Abstract

This paper investigates the effects of health insurance coverage among low-income people on personal bankruptcies at the county level and the state level, based on the hypothesis that having health insurance reduces the risk of medical out-of-pocket spending and consequently decreases the likelihood of financial distress. In order to estimate the causal effects of health insurance coverage on personal bankruptcy, I exploit the Medicaid expansion under the Affordable Care Act as a source of exogenous variation in health insurance coverage and use it as an instrumental variable. Using bankruptcy filings from the US Court, I find that an increase in the share of low-income people with health insurance reduces Chapter 7 bankruptcy rates both at the county level and state level. The implied magnitudes of my estimated impacts are quantitatively important.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

In the United States, medical expenditures often cause financial distress, especially among uninsured low-income people. One of the major goals of expansion of Medicaid eligibility under the Affordable Care Act (ACA), which was passed into the law in 2010, was to improve their ability to pay their medical expenses. The ACA expanded Medicaid eligibility to all individuals earning less than 138% of the federal poverty level—prior to passage of the ACA, Medicaid eligibility was limited to minor children and single parents in most states, subject to federal mandatory minimum coverage levels. The ACA’s most major provisions came into force in 2014. As shown in Fig. 1, the share of people covered by private and/or public health insurance, regardless of their income levels, started to increase gradually in 2010 but drastically in 2014, due to the ACA’s (1) individual mandate provision, which requires most citizens and legal residents of the United States to have health insurance or pay a tax penalty,Footnote 1 and (2) health exchanges (i.e., the Health Insurance Marketplace), which are regulated marketplaces administered by either federal or state governments and provide health plan shopping and enrollment services to people and small businesses. However, the impact of the ACA was greater for people with income below 138% of the federal poverty level, due to the Medicaid expansion provision of the ACA.

At the same time, the number of personal bankruptcies in the United States started to decline in 2011 (see Fig. 2), after increasing during the period 2007–2010, presumably because of the Great Recession that resulted in financial distress among many Americans.Footnote 2 As the literature suggests that medical expenditures are one of the major causes of bankruptcies, and financial protection provided by health insurance largely eliminates medical expenses, this paper examines if this decline in personal bankruptcies in the 2010s can be explained by the increase in health insurance coverage among low-income people.

To have the greatest possible confidence in the causal relationship that this study seeks to establish, I use an instrumental variables strategy. I use the Medicaid expansion under the ACA as a source of exogeneous variation to instrument the share of low-income people with health insurance. Though intended to apply nationwide, the Supreme Court ruled that the states had to be allowed to decide for themselves whether they would adopt the expanded Medicaid eligibility rules. As a result, the expansion of Medicaid in states provides a plausible source of exogenous variation. Evidence suggests that states that expanded Medicaid in 2014 experienced an increase in their rates of health insurance coverage compared to non-expansion states. Frean et al. (2017), using the 2012–2015 American Community Survey, find that insurance coverage increased among those who were newly eligible for Medicaid. Courtemanche et al. (2017) find that coverage increased by 5.9% points in expansion states compared to 2.8% points in states that did not expand Medicaid by the end of 2014 (see also Kaestner et al. (2017); Miller and Wherry (2017); Wherry and Miller (2016)).

This study uses the bankruptcy filing rate as a proxy for financial distress and adds to a growing literature studying the link between financial health and health insurance. The contribution of this paper is twofold. First, this study uses aggregate (county and state) data. Previous studies that examined the relationship between health insurance and financial health use individual data. The only exception seems to be Gross and Notowidigdo (2011), who used state-level data, but they examined the period 1992–2004, during which personal bankruptcies were rising. While individual-level data provide researchers with more flexibility in their analyses, using aggregate data is important and relevant in studies that examine policy changes, given that many policy interventions often take place at an aggregate level (see Abadie et al. (2010) for a review). Furthermore, one issue with individual level data in natural experimental studies is that the treatment variable does not vary within groups, but the groups may have a shared error structure. Moulton (1990) shows that standard errors are biased more downward, which leads to greater statistical significance, when group sizes are larger and intraclass correlations of the regression errors and the regressors included in the model are higher, thereby increasing the likelihood of incorrectly rejecting the null hypothesis. One approach to alleviate this concern is to aggregate data to the same level as the treatment variable (see Bertrand et al. (2004)).Footnote 3

Second, studies that use individual-level data do not contain information on all personal bankruptcies, which are relatively rare on a per capita basis, and their data rely on the accuracy and timeliness of the credit bureau in collecting public record, not the direct collection of filings. This study uses data from the US Court that contain all bankruptcy filings from fifty states and the District of Columbia in the United States.

