Abstract

The Global Entrepreneurship Monitor model combines insights on the allocation of effort into entrepreneurship at the national (adult working-age population) level with literature in the Austrian tradition. The model suggests that the relationship between national-level new business activity and the institutional environment, or Entrepreneurial Framework Conditions, is mediated by opportunity perception and the perception of start-up skills in the population. We provide a theory-grounded examination of this model and test the effect of one EFC, education and training for entrepreneurship, on the allocation of effort into new business activity. We find that in high-income countries, opportunity perception mediates fully the relationship between the level of post-secondary entrepreneurship education and training in a country and its rate of new business activity, including high-growth expectation new business activity. The mediating effect of skills perception is weaker. This result accords with the Kirznerian concept of alertness to opportunity stimulating action.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM) model, first published in Reynolds et al. (1999), proposes relationships between established and new business activity and economic growth at the national level. It also proposes antecedents of these two forms of business activity. The GEM model is influential because it affects how data are collected and analysed by the GEM consortium. To date, the relationships between the variables in the model have lacked explicit theoretical grounding. Because of this, the potential value of the GEM model for academic research remains unfulfilled, and it has been difficult to assess the value of empirical contributions based on GEM data. In this article, we relate the GEM model to influential theoretical frameworks in entrepreneurship. By discussing the GEM model in the light of received theory, we make it easier to assess the empirical contributions derived using the GEM model.Footnote 1 We also test one set of relationships embedded in the GEM model, that is, the relationships among national levels of entrepreneurship education and training, opportunity and skills perception in national populations, and types of national-level entrepreneurial activity.

The GEM model maintains that established business activity at the national level varies with General National Framework Conditions (GNFCs), while new, or entrepreneurial, business activity varies with national levels of Entrepreneurial Opportunity and Entrepreneurial Capacity. These, in turn, vary with Entrepreneurial Framework Conditions (EFCs) (Reynolds et al. 2005). The GEM model is a multi-level model, in that EFCs are described at the national level, while entrepreneurial opportunity, capacity and activity are measured at the individual level and aggregated to the national level. Thus, the model implies that entrepreneurial activity at the individual and national levels may respond to a different set of environmental parameters than established business activity. The GEM model does not seek to associate individual-level characteristics to individual-level entrepreneurial behaviors, but rather, it focuses on structural conditions that regulate the allocation of effort into entrepreneurship at the population level. The model also implies that, controlling for GNFCs, governments that ensure superior EFCs should expect higher national rates of entrepreneurial activity—and higher rates of economic growth.

The GEM model assumes positive (if indirect) associations between EFCs and entrepreneurial activity. However, thus far, it has been unclear how these associations resonate with received theoretical frameworks in entrepreneurship, and the primary use of the model has been to guide data collection efforts. Previous explorations of the associations between EFCs and entrepreneurial activity have reported mainly negative bivariate correlations with early stage entrepreneurial activity (TEA) at the national level (Reynolds et al. 2002) and neutral or positive correlations with indicators of high-growth expectation entrepreneurial activity (HEA) (Autio 2005, 2007). More positive and significant bivariate associations have been found with measures of the relative prevalence of high-growth expectation entrepreneurial activity, that is, HEA as a proportion of TEA (Autio 2005, 2007). However, these cross-sectional data and bivariate correlation analyses have not provided rigorous tests of the association between EFCs and entrepreneurial activity.

In this article, we test one set of relationships embedded in the GEM conceptual model, that is, the relationships between entrepreneurship education and training, opportunity and capacity perception, and types of national-level entrepreneurial activity. Although EFC data based on national expert surveys has been collected each year since GEM started, empirical studies of the relationships between EFCs and types of entrepreneurial activity remain surprisingly rare. Furthermore, the few studies in existence have applied cross-sectional designs and have been the subject of obvious consequent limitations. Prompted by recent suggestions that high-growth expectation entrepreneurial activity may respond to EFCs differently from early stage entrepreneurial activity as a whole (Autio 2005, 2007), we compare associations between EFCs and both TEA and HEA. Aware of the complex relationship between the wealth of nations and new business activity rates (Minniti et al. 2006; Acs et al. 2008a), we also test these relationships in a sample of high income nations.

We seek to make two important contributions in this paper. First, we build theory to lay out the relationships between EFCs and types of entrepreneurial activity, hence contributing to a firmer theoretical grounding of the GEM model. Second, employing 7-year panel data on the links between EFCs and GEM indices of national-level entrepreneurial activity, we provide the most extensive test of relationships specified by the GEM model that has been implemented thus far. In the following sections, we first build our theoretical model. We then explain our method and discuss our empirical findings. We conclude by suggesting implications for theory and for further research.

2 Linking the GEM model to theories of entrepreneurship

2.1 The GEM model

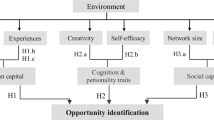

The GEM model was created by Paul Reynolds based on an idea by Michael Hay in 1997 for a World Enterprise Index that would be the equivalent for enterprise and entrepreneurship of IMD’s World Competitiveness Yearbook and the World Economic Forum’s Global Competitiveness Index. Reynolds wished to “provide something that complemented the Global Competitiveness Model, which was implied more than explicated in the reports produced by the World Economic Forum at the time. It was an alternative to thinking that only large established firms were important, reflecting, as it were, the central contribution of David Birch to understanding business dynamics” (P.D. Reynolds, personal communication, 2008). We reproduce the GEM model as shown in Acs et al. (2005) in Fig. 1.Footnote 2 As this model is rather complex, we reserve the use of italics to denote elements of the GEM model throughout this paper.

GEM conceptual model (taken from Acs et al. 2005, p. 14)

The GEM model describes two distinct business processes and proposes that they are associated with economic growth. The first process describes existing or routine business activity and its antecedents. We will not consider it further here, except to note that certain factors, extensively reported on by the World Economic Forum (WEF), are held to be directly associated with the level of general business activity (Lopez-Claros et al. 2006). The GEM model labels these factors General National Framework Conditions (GNFCs). GEM proposes an additional, complementary process in which individuals perceive opportunities and are thereby prompted to create new business activity, which in turn is proposed to impact economic growth. In so doing, the model follows theorists of entrepreneurship in the Austrian tradition, including Schumpeter (1934) and Kirzner (1997a), as well as other economists who have recognized the role of entrepreneurship in economic development, such as Leibenstein (1968), Baumol (2002) and Acs et al. (2004). GEM proposes that a second set of factors affects the level of new business activity, and these factors are termed Entrepreneurial Framework Conditions (EFCs).

On the left-hand side of the model, the backdrop to these two processes of creation of economic activity is what Leibenstein (1968) termed “socio-cultural and political constraints” (1968, p. 78). These constraints are labeled Social, Cultural, Political Context in the GEM model. They are underlying variables that would affect the way EFCs (and GNFCs) are constructed in a country. Examples might include national culture or universal values (Smith et al. 2002), relative wealth, which would affect the ability of a government to deliver EFCs,Footnote 3 and type of government (for example, centralized planning versus open economy). Others might include population growth (Hunt and Levie 2004; Levie and Hunt 2005), and the growth rate of the economy itself (Lundström and Stevenson 2005; Acs et al. 2005, p. 38; Acs and Amorós 2008).

