Abstract

This paper explores the relation between supply-chain participation and the internationalization of firms. We show that even small and less productive firms, if involved in production chains, can take advantage of reduced costs of entry and economies of scale that enhance their probability of exporting. The empirical analysis is carried out on an original database, obtained by merging and matching balance-sheet data with data from a survey on over 25,000 Italian firms, which include direct information on the involvement in supply chains. We find a positive and significant relation between being part of a supply chain and the probability of exporting, as well as the intensive margin of trade. The number of foreign markets served (the extensive margin), on the other hand, does not seem to be affected. We also investigate whether being in different positions along the chain, i.e., upstream or downstream, matters, and we find that downstream producers tend to benefit more. Our results are robust to different specifications, estimation methods, and the inclusion of the control variables typically used in heterogeneous firms models.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

International trade models have recently highlighted that the heterogeneity of firms often results in self-selection in foreign markets. The presence of entry costs and imperfect competition allows more productive firms to enter (stay in) foreign markets and to upgrade, while (initially) lower productivity firms, given the costs of internationalization, are likely to be confined to the domestic market. Hence, successful exporting firms tend to be relatively few, but they are larger, more productive, and generally better performers according to a number of indicators (Melitz 2003; Bernard et al. 2007; Melitz and Redding 2014). The empirical support for these predictions is nowadays robust (see Wagner 2012, for a recent review).

A related strand of the literature has emphasized the importance of the international fragmentation of production and specialization in trading “tasks” rather than goods (Grossman and Rossi-Hansberg 2008). The related evidence suggests that firms find different ways of internationalizing, by exploiting their specialization, by being involved in importing activities, and by joining global supply chains (Castellani et al. 2010; Baldwin and Lopez-Gonzalez 2014). An active involvement in supply chains is likely to enhance efficiency, by allowing firms to specialize in functions which suit their capacities better and to upgrade in a number of different ways, including through exports and innovation (Humphrey and Schmitz 2002; Gereffi 1999; Agostino et al. 2014; OECD 2008; Giunta et al. 2012). Furthermore, involvement in supply chains can be seen as a rational choice since it potentially reduces agency and transaction costs, and, through formal and informal relations with other firms, allows a more efficient transfer of resources (Wynarczyk and Watson 2005; Atalay et al. 2014).

These two strands of the literature, however, have some limitations. On the one hand, the literature on heterogeneous firms has highlighted the mechanisms of the internationalization process, especially for large firms; on the other hand, the literature on the supply chain has mainly focused on firms that are already operating at global level. Moreover, the empirical evidence rarely focuses directly on small enterprises (SEs).Footnote 1 The evidence of the participation of SEs in the global market, as well as that of the effects of supply-chain participation on the internationalization of firms, is therefore still limited. It is often restricted to factors which hamper internationalization, such as the role of family ownership or the lack of human capital and poor access to credit, rather than to the factors which enhance the capacity of firms to internationalize, including, for instance, innovation, networking, and interfirm contractual arrangements (Higón Añón and Driffield 2011; OECD 2012; Cerrato and Piva 2012; Bricongne et al. 2012).

SEs, which represent the vast majority of firms, jobs, sales, and value added in many economies (Park et al. 2013), play an important role in supply chains and are becoming increasingly internationalized. Empirical research highlighting the interaction of heterogeneity benefits with advantages of belonging to a supply chain is therefore not only relevant, but also of immediate policy interest.

Participation in a supply chain may enhance the internationalization of firms through complex and highly interrelated mechanisms. A major example of these mechanisms concerns incomplete contract theory and specialization (Grossman and Helpman 2002; Grossman and Hart 1986; Antràs 2003). In line with Antràs and Helpman (2004), heterogeneous firms deciding whether, and, if so, how to fragment their production (domestically and/or internationally) are likely to undertake a relationship-specific investmentFootnote 2 in an incomplete contracts environment. An example of such a situation can be found in the decision regarding where to position themselves along the supply chain, according to their specialization. Since inputs are often customized to the buyers’ needs, trust between agents becomes key.Footnote 3 Recognizing the importance of trust has been used to justify the fact that firms could internationalize through vertical foreign direct investment (FDI). However, the fixed costs faced by the firms along the supply chain are likely to be lower vis-à-vis vertical integration, except in cases in which the intra-firm trade along the chain involves valuable intangible resources (Atalay et al. 2014). Hence, being part of a supply chain (domestic or international) is a strategy that could be chosen also by relatively less productive firms, such as small firms and suppliers, which, otherwise, might not be able to afford the costs of vertical integration. As a consequence, supply chains can enhance the engagement of SEs in international markets, by opening new niches, also for service suppliers, and allowing firms to overcome information costs, incompleteness of contracts and other structural barriers to internationalization.

This paper exploits an original dataset based upon a survey conducted by MET (Monitoraggio Economia e Territorio) on over twenty-five thousands Italian firms. The survey includes direct information on the involvement of firms in supply chains. Most existing studies use the status of the supplier as a proxy for participation in supply chains; we, however, rely upon a direct measure of the involvement of firms: the answer to an ad hoc question in the survey. Thanks to this unique information, this paper is able to investigate the link between supply chains and internationalization, from a different perspective and with a focus on small firms.

Italy provides an ideal setting to our analysis for at least two reasons. On the one hand, substantially more than in other European countries, small and medium enterprises (SMEs) represent the bulk of the productive structure, employment, and the contribution to the overall export performance (Navaretti et al. 2011). On the other hand, Italy’s sectorial specialization and industrial structure have triggered a high division of labor among firms, many of which often work as specialized suppliers. Some recent work has highlighted how traditional small suppliers can take advantage from the international fragmentation of production to engage in more complementary activities with the final firms and improve their performance (Giunta et al. 2012; Agostino et al. 2014). Furthermore, Italian SMEs often engage in formal and informal networking at local level (Giovannetti et al. 2013), involving co-operation among specialized firms, in order to achieve collective efficiency and better performance compared to firms outside industrial districts (Becattini 1990; Brusco and Paba 1997; Di Giacinto et al. 2014). External economies at district level also affect the international projection of small firms, and, therefore, their traditional sources of competitiveness (Crouch et al. 2001; Becchetti and Rossi 2000).

Our results show that belonging to a supply chain helps to offset some of the competitive disadvantages of SEs (e.g., lower levels of productivity), as it is positively correlated with (1) their probability of exporting and (2) the intensive margin of export (measured as a share of the total exports on turnover). On the other hand, supply-chain participation does not seem to affect the extensive margin, measured as the number of foreign markets served, in line with the view that structural limits linked to the size matter for the international expansion of SEs. Coherently with recent advancements in the literature (Antràs et al. 2013), we show that firms involved in downstream activities benefit more from being part of a supply chain.

