Abstract

This research examines the problems of public participation in conserving a Ramsar site at the Tana Delta in southeastern Kenya. Given no participation of the public in government initiatives so far, we attempted to find out what had prevented local people from cooperating with responsible government bodies. Using empirical evidence that we obtained from fieldworks, questionnaire surveys, and workshops, we found that the low participation was not mainly due to local people’s unwillingness to conserve natural resources. Instead, we found that they were strongly interested in wetland resources conservation as long as their customary rights to governing resources are sufficiently recognized. We also documented how these local people managed their resources. The Kenya Wildlife Service and the National Museum of Kenya are the main government bodies to promote public participation, but we found that these agencies had not done effective communication works among local people. Our survey then clarified what sources of information can be most effective in communicating with local people in the Tana Delta. Finally, we discuss how the problems of public participation can be solved or reduced.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The Rio Declaration (UNCED 1992a) and Agenda 21 (UNCED 1992b) call for the active involvement of local society in fostering sustainable development. In Europe, these efforts have set a pretext for the development of the Aarhus Convention that affirms the rights of access to justice and information as well as public participation in decision-making on environmental issues (Aarhus Convention 1998). Globally, many international leaders have advocated for public participation in natural resources management and conservation (Cent et al. 2014; Danielsen et al. 2014; Fry 2011). Partly as a result of these continuous framework-making efforts, local people in general have become increasingly engaged in environmental policy and decision-making processes. Local people are also gradually involved more in scientific research and monitoring as citizen scientists (Shirk et al. 2012).

However, a question remains about the extent to which local people are convinced about the importance of wetland conservation. In another words, what are the problem areas to be addressed if local people are to be more effectively mobilized, or what are the factors that prevent or promote public participation? Reed et al. (2009) contends that stakeholders’ identification and selection are conducted on an ad hoc basis, possibly neglecting key local participants and compromising intended objectives. This likely happens especially in multilateral environmental agreement (MEA) negotiations in the international arena. For instance, lack of public participation in the formulation of millennium development goals (MGDs) impeded their effective implementation (Wisor 2016).

The Ramsar Convention recognizes that participatory environmental management is critical to ensure the sustainable use and management of wetlands (Resolution VIII.36). Understanding the need to raise public awareness about wetlands and their functions, and to encourage local stewardship, the Ramsar Convention signatories, including Kenya, adopted the communication, capacity building, education, participation and awareness (CEPA) programme in 1999 (Resolution VII.9). The CEPA programme was renewed in 2002, 2008, and 2015. The most recent and on-going program for 2016–2024 attempts to incorporate cultural sensitivity by encouraging “participation in wetland management of stakeholder groups with cultural, spiritual, customary, traditional, historical and socio-economic links to wetlands.” It emphasizes that implementing parties give high priority to those communities who depend on wetlands for their livelihoods. It also urges local communities and private sectors to participate in the management of wetlands (Resolution XII.9).

The implementation and degree of public participation, however, vary by regions and localities. Also, what prevents government officials from effectively reaching out to local communities and establishing cooperative awareness programs differ widely by regions partly reflecting regional socio-economic backgrounds as well as tribal or traditional norms about conservation. In Kenya’s Tana Delta, which was relatively recently designated as the Ramsar site, local people have not participated in the CEPA programme yet. They have little knowledge about the Ramsar Convention. This study, therefore, examines how the local people at the Tana Delta see wetland conservation. Our research shows that despite their little participation in CEPA, most local people are willing to participate in wetland conservation. We argue that local people at the Delta are willing as long as they are there to stay and maintain some governance power over resource use.

In the following discussion, we first describe about social, economic and geographic backgrounds of our focus area and people. Then we discuss the results of our questionnaire survey, interviews, and workshops in the area. The results mainly attempt to show local people’s perceptions and awareness. In the following section for discussion, we clarify some of difficult conditions for local participation. Finally, we attempt to identify how these challenges can be possibly overcome, considering local circumstances.

