Abstract

International academic awards are popular as incentives and rewards for academics all over the world, and have played a significant role in the performance evaluations of individuals and institutions. However, little is known about the relative importance of awards and the relationships between awards. This study aims to establish a comprehensive global map of important international academic awards, which visually presents the relative reputations of awards and the close or distant relationships between awards. By surveying the reputations of the preselected 207 awards, 90 important international academic awards with above-average reputations were identified. Then, based on the number of “awardees in common” or named “co-awardees” between every pair of these 90 awards, a network of co-awardees was built. Finally, using mapping software of VOSviewer, these 90 important international academic awards were mapped by taking the reputation scores as the weights of awards and the network of co-awardees as the basis of the relationships between awards.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

As pointed out by Robert K. Merton, with the development and professionalization of science, the institution of science has developed an elaborate reward-system for allocating rewards to individuals who live up to its norms, or whose behavior go beyond the scope of normal performance (Merton 1957). One of the most common and attractive forms of reward is the receiving of the badges, medals, ribbons, rings, plaques, trophies, sashes, statuettes, pins, patches, or other material embodiments of the award, which are the symbols of honor and excellence that recognize the recipients’ work and contributions (Best 2008). This type of reward, being referred to as an “award” in this study, is sometimes conferred together with a certain amount of prize money, and usually has the word—“award”, “medal” or “prize”—in its name. As the International Who’s Who (IWW) shows, individuals in the academic sector are among the major recipients of these awards (Frey and Neckermann 2009). These academics are not immune to awards as a form of social flattery (Frey and Neckermann 2009).

As a well-known feature in all societies throughout all times, all awards can be generally regarded as direct or indirect incentives (Frey and Neckermann 2008b), and as signals of performance to the public and people concerned that the award winners are engaged in extraordinary, desirable, and venerable behavior (Frey and Neckermann 2010). As for academic awards, some certain features make the award more suited, popular and attractive incentive instruments than monetary compensation. These features can be summed up as follows (Frey 2006; Frey and Neckermann 2008a):

-

By signaling high social status, the value of awards to the recipients may be very high, but with low material costs or none.

-

By evaluating subjectively the overall performance ex post, awards are better suited than performance pay to reward scientific tasks, which are typically of a vague nature.

-

By signaling research talent and motivation, which are valuable characteristics in the academia and are hard to assess for outsiders, awards are attractive stimulus in the academic setting.

-

By conveying appreciation and recognition, awards raise the intrinsic motivation to do research and generate loyalty to the awarding institution.

The names of awards can be usually and easily found in the CVs and official personal introductions of the recipients, and even in the introductions of the recipients’ affiliations and other institutions concerned. Because of the publicity and the visible symbol associated with awards (Frey and Neckermann 2010), awards signal their recipients’ past performance. As for academic awards, they are established to provide rewards for past academic accomplishments. Especially for outsiders, academic awards can be seen as indicators to observe and evaluate the academic performance of award winners or the winners’ institutions concerned. For example, the Nobel Prizes and Fields Medal have been used as ranking indicators since 2003 in the first global university ranking, the Academic Ranking of World Universities (ARWU), both of whose weight accounts for 30 % in total, to assess the quality of education and the quality of faculty of hundreds of universities (Liu and Cheng 2005). About twenty prestigious international academic awardsFootnote 1 have been used to constitute the indicator of “Quality of Faculty” in the global university rankings since 2012, which is published by Saudi Arabia’s Center for World University Rankings (CWUR) (Mahassen 2014). The US National Research Council (NRC) used 1393 awards and honors, including research awards, scholarship awards and teaching awards, for the external assessment of the perceived quality of doctoral program faculties in the 2008 Assessment of Research-Doctorate Programs (The US National Research Council Committee on an Assessment of Research Doctorate Programs 2011). Furthermore, some prominent international academic awards, such as the Nobel Prizes, Fields Medal, Lasker Awards, Turing Award and Canada Gairdner International Award, were taken to build symbolic measures of research performance and trends in “revolutionary” science, with the aim of identifying the premier revolutionary science research institutions and nations in some studies (Charlton 2007a, 2007b, 2007c).

