Abstract

In this paper, we examine the relationship between basic psychological needs and student engagement in a population of Italian secondary school students. To measure the psychological needs, we have selected a set of indicators that, beyond the needs for autonomy, competence and relatedness, also include the need for justice, which is crucial in adolescence when the degree of sensitivity to the ways people behave in interpersonal interactions is well developed. To measure student engagement, we have considered the four-dimensional structure of the construct, which has added the factor of agentic engagement to the three conventional dimensions of emotional, behavioural and cognitive engagement. Participants were 640 secondary school Italian students aged 15–17. The results confirm that justice should be considered as an additional basic need in school settings, as it fosters intrinsic student motivation and engagement. Moreover, our findings provide evidence that agency is a dimension that enriches the construct of student engagement. In the conclusion, justice and agency are treated as constructs that deserve to be more deeply considered in future research into learning environments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Self-determination (Ryan and Deci 2000, 2002; Vansteenkiste et al. 2010) is a psychological construct capable of accounting for people’s efforts at being active contributors to their behaviour, which is self-regulated and goal-directed. In case of adolescence, self-determination is crucial as it allows youngsters to individualize themselves by exploring and dealing with the multiple personal and social transformations they are experiencing (Nota et al. 2011; Reeve 2012). In general terms, the literature is consistent in considering self-determined persons as having high aspirations, persevering in the face of obstacles, experiencing a sense of wellbeing, and feeling responsible for their proper functioning overall (Niemiec and Ryan 2009; Sheldon and Gunz 2009; Vallerand 1997). It is assumed that the intrinsic motivation to achieve these goals lies in the basic psychological needs of autonomy, competence and relatedness (Ryan and Deci 2000, 2002), which govern human actions by soliciting a constant dynamic between the self and the context. An intrinsically motivated individual is thus more willing to show engagement and commitment in life and work.

In this paper, we have examined the relationship between basic psychological needs and student engagement in a population of Italian adolescents. To measure the psychological needs, we have selected a set of indicators that, beyond the needs for autonomy, competence and relatedness, also included the need for justice (Peter and Dalbert 2010; Taylor 2003). To measure the student engagement, we have considered the four-dimensional structure of the construct, which has added the factor of agentic engagement (Reeve and Tseng 2011) to the conventional three dimensions of emotional, behavioural and cognitive engagement.

In the introduction, first of all we discuss the literature on basic psychological needs, after we consider school justice as an additional basic need, and then review studies conducted on the four dimensions of engagement. Before delving into the research description, we also provide some study setting information that serves as a rationale for our aims and hypotheses.

1.1 Basic psychological needs

The satisfaction of three basic needs—Autonomy, Competence, Relatedness—is traditionally posited as grounding an individual’s psychological growth and wellbeing (Deci and Ryan 1985; Reeve 2012; Sheldon and Gunz 2009). The need for Autonomy refers to the importance of experiencing a sense of freedom in behaving and making choices, with a perceived internal locus of control. The need for Competence expresses the urge to feel effective and capable of mastering challenging tasks, carrying out one’s activities, and reaching the desired goals. The need for Relatedness has to do with the human necessity to feel close, cared for, and emotionally connected with others. From the perspective of Self Determination Theory (Deci and Ryan 1985; Vansteenkiste et al. 2010), these basic needs are considered the intrinsic motive for volitionally undertaking participation for one’s pleasure and interest.

On this issue, the literature is consistent in providing evidence about the relationship between need satisfaction and wellbeing. Fewer studies have instead focused on the effects of need frustration, which is not merely conceived as the absence of need satisfaction, but rather as a distinct construct (Longo et al. 2016) that negatively impacts on an individual’s motivation by favouring the engendering of dissatisfaction and depression (Bartholomew et al. 2011; Sheldon and Gunz 2009). In this regard, some authors (Wilson et al. 2003) have suggested that perceived tension could be conceptualized as a fourth dimension of psychological need.

Along the same lines of reasoning, Reeve and Sickenius (1994) developed and validated the Activity Feeling Scale (AFS) for measuring the psychological needs underlying intrinsic motivation. In addition to the factors of autonomy, competence and relatedness, a fourth dimension based on perceived tension was included in the questionnaire. The authors claimed that, even though it is not a psychological need, perceived tension serves as an emotional marker that is antagonistic to intrinsic motivation. Accordingly, the lack of perceived tension can be conceptualized as a relevant emotional need within the learning environment, one that vitalizes students and sustains their school engagement.