Study area

The Tana River Delta is located at 02° 30′S 040° 20′E in Tana River and Lamu Counties, Kenya (Fig. 1) (UNESCO 2010). The Delta is characterized by low and erratic bimodal rainfalls. The average annual rainfall ranges between 300 and 900 mm. The average temperature and humidity are 30 °C and 85%, respectively (Odhengo et al. 2014). The Delta covers approximately 163,000 ha, consisting of crucial estuarine and deltaic ecosystems such as biologically diverse mangrove forests (UNESCO 2010).

Source Ramsar (2012)

Map of Tana River Ramsar site.

In 2012, the Tana Delta was designated as a Ramsar site. It has also been classified as an Important Bird and Biodiversity Area (Ramsar 2012). The fluctuating salinity at the mouth of the Tana River, the Kipini region, supports the growth of snails that feed approximately 1500 birds daily. It is also home to a number of bird species, including the endangered Malindi pipit, Basra reed warbler, eastern red colobus and Tana crested mangabey. The Delta provides habitat to such mammals as elephants, lions, hippos and wild dogs (Birdlife International 2017). About 71 forest patches covering approximately 3700 ha are found there (UNESCO 2010).

The study area is divided into sub-counties. Each sub-county is sparsely populated (Munguti and Matiku 2015) and roughly 93% of its population lives in rural areas (Odhengo et al. 2014). According to the 2009 population census, the Tana Delta sub-county is home to 85,823 (Kenya Bureau of Statistics 2009). Three major ethnic communities, the Pokomo (44%), the Orma (44%) and the Wardei (8%) live in this sub-county (Odhengo et al. 2014). The Pokomo are mainly farmers. The Orma and the Wardei are nomadic pastoralists. There have been conflicts between farmers and pastoralists over land use and ownership (Karanja and Saito 2017).

Both farmers and pastoralists depend on resources in the Delta. It is estimated that more than a million head of cattle graze in the Delta (Munguti and Matiku 2015). The Kipini region is rich in biodiversity but vulnerable to floods. The main economic activities there are crop cultivation, livestock grazing and fishing (Karanja and Saito 2017). The Delta also supports local fresh water supplies and tourism (Birdlife International 2017). Despite its rich resources, about 76% of people suffer from poverty (Munguti and Matiku 2015).

There are limited infrastructures in these villages. The road is overall narrow, unpaved and unreliable during the heavy rainy season. Motorcycle taxi, bicycles and walking are the main means of transportation. There is no hospital, clinic or a drug store in Kau, Kilelengwani, Kibauni, and Kilunguni villages. Prior to 2012 a health dispensary had existed in Kau. It was destroyed during the 2012 Tana Delta clashes. There is only one health dispensary in Kipini town. Additionally, all the primary and secondary schools are located in Kipini (Karanja 2015).

The local communities tend to perceive outside influence, such as national and foreign development programs, as threat to the Delta and their livelihoods. For instance, conservationists and local residents view the ongoing Tana Delta irrigation project, which encompasses 40,000 ha of this area, as a threat to ecological stability (Birdlife International 2017; The East African 2012). In 2013, local leaders requested for the termination of this project. They claimed that the constructed rubber dams would obstruct the normal river flow hence increasing the probability of flood intensity during the rainy seasons (The Star 2013). When the Kenyan government issued the license for a Canadian company to use 64,000 ha of the Delta for a jatropha biofuel plantation, residents strongly opposed and filed a petition against it via Nature Kenya. Eventually, the plan was revoked as the project was suspected to leading to deforestation, water shortage, food insecurity, soil erosion, rare species loss, and the displacement of local people from their ancestral lands (Nature Kenya 2012).

