Abstract

This study leverages the educational reform of 1985 as a source of exogenous variation in female education, providing insights into the effect of maternal schooling on the probability of child mortality at age one or younger and age five or younger. Utilizing data from the five waves of the KDHS conducted in 1993, 1998, 2003, 2008, and 2014, we employ a two-stage least-squares (2SLS) approach. Our findings indicate that women exposed to the 1985 policy change, on average, have approximately 1.87 more years of schooling compared to their counterparts. Moreover, each additional year of maternal schooling leads to a reduction in the likelihood of a child’s death at age one or younger and at age five or younger by 0.6 and 0.9 percentage points, respectively. These results remain robust across a spectrum of robustness checks. Furthermore, we explore various potential mechanisms elucidating the influence of maternal education on child mortality. These mechanisms include examining fertility behavior, the likelihood of maternal engagement in the labor force, maternal health-seeking behaviors for children, and maternal involvement in household decision-making.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Globally, child mortality has drastically decreased since the Millennium Development Goals (MDG) were announced in 2002. An estimated 5.30 million children met their demise before reaching the age of five in 2019, marking a notable decline from the approximately 9.92 million deaths recorded for children under five years of age in 2000 (Perin et al., 2022). This reduction can be attributed to concerted efforts across diverse platforms by numerous organizations and governments during the MDG period from 2000 to 2015, extending into the subsequent era characterized by the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG). However, the advancement achieved displays disparities both among and within countries, as highlighted by Kimani-Murage et al. (2014) and Mejía-Guevara et al. (2019). Children born in Sub-Saharan Africa confront the highest risk of early mortality globally, exemplified by an under-five mortality rate (children deceased before their fifth birthday) of 74 deaths per 1,000 live births documented in 2021. This rate is 15 times higher than the risk observed for children in Europe and Northern America and 19 times higher than the corresponding rate in Australia and New Zealand, as substantiated by UNICEF (2022). Similarly, fatalities occurring before the age of one are predominantly concentrated in Sub-Saharan Africa, particularly in East Africa, exhibiting the highest infant mortality rate (92.2 deaths per 1000 live births) when juxtaposed with figures from developed countries (8 deaths per 1000 live births) (Tesema et al., 2022).

Kenya emerges as a significant focal area of concern in the global context of child mortality. According to Abuya et al. (2011), child mortality remains a significant health challenge in Kenya. The country falls short of achieving its MDG targets for child mortality, displaying inconsistent progress in trends spanning the period from 1990 to 2015 (Daniel et al., 2021). Despite recent improvements, the under-five mortality rate in Kenya stands at 37 deaths per 1000 live births in 2021, as documented by the World Bank (2023). In the endeavor to reduce childhood mortality, Kenya exhibits a comparative lag in relation to its East African counterparts, experiencing a 52% decline in under-five mortality, as opposed to 70 and 71% for Tanzania and Uganda, respectively. This discrepancy signifies that while Tanzania and Uganda successfully meet and surpass their MDG targets, Kenya falls short of achieving its prescribed goal (Machio, 2018). Presently, the under-five mortality rate is projected to approach the 2030 SDG target of 25 deaths per 1,000 live births, based on the prevailing annual rate of reduction (Keats et al., 2018). Effectively addressing child mortality necessitates intensified efforts to attain the SDG3 targets, striving for a rate no greater than 25 under-five deaths per 1000 live births by 2030.

To advance ongoing efforts aimed at reducing childhood mortality in Kenya, it is imperative to identify factors robustly that exhibit a robust association with child mortality. Machio (2018) identifies factors contributing to the slow decline rates in child mortality in Kenya compared to its East African neighbors, attributing it to the insufficient utilization of maternal healthcare services and proposing solutions, including increasing maternal education and decreasing average distances to health facilities. Omariba et al. (2007) find that children of mothers with no education face an increased risk of death of 16% in their infant time and approximately 33% in their childhood. Using the Kenya Demographic Health Survey (KDHS) in 2014, infants whose mothers had no education were 1.4 times more likely to die in the first 28 days compared to mothers with higher education levels (Imbo et al., 2021). The aforementioned findings underscore the pivotal role of maternal education in influencing child mortality rates. Nevertheless, existing literature mainly concentrates on establishing correlations, thereby impeding the elucidation of a causal link between maternal education and their children’s health. Accordingly, our study aims to address and bridge this research gap.

Aligned with prior studies that utilize educational policy alterations to address the endogeneity issues in education (Andriano & Monden, 2019; Breierova & Duflo, 2004; Grépin & Bharadwaj, 2015; Nguyen-Phung, 2023), this study capitalizes on the educational policy shift in 1985 as a source of exogenous variation in female schooling. To examine the impact of maternal education on child health outcomes, we use two health indicators, including a child deceased at age one or younger (infant mortality) and a child deceased at age five or younger (under-five mortality). Drawing data from the five waves of the KDHS in 1993, 1998, 2003, 2008, and 2014, we apply the two-stage least-squares (2SLS). Our findings show that, on average, women exposed to the policy change in 1985 have approximately 1.87 years of schooling in comparison to their counterparts. One additional year of schooling leads to a reduction in the likelihood of a child being dead at age one or younger and at age five or younger by 0.6 and 0.9 percentage points, respectively. Our results are robust through a range of robustness checks. We also examine the possible channels explaining the impacts of maternal education on child mortality, including fertility behavior, the mother’s likelihood to engage in the labor force, the mother’s health-seeking behaviors for her children, and the mother’s involvement in decision-making in the household.

This paper makes substantial contributions to the existing literature on the intergenerational effects of women’s education on the well-being of their offspring. First, the study provides empirical insights into the causal relationship between mothers’ education and the mortality rates of their children within the Kenyan context. Second, in addressing potential endogeneity concerns and establishing a causal link, we employ the educational reform of 1985 as an instrumental variable (IV). The constructed IV is novel as it incorporates factors such as late enrollment and the grade repetition rate prevalent in Kenya. Third, the research explores the pathways through which maternal education in Kenya influences the development of children. Finally, given Kenya’s commitment to achieving the objectives outlined in SDG3, a nuanced comprehension of the significance of maternal education in fostering children’s well-being is crucial for policymakers.

The remainder of this article is as follows. The next section discusses a literature review on maternal education and their children’s health outcomes, highlighting various indicators and a brief of the 1985 policy. Next are the methods and the identification strategy. The results section presents a synthesis of the main findings. Lastly, the discussion section concludes and recommends policy implications.

2 Related literature

2.1 Conceptual framework and hypotheses

Maternal influence on the longevity and vitality of offspring is a complex and significant subject thoroughly investigated in a multitude of studies (Currie, 2009; Grossman, 2006; Strauss & Thomas, 1995). Previous research has illuminated the enduring ramifications of early-life health on later-life outcomes, underscoring the pivotal role that mothers, as the archetypal caregivers, play in sculpting these outcomes (Dewey & Begum, 2011; Martorell, 1999). The health and nutrition of children are profoundly affected by maternal actions within an environment largely shaped by maternal choices and socio-economic conditions, which decisively impacts their survival and growth (Currie, 2009; Hart et al., 2010; Papas et al., 2009; Robinson et al., 2007).

The level of maternal education stands as a formidable determinant of child health and mortality (Caldwell, 1993; Hobcraft et al., 1985; Li et al., 2020; Minh et al., 2016; Wolde et al., 2015). It has been documented that mothers who have attained higher levels of education are more likely to have offspring with superior health outcomes due to more informed decisions regarding health and nutrition (Aslam & Kingdon, 2012; De Neve & Subramanian, 2018; Ghuman et al., 2005; Glewwe, 1999; Güneş, 2015; Grytten et al., 2014; Keats, 2018; Lundborg et al., 2014; Robinson et al., 2007). This correlation is accentuated in terms of the mortality rate of children. Gakidou et al. (2010) and Le & Nguyen (2020) investigate on a global scale and in the developing countries context, respectively, and demonstrate that each additional year of maternal schooling is associated with a significant decrease in child mortality risks. Although there is only a limited number of studies on a country-wide scale, this positive impact of maternal education on reducing children’s mortality has been observed in several developing regions involving Taiwan (Chou et al., 2010), Vietnam (Nga et al., 2012; Nguyen-Phung, 2023) and Indonesia (Breierova & Duflo, 2004; Wang, 2021). Moreover, research on African nations is in lack of robust evidence. As Andriano & Monden (2019), Makate (2016), Makate & Makate (2016), and Grépin & Bharadwaj (2015) prove significant relationships in Malawi, Uganda, and Zimbabwe, while Ali & Elsayed (2018) and McCrary & Royer (2011) suggest a null result.

