Abstract

International academic awards are not only compelling signs of personal academic excellence, but also play a significant role in evaluating the performance of institutions and countries. However, limited literature about awards in social sciences means that many major international academic awards are still unrecognized. Here we collect 180 international academic awards in eight subjects and gauge their relative reputations through online surveys. Moreover, we visualize the awards network based on the relative reputation scores and the number of co-awardees among them by using Gephi software. Finally, we adopt a statistical approach to analyze the structure of the awards network and find that the co-awardee frequencies follow a power-law distribution, which indicates that the awards network is a scale-free network. Our result suggests that a hierarchical status exists among international academic awards in social sciences, which may help us enhance the understanding of the Matthew effect in the academic awards system.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Academia has a long tradition of recognizing scientific achievements through awards and prizes, dating back to 1719 in France, when the Académie des Sciences introduced annual prize competitions to encourage scientists to find solutions to problems in astronomy and navigation, and the Royal Society of London started to award the Copley Medal for outstanding achievements in either the physical or biological sciences in 1731 (Zuckerman 1992). With the establishment of the Nobel Prizes in the early twentieth century, academic distinctions received an international dimension and the Nobel Prizes have come to be the ultimate accolade in science (Merton 1968). Moreover, the scientific community and other stakeholders have established numerous awards to provide individuals with incentives and motivations for new academic work and to reward excellent academic accomplishments in the past decades (Frey and Neckermann 2009).

The topic is of particular importance considering that prestigious awards are not only compelling signs of personal academic excellence, but also play a significant role in evaluating the performances of institutions and countries. Prominent examples are the Academic Ranking of World Universities giving 30% weight to institutions whose alumni and staff win Nobel Prizes and Fields Medals (Liu and Cheng 2005). Saudi Arabia’s Center for World University Rankings uses twenty prestigious international academic awards in its global university rankings (Mahassen 2014). As for the United States National Research Council, it uses an indicator of awards and honors, including 1393 research awards, scholarship awards, teaching awards, fellowships, and membership of professional organizations to rank research doctorate programs (The United States National Research Council Committee on an Assessment of Research Doctorate Programs 2011). There are also scholars evaluating the national-scale research performance by using Nobel Prizes, Fields Medal, Turing Award, Lasker Awards, Yrjö Jahnsson Award, and Hicks-Tinbergen Award (Shelton and Holdridge 2004; Charlton 2007; Mixon and Updahyaya 2011; Rodríguez-Navarro 2016).

In the sociology of science, Merton (1957, 1968) considers “priority of discovery” as the key to an academic reward system that motivates the work, commitment and the efforts of scientists foremost, which further results in the “Matthew Effect” in science. Another scientific capital viewpoint from Bourdieu (1975) sees the awards system to have symbolic power in a competitive struggle among scientists for scientific authority. The concept of scientific capital explains scientific authority as a result of the accumulation of symbolic goods through individual competition among scientists. Furthermore, Frey and Neckermann (2010) provide a view that awards serve as signals which exert a mobilizing effect that boosts the development of science. Other related studies focus on how the reward system works in scientific communities from an anthropological perspective (e.g. Hagstrom 1965; Richter 1972; Latour and Woolgar 1979; Zuckerman 1995).

Despite the prevalence and importance of awards in scientific world, little attention has been devoted to the systematic investigation of academic awards. Forerunners are Cole and Cole’s (1967) measurement of the prestige of 98 awards and honors in physics. Followers are Best’s (2008) introduction of 50 book awards in sociology, and Coupé’s (2013) analysis of 26 best paper prizes given by economics and finance journals. From an international perspective, Zheng and Liu (2015) have weighted the prestige of 207 international academic awards, which included 174 awards in science and technology and 33 awards of three subjects in social sciences. However, the limited range of subjects and number of awards from the previous studies illustrate the fact that many major international academic awards in social sciences remain unrecognized.

The aim of this study, therefore, is to investigate the overall status of international academic awards in social sciences. We collected 180 international academic awards and further gauged the relative reputation of them through two-round online surveys. In addition, we visualized the awards network based on the relative reputation scores and complete data of 957 pairs of co-awardees among these awards by using Gephi software. Finally, we explored the structure of the awards network using statistical analyses to calculate the distribution of co-awardee frequencies.