The results found in this study show differences in the effect of health insurance coverage on personal bankruptcies. Specifically, an increase in health insurance coverage among low-income people reduces Chapter 7, but not Chapter 13, bankruptcy rates. My conservative estimate indicates that a ten-percentage points increase (~1 standard deviation) in the share of the population covered by health insurance contributes to approximately a reduction of 0.4 per 1000 adults for the Chapter 7 bankruptcy rates at the county level and the state level. The implied magnitudes of my estimated impacts are quantitatively important. A back-of-envelope calculation suggests that, among states that expanded Medicaid in January 2014, more than half of the decline in their Chapter 7 bankruptcy rates that occurred during the period 2014–2018 is attributable to the increase in health insurance coverage among low-income people who were presumably mostly new Medicaid beneficiaries.

2 Literature review

Several studies suggest that out-of-pocket medical costs are one of the major causes of bankruptcies. Himmelstein et al. (2009) find that ~29% of all bankruptcies in 2007 were medical.Footnote 4 Mathur (2006) uses the Panel Study of Income Dynamics and finds that up to 27% of all bankruptcy filings involved cases where medical bills were the primary form of debt. Recently, Brevoort et al. (2017) find that, using a panel of five million credit records from the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, approximately third of bankruptcy filers held medical debt, worth, on average, $2000, though the top 1% of them had the average of $24,000 medical debt. Not surprisingly, uninsured people often have trouble paying their medical bills (see Hu et al. (2018) for a review). Dobkins et al. (2018) find that uninsured people who became hospitalized were more than twice likely to file for bankruptcy.

Perhaps not surprisingly, past studies find that expanding health care coverage reduces financial distress among those who experience adverse health shocks. Finkelstein et al. (2012) find that the Oregon Health Insurance Experiment, a random experiment in which uninsured adults in Oregon randomly acquired the ability to enroll in Medicaid, led to reduced risk of medical debt accumulation. Mazumder and Miller (2016) find that Massachusetts health care reform in 2006 reduced bankruptcy filings among subprime borrowers. Gross and Notowidigdo (2011) exploit cross-state variation in Medicaid expansions from 1992 to 2004 and find that personal bankruptcies declined as a result of Medicaid expansions. However, it is important to note that economic theory does not necessarily predict a positive effect of free or low-cost health care on personal finance. While obtaining free health insurance is likely to reduce the likelihood of low-income individuals to declare bankruptcy due to medical expenses when medical issues arise, having health insurance may also encourage low-income individuals to save less for precautionary reasons and spend, or even borrow, more.

There are three studies that examine the effect of Medicaid expansions under the ACA on personal bankruptcies. Hu et al. (2018) find the Medicaid expansions did not reduce personal bankruptcies, while reducing unpaid bills and medical debt, using the 2010–2015 American Community Survey and the Federal Reserve Bank of New York Consumer Credit Panel/Equifax, a major credit reporting agency. Brevoort et al. (2017) find that financially vulnerable consumers (with low credit score) were less likely to file for bankruptcy if they lived in states that had expanded Medicaid. Caswell and Waidmann (2017) find that the ACA Medicaid expansions resulted in a 2.8% reduction in the probability of a new bankruptcy filings. Therefore, when it comes to personal bankruptcies from individual data, evidence is somewhat mixed and inconclusive. It is also important to point out that these studies examine those who were likely to be eligible for Medicaid but might not have been enrolled in Medicaid.

3 Data and methods

This study uses the period 2010–2018, during which personal bankruptcies continued to decline, but the period 2009–2017 is used for health insurance coverage because there should be some delay between the time of the onset of financial distress caused by negative health shocks and the filing of a bankruptcy petition. My data on health insurance coverage are obtained from U.S. Census Bureau (2020).Footnote 5 I use the share of people with health insurance among those whose family income is less than 138% of the federal poverty level (FPL) and under age 65,Footnote 6 because my instrument, the Medicaid expansion, affected only this group in expansion states.

