Abstract

There is a burgeoning literature on wealth in the rich world. It mainly focuses on the top. This paper shows that assets can also matter for the analysis of poverty and financial vulnerability. We introduce the concept of triple precariousness, afflicting households that not only have low income but also very low or non-existent assets to draw on for consumption needs, especially liquid assets. We ask whether these households—whom we might call the truly vulnerable—have different characteristics from those that we identify as poor or needy on the basis of income based metrics. This study looks in detail at Belgium, a country that represents a particularly interesting case because households are known to have levels of household wealth that are among the highest in the Eurozone, especially around and below the median, and yet it also has a comparatively high poverty rate, measured using disposable household income, as is commonly done in poverty studies. Drawing on HFCS data, we show that households with a reference person that is young, unemployed, low educated, migrant, single, and above all a tenant are especially financially vulnerable. By contrast, our assessment of the extent and depth of financial need among the elderly—a segment of society that is at a relatively high risk of income poverty—also changes. A substantial share of income poor elderly households own significant assets. We draw out some tentative consequences of these findings for anti-poverty and redistributive policies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Who is most in need of support? That question has occupied generations of scholars, spawning an extensive literature on ways to identify and target the poor.

Poverty research is dominated by income based measures, in part on theoretical grounds but perhaps even more so on pragmatic grounds. Income as a one-dimensional measure of resources has its shortcomings but it is practical to implement because there is a relative abundance of data on people’s incomes (Atkinson et al. 2002; Marx et al. 2015). Yet, several streams of literature show that low income is an imperfect proxy for actual need. Since the way problems are defined typically provides the framework within which policy responses are developed, the definition of poverty in terms of incomes has inevitably led to policies that focus on income maintenance (Cramer et al. 2008).

In addition to a rich literature on income based measures of poverty and need there is an extensive and for the most part more recent research tradition that looks at people’s standard of living using more direct measures of living conditions and what is called “material deprivation” (Atkinson et al. 2002; Nolan and Whelan 2011). From that literature we know that low income people are not equally deprived, and therefore not in equal need for support. While there is often a substantial overlap between income poverty and material deprivation measures there are also important systematic differences. That is to say: there are some segments of the population that face significant income poverty risks but that are found to be systematically less deprived (Kus et al. 2016). That may be because they can draw on earlier accumulated financial resources that help them bridge shorter or longer periods of low income.

There is, however, a critical problem with using material deprivation measures for allocating public resources. Lacking certain goods may not be a result of lacking resources, it may just be a matter of preferences or spending patterns (Kus et al. 2016). From the perspective of effective and just redistribution this matters. If people lack certain things that are deemed to be necessities yet they have the resources available to acquire them that is important. If people do not spend their money on essential things like food and housing, for themselves and their children, this is still a significant public policy issue. But it probably requires different actions than giving those households more resources.

Lately, increasing attention is given to how wealth contributes to people’s living standards, i.e. taking into account the effect of assets and liabilities such as real estate, deposits, stocks, mortgages, etc. Such joint income-wealth measures allow to look at all resources available to households to achieve a standard of living, and hence can be considered to represent their true financial situation. Yet, up until now the focus is largely on the top (e.g. Cowell et al. 2017; Kontbay-Busun and Peichl 2014; Alvaredo et al. 2013) or the middle of the wealth distribution (e.g. Jäntti et al. 2013), while wealth remains remarkably absent in the analysis of poverty and social policy. Although there exist strong links between income and wealth, they are found to be imperfectly correlated (Jäntti et al. 2008; Skopek et al. 2012) such that income poverty is not a perfect predictor of low wealth accumulations. Those on low income might actually have a much lower need for support when substantial wealth is owned that can be used to ensure continuous consumption. In contrast, when low income is combined with low wealth or when those not considered poor according to the income dimension are paying off large amounts of debt, the depth of financial vulnerability is considerably larger.

The purpose of this paper is therefore to show that including the notions of wealth and liquidity into the framework of poverty and distributive research leads to new insights into financial vulnerability, which in turn opens up new perspectives on redistributive policies. To this end the paper uses data from the Eurosystem Household Finance and Consumption Survey (HFCS). This study looks in detail at Belgium, a country that represents a particularly interesting case because households are known to have levels of household wealth that are among the highest in the Eurozone, especially around and below the median, and yet it also has a comparatively high poverty rate, if measured using disposable household income, as is commonly done in poverty studies. Furthermore, income and wealth appear to be relatively weakly correlated (Kuypers et al. 2015; Arrondel et al. 2014; HFCN 2013b). In other words, a joint income-wealth perspective on the distribution of financial resources might have a much stronger impact on social policy in Belgium than in some other European countries.