Methods

Award collection and selection

Considering that there are no existing comprehensive and up-to-date international academic awards lists in social sciences (Frey 2006; Zheng and Liu 2015), we sent the online survey to 3182 academic heads of departmental or school-level academic units from 746 universities around the world for their recommendation of important international academic awards in each subject. All of the 746 universities were chosen from the top 500 world university lists published by the Academic Ranking of World Universities, Quacquarelli Symonds World University Rankings, The Times Higher Education World University Rankings, and the U.S. News & World Report Best Global Universities Rankings in 2015, and all of the academic units were from Business and Management, Communication and Journalism, Economics, Education, Law, Political Science and International Relations, Public Administration, and Sociology. The surveys were conducted between January and March 2017, and 217 responses were returned. A total number of 221 awards have been collected from their recommendations. Table 1 shows the most recommended awards for each subject.

Thereafter, we select 180 international academic awards from the recommendation award lists using Zheng and Liu’s (2015) criteria:

-

awards for highly recognized academic contribution. Scholarship awards, teaching awards, public service awards, honorary fellowships or professional association memberships, travel or conference grants, and student or dissertation awards are not included;

-

awards granted without differentiation of gender, race, ethnicity, color, religion, language, disability, or political affiliation;

-

awards granted by international organizations, central governments, renowned foundations, academic associations, national academies, learned societies, and research sectors.

These 180 awards include ten interdisciplinary awards, which refer to those granted in at least two subjects. The number and proportion of awards in each subject are listed in Table 2.

Reputation survey

In order to gauge the prestige and importance of the selected 180 international academic awards by the same standard so as to enable all awards comparable, we set the Nobel Prizes as the benchmark award which can be commonly seen among the most prestigious achievements of all times (Merton 1968; Zuckerman 1995; Mazloumian et al. 2011; Schlagberger et al. 2016). Reputation surveys were carried out subject by subject. Awards conferred in a particular subject were included and listed in the same survey questionnaire, while awards in interdisciplinary subjects were included and listed in questionnaires of all relevant subjects. For each questionnaire, survey respondents were asked to evaluate quantitatively the relative reputations of awards they were familiar with as compared with the Nobel Prizes. For each award in a questionnaire, a five-point Likert scale was provided for respondents to choose from: “Negligible” = 0, “Low” = 0.25, “Average” = 0.50, “High” = 0.75, and “Highest” = 1. Respectively, the five levels of reputation represent how a respondent considers a given award as “not important”, “somewhat important”, “important”, “very important” and having “the same importance” as Nobel Prizes, which as the benchmark award has a reputation at the “highest” level.

The respondents to the reputation survey consisted of two groups: (1) 2228 academic heads of departmental or school-level academic units of eight subjects from 349 universities worldwide (according to the compilation of top 100 world universities lists published by Academic Ranking of World Universities, Quacquarelli Symonds World University Rankings, The Times Higher Education World University Rankings, and the U.S. News & World Report Best Global Universities Rankings in 2017); (2) 563 highly cited researchers of relevant subjects (according to the compilation of highly cited researchers lists published by Clarivate Analytics for the years 2001, 2014, 2015, 2016, and 2017).

Using SurveyMonkey, the reputation surveys were sent out to respondents via e-mail invitations. The questionnaires were open to the respondents for about 70 days from January to March 2018. After the first invitation email, three reminder emails were sent during the survey period.

Network analysis

Network analysis allowed us to visualize the award status and also to indicate the relationships between different awards. A previous study had explored the close or distant relationships among awards by counting the numbers of co-awardees or awardees in common (Zheng and Liu 2015). Accordingly, we collected the names of awardees from the award’s inception to the awarding year 2017 based on these 180 awards. Each awardee name had a uniform format in the database, and the number of co-awardees for every pair of awards could be counted accurately. We identified a total of 957 pairs of co-awardees among the 152 awards in our database, as there are also 28 awards that have no co-awardees. We then visualized the award network by using Gephi, which is an open data visualization and network analysis software (Bastian et al. 2009).

Network analysis has been much studied in many fields ranging from computer science to the social sciences (Barabási 2009). One of the most important results is that most networks have the so-called “small world” property (Watts 1999). Moreover, Barabási and Albert (1999) proposed a scale-free network property which indicates a network demonstrating few hub nodes with heavy linkage, but with most nodes seldom linking to each other. Meanwhile, the number of links to nodes exhibits a power-law distribution. Network analysis is also widely used in science activity research, such as Otte and Rousseau’s (2002) study of network analysis in the information sciences, Glänzel and Schubert’s (2004) analysis of co-authorship networks, and Ding’s (2011) work on citation network analysis.