Although academic awards, especially prestigious international academic awards, have played important roles in seeking excellence by assessing and ranking academic institutions, we know little about their relative reputations and the relationships between them, which are limitations to the use of academic awards as a performance indicator. Taking the ARWU for example, only two indicators based only on the most recognized international awards—the Nobel Prizes and Fields Medal (Liu and Cheng 2005)—which has led to the criticism of the ranking methodologies for ignoring other highly prestigious international awards and not covering distinctions of every important scientific field (Billaut et al. 2010; Waltman et al. 2012). In another case, the US NRC’s Assessment of Doctorate Programs made use of 1393 awards and honors, which were identified by the NRC committee as “Highly Prestigious” or “Prestigious” with the former given a weight five times that of the latter, to measure the perceived quality of faculty. It is far more than the awards involved in the ARWU indicators, but the awards and honors were selected and given their weighting arbitrarily by the NRC. In order to facilitate the use of academic awards, especially international academic awards, as indicators in various types of academic evaluation, it is important and necessary to weigh their relative reputations in relation to one another and explore the relationships between them.

Unfortunately, the study on the reputations of academic awards and the relationships between them is insufficient. In Zuckerman’s opinion, because of the scarcity and the constraining rules of the Nobel Prizes, some important international academic awards, such as the Templeton Prize, Crafoord Prizes, Charles Stark Draper Prize, Fields Medal, Balzan Foundation Prize, Vetlesen Prize and Tyler Ecology Award,Footnote 2 were instituted and can be classified as “Nobel Complements” and “Nobel Surrogates” by their relationship with the Nobel Prizes (Zuckerman 1992). In another study, 98 awards and honors, which included prizes, medals, membership of academic societies and research fellowships, were weighed by surveying physicists (Cole and Cole 1973). Previous studies have only focused on a small number of academic awards or on the better-known awards, without distinguishing between the types of award.

As international academic awards have more influence on academics around world, and have a more important role in the evaluation and ranking of academic institutions than national awards, this study focuses on international academic awards. In this study, we collected 207 international academic awards from a broad range of fields and subjects from diverse sources, gauged their relative reputations compared with the Nobel Prizes by surveys, which were conducted subject/field by subject/field, and then selected awards with above-average reputations as important awards. Based on the number of co-awardees for pairs of important international academic awards and the total number of recipients of each award, a network of co-awardees was built which contains the percentage of co-awardees for every pair of awards. With the help of the mapping software VOSviewer, these important international academic awards were mapped by taking reputation as the weight of an award and network of co-awardees as the basis for building relationships between awards.

Methodology

Preliminary selection of international academic awards

In this study, “international academic awards” are defined as those awards established to recognize the outstanding academic achievements of internationally renowned scholars and scientists, and conferred to individuals generally regardless of nationality, race, gender, age, religion, ethnicity, sexual orientation, presence of disabilities, language, and political affiliation.

Taking into consideration that there is no comprehensive and up-to-date list of international academic awards, we could only collect partial and sketchy awards data from scattered sources (Frey 2006). Our initial list of such awards was compiled from the following three sources:

-

the list of awards and honors from the US National Research Council;

-

the “list of prizes, medals and awards” from Wikipedia and searching of relevant pages on Wikipedia;

-

the available information from various national and international organizations, learned societies, academy of sciences, etc.

Based on the following three criteria, 207 international academic awards (see “Appendix 1”) were preselected for the reputation survey:

-

awards for this study mainly refer to awards which are all or partly granted to individuals who have made a widely-recognized contribution to the advancement of knowledge. In other words, awards in this study can generally be regarded as research awards. Scholarship awards, teaching awards, public service awards, fellowships or memberships in honorary academic institutions, travel or conference grants, and graduate student or post-doctoral awards are not included;

-

awards for this study are granted without restrictions on nationality, and generally regardless of race, gender, age, religion, ethnicity, sexual orientation, disability, language, or political affiliation;

-

awards for this study are generally granted by international organizations, national governments, renowned foundations, academic associations, national academies and learned societies.

These preselected 207 international academic awards have a broad coverage of fields, including Life Sciences and Medicine, Natural Sciences, Engineering Sciences, Social Sciences, and Multidisciplinary Fields. The awards in Multidisciplinary Fields refer to those awards granted in at least two of the other four fields. As shown in Table 1, the awards granted in Natural Sciences, Engineering Sciences, and Social Sciences are further classified by subject. The awards in Cross-disciplinary fields refer to those awards granted in at least two of the subjects in a particular field.

