Abstract

The syllabus is often the first meaningful piece of information that students receive about a course. Previous research has indicated that students form more positive impressions of a course instructor after reading a syllabus that has been manipulated to convey information in a friendly, rather than unfriendly, tone (Harnish and Bridges in Soc Psychol Educ 14:319–330, 2011). While a friendly syllabus leads to increased perceptions of instructor warmth and approachability, it is unclear from this previous research whether a friendly syllabus may also lead to decreases in the perceived competence of the instructor. Thus, we aimed to clarify whether changes in syllabus tone affect perceptions of instructor competency. We also wished to explore the possibility of gender bias affecting these syllabus-based impressions of instructors, and to examine whether differences in syllabus tone impact the impressions formed of male and female instructors in the same way. Participants read a friendly or unfriendly course syllabus from either a male, female, or gender-unspecified instructor. Regardless of instructor gender, participants receiving the friendly syllabus perceived the instructor as being more approachable, more caring, and more motivating, but not any more or less competent, compared to those receiving the unfriendly syllabus. While instructors will be relieved to know that efforts to appear friendly on a course syllabus do not appear to negatively impact student perceptions of instructor competence, more research is needed to examine the potential role of gender bias on students’ initial impressions of instructors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The course syllabus is an important document, and one that most instructors will spend hours constructing and revising—what topics will be covered? What assessments will be used? What policies will be followed? Not only does the syllabus communicate all of the essential information about a course, but it is often the first glimpse that a student has into the course and the instructor. This first impression can have a powerful influence on student expectations and motivation (Bain 2004; Wilson and Wilson 2007). Beyond due dates and policies, students will also ‘read between the lines’ of the course syllabus to make inferences about the personality of the instructor, such as how approachable he or she is (DiClementi and Handelsman 2005; McKeachie 1986). The student may then use this information to help guide decisions about whether or not they want to remain in the course, whether they should seek help during the professor’s office hours, and so on. Thus, it is important that instructors pay attention not only to the content included in their syllabi, but to how that content is being conveyed.

Despite widespread recognition that the syllabus plays an important role in setting the tone for the course (e.g., Grunert 1997; Matejka and Kurke 1994; McKeachie 1986), empirical research on the topic has been relatively scarce. A few laboratory studies have manipulated whether or not certain information is included in a syllabus (or similar document) and examined the effects on students’ willingness to engage in certain course-related behaviors. In one study, participants in a within-subjects design read two different course descriptions, one which included a supportive statement (e.g., “If you find yourself doing poorly in the course, please come and talk to me”) and one which did not (e.g., “Please do not let yourself fall behind”). Students indicated that they would be more likely to seek help from the instructor after reading the description that included the supportive statement compared to the one that did not (Perrine et al. 1995). Another study found that the inclusion of a “welcome statement” at the top of a syllabus, where the professor expressed their enthusiasm for the material as well their availability to the students, led to students forming more positive impressions of the course and professor (LaPiene et al. 2011). Participants in the welcome statement condition also reported a greater motivation to take the course and a greater willingness to seek help from the professor, compared to the condition with no welcome statement.

Other studies have manipulated the amount of detail included in a course syllabus and have shown that students who receive a detailed course syllabus perceive greater competence in the instructor compared to those who receive a brief syllabus with only the most basic information (Jenkins et al. 2014; Saville et al. 2010). Finally, some research has compared student perceptions of learner-centered syllabi (where the focus is on the student) to more traditional instructor-centered syllabi and has found that students who receive a learner-centered syllabus form more positive impressions of the instructor on a range of important teaching characteristics, including reliability, enthusiasm, and creativity (Richmond et al. 2016). Thus it is clear that students are capable of developing expectations and forming impressions of a course and its instructor, based solely on the course syllabus.