Results

Reputation of awards

A total of 2791 survey invitations were sent out, and 536 responses from 48 countries and regions were returned. Figure 1 shows the distribution of respondents by countries and regions. The average response rate was 19.2% (see “Appendix 1” for response rate for each subject).

As Fig. 2 shows, the prestige gap among awards is quite significant. Besides the Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel, only the John Bates Clark Medal reaches the level of “high” reputation score (no less than 0.75), 15 awards with reputation score of no less than 0.50 but below 0.75, 147 awards with reputation score of no less than 0.25 but below 0.50, and 17 awards with reputation score less than 0.25. The average reputation scores of all 180 awards are listed in ‘‘Appendix 2’’.

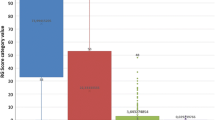

Figure 3 presents the distribution of average reputation scores of awards for each subject. The Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel is the highest reputation award, and the other prestigious award in Economics is the John Bates Clark Medal awarded by the American Economic Association, whose reputation score counts 0.78. The most prestigious award in Communication and Journalism is the Pulitzer Prize in Journalism awarded by Columbia University with a reputation score of 0.71, and in Education, the Distinguished Contributions to Research in Education Award awarded by the American Educational Research Association, with a reputation score of 0.60. In the subjects of Public Administration, Political Science and International relations, Business and Management, Law, and Sociology, the highest reputation awards are as follows: the Herbert A. Simon Book Award awarded by the American Political Science Association; the Johan Skytte Prize in Political Science awarded by The Johan Skytte Foundation; the Distinguished Scholarly Contributions to Management Award awarded by the Academy of Management; the Stockholm Prize in Criminology awarded by Stockholm University; and the International Sociological Association Award for Excellence in Research and Practice, awarded by the International Sociological Association. These have reputation scores of 0.58, 0.52, 0.52, 0.51, and 0.49 respectively. The most prestigious interdisciplinary awards in social sciences are the Holberg Prize, awarded by the Government of Norway, and the Stein Rokkan Prize for Comparative Social Science Research, awarded by the European Consortium for Political Research, with the same reputation scores of 0.50.

Figure 4 shows the distribution of 180 international academic awards in social sciences by awarding institution types. About 40% of awards are awarded by international organizations, followed by national academies and societies, universities and research institutions, and foundations. There are also ten awards awarded by other forms of institutions, such as governments, enterprises, and journals.

Award network

Based on the relative reputation scores of 180 awards and the 957 pairs of co-awardees among them, we display the award network as a radial axis layout grouped by subjects to explore the overall distribution of co-awardees and the relations of different awards among subjects. As Fig. 5 shows, each node represents an award, the size of node representing the relative reputation of an award, and the width of the linkage indicating the number of co-awardees between two awards. Apparently, the number of co-awardees between awards is quite different: there are more co-awardees winning Economic awards as well as Business and Management awards; and similarly, there are more co-awardees winning awards in Political Science and International Relations as well as awards in Public Administration. However, Sociology awards have the least co-awardees compared with the other subjects in this network. Table 3 lists the number of co-awardees in each subject.

In addition, the linear trend in Fig. 6 suggests a positive correlation between the number of co-awardees and the reputation of awards. The Pearson correlation test validates this observation with a correlation coefficient of 0.49 (p < 0.01). Moreover, the average number of co-awardees of the most prestigious awards (65.5) is eight times more than the least prestigious awards (8.1). Meanwhile, of all of the awards in this network, the Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel has the highest number of co-awardees (87) with 33 other awards, followed by the National Communication Association Distinguished Scholar Award, 55 co-awardees with nine other awards, and the John Bates Clark Medal, 44 co-awardees with 17 other awards.

Furthermore, we detect the structure of the awards network by calculating the distribution of co-awardee frequencies. According to Clauset et al. (2009), the general characteristic of a power-law distribution is a heavy-tailed distribution where the scale of most events is very small, and only a few events are in large scale, which has the form

where x is the variable of interest, representing the number of linkages per node; α is the law’s exponent; C is a constant greater than zero; and P(x) is the probability of observing the value x. Graphically, a pure power-law distribution appears as a straight line in the plot with a constant slope on a log–log plot (Goldstein et al. 2004).

