Abstract

Self-objectification, body surveillance, and body shame have been widely researched in the context of early attachment and interpersonal relationships; however, no research to date had been conducted on the role of romantic attachment styles. In the current study, we examined the role of romantic attachment in women’s (n = 193) experiences of body surveillance and body shame. We hypothesized a model in which anxious and avoidant attachment positively predicted body shame through the intervening variable of body surveillance and then revised the model to incorporate a direct path from anxious attachment to body shame. The revised model had good fit to our data. Our research suggests that body surveillance and body shame are outcomes of insecure romantic attachment in adulthood. While this was true for both insecure attachment styles, anxious attachment, in particular, was a stronger predictor of both body surveillance and body shame. We discuss the potential implications of these findings in the context of prior research on self-objectification and relationship contingency, self-esteem, and rejection fears.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Proposed by Fredrickson and Roberts [12], objectification theory is grounded in the media’s pervasive sexualization of the female body and the impact of the ‘male gaze.’ The negative effects of objectification on women are numerous and have been studied for decades [1]. Objectification impacts women of various ages [38], ethnicities [3, 11] and sexual orientations [9, 18, 43]. Individuals who internalize the sociocultural sexualization of the body are likely to engage in self-objectification, viewing their body from an observer’s perspective [12].

Self-objectification is often operationalized as body surveillance [25], which involves the habitual evaluation of one’s body in comparison to cultural standards of attractiveness [22]. Women who engage in body surveillance focus on how their bodies look and may disregard how their bodies feel or function [22].

The effects of self-objectification are wide-ranging. Self-objectification has been found to lead to problems with mental health and social well-being [4, 21]. Depressive symptomatology is a commonly studied outcome of self-objectification [7, 30]. Research also indicates that self-objectification is a predictor of disordered eating [16, 26, 28, 40]. Other negative outcomes experienced by those who self-objectify include poor body esteem [20, 21], decreased psychological well-being [21], increased anxiety [24, 30], increased likelihood of substance abuse [5], and decreased academic and cognitive performance [13–15].

However, the act of viewing one’s body from the perspective of an outsider may not be inherently harmful. Many of the negative outcomes associated with habitual self-objectification are believed to be the result of internalized body shame, a sense of inadequacy resulting from the inability to achieve the unattainable cultural standards of attractiveness endorsed by Western media (e.g., very thin, young, muscular [22]). In this way, self-objectification or body surveillance is believed to indirectly lead to negative outcomes through the intervening variable of body shame.

Women’s anticipation of the male gaze and internalization of beauty norms are central to objectification theory. While most women experience objectification, several individual circumstances influence the extent to which women internalize the observer’s perspective. One factor that plays a role in the likelihood that a woman will succumb to self-objectification is the quality of her relationships.

The relationships that influence body concern and self-objectification begin as early as childhood. Research indicates that early social feedback, negative peer evaluation and teasing influence the development of girls’ perceptions of their bodies [6]. Families also play a role in shaping the experience of self-objectification and body dissatisfaction [21, 31], and insecurely attached preadolescent girls are more likely to be preoccupied with thinness and body shape [19].

These patterns continue into adulthood. One relationship factor that may be worth considering is romantic attachment in adulthood. There are two dimensions to attachment styles in adulthood: anxiety and avoidance. In the context of adult attachment, “anxiety” is the extent to which an individual experiences fears of abandonment or rejection in close relationships, whereas “avoidance” may manifest as a fear of intimacy or a reluctance to trust in others [2]. While people who are securely attached tend to exhibit appropriate levels of self-sufficiency and closeness in their relationships, those with insecure attachment styles generally trend toward the extremes of the anxiety-avoidance continuum in their relationships. Insecure attachment in adulthood has been established as a predictor of constructs associated with self-objectification, such as disordered eating [8] and body dissatisfaction [41]. Anxious romantic attachment and fear of intimacy are associated with poor body image and dysfunctional appearance investment in adult women [6].