Methodology

The field data for this study was partly derived from our unpublished project that originally aimed at estimating the economic value of the Tana Delta wetlands (Ramsar site), and how local people perceive and understand them. In this paper we dwell on the second objective of this project. We tried to understand how local people interpret and respond to government-led conservation initiatives through the Ramsar CEPA programme. This paper uses the data collected in five villages: Kau, Kilelengwani, Kibauni, Kilunguni and Kipini.

The data collection included field observations, interviews, a questionnaire survey, workshop, and document content analyses. The field data were collected in the period between November 2014 and January 2015. Before conducting the questionnaire surveys, a two-day preliminary field study was conducted to make sure that all the questions were understandable within the local context.

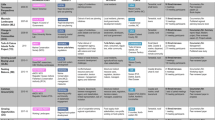

After this preliminary study, the revised questionnaire was distributed to 90 households through stratified random sampling (Table 1). Each village represented a stratum. The questionnaire focused on two sets of questions. The first set sought to determine people’s perceptions about the importance of the Tana Delta. To understand their value systems in using resources in the Tana River Delta, they were asked to identify three most important values they hold about the Delta. The questions also tried to understand factors that motivate or impede local people’s participation in the conservation initiatives.

The second set of questions attempted to assess local people’s awareness about the Ramsar designation of the Delta. It also attempted to identify the extent to which those local people had been engaged in Ramsar’s CEPA programme. The respondents were asked to list training and/or awareness campaigns they attended pertaining to the sustainable use of wetlands as well as three preferred sources of information about wetland conservation. They also ranked trustability of several information sources by 1–5 scale, where 1 represented lowest trust and five highest trust.

In separate occasions, interviews were also conducted at Kipini town in December 2014 with two Kenya Wildlife Service experts (Ramsar national administrative authority), some representatives of the Tana River County government, and the Kipini Forest Conservation and Management Forum. These interviews aimed at understanding local initiatives that were undertaken to create public awareness and training about the Ramsar Convention and wetland conservation.

To further understand the local participation in the CEPA programme and their perceptions about the Ramsar designation, one-day public workshop was organized at Kilelengwani in December 2014. This was made possible by kind collaboration from a Kilelengwani youth leader, village elders, an area chief, and the Kipini forest conservation and management forum (a community based organization). Twenty-eight volunteers (13 males and 15 females) from the five villages participated in the workshop.

In writing this paper, the collected data in the field were supplemented with document content analysis. We also incorporated our field observation in our analysis. The collected data were coded and analyzed by using STATA.

One limitation of our research was that the data collection was hampered by insecurity in the area. In most areas we were accompanied by police officers in remote areas. We cannot deny that the police presence possibly influenced the responses of the participants, but in order to guarantee the confidentiality and neutrality, the questionnaire was administered in respondents’ houses without the presence of police officers who remained outside.

Results and discussion

Socio-demographic features

The first part of our survey clarified socio-demographic characteristics of the lower Tana Delta community. As Table 2 shows, the majority or 66% of the respondents were in the age range from 20 to 39. About 24% of the respondents had no formal education, but 52% had received primary education. The main economic activities were crop cultivation (76%), businesses (23%), fishing (19%) and livestock keeping (17%). Most of these businesses sold food products and household goods. Most common service businesses included small restaurants and boda boda (motorcycle taxis). Some respondents practiced more than one economic activity to diversify their income sources.

In our fieldwork, we learned that there was no well-established market for the above occupations in Kipini, which was the main shopping location for local people. Our informants told us that poor road networks and insecurity in Tana River and Lamu counties had hampered the accessibility of goods produced and/or harvested in the lower Tana Delta. For instance, only two public buses provide the public transportation from Kipini to the Garsen region, each makes one round trip daily. About 79% of the surveyed households had a maximum monthly income of US$100. The fish in Kipini town was three times cheaper compared to those in Mpeketoni, the nearest coastal town in Lamu County.