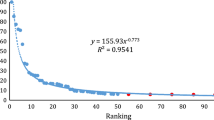

In Fig. 7, the co-awardee frequencies follow a power-law distribution with C = 24.95 and α = 0.99, the coefficient of determination is 0.95, which shows a small number of nodes (awards) with many linkages (co-awardees) and a large number of nodes with less linkages. Hence, the awards network follows the generation rule of scale-free network according to Barabási and Albert’s (1999) definition. Therefore, a node that is caused by statistical fluctuations will receive more linkages than others during the initial stages and will increasingly get more linkages, becoming a hub. Similarly, poorly connected nodes tend to continue with a low level of linkages. In other words, there is a hierarchy or structural inequality among these awards.

This scale-free property provides clues about the preferential attachment underlying the international academic award network. Especially when considering the insights from the sociology of science, as Zuckerman’s (1995) remarks of “the reputations of award winners are also passed to the award”, along with Merton (1968) and Cole’s (1973) view of Matthew effect in the academic awards system, this theory of cumulative advantage may suggest that the prestigious awards are becoming more and more prestigious by being awarded to the best or the most influential scientists.

Discussions and conclusion

The current study aimed to identify the overall status of international academic awards in social sciences by surveying the relative reputations of awards and visualizing the awards network using Gephi software. What’s more, we also explored the structure of the awards network using statistical analysis of the distribution of co-awardee frequencies. Among the limitations of this study, the response rates of our surveys were relatively low, with an average of just below 20%. Nevertheless, we consider that the survey results are reliable and valid not only in the context of large-scale email surveys but also because of the respectable academics such as deans from world-class universities as our survey respondents. Furthermore, those subjects with lower response rates, such as Economics (14.7%) and Business and Management (16.9%), have relatively large numbers of respondents (80 and 89 respectively). Other limitations related to the range of the subjects, important subjects like psychology, human geography, and demography are not included in our survey due to the complexity of the subjects and the workload of data collection.

Our results demonstrate the hierarchical status of international academic awards in social sciences. As for the reputation scores, only 16 awards reach the average reputation level compared to the Nobel Prizes. This number is relatively low when compared with the 82 awards in engineering sciences and natural sciences from a previous survey by Zheng and Liu (2015). Furthermore, when comparing the most prestigious awards of each subject in social sciences with those in engineering sciences and natural sciences, as Fig. 8 illustrates, we find that the disparity of reputation scores among subjects and fields is obvious, as most natural science subjects have relatively higher scores than the others. By contrast, most subjects in social sciences seem to gain lower scores, which demonstrates the systematic inequity of academic recognition across subjects. On the other hand, academic awards and prizes by their very nature are rare, especially prestigious ones. Thus, this hierarchical structure illustrates that Lotka’s law (Lotka 1926), or the law of limited excellence (Price 1963; Yair et al. 2017), is also inherent in the academic awards system.

Source: Zheng and Liu (2015)

Comparison of the most prestigious awards of each subject in social sciences, engineering sciences, and natural sciences.

Additionally, when it comes to the awards network, the power-law distribution of co-awardee frequencies implicates the scale-free property which is familiar with the Matthew effect from the view of the sociology of science. This result is not beyond expectations as compared with the scale-free nature of networks in other kinds of science activities. Various investigations presented in previous scientometric studies have demonstrated that the scale-free or power-law distribution is widely characterized in scientific networks, such as Lotka’s law and Price’s law in citation networks (Lotka 1926; Price 1965; Redner 1998; Ronda-Pupo and Katz 2017), the scale invariant properties in scientific collaborations and co-author networks (Glänzel 2001; Barabási et al. 2002; Cainelli et al. 2015; Ribeiro et al. 2018; Ronda-Pupo and Pham 2018), Bradford’s law in publishing networks (Abramo et al. 2009; Garfield 2009; Kim et al. 2016), and the nonlinear effects in university networks (van Raan 2013). The core finding of the above studies is that there is a natural law of inequality in academia whereby scientific excellence is rare. We do not have a general theory on the origin of the structural inequality of the awards network. This hierarchic structure may have emerged through a long evolutionary process. However, the preferential attachment and the symbolism of intellectual property of the Matthew effect (Merton 1988) provides implications for the development of science: Research is conducted by people, as academic awards are usually awarded to people who have made outstanding scientific achievements. Thus, the laureates of prestigious awards that are hubs in this hierarchical network might somehow guide or influence other scientific community’s attention to the research topics investigated by them.

