Abstract

This paper examines antecedents of high-quality entrepreneurship in European countries before and after the financial crisis that burst in 2008. In a context of ambitious entrepreneurship, we consider three quality aspects of early-stage entrepreneurship referring to innovativeness, export orientation, and high-growth intentions of entrepreneurs. Using microlevel data retrieved from Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM) annual surveys, we investigate whether the role of gender, education, opportunity perception, and motives of early-stage entrepreneurs changes between crisis and noncrisis periods. Our results show that the perception of business opportunities has a particularly pronounced effect on high-quality entrepreneurship in adverse economic conditions. We also find that the beneficial effects of educational attainment on growth intentions strengthen in times of crisis. Finally, the gender effect on entrepreneurs’ high-growth intentions and export orientation appears to be stronger in the crisis period, implying that ambitious female entrepreneurship suffers more in the midst of crisis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Entrepreneurial activities involving the production and distribution of new or improved products and services in local, national, or international markets are considered critical for economic dynamism. Among the drivers of economic growth, entrepreneurship possesses a prominent place (Wennekers et al. 2005; Van Stel et al. 2005; Audretsch 2007). The main channels via which new business formation contributes to economic development refer to job generation (Birch 1979), increased competition (Agarwal and Gort 1996), and technological change that stimulates innovation (Baumol 2010) and productivity growth (Audretsch and Keilbach 2004).

On the other hand, entrepreneurship is highly dependent on the current economic climate and is expected to be significantly affected by crises (Klapper and Love 2011). In the light of the recent financial crisis which has been the most severe in decades with high costs for real economic activity (OECD 2012; ECB 2012), entrepreneurs have suffered a double shock due to the drastic drop in demand for goods and services and the emergence of credit crunch conditions (OECD 2009). Also, the global crisis exhibits a dramatic effect on the financing of innovative entrepreneurship (Lerner 2010). Evidently, entrepreneurship appears to interlink with the business cycle, though it is difficult to identify a clear causality trend in their relationship due to many direct and indirect links (Koellinger and Thurik 2012).

Stimulating entrepreneurship by increasing the number of start-ups (Audretsch et al. 2006) has been pursued in the context of typical policy programs in many countries facing adverse economic conditions. However, the global financial crisis underlined the need not only for creating a large quantity of entrepreneurial ventures in an economy but also for encouraging some “special” ventures that can be sustainable in adverse times and support growth and employment. As Shane (2009) has pointed out, creating typical start-ups is not the way to enhance economic growth and create jobs. Instead of subsidizing the formation of a typical start-up, he urges the need to focus on this subset of businesses with growth potential, since it is better to have a small number of high-growth firms rather than a large number of typical start-ups. Indeed, high-quality or ambitious entrepreneurship is likely to be more resilient to economic recessions constituting at the same time an important driver for economic development (Fritsch and Schroeter 2009, 2010; Autio and Acs 2010; Henrekson and Johansson 2010).

Yet, the empirical research focusing on this special form of entrepreneurship is rather limited, partly due to definitional and identification issues referring to ambitious entrepreneurs (Hermans et al. 2015). What is more, the literature on the antecedents of high-quality entrepreneurship in adverse economic conditions remains largely silent, failing to properly inform and guide relevant policy initiatives that could trigger economic recovery. The present paper intends to fill these gaps by exploring key quality aspects of early-stage entrepreneurship as well as the role of specific factors in creating ambitious new ventures especially during crisis. Utilizing an analytical framework of ambitious entrepreneurship, it contributes to the literature by considering three quality entrepreneurial dimensions, that is high-growth intentions (in terms of employment), innovativeness, and export orientation. Also our study argues on the significance of gender, education, opportunity perceptions and entrepreneurial motives for high-quality entrepreneurship and examines whether their role becomes stronger during crisis periods compared to noncrisis years. The analysis is based on individual-level data drawn from the annual Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM) surveys conducted in 32 European countries during the 2005–2011 period covering in total 24,327 early-stage entrepreneurs.

The paper is laid out as follows: Section 2 reviews the literature and formulates the main hypotheses to be tested; Section 3 describes the microlevel data, the sample, and the econometric methodology used; Section 4 presents and discusses the results of the empirical analysis; and Section 5 concludes and provides some policy implications.

2 Theoretical underpinnings and past evidence

2.1 Conceptual background on high-quality entrepreneurship

A considerable volume of research on high-growth firms examines the role of ambitions, expectations, and aspirations in entrepreneurial behavior and performance using alternative or complementary concepts, such as ambitious entrepreneurship (Stam et al. 2009; Stam et al. 2011; Hermans et al. 2015), high-expectation entrepreneurship (e.g., Valliere and Peterson 2009), high-aspiration entrepreneurship (e.g., Delmar and Wiklund 2008), high-potential entrepreneurship (e.g., Wong et al. 2005), high-impact entrepreneurship (Acs 2010), and strategic entrepreneurship planning (Levie and Autio 2011).

Irrespective of the label used, being also consistent with the conceptual framework developed by Hermans et al. (2015), we argue that all these concepts could fit into a unifying framework of high-quality or ambitious entrepreneurship incorporating key quality dimensions referring to growth intentions, innovativeness, and export orientation of entrepreneurs. Gundry and Welsch (2001) attempting to profile entrepreneurs with high-growth aspirations emphasize on their strategic intentions referring to market expansion and new technologies as well as their strong commitment to the success of their businesses. Along this line, Stam et al. (2012) define the ambitious entrepreneur as “someone who engages in the entrepreneurial process with the aim to create as much value as possible”, this value creation being expressed in terms of growth, innovation, or other performance indicators (Hermans et al. 2015).

Several studies build on the theory of planned behavior (Ajzen 1991) to explore the relations among motivations, perceptions, and actual behavior. This theory suggests that “intentions to perform behaviors of different kinds can be predicted with high accuracy from attitudes toward the behavior, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control; and these intentions, together with perceptions of behavioral control, account for considerable variance in actual behavior” (Ajzen 1991, p. 179). Drawing on the theory of planned behavior relevant research emphasizes the role of strategic dynamism and growth-seeking behavior in the entrepreneurial orientation, intentions, and realized growth outcomes (Estrin et al. 2013; Wiklund and Shepherd 2003). In addition, Guzmán and Santos (2001) consider the entrepreneurial motivation as a key determinant of entrepreneurial quality and actions. Arguing on the motivational dichotomy, they demonstrate that growth-oriented entrepreneurs have higher levels of intrinsic motivation while low-ambitious entrepreneurs are characterized by higher levels of extrinsic motivation. In this context, intrinsic motivation refers to items such as entrepreneurial vocation or the need for personal development, whereas extrinsic motivation is linked to the wealth-maximizing motive, economic necessity, or family tradition.

Moreover, Davidsson (1991) advocates that not only objective measures of ability, opportunity, and need are significant for firm growth but also the entrepreneur’s individual perceptions and growth expectations. Entrepreneurs with high aspirations in terms of producing new products, growing their business, or engaging in export-related activities are expected to contribute more to economic growth than their less ambitious counterparts (Bellu and Sherman 1995; Kolvereid and Bullvag 1996; Wiklund and Shepherd 2003). This has also significant policy implications. Given that it is hard to identify high-growth firms in advance, planning relevant policy measures should be based on growth ambitions of entrepreneurs and initial conditions of high-growth start-ups, so as to reward those early-stage entrepreneurs who react in the intended way (Stam et al. 2009). Subsidizing necessity-motivated entrepreneurs with low aspirations and expectations could potentially operate counter to the objectives of the policy (Stam et al. 2009; Bosma and Schutjens 2009). Indeed, many people who build a start-up with high ambitions about future growth and innovation eventually succeed in turning their venture into a gazelle or into a real innovative business (Bosma and Schutjens 2009).

