwarz EI, Bratton DJ, Rossi VA, Kohler M (2017) Effects of CPAP and mandibular advancement devices on health-related quality of life in OSA: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Chest 151(4):786–794

Weaver TE, Laizner AM, Evans LK, Maislin G, Chugh DK, Lyon K, ..., Dinges DE (1997) An instrument to measure functional status outcomes for disorders of excessive sleepiness. Sleep: 20(10): 835-843

Ware JE Jr, Sherbourne CD (1992) The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). Medical care 473:483

Flemons WW, Reimer MA (2002) Measurement properties of the Calgary sleep apnea quality of life index. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 165(2):159–164

ROBINS-I (2016) a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomized studies of interventions BMJ 355; i4919

Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, Jüni P, Moher D, Oxman AD et al (2011) BMJ 343:d5928

Engleman HM, McDonald JP, Graham D et al (2002) Randomized crossover trial of two treatments for sleep apnea/hypopnea syndrome: continuous positive airway pressure and mandibular repositioning splint. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 166(6):855–859

Barnes M, McEvoy RD, Banks S, Tarquinio N, Murray CG, Vowles N, Pierce RJ (2004) Efficacy of positive airway pressure and oral appliance in mild to moderate obstructive sleep apnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 170(6):656–664

Machado MAC, Prado LBFD, Carvalho LBCD, Francisco S, Silva ABD, Atallah ÁN, Prado GFD (2004) Quality of life of patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome treated with an intraoral mandibular repositioner. Arq Neuropsiquiatr 62(2a):222–225

Blanco J, Zamarron C, Pazos MA, Lamela C, Quintanilla DS (2005) Prospective evaluation of an oral appliance in the treatment of obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Sleep and Breathing 9(1):20–25

Lawton HM, Battagel JM, Kotecha B (2005) A comparison of the Twin Block and Herbst mandibular advancement splints in the treatment of patients with obstructive sleep apnoea: a prospective study. The European Journal of Orthodontics 27(1):82–90

Johal A (2006) Health-related quality of life in patients with sleep-disordered breathing: effect of mandibular advancement appliances. J Prosthet Dent 96(4):298–302

Lam B, Sam K, Mok WY, Cheung MT, Fong DY, Lam JC, ..., Mary SM (2007) Randomised study of three non-surgical treatments in mild to moderate obstructive sleep apnoea. Thorax 62(4): 354-359

Hoekema A, Stegenga B, Wijkstra PJ, Van der Hoeven JH, Meinesz AF, De Bont LG (2008 Sep) Obstructive sleep apnea therapy. J Dent Res 87(9):882–887

Petri N, Svanholt P, Solow B, Wildschiødtz G, Winkel P (2008) Mandibular advancement appliance for obstructive sleep apnoea: results of a randomised placebo controlled trial using parallel group design. J Sleep Res 17(2):221–229

Vecchierini MF, Leger D, Laaban JP, Putterman G, Figueredo M, Levy J, ..., Philip P (2008) Efficacy and compliance of mandibular repositioning device in obstructive sleep apnea syndrome under a patient-driven protocol of care. Sleep medicine 9(7): 762-769

Gauthier L, Laberge L, Beaudry M, Laforte M, Rompré PH, Lavigne GJ (2009) Efficacy of two mandibular advancement appliances in the management of snoring and mild-moderate sleep apnea: a cross-over randomized study. Sleep Med 10(3):329–336

Aarab G, Lobbezoo F, Hamburger HL, Naeije M (2011) Oral appliance therapy versus nasal continuous positive airway pressure in obstructive sleep apnea: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Respiration 81(5):411–419

Gauthier L, Laberge L, Beaudry M, Laforte M, Rompré PH, Lavigne GJ (2011) Mandibular advancement appliances remain effective in lowering respiratory disturbance index for 2.5–4.5 years. Sleep medicine 12(9):844–849

Phillips CL, Grunstein RR, Darendeliler MA, Mihailidou AS, Srinivasan VK, Yee BJ, ..., Cistulli PA (2013) Health outcomes of continuous positive airway pressure versus oral appliance treatment for obstructive sleep apnea: a randomized controlled trial. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine 187(8): 879-887

Schütz TCB, Cunha TCA, Moura-Guimaraes T, Luz GP, Ackel-D'Elia C, Alves, EDS, ..., Bittencourt L (2013) Comparison of the effects of continuous positive airway pressure, oral appliance and exercise training in obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Clinics 68: 1168-1174