The paper proceeds as follows. The second part discusses in more detail how the inclusion of wealth information could contribute to the inequality and poverty framework and hence the design of social policy in European countries. The data and methodology that are used are described in the third part. The following part focusses on the correlation between income and wealth using the Belgian case. Part five studies the differences in portfolio composition of poorer and richer households, particularly along the liquidity dimension, after which it is shown how the population eligible for welfare support might be affected by the inclusion of wealth and liquidity information. The last part concludes and contemplates some potential future policy courses.

2 A Joint Income-Wealth Perspective on Social Policy

Living standards are usually defined in terms of equivalised disposable household income. Monetary poverty measures, relative or anchored, also build on this metric. Since this income concept entails not only income from labour and social transfers but also income from financial investments and renting out real estate property, one may wonder why it would still be necessary to include information on assets and debt. There are several compelling reasons.

First, certain asset types generate little or no income flow, such as owner-occupied housing. Although this may be fixed by adding a measure of imputed rent to the income definition, this is not sufficient. Indeed, savings and assets also contribute to living standards above and beyond their income flow. They assure financial security because they can be used to face unexpected events (Cowell and Van Kerm 2015). In other words, when income is lost or decreased, due for example to unemployment, sickness, divorce, etc., accumulated wealth can be reduced in order to smooth out consumption (Brandolini et al. 2010). Moreover, assets can be used as collateral against which can be borrowed (this often relates to mortgage debt) (Azpitarte 2012). In contrast, when repayments of loans are large, living standards may be considerably worse than mere incomes suggest (this often relates to consumer loans and credit card debt). Hence, although there exist evident links between income and wealth, mainly through savings and borrowing constraints, the correlation between income and wealth is far from perfect (Jäntti et al. 2008, 2013; Skopek et al. 2012; Brzozowski et al. 2010). In other words, there are households with low income but high wealth and vice versa. From a different perspective assets and savings also largely affect long-term consumption and living standards, for the current as future generations. Indeed, assets allow to make purchases to move up the social ladder (Cowell and Van Kerm 2015; McKernan et al. 2012). Yet, in this paper we mainly focus on current well-being.

An important aspect of the wealth dimension is the composition of the asset portfolio. When analysing joint income-wealth measures of financial vulnerability, we need to better understand how the poor make investment decisions; i.e. in which types of assets do they invest? For instance, it is important to own sufficient liquid assets to overcome low income periods and face unexpected expenses. It is often found that poor households invest proportionally more in safe, real assets than in more risky, liquid assets. Since 1 euro means much more to a poor household than to a rich one, they are less inclined to undertake a risky investment because of the high potential losses (Friedman and Savage 1948). Campbell (2006) claims that poorer and low educated households are more likely to make investment mistakes than wealthier and higher educated households. These mistakes relate for instance to “nonparticipation in risky asset markets, underdiversification of risky portfolios and failure to exercise options to refinance consumption” (p. 1590). Cunha et al. (2011) find that the liquidity of poor households is often very low. Since illiquid assets cannot be easily converted to cash money in times of need, vulnerable households “rely too much and too frequently on the most costly forms of financing (such as overdrafts) […]” (p. 1046). Moreover, in many European countries existing policies that encourage wealth accumulation often favour illiquid over liquid assets. Examples are income tax deductions or credits for instance for mortgage repayment or private pension savings.

This paper thus asks how our view of financial need and vulnerability changes when in addition to income we take assets into account, their level and their composition, especially their liquidity.

3 Data and Methods

Up until a few years ago, evidence on the joint distribution of income and wealth was scarce, mainly as a consequence of a lack of data with regard to household wealth holdings. Initiatives such as the Luxembourg Wealth Study (LWS) and the Eurosystem Household Finance and Consumption Survey (HFCS) largely expanded research possibilities in this regard. Yet, previous studies seem to largely focus their attention towards the top (e.g. Cowell et al. 2017; Kontbay-Busun and Peichl 2014; Alvaredo et al. 2013) or the middle of the distribution (e.g. Jäntti et al. 2013). In this paper we focus primarily on the bottom using data for Belgium from the second HFCS wave which covers 2238 households surveyed in 2014 (income refers to 2013, wealth to the moment of interview).