Though there are some subjects not included in this study, especially within the humanities and social sciences, most of the well-known international academic awards in a broad range of fields and subjects have been included in this study. These 207 awards were used to build a map of international academic awards as the first step towards a more comprehensive mapping of academic awards.

Based on these 207 awards, the names of their awardees from the award’s inception to the awarding year 2013 were collected. Each awardee’s name had a uniform format in the database, and the number of co-awardees for every pair of awards could be counted accurately.

Reputation survey

In order to gauge the relative prestige and importance of the preselected 207 international academic awards and to further select the more important ones, reputation surveys were designed and conducted subject/field by subject/field.

The “benchmark award”

First of all, a “benchmark award” with the highest reputation needed to be set to gauge the relative reputations of awards.

The first name that comes to mind for most people would be the Nobel Prizes, which were established at the turn of the 20th century. Granted in more than one field (physics, chemistry, physiology or medicine, and later economics), they are conferred to scientific elites without any restriction regarding the nationality of candidates. Since changing the scale of monetary awards for scientific achievement dramatically, the Nobel Prizes have become seen as the “ultimate accolade” in science and occupy a unique place in both the public mind and the reward system of science (Merton 1968), and they have become “a prevailing worldwide metaphor for supreme achievement—of all sorts” (Zuckerman 1992). Furthermore, some award givers proudly claim that their award winners have also won Nobel prizes. For example, the Lasker Foundation claims on its website that the Lasker Awards often presage future recognition by the Nobel committee, and so they have become popularly known as “America’s Nobels”.

Given all this, the Nobel prizes can serve as a gold standard to gauge the prestige of all other awards (Zuckerman 1992), and they were therefore chosen as the “benchmark award” for this study.

The questionnaires

Reputation surveys were carried out subject/field by subject/field. Awards conferred in a particular subject were included and listed in the same survey questionnaire, while awards in multidisciplinary fields and cross-disciplinary subjects were included and listed in questionnaires of all the fields or subjects of interest. 16 survey questionnaires were designed and completed in the 15 subjects and in the Life Sciences and Medicine, as shown in “Appendix 2”.

For each questionnaire, survey respondents were asked to evaluate quantitatively the relative reputations of their familiar awards as compared with the Nobel Prizes. For each award included in a questionnaire, a five-point Likert scale was provided for respondents to choose from: “Negligible” = 0, “Low” = 0.25, “Average” = 0.50, “High” = 0.75, and “Highest” = 1. Respectively, the five levels of reputation represent how the respondent feels that a given award holds as “not important”, “somewhat important”, “important”, “very important” and having “the same importance” as the Nobel Prizes, which is the “benchmark award” with the reputation at the “highest” level of 1.

The respondents

As awards are one of the most important producers of status or social recognition (Frey 2006), and increase a recipient’s income directly and indirectly when they come with a monetary prize or facilitate access to external funding (Frey and Neckermann 2008a), the higher the reputation of an award, the higher the honor and the more distinction its recipients will gain. The recipients of relevant awards were chosen to be respondents of the surveys since they are the ones who are most familiar with the status of relevant awards and most qualified to judge the reputations of relevant awards.

Respondents to the questionnaire in a specific subject/field were the awardees who had won awards included in this questionnaire. In the trial survey, we first chose awardees from 1980 to 2013 inclusive as respondents for the survey in mathematics. Considering the age of awardees, awardees from 1990 to 2013 inclusive were finally chosen as respondents for the surveys in other subjects and for the field of Life Sciences and Medicine. As for the recipients who had won awards granted in multidisciplinary and cross-disciplinary fields, they were included in groups of respondents by relevant awarding subjects.

The surveys

The questionnaires in the 15 subjects and the field of Life Sciences and Medicine were sent out to their corresponding respondents by SurveyMonkey, which is the world’s most popular online survey software. The questionnaires were open to the respondents for about 45 days. During this period, after the first invitation email, two reminder emails were sent respectively in the middle and later stage of survey.

Selection of important international academic awards

In order to facilitate the use of international academic awards as an effective measurement of excellence in academic evaluations, important international academic awards were selected from the survey results that all had an average reputation score no <0.50, meaning that these selected awards had an average or above average reputation as compared with the Nobel Prizes.

