Abstract

Inclusive education is a major challenge for educational systems. In order to better understand the background to teachers’ attitudes toward inclusive education and given that personal values underlie and support attitudes, this research seeks to investigate the link between these two constructs. We tested this relationship in two pre-registered studies in which 326 (Study 1) and 527 teachers (Study 2) completed scales on attitudes, values (Studies 1 and 2), and social desirability (Study 2). Our statistical analyses partially support our hypotheses. Thus, self-transcendence and openness to change were positively related to teachers’ attitudes toward inclusive education (Studies 1 and 2), while results regarding self-enhancement were mixed (i.e., related in Study 1 but not in Study 2). Conservation values were not related to teachers’ attitudes toward inclusive education. Although these results require further development, notably regarding causality, they provide a new framework for understanding teachers’ attitudes and open up new perspectives for training teacher in order to enhance the implementation of inclusive school policies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

In 1994, the international community promoted inclusive education with the declaration that all students should learn together “regardless of individual differences or difficulty” (UNESCO, 1994, p. ix). Since then, this willingness to “ensure inclusive and equitable quality education” (UNESCO, 2016, p. 22) for all has been consistently reaffirmed. However, despite a large number of tools and laws to support inclusive education, numerous factors are known to influence its full implementation, and many psychosocial barriers remain (Ferguson, 2008; Meijer, 2010). One of the most significant is teachers’ attitudes toward inclusive education (Avramidis & Norwich, 2002; de Boer et al., 2011). The term “attitudes” refers to “a psychological tendency that is expressed by evaluating a particular entity with some degree of favor or disfavor” (Eagly & Chaiken, 1993, p. 1). Considering that attitudes contribute to the prediction of behavioral intentions (MacFarlane & Woolfson, 2013) and have an influence upon associated behavior (Girandola & Joule, 2013), it is highly likely that teachers who hold positive attitudes toward inclusive education may be more predisposed to implementing good practices toward students with Special Educational Needs (SEN), that is, students with disabilities and/or learning problems that make it more difficult for them to learn than other students of the same age, thereby making their inclusion a success (Sharma & Sokal, 2016).

A growing body of literature suggests that attitudes toward inclusive education are linked to a wide variety of factors. Some of them are contextual (e.g., a country’s educational policy, Savolainen et al., 2012) while others are more personal (e.g., individual’s socio-political ideology, Brandes & Crowson, 2009). In this paper, we seek to investigate the hypothesis that teachers’ attitudes toward inclusive education may also be related to their personal values.

The term “values” refers to what is important to each person (Schwartz et al., 2012). Values reflect human motivations and can influence choices (Schwartz, 1992). As we explain in the following sections, we hypothesized that some personal values held by teachers may be related to their attitudes toward inclusive education.

1.1 Inclusive education and teachers’ attitudes

Inclusive schools strive to offer a qualitative education to all students and contribute to shaping a fully integrative society, responding to individuals’ needs, fighting discriminatory attitudes, and building welcoming communities (UNESCO, 1994). From this perspective, inclusive schools receive and integrate all students in mainstream classrooms, regardless of their special educational needs. This implies that the teaching curricula will be adapted to the needs of such students, but also that teachers’ practices will adapt, so that all students can achieve relevant knowledge, skills and competencies (UNESCO, 2016).

Several professional dilemmas continue to prevail, which have an impact on the optimum implementation of inclusive school (Frangieh & Weisser, 2013). Although teachers may be clearly aware of the potential benefits of a fully inclusive school, discrepancies persist between what teachers identify as being requested of them—in terms of student inclusion—and what they consider to be morally worthy, and what appears to them to be conceivable or even possible in the teaching context (de Boer et al., 2011; Moberg & Savolainen, 2003). As a result, although some teachers may genuinely agree with the philosophy of inclusive education (Avramidis & Norwich, 2002; McGhie-Richmond et al., 2013), they may be reluctant to include students with SEN in their own classrooms (deBettencourt, 1999; Ward et al., 1994). Consequently, they tend to express neutral or even negative attitudes toward inclusive education (de Boer et al., 2011), creating a barrier to the success of inclusive policies (de Boer et al., 2011; MacFarlane & Woolfson, 2013).

Three categories of factors influence these attitudes: context, students’ characteristics, and teachers’ characteristics. Regarding the context, previous studies have shown that the cultural and historical context influences attitudes toward inclusive education. The way a community handles inclusive education is influenced by the practices it inherits (i.e., the community’s habits in terms of support for or placement of SEN students, Moberg et al., 2019; Savolainen et al., 2012). Regarding students’ characteristics, the type of disability they have appears to be of great importance since, for example, those with cognitive disorders or autism spectrum disorders are perceived as being more difficult to include in mainstream education than those with a motor disability (Jury et al., 2021). Finally, attitudes toward inclusive education also depend on certain personal characteristics of the teachers themselves, such as their gender (i.e., women have more favorable attitudes toward inclusive education than men, Alghazo & Naggar Gaad, 2004; Avramidis et al., 2000), age and teaching experience (i.e., younger teachers or those with fewer years of experience are more positive with regards to inclusive education, Avramidis et al., 2000), or self-efficacy (i.e., teachers who are confident about their teaching abilities are more favorable toward inclusive education, Desombre et al., 2019). Here, we argue that the degree to which teachers are favorable or unfavorable toward inclusive education may also be linked to their willingness to behave in a certain way, which is expressed through their personal values.

1.2 Personal values and attitudes

Values are abstract ideals and are an expression of human motivations guiding people throughout their lives (Maio, 2010; Schwartz, 1992) that partly reflects the moral obligation they have to behave in a certain way (Arieli et al., 2014). According to Schwartz et al. (2012), values can be summed up as four higher-order values.Footnote 1 More precisely, ‘self-transcendence’ values emphasize the overriding of one’s own interests for the sake of others. ‘Openness to change’ values emphasize independence of thought, action, and willingness to change. ‘Self-enhancement’ values emphasize pursuing one’s own interests (in terms of achievement and power), while ‘conservation’ values refer to order, self-restriction and the status quo (Table 1).