My bankruptcy data consist of counties in fifty states and the District of Columbia from 2010 to 2018. Bankruptcy data at the county level are obtained from the US Court website (2019).Footnote 7 I use total personal bankruptcies (Chapter 7, Chapter 11, and Chapter 13 combined), Chapter 7 bankruptcies, and Chapter 13 bankruptcies.Footnote 8 Chapter 7 offers the consumer a quick discharge of her debts, but most of her property is sold and used to pay her your debts. The consumer can only keep assets used as collateral if her creditor consents. To qualify for Chapter 7 bankruptcy filing, one must pass a “means” test, i.e., her income must be low enough to be under income limits that vary by state. Thus, Chapter 7 bankruptcy is generally meant for those who do not earn much money and have assets with little or no equity. Chapter 13 offers the consumer more protection against her creditors, but if she is to receive a discharge, the consumer must remain in bankruptcy and make payments for 3 to 5 years.Footnote 9 If the consumer successfully completes a court-mandated repayment plan, she may be able to keep her property. Very few consumers file under Chapter 11. During the sample period 2010–2018, of the 6,972,564 personal bankruptcies, just 8983 (~0.13%) were filed under Chapter 11.Footnote 10 Table 7 in the appendix shows detailed differences between different types of bankruptcies.

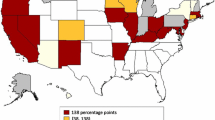

Bankruptcy rates are expressed as per 1000 adults aged 20 and older (adults hereafter), and the data for adult population are obtained from U.S. Census Bureau (2019a). Figures 6–8 in the appendix show the geographical distribution of total personal bankruptcies, Chapter 7 bankruptcies, and Chapter 13 bankruptcies, respectively, per 1000 adults across counties over time. Total bankruptcy rates were higher in the West Coast, the South, the Midwest, and the Northeast during the recession and subsequent recovery period. However, examining Chapter 7 and Chapter 13 bankruptcies separately reveals that Chapter 7 bankruptcy rates are not particularly high in the South, and Chapter 13 bankruptcy rates tend to be higher in the South throughout the period 2010–2018. This is likely due to the large population of African Americans in the South, as they tend to file Chapter 13 petitions at substantially higher rates than other racial groups (Morrison and Uettwiller 2018). Overall, during the period 2010–2018, the average county experienced less than four bankruptcy filings per 1000 adults, suggesting that personal bankruptcy is a rare event in most counties.

I begin by looking at simple correlations between the change in the share of insured population and bankruptcies at the state level for the period, as shown in Fig. 3. The OLS regression line is inserted in each figure. The effects of fixed state characteristics, such as historically high bankruptcy rates and health insurance coverage, are eliminated by differencing. It seems that states that experienced an increase in the share of low-income population with health insurance tend to have experienced a decline in bankruptcy rates, regardless of bankruptcy types, though the correlation is weaker for Chapter 13 bankruptcy rates. This is not surprising because, as mentioned above, one’s income must be low enough to qualify for Chapter 7 bankruptcy, and therefore an increase in insurance coverage among low-income people is more likely to reduce Chapter 7 bankruptcies due to medical expenses than Chapter 13 bankruptcies. Figure 4 shows essentially the same relationship at the county level, though the association for Chapter 13 bankruptcies is considerably weaker when the data are plotted for counties.

The fundamental concern when we attempt to interpret these associations as causal effects of health insurance coverage on bankruptcies is that these two variables are endogenous. Potential omitted variables include local economic conditions—higher income can both reduce the number of uninsured people and bankruptcies. In addition, reverse causality may be present in the relationship. On one hand, those who have just filed for a bankruptcy due to their medical expenses may decide to obtain health insurance to avoid exorbitant medical bills in the future. On the other hand, they may be more likely to keep forgoing health insurance if their financial situation has not improved enough after the bankruptcy.

To isolate the portion of the correlation that is due to the causal effect of health insurance coverage on bankruptcy filings, I employ an instrumental variables strategy. Specifically, I instrument the share of low-income people with health insurance with the Medicaid expansion under the ACA, which provided plausibly exogenous variation in health insurance coverage. The choice of instrument is motivated by the fact that not all states expanded Medicaid, and even among those states that expanded Medicaid, their implementation dates varied.