Perception about Tana Delta wetland

The second part of the questionnaire survey aimed to understand local people’s perceptions about wetland conservation and their connection to local resources for livelihood sustenance. About 97% of the respondents perceived the Tana Delta to be extremely beneficial to their daily lives, and 3% found it somewhat beneficial. Wetlands as a breeding ground for fish (mangroves), as a supporting place for the water cycle, and as a source of firewood, were the three most valued ecosystem services identified by the respondents (Fig. 2). Based on the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (MA) classification (Duraiappah et al. 2005), 50% of the responses appreciated/valued provisioning services, 28% regulating services, 11% supporting services, and 11% cultural services. Reasonably, the local residents appreciated and understood the overall importance of the coastal wetland partly because coastal terrestrial ecosystems, especially mangrove forests, are the main source of fuel to the local people. In this area, therefore, harvesting mangrove forests for domestic use is permitted although mangrove harvests for such commercial purposes as charcoal production are prohibited (Karanja and Saito 2017).

Public participation in wetland conservation

The third part of the survey attempted to clarify the issues behind local participation in wetland conservation. Our survey results showed that all the respondents had been engaged in and were willing to participate in the restoration and conservation of the Tana Delta initiatives led by the local representatives. About 27% asked for monetary incentives to actively participate in the government-led conservation activities. This point does not suggest that these local people had not done much conservation activities in the past. On the contrary, they had practiced their traditional governance for years.

From our discussion with local people, we learned that for years the local communities in the Tana Delta had already developed and observed rules to protect coastal ecosystems. For instance, deforestation for commercial purposes had long been prohibited in the area. The local residents had monitored and regulated activities that were against the rules. Violations are to be reported to the area chief or the authority. Upon receiving the report, the chief consults with village elders and then decides the form of punishment to the violators. In case a violation is against the national law, the matter is referred to the police or forest officers. Most of conservation governance is organized or conducted at a village or household level. Some sacred areas are to be strictly preserved. Farmers and herders do not to encroach these areas where they find particularly rich in biodiversity.

Our questionnaire survey similarly showed that village elders, chiefs, and religious leaders have maintained significant control over various affairs in their respective communities. Under their commands, 86% of the respondents had directly or indirectly participated in the protection of the coastal wetland, particularly mangroves management.

This survey also revealed main reasons behind people’s participation in conservation activities. The respondents wanted to protect the Tana River environment (24%), curb deforestation (21%), avoid tribal clashes (18%), conserve wildlife (14%), minimize human-wildlife conflict (11%), protect bird species (10%), and secure monetary gains (2%).

Given local people’s high willingness to participate, our next question was why the CEPA programme has not been implemented in the Tana Delta. Our fieldwork revealed that the main reason behind this lack of participation was largely because of the historically engraved suspicion among local people about government-led initiatives. The results of the questionnaire showed local people’ suspicion was largely due to the corruption of government officials, ineffective communication and information sharing methods, and failure to consider community’s opinions.

In our workshop, corruption was identified as one of important limiting factors to establish cooperation between government and local people. For example, some participants lamented that forest officers unlawfully issued logging permits to lumberjacks to log in locally prohibited areas. This incident violated local rules and intensified distrust against forest officers. Also, interviews with Kenya Wildlife Service personnel indicated that insufficient financial resource, inadequate planning, and diverse (and often competing) communal interests (e.g., herding, agriculture) had limited public participation in the Delta. Furthermore, local leaders were not properly informed about the programme even though they were willing to incorporate new ideas as long as they were convinced about their usefulness.

Public awareness about Ramsar designation

As the Ramsar Convention emphasizes the importance of public participation in wetland management with respect to local customs, the fourth part of our survey attempted to understand the extent to which local people in the Tana Delta knew about the designation of the Delta as the Ramsar site and its implications, including the availability of the CEPA programme. The result shows that only six persons (e.g., civil servants, investors in the tourism industry, and community-based organization officials) knew of the Tana Delta having been designated as Ramsar site. However, they were uninformed about the Ramsar Convention principles and mandate. None of the respondents knew about the CEPA programme. Since the designation of the Delta in 2012, no respondent had attended training or awareness campaigns. Only about 7% of the respondents knew about the Kenya Wildlife Service as the national focal point of the Ramsar Convention. About 9% of the respondents stated that the Kenya Forest Service was in charge of implementing the Ramsar Convention. All the respondents were not aware that the National Museum of Kenya was the focal point for implementing the CEPA programme.