Our results suggest some important implications, especially for countries like Italy, characterized by a high number of small firms and a fragmented production system. In a rapidly changing international context, new opportunities emerge for firms, including the smaller ones, which specialize in the different phases of the supply chains. Without entering the debate on the factors which affect a firm’s involvement in supply chains, our findings seem to support the view that high specialization of domestic firms in well-defined processes and tasks has a potential to enhance their integration in global production. However, our results also suggest that only a small fraction of domestic firms is able to integrate in supply chains autonomously, thus calling for specific policies which support the inclusion in more organized, domestic and global, production processes.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows: Sect. 2 describes the data and definitions, while the estimates of the relations between supply-chain participation and the internationalization of firms using different methodologies are presented in Sect. 3. Section 4 concludes.

2 Data and descriptive statistics

Our main source of information is the MET 2011 survey, covering 25,090 Italian firms belonging to manufacturing and service sectors. The survey includes detailed information on employment, input, sales, investments, internationalization modes, innovation, as well as participation and the role of firms within networks and supply chains over the period 2009–2011. In order to estimate total factor productivity (TFP), we merged the MET survey data with the balance-sheet information from AIDA, a database published by the Bureau van Dijk. This merged dataset contains 7,590 firms,Footnote 4 and its characteristics are in line with those of the most recent census for Italy (ISTAT 2013). A detailed description of the dataset is provided in the “Appendix.”

In the existing literature, supply chains are defined in a number of different ways, all built around the existence of an input/output (I/O) structure, which includes a range of value-added activities (Park et al. 2013; Baldwin and Lopez-Gonzalez 2014; Gereffi et al. 2001). The most recent attempts to measure a country’s involvement in (global) production chains use finely disaggregated I/O tables to determine their distance to the final consumption of the goods produced (Antràs et al. 2013).

In this paper, we take advantage of a direct measure of the involvement of firms in supply chains, defined in the survey as a “participation in a specific supply chain, implying a continuative contribution of the firm to specific productions, provided that this activity constitutes the majority of the firm’s turnover.”

The definition that we use in this paper has several advantages with regard to the existing studies at firm level, which, to date, rely on the simple status of subcontractor or supplier of intermediate goods as a proxy for participation in global supply chains (Wynarczyk and Watson 2005; Accetturo et al. 2011; Agostino et al. 2014). First, it is based upon a direct answer from a firm’s representative. Second, it captures the specialization of the firm in specific tasks within a well-defined production process.Footnote 5 Finally, thanks to specific information on the firm’s upstream and downstream activities, it also allows us to control for the role of each firm within the production process.

However, this definition of supply-chain participation has some disadvantages, too: It does not clearly allow the type of interactions arising among the firms within the supply chain (i.e., arm’s length vs. collaborative) to be established and does not explicitly address the deepness of the input/output structure of the production of the firm. For this reason, as a robustness check, we built a proxy of supply-chain participation based upon the input/output relationships of each firm, in line with the variable used in the existing literature (Agostino et al. 2014). The variable includes firms that buy and/or sell intermediate inputs, and, at the same time, have some degree of participation in the design of the final product.Footnote 6 As expected, this variable is positively correlated with the “self-reported” assessment on supply-chain participation (i.e., the answer to the specific question in the survey). For about 78.7 % of the firms, the two variables provide the same information.Footnote 7

According to our definition, firms belonging to a supply chain represent 15.7 % of the sample, the majority (82.3 %) being manufacturers. The share of exporters (40.3 %) rises to 58.3 % for firms in a supply chain. Table 1 reports the share of exporters by employment class, highlighting those in supply chains. The comparison of the two columns suggests that belonging to a supply chain increases the share of exporters for all the employment classes, but particularly for smaller firms.

The survey also provides direct information on the involvement of firms in network activities. Networks are defined as “relevant and continuative relationships with other firms and institutions.” It is worth noting that such network relationships consist of a range of many different activities that are independent from the type of production relationships within the supply chain. While relationships within supply chains are prevalently related to the production process and are based upon firm-to-firm agreements, network relations are more varied, including, for instance, R&D or commercial activities, and involve different partners, such as institutions, research centers, and universities.

Some firms in supply chains are outside the “network,” as defined in the survey (54.8 % of supply-chain firms), while others belong to a network, but do not operate within a supply chain (78.1 % of network firms). Thus, we have firms involved in supply chains, which are not involved in any other form of continuative collaboration (for instance, commercial or of research) with the firms outside the value chain or institutions, and firms that, instead, have relationships with other firms or institutions, but not of the specific type arising within a supply chain. The survey allows us to distinguish local, domestic (national), and foreign networks. Table 2 reports the share of firms involved in the various activities (buying, selling, design, marketing, etc.) by the type of network and/or supply chain.

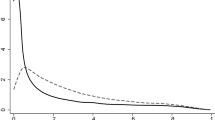

The empirical literature on heterogeneous firms has shown the existence of a hierarchy of firms in terms of productivity and other performance indicators, by mode of internationalization (Helpman et al. 2004). Exploiting the information on the FDI activities of Italian firms from the ICE-Reprint database after merging it with MET and AIDA data, we compute total factor productivity for Italian firms.Footnote 8 About 9.5 % of firms are both exporting and involved in FDIs; this corresponds to 24 % of the FDI firms among the exporters and to 73.8 % of the exporters among FDI firms. Our TFP estimates are in line with the findings of the literature and show that productivity premia are different for the different internationalization modes (Fig. 1). On average, the productivity premium tends to increase with the exported value, and large exporters are generally involved in more complex internationalization forms, such as FDIs. Interestingly, some evidence of heterogeneity emerges if we consider the role of the supply chain. Firms integrated into a supply chain show a level of productivity in-between that of non-exporters and exporters (Fig. 1a), suggesting that participation in a supply chain should definitely be further analyzed. This is in line with Antràs and Yeaple (2014), who, concentrating on Spanish firms, find an organizational sorting in which outsourcing, be it domestic or global, is performed by the least productive firms, while the most productive firms are more likely to choose integration at home or abroad.Footnote 9

3 Empirical analysis

In what follows, we formally explore the relation between participation in a supply chain and the probability of exporting, taking the features of the firm into account and disaggregating our sample in order to check whether the relation is consistent with different specifications.