We must here emphasize that the aim of this paper is not to identify the differences between the awards with the average reputation scores at or above 0.50 and the awards with scores less than 0.50, especially those with scores close to 0.50. We set only one selection criterion of 0.50 for its “average” symbol, selection convenience and fairness to all the surveyed subjects and fields.

Finally, 90 important awards with average reputation scores of no less than 0.50, marked in bold in “Appendix 1”, were finally selected to analyze the co-awardees of the awards and to compile an award map.

Analyzing co-awardees

In this study, co-awardees were used as the basis to explore the relationships between awards. The reason is that the recipients of an award fully embody the features of this award and its status in the reward system. Once the final winners of an award are announced, these winners acquire a certain good reputation from this award by standing at the same level with its past winners. By the same token, the reputations of award winners are also passed to the award (Zuckerman 1995). So there exist close and deep connections between an award and its recipients.

Similar to the way in which using references as the basis to study the similarities between documents in scientometric, when we treat awards as documents and award recipients as references cited by the documents, it is assumed that co-awardees can be used to explore the similarities between awards. As Kessler (1963) suggests, documents that have one or more references in common are bibliographically coupled, and documents with the same references are regarded as very similar in nature. In the same way, one pair of awards that share co-awardees can also be seen as coupled, related and similar to some degree.

By counting the total number of co-awardees for every pair of awards extracted from the selected 90 important international academic awards, a network or a matrix of co-awardees was constructed. Considering the size effect, that is, an award with more recipients may share more co-awardees with other awards, the matrix of percentage of co-awardees was constructed to study the close or distant relationships between these 90 awards. For award i, the percentage of recipients of award i who have won each of the other awards, and the percentage of recipients of each of the other awards who have won award i, are included in the matrix.

Mapping awards

Mapping has been used extensively in scientometric research for decades (Börner et al. 2003). A map of science is a spatially visualized representation of how fields, subjects, publications and authors are related to one another by displaying their physical proximity and relative locations (Small 1999). In general, there are three steps for mapping. Taking the mapping of documents as an example, the first step is to select items such as references, the citations that a paper receives, or important words shown in the title or abstract, as the basis for comparing documents. Then, based on these items, the similarities between the documents are computed by measures such as Jaccard index, inclusion index, cosine index, and association strength. Finally, the similarities are visualized by means of multivariate analyses (Sternitzke and Bergmann 2009). A number of software tools have been developed to conduct science mapping analysis (Cobo et al. 2011).

To map the selected 90 important awards in this study, we took co-awardees for these awards as the basis for comparing awards and the VOSviewer software developed by Leiden University as a mapping tool. The similarity measure adopted by VOSviewer is association strength, which is better for normalizing co-occurrence frequencies by making fair comparisons between objects with a high frequency of occurrence and objects with a low frequency of occurrence (Van Eck et al. 2007a). The association strength, which is sometimes known as the proximity index (Peters and van Raan 1993) or the probabilistic affinity index (Zitt et al. 2000), can be defined as the following equation and be seen as a measure of the deviation of observed co-occurrence frequencies from the expected co-occurrence frequencies under an independence assumption (Van Eck and Waltman 2009):

As for the association strength between awards in this study, S A in the function denotes the degree of similarity between award i and award j, \(c_{ij}\) denotes the percentage of co-awardees for award i and award j, w i (w j ) denotes the total percentage of co-awardees for award i (award j) and all the other awards. For practical purposes, it was convenient to multiply this measure by the total percentage of co-awardees involved, which was denoted by N (Peters and van Raan 1993; Van Eck et al. 2007b, 2009).

Finally, the similarities between awards were visualized by means of the VOS mapping technique, which aims to minimize a weighted sum of the squared Euclidean distances between all pairs of objects (the awards in this study) when having a constraint that the average distance between two objects must be equal to 1 (Van Eck and Waltman 2010). The process of computing and the visualization of similarities between awards were automatically completed by VOSviewer.

The weight of an award in the map is determined by its average reputation score, and the closer or more distant relationships between awards were determined by the similarities between awards. The average reputation score of each award was calculated based on the reputation survey results and the similarities between awards, which were measured by the association strength adopted by VOSviewer, were calculated based on the network of co-awardees for the 90 important awards.