We turn now to the right-hand side of the model, to the relationship between entrepreneurship and economic growth. Arguably the first economist to put the entrepreneur at centre stage of economic development was Schumpeter, who broke free from the prevailing comparative statics approach and recognized economies as self-transforming systems, with entrepreneurs as the agents of transformation (Schumpeter 1934; Witt 2002). To Schumpeter, entrepreneurs are innovators who open up profit-making opportunities by creating temporary monopolies through their organizational and technological innovations. They constantly disturb the status quo preferred by established incumbents, forcing these to react to emerging threats. This process of “creative destruction” (Schumpeter 1947a, p. 81) contributes to greater productivity, and hence, greater economic growth. This approach has been taken up and developed further by Leibenstein (1968), Baumol (2002) and others. Recently, Acs et al. (2004) have extended the new growth theory (Romer 1990) by assigning an explicit role for the Schumpeterian entrepreneur as the converter of knowledge into economic knowledge, and thus, as a significant contributor to economic growth (see also Audretsch et al. 2006).

Schumpeter’s entrepreneur disturbed economic equilibria through the act of innovating. An alternative perspective on entrepreneurship and economic growth was provided by subsequent Austrian economists, such as von Mises (1949), Hayek (1945, 1978) and Kirzner (1997b), who emphasized the role of entrepreneurs as discoverers of arbitrage opportunities in the market. Alert entrepreneurs stumble upon market disequilibria, as manifested in, for example, under-valued resources or unmet needs. This discovery gives rise to an equilibration process, as entrepreneurs seek to exploit their discoveries for economic benefit and thus generate economic growth. Rather than tending away from economic equilibrium, as in Schumpeter’s model, this depiction portrays entrepreneurs as tending towards equilibrium (Baumol 2003). This perspective treats entrepreneurship essentially as a market process and considers entrepreneurship to be an essential aspect of the human condition. Entrepreneurship is considered as human action “seen from the aspect of the uncertainty inherent in every action” (Mises 1949, p. 254), and “In any real and living economy every actor is always an entrepreneur” (Mises 1949, p. 253, cf Kirzner 1997b, p. 69). In this view, the essential question for entrepreneurship research is not who entrepreneurs are, but rather, what do they do, under which conditions, and with what consequences (Murphy et al. 1991; Baumol 1990; Shane and Venkataraman 2000).

Several writers have suggested that the Schumpeterian and Kirznerian views are complementary rather than contradictory (Baumol 2003; Shane 2003) and that both Schumpeterian and Kirznerian entrepreneurs contribute to economic growth. The GEM model accommodates this viewFootnote 4 and includes both innovative, Schumpeterian entrepreneurs, and replicative arbitrageurs that make up the bulk of Kirznerian entrepreneurs. The typical Schumpeterian entrepreneur is rare and has a small chance of having a high impact on economic growth, while the Kirznerian entrepreneur is more common and has a better chance of having a low impact on economic growth. Given the greater quantity of Kirznerian entrepreneurs, however, their combined effect may be considerable, and they should not be ignored.

While the Austrian tradition has helped pinpoint essential conditions that give rise to entrepreneurship (i.e., innovation and discovery), its focus on the consequences of the entrepreneurial process has meant that it has not considered structural contingencies that might impact the allocation of effort to entrepreneurship. Helpful contributions in this regard have been made by Baumol (1990, 2003), and in parallel, Murphy et al. (1991), who focused explicitly on such contingencies. Baumol distinguished between productive, unproductive and destructive entrepreneurship and proposed that the form of entrepreneurship an entrepreneur chooses is governed by the prevailing ‘rules of the game’, or the reward structure in the economy (Baumol 1990). He recognized two conditions in particular as central to the process of allocation of effort into productive entrepreneurship: the degree to which the rule of law is respected in the country and the degree to which laws support the appropriation of returns from entrepreneurial efforts.

Murphy et al. proposed a similar approach to Baumol, but focused on talent, arguing that: “A country’s most talented people typically organize production by others, so they can spread their ability advantage over a larger scale. When they start firms, they innovate and foster growth, but when they become rent seekers, they only redistribute wealth and reduce growth” (1991, p. 503). Murphy et al.’s analysis suggests that Baumol’s general argument should apply also to highly talented individuals, who might be expected to engage in high potential entrepreneurship, assuming the opportunity costs are favorable.

We propose that it is helpful to think of the GEM model as an Austrian model of the ‘Baumolian’ allocation of effort into productive entrepreneurship.Footnote 5 This approach is reflected in GEM’s main indicator of new business activity, the TEA index. The TEA index provides a measure of ‘Baumolian’ allocation of effort to entrepreneurship within a given population. This allocation is regulated by perception of opportunity within that population in the Austrian sense of that term. GEM’s main contribution to the Baumolian analysis is a detailed consideration of ‘Entrepreneurial Framework Conditions’ (EFCs), or exogenous structural conditions that regulate the perception of opportunity and the availability of entrepreneurial skills in the population. To provide insight into the relationships between these structural conditions and entrepreneurial activity, we turn to Harvey Leibenstein (1966, 1968, 1978, 1987, 1995), who has written extensively on this topic.

Like Schumpeter, Leibenstein (1968) recognized two broad types of business activity as contributing to economic growth: routine entrepreneurship or management, that is “the activities involved in coordinating and carrying on a well-established, going concern”, and “new-type” or “N-entrepreneurship”,Footnote 6 that is “the activities necessary to create or carry on an enterprise where not all the markets are well established or clearly defined and/or in which the relevant parts of the production function are not completely known” (Leibenstein 1968, pp. 73 and 79). This distinction is also made in the GEM model. Established firm activity, represented by Major, Established Firms and Micro, Small and Medium Firms—the top row of the GEM model—is distinct from new entrepreneurial activity or New Firms—the bottom row of the model. Leibenstein linked the two activities to economic growth by suggesting that: “…growth would depend, in part, on the degree of routine entrepreneurship, the degree to which gaps and impediments in markets exist, and the quality, motivations, and opportunity costs of the potential gap-fillers and input-completers available” (1968, p. 79).

This description mirrors the positioning of the GEM model variables of Entrepreneurial Opportunities, the “gaps and impediments in markets” (1968, p. 79) as the demand side of new firm creation and Entrepreneurial Capacity or “the capacity to assess such opportunities” (1968, p. 80) on the supply side. Leibenstein distinguished between the ‘objective’ “maximal productive possibilities set” (1968, p. 78) and the smaller ‘subjective’ set of opportunities that entrepreneurs perceive to exist. Kirzner (1979, p. 117), too, recognized that, “in principle”, opportunities might be available without the entrepreneur. Shane and Venkataraman (2000) and Shane (2003) also take the view that opportunities exist independently of the observer, though they need human intervention to bring them to life. However, other theorists have questioned the objective existence of opportunities (see, for example, Gartner et al. 1992). Entrepreneurial Opportunities in the first iteration of the GEM model (Reynolds et al. 1999, p. 11) explicitly included both “existence” and “perception” of opportunities under this heading. This raises issues of operationalizing existence of opportunities when, as Hayek, Kirzner and others have pointed out, information is widely distributed and not available to any one individual. We show in the methods section one way of dealing with this issue. Interestingly, Leibenstein saw perception of opportunity as an element of entrepreneurial capacity, based on skill and knowledge: “[only] those individuals who have the necessary skills to perceive entrepreneurial opportunities, to carry out the required input gap-filling activities, and to be input-completers can be entrepreneurs” (1978, p. 50).

In summary, the GEM model suggests that new business activity takes place when those who believe they have the skills, knowledge and motivation to start a business perceive an opportunity to do so. Technical business start-up skills alone are not enough—an individual must perceive an opportunity before action can be taken.