1.1 The importance of syllabus tone

An abundance of work in social psychology has demonstrated the central importance of warm/cold judgments on impression formation (e.g., Asch 1946; Kelley 1950; Cuddy et al. 2008). The warmth dimension, alternatively referred to as morality (e.g., Wojciszke et al. 1998; Ybarra et al. 2001), communion (e.g., Ybarra et al. 2008), or ‘other-profitable’ (e.g., Peeters 2002), consists of traits that are generally interpersonal in nature, such as how friendly or trustworthy a person is. Such judgments serve a functional purpose—warmth indicates that a person should be approached, whereas coldness indicates that a person should be avoided (Fiske et al. 2006). Information about a person’s warmth appear to be particularly central to impressions when the target of the judgment has resources (e.g., knowledge, skills) that are valued by the perceiver (Scholer and Higgins 2008). Thus, we would expect that students may be particularly sensitive to information about a professor’s warmth versus coldness.

Supporting this idea, Harnish and Bridges (2011) found that students who read a syllabus manipulated to convey a friendly tone (e.g., “I welcome you to contact me outside of class and student hours”) rated the professor of the course as being more approachable and more motivated to teach the course, compared to students who read a syllabus that conveyed the same information using an unfriendly tone (e.g., “If you need to contact me outside of office hours”). Unlike much of the research reviewed above (e.g., Perrine et al. 1995; LaPiene et al. 2011), this study utilized a full-length syllabus that included all of the information typically included in an effective syllabus (e.g., course description, goals and objectives, attendance and grading policies, etc., see Suddreth and Galloway 2006; Slattery and Carlson 2005). While the same essential content was held constant and included on both syllabi (e.g., identical grading schemes, course policies, etc.), in the friendly tone condition, the wording of the information was manipulated using strategies outlined in Harnish et al. (2011), including using positive or friendly language, sharing personal information, and showing compassion.

In addition to the increased perception of instructor likeability, Harnish and Bridges (2011) also found that the students who read the warm syllabus believed that the course was going to be easier than students who read the cold syllabus. The authors’ proposed that this might be explained by the fact that likeability (or warmth) is often negatively related to competence (a contrast effect; Cuddy et al. 2004, 2005). If this is indeed the case, then it should warrant some substantial concern—many instructors may think twice about increasing their perceived warmth if it comes at the cost of their perceived competence. However, there are several reasons to believe that this may not be the case. First, the perceived difficulty of the course is at best an indirect measure of an instructor’s competence. The competence dimension (alternatively referred to as agency, Ybarra et al. 2008, or ‘self-profitable’, Peeters 2002), consists of traits that are generally intrapersonal in nature, such as how intelligent or effective a person is. The two items used to measure perceived difficulty in Harnish and Bridges (2011) were “Compared to other courses, how hard would you expect to work in a course led by this instructor?” and “Compared to other professors, how difficult do you expect this professor to be?”. Neither of these items actually asked participants to rate the intelligence or effectiveness of the instructor. Participants in the friendly syllabus condition may have simply been compelled to provide more positive ratings across the board (a halo effect; Cuddy et al. 2011; Judd et al. 2005), and most students would prefer to work less hard and have a less difficult instructor.

Second, unlike the rest of the items used in the study, these items are phrased in a comparative way, which may have affected participants’ responses and encouraged a contrast effect (though typically, contrast effects occur for judgments of groups, not individuals; Judd et al. 2005). In short, a more direct measure of instructor competence is needed in order to determine whether a friendly syllabus may actually lead to reduced perceptions of competence. In the current study, we assess perceptions of instructor competence using the professional-challenging index from Bachen et al. (1999), which consists of a range of items measuring the competence-related characteristics that students’ tend to value in university instructors.

One other potentially important limitation of the Harnish and Bridges (2011) study is that the instructor was always female, leaving open the possibility their findings may only apply to female professors. This particular limitation is important to address, since a host of evidence suggests that students often form different perceptions of male and female professors.