Information on the ACA Medicaid expansions comes from the Kaiser Family Foundation (2019) and Hu et al. (2018). First, it is important to note that Delaware, Massachusetts, New York, and Vermont fully expanded Medicaid to parents and childless adults prior to 2014.Footnote 11 These states had more generous health insurance coverage of their low-income populations before Medicaid expansion under the ACA in 2014. These four states have been viewed as non-expansion, control states in some studies (e.g., Kaestner et al. 2017; Hu et al. 2018) but excluded from other studies (e.g., Wherry and Miller 2016; Slusky and Ginther 2018). These states may be systematically different (e.g., more economically vibrant), and inability to account for the differences can produce spurious results. In this study I first place them in the control group since they did not change status, but I also exclude them later as a robustness check. Connecticut, Minnesota, the District of Columbia, and most counties in CaliforniaFootnote 12 expanded Medicaid under the ACA prior to 2014 (4/1/2010, 3/1/2011, 7/1/2010, and 1/1/2012, respectively).Footnote 13 They are different from the aforementioned four states since they did not have a prior generous Medicaid or Medicaid-like program. Twenty-one states (including Delaware, Massachusetts, New York, Vermont) had signed on when the expansion went into effect in 2014. Michigan (4/1/2014) and New Hampshire (8/15/2014) expanded mid-2014. Pennsylvania (1/1/2015), Indiana (2/1/2015), Alaska (9/1/2015) expanded in 2015; Montana (1/1/2016) and Louisiana (7/1/2016) expanded in 2016. Virginia (1/1/2019), Maine (1/10/2019), and Idaho (11/1/2019) expanded in 2019. Utah partially expanded Medicaid in April of 2019, and Nebraska is moving forward with a plan to expand coverage by the fall of 2020. Because the bankruptcy data cover the period 2010–2018, and 1-year lagged regressors will be used, states that expanded Medicaid after 2017 are considered non-expansion states throughout this work. Figure 9 in the appendix summarizes the timing of the ACA Medicaid expansions.

Figure 10 in the appendix shows the geographical distributions of the share of people with health insurance at the county level. Counties in states that had generous Medicaid, such as Massachusetts and New York, exhibit high rates of insurance coverage among low-income people throughout the period. Counties in states that expanded Medicaid in 2014, such as Arizona, Arkansas, Oregon, and Washington, experienced a large increase in the share of low-income people with health insurance in 2014, while health insurance coverage among low-income population in counties in non-expansion states, such as Florida, Texas, and Georgia Oklahoma, remained low even after 2014.

For the Medicaid expansion to be a valid instrument, it needs to be correlated with the share of low-income people with health insurance. Figure 5 shows the trend in the share of people with health insurance among states that expanded in January 2014 (i.e., traditional expansion states) and non-expansion states and confirms the stylized fact that the Medicaid expansion resulted in a larger increase in the number of people with health insurance in expansion states than in non-expansion states.Footnote 14 The gap between traditional expansion states and non-expansion states widened considerably after 2013, clearly indicating the treatment effect.

Another necessary condition for a good instrument is that it does not exert any direct effect on bankruptcy filings besides the indirect effect through increased health insurance coverage among low-income individuals. Even though the Medicaid expansion created quasi-experimental variation, the potential non-randomness of states’ decisions to expand Medicaid is harder to deal with. As the exogeneity of the instrument is fundamentally untestable, the best I can do is to control for observable characteristics of counties and states and assume that states’ decisions to expand Medicaid is not directly correlated with personal bankruptcy.

My empirical strategy is two-stage least squares (2SLS), using county-level data and state-level data separately. In the first stage for the county-level analysis, I estimate the following equation using weighted least squares with weights proportional to county population:

where i, t, s denote, respectively, county, year and state. PercentInsuredit a continuous variable for the share of low-income population with health insurance.Footnote 15MedicaidExpansionst is a variable that takes a value of one if the county i is located in state s that expanded Medicaid on January of year t. For early and late adopters, if they expanded Medicaid in, say, April, the variable equals 9/12 = 0.75. Otherwise, the variable takes a value of zero.

In the second stage, I estimate the following equation, using the predicted PercentInsuredit, derived from the first stage estimation, again using weighted least squares with weights proportional to county population:

Bankruptcyit is the bankruptcy filing rate (per 1000 adults). In both Eqs. (1) and (2), county fixed-effects λi remove time-invariant county characteristics (e.g., historically high insured population or bankruptcy filings), and year fixed-effects θt remove yearly macroeconomic shocks and national trends. Xit is county-level variables to capture the demographic, racial, and economic structure of counties. Yearly county-level poverty rates are obtained from U.S. Census Bureau (2019b), and yearly county-level unemployment rates are obtained from The Bureau of Labor Statistics (2019a) As demographic controls, I use the population shares of Blacks, Hispanics, and people aged 65 and older, obtained from U.S. Census Bureau (2019a). Table 1 shows summary statistics of county-level variables used in this study. After excluding observations with missing values, the resulting sample size is 26,505 (2945 counties × 9 years).