In the HFCS the concept of net worth is used as wealth measure, which is defined as the sum of financial and real assets less liabilities.Footnote 1 It is worth noting that entitlements to public and occupational pension plans and social security funds are excluded from the HFCS wealth concept. Throughout the paper we compare low income households with intermediate and higher income households. This differentiation is made based on the deciles of equivalised income and not a poverty line as such because the HFCS only contains gross income. We define low income as those households who have an income in the bottom two deciles, the intermediate income group covers households in the middle six deciles and the high income group are those in the top two deciles. However, taking the bottom two deciles as a proxy of low income seems intuitive because the official EU At-risk-of-poverty (AROP) measure for Belgium falls in the second decile. Moreover, since households at the bottom pay little or no taxes the effect of using disposable instead of gross incomes should not be very large at the bottom, which is our main focus.

In Sect. 5 we analyse asset portfolios by liquidity. For this analysis we have grouped the assets surveyed in the HFCS into 3 categories, which is shown in Table 1. Liquidity refers to the degree of difficulty of converting an asset into cash in terms of time and effort. It thus signals how quickly a certain asset can be bought or sold on the market, therefore also called ‘marketability’. The HFCN (2013b, p. 66) regards deposits, bonds, shares, mutual funds, managed accounts and non-self-employment private business wealth as liquid assets because they can be very easily sold on a regulated market. Real estate, self-employment business wealth, private pensions and life insurances are considered to be much less tradable in the short term without incurring substantial costs, which is why we classify them as non-liquid. Vehicles and valuables are assets that can be relatively easy sold on a second-hand market, but it typically takes more effort and time to sell them than the previously mentioned liquid assets, so that we classify those separately as intermediate liquid assets.

We use the household as the unit of analysis, also the main unit of measurement in the HFCS. Studies analysing the distribution of income typically use equivalence scales to control for household size and composition in order to capture the impact of economies of scale. However, there is no general agreement on whether and how equivalence scales should be applied to wealth. In the literature the choice depends on which perspective of wealth is adopted. In this paper wealth is seen as a resource smoothing out current consumption of households (in contrast to supporting future consumption as suggested in the life cycle hypothesis). In this perspective it seems appropriate to equivalise household wealth (OECD 2013b; Jäntti et al. 2013; Brandolini et al. 2010). We use the same equivalence scale for wealth and income, although it is not clear whether the equivalence scales used for income are appropriate for the study of wealth (OECD 2013a). We opted to equivalize by the square root of household size because it is the most widely used in analyses on OECD countries, but our results remain highly robust when other (or no) equivalence scales are assumed.Footnote 2 Since our analyses are at the household level, demographic and economic characteristics mentioned in this paper always refer to the household’s reference person. We use the UN/Canberra definition of the reference person.Footnote 3

4 Income and Wealth in Belgium

We focus in this paper on the case of Belgium for a number of reasons. First, while Belgium is characterised by high overall living standards and comparatively low income inequality, poverty rates appear to be relatively high and persistent compared to other West-European countries. Indeed, inequality in market incomes is among the lowest in the world. Belgium has one of the most compressed wage distributions with a very small incidence of low paid work as well as top incomes which have not increased so dramatically as in other countries, aspects which can be largely attributed to its extensive and resilient social concertation model (Kuypers and Marx 2016). Moreover, the Belgian welfare state is also very extensive, with high levels of public spending and tax levels to match. As a consequence redistribution is considerable in Belgium, which in turn results in a relatively equal distribution of disposable income. Yet, at the same time those not included in the labour market fare worse than almost anywhere else in Europe; divisions along ethnicity, education and generation are sharp and persistent. As a result the at-risk-of-poverty rate has been close to 15% for several decades already.