In the GEM model, Entrepreneurial Capacity contains two of Leibenstein’s three supply-side factors: “the set of individuals with gap-filling and input-completing capacities” (1968, p. 78)—summarized as Skills in the GEM model, and “the degree to which potential entrepreneurs respond to different motivational states, especially where non-traditional activities are involved” (1968, pp. 78–79), summarized as Motivation in the GEM model. As Leibenstein put it in a later paper: “What is necessary for the entrepreneur is a commitment to overcome difficulties whatever they may be in order to fully take advantage of an opportunity. Thus, motivation is a necessary element of entrepreneurship” (1987, p. 197).Footnote 7

According to Leibenstein, “perception of economic opportunities and the capacity to assess such opportunities … are presumably determined in part by factors exogenous to the system such as those involved in nurture, informal training, experience, as well as formal education of individuals” (1968, p. 80). In an alternative but complementary conceptualisation, Acs et al. (2004) have proposed that economies have a “filter” that impedes the conversion of knowledge into economic knowledge, and the thickness of that filter, its mesh size, as it were, is a result of policy, traditions and path-dependence. In the GEM model, those exogenous factors that affect business activity generally, such as formal education, are labeled General National Framework Conditions, while those that are specific to the context of entrepreneurial activity, such as entrepreneurship training, are labeled Entrepreneurial Framework Conditions (EFCs).

2.2 Entrepreneurial framework conditions

Through the EFCs, the GEM model maps the specific conditions in which productive entrepreneurship, in the Baumolian (1990) sense, can flourish.Footnote 8 One could see EFCs as defining the rules of the game for entrepreneurial activity in any given context: change the EFCs, and the rate and nature of (productive) entrepreneurial activity may change. Leibenstein set out the policy prospects for altering EFCs as follows:

While entrepreneurship may be scarce because of a lack of input completing capacities, some entrepreneurial characteristics may in fact be in surplus supply … unused simply because of the lack of the input completing capacity. … it is possible that in some cases, small changes in the motivational state or in the reduction of market impediments may turn entrepreneurial scarcity into an abundant supply. (1968, p. 82)

In the following subsections, we consider each EFC in the GEM model and its possible effects on entrepreneurial activity, including examples of empirical findings to date.

2.2.1 Finance

Finance is arguably the most widely recognized regulator of allocation of effort to entrepreneurship. As a rule, some up-front investment is required to establish a new production function in the economy, creating an obvious need for financial investment in the expectation of subsequent returns. Finance was the only external regulator explicitly recognized by Schumpeter, who focused on the availability of bank credit, although he also mentioned private equity providers. It was clear to Schumpeter that entrepreneurship was more dependent than routine business activities on credit to fund access to resources: “credit is primarily necessary to new combinations” (Schumpeter 1934, p. 70).

Leibenstein was well aware that capital was important to entrepreneurs, and that access to finance would vary by country. He observed that the sophistication of credit and lending systems varied across countries and that entrepreneurs sometimes had to employ political strategies to get access to this vital resource: “In some countries the capacity to obtain finance may depend on family connections rather than on the willingness to pay a certain interest rate. A successful entrepreneur may, at times, have to have the capacity to operate well in the political arena connected with his economic activities” (1968, pp. 73–74).

Access to finance is also the most widely recognized object of entrepreneurship policy, and insufficient finance is regularly cited by non-entrepreneurs as a barrier to starting a business (Volery et al. 1997; Kouriloff 2000; Robertson et al. 2003; Choo and Wong 2006). There is some evidence that restricted competition in banking and government credit controls can restrict entry in the non-financial sector (Cetorelli and Strahan 2006; Kawai and Urata 2002). In this regard, Leibenstein suggested that the return on an N-entrepreneurial investment had different qualities from an investment in routine entrepreneurship, and this had implications for policy and for the financial industry (1968, p. 82).

It is clear then that the supply of finance for entrepreneurship should be considered in any model of structural conditions for entrepreneurship.

2.2.2 Government policy

Government policy is recognized as an explicit regulator of entrepreneurship in the GEM model. The inclusion of this EFC in the model reflects the broad policy interest toward entrepreneurship and the associated shift in emphasis from generic ‘industrial policy’ toward specific ‘SME’ and ‘innovation’ policies from the mid-1980s onwards (Storey 1994; Storey and Tether 1998). As such, however, the very existence of a distinctive ‘entrepreneurship policy’ remains a subject of ongoing debate. Some contend that entrepreneurship is too broad-based a phenomenon to be bracketed into a dedicated policy box (Acs and Szerb 2007), while others make a case for exactly such bracketing (Hart 2003; Lundström and Stevenson 2005). Whether such bracketing is possible or not, there appears to be a general consensus that entrepreneurship is a phenomenon that can, at the national and regional levels, be addressed by policy-makers, and that increased awareness and attention by policy-makers should be positively associated with the allocation of effort into entrepreneurship (Audretsch et al. 2007a, b). This view was shared by Leibenstein (1968, p. 83), who recommended focusing on: “…the gaps, obstructions, and impediments in the market network of the economy in question and on the gap-filling and input-completing capacities and responsiveness to different motivational states of the potential entrepreneurs in the population.” Policy, thus, should focus on enhancing the efficiency of the market, as well as on providing an environment that is responsive to motivated entrepreneurs.

Theoretical work emanating from the GEM research has emphasized the need of policy to be responsive not only to the needs and motivational states of entrepreneurs, but also to the general economic development in the country (Acs et al. 2005; van Stel et al. 2005; Wennekers et al. 2005). This body of work suggests that, for different economies, the optimal levels of entrepreneurial activity may vary, and entrepreneurship, in general, may have different gap-filling functions in different stages of economic development. Because of such complexities, GEM’s operationalization of the government policy EFC does not measure specific policies, but rather focuses on the general prioritisation of entrepreneurship in government economic policy. Although this approach does not provide a clear policy prescription for Government, it does suggest that Government should take the need to facilitate entrepreneurs into account when designing and implementing policy. This sentiment is echoed by many supra-national organisations such as the OECD (Cotis 2007) and the EU (Directorate-General Enterprise 2004). Other writers in the Austrian tradition have tended to focus on one aspect of government policy: regulations.

2.2.3 Government regulations

Governments can directly affect entrepreneurial firms through their regulatory controls. Kirzner (1985, 1997a) in particular has shown that from an Austrian perspective, restriction of entry and exit inhibits the market process, thereby damaging economic growth. Regulations constitute one of the most widely studied external conditions for business and entrepreneurial activity, and regulatory issues are cited regularly in studies of barriers to start-ups that are based on surveys of non-entrepreneurs (van Stel et al. 2007; Grilo and Irigoyen 2006). Some studies have found that regulations, taxes and labor market rigidities tend to load together in analyses of barriers to start-up (Volery et al. 1997; Choo and Wong 2006; Klapper et al. 2006; Acs et al. 2008b).

Empirical studies suggest two ways in which regulations impact on the entrepreneurial process. First, cumbersome regulations and delays in obtaining the necessary permits and licenses may increase the duration of the start-up process (Klapper et al. 2006). This can reduce new business entry because the window of opportunity may have passed by the time all regulations are complied with. Regulations also enable officials to micro-manage industries by obstructing or delaying entry, either for personal or policy reasons (Maddy 2000, 2004). Dreher and Gassebner (2007), for example, reported a negative relationship between the number of licenses and permits required for entry and new firm formation rates. Similarly, Van der Horst et al. (2000) found that regulatory policies on licensing influenced entrepreneurs’ decisions to start business ventures.

Second, unpredictable and strenuous application of regulations pushes up compliance costs, thereby increasing the cost of start-up and negatively impacting profitability and the firms’ ability to use their retained earnings to fuel growth. In this sense, regulations represent the tangible application of government policy, as felt in the immediate operating environment of entrepreneurial firms. A particularly important component of control is taxation, and there is evidence that correctly applied tax policies may provide incentives for innovation and growth of firms (Keuschnigg and Nielsen 2002, 2004; Goldfarb and Henrekson 2003; Puffer and McCarthy 2001). More commonly reported findings focus on a negative relationship, as taxes impose a direct financial cost on firms, affecting their profitability and growth (Baumol 1990; Davidsson and Henrekson 2002; Van der Horst et al. 2000).