1.2 Justice as an additional psychological need

For adolescent students, the subjective experience of being treated fairly by teachers plays a significant role in the formers’ perception of a positive school environment (Peter and Dalbert 2010).

In the social and organizational psychology literature, justice has long been conceived as a psychological need (Cropanzano et al. 2001; Mayer et al. 2008; Taylor 2003). By relying on Maslow’s pioneering work (Maslow 1943) on basic needs, Taylor (2003) observed that this eminent scholar “placed it [justice] with fairness, honesty, and orderliness in a cluster as being a precondition for the satisfaction of basic needs” (p. 216). Accordingly, Cropanzano et al. (2001) referred to the Multiple Needs Model by pointing out that “justice matters to the extent that it serves some important psychological needs” (p. 175). In this model, organisational interpersonal fairness was thus considered a conditio sine qua non for other basic human needs (here conceptualized as needs for control, belonging and self-esteem) to be satisfied.

Although Maslow considered justice as a prerequisite for basic need satisfaction and not as a need dimension in itself, Taylor (2003) advanced that psychology should consider justice on the same level as the other needs. Quoting Taylor’s words, Maslow himself would have considered justice per se “of such paramount importance as to deserve elevation to his list of basic needs” (p. 216). In the same direction, Mayer et al. (2008) have argued that the need for justice in the workplace is closely related to the three main needs described by Self Determination Theory (Ryan and Deci 2000, 2002; Vansteenkiste et al. 2010).

In this study, we posit that in the context of teacher–student interaction justice should be conceptualized as a basic psychological need as well. In classrooms, most students are highly sensitive to just or unjust interpersonal behaviours, and react when they feel that the principles of equality and equity are not respected (Dalbert and Stoeber 2006). In this field, several studies have indeed shown that the degree of fairness students attribute to a teacher’s interpersonal behaviour is associated to motivation and group cooperation skills (Chory-Assad 2002; Dalbert and Stoeber 2005; Oluwatayo et al. 2015). On the contrary, the feeling of injustice in teacher–student interactions leads to negative outcomes, such as a decline in learning commitment and a psychological disengagement from school life (Molinari et al. 2013).

1.3 Student engagement

At school, the major function of psychological needs is to vitalize students’ inner motivation, which in turn facilitates their engagement in classroom activities and tasks (Niemiec and Ryan 2009; Reeve 2013). The concept of student engagement has attracted increasing interest in scientific research as it is considered crucial for ameliorating young generations’ educational paths (Appleton et al. 2008; Jelas et al. 2016; Lawson and Lawson 2013).

Student engagement has been traditionally described as a meta-construct made up of three main dimensions (Fredericks et al. 2004; Voelkl 2012; Wang and Fredricks 2014). Emotional engagement coincides with the student’s sense of belonging to school, and with the positive or negative feelings on learning and educational activities. Behavioural engagement is defined as student participation and involvement in school and out-of-school activities. Cognitive engagement refers to the processes and strategies that students use to elaborate contents needing to be learned.

More recently, a further dimension, namely agentic engagement (Reeve 2012, 2013; Reeve and Tseng 2011), has been proposed as a fourth and essential aspect of student engagement. Reeve described agentic engagement as “the process in which students proactively try to create, enhance, and personalize the conditions and circumstances under which they learn” (Reeve 2012, p. 161). In respect to the previous three dimensions—which emphasized the way in which students react to school activities and tasks as a whole—agentic engagement adds important elements to the construct by referring to the students’ active role and transformative contribution they provide to the ongoing flow of the instruction they receive. Research in this field has provided evidence that agentic engagement is a pathway to academic progress and contributes to the creation of a motivationally supportive learning environment (Reeve 2013).

1.4 Study setting

Context matters in schools and classrooms. Environmental characteristics may indeed either serve as a support or work against student motivation and engagement. This broad perspective widens the dominant socio-psychological focus of research, in order to include salient elements of organizational school structures and cultures (Lawson and Lawson 2013).

In Italian secondary school settings, there are two organizational or structural features that we take as a rationale for our aims. First of all, and unlike most other European countries, students at Italian secondary schools are allowed no curricular flexibility. After middle school, at the age of 14, students are required to choose the track they intend to follow in the course of the following five years of secondary education. Such a track is fully and rigidly pre-defined, with no possibility for students to make subject choices. This feature of the school system raises the question as to whether autonomy can be considered as a basic psychological need for Italian students. What is missing in their case is the fundamental property for this need to be satisfied, i.e. that school should offer students opportunities to engage in matters or activities that they have freely chosen by relying on their internal locus of control (Reeve et al. 2003).