Results

Reputation survey

The surveys on the reputation of the preselected 207 international academic awards were conducted between March 2013 and April 2014. A total of 2567 survey invitations were sent out, and 391 responses were returned. The average response rate is 17.1 % (see “Appendix 2” for response rate for each subject/field).

The response rates for our surveys were relatively low partly because of the advanced age of the awardees. Among all of the surveyed awardees, at least 40.1 % of them were born before 1943, which means that at least 40.1 % of awardees are over the age of 70. Even so, considering the respondents’ expertise and authority as winners of international awards, the survey results are reliable or could be references for further study and discussion. Among the 391 responses, 47 % of the responses were from award recipients of the United States, 10 % from the United Kingdom, 7 % from the Germany, and the rest from another 35 countries and regions. Among all responses, 81 % of the responses were from higher education institutions, 9 % from independent research institutions, and the rest from other types of institutions, such as commercial companies and governmental agencies.

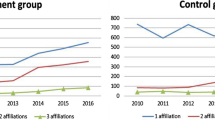

The average reputation scores of all 207 awards are listed in “Appendix 1”. As shown in Fig. 1, these awards hold reputational standings at different levels. Besides the four Nobel Prizes (for Physics, Chemistry, Physiology or Medicine, and Economic Sciences) having the highest reputation scores of 1, there are 11 international academic awards with an average reputation score of no <0.75, which means that these 11 awards are very important compared with the Nobel Prizes. There are 75 important awards with scores of no less than 0.50 but below 0.75, 112 less important awards with scores of no less than 0.25 but below 0.50, and five unimportant awards with scores of less than 0.25. Obviously, there is a hierarchy of reputation among these 207 awards.

The distribution of average reputation scores of awards for each subject and field is shown in Fig. 2. The percentage of important international academic awards in the fields of Natural Sciences and Engineering Sciences appear to be higher and there are also more important awards in Life Sciences and Medicine.

Based on the survey results and the reputation selection criterion of 0.50, 90 important international academic awards with average reputation scores of no <0.50 were finally chosen for the co-awardee analysis and mapping study. As shown in Fig. 3, there are 36 important international academic awards granted in Natural Sciences, 33 important awards in Engineering Sciences, nine important awards in Life Sciences and Medicine, eight important awards in Social Sciences and four important awards in Multidisciplinary Fields.

Co-awardees’ analysis

Based on the number of co-awardees for every pair of awards and the total number of recipients of each award selected from 90 of the most important international academic awards, a 90 × 90 adjacency matrix of percentage of co-awardees was obtained. Excluding the pairs of awards on the diagonal of this matrix, which are composed of the same award, there are 8010 pairs of awards in the matrix.

As shown in Table 2, among these 90 important awards, 87 awards share awardees in common with another award or other awards, and three awards share no co-awardees with other awards at all. There is one award that shares co-awardees with other 39 awards, which is the King Faisal International Prize in Science, given by the King Faisal Foundation for outstanding works of a broad scope, alternating between physics, chemistry, biology and mathematics. Further, there are three awards that share co-awardees with more than 25 other awards, 11 awards that share co-awardees with more than 20 other awards, and 63 awards that share co-awardees with more than five other awards.

As shown in Table 3, among the 8010 pairs of different awards in the matrix of percentage of co-awardees, 7056 pairs of awards do not share any co-awardees, and a small number of pairs of awards share a high percentage of co-awardees. For example, 81.8 % of recipients of the Crafoord Prize in Mathematics are recipients of the Fields Medal, 77.8 % of recipients of the Crafoord Prize in Astronomy are also recipients of the Bruce Medal and the Royal Astronomical Society’s Gold Medal for Astronomy, 72.9 % of recipients of the Wolf Prize in Medicine are recipients of the Canada Gairdner International Award.

Mapping awards

By using VOSviewer mapping software, a map of the selected 90 important international academic awards was constructed and shown in Fig. 4. It is clear that some awards connected to just a few other awards are isolated in the map, such as the European Criminology Award and Stockholm Prize in Criminology. Figure 5 shows the largest set of connected awards, which consists of 79 awards.

