Abstract

Empirical research on the consequences of the use of the balanced scorecard (BSC) has mostly been conducted in large firms. Previous findings are not easily applied to the small business literature, and assumptions about the benefits of BSC for small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) are not based on quantitative empirical evidence. We investigated the effects of SME’s use of BSC in terms of financial performance and innovation outcomes. Our arguments are based on the efficiency gains and potential flexibility losses associated with formalizing managerial practices in SMEs. We propose that the developmental stage of the firm may influence this trade-off. Based on a survey of 201 SMEs in Spain, we found that firms using BSC for feedforward control obtained better financial performance and presented higher levels of exploitative innovation. We also found that the positive effect of BSC on perceived and attained financial performance is stronger in more established SMEs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The balanced scorecard (BSC) is one of the managerial practices most frequently used by large and small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs)Footnote 1 (Rigby and Bilodeau 2015; Cooper et al. 2017). During the last decade, considerable progress has been made on improving the implementation of the BSC within SMEs (Fernandes et al. 2006; Garengo and Bititci 2007; Hudson-Smith and Smith 2007; Wouters and Wilderom 2008; Taylor and Taylor 2014). Proponents of the BSC have suggested that SMEs might benefit extensively from using it (Kaplan and Norton 1996); nevertheless, empirical evidence of the effects of BSC use on SMEs is scarce and has generally been obtained through only a few case studies (e.g. Gumbus and Lussier 2006; Biazzo and Garengo 2012). Most research on the effectiveness of BSC was conducted in large firms and led to the recognition that this managerial practice can help firms successfully achieve their desired outcomes (Ittner et al. 2003; De Geuser et al. 2009; Micheli and Manzoni 2010; Busco and Quattrone 2015). Although important to our understanding of the consequences of using BSC, this finding cannot be generalized to the small business literature (Bititci et al. 2012). Studies have shown that the use of managerial practices in SMEs involves specific attributes not shared with large firms (Hudson-Smith and Smith 2007). First, resource constraints, particularly on management time and expertise, mean that the routine of managerial practices is markedly more demanding for SMEs than for larger firms (Ates et al. 2013). Second, SMEs’ lack of a monetary safety net and their high reliance on fewer customers require their managers to be over-attentive to the evolution of short-term performance measures (Hudson-Smith and Smith 2007). Finally, the flatter and more flexible structure of SMEs typically requires employees to perform multiple roles, with unclear boundaries and job responsibilities. Compensation systems and employee performance appraisals are less formalized and objective in SMEs (Cardon and Stevens 2004).

Particularly challenging for SMEs is the tension between efficiency versus flexibility emerging from the formalization of managerial practices (Chowdhury 2011; Patel 2011). If SMEs benefit from efficiency gains accompanying the use of the BSC, it may come at a cost that is usually associated with significant constraints on firm flexibility (Benner and Tushman 2003). Therefore, a study of the effects of the use of the BSC in SMEs requires more than a simple appreciation of firm efficiency; it requires the thoughtful consideration of its effects on flexibility. This commonly experienced trade-off (Ebben and Johnson 2005; Eisenhardt et al. 2010) concerns SMEs to a great extent because those firms are highly dependent on flexible structures in their efforts to develop exploratory initiatives (Freel 2000; Glaser et al. 2015).Footnote 2

This study uses a combination of archival and survey data gathered from 201 senior managers to investigate the effects of the use of the BSC in SMEs. Drawing on the trade-off between the efficiency gains and the flexibility losses introduced by this formal managerial practice, we argue that the use of the BSC for feedforward control positively influences financial performance and exploitative innovation at the expense of a reduction in exploratory innovation. Second, we take into account the importance of the developmental stage of the firm when describing the use of managerial practices (Davila et al. 2009) and their influence in SMEs (Brinckmann et al. 2010; Rosenbusch et al. 2011). We propose that the firm’s development stage may influence the efficiency-flexibility trade-off resulting from the use of the BSC.

This article contributes to the small business and organizational control literature by extending prior research on the consequences of BSC use in SMEs. It aims to bring more empirical evidence to the scarce organizational control literature that has explored the effects of formal modes of control on SMEs (Wijbenga et al. 2007; Voss and Brettel 2014). Additionally, it adds to the innovation and small business literature by responding to calls for a better understanding of the relationship between technological innovations (i.e. process and product innovation) and managerial practices in SMEs (Hervas-Oliver et al. 2016). It investigates the factors that influence innovation in SMEs (Chang and Hughes 2012) by postulating the use of BSC as a key driver that is employed to control organizational tensions, thus facilitating communication and assisting coordination. We show how the use of BSC might affect the different innovation outcomes of SMEs (i.e. exploitative innovations vs. exploratory innovations), and consequently, this study illustrates how SMEs may benefit from the use of BSC in their attempts to be competitive. Finally, this paper scrutinizes the influences of the theoretically meaningful, yet under-researched, moderating effect of a firm’s developmental stage on the relationship between BSC and performance outcomes. It studies the contributions of BSC to both young and established SMEs. Hence, this research investigates, in greater depth, the nature of the relationship between control and innovation and financial performance, filling an important gap and shedding new light on this complex relationship.

2 Literature review and hypotheses

2.1 Balanced scorecard

BSC represents a multi-perspective framework that relies on a set of metrics (i.e. financial and non-financial, long and short term and internal and external). The original BSC framework was characterized by the presence of four perspectives—financial, customer, internal process and learning and growth—which contained different sets of metrics that were adapted to industries and firms (Kaplan and Norton 1996). As a (strategic) performance measurement system (PMS) (Garengo et al. 2005; Bisbe and Malagueño 2012), this tool allows firms to translate strategy into achievable objectives. A critical assumption of BSC is that each performance measure is part of a balanced cause-and-effect relationship in which leading measures (e.g. non-financial, drivers of future financial performance) drive lagging measures (e.g. financial, results of past actions). By tracking a firm’s progress against these measures, managers and employees can accomplish the firm’s mission by identifying and correcting under-performing perspectives.Footnote 3

A number of frameworks have been proposed in the literature to assess the appropriateness of PMS and consequently their effectiveness. Several of these frameworks emphasize applying design features to evaluate a firm’s existing PMS (Evans 2004). For instance, Medori and Steeple (2000) suggest that PMS should be evaluated based on six stages: the selection of organizational critical success factors, the matching of strategic requirements and priorities, the selection of measures, the audit, the implementation and the maintenance. Other studies, however, show the importance of accounting for the use rather than merely the design when assessing PMS (Koufteros et al. 2014; Bititci et al. 2015). Those studies note that firm performance is a consequence of how practices are conducted rather than the practice itself. In this vein, prior research showed that the adoption of BSC does not imply that it is manifested in more than a ritual manner or that it is practised by organizational participants (Garengo and Sharma 2014). Therefore, in order to understand the effects of BSC on SMEs, it is fundamental to study its use rather than its mere presence or availability.