Our baseline specification is a standard probit model:

where Yi = {0,1} is the export dummy for firm i,Footnote 10 Φ(•) is the c.d.f. of the standard normal distribution, α is the constant term, and γi and δi are regional and sector effects, respectively.

Our variable of interest is the dummy measuring the participation of the firm in supply chains (SCi). In line with the literature, we control for size, age, group, and innovation, and the firm’s involvement in FDIs (see, for instance, Navaretti et al. 2011; Giovannetti et al. 2013; Bartoli et al. 2014). We also explicitly control for the firm’s network participation at local, domestic, or global level.Footnote 11 Table 3 reports the descriptive statistics.Footnote 12

Results from the regressions, reported in Table 4, are consistent across the different samples, highlighting an overall stability of the relations observed.Footnote 13 In line with the existing evidence, we find that the probability of exporting increases with the age of the firm and with the participation in a group, and that innovation is a key driver of internationalization (Grossman and Helpman 1991). Not surprisingly, we also find that the firms involved in FDI operations are more likely to be exporters. The introduction of a dummy variable to identify small-sized enterprises (<50 employees) confirms that larger companies are more likely to internationalize (Melitz 2003; Mayer and Ottaviano 2008).Footnote 14

Firms belonging exclusively to local networks are less likely to export, while networking with foreign firms fosters internationalization, thereby reducing the transaction costs of exploring far-away markets. The negative and significant sign of a “local network” seems to suggest that firms able to exploit the positive impact of local networks on their productivity have fewer incentives to internationalize. This is in line with the literature stating that benefits from clustering are very localized (Duranton and Overman 2008) and that geographic proximity, organizational proximity, and social interactions are the channels through which the externalities have an impact on firm’s decisions.

Last, but not least, belonging to a supply chain is positively correlated with the probability of exporting, and this result is robust to the introduction of regional and sector fixed effects (Column 2). Hence, we find preliminary evidence that exporting can be considered to be a positive spillover of being part of a supply chain.

In line with the literature on heterogeneous firms, we introduce the lagged level of TFP and its percentage change over the period 2007–2011 as additional controls (Columns 3 and 4 of Table 4).Footnote 15 Controlling for changes in productivity allows us to analyze the possibly asymmetric effects of the recent crisis on the different types of firms in the sample. This, in turn, allows us to say that the results for the supply chain are not driven by post-crisis specific circumstances. Both the initial levels of productivity and its growth are positively correlated with the probability of exporting. This result meets both our expectations and that of the literature on heterogeneous firms. First, in line with Melitz (2003), firms with higher initial productivity are more likely to be exporters. Second, given the initial level of productivity, firms that experienced a higher increase in the TFP are more likely to be exporters. This seems to suggest that they are likely to be relatively less affected by the crisis. Finally, and more importantly for our purposes, controlling for productivity does not change our findings: Being integrated into a supply chain is positively correlated with the probability of exporting. More precisely, considering the marginal effect of our preferred model (Column 4 of Table 3), we can say that belonging to a supply chain can increase the probability of exporting by between 6.1 and 8.0 % points on averageFootnote 16 and correctly predicts 72.5 % of the observations.Footnote 17

3.1 Supply chain and internationalization of SEs

To check whether size matters, we estimate the previous model separately for small (<50 employees) and medium–large firms (MLEs, with more than 50 employees). Columns 5 and 6 of Table 4 suggest that the aggregation masks important differences. Participation in a group is not significantly correlated with the probability to export of SEs. On the other hand, the introduction of new products seems to matter. This is not surprising, especially if seen in relation to the participation in supply chains, where product innovation is a core strategy to upgrading (Agostino et al. 2014; Park et al. 2013). As far as their networking strategy is concerned, in line with previous results, domestic and global networks are positively related to the internationalization of SEs, while local networks are not. In line with our expectations, more productive SEs are more likely to export. However, for larger firms, the TFP coefficients, though positive, are not significant. This asymmetry is possibly due to nonlinearities for larger firms, for which further increasing size and productivity is likely to have a small correlation with an already relatively high export probability.

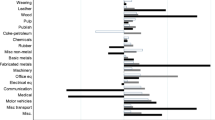

More relevant for our research question, belonging to a supply chain has a clear positive relation with the internationalization of small firms and is not significant (albeit still positive) for larger firms. This result comes as no surprise if we go back to the mechanisms linking supply-chain participation and internationalization described in the introduction. As noted above, involvement in a supply-chain relation may entail lower entry costs, due to well-defined contractual arrangements with other companies along the chain, and may facilitate access to cheaper and/or higher quality intermediate inputs. In addition, being part of a supply chain may be the preferred strategy when capital and R&D intensity are relatively low, since such inputs are more likely to be controlled by downstream firms. Larger firms, on the other hand, might be relatively unaffected by supply-chain participation, since their structural characteristics are more likely to project them internationally, independently of whether they belong to the chain or not. The marginal effects computed by running different regressions for small and larger firms suggest that belonging to a supply chain can increase the probability of exporting by 6.2–7.7 % points for SEs. As a robustness check, and to have a more detailed picture of how the size affects these results, we run two separate sets of regressions for different size thresholds. In the first set, we consider smaller firms only (up to five employees) and progressively increase the upper bound; in the second set, we do the opposite, i.e., start from the larger firms (at least 300 employee) and progressively reduce the lower bound (see Tables 10 and 11 in the Appendix).Footnote 18 Clearly, once the upper bound is sufficiently high or the lower bound sufficiently low, the regression results converge to the aggregate results. Figure 2 depicts the marginal effects of belonging to a supply chain on the probability of exporting, together with their confidence interval, and confirms that they are higher for smaller firms, while no significant effect emerges for larger firms.Footnote 19

The above results seem to suggest that belonging to a supply chain may, to some extent, foster the internationalization of smaller and less efficient firms. If this is the case, one will expect a lower correlation between the probability of exporting and productivity, for firms participating in a supply chain. To test this hypothesis, we introduce in our model an interaction term, defined as the product of the supply-chain dummy and the initial total factor productivity. The coefficient of the interaction term is negative and significant only for small firms, and positive and non-significant for larger firms.Footnote 20 Note, however, that the interpretation of the interaction effect in nonlinear models (such as probit) requires some caution, since it cannot be directly interpreted as in linear models (Ai and Norton 2003). For this reason, we also compute corrected interaction effects for the case of a dummy–continuous variable interaction, following the procedures suggested by Norton et al. (2004). The corrected z-statistics for small and medium–large firms are reported in Fig. 3. The interaction effect is found to be negative and statistically significant for small firms with a predicted probability of export between 40 and 80 %, while it is negative but non-significant otherwise (Fig. 3a); in contrast, no significant effect is found for medium–large firms (Fig. 3b). The interaction term seems to suggest that even the less productive among the small firms can internationalize, conditional to their participation to a supply chain. Overall, thus, our evidence supports our underlying assumption that supply-chain participation provides smaller and less productive firms with additional advantages to be exploited in their internationalization process.