For the state-level analysis, county-level variables in the equations above are replaced with state-level variables. State-level poverty rates are again obtained from U.S. Census Bureau (2019b). State-level unemployment rates are obtained from The Bureau of Labor Statistics (2019b). The demographic controls are obtained from U.S. Census Bureau (2019c). Table 2 shows summary statistics of state-level variables used in this study.

4 Results

4.1 Baseline results

Table 3 reports the OLS and IV estimates for the county-level data. The standard errors are clustered at the state level. Columns (1)–(3) show the OLS result for the outcome variable is the total bankruptcy rate, Chapter 7 bankruptcy rate, and Chapter 13 bankruptcy rate, respectively. The coefficients of interest are statistically significant and negative at the one-percent level for the total bankruptcy and Chapter 7 bankruptcy but not for the Chapter 13 bankruptcy. This indicates that the result for the total bankruptcy is driven by the Chapter 7 bankruptcy, which is not surprising because Chapter 7 bankruptcies comprise most personal bankruptcies. The magnitude I find suggests that a ten-percentage points (~1 standard deviation) increase in the share of low-income population with health insurance is associated with a 0.8 reduction in the total bankruptcy rates and a 0.7 reduction in the Chapter 7 bankruptcy rates.

Columns (4)–(6) show the 2SLS result when the share of low-income population with health insurance is instrumented with the Medicaid expansion. The coefficients of interest for the total bankruptcy and Chapter 7 bankruptcy are still statistically significant and negative. In the first stage of 2SLS, the instrument has the expected sign and performs very well, as shown in the column (7) in Table 3. The Medicaid expansion is associated with a 5%-points increase in the share of low-income population with health insurance. To reject the hypothesis that the instrument is weak, the rule of thumb is that the first-stage F-statistics should be greater than 10 (Staiger and Stock 1997). The F-statistics on the excluded instrument (not shown) in the first stage is 22 (p < 0.001).

Notably, the size of the coefficients of interest from 2SLS is approximately twice the size of those of OLS. If we interpret the coefficients literally, a ten-percentage points increase in the share of low-income population with health insurance is associated with a 1.3 reduction in the Chapter 7. Considering that the mean Chapter 7 bankruptcy rate is 2.4 during the sample period, the magnitude of this effect is large. However, interpretation of the 2SLS estimates should be done cautiously. 2SLS estimates the local average treatment effect (LATE), which is the average treatment effect only for the subpopulations affected by the observed changes in the instrument. That is, the estimates from 2SLS are the effect only for the portion of an increase in health insurance coverage due to the Medicaid expansions, and not for an increase in health insurance coverage due to the national trend or local economic conditions. Nevertheless, these 2SLS results do indicate that an increase in the share of low-income population with health insurance has a causal impact on Chapter 7 bankruptcies.

Turning to the coefficients of control variables, higher unemployment rates are associated with higher bankruptcy rates, suggesting that negative economic shocks increase financial distress. Larger populations of Hispanics are associated with lower bankruptcy rates. Interestingly, the population share of Blacks is negatively associated with Chapter 13 bankruptcy rates, even though they have higher rates of Chapter 13 bankruptcies than other groups (Morrison and Uettwiller 2018). It seems that, once county fixed effects and local economic conditions are accounted for, an increase in Black populations does not lead to higher Chapter 13 bankruptcy filings.

Table 4 reports the OLS and IV estimates for the state-level data. The coefficients of interest remain substantially the same and statistically significant for the total bankruptcy and Chapter 7 bankruptcy. Again, the instrument performs well in the first stage, with the F-statistics being 16 (p < 0.001). All in all, both county-level and state-level analyses suggest that an increase in health insurance coverage among low-income people has a causal impact on Chapter 7 bankruptcy rates, but not on Chapter 13 bankruptcy rates.

4.2 Robustness checks

I perform two robustness checks. First, I repeat my analysis using 2SLS after excluding Delaware, Massachusetts, New York, and Vermont. As mentioned above, they had more generous health insurance coverage of their low-income populations before the Medicaid expansion under the ACA in 2014, and some studies do not use them as the control group (e.g., Wherry and Miller 2016; Slusky and Ginther 2018). Including these states can be problematic if they have unobservable characteristics that affect both health insurance coverage and bankruptcy. The results for the county-level data and state-level data are shown in the columns (1)–(3) in Tables 5 and 6, respectively. Even when these states are excluded, the magnitude and the level of statistical significance of the coefficients of interest virtually remain the same, suggesting that the main finding is not affected by these states who had generous Medicaid before the ACA.