On the other hand, we should note that ambitious entrepreneurship does not imply or automatically result in superior firm performance in terms of growth, innovation, or exports. New entrepreneurs might be overconfident in their own abilities or overoptimistic about future prospects, so that, despite their high aspirations and/or expectations, they do not ultimately reach their goals (Hermans et al. 2015; Koellinger et al. 2007). This incapacity to accurately perceive and assess market and competition conditions as well as the inability to manage internal and external threats to and opportunities for the firm at the time of start-up are the main reasons why growth ambition and actual firm growth are not perfectly correlated (Bosma and Schutjens 2009). Focusing on high-growth firms in Sweden, Daunfeldt and Halvarsson (2015) provide relevant evidence on the non-persistence of firms’ high growth, implying that most such firms are “one-hit wonders.”

In general, however, the statements and arguments in favor of ambitious entrepreneurship appear to have robust empirical validity in terms of predicting performance (Covin and Wales 2012). Recent research findings suggest that ambitious entrepreneurship is a more significant contributor to economic growth than entrepreneurial activity in general or self-employment per se (Bosma et al. 2009; Stam et al. 2009; Stam et al. 2011; Wong et al. 2005). More specifically, the growth intentions of entrepreneurs are found to be positively related to subsequent actual firm growth (Bellu and Sherman 1995; Kolvereid and Bullvåg 1996; Wiklund and Shepherd 2003). Gundry and Welsch (2001) find strong support for a causal link between high commitment to entrepreneurial ambitions and realized success along a number of dimensions. There is also empirical evidence of a positive effect of innovative motivation on post-entry performance (Davidsson 1991; Vivarelli and Audretsch 1998).

Despite the increasing research and policy interest, there is a need to broaden and enhance our knowledge on key aspects and behavior of high-potential new ventures, especially in turbulent economic environments. Furthermore, the underlying factors that are likely to drive ambitious entrepreneurship in times of crisis remain largely unexplored. To this end, this paper undertakes large-scale research to provide empirical evidence on quality dimensions of ambitious entrepreneurship and the evolution of their antecedents in the periods before and after the onset of the global crisis.

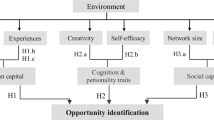

2.2 Antecedents of high-quality entrepreneurship

Entrepreneurship literature has examined a variety of factors as potential antecedents of ambitious entrepreneurship, although the evidence from crisis periods is scarce. In what follows, we utilize extant theoretical and empirical evidence to formulate hypotheses regarding the expected effects of specific personal as well as perceptual factors on high-quality entrepreneurship in the crisis period, compared to the noncrisis period.

Starting from the gender issue and its implications for high-quality entrepreneurship, various studies highlight the role of entrepreneurial intentions in performance differences between male- and female-owned firms (Davis and Shaver 2012; Gupta et al. 2009; Kolvereid 1996). Utilizing the theory of planned behavior (Ajzen 1991), Haus et al. (2013) attempt to explain gender differentials in entrepreneurial intentions on the basis of motivational constructs referring to the attitude toward starting a business, perceived expectations of others, and feelings of control over the creation process. Women do not usually start a business for a financial gain but to pursue intrinsic goals (e.g., independence, flexibility to interface family, and work commitments); thus, their businesses tend to be smaller, slower-growing, and less profitable as compared to male-owned businesses (Brush 1992; Rosa and Hamilton 1994; Welter et al. 2006; Gupta et al. 2009). Women are more likely than men to establish growth limits that reflect personal comfort thresholds and show greater concern about the risks of high-growth patterns (Cliff 1998). In general, female business owners are considered to be more risk averse, i.e., they have a lower tolerance for risk than male entrepreneurs (e.g., Jianakoplos and Bernasek 1998; Eckel and Grossman 2008; Davis and Shaver 2012) and, as a consequence, have lower expectations with respect to their business potential in terms of growth, innovativeness, or export activities.

Furthermore, female entrepreneurs appear to lack financial skills, thus being unable to fully exploit their innovation capability (Hisrich and Brush 1984; Lerner and Almor 2002). In addition, female entrepreneurs tend to be less export-oriented compared to male entrepreneurs (Du Rietz and Henrekson 2000; Orser et al. 2010). Notably, constraints in accessing resources, especially as regards debt and equity capital, are considered a key reason for the relatively low growth potential and generally low performance of women-owned firms (Alsos et al. 2006; Marlow and Patton 2005). The issue of gender discrimination in financing entrepreneurial attempts has been widely reported in the literature stressing the difficulty faced by female business owners to achieve finance from public as well as private funding sources (Stefani and Vacca 2013; Pines et al. 2010; Riding and Swift 1990; Orhan 2001; Coleman 2000; Calcagnini et al. 2015; De Bruin et al. 2006).

Accessing finance by women owners becomes even more difficult in times of crisis since, given the uncertainty and the low levels of liquidity, the financial institutions become reluctant to offer loans, especially to women’s businesses that tend to be small and vulnerable (Paul and Sarma 2013; Pines et al. 2010). The financial exclusion along with other forms of exclusion such as labor market exclusion or social exclusion (particularly relevant to women founders) results in a greater impact of the global economic crisis on female entrepreneurship compared to male entrepreneurship (Pines et al. 2010). Most importantly, in times of crisis, women are more likely to engage in self-employment or low-quality entrepreneurial endeavors compared to men due to limited livelihood choices (Paul and Sarma 2013; Allen et al. 2008; Arenius and Minniti 2005). Given the above, we expect women to be even more underrepresented in high-quality entrepreneurship during crisis periods.

-

H1: The gender effect on high-quality entrepreneurship is expected to be stronger in crisis periods compared to noncrisis periods.

Among the components of entrepreneurial human capital, the level of founders’ educational attainment has been considered as a significant factor for a venture’s growth potential, innovativeness, and internationalization. Guzmán and Santos (2001) consider education as a determinant of the entrepreneurial quality since highly educated individuals are characterized by increased intrinsic motivation and energizer behaviors; thus, they are most likely to be committed to entrepreneurial success. The role of college education in enhancing search skills, foresight, imagination, and computational and communication skills has been emphasized in the literature (Sapienza and Grimm 1997) being related to entrepreneurs’ growth aspirations (Autio and Acs 2007; Autio and Acs 2010; Verheul and Van Mil 2011). Similarly, there is evidence that post-secondary entrepreneurship education and training positively affects high-growth expectation business activity in high-income countries (Levie and Autio 2008). In addition, Wiklund and Shepherd (2003) reveal that education among other factors magnifies the effect of growth aspirations on the realization of growth.

Education has been also linked to the innovative potential of a new venture, since through formal education people develop intelligence, abstract thinking, and a strong interest to find general solutions to problems which are usually associated with high creativity and high probability to perceive innovative business ideas (Koellinger 2008). At the same time, knowledge building helps in identifying specific entrepreneurial opportunities in response to a technological change (Shane 2000). Business opportunities may exist in an international context as well and can be more effectively recognized and exploited by individuals with a high level of human capital (Ruzzier et al. 2007). Indeed, a positive relationship between educational level of owners/founders and the export performance of new ventures is commonly assumed in related studies (Manolova et al. 2002; Moini 1995).