3.2 Intensive and the extensive margins

In order to check whether the positive relationship between participation in supply chains and export performance can be confirmed for alternative measures of internationalization, we compute the intensive and extensive margins of trade at firm level. The intensive margin is calculated as the share of exports over total turnover, while the extensive margin has been constructed as an index which includes the number of different geographic destinations served by the firm.Footnote 21 On average, firms in our sample export 14.2 % of their turnover, whereas firms in supply chains export 21.7 %. With regard to the number of destination markets, the average is 2.1 for all exporting firm (0.83 for all firms), while firms in supply chain reach 2.3 markets.

To measure the relation between supply-chain participation and the intensive margin, we estimate a Tobit model with left censoring at 0. The results, displayed in Columns 1–3 of Table 5, are in line with the previous ones: The same variables that affect the probability of exporting also contribute to the intensity of exports. Again, a significant difference emerges between firms of different sizes. We find that not only does participation in supply chains foster the internationalization of small firms, but also that their high levels of specialization and the likely deepening of linkages along the chain make SEs more dependent on foreign network relationships.

Conversely, we do not find any evidence that being part of supply chains has positive spillovers on geographic diversification. The results reported in Columns 4–6 of Table 5 and obtained by means of a negative binomial estimator show that the geographic scope of SEs does not improve when they are in supply chains. Interestingly, larger firms in supply chains seem to take advantage of it, with a significant probability of operating in different markets, independently of their distance. Our findings for the extensive margin of trade suggest that size still needs to be considered a structural barrier to the international expansion of SEs and that being part of a supply chain cannot be a substitute for the lack of other structural resources.

The above results could be due to the existence of different entry costs. SEs may, therefore, benefit more from supply-chain participation through reduced entry costs in foreign markets. Hence, firms in supply chains are more likely to internationalize and to export a larger share of their turnover. However, increasing the number of destination markets and reaching distant markets may involve additional costs, and size once again becomes a stringent requirement.

3.3 The role of firms within the supply chain

We showed that small firms, less likely to internationalize, might partly overcome their intrinsic weaknesses through an active involvement in a supply chain. However, they are themselves heterogeneous, and different firms involved in the production of the same final product may have different roles, degrees of monopoly power, and proximity to the final market. More precisely, the position along the chain is likely to determine the benefits that can be obtained, and the activities offering greater revenues are often intangible (Antràs et al. 2013). Ignoring these differences may bias the results, even when firms are of a similar size and share other common characteristics. In a pioneer model, Antràs and Chor (2013) consider a setup in which the existence of a number of many (sequential) suppliers gives rise to differential incentives to integrate along the supply chain. The position, i.e., being upstream or downstream, determines whether a given task or a given input is better produced by an independent supplier or an integrated firm.

In Italy, firms tend to outsource part of their production more than other countries while being less prone to international integration (Federico 2012). This could be linked to the diffuse presence and historical relevance of industrial districts, characterized by a tight division of labor and a large diffusion of sub-contracting practices (Accetturo et al. 2011). These stylized facts are in line with theoretical models which show that smaller, less productive firms are more likely to outsource and, hence, to be part of production networks (Antràs and Helpman 2004). However, while this could explain, together with other factors, why Italian SEs may find it convenient to be involved in supply chains in order to outsource, little has been said on their role as subcontractors. The existing evidence highlights a consistent sub-contracting discount, and a marginal role of subcontractors in terms of performance, when compared to final producers (Razzolini and Vannoni 2011). More recent studies, however, find a large degree of heterogeneity within the group of subcontractors, showing that the opportunities offered by involvement in supply chains might allow them to escape “captive” contractual arrangements and provide an incentive to upgrade, including through innovation and export (Giunta et al. 2012; Agostino et al. 2014).

In order to take such heterogeneity into account, we re-estimate our baseline model by introducing a new set of variables. From our database, we know the share of total sales for each respondent by type of product (final vs. intermediate) and to what extent each firm produces for other firms or on their own. We, therefore, distinguish three types of firms: (1) a final-good producer: A firm whose sales are entirely constituted by final consumption and final industrial goods; (2) a subcontractor: A firm that works only on a contractual basis for other firms; and (3) a “own-branded” firm: A firm that sells own-designed proprietary products (i.e., a firm that designs its own products, final or not, and retains the industrial property, either with or without patents).Footnote 22

To account for these considerations, we introduce other controls into our baseline model (Table 6). The resulting regressions are robust: All coefficients have the same sign, and their numerical value is similar to previous results. While belonging to the supply chain keeps its explanatory power, final-good producers strongly emerge as those with the highest probability of exporting; furthermore, in line with the above-mentioned existing empirical evidence, we find confirmation of a sub-contracting discount.

Columns 2–4 present the results for the subsamples of subcontractors, own-branded firms, and final-good producers, respectively. We find that belonging to a supply chain is highly correlated with the probability of exporting for both final-good producers and own-branded firms. The supply-chain coefficient is positive also for subcontractors, but is not statistically significant.

Our results suggest that participation in supply chains is particularly beneficial to downstream producers, such as “final” firms, possibly due to a more effective organization of the upstream production process. Moreover, supply-chain participation is likely to enhance the specialization of firms with their own-designed proprietary products, increasing their probability of exporting. All in all, these findings seem to suggest that downstream firms, which have some decisional power and are able to benefit more from the division of labor, are the most likely to increase their probability of exporting due to their supply-chain participation. This hypothesis is consistent with the results reported in Column 5, where we restrict the analysis to the subgroup of own-branded and final firms. While all the other coefficients are in line with previous estimates, the numerical value of the supply-chain coefficient increases, thus supporting our priors. In Columns 6 and 7, we confine out attention exclusively to small firms, which represent the vast majority of the own-branded/final group (69 %). Results hold even when we exclude larger firms.

3.4 Robustness checks

The econometric analysis suggests that belonging to a supply chain is positively correlated with the probability of exporting. We performed different robustness checks.Footnote 23 First, as already mentioned, the results are confirmed when the regressions are run on the whole survey sample.Footnote 24 Second, our baseline model yields similar results when run on manufacturing and services separately.Footnote 25 Third, results are consistent even if we replace our supply-chain variable with an alternative variable constructed by taking the I/O relations of firms into account, as discussed in Sect. 2.

