Abstract

Over a half century of research has identified constellations of rigid, sexist, and hegemonic beliefs about how men should think, feel, and behave within Western societies (i.e., traditional masculine ideologies; TMI). However, there is a dearth of literature examining why people adhere to TMI. Within in this study, we examined TMI from an identity perspective. Specifically, we focused on the concepts of identity exploration and identity commitment to identify distinct identity statuses based on Marcia’s (1966) identity status theory. Our sample (N = 1136) was composed of college and community cisgender women (n = 890) and cisgender men (n = 244) in the United States. We conducted a Latent Profile Analysis (LPA) to allow identity status groups to naturally emerge based on levels of identity exploration and commitment. A three-class solution emerged as the best fit to the data. Individuals in the foreclosed status (i.e., high commitment but low exploration) scored higher on all seven TMI domains and lower on feminist attitudes compared to those who were high in exploration but low in identity commitment (i.e., identity moratorium). However, there was no difference between individuals high in both identity commitment and exploration (i.e., identity achievement) and the identity foreclosed individuals on feminist attitudes and three of seven dimensions of TMI. Implications and future directions are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

A half century of research indicates that internalized beliefs about what constitutes appropriate thoughts, feelings, and behaviors for men (i.e., masculinity ideology) are prevalent, measurable, and potentially predictive of a variety of personal and relational outcomes in both men and women (Levant, 2011; Levant & Richmond, 2016; Thompson & Bennett, 2015). There are likely as many different masculinity ideologies in the world as there are individuals to enact them; however, researchers have noted that a core set of rigid, traditional, and sexist beliefs about men tend to be highly interrelated (Levant & Richmond, 2016; McDermott et al., 2017). Such traditional masculinity ideology (TMI) is believed to represent endorsement of beliefs that men should be emotionally stoic, dominant, tough, heterosexual, hypersexual, self-reliant, mechanically skilled, and generally the opposite of anything considered feminine (Levant et al., 2013). For example, one prominent instrument assessing TMI, the Male Role Norms Inventory-Short Form (MRNI-SF; Levant et al., 2013) provides scores for seven separate but interrelated subscales mapping onto these domains: Restrictive Emotionality, Dominance, Toughness, Negativity Toward Sexual Minorities, Importance of Sex, Self-Reliance Through Mechanical Skills, and Avoidance of Femininity. Moreover, both cisgender men and cisgender women endorse TMI. Indeed, several measurement invariance-equivalence studies indicate that measures of TMI are capturing the same latent constructs in cisgender men and cisgender women (McDermott, Wolfe et al., 2021; McDermott et al., 2020; Borgogna & McDermott, 2022).

TMI is also a central component of the masculine gender role strain paradigm (Pleck, 1995, 2017), a leading theory describing how restrictive masculinity ideologies can be dysfunctional when rigidly endorsed (Levant & Richmond, 2016; Wong et al., 2010). In line with the gender role strain paradigm, numerous researchers have linked TMI to a variety of personal and relational problems, as well as prejudicial attitudes and beliefs (Gerdes et al., 2018). However, most investigations have focused on outcomes or correlates of TMI. Comparatively fewer investigations have examined why men and women endorse TMI. Such information could inform clinical interventions for individuals who are experiencing gender role strain due to rigid internalization of TMI. Accordingly, we assert that TMI, which represents an especially rigid perspective of what men should be and do (Levant & Richmond, 2016), may be explained by factors that promote ideological rigidity. Specifically, drawing on Marcia’s (1966) identity status theory, the present study examined differences in the way individuals commit to or explore their beliefs in relation to TMI and its correlates.

Identity Status Theory

Marcia’s (1966) identity status theory is a foundational theory in developmental psychology and has received considerable attention as a framework to help understand how individuals come to identify with certain attitudes and beliefs (Bilsker et al., 1988; Cieciuch & Topolewska, 2017; Marcia, 1966). Building upon Erikson’s (1959/1994) identity stages, Marcia (1966) postulated there are four outcomes for occupational, religious, and political identities: foreclosure (i.e., committing to a belief without critical exploration), moratorium (i.e., actively exploring one’s beliefs), diffusion (i.e., not actively exploring or committing to one’s beliefs), and achievement (i.e., committing to beliefs after having engaged in a period of exploration).

Contemporary perspectives of Marcia’s theory focus on two underlying identity development processes—identity commitment and identity exploration—that determine an individuals’ identity status (Cieciuch & Topolewska, 2017; Kroger et al., 2010; Marcia, 1966). Specifically, different levels of identity exploration and commitment are believed to correspond to each of the four identity statuses (e.g., Balistreri et al., 1995): foreclosure (low exploration and high commitment), moratorium (high exploration and low commitment), diffusion (low exploration and low commitment), and achievement (high exploration and high commitment). Researchers have expanded Marcia’s initial theoretical model to identity transitions across the lifespan (Arneaud et al., 2016; Carlsson et al., 2015; Fadjukoff et al., 2016) and to additional identity dimensions such as sex roles (Balistreri et al., 1995; Bartoszuk & Pittman, 2010) and sexual orientation (Ciliberto & Ferrari, 2009; Worthington et al., 2008). Moreover, Balistreri and colleagues (1995) identified that identity exploration or commitment in one domain (e.g., politics) correlated strongly with identity exploration or commitment in another domain (e.g., sex roles). Thus, identity exploration and identity commitment are believed to be global mechanisms governing identity development in many interrelated domains across the lifespan (Arneaud et al., 2016; Carlsson et al., 2015; Fadjukoff et al., 2016).

Identity Status Theory and TMI

Although no evidence is available in the extant literature to link TMI to identity exploration and commitment directly, the history of examining gender roles as a critical aspect of one’s identity spans nearly 40 years, starting when Grotevant & Adams (1984) developed one of the first self-report measures to assess identity statuses. Still, researchers examining the possible gender role consequences of identity commitment and exploration have relied entirely on measures such as the Bem Sex Role Inventory (BSRI; Balistreri et al., 1995; Bem, 1974) or the Personality Attributes Questionnaire (PAQ; Helmreich et al., 1981; Prager, 1983). These instruments may not capture true gender role beliefs but rather personality characteristics that have been labeled as “masculine” or “feminine” (Auster & Ohm, 2000; Fernández & Coello, 2010). Thus, the present study is (to the best of our knowledge) the first to examine identity status in relation to adherence to actual gender role beliefs.