2.2 Balanced scorecard for feedforward control

In our research, we examine the use of BSC for feedforward control, as opposed to its traditional use for feedback control (Grafton et al. 2010; Pavlov and Bourne 2011). The feedforward use of BSC involves the application of BSC’s formal calculative framework to the constant examination of variances between actual and pre-set targets, aiming to facilitate organizational debates and to promote knowledge sharing and continuous learning. Researchers have noted that feedforward control is preventive, anticipating threats and leading operational changes (Pavlov and Bourne 2011). In contrast, the use of BSC for feedback control involves the application of BSC’s formal calculative framework to the sporadic examination of variances between actual and pre-set targets, aiming at the evaluation of past performance. Feedback enhances monitoring of operations and promotes immediate corrective actions (Ebben and Johnson 2005; Pavlov and Bourne 2011).Footnote 4

A major assumption underpinning the use of BSC among large firms and SMEs is that it has a positive effect on firm performance (Gumbus and Lussier 2006; De Geuser et al. 2009; Cooper et al. 2017). To date, research on the contributions of BSC to large organizations has suggested a positive association between the feedforward use of BSC and the development of new capabilities and exploratory initiatives (Grafton et al. 2010, Pavlov and Bourne 2011). In this paper, we postulate differently, as we discuss the characteristics of SMEs that create a unique context for the use of BSC.

2.3 Balanced scorecard: efficiency gains and flexibility losses

Drawing on configuration theory, we argue that the feedforward use of BSC supports firm efficiency. In SMEs, owner-managers are at the centre of most strategic decisions. They define the firm’s priorities and the pace at which those strategies are implemented. It is expected that a greater emphasis of owner-managers on the BSC framework directs employees’ limited attention towards the key priorities that require action. The continuous use of BSC creates a platform for the broad evaluation of different dimensions of the firm (Garengo et al. 2005). It improves organizational control by enhancing goal clarity among employees and creating an accountability structure in which individuals are assigned to be owners of metrics (Wouters and Wilderom 2008; Busco and Quattrone 2015). Managerial attention to the BSC introduces formalization into SMEs’ traditionally informal operational control structures (Cardinal et al. 2004), facilitating the strategic alignment of employees so that they can efficiently pursue the firm’s intended strategies (Garengo and Bititci 2007). Additionally, the use of BSC for feedforward control triggers regular meetings and discussions between managers and subordinates to evaluate the calculative information contained in the BSC (Pavlov and Bourne 2011). Such gatherings aim to predict likely outcomes arising from the current course of action, and they become opportunities to interpret and integrate knowledge so that efficiency gains made by individual employees are institutionalized and turned into organizational assets (Jones and Macpherson 2006; Grafton et al. 2010). Enhanced efficiency associated with the use of managerial practices has long been recognized as leading to better financial performance (Evans and Davis 2005).

Efficiency is also a prerequisite for the successful development of exploitative innovation. Exploitative innovation entails incremental refinements, continuous improvement and implementation (Volery et al. 2015). It requires managers to deploy a profound understanding of the business, its different perspectives, employees’ know-how and organizational resources (Branzei and Vertinsky 2006; Volery et al. 2015). The structure and comprehensiveness of the information contained in the BSC frame the managers’ distinct cognitive representations of the organization’s strategy, thus influencing the way managers access information, include issues in their strategic agendas and subsequently make decisions. BSC supports cognitive reasoning by focusing managerial attention and framing managers’ heuristics and reasoning (Bisbe and Malagueño 2012; Cheng and Humphreys 2012). Vermeulen (2005) finds that two of the main barriers to the development of exploitative innovations in SMEs are the lack of legitimacy of such activities and the continuous reallocation of resources. The managerial discussions introduced by the use of BSC over metrics and results legitimize initiatives on particular aspects of the business that require improvements (Ates et al. 2013; Busco and Quattrone 2015). For instance, the permanent evaluation of performance against targets related to the customer perspective of the BSC may assist managers of SMEs in keeping track of competitors and understanding what they are offering, as well as why current customers do or do not buy and how satisfied they are. Additionally, BSC sorts targets into different perspectives, reducing the continuous reallocation of resources and providing a framework for measures to be aligned with critical strategies (Gumbus and Lussier 2006; Wouters and Wilderom 2008). Therefore, the use of BSC is likely to encourage the development of exploitative innovations around certain issues that are accounted for in the business strategy. Following the above arguments, we propose the following hypotheses:

-

H1a: The use of the balanced scorecard by SMEs is positively associated with financial performance.

-

H1b: The use of the balanced scorecard by SMEs is positively associated with exploitative innovations.

Flexibility is a prerequisite for the successful development of exploratory innovation. Exploratory innovation entails moving beyond current paradigms and existing product portfolios by experimenting and taking risks (Volery et al. 2015).

Several researchers studying large firms have suggested that the use of BSC for feedforward purposes assists firms in converting tacit into explicit knowledge, thus helping them externalize and combine such knowledge to support the development of exploratory innovations, which respond to and drive environmental trends (e.g. Tuomela 2005; McCarthy and Gordon 2011). This use of BSC is recognized for its ability to promote knowledge sharing and continuous learning, which revolve around strategic uncertainties and opportunities (Grafton et al. 2010). In large firms, it changes the formal performance measurement routine, introducing flexibility where bureaucracy usually prevails. The discussions resulting from the feedforward use of BSC allow top managers to get involved in operational activities, enabling the identification of key success factors that support the more comprehensive (re)formulation of strategies and plans (Bisbe and Malagueño 2012); these discussions also engage organizational members (including lower level employees) in the scanning of market opportunities (Grafton et al. 2010).

However, in SMEs, the flatter structure, faster communication and greater informality of routines and procedures (Srećković 2017) make it more difficult to identify those attributes of the use of BSC that stimulate the development of exploratory innovations in large firms. Owner-managers, usually key drivers of exploratory initiatives in SMEs (Glaser et al. 2015; Volery et al. 2015), are already deeply involved in the organizational processes and consequently might not benefit as much as managers of large firms from the learning experience that might arise from the evaluation of formal BSC. Additionally, exploratory initiatives in SMEs are mostly carried out by a rather informal learning-by-doing process; there is less focus on R&D or even a rather non-R&D-oriented process (Hervas-Oliver et al. 2016). Its flexible structures permit spontaneous discussions and experimentation. Shorter lines of interaction within the firm make the dissemination of tacit knowledge easier in small firms than it is in larger firms (Koskinen and Vanharanta 2002). The use of BSC as a formal managerial practise could easily be confounded by firm participants as another layer of control in SMEs, weakening the flexible communication and control structures that are already in place. Finally, limited resources—in terms of time management and human resources—do not allow managers and subordinates to use formal performance evaluation meetings to deeply scan the external environment to explore new opportunities beyond existing products, markets and customers. In this vein, field study and interviews conducted by Ates et al. (2013) concluded that performance management processes in SMEs are particularly narrow and dedicate the most attention to short-term financial and operational activities, failing to identify and scan external factors that might affect their business. In brief, we predict that the attributes of the use of BSC that stimulate exploratory innovation in large firms are not similarly beneficial to SMEs. Thus,

-

H1c: The use of the balanced scorecard by SMEs is negatively associated with exploratory innovation.