In closing, our work on international academic awards in social sciences forms a basis for further research on academic awards. More broadly, we note that the hierarchic structure of international academic awards system in social sciences raises several questions: What factors will affect the reputation of academic awards? Do monetary rewards motivate or does history matter? Will the academic awards system be better off, in terms of awarding “the greatest genius” or choosing younger ones whose careers could benefit from the recognition? In addition, how does it impact their academic career or scientific behavior after the academic wins a prestigious award? These are complicated questions about the structure and efficacy of the academic awards system, and further study is required to answer them.

References

Abramo, G., D’Angelo, C. A., & Caprasecca, A. (2009). The contribution of star scientists to overall sex differences in research productivity. Scientometrics, 81(1), 137–156.

Barabási, A. L. (2009). Scale-free networks: A decade and beyond. Science, 325(5939), 412–413.

Barabási, A. L., & Albert, R. (1999). Emergence of scaling in random networks. Science, 286(5439), 509–512.

Barabási, A. L., Jeong, H., Néda, Z., Ravasz, E., Schubert, A., & Vicsek, T. (2002). Evolution of the social network of scientific collaborations. Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications, 311(3–4), 590–614.

Bastian, M., Heymann, S., & Jacomy, M. (2009). Gephi: An open source software for exploring and manipulating networks. Proceedings of the Third International ICWSM Conference, 8, 361–362.

Best, J. (2008). Prize proliferation. Sociological Forum, 23(1), 1–27.

Bourdieu, P. (1975). The specificity of the scientific field and the social conditions of the progress of reason. Information (International Social Science Council), 14(6), 19–47.

Cainelli, G., Maggioni, M. A., Uberti, T. E., & De Felice, A. (2015). The strength of strong ties: How co-authorship affect productivity of academic economists. Scientometrics, 102(1), 673–699.

Charlton, B. G. (2007). Which are the best nations and institutions for revolutionary science 1987–2006? Analysis using a combined metric of Nobel prizes, Fields medals, Lasker awards and Turing awards (NFLT metric). Medical Hypotheses, 68(6), 1191–1194.

Clauset, A., Shalizi, C. R., & Newman, M. E. (2009). Power-law distributions in empirical data. SIAM review, 51(4), 661–703.

Cole, S., & Cole, J. R. (1967). Scientific output and recognition: A study in the operation of the reward system in science. American Sociological Review, 32(3), 377–390.

Cole, J. R., & Cole, S. (1973). Social stratification in science. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Coupé, T. (2013). Peer review versus citations—An analysis of best paper prizes. Research Policy, 42(1), 295–301.

Ding, Y. (2011). Scientific collaboration and endorsement: Network analysis of co-authorship and citation networks. Journal of Informetrics, 5(1), 187–203.

Frey, B. S. (2006). Giving and receiving awards. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 1(4), 377–388.

Frey, B. S., & Neckermann, S. (2009). Awards: A view from economics. In G. Brennan & G. Eusepi (Eds.), The economics of ethics (pp. 73–88). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Frey, B. S., & Neckermann, S. (2010). Awards as signals (No. CESifo Working Paper: 3229). CESifo. Retrieved from http://www.econstor.eu/handle/10419/46399.

Garfield, E. (2009). From the science of science to Scientometrics visualizing the history of science with HistCite software. Journal of Informetrics, 3(3), 173–179.

Glänzel, W. (2001). National characteristics in international scientific co-authorship relations. Scientometrics, 51(1), 69–115.

Glänzel, W., & Schubert, A. (2004). Analysing scientific networks through co-authorship. In H. F. Moed, W. Glänzel, & U. Schmoch (Eds.), Handbook of quantitative science and technology research (pp. 257–276). Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers/Springer.

Goldstein, M. L., Morris, S. A., & Yen, G. G. (2004). Problems with fitting to the power-law distribution. The European Physical Journal B-Condensed Matter and Complex Systems, 41(2), 255–258.

Hagstrom, W. O. (1965). The Scientific Community. New York: Basic Books

Kim, J., Tao, L., Lee, S. H., & Diesner, J. (2016). Evolution and structure of scientific co-publishing network in Korea between 1948–2011. Scientometrics, 107(1), 27–41.

Latour, B., & Woolgar, S. (1979). Laboratory life: The social construction of scientific facts. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

Liu, N. C., & Cheng, Y. (2005). Academic ranking of world universities—Methodologies and problems. Higher Education in Europe, 30(2), 127–136.