Grounded in the aforementioned studies, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 1: The enhancement of maternal education is inversely related to child mortality rates in Kenya.

The current empirical research on the relationship between maternal education and children’s mortality has not fully explored the potential pathways. Therefore, this study posits four channels through which maternal education influences child mortality.

The first pathway relates to maternal fertility behavior. Increased educational attainment is associated with a postponement of initial sexual activity (Black et al., 2008; Masuda & Yamauchi, 2020), deferred marriage (Ali & Gurmu, 2018; Field & Ambrus, 2008; Parsons & McCleary-Sills, 2014), and an extension of the age at first childbirth (Ali & Gurmu, 2018; Grépin & Bharadwaj, 2015). Literature affirms that children born to very young mothers or as firstborns encounter a higher risk of mortality (Hobcraft, 1993; Hobcraft et al., 1985). Moreover, there is a consistent demonstration of a reduction in fertility rates and mean birth interval correlated with the heightened educational levels of women (Ali & Gurmu, 2018; Becker et al., 2013; Grépin & Bharadwaj, 2015; Keats, 2018; Le & Nguyen, 2020; Makate & Makate, 2016; Osili & Long, 2008). As Becker & Lewis (1973) explore the interplay between the “quantity” and “quality” of children, elucidating a positive correlation between a woman’s education and the “quality” of her offspring, educational advancements indeed result in healthier childbirth practices and child-rearing environments (Currie & Moretti, 2003).

The second pathway is through labor force engagement. Maternal academic achievements translate into improved labor market opportunities, equipping women with essential skills for earning an income (Alam et al., 2011; Fasih, 2008; Goldberg & Smith, 2013; Herman, 2012; Krishnakumar & Nogales, 2020), therefore explain part of the improvement on children’s health outcome (Le & Nguyen, 2020). Women with higher educational credentials command increased earnings, which enables them to invest in child health care services. Since women are central to household consumption decisions, particularly regarding diet and nutrition, their active participation in the workforce empowers them to invest in the nutritional and developmental needs of their children (Moehling, 1995; Smith et al., 2003). Mothers with greater economic resources can procure higher-quality nutrition and provide superior care for their children, contributing to enhanced child survival rates (Amugsi et al., 2016; Smith et al., 2003). From a broader perspective, children who benefit from improved nutrition and care are likely to develop better cognitive skills and achieve more favorable labor outcomes in adulthood (Currie, 2009; Kar et al., 2008).

The third pathway is health-seeking behavior. Educational endeavors serve as a vehicle for dispelling ignorance and augmenting mothers’ capabilities in attaining a broad spectrum of information, leading to higher maternal health literacy (Duflo, 2012; Samarakoon & Parinduri, 2015; Thomas et al., 1991). This broader comprehension encompasses vital aspects of disease causation, prevention, identification, modern treatment, and a deeper understanding of nutritional needs that directly influence child mortality (Frost et al., 2005). Furthermore, education grants women access to and enhances their interpretation of health communications and advisories from varied sources, thus bolstering maternal health literacy (Ahmadi & Karamitanha, 2023; Gibbs et al., 2016; Phommachanh et al., 2021). As a result, educated women are better positioned to safeguard their children from infections through improved sanitary practices, diminish the risk of diseases through adequate nutrition, and expedite recovery from illnesses with more effective healthcare interventions (Ahmadi & Karamitanha, 2023; Andriano & Monden, 2019; Caldwell, 1979; Gibbs et al., 2016). Smoking is one of those detrimental practices that cause a higher mortality rate and is more likely to be avoided during pregnancy for women with higher educational levels (Currie & Moretti, 2003; Lindeboom et al., 2009). Moreover, women are more likely to pay more visit to prenatal care visits and deliver in health institutes so as to promise a facilitated environment for childbirth (Cleland & Van Ginneken, 1988; Grépin & Bharadwaj, 2015; Le & Nguyen, 2020; Makate & Makate, 2016; Nga et al., 2012). After the birth of infants, women with higher education levels intend to prepare babies with better immune systems through vaccination in order to fight against malnutrition and disease that lead to 10 percent of under-5 deaths (Keats, 2018; Makate & Makate, 2016).

The fourth pathway is women’s involvement in decision-making. Education bestows confidence, independence, awareness, and self-worth, which are vital for initiating changes in women’s decision-making abilities to manifest their intrinsic beliefs and surmount internal barriers (Chanana, 1996; Orenstein, 2013; Rivera-Garrido, 2022; Samarakoon & Parinduri, 2015). Women’s empowerment, especially as primary caretakers, exerts a substantial impact on child survival, allowing educated women to impose greater control over health choices for their children (Bhagowalia et al., 2012; Caldwell, 1979; Nguyen et al., 2013; Smith et al., 2003). Research conducted in Ghana indicates that women with significant autonomy in household decision-making are more likely to secure a diverse diet for their families, thereby contributing to their children’s health (Amugsi et al., 2016). This dynamic is particularly evident among women with advanced education. Women’s ability to make informed choices and procure resources as an empowerment dimension has a considerable correlation with the availability of a nutritious diet at home, which is a key factor in reducing child mortality (Aslam & Kingdon, 2012; Larsson & Stanfors, 2014; Nguyen-Phung & Nthenya, 2023). Consequently, educational attainments that confer bargaining power empower females to make informed household decisions, ultimately contributing to the enhancement of childbirth quality.

Accordingly, the formulated second hypothesis is:

Hypothesis 2. Maternal education’s impact on child mortality in Kenya is facilitated through shifts in fertility behavior, labor market engagement, increased informational access, and women’s involvement in household decision-making.

2.2 The 1985 education reform

Kenya’s educational architecture, prior to the reform of 1985, included a sequential framework of seven years of primary education, followed by secondary and higher education, culminating in graduation. In response to critiques from the private sector about the education system’s academic focus being disconnected from the labor market and development needs, the Kenyan government reformed its education policy in 1985, adding an extra year to primary schooling (Eshiwani, 1990; Wanjohi, 2011).Footnote 1 Maintaining the cumulative 16-year educational span, this policy shift modified the structure from 7 + 4 + 2 + 3 to 8 + 4 + 4 as depicted in Fig. 1, resulting in a significant rise in primary school enrollment and retention, particularly enhancing educational attainment for girls (Somerset, 2007). Consequently, seventh-grade students in 1985 progressed to an additional primary grade instead of advancing to secondary school. All students who were enrolled in a lower Grade than Grade 7 would attain an extra year of primary education compared with the older cohort who had already completed primary education at the time of reform. The reform also integrated practical skills such as arts and crafts into the curriculum, aiming to inculcate vocational skills at the primary level (Somerset, 2009). This period also saw prevalent late enrollments and grade repetitions across Africa, with Kenya experiencing similar trends, leading to older students or extended durations for completing primary education.

The reform had an extensive impact on those commencing primary education in 1979 or thereafter or individuals under 14 years of age in 1985 (i.e., those born after 1971). It partially affected women born between 1965 and 1971, with no discernible impact on those born between 1950 and 1964. The forthcoming sections provide an in-depth exploration of the reform’s influence on child mortality, with a particular focus on the role of improved maternal education.

3 Research data

3.1 Data sources

We utilize data from five waves of the KDHS conducted in 1993, 1998, 2003, 2008, and 2014. The surveys employ a two-step implementation process. Initially, enumeration areas are derived from the population census, followed by the selection of households within these chosen areas. To ensure national representativeness, we adjust the survey weights. The survey encompasses comprehensive information, including details about women’s backgrounds and their children’s mortality.

Furthermore, our study investigates the likelihood of a student advancing to secondary school before the introduction of the educational policy, utilizing data from two distinct sources. First, to accommodate repetition rates and Grade One enrollment age, we incorporate information from Somerset (2007). Second, for an evaluation of the transition from primary to secondary school levels, we extract progression rates from Ohba (2009).

3.2 Variable definitions

To examine the influence of maternal education on child mortality rates, we utilize the number of years of schooling completed during adulthood as the primary indicator of female education. Our study incorporates additional education-related measures, and we conduct robustness checks to ensure the reliability of our findings. The subset of data used in this analysis is drawn from individual records of women born between 1950 and 1980, ensuring that their educational choices have been finalized.