Secondly, Italian school policy is highly oriented to school outcomes, with a major focus on grading students by evaluating their skills in reproducing the same ‘pre-packaged’ knowledge. As documented in the National Report on teaching practices (Cavalli and Argentin 2010), due to the strong emphasis on individual performance, Italian students tend to experience a degree of pressure and tension at school that the literature posits as an oppositional force to intrinsic motivation.

1.5 Goals and hypotheses of the present study

The present study had three goals and hypotheses, with nine sub-hypotheses to be verified. The first goal was to test the conceptual and statistical force of a scale on psychological needs that we developed from the AFS scale (Reeve and Sickenius 1994). In this scale, along with the needs for autonomy, competence and relatedness, we also considered the dimension on perceived tension—which we call here ‘(no)tension need’ to express its antagonistic role to motivation—and the need for justice. Hypothesis 1 predicted that: (a) given the organizational features of the study setting, the need for autonomy would have weak statistical properties while the need for (no)tension would display good properties; (b) the need for justice would function as a distinct aspect of basic psychological needs, i.e. it was conceptually distinct from competence, relatedness and (no)tension needs.

The second goal was to verify intercorrelations between basic psychological needs and engagement dimensions, after having explored for possible gender and grade level effects on our assessed measures. Hypothesis 2 predicted that: (a) in agreement with Reeve and Tseng (2011), gender and grade level would have only minimal effects on basic needs and engagement, with females showing higher levels of behavioural engagement and grade level positively correlating with agentic engagement; (b) the need for justice would correlate positively and significantly with the need for competence, need for relatedness and need for (no)tension; (c) the four dimensions of engagement would correlate positively and significantly with each other, yet for agentic engagement we expected values to be not so high as to suspect an overlap among the four dimensions, in line with the Reeve and Tseng (2011) claims.

The third and final goal was to test whether emotional, behavioural, cognitive and agentic engagement would be affected by the basic psychological needs of competence, relatedness, (no)tension and justice, controlling in particular for the justice additional contribution. Hypothesis 3 predicted that (a) the need for competence would affect all engagement dimensions; (b) the need for relatedness would impact on emotional and agentic engagement; (c) the need for (no)tension would impact on behavioural, emotional and agentic engagement; (d) the need for justice would affect behavioural, emotional and agentic engagement dimensions.

2 Method

2.1 Participants

Participants were 640 (51.8% males, 48.2% females) high school Italian students aged 15–17 (mean age 16.20). They came from five large, middle class, urban schools located in Northern Italy, and were enrolled in 10th (54.2%) and 12th (45.8%) grades. Participation was voluntary and the scores were confidential and anonymous. Researchers from the project administered the questionnaire to students in their classrooms. All students and parents of minors completed a consent form. A very limited number of families (2.3%) did not give their consent to participation. The research was conducted in agreement with the ethical norms defined by the Italian National Psychological Association.

2.2 Measures

The Activity Feeling State (AFS, Reeve and Sickenius 1994; Reeve and Tseng 2011) scale is a 13-item self-report measure of perceived psychological need satisfaction. It contains four subscales assessing the degree of psychological need satisfaction associated with Autonomy (4 items), Competence (3 items), and Relatedness (3 items), as well as a perceived Tension subscale (3 items) whose items were later reversed to measure a (no)Tension need. In line with the authors’ recommendations, all these needs were assessed as situation-specific experiential states. Following the stem “During class I feel…”, participants responded to each item on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (I strongly disagree) to 7 (I strongly agree). Sample items are: “I’m doing what I want to be doing” (Need for Autonomy), “Capable” (Need for Competence), “Emotionally close to the people around me” (Need for Relatedness”), “Uptight” (Tension). As the AFS scale had never been used in Italian studies before, a back-translation procedure was adopted.

To assess the need for Justice, we relied on a short version of the Teacher Justice Scale (Dalbert and Stoeber 2006), a reliable instrument for capturing the student experience of teacher fairness in interpersonal behaviour. The scale comprised four items (range from 1 = I strongly agree to 7 = I strongly disagree; sample item “I feel my teachers generally treat me fairly”) that measured the extent to which students felt that the treatment they received in the classroom from their teachers was just.