Second, I add nine census division-year interaction terms.Footnote 16 Even though I include county/state- and year fixed effects, time-varying omitted variables may be present in the regressions. I cannot include state-year interactions despite my county-level data, because Medicaid expansions vary at the state level and thus the coefficient will be unidentified. But by allowing for year fixed effects to vary by the nine census divisions, I can eliminate the between-division variation and hence better control for spatial heterogeneity in differential personal bankruptcy patterns, including region-specific economic shocks.

The results for county-level data and state-level data are shown in the columns (4)–(6) in Table 5 and in Table 6, respectively. The coefficient of interest remains statistically significant only for the Chapter 7 bankruptcy, though only marginally significant at the 10% level for the state-level regression. The first-stage F-statistics on the excluded instrument (not shown) are 15 for the county-level analysis and 17 for the state-level analysis, indicating that the instrument is not weak and has sufficient explanatory power even when division-year interactions are included. These estimates are based on only the variation within each census division and thus less likely to be contaminated with unobservable division-specific economic shocks. This “conservative” estimate indicates that a ten-percentage points increase in the share of low-income people with health insurance reduces Chapter 7 bankruptcy rates approximately by 0.4 both at the county level and the state level. Taken together, adding finer controls for spatial heterogeneity still supports the main finding that an increase in the share of low-income people with health insurance leads to lower rates of Chapter 7 bankruptcy rates.

5 Conclusions

This study investigates whether personal bankruptcy rates decline as more low-income people obtain health insurance by exploiting the Medicaid expansion under the ACA as a source of exogeneous variation. Although the ACA was originally intended to apply to all states, the US Supreme Court decision made it optional for states to expand Medicaid coverage, for which childless adults had been for the most part ineligible in nearly all states. Thus, the Medicaid expansions under the ACA provide plausibly exogenous, quasi-experimental variation in expanding healthcare coverage among low-income people.

This study finds that an increase in the share of low-income people with health insurance may have played a non-negligible role in explaining variation in Chapter 7 personal bankruptcy rates at the county-level and state-level. The finding that the variation in health insurance coverage created by the Medicaid expansion reduced Chapter 7 bankruptcies, but not Chapter 13 bankruptcies, provides additional support for the hypothesis that an increase in health insurance coverage among low-income people reduces medical bankruptcies, as low-income is one of the requirements for filing a Chapter 7 bankruptcy. My primary results are robust to the exclusion of states that had generous Medicaid before the ACA and the inclusion of division-year interaction terms.

Given that (1) previous studies suggest that medical expenses often lead to personal bankruptcies, especially among the uninsured, and (2) Medicaid provides health insurance coverage at no (or very low) cost to the enrollee, the finding that the increase in health insurance coverage brought about by the Medicaid expansion reduced bankruptcy filings is not too surprising. However, this study advances the literature that assess the effects of health insurance on financial health in an important way, as the magnitude of my estimated impacts is substantial. Among seventeen states that expanded Medicaid in January 2014, Chapter 7 bankruptcies per 1000 adults declined from 3.5 in 2014 to 2.4 in 2018, while the share of low-income population with health insurance increased from 63% to 82%. Using the most conservative estimate found above, a back-of-envelope calculation suggests that an increase in the share of insured population might account for more than half of the decline in Chapter 7 bankruptcies during the period 2014–2018 (β = 0.036 with a 19%-points increase in the share of population with health insurance would be ~0.7 Chapter 7 bankruptcy per 1000).

Of course, we need to keep in mind that the estimate found in this study is the local average treatment effect. Because the Medicaid expansion is used as an instrument for health insurance coverage among low-income population, the effect of health insurance is identified in the population of low-income people who reside in expansion states and obtained health insurance after the Medicaid expansion. The 2SLS results may not be generalizable to other subpopulations, i.e., low-income people in non-expansion states, if there is too much heterogeneity among low-income Americans. Nevertheless, as one major reason the ACA was passed was to provide the financial protection from adverse health shocks to those who cannot afford private health insurance, the ACA may have achieved this goal when it comes to personal bankruptcies. Future studies should address whether this beneficial effect of the ACA on financial health among those who gained eligibility is likely to exceed the cost, as Medicaid is funded by taxpayers.

Notes

Legislation enacted in December 2017 effectively repealed that requirement, starting in 2019.