Child mortality rate metrics are derived from birth records consisting of information about the child’s gender, birth details, and age at death. We employ two binary measures of child mortality rates, specifically death at age one or younger and death at age five or younger. First, we create a dummy indicator representing death at age one or younger, assigning 1 if the child died within the first year of life and 0 otherwise. Second, we establish a binary indicator for death at age five or younger, where 1 represents the child’s death before or at five years old and 0 otherwise.

Table 1 provides a comprehensive overview of descriptive statistics. In Panel A, we present the mean and standard deviation of the outcomes. On average, women complete approximately 6.8 years of schooling. The percentages of children who have deceased at age one or younger and at age five or younger are 6.5 and 7.2%, respectively. Moving to Panel B, we present the mean and standard deviation of control variables. Nearly half (49%) of the children are female, and 19.1% reside in urban areas. The ethnic distribution reveals that approximately 71.6% of groups belong to Kalenjin, Kamba, Kikuyu, Luhya, and Luo. Geographically, 72.7% of children are located in the Eastern, Nyanza, Rift Valley, and Western regions.

4 Research methodology

4.1 Probability of belonging to an educational cohort

It is well-documented that grade repetition and late entry in Kenya are extensively prevalent (Somerset, 2009), influencing diverse birth cohorts through educational policy. Therefore, the cohort years can be categorized into three different groups: the fully treated group, comprising cohorts exposed to the new educational system; the partially treated group, encompassing cohorts potentially affected by policy change owing to grade repetition and delayed entry; and the control group, representing cohorts whose ages exceeded 20 years, thereby casting doubt on their susceptibility to the reform’s impact. In response to the challenge associated with the partially treated group, certain academic investigations choose to completely omit this cohort from their analysis (Agüero & Bharadwaj, 2014; Makate & Makate, 2016). Nonetheless, this method results in a considerable reduction in the quantity of observations and has the potential to generate an upward bias in the estimated outcomes. Other researchers, on the other hand, use a binary allocation of 0 or 1, failing to take into consideration the noteworthy obstacles posed by delayed enrollment and grade competition (Ferré, 2009). Rather than designating a binary for our cohorts or eliminating the partially treated group, we utilize the data from Somerset (2007) and Ohba (2009) to apply percentages of repetition and advancement to lower secondary education and derive a probability distribution where each birth cohort is assigned to education cohorts via a probabilistic treatment assignment.Footnote 2

In a more detailed breakdown, our sample is categorized into three different groups based on birth years, each of which is ascribed to a corresponding probability. The fully treated group, comprising female respondents born between 1972 and 1980, is designated a probability of 1. Women born between 1965 and 1971 fall into the partially treated group, and a probability between 0 and 1 is assigned to each individual within this category.Footnote 3 As for the control group, a probability of 0 is allocated to women respondents born between 1950 and 1964.

In this context, b symbolizes the birth cohort, \(Pr\) denotes the probability, and \({pr\_}{{iv}}_{b}\) signifies the probability assigned to a female respondent being affiliated with the designated birth cohort b.

4.2 Identification strategy

We present the following econometric model to examine the influence of maternal education on their child’s mortality rates:

where \({{mortality}}_{{ib}}\), \({{maternal\_educ}}_{{ib}}\), and \({{\boldsymbol{X}}}_{{\boldsymbol{ib}}}\) denote the mortality rates for a child i from birth cohort b, maternal education, and a set of control variables, respectively. In this study, we control for the gender of the child, the mother’s ethnicity, the age of the mother, the status of the rural residents, and regional areas. \({\alpha }_{0}\), \({\alpha }_{1}\), and \({{\boldsymbol{\alpha }}}_{{\boldsymbol{2}}}\) are associated parameters and \({\varepsilon }_{{ib}}\) is the error term.

To alleviate the potential endogeneity issues inherent in the aforementioned ordinary least square (OLS) regression, we employ the instrumental variable (IV) regression. To be more specific, we utilize the previously derived probability of exposure to the policy (\({pr\_}{{iv}}_{b}\)) as an IV. The rationale for employing \({pr\_}{{iv}}_{b}\) as the IV is explicated as follows: Initially, confined to the designated range of ages, it is evident that the influence of educational reform on a child’s mortality rates is anticipated to be mediated exclusively through its effect on their mother’s education. It is crucial to maintain this exclusion restriction, considering that the implementation of the policy does not explicitly target child mortality rates. While there is a potential for the violation of this assumption due to the direct influence of other environmental or policy shifts, women within the specified age range remain unaffected by these alterations.Footnote 4 Second, our IV exhibits a robust association with maternal education. Specifically, the relevance of the IV is scrutinized in Table 3, signifying the absence of weakness in our chosen IV.

We use the two-stage least-squares (2SLS) approach to investigate the influence of maternal education on their child’s mortality rates. In the first stage, we regress maternal education on our IV and other covariates:

where f symbolizes the first stage, \({\alpha }_{f0}\) \({\alpha }_{f1}\), and \({{\boldsymbol{\alpha }}}_{{\boldsymbol{f}}{\boldsymbol{2}}}\) are parameters, and \({\varepsilon }_{{fib}}\) is an error term. Next, we regress the child’s mortality rates on the estimated value of maternal education and other covariates:

where \(s\) signifies the second stage, \({\alpha }_{s0}\), \({\alpha }_{s1}\), and \({{\boldsymbol{\alpha }}}_{{\boldsymbol{s}}{\boldsymbol{2}}}\) are parameters, and \({\varepsilon }_{{sib}}\) is an error term.

5 Empirical results

5.1 Two-stage least-squared estimations

5.1.1 The impact of educational policy on female education

Table 2 presents the results of the first-stage estimation. Specifically, women exposed to the educational reform have, on average, approximately 1.87 more years of formal education compared to their counterparts.

The impact of educational reforms on female schooling is evident, in contrast to the statistically insignificant effects observed in the context of exposure to fictional policies. To conduct this comparison, we examine the educational achievements of individuals exposed to the fictional policy versus those unexposed, categorized by women’s years of birth. Specifically, the fictional policy implementations occurred in 1951, 1957, 1977, and 1982, aligning with the corresponding birth years of women (1948–1953), (1954–1959), (1974–1979), and (1979–1984), respectively. The estimated coefficients, presented in Table 3, indicate no significant effects of fictional reforms on female schooling. Consequently, these findings affirm the conclusion that the educational policy has an insignificant impact on the educational attainment of unexposed cohorts.

5.1.2 The impact of maternal schooling on their child mortality rates

The main findings derived from the 2SLS estimation are presented in Table 4.Footnote 5 Leveraging the predicted values in the first stage regression, we assess the causal impacts of maternal education on two mortality indicators. To elaborate, each additional year of female education results in a decrease of 0.6 percentage points in the probability of a child’s death at age one or younger and a reduction of 0.9 percentage points in the likelihood of a child’s death at age five or younger.Footnote 6

We perform an array of robustness checks on the main findings presented in Table 4. First, we revisit the main results using two alternative measures of female education, ensuring the findings remain unaffected by variations in variable definitions or the functional form of the estimation model. The first measure represents the probability of completing at least 8 years of schooling, while the second measure involves the natural logarithm of female schooling. The outcomes of this re-estimation are detailed in Table 5. In Panel A, mothers with an education attainment of at least 8 years diminish the likelihood of their child being deceased at age one or younger and at age five and younger by 4.2 and 5.9 percentage points, respectively. Moving to Panel B, a one-percent increase in maternal schooling results in a reduced probability of her child being deceased at age one or younger and at age five and younger by 4.2 and 5.3 percentage points, respectively. These results consistently reinforce our main findings in Table 4.

Second, in response to widespread challenges associated with late enrollment and repetition rates, prior research typically eliminates the partially treated group and undertakes the analysis using exclusively the fully treated and untreated samples (Grépin & Bharadwaj, 2015; Masuda & Yamauchi, 2020). Adhering to this methodological approach, we replicate our primary findings by excluding the partially treated group, and the estimated results are detailed in Table 6. Notably, a persistent trend is evident, demonstrating a consistently negative and statistically significant influence of maternal education on child mortality rates.

Third, as previously stated in Section 4.1, we initially employed a probability scale ranging from 0 to 1 for the partially treated group to mitigate the prevalent challenges associated with late enrollment and repetition rates in Kenya. However, in our revised methodology, we no longer consider this issue. Instead, we categorize women exposed to the educational system changes with a value of 1, while those unexposed receive a value of 0. The findings are detailed in Table 7. We consistently observe negative and statistically significant impacts of maternal education on two measures of child mortality, specifically, the probability of their child’s death before reaching the age of one or younger, and before reaching the age of five.