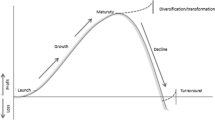

2.4 Developmental stage and the effects of the balanced scorecard

We argued that not all SMEs benefit equally from the use of BSC. A common assertion is that formalization in young firms reduces role ambiguity, decreases the costs of coordination and improves decision-making (Cosh et al. 2012). However, several researchers have noted that the lack of structure in young firms diminishes the efficiency outcomes of formal managerial practices (Chowdhury 2011). Younger SMEs that are resourceful enough to adopt and use BSC often face operational and strategic problems that are not easily predictable. These firms often need to establish managerial and manufacturing processes while lacking internal and external information (Brinckmann et al. 2010). As a result, young SMEs do not have well-defined routines, structures and processes that discipline firm actions and support full implementation of more sophisticated managerial practices (López and Hiebl 2015). That is to say, “it is difficult or impossible to establish performance measures for activities with which the organization has no or very little experience” (Nørreklit 2000, p.72). Consequently, the improved organizational efficiency that is expected to arise from the use of BSC would not be fully achieved in those enterprises.

In contrast, more established SMEs possess the established routines that support the use of sophisticated managerial practices. These firms have already passed their cycle of experimentation and have established processes and products. The feedforward use of BSC provides a framework that enhances learning within the capabilities of the firm, allowing it to be more efficient. It promotes efficiency by diffusing coded learning from past experience across the firm (Davila et al. 2009). Consistent with this argument, Brinckmann et al. (2010) conclude that the higher levels of uncertainty and ambiguous information faced by young SMEs causes the use of planning practices to render lower contributions to those firms than it does for more established small firms. In summary, we expect that firms that have reached later developmental stages will be better equipped to appropriate potential gains in efficiency from the use of BSC. Thus,

-

H2a: The positive effect of the balanced scorecard on financial performance depends on the firm’s stage of development, such that the effect is stronger in more established firms.

-

H2b: The positive effect of the balanced scorecard on exploitative innovation depends on the firm’s stage of development, such that the effect is stronger in more established firms.

The creation of a new firm intrinsically implies novelty (Davila et al. 2012). In younger firms, organizational culture centres on core values and attitudes, such as the inclination to take risks, experimentation, proactivity towards marketplace opportunities and tolerance of failure (Anderson and Eshima 2013). Managers of younger firms are often said to rely more on heuristics and less on rational and formal decision-making tools that would require time and would postpone decisions (Busenitz and Barney 1997). Organizational culture, organic structures and the use of heuristics in decision-making better position younger firms to generate exploratory innovations and take advantage of (benefit from) fleeting “windows of opportunity” (Hill and Rothaermel 2003).

In more established SMEs, core competencies often evolve into core rigidities (Leonard-Barton 1992), which discourage experimentation and risk-taking (Danneels 2002). Over time, firms tend to endorse innovative initiatives that build upon their existing capabilities, so that exploration spontaneously decreases (Branzei and Vertinsky 2006). It is expected that formal managerial practices, such as the BSC, which could be seen as obstacles to creative flexibility in young firms are, in more established firms, considered part of established routines, as the extensive reliance on heuristics in strategic decision-making that is of great advantage for younger firms is insufficient for these firms. Thus,

-

H2c: The negative effect of the balanced scorecard on exploratory innovation depends on the firm’s stage of development, such that the effect is weaker in more established firms.

3 Data and methodology

3.1 Sample, survey, and respondents

To test our hypotheses, we draw on an original survey and archival data gathered from the Bureau Van Dijk database (Iberian Balance Sheet Analysis System—SABI). The sample was selected from the food and beverage industry (NACE codes 10 and 11) in Spain. We employed a procedure of stratified sampling by size and industry from the SABI database. We selected firms with a minimum of ten employees to exclude those small firms that lack the minimal business structure required to implement formal sophisticated managerial practices (McCarthy and Gordon 2011). A total of 5814 firms were identified. Of these, only 2979 provided a contact e-mail.

The survey was conducted between February and May 2011. Following Dillman’s (2000) guidelines for surveys, e-mails were initially sent to all firms to verify the accuracy of the data. Second, the chief executive officer (CEO) of the firm was asked for his or her willingness to participate in this research. Third, a cover letter presenting the study was sent to the firms, in addition to the link to the questionnaire. Fourth, in an attempt to increase the response rate, we sent three follow-up e-mails, and finally, there was a series of phone calls to ask those who had not yet done so to complete the questionnaire. The resulting useable sample for statistical testing included 201 SMEs.Footnote 5

Our research design required us also to capture objective secondary data on firm performance and other control variables for the years 2011 (t + 1), 2012 (t + 2) and 2013 (t + 3). We collected this information from the firms’ financial statements published by SABI. We completed the data collection in the last quarter of 2014.

Descriptive statistics of the sample are presented in Table 1. Details on the survey questions are included in Appendix 1.

A two-step analysis was conducted to test for non-response bias. Respondents were first compared with non-respondents in terms of sample characteristics (size, location, sub-industry). Next, early and late respondents were compared to detect any differences in the mean score of each variable. Using chi-square statistics, no significant differences (p > 0.10) were found, supporting the absence of significant non-response bias.

We checked for the presence of common-rater bias by conducting Harman’s single-factor test on the questions used to form the constructs. Harman’s test assumes that, if a single or common factor that captures the majority of the covariance among the variables emerges from the factor analysis, there is strong evidence of common-rater bias (Podsakoff et al. 2003). The factor solution yielded nine factors with eigenvalues greater than 1.0. The first factor explained 21.01% of the total variance. We also used archival data for dependent and control variables, supporting the absence of significant single-source bias.

We assessed content and construct validity to establish the validity of the survey items (Nunnally 1978). Content validity was evaluated through (i) a review of questions for face validity, (ii) the process of variable construction and (iii) the computation of an empirical measure of internal consistency. Meanwhile, construct validity was analysed through (i) identifying an appropriate domain of items underlying the construct and employing validated measures where possible; (ii) factor analyses to support the unidimensionality of the constructs and (iii) the absence of significant cross-loadings in support of discriminant validity.

We have performed the following tasks to conduct this analysis. First, as far as possible, all constructs were measured using established and reliable scales. Second, a pretest was performed based on the preliminary edition of the questionnaire; the participants in the pretest consisted of 12 academics connected to the management field, three managers of firms in the sector and two managers from outside the sector. All of the participants made proposals and validated the final version of the questionnaire before its release. In general, in the review process, the experts recommended shortening and abbreviating the questionnaire as much as possible. Third, to help establish both content and construct validity, empirical tests suggested by Nunnally (1978) were performed. Table 2 shows the factor analyses employed to construct the variables. Unidimensionality was tested by the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin statistics (KMO > 0.5) and Bartlett’s test on item correlation (Bartlett’s test = 0.00). Reliability was checked using Cronbach’s alpha (α > 0.7).

3.2 Measures

3.2.1 Dependent variables

We use change in sales per employee and perceived performance as measures of financial performance. Changes in sales per employee (Bromiley and Harris 2014) were based on data taken from annual financial statements gathered primarily from the SABI database. We observe a time period of 3 years. Year ‘t’ refers to the year 2010. We calculate t + 1, t + 2 and t + 3 changes in sales per employee after t (e.g. S t+2 − S t; where S t is sales per employee in 2010 and S t+2 is sales per employee in 2012).Footnote 6 Perceived performance is a self-reported variable, measured using an adapted version of the instruments developed by Kaynak and Kara (2004). Factor analysis results indicated that items loaded on one factor with an eigenvalue greater than 1.0. The factor score was introduced into the analysis as a dependent variable.