TMI captures a particular set of beliefs about men representing the dominant (i.e., hegemonic) masculinity in Western culture (Levant & Richmond, 2016). Therefore, it may be most salient to individuals in a foreclosed identity status. Foreclosed individuals have, in theory, committed to an identity without critically thinking about it. The result is a rigid, unquestioning, and conformist approach to identity-salient beliefs (Marcia, 1966; Zacarés & Iborra, 2015).

Our review of the literature suggests that both cultural and individual difference factors may be key to a potential link between identity foreclosure and TMI. First, TMI captures the dominant (i.e., white, heterosexual) masculinity in Western culture (Connell & Messerschmidt, 2005). In other words, TMI represents the hegemonic masculinity which all individuals in the United States are exposed to via socialization (Levant & Richmond, 2016). TMI, therefore, may be most prevalent among individuals who have not seriously questioned the default, traditional gender role expectations of men. Indeed, in the only published model of adult gender role ideology development (i.e., the gender role journey; O’Neil 2015), critical exploration is positioned as one of the primary mechanisms moving individuals away from acceptance of traditional gender roles (i.e., TMI) toward more flexible gender role beliefs over time.

Second, foreclosed individuals often display a variety of rigid and intolerant characteristics (Zacarés & Iborra, 2015) such as greater authoritarianism (see Ryeng et al., 2013 for a meta-analysis) and prejudice (Soenens et al., 2005). Several researchers have linked endorsement of traditional gender role stereotypes to similar rigid and intolerant perspectives (Duncan et al., 1997; Goodnight et al., 2014; Stefurak et al., 2010). More specifically, because TMI represents an especially rigid perspective of gender, it is often positively associated with a variety of intolerant attitudes (Gerdes et al., 2018) among men and women (McDermott et al., 2020). Thus, foreclosed individuals and those that endorse TMI may share a common characteristic of ideological rigidity – a byproduct of a tendency to swallow whole identity-salient attitudes and values without first digesting them through critical exploration (Zacarés & Iborra, 2015).

In summary, while researchers have not yet examined the links between identity development processes and TMI, evidence from related studies and relevant theory suggests that individuals who have foreclosed on their identity may be particularly predisposed to endorse TMI. That is, foreclosed individuals likely have had less opportunities to move away from the default, hegemonic perspective of men (i.e., TMI). Likewise, foreclosed individuals and those that endorse TMI may share similar individual difference characteristics that promote adherence to rigid gender role stereotypes. Drawing on these two interconnected lines of reasoning, a testable possibility is that individuals who have foreclosed on various aspects of their identity by committing strongly without exploration will endorse the most TMI compared to individuals who have engaged in more identity exploration (i.e., those in identity moratorium or with an achieved identity).

Another testable possibility is that foreclosed men and women will report the lowest levels of feminist perspectives of gender. Specifically, feminism, which promotes equality and gender role flexibility (Eagly et al., 2012; Halpern & Perry-Jenkins, 2016), is the antithesis of TMI (Levant & Richmond, 2016). Because feminism is not the default (i.e., starting point) of gender role ideology like TMI (O’Neil, 2015), more endorsement of feminist ideology may signal the presence of greater levels of critical gender role exploration. For example, some evidence suggests that participating in a workshop focused on gender role exploration may facilitate greater commitment to feminist ideals (O’Neil & Carroll, 1988). Likewise, individuals who have been exposed to feminism via family or coursework are likely to identify as feminists themselves (Nelson et al., 2008). Therefore, greater exploration of one’s gender role may help move individuals away from TMI and towards more flexible and egalitarian perspectives of gender (O’Neil, 2015).

The Present Study

To date, researchers have yet to examine the reasons men and women endorse TMI. To address this gap, the present study tested whether their relative degree of identity exploration or commitment provides some clue as to why men and women endorse rigid TMI versus feminist perspectives. Given the conceptual links between TMI and ideological rigidity, we were especially interested in the foreclosed identity status. Based on Marcia’s (1966) theory of identity status and the available literature, we expected that men and women classified as foreclosed would endorse the most TMI compared to men and women in the other identity statuses (hypothesis 1). In addition to greater TMI, we hypothesized (hypothesis 2) that individuals classified in a foreclosed status would report significantly weaker feminist attitudes compared to individuals in the other statuses.

Method

Procedures and participants

Data were gathered from a previously published dataset examining TMI in relation to political conservatism (McDermott et al., 2021). After institutional approval from The University of Akron, participants responded to a secure online survey distributed to the institution’s psychology subject pool, Craigslist, and social media. Participants in the psychology subject pool were compensated with course credit. All other participants were entered into a raffle to win one of four $50.00 gift cards.

Initially, 1338 individuals participated. However, after removing 202 participants who failed attention check items, study participants (N = 1136) included 244 men (21.5%), 890 women (78.3%), and two participants who did not report their gender. As originally reported by McDermott and colleagues (2021), the overall mean age was 25.52 (SD = 10.45). Most participants were introductory psychology students from The University of Akron (n = 546), Craigslist users (n = 376), or other social media users (e.g., Facebook, n = 29). Several participants (n = 185) did not indicate their survey origin due to a coding mistake that was corrected after a few weeks of survey responses. Table 1 displays additional participant demographic information.

Measures

A variety of validated self-report measures were used in the present study. Only the assessment of TMI and participant demographics overlapped between the present study and McDermott and colleagues (2021).

Demographics and validity checks

Upon completion of the survey, participants answered demographic items covering a range of characteristics (see Table 1). Additionally, participants were exposed to three validity checks (e.g., “Thank you for paying attention, please select option 2”) interspersed throughout the survey to flag inattentive responding.