Personal values influence the choices we make (Feather, 1992), the actions we take and the intentions we implement (Gollwitzer, 1999). Additionally, they are involved in the processes by which attitudes are formed (Ajzen & Fishbein, 1977; Olson & Maio, 2003; Schwartz, 2006) and participate toward the individual’s social adaptation by contributing to the evaluation and prescription of behaviors (Chataigné & Guimond, 2014; Ogay, 2004). Some authors even assume that values cause attitudes. Rokeach (1973) notably argued that every manipulation that puts a specific value forth has a significant effect on the assigned attitude. Values could thus be linked to different attitudes (Kristiansen & Zanna, 1988; Rokeach, 1973) and conversely, attitudes could be linked to different values. As a result, and as explained in more detail below, it could be hypothesized that some personal values may embrace the values advocated for inclusive education and may partially explain some teachers’ support for inclusive education, while other values would have the opposite effect.

1.3 Teachers’ personal values and inclusive education values

Values are a form of commitment that dictates conduct in accordance with the individual’s own vision of education (Dufour & Berkey, 1995). Teachers’ personal values have been measured and are mainly situated in the self-transcendence and conservation higher-order values (Ros et al., 1999). On the one hand, this means that teachers mostly value other people’s well-being, which is consistent with the intrinsic altruistic nature of the teaching profession. On the other hand, teachers also value the preservation of the status quo and order. How can these values align with those subtly promoted by inclusive education? As suggested above, the aim of establishing an inclusive school is to give “everyone an equal opportunity” (UNESCO, 2016, p. 23), which highlights the value of equity (Gutman, 2004) and embodies a strong social justice perspective (Moran, 2007; Prud’homme et al., 2017). In other words, inclusive education requires a less discriminatory and more welcoming school that addresses a diverse range of students, without any rejection on the basis of any criterion (Prud’homme, 2011; Thomazet, 2006; UNESCO, 2016).

As a result, inclusive school conveys and promotes ideas of tolerance, universality, kindness, and benevolence which are values that clearly fit with Schwartz’s self-transcendence values (Boer & Fischer, 2013; Schwartz, 1992). Readiness for change, expressed by teachers in favor of the implementation of inclusive education, (i.e., those who are willing to make any changes required to their practices), can also be cross-referenced with the motivations carried by the higher-order value of openness to change. At the same time, since inclusive education can increase the challenges and difficulties that teachers face (e.g., adjusting the curriculum to accommodate multiple needs), this might pose a threat to their professional identity (e.g., teachers often express low belief in self-efficacy to collaborate successfully in inclusive settings, Savolainen et al., 2012). As a result, for teachers who endorse self-enhancement values, inclusive education might represent a barrier that may lead them to endorse negative attitudes. In the same vein, the full implementation of inclusive education implies changes in teachers’ practices and habits, as well as a break with the past philosophy regarding the education of students with SEN (Plaisance, 2010; Vislie, 2003), clearly contravening the idea of the status quo embodied in conservation values.

Given these suggested congruencies between inclusive education and personal values (Boer & Fischer, 2013; Verplanken & Holland, 2002), we chose to examine whether personal values could be related to teachers’ attitudes toward inclusive education. Based on the literature and the rationale described above, we hypothesize that the values of self-transcendence and openness to change should be positively correlated with teachers’ attitudes toward inclusive education, while self-enhancement and conservation values should be negatively correlated with it.

In order to test these hypotheses, two correlational studies were conducted.Footnote 2

2 Study 1

2.1 Method

2.1.1 Participants

As indicated in the pre-registration form (available https://aspredicted.org/4bz6q.pdf), the correlational nature of the study as well as the scarcity of documentation regarding the magnitude of the hypothesized effects led us to that a sample size of 250 participants would be enough to detect small- to medium-sized effects with a confidence level of 80% (see Schönbrodt & Perugini, 2013). As a consequence, teachers from various parts of France were sent an email invitation to complete our questionnaire during the spring term of the 2018–2019 school year. Participants were contacted through various national teachers’ associations, professional social networks and teacher training centers (i.e., Institut National Supérieur du Professorat et de l’Education) as well as through various local and regional education authorities. After one month of data collection, 354 teachers had completed the study, although 17 had not completed the sociodemographic section and were removed from the final sample which ultimately included 326 teachers (61 males and 265 females; Mage = 31.16, SD = 9.83). This sample included 185 students and pre-service teachers and 141 in-service teachers who mainly taught at elementary schools (54.6%).

2.1.2 Material and procedure

As indicated above, participants received an email informing them about the purpose of the study as well as the way in which it would be conducted. Participants were then invited to give their written consent. They were informed that their participation was voluntary, that they could leave the study without consequence, and that they would not receive any financial compensation for their participation. Once consent was given, participants were asked to provide information on measures of their personal values and attitudes toward inclusive education. The order in which this information was provided was balanced between participants (167 started with the attitudes questionnaire while 159 started with the values questionnaire). At the end of the questionnaire, they provided demographic information about themselves and received more details regarding the purpose of the study. This study received an IRB approval (IRB00011540-2019-07).

2.1.2.1 Personal values

Data were collected with the PVQ-RR (the Portrait Value Questionnaire, see Schwartz et al., 2012), which was developed to measure the specific values encompassed within four higher-order values. Items described a person in terms of what is important to him/her. The respondents were asked to answer each item with the following question ‘How much is this person like you?’ on a scale ranging from 1 ‘not like me at all’ to 6 ‘very much like me’. Following recommendation (Schwartz et al., 2012), four scores were computed to get these higher-order values. For self-transcendence, the score combined the means of 18 items (for example, “It is important to him/her to be tolerant toward all kinds of people and groups.”, α = 0.84, M = 5.04, SD = 0.51). For openness to change, the score combined the means of 12 items (for example, “It is important to him/her to take risks that make life exciting.”, α = 0.83, M = 4.87, SD = 0.63). For self-enhancement, the score combined the means of 12 items (for example, “It is important to him/her to have the power to make people do what he/she wants.”, α = 0.84, M = 3.42, SD = 0.79). Finally, for conservation, the score combined the means of 15 items (for example, “It is important to him/her to maintain traditional values and ways of thinking.”, α = 0.86, M = 4.32, SD = 0.74).