Chapter 7 bankruptcies fell sharply after 2005, before they started increasing in 2007, due to the passage of the Bankruptcy Abuse Prevention and Consumer Protection Act of 2005, which made it more difficult for higher-income individuals to qualify for Chapter 7 bankruptcy by more closely examining the filer’s ability to repay their debts. The law caused many people to file Chapter 7 bankruptcy before October 2005, when most provisions of the act started to apply.

Wing et al. (2018) review difference-in-differences studies and state that “the literature has not reached a consensus on the best way to perform inference in [difference-in-differences] models” (p. 462).

SAHIE’s definition of insured is “Is this person currently covered by any of the following types of health insurance or health coverage plans? (1) Insurance through a current or former employer or union (of this person or another family member), (2) Insurance purchased directly from an insurance company (by this person or another family member), (3) Medicare, for people 65 and older, or people with certain disabilities (SAHIE does not report insurance rates for people over 65 since over 98% of people over the age of 65 are insured), (4) Medicaid, Medical Assistance, or any kind of government-assistance plan for those with low incomes or a disability, (5) TRICARE or other military health care, (6) Indian Health Services, (7) VA health care, and (8) Any other type of health insurance or health coverage plan.”

The SAHIE data are available for six income categories: all incomes, as well as income-to-poverty ratio (IPR) categories 0–138%, 0–200%, 0–250%, 0–400%, and 138–400% of the federal poverty threshold, three sex groups (female, male, both), four race/ethnicity groups (all races, non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic), and six age groups (0–18, under 65, 18–64, 21–64, 40–64, 50–64).

Bankruptcy data from 2010 to 2012 are purchased from Public Access to Court Electronic Records (PACER) at https://pcl-legacy.uscourts.gov/statistics (U.S. Bankruptcy Courts 2019), but they are consistent with the 2013–2018 data.

The data list a small number of filings in the incorrect jurisdiction. Following Hynes (2012), for these cases, I summed the number of bankruptcies for a given county regardless of where the petition was filed.

Most Chapter 13 bankruptcies are dismissed because the debtor fails to satisfy the conditions of the court mandated repayment plan (Lefgren and McIntyre 2009).

It is important to point out that personal bankruptcies are an imperfect measure of financial distress because of the costs. Many people who cannot or will not repay their debts do not file for bankruptcy because of the attorneys’ fees for a bankruptcy filing. According to Foohey et al. (2017), attorneys’ costs are on average $1200, paid up front, to file a Chapter 7 bankruptcy. For a Chapter 13 bankruptcy, debtors typically pay $3200 for attorneys, but these fees are paid over time as a part of the case’s resolution.

All nonelderly adults, whether childless or parents, with incomes up to 100% of the FPL were covered prior to 2014 in Delaware. In Massachusetts, parents with incomes up to 133% of the FPL were eligible for Medicaid, and childless adults with incomes below 100% of the FPL were able to obtain limited coverage under the MassHealth program. New York’s Family Health Plus program covered childless adults with incomes up to 100% of the FPL and parents with incomes up to 150% of the FPL. Vermont Health Access Plan provided coverage to childless adults with incomes up to 150% of the FPL and parents with incomes up to 185% of the FPL.

In California, 48 counties (out of 58) expanded prior to 2014. Of these 48 counties, 10 counties expanded in July 2011, and 38 counties expanded in January 2012 (Caswell and Waidmann 2017). I use January 2012 for California in my state-level analysis, because that is when most counties in California expanded.

New Jersey and Washington were technically early expansion states, but in these states existing enrollees were transferred to new programs, and no new beneficiaries were enrolled prior to 2014 (Sommers et al. 2013).

For my graphing purpose, I exclude states that expanded before and after January 2014, as the implementation dates are not uniform among these early and late expansion states. These excluded early expansion states are California, Connecticut, Minnesota, and the District of Columbia, and late expansion states include Michigan, New Hampshire, Pennsylvania, Indiana, Alaska, Montana, and Louisiana.

My first-stage regression produces essentially difference-in-differences estimates. A major challenge in difference-in-differences analyses is separating out preexisting trends from the effects of a policy shock. Although it is a common practice in difference-in-differences studies to check robustness by including unit-specific time trends, I do not employ specifications with county/state specific time trends in this study. Wolfer (2006) points out that including unit-specific time trends might either exacerbate biases, depending on the specific dynamic response, especially when only a few observations are available before the policy shock. This study covers a short period 2010-2018, and most Medicaid expansions occurred in 2014, leaving only 4 years for the preexisting-trend period. Several researchers also argue that using unit-specific time trends does not always serve as a good robustness check (e.g., Meer and West 2015). Indeed, Borusyak and Jaravel (2017) state that “[they] do not recommend including unit-specific time trends in any difference-in-differences or event study specifications” (p. 17).