Traditional masculinity ideology

TMI was assessed via the Male Role Norms Inventory-Short Form (MRNI-SF; Levant et al., 2013). The MRNI-SF is comprised of 21 items, consisting of statements describing beliefs about acceptable behavior for men (e.g., “When the going gets tough, men should get tough.”). Participants rate how strongly they agree or disagree with each statement using a Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). The MRNI-SF can generate a total score and domain-specific subscale scores, with higher scores indicating greater endorsement of traditional views of male gender roles. For the present study, we used the seven domain specific scores. The seven subscales include: Avoidance of Femininity (AoF; e.g., “Men should watch football games instead of soap operas.”), Negativity Toward Sexual Minorities (NTSM; e.g., “Homosexuals should never marry.”), Self-Reliance Through Mechanical Skills (SRMS; e.g., “Men should have home improvement skills.”), Toughness (T; e.g., “It is important for a man to take risks, even if he might get hurt.”), Dominance (Dom; e.g., “The President of the US should always be a man.”), Importance of Sex (IoS; e.g., “Men should always like to have sex.”), and Restrictive Emotionality (RE; e.g., “A man should never admit when others hurt his feelings.”). Items are summed and then averaged for each subscale, respectively. Prior research provides evidence for the reliability and construct validity of each domain of TMI (c.f. Gerdes et al., 2018). Previously reported internal consistency estimates ranged from 0.75 to 0.90 for subscale dimensions (Levant et al., 2013). In the current study, the seven subscales produced coefficient alphas ranging from 0.77 to 0.90.

Identity development processes

The Ego Identity Process Questionnaire (Balistreri et al., 1995) was used to measure identity exploration and identity commitment, respectively. The EIPQ is a 32-item instrument that evaluates one’s exploration of and commitment to a general sense of identity, defined as the shared variance among the following identity domains: occupation, religion, politics, general values, family roles, friendships, dating, and sex roles. Items consist of statements such as, “I have considered different political views thoughtfully” (exploration), and “my ideas about men’s and women’s roles will never change” (commitment). Participants rate their level of agreement with each item on a 6-point scale (1 = strongly disagree to 6 = strongly agree). Balisteri and colleagues (1995) provided initial support for the two-factor (exploration and commitment) structure of the EIPQ. Of note, although the EIPQ contains questions specific to sex role identity exploration (2 items) and sex role commitment (2 items), the instrument is not intended to be scored at an identity domain level, and the internal consistency of these two items would not support examining them separately. Rather, the instrument provides a global assessment of general identity exploration and commitment. Several researchers have provided evidence supporting the construct validity of the EIPQ exploration and commitment scores (Balistreri et al., 1995; Phillips, 2009; Schwartz, 2004; Schwartz et al., 2009). Twelve of the 32 items are reversed scored, and total scores are summed and then averaged for the exploration and commitment dimensions separately. Balistreri et al., (1995) reported internal consistency estimates of 0.75 for identity commitment and 0.76 for identity exploration. Internal consistency coefficient alphas were 0.79 for identity exploration and 0.81 for identity commitment in the present study.

Feminist ideology

The Liberal Feminist Attitude and Ideology Scale (LFAIS; Morgan 1996) was used to measure feminist attitudes. Morgan (1996) developed the original LFAIS, which is comprised of 60 items scored on a 6-point scale (1 = strongly disagree to 6 = strongly agree), with several items reverse scored, and measures several domains of feminist attitudes along with a total score (cf., Morgan 1996). Within the same validation study, Morgan (1996) also created a 10-item short form of the LFAIS, which was used for this study. A sample item is the following: “Women should be considered as seriously as men as candidates for the Presidency of the United States.” Morgan (1996) found good construct, convergent, and discriminant validity for both forms of the LFAIS and the internal consistency for the long and short forms were 0.94 and 0.81, respectively. The LFAIS short form internal consistency was 0.84 in the present study.

Analysis plan

To test whether individuals in a foreclosed status evidenced the most endorsement of TMI and feminist ideology, we used Latent Profile Analysis (LPA; see Collins & Lanza 2010 for a review). Specifically, different levels of identity exploration and commitment are believed to underly each identity status (Marcia, 1966). A foreclosed identity (i.e., high commitment but low exploration) was the focus of the study and our research hypotheses. However, rather than relying on traditional clustering methods based on ad-hoc distance measures (i.e., cluster analysis) or a median split to create a foreclosed group, we used LPA to identify subgroups of individuals based on their responses to continuous measures of identity exploration and identity commitment. Thus, we allowed a group with foreclosed identity characteristics to naturally emerge from our data through a finite mixture model.

LPA specifies a categorical latent variable with an unknown number of levels and uses maximum likelihood estimation to assign cases to classes (i.e., clusters of people). Unlike less sophisticated and rigorous clustering methods, LPA also yields statistical fit indices and tests to determine whether adding or removing a class represents an improvement in model fit (Collins & Lanza, 2010). Specifically, we followed recommended LPA practices (Meyer & Morin, 2016; Morin et al., 2018) by first saving the factor scores of the exploration and commitment latent variables via a pooled CFA. We then examined the LPA, starting by testing a one-class solution and adding one additional class iteratively. Based on prior research that has found up to five distinct identity statuses via measures of identity exploration and commitment (Marttinen et al., 2016; Meeus et al., 2012; Syed & Seiffge-Krenke, 2013), we tested up to five classes.

To determine the relative change of fit between each model, we consulted the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), and the sample size-adjusted Bayesian Information Criterion (ABIC). Lower scores on each of these indices indicate a better fit to the data (Collins & Lanza, 2010). The best class solution is evident when either the AIC, BIC, or ABIC demonstrate that a model with one additional class no longer represents a marked improvement in model fit. LPA also provides statistical tests to determine whether the class solution could be better represented with one less class (i.e., the adjusted Lo–Mendell–Rubin Ratio Test; LMRT-adjusted; Lo et al., 2001). If the LMRT is statistically significant, then the specified model is retained over a model with one less class. A non-significant p value for the LMRT, therefore, indicates that the solution has stopped improving, and a model with one less class should be retained. Statisticians have argued that the BIC and the bootstrapped LMRT are particularly relevant to determining the best class solution (Nylund et al., 2007). Finally, based on recommended best practice (Collins & Lanza, 2010), we prioritized solutions that were interpretable based on Marcia’s theory.