As for Student Engagement, we made use of the questionnaire developed by Lam et al. (2014) for measuring Student Engagement in an international study from 12 countries. The questionnaire was recently validated in Italian (Mameli and Passini 2017, in press) and comprised three subscales. The Emotional Engagement (9 items; sample item “I enjoy learning new things in class”) subscale assessed the presence of positive emotions during task involvement, such as interest and fun. The Behavioural Engagement subscale (12 items; sample item “I try hard to do well in school”) referred to how involved the student is in school and out-of-school activities, in terms of attention, effort, and persistence. For emotional and behavioural subscales, students’ answers ranged from 1 (I strongly disagree) to 7 (I strongly agree). The Cognitive Engagement subscale (12 items; sample item “I try to understand how the things I learn in school fit together with each other”) measured how strategically the student attempts to learn in terms of employing sophisticated rather than superficial learning strategies, such as using elaboration rather than memorization. To this subscale, participants were asked to answer using a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (Never) to 7 (Always).

Finally, an Agentic Engagement scale was used to assess the degree to which students constructively contribute to the flow of the instruction they receive. For the purposes of this paper, we relied on the 10-item Agentic Engagement scale that Mameli and Passini (2017) developed by building on the 5-item scale by Reeve and Tseng (2011). As compared with the original scale, the 10-item scale covers a larger variety of proactive student contributions, such as those concerning peer interactions and collaboration, and transactional aspects in relation to teacher and peers. Students answered on a 7-point Likert scale of agreement (range from 1 = I strongly disagree to 7 = I strongly agree). Sample items are “I let my teacher know what I need and want” [from the original scale by Reeve (2013)], “I defend my opinions even if they are different from those of my peers” [from the Mameli and Passini (2017) scale].

3 Results

3.1 Basic psychological needs

Based on our conceptual discussion and the consideration of the above-described Italian school setting characteristics, we first of all wanted to verify whether the dimension of autonomy could be conceived as a statistically valid measure of a basic psychological need for Italian high school students (hypothesis 1a). The 4-item internal reliability analysis of Cronbach alpha revealed a value of .64, which could be considered acceptable to some degree. However, this value is far below what Reeve and Tseng (2011) reported in a study on high school students from Taiwan (alpha = .84). Moreover, inspection of an exploratory Factor Rotated (Oblimin) Matrix conducted on all items concerning psychological needs (i.e. autonomy, competence, relatedness, (no)tension, and justice) showed that the four items of the autonomy dimension were scattered in various factors, and that three of them had moderate loadings on all factors (> .35 and < .45). In view of these data, we chose to exclude the autonomy need dimension from subsequent analysis. On the contrary, as hypothesized, the three items comprised in the (no)tension dimension showed high internal reliability (alpha = .89) and were clustered into a single factor.

Hypothesis 1b predicted that the need for justice would function as a distinct aspect of psychological needs, and as such it could be considered as an additional psychological need. To verify this hypothesis, we conducted an exploratory principal component Factor Analysis with an oblique rotation (Oblimin criterion) using the 13 items of competence, relatedness, (no)tension, and justice needs. Oblimin rotation was appropriate in this study because we assumed (see hypothesis 2b) that the factors would be correlated. Table 1 shows the results from the analysis.

As expected, four factors emerged, based on eigenvalues > 1, and these four factors accounted for 71.79% of the total variance. Only one item had a factor loading > .35 in more than a single factor. The cross-loading involved an item from the need for competence sub-scale that loaded also on the need for relatedness sub-scale.

More importantly for the purposes of the current paper, the need for justice factor explained the highest percentage of variance. Moreover, and consistently with our prediction, all four items of the justice need dimension loaded as hypothesized in factor 1, did not cross-load onto any other factor, and no item from the other factors cross-loaded into the need for justice factor.

3.2 Intercorrelations of basic psychological needs and engagement dimensions

Table 2 shows correlations among the study variables as well as statistical means, standard deviations and Cronbach’s alphas.

In contrast with our prediction (hypothesis 2a), student gender correlated (p < .01) with the need for competence, relatedness, and (no)tension (−.29 ≤ r ≥ −.12), with males obtaining higher values on these subscales than did females. In addition, and in line with expectations, gender correlated with behavioural engagement (with higher values reported by girls) but also with agentic engagement (with higher scores obtained by boys). No significant correlations were found between classroom grade and the other examined variables.

All the four basic psychological need subscales were positively intercorrelated at p < .01, with r indices ranging from .12 to .43. In line with our hypothesis (2b), the need for justice exhibited low positive associations with the need for relatedness and the need for (no)tension, while it showed a moderate correlation with the need for competence.