While there is some research on the connection between insecure adult attachment and body dissatisfaction, there are fewer studies that specifically examine the association between adult attachment styles and self-objectification. Likewise, self-objectification has been linked to problems within romantic relationships (e.g., [44]) but there have been no studies to date on the role of anxious or avoidant attachment in self-objection. For example, Sanchez and Broccoli [32] found that women who were primed with the idea of romantic relationships were more likely to experience state self-objectification. Furthermore, Sanchez and Kwang [34] found that women were more likely to experience body shame when they felt a pressing need to be in a relationship, such that their self-esteem was contingent upon having a partner. While Sanchez and Kwang suggested that future research examine the role of adult attachment styles in the experience of self-objectification there has been no additional research exploring the role of adult attachment styles in self-objectification and body shame.

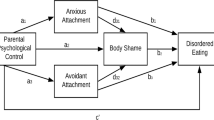

Our goal for the current study was to better understand the role of adult attachment styles in women’s experience of body surveillance and body shame. We developed a hypothesized model (see Fig. 1) to explain the relationships between anxious and avoidant adult attachment styles, body surveillance, and body shame. We hypothesized that anxious and avoidant adult attachment would positively predict body surveillance and that body surveillance would, in turn, predict body shame. We also hypothesized that our attachment variables would indirectly predict body shame through surveillance.

Method

Participants

Our sample consisted of 193 women between the ages of 18 and 30. The average age of participants in our sample was 21.72 (SD = 3.26). Participants identified as heterosexual (76.2 %), homosexual (2.1 %), and bisexual (12.4 %); 9.8 % of participants indicated that they identified with a sexual orientation that was not listed. The majority of our participants identified as White/Caucasian (83.4 %); 5.20 % identified as Hispanic, 2.1 % identified as Asian, and 1.6 % identified as Black/African American. 7.8 % of our participants identified with an ethnicity that was not listed. The majority of our participants had completed some college education (66.8 %). Participants also reported having received a Bachelor’s degree (20.2 %), having completed a Master’s or Doctoral degree (6.2 %), having a high school diploma (3.1 %), completing some high school (3.1 %), having received an Associate’s degree (2.1 %), or having completed trade school (0.5 %).

Procedure

Participants were recruited using a snowball sampling technique through social networking websites including Facebook, Twitter, and Reddit. Recruitment messages described our investigation as a study on feelings about one’s own body and one’s approaches to relationships. The messages also encouraged potential participants to share the link with others who would be interested in the study and to repost the link on other sites. Participants were given the option to follow a link to our survey on SurveyGizmo.com, where they read and agreed to a statement of informed consent. After completion of the anonymous survey, participants were directed to a debriefing page. Participants received no monetary incentive or external reward for their efforts.

Measures

Experiences in Close Relationships Scale

The Experiences in Close Relationships Scale-Short Form [42] is a self-report measure that assesses anxious and avoidant adult attachment styles. Responses on this scale range from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). A sample item from the anxious attachment subscale is “I need a lot of reassurance that I am loved by my partner,” and a sample item from the avoidant attachment subscale is “I am nervous when partners get too close to me.” In the original investigation, Cronbach’s alphas were .78 (anxiety subscale) and .84 (avoidance subscale); in our study, Cronbach’s alphas were .79 (anxiety subscale) and .87 (avoidance subscale).

Objectified Body Consciousness Scale

We used the body surveillance and body shame subscales of the Objectified Body Consciousness Scale [22] to assess constructs associated with self-objectification. A sample item from the body surveillance subscale is “During the day, I think about how I look many times.” A sample item from the body shame subscale is “When I can’t control my weight, I feel like something must be wrong with me.” Responses on these scales ranged from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). In the original investigation, Cronbach’s alphas for the body surveillance and body shame subscales were reported at .89 and .75, respectively. Reliability in our study was .86 and .89, respectively.

Results

Body surveillance and body shame were significantly positively correlated with each other as well as with both attachment variables. Anxious and avoidant attachment were not significantly correlated. For specific correlations coefficients as well as descriptive statistics, see Table 1.