Based on the framework of Guzmán and Santos (2001), it can be argued that during an economic crisis, the intrinsic motivation in well-educated individuals linked to their attempts to fulfill their aims in life may outweigh the extrinsic material-reward and wealth-seeking motives, since the credit squeeze and austerity measures across Europe could discourage wealth attainment. Thus, in adverse economic conditions, highly educated people driven by personal development and entrepreneurial aptitude are more likely—than less educated ones—to start a business with strong potential in terms of growth, innovation, and export orientation. From another perspective, individuals with relatively high levels of human capital are subject to higher opportunity costs due to more and better alternatives that are generally available to them (Shane and Venkataraman 2000). Consequently, the larger the alternative compensation, the more attractive must be the expected reward associated with business venturing in ordered for educated individuals to be induced in ambitious entrepreneurial attempts (Amit et al. 1995; Bhide 2000). In times of crisis, the absence of better alternatives for individuals with high levels of human capital is likely to reduce the opportunity cost of starting a high-potential business and thus encourage the pursuit of ambitious ventures.

-

H2: The effect of entrepreneurs’ educational attainment on high-quality entrepreneurship is expected to be stronger in crisis periods compared to noncrisis periods.

The role of subjective beliefs and perceptions in entrepreneurial behavior/activity has been acknowledged in economic theories of entrepreneurship (e.g., Kirzner 1979; Harper 1998) and largely supported by empirical evidence (Arenius and Minniti 2005; Koellinger et al. 2007; Minniti and Nardone 2007). Focusing on perceptual variables, motivation for starting a business has attracted significant interest due to its implications for the type and quality of entrepreneurial activity being developed. A strand of literature emphasizes opportunity vs. necessity motives (Reynolds et al. 2002; Acs 2006), a distinction being associated with pull vs. push entrepreneurship, respectively, which has been also explored in the ambitious entrepreneurship context (Van Gelderen et al. 2005).

The literature referring to entrepreneurial career reasons reports a number of factors operating as pull motives (e.g., independence, freedom, challenge, autonomy, recognition, and status), autonomy, or independence being the most frequently cited (Shane et al. 1991; Kolvereid 1996; Carter et al. 2003; Van Gelderen and Jansen 2006). Pull motives attract people into entrepreneurship and are closely related to the identification and exploitation of market opportunities. Verheul and Van Mil (2011) show that opportunity-driven entrepreneurs are more likely to feed ambition than necessity-driven entrepreneurs, since they exhibit high-growth aspirations. Thus, opportunity motives are linked to high-quality entrepreneurship and are found to positively affect countries’ technological and innovative performance (Kontolaimou et al. 2016).

However, individuals may also be pushed into entrepreneurship (Thurik et al. 2008) due to economic necessity. Indeed, when unemployment is increasing, becoming an entrepreneur depends, among others, on the extent to which starting a business is perceived as a viable second best alternative to unemployment (Landini et al. 2015). Necessity-motivated entrepreneurs may face higher constraints with respect to access to human capital, financial capital, technology, and other resources, which are likely to undermine their potential for generating innovations and job growth and for building competitive advantages needed for export (Hessels et al. 2008). Consequently, they tend to have lower aspiration levels than opportunity-motivated entrepreneurs (Reynolds et al. 2002) implying lower expectations for innovation and growth in terms of jobs and export (Hessels et al. 2008).

At the same time, many entrepreneurship scholars distinguish opportunity perception as a critical part of the entrepreneurship process (e.g., Bhave 1994; Shane and Venkataraman 2000). Perception of entrepreneurial opportunities refers to the identification of business opportunities for the creation of new ventures and it is usually linked to “entrepreneurial alertness” (Ardichvili et al. 2003; Kirzner 1973). An entrepreneur is in a situation of entrepreneurial alertness when she is sensitive toward changes of political, economic, social, or technological nature in the business environment, which may signal unmet needs in the market. Opportunity perception and identification play a critical role in ambitious entrepreneurship. Opportunities along with growth intentions and resources are considered necessary conditions in order for a new business to grow (Stam et al. 2009). In the conceptual framework developed by Hermans et al. (2015), ambitious entrepreneurs exploit opportunities and access resources they identify in their environment in order to realize their growth expectations. Along these lines, Stam et al. (2011) suggest that there is limited likelihood for low-ambitious entrepreneurs to be involved in a process of opportunity discovery and for their actions to have an effect on the restructuring and diversification of entrepreneurial and production systems.

In addition, the perception of business opportunities appears to be significant for innovative entrepreneurship, since it might require individual access to existing information in the environment as well as individual creativity and novelty (Koellinger 2008). Opportunity recognition is crucial for the innovativeness of entrepreneurial ventures being a part of a complex and interactive process in which the entrepreneur, the knowledge base of the venture, and the technology are engaged. Many studies emphasize also the significance of identifying and exploiting opportunities for international exchange in the internationalization process of new ventures (Di Gregorio et al. 2008; Mathews and Zander 2007).

Business opportunities due to unmet needs and gaps in markets are likely to arise in turbulent economic environments where the restructuring in many markets is expected to take place (Leibenstein 1968). Crisis-hit economies often undertake several institutional reforms and restructuring in both labor and product markets being conducive to a high degree of environmental dynamism which is likely to positively affect the level of growth expectations and realizations of entrepreneurs (Wiklund and Shepherd 2003). Thus, in those economies, high-growth opportunities are more widely available, leaving more space for incremental innovation and cross-border activities. Utilizing the theoretical grounding of Leibenstein (1968), Levie and Autio (2008) in the context of the GEM modelFootnote 1 argue that opportunities appear when the gaps and impediments in markets exist. In times of crisis, where the business environments undertake significant changes and the transformation of the markets give rise to increased gaps and impediments, ambitious entrepreneurs are most likely to identify and take advantage of relevant opportunities, acting as potential gap fillers. Thus, in economies hit by the crisis, a higher number of ambitious opportunity-driven entrepreneurs may be in fact engaged in high-quality entrepreneurial endeavors in comparison to countries that are not under crisis. Given the above, we form the following twofold hypothesis.

-

H3a: The effect of opportunity-based motives on high-quality entrepreneurship is expected to be stronger in crisis periods compared to noncrisis periods.

-

H3b: The effect of opportunity perceptions on high-quality entrepreneurship is expected to be stronger in crisis periods compared to noncrisis periods.

3 Data and methodology

The dataset used in this paper draws upon the GEM datasetsFootnote 2 which represent a unique empirical instrument that provides an annual harmonized assessment of the national level of early-stage entrepreneurial activity in a wide set of countries (see Reynolds et al. 2005). For the purpose of this paper, we focus on early-stage entrepreneurs who involve nascent and new entrepreneurs. Nascent entrepreneurs are those individuals that are actively involved in setting up a business they will own or co-own, but this business has not yet paid salaries, wages, or any other payments to the owners for more than 3 months. New entrepreneurs are those who own and manage a running business that has paid salaries, wages, or any other payments to the owners for more than 3 months but not more than 42 months.

We use data from the GEM surveys over a 7-year time period, from 2005 to 2011, for 32 European countriesFootnote 3 that have at least once participated in an annual survey. The total size of the available sample is 24,327 early-stage entrepreneurs. The overall period is divided into two subperiods, that is the noncrisis period including the years 2005–2008 and the crisis period referring to the years 2009–2011 following the crisis outbreak.Footnote 4 Of course, both the time frame and the depth of the crisis had and still have, very different patterns in the various countries included in the analysis. Still, one could argue that for almost all European countries that are used in our analysis, the business environment in the 2009–2011 period was clearly much more volatile and uncertain than that during 2005–2008, as economic conditions had worsened across Europe.