The workshop we organized at Kilelengwani similarly revealed that local people had not been informed about the Ramsar designation. None of the participants had attended, heard about or invited to a CEPA awareness or training campaign. The local leaders and officials of the Kipini Forest Management and Conservation Forum, who attended the workshop, expressed their fears of being relocated or prevented from freely using the land for farming and/or grazing. This misunderstanding or concern reflected the fact that about 76% of the participants did not have the title deeds for the land. Without the proof of land ownership, they felt they would be hardly compensated in case some development plan comes to their neighborhood.

Nevertheless, the participants of the workshop showed great interests in participating in wetland conservation activities. Some of the workshop members said they had volunteered for some mangrove conservation initiatives organized by the Kipini Forest Management and Conservation Forum.

One related concern was how to build better trust relationships between these local people and government authorities. The workshop participants said that they had been excluded from making decisions about the coastal ecosystems that they had depended on. They appeared to be overall suspicious about government led conservation initiatives, including the CEPA programme.

In our interviews two Kenya Wildlife Service officials confirmed that local communities in the Tana Delta had not participated in the designation process and Ramsar related training activities or workshops. Nonetheless, these officials emphasized the need for public participation. Previously they had actively engaged with the local communities of the Delta in addressing human-wildlife conflicts and tribal clashes, but they said that there was no plan or discussion about the implementation of the CEPA programme. For them, public awareness campaigns were tedious and time-consuming. In fact, the Kenya Wildlife Service is short of manpower to send its trained personnel to the Tana Delta regularly. There is no branch office in the Tana Delta to properly facilitate public participation.

Public participation and public awareness

Then the question arises as to how these officials can time/cost effectively reach local people and disseminate important information about Ramsar principles among local people. For this, it is essential to know how these local people receive and trust information. In the final part of our survey, therefore, we asked the respondents to rank their three most preferred sources of information regarding the Tana Delta wetland conservation. The result showed that the radio was the most preferred source of information (36%), followed by public events (27%) and religious institutions (21%) (Fig. 3). Written materials, newspapers and magazines (1%) and brochures and pamphlets (2%) were the least preferred sources of information.

The participants also ranked the trust level of each sources of information from 1 to 5 (5 as the highest and 1 as the lowest trust levels). The result showed that about 75% of the respondents ranked information from religious institutions (churches and mosques) as the most trustable with the trust level of 5. About 62% found brochures and pamphlets with the trust level of 5. The radio (67%), television (65%), and newspaper and magazines (60%) were rated with the trust level of 4. Nearly half (48%) of the respondents found public gatherings/events as moderately trustable or trust level 3. Roughly 42% of the respondents listed social media with the low trust level of 2. Whatsapp and Facebook were the most famous social media among them. This result suggests possibilities of exploring less time-consuming and inexpensive communication tools for the Kenya Wildlife Service and other relevant stakeholders to communicate about the importance of public participation in wetland conservation.

Regarding public awareness tools, in our interviews with Kenya Wildlife Service officials and other agents we found that in 2013, the National Museums of Kenya, in collaboration with the Kenya Wildlife Service, launched CEPA tools to educate the public about the Ramsar sites. These tools focused on biodiversity, socio-economic importance, challenges and conservation efforts of five Ramsar sites in Kenya: Lake Nakuru, Laku Naivasha, Lake Elmenteita, Lake Bogoria and Lake Baringo. The information was disseminated through posters, brochures and a video documentary, which, according to our survey result, are some of the most trusted sources of information (Terer and Macharia 2013). However, these were the least preferred sources of information among our respondents.