1.2 Gender bias in student ratings of instructors

The research on gender bias in academia typically shows that female academics are perceived as less qualified, and that their work is less valued, compared to their male counterparts (e.g., Miller and Chamberlin 2000; Monroe et al. 2008). Laboratory experiments have demonstrated that even when materials (e.g., cv, sample articles) are kept exactly the same, students will rate female professors (or the work of a female professor) less highly than males (Goldberg 1968; Paludi and Strayer 1985). Female professors have been described as being in a “double-bind” due to the fact that they must navigate what are often conflicting expectations for their behavior—e.g., that they should be both nurturing as women and authoritative as professors (MacNell et al. 2015). For example, Dion (2008) advises female instructors to establish authority by creating detailed course syllabi that clearly outline course policies and expectations for the students, while also stating that “female faculty should be careful to not appear too draconian, inflexible, or unconcerned about students because this will clash with students’ gender expectations” (p. 853). Indeed, female professors who fail to meet their gendered expectations may be punished for such violations (Sinclair and Kunda 2000), whereas male professors who exhibit non-normative gender characteristics (i.e., strong interpersonal traits) are often rewarded for such behavior (Andersen and Miller 1997). Not only is it more difficult for female professors to appear equally competent and professional as men, but they must do so while remaining interpersonally warm and approachable, or else risk being viewed as less effective instructors (Basow 1995).

A recent study by MacNell et al. (2015) manipulated the perceived gender of the instructor of an online course. One male and one female instructor each taught two different sections of an online class in which the students had no face-to-face interaction with the instructor (thus allowing for the manipulation of perceived gender). For each instructor, students in one section were told the actual gender of their instructor, whereas students in the other section were given false information about the instructors’ gender. An examination of student ratings at the end of the course revealed no differences in ratings between the actual male and female instructor, but significant differences in how the students rated the perceived male and female instructors. Specifically, when students believed that their instructor was male, they gave significantly higher ratings on items including both competence-related traits (e.g., professionalism, promptness) and warmth-related traits (e.g., respectfulness, giving praise). However, despite studies like this one that seem to make a clear case for student bias against female instructors, the larger body of research examining gender bias in student evaluations of teaching tells a complicated story and indicates that there are many potential moderating factors that can influence whether and how instructor gender influences student ratings (e.g., Basow 1995; Feldman 1992, 1993).

It is also unclear how early these gendered expectations might come into play—do students approach syllabi from male and female professors in the same way? To our knowledge, only one study has manipulated instructor gender on a course syllabus and examined students’ subsequent perceptions of the instructor. Jenkins et al. (2014) sought to investigate whether instructor gender would moderate the effect of including restrictive course boundary information (e.g., a strict late policy) on a syllabus. While the authors predicted that the inclusion of more detailed course policy information would lead to higher ratings of instructor competence for both male and female professors, they hypothesized that a female (but not a male) professor would be viewed as less supportive if she included this restrictive course policy information on a syllabus. However, the results of their study revealed no interactions between instructor gender and syllabus condition on either support or competency ratings. Interestingly, the only effect of instructor gender was a main effect for competency, with the female instructor rated as more competent than the male instructor. This (presumably unexpected) result is reported in a table, but never addressed by the authors. However, it does correspond with research by Nadler et al. (2013) who found that students who rated the competency of an instructor based solely on a photograph provided higher ratings for unknown female faculty members compared to unknown male faculty members (the effect was reversed when the students were familiar with the faculty members, see Study 1 in Nadler et al. 2013). It is clear that more research needs to be done examining the effects of instructor gender on the impressions that are formed from course syllabi.