2.1.2.2 Attitudes toward inclusive education

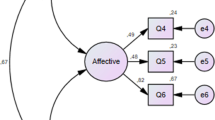

Participants completed the Multidimensional Attitudes Toward Inclusive Education Scale (MATIES) devised by Mahat (2008). This 18-item scale assesses teachers’ attitudes toward inclusive education (for example, “I believe that an inclusive school permits the academic progression of all students regardless of their ability”, “I get irritated when I am unable to understand students with a disability”) on a six-point scale from 1 “totally disagree”, to 6 “totally agree”. The reliability analysis was satisfactory (α = 0.91) and a mean score was computed (M = 4.41, SD = 0.81). It should be noted that the MATIES scale encompasses six items measuring the cognitive dimension of attitudes (i.e., reflecting teachers’ perceptions and beliefs about inclusive education), six items measuring the affective dimension (i.e., representing teachers’ feelings and emotions associated with inclusive education) and six items measuring the behavioral dimension (i.e., teachers’ intentions to act in a certain manner toward inclusive education).Footnote 3 Correlations between variables are displayed in Table 2.

2.2 Results

2.2.1 Pre-registered analyses

We used linear regression analyses in order to examine our hypotheses. More precisely, the four different higher-order values scores were entered simultaneously as predictors of participants’ attitudes toward inclusive education. It should be noted that the preliminary analyses controlling for participants’ gender, teaching level, and teaching experience as well as questionnaire order were pre-registered. The results are detailed below.

2.2.2 Preliminary analysis

A linear regression analysis including “teachers higher-order values scores” (four continuous variables), teachers’ gender (coded − 1 for male, + 1 for female), teaching level (coded − 1 for elementary schools and + 1 for middle and high schools), teaching experience (coded − 1 for students and pre-service teachers and + 1 for in-service teachers) and order of the questionnaire (coded − 1 for teachers who started with the attitudes questionnaire and + 1 for those who started with the values questionnaire) was conducted. The results indicated that teaching experience was the only significant predictor, B = − 0.23, SE = 0.08, t(317) = − 2.86, p = 0.004, ηp2 = 0.02, 95% CI [− 0.39, − 0.07]. Neither gender, B = 0.14, SE = 0.10, t(317) = 1.42, p = 0.15, ηp2 = 0.00, 95% CI [− 0.05, 0.35], teaching level, B = − 0.08, SE = 0.08, t(317) = − 0.99, p = 0.32, ηp2 = 0.00, 95% CI [− 0.24, 0.07], nor order of the questionnaire, B = 0.02, SE = 0.08, t(317) = 0.37, p = 0.71, ηp2 = 0.00, 95% CI [− 0.12, 0.18], significantly predicted attitudes. As a result, the main analysis was conducted while controlling only the variance explained by teaching experience.

2.2.3 Main analysis

The final model included five predictors: the level of teachers’ self-transcendence, openness to change, self-enhancement and conservation, and participants’ teaching experience. Results indicated that teachers’ level of self-transcendence was positively linked to the level of attitudes, B = 0.61, SE = 0.09, t(320) = 6.37, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.11, 95% CI [0.42, 0.80]. In the same vein, the more a teacher endorsed openness-related values, the more favorable they tended to be toward inclusive education, B = 0.19, SE = 0.08, t(320) = 2.34, p = 0.020, ηp2 = 0.01, 95% CI [0.03, 0.35]. Regarding self-enhancement values, the results indicated a significant negative relationship, B = − 0.20, SE = 0.06, t(320) = − 3.11, p = 0.002, ηp2 = 0.02, 95% CI [− 0.34, − 0.07]. Finally, in contradiction to our hypothesis, conservation values did not appear to be related to teachers’ attitudes toward inclusive education, B = − 0.02, SE = 0.07, t(320) = − 0.31, p = 0.75, ηp2 = 0.00, 95% CI [− 0.15, 0.11]. Participants’ teaching experience was still significantly related to their attitudes, B = − 0.24, SE = 0.08, t(320) = − 3.04, p = 0.003, ηp2 = 0.02, 95% CI [− 0.40, − 0.08].

In other words, these results confirmed that the more teachers endorsed the values of self-transcendence and openness to change in their life, the more they seemed to express positive attitudes toward inclusive education. In contrast, the more they pursued the values of self-enhancement, the more they expressed negative attitudes toward inclusive education.

2.3 Discussion

This first study was conducted in order to test the existence of a relationship between personal values and attitudes toward inclusive education. We argued that teachers’ personal values are related to their attitudes. Our general hypothesis was partly validated. In support of our hypothesis, it was revealed that the more teachers give weight to the values of self-transcendence or openness to change, the more positive their attitudes were toward inclusive education and, conversely, the more teachers give weight to values of self-enhancement, the more negative their attitudes to inclusive education. Contrary to our hypothesis, conservation values were not related to teachers’ attitudes toward inclusive education.

However, those findings must be interpreted with caution for at least two reasons. First, this study was correlational and the sample size may have been under-estimated, given the rather small effect size of some predictors. Additionally, despite the complete anonymity of the survey to prevent social desirability bias (Paulhus, 1991), it is plausible that some teachers were willing to produce an image of themselves that was positive in terms of the context and social norms (Tournois et al., 2000). This may have biased both their self-reported attitudes toward inclusive education and their values in a favorable direction. In order to ensure the robustness of and to consolidate these initial results, replication with a larger sample, another measure of teachers’ values, and a control of participants’ tendency toward social desirability was conducted.