Discussion

Although Kenya launched CEPA tools in 2013 to enhance public awareness about Ramsar sites (Terer and Macharia 2013), the programme is yet to be implemented in the study area. The majority of the respondents had no knowledge about Ramsar designation and/or the CEPA programme. Even those six people who knew about the designation had no idea about the role and expectations of the Ramsar Convention. Nonetheless, despite their limited knowledge about Ramsar Convention, they had a deeper understanding of wetlands values and a high willingness to conserve them.

These results show what needs to be done to promote public participation in the Tana Delta. The reason behind the absence of awareness at the Delta can partly be attributed to a gap between target groups’ needs and policy implementation capacity and strategy. The main respondents in our study area mostly needed to enhance their survivability by sustainably using natural resources in the Tana Delta. They wanted to maintain their customary governance practices under existing local authorities. They were not ready to consider the option for stopping their economic activities unless there are some alternative options. As long as the Kenya Wildlife Service and the National Museum sufficiently acknowledge and properly respect local protocols, dialogues and cooperation can be established more effectively.

In so doing, our research result on trustable information sources for local people may help enhance public awareness and understanding about wetland conservation. That most of our respondents tend to rely on religious organizations and radio programs for getting information means that the Kenya Wildlife Service and the National Museum do not need a substantial workforce reinforcement and financial investment. The Museum, for example, may connect Tana Delta locals to its social media sites. Or the Kenya Wildlife Service and the National Museum can send information to radio stations and religious organizations these locals trust. The pamphlets and brochures, such as the ones the National Museum printed in the past, can be distributed to churches and posted on their bulletin boards as long as those are written in both Swahili and English.

Given the history of the Ramsar implementation in other parts of Kenya, one may argue that the public participation conditions can possibly be improved in time. Similar awareness assessment studies that were conducted at Kenya’s three other older Ramsar sites in 2013 showed that about 88% of respondents knew about Ramsar designation at the Lake Naivasha area, whereas 50% of those at the Lake Elmenteita area and 61% of those at Lake Bogoria knew of the designation (Terer and Macharia 2013). The Tana Delta site was designated relatively recently compared to Lake Bogoria (2001), Lake Naivasha (2005), and Lake Elmenteita (2005) (Ramsar 2014).

However, in considering further about effective public participation, we may also delve into the meaning and spirit of interactive participation, which was defined by levels of public participation in the CEPA programme (Resolution XII.9, appendix 1). We believe that interactive participation is suitable and more compatible at the Tana River Delta since the respondents demonstrated strong willingness to participate more in the community led conservation initiatives, including decision-making. Interactive participation will utilize local knowledge and experiences to promote sustainable use of wetlands. It is also likely to build community’s ownership and commitment (Resolution XII.9). Additionally, interactive participation will help in rebuilding trust and reducing the current suspicion about government led conservation initiatives.

In case local people want to participate in the CEPA programme and Ramsar wetland conservation in general, it is important to know which government agency provides information about training programs. For example, none of our respondents knew that the National Museums of Kenya is responsible for implementing the CEPA programme partly because the National Museums of Kenya does not have an office in the study area. Or at least local people should know where they can get information about training programs or other livelihood related opportunities.

The establishment of effective dialogues and local participation may lead to win–win outcomes by incorporating what local people can offer. Local governance and local people’s in-depth knowledge about the Tana Delta ecosystems can be of great service to wetland protection. In this process, the CEPA programme will achieve more cooperation from local people if it tends to support local livelihoods. For instance, firewood was the main source of fuels for cooking (Karanja and Saito 2017). The Tana River is pivotal for crop cultivation for residents at Kipini, Kau and Kilunguni villages. During the dry season, the delta is essential for livestock keepers. In allowing these activities, some studies may be conducted to understand the carrying capacity of the wetland ecosystem in the Delta.