Once a stable (i.e., the best log likelihood value replicates regardless of the number of random starts) and interpretable solution was obtained, we examined the classification entropy as an initial check of reliability of the classifications. A model in which all cases have a 100% probability of being assigned to their respective classes would produce an entropy value of one. Although there is no set cutoff score, entropy values approaching or exceeding 0.70 are considered desirable (Collins & Lanza, 2010). Next, we examined mean differences on all measures using a BCH procedure (Bakk & Vermunt, 2016). That is, because all class solutions are likely to have some degree of unreliability, any analysis with those classes needs to account for classification entropy (Asparouhov & Muthén, 2021). The BCH procedure tests mean differences across classes while also accounting for classification error. Results of the BCH procedure were used to label each class and to test our hypotheses.

Results

Preliminary analyses

Prior to conducting our primary analyses, we screened data for missing values and tested for univariate and multivariate outliers and violations of normality. Given the potential for gender differences in identity exploration and commitment that could impact our LPA, we also explored our data to determine if we needed to control for gender. All participants completed at least 80% of each instrument. Additionally, less than 2% of the sample had missing values on any MRNI-SF, EIPQ, or LFAIS item. Thus, missingness was handled at the model level using a full-information estimator in our measurement model. Next, tests of univariate outliers revealed that most univariate outliers were minimal (n < 10). However, approximately 2% of the sample evidenced z-scores greater than 3.29 on the Dominance and Toughness subscales of the MRNI-SF. Multivariate outliers (i.e., significant Mahalanobis distances) were also minimal (n = 34, 3% of the sample). Given the low percentage of outliers and given that none were extreme or due to coding mistakes, we did not remove outlier cases. Next, skew indices for each variable of interest were calculated and revealed a moderate positive skew for MRNI-SF scores, whereas EIPQ and LFAIS scores were normally distributed. Table 2 provides the correlations among all variables, scale means, and standard deviations. Finally, a series of t-tests revealed no noteworthy gender differences in identity commitment on the EIPQ, though women were slightly more likely to explore their identities compared to men (d = 0.15, p = .03).

Table 3 presents the results of the LPA tested across five classes in Mplus Version 8.1 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2017). The information criteria, particularly the BIC, suggested a three-class solution. Likewise, the LMRT suggested a three-class solution, as evidenced by non-significant p-values for the fourth and fifth classes, respectively. This solution held after running the model with twice the number of random start values. Interestingly, the bootstrapped version of the LMRT did not support a clear class structure, though this is a common occurrence in LPA (Bengt O. Muthén, 2009; Bengt O. Muthén, 2017). Nevertheless, considering the convergence of the BIC and LMRT, entropy, and the interpretability of the structure, we retained the 3-class solution.

Using the BCH procedure for testing the equality of means in LPA, we examined differences in identity exploration and commitment across each of the three classes. Table 4 displays the means and standard errors of all classes using the BCH procedure. All means for exploration and commitment, respectively, were significantly different across each of the three classes. Based on these results, we labeled class 1 (n = 253) Identity Moratorium, because these individuals had some of the lowest levels of commitment but the highest levels of identity exploration. In other words, individuals in this class had not yet committed to their identity but were actively exploring their identity at the time of the study . Next, we labeled individuals in the second class (n = 752) as Identity Achieved, because this group reported the second highest levels of both identity exploration and identity commitment. Unlike the other identified classes, these individuals’ scores suggested they had both committed to and explored their identity. Finally, we labeled individuals in the third class (n = 131) as Identity Foreclosed, because these individuals reported the lowest levels of identity exploration but the highest levels of identity commitment. Indeed, this is the classic configuration of exploration and commitment scores consistent with identity foreclosure (Ryeng et al., 2013). Of note, we did not find evidence for an identity diffusion class (low exploration and low commitment), but most individuals in the sample would have already gone through a period of some identity exploration and/or commitment by virtue of their age (Verschueren et al., 2017).

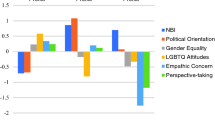

Next, we added TMI and feminist ideology to the BCH procedure for testing the equality of means using the auxiliary variable function in Mplus. We also tested gender to determine if men or women were over or underrepresented in any of the classes using a modified categorical version of the BCH procedure. Women were more likely to be classified into the moratorium (OR = 1.81) and achieved classes (OR = 1.51); however, there were no gender differences in the likelihood of being classified into the foreclosed class (OR = 1.00). Table 4 displays the results of the BCH procedure for all continuous variables. Consistent with our first hypothesis, individuals classified as Identity Foreclosed endorsed the most Avoidance of Femininity, Negativity Toward Sexual Minorities, Self-Reliance through Mechanical Skills, and Dominance scores on the MRNI-SF compared to all other identity statuses represented. Consistent with our second hypothesis, the Identity Foreclosed group also evidenced higher levels of all TMI domains and lower levels of feminist ideology than the Identity Moratorium class. However, contrary to both hypotheses, there were no significant differences in Restrictive Emotionality, Importance of Sex, Toughness, and feminist ideology when comparing foreclosed individuals to the Identity Achieved group.

Discussion

The present study examined whether the degree to which men and women critically explore or commit to various identities may help explain why they endorse rigid beliefs about men’s gender roles. Specifically, drawing on Marcia’s (1966) theory of identity statuses, we focused on a foreclosed identity (i.e., committing to one’s identity without exploration) in relation to TMI and feminist attitudes. We hypothesized that individuals in a foreclosed identity would report the most TMI (hypothesis 1) and the least feminist attitudes (hypothesis 2) compared to individuals in the other identity statuses.