Just as in most countries the inclusion of wealth in the analysis of inequality, poverty and social policy is virtually non-existent, with the notable exception of Van den Bosch (1998). For a long time this was due to the absence of suitable data. However, even now that Belgium is included in the HFCS data, the majority of studies using these data do not appear to include Belgium in their analysis. This is remarkable as HFCS figures show that Belgium has the second highest median wealth in Europe, after Luxembourg, while at the same time wealth is much less unequally distributed than in many other countries with similar wealth levels. This is probably the result of the combination of two aspects. First, Belgium was one of the first industrialised countries. Therefore, capital accumulation processes started early on and could consequently reach higher amounts (cfr. Piketty 2014). Second, the lower level of inequality may be in large part due to the high home-ownership rate of about 70–75%. Although many countries now have similar home-ownership rates, Belgium has a long tradition of being a ‘nation of homeowners’ (De Decker 2011). Since the end of the 19th century home-ownership has been promoted through various policy mechanisms including tax exemptions (i.e. ‘Woonbonus’), grants, premiums, social loans, social dwellings and social building parcels.

Finally, previous studies indicate that income and wealth are weaker correlated in Belgium than in many other countries (Kuypers et al. 2015; Arrondel et al. 2014; HFCN 2013b). Yet, there is still much more to learn about how wealth relates to income at different points in the distribution. We specifically focus on whether low income families own enough wealth to serve as a financial buffer of any real significance in times of need. As we will show in this paper, the combination of relatively high income poverty with comparatively high and equally distributed levels of net wealth has interesting implications for the assessment of who is truly financially vulnerable. These implications might be larger in countries with relatively weak income-wealth correlations than countries where the two distributions go hand in hand.

In Table 2 some key indicators of the wealth distribution are compared between households with a low (bottom 2 deciles), intermediate (middle 6 deciles) or high income (top 2 deciles). The results clearly show that in general rates of positive net worth are very high, even among low income households (89.5%). However, among those with positive wealth, median net worth is more than ten times lower among low income households than among households that have an intermediate income, and even more than 16 times compared to those with high income. Similar differences are found for gross assets. The Gini coefficients show that inequality in wealth accumulations among those with a low income is higher than among those with an intermediate or high income. Finally, results for the rank correlation coefficient indicate that low income is often accompanied by low wealth, while the correlation between income and wealth further up the distribution is slightly weaker.

Comparing medians between households with different income, however, is not enough. We should look at the full distribution of wealth by different income positions, which is depicted in Fig. 1. Again we find that wealth accumulations in the bottom income deciles are generally lower than in the top deciles. Mainly 10th percentile and median values of net worth are substantially higher when one moves up the income distribution. However, even within the first income decile there are some households that have a net worth equal to €200,000 or more.

One could wonder what the driving factor is for the large inequality in net worth among households with similar incomes. One major possibility is age as suggested by the life-cycle model of wealth accumulations (Ando and Modigliani 1963). This model implies that people borrow during the early years of adult life to fund investments and then gradually accumulate wealth until retirement, after which it goes down again. Therefore, Table 3 provides the ratio between average net wealth and average income for each income decile and separately for elderly and non-elderly households (i.e. with a household head younger or older than 65 years). We find that systematically throughout the entire income distribution wealth-to-income ratios are substantially higher for elderly than for non-elderly households. While non-elderly households own wealth equal to about 5–7.5 years of income, this is generally more than double for their elderly counterparts. This implies that among those with about the same income (i.e. belonging to the same income decile) net wealth is much larger for households with a retired household head. Yet, most noteworthy is the fact that the difference is particularly large in the bottom income decile. Hence, age plays an important role in explaining wealth inequality within income groups, but especially among those with the lowest incomes. In other words, among those traditionally considered as poor there is a share of households which can rely on substantial assets to support their consumption, while others do not have these opportunities. It is clear that living standards of the latter are much lower and therefore we can consider them as the truly vulnerable.

For further analyses in this paper we add to our three categories of income also the wealth dimension, such that we end up with nine different groups. Again, we have chosen to define the categories in terms of weighted deciles. In other words, those who have low income and low wealth are households who belong to the bottom two deciles of both the income and the wealth distribution, etc. Table 4 presents the Belgian sample sizes and weighted population shares for each of these nine joint income-wealth groups. The largest group consists of households with intermediate income and wealth, while there is a non-negligible share of households that combine high income and low wealth and vice versa.

5 Asset Portfolio Composition

In the previous part we have shown that there exist strong links between the income and wealth distributions, especially at the low end. This can be mainly attributed to borrowing and savings constraints. However, several factors can mediate the relationship between income and wealth, such as asset portfolio choices, life-cycle effects and intergenerational transfers (Jäntti et al. 2015). In this paper we focus on the first aspect. With regard to the household portfolio one can study two aspects: the number of asset types that are held, called ‘portfolio span’ by Gouskova et al. (2006) and the portfolio composition. As mentioned before, related to the latter we focus on the composition of asset portfolios along their degree of liquidity.