Doff MH, Hoekema A, Wijkstra PJ, van der Hoeven JH, Huddleston Slater JJ, de Bont LG, Stegenga B (2013) Oral appliance versus continuous positive airway pressure in obstructive sleep apnea syndrome: a 2-year follow-up. Sleep 36(9):1289–1296

Quinnell TG, Bennett M, Jordan J, Clutterbuck-James AL, Davies MG, Smith, IE, ..., Sharples LD (2014) A crossover randomised controlled trial of oral mandibular advancement devices for obstructive sleep apnoea-hypopnoea (TOMADO). Thorax, 69(10), 938-945

Banhiran W, Kittiphumwong P, Assanasen P, Chongkolwatana C, Metheetrairut C (2014) Adjustable thermoplastic mandibular advancement device for obstructive sleep apnea: outcomes and practicability. Laryngoscope 124(10):2427–2432

Marklund M, Carlberg B, Forsgren L, Olsson T, Stenlund H, Franklin KA (2015) Oral appliance therapy in patients with daytime sleepiness and snoring or mild to moderate sleep apnea: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med 175(8):1278–1285

Bhushan A, Tripathi A, Gupta A, Tripathi S (2015) The effects of an oral appliance in obstructive sleep apnea patients with prehypertension. J Dent Sleep Med 2:37–43

Benoist L, de Ruiter M, de Lange J, de Vries N (2017) A randomized, controlled trial of positional therapy versus oral appliance therapy for position-dependent sleep apnea. Sleep Med 34:109–117

Gagnadoux F, Nguyen XL, Le Vaillant M, Priou P, Meslier N, Eberlein A, ..., Launois S (2017) Comparison of titrable thermoplastic versus custom-made mandibular advancement device for the treatment of obstructive sleep apnoea. Respiratory medicine 131: 35-42

Cunha TC, Guimaraes TD, Schultz TC, Almeida FR, Cunha TM, Simamoto Junior PC, Bittencourt LR (2017) Predictors of success for mandibular repositioning appliance in obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Brazilian Oral Research 31

Fernández-Julián E, Pérez-Carbonell T, Marco R, Pellicer V, Rodriguez-Borja E, Marco J (2018) Impact of an oral appliance on obstructive sleep apnea severity, quality of life, and biomarkers. Laryngoscope 128(7):1720–1726

de Ruiter MH, Benoist LB, de Vries N, de Lange J (2018) Durability of treatment effects of the Sleep Position Trainer versus oral appliance therapy in positional OSA: 12-month follow-up of a randomized controlled trial. Sleep and Breathing 22(2):441–450

Ahrens A, McGrath C, Hägg U (2010) Subjective efficacy of oral appliance design features in the management of obstructive sleep apnea: a systematic review. Am J Orthod Dentofac Orthop 138(5):559–576

Vroegop AV, Vanderveken OM, Van de Heyning PH, Braem (MJ, (2012) Effects of vertical opening on pharyngeal dimensions in patients with obstructive sleep apnoea. Sleep Med 13(3):314–316

Pitsis AJ, Darendeliler MA, Gotsopoulos H, Petocz P, Cistulli PA (2002) Effect of vertical dimension on efficacy of oral appliance therapy in obstructive sleep apnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 166:860–864

Vanderveken OM, Devolder A, Marklund M, Boudewyns AN, Braem MJ, Okkerse W, Verbraecken JA, Franklin KA, De Backer WA, Van de Heyning PH (2008) Comparison of a custom-made and a thermoplastic oral appliance for the treatment of mild sleep apnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 178:197–202

Johns MW (1991) A new method for measuring daytime sleepiness: the Epworth sleepiness scale. Sleep 14(6):540–545

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

The article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Comment

The measurement of quality of life (QoF) is an important aspect in the evaluation of oral appliance treatment for OSA, compared with CPAP, UPPP, and other treatments. This systematic review is more patient-centered and provides more valuable results for clinicians.

Yanyan Ma.

Beijing, China.

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Oral Appliance Therapy

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Rangarajan, H., Padmanabhan, S., Ranganathan, S. et al. Impact of oral appliance therapy on quality of life (QoL) in patients with obstructive sleep apnea — a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Breath 26, 983–996 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11325-021-02483-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11325-021-02483-0