The present findings suggest an identity development framework may be useful in understanding TMI and its correlates. Not only did a group of individuals naturally emerge from our data fitting the classic characteristics of a foreclosed identity, but these individuals reported the highest scores on four of the seven MRNI-SF subscales compared to individuals in the Identity Achieved class. Additionally, individuals in the Identity Foreclosed class reported significantly higher scores on all seven domains of TMI, as well as lower feminist ideology, than individuals classified in the Identity Moratorium class. Thus, our results partially supported our first and second hypotheses and suggest that highly committing to one’s identity without much critical exploration may explain why some cisgender men and women gravitate toward greater TMI and less feminist ideology. These results are consistent with the Gender Role Journey-based assertion that hegemonic masculinity, such as the beliefs represented by TMI, may be the cultural default for most individuals, and exploration may help move people away from these beliefs. Moreover, our findings are consistent with a multitude of studies linking less identity exploration to constructs conceptually and empirically associated with greater TMI such as more authoritarianism and less openness to experience (Bartoszuk & Pittman, 2010; Frisén & Wängqvist, 2011; Pastorino et al., 1997; Peterson & Zurbriggen, 2010; Solomontos-Kountouri & Hurry, 2008). Our results, therefore, point toward a connection between identity foreclosure and TMI and suggest that future researchers should continue to delineate the cultural and individual difference factors that may help explain this connection.

Although our results supported the proposition that identity foreclosed individuals would report significantly more TMI and less feminist ideology compared to individuals actively exploring their identity (i.e., identity moratorium), feminist ideology and three dimensions of TMI evidenced no differences between a foreclosed and an achieved identity. Thus, although TMI and identity foreclosure may share a common root of rigidity, not all dimensions of TMI may be related to a foreclosed identity. These findings are in line with research indicating the importance of understanding TMI as a set of interrelated (but somewhat distinct) domains with different outcomes (Levant et al., 2013, 2015). Our findings also suggest that some individuals commit to certain traditional conceptions of gender even after engaging in identity exploration. Such findings highlight the ubiquity of TMI in the United States (Levant & Richmond, 2016).

Given that the present results provided only partial support for our hypotheses, further research is needed to understand the role of identity development processes in relation to specific aspects of TMI. Our findings may provide some clues to guide this work. For example, apart from Self-Reliance through Mechanical Skills scores, the TMI domains most prevalent among foreclosed men and women (i.e., Avoidance of Femininity, Dominance, and Negativity Toward Sexual Minorities) are exemplars of the concept of hegemonic masculinity (McDermott et al., 2017, 2019). Specifically, masculinity is hegemonic when it serves to maintain men’s power over women and other men, particularly racial and sexual minority men (Connell & Messerschmidt, 2005). Avoidance of Femininity (i.e., beliefs that men should avoid anything feminine) and Dominance (i.e., beliefs that men should be in positions of power and authority) disproportionately represent masculinity hegemony over women compared to other dimensions of TMI (McDermott et al., 2019). Likewise, Negativity Toward Sexual Minorities may capture masculinity hegemony over sexual minority men. Thus, one possibility for future research is that identity foreclosure may be most relevant to masculinity ideology reflecting a particularly rigid, dogmatic, and authoritarian perspective of gender but may be less relevant to more mild or innocuous gender role beliefs.

Another finding warranting further exploration is that individuals in the Identity Moratorium class reported significantly less TMI and more feminist ideology compared to individuals with foreclosed identities. These results highlight the importance of identity exploration. In this way, our findings are consistent with a gender role journey perspective (O’Neil, 2015), because individuals who engage in the most identity exploration may be especially predisposed to reject TMI and embrace feminist perspectives. Therefore, one possibility for future research is that identity exploration may be a particularly important factor in determining one’s adult gender role ideology, possibly because identity exploration may represent a curious and open-minded perspective about identity-relevant information.

Limitations & Directions for Future Research

The present study is not without limitations. Additional research is needed to support our findings through replications and to explicitly test theoretical assumptions not addressed in this report. For instance, given that LPA is fundamentally an exploratory and a correlational analysis, our results will need to be replicated in other samples. The correlational nature of the study is particularly important to note because the present findings cannot be used to infer whether a foreclosed identity causes greater endorsement of TMI. Indeed, researchers should attempt to replicate and extend the present study via prospective longitudinal designs to help determine the actual driving forces behind the relationship between identity foreclosure and TMI. Such research could help clarify whether specific acts of identity exploration or commitment at specific times may help explain later endorsement of TMI, as well as how individual difference factors (e.g., authoritarianism) may develop in relation to identity exploration and endorsement and TMI. Relatedly, our sample was generally homogeneous with respect to age, sexual orientation, gender identity, and racial identity. Longitudinal or cohort studies could be used to better understand the development and endorsement of TMI across the lifespan. Future researchers should also examine the present model in more diverse samples that were not well represented in the present study. McDermott & Schwartz (2013) found that racial and sexual minority men were more likely to question traditional gender roles than White men, for instance. Additionally, we focused on a measure of TMI capturing one’s attitudes and beliefs about men. Future research should consider other measures related to traditional masculinity such as conformity to masculine role norms (CMNI-30; Levant et al., 2020), as well as broader definitions of masculinity such as those represented by various masculinity archetypes in our culture (see Smiler 2006 for discussion and empirical test of a variety of different masculinity symbols). These measures will provide greater insight into more diverse definitions of masculinity ideology other than those revolving around the dominant, hegemonic forms of masculinity assessed via TMI.