Table 1 reports the number of early-stage entrepreneurs per country for the total period as well as for the crisis and noncrisis periods. For the vast majority of countries, data are available for both examined subperiods with the exception of five countries (Austria, Poland, Slovakia, Lithuania, Montenegro).Footnote 5 The sample size per country is related to the original samples which were used in the GEM survey and is not associated with any obvious country size characteristics. Therefore, sample sizes may substantially differ across countries, as shown in Table 1.

A specific set of new venture tiers are used as dependent variables in our analysis, representing three quality dimensions of early-stage entrepreneurship, as described below.

Growth intentions (GR)

The early-stage entrepreneur makes a rough estimation about the future prospects of his/her venture in terms of employment, stating the number of employees (apart from the owners) that she expects to be working in the venture after 5 years. The corresponding ordered variable takes the value of 1 if no new jobs are expected to be created, 2 if 1–5 jobs are expected to be created, 3 if the entrepreneur believes that his/hers venture will create 6–19 jobs in a 5-year time frame, and 4 in the case of the corresponding number of expected new jobs is above 20, i.e., in the case of firms with high-growth expectations. This variable is consistent with the literature on growth ambitions, intentions, aspirations, or expectations as discussed in Section 2.1 and has been frequently used by GEM-related studies (e.g., Autio 2007; Wong et al. 2005; Levie and Autio 2011).

Innovativeness (INNO)

The early-stage entrepreneur provides her view on how many (all, some, or none) of potential customers would consider their product or service new and unfamiliar, thus indicating the degree of product/service innovativeness. The corresponding variable is ordered taking the values of 1 in the case of “none,” 2 in the case of “some,” and 3 in the case of “all potential customers.” Evidently, each category implies a qualitatively greater degree of novelty than the preceding one, as perceived by the respondent. We have used this variable following other studies which examine early-stage entrepreneurs’ innovative activities based on GEM data (Koellinger 2008; Bosma and Schutjens 2009). Even though this measure may not be perfect in capturing the innovative dimension of high-quality entrepreneurship, it gives some indication of the innovative ambitions of individuals, in terms of new product market combinations (Bosma and Schutjens 2009).

Export orientation (EXP)

The early-stage entrepreneur is asked to estimate the proportion of the (potential) customers who normally live outside his/her country. This is a proxy for export intensity of the venture. This variable is an ordered one, taking the value of 1 if none of the customers live outside the country, 2 if the proportion is between 1 and 10 %, 3 if the proportion varies between 11 and 25 %, 4 if the proportion is 26–75 %, and 5 in the case of high exporting ventures (more than 75 % of customers live abroad).

Table 2 presents the distribution of the three dependent variables by category.

To test the hypotheses provided in Section 2.2, we include in our empirical models four independent variables referring to the gender, education, motives, and opportunity perceptions of early-stage entrepreneurs as defined in Table 3. We also control for a variety of sociodemographic characteristics, i.e., age and household income as well as perceptual attributes, that is self-confidence, fear of failure, and knowing other entrepreneurs. Three additional control variables are included concerning the technology used for the production of the product/service, the competition intensity in the industry, as well as the stage of countries’ economic development. A detailed description of the explanatory variables is provided in Table 3, while summary statistics for all variables are provided in Table 4. In addition, the correlation matrix in Table 5 indicates the absence of any significant correlation among the independent variables used, which in turn ensures that the econometric estimates are not biased due to multicollinearity problems.

The econometric analysis is based on the estimation of the following three equations corresponding to the examined dimensions of high-quality entrepreneurship:

In Eq. (1) the dependent variable, GR i , j , t , stands for the firm’s job growth as expected by entrepreneur i, in country j, at time t. The explanatory variables of gender, educational attainment, entrepreneurial motives, and opportunity perception of entrepreneur i, in country j, at time t are denoted by Gend i , j , t ,Edu i , j , t ,Mot i , j , t and Opport i , j , t respectively. Z i , j , t is a vector of the control variables as described above; u i , j , t is the random error term assumed to be normally distributed. Accordingly, Eqs. (2) and (3) complement the profile of the early-stage entrepreneur referring to the determinants of innovativeness (INNO i , j , t ) and the expert orientation (EXP i , j , t ) respectively. Parameters β, γ, and δ denote the marginal effects to be estimated. Each of the three equations is estimatedFootnote 6 for the noncrisis (2005–2008) and crisis (2009–2011) periods to identify potential differences in the effects of the variables of interest.

Since the quality dimensions of early-stage entrepreneurs are measured by categorical ordinal variables, we employ ordered probit models to estimate the effects of the explanatory variables on the probabilities of high-growth intentions, entrepreneurial innovativeness, and export orientation corresponding to Eqs. (1)–(3), respectively.

4 Results

The estimation results for the crisis and noncrisis periods and for the three quality entrepreneurial dimensions are reported in Table 6.Footnote 7 The table presents the marginal effects of the regressor variables on the probability associated with the highest category of the examined quality characteristic relative to the lowest category, i.e., the probability of high-growth expectations (20 expected new jobs in 5 years’ time) relative to no new jobs, the probability of high innovation (product or service is new to all potential customers) relative to no innovation (product or service is new to none of the customers), or the probability of high export orientation (more than 75 % of customers live abroad) relative to no export orientation (none of the customers live abroad).Footnote 8 We have to note here that our sample based on which our regression models are estimated comprises exclusively early-stage entrepreneurs.

Focusing on the first variable of interest, that is gender, we observe that it negatively affects the likelihood of being an ambitious entrepreneur in terms of growth intentions and export orientation in both crisis and noncrisis periods. The negative sign is in accordance with empirical evidence suggesting that female entrepreneurs are less likely to be engaged in growth-oriented (Brush 1992; Rosa and Hamilton 1994; Cliff 1998) or export-oriented businesses (Du Rietz and Henrekson, 2000). Interestingly, in both cases, the negative effect appears to be stronger in the crisis period than in the noncrisis years. More specifically, we find that being a female rather than a male entrepreneur decreases the probability of high growth-intended and export-oriented entrepreneurship by 6 percentage points and 2 percentage points, respectively, during the crisis period. The marginal effect in the crisis period appears to be higher by more than 2 percentage points compared to the noncrisis period in the case of high-growth intentions, while it is almost double as the one in the noncrisis years for export-oriented entrepreneurship (Table 6). These differences are statistically significant as confirmed by the corresponding t tests presented in Table 7 (first and third rows). Thus, we find that hypothesis H1 is indeed valid for the cases of high-growth and export-oriented entrepreneurship. Women may be even less ambitious or encounter increased difficulties in crisis periods failing to establish a business with a strong growth and export-oriented potential.

Educational attainment is found to positively affect all forms of high-quality entrepreneurship in times of crisis. The positive role of formal education has been empirically explored and supported by many studies focusing on entrepreneurs’ growth aspirations (Autio and Acs 2010; Verheul and Van Mil 2011), innovation entrepreneurial outcomes (e.g., Koellinger 2008) and internationalization strategies and export performance of new ventures (Manolova et al. 2002; Moini 1995; Westhead et al. 2003). Notably, our results show that education in the pre-crisis years has no significant effect on the probability of being an entrepreneur with high-growth intentions, while the corresponding effects in the cases of innovative and export-oriented entrepreneurship are smaller compared to the crisis period.

The reported differences in the marginal effects between the examined periods are strongly validated by the t tests (see Table 7) in the case of growth-intended (at 1 % level of significance) entrepreneurs. Therefore, hypothesis H2 is confirmed only for entrepreneurs with high-growth intentions. A possible explanation based on opportunity cost arguments related to ambitious educated entrepreneurs (Amit et al. 1995; Bhide 2000) may suggest that the absence of work options with high rewards for highly educated individuals in times of crisis is likely to encourage high-growth venturing due to reduced opportunity costs of starting such a business in adverse economic conditions.