3 Study 2

3.1 Method

3.1.1 Participants

Based on our previous results, the weaker effect was (f2 = 0.011). In order to have an 80% chance of replicating this effect if real, an a priori power analysis was performed with Gpower 3.1. (Faul et al., 2007). This revealed that 538 participants would be needed to detect such a small-sized effect with a targeted power of 0.80. This pre-registered study (preregistration form available https://aspredicted.org/gi2y8.pdf) was sent to many teachers as part of a larger project that included two other studies. After one month of data collection, the whole project sample was randomly divided into two data sets. The full sample for this study included 540 teachers, but 13 of them did not complete all the socio-demographic information, and were consequently removed from the analysis. The final sample included 527 participants: 378 were female teachers and 149 were male teachers. This sample included 23 pre-service teachers and 504 in-service teachers and teachers with another status (e.g., school librarians). Those teachers mainly taught in middle and high schools (98.1%).

3.1.2 Measures

As in Study 1, teachers were first informed of the purpose and procedure of the study, then asked to give their written consent and were advised that they would not receive financial compensation for their voluntary participation. Once consent was given, teachers were asked to complete the required measures. At the end of the questionnaire, they provided their demographic information and received a debriefing regarding the purpose of the research project. This study received an IRB approval (IRB00011540-2019-07).

3.1.2.1 Personal values

The data collection was part of a larger survey so we chose to measure the values with a tool developed to very briefly measure each of the ten specific values encompassed within four higher-order values: the Ten Item Values Inventory (TIVI, Sandy et al., 2017). The TIVI is composed with short verbal portraits of individuals (for example “It is very important for this person to help the people close to him or her. He or she cares about their well-being”). Respondents had to rate how similar or dissimilar they were from the person being portrayed using a Likert scale from 1 “not at all like me” to 6 “very much like me”. Four scores were then computed to reach the higher-order values. For self-transcendence, the score combined the means of two items (α = 0.53, M = 5.30, SD = 0.70). For openness to change, the score combined the means of three items (α = 0.54, M = 4.27, SD = 0.86). For self-enhancement, the score combined the means of two items (α = 0.56, M = 2.60, SD = 1.10). Finally, for conservation, the score combined the means of three items (α = 0.59, M = 3.97, SD = 1.06). It should be noted that reliability coefficients are questionable, probably due the low number of items for each higher-order value as well as the heterogeneity of the lower-order values.

3.1.2.2 Attitudes toward inclusive education

A three-item measure, inspired by that used in Study 1 (i.e., MATIES, Mahat, 2008), was designed to assess teachers’ attitudes toward inclusive education. For the measures, participants used a five-point Likert scale (1 = “totally disagree”, 5 = “totally agree”) to respond to questions about the cognitive, affective and behavioral dimensions of attitudes (e.g., “I am willing to adapt my lessons to respond to the needs of all students regardless of their abilities”, α = 0.68, M = 3.48 SD = 0.93, one reversed item).

3.1.2.3 Social desirability

A brief tool on the impression management dimension of social desirability was used. The KSE-G (Nießen et al., 2019, see also Lüke & Grösche, 2018) is a tool designed to assess social desirability with regard to two aspects: exaggerating Positive Qualities (PQ+) and minimizing Negative Qualities (NQ−). The tool was translated into French. Participants had to answer a six-item scale composed of sentences with which the respondent had to agree or disagree, regarding their perception of themselves (e.g., “Sometimes I only help people if I hope to get something in exchange.”), using a five-point rating scale ranging from 1 “doesn't apply at all” to 5 “applies completely”. Three items measured the exaggeration of positive qualities (α = 0.55, M = 3.78, SD = 0.59) and three items measured the minimization of negative qualities (α = 0.57, M = 1.64, SD = 0.62). Descriptive statistics and zero-order correlations of the present data are displayed in Table 3.

3.2 Results

3.2.1 Pre-registered analyses

A preliminary analysis controlling for participants’ gender and teaching experience was conducted. A linear regression including teachers’ higher-order values scores (four continuous variables), the two social desirability scales (two continuous variables), teachers’ gender (coded − 1 for male, + 1 for female), and teaching experience (coded − 1 for pre-service teachers, + 1 for in-service teachers) was conducted. The analysis shows that gender is significantly associated with attitudes, B = 0.28, SE = 0.08, t(518) = 3.19, p = 0.001, ηp2 = 0.02, 95% CI [0.10, 0.45], meaning that women hold more positive attitudes toward inclusion than men. The exaggerating positive qualities’ dimension (PQ+) is also positively and significantly associated with teachers’ attitudes, B = 0.14, SE = 0.07, t(518) = 2.08, p = 0.038, ηp2 = 0.00, 95% CI [0.00, 0.28].

The results indicated that neither participants’ teaching experience B = − 0.27, SE = 0.19 t(518) = − 1.43, p = 0.151, ηp2 = 0.00, 95% CI [− 0.65, 0.10] nor social desirability regarding minimizing Negative Qualities (NQ−) significantly predict attitudes, B = 0.08, SE = 0.06, t(518) = 1.28, p = 0.200 ηp2 = 0.00, 95% CI [− 0.04, 0.21], so they were removed from the main analysis.

3.2.2 Main Analysis

As a result, the main analysis was conducted on a final model including six predictors: teachers’ levels of self-transcendence, openness to change, self-enhancement, conservation, participants’ gender and the social-desirability measurement of exaggerating Positive Qualities (PQ+).

Results regarding the personal values indicated that teachers’ level of self-transcendence was positively related to their attitudes, B = 0.19, SE = 0.06, t(520) = 3.20, p = 0.001, ηp2 = 0.01, 95% CI [0.07, 0.31]. In the same vein, the more teachers endorsed openness-related values, the more favorable they tended to be toward inclusive education, B = 0.14, SE = 0.05, t(520) = 2.90, p = 0.004, ηp2 = 0.01, 95% CI [0.04, 0.24]. Conservation values still did not appear to be related to teachers’ attitudes toward inclusive education, B = − 0.05, SE = 0.04, t(520) = − 1.40 p = 0.161 ηp2 = 0.00, 95% CI [− 0.13, 0.02]. And, in contrast to our hypothesis, self-enhancement values did not appear to be related to teachers’ attitudes toward inclusive education, B = − 0.00, SE = 0.04, t(520) = − 0.05 p = 0.957, ηp2 = 0.00, 95% CI [− 0.07, 0.07].