2.2.4 Government programs

In his discussion of exogenous factors, Leibenstein (1968, p. 80) recognized the role of “nurture” in building entrepreneurial capacity. Nurturing could be conducted by government agents through dedicated nurturing programs, or professional services advisors, such as accountants, bankers, lawyers and business consultants (Fischer and Reuber 2003; Clarysse and Bruneel 2007). Through dedicated support programs, governments can facilitate the operation of entrepreneurial firms by addressing gaps in their resource and competence needs—either on a subsidized basis or by correcting the failure of the market to cater to such needs. Governments may support entrepreneurial firms through programs which provide subsidies, material and informational support for new ventures (Dahles 2005; Keuschnigg and Nielsen 2001, 2002, 2004). Such programs may reduce transaction costs for the firms (Shane 2002) and enhance the human capital of entrepreneurs (Fayolle 2000; Delmar and Shane 2003).

2.2.5 Education and training

Education and training for entrepreneurship have been one of the most widely studied and used means to encourage entrepreneurial activity. Entrepreneurship-specific training and education are expected to enhance the supply of entrepreneurship through three distinct mechanisms: First, through the provision of instrumental skills required to start up and grow a new firm (Honig 2004); second, through the enhanced cognitive ability of individuals to manage the complexities involved in opportunity recognition and assessment, as well as in the creation and growth of new organizations (DeTienne and Chandler 2004); and third, through the cultural effect on students’ attitudes and behavioral dispositions (Peterman and Kennedy 2003). Liebenstein emphasized the instrumental aspect of education, noting that: “… training can do something to increase the supply of entrepreneurship. …since entrepreneurship requires a combination of capacities, some of which may be vital gaps in carrying out the input-completing aspect of the entrepreneurial role, training can eliminate some of these gaps.” (1968, p. 82)

Entrepreneurship education and training as an exogenous factor are different from general education, which is included in several GNFCs. The effect of entrepreneurship education and training will be discussed more in detail in the next section, where we develop six hypotheses on the effect of entrepreneurship education and training on the supply of entrepreneurship.

2.2.6 R&D transfer

While Kirzner (1997) saw market opportunities as an originator of entrepreneurial action, Schumpeter (1934) emphasized the important role of technological development as a driving force behind entrepreneurial opportunities. This argument has been developed further in the ‘knowledge spill-over theory of entrepreneurship’ (Acs 2006; Acs et al. 2005; Acs et al. 2004), which represents an extension of, as well as a merger of, the ‘Romerian’ and ‘Schumpeterian’ models of economic growth. The knowledge spill-over theory argues that knowledge by itself is a necessary, but not sufficient, condition for economic growth. Not all inventions are automatically converted into innovations, and not all advances in research knowledge end up giving rise to commercialized, economically useful knowledge.

New knowledge is predominantly created in research institutions and in large firms. To contribute to the economy, research knowledge needs to be converted into economically useful knowledge, and inventions need to be converted into innovations. Acs et al. (2006) suggest that this conversion process can occur either through established incumbents (in which case the process will be regulated by their absorptive capacity) or through innovative entrepreneurial firms. According to their theory:

entrepreneurship becomes central to generating economic growth by serving as a conduit, albeit not the sole conduit, by which knowledge created by incumbent organizations spills over to agents who endogenously create a new organization. (Acs et al. 2006, p. 12)

Entrepreneurship plays an important role in facilitating the exploitation of knowledge spillovers, because new knowledge is characterized by greater uncertainty and asymmetry than other economic goods. Entrepreneurial alertness and discovery are therefore required to uncover valuable new knowledge and harness knowledge slack created by unused knowledge advances generated by incumbents (Acs and Varga 2005). Consistent with this theory, the GEM model proposes that countries in which transfer of knowledge generated by R&D from laboratories to entrepreneurs is relatively quick and cheap should generate more innovative new businesses than those in which this process is costly or slow.

2.2.7 Commercial and legal infrastructure

Commercial and Legal Infrastructure comprises business services that are necessary for the management of entrepreneurial firms. Such services include availability of subcontractors, suppliers, consultants and legal, accounting, advertising, financial and banking services. Professional or business services are helpful throughout the entrepreneurial process, particularly in the management and operation of the firms (Suzuki et al. 2002). Good availability of business services permits entrepreneurial firms to focus on their core business, thereby achieving efficiency and specialization gains. Among the services needed during the firm formation process are legal services (Ruef 2005). Where there is lack of legal services, this could pose an obstacle to entrepreneurship (Brenner 1992). This may be particularly important for high potential firms, which may rapidly need to obtain limited liability status and negotiate often complex legal agreements with many stakeholders.

2.2.8 Internal market openness

Economists in the Austrian tradition recognize market dynamics and industry structure as a motivating factor in entrepreneurial activity (e.g., Leibenstein 1968, p. 79, 1987, p. 201; Kirzner 1997a, p. 47). Market and industry structure and firm entry have been widely studied in the industrial organization and entrepreneurship literature (Geroski 1989, 1995; Klepper 1996, 2002; Klepper and Sleeper 2005). Scholars have theorized both market and technology life cycle effects, predicting higher rates of new firm entry near the beginning of a market’s life cycle, as demand and supply increase rapidly, possibly facilitated by high levels of certain types of innovative and spin-off activity (Malerba and Orsenigo 1996; Acs and Audretsh 1990; Carree and Thurik 2000; Klepper 2002). In early stages, new firm entry provides an important driving factor of market dynamism, but market dynamism, in itself, also opens opportunities for entry by entrepreneurial ventures. There thus exists a two-way relationship between new firm entry and market dynamism. The exogenous factor of market structure is included in the GEM model as Internal Market Openness, which contains two parts, Market Dynamics, which focuses on the rapidity of market change, and Market Openness, which deals with ease of entry to a market.

2.2.9 Access to physical infrastructure

Physical infrastructure such as transportation, land or operating space, and communication facilities such as Internet, telephone and postal services are vital for the successful operation of entrepreneurial activities and venture start-up and growth (Trulsson 2002; Liao et al. 2001; Hansen and Sebora 2003). To set up a business, one usually needs access to physical infrastructure such as office and operating space, equipment and basic utilities.Footnote 9 The availability of such utilities will encourage the start-up of new ventures (Carter et al. 1996; Dubini 1989).

Accessing physical infrastructure can be seen as one of the inputs that the Leibensteinian entrepreneur must pull together in his or her role as economic “gap-filler” and an “input-completer.” As he put it (1968, p. 75): “If six inputs are needed to bring to fruition a firm that produces a marketable product, it does no good to be able to marshal easily five of them.” This factor may be even more important to high potential entrepreneurs than to lifestyle entrepreneurs who may be able to work from home. Access to physical infrastructure for entrepreneurs can vary widely from country to country. While it may be taken for granted in many high-income countries, in others it can be a major issue (see, e.g., Bitzenis and Nito 2005).