In the label view of the award map, an award is indicated by a label and a circle. For an award in the map, the font size of its label and the area of its circle depend on its weight, which in this research equals its average reputation score. The more important an item in the map, the larger its label and its circle (Van Eck and Waltman 2010). So some more important awards which have larger labels and circles can be directly identified from the map by zooming in on a specific area, such as the Nobel Prizes, Wolf Prizes, Crafoord Prizes, Shaw Prizes, Abel Prize, Fields Medal, Tyler Prize, A. M. Turing Award, and the IEEE Medal of Honor. These awards are all well-known internationally.

In the label view of award map, the link between every pair of awards indicates that these two awards share co-awardees with each other. The color of an award indicates the cluster to which this award is assigned by the VOS clustering technique, which can be seen as a kind of weighted variant of modularity-based clustering (Waltman et al. 2010). Unlike modularity-based clustering, however, the VOS clustering technique has a resolution parameter, which is an important parameter that determines the level of detail provided by VOS clustering technique. After trying out different values for this parameter, we decided to set the resolution parameter equal to 1.50, to yield a clustering with a satisfactory level of detail as shown in Fig. 5. The clustering shown in Fig. 5 consists of 10 clusters, which also remains consistent with clustering by subject and field. The reason is that awards are located in the map by VOSviewer in such a way that the distance between any pair of awards reflects their similarity as accurately as possible. The higher similarity between two items in the map, the closer they are located (Van Eck et al. 2007b). So awards in a particular subject/field or related subjects/fields which share more co-awardees with each other are located closer together in the map and assigned to one cluster.

The similarity measure adopted by VOSviewer is association strength. So the similarity between one pair of awards not only depends on the percentage of co-awardees between themselves, but also on the percentage of co-awardees for each of these two awards and other awards. Taking the Nobel Prizes as an example, among the 90 awards included in the map, there are 14 awards sharing co-awardees with the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, 23 awards with the Nobel Prize in Chemistry, 22 awards with the Nobel Prize in Physics, and three awards with the Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences. The top three awards which have the highest association strength or similarity with the Nobel Prizes are listed in Table 4. These awards share more co-awardees with the Nobel Prizes while sharing less co-awardees with other awards. In more extreme cases, among the 62 awards connected to the Nobel Prizes, the Erwin Plein Nemmers Prize in Economics and the Johan Skytte Prize in Political Science share co-awardees only with the Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences, which leads to the highest association strength with the Nobel prizes. Therefore, mapping of important awards can visually show us how close or distant the relationships are between awards.

In order to go into more detail, the maps of important international academic awards in the fields of Life Sciences and Medicine, Natural Sciences, and Engineering Sciences were established and are shown in Fig. 6. These maps are based on the network of co-awardees for every pair of awards in each field.

As shown in Fig. 6, besides that some important awards can be identified directly from the maps, awards in Natural Sciences and Engineering Sciences are assigned to clusters by subject. The clustering of awards is not found in the field of Life Sciences and Medicine due to its highly interdisciplinary nature.

Concluding remarks

This study aimed to select the important international academic awards by surveying the reputations of the preselected 207 international academic awards and exploring the relationships between these awards by mapping the selected 90 important international academic awards.

By weighing the reputations of the preselected 207 sample awards compared to the Nobel Prizes, which are taken as a whole to be the benchmark award with the highest reputation score of 1, 90 important international academic awards with average reputation scores no <0.50 were finally selected.

By analyzing the distribution of co-awardees for every pair of these 90 important international academic awards, those which share co-awardees with more awards and share more co-awardees with other awards were identified, including the King Faisal International Prize, Crafoord Prizes, and Wolf Prize in Medicine.

By introducing mapping technology which is commonly used in bibliometrics, this study managed to map the selected 90 important international academic awards and visually present their relative importance and the relationships between them, taking the reputation of each award as its weight and the distribution of co-awardees for every pair of awards as the basis for building their relationships,

Although this study succeeded in presenting the relative importance of international academic awards and the relationships between them quantitatively, there are some limitations and further research is required. First of all, due to the limitations of data sources, only 33 awards in the Social Sciences were included in our preliminary award list, which is much less than the awards for Natural Sciences and Engineering Sciences. More awards need to be added to the list of international academic awards, especially for the humanities and social sciences. Furthermore, our surveys on the reputation of awards were not carried out at the same time because of the workload from data collection, a very large share of respondents were from the United States, and the response rates of our surveys were relatively low partly because of the age of the awardees. In order to get a more accurate measure of the reputational standings of awards, more qualified respondents, especially un-American respondents, need to be involved in surveys simultaneously in future studies. Finally, because of the technical limitations of mapping software, only one similarity measure of association strength adopted by VOSviewer was used to measure the close or distant relationships between awards by building award mapping. For comparison, other similarity measures could be used to explore the relationships between awards in future studies.