Our hypothesized model, in which attachment styles indirectly predicted body shame via body surveillance, was estimated with path analysis using M-plus version 6.12 with maximum likelihood estimation [27]. The fit of our hypothesized model was adequate according to recommended standards (e.g., [17, 35]), χ2 (2) = 13.17, p = .001, CFI = .92, SRMR = .05, but modification indices suggested that an additional direct path from anxious attachment to body shame would improve fit. Our revised model had good fit to the data, χ2 (1) = 4.18, p = .04, CFI = .98, SRMR = .03, and represented a significant improvement in fit from our hypothesized model, χ 2Δ (1) = 8.99, p < .01. Standardized path coefficients for our revised model are provided in Fig. 2. Avoidant and anxious attachment explained 13.6 % of the variance in surveillance (p = .003), and the attachment variables and surveillance explained 43.8 % of the variance in body shame (p < .001). We also tested the indirect effects of avoidant and anxious attachment on body shame through surveillance. Both avoidant attachment, z = 2.53, p = .01, and anxious attachment, z = 4.57, p < .001, had significant indirect effects on body shame.

Discussion

Our findings build upon prior research that demonstrates the role of interpersonal influences on the experience of self-objectification, poor body image, and body shame. While the bulk of prior research focuses more heavily on the role of early childhood attachment and peer relationships (e.g., [29, 37]), we approached self-objectification and body shame within the context of adult romantic attachment.

In support of our hypotheses, anxious and avoidant adult attachment styles positively predicted body surveillance and body surveillance positively predicted body shame. We also modified our hypothesized model to include a direct positive path from anxious attachment to body shame, and the revised model had good fit to our data. The positive relationships between insecure romantic attachment and body surveillance and body shame indicated by our research mirrors the relationships found in prior research between childhood attachment styles and the pursuit of thinness [19, 39].

The relationship between adult romantic attachment and body surveillance was stronger for anxious attachment styles than it was for avoidant attachment styles, and anxious attachment directly predicted experiences of body shame. The greater relative strength of anxious attachment as a predictor of body surveillance and body shame paralleled the findings of Cash et al. [6]. While Cash et al. did not consider the role of self-objectification or body surveillance, they did find that insecure adult romantic attachment was a positive predictor of body dissatisfaction and that this relationship was stronger for anxious romantic attachment than for avoidant attachment. They attributed these findings to heightened sensitivity to social evaluation and greater overall social anxiety among individuals with anxious romantic attachment, suggesting that people with anxious attachment styles have negative working models of self which lead them to perceive themselves as unworthy or incompetent in relation to others. As such, Cash et al. suggest that people with anxious attachment styles overvalue the importance of physical appearance as central to their social acceptability (or lack thereof).

Previous research also indicates that women who exhibit anxious and avoidant romantic attachment styles in adulthood may experience a heightened fear of rejection [23, 29] and feel that their self-worth is contingent upon their ability to find a romantic partner [34]. Individuals with anxious romantic attachment styles may seek relationships with a greater sense of urgency [36]. Heightened fears of rejection and relationship contingency are linked to self-objectification and body shame [23, 29, 34]. Additionally, women who seek romantic partners with a sense of urgency have been found to be more likely to experience body shame, which may be tied to the perception of physical appearance and attractiveness crucial for finding (or not finding) a romantic partner [33]. Future research is necessary to determine whether rejection fears and relationship contingent self-worth explain the relationship between anxious romantic attachment styles and body shame.

Another possible explanation for our findings draws upon the importance of interpersonal connectedness to overall health and well-being. From this perspective, it may be that women who have more secure attachment styles have stronger interpersonal connections and greater social support, which may buffer against the internalization of objectification and protect against self-objectification. Cash et al. [6] found that women who were secure in their relationships tend to view their bodies more favorably; this may be due to a decreased sensitivity to objectification. Women who are securely attached may have developed a response that allows them to avoid internalizing objectification. In the same light, women with anxious or avoidant attachment styles may have less interpersonal security and, therefore, are less able to overcome their experiences of objectification. While our data suggest that anxious and avoidant romantic attachment are positive predictors of self-objectification and body shame, further research is necessary to corroborate this idea.