2.2.10 Social, cultural norms

Culture is a commonly cited determinant of entrepreneurial behavior (George and Zahra 2002). Here, it is important to distinguish between general national culture or universal values, such as measured by Hofstede (1980), Schwartz (1994), Inglehart (1997) and House (1998) and context-specific beliefs or attitudes towards entrepreneurship. A number of empirical studies have reported statistical associations of, e.g., Hofstede’s (1980) scales of culture and entrepreneurial activities (Hayton et al. 2002; Uhlaner and Thurik 2007; Hofstede et al. 2007), but the results of attempts to date to measure the effect of national culture on entrepreneurial activity using standard national culture measures and appropriate controls have been mixed (Spencer and Gomez 2004; Levie and Hunt 2005), reflecting recent findings on relationships between national cultural values and practices generally (Javidan et al. 2006). According to Smith et al. (2002, p. 204), “widely shared beliefs in given societies may mediate between cultural values and enactment of specific behaviors,” and this may explain these mixed findings. The GEM model distinguishes between national culture, labeled as Cultural Context, which is dealt with separately as a contextual factor, and Entrepreneurial Cultural and Social Norms, which cover context-specific beliefs about and attitudes towards entrepreneurship,Footnote 10 which is treated as an EFC.

Unlike universal values, context-specific beliefs about entrepreneurship and its legitimacy can change quite rapidly (Etzioni 1987). At the individual level, the social desirability of entrepreneurial behaviors influences individual entrepreneurial intentions (Ajzen 1991). Positive cultural dispositions toward self-initiative, independence, innovativeness and individual effort will likely impact the perception of desirability, and hence, allocation of effort into entrepreneurship. Negative attitudes towards entrepreneurship as a barrier to entrepreneurial activity have been studied in several countries, including Russia (Kaufmann et al. 1995) and Japan (Hawkins 1993; Helms 2003).

A related potential determinant of entrepreneurial motivations and actions is social legitimation (Etzioni 1987) or national respect for entrepreneurship. National respect for entrepreneurs, as evidenced by peoples’ attitudes toward those who have obtained personal wealth through entrepreneurial actions, as well as positive publicity and media on the topic, is likely to influence peoples’ perceptions of the social desirability of entrepreneurial actions, and hence, their entrepreneurial motivations and intent. There is some empirical support for this from the GEM adult population surveys (Reynolds et al. 2003, p. 45; Levie and Hunt 2005).

3 Education and training and allocation of effort into entrepreneurship

While education is one of the most widely discussed and studied themes in the entrepreneurship literature, population-level evidence concerning the influence of entrepreneurship training and education on entrepreneurial activity is still lacking (Béchard and Grégoire 2005). In this section we employ the GEM model to develop hypotheses on the effect of national-level entrepreneurship training and education on national-level entrepreneurial activity that are consistent with the literature on this topic. We propose that, consistent with the GEM model, entrepreneurship training and education impact national-level entrepreneurial activity through two main mechanisms.Footnote 11 One of these operates through its influence on the population’s ability to recognize and pursue entrepreneurial economic opportunities. As the second mechanism, we contend that entrepreneurship training also infuses individuals with the necessary technical skills and competencies required to launch new start-up firms.

3.1 Education, opportunity recognition and entrepreneurial activity

For nascent ventures, the entrepreneur’s human capital, as expressed in her education, experience and skills, constitutes arguably the most important initial resource endowment (Shrader and Siegel 2007; Wright et al. 2007). Education enhances an individual’s cognitive ability, thereby enabling her to better recognize an opportunity when one presents itself (DeTienne and Chandler 2004; Parker 2006). A key notion in mainstream entrepreneurship theories is that opportunities are discovered when the entrepreneur identifies a match between the world she observes and her unique skills, capabilities and social capital (Eckhardt and Shane 2003; Shane 2000). Rather than search, Austrians argue, entrepreneurs speculate, take risks and discover (Hayek 1945; Kirzner 1997). During this process, entrepreneurs constantly interact with customers and competing suppliers, thereby generating “…such facts as, without resort to [the competitive process] would not be known to anyone” (Hayek 1978, p. 179; cf. Kirzner 1998). This process of discovery places important demands on entrepreneurs’ cognitive abilities.

Shane and Venkataraman (2000, p. 222) maintain that individuals’ ability to recognize opportunities is dependent on: “(1) the possession of the prior information necessary to identify an opportunity and (2) the cognitive properties necessary to value it.” By prior information they mean experience-based understanding of user needs in a given domain. By cognitive properties they mean an individual’s ability to process information emanating from social interactions that take place in the market. Whether the entrepreneur will be able to see the opportunity in any given situation will depend on her ability to comprehend, analyze and make sense of the feedback received, as well as on her ability to translate this information into the economic language of supply and demand. Significant cognitive processing is required before serendipitous feedback emanating from social and economic interactions is converted into an action-enabling and action-guiding understanding of how to take advantage of a given situation, resource or gap discovered in the marketplace.

Entrepreneurship training and education enhances the cognitive abilities required for the discovery of market opportunities (DeTienne and Chandler 2004). Entrepreneurship training and education exposes individuals to stories and cases of the discovery and exploitation of entrepreneurial opportunities, thus providing students with examples that they can relate to when encountering market gaps and undervalued resources. Such examples endow students with an understanding of what is possible and what is feasible, making students both more alert to opportunities as well as more able to tangibly assess opportunities (Fiet 2000). The financial component of entrepreneurship training and education endows students with an ability to quickly assess the feasibility of opportunities encountered, enabling them to relate the opportunity to their own situation. Because of these cognitive effects, entrepreneurship training and education should enhance opportunity discovery.

Hypothesis 1

At the national level, the perception of opportunity is positively associated with the quality of entrepreneurship training and education in a country’s educational institutions.

Perception of opportunity is a key condition for entrepreneurial action (Corbett 2005; Shane and Venkataraman 2000). The situational character of the process of opportunity discovery further emphasizes the gate-keeping role of opportunity discovery for entrepreneurial action. This aspect is also widely recognized in the entrepreneurship literature (Ardichvili et al. 2003). Therefore, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 2

At the national level, the allocation of effort into entrepreneurship is positively associated with the perception of opportunity.

The above discussion implies a mediating relationship between entrepreneurship training and education, opportunity perception, and the allocation of effort into entrepreneurship. It is argued that entrepreneurship education exercises the strongest influence on the ability of individuals in a population to perceive opportunities and subsequently to act entrepreneurially. Therefore, we propose:

Hypothesis 3

At the national level, the influence of entrepreneurship training and education on allocation of effort into entrepreneurship is fully mediated by its influence on the perception of opportunity.

3.2 Education, skills and entrepreneurial activity

As Schumpeter (1947b) observed, an entrepreneur is distinguished from an inventor in that an entrepreneur gets things done. Getting things done requires a special, rather than a specialist, set of skills, one distinguished by its generalist and broad-based nature (Lazear 2004; Michelacci 2003). Entrepreneurs need to master not only their own technical specialization, but also a broad set of business management and leadership skills in order to access and mobilize the resources necessary for launching and growing the new venture. In other words, to successfully manage and orchestrate multiple domains of activity, entrepreneurs need to be ‘jacks of all trades,’ who combine both domain-specific as well as generic management skills (Lazear 2005). We argue, consistent with much of the literature on entrepreneurial pedagogy, that this broad-based skill set constitutes a distinctive aspect of the entrepreneurial process, and that the possession of entrepreneurial skills constitutes an important determinant of the allocation of effort into entrepreneurship (Boyd and Vozikis 1994). Summarizing, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 4

At the national level, the allocation of effort into entrepreneurship will be positively associated with the prevalence of entrepreneurial skills in the population.