The measure for exploitative innovation is adapted from Jansen et al. (2006) and comprises four items. It is viewed as an outcome of the innovation process. We measure it by analysing the changes in product design and/or packaging and the changes or improvements in existing products. We used the scoring coefficients of the factor analysis to generate the factor score as a proxy for exploitative innovation.

The measure for exploratory innovation is also adapted from Jansen et al. (2006), and it comprises five items. It is viewed as an outcome of the innovation process. We measured it by analysing the new products’ importance and novelty and the capacity of innovations to change the market structure, create new markets and make the existing product obsolete. We used the scoring coefficients of the factor analysis to generate the factor score as a proxy for exploratory innovation.

3.2.2 Independent variable

The variable use of balanced scorecard indicates the extent to which the firm employs BSC as a feedforward rather than as a feedback control tool. First, respondents were asked about the adoption of BSC.Footnote 7 If BSC was not adopted, respondents were guided to the next section of the questionnaire and all items related to the use of BSC were scored zero. Out of the 201 respondents, 70 (35% of the sample) confirmed that they had adopted BSC. The variable use of balanced scorecard was assessed using a multi-scale instrument based on the extant literature (Bisbe and Malagueño 2009; Grafton et al. 2010). A summated scale was created by adding the scores of four items assessing learning, creativity, discussion and managerial attention. Factor analysis converged on one factor with an eigenvalue greater than 1.0.

3.2.3 Moderating variable

Developmental stage of the firm was measured using years since foundation (i.e. age) (Brinckmann et al. 2010).

3.2.4 Control variables

The following control variables were included in the analysis due to their expected association with the use of BSC and firm innovation, development stage and performance: (i) implementation of the balanced scorecard Footnote 8, (ii) family firm, (iii) strategy, (iv) exports, (v) customer concentration, (vi) hostility, (vii) R&D on sales, (viii) ISO 14000 certification, (ix) sales, (x) R&D collaboration, (xi) assets, (xii) audited firm, (xiii) information and communications technology (ICT), (xiv) intangibles to total assets, (xv) cash to short liabilities, (xvi) R&D employees, (xvii) short-term liabilities and (xviii) employees. All control variables are defined in Appendix 2.

Table 3 displays descriptive statistics on all of the variables for the full sample, BSC adopters sample and BSC non-adopters sample. Table 4 presents the correlation matrix.

3.3 Analytical models

The hypothesized links are analysed using OLS regressions. First, we propose the following models to assess the predicted associations in H1a (model 1), H1b (model 2) and H1c (model 3)Footnote 9:

Second, the hypothesized links in H2a, H2b and H2c require the inclusion of interaction terms (development stage). The following three models are used:

4 Results

4.1 Hypotheses testing

Table 5 displays the effects of the use of BSC on financial performance (model 1), exploitative innovation (model 2) and exploratory innovation (model 3). The equations detailed in these tables include the variables of interest and a set of control variables.

The results show that the use of BSC is positively associated with the change in sales per employeet+2 (β = 0.297, S.E. = 0.163, p < 0.05) and the change in sales per employeet+3 (β = 0.287, S.E. = 0.139, p < 0.05). These results provide support for H1a and indicate that firms using BSC for feedforward control present higher financial performance after t + 2 and t + 3 years than firms not using BSC or firms using BSC for feedback control.

Table 5 also displays the effect of the use of BSC on exploitative and exploratory innovations. The effect of the use of BSC on exploitative innovation is positive and significant (β = 0.206, S.E. = 0.125, p < 0.05), supporting H1b, while the association between the use of BSC and exploratory innovation is negative but not significant (β = − 0.018, S.E. = 0.123, p > 0.05). Thus, H1c is not supported. Combined, these results suggest that the use of BSC for feedforward control helps organizations to be more efficient in their ability to develop exploitative innovations without reducing exploratory innovations.

H2a, tested in model 4 (Table 6), posits a positive effect of the interaction between the use of BSC and the development stage on financial performance.Footnote 10 The interaction is positive and statistically significant on change in sales per employee (t + 1: β = 0.329, S.E. = 0.091, p < 0.01; t + 2: β = 0.367, S.E. = 0.094, p < 0.01; and t + 3: β = 0.289, S.E. = 0.079, p < 0.01), providing support for H2a. Consequently, the effect of the use of BSC in SMEs on financial performance is influenced by the development stage, such that higher financial performance is observed in more established firms using the BSC for feedforward control.

H2b is tested in model 5 and predicts a positive effect for the interaction between the use of BSC and development stage on exploitative innovation. The effect is positive but non-significant (β = 0.038, S.E. = 0.077, p > 0.05). Finally, H2c predicts a positive effect of the interaction between the use of BSC and development stage on exploratory innovation. The results presented in model 6 are not significant (β = − 0.033, S.E. = 0.075, p > 0.05). Thus, H2b and H2c are not supported. Contrary to our expectations, these results suggest that the development stage does not explain variations in the relationship between the use of BSC and innovations (exploitative and exploratory).

Overall, Tables 5 and 6 support the arguments that SMEs benefit positively from using the BSC and that the development stage moderates the relationship between the use of BSC and financial performance.

4.2 Additional analyses and robustness checks

To test the stability of our results, we reran our models without control variables. Methodologists have pointed out that there are issues of validity surrounding the use of control variables, especially when using a large number of control variables (Schjoedt and Bird 2014). Panels A and B in Table 7 depict the results of models 1 to 6 without control variables. The results obtained for all but one relationship are consistent with our primary analysis.Footnote 11

As an additional robustness check, we also ran untabulated analyses using changes in net income as a dependent variable of financial performance. The results remained unchanged.

5 Discussion

We began this research paper by noting the lack of quantitative empirical research on the consequences of the BSC on SMEs and the unsuitability of applying results from large firms to the small business literature. Drawing on the trade-off that arises from the efficiency gains recognized in prior case-based research and the potential losses resulting from the inflexibilities introduced by this formal managerial practice, we investigated the effects of the use of BSC by SMEs in terms of financial performance and innovation outcomes. More specifically, we examined the extent to which the use of BSC for feedforward control influences financial performance and exploitative and exploratory innovations. We argued that these effects are dependent on the developmental stage of the firms.

Based on a survey of 201 SMEs in the food and beverage sector in Spain, we found that SMEs using BSC for feedforward control obtained better financial performance. This higher performance is neither perceived by managers nor attained immediately, but the use of BSC for feedforward control has a positive lagged effect on the sales of SMEs over 2 and 3 years. This result contributes to the small business and organizational control literature by offering more empirical evidence on the effects of formal modes of control on SMEs (Wijbenga et al. 2007; Voss and Brettel 2014). On the one hand, these results provide empirical evidence of the positive implications of the use of BSC, thus supporting claims about the benefits of BSC (Kaplan and Norton 1996). On the other hand, these findings signal major challenges for SMEs that aim to adopt and use BSC. First, they reveal that tangible gains in financial performance cannot be expected immediately. This is in accordance with studies in the small business literature indicating that the extent of the use of sophisticated management practices, such as activity-based costing, is positively associated with firm financial performance in terms of growth over 2 years (Jänkälä and Silvola 2012). Second, it suggests that the use of BSC in the way that leads to enhanced financial performance (i.e. use for feedforward) requires high levels of managerial attention and employee engagement, resources that are commonly constrained in SMEs (Garengo et al. 2005).