Regarding other predictors, teachers’ gender is still significantly related to attitudes B = 0.27, SE = 0.08, t(520) = 3.07, p = 0.002, ηp2 = 0.018, 95% CI [0.09, 0.44]. Social desirability regarding PQ+ is also related to teachers’ attitudes toward inclusive education B = 0.13, SE = 0.06, t(520) = 1.92, p = 0.055, ηp2 = 0.007, 95% CI [− 0.00, 0.26].

In other words, these results confirm that the more participants endorsed values of self-transcendence and openness to change in their life, the more they seemed to express positive attitudes toward inclusive education. These results also tend to confirm that there is no relationship between conservation and attitudes toward inclusive education, and that no conclusions could be drawn regarding the relationship between self-enhancement values and attitudes.

Finally, a Relative Importance Analysis (RIA) was conducted using RWA-Web (Tonidandel & Lebreton, 2015) to properly partition the variance allocated to the predictors (Kraha et al., 2012; Tonidandel & Lebreton, 2011). RIA addresses this issue by generating a set of variables that are orthogonal to one another (Johnson, 2000). Results from this analysis are summarized in Table 4. In short, the results indicate that the combination of factors explained some variance in ATI (R2 = 0.088). The results of this RIA confirmed that the most contributing predictor is self-transcendence values (RS-RW (Rescale Relative Weight) = 34.33%), followed by openness to change and gender, which contributed almost equally to the model (RS-RWOp = 28.37%; RS-RWG = 20.95%) and finally social desirability (RS-RWSD = 12.27%). Self-enhancement remained non-significant, as did conservation values (all ps > 0.06). Those results gave a clearer insight of how each predictor contributes to the model.

3.3 Discussion

Study 2 aimed at replicating the initial findings about the relationship between teachers’ personal values and their attitudes toward inclusive education, while controlling for social desirability bias. The model controlling for social desirability also showed the effective relationship between some of the personal values and teachers’ attitudes toward inclusive education. The relationship between self-transcendence and openness to change, and teachers’ attitudes toward inclusive education are still significant, whereas conservation values continue to be insignificant. Surprisingly, the study was unable to replicate the findings around self-enhancement values.

However, the study does have some limitations, notably concerning measurement. Data collection was part of a larger project that was being carried out, with shorter versions of the scales on personal values and attitudes toward inclusive education, and the associated reliability could clearly bring into question the psychometric validity of the tools. Nonetheless, the fact that some of the relationships between personal values and attitudes toward inclusive education have been replicated with less powerful tools could also be perceived as a strength of these findings.

4 General discussion

Inclusive education is a major concern in our societies, particularly when it comes to education (Ferguson, 2008). Despite the fact that it promotes benevolence, universalism, and many other shared and agreed upon values, implementation of inclusive education remains difficult (Gossot, 2005; Plaisance, 2010). One of the most significant reasons could be the attitudes that teachers express toward this policy (Elliott, 2008; Leatherman & Niemeyer, 2005).

In this research, we sought to investigate a hypothesized factor contributing to these attitudes, namely teachers’ personal values. This hypothesis was essentially made on the observation that as well as inclusive school conveying values such as equity, caring, and social justice (Prud’homme et al., 2011), teachers also express values which reflect their own view of what is important in their job and school (Dufour & Berkey, 1995). Indeed, as brought to light by numerous pieces of research, values are everywhere, and drive attitudes and behaviors (Feather, 1992; Rokeach, 1973; Schwartz, 1992). We hypothesized that there may be an effective relationship between the personal values that teachers express and their attitudes toward inclusive education. More precisely, we proposed that the values of self-transcendence and openness to change could be positively related to teachers’ attitudes toward inclusive education, because they emphasize, among other things, well-being and tolerance. Conversely, we suggested that self-enhancement and conservation values would be negatively related to teachers’ attitudes toward inclusive education, because they incorporate ideas and motivations that are less coherent with inclusive education. Our results partly support those hypotheses.

More precisely, based on these two studies, our results show that the more teachers give weight to the self-transcendence values, the more positive their attitudes toward inclusive education. This might be explained by the fact that the implementation of the inclusive school, where everyone has a place to grow to their fullest potential, requires prioritizing the care and well-being of others, as well as the expression of supportive behaviors—which are the main motivations conveyed by those values (Schwartz, 2006; Wach & Hammer, 2003). Similarly, the more teachers endorse openness to change values—demonstrating a willingness to control, master and to live a stimulating, creative and challenging life—the more positive their attitudes toward inclusive education. It should be noted that those two higher-order values were related to attitudes toward inclusion, while controlling for social desirability bias.

The results about self-enhancement values were mixed and brought into question a number of key issues. The results of Study 1 pointed out that the endorsement of self-enhancement values drives teachers to express more negative attitudes toward inclusive education, while in Study 2 this finding was not replicated. This lack of consistency is puzzling, since inclusive education implies real change and challenges teachers’ practices and habits (Ferguson, 2008; Moberg et al., 2019), a challenge that could be perceived as a threat to effective power and success (i.e., the two self-enhancement values). The use of different tools in the two studies to measure values on the one hand and attitudes toward inclusive education on the other may explain these contradictory results. Indeed, it is possible that the short versions are less sensitive than the longer ones. Further investigations need to be carried out to clarify the exact reason for this discrepancy.