This ‘jack of all trades’ skills profile required of entrepreneurs places important demands upon the education and training of potential new entrepreneurs (Heinonen and Poikkijoki 2006; Levie 2006). Most education programs, particularly at higher levels of education, tend to focus on a single technical domain or on a given specialist profession (Bertrand 1995). Researchers of entrepreneurship education and training often point out that highly specialized education programs are ill suited to provide the broad-based and practice-oriented training required to teach entrepreneurial skills (Aronsson 2004; DeTienne and Chandler 2004; Garavan and O’Cinneide 1994). Instead of teaching specialist technical skills, the training programs aimed at enhancing entrepreneurial potential need to be highly practice-oriented, address a broad set of management, leadership and organizing skills and emphasize discovery-driven and contingency approaches to business planning (Honig 2004; Levie 2006). While many of the generalist skills required are likely picked up during the normal course of career progression, we argue that, because of the distinctive aspects of the entrepreneurial skill-set, national-level provision of entrepreneurship training and education in educational institutions will enhance entrepreneurial skills in the population: The possession of this broad skill set will infuse individuals with an entrepreneurial self-efficacy that will prompt them to pursue entrepreneurial opportunities, once such have been discovered (Chen et al. 1998; Peterman and Kennedy 2003). Therefore, we propose:

Hypothesis 5

At the national level, the prevalence of entrepreneurial skills within the population will be positively associated with the provision of entrepreneurship training and education in educational institutions.

As in the case of opportunity perception, we expect a mediating relationship among entrepreneurship training and education, entrepreneurial skills, and the allocation of effort into entrepreneurship:

Hypothesis 6

At the national level, the influence of entrepreneurship training and education on the allocation of effort into entrepreneurship is mediated by its influence on the prevalence of entrepreneurial skills within the population.

4 Method

4.1 Dataset

To test the hypotheses, we employed 7 years of country-level panel data from the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM) research consortium’s database, covering the years 2000 to 2006. This panel consisted of annual country-level measures, computed as weighted national averages of responses to over 800,000 adult-population interviews and, in a separate survey, over 1,000 interviews with experts in specific aspects of the environment for entrepreneurship in the participating countries. The two surveys were carried out annually in each participating country. The data were grouped by year and country, and the dataset contained a total of 232 year-country observations in 54 countries. The number of panel observations per country varied from 1 to 7, the average being 4.7. Some observations were excluded in analyses due to missing values. The number of countries (groups) and country-years (observations) for each analysis is shown in Tables 1–4.Footnote 12

At least 2,000 random interviews (in most countries by telephone, but in some countries by door-to-door interviews based on sophisticated randomization procedures) were carried out for the adult population survey. All primary data from adult-population interviews were weighted based on relevant demographic variables so as to ensure that the data were as fully representative of a given country’s adult-age population as possible (for a detailed account of the GEM method, see Reynolds et al. 2005).

The national expert survey employed a lengthy questionnaire with multiple items per EFC, reproduced in Appendix 1, which enabled country experts to assess each of the EFCs detailed in Sect. 2. The selection of experts was carried out by GEM’s national teams. To ensure balance of perspectives, the national teams were instructed to select at least four experts deemed particularly knowledgeable in each of the nine EFCs. With at least four experts per EFC, this selection strategy was designed to produce at least 36 respondents per country each year. Of the four experts per EFC, at least one was required to be an active entrepreneur. The remaining three experts per EFC were selected from among entrepreneurship academics, government policy-makers and providers of public and private services to entrepreneurs, for example, venture capitalists. Once contacted with a detailed explanation of the project, virtually all national experts typically agreed to participate in the survey or interview.

The expert responses were combined into multi-item scales for each EFC. For example, the Finance EFC index was created from the experts' responses to items A01 to A06 in the table in Appendix 1 on a 5-point Likert scale (where “completely true” = 1 and “completely false” = 5). Factor analysis was used to check that all factor items loaded on a single scale and that no important cross-loadings existed for individual items. As a result, three of the original EFCs, Government Policies, Education and Training, and Market Openness, were found to have two separate components. These are described in the next sub-section. Factor loadings of individual scale items were used as weights when computing the resulting multi-item scale. Between 2000 and 2006, some EFC items were refined at each annual GEM planning meeting to enhance internal reliability of the multi-item scales, although almost all scales featured good reliability (Chronbach alpha) of 0.7 or greater throughout this period. The internal reliabilities (Cronbach alpha) of the multi-item scales employed in 2006 range from a low of 0.76 to a high of 0.94. Validity checks with proxies from secondary sources suggest good external validity for the scales employed. A detailed account of GEM’s expert survey method is provided in Reynolds et al. (2005).

4.2 Variables

GEM identifies three types of entrepreneurs. Nascent entrepreneurs are individuals who are in the process of trying to start a firm and have done something tangible during the 12 months preceding the interview to this end. The individual concerned would plan to become an active owner-manager of the start-up, which must not have paid salaries to anyone for more than 3 months. New (or early stage) entrepreneurs are owner-managers of entrepreneurial start-ups, as defined above, which have been in existence for more than 3 months, but less than 42 months. Established entrepreneurs are owner-managers of entrepreneurial firms that have been in existence for at least 42 months. In terms of the GEM model, nascent and new entrepreneurs engage in new business activity (at the bottom end of the model in Fig. 1), and established entrepreneurs engage in established business activity (top end of the model). Note that these individuals may be starting or running new businesses that are either independent or part-owned by an existing company; the defining condition is that they both manage and own, in whole or in part, the business. In this way, the entrepreneurial activity measures include “corporate entrepreneurs” with stakes in corporate ventures sponsored by established businesses. This inclusive approach is in line with both the Shumpeterian view of entrepreneurship (Schumpeter 1934, pp. 74–75) and that of Shane (2003, p. 224), although it goes beyond Baumol’s “independent innovator” (2002, p. 55).Footnote 13

We operationalized new business activity at the population level in three ways. Based on the pooled data of 808,000 GEM interviews, we computed the GEM Early Stage Entrepreneurial Activity (TEA) index, labeled as TEA in our regression results, for each country-year. The TEA index indicates the percentage of the adult working-age population (18–64 years old) in a country who are classified as either nascent or new entrepreneurs, as defined above.

Because TEA incorporates any type of entrepreneurial activity (including self-employment attempts), the activity captured by this index includes both low-growth expectation and high-growth expectation entrepreneurship. In the GEM data, nearly 50% of all start-up attempts do not expect to create any jobs within 5 years (Autio 2007). Only some 10% of all start-up attempts expect 20 or more jobs, and these start-up attempts are responsible for some 75% of the cohort’s expected total number of jobs. Because of the skewness of the growth expectation distribution, we computed two more dependent variables. The High-Growth Expectation TEA Index, HEA, indicates the percentage of the adult working-age (18–64 years old) population who are classified as either nascent or new entrepreneurs, and who expect to create 20 or more jobs within 5 years.Footnote 14 The HEA index captures the top 10% of the early stage entrepreneurial population by growth expectation (or ambition).

The relative incidence of HEA varies across countries (Autio 2007). The GEM 2007 Global Report on High-Growth Entrepreneurship suggests that in poorer countries in particular, early stage entrepreneurial activity may be dominated more by low-growth expectation start-up attempts than in high-income countries. For this reason we computed the relative HEA index rHEA, which indicates the ratio between HEA and TEA: (rHEA = HEA/TEA). rHEA thus provides an indication of the anatomy, rather than population-level prevalence (or volume), of high-growth expectation entrepreneurship.