We also found that SMEs using BSC for feedforward presented higher levels of exploitative innovation. Consequently, gains in efficiency that result from the use of BSC are not restricted to financial outcomes; they are also reflected in the incremental development of existing organizational capabilities. These findings are consistent with claims that increases in process management practises promote incremental innovation (Benner and Tushman 2003). Additionally, by highlighting the characteristics of BSC that provide innovation efficiency, our research illustrates a highly diffused managerial practice that can offer the necessary conditions for decentralized decision-making managed via formal structures and written plans that support superior ability to innovate (Cosh et al. 2012; Srećković 2017).

Contrary to our expectations, we did not find that the use of BSC by SMEs is negatively associated with exploratory innovation. Our primary analysis (shown in Table 5) suggests that the use of certain managerial practices might differently affect innovation outcomes in SMEs (Hervas-Oliver et al. 2016). First, this result differs from those of studies in large firms that point to the contributions of the use of BSC to the development of new capabilities (Grafton et al. 2010). Therefore, it validates our concern that prescriptions about the use of BSC put forward for large firms are not easily translated to SMEs. Second, this finding highlights the importance of differentiating the implications of BSC on innovation in terms of specific orientations (i.e. exploitative versus exploratory) and therefore introduces a key variable that explains previous claims about the desirable contribution of the BSC to innovation (e.g. Garengo et al. 2005; Bititci et al. 2012). Additional analysis without control variables shows a positive relationship between the use of BSC and exploratory innovations. We attribute this finding to the non-controlled effects of strategy, R&D sales, R&D collaboration and the intangible to total assets ratio. Previous literature has shown that such variables have positive effects on the ability of a firm to innovate. For instance, Eggers et al. (2014) argue that more collaboration in product development will support higher levels of exploratory innovation in SMEs.

In examining the performance implications of the relationship between the BSC and SMEs’ developmental stages, we found that more established SMEs attain higher financial performance. As per our previous arguments, and in line with the argument that the development stage moderates the relationship between planning practices and firm performance (Brinckmann et al. 2010), these results suggest that other managerial structures usually practised by established firms should be in place to support the effective use of BSC (López and Hiebl 2015). Additionally, our results suggest a less important role for the developmental stage of the SMEs than we initially expected, as we did not find that it moderated the relationship between the use of BSC and innovation, either exploitative or exploratory. These results reveal that the improvements in efficiency introduced by the use of BSC and reflected in exploitative innovations are not particular to either young or established SMEs. Furthermore, the results suggest that regardless of the SME’s stage of development, the use of BSC is not, by itself, sufficient to encourage and support the development of investigation, experimentation and risk-taking.

Some limitations of our study point to additional directions for future research. First, in this study, we regarded BCS as a multi-perspective framework that relies on a set of metrics. However, we did not explore the informational content within the BSC. Previous literature has suggested that the composition and presentation of metrics within the balanced scorecard have differential impacts on managers’ judgements (Cheng and Humphreys 2012). Further research could examine whether the different configurations of BSC could better explain variations in SME performance. Second, we developed our study using a sample composed of SMEs in the food and beverage industry, which is a mature, stable and capital-intensive industry. Given the specificities of our sample, generalization of the results of this study should be made with caution. It is likely that, in a context with more technologically intensive firms, the influence of BSC on innovation might be constrained. In this regard, Covin and Slevin (1989) highlight the significant role of informal controls (rather than formal controls) for SMEs operating in environments with high technological competition. Third, in our study, we examined BSC as an isolated practice. Most often, firms do not employ individual managerial practices as isolated systems (CIMA 2009) but rather tend to use numerous practices in combination—in the context of a complex set—that collectively constitute managerial packages (Malmi and Brown 2008). By taking a package approach, future research will be able to develop a broader understanding of the performance implications of the BSC. Fourth, in this research, we examined the effects of BSC on innovation, overlooking innovation initiatives that emerge beyond organizational boundaries (Spithoven et al. 2013). We used a control variable to account for the extent to which the SMEs in our sample collaborate with other firms in terms of innovation. Nevertheless, the understanding of whether and how BSC supports inter-organizational innovation projects was beyond the scope of our research. Given the importance of such collaborations for the development of innovations in SMEs, we encourage studies investigating the performance implications of BSC to account for its use in such collaborations. Finally, the results of this research are based on a survey and thus suffer from cross-sectional and survey-related limitations. Longitudinal research might provide additional support for our findings.

6 Conclusions

In sum, this study draws on the small business, organizational control and innovation literature to explain the effects of the use of BSC by SMEs. The results show that SMEs benefit from the use of BSC for feedforward control, such that firms that use it present higher financial performance and higher exploitative innovation outcomes. This positive effect on financial performance is stronger for more established firms. Consistent with the idea that the use of managerial planning practices supports firm efficiency (Benner and Tushman 2003; Brinckmann et al. 2010) and with prior case-based research that have noted the benefits of BSC, our study provides quantitative empirical evidence that BSC can play a relevant role in SMEs. Our research offers some meaningful implications for SME managers who wish to consider adopting and using BSC. In this sense, it shows that specific uses of BSC represent effective means of enhancing organizational efficiencies without apparent reductions in flexibility. Hence, our findings offer SME managers suggestions concerning which uses and designs of managerial practices might be suitable for pursuing specific strategic priorities.

Notes

Evidence shows that the BSC adoption rate is 60% among large firms and 25 to 31% among small and medium size firms (CIMA 2009).

It has been suggested that managers of large firms could address the efficiency-flexibility trade-off by promoting spatial separation (e.g., structurally separate R&D units) (Benner and Tushman 2003), temporal differentiation (Nickerson and Zenger 2002), or strategic alliance networks (Lin et al. 2007). The small business literature has shown that these options are less accessible to SMEs and that top management teams, and the managerial practices supporting their decision-making play a pivotal role in managing the trade-off (Lubatkin et al. 2006; Volery et al. 2015).

Even though early studies questioned the suitability of BSC for SMEs (McAdam 2000; Hoque 2003), more recent research developments on the adoption of managerial practices suggest that the adoption and use of BSC are related to the complexity of the firm rather than to size-related factors (Kallunki and Silvola 2008; Davila et al. 2009).

Admittedly, to be consistent with prior literature, these labels could also be ‘interactive’ and ‘diagnostic’ (Bisbe and Malagueño 2009; Koufteros et al. 2014). Interactive and diagnostic uses have been employed to examine managerial control practices in large firms. Whereas the interactive use of controls involves double-loop learning, the diagnostic use concerns single loop learning. We opt not to introduce these labels into our discussion of small business and instead base our types on the extant prior literature. Several researchers in the small business literature have shown that the behavioural and organizational effects of managerial practices are deeply associated with how they are used. Among those studies, analogous typologies were examined, including loose/flexible and tight (De Massis et al. 2015), organic and mechanistic (McAdam et al. 2014) and feedback and feedforward (Ebben and Johnson 2005).