With regard to opportunity-related perceptual attributes, results in Table 6 indicate that the likelihood of being an ambitious entrepreneur in times of crisis is greater for those individuals who are opportunity—rather than necessity—motivated and those who perceive better opportunities in the near future. These factors appear to be also significant in the pre-crisis period for entrepreneurs with high-growth intentions and innovativeness but not for export-oriented entrepreneurship. The differences between the two subperiods are particularly evident in the case of opportunity perception which appears to play a more significant role for all three dimensions of high-quality entrepreneurship in adverse economic conditions than in normal times.

The t tests provided in Table 7 confirm the stronger marginal effect of entrepreneurial motives on the probability to be an export-oriented entrepreneur in the crisis period comparing to the noncrisis period. Decreased demand and reduced disposable incomes in certain areas of Europe seem to urge opportunity-motivated entrepreneurs to more often pursue cross-border strategies during the crisis years than before. However, the corresponding effects do not appear to be statistically different between the examined periods in the cases of the other two forms of high-quality entrepreneurship (Table 7). Thus, our results provide little support for hypothesis H3a confirming the existence of a stronger effect of opportunity-based motives in the crisis period—in relation to the noncrisis period—only for export-oriented entrepreneurs.

On the other hand, the results in Table 6 along with the t tests in Table 7 provide full support for hypothesis H3b indicating that early-stage entrepreneurs who can perceive business opportunities in the near future are even more likely to be engaged in ambitious entrepreneurial activities in adverse times than in noncrisis periods. This may be explained by the fact that in turbulent economic environments where market restructuring and institutional reforms usually take place, business opportunities may emerge due to unmet needs and gaps that arise in the markets (Leibenstein 1968; Levie and Autio 2008; Wiklund and Shepherd 2003). Thus, there is increased likelihood for entrepreneurs who perceive these opportunities to fill the respective gaps in the markets and to engage in high-quality entrepreneurial endeavors.

Finally, with respect to the control variables that may affect the likelihood of engaging in ambitious entrepreneurship during the crisis and noncrisis periods, we find that most of them matter at least for a type of high-quality entrepreneurship in both periods under study. In particular, when entrepreneurs have a high degree of income, utilize new technology, and know other entrepreneurs, their ambitious chances appear to improve. On the contrary, age,Footnote 9 fear of failure, competition intensity, and GDP per capita are negatively related to ambitious entrepreneurship in most of our models. The fear of failure is usually linked to risk aversion that may characterize early-stage entrepreneurs (Arenius and Minniti 2005). Entrepreneurs who believe that the probability of failure is high are less likely to start an ambitious new business. Regarding GDP per capita, the result might indicate that in developed countries (higher GDP per capita), with established business sectors and mature market structures, it seems more difficult to create a new venture that could grow quickly and lead the market. On the other hand, in developing countries (lower GDP per capita), markets may still continue to take shape after being recently liberalized and/or entry barriers have just been removed. So new ventures that are created could grow more easily and take a leading position in an emerging market.

5 Concluding remarks

Within the extensive research on entrepreneurship, ventures with special performance in terms of growth ambitions, innovation, or internationalization have attracted increased attention since they are linked to high productivity, job creation, and development. In the light of the recent financial crisis and the following recessionary economic cycle that affected most European countries, the role of such ventures appears to be even more crucial. However, our knowledge is still inadequate regarding the particularities and drivers of high-quality entrepreneurship especially in times of crisis.

Utilizing a conceptual framework of ambitious entrepreneurship which recognizes the interdisciplinary character of entrepreneurial behavior, elements from diverse theories (e.g., theory of planned behavior, theory of motivational dichotomy) are utilized to explore ambitious entrepreneurship in terms of high-growth intentions, innovativeness, and export orientation. An ambitious entrepreneur has a high commitment to entrepreneurial success and he/she intends to maximize value creation expressed in terms of growth, innovation, and internationalization. From this perspective, entrepreneurs’ intentions, aspirations, expectations, and motivation are particularly relevant. In this context, we investigate whether the impact of key factors (gender, education, opportunity perception, and entrepreneurial motives) on high-quality entrepreneurship is differentiated during crisis periods as compared to noncrisis periods, an issue on which the relevant literature remains largely silent. To this end, we use individual data drawn from the annual GEM surveys conducted in 32 European countries during the 2005–2011 period.

Estimation results point to opportunity perceptions as a key driver of any form of high-quality entrepreneurship, being particularly relevant for ambitious early-stage entrepreneurs in adverse economic conditions. Entrepreneurs committed to high-quality venturing appear to perceive opportunities even in times of crisis and act as gap fillers exploiting the gaps and unfulfilled market needs that arise due to the restructuring and transformation of labor and product markets in crisis-hit economies. This may have significant policy implications in the sense that when an economy is facing a downturn, promoting structural reforms in various labor or product markets (i.e., deregulation, liberalization, openness, licensing) usually creates new conditions in the market. In these new market conditions, various business opportunities may emerge providing incentives for potential entrepreneurs to pursue a sustainable business path.

We also find that the beneficial effects of educational attainment on entrepreneurs’ growth intentions strengthen in times of crisis in relation to noncrisis periods. The greater the proportion of highly educated individuals, the more likely it is that some will start a business with high expectations in terms of employment growth even in adverse economic conditions. Thus, from a policy perspective, emphasis should be placed in the development of strong education systems oriented to the establishment of entrepreneurial universities which in turn will provide knowledge and skills to their graduates on creating new high-quality ventures. Not everyone will or should become entrepreneur. But developing the necessary skills will affect a major pool of well-educated people to think about this option even in times of crisis and hopefully be engaged in viable ventures that could support growth and employment, especially in crisis-hit economies.

Our findings also provide further insight with respect to high-quality female entrepreneurship. The gender effect on entrepreneurs’ high-growth intentions and export orientation appears to be stronger in the crisis period, indicating that ambitious female entrepreneurship suffers more in times of crisis, at least in terms of job growth ambitions and export activities. Especially in recent years, where female unemployment rates have been significantly increased in many European countries, stimulating female entrepreneurship appears a high priority within policy programs at national and EU level. In this direction, some incentives toward women entrepreneurs may refer to accessing alternative financial sources (e.g., hybrid capital, crowdsourcing, financial engineering tools), development of mentoring/coaching aiming to support women entrepreneurs, etc.

Overall, from a policy perspective, our findings imply that encouraging and supporting high-quality early-stage entrepreneurship requires adequate knowledge on its quality dimensions, particularities, and antecedents. The main policy aim of entrepreneurship should not just be an algebraic increase of the number of start-ups that are created in an economy but an effort to affect the quality characteristics of these ventures, so they can be viable, support sustainable growth, and provide jobs in an economy. This implication is particularly significant for designing policy strategies and tools in adverse economic conditions, where, on the one hand, there are increased financial constraints and, on the other, the need to achieve economic recovery is imperative.

Thus, given the critical role that ambitious entrepreneurs are likely to perform in times of crisis, creating the right conditions for the emergence and support of innovative, high-growth and export-driven new ventures may be a selective and more effective growth strategy. In this direction, policy priorities should be given to the implementation of structural reforms in product and labor markets, establishment of entrepreneurial universities, and support of female entrepreneurship. These actions could also mitigate the effect of fear of failure on ambitious entrepreneurship as they may reduce the risk of starting a new business. Such mechanisms and policy tools may help in nurturing and leveraging those crucial quality entrepreneurial elements that will effectively foster value creation of new ventures and increase their multiplying effect on economic growth in Europe.