While attachment styles are thought to be generally stable, especially throughout childhood (e.g., [10]), there is some literature to suggest that romantic attachment in adulthood is more responsive to change, whether due to important experiences in relationship (e.g., finding a supportive partner, ending an unhealthy relationship) or in response to therapy [36]. If this is the case, then our data may point to the possibility that cultivating a healthier approach to romantic relationships may lessen the likelihood of self-objectification and body shame in women.

It is important to keep in mind the limitations of this study when interpreting the results. One issue is the generalizability of this study. Our sample was rather homogenous in regard to ethnicity, age, sexual orientation, and level of education; our sample consisted largely of white, heterosexual, college-aged women. There is literature to suggest that women of different sexual orientations (e.g., [9]) and ethnic backgrounds (e.g., [3]) experience objectification differently. Our findings may not apply to more diverse populations. Future research would benefit from including more diverse samples in order to explore these sociocultural differences and their relationship to attachment and self-objectification. It may be particularly relevant to consider the relationship between romantic attachment and self-objectification across women of different sexual orientations, as objectifying messages that link relationship success to physical attractiveness are largely aimed at heterosexual couples.

It should also be noted that the data for this study was collected online, so all participants had to have access to the internet and a level of comfort with social media that would allow for them to learn about this study. Additionally, as participants were not compensated for their participation, those who chose to complete this brief survey may well have had greater intrinsic interest in the research topic than those who opted not to.

Lastly, it should be noted that the correlational nature of this study cannot necessarily predict direction of causation. Therefore, while our hypothesized direction is supported by previous research (e.g., [6, 32, 34]), it cannot be ruled out that body surveillance and body shame precipitate the development of anxious and avoidant adult attachment styles.

Despite these cautions, our research supports the idea that adult romantic attachment may influence women’s relationships to their bodies, whereas previous research in this realm has focused largely on the impact of early attachment. Women with more insecure romantic attachment styles may be more likely to experience self-objectification and body shame. Further research is necessary to determine whether romantic attachment styles are fixed or if they evolve over time in response to significant relationships, new partners, or the introduction of individual or couples’ therapy. If romantic attachment styles are subject to change, then addressing underlying insecure attachment styles and seeking healthier approaches to relationships may lessen the impact of self-objectification and decrease body shame.

References

APA, Task Force on the Sexualization of Girls. (2007). Report of the APA task force on the sexualization of girls. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. Retrieved from www.apa.org/pi/women/programs/girls/report.aspx.

Brennan, K. A., Clark, C. L., & Shaver, P. R. (1998). Self-report measures of adult attachment: An integrative overview. In J. A. Simpson & W. S. Rholes (Eds.), Attachment theory and close relationships (pp. 46–76). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Buchanan, T. S., Fischer, A. R., Tokar, D. M., & Yoder, J. D. (2008). Testing a culture-specific extension of objectification theory regarding African American women’s body image. The Counseling Psychologist, 36, 697–718. doi:10.1177/0011000008316322.

Calogero, R. M., Tantleff-Dunn, S., & Thompson, J. K. (2011). Self-objectification in women: Causes, consequences, and counteractions. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Carr, E. R., & Szymanski, D. M. (2011). Sexual objectification and substance abuse in young adult women. The Counseling Psychologist, 39, 39–66. doi:10.1177/0011000010378449.

Cash, T. F., Thériault, J., & Annis, N. M. (2004). Body image in an interpersonal context: Adult attachment, fear of intimacy, and social anxiety. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 23, 89–103. doi:10.1521/jscp.23.1.89.26987.

Chen, F. F., & Russo, N. F. (2010). Measurement invariance and the role of body consciousness in depressive symptoms. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 34, 405–417. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6402.2010.01585.x.

Elgin, J., & Pritchard, M. (2006). Adult attachment and disordered eating in undergraduate men and women. Journal of College Student Psychotherapy, 21, 25–40. doi:10.1300/J035v21n02_05.