Figure 2 first shows the results of a linear regression of the different income and wealth groups on the number of asset types held which provides us with a measure of the heterogeneity in portfolios (the maximum number of asset types included in the HFCS is 14). We find that households having both a low income and low wealth own on average only one and a half asset types, which refers in most cases to deposits. Households in higher income and/or wealth groups are found to own more differentiated asset portfolios than their poor counterparts. For instance, those having both high income and high wealth own on average almost 6 different asset types.

We now move on to the analysis of the portfolio composition. First, the top rows of Table 5 present how households, on average, distribute their wealth over assets differing by degree of liquidity. It appears that households with low income and low wealth own a fairly large share of liquid assets (about 35.7% of total assets) compared to the other joint income-wealth groups.Footnote 4 Yet, from the perspective of precautionary savings we would prefer households with low income and low wealth to own a much higher share of liquid assets. Indeed, it should be clear that the same percentage of a low or high asset value results in very different liquidity figures. An equal liquidity share will be much more problematic for low income—low wealth households than for households which are richer in at least one of the two dimensions. As the discussion of the portfolio span indicated, liquidity of the poor often also only emanates from deposits, while their richer counterparts tend to have investments in several liquid asset sources.

Hence, in order to obtain a more accurate view on liquidity patterns we also look at the share of households having an adequate level of liquidity. In the American literature this is often defined as having liquid assets equal to three months of expenditure (see Bi and Montalto 2004 and references therein). The rationale for this is when confronted with a loss of income, liquid assets should make it possible to smooth out consumption during three months, the average duration of an unemployment spell in the US. However, in contrast to the US most European welfare states, including Belgium, have important safety nets in place such as sickness benefits, unemployment benefits and social assistance, generally with a high coverage rate. Therefore, we opted to define adequate liquidity as the amount that is deemed necessary to be able to face unexpected expenditures such as car or house repairs or large hospital bills. Indeed, social benefits generally cover normal consumption patterns, but it is often hard for those at the bottom to face unexpected costs, also for minimum wage workers. Hence, with this measure of adequate liquidity we check whether households have a sufficient liquid buffer so that they should not resort to debt, which for the poor often implies unsecured and high interest loans, which would make their situation even more precarious. In practice the threshold that is used to define adequate liquidity is taken from a question included in EU-SILC (European Union Survey on Income and Living Conditions), namely: “Can your household afford an unexpected required expense of [national specific amount] paid using its own resources?”. In Belgium this amount was equal to €1000 for the 2013 income reference period (i.e. the same as the income reference period in the 2nd HFCS wave). Based on this liquidity indicator we find that only 34.5% of households in the low income—low wealth group have sufficient liquid assets to be able to face an unexpected expense of €1000, while the majority of households with either higher income or higher wealth appear to own an adequate amount of liquid assets.

Finally, the bottom rows of Table 5 present results for the debt-to-asset ratio among the different joint income-wealth groups. As expected the debt-to-asset ratio is much higher among households with low wealth, irrespective of their income position, than those with higher wealth. Particularly interesting to note is the fact that low wealth when combined with high income is the consequence of high indebtedness. Moreover, while for all other groups the debt-to-asset ratio is higher for mortgage debt than for the non-mortgage kind, non-mortgage debt has an important impact on the situation of households in the low income—low wealth group.

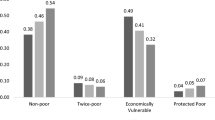

6 Characteristics of Households in Triple Precariousness

As mentioned in Table 4, 10.2% of Belgian households are considered to have low income and low wealth because they belong to the bottom two deciles in each distribution. Now we can add a third characteristic of having inadequate liquid assets to face an unexpected cost of €1000. This situation, which we label as ‘triple precariousness’, is found to affect about 6.7% of Belgian households. These households reflect about 33.3% of low income households and 65.7% of households having both low income and low wealth. In other words, an important share of low income households can rely on some wealth holdings or at least an adequate level of liquid assets, and thus are less financially deprived than their incomes suggest.