Our education predictor variables (and all other EFC variables, here employed as control variables) were derived from GEM’s national expert survey. These variables are standardized scales based on responses to multiple items as described in the previous subsection and listed in Appendix 1. Excluding Education and Training, the EFC variables are presented in the regression in the customary GEM order, with the following labels:

Financial: Finance EFC

-

Government Policies

-

Government Policies: Policy EFC

-

Government Regulations: Regulations EFC

-

-

Government Programs: dropped due to high collinearity

-

R&D Transfer: dropped due to high collinearity

-

Commercial, Legal Infrastructure: Business services EFC

-

Internal Market Openness

-

Market Dynamics: Market dynamism EFC

-

Market Openness: dropped due to high collinearity

-

-

Access to Physical Infrastructure: Physical infra EFC

-

Cultural, Social Norms: Entrep culture EFC

-

The Education and Training EFC is presented separately and is measured with two variables:

-

Primary and Secondary Level Education and Training: Primary education EFC

-

Post-secondary Level Education and Training: Higher education EFC

-

Our measures of Entrepreneurial Opportunity and Entrepreneurial Capacity were taken from two GEM adult population survey items asked of all respondents. Perception of opportunity, labeled Opportunity perception, was measured as the percentage of working-age adults that expressed an opinion and agreed with the statement: “In the next 6 months, there will be good opportunities for starting a business in the area where I live.” Perception of capacity, labeled Start-up skills, was measured as the percentage of working-age adults who expressed an opinion and agreed with the statement: “I have the skills, knowledge and experience required to start a business.”

We also used a number of control variables, representing the Social, Cultural and Political Context in the GEM model. As discussed in the previous section, it has been shown that a country’s wealth has a significant effect on the opportunities available (Shane 2003, p. 147) and its entrepreneurial activity (e.g., Van Stel et al 2005; Acs et al. 2008b). Therefore, we controlled for the country’s GDP per capita (purchasing power parity), measured as current US dollars per capita and labeled GDP per cap (ppp). These data were obtained from the IMF database.Footnote 15 We also introduced a grand mean-centered and squared term of the GDP per capita variable into the equation to capture any curvilinear effects, labeled GDP per cap (squared). A country’s rate of population growth is likely to impact opportunities through increased demand for goods and services (Shane 2003, p. 32). We therefore controlled for population growth rate, obtained from the IMF database and labeled Population Growth. A country’s general economic conditions will impact the presence of economic and start-up opportunities. We therefore controlled also the country’s GDP growth from previous year to present year, measured in current national currency and labeled GDP change. These data were also obtained from the IMF database. Finally, we controlled for year effects (not shown in the tables, but data available on request).

The GEM model predicts that a country’s General National Framework Conditions (GNFC) will affect its level of entrepreneurial activity, by influencing the nature of EFCs. As a proxy of the country’s GNFC and general economic competitiveness, we used the country’s Global Competitiveness Index (GCI) score, as computed by the World Economic Forum. Because the GCI index has been modified over the years, we used only those years for which a standardized form exists. The GCI score of 2003 was used for years 2000–2003, and the 2006 score was used for years 2004–2006. However, we decided to drop this control because of its high correlation with GDP per capita (>0.8). This did not affect our findings.

Industry structures vary among countries, impacting the size distributions of firm populations (Fisman and Saria-Allende 2004). We therefore controlled for the adult-population prevalence of established entrepreneurial firms in the economy, labeled as Estab. e-ship rate. These data were obtained from GEM’s adult population surveys. Contemporaneous data were used for this variable in the equations.

In order to control the robustness of our regression analyses, we also employed alternative control variables. We ran the same regressions using Index of Economic Freedom indices for business freedom, trading freedom and freedom from corruption, respectively. The IEF business freedom index measures the ease of starting a new firm in a given country, and it could be reasonably used as a proxy of GEM’s EFC for regulations. The IEF trading freedom index measures how easy it is to trade within a given country, as well as to engage in import and export activity. The corruption index measures the strength of corruption in a given country, providing a good proxy for its institutional stability, as well as the rule of law. These indices were used since they covered all of the participating GEM countries from 2000 to 2006, and they had not been changed during the period. Because of high correlations, specifically between the corruption index and GDP per capita, not all controls could be introduced simultaneously into the equations. In total, more than 30 alternative combinations were checked. The findings reported here appeared robust to altering specifications of control variables.

4.3 Estimation issues

Our dataset consisted of unbalanced panel data with a broad and relatively short structure, with several predictor variables and relatively short time series (maximum 7 years). Only a few countries are present in the panel for all years. Because our dependent variable was potentially autocorrelated, we used the Baltagi-Wu test to check for this possibility (Baltagi and Wu 1999). Because the Baltagi-Wu test provides an appropriate statistic for unbalanced panel data, it is recommended instead of the more commonly used Durbin-Watson test, which may be sensitive to gaps in the panel structure. There are no exact critical values for the Baltagi-Wu test in the literature, but values “much smaller than 2” are suggestive of the need to correct for serial autocorrelation (Kögel 2004). In none of our regressions with the three dependent variables (TEA, HEA and rHEA) did the Baltagi-Wu conflict with this threshold, and we therefore ran generalized least squares models without controlling for serial autocorrelation in error terms.

We used the Hausman test to check whether a fixed- or random-effect specification should be used for the GLS panel regression. The Hausman test measures the correlation between the residuals of pooled least squares and the independent variables. The test suggested the use of fixed-effects specification for TEA, HEA rHEA models, although in some instances the test suggested the use of random-effects model. For consistency, we opted for using fixed-effects specification for all models. Fixed effects specification is less efficient than the random-effects specification due to loss in degrees of freedom, making it more conservative than the random-effects specification.

To eliminate collinearity problems, we removed any predictors with inter-correlations of 0.7 or greater. This resulted in the removal of the following controls from the model: government programmes; R&D transfer; market openness.Footnote 16 The sigmamore specification was used when running the Hausman tests because the scales of the variables used were quite different from one another—a situation to which the Hausman test is occasionally sensitive. To control for potential heteroscedasticity in error terms arising from grouping by country, we specified robust standard errors when running the models.Footnote 17 There were only negligible differences between robust and non-robust specifications.

The final models tested the effect of the education EFC on Opportunity perception, Start-up skills, TEA, HEA and rHEA with the controls described above, then tested the effect of EFCs on TEA, HEA and rHEA with first Opportunity perception, and then Start-up skills added to the equation. In this way, we were able to test for possible mediation effects of Opportunity perception and Start-up skills on associations between the new business activity variables and education and training EFC variables, as predicted by the GEM model.

5 Results

Tables 1 and 2 indicate the results of the main tests of hypotheses H1, H2 and H3 for the full country sample and for high income countries only. Two-way significances are used for all variables in all tables. Fixed-effects GLS coefficients and significance levels are shown in the tables. In the interest of space, year effects are controlled, but not shown.

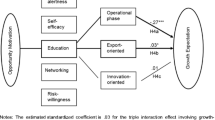

Table 1 shows the results of the analysis for the two education EFCs, Opportunity perception, and types of entrepreneurial activity for all countries in our sample. The leftmost column shows effects on Opportunity perception, and the remaining columns show effects on the three entrepreneurial activity variables, with and without Opportunity perception present in the equation to test the mediation hypothesis H3. We find that, in the overall dataset, Opportunity perception is not significantly associated with either of the two education EFCs. We also find that all three entrepreneurial activity indices are positively and significantly associated with Opportunity perception. Also, all three entrepreneurial activity indices are positively and significantly associated with Higher education EFC. Thus, in the overall dataset, we find support for the expected direct effects of post-secondary entrepreneurship training and education and perception of opportunity (H1), as well as for opportunity perception and entrepreneurship indices (H2), but not for the mediation effect (H3). However, Higher education EFC exhibits positive, direct associations with indices of entrepreneurial activity.

There is good reason to believe that entrepreneurial activity might be associated with different national framework conditions in high- and low-income countries, respectively (Wennekers et al. 2005). We therefore ran the same analysis for the group of high-income countries, using the per-capita income of US$ 20,000 as the threshold. This cut-off point gave us 27 countries and a total of 147 year-country observations to work with (average 5.4 observations per country). The results of this analysis are shown in Table 2.