1.3 Overview of experiment and predictions

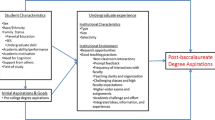

In the current study, we sought to address these key limitations of the Harnish and Bridges (2011) experiment, by examining whether the effects of syllabus tone (friendly or unfriendly) influence perceptions of instructor warmth and competence, and whether these effects would be moderated by the perceived gender of the course instructor (male, female, or unspecified). While some of our measures (approachability and motivation) were taken directly from Harnish and Bridges (2011), we also included items from Bachen et al. (1999) that were found to capture the most two important factors of the “ideal” professor: the caring-expressive teaching style (i.e., instructor warmth) and the professional-challenging teaching style (i.e., instructor competence). We predicted that compared to participants who read an unfriendly syllabus, those reading a friendly syllabus would find the instructor to be more warm, approachable, and motivating. However, we did not expect that the syllabus tone would have any significant effect on the perceived competency of the instructor. Regarding the impact of instructor gender, we tentatively predicted that the male instructor with the friendly syllabus would be viewed the most favorably, since this individual may be seen as possessing all of the best qualities of a professor (i.e., supportive and approachable, due to the friendly tone, but also knowledgeable and professional, due to their gender; e.g., Rubin 1981; Bennett 1982). While on the other hand, the female instructor with the unfriendly syllabus may be viewed the least favorably, since this individual would be violating students’ expectations that a female professor should be supportive and nurturing (e.g., Sprague and Massoni 2005; Dion 2008). However, our investigation into the effects of instructor gender was largely exploratory, given the conflicting findings reviewed above and the limited research on impressions that are formed via syllabi alone.

2 Method

2.1 Participants

One-hundred fifty undergraduate students taking the Introductory Psychology course at the University of Toronto participated in the study in exchange for an experiment credit. The study protocol received ethics approval through the Department of Psychology Delegated Ethics Review Committee prior to its initiation.

2.2 Materials

A base syllabus from an upper-level psychology course was created using the standard template syllabus given to all instructors in the department. The syllabus was a detailed, seven page document that included all of the information typically included in an effective course syllabus (e.g., course description, learning outcomes, schedule). Information about the course instructor (name and contact information) was provided at the top of the first page, and the instructors name was repeated again in the final line of the syllabus (see Table 1). In the female condition, the instructor’s name was “Dr. Jennifer Smith”, in the male condition the instructor’s name was “Dr. John Smith” and in the control (gender-unspecified) condition the instructor’s name was simply “Dr. Smith”). The tone of the syllabus was manipulated following the guidelines provided by Harnish et al. (2011), who postulated that the characteristics of a friendly tone syllabus include: (1) using positive or friendly language, (2) providing rationale for assignments, (3) sharing of personal experiences, (4) using humor, (5) conveying compassion, and (6) showing enthusiasm. For example, under the course policy section of the syllabus written in a friendly tone, it stated, “I understand that some of you may be travelling from different classes and will come in late, so please just quietly find a seat in order to avoid disrupting the class”. In contrast, the syllabus written in an unfriendly tone stated, “Repeated late arrivals to class, or talking while the instructor or other students are speaking, are disrespectful to the instructor and other class members. Be punctual and do not talk in class while the professor is speaking”. Table 1 highlights all of the differences in wording between the two syllabi. In some cases, the wording used was identical to that in Harnish and Bridges (2011). It is also worth noting that the unfriendly syllabus was not written in a particularly hostile manner, but is probably fairly representative of the type of tone many instructors take on their course syllabi.

2.3 Measures

Participants completed a 24-item professor assessment questionnaire consisting of four separate subscales that were taken or adapted from previous research and designed to measure various characteristics important to students’ evaluations of professors. Participants responded to each item on a 1 (not at all) to 5 (very much) Likert-type scale. The caring-expressive subscale (Bachen et al. 1999) was comprised of seven items (α = .88) and was intended to assess the professor’s perceived ability to encourage and support students (e.g., “The professor takes personal interest in students”). The professional-challenging subscale (Bachen et al. 1999) was comprised of eight items (α = .68) and was intended to measure perceptions of the professor’s competence (e.g., “The professor knows the field well”). The motivation subscale (Harnish and Bridges 2011) was comprised of four items (α = .88) and was intended to measure the professor’s perceived ability to motivate students (e.g., “How likely would you be to schedule a class with this professor?”). The approachability subscale (Harnish and Bridges 2011) was comprised of five items (α = .69) and was intended to measure the professor’s perceived openness and availability (e.g., “The professor is available to assist students”). Participants scores on each subscale were combined to form four separate indices.Footnote 1