Practice Implications

Our findings inform clinical practice by shedding light on the underlying identity factors associated with TMI. While most men reject TMI or are psychologically and relationally healthy, TMI remains a prominent contributor to a variety of psychological and relational problems among men and the women in their lives (American Psychological Association, 2018). This is also reflected in our LPA results, with the Identity Foreclosed class representing the smallest percentage of the total sample and the Identity Achieved class representing the largest group. Thus, for a minority of individuals who are especially rigid or dogmatic in their TMI adherence and embodiment, conceptualizing TMI from an identity perspective may provide novel avenues for clinical intervention. Drawing on Marcia’s identity theory, a logical starting place is to engage in critical exploration of one’s gender role and other aspects of identity. When a clinician suspects the presence of rigid or dogmatic TMI that is clinically relevant, structured (i.e., using worksheets or other activities) or unstructured (i.e., Socratic questioning or interviewing) interventions designed to explore such ideology may help reveal a foreclosed identity. Moreover, such interventions may help individuals critically deconstruct restrictive messages about gender (O’Neil, 2015). Likewise, considering that the present study yielded no differences in the likelihood of being classified in a foreclosed status between men and women, clinicians are encouraged to be mindful of identity foreclosure and TMI in their female-identified clients when clinically relevant.

Conclusions

The present study sought to examine TMI and feminist ideology from an identity perspective. Our results generally confirmed our hypotheses that individuals in a foreclosed identity would report the most TMI and the least feminist ideology, particularly compared to individuals who are actively exploring their identity without much commitment. These findings suggest that men and women who have highly committed to their identity with very little critical exploration may be especially supportive of TMI and be opposed to feminist ideology. Likewise, exploring one’s identity may be particularly salient to whether one endorses or rejects TMI. At the same time, some dimensions of TMI evidenced no significant differences between foreclosed and achieved identity statuses, suggesting some individuals endorse TMI even after engaging in some critical exploration. This latter finding warrants further attention through additional research. Indeed, we hope these results serve as a call to continue to broaden research on TMI to identify the underlying processes that may explain why individuals adhere to these rigid and restrictive beliefs.

References

American Psychological Association, Boys and Men Guidelines Group (2018). APA guidelines for psychological practice with boys and men. https://www.apa.org/about/policy/psychological-practice-boys-men-guidelines.pdf

Arneaud, M. J., Alea, N., & Espinet, M. (2016). Identity development in Trinidad: Status differences by age, adulthood transitions, and culture. Identity: An International Journal of Theory and Research, 16(1), 59–71. https://doi.org/10.1080/15283488.2015.1121818

Asparouhov, T., & Muthén, B. (2021). Auxiliary variables in mixture modeling: Using the BCH method in Mplus to estimate a distal outcome model and an arbitrary secondary model. https://www.statmodel.com/examples/webnotes/webnote21.pdf

Auster, C. J., & Ohm, S. C. (2000). Masculinity and femininity in contemporary American society: A reevaluation using the Bem Sex-Role Inventory. Sex Roles, 43(7–8), 499–528. https://doi.org/10.1037/t00748-000

Bakk, Z., & Vermunt, J. K. (2016). Robustness of stepwise latent class modeling with continuous distal outcomes. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 23(1), 20–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705511.2014.955104

Balistreri, E., Busch-Rossnagel, N. A., & Geisinger, K. F. (1995). Development and preliminary validation of the Ego Identity Process Questionnaire. Journal of Adolescence, 18(2), 179–192. https://doi.org/10.1006/jado.1995.1012. psyh

Bartoszuk, K., & Pittman, J. F. (2010). Profiles of identity exploration and commitment across domains. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 19(4), 444–450. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-009-9315-5

Bem, S. L. (1974). The measurement of psychological androgyny. Journal of Counseling and Clinical Psychology, 42(2), 155–162. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0036215

Bengt, O., Muthén (2009, July 31). I assume the 2-class model has 0 p values for both as well. BLRT and LMR agree well in the [Comment on the blog post “Diverging LMR and BLRT p-values”]. http://www.statmodel.com/discussion/messages/13/4529.html?1249068377

Bengt, O., Muthén (2017, February 22). I would go by BIC in these cases. The problem of BIC not showing a minimum can be solved by [Comment on the blog post “Diverging LMR and BLRT p-values”]. http://www.statmodel.com/discussion/messages/13/4529.html?1249068377

Bilsker, D., Schiedel, D., & Marcia, J. (1988). Sex differences in identity status. Sex Roles: A Journal of Research, 18(3–4), 231–236. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00287792

Borgogna, N. C., & McDermott, R. C. (2022). Is traditional masculinity ideology stable over time in men and women? Psychology of Men & Masculinities. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1037/men0000393

Carlsson, J., Wängqvist, M., & Frisén, A. (2015). Identity development in the late twenties: A never ending story. Developmental Psychology, 51(3), 334–345. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038745

Cieciuch, J., & Topolewska, E. (2017). Circumplex of identity formation modes: A proposal for the integration of identity constructs developed in the Erikson–Marcia tradition. Self and Identity, 16(1), 37–61. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298868.2016.1216008

Ciliberto, J., & Ferrari, F. (2009). Interiorized homophobia, identity dynamics and gender typization Hypothesizing a third gender role in Italian LGB individuals. Journal of Homosexuality, 56(5), 610–622. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918360903005279

Collins, L. M., & Lanza, S. T. (2010). Latent class and latent transition analysis: With applications in the social, behavioral, and health sciences. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Connell, R. W., & Messerschmidt, J. W. (2005). Hegemonic masculinity: Rethinking the concept. Gender & Society, 19(6), 829–859. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891243205278639

Duncan, L. E., Peterson, B. E., & Winter, D. G. (1997). Authoritarianism and gender roles: Toward a psychological analysis of hegemonic relationships. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 23(1), 41–49. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167297231005

Eagly, A. H., Eaton, A., Rose, S. M., Riger, S., & McHugh, M. C. (2012). Feminism and psychology: Analysis of a half-century of research on women and gender. American Psychologist, 67(3), 211–230. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027260

Fadjukoff, P., Pulkkinen, L., & Kokko, K. (2016). Identity formation in adulthood: A longitudinal study from age 27 to 50. Identity, 16(1), 8–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/15283488.2015.1121820

Fernández, J., & Coello, M. T. (2010). Do the BSRI and PAQ really measure masculinity and femininity? The Spanish Journal of Psychology, 13(2), 1000–1009. https://doi.org/10.1017/S113874160000264X