Finally, in contradiction to some of our predictions, our results also show that there is no relationship between conservation values and attitudes toward inclusive education, despite our hypothesis. This result is somewhat surprising, considering that conservation values express motivations that are clearly contradictory to the changes that inclusive education requires. This lack of a relationship may stem from the fact that the inclusive education, despite a few disagreements, generates few explicit criticisms due to its high social valuation and the fact that it calls only for the expression of consensus and obvious social norms (Lui et al., 2015). Although Bardi and Schwartz (2003) found that normative pressure weakened the relationship between values and behavior, it may be possible that the same pressure may have led some teachers to mis-estimate (and probably over-estimate) their conservation values, which could have further impacted the relationship to their attitudes toward inclusive education. Nonetheless, these results suggest that teachers’ personal values can plausibly be incorporated into the constellation of factors known to influence teachers' attitudes (Avramidis & Norwich, 2002), and more precisely those related to teachers themselves.

4.1 Limits and perspectives

As mentioned above, this work has some limitations that will guide our future research. Initially, it is important to assume that the two studies only reveal correlational relationships, and causality must now be addressed. Secondly, values are cognitive structures that must be activated in order to affect information, behavior and attitudes (Verplanken & Holland, 2002), and that can be triggered by contextual clues, possibly suggesting that they need to be measured while taking the context into account. And, finally, our first sample was largely composed of student teachers or aspiring teachers, and it is notable that they are known to have more favorable attitudes toward inclusive education than their more experienced counterparts (Alghazo & Naggar Gaad, 2004; Avramidis et al., 2000). Since these ones evolve toward a negative valence during the training process (Varcoe & Boyle, 2014), it may be possible that the correlations in Study 1 were overestimated.

Finally, in terms of perspectives, it is worth noting that although values remain fairly steady and fairly consistent over time (Schwartz, 2006), they may evolve through academic socialization (Williams, 1979), but also through a number of processes (Bardi & Goodwin, 2011) in which a whole range of environmental cues play a significant role. Therefore, to fully understand how values influence teachers’ attitudes toward inclusion, it seems appropriate to also consider the values stemming from the educational system itself. Altogether, it might help thinking about training curricula that would integrate these elements into their structure and/or content could constitute interesting levers for improving teachers’ attitudes toward inclusive education.

5 Conclusion

The results of this research provide scientific evidence supporting links between teachers’ personal values and attitudes, particularly toward inclusive education. Although our results are mixed, they bring additional information regarding the factors influencing teachers’ attitudes toward inclusive education, opening up a number of avenues for future research. Among them, the search for causality, as well as the understanding of how the educational system values impact teachers’ attitudes toward inclusive education seems to be quite promising. Such results would enable us to consider new ways to train teachers in order to improve implementation of inclusive education policies. And thus, making the values to take their entire place in the development of a real inclusive education by ensuring openness, universalism and benevolence to be expressed, and so no child would be left behind anymore.

Data availability

(data transparency): Data and material are available here: https://osf.io/frqve/?view_only=1de2d0cdd493418fab7ed3a26b014164

Code availability

Not applicable.

Notes

It should be noted that the model actually defined ten lower-order values (namely autonomy, stimulation, hedonism, achievement, power, security, conformity, tradition, benevolence and universalism). However, since examining the influence of each of these lower-order values is beyond the scope of this paper, they will not be extensively presented here (for a thorough review, see Schwartz et al., 2012).

It should be noted that in accordance with new research practices, the studies presented here were pre-registered (van 't Veer & Giner-Sorollac, 2016) and sample size calculations were performed a priori in order to enhance the robustness and reproducibility of the results. Data and material are available here: https://osf.io/frqve/?view_only=1de2d0cdd493418fab7ed3a26b014164.

Although the main analysis was conducted on the mean scale score, an exploratory analysis examined whether the hypothesized links between values and attitudes can be found for each dimension separately (see supplementary material).

References

Ajzen, I., & Fishbein, M. (1977). Attitude-behavior relations: A theoretical analysis and review of empirical research. Psychological Bulletin, 84(5), 888–918. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.84.5.888

Alghazo, E. M., & El Naggar Gaad, E. (2004). General education teachers in the United Arab Emirates and their acceptance of the inclusion of students with disabilities. British Journal of Special Education, 31(2), 94–99. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0952-3383.2004.00335.x

Arieli, S., Grant, A. M., & Sagiv, L. (2014). Convincing yourself to care about others: An intervention for enhancing benevolence values. Journal of Personality, 82(1), 15–24. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12029

Avramidis, E., & Norwich, B. (2002). Teachers’ attitudes towards integration/inclusion: A review of the literature. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 17(2), 129–147.

Avramidis, E., Bayliss, P., & Burden, R. (2000). Student teachers’ attitudes towards the inclusion of children with special educational needs in the ordinary school. Teaching and Teacher Education, 16(3), 277–293. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0742-051X(99)00062-1

Bardi, A., & Goodwin, R. (2011). The dual route to value change: Individual processes and cultural moderators. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 42(2), 271–287. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022110396916

Bardi, A., & Schwartz, S. H. (2003). Values and behavior: Strength and structure of relations. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 29(10), 1207–1220. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167203254602

Boer, D., & Fischer, R. (2013). How and when do personal values guide our attitudes and sociality? Explaining cross-cultural variability in attitude–value linkages. Psychological Bulletin, 139(5), 1113–1147. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0031347

Brandes, J. A., & Crowson, H. M. (2009). Predicting dispositions toward inclusion of students with disabilities: The role of conservative ideology and discomfort with disability. Social Psychology of Education, 12(2), 271–289. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-008-9077-8

Chataigné, C., & Guimond, S. (2014). Psychologie des valeurs [Psychology of values]. De Boeck.

de Boer, A., Pijl, S. J., & Minnaert, A. (2011). Regular primary schoolteachers’ attitudes towards inclusive education: A review of the literature. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 15(3), 331–353. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603110903030089

deBettencourt, L. U. (1999). General educators’ attitudes toward students with mild disabilities and their use of instructional strategies: Implications for training. Remedial and Special Education, 20(1), 27–35. https://doi.org/10.1177/074193259902000104

Desombre, C., Lamotte, M., & Jury, M. (2019). French teachers’ general attitude toward inclusion : The indirect effect of teacher efficacy. Educational Psychology, 39(1), 38–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2018.1472219

DuFour, R., & Berkey, T. (1995). The principal as staff developer. Journal of Staff Development, 16(4), 2–6.