2.4 Procedure

After providing their informed consent, participants completed the study individually on a computer in a private room. Participants were told that the study was interested in examining students’ perceptions of instructors based on reading a course syllabus and that they should read the syllabus carefully, since they would be asked some questions about it at the end of the experiment. Participants were randomly assigned to one of the six syllabus conditions and were allowed to take as much time as they wanted to review the syllabus. Once they were done, they completed the professor assessment questionnaire as well as a manipulation check item that asked them to report the gender of the course instructor (male, female, or unknown/unspecified). After completing the experiment, participants were debriefed and dismissed. Due to a programming error, the first ten participants did not complete the manipulation check.

3 Results

3.1 Manipulation check

A Chi square test of independence was performed to examine the relationship between the instructor gender manipulation (male, female, control) and participants’ reported gender of the instructor (male, female, unspecified/unknown). The relationship between these variables was significant, χ 2 (2, N = 140) = 55.69, p < .001, with the pattern of results indicating that the manipulation was successful. The majority of participants in the female instructor condition reported that the instructor was female (59%), whereas the majority of participants in the male instructor condition reported that the instructor was male (76%). Less than 10% of the participants in the gender-specified conditions identified the instructor with the incorrect gender label (e.g., labeling the female instructor as male). Interestingly, participants in the control (“Dr. Smith”) condition were as likely to indicate that the instructor was male as they were to indicate that the instructor’s gender was unknown (they were much less likely to indicate that the instructor was female). This corresponds with previous research showing that the role of professor is more closely associated with “male” than it is with “female” (Miller and Chamberlin 2000) and that people tend to assume someone described with the ambiguous title “Dr.” is male (Wapman and Belle 2014).

3.2 Professor assessment questionnaire

A series of 2 (tone: friendly, unfriendly) × 3 (gender: female, male, unspecified) between-subjects ANOVAs were conducted on the four dependent measures (caring-expressive index, professional-challenging index, motivation index, and approachability index). There were no main effects of gender and no significant interactions found on any of the measures. Only significant results are reported below.Footnote 2

3.2.1 Caring-expressive index

There was a significant main effect of syllabus tone, F(1, 144) = 40.19, p < .001, partial η 2 = .22. Participants who read the friendly tone syllabus perceived the professor as more encouraging (M = 3.87, SD = .58) than participants who read the unfriendly tone syllabus (M = 3.13, SD = .75).

3.2.2 Motivation index

There was a significant main effect of syllabus tone, F(1, 144) = 21.06, p < .001, partial η 2 = .13. Participants who read the friendly tone syllabus perceived the professor as more motivating (M = 3.72, SD = .66) than participants who read the unfriendly tone syllabus (M = 3.13, SD = .84).

3.2.3 Approachability index

There was a significant main effect of syllabus tone, F(1, 144) = 3.99, p = .048, partial η 2 = .03. Participants who read the friendly tone syllabus perceived the professor as more approachable (M = 4.10, SD = .51) than participants who read the unfriendly tone syllabus (M = 3.89, SD = .65).

3.2.4 Professional-challenging index

There were no differences across any of the conditions on ratings of professor competence (all ps > .15).

4 Discussion

Participants read a course syllabus from either a male, female, or gender-unspecified instructor that was manipulated to convey information using either a friendly or unfriendly tone. Compared to participants receiving the unfriendly syllabus, those in the friendly syllabus condition rated the professor higher on warmth-related traits including caring and expressiveness, approachability, and motivation. These results replicate the findings of Harnish and Bridges (2011), while also showing that these effects are not limited to female instructors. The effect of the syllabus tone manipulation did not interact with the gender of the instructor. Although we had anticipated that the male professor may benefit the most from the friendly syllabus (and that the female professor may be punished the most for the unfriendly syllabus), there was no evidence that this was the case. This is similar to the findings of Jenkins et al. (2014), who failed to find support for their hypothesis that female instructors would be viewed less positively than male instructors for including restrictive course policy information in their syllabi. Perhaps the gender of the instructor is deemed irrelevant when the syllabi contains so much other important information about a course (topics, goals, assessments, etc.), and so the students do not consider it when forming these initial judgments. Future research should examine whether instructor gender would have more of an impact under circumstances where students are given less information about the course (e.g., just a course description and the instructor name) or if the instructor gender was deemed more relevant (e.g., a gender studies course) or made more salient (e.g., if the syllabus included a photo of the instructor). Indeed, evidence suggests that context (e.g., type of course/program) matters when it comes to instructor gender bias (e.g., Basow 1995).