This study is our preliminary approach to international academic award, which aims to weigh the relative reputations of awards and explore the close or distant relationships between awards. Although there are limitations mentioned above, this study could be the basis for further research on other topics of international academic award, such as the correlation between the reputation of awards and the bibliometric performance of awardees, Nobel predictions based on co-awardees of relevant awards, and the economics of awards.

Notes

This indicator measures the weighted number of faculty members of an institution who have won, in addition to the Nobel Prize and the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences, the following awards, medals, and prizes covering virtually all academic disciplines: Abel Prize, Balzan Prize, Charles Stark Draper Prize, Crafoord Prize, Dan David Prize, Fields Medal, Fundamental Physics Prize, Holberg International Memorial Prize, Japan Prize, Kavli Prize, Kluge Prize, Kyoto Prize, Millennium Technology Prize, Praemium Imperiale, Pritzker Prize, Shaw Prize, Schock Prize, Templeton Prize, Turing Award, Wolf Prize, and World Food Prize.

By 1983, the name of Tyler Ecology Award was changed permanently to the Tyler Prize for Environmental Achievement.

References

Best, J. (2008). Prize proliferation. Sociological Forum, 23(1), 1–27. doi:10.1111/j.1573-7861.2007.00056.x.

Billaut, J.-C., Bouyssou, D., & Vincke, P. (2010). Should you believe in the Shanghai ranking? Scientometrics, 84(1), 237–263. doi:10.1007/s11192-009-0115-x.

Börner, K., Chen, C. & Boyack, K. W. (2003). Visualizing knowledge domains. In B. Cronin (Ed.), Annual Review of Information Science and Technology (Vol. 37, pp. 179–255). NJ: Information Today, Inc./American Society for Information Science and Technology. Retrieved from http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/aris.1440370106/full.

Charlton, B. G. (2007a). Measuring revolutionary biomedical science 1992–2006 using Nobel prizes, Lasker (clinical medicine) awards and gairdner awards (NLG metric). Medical Hypotheses, 69(1), 1–5. doi:10.1016/j.mehy.2007.01.001.

Charlton, B. G. (2007b). Scientometric identification of elite “revolutionary science” research institutions by analysis of trends in Nobel prizes 1947–2006. Medical Hypotheses, 68(5), 931–934. doi:10.1016/j.mehy.2006.12.006.

Charlton, B. G. (2007c). Which are the best nations and institutions for revolutionary science 1987–2006? Analysis using a combined metric of Nobel prizes, fields medals, Lasker awards and turing awards (NFLT metric). Medical Hypotheses, 68(6), 1191–1194. doi:10.1016/j.mehy.2006.12.007.

Cobo, M. J., López-Herrera, A. G., Herrera-Viedma, E., & Herrera, F. (2011). Science mapping software tools: review, analysis, and cooperative study among tools. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 62(7), 1382–1402. doi:10.1002/asi.21525.

Cole, J., & Cole, S. (1973). Social stratification in science. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Frey, B. S. (2006). Giving and receiving awards. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 1(4), 377–388. doi:10.1111/j.1745-6916.2006.00022.x.

Frey, B. S. & Neckermann, S. (2008a). Academics appreciate awards-a new aspect of incentives in research. Retrieved from http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1319323.

Frey, B. S., & Neckermann, S. (2008b). Awards: A view from psychological economics. Zeitschrift Für Psychologie/Journal of Psychology, 216(4), 198–208. doi:10.1027/0044-3409.216.4.198.

Frey, B. S., & Neckermann, S. (2009). Awards: A disregarded source of motivation. In M. Baurmann & B. Lahno (Eds.), Perspectives in moral science (pp. 177–182). Frankfurt am Main: Frankfurt School Verlag. Retrieved from http://www.rmm-journal.de/downloads/012_frey_neckermann.pdf.