Eagly, A. H., & Chaiken, S. (1993). The psychology of attitudes. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich College Publishers.

Elliott, S. (2008). The effect of teachers’ attitude toward inclusion on the practice and success levels of children with and without disabilities in physical education. International Journal of Special Education, 23(3), 48–55.

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A.-G., & Buchner, A. (2007). G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 39(2), 175–191. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03193146

Feather, N. T. (1992). Values, valences, expectations, and actions. Journal of Social Issues, 48(2), 109–124. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.1992.tb00887.x

Ferguson, D. L. (2008). International trends in inclusive education: The continuing challenge to teach each one and everyone. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 23(2), 109–120. https://doi.org/10.1080/08856250801946236

Frangieh, B., & Weisser, M. (2013). Former les enseignants à la pratique de l’inclusion scolaire [Training teachers for inclusive education practice]. Recherche & Formation, 73, 9–20. https://doi.org/10.4000/rechercheformation.2071

Girandola, F., & Joule, R.-V. (2013). Attitude, changement d’attitude et comportement. In L. Bégue & O. Desrichard (Eds.), Psychologie sociale : la nature sociale de l’être humain [Social Psychology: The social nature of the human being] (pp. 221–248). De Boeck.

Gollwitzer, P. M. (1999). Implementation intentions: Strong effects of simple plans. American Psychologist, 54(7), 493–503. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.54.7.493

Gossot, B. (2005). La France vers un système inclusive? [France towards an inclusive system?]. Reliance, 16(2), 31–33. https://doi.org/10.3917/reli.016.0031

Gutman, A. (2004). Unity and diversity in democratic multicultural education: Creative and destructive tensions. In J. A. Banks (Ed.), Diversity and citizenship education : Global perspectives (pp. 71–98). Jossey-Bass.

Johnson, J. W. (2000). A heuristic method for estimating the relative weight of predictor variables in multiple regression. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 35(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327906MBR3501_1

Jury, M., Perrin, A.-L., Rohmer, O., & Desombre, C. (2021). Attitudes toward inclusive education: An exploration of the interaction between teachers’ status and students’ type of disability within the French context. Frontiers in Education, 6, 655356. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2021.655356

Kraha, A., Turner, H., Nimon, K., Zientek, L. R., & Henson, R. K. (2012). Tools to support interpreting multiple regression in the face of multicollinearity. Frontiers in Psychology. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2012.00044

Kristiansen, C. M., & Zanna, M. P. (1988). Justifying attitudes by appealing to values: A functional perspective. British Journal of Social Psychology, 27(3), 247–256. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8309.1988.tb00826.x

Leatherman, J., & Niemeyer, J. (2005). Teachers’ attitudes toward inclusion: Factors influencing classroom practice. Journal of Early Childhood Teacher Education, 26(1), 23–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/10901020590918979

Lui, M., Sin, K.-F., Yang, L., Forlin, C., & Ho, F.-C. (2015). Knowledge and perceived social norm predict parents’ attitudes towards inclusive education. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 19(10), 1052–1067. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2015.1037866

Lüke, T., & Grosche, M. (2018). What do I think about inclusive education? It depends on who is asking. Experimental evidence for a social desirability bias in attitudes towards inclusion. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 22(1), 38–53. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2017.1348548

MacFarlane, K., & Woolfson, L. M. (2013). Teacher attitudes and behavior toward the inclusion of children with social, emotional and behavioral difficulties in mainstream schools: An application of the theory of planned behavior. Teaching and Teacher Education, 29, 46–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2012.08.006

Mahat, M. (2008). The development of a psychometrically-sound instrument to measure teachers’ multidimensional attitudes toward Inclusive Education. International Journal of Special Education, 23(1), 82–92.

Maio, G. R. (2010). Mental representations of social values. In Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 42, pp. 1–43). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2601(10)42001-8

McGhie-Richmond, D., Irvine, A., Loreman, T., Lea Cizman, J., & Lupart, J. (2013). Teacher perspectives on inclusive education in rural Alberta, Canada. Canadian Journal of Education/revue Canadienne De L’éducation, 36(1), 195–239.

Meijer, C. J. W. (2010). Special needs education in Europe: Inclusive policies and practices. Zeitschrift für Inklusion. https://www.inklusion-online.net/index.php/inklusion-online/article/view/136

Moberg, S., & Savolainen, H. (2003). Struggling for inclusive education in the North and the South: Educators’ perceptions on inclusive education in Finland and Zambia. International Journal of Rehabilitation Research, 26(1), 21.

Moberg, S., Muta, E., Korenaga, K., Kuorelahti, M., & Savolainen, H. (2019). Struggling for inclusive education in Japan and Finland: Teachers’ attitudes towards inclusive education. European Journal of Special Needs Education. https://doi.org/10.1080/08856257.2019.1615800

Moran, A. (2007). Embracing inclusive teacher education. European Journal of Teacher Education, 30(2), 119–134. https://doi.org/10.1080/02619760701275578

Nießen, D., Partsch, M. V., Kemper, C. J., & Rammstedt, B. (2019). An English-language adaptation of the social desirability–gamma short scale (KSE-G). Measurement Instruments for the Social Sciences, 1(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.1186/s42409-018-0005-1

Ogay, T. (2004). Valeurs des sociétés et des individus, un état des lieux modèles en psychologie interculturelle. [Values of societies and individuals: Models offered by cross-cultural psychology.]. Cahiers Internationaux De Psychologie Sociale, 61, 7–20.