Frisén, A., & Wängqvist, M. (2011). Emerging adults in Sweden: Identity formation in the light of love, work, and family. Journal of Adolescent Research, 26(2), 200–221. https://doi.org/10.1177/0743558410376829

Gerdes, Z. T., Alto, K. M., Jadaszewski, S., D’Auria, F., & Levant, R. F. (2018). A content analysis of research on masculinity ideologies using all forms of the Male Role Norms Inventory (MRNI). Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 19(4), 584–599. https://doi.org/10.1037/men0000134

Goodnight, B. L., Cook, S. L., Parrott, D. J., & Peterson, J. L. (2014). Effects of masculinity, authoritarianism, and prejudice on antigay aggression: A path analysis of gender-role enforcement. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 15(4), 437–444. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0034565

Grotevant, H. D., & Adams, G. R. (1984). Development of an objective measure to assess ego identity in adolescence: Validation and replication. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 13(5), 419–438. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02088639

Halpern, H. P., & Perry-Jenkins, M. (2016). Parents’ gender ideology and gendered behavior as predictors of children’s gender-role attitudes: A longitudinal exploration. Sex Roles, 74(11), 527–542. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-015-0539-0

Helmreich, R. L., Spence, J. T., & Wilhelm, J. A. (1981). A psychometric analysis of the Personal Attributes Questionnaire. Sex Roles, 7(11), 1097–1108. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00287587

Kroger, J., Martinussen, M., & Marcia, J. E. (2010). Identity status change during adolescence and young adulthood: A meta-analysis. Journal of Adolescence, 33(5), 683–698. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2009.11.002

Levant, R. F. (2011). Research in the psychology of men and masculinity using the gender role strain paradigm as a framework. The American Psychologist, 66(8), 765–776. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0025034

Levant, R. F., Hall, R. J., & Rankin, T. J. (2013). Male Role Norms Inventory–Short Form (MRNI-SF): Development, confirmatory factor analytic investigation of structure, and measurement invariance across gender. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 60(2), 228–238. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0031545

Levant, R. F., Hall, R. J., Weigold, I. K., & McCurdy, E. R. (2015). Construct distinctiveness and variance composition of multi-dimensional instruments: Three short-form masculinity measures. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 62(3), 488–502. https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000092

Levant, R. F., McDermott, R., Parent, M. C., Alshabani, N., Mahalik, J. R., & Hammer, J. H. (2020). Development and evaluation of a new short form of the Conformity to Masculine Norms Inventory (CMNI-30). Journal of Counseling Psychology, 67(5), 622–636. https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000414

Levant, R. F., & Richmond, K. (2016). The gender role strain paradigm and masculinity ideologies. In Y. J. Wong, S. R. Wester, Y. J. Wong (Ed), & S. R. Wester (Ed) (Eds.), APA handbook of men and masculinities. (2014-41535-002; pp. 23–49). American Psychological Association. https://libproxy.usouthal.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=psyh&AN=2014-41535-002&site=ehost-live&scope=site

Lo, Y., Mendell, N. R., & Rubin, D. B. (2001). Testing the number of components in a normal mixture. Biometrika, 88(31), 767–778. https://doi.org/10.1093biomet/88.3.76

Marcia, J. E. (1966). Development and validation of ego-identity status. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 3(5), 551–558. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0023281

Marttinen, E., Dietrich, J., & Salmela-Aro, K. (2016). Dark shadows of rumination: Finnish young adults’ identity profiles, personal goals and concerns. Journal of Adolescence, 47(2016), 185–196. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2015.10.024

McDermott, R. C., Borgogna, N. C., Hammer, J. H., Berry, A. T., & Levant, R. F. (2020). More similar than different? Testing the construct validity of men’s and women’s traditional masculinity ideology using the Male Role Norms Inventory-Very Brief. Psychology of Men & Masculinities, 21(4), 523–532. https://doi.org/10.1037/men0000251

McDermott, R. C., Brasil, K. M., Borgogna, N. C., Barinas, J. L., Berry, A. T., & Levant, R. F. (2021). The politics of men’s and women’s traditional masculinity ideology in the United States. Psychology of Men & Masculinities, 22(4), 627–638. https://doi.org/10.1037/men0000367

McDermott, R. C., Levant, R. F., Hammer, J. H., Borgogna, N. C., & McKelvey, D. K. (2019). Development and validation of a five-item Male Role Norms Inventory using bifactor modeling. Psychology of Men and Masculinities, 20(4), 467–477. https://doi.org/10.1037/men0000178

McDermott, R. C., Levant, R. F., Hammer, J. H., Hall, R. J., McKelvey, D. K., & Jones, Z. (2017). Further examination of the factor structure of the Male Role Norms Inventory-Short Form (MRNI-SF): Measurement considerations for women, men of color, and gay men. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 64(6), 724–738. https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000225

McDermott, R. C., & Schwartz, J. P. (2013). Toward a better understanding of emerging adult men’s gender role journeys: Differences in age, education, race, relationship status, and sexual orientation. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 14(2), 202–210. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028538

McDermott, R. C., Wolfe, G., Levant, R. F., Alshabani, N., & Richmond, K. (2021). Measurement invariance of three gender ideology scales across cis, trans, and nonbinary gender identities. Psychology of Men & Masculinities, 22(2), 331–344. https://doi.org/10.1037/men0000286

Meeus, W., van de Schoot, R., Keijsers, L., & Branje, S. (2012). Identity statuses as developmental trajectories: A five-wave longitudinal study in early-to-middle and middle-to-late adolescents. Journal of Youth Adolescence 41(2012), 1008–1021. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-011-9730-y

Meyer, J. P., & Morin, A. J. S. (2016). A person-centered approach to commitment research: Theory, research, and methodology. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 37(4), 584–612. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2085

Morgan, B. L. (1996). Putting the feminism into feminism scales: Introduction of a Liberal Feminist Attitude and Ideology Scale. Sex Roles: A Journal of Research, 34(5–6), 359–390. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01547807