Again in accordance with our expectations (hypothesis 2c), all the four engagement dimensions correlated positively and significantly (p < .01) with each other, with r indices ranging from .27 to .58. More in detail, the agentic subscale, which represents the newest component of the construct, showed the lowest correlation indices with the other three components, thus confirming the absence of a possible overlap among the four dimensions.

3.3 The effects of psychological needs on engagement dimensions

Four separate hierarchical linear regression analyses were conducted in order to estimate the basic psychological needs effects on each of the four engagement dimensions. To fulfil our third research aim, we controlled for the effect of the need for justice by entering it in step two of the regressions, while the other three needs (competence, relatedness and (no)tension) were entered in the first step of each analysis.

Before proceeding with the analyses, the data were examined for outliers and for conformity with a normal distribution. Using boxplots, we identified thirteen outliers in the need subscales and four outliers in the student engagement dimensions. As all these cases were eliminated from the data, the sample size was reduced from 640 to 623 participants. For all of the variables included in our regression models, values for skewness (range from −.829 to .389) and kurtosis (range from −.829 to .371) were lower than |1|, which suggests that the distribution of the variables was adequate for the analyses. In order to reveal potential collinearity problems among the predictors, a series of Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) was computed (one for each of the four regressions). As the values of VIF (range from 1.046 to 1.331) were lower than the conventional threshold (10), it was concluded that no multicollinearity problems existed.

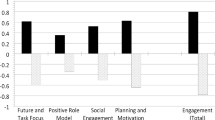

The results of the four hierarchical regression analyses are presented in Table 3.

In the first set of analyses, related to emotional engagement, hypotheses were partially confirmed. The need for competence predicted the variance of the dependent variable both in step 1 (β = .46, p < .001) and in step 2 (β = .33, p < .001). The need for justice (β = .31, p < .001) was found to be a significant predictor in step 2 of the analysis. The variables explained 22% of the variance in step one (adjusted R 2 = .22) and 29% of the variance in step two (adjusted R 2 = .29), with a statistically significant difference between the variances explained (adjusted ΔR 2 = .07, p < .001).

In the second set, pertaining to behavioural engagement, in line with hypotheses 3a and 3c the needs for competence (step 1, β = .36, p < .001; step 2, β = .29, p < .001) and for (no)tension (step 1, β = −.15, p < .001; step 2, β = −.17, p < .001) were found as significant predictors of the dependent variable in both the steps. Surprisingly, however, the association between (no)tension and behavioural engagement was negative. As regards the need for justice (β = .19, p < .001), it was found to be a significant predictor (hypothesis 3d) of behavioural engagement in step 2 of the analysis. Overall, the variables accounted for 13% of the variance in step one (adjusted R 2 = .13) and for 16% of the variance in step two (adjusted R 2 = .16), with a statistically significant difference between the variances explained (adjusted ΔR 2 = .03, p < .001).

In the third set, related to cognitive engagement, as hypothesized the need for competence was the unique predictor of the variance (adjusted R 2 = .10) both in step 1 (β = .31, p < .001) and in step 2 (β = .29, p < .001).

Finally, in the fourth set of analyses concerning agentic engagement, the needs for competence (step 1, β = .14, p < .01; step 2, β = .18, p < .001), for relatedness (step 1 and 2, β = .16, p < .001) and for (no)tension (step 1, β = .10, p < .05; step 2, β = .11, p < .01) were found to be significant predictors of the dependent variable in both steps. The need for justice (β = −.10, p < .05) was found to be a significant predictor, though negative, of agentic engagement in step 2 of the analysis. All related hypotheses were thus confirmed. Overall, the variables accounted for 7% of the variance in step one (adjusted R 2 = .07) and for 8% of the variance in step two (adjusted R 2 = .08), with a statistically significant difference between the variances explained (adjusted ΔR 2 = .01, p < .05).

4 Discussion

The purpose of this study was to investigate the relationship between basic psychological needs and student engagement in a population of Italian secondary school students. In particular, we focused on the constructs of justice need and agentic engagement, which can significantly contribute to the literature advances. As a whole, the three goals of the study were accomplished and the nine specific hypotheses were mostly verified. Key findings and implications for school psychology are discussed in the following sections.