Moreover, when computing the original IV, we utilize the pre-reform information percentages of repetition and advancement to lower secondary education from Somerset (2007) and Ohba (2009). We now employ the fraction of individuals who completed at least 8 years of schooling from the Kenya Census 1999 — which is post-reform information — as our alternative IV. As a robustness check, we employ the same information from the Kenya Census 2009. The results are outlined in Table 8 and are similar to those in the main findings.

In addition, to address cohort heterogeneity, we incorporate data on gender attitudes from World Values Survey Wave 6 into our main analyses.Footnote 7 We utilize responses to the question, “Is a university education more essential for boys than for girls?” as a measure of gender attitude, where a value of 1 signifies disagreement with the statement and 0 otherwise. The outcomes are detailed in Table 9 and align with main findings.

Furthermore, our analysis integrates the control function approach and utilizes the bi-probit and iv-probit techniques to obtain our findings. In the control function approach, following the methodology of Rivers & Vuong (1988), we conduct an OLS regression in the first stage estimation, where female education is regressed on our instrument and explanatory variables. Subsequently, we calculate residuals and apply a probit model to regress child mortality indicators. This model incorporates maternal education, the residuals, and explanatory variables. In the alternative approach, we employ the bi-probit and iv-probit methods to handle the binary measures of child mortality rates. The outcomes of these analyses are detailed in Table 10. Our results consistently highlight a negative impact of maternal education on the likelihood of a child being deceased at age one or younger and at age five or younger.

Finally, the crucial condition of meeting the exclusion restriction, a prerequisite for instrumental variables, is susceptible to violations in the presence of other factors influencing children’s mortality rates. To address the endogeneity challenge, we apply Lewbel’s (2012) 2SLS approach, a widely employed methodology in empirical studies for assessing the robustness of outcomes using external instruments (Chatterji et al., 2014; Ma, 2019; Tranchant et al., 2020; Wang & Cheng, 2022). This method relies on heteroskedastic covariance restrictions to create internal instrumental variables, thereby mitigating the need to strictly adhere to the exclusion restriction.

The results derived from Lewbel’s (2012) approach are outlined in Table 11. We present two sets of Lewbel 2SLS results. The first exclusively relies on internal instruments, while the second integrates the probability of exposure to the policy change with internally generated instruments. These results further reinforce our main findings that maternal education has adverse effects on the likelihood of children being deceased at age one or younger and at age five or younger in Kenya.

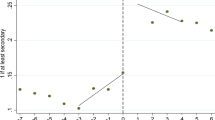

5.2 Plausibly exogenous IV

Even though our IV, signifying the probability of exposure to the policy (\({pr}{{\_iv}}_{b}\)), displays a noteworthy association with our main variable (\({{maternal\_educ}}_{{ib}}\)), the ability to rigorously test the exclusion restriction is hindered by the intrinsic unobservability of the error term. To alleviate this challenge, we adopt the methodological framework known as the union of all confidence intervals (UCI), as originally introduced by Conley et al. (2012). This strategy is applied to assess our key results, considering a relaxation of the exclusion restriction.Footnote 8 In the traditional IV regression, it is posited that the influence of the IV on the dependent variable is exclusively mediated through the main variable, as indicated by \(\delta =0\) in Eq. 4b provided below:

Nonetheless, if the IV (\({pr\_}{{iv}}_{b}\)) is considered plausibly exogenous (\(\delta \approx 0\)), it suggests a potential, albeit marginal, direct association between the IV and \({{mortality}}_{{ib}}\). Specifically, we allow the direct impact of \({pr\_}{{iv}}_{b}\) on \({{mortality}}_{{ib}}\) (\(\delta\)) to vary within a predefined interval, thereby constructing a credible range of potential values (β) for the influence of \({{maternal\_educ}}_{{ib}}\) on \({{mortality}}_{{ib}}\).

Figure 2 displays the estimated effects of maternal education on child mortality rates (dead at age one or younger) when the IV, the probability of exposure to the policy, is plausibly exogenous. The solid blue and dashed green lines indicate the lower and upper bounds of the 95% confidence interval for maternal education, respectively. In general, the 2SLS estimates regarding the effects of maternal education on the likelihood of a child’s death at age one or younger fall within the 95% confidence intervals computed for different values of \(\delta\).

Plausibly exogenous IV: The impacts of maternal education on child mortality rate (dead at age one or younger) using the UCI approach of Conley et al. (2012)

More precisely, if \(\delta\) assumes a positive value, the 95% confidence interval for maternal education coefficient (\(\beta\)) does not include 0. This implies that maternal education has a negative and statistically significant impact on child mortality rates when a greater probability of exposure to the policy (IV) is correlated with elevated child mortality rates. It is worth noting that the 95% confidence interval for \(\beta\) exclusively includes 0 when \(\delta\) is less than −0.004. It is noteworthy that the reduced-form estimate indicates an approximate impact of −0.014 on a child’s death at age one or younger as a result of exposure to the policy.Footnote 9 Therefore, the selected threshold of −0.004, which encapsulates roughly 30% of the total direct influence of IV on the likelihood of a child’s death at age one or younger, is considered suitable.Footnote 10 To conclude, our results consistently affirm the existence of a negative and statistically significant influence of maternal education on the probabilities of a child’s death at age one or younger, even when accommodating a substantial deviation from the assumption of perfect exogeneity.Footnote 11

5.3 Potential pathways

Table 12 investigates the underlying paths contributing to the nexus between female education and their children’s mortality rates. The first pathway involves fertility. As indicated in Panel A of Table 12, a one-year increase in female schooling extends the age at first marriage by 0.5 years and age at first intercourse by 0.4 years, similar to Grépin & Bharadwaj’s (2015) results for Zimbabwe, which are approximately 0.52 and 0.63 years, respectively. The timing of the first birth is increased by 0.3 years, consistent with Le & Nguyen’s (2020) results of 0.11 years in 68 developing countries across five continents. Additionally, an extra year of schooling reduces the number of children ever born by approximately 0.5, which is in line with Samarakoon & Parinduri’s (2015) result of around 0.3 live births. The second pathway focuses on labor market engagement. The results in Panel B reveal that an additional year of education increases the likelihood of having a job and working in the last 12 months by 5.8 and 5.2 percentage points, respectively, consistent with the findings of Le & Nguyen (2020) and Aslam & Kingdon (2012). The third pathway involves the mother’s health-seeking behaviors for her children. Results in Panel C demonstrate that a one-year increase in female schooling decreases the mother’s likelihood of smoking by 2.8 percentage points and improves her chances of birth delivery in a hospital and vaccinating her child by 4.6 and 3.2 percentage points, respectively, consistent with Makate & Makate’s (2016) finding of a 52.5 percentage point improvement in prenatal care visits and Grépin & Bharadwaj’s (2015) result of a 5.3 percentage point increase in cesarean section deliveries. The last pathway is associated with women’s involvement in decision-making. We measure her decision-making in the household via five binary indicators, with 1 indicating that she is involved in the decision-making process and 0 otherwise. Panel D results show that an extra year of female schooling enhances her decision-making in health, large purchases, daily purchases, family visits, and food purchases by approximately 12.5, 18.3, 14.4, 9.1, and 5 percentage points, respectively, consistent with previous studies (Amugsi et al., 2016; Bhagowalia et al., 2012; Keats, 2018; Nguyen et al., 2013; Smith et al., 2003).

6 Conclusions and policy recommendations

This paper investigates the impacts of maternal education on her children’s mortality rates in Kenya. Utilizing five waves of nationally representative data from KDHS, we explore how a mother’s education influences her offspring’s health and development. This impact is not only supported by the MDG and SDG frameworks but also substantiated by extant literature (Grytten et al., 2014; Lundborg et al., 2014; Robinson et al., 2007; Nguyen-Phung, 2023). Education, particularly the educational obtainments of mothers, emerges as a critical determinant in enhancing the well-being of children. This impact aligns with the broader global agenda, notably SDG3, which aspires to ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at every stage of life. Recognizing the pivotal role that maternal education plays in achieving these ambitious goals, our research seeks to contribute crucial perspectives to the ongoing discourse on improving child health outcomes in Kenya.