4.1 Limitations

Importantly, changing the tone of the syllabus did not have any effect on the perceived competency of the instructor. While Harnish and Bridges (2011) suggested that increases in perceived instructor warmth might result in decreases in perceived competency, this concern appears to be unwarranted. However, we also did not find evidence of a halo effect. One possibility is that because the syllabi used in the study contained a lot of detailed information, students relied on this information (which was held constant across conditions) as the basis on their competency judgments. It is possible that a future study using a more basic syllabus that provides fewer clues about the competency of the instructor might reveal that students receiving a friendly syllabus are more positive in their attributions regarding instructor competency compared to those receiving an unfriendly syllabus.

In general, the evidence for gender bias in student evaluations of teaching, both from naturalistic settings and laboratory experiments, paints a complicated picture (e.g., Feldman 1992, 1993). While it is promising that we failed to find any evidence of gender bias in students’ perceptions of instructors, more research needs to be done examining the impressions that students’ form of instructors via course syllabi. Gender bias in student evaluations of teaching is often contextualized (Basow and Montgomery 2005) and there is no reason to believe that this would not also be true of perceptions based on course syllabi. As has already been mentioned, one important factor to consider is the discipline or specific subject area of the course. The current study, as well as Jenkins et al. (2014), both used syllabi from upper-level psychology courses. Students may be more likely to show bias toward female faculty members in STEM disciplines or other areas (e.g., law school) where female faculty are relatively more rare and may therefore be subject to more negative stereotypes (e.g., Nadler et al. 2013). Future research should also consider the gender of the student, as previous research has shown that male and female students often differ in their ratings of male and female faculty members (Bachen et al. 1999; Basow 1995).

4.2 Conclusions

While many important questions remain, the present study provides further evidence that changes in syllabus wording can significantly impact the initial impressions that students form of both male and female instructors. It also suggests that having a more friendly syllabus will not make an instructor appear any less knowledgeable or effective. Instead, the effects appear to be entirely positive. Given what we know about the lasting impact of first impressions (e.g., Ambady and Rosenthal 1993) it is important that instructors realize that the syllabus provides students with much more than just factual information about the course. Rather, when we utter the inevitable phrase “it’s in the syllabus!”, we may also be referring to a rich set of cues about ourselves and the type of instructor the student can expect.

Notes

Subscales with Cronbach’s alpha values of less than .8 were examined for potentially problematic items (i.e., items whose removal would improve the internal reliability of the scale). No such items were identified.

Given the outcome of the manipulation check, we also ran the ANOVAs (1) using reported gender as a factor (rather than gender condition) and (2) using only those participants (n = 113) who answered the manipulation check question correctly. These analyses also revealed no main effects of gender and no interactions between gender and tone, consistent with the results reported in the main text.

References

Ambady, N., & Rosenthal, R. (1993). Half a minute: Predicting teacher evaluations from thin slices of nonverbal behavior and physical attractiveness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 64, 431–441.

Andersen, K., & Miller, E. D. (1997). Gender and student evaluations of teaching. PS Political Science and Politics, 30, 216–219.

Asch, S. E. (1946). Forming impressions of personality. Journal of Abnormal Social Psychology, 41, 258–290.

Bachen, C. M., McLoughlin, M. M., & Garcia, S. S. (1999). Assessing the role of gender in college students’ evaluations of faculty. Communication Education, 48, 193–210.