Lotka, A. J. (1926). The frequency distribution of scientific productivity. Journal of the Washington Academy of Sciences, 16(12), 317–323.

Mahassen, N. (2014). A quantitative approach to world university rankings. Retrieved from http://cwur.org/methodology/preprint.pdf.

Mazloumian, A., Eom, Y. H., Helbing, D., Lozano, S., & Fortunato, S. (2011). How citation boosts promote scientific paradigm shifts and Nobel prizes. PLoS ONE, 6(5), e18975.

Merton, R. K. (1957). Priorities in scientific discovery: A chapter in the sociology of science. American Sociological Review, 22(6), 635–659.

Merton, R. K. (1968). The Matthew effect in science. Science, 159(3810), 56–63.

Merton, R. K. (1988). The Matthew effect in science, II: Cumulative advantage and the symbolism of intellectual property. ISIS: Journal of the History of Science in Society, 79(4), 606–623.

Mixon, F. G., Jr., & Updahyaya, K. P. (2011). From London to the continent: Ranking European economics departments on the basis of prestigious medals and awards. Economia, 14(2), 119–126.

Otte, E., & Rousseau, R. (2002). Social network analysis: A powerful strategy, also for the information sciences. Journal of Information Science, 28(6), 441–453.

Price, D. (1963). Little science, big science. New York: Columbia University Press.

Price, D. (1965). Networks of science paper. Science, 149(3683), 510–515.

Redner, S. (1998). How popular is your paper? An empirical study of the citation distribution. The European Physical Journal B-Condensed Matter and Complex Systems, 4(2), 131–134.

Ribeiro, L. C., Rapini, M. S., Silva, L. A., & Albuquerque, E. M. (2018). Growth patterns of the network of international collaboration in science. Scientometrics, 114(1), 159–179.

Richter, M. (1972). Science as a cultural process. Cambridge, MA: Schenkman Publishing Co.

Rodríguez-Navarro, A. (2016). Research assessment based on infrequent achievements: A comparison of the United States and Europe in terms of highly cited papers and Nobel Prizes. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 67(3), 731–740.

Ronda-Pupo, G. A., & Katz, J. S. (2017). The scaling relationship between degree centrality of countries and their citation-based performance on Management Information Systems. Scientometrics, 112(3), 1285–1299.

Ronda-Pupo, G. A., & Pham, T. (2018). The evolutions of the rich get richer and the fit get richer phenomena in scholarly networks: The case of the strategic management journal. Scientometrics, 116(1), 363–383.

Schlagberger, E. M., Bornmann, L., & Bauer, J. (2016). At what institutions did Nobel laureates do their prize-winning work? An analysis of biographical information on Nobel laureates from 1994 to 2014. Scientometrics, 109(2), 723–767.

Shelton, R. D., & Holdridge, G. M. (2004). The US-EU race for leadership of science and technology: Qualitative and quantitative indicators. Scientometrics, 60(3), 353–363.

The United States National Research Council Committee on an Assessment of Research Doctorate Programs. (2011). In Ostriker, J. P., Kuh, C. V. & Voytuk, J. A. (Eds.) A data-based assessment of research-doctorate programs in the United States. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US). Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK83404/.

van Raan, A. F. J. (2013). Universities scale like cities. Plos ONE, 8(3), e59384.

Watts, D. J. (1999). Networks, dynamics, and the small-world phenomenon. American Journal of Sociology, 105(2), 493–527.

Yair, G., Gueta, N., & Davidovitch, N. (2017). The law of limited excellence: Publication productivity of Israel Prize laureates in the life and exact sciences. Scientometrics, 113(1), 299–311.

Zheng, J., & Liu, N. (2015). Mapping of important international academic awards. Scientometrics, 104(3), 763–791.

Zuckerman, H. (1992). The proliferation of prizes: Nobel complements and Nobel surrogates in the reward system of science. Theoretical Medicine, 13(2), 217–231.

Zuckerman, H. (1995). Scientific elite: Nobel Laureates in the United States. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1

See Table 4.

Appendix 2: Listing of the 180 international academic awards in social sciences and their average reputation scores

See Table 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, and 13.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Jiang, F., Liu, N. The hierarchical status of international academic awards in social sciences. Scientometrics 117, 2091–2115 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-018-2928-y

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-018-2928-y