The sample for this study is part of a larger research project. Only firms that reported 10 to 250 employees in their financial statements were selected for this research paper. We acknowledge that the reliance of this paper on a single industry constrains generalizations of our findings. An important advantage of this choice is that analysis of a single industry presents higher internal validity than multi-industry analysis, as a number of spurious effects can be better controlled (Ittner et al. 2003).

For comparability, we include the standardized variables in the models.

For content validity, we also asked in the survey whether the company had adopted budgets (the most extended control system among SMEs) and strategic planning, so that the respondents were aware that they were being asked about a balanced scorecard.

We thank an anonymous SBE reviewer for signalling to the importance of this variable in the research model.

The effect of innovation on the long-term profitability of a firm may be substantial; however, in this research, we only assess the performance implications of the use of BSC in the short- and mid-terms. Thus, the effects of innovation on financial performance are not tested.

To avoid issues of multicollinearity, variables for the use of BSC and development stage were mean centred before creating the interaction term.

We checked whether the incremental variances in the explained variables that stem from the control variables are statistically significant. In models 1 to 6, ΔR2 (ranging from 0.179 to 0.465) are significant to all cases (p < 0.01). ΔAdjusted R2 (ranging from 0.073 to 0.400) are also significant (p < 0.01), with the exception of ‘Perceived performance’ models.

References

Anderson, B. S., & Eshima, Y. (2013). The influence of firm age and intangible resources on the relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and firm growth among Japanese SMEs. Journal of Business Venturing, 28(3), 413–429. doi:10.1016/j.jbusvent.2011.10.001.

Ates, A., Garengo, P., Cocca, P., & Bititci, U. (2013). The development of SME managerial practice for effective performance management. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 20(1), 28–54. doi:10.1108/14626001311298402.

Benner, M. J., & Tushman, M. L. (2003). Exploitation, exploration, and process management: The productivity dilemma revisited. The Academy of Management Review, 28(2), 238–256 Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/30040711.

Biazzo, S., & Garengo, P. (2012). Performance measurement with the balanced scorecard. A practical approach to implementation within SMEs. Berlin: Springer ISBN 978-3-642-24761-3.

Biddle, G. C., Hilary, G., & Verdi, R. S. (2009). How does financial reporting quality relate to investment efficiency? Journal of Accounting and Economics, 48(2), 112–131. doi:10.1016/j.jacceco.2009.09.001.

Bisbe, J., & Malagueño, R. (2009). The choice of interactive control systems under different innovation management modes. European Accounting Review, 18(2), 371–405. doi:10.1080/09638180902863803.

Bisbe, J., & Malagueño, R. (2012). Using strategic performance measurement systems for strategy formulation: does it work in dynamic environments? Management Accounting Research, 23(4), 296–311. doi:10.1016/j.mar.2012.05.002.

Bititci, U., Garengo, P., Dorfler, V., & Nudurupati, S. (2012). Performance measurement: challenges for tomorrow. International Journal of Management Reviews, 14(3), 305–327. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2370.2011.00318.x.

Bititci, U. S., Garengo, P., Ates, A., & Nudurupati, S. S. (2015). Value of maturity models in performance measurement. International Journal of Production Research, 53(10), 3062–3085. doi:10.1080/00207543.2014.970709.

Branzei, O., & Vertinsky, I. (2006). Strategic pathways to product innovation capabilities in SMEs. Journal of Business Venturing, 21(1), 75–105. doi:10.1016/j.jbusvent.2004.10.002.

Brinckmann, J., Grichnik, D., & Kapsa, D. (2010). Should entrepreneurs plan or just storm the castle? A meta-analysis on contextual factors impacting the business planning-performance relationship in small firms. Journal of Business Venturing, 25(1), 24–40. doi:10.1016/j.jbusvent.2008.10.007.

Bromiley, P., & Harris, J. D. (2014). A comparison of alternative measures of organizational aspirations. Strategic Management Journal, 35(3), 338–357. doi:10.1002/smj.2191.

Busco, C., & Quattrone, P. (2015). Exploring how the balanced scorecard engages and unfolds: articulating the visual power of accounting inscriptions. Contemporary Accounting Research, 32(3), 1236–1262. doi:10.1111/1911-3846.12105.

Busenitz, L., & Barney, J. (1997). Differences between entrepreneurs and managers in large organizations: biases and heuristics in strategic decision making. Journal of Business Venturing, 12(1), 9–30. doi:10.1016/S0883-9026(96)00003-1.

Cardinal, L. B., Sitkin, S. B., & Long, C. P. (2004). Balancing and rebalancing in the creation and evolution of organizational control. Organization Science, 15(4), 411–431. doi:10.1287/orsc.1040.0084.

Cardon, M. S., & Stevens, C. E. (2004). Managing human resources in small organizations: What do we know? Human Resource Management Review, 14(3), 295–323. doi:10.1016/j.hrmr.2004.06.001.

Chang, Y.-Y., & Hughes, M. (2012). Drivers of innovation ambidexterity in small-to-medium-sized firms. European Management Journal, 30(1), 1–17. doi:10.1016/j.emj.2011.08.003.

Cheng, M. M., & Humphreys, K. A. (2012). The differential improvement effects of the strategy map and scorecard perspectives on managers’ strategic judgments. The Accounting Review, 87(3), 899–924. doi:10.2308/accr-10212.

Chowdhury, S. (2011). The moderating effects of customer driven complexity on the structure and growth relationship in young firms. Journal of Business Venturing, 26(3), 306–320. doi:10.1016/j.jbusvent.2009.10.001.

CIMA (2009). Research report: management accounting tools for today and tomorrow. Chartered Institute of Management Accountants. (Available from: http://www.cimaglobal.com/Documents/Thought_leadership_docs/CIMA%20Tools%20and%20Techniques%2030-11-09%20PDF.pdf). Accessed 02 July 2016.

Cooper, D. J., Ezzamel, M., & Qu, S. Q. (2017). Popularizing a management accounting idea: The case of the balanced scorecard. Contemporary Accounting Research, 34(2), 991–1025. doi:10.1111/1911-3846.12299.

Cosh, A. D., Fu, X., & Hughes, A. (2012). Organization structure and innovation performance in different environment. Small Business Economics, 39(2), 1–17. doi:10.1007/s11187-010-9304-5.

Covin, J. G., & Slevin, D. P. (1989). Strategic management of small firms in hostile and benign environments. Strategic Management Journal, 10(1), 75–87. doi:10.1002/smj.4250100107.

Cuerva, M. C., Triguero-Cano, Á., & Córcoles, D. (2014). Drivers of green and non-green innovation: empirical evidence in low-tech SMEs. Journal of Cleaner Production, 68, 104–113. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2013.10.049.

Danneels, E. (2002). The dynamics of product innovation and firm competencies. Strategic Management Journal, 23(12), 1095–1121. doi:10.1002/smj.275.

Davila, A., Foster, G., & Li, M. (2009). Reasons for management control systems adoption: Insights from product development systems choice by early-stage entrepreneurial companies. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 34, 322–347. doi:10.1016/j.aos.2008.08.002.

Davila, T., Epstein, M., & Shelton, R. (2012). Making innovation work: how to manage it, measure it, and profit from it. Upper Saddle River: Pearson Education ISBN-13: 978-0-13-149786-3.