Morin, A. J. S., Bujacz, A., & Gagné, M. (2018). Person-Centered Methodologies in the Organizational Sciences: Introduction to the Feature Topic. Organizational Research Methods, 21(4), 803–813. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428118773856

Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (1998–2017). Mplus user’s guide (8th ed.). Muthén & Muthén

Nelson, J. A., Liss, M., Erchull, M. J., Hurt, M. M., Ramsey, L. R., Turner, D. L., & Haines, M. E. (2008). Identity in action: Predictors of feminist self-identification and collective action. Sex Roles, 58(2008), 721–728. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-007-9384-0

Nylund, K. L., Asparouhov, T., & Muthén, B. O. (2007). Deciding on the number of classes in latent class analysis and growth mixture modeling: A Monte Carlo simulation study. Structural Equation Modeling, 14(4), 535–569. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705510701575396

O’Neil, J. M. (2015). Men’s gender role conflict: Psychological costs, consequences, and an agenda for change. American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/14501-000

O’Neil, J. M., & Carroll, M. R. (1988). A gender role workshop focused on sexism, gender role conflict, and the gender role journey. Journal of Counseling & Development, 67(3), 193–197. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6676.1988.tb02091.x

Pastorino, E., Dunham, R. M., Kidwell, J., Bacho, R., & Lamborn, S. D. (1997). Domain-specific gender comparisons in identity development among college youth: Ideology and relationships. Adolescence, 32(127), 559–577.

Peterson, B. E., & Zurbriggen, E. L. (2010). Gender, sexuality, and the authoritarian personality. Journal of Personality, 78(6), 1801–1826. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.2010.00670.x

Phillips, T. M. (2009). Does social desirability bias distort results on the Ego Identity Process Questionnaire or the Identity Style Inventory? Identity: An International Journal of Theory and Research, 9(1), 87–94. https://doi.org/10.1080/15283480802579474. https://doi-org.libproxy.usouthal.edu/

Pleck, J. H. (1995). The gender role strain paradigm: An update. In R. F. Levant, W. S. Pollack, R. F. Levant (Eds), & W. S. Pollack (Eds.), A new psychology of men (pp. 11–32). Basic Books.

Pleck, J. (2017). Forward: A brief history of the psychology of men and masculinities. In R. F. Levant & Y. J. Wong (Eds.), The psychology of men and masculinities (pp. XI—XIX). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/00000023-000

Prager, K. J. (1983). Identity status, sex-role orientation, and self-esteem in late adolescent females. The Journal of Genetic Psychology, 143(1983), 159–167. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221325.1983.10533547

Ryeng, M. S., Kroger, J., & Martinussen, M. (2013). Identity status and authoritarianism: A meta-analysis. Identity: An International Journal of Theory and Research, 13(3), 242–252. https://doi.org/10.1080/15283488.2013.799434

Schwartz, S. J. (2004). Brief report: Construct validity of two identity status measures: The EIPQ and the EOM-EIS-II. Journal of Adolescence, 27(4), 477–483. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2004.03.005. https://doi-org.libproxy.usouthal.edu/

Schwartz, S. J., Zamboanga, B. L., Wang, W., & Olthuis, J. V. (2009). Measuring identity from an Eriksonian perspective: Two sides of the same coin? Journal of Personality Assessment, 91(2), 143–154. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223890802634266

Smiler, A. P. (2006). Living the image: A quantitative approach to delineating masculinities. Sex Roles: A Journal of Research, 55(9–10), 621–632. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-006-9118-8

Soenens, B., Duriez, B., & Goossens, L. (2005). Social-psychological profiles of identity styles: Attitudinal and social-cognitive correlates in late adolescence. Journal of Adolescence, 28(1), 107–125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2004.07.001

Solomontos-Kountouri, O., & Hurry, J. (2008). Political, religious and occupational identities in context: Placing identity status paradigm in context. Journal of Adolescence, 31, 241–258. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2007.11.006

Stefurak, T., Taylor, C., & Mehta, S. (2010). Gender-specific models of homosexual prejudice: Religiosity, authoritarianism, and gender roles. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, 2(4), 247–261. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021538

Syed, M., & Seiffge-Krenke, I. (2013). Personality development from adolescence to emerging adulthood: Linking trajectories of ego development to the family context and identity formation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 104(2), 371–384. https://doi.org/10.1037/a003/0070

Thompson, E. H. Jr., & Bennett, K. M. (2015). Measurement of masculinity ideologies: A (critical) review. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 16(2), 115–133. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038609

Verschueren, M., Rassart, J., Claes, L., Moons, P., & Luyckz, K. (2017). Identity statuses throughout adolescence and emerging adulthood: A large-scale study into gender, age, and contextual differences. Journal of Belgian Association for Psychological Science, 57(1), 32-42. https://doi.org/10.5334/pb.348

Wong, Y. J., Steinfeldt, J. A., Speight, Q. L., & Hickman, S. J. (2010). Content analysis of Psychology of Men & Masculinity (2000–2008). Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 11(3), 170–181. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0019133

Worthington, R. L., Navarro, R. L., Savoy, H. B., & Hampton, D. (2008). Development, reliability, and validity of the Measure of Sexual Identity Exploration and Commitment (MOSIEC). Developmental Psychology, 44(1), 22–33. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.44.1.22

Zacarés, J. J., & Iborra, A. (2015). Self and identity development during adolescence across cultures. In J. D. Wright (Ed.), International encyclopedia of the social & behavioral sciences (pp. 432–438). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-097086-8.23028-6

Funding

Research reported in this publication was not funded.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors agree to be accountable for ensuring the integrity and accuracy of this work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interests disclosures

All authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

McDermott, R.C., Brasil, K.M., Borgogna, N.C. et al. Traditional Masculinity Ideology and Feminist Attitudes: The Role of Identity Foreclosure. Sex Roles 87, 211–222 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-022-01302-4

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-022-01302-4