In this section, we report, as an additional robustness check, the results obtained with a different, nonparametric, methodology, i.e., the propensity score matching (PSM). Note that, even though PSM is often used to address causality issues, in our case not much can be said on the direction of causality, at least from a statistical point of view, particularly due to the cross-sectional limitation of the data. This has to do with the issue of self-selection: For instance, if firms with an ex-ante higher probability of exporting also choose to produce within a supply chain, then the observed correlation might over-estimate the causal effect of the supply chain. Such a problem is difficult to overcome, without panel data and/or valid instruments. However, matching procedures may be employed to validate regression results. Despite being subject to a number of criticisms, mainly related to the difficulty of selecting the control group, PSM has two main advantages: First, matching, under the common support condition, focuses on comparable subjects only; second, it is a nonparametric technique, and this avoids the potential mis-specification of the conditional mean.

We match firms with similar observable characteristics, with the exception of their participation in supply chains, by performing a PSM estimator. Since the two matched groups are comparable (and, in particular, they have the same predicted probability of participating in a supply chain), the second group acts as a counterfactual, allowing us to obtain reasonable estimates on the relation between supply-chain participation and the probability of exporting.

Formally, our parameter of interest is the “average treatment effect on the treated” (ATT), which represents an estimate of the difference in the average probability of exporting for firms belonging to a supply chain, had they not been part of the supply chain (the counterfactual). The ATT is defined as follows:

where D = {0,1} is the treatment (the supply chain), and Y(D) is the potential outcome (the probability of exporting). Since the counterfactual E[Y(0)|D = 1] cannot be observed, a control group is selected through the matching procedure, so that it can reasonably mimic treated units had they not be treated. In particular, the propensity score matching estimator can be written as follows:

where P(X) is the propensity score, which is the probability of receiving the treatment.Footnote 26

Heckman et al. (1998) show that, in observational studies, it is desirable (1) that the same questionnaire is submitted to the treated and the control group and (2) that the two groups can be extracted from the same local market. Our dataset allows us to satisfy both these requirements.

It should be noted that the matching procedure may not guarantee, nor allow testing, that the so-called unconfoundedness assumption holds, which is the requirement that the treatment is/be exogenous or independent from the potential outcomes (Imbens and Wooldridge 2009; Becker and Caliendo 2007). This is typically a problem with non-experimental data, where unconfoundedness might not hold precisely for the same reason that regression results might not capture the true causal effect. In our case, the choice of participating in a supply chain may be endogenous. Indeed, two otherwise identical firms may take different decisions about integration into a supply chain, if the decision depends on some unobserved factors. Importantly, however, it can be shown that, if such unobserved factors are unrelated to the probability of exporting, or, more generally, to access the foreign market, then the unconfoundedness assumption may not be violated (Imbens and Wooldridge 2009; Becker and Caliendo 2007).

Confining attention to small firms, we report estimates of the average treatment effects for different propensity score matching specifications. We start from a basic specification including only sectoral and regional dummies and then turn to more complete specifications, including different sets of covariates. We estimate five different models. For all the models, the matching procedures use the common support condition, and the balancing property of the propensity scores is satisfied both according to the stratification t test procedure and the standardized percentage bias, aggregate tests are reported in the Appendix, Table 12. The ATT is estimated with the nearest neighbor matching both according to the Becker and Ichino (2002) and the Leuven and Sianesi (2003) algorithms, with the same results.Footnote 27 The estimated ATT indicates that small firms belonging to a supply chain are at least 7 % points more likely to export on average (Table 7). These numbers are largely consistent with the marginal effects from the previous regression analysis (where the range was between 6.2 and 7.7 % points, Model 5 in Table 4). Thus, the propensity score matching analysis seems to reinforce our results.

4 Conclusion

The recent literature on supply chains has emphasized the importance of international fragmentation of production and specialization in functions better fitting the specific capacities of firms, focusing on firms already operating at a global level (Grossman and Rossi-Hansberg 2008; Humphrey and Schmitz 2002; Gereffi 1999). The existing literature on heterogeneous firms has highlighted different self-selection mechanisms in international markets (Melitz 2003; Bernard et al. 2007; Melitz and Redding 2014). Larger and more productive firms are more likely to access the foreign market. Smaller and less productive firms are more likely to choose disintegrated production structures, either domestically or globally. In this paper, we build on these strands of the literature and study the relation between the participation of firms to supply chains and their internationalization, with a specific focus on Italian small enterprises. The main findings can be summarized as follows: (1) In line with the existing literature on heterogeneous firms, small firms are less likely to export than larger ones; (2) small firms participating in a supply chain are more likely to export than small firms outside the supply chain; (3) they also tend to export a higher share of their turnover, while there is no evidence that they also reach a higher number of markets; (4) the position of the firm along the supply-chain matters and so does the scope for specialization; in particular, downstream firms, such as final-good producers, and firms with own-designed proprietary products are likely to gain more from participating in supply chains than upstream firms or subcontractors.

Our results are robust to different specifications and estimation methods, including nonparametric techniques, suggesting that firms in supply chains, especially smaller ones, are, on average, more likely to export, ceteris paribus (with a range that varies between 6.2 and 7.7 % points for small firms). While the size and productivity of a firm are the key determinants of its internationalization, supply-chain participation may help smaller and less productive firms to offset their structural weaknesses and to internationalize. This paper contributes to a better understanding of the mechanisms through which this occurs, at the same time justifying the co-existence of firms which are internationalized or domestic and/or with different productivity levels and organizational forms in the Italian economy.

Our results have some relevant implications. In our framework, supply chains facilitate trade and international integration of smaller firms. This, in turn, enhances the possibilities for countries characterized by a large share of small firms, such as Italy, to access new types of production and to specialize further in the specific “tasks” in line with their (firm level) comparative advantage. In other words, supply chains play an increasingly important role in fostering competitiveness and determining how countries can gain from specialization and international trade. Hence, policies designed to support firms, especially smaller ones, in actively participating in and upgrading supply chains represent an important tool to increase the gains of globalization.

Notes

In accordance with the official EU definition, in the rest of the paper, small enterprises are denoted as those with less than 50 employees.

By “relationship specific,” we mean that the value of the assets or investments is higher inside a particular relationship than outside of it.