De Geuser, F., Mooraj, S., & Oyon, D. (2009). Does the balanced scorecard add value? Empirical evidence on its effect on performance. European Accounting Review, 18(1), 93–122. doi:10.1080/09638180802481698.

De Massis, A., Frattini, F., Pizzurno, E., & Cassia, L. (2015). Product innovation in family vs. non-family firms: An exploratory analysis. Journal of Small Business Management, 53(1), 1–36. doi:10.1111/jsbm.12068.

Dillman, D. A. (2000). Mail and internet surveys: the tailored design method (2 ed). NewYork: Wiley ISBN-13: 978-0-470-03856-7.

Ebben, J. J., & Johnson, A. C. (2005). Efficiency, flexibility, or both? Evidence linking strategy to performance in small firms. Strategic Management Journal, 26(13), 1249–1259. doi:10.1002/smj.503.

Eggers, F., Kraus, S., & Covin, J. G. (2014). Traveling into unexplored territory: radical innovativeness and the role of networking, customers, and technologically turbulent environments. Industrial Marketing Management, 43(8), 1385–1393. doi:10.1016/j.indmarman.2014.08.006.

Eisenhardt, K. M., Furr, N. R., & Bingham, C. B. (2010). Microfoundations of performance: Balancing efficiency and flexibility in dynamic environments. Organization Science, 21(6), 1263–1273. doi:10.1287/orsc.1100.0564.

Evans, J. R. (2004). An exploratory study of performance measurement systems and relationships with performance results. Journal of Operations Management, 22(3), 219–232. doi:10.1016/j.jom.2004.01.002.

Evans, W. R., & Davis, W. D. (2005). High-performance work systems and organizational performance: the mediating role of internal social structure. Journal of Management, 31(5), 758–775. doi:10.1177/0149206305279370.

Fernandes, K. J., Rajab, V., & Whalley, A. (2006). Lessons from implementing the balanced scorecard in a small and medium size manufacturing organization. Technovation, 26(5–6), 623–634. doi:10.1016/j.technovation.2005.03.006.

Freel, M. S. (2000). Strategy and structure in innovative manufacturing SMEs: the case of an English region. Small Business Economics, 15(1), 27–45. doi:10.1023/A:1012087912632.

García-Teruel, P. J., & Martínez-Solano, P. (2007). Short-term debt in Spanish SMEs. International Small Business Journal, 25(6), 579–602. doi:10.1177/0266242607082523.

Garengo, P., & Bititci, U. (2007). Towards a contingency approach to performance measurement: an empirical study in Scottish SMEs. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 27(8), 802–825. doi:10.1108/01443570710763787.

Garengo, P., & Sharma, M. K. (2014). Performance measurement system contingency factors: a cross analysis of Italian and Indian SMEs. Production Planning and Control, 25(3), 220–240. doi:10.1080/09537287.2012.663104.

Garengo, P., Biazzo, S., & Bititci, U. S. (2005). Performance measurement systems in SMEs: a review for a research agenda. International Journal of Management Reviews, 7(1), 25–47. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2370.2005.00105.x.

Glaser, L., Fourné, S., & Elfring, T. (2015). Achieving strategic renewal: The multi-level influences of top and middle managers’ boundary-spanning. Small Business Economics, 45(2), 305–327. doi:10.1007/s11187-015-9633-5.

Golovko, E., & Valentini, G. (2011). Exploring the complementarity between innovation and export for SMEs' growth. Journal of International Business Studies, 42(2), 362–380. doi:10.1057/jibs.2011.2.

Gong, M. Z., & Ferreira, A. (2014). Does consistency in management control systems design choices influence firm performance? An empirical analysis. Accounting and Business Research, 44(5), 497–522. doi:10.1080/00014788.2014.901164.

Grafton, J., Lillis, A. M., & Widener, S. K. (2010). The role of performance measurement and evaluation in building organizational capabilities and performance. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 35(7), 689–706. doi:10.1016/j.aos.2010.07.004.

Gumbus, A., & Lussier, R. N. (2006). Entrepreneurs use a balanced scorecard to translate strategy into performance measures. Journal of Small Business Management, 44(3), 407–425. doi:10.1111/j.1540-627X.2006.00179.x.

Hervas-Oliver, J.-L., Sempere-Ripoll, F., & Boronat-Moll, C. (2016). Does management innovation pay-off in SMEs? Empirical evidence for Spanish SMEs. Small Business Economics, 47(2), 507–533. doi:10.1007/s11187-016-9733-x.

Hill, C. W. L., & Rothaermel, F. T. (2003). The performance of incumbent firms in the face of radical technological innovation. The Academy of Management Review, 28(2), 257–274 Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/30040712.

Hoque, Z. (2003). Total quality management and the balanced scorecard approach: a critical analysis of their potential relationships and directions for research. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 14(5), 553–566. doi:10.1016/S1045-2354(02)00160-0.

Hudson-Smith, M., & Smith, D. (2007). Implementing strategically aligned performance measurement in small firms. International Journal of Production Economics, 106(2), 393–408. doi:10.1016/j.ijpe.2006.07.011.

Ittner, C. D., Larcker, D. F., & Randall, T. (2003). Performance implications of strategic performance measurement in financial services firms. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 28(7–8), 715–741. doi:10.1016/S0361-3682(03)00033-3.

Jänkälä, S., & Silvola, H. (2012). Lagging effects of the use of activity-based costing on the financial performance of small firms. Journal of Small Business Management, 50(3), 498–523. doi:10.1111/j.1540-627X.2012.00364.x.

Jansen, J. J. P., Van den Bosch, F. A. J., & Volberda, H. W. (2006). Exploratory innovation, exploitative innovation, and performance: effects of organizational antecedents and environmental moderators. Management Science, 52, 1661–1674. doi:10.1287/mnsc.1060.0576.

Jones, O., & Macpherson, A. (2006). Inter-organisational learning and strategic renewal in SMEs: Extending the 4I framework. Long Range Planning, 39, 155–175. doi:10.1016/j.lrp.2005.02.012.

Kallunki, J. P., & Silvola, H. (2008). The effect of organizational life cycle stage on the use of activity-based costing. Management Accounting Research, 19(1), 62–79. doi:10.1016/j.mar.2007.08.002.

Kaplan, R. S., & Norton, D. P. (1996). The balanced scorecard. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

Kaynak, E., & Kara, A. (2004). Market orientation and organizational performance: a comparison of industrial versus consumer companies in mainland China using market orientation scale MARKOR. Industrial Marketing Management, 33(8), 743–753. doi:10.1016/j.indmarman.2004.01.003.

Koufteros, X., Verghese, A., & Lucianetti, L. (2014). The effect of performance measurement systems on firm performance: a cross-sectional and a longitudinal study. Journal of Operations Management, 32(6), 313–336. doi:10.1016/j.jom.2014.06.003.

Koskinen, K. U., & Vanharanta, H. (2002). The role of tacit knowledge in innovation processes of small technology companies. International Journal of Production Economics, 80(1), 57–64. doi:10.1016/S0925-5273(02)00243-8.

Leonard-Barton, D. (1992). Core capabilities and core rigidities: a paradox in managing new product development. Strategic Management Journal, 13(S1), 111–125. doi:10.1002/smj.4250131009.