Engeln-Maddox, R., Miller, S. A., & Doyle, D. M. (2011). Tests of objectification theory in gay, lesbian, and heterosexual community samples: Mixed evidence for proposed pathways. Sex Roles, 65, 518–532. doi:10.1007/s11199-011-9958-8.

Fraley, C. R., Vicary, A. M., Brumbaugh, C. C., & Roisman, G. I. (2011). Patterns of stability in adult attachment: An empirical test of two models of continuity and change. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 101, 974–992. doi:10.1037/a0024150.

Frederick, D. A., Forbes, G. B., Grigorian, K. E., & Jarcho, J. M. (2007). The UCLA body project I: Gender and ethnic differences in self-objectification and body satisfaction among 2,206 undergraduates. Sex Roles, 57, 317–327. doi:10.1007/s11199-007-9251-z.

Fredrickson, B. L., & Roberts, T.-A. (1997). Objectification theory: Toward understanding women’s lived experiences and mental health risks. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 21, 173–206. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6402.1997.tb00108.x.

Fredrickson, B. L., Roberts, T.-A., Noll, S. M., Quinn, D. M., & Twenge, J. M. (1998). That swimsuit becomes you: Sex differences in self-objectification, restrained eating, and math performance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75, 269–284. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.75.1.269.

Gapinski, K. D., Browness, K. D., & LaFrance, M. (2003). Body objectification and “fat talk”: Effects on emotion, motivation, and cognitive performance. Sex Roles, 48, 377–388. doi:10.1023/A:1023516209973.

Gay, R. K., & Castano, E. (2010). My body or my mind: The impact of state and trait objectification on women’s cognitive resources. European Journal of Social Psychology, 40, 695–703. doi:10.1002/ejsp.731.

Greenleaf, C., & McGreer, R. (2006). Disordered eating attitudes and self-objectification among physically active and sedentary female college students. Journal of Psychology: Interdisciplinary and Applied, 140, 187–198. doi:10.3200/JRLP.140.3.187-198.

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6, 1–55. doi:10.1080/10705519909540118.

Kozee, H. B., & Tylka, T. L. (2006). A test of objectification theory with lesbian women. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 30, 348–357. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6402.2006.00310.x.

Matera, C., Nerini, A., & Stefanile, C. (2013). The role of peer influences on girls’ body dissatisfaction and dieting. European Review of Applied Psychology, 63, 67–74. doi:10.1016/j.erap.2012.08.002.

McKinley, N. M. (1998). Gender differences in undergraduates’ body esteem: The mediating effect of objectified body consciousness and actual/ideal weight discrepancy. Sex Roles, 39, 113–123. doi:10.1023/A:1018834001203.

McKinley, N. M. (1999). Women and objectified body consciousness: Mothers’ and daughters’ body experience in cultural, developmental, and familial context. Developmental Psychology, 35, 760–769. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.35.3.760.

McKinley, N. M., & Hyde, J. S. (1996). The objectified body consciousness scale: Development and validation. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 20, 181–215. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6402.1996.tb00467.x.

Mikulincer, M., & Nachshon, O. (1991). Attachment styles and patterns of self-disclosure. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61, 321–331.

Monro, F., & Huon, G. (2005). Media-portrayed idealized images, body shame, and appearance anxiety. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 38, 85–90. doi:10.1002/eat.20153.

Moradi, B., & Huang, Y. P. (2008). Objectification theory and psychology of women: A decade of advances and future directions. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 32, 377–398. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6402.2008.00452.x.

Morry, M., & Staska, S. (2001). Magazine exposure: Internalization, self-objectification, eating attitudes, and body satisfaction in male and female university students. Canadian Journal of Behavioral Science, 33, 269–279. doi:10.1037/h0087148.

Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (1998–2010). Mplus user’s guide (6th ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén.

Noll, S. M., & Fredrickson, B. L. (1998). A meditational model linking self-objectification, body shame, and disordered eating. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 22, 623–636. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6402.1998.tb00181.x.