We utilize the educational reform of 1985 as a source of exogenous variation in female education, providing insights into the impact of maternal schooling on the probability of child mortality at age one or younger and age five or younger. Drawing data from the five waves of the KDHS conducted in 1993, 1998, 2003, 2008, and 2014, we apply a two-stage least-squares (2SLS) approach. Our findings illustrate that women exposed to the 1985 policy change, on average, have approximately 1.87 more years of schooling than their counterparts. Moreover, an additional year of maternal schooling results in a reduction in the likelihood of a child’s death at age one or younger and age five or younger by 0.6 and 0.9 percentage points, respectively. These results remain robust across a series of robustness checks. Additionally, we explore various potential mechanisms elucidating the impact of maternal education on child mortality. These mechanisms include examining fertility behavior, the likelihood of maternal engagement in the labor force, maternal health-seeking behaviors for children and maternal involvement in household decision-making.

Our findings are in line with previous studies which signify that education is a key factor through which women can reduce the mortality rate of their children (Andriano & Monden, 2019; Breierova & Duflo, 2004; Gakidou et al., 2010; Grépin & Bharadwaj, 2015; Le & Nguyen, 2020; Makate, 2016; Makate & Makate, 2016; Nguyen-Phung, 2023). We further confirm the mechanisms through which maternal education influences various aspects of her life, including fertility behavior (Le & Nguyen, 2020; Samarakoon & Parinduri, 2015), labor participation (Le & Nguyen, 2020; Aslam & Kingdon, 2012), health-seeking behaviors for children (Andriano & Monden, 2019; Grépin & Bharadwaj, 2015; Makate & Makate, 2016; Makate & Makate, 2016), and involvement in decision-making (Amugsi et al., 2016; Bhagowalia et al., 2012; Keats, 2018; Nguyen et al., 2013; Smith et al., 2003), leading to an improvement in their children’s survival rate.

Our findings have crucial policy implications. First, considering the intergenerational effects of maternal education on their children’s health and development, educational system reforms or programs that give special attention to enhancing access to school or ensuring extended years of schooling for females are essential for promoting the health of the next generation. Second, awareness campaigns and accessible healthcare services should encourage maternal health-seeking behaviors, including smoking cessation, hospital deliveries, and child vaccinations, contributing to positive health practices. Finally, initiatives should be implemented to enhance maternal involvement in household decision-making, including awareness programs and policies that promote gender equality within households, ensuring that women have a voice in decisions affecting their children’s well-being.

Notes

The 1985 educational reform introduced substantial alterations in curriculum and instruction, particularly at the primary level, where the number of subjects expanded from seven to thirteen, with nine subjects evaluated in the Kenya Certificate of Primary Education (Somerset, 2009). The redesigned curriculum emphasized prevocational subjects such as art and crafts, agriculture, and home science, aiming to provide students with essential knowledge and skills pertinent to the labor market (Kim, 2020; Sifuna, 1992). This realignment was consistent with the reform’s goal of implementing the 8-4-4 system, which emphasizes a practical curriculum geared towards equipping graduates with employable skills, addressing the demand for skill-oriented education. A key change in instruction was the language used, particularly in primary education, where the reform mandated the use of the local vernacular for the first three years, transitioning to English thereafter. Moreover, under the 8-4-4 system, English and Swahili became mandatory and examinable subjects in primary schools (Piper et al., 2016), marking a departure from the previous 7-4-2-3 system where English was the primary language of instruction from the beginning (Anderson, 1965; Kim, 2020).

Note that as opposed to the binary method, wherein each cohort is definitively assigned values of 0 or 1 to denote certain exposure to the new educational reform, we alleviate this constraint by endowing each birth cohort, particularly the partially treated group, with a probability of experiencing the reform. This methodological paradigm, originally proposed by Angrist & Lavy (1999), has undergone subsequent refinement and application in recent scholarly research (Chicoine, 2012; Lindskog & Durevall, 2021; Nguyen-Phung & Nthenya, 2023).

Interested readers can refer to Appendix A for detailed computations.

It is pertinent to acknowledge that assessing the validity of this assumption directly is hindered by the inherent complexities. Therefore, its validity is scrutinized through a range of robustness checks, and the detailed findings will be presented in subsequent sections.

The results of the baseline OLS estimation are reported in Appendix B for further details.

We add the survey fixed effects in the main estimation and report the results in Panel A in Appendix Table 15. We include a squared term of age trend in this model to account for continuous changes in the outcomes over birth cohorts, capturing both linear and quadratic trends (See Panel B in Appendix Table 15). Additionally, we incorporate a control for school attendance from the Kenya Census 1999 (See Panel C in Appendix Table 15). The estimated results from these exercises corroborate our key findings.

We also include gender attitude in the model using the new instrumental variable, where 1 is assigned for the treated, and 0 otherwise. Additionally, we incorporate this control for another instrumental variable that utilizes post-reform information from the Kenya Census 1999 and 2009. The results remain robust (See Appendix Table 16).

Interested readers can refer to Table 17 of Appendix C for further details.

Similar results are derived for a child’s death at age five or younger. Figure 3 of Appendix D displays the result.

It is noteworthy that we do not account for the dropout rate due to a scarcity of data available within this designated timeframe.

References

Abuya, B. A., Onsomu, E. O., Kimani, J. K., & Moore, D. (2011). Influence of maternal education on child immunization and stunting in Kenya. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 15, 1389–1399. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-010-0670-z.

Agüero, J. M., & Bharadwaj, P. (2014). Do the more educated know more about health? Evidence from schooling and HIV knowledge in Zimbabwe. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 62(3), 489–517. https://doi.org/10.1086/675398.

Ahmadi, F., & Karamitanha, F. (2023). Health literacy and nutrition literacy among mother with preschool children: What factors are effective? Preventive Medicine Reports, 35, 102323. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmedr.2023.102323.

Alam, A., Baez, J. E., & Carpio, X. V. D. (2011). Does Cash for School Influence Young Women’s Behavior in the Longer Term? Evidence from Pakistan. The World Bank, Discussion Paper No. 5703. https://doi.org/10.1596/1813-9450-5669.

Ali, F. R. M., & Elsayed, M. A. (2018). The effect of parental education on child health: Quasi‐experimental evidence from a reduction in the length of primary schooling in Egypt. Health Economics, 27(4), 649–662. https://doi.org/10.1002/hec.3622.

Ali, F. R. M., & Gurmu, S. (2018). The impact of female education on fertility: A natural experiment from Egypt. Review of Economics of the Household, 16, 681–712. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-016-9357-6.

Amugsi, D. A., Lartey, A., Kimani-Murage, E., & Mberu, B. U. (2016). Women’s participation in household decision-making and higher dietary diversity: Findings from nationally representative data from Ghana. Journal of Health, Population and Nutrition, 35(1), 16. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41043-016-0053-1.

Anderson, J. E. (1965). The Kenya education commission report: An African view of educational planning. Comparative Education Review, 9(2), 201–207. https://doi.org/10.1086/445140.

Andriano, L., & Monden, C. W. S. (2019). The Causal Effect of Maternal Education on Child Mortality: Evidence From a Quasi-Experiment in Malawi and Uganda. Demography, 56(5), 1765–1790. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-019-00812-3.

Angrist, J. D., & Lavy, V. (1999). Using Maimonides’ rule to estimate the effect of class size on scholastic achievement. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 114(2), 533–575. https://doi.org/10.1162/003355399556061.

Aslam, M., & Kingdon, G. G. (2012). Parental Education and Child Health—Understanding the Pathways of Impact in Pakistan. World Development, 40(10), 2014–2032. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2012.05.007.

Azhgaliyeva, D., Le, H., Olivares, R. O., & Tian, S. (2023). Renewable Energy Investments and Feed-in Tariffs: Firm-Level Evidence from Southeast Asia. ADBI Working Paper. https://doi.org/10.56506/VRNO2480.

Becker, G. S., & Lewis, H. G. (1973). On the Interaction between the Quantity and Quality of Children. Journal of Political Economy, 81(2), S279–S288.

Becker, S. O., Cinnirella, F., & Woessmann, L. (2013). Does women’s education affect fertility? Evidence from pre-demographic transition Prussia. European Review of Economic History, 17(1), 24–44. https://doi.org/10.1093/ereh/hes017.

Bevis, L., Kim, K., & Guerena, D. (2023). Soil zinc deficiency and child stunting: Evidence from Nepal. Journal of Health Economics, 87, 102691. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2022.102691.

Bhagowalia, P., Menon, P., Quisumbing, A. R., & Soundararajan, V. (2012). What Dimensions of Women’s Empowerment Matter Most for Child Nutrition? IFPRI Discussion Paper, 01192.