An interesting example can be found in the value chain certification of the famous Italian brand “Gucci,” which has certified its suppliers and subcontractors. The certification involves over 600 firms from Tuscany. As a consequence, these firms, improving their reputation, have also increased their access to credit (Il Sole 24 ore online, “Intesa San Paolo e Gucci alleate per favorire l'accesso al credito delle PMI,” January 17, 2013).

The sample reduction is mainly due to microfirms and small firms for which balance-sheet data are unavailable or inconsistent across the two data sources (2-digit sector and/or region do not match). After the merge, the share of firms below 50 employee decreases to 75.3 from 86.2 %. Moreover, we lose a large number of firms in services: The share of manufacturing increases to almost two-thirds after the merge from about one-half before the merge.

The involvement in a specific production process is identified in the survey with a firm’s identification with a specific supply chain, which is different from the sector they belong to.

The aspect of participation in the final product has been added for consistency with our definition, given that it is likely to signal the “contribution of the firm to specific forms of production.”

The use of the alternative proxy for supply chain participation is also discussed when we introduce the robustness checks in Sect. 3.4, and detailed results are provided in Appendix B (Electronic Supplementary Material), and Tables B3 and B4.

The TFP estimation is based upon the Solow residuals from an econometric specification derived from a Cobb–Douglas production function. We estimated the TFP at the sectoral level, using the Levinshon and Petrin (2003) methodology, with intermediate inputs as proxies for unobservable productivity shocks. Further details on the estimation methods are provided in the “Appendix”.

Pieri and Zaninotto (2013), in a study on the Italian machinery tool industry, find that: “the most efficient builders of MTs choose integrated structures, while less efficient firms choose to outsource part of their production process by buying intermediate inputs from other firms.” (p. 413).

The construction of this variable is based upon the answer to a specific question of the survey, in which a firm is asked whether it has been involved in international activities over the past 3 years. Direct and indirect exports have been considered for the purpose of this analysis. This choice is consistent with the consideration that firms along the supply chain, upstream or downstream, have different degrees of proximity to the final market.

For consistency, the network variables that we include in the regressions are mutually exclusive. Hence, while some firms are involved in different types of networks simultaneously (e.g., local and domestic, domestic and global, or local and global), our definitions are such that each firm is univocally attributed to the wider type of network.

The matrix of correlations is available in Appendix B, Table B1, showing no concerns of collinearity between our variables.

Results are robust to the inclusion of each regressor separately and consistent also/even when the model is estimated on the whole sample of 25,090 firms (i.e., not merged with balance-sheet data). As a robustness check, all the estimations presented in the paper have been performed also on the whole sample of 25,090 firms (without checking for the TFP and FDIs). For space reasons, results are available in Appendix B, Tables B6–B8.

Replacing the SEs dummy with the logarithm of the number of employees produces similar results, with the coefficient of the latter being positive. Regressions with the SEs dummy, however, are more consistent with the following analysis, in which we split the sample between SEs and MLEs.

Note that using the initial productivity level and the change in productivity helps also to avoid concerns over a possible simultaneity bias with the dependent variables. Moreover, there is general consensus among trade economists that the direction of causality mainly goes from productivity to export, via self-selection effects à la Melitz (2003).

Average marginal effect and marginal effect at the mean, respectively.

The prediction is considered to be correct if the predicted probability is >50 % and the firm is indeed exporting or if the predicted probability is below 50 % and the firm is not exporting (Hosmer and Lemeshow 2000).

The full set of results for six different regressions for small firms (up to 50 employees) and six for larger firms (from 50 employees) are reported in Tables 10 and 11 in the Appendix. For simplicity, we report regressions up to 50 employees for SEs and over 50 employees for large firms. Above 50 employees, the two sets of regressions produce very similar results. Regressions for all the different thresholds are available from the authors.

The negative and significant effect found for firms with at least 300 employees (Column 6, Table 11) should be taken with caution, since in this subgroup most firms are already exporting (62 %), the number of observations is rather small, and the confidence interval is quite large.

Detailed results from the regressions with the interaction term, not reported here for reasons of space, are available in Appendix B, Table B2. In addition, we also run separate regressions for firms in a supply chain. For this subsample, the initial level of TFP is expected to show a lower correlation with the probability of exporting, and, indeed, the coefficients from the regressions are found to be lower and non-significant. However, the number of observations is rather small, making the introduction of an interaction term more appropriate.

The extensive margin index goes from 0 (non-exporters) to 8. The different destinations for which we have data are as follows: EU, EXTRA-EU, North America, China, India, rest of Asia, South America, other.

In our case, the definition of binary variables is preferable to the use of the actual shares of total sales. In fact, the latter is likely to contain measurement errors, i.e., the observed shares are only indicative and extreme values are indeed prevalent in the sample.

The results of these robustness checks, not included here for reasons of space, are available in Appendix B, Tables B3–B8.

To run regressions on the whole sample, however, we cannot control for TFP.

Though service firms are likely to take advantage from supply chain participation, in our sample, they are less represented both in absolute terms (they are one third of the merged sample) and especially as far as supply chain involvement is concerned (only <17.7 % of firms in a supply chain operate in services, and <7.3 % of firms in services report to be part of a supply chain). Finally, most of the services firms in our sample are localized (i.e., not easily exportable) services, including business services and transportation.

The propensity score matching models and the ATTs estimations have been performed also on the whole survey as a robustness check. Estimated ATTs are similar (slightly higher) to those reported in the paper, but the matching procedure was more problematic. Details are available in Appendix B, Tables B9, and B10.

References

Accetturo A., Giunta A., & Rossi S. (2011). The Italian firms between crisis and the new globalization. Questioni di Economia e Finanza (Occasional Papers) 86, Bank of Italy, Economic Research and International Relations Area. doi:10.2139/ssrn.1849865.

Agostino, M., Nugent, J. B., Scalera, D., Trivieri, F., & Giunta, A. (2014). The importance of being a capable supplier: Italian industrial firms in global value chains. International Small Business Journal,. doi:10.1177/0266242613518358.

Ai, C. R., & Norton, E. C. (2003). Interaction terms in logit and probit models. Economics Letters, 80(1), 123–129. doi:10.1016/s0165-1765(03)00032-6.

Antràs, P. (2003). Firms, contracts, and trade structure. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 118, 1375–1418. doi:10.1162/003355303322552829.

Antràs, P., & Chor, D. (2013). Organizing the global value chain. Econometrica, 81(6), 2127–2204. doi:10.3982/ECTA10813.