Olson, J. M., & Maio, G. R. (2003). Attitudes in Social Behavior. In I. B. Weiner (Ed.), Handbook of psychology personality and social psychology (Vol. 5, pp. 299–325). Wiley. https://doi.org/10.1002/0471264385.wei0513

Paulhus, D. L. (1991). Measurement and control of response bias. In Measures of personality and social psychological attitudes (pp. 17–59). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-590241-0.50006-X

Plaisance, E. (2010). L’éducation inclusive, genese et expansion d’une orientation éducative. Le cas Français. [Inclusive education, genesis and expansion of an educational orientation. The French case] [Conference Session] Congrès de l’Actualité de la recherche en éducation et en formation (AREF), Université de Genève, https://plone.unige.ch/aref2010/communications-orales/premiers-auteurs-en-p/Leducation%20inclusive.pdf.

Prud’Homme, L., Duchesne, H., & Bonvin, P. (2017). L’inclusion scolaire : Ses fondements, ses acteurs et ses pratiques [Inclusive Education: Its Foundations, Actors and Practices. De Boeck.

Prud’homme, L., Vienneau, R., Ramel, S., & Rousseau, N. (2011). La légitimité de la diversité en éducation : Réflexion sur l’inclusion [The Legitimacy of Diversity in Education: A Reflection on Inclusion]. Éducation Et Francophonie, 39(2), 6–22. https://doi.org/10.7202/1007725ar

Rokeach, M. (1973). The nature of human values. Free Press.

Ros, M., Schwartz, S. H., & Surkiss, S. (1999). Basic individual values, work Values, and the meaning of work. Applied Psychology, 48(1), 49–71. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-0597.1999.tb00048.x

Sandy, C. J., Gosling, S. D., Schwartz, S. H., & Koelkebeck, T. (2017). The development and validation of brief and ultrabrief measures of values. Journal of Personality Assessment, 99(5), 545–555. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.2016.1231115

Savolainen, H., Engelbrecht, P., Nel, M., & Malinen, O.-P. (2012). Understanding teachers’ attitudes and self-efficacy in inclusive education: Implications for pre-service and in-service teacher education. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 27(1), 51–68. https://doi.org/10.1080/08856257.2011.613603

Schönbrodt, F. D., & Perugini, M. (2013). At what sample size do correlations stabilize? Journal of Research in Personality, 47(5), 609–612. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2013.05.009

Schwartz, S. H. (1992). Universals in the content and structure of values: Theoretical advances and empirical tests in 20 countries. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology (Vol. 25, pp. 1–65). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2601(08)60281-6

Schwartz, S. H. (2006). Les valeurs de base de la personne : Théorie, mesures et applications [The basic values of the person: Theory, measurements and applications]. Revue Française De Sociologie, 47(4), 929–968. https://doi.org/10.3917/rfs.474.0929

Schwartz, S. H., Cieciuch, J., Vecchione, M., Davidov, E., Fischer, R., Beierlein, C., Ramos, A., Verkasalo, M., Lönnqvist, J.-E., Demirutku, K., Dirilen-Gumus, O., & Konty, M. (2012). Refining the theory of basic individual values. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 103(4), 663–688. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029393

Sharma, U., & Sokal, L. (2016). Can teachers’ self-reported efficacy, concerns, and attitudes toward inclusion scores predict their actual inclusive classroom practices? Australasian Journal of Special Education, 40(1), 21–38. https://doi.org/10.1017/jse.2015.14

Thomazet, S. (2006). De l’intégration à l’inclusion. Une nouvelle étape dans l’ouverture de l’école aux différences [From integration to inclusion. A new stage in opening the school to differences]. Le Français Aujourd’hui, 152, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.3917/lfa.152.0019

Tonidandel, S., & LeBreton, J. M. (2011). Relative importance analysis: A useful supplement to regression analysis. Journal of Business and Psychology, 26(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-010-9204-3

Tonidandel, S., & LeBreton, J. M. (2015). RWA Web: A free, comprehensive, web-based, and user-friendly tool for relative weight analyses. Journal of Business and Psychology, 30(2), 207–216. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-014-9351-z

Tournois, J., Mesnil, F., & Kop, J.-L. (2000). Autoduperie et héteroduperie : Un instrument de mesure de la désirabilité sociale [Self-deception and other-deception: A social desirability questionnaire]. European Review of Applied Psychology/revue Européenne De Psychologie Appliquée, 50(1), 219–233.

UNESCO. (1994). The Salamanca statement andframework for action on special needs education. Adopted by the world conference on special needs education: Access and equity. UNESCO.

UNESCO. (2016). Education 2030: Incheon Declaration and Framework for Action for the implementation of Sustainable Development Goal 4: Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning. UNESCO.

van ’t Veer, A. E., & Giner-Sorolla, R. (2016). Pre-registration in social psychology—A discussion and suggested template. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 67, 2–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2016.03.004

Varcoe, L., & Boyle, C. (2014). Pre-service primary teachers’ attitudes towards inclusive education. Educational Psychology, 34(3), 323–337. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2013.785061

Verplanken, B., & Holland, R. W. (2002). Motivated decision making: Effects of activation and self-centrality of values on choices and behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.82.3.434

Vislie, L. (2003). From integration to inclusion: Focusing global trends and changes in the western European societies. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 18(1), 17–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/0885625082000042294

Wach, M., & Hammer, B. (2003). La structure des valeurs est-elle universelle? Genèse et validation du modèle compréhensif de Schwartz [Is the value structure universal? Genesis and validation of the comprehensive Schwartz’s model]. L’Harmattan.

Ward, J., Center, Y., & Bochner, S. (1994). A question of attitudes: Integrating children with disabilities into regular classrooms? British Journal of Special Education, 21(1), 34–39. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8578.1994.tb00081.x

Williams, R. (1979). Change and stability in values and value system: A sociological perspective. Simon and Schuster.

Funding

This study was partly funded by the « Caisse Nationale de Solidarité pour l’Autonomie (CNSA)» (Grant no. IReSP-17-AUT4-08).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by Anne-Laure Perrin, Mickaël Jury and Caroline Desombre. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Anne-Laure Perrin and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Perrin, AL., Jury, M. & Desombre, C. Are teachers’ personal values related to their attitudes toward inclusive education? A correlational study. Soc Psychol Educ 24, 1085–1104 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-021-09646-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-021-09646-7