4.1 A new list of basic needs, depending on contextual factors

The findings concerning the first goal of the study supported a view of basic needs that is partially different from the one most traditionally studied. Three aspects are to be considered. Firstly, in our Italian student population the need for autonomy does not emerge as an organized and clustered need dimension. We interpret this finding by referring to the lack of flexibility and choice characterizing the Italian school system. The moderate value of the autonomy dimension’s internal reliability seems to indicate that the participants in our study were not focused on the same issue when answering items such as: “During class I feel free” or “During class I feel I’m doing what I want to be doing”. This result is raising questions for researchers especially in view of the trends characterizing school reforms recently introduced in several countries, Italy included. Among the recommendation of the European Parliament concerning school curriculum and basic values to be achieved by European students, particular emphasis is given to the importance of student autonomy and responsibility (Gordon et al. 2009). Within this framework, the fact that our population of students does not see autonomy as a clustered dimension of basic school needs should be a matter of concern.

Secondly, we included in our selected list of basic needs the need for (no)tension. Originally developed for the AFS scale, tension has only seldom been considered in research. On the grounds of our results, we argue that it is worthwhile to take this dimension into consideration in research into adolescents. This is especially true in school settings, like the ones where we collected our data, which are highly focused on individual performance and school outcomes.

Finally, we added in the questionnaire the Teacher Justice Scale (Dalbert and Stoeber 2006) to support our argument that classroom justice is a basic psychological need. Previously studied in organizational psychology, the need for justice has never before been seen as a basic need in educational research. Our findings confirm the importance of interactional justice as a factor capable of promoting a positive attitude towards school, which is the first societal institution adolescents have to come to terms with.

4.2 Association between basic needs and student engagement

In this study, the role of gender has greater effects as compared to what was reported by Reeve and Tseng (2011). In fact, while basic needs and engagement are independent from student age, male students turn out to be more self-confident then females, especially as far as competence and relatedness are concerned, and less prone to stress and tension.

More interesting for our purposes are the associations concerning justice and agency. In the light of our correlational results, we can state that justice and agency are factors that enrich the related construct measures, those of basic needs and engagement, respectively. In particular, the need for justice resulted as a conceptually distinct basic need, although it was also related to the other needs. Moreover, agency was found to be a complementary dimension of student engagement. These results are consistent with Reeve’s (2012, 2013) insights. However, the current study has provided a literature advance in that agentic engagement was studied with a longer version of the scale originally developed by Reeve, which adds to the construct important aspects of classroom transactional dynamics. In this way, our study goes a step forward in the analysis of student engagement, which can launch future research paths.

4.3 The effects of psychological needs on engagement dimensions

Consistently with the literature, the need for competence predicted all engagement dimensions. This finding confirms the importance for students to be recognized as capable of meeting and overcoming the challenges and tasks they encounter in their learning environments (Elliot and Dweck 2005).

A negative effect was observed between (no)tension need and behavioural engagement. This suggests that the more students feel they are pressurized, the more they engage in a prompt response to teachers’ requests. In education, such a prediction might work against the adoption of student-oriented practices and the valorising of student responsibility. Quoting Niemiec and Ryan (2009), “the pressures towards specified outcomes found today in so many educational settings promotes teachers’ reliance on extrinsically focused strategies that crowd out more effective, interesting, and inspiring teaching practices that would otherwise be implemented” (p. 140).

As predicted, the need for justice positively affects behavioural and emotional engagement. In future research, justice should thus be considered as a need that promotes a positive attitude towards school (Peter and Dalbert 2010) by fostering intrinsic motivation and curiosity towards learning.

Finally, we want to stress that all considered psychological needs have impacted on agentic engagement. However, while competence, relatedness and (no)tension showed the predicted positive effects, the link between justice and agency has resulted to be negative. We were surprised by this result at first, which opens a reflection space on the issue of adolescents’ sensitivity to injustices. It is when the need for justice is challenged that students react by trying to agentically influence their learning and interactional environment (Clarke et al. 2016). This finding provides further evidence of the importance of justice and agency in the classroom that should be considered in future research.

4.4 Limitations and conclusions

We must acknowledge some limitations to this study, which are mainly of a methodological nature. First, the results are limited with respect to the sample size and the contextual factors related to the school settings where the research was conducted. Replication studies on larger and international samples are needed to broaden our results. Moreover, and beyond the purposes of this study, a confirmatory factor analysis could have provided data capable of corroborating the appropriateness of including the need for justice into the basic psychological needs list.