Bain, K. (2004). What the best college teachers do. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Basow, S. A. (1995). Student evaluations of college professors: When gender matters. Journal of Educational Psychology, 87, 656–665.

Basow, S. A., & Montgomery, S. (2005). Student ratings and professor self ratings of college teaching: Effects of gender and divisional affiliation. Journal of Personnel Evaluation in Education, 18, 91–106.

Bennett, S. K. (1982). Student perceptions of and expectations for male and female instructors: Evidence relating to the question of gender bias in teaching evaluation. Journal of Educational Psychology, 74, 170–179.

Cuddy, A. J. C., Fiske, S. T., & Glick, P. (2004). When professionals become mothers, warmth doesn’t cut the ice. Journal of Social Issues, 60, 701–718.

Cuddy, A. J. C., Fiske, S. T., & Glick, P. (2008). Warmth and competence as universal dimensions of social perception: The Stereotype Content Model and the BIAS Map. In M. P. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 40, pp. 61–149). New York, NY: Academic Press.

Cuddy, A. J. C., Glick, P., & Beninger, A. (2011). The dynamics of warmth and competence judgments, and their outcomes in organizations. Research in Organizational Behavior, 31, 73–98.

Cuddy, A. J. C., Norton, M., & Fiske, S. T. (2005). This old stereotype: The stubbornness and pervasiveness of the elderly stereotype. Journal of Social Issues, 61, 267–285.

DiClementi, J. D., & Handelsman, M. M. (2005). Empowering students: Class-generated course rules. Teaching of Psychology, 32, 18–21.

Dion, M. (2008). All-knowing or all-nurturing? Student expectations, gender roles, and practical suggestions for women in the classroom. PS: Political Science and Politics, 41(4), 853–856.

Feldman, K. (1992). College students’ views of male and female college teachers: Part I—evidence from the social laboratory and experiments. Research in Higher Education, 33, 317–373.

Feldman, K. (1993). College students’ views of male and female college teachers: Part II—evidence from students’ evaluations of their classroom teachers. Research in Higher Education, 34, 151–211.

Fiske, S. T., Cuddy, A. J. C., & Glick, P. (2006). Universal dimensions of social cognition: Warmth and competence. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 11, 77–83.

Goldberg, P. (1968). Are women prejudiced against women? Transaction, 5, 28–30.

Grunert, J. (1997). The course syllabus: A learning centered approach. Bolton, MA: Anker Publishing Company Inc.

Harnish, R. J., & Bridges, K. R. (2011). Effect of syllabus tone: Students’ perceptions of instructor and course. Social Psychology of Education, 14, 319–330.

Harnish, R. J., O’Brien McElwee, R., Slattery, J. M., Frantz, S., Haney, M. R., Shore, C. M., et al. (2011). Creating the foundation for a warm classroom climate: Best practices in syllabus tone. APS Observer, 24, 23–27.

Jenkins, J. S., Begeja, A. D., & Barber, L. K. (2014). More content or more policy? A closer look at syllabus detail, instructor gender, and perceptions of instructor effectiveness. College Teaching, 62, 129–135.

Judd, C. M., James-Hawkins, L., Yzerbyt, V., & Kashima, Y. (2005). Fundamental dimensions of social judgment: Understanding the relations between judgments of competence and warmth. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 89, 899–913.

Kelley, H. H. (1950). The warm-cold variable in first impressions of persons. Journal of Personality, 18, 431–439.

LaPiene, K. E., Terry F. Pettijohn II, & Linda J. Palm. (2011). An investigation of professor first impressions as a function of course syllabi. Presented at the 18th Annual Association for Psychological Science Teaching Institute, Washington, D.C.

MacNell, L., Driscoll, A., & Hunt, A. (2015). What’s in a name: Exposing gender bias in student ratings of teaching. Innovative Higher Education, 40, 291–303.

Matejka, K., & Kurke, L. B. (1994). Designing a great syllabus. College Teaching, 42, 115–117.