Antràs, P., Chor, D., Fally, T., & Hillberry, R. (2013). Measuring the upstreamness of production and trade flows. American Economic Review, 102(3), 412–416. doi:10.1257/aer.102.3.412.

Antràs, P., & Helpman, E. (2004). Global sourcing. Journal of Political Economy, 112(3), 552–580. doi:10.1086/383099.

Antràs, P., & Yeaple, S. R. (2014). Multinational firms and the structure of international trade. Handbook of International Economics, 4, 55–130. doi:10.1016/b978-0-444-54314-1.00002-1.

Atalay, E., Hortacsu, A., & Syverson, C. (2014). Vertical integration and input flows. American Economic Review,. doi:10.1257/aer.104.4.1120.

Baldwin, R., & Lopez-Gonzalez, J. (2014). Supply-chain trade: A portrait of global patterns and several testable hypotheses. The World Economy,. doi:10.1111/twec.12189.

Bartoli, F., Ferri, G., Murro, P., & Rotondi, Z. (2014). Bank support and export: Evidence from small Italian firms. Small Business Economics, 42, 245–264. doi:10.1007/s11187-013-9486-8.

Becattini G. (1990). The Marshallian industrial district as a socio-economic notion. In F. Pyke, G. Becattini, & W. Sengenberger (Eds.), Industrial district and inter-firm cooperation in Italy (pp. 37–51). International Institute for Labour Studies, Geneva. ISBN:929014467X, 9789290144670.

Becchetti, L., & Rossi, S. (2000). The positive effect of industrial district on the export performance of italian firms. Review of Industrial Organization, 16(1), 53–68. doi:10.1023/a:1007783900387.

Becker, S. O., & Caliendo, M. (2007). Sensitivity analysis for average treatment effects. Stata Journal, 7(1), 71–83.

Becker, S. O., & Ichino, A. (2002). Estimation of average treatment effects based on propensity scores. Stata Journal, 2(4), 358–377.

Bernard, A. B., Jensen, J. B., Redding, S. J., & Schott, P. K. (2007). Firms in international trade. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 21(3), 105–130. doi:10.1257/jep.21.3.105.

Bricongne, J. C., Fontagné, L., Gaulier, G., Taglioni, D., & Vicard, V. (2012). Firms and the global crisis: French exports in the turmoil. Journal of International Economics, 87(1), 134–146. doi:10.1016/j.jinteco.2011.07.002.

Brusco S., & Paba S. (1997). Per una storia dei distretti industriali italiani dal secondo dopoguerra agli anni novanta. In F. Barca (Ed.), Storia del capitalismo italiano dal dopoguerra ad oggi (pp. 265–333). Donzelli Editore Roma. ISBN:9788860364616.

Caliendo, M., & Kopeinig, S. (2008). Some practical guidance for the implementation of propensity score matching. Journal of Economic Surveys, 22(1), 31–72. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6419.2007.00527.x.

Castellani, D., Serti, F., & Tomasi, C. (2010). Firms in international trade: Importers’ and exporters’ heterogeneity in Italian manufacturing industry. The World Economy, 33(3), 424–457. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9701.2010.01262.x.

Cerrato, D., & Piva, M. (2012). The internationalization of small and medium-sized enterprises: The effect of family management, human capital and foreign ownership. Journal of Management and Governance, 16(4), 617–644. doi:10.1007/s10997-010-9166-x.

Crouch, C., Le Galès, P., Trigilia, C., & Voelzkow, H. (2001). Local production systems in Europe: Rise or demise?. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1016/s0038-0296(03)00019-0.

Dehejia, R. H., & Wahba, S. (1999). Causal effects in non-experimental studies: Reevaluating the evaluation of training programs. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 94(448), 1053–1062. doi:10.1080/01621459.1999.10473858.

del Gatto, M., Di Liberto, A., & Petraglia, C. (2011). Measuring productivity. Journal of Economic Surveys, 5, 952–1008. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6419.2009.00620.x.

Di Giacinto, V., Gomellini, M., Micucci, G., & Pagnini, M. (2014). Mapping local productivity advantages in Italy: industrial districts, cities or both? Journal of Economic Geography, 14, 365–394. doi:10.1093/jeg/lbt021.

Duranton, G., & Overman, H. G. (2008). Exploring the detailed location patterns of UK manufacturing industries using microgeographic data. Journal of Regional Science, 48(1), 213–243. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2006.0547.x.

Federico, S. (2012). Headquarter intensity and the choice between outsourcing versus integration at home or abroad. Industrial and Corporate Change, 21(6), 1337–1358. doi:10.1093/icc/dts006.

Gereffi, G. (1999). International trade and industrial upgrading in the apparel commodity chain. Journal of International Economics, 48, 37–70. doi:10.1016/s0022-1996(98)00075-0.

Gereffi, G., Humphrey, J., Kaplinsky, R., & Sturgeon, T. J. (2001). Introduction: Globalisation, value chains and development. IDS Bulletin, 32(3), 1–8. doi:10.1111/j.1759-5436.2001.mp32003001.x.

Giovannetti, G., Ricchiuti, G., & Velucchi, M. (2013). Location, internationalization and performance of firms in Italy: A multilevel approach. Applied Economics,. doi:10.1080/00036846.2012.665597.

Giunta, A., Nifo, A., & Scalera, D. (2012). Subcontracting in Italian industry: Labour division, firm growth and the north–south divide. Regional Studies, 46(8), 1067–1083. doi:10.1080/00343404.2011.552492.

Grossman, S. J., & Hart, O. D. (1986). The costs and benefits of ownership: A theory of vertical and lateral integration. Journal of Political Economy, 94, 691–719. doi:10.1086/261404.

Grossman, G. M., & Helpman, E. (1991). Innovation and growth in the global economy. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-57097-1.

Grossman, G. M., & Helpman, E. (2002). Integration versus outsourcing in industry equilibrium. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 117(1), 85–120. doi:10.1162/003355302753399454.

Grossman, G. M., & Rossi-Hansberg, E. (2008). Trading tasks: A simple theory of offshoring. American Economic Review, 98(5), 1978–1997. doi:10.1257/aer.98.5.1978.

Heckman, J. J., Ichimura, H., & Todd, P. (1998). Matching as an econometric evaluation estimator. Review of Economic Studies, 65(2), 261–294. doi:10.1111/1467-937X.00044.

Helpman, E., Melitz, M. J., & Yeaple, S. R. (2004). Export versus FDI with heterogeneous firms. American Economic Review, 94(1), 300–316. doi:10.1257/000282804322970814.