Next, we look at the profile of these households in triple precariousness. This can inform policy makers about which types of households are genuinely most in need of help and hence towards which current and possibly new social policies should be targeted. Table 6 shows the composition of households in triple precariousness compared to those with low incomes by several characteristics of the household’s reference person. The results show that households which are at high risk of being in triple precariousness are mainly those who have a reference person that is young, unemployed or inactive, low educated, migrant, single, and above all a tenant. Indeed, the most striking composition is found with regard to tenure status. Owning your main residence clearly is the most important requirement of not being in triple precariousness. Moreover, the results also show some marked discrepancies between the low income population—those conventionally labelled as poor or near-poor—and the population in triple precariousness. Compared to the demographic characteristics that are highly correlated with low income we mainly find an overrepresentation in triple precariousness of young and tenant households, while older households are clearly underrepresented.

The results of this descriptive analysis are confirmed when controlling simultaneously for different household characteristics in a logistic regression (see Table 7). Again, particularly interesting is the impact of tenure status; tenants and free users have almost 300 times more chance on belonging to the triple precariousness group, while this figure is only 1.7 in case of low income. The pseudo R square statistic suggests that these socio-demographic and economic characteristics predict the incidence of triple precariousness much more than of low income.

7 Conclusion and Policy Discussion

There is a burgeoning literature on the significance and distribution of wealth in the rich world. That is entirely justified because assets and wealth play a very large role in people’s living standards, mainly exacerbating differences between the richest and the rest. This paper shows that assets also matter greatly when making assessments of who is poor and financially vulnerable.

We introduce the concept of triple precariousness, afflicting households that not only have low income but also very low or non-existent assets to draw on for consumption needs and to face unexpected costs, especially liquid assets. We analyse whether these households—which we might call the truly vulnerable—have different characteristics from those that we identify as poor or needy on the basis of pure income based metrics.

In an analysis for Belgium, we show that the profile of those that we identify as the truly vulnerable—households with low income, few assets, especially few liquid assets—is different from those that we identify as poor purely on the basis of income, as is conventionally done. Households with a reference person that is young, unemployed or inactive, low educated, migrant, single, and above all a tenant, are especially vulnerable in terms of their overall financial situation. By contrast, our assessment of the extent and depth of financial need among the elderly—a segment of society that is at a relatively high risk of income poverty—also changes drastically. A substantial share of income poor elderly households own significant assets.

Such results probably hold social policy consequences. First, with respect to existing policies, which are typically focused on income, a distinction between those who can provide in their own income maintenance during difficult periods by drawing on assets and those who cannot surely seems relevant. Yet it is not entirely straightforward in what way. Obviously, state resources could be spent more effectively and possibly more efficiently if social benefits were to be primarily targeted at those who are the most vulnerable, i.e. households with low income, low wealth and inadequate liquidity. Another potential implication is that less is spent on income poor households that have substantial resources. Yet certain assets may not be immediately or fully fungible, or only at a significant cost. It also seems unreasonable to expect people to sell certain types of assets, such as the family home, to meet income needs that are a fraction of the total value of that asset, although policies such as reverse mortgages might provide a solution here. On the other hand, it also does not appear entirely fair that non-contributory income support is provided to people with very significant wealth holdings. How assets should affect eligibility calculations and how aspects like liquidity, divisibility etc. are to matter in this respect clearly requires further thought and analysis.

Second, looking at issues of inequality and poverty within a joint income-wealth framework may lead us to think further about introducing new types of policies. In particular, European welfare states now often focus on the redistribution of market incomes, while this paper has shown that there is also an important (and increasing) need for distributing wealth resources more evenly. Over the years several authors have made proposals in the direction of supporting asset accumulation among the poor. For instance, Atkinson (2015) argues that there should be a capital endowment for all paid at adulthood, Ackermann and Alstott (1999, 2004) made similar arguments striving for a ‘stakeholder society’, and Sherraden (1991, 2001) has been advocating pro-poor asset-building policies for three decades already. Although currently several European countries fiscally encourage the ownership of real estate and financial assets, these policies are typically unavailable to poor households (McKernan and Sherraden 2008). It certainly appears that such policies have not been used to their fullest potential to address financial vulnerability and poverty, although the benefits of doing so may be large and numerous (see Sherraden 1991). Furthermore, these policies have traditionally favoured the ownership of illiquid assets such as real estate over more liquid asset types. Looking at how we can include the poor into these types of policies is an interesting direction for future research.