Notwithstanding these limitations, this study provides insights for practice and policy frameworks. Firstly, the results support the conceptualization that justice is an important basic psychological need deserving to be considered by teachers, as well as by educational researchers, on a par with the other traditional needs (Taylor 2003). By including justice as an additional psychological need, research can pave the way to a further understanding of the process by means of which youngsters develop ideas about the legitimacy of authority and become able to come to terms with justice and injustice in interpersonal relationships (Sabbagh et al. 2006). Secondly, by offering an additional perspective to engagement research, the agentic dimension adds specifications involving the transactional processes at work in the classrooms. Meant as the intention and ability to act in the world to change it and to defend one’s own positions, agentic engagement denotes a transversal competence, socially and culturally mediated (Hilppö et al. 2016), which is favoured when student needs are put at the heart of educational paths. By adopting a more nuanced view of the student engagement construct, researchers can go further in understanding the way schools can exploit their potential as vital developmental contexts for healthy adolescents (Eccles and Roeser 2011).

References

Appleton, J. J., Christenson, S. L., & Furlong, M. J. (2008). Student engagement with school: Critical conceptual and methodological issues of the construct. Psychology in the Schools, 45(5), 369–386.

Bartholomew, K. J., Ntoumanis, N., Ryan, R. M., Bosch, J. A., & Thogersen-Ntoumani, C. (2011). Self-determination theory and diminished functioning: The role of interpersonal control and psychological need thwarting. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 37(11), 1459–1473.

Cavalli, A., & Argentin, G. (2010). Gli insegnanti italiani: Come cambia il modo di fare scuola. Terza indagine dell’istituto IARD sulle condizioni di vita e di lavoro nella scuola italiana [Italian teachers: the change of teaching practices. Third IARD survey on life and work conditions in Italian schools]. Bologna: Il Mulino.

Chory-Assad, R. M. (2002). Classroom justice: Perceptions of fairness as a predictor of student motivation, learning, and aggression. Communication Quarterly, 50, 58–77.

Clarke, S. N., Howley, I., Resnick, L., & Rosé, C. P. (2016). Student agency to participate in dialogic science discussions. Learning, Culture and Social Interaction. doi:10.1016/j.lcsi.2016.01.002.

Cropanzano, R., Byrne, Z. S., Bobocel, D. R., & Rupp, D. E. (2001). Moral virtues, fairness heuristics, social entities, and other denizens of organizational justice. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 58(2), 164–209.

Dalbert, C., & Stoeber, J. (2005). The belief in a just world and distress at school. Social Psychology of Education, 8, 123–135.

Dalbert, C., & Stoeber, J. (2006). The personal belief in a just world and domain-specific beliefs about justice at school and in the family: A longitudinal study with adolescents. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 30, 200–207.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. New York, NY: Plenum.

Eccles, J. S., & Roeser, R. W. (2011). Schools as developmental contexts during adolescence. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 21, 225–241.

Elliot, A. J., & Dweck, C. S. (Eds.). (2005). Handbook of competence and motivation. New York: Guilford.

Fredericks, J. A., Blumenfeld, P. C., & Paris, A. H. (2004). School engagement: Potential of the concept, state of the evidence. Review of Educational Research, 74(1), 59–109.

Gordon, J., Halász, G., Krawczyk, M., Leney, T., Michel, A., Pepper, D., et al. (2009). Key competences in Europe: Opening doors for lifelong learners across the school curriculum and teacher education. CASE Network Reports. doi:10.2139/ssrn.1517804.

Hilppö, J., Lipponen, L., Kumpulainen, K., & Rainio, A. (2016). Children’s sense of agency in preschool: A sociocultural investigation. International Journal of Early Years Education, 24(2), 157–171.

Jelas, Z. M., Azman, N., Zulnaidi, H., & Ahmad, N. A. (2016). Learning support and academic achievement among Malaysian adolescents: The mediating role of student engagement. Learning Environments Research, 19(2), 221–240.

Lam, S., Jimerson, S., Wong, B. P. H., Kikas, E., Shin, H., Veiga, F. H., et al. (2014). Understanding and measuring student engagement in school: The results of an international study from 12 countries. School Psychology Quarterly: The Official Journal of the Division of School Psychology, American Psychological Association, 29(2), 213–232.

Lawson, M. A., & Lawson, H. A. (2013). New conceptual frameworks for student engagement research, policy, and practice. Review of Educational Research, 83(3), 432–479.