Notes

The collection and analysis of the GEM data are framed around the GEM model (developed in 1999 by Paul Reynolds) which proposes relationships between established and new business activity and economic growth at the national level and also proposes antecedents of these two forms of entrepreneurial activity.

GEM builds on an adult population survey undertaken annually since 1999 on a minimum of 2000 respondents in more than 50 countries globally.

GEM is a global survey providing data on European as well as non-European countries such as the USA. However, we focus our analysis only on Europe in order to have a more homogeneous group of countries and have a more concrete ground for our argumentation. Most of the countries used in our paper belong also in a monetary union, so their economies are—at least to some extent and especially in the field of financing which is crucial for early-stage entrepreneurship—affected by the economic situation of certain members, as the recent crisis has shown for the European periphery. Comparing Europe with, i.e., the USA or Japan would be very interesting but it would require a different approach and additional levels of analysis.

Our decision to consider 2008 as a threshold for defining the crisis and noncrisis periods is based on key events and impacts on European economies related to crisis, such as the collapse of Lehman Brothers in September 2008, the banking system bailouts in a number of European countries since early 2009, and the subsequent slowdown of real economic activity which for a number of European countries resulted in a deep and prolonged recession. We consider 2009 as the first year of the crisis period in Europe since in that year almost all European countries experienced a sharp recession after positive GDP growth rates in the previous years (European Commission 2012).

Excluding these five countries from the sample does not change the empirical results in any significant way.

Since the set of regressors is the same in all three equations, it is demonstrated that estimations derived from equation-by-equation regressions turn out to be equivalent to those based on seemingly unrelated regressions (Davidson and MacKinnon 1993).

Including country dummies in our models does not change the results in any significant way. The same holds, if we cluster at the country level, suggesting that intra-cluster correlation in errors is not a serious problem for our data.

For the purposes of the paper and for presentation reasons, we report the results referring to high-quality entrepreneurship that is most ambitious entrepreneurs in terms of job growth expectations, innovativeness, and export orientation. The results for all other categories of the dependent variables are available upon request.

Including also age-squared to control for quadratic effects of age on ambitious entrepreneurship eliminates any significant age effect on entrepreneurs’ growth intentions and innovativeness. On the contrary, in the case of export orientation, a linear (negative) as well as a quadratic (positive) effect of age is found statistically significant in both examined periods. The rest of the results are not affected in any way.

References

Acs, Z. J. (2010). High-impact entrepreneurship (pp. 165–182). New York: Handbook of entrepreneurship research. doi:10.1007/978-1-4419-1191-9_7.

Acs, Z. J. (2006). How is entrepreneurship good for economic growth? Innovations, 1(1), 97–107. doi:10.1162/itgg.2006.1.1.97.

Agarwal, R., & Gort, M. (1996). The evolution of markets and entry, exit and survival of firms. Review of Economics and Statistics, 78(3), 489–498. doi:10.2307/2109796.

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. doi:10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T.

Allen, I.E., Elam, A., Langowitz, N., & Dean, M. (2008). 2007 report on women and entrepreneurship. Global Entrepreneurship Monitor.

Alsos, G. A., Isaksen, E. J., & Ljunggren, E. (2006). New venture financing and subsequent business growth in men-and women-led businesses. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 30(5), 667–686. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6520.2006.00141.x.

Amit, R., Muller, E., & Cockburn, I. (1995). Opportunity costs and entrepreneurial activity. Journal of Business Venturing, 10(2), 95–106. doi:10.1016/0883-9026(94)00017-O.

Ardichvili, A., Cardozo, R., & Ray, S. (2003). A theory of entrepreneurial opportunity identification and development. Journal of Business Venturing, 18(1), 105–123. doi:10.1016/S0883-9026(01)00068-4.

Arenius, P., & Minniti, M. (2005). Perceptual variables and nascent entrepreneurship. Small Business Economics, 24(3), 233–247. doi:10.1016/S0883-9026(01)00068-4.

Audretsch, D. B. (2007). Entrepreneurship capital and economic growth. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 23(1), 63–78. doi:10.1093/oxrep/grm001.

Audretsch, D., & Keilbach, M. (2004). Entrepreneurship capital and economic performance. Regional Studies, 38(8), 949–959. doi:10.1080/0034340042000280956.

Audretsch, D., Keilbach, M., & Lehmann, E. (2006). Entrepreneurship and economic growth. New York: Oxford University Press.

Autio, E. (2007). Global entrepreneurship monitor: 2007 global report on high-growth entrepreneurship. Babson Park MA: Babson College.

Autio, E., & Acs, Z. (2010). Intellectual property protection and the formation of entrepreneurial growth aspirations. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 4(3), 234–251. doi:10.1002/sej.93.

Autio, E., & Acs, Z. J. (2007). Individual and country-level determinants of growth aspiration in new ventures. Frontiers of Entrepreneurship Research, 27. doi:10.1002/sej.93.

Baumol, W. J. (2010). The microtheory of innovative entrepreneurship. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. doi:10.1007/s00712-011-0195-y.

Bellu, R. R., & Sherman, H. (1995). Predicting firm success from task motivation and attributional style: a longitudinal study. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 7(4), 349–364. doi:10.1080/08985629500000022.

Bhave, M. P. (1994). A process model of entrepreneurial venture creation. Journal of Business Venturing, 9(3), 223–242. doi:10.1016/0883-9026(94)90031-0.

Bhide, A. (2000). The origin and evolution of new businesses. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Birch, D. (1979). The job generation process. Cambridge: MIT Program on Neighborhood and Regional Change.

Bosma, N., & Schutjens, V. (2009). Determinants of early-stage entrepreneurial activity in European regions; distinguishing low and high ambition entrepreneurship. In D. Smallbone, H. Landstrom, & D. J. Evans (Eds.), Making the difference in local, regional and national economies: frontiers in European entrepreneurship research (pp. 49–77). Cheltenham (UK); Northampton, MA (USA): Edward Elgar. doi:10.4337/9781849802369.

Bosma, N., Schutjens, V., & Stam, E. (2009). Entrepreneurship in European regions. In J. Leitao & R. Baptista (Eds.), Public policies for fostering entrepreneurship (pp. 59–90). New York: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-1-4419-0249-8_4.

Brush, C. G. (1992). Research on women business owners: past trends, a new perspective and future directions. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 16(4), 5–30.

Calcagnini, G., Giombini, G., & Lenti, E. (2015). Gender differences in bank loan access: an empirical analysis. Italian Economic Journal, 1(2), 1–25. doi:10.1007/s40797-014-0004-1.

Carter, N. M., Gartner, W. B., Shaver, K. G., & Gatewood, E. J. (2003). The career reasons of nascent entrepreneurs. Journal of Business Venturing, 18(1), 13–39. doi:10.1016/S0883-9026(02)00078-2.

Cliff, J. E. (1998). Does one size fit all? Exploring the relationship between attitudes towards growth, gender, and business size. Journal of Business Venturing, 13(6), 523–542. doi:10.1016/S0883-9026(97)00071-2.

Coleman, S. (2000). Access to capital and terms of credit: a comparison of men- and women-owned small businesses. Journal of Small Business Management, 38(3), 37–52.

Covin, J. G., & Wales, W. J. (2012). The measurement of entrepreneurial orientation. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 36(4), 677–702. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6520.2010.00432.x.

Daunfeldt, S. O., & Halvarsson, D. (2015). Are high-growth firms one-hit wonders? Evidence from Sweden. Small Business Economics, 44(2), 361–383. doi:10.1007/s11187-014-9599-8.