As can be seen in Table 2, in the high-income countries, Opportunity perception is significantly and positively associated with Higher education EFC. Both TEA and HEA are also significantly and positively associated with Higher education EFC. However, when Opportunity perception is introduced in the equations, Higher education EFC loses its significance, and the effect of Opportunity perception emerges as significant. Thus, in the high-income countries, hypotheses H1, H2 and H3 receive support for TEA and HEA, but not for rHEA. Interestingly, for TEA, a negative and significant association is shown with Primary education EFC.

Tables 3 and 4 show the test of hypotheses H4, H5 and H6 concerning entrepreneurship training and education, perception of start-up skills and entrepreneurial activity. Again, we show separate analyses for the overall GEM dataset and for the subset of high-income countries.

The analysis comprising the full dataset is shown in Table 3. No statistically significant association is apparent for the relationship between Start-up skills and the two education EFCs. All entrepreneurial activity indices exhibit a positive and significant direct association with Higher education EFC. TEA and HEA, but not rHEA, exhibit a positive and significant association with Start-up skills. Thus, in the overall dataset, we have support for H4 (link between skills and measures of entrepreneurial activity) but not for H5 and H6 (effect of education on skills and the mediating effect). Again, we observe positive, direct associations between TEA and HEA and Higher education EFC.

The analysis comprising high-income countries is shown in Table 4. In this sub-set, there is a positive, statistically almost significant association between Higher education EFC and start-up skills. We also observe a mediation between Higher education EFC and start-up skills for TEA. However, similar mediation is not observed for HEA or rHEA, which do not exhibit any statistically significant association with start-up skills. Thus, for TEA, we have weak support for H5 (link between higher education and skills), support for H4 (link between skills and TEA) and support for H6 (the mediation effect). As for the overall sample, we also observe a direct link between Higher education EFC and HEA and rHEA.

6 Discussion

6.1 Overview of findings

We set out to provide the most rigorous test to date of the relationship between entrepreneurial education and training and GEM’s measures of national entrepreneurial activity. Given the strong and continuing policy interest toward entrepreneurship education, we considered it important to examine whether it really impacts entrepreneurship and whether the impact might differ for different types of entrepreneurial activity. After rigorously controlling for intervening influences, we found that entrepreneurship education probably does matter, and in quite specific ways. In high-income countries, post-secondary entrepreneurship education and training are positively associated with the level of new business activity, including high-growth expectation business activity, by enhancing the level of opportunity perception in the population at large. On the other hand, the level of post-secondary entrepreneurship education and training appears to be only weakly associated with the level of skills, and it appears to affect only levels of new business activity, and not high-growth expectation entrepreneurial activity, through its effect on perceived start-up skills.

The finding that entrepreneurship training affects new business activity primarily through enhancing opportunity perception, rather than start-up skills perception, has several implications for policy. The received literature on entrepreneurship education has tended to emphasize the role of education in the provision of instrumental skills to start up new firms. However, even though the perception of skills is directly associated with the level of new business activity in a country, education appears to have little role in fostering such skills. There are several possible explanations for this. One reason for this finding may be that education, post-secondary education in particular, tends to focus more on theory than practice. Thus, the observed lack of mediation may simply signal that entrepreneurship training and education are not practice-oriented enough to cultivate instrumental start-up skills within the population. An alternative explanation may be that the skill-set required to start new firms is too general and broad-based to be effectively taught in educational institutions, and they may be better acquired through work experience. A third possible reason may be that the necessary skill set may incorporate intangible social resources, such as entrepreneur-centric social capital, which are likely acquired through experience rather than through formal education and training. Finally, it may be that entrepreneurship education and training may not have advanced to the level of, say, medical schools in equipping students with the skills, knowledge and experience necessary to practice their profession. Whatever the reason, the findings suggest that the instrumental emphasis, which pervades much of received literature on entrepreneurship education and training, may be misplaced, at least in part.

The observed mediating effect between Higher education EFC, opportunity perception and entrepreneurial activity emphasizes the cognitive aspects of entrepreneurship education and training. This finding is in line with the ‘Austrian’ perspective on entrepreneurship. Recognizing and assessing opportunities for setting up new productive functions in the economy often involves complex cognitive processing. Where others may not ‘see’ anything, a cognitively endowed individual may see a significant business opportunity. It appears that, consistent with much of the ‘Austrian’ theorizing, the cognitive aspect of the entrepreneurial market process may be the critical bottleneck for entrepreneurial activity, one which educational institutions may be well positioned to address.Footnote 18 Post-secondary entrepreneurship education may be performing an ‘eye-opening’ role—hence its effect on opportunity perception—but may not be sufficiently experiential to give trainees the confidence that they have the necessary experience.

The strongest signal emerging from this study is the importance of entrepreneurial education and training at levels that are appropriate to a country’s level of development for both general and high-growth expectation entrepreneurial activity. During our analysis, we observed robust direct associations for Higher education EFC and types of entrepreneurial activity—high-potential entrepreneurial activity in high-income countries in particular. This pattern was robust to alternative model specifications and alternative specifications of control variables. Whether entrepreneurship education operates mainly through opportunity perception, skills or through some other unmeasured mechanism (e.g., social capital, personal networks and peer recognition), an important message for policy is that Higher education EFC appears to matter for high-income countries. Overall, the level of an individual’s education is positively associated with his or her entrepreneurial growth aspirations (Autio and Acs 2007) and entry into and success in self-employment (Dolinsky et al. 1993; Robinson and Sexton 1994). Our findings suggest that providing entrepreneurship education and training at post-secondary-level educational institutions in high-income countries will influence the career decisions of those individuals who are likely to possess the kind of skills, competencies and social capital required to launch high-growth ventures, at a crucial time of their personal and professional development. Even though most students will not, and probably should not, start new firms immediately after graduation, entrepreneurship training and education may have a long-lasting effect on their entrepreneurial alertness and motivation.

We offer four possible reasons why entrepreneurship education and training in post-secondary levels of education in high-income countries operates to enhance both general new business activity and high-potential entrepreneurial activity. First, such training is targeted to a population cell that has, by virtue of its educational background and social standing, the best opportunities to start new high-growth ventures. Second, such training would reach high-potential individuals when they are at a crucial stage in their professional development and thus likely to be actively making career decisions. Third, such training helps improve both the entrepreneurial self-efficacy of high-potential individuals, as well as their perceptions of the social desirability of entrepreneurial career choices. Fourth, the alternatives of unproductive or destructive entrepreneurship are likely to be unattractive in high income countries, because rule of law is stronger. Thus, allocation of effort by highly educated individuals into productive entrepreneurship is likely to be relatively high in high-income countries. All these factors serve to boost the entrepreneurial propensities of those most likely to have the skills, will and desire to succeed. Furthermore, the building of entrepreneurship education capability in colleges and universities will enable the provision of advanced training at continuing professional development level to graduates at any stage in their career. Such elite training of highly committed individuals is widely accepted in management, but less so in entrepreneurship.

As regards the control variables, we found that few of the other EFCs influenced entrepreneurial activity. Even though bivariate correlations for EFCs and TEA can be observed for this variable in cross-sectional settings, those correlations disappear in a more rigorous test that controls for intervening influences. We infer from this that a given country’s overall level of entrepreneurial activity (i.e., TEA) is not significantly affected by most external conditions that are directly addressable by national policy-makers. This would support Leibenstein’s view that institutions, as distinct from opportunities, have little impact on entrepreneurship levels.