Higón, Añón D., & Driffield, N. (2011). Exporting and innovation performance: Analysis of the annual small business survey in the UK. International Small Business Journal,. doi:10.1177/0266242610369742.

Hosmer, D. W, Jr, & Lemeshow, S. (2000). Applied logistic regression (2nd ed.). New York: Wiley. doi:10.1002/0471722146.

Humphrey, J., & Schmitz, H. (2002). How does insertion in global value chains affect upgrading in industrial clusters? Regional Studies, 36(9), 1017–1027. doi:10.1080/0034340022000022198.

Imbens, G. W., & Wooldridge, J. M. (2009). Recent developments in the econometrics of program evaluation. Journal of Economic Literature, 47(1), 5–86. doi:10.1257/jel.47.1.5.

ISTAT. (2013). Report—Le microimprese in Italia, Censimento dell’industria e dei servizi. http://censimentoindustriaeservizi.istat.it

Leuven E., & Sianesi B. (2003). PSMATCH2: Stata module to perform full mahalanobis and propensity score matching, common support graphing, and covariate imbalance testing. Statistical Software Components S432001, Boston College Department of Economics, revised February 12, 2014.

Levinsohn, J., & Petrin, A. (2003). Estimating production functions using inputs to control for unobservables. Review of Economic Studies, 70, 317–341. doi:10.1111/1467-937X.00246.

Mayer, T., & Ottaviano, G. I. P. (2008). The happy few: The internationalisation of European firms. Intereconomics: Review of European Economic Policy, 43(3), 135–148. doi:10.1007/s10272-008-0247-x.

Melitz, M. J. (2003). The impact of trade on intra-industry reallocations and aggregate industry productivity. Econometrica, 71, 1695–1725. doi:10.1111/1468-0262.00467.

Melitz M. J., & Redding S. J. (2014). Heterogeneous firms and trade. Handbook of international economics (4th ed., Vol. 4, pp.1–54). Elsevier. doi:10.1016/B978-0-444-54314-1.00001-X.

Navaretti G. B., Bugamelli G., Schivardi F., Altomonte C., Horgos, D., & Maggioni D. (2011). The global operations of European firms: The second EFIGE policy report. Bruegel Bluepring Series. ISBN:978-9-078910-20-6.

Norton, E. C., Wang, H., & Ai, C. R. (2004). Computing interaction effects and standard errors in logit and probit models. Stata Journal, 4(2), 154–167.

OECD. (2008). Enhancing the role of SMEs in global value chains. OECD Publishing. doi:10.1787/9789264051034-en.

OECD. (2012). Fostering SMEs’ participation in global markets: Final report. OECD Centre for SMEs, Entrepreneurship and Local Development, Paris.

Park, A., Nayyar, G., & Low, P. (Eds.). (2013). Supply chain perspectives and issues: A literature review. World Trade Organization and Fung Global Institute. ISBN:978-92-870-3893-7.

Pieri, F., & Zaninotto, E. (2013). Vertical integration and efficiency: An application to the Italian machine tool industry. Small Business Economics, 40, 397–416. doi:10.1007/s11187-011-9367-y.

Razzolini, T., & Vannoni, D. (2011). Export premia and sub-contracting discount passive strategies and performance in domestic and foreign markets. World Economy, 34, 984–1013. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9701.2011.01329.x.

Rosenbaum, P., & Rubin, D. (1983). The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika, 70, 41–55. doi:10.1093/biomet/70.1.41.

van Beveren, I. (2012). Total factor productivity estimation: A practical review. Journal of Economic Surveys, 26(1), 98–128. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6419.2010.00631.x.

Wagner, J. (2012). International trade and firm performance: A survey of empirical studies since 2006. Review of World Economics, 148(2), 235–267. doi:10.1007/s10290-011-0116-8.

Wynarczyk, P., & Watson, R. (2005). Firm growth and supply chain partnerships: An empirical analysis of UK SME subcontractors. Small Business Economics, 24, 39–51. doi:10.1007/s11187-005-3095-0.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank two anonymous referees, Tadashi Ito and the participants to the Royal Economics Society Conference (Manchester, April 7–9, 2014); the Italian Trade Study Group Conference (November 2013); the 15th European Trade Study Group Conference (September 2013); the 10th c.Met05 Workshop (July 2013) and seminars at University of Florence, and IDE-JETRO for their comments on previous drafts of the paper. Financial support from the Regione Sardegna for the project CIREM “Analysis of competitiveness of Sardinia’s production system” is gratefully acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Appendix

Appendix

1.1 Data and variables description

The main source of information is a survey conducted by the MET (Monitoraggio Economia e Territorio s.r.l.). The survey contains information on 25,090 Italian firms for the year 2011, with some information also referring to the period 2009–2011. This sample of firms has been built using a stratification procedure by size, sector and region of the firms, to ensure representativeness at a national level. Firms in the dataset belong to different sectors of manufacturing and services and are located in all Italian regions. The information contained in the survey is mostly qualitative and ranges from employment to investments, innovation, and internationalization. To also have quantitative information (particularly for the TFP estimation), we match and merge the MET survey and the balance-sheet information from AIDA (Bureau Van Dijk) and the ICE-Reprint data (confining to the foreign direct investments information). After matching the information for each firm from the survey with the balance-sheet data and checking the consistency of a number of firm identifiers (mainly the 2-digit sector and the region), we are left with 10,459 firms for which the matching procedure has been successful. Further controls and the necessity to estimate the TFP reduce the sample size to 7,590 firms, which represent our final dataset. The main variables we employ are described in Table 8.

1.2 Total factor productivity estimation

The TFP estimation is based on the Solow residuals from an econometric specification derived from a Cobb–Douglas production function. This measure of the TFP, strictly related to the economic theory and rooted on clear assumptions, triggers a number of empirical issues, mainly due to the endogeneity of the observed data (del Gatto et al. 2011; van Beveren 2012). As a robustness check, we estimate the TFP in three different ways using a fixed-effects estimation (FE), the general method of moments (GMM), and the Levinsohn and Petrin (2003) approach (LP). Exploiting information from our merged database, we build a panel of indicators to estimate TFP on data covering the period 2007–2011. Overall, the three TFP estimates are robust and show a good degree of overlap (Table 9). In the paper, however, we only present the results based on the LP estimates, more appropriate for our analysis, since they explicitly take into account firms’ intermediate inputs.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Giovannetti, G., Marvasi, E. & Sanfilippo, M. Supply chains and the internationalization of small firms. Small Bus Econ 44, 845–865 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-014-9625-x

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-014-9625-x