However, there are some risks involved in finding a correct balance between these two policy options. When eligibility for social benefits are means-tested against private wealth, it could result in so-called ‘saving traps’, i.e. households could be discouraged to save so as to remain below the asset threshold (Alcock and Pearson 1999; Fehr and Uhde 2013; Jäntti et al. 2008; Sefton et al. 2008). Hence, while the aim of new asset policies would be to encourage the poor to accumulate assets, proper means-testing punishes them for owning such assets. The trade-off between the two will also be an interesting aspect to consider for future research.

Notes

Wealth and net worth are used interchangeably throughout this paper.

Results of this validation exercise are not included in this paper, but are available upon request.

According to this definition the reference person is determined based on the following sequential steps:

one of the partners in a registered or de facto marriage, with dependent children.

one of the partners in a registered or de facto marriage, without dependent children.

a lone parent with dependent children.

the person with the highest income.

the eldest person.

(HFCN 2013a, pp. 16–17).

It is worth noting that the largest share in total assets highly depends on where the household’s main residence and other real estate property are classified because they typically constitute the largest shares of net worth. Indeed, we find for all households that non-liquid assets have the dominant share in total assets. However, our results remain robust even when real estate is not included.

References

Ackermann, B., & Alstott, A. (1999). The stakeholder society. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Ackermann, B., & Alstott, A. (2004). Why stakeholding? Politics & Society, 32(1), 41–60.

Alcock, P., & Pearson, S. (1999). Raising the poverty plateau: The impact of means-tested rebates from local authority charges on low income households. Journal of Social Policy, 28(3), 497–516.

Alvaredo, F., Atkinson, A. B., Piketty, T., & Saez, E. (2013). The top 1 percent in international and historical perspective. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 27(3), 3–20.

Ando, A., & Modigliani, F. (1963). The ‘life cycle’ hypothesis of saving: Aggregate implications and tests. American Economic Review, 53(1), 55–84.

Arrondel, L., Roger, M., & Savignac, F. (2014). Wealth and income in the Euro area. Heterogeneity in households’ behaviours? ECB working paper no. 1709.

Atkinson, A. B. (2015). Inequality. What can be done?. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Atkinson, A., Cantillon, B., Marlier, E., & Nolan, B. (2002). Social Indicators: The EU and social inclusion. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Azpitarte, F. (2012). Measuring poverty using both income and wealth: A cross-country comparison between the U.S. and Spain. Review of Income and Wealth, 58(1), 24–50.

Bi, L., & Montalto, C. P. (2004). Emergency funds and alternative forms of saving. Financial Services Review, 13(2), 93–109.

Brandolini, A., Magri, S., & Smeeding, T. (2010). Asset-based measurement of poverty. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 29(2), 267–284.

Brzozowski, M., Gervais, M., Klein, P., & Suzuki, M. (2010). Consumption, income and wealth inequality in Canada. Review of Economic Dynamics, 13(1), 52–75.

Campbell, J. Y. (2006). Household finance. Journal of Finance, 61(4), 1553–1604.

Cowell, F., Nolan, B., Olivera, J., & Van Kerm, P. (2017). Wealth, top incomes and inequality. In K. Hamilton & C. Hepburn (Eds.), National wealth: What is missing, why it matters (pp. 175–206). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Cowell, F., & Van Kerm, P. (2015). Wealth inequality: A survey. Journal of Economic Surveys, 29(4), 671–710.

Cramer, R., Sherraden, M., & McKernan, S.-M. (2008). Policy implications. In S.-M. McKernan & M. Sherraden (Eds.), Asset building and low income families (pp. 221–237). Washington D.C.: The Urban Institute Press.

Cunha, M. R., Lambrecht, B. M., & Pawlina, G. (2011). Household liquidity and incremental financing decisions: Theory and evidence. Journal of Business Finance & Accounting, 38(7&8), 1016–1052.

De Decker, P. (2011). Understanding housing sprawl: The case of Flanders, Belgium. Environment and Planning—Part A, 43(7), 1634–1654.

Eurosystem Household Finance and Consumption Network. (2013a). The Eurosystem Household Finance and Consumption survey—Methodological report for the first wave. ECB statistics paper no 1, p. 112.

Eurosystem Household Finance and Consumption Network. (2013b). The Eurosystem Household Finance and Consumption survey—Results from the first wave. ECB statistics paper no 2, p. 112.

Fehr, H., & Uhde, J. (2013). Means-testing retirement benefits in the UK: Is it effcient? Working paper, University of Wuerzburg.