McKeachie, W. J. (1986). Teaching tips: A guidebook for the beginning college teacher (8th ed.). Lexington, MA: D. C. Heath.

Miller, J., & Chamberlin, M. (2000). Women are teachers, men are professors: A study of student perceptions. Teaching Sociology, 28, 283–298.

Monroe, K., Ozyurt, S., Wrigley, T., & Alexander, A. (2008). Gender equality in academia: Bad news from the trenches, and some possible solutions. Perspectives on Politics, 6, 215–233.

Nadler, J. T., Berry, S. A., & Stockdale, M. S. (2013). Familiarity and sex based stereotypes on instant impressions of male and female faculty. Social Psychology of Education, 16, 517–539.

Paludi, M. A., & Strayer, L. A. (1985). What’s in an author’s name? Differential evaluations of performance as a function of author’s name. Sex Roles, 12, 353–361.

Peeters, G. (2002). From good and bad to can and must: Subjective necessity of acts associated with positively and negatively valued stimuli. European Journal of Social Psychology, 32, 125–136.

Perrine, R. M., Lisle, J., & Tucker, D. L. (1995). Effects of a syllabus offer of help, student age, and class size on college students’ willingness to seek support from faculty. The Journal of Experimental Education, 64, 41–52.

Richmond, A. S., Slattery, J. M., Mitchell, N., Morgan, R. K., & Becknell, J. (2016). Can a learner-centered syllabus change students’ perceptions of student–professor rapport and master teacher behaviors? Scholarship of Teaching and Learning in Psychology, 2, 159–168.

Rubin, R. B. (1981). Ideal traits and terms of address for male and female college professors. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 41, 966–974.

Saville, B. K., Zinn, T. E., Brown, A. R., & Marchuk, K. A. (2010). Syllabus detail and students’ perceptions of teacher effectiveness. Teaching of Psychology, 37, 186–189.

Scholer, A. A., & Higgins, E. T. (2008). People as resources: Exploring the functionality of warm and cold. European Journal of Social Psychology, 38, 1111–1120.

Sinclair, L., & Kunda, Z. (2000). Motivated stereotyping of women: She’s fine if she praised me, but incompetent if she criticized me. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 26, 1329–1342.

Slattery, J., & Carlson, J. F. (2005). Preparing an effective syllabus: Current best practices. College Teaching, 53, 159–164. doi:10.3200/CTCH.53.4.159-164.

Sprague, J., & Massoni, K. (2005). Student evaluations and gender expectations: What we can’t count can hurt us. Sex Roles, 53, 779–793.

Suddreth, A., & Galloway, A. T. (2006). Options for planning a course and developing a syllabus. In W. Buskist & S. F. Davis (Eds.), Handbook of the teaching of psychology (pp. 31–35). Malden, MA: Wiley.

Wapman, M., & Belle, D. (2014). BU Research: A riddle reveals depth of gender bias. BU Today. Retrieved from https://www.bu.edu/today/2014/bu-research-riddle-reveals-the-depth-of-gender-bias/

Wilson, J. H., & Wilson, S. B. (2007). The first day of class affects student motivation: An experimental study. Teaching of Psychology, 34, 136–138.

Wojciszke, B., Bazinksa, R., & Jaworski, M. (1998). On the dominance of moral categories in impression formation. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 24, 1251–1263.

Ybarra, O., Chan, E., & Park, H. (2001). Young and old adults’ concerns about morality and competence. Motivation and Emotion, 25, 85–100.

Ybarra, O., Chan, E., Park, H., Burnstein, E., Monin, B., & Stanik, C. (2008). Life’s recurring challenges and the fundamental dimensions: An integration and its implications for cultural differences and similarities. European Journal of Social Psychology, 38, 1083–1092.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Waggoner Denton, A., Veloso, J. Changes in syllabus tone affect warmth (but not competence) ratings of both male and female instructors. Soc Psychol Educ 21, 173–187 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-017-9409-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-017-9409-7