Frey, B. S., & Neckermann, S. (2010). Awards as signals (No. CESifo working paper: 3229). CESifo. Retrieved from http://www.econstor.eu/handle/10419/46399.

Kessler, M. M. (1963). Bibliographic coupling between scientific papers. American Documentation, 14(1), 10–25.

Liu, N. C., & Cheng, Y. (2005). Academic ranking of world universities—Methodologies and problems. Higher Education in Europe, 30(2), 127–136.

Mahassen, N. (2014). A Quantitative approach to world university rankings. Retrieved from http://cwur.org/methodology/preprint.pdf.

Merton, R. K. (1957). Priorities in scientific discovery: A chapter in the sociology of science. American Sociological Review, 22(6), 635–659. doi:10.2307/2089193.

Merton, R. K. (1968). The Matthew effect in science. Science, 159(3810), 56–63.

Peters, H. P. F., & van Raan, A. F. (1993). Co-word-based science maps of chemical engineering. Part I: Representations by direct multidimensional scaling. Research Policy, 22(1), 23–45.

Small, H. (1999). Visualizing science by citation mapping. Journal of the American Society for Information Science, 50(9), 799–813.

Sternitzke, C., & Bergmann, I. (2009). Similarity measures for document mapping: a comparative study on the level of an individual scientist. Scientometrics, 78(1), 113–130. doi:10.1007/s11192-007-1961-z.

The US National Research Council Committee on an Assessment of Research Doctorate Programs. (2011). In Ostriker, J. P., Kuh, C. V. & Voytuk J. A. (Eds.) A data-based assessment of research-doctorate programs in the United States. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US). Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK83404/.

Van Eck, N. J., & Waltman, L. (2007a). Bibliometric mapping of the computational intelligence field. International Journal of Uncertainty, Fuzziness and Knowledge-Based Systems, 15(05), 625–645.

Van Eck, N. J. & Waltman, L. (2007b). VOS: A new method for visualizing similarities between objects (No. ERS-2006-020-LIS). Erasmus Research Institute of Management (ERIM). Retrieved from http://springerlink.bibliotecabuap.elogim.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-540-70981-7_34.

Van Eck, N. J., & Waltman, L. (2009). How to normalize cooccurrence data? An analysis of some well-known similarity measures. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 60(8), 1635–1651. doi:10.1002/asi.21075.

Van Eck, N. J., & Waltman, L. (2010). Software survey: VOSviewer, a computer program for bibliometric mapping. Scientometrics, 84(2), 523–538. doi:10.1007/s11192-009-0146-3.

Waltman, L., Calero-Medina, C., Kosten, J., Noyons, E. C. M., Tijssen, R. J. W., van Eck, N. J., & Wouters, P. (2012). The leiden ranking 2011/2012: Data collection, indicators, and interpretation. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 63(12), 2419–2432. doi:10.1002/asi.22708.

Waltman, L., Van Eck, N. J., & Noyons, E. C. M. (2010). A unified approach to mapping and clustering of bibliometric networks. Journal of Informetrics, 4(4), 629–635.

Zitt, M., Bassecoulard, E., & Okubo, Y. (2000). Shadows of the past in international cooperation: collaboration profiles of the top five producers of science. Scientometrics, 47(3), 627–657. doi:10.1023/A:1005632319799.

Zuckerman, H. (1992). The proliferation of prizes: Nobel complements and nobel surrogates in the reward system of science. Theoretical Medicine, 13(2), 217–231.

Zuckerman, H. (1995). Scientific elite: Nobel Laureates in the United States. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Professor Jan Sadlak, the President of the IREG Observatory on Academic Ranking and Excellence, and Professor Paul Wouters, the Director of Centre for Science and Technology Studies (CWTS) at Leiden University, for their useful comments and suggestions on this study. We also wish to thank CWTS’s researcher, Dr. Ludo Waltman and Dr. Rodrigo Costas, for their kind help in solving some of the mapping technology problems.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1: Listing of the 207 international academic awards

Appendix 2

See Table 10.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zheng, J., Liu, N. Mapping of important international academic awards. Scientometrics 104, 763–791 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-015-1613-7

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-015-1613-7