Friedman, M., & Savage, L. J. (1948). The utility analysis of choices involving risk. Journal of Political Economy, 56(4), 279–304.

Gouskova, E., Juster, F. T., & Stafford, F. P. (2006). Trends and turbulence: Allocations and dynamics of American family portfolios, 1984–2001. In E. N. Wolff (Ed.), International perspectives on household wealth (pp. 295–326). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Jäntti, M., Sierminska, E., & Smeeding, T. (2008). The joint distribution of household income and wealth. Evidence from the Luxembourg wealth study. OECD social, employment and migration working papers No. 65. Paris: OECD Publishing.

Jäntti, M., Sierminska, E., & Van Kerm, P. (2013). The joint distribution of income and wealth. In J. C. Gornick & M. Jäntti (Eds.), Income inequality. Economic disparities and the middle class in affluent countries (pp. 312–333). Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press.

Jäntti, M., Sierminska, E., & Van Kerm, P. (2015). Modelling the joint distribution of income and wealth. Research on Economic Inequality, 23, 301–327.

Kontbay-Busun, S., & Peichl, A. (2014). Multidimensional affluence in income and wealth—A cross-country comparison using the HFCS. ZEW discussion paper 14–124.

Kus, B., Nolan, B., & Whelan, C. T. (2016). Material deprivation and consumption. In D. Brady & L. M. Burtin (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of the social science of poverty (pp. 577–601). New York: Oxford University Press.

Kuypers, S., & Marx, I. (2016). Social concertation and middle class stability in Belgium. In D. Vaughan-Whitehead, Europe’s disappearing middle class? Evidence from the world of work (pp. 112–159). Edward Elgar.

Kuypers, S., Marx, I., & Verbist, G. (2015). Joint patterns of income and wealth inequality in Belgium. Report prepared for the National Bank of Belgium.

Marx, I., Nolan, B., & Olivera, J. (2015). The welfare state and antipoverty policy in rich countries. In A. Atkinson & F. Bourguignon (Eds.), Handbook of income distribution (pp. 2063–2139). Amsterdam: Elsevier.

McKernan, S.-M., Ratcliffe, C., & Williams Shanks, T. (2012). Is poverty incompatible with asset accumulation? In P. N. Jefferson (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of the economics of poverty (pp. 463–493). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

McKernan, S.-M., & Sherraden, M. (2008). Asset building and low income families. Washington D.C.: The Urban Institute Press.

Nolan, B., & Whelan, C. T. (2011). Poverty and deprivation in Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

OECD. (2013a). OECD guidelines for micro statistics on household wealth. Paris: OECD Publishing.

OECD. (2013b). OECD framework for statistics on the distribution of household income, consumption and wealth. Paris: OECD Publishing.

Piketty, T. (2014). Capital in the twenty-first century. Harvard: Harvard University Press.

Sefton, J., van de Ven, J., & Weale, M. (2008). Means-testing retirement benefits: Fostering equity or discouraging savings? The Economic Journal, 118(528), 556–590.

Sherraden, M. W. (1991). Assets and the poor: A new American welfare policy. New York: M.E. Sharpe Inc.

Sherraden, M. (2001). Asset-building policy and programs for the poor. In T. Shapiro, & E. Wolff, Assets for the poor. The benefits of spreading asset ownership (pp. 302–323). New York: Russel Sage Foundation.

Skopek, N., Kolb, K., Buchholz, S., & Blossfeld, H. P. (2012). Income rich—asset poor? The composition of wealth and the meaning of different wealth components in a European comparison. Berliner Journal für Soziologie, 22(2), 163–187.

Van den Bosch, K. (1998). Poverty and assets in Belgium. Review of Income and Wealth, 44(2), 215–228.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

The authors gratefully acknowledge financing from BELSPO for the CRESUS project (BR/121/A5/CRESUS). We would like to thank participants of the CSP Seminar, the 2014 Spring Meeting of the ISA RC28, the 2014 FISS Conference and the 2015 SASE Conference for their helpful comments and suggestions on earlier drafts of this paper. Remaining errors are all ours.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kuypers, S., Marx, I. The Truly Vulnerable: Integrating Wealth into the Measurement of Poverty and Social Policy Effectiveness. Soc Indic Res 142, 131–147 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-018-1911-6

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-018-1911-6