Park, L. E. (2007). Appearance-based rejection sensitivity: Implications for mental and physical health, affect, and motivation. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 33, 490–504. doi:10.1177/0146167206296301.

Peat, C. M., & Muehlenkamp, J. J. (2011). Self-objectification, disordered eating, and depression: A test of meditational pathways. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 35, 441–450. doi:10.1177/0361684311400389.

Rieves, L., & Cash, T. F. (1996). Reported social developmental factors associated with womens’ body-image attitudes. Journal of Social Behavior and Personality, 11, 63–78.

Sanchez, D. T., & Broccoli, T. L. (2008). The romance of self-objectification: Does priming romantic relationships induce states of self-objectification among women? Sex Roles, 59, 545–554. doi:10.1007/s11199-008-9451-1.

Sanchez, D. T., Good, J. J., Kwang, T., & Saltzman, E. (2008). When finding a mate feels urgent: Why relationship contingency predicts men’s and women’s body shame. Social Psychology, 39, 90–102. doi:10.1027/1864-9335.39.2.90.

Sanchez, D. T., & Kwang, T. (2007). When the relationship becomes her: Women’s body concerns from a relationship contingency perspective. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 31, 401–414. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6402.2007.00389.x.

Schreiber, J. B., Stage, F. K., King, J., Nora, A., & Barlow, E. A. (2006). Reporting structural equation modeling and confirmatory factor analysis results: A review. The Journal of Educational Research, 99, 323–327. doi:10.3200/JOER.99.6.323-338.

Shaver, P. R., & Clark, C. L. (1994). The psychodynamics of adult romantic attachment. In J. M. Masling & R. F. Bornstein (Eds.), Empirical perspectives on object relations theory (pp. 105–156). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Sharpe, T. M., Killen, J. D., Bryson, S. W., Shisslak, C. M., Estes, L. S., Gray, N., et al. (1996). Attachment style and weight concerns in preadolescent and adolescent girls. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 23, 39–44. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1098-108X(199801)23:1<39::AID-EAT5>3.0.CO;2-2.

Slater, A., & Tiggemann, M. (2002). A test of objectification theory in adolescent girls. Sex Roles, 46, 343–349. doi:10.1023/A:1020232714705.

Tereno, S., Soares, I., Martins, C., Celani, M., & Sampio, D. (2008). Attachment styles, memories of parental rearing and therapeutic bond: A study with eating disordered patients, their parents and therapists. European Eating Disorders Review, 16, 48–58. doi:10.1002/erv.801.

Tiggemann, M., & Kuring, J. K. (2010). The role of body objectification in disordered eating and depressed mood. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 43, 299–311. doi:10.1348/0144665031752925.

Troisi, A., Di Lorenzo, G., Alcini, S., Nanni, R. C., Di Pasquale, C., & Siracusano, A. (2006). Body dissatisfaction in women with eating disorders: Relationship to early separation anxiety and insecure attachment. Psychosomatic Medicine, 68, 449–453. doi:10.1097/01.psy.0000204923.09390.5b.

Wei, M., Russell, D. W., Mallinckrodt, B., & Vogel, D. L. (2007). The experiences in close relationships scale (ECR)-short form: Reliability, validity, and factor structure. Journal of Personality Assessment, 88, 187–204. doi:10.1080/00223890701268041.

Wiseman, M. C., & Moradi, B. (2010). Body image and eating disorder symptoms in sexual minority men: A test and extension of objectification theory. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 57, 154–166. doi:10.1037/a0018937.

Zurbriggen, E. L., Ramsey, L. R., & Jaworski, B. K. (2011). Self- and partner-objectification in romantic relationships: Associations with media consumption and relationship satisfaction. Sex Roles, 64, 449–462. doi:10.1007/s11199-011-9933-4.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

DeVille, D.C., Ellmo, F.I., Horton, W.A. et al. The Role of Romantic Attachment in Women’s Experiences of Body Surveillance and Body Shame. Gend. Issues 32, 111–120 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12147-015-9136-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12147-015-9136-3