Longo, Y., Gunz, A., Curtis, G. J., & Farsides, T. (2016). Measuring need satisfaction and frustration in educational and work contexts: The need satisfaction and frustration scale (NSFS). Journal of Happiness Studies, 17(1), 295–317.

Mameli, C., & Passini, S. (2017, under revision). Development and validation of an enlarged version of the Student Agentic Engagement Scale.

Mameli, C., & Passini, S. (2017, in press). Measuring four-dimensional engagement in school: An Italian validation of the Student Engagement Scale and of the Agentic Engagement Scale. TPM—Testing, Psychometrics, Methodology in Applied Psychology.

Maslow, A. H. (1943). A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review, 50(4), 370–396.

Mayer, D. M., Bardes, M., & Piccolo, R. F. (2008). Do servant-leaders help satisfy follower needs? An organizational justice perspective. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 17(2), 180–197.

Molinari, L., Speltini, G., & Passini, S. (2013). Do perceptions of being treated fairly increase students’ outcomes? Teacher–student interactions and classroom justice in Italian adolescents. Educational Research and Evaluation, 19(1), 58–76.

Niemiec, C. P., & Ryan, R. M. (2009). Autonomy, competence and relatedness in the classroom: Applying self-determination theory to educational practice. Theory and Research in Education, 7, 133–144.

Nota, L., Soresi, S., Ferrari, L., & Wehmeyer, M. L. (2011). A multivariate analysis of the self-determination of adolescents. Journal of Happiness Studies, 12, 245–266.

Oluwatayo, A. A., Aderonmu, P. A., & Aduwo, E. B. (2015). Architecture students’ perceptions of their learning environment and their academic performance. Learning Environments Research, 18(1), 129–142.

Peter, F., & Dalbert, C. (2010). Do my teachers treat me justly? Implications of students’ justice experience for class climate experience. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 35, 297–305.

Reeve, J. (2012). A self-determination theory perspective on student engagement. In S. L. Christenson, A. Reschly, & C. Wylie (Eds.), Handbook of research on student engagement (pp. 149–172). New York: Springer.

Reeve, J. (2013). How students create motivationally supportive learning environments for themselves: The concept of agentic engagement. Journal of Educational Psychology, 105(3), 579–595.

Reeve, J., Nix, G., & Hamm, D. (2003). Testing models of the experience of self-determination in intrinsic motivation and the conundrum of choice. Journal of Educational Psychology, 95, 375–392.

Reeve, J., & Sickenius, B. (1994). Development and validation of a brief measure of the three psychological needs underlying intrinsic motivation: The AFS scales. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 54, 506–515.

Reeve, J., & Tseng, C. M. (2011). Agency as a fourth aspect of students’ engagement during learning activities. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 36(4), 257–267.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55, 68–78.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2002). An overview of self- determination theory: An organismic-dialectical perspective. In E. L. Deci & R. M. Ryan (Eds.), Handbook of self-determination research (pp. 3–33). Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press.

Sabbagh, C., Resh, N., Mor, M., & Vanhuysse, P. (2006). Spheres of justice within schools: Reflections and evidence on the distribution of educational goods. Social Psychology of Education, 9, 97–118.

Sheldon, K. M., & Gunz, A. (2009). Psychological needs as basic motives, not just experiential requirements. Journal of Personality, 77(5), 1467–1492.

Taylor, A. J. W. (2003). Justice as a basic human need. New Ideas in Psychology, 21(3), 209–219.

Vallerand, R. J. (1997). Toward a hierarchical model of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. In M. P. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 29, pp. 271–360). San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Vansteenkiste, M., Niemiec, C. P., & Soenens, B. (2010). Intrinsic versus extrinsic goal contents in self-determination theory: Another look at the quality of academic motivation. Educational Psychologist, 41, 19–31.

Voelkl, K. E. (2012). School identification. In S. L. Christenson, A. L. Reschly, & C. Wylie (Eds.), Handbook of research on student engagement (pp. 193–218). New York, NY: Springer.

Wang, M. T., & Fredricks, J. A. (2014). The reciprocal links between school engagement, youth problem behaviors, and school dropout during adolescence. Child Development, 85(2), 722–737.

Wilson, P. M., Rodgers, W. M., Blanchard, C. M., & Gessell, J. (2003). The relationship between psychological needs, self-determined motivation, exercise attitudes, and physical fitness. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 33(11), 2373–2392.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Molinari, L., Mameli, C. Basic psychological needs and school engagement: a focus on justice and agency. Soc Psychol Educ 21, 157–172 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-017-9410-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-017-9410-1