We argue, overall, that public awareness and education, which CEPA promotes, can help eliminate the current misconceptions about the Ramsar designation. This is particularly true in the lower Tana River area, where most people are not yet sufficiently informed to trust the importance of the CEPA programme for local livelihoods. Local people do not yet see the importance of cooperating with the Kenya Wildlife Service or CEPA implementors without establishing effective dialogues that discuss the future outlook of collaboration between government authorities and local authorities. In so doing, it is necessary to clarify the access and benefit sharing (ABS), potential business opportunities (e.g., ecotourism options), and the recognition of local autonomy or local empowerment. Moreover, active public participation in the Tana River wetland conservation can provide an opportunity for local authorities to adopt the notions of accountability, transparency, and trust in governing local resources sustainably. Finally, government officials may consider the work for promoting public participation as a long-term investment for building capacity among local people.

Conclusion

Our research has shown that the Tana Delta Ramsar site has a good potential to produce a successful case in interactive participation in wetland conservation. The residents of the lower Tana Delta demonstrated strong willingness to participate and govern their environment. This attitude was partly attributed to their high appreciation and understanding of wetland’s economic and cultural values. They already have time-tested governance rules, instructing people about where to harvest and where to save. The Kenya Wildlife Service and the National Museums of Kenya have relatively inexpensive option to undertake the CEPA programme as long as they understand what sources of information to be used and how information can be communicated. Also, better understanding of local needs at the Tana Delta may help the authorities to find a pinpoint administration of budget to buttress community initiatives.

References

Aarhus Convention (1998) Convention on access of information, Public Participation in decision-making and access to justice in environmental matters. June 25, Denmark. http://ec.europa.eu/environment/aarhus/

Birdlife International (2017) Tana Delta, Kenya. http://www.birdlife.org/africa/policy/tana-delta-kenya. Accessed 27 March 2017

Cent J, Grodzi M, Pietrzyk-kaszy A (2014) Emerging multilevel environmental governance—a case of public participation in Poland. J Nat Conserv 22:93–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnc.2013.09.005

Danielsen F, Pirhofer-Walzl K, Adrian TP, Kapijimpanga DR, Burgess ND, Jensen PM, Madsen J (2014) Linking public participation in scientific research to the indicators and needs of international environmental agreements. Conserv Lett 7(1):12–24. https://doi.org/10.1111/conl.12024

Duraiappah AK, Naeem S, Agardy T, Ash NJ, Cooper HD, Díaz S, Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (2005) Ecosystems and human well-being: synthesis, vol 5. Island Press, Washington. https://doi.org/10.1196/annals.1439.003

Fry PB (2011) Community forest monitoring in REDD+: the “M” in MRV? Environ Sci Policy 14(2):181–187. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2010.12.004

Karanja JM (2015) The role mangrove ecosystem in flood risk reduction: the case study of Tana Delta, Kenya. Master’s thesis. United Nations University. Tokyo, Japan

Karanja JM, Saito O (2017) Cost-benefit analysis of mangrove ecosystems in flood risk reduction: a case study of the Tana Delta Kenya. Sustain Sci. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-017-0427-3

Kenya Bureau of Statistics (2009) 2009 Population and Housing Census. Kenya Bureau of Statistics (KNBS). http://www.knbs.or.ke/index.php?option=com_phocadownload&view=categories&Itemid=599. Accessed 10 June 2016

Munguti S, Matiku P (2015) Tana River Delta. Lessons learnt from Nature Kenya Work 2007–2014. Published by Nature Kenya- the Easr Africa Natural History Society. ISBN 9966-761-25-X

Nature Kenya (2012) Guided by Science, Kenyan authority rejects the case for jatropha at Dakatcha IBA. February 24. http://www.birdlife.org/worldwide/news/guided-science-kenyan-authority-rejects-case-jatropha-dakatcha-iba. Accessed 27 March 2017