Davidson, R., & MacKinnon, J. G. (1993). Estimation and inference in econometrics. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1002/jae.3950100309.

Davidsson, P. (1991). Continued entrepreneurship: ability, need, and opportunity as determinants of small firm growth. Journal of Business Venturing, 6(6), 405–429. doi:10.1016/0883-9026(91)90028-C.

Davis, A. E., & Shaver, K. G. (2012). Understanding gendered variations in business growth intentions across the life course. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 36(3), 495–512. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6520.2012.00508.x.

De Bruin, A., Brush, C. G., & Welter, F. (2006). Introduction to the special issue: towards building cumulative knowledge on women’s entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 30(5), 585–593. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6520.2006.00137.x.

Delmar, F., & Wiklund, J. (2008). The effect of small business managers’ growth motivation on firm growth: a longitudinal study. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 32(3), 437–457. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6520.2008.00235.x.

Di Gregorio, D., Musteen, M., & Thomas, D. E. (2008). International new ventures: the cross-border nexus of individuals and opportunities. Journal of World Business, 43(2), 186–196. doi:10.1016/j.jwb.2007.11.013.

Du Rietz, A., & Henrekson, M. (2000). Testing the female underperformance hypothesis. Small Business Economics, 14(1), 1–10. doi:10.1023/A:1008106215480.

ECB (2012). ECB monthly bulletin May 2012. Frankfurt: European Central Bank.

Eckel, C. C., & Grossman, P. J. (2008). Differences in the economic decisions of men and women: experimental evidence. In C. Plott & V. Smith (Eds.), Handbook of experimental economics results (pp. 509–519). New York: Elsevier.

Estrin, S., Korosteleva, J., & Mickiewicz, T. (2013). Which institutions encourage entrepreneurial growth aspirations? Journal of Business Venturing, 28(4), 564–580. doi:10.1016/j.jbusvent.2012.05.001.

European Commission (2012). European economic forecast, Autumn/2012. Brussels: European Commission. doi: 10.2765/19623

Fritsch, M. & Schroeter, A. (2009). Are more start-ups really better? Quantity and quality of new businesses and their effect on regional development. Jena Economic Research Papers, No. 2009–070.

Fritsch, M. & Schroeter, A. (2010). Does quality make a difference? Employment effects of high-and low-quality start-ups. Jena Economic Research Papers, No. 2011–001.

Gundry, L. K., & Welsch, H. P. (2001). The ambitious entrepreneur: high growth strategies of women-owned enterprises. Journal of Business Venturing, 16(5), 453–470. doi:10.1016/S0883-9026(99)00059-2.

Gupta, V. K., Turban, D. B., Wasti, S. A., & Sikdar, A. (2009). The role of gender stereotypes in perceptions of entrepreneurs and intentions to become an entrepreneur. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 33(2), 397–417. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6520.2009.00296.x.

Guzmán, J., & Santos, F. J. (2001). The booster function and the entrepreneurial quality: an application to the province of Seville. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 13(3), 211–228. doi:10.1080/08985620110035651.

Harper, D. (1998). Institutional conditions for entrepreneurship. Advances in Austrian Economics, 5, 241–275.

Haus, I., Steinmetz, H., Isidor, R., & Kabst, R. (2013). Gender effects on entrepreneurial intention: a meta-analytical structural equation model. International Journal of Gender and Entrepreneurship, 5(2), 130–156. doi:10.1108/17566261311328828.

Hermans, J., Vanderstraeten, J., Van Witteloostuijn, A., Dejardin, M., Ramdani, D., & Stam, E. (2015). Ambitious entrepreneurship: a review of growth aspirations, intentions, and expectations. Entrepreneurial Growth: Individual, Firm, and Region, 127–160. doi:10.1108/S1074-754020150000017011.

Henrekson, M., & Johansson, D. (2010). Gazelles as job creators: a survey and interpretation of the evidence. Small Business Economics, 35(2), 227–244. doi:10.1007/s11187-009-9172-z.

Hessels, J., Van Gelderen, M., & Thurik, R. (2008). Drivers of entrepreneurial aspirations at the country level: the role of start-up motivations and social security. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 4(4), 401–417. doi:10.1007/s11365-008-0083-2.

Hisrich, R. D., & Brush, C. (1984). The woman entrepreneur: management skills and business problems. Journal of Small Business Management, 22(1), 30–37.

Jianakoplos, N. A., & Bernasek, A. (1998). Are women more risk averse? Economic Inquiry, 36(4), 620–630. doi:10.1111/j.1465-7295.1998.tb01740.x.

Kirzner, I. M. (1979). Perception, opportunity, and profit. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Kirzner, I. M. (1973). Competition and entrepreneurship. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Klapper, L., & Love, I. (2011). The impact of the financial crisis on new firm registration. Economics Letters, 113(1), 1–4. doi:10.1016/j.econlet.2011.05.048.

Koellinger, P. (2008). Why are some entrepreneurs more innovative than others? Small Business Economics, 31(1), 21–37. doi:10.1007/s11187-008-9107-0.

Koellinger, P., Minniti, M., & Schade, C. (2007). “I think I can, I think I can”: overconfidence and entrepreneurial behavior. Journal of Economic Psychology, 28(4), 502–527. doi:10.1016/j.joep.2006.11.002.

Koellinger, P., & Thurik, A. R. (2012). Entrepreneurship and the business cycle. Review of Economics and Statistics, 94(4), 1143–1156. doi:10.1162/REST_a_00224.

Kolvereid, L. (1996). Organizational employment versus self-employment: reasons for career choice intentions. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 20(3), 23–31.

Kolvereid, L., & Bullvag, E. (1996). Growth intentions and actual growth: the impact of entrepreneurial choice. Journal of Enterprising Culture, 4(01), 1–17. doi:10.1142/S0218495896000022.

Kontolaimou, A., Giotopoulos, I., & Tsakanikas, A. (2016). A typology of European countries based on innovation efficiency and technology gaps: the role of early-stage entrepreneurship. Economic Modelling, 52(Part B), 477–484. doi:10.1016/j.econmod.2015.09.028.

Landini, F., Arrighetti, A., Caricati, L. & Monacelli, N. (2015). Entrepreneurial intention in the time of crisis: a field study. Paper presented at DRUID 2015 conference. Retrieved from http://druid8.sit.aau.dk/acc_papers/atvupj667jmnnagsl2aiodmc01ss.pdf

Leibenstein, H. (1968). Entrepreneurship and development. The American Economic Review, 58(2), 72–83.

Lerner, J. (2010). Innovation, entrepreneurship and financial market cycles. OECD Science, Technology and Industry Working Papers 2010/03: OECD Publishing. doi: 10.1787/18151965

Lerner, M., & Almor, T. (2002). Relationships among strategic capabilities and the performance of women-owned small ventures. Journal of Small Business Management, 40(2), 109–125. doi:10.1111/1540-627X.00044.

Levie, J., & Autio, E. (2011). Regulatory burden, rule of law, and entry of strategic entrepreneurs: an international panel study. Journal of Management Studies, 48(6), 1392–1419. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6486.2010.01006.x.

Levie, J., & Autio, E. (2008). A theoretical grounding and test of the GEM model. Small Business Economics, 31(3), 235–263. doi:10.1007/s11187-008-9136-8.

Manolova, T., Brush, C., Edelman, L., & Greene, P. (2002). Internationalization of small firms: personal factors revisited. International Small Business Journal, 20(1), 9–32. doi:10.1177/0266242602201003.

Marlow, S., & Patton, D. (2005). All credit to men? Entrepreneurship, finance, and gender. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 29(6), 717–735. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6520.2005.00105.x.