Black, S. E., Devereux, P. J., & Salvanes, K. G. (2008). Staying in the Classroom and out of the maternity ward? The effect of compulsory schooling laws on teenage births. The Economic Journal, 118(530), 1025–1054. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0297.2008.02159.x.

Breierova, L., & Duflo, E. (2004). The impact of education on fertility and child mortality: Do fathers really matter less than mothers? https://doi.org/10.3386/w10513.

Caldwell, J. C. (1979). Education as a Factor in Mortality Decline An Examination of Nigerian Data. Population Studies, 33, 395–413.

Caldwell, J. C. (1993). Health transition: The cultural, social and behavioural determinants of health in the Third World. Social Science & Medicine, 36(2), 125–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(93)90204-H.

Chanana, K. (1996). Educational attainment, status production and women’s autonomy: A study of two generations of Punjabi women in New Delhi. In Girls’ Schooling, Women’s Autonomy and Fertility Change in South Asia. SAGE Publications Pvt. Ltd.

Chatterji, P., Kim, D., & Lahiri, K. (2014). Birth weight and academic achievement in childhood. Health Economics, 23(9), 1013–1035. https://doi.org/10.1002/hec.3074.

Chicoine, L. (2012). Education and fertility: Evidence from a policy change in Kenya, IZA Discussion Papers, No. 6778. Bonn: Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA). https://docs.iza.org/dp6778.pdf.

Chou, S.-Y., Liu, J.-T., Grossman, M., & Joyce, T. (2010). Parental Education and Child Health: Evidence from a Natural Experiment in Taiwan. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 2(1), 33–61. https://doi.org/10.1257/app.2.1.33.

Clarke, D., & Matta, B. (2018). Practical considerations for questionable IVs. The Stata Journal, 18(3), 663–691. https://doi.org/10.1177/1536867X1801800308.

Cleland, J. G., & Van Ginneken, J. K. (1988). Maternal education and child survival in developing countries: The search for pathways of influence. Social Science & Medicine, 27(12), 1357–1368. https://doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(88)90201-8.

Conley, T. G., Hansen, C. B., & Rossi, P. E. (2012). Plausibly exogenous. Review of Economics and Statistics, 94(1), 260–272. https://doi.org/10.1162/REST_a_00139.

Currie, J. (2009). Healthy, Wealthy, and Wise: Socioeconomic Status, Poor Health in Childhood, and Human Capital Development. Journal of Economic Literature, 47(1), 87–122. https://doi.org/10.1257/jel.47.1.87.

Currie, J., & Moretti, E. (2003). Mother’s Education and the Intergenerational Transmission of Human Capital: Evidence from College Openings. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 118(4), 1495–1532. https://doi.org/10.1162/003355303322552856.

Daniel, K., Onyango, N. O., & Sarguta, R. J. (2021). A spatial survival model for risk factors of under-five child mortality in Kenya. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(1), 399 https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19010399.

Deshpande, A., & Ramachandran, R. (2022). Early childhood stunting and later life outcomes: A longitudinal analysis. Economics & Human Biology, 44, 101099. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ehb.2021.101099.

Dewey, K. G., & Begum, K. (2011). Long‐term consequences of stunting in early life—PMC. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 7, 5–18. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1740-8709.2011.00349.x.

Dittmar, J. E., & Meisenzahl, R. R. (2020). Public goods institutions, human capital, and growth: Evidence from German history. The Review of Economic Studies, 87(2), 959–996. https://doi.org/10.1093/restud/rdz002.

Duflo, E. (2012). Women Empowerment and Economic Development. Journal of Economic Literature, 50(4), 1051–1079. https://doi.org/10.1257/jel.50.4.1051.

Eshiwani, G. S. (1990). Implementing Educational Policies in Kenya. World Bank Discussion Papers No. 85. Africa Technical Department Series.

Fasih, T. (2008). Linking education policy to labor market outcomes. World Bank Publications. https://doi.org/10.1596/978-0-8213-7509-9.

Ferré, C. (2009). Age at first child: does education delay fertility timing? The case of Kenya. The Case of Kenya (February 1, 2009). World Bank Policy Research Working Paper, (4833). https://doi.org/10.1596/1813-9450-4833.

Field, E., & Ambrus, A. (2008). Early Marriage, Age of Menarche, and Female Schooling Attainment in Bangladesh. Journal of Political Economy, 116(5), 881–930. https://doi.org/10.1086/593333.

Frost, M. B., Forste, R., & Haas, D. W. (2005). Maternal education and child nutritional status in Bolivia: Finding the links. Social Science & Medicine, 60(2), 395–407. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.05.010.

Fujii, T., Shonchoy, A. S., & Xu, S. (2018). Impact of electrification on children’s nutritional status in rural Bangladesh. World Development, 102, 315–330. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2017.07.016.

Gakidou, E., Cowling, K., Lozano, R., & Murray, C. J. (2010). Increased educational attainment and its effect on child mortality in 175 countries between 1970 and 2009: A systematic analysis. The Lancet, 376(9745), 959–974. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61257-3.

Ghuman, S., Behrman, J. R., Borja, J. B., Gultiano, S., & King, E. M. (2005). Family Background, Service Providers, and Early Childhood Development in the Philippines: Proxies and Interactions. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 54(1), 129–164. https://doi.org/10.1086/431258.

Gibbs, H. D., Kennett, A. R., Kerling, E. H., Yu, Q., Gajewski, B., Ptomey, L. T., & Sullivan, D. K. (2016). Assessing the Nutrition Literacy of Parents and Its Relationship With Child Diet Quality. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior, 48(7), 505–509.e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneb.2016.04.006.

Glewwe, P. (1999). Why Does Mother’s Schooling Raise Child Health in Developing Countries? Evidence from Morocco. The Journal of Human Resources, 34(1), 124–159. https://doi.org/10.2307/146305.

Goldberg, J., & Smith, J. (2013). The Effects of Education on Labor Market Outcomes. In Handbook of Research in Education Finance and Policy. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203961063.ch38.

Grépin, K. A., & Bharadwaj, P. (2015). Maternal education and child mortality in Zimbabwe. Journal of Health Economics, 44, 97–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2015.08.003.

Grossman, M. (2006). Education and nonmarket outcomes. Handbook of the Economics of Education, 1, 577–633. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1574-0692(06)01010-5.

Grytten, J., Skau, I., & Sørensen, R. J. (2014). Educated mothers, healthy infants. The impact of a school reform on the birth weight of Norwegian infants 1967–2005. Social Science & Medicine, 105, 84–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.01.008.

Güneş, P. M. (2015). The role of maternal education in child health: Evidence from a compulsory schooling law. Economics of Education Review, 47, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2015.02.008.

Guo, S. (2020). The legacy effect of unexploded bombs on educational attainment in Laos. Journal of Development Economics, 147, 102527. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2020.102527.

Hart, C. N., Raynor, H. A., Jelalian, E., & Drotar, D. (2010). The association of maternal food intake and infants’ and toddlers’ food intake. Child: Care, Health and Development, 36(3), 396–403. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2214.2010.01072.x.

Herman, E. (2012). Education’s Impact on the Romanian Labour Market in the European Context. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 46, 5563–5567. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.06.476.

Hobcraft, J. (1993). Women’s education, child welfare and child survival: A review of the evidence. Health Transition Review, 3(2), 159–175. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40652016..

Hobcraft, J. N., McDonald, J. W., & Rutstein, S. O. (1985). Demographic Determinants of Infant and Early Child Mortality: A Comparative Analysis. Population Studies, 39(3), 363–385. https://doi.org/10.1080/0032472031000141576.

Imbo, A. E., Mbuthia, E. K., & Ngotho, D. N. (2021). Determinants of neonatal mortality in Kenya: evidence from the Kenya demographic and health survey 2014. International Journal of Maternal and Child Health and AIDS, 10(2), 287. https://doi.org/10.21106/ijma.508.

Kar, B. R., Rao, S. L., & Chandramouli, B. A. (2008). Cognitive development in children with chronic protein energy malnutrition. Behavioral and Brain Functions, 4(1), 31. https://doi.org/10.1186/1744-9081-4-31.

Karadja, M., & Prawitz, E. (2019). Exit, voice, and political change: Evidence from Swedish mass migration to the United States. Journal of Political Economy, 127(4), 1864–1925. https://doi.org/10.1086/701682.

Keats, A. (2018). Women’s schooling, fertility, and child health outcomes: Evidence from Uganda’s free primary education program. Journal of Development Economics, 135, 142–159. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2018.07.002.