Odhengo P, Matiku P, Nyangena J, Wahome K, Opaa B, Munguti S, Koyier G, Nelson P, Mnyamwezi E (2014) Tana river delta strategic environmental assessment 2014. Published by the Tana River and Lamu County governments

Ramsar (2012) The Tana River Delta Ramsar site. http://www.ramsar.org/tana-river-delta-ramsar-site Accessed 8 October 2016

Ramsar (2014) Annotated list of wetlands of international importance: Kenya Ramsar sites information service. https://rsis.ramsar.org/sites/default/files/rsiswp_search/exports/Ramsar-Sites-annotated-summary-Kenya.pdf?1492407043

Reed MS, Graves A, Dandy N, Posthumus H, Hubacek K, Morris J, Stringer LC (2009) Who’s in and why? A typology of stakeholder analysis methods for natural resource management. J Environ Manage 90(5):1933–1949. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2009.01.001

Resolution VII.9. The Convention’s Outreach Programme 1999–2002. 7th Meeting of the Conference of the Parties to the Convention on Wetlands (Ramsar, Iran, 1971). San José, Costa Rica, 10–18 May 1999. http://www.ramsar.org/sites/default/files/documents/library/key_res_vii.09e.pdf

Resolution VIII.36. Participatory environmental management (PEM) as a tool for management and wise use of wetlands. 8th Meeting of the Conference of the Contracting Parties to the Wetlands Convention (Ramsar, Iran, 1971) Valencia, Spain, 18–26 November 2002. http://www.ramsar.org/sites/default/files/documents/pdf/res/key_res_viii_36_e.pdf

Resolution XII.9. The Ramsar Convention’s Programme on communication, capacity building, education, participation and awareness (CEPA) 2016–2024. 12th Meeting of the Conference of the Parties to the Convention on Wetlands (Ramsar, Iran, 1971). Punta del Este, Uruguay, 1–9 June 2015. http://www.ramsar.org/sites/default/files/documents/library/cop12_res09_cepa_e_0.pdf

Shirk J, Ballard H, Wilderman C, Phillips T, Wiggins A, Jordan R, Bonney R (2012) Public participation in scientific research: a framework for deliberate design. Ecol Soc 17(2):29. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-04705-170229

Terer T, Macharia J (2013) Home-grown communication, education, public participation and awareness (CEPA) wetland tools: a new dawn for CEPA activities in Kenya By, (November), 0–40. http://www.ramsar.org/sites/default/files/documents/library/nationalworkshop_26112013_proceedings.pdf

The East Africa (2012) In Tana communities resist 40,000 ha project: October 13. http://www.theeastafrican.co.ke/news/In-Tana-communities-resist-40000ha-project/2558-1532640-q2o6kpz/index.html. Accessed 27 March 2017

The Star (2013) Tana Delta leaders want irrigation project stopped: May 4. http://allafrica.com/stories/201305060280.html. Accessed 4 May 2017

UNCED (1992a) Rio Declaration—Rio Declaration on Environment and Development—United Nations Environment Programme. Unep.Org. Retrieved from http://www.unep.org/Documents.Multilingual/Default.Print.asp?DocumentID=78&ArticleID=1163&l=en

UNCED (1992b) Earth Summit‘92. The UN Conference on Environment and Development. Reproduction, Rio de Jan (June), 351. http://doi.org/10.1007/s11671-008-9208-3

UNESCO (2010). The Tana Delta and forests complex. http://whc.unesco.org/en/tentativelists/5514/. Accessed 8 Oct 2016

Wisor S (2016) After the MDGs: citizen deliberation and the post-development framework, 113–133

Funding

The authors solely funded the research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Karanja, J.M., Matsui, K. & Saito, O. Problems of public participation in the Ramsar CEPA programme at the Tana Delta, Kenya. Wetlands Ecol Manage 26, 525–535 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11273-017-9589-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11273-017-9589-0