Lin, Z. J., Yang, H., & Demirkan, I. (2007). The performance consequences of ambidexterity in strategic alliance formations: empirical investigation and computational theorizing. Management Science, 53(10), 1645–1658. doi:10.1287/mnsc.1070.0712.

López, O. L., & Hiebl, M. R. W. (2015). Management accounting in small and medium-sized enterprises: current knowledge and avenues for further research. Journal of Management Accounting Research, 27(1), 81–119. doi:10.2308/jmar-50915.

Lubatkin, M. H., Simsek, Z., Ling, Y., & Veiga, J. F. (2006). Ambidexterity and performance in small- to medium-sized firms: the pivotal role of TMT behavioral integration. Journal of Management, 32(5), 1–27. doi:10.1177/0149206306290712.

Malmi, T., & Brown, D. A. (2008). Management control systems as a package—opportunities, challenges and research directions. Management Accounting Research, 19, 287–300. doi:10.1016/j.mar.2008.09.003.

McAdam, R. (2000). Quality models in an SME context a critical perspective using a grounded approach. The International Journal of Quality & Reliability Management, 17(3), 305–323. doi:10.1108/02656710010306166.

McAdam, R., Antony, J., Kumar, M., & Hazlett, S. A. (2014). Absorbing new knowledge in small and medium-sized enterprises: a multiple case analysis of six sigma. International Small Business Journal, 32(1), 81–109. doi:10.1177/0266242611406945.

McCarthy, I. P., & Gordon, B. R. (2011). Achieving contextual ambidexterity in R&D organizations: a management control system approach. R&D Management, 41(3), 240–258. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9310.2011.00642.x.

Medori, D., & Steeple, D. (2000). A framework for auditing and enhancing performance measurement systems. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 20(5), 520–533. doi:10.1108/01443570010318896.

Micheli, P., & Manzoni, J. F. (2010). Strategic performance measurement systems: benefits, limitations and paradoxes. Long Range Planning, 43(4), 465–476. doi:10.1016/j.lrp.2009.12.004.

Minnis, M. (2011). The value of financial statement verification in debt financing: evidence from private U.S. firms. Journal of Accounting Research, 49, 457–506. doi:10.1111/j.1475-679X.2011.00411.x.

Nickerson, J. A., & Zenger, T. R. (2002). Being efficiently fickle: a dynamic theory of organizational choice. Organization Science, 13(5), 547–566. doi:10.1287/orsc.13.5.547.7815.

Nørreklit, H. (2000). The balance on the balanced scorecard critical analysis of some of its assumptions. Management Accounting Research, 11(1), 65–88. doi:10.1006/mare.1999.0121.

Nunnally, J. C. (1978). Psychometric theory. New York: McGraw Hill Book Company.

Patatoukas, P. N. (2011). Customer-base concentration: Implications for firm performance and capital markets. The Accounting Review, 87(2), 363–392. doi:10.2308/accr-10198.

Patel, P. C. (2011). Role of manufacturing flexibility in managing duality of formalization and environmental uncertainty in emerging firms. Journal of Operations Management, 29(1), 143–162. doi:10.1016/j.jom.2010.07.007.

Pavlov, A., & Bourne, M. (2011). Explaining the effects of performance measurement on performance. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 31(1), 101–122. doi:10.1108/01443571111098762.

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J.-Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioural research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879.

Rigby, D., & Bilodeau, B. (2015). Management tools & trends 2015. Bain & Company. http://www.bain.com/publications/articles/management-tools-and-trends-2015.aspx. Accessed 4 May 2017.

Rosenbusch, N., Brinckmann, J., & Bausch, A. (2011). Is innovation always beneficial? A meta-analysis of the relationship between innovation and performance in SMEs. Journal of Business Venturing, 26(4), 441–457. doi:10.1016/j.jbusvent.2009.12.002.

Schjoedt, L., & Bird, B. (2014). Control variables: use, misuse, and recommended use. In A. Carsrud & M. E. Brännback (Eds.), Handbook of research methods and applications in entrepreneurship and small business (pp. 136–155). Northampton: Edward Elgar ISBN:978-0-85793-504-5.

Spithoven, A., Vanhaverbeke, W., & Roijakkers, N. (2013). Open innovation practices in SMEs and large enterprises. Small Business Economics, 41(3), 537–562. doi:10.1007/s11187-012-9453-9.

Srećković, M. (2017). The performance effect of network and managerial capabilities of entrepreneurial firms. Small Business Economics, 1–18. doi:10.1007/s11187-017-9896-0.

Taylor, A., & Taylor, M. (2014). Factors influencing effective implementation of performance measurement systems in small and medium-sized and large firms: a perspective from contingency theory. International Journal of Production Research, 52(3), 847–866. doi:10.1080/00207543.2013.842023.

Tuomela, T. S. (2005). The interplay of different levers of control: a case study of introducing a new performance measurement system. Management Accounting Research, 16(3), 293–320. doi:10.1016/j.mar.2005.06.003.

Van Campenhout, G., & Van Caneghem, T. (2013). How did the notional interest deduction affect Belgian SMEs’ capital structure? Small Business Economics, 40, 1–23. doi:10.1007/s11187-011-9364-1.

Venturini, F. (2015). The modern drivers of productivity. Research Policy, 44(2), 357–369. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2014.10.011.

Vermeulen, P. A. M. (2005). Uncovering barriers to complex incremental product innovation in small and medium-sized financial services firms. Journal of Small Business Management, 43(4), 432–452. doi:10.1111/j.1540-627X.2005.00146.x.

Volery, T., Mueller, S., & Vonsiemens, B. (2015). Entrepreneur ambidexterity: a study of entrepreneur behaviours and competencies in growth-oriented small and medium-sized enterprises. International Small Business Journal, 33(2), 109–129. doi:10.1177/0266242613484777.

Voss, U., & Brettel, M. (2014). The effectiveness of management control in small firms: Perspectives from resource dependence theory. Journal of Small Business Management, 52(3), 569–587. doi:10.1111/jsbm.12050.

Wijbenga, F. H., Postma, T. J. B. M., & Stratling, R. (2007). The influence of the venture capitalist’s governance activities on the entrepreneurial firm’s control systems and performance. Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice, 31(2), 257–277. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6520.2007.00172.x.

Wouters, M., & Wilderom, C. (2008). Developing performance-measurement systems as enabling formalization: a longitudinal field study of a logistics department. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 33(4), 488–516. doi:10.1016/j.aos.2007.05.002.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge Margaret Abernethy, Shannon Anderson, Tiago Botelho, Victor Maas, David Naranjo-Gil and the participants of II Research Forum: Challenges in Management Accounting and Control at Seville for their helpful comments. We are also grateful for the comments of conference participants at the 2016 and 2017 European Accounting Association Congress, seminar participants at the Universidad Autónoma de Madrid and attendees of the XXII Workshop on Accounting and Management Control. We acknowledge financial assistance from the Spanish Ministry of Education and Science (ECO2016-77579-C3-3-P).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1

Appendix 2

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Malagueño, R., Lopez-Valeiras, E. & Gomez-Conde, J. Balanced scorecard in SMEs: effects on innovation and financial performance. Small Bus Econ 51, 221–244 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-017-9921-3

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-017-9921-3