Mathews, J. A., & Zander, I. (2007). The international entrepreneurial dynamics of accelerated internationalisation. Journal of International Business Studies, 38(3), 387–403. doi:10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8400271.

Minniti, M., & Nardone, C. (2007). Being in someone else’s shoes: the role of gender in nascent entrepreneurship. Small Business Economics, 28(2–3), 223–238. doi:10.1007/s11187-006-9017-y.

Moini, A. (1995). An inquiry into successful exporting: an empirical investigation using a three-stage model. Journal of Small Business Management, 33(3), 9–25.

OECD (2012). Financing SMEs and entrepreneurs 2012: an OECD scoreboard. Paris: OECD Publishing. doi:10.1787/23065265.

OECD (2009). The impact of the global crisis on SME and entrepreneurship financing and policy responses. Paris: OECD Publishing.

Orhan, M. (2001). Women business owners in France: the issue of financing discrimination. Journal of Small Business Management, 39(1), 95–102. doi:10.1111/0447-2778.00009.

Orser, B., Spence, M., Riding, A., & Carrington, C. A. (2010). Gender and export propensity. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 34(5), 933–957. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6520.2009.00347.x.

Paul, S., & Sarma, V. (2013). Economic crisis and female entrepreneurship: evidence from countries in Eastern Europe and Central Asia (No. 13/08). CREDIT Research Paper.

Pines, A. M., Lerner, M., & Schwartz, D. (2010). Gender differences in entrepreneurship: equality, diversity and inclusion in times of global crisis. Equality, diversity and inclusion: An International journal, 29(2), 186–198. doi:10.1108/02610151011024493.

Reynolds, P., Bosma, N., Autio, E., Hunt, S., De Bono, N., Servais, I., & Chin, N. (2005). Global entrepreneurship monitor: data collection design and implementation 1998–2003. Small Business Economics, 24(3), 205–231. doi:10.1007/s11187-005-1980-1.

Reynolds, P. D., Bygrave, W. D., Autio, E., Cox, L., & Hay, M. (2002). Global entrepreneurship monitor: 2002 executive report. Kansas City, MO: Kauffman Center for Entrepreneurial Leadership.

Riding, A. L., & Swift, C. S. (1990). Women business owners and terms of credit: some empirical findings of the Canadian experience. Journal of Business Venturing, 5(5), 327–340. doi:10.1016/0883-9026(90)90009-I.

Rosa, P., & Hamilton, D. (1994). Gender and ownership in UK small firms. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 18(3), 11–11.

Ruzzier, M., Antonci, C., Hisrich, R. D., & Konecnik, M. (2007). Human capital and SME internationalization: a structural equation modeling study. Canadian Journal of Administrative Sciences/Revue Canadienne des Sciences de l’Administration, 24(1), 15–29. doi:10.1002/cjas.3.

Sapienza, H. J., & Grimm, C. M. (1997). Founder characteristics, start-up process, and strategy/structure variables as predictors of shortline railroad performance. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 22(1), 5–24.

Shane, S. (2009). Why encouraging more people to become entrepreneurs is bad public policy. Small Business Economics, 33(2), 141–149. doi:10.1007/s11187-009-9215-5.

Shane, S. (2000). Prior knowledge and the discovery of entrepreneurial opportunities. Organization Science, 11(4), 448–469. doi:10.1287/orsc.11.4.448.14602.

Shane, S., Kolvereid, L., & Westhead, P. (1991). An exploratory examination of the reasons leading to new firm formation across country and gender. Journal of Business Venturing, 6(6), 431–446. doi:10.1016/0883-9026(91)90029-D.

Shane, S., & Venkataraman, S. (2000). The promise of entrepreneurship as a field of research. Academy of Management Review, 25(1), 217–226. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-48543-8_8.

Stam, E., Bosma, N. & Van Witteloostuijn, A. (2012). Ambitious entrepreneurship: a review of the state of the art. Flemish Council for Science and Innovation.

Stam, E., Hartog, C., Van Stel, A., & Thurik, R. (2011). Ambitious Entrepreneurship and Macro-Economic growth. In M. Minniti (Ed.), The Dynamics of Entrepreneurship. Evidence from the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor Data (pp. 231–249). Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199580866.001.0001.

Stam, E., Suddle, K., Hessels, J. & Van Stel, A. (2009). High-growth entrepreneurs, public policies, and economic growth. In: Public policies for fostering entrepreneurship (pp. 91–110). Springer US.

Stefani, M.L. & Vacca, V.P. (2013). Credit access for female firms: evidence from a survey on European SMEs. Bank of Italy Occasional Paper No. 176.

Thurik, A. R., Carree, M. A., Van Stel, A., & Audretsch, D. B. (2008). Does self-employment reduce unemployment? Journal of Business Venturing, 23(6), 673–686. doi:10.1016/j.jbusvent.2008.01.007.

Valliere, D., & Peterson, R. (2009). Entrepreneurship and economic growth: evidence from emerging and developed countries. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 21(5–6), 459–480.

Van Gelderen, M. W., & Jansen, P. G. W. (2006). Autonomy as a startup motive. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 13(1), 23–32. doi:10.1108/14626000610645289.

Van Gelderen, M., Thurik, R., & Bosma, N. (2005). Success and risk factors in the pre-startup phase. Small Business Economics, 24(4), 365–380. doi:10.1007/s11187-004-6837-5.

Van Stel, A., Carree, M., & Thurik, R. (2005). The effect of entrepreneurial activity on national economic growth. Small Business Economics, 24(3), 311–321. doi:10.1007/s11187-005-1996-6.

Verheul, I., & Van Mil, L. (2011). What determines the growth ambition of Dutch early-stage entrepreneurs? International Journal of Entrepreneurial Venturing, 3(2), 183–207. doi:10.1504/IJEV.2011.039340.

Vivarelli, M., & Audretsch, D. (1998). The link between the entry decision and post-entry performance: evidence from Italy. Industrial and Corporate Change, 7(3), 485–500. doi:10.1093/icc/7.3.485.

Welter, F., Smallbone, D., & Isakova, N. (2006). Enterprising women in transition economies. Aldershot: Ashgate Publishing.

Wennekers, S., Van Stel, A., Thurik, R., & Reynolds, P. (2005). Nascent entrepreneurship and the level of economic development. Small Business Economics, 24(3), 293–309. doi:10.1007/s11187-005-1994-8.

Westhead, P., Ucbasaran, D., & Wright, M. (2003). Differences between private firms owned by novice, serial and portfolio entrepreneurs: implications for policy-makers and practitioners. Regional Studies, 37(2), 187–200. doi:10.1080/0034340022000057488.

Wiklund, J., & Shepherd, D. (2003). Aspiring for, and achieving growth: the moderating role of resources and opportunities. Journal of Management Studies, 40(8), 1919–1941. doi:10.1046/j.1467-6486.2003.00406.x.

Wong, P. K., Ho, Y. P., & Autio, E. (2005). Entrepreneurship, innovation and economic growth: evidence from GEM data. Small Business Economics, 24(3), 335–350. doi:10.1007/s11187-005-2000-1.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank two anonymous referees and the participants of the Technology Transfer Society (T2S) Annual Conference held at the University of Bergamo for their constructive comments and suggestions. We would also like to thank the Foundation for Economic and Industrial Research (IOBE), i.e. the Greek participating organization in GEM, for providing us the data for our work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Giotopoulos, I., Kontolaimou, A. & Tsakanikas, A. Drivers of high-quality entrepreneurship: what changes did the crisis bring about?. Small Bus Econ 48, 913–930 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-016-9814-x

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-016-9814-x