Keats, E. C., Macharia, W., Singh, N. S., Akseer, N., Ravishankar, N., Ngugi, A. K., … & Bhutta, Z. A. (2018). Accelerating Kenya’s progress to 2030: understanding the determinants of under-five mortality from 1990 to 2015. BMJ global health, 3(3). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2017-000655.

Kim, H. S. (2020). Failed Policy? The Effects of Kenya’s Education Reform: Use of Natural Experiment and Regression Discontinuity Design. Social Science Quarterly, 101(1), 406–419. https://doi.org/10.1111/ssqu.12720.

Kimani-Murage, E. W., Fotso, J. C., Egondi, T., Abuya, B., Elungata, P., Ziraba, A. K., & Madise, N. (2014). Trends in childhood mortality in Kenya: the urban advantage has seemingly been wiped out. Health & place, 29, 95–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2014.06.003.

Krishnakumar, J., & Nogales, R. (2020). Education, skills and a good job: A multidimensional econometric analysis. World Development, 128, 104842. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2019.104842.

Larsson, C., & Stanfors, M. (2014). Women’s Education, Empowerment, and Contraceptive Use in sub-Saharan Africa: Findings from Recent Demographic and Health Surveys. African Population Studies, 28(0), 1022. https://doi.org/10.11564/28-0-554.

Le, K., & Nguyen, M. (2020). Shedding light on maternal education and child health in developing countries. World Development, 133, 105005. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105005.

Le, H., & Azhgaliyeva, D. (2023). Carbon pricing and firms’ GHG emissions: Firm-level empirical evidence from East Asia. Journal of Cleaner Production, 139504. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.139504.

Lewbel, A. (2012). Using heteroscedasticity to identify and estimate mismeasured and endogenous regressor models. Journal of Business & Economic Statistics, 30(1), 67–80. https://doi.org/10.1080/07350015.2012.643126.

Li, Z., Kim, R., Vollmer, S., & Subramanian, S. V. (2020). Factors Associated With Child Stunting, Wasting, and Underweight in 35 Low- and Middle-Income Countries. JAMA Network Open, 3(4). https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.3386.

Lindeboom, M., Llena-Nozal, A., & van der Klaauw, B. (2009). Parental education and child health: Evidence from a schooling reform. Journal of Health Economics, 28(1), 109–131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2008.08.003.

Lindskog, A., & Durevall, D. (2021). To educate a woman and to educate a man: Gender‐specific sexual behavior and human immunodeficiency virus responses to an education reform in Botswana. Health Economics, 30(3), 642–658. https://doi.org/10.1002/hec.4212.

Lundborg, P., Nilsson, A., & Rooth, D.-O. (2014). Parental Education and Offspring Outcomes: Evidence from the Swedish Compulsory School Reform. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 6(1), 253–278. https://doi.org/10.1257/app.6.1.253.

Ma, M. (2019). Does children’s education matter for parents’ health and cognition? Evidence from China. Journal of Health Economics, 66, 222–240. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2019.06.004.

Machio, P. M. (2018). Determinants of neonatal and under-five mortality in Kenya: do antenatal and skilled delivery care services matter? Journal of African Development, 20(1), 59–67. https://doi.org/10.5325/jafrideve.20.1.0059.

Makate, M. (2016). Education Policy and Under-Five Survival in Uganda: Evidence from the Demographic and Health Surveys. Social Sciences, 5(4), 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci5040070.

Makate, M., & Makate, C. (2016). The causal effect of increased primary schooling on child mortality in Malawi: Universal primary education as a natural experiment. Social Science & Medicine, 168, 72–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.09.003.

Mariella, V. (2023). Landownership concentration and human capital accumulation in post-unification Italy. Journal of Population Economics, 36(3), 1695–1764. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-022-00907-z.

Martorell, R. (1999). The Nature of Child Malnutrition and Its Long-Term Implications. Food and Nutrition Bulletin, 20(3), 288–292. https://doi.org/10.1177/156482659902000304.

Masuda, K., & Yamauchi, C. (2020). How does female education reduce adolescent pregnancy and improve child health?: Evidence from Uganda’s universal primary education for fully treated cohorts. The Journal of Development Studies, 56(1), 63–86. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2018.1546844.

McCrary, J., & Royer, H. (2011). The Effect of Female Education on Fertility and Infant Health: Evidence from School Entry Policies Using Exact Date of Birth. The American Economic Review, 101(1), 158–195. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.101.1.158.

Mejía-Guevara, I., Zuo, W., Bendavid, E., Li, N., & Tuljapurkar, S. (2019). Age distribution, trends, and forecasts of under-5 mortality in 31 sub-Saharan African countries: A modeling study. PLoS medicine, 16(3), e1002757 https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002757.

Minh, H. V., Giang, K. B., Hoat, L. N., Chung, L. H., Huong, T. T. G., Phuong, N. T. K., & Valentine, N. B. (2016). Analysis of selected social determinants of health and their relationships with maternal health service coverage and child mortality in Vietnam. Global Health Action, 9(1), 28836. https://doi.org/10.3402/gha.v9.28836.

Moehling, C. M. (1995). The Intrahousehold Allocation of Resources and the Participation of Children in Household Decision-Making: Evidence from Early Twentieth In Century America. Northwestern University, Department of Economic.

De Neve, J.-W., & Subramanian, S. V. (2018). Causal Effect of Parental Schooling on Early Childhood Undernutrition: Quasi-Experimental Evidence From Zimbabwe. American Journal of Epidemiology, 187(1), 82–93. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwx195.

Nga, N. T., Hoa, D. T. P., Målqvist, M., Persson, L.-Å., & Ewald, U. (2012). Causes of neonatal death: Results from NeoKIP community-based trial in Quang Ninh province, Vietnam. Acta Paediatrica, 101(4), 368–373. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1651-2227.2011.02513.x.

Nguyen, P. H., Avula, R., Ruel, M. T., Saha, K. K., Ali, D., Tran, L. M., Frongillo, E. A., Menon, P., & Rawat, R. (2013). Maternal and Child Dietary Diversity Are Associated in Bangladesh, Vietnam, and Ethiopia. The Journal of Nutrition, 143(7), 1176–1183. https://doi.org/10.3945/jn.112.172247.

Nguyen-Phung, H. T. (2023). The impact of maternal education on child mortality: Evidence from an increase tuition fee policy in Vietnam. International Journal of Educational Development, 96, 102704. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2022.102704.

Nguyen-Phung, H. T., & Le, H. (2023). Urbanization and Health Expenditure: An Empirical Investigation from Households in Vietnam. AGI Working Paper. https://en.agi.or.jp/media/publications/workingpaper/WP2023-06.pdf.

Nguyen-Phung, H. T., & Nthenya, N. N. (2023). The causal effect of education on women’s empowerment: evidence from Kenya. Education Economics, 1-19. https://doi.org/10.1080/09645292.2023.2202370.

Ohba, A. (2009). Does free secondary education enable the poor to gain access? A study from rural Kenya. CREATE Pathways to Access, Research Monograph No 21. Washington, DC: Oxford University press. http://kerd.ku.ac.ke/123456789/392.

Omariba, D. W. R., Beaujot, R., & Rajulton, F. (2007). Determinants of infant and child mortality in Kenya: an analysis controlling for frailty effects. Population Research and Policy Review, 26, 299–321. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-007-9031-z.

Orenstein, P. (2013). SchoolGirls. Young Women, Self-Esteem, and the Confidence Gap. Bantam Doubleday Dell Publishing Group, Inc.

Osili, U. O., & Long, B. T. (2008). Does female schooling reduce fertility? Evidence from Nigeria. Journal of Development Economics, 87(1), 57–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2007.10.003.

Oster, E. (2019). Unobservable selection and coefficient stability: Theory and evidence. Journal of Business & Economic Statistics, 37(2), 187–204. https://doi.org/10.1080/07350015.2016.1227711.

Papas, M. A., Hurley, K. M., Quigg, A. M., Oberlander, S. E., & Black, M. M. (2009). Low-income, African American Adolescent Mothers and Their Toddlers Exhibit Similar Dietary Variety Patterns. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior, 41(2), 87–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneb.2008.01.005.

Parsons, J., & McCleary-Sills, J. (2014). Preventing Child Marriage: Lessons from World Bank Group Gender Impact Evaluations. World Bank Group.

Perin, J., Mulick, A., Yeung, D., Villavicencio, F., Lopez, G., Strong, K. L., & Liu, L. (2022). Global, regional, and national causes of under-5 mortality in 2000–19: an updated systematic analysis with implications for the Sustainable Development Goals. The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health, 6(2), 106–115. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-4642(21)00311-4.

Phommachanh, S., Essink, D. R., Wright, P. E., Broerse, J. E. W., & Mayxay, M. (2021). Maternal health literacy on mother and child health care: A community cluster survey in two southern provinces in Laos. PLoS ONE, 16(3), e0244181. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0244181.

Piper, B., Zuilkowski, S. S., & Ong’ele, S. (2016). Implementing mother tongue instruction in the real world: Results from a medium-scale randomized controlled trial in Kenya. Comparative Education Review, 60(4), 776–807. https://doi.org/10.1086/688493.

Rivera-Garrido, N. (2022). Can education reduce traditional gender role attitudes? Economics of Education Review, 89, 102261. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2022.102261.

Rivers, D., & Vuong, Q. H. (1988). Limited information estimators and exogeneity tests for simultaneous probit models. Journal of Econometrics, 39(3), 347–366. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-4076(88)90063-2.

Robinson, S., Marriott, L., Poole, J., Crozier, S., Borland, S., Lawrence, W., Law, C., Godfrey, K., Cooper, C., & Inskip, H. (2007). Dietary patterns in infancy: The importance of maternal and family influences on feeding practice. British Journal of Nutrition, 98(05), 1029–1037. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007114507750936.

Samarakoon, S., & Parinduri, R. A. (2015). Does Education Empower Women? Evidence from Indonesia. World Development, 66, 428–442. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2014.09.002.

Sifuna, D. N. (1992). Prevocational subjects in primary schools in the 8-4-4 education system in Kenya. International Journal of Educational Development, 12(2), 133–145. https://doi.org/10.1016/0738-0593(92)90035-K.

Smith, L. C., Ramakrishnan, U., Ndiaye, A., Haddad, L., & Martorell, R. (2003). The Importance of Women’s Status for Child Nutrition in Developing Countries. Food and Nutrition Bulletin, 24(3), 287–288. https://doi.org/10.1177/156482650302400309.

Somerset, A. (2009). Universalising primary education in Kenya: the elusive goal. Comparative Education, 45(2), 233–250. https://doi.org/10.1080/03050060902920807.

Somerset, A. (2007). A Preliminary Note on Kenya Primary School Enrolment Trends over Four Decades. Create Pathways to Access. Research Monograph No. 9. http://www.create-rpc.org/pdf_documents/PTA9.pdf.

Strauss, J., & Thomas, D. (1995). Human resources: Empirical modeling of household and family decisions. In Handbook of Development Economics: Vol. III. Elsevier Science. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1573-4471(05)80006-3.

Tesema, G. A., Seifu, B. L., Tessema, Z. T., Worku, M. G., & Teshale, A. B. (2022). Incidence of infant mortality and its predictors in East Africa using Gompertz gamma shared frailty model. Archives of Public Health, 80(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13690-022-00955-7.

Thomas, D., Strauss, J., & Henriques, M.-H. (1991). How Does Mother’s Education Affect Child Height?. The Journal of Human Resources, 26(2), 183–211. https://doi.org/10.2307/145920.

Tranchant, J. P., Justino, P., & Müller, C. (2020). Political violence, adverse shocks and child malnutrition: Empirical evidence from Andhra Pradesh, India. Economics & Human Biology, 39, 100900. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ehb.2020.100900.

UNICEF. (2022). https://data.unicef.org/topic/child-survival/under-five-mortality/.

Wang, H., & Cheng, Z. (2022). Kids eat free: School feeding and family spending on education. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 193, 196–212. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2021.11.023.

Wang, T. (2021). The effect of female education on child mortality: Evidence from Indonesia. Applied Economics, 53(27), 3207–3222. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036846.2021.1877253.

Wanjohi, A. M. (2011). Development of education system in Kenya since independence. KENPRO Online Papers Portal, 5. https://www.kenpro.org/papers/education-system-kenya-independence.htm.

Wolde, M., Berhan, Y., & Chala, A. (2015). Determinants of underweight, stunting and wasting among schoolchildren. BMC Public Health, 15(1), 8 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-014-1337-2.

World Bank. (2023). https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.DYN.MORT?locations=KE.

Yang, G., Nie, Y., Li, H., & Wang, H. (2023). Digital transformation and low-carbon technology innovation in manufacturing firms: The mediating role of dynamic capabilities. International Journal of Production Economics, 263, 108969. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2023.108969.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Hang Thu Nguyen-Phung: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition. Yijun Yu: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Phuc H Nguyen: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Hai Le: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix A

In this section, we provide detailed computations to ascertain the probability associated with the partially treated group. While the legal age for a student enroll in primary school is six years old, late entry often leads to variations in enrollment age, thereby introducing a substantial source of measurement error in the assignment variable. Utilizing data sourced from Somerset (2007) delineating the distribution of entry ages for Grade one, a conditional probability of entering the primary school level is computed specifically for the age range of 6 to 10.

Kenya exhibits a noteworthy and prevalent occurrence of repetition in primary school level, permitting students to prolong their study duration beyond the seven-year schedule stipulated by the old system (Somerset, 2009). To mitigate this issue, data on repetition rates from Somerset (2007) and transition rates to secondary school level from Ohba (2009) are gathered. Afterwards, we designate a probability to each birth cohort, demonstrating the possibility of repeating a grade.Footnote 12 Considering the two conditional probabilities, the computation of the probability pertaining to the partially treated cohorts is presently undertaken in the following manner:

where the probability of completion of primary school is calculated as follows:

Here, s, y, en, and r denote the schooling cohort associated with an individual ‘s completion of primary education, an individual’s birth year, the entry age to Grade 1, and the number of the repeated year(s), respectively.

Appendix B

The baseline OLS findings, detailed in Appendix Table 13, highlight a statistically significant correlation between maternal education and the likelihood of a child experiencing death at age one or younger, as well as death at age five or younger. To be specific, higher maternal schooling is linked to a decrease of approximately 0.03 percentage points in both the chances of a child being deceased at age one or younger and deceased at age five or younger.

Additionally, our analysis addresses concerns pertaining to potential omitted variable bias through the application of Oster’s (2019) bounding approach, a method extensively employed in the literature (Bevis et al., 2023; Deshpande and Ramachandran, 2022; Fujii et al., 2018). This method evaluates the robustness of results against omitted variable bias, assuming that the connection between observed covariates and the treatment variable provides insights into the relationship between the treatment variable and unobservable factors.

Oster’s (2019) method assesses the influence of female education on children’s mortality rates across a range of values denoted as \(\widetilde{\beta }\) to \({\beta }^{* }\). Two critical pieces of information, \(\delta\) (indicating the relative importance of observable versus unobservable variables in introducing bias) and \({R}_{\max }\) (the R2 from a model encompassing both observable and unobservable variables), play a pivotal role. Oster’s estimation assumes \(\delta =1\) and imposes constraints on \({R}_{\max }=min \{1.3\widetilde{R},\,1\}\), with \(\widetilde{R}\) derived from empirical evidence. Our analysis calculates \({R}_{\max }\) following Oster’s guidelines, determining \({R}_{\max }=min \{1.3\widetilde{R},\,1\}\).

Appendix Table 14 presents the empirical findings derived from Oster’s methodology. In Column 1, where we assess both measures of children’s mortality rates, the identified sets do not include zero. This illustrates the strength and reliability of our estimates even when unobserved variables are not considered. Moving to Column 3, the \(\delta\) coefficient surpasses 1, which aligns with Oster’s (2019) recommended threshold. This indicates that omitted variables would need a more substantial impact than observed variables to negate the significant influence of maternal education on child mortality rates.

Appendix C

Appendix D

Figure 3

Plausibly exogenous IV: The impacts of maternal education on their child’s mortality rate (dead at age five or younger) using the UCI approach of Conley et al. (2012)

This section presents the estimated effects of maternal education on child mortality rates (dead at age five or younger) when the IV, the probability of exposure to the policy, is plausibly exogenous. The results confirm the existence of a negative and statistically significant influence of maternal education on the likelihood of a child’s death at age five or younger, even when accommodating a substantial deviation from the assumption of perfect exogeneity.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Nguyen-Phung, H.T., Yu, Y., Nguyen, P.H. et al. Maternal education and child survival: causal evidence from Kenya. Rev Econ Household (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-024-09717-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-024-09717-6