New England Division includes Maine, Vermont, New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Connecticut, and Rhode Island; Middle Atlantic Division includes New Jersey, New York, and Pennsylvania; South Atlantic Division includes Maryland, Delaware, West Virginia, Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, Florida, and District of Columbia; East South Central Division includes Kentucky, Tennessee, Alabama, and Mississippi; West South Central Division includes Oklahoma, Arkansas, Texas, and Louisiana; East North Central Division includes Wisconsin, Michigan, Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois; West North Central Division includes North Dakota, South Dakota, Nebraska, Kansas, Missouri, Iowa, and Minnesota; Mountain Division includes Idaho, Montana, Wyoming, Colorado, Utah, Nevada, Arizona, and New Mexico; Pacific Division includes Washington, Oregon, California, Alaska, and Hawaii.

References

Abadie, A., Diamond, A., & Hainmueller, J. (2010). Synthetic control methods for comparative case studies: estimating the effect of California’s tobacco control program. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 105, 493–505.

Bertrand, M., Duflo, E., & Mullainathan, S. (2004). How much should we trust differences-in-differences estimates? Quarterly Journal of Economics, 119(1), 249–75.

Borusyak, K., Jaravel, X. (2017). Revisiting event study designs. Harvard University Working Paper.

Brevoort, K., Grodzicki, D., Hackmann, MB. (2017). Medicaid and Financial Health. NBER Working Paper No. w24002.

Caswell, K. J., & Waidmann, T. A. (2017). The Affordable Care Act Medicaid expansions and personal finance. Medical Care Research and Review. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077558717725164.

Courtemanche, C., Marton, J., Ukert, B., Yelowitz, A., & Zapata, D. (2017). Early impacts of the Affordable Care Act on health insurance coverage in Medicaid expansion and non‐expansion states. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 36(1), 178–210.

Dobkin, C., Finkelstein, A., Kluender, R., & Notowidigdo, M. J. (2018). The economic consequences of hospital admissions. American Economic Review, 108(2), 308–52.

Finkelstein, A., Taubman, S., Wright, B., Bernstein, M., Gruber, J., Newhouse, J. P., Allen, H., & Baicker, K. (2012). The Oregon Health Insurance Experiment: evidence from the first year. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 127(3), 1057–1106.

Foohey, P., Lawless, R., Porter, K., Deborah, T. (2017). “No money down” bankruptcy. Southern California Law Review, 90(5), 1055–1110.

Frean, M., Gruber, J., & Sommers, B. D. (2017). Premium subsidies, the mandate, and Medicaid expansion: coverage effects of the Affordable Care Act. Journal of Health Economics, 53, 72–86.

Gross, T., & Notowidigdo, M. L. (2011). Health insurance and the consumer bankruptcy decision: evidence from expansions of Medicaid. Journal of Public Economics, 95(7), 767–778.

Hu, L., Kaestner, R., Mazumder, B., Miller, S., & Wong, A. (2018). The effect of the affordable care act Medicaid expansions on financial wellbeing. Journal of Public Economics, 163, 99–112.

Hynes, R. M. (2012). Payday lending, bankruptcy, and insolvency. Washington and Lee Law Review, 69(2), 607–648.

Himmelstein, D. U., Thorne, D., Warren, E., & Woolhandler, S. (2009). Medical bankruptcy in the United States, 2007: results of a national study. American Journal of Medicine, 122(8), 741–6.

Kaestner, R., Garrett, B., Gangopadhyaya, A., & Fleming, C. (2017). Effects of Medicaid expansions on health insurance coverage and labor supply. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 36(3), 608–642.

Lefgren, L., & McIntyre, F. (2009). Explaining the puzzle of cross-state differences in bankruptcy rates. The Journal of Law and Economics, 52(2), 367–393.

Kaiser Family Foundation. (2019). Status of state Medicaid expansion decision. Kaiser Family Foundation. http://kff.org/health-reform/state-indicator/state-activity-around-expanding-medicaid-under-the-affordable-care-act.

Mathur, A. (2006). Medical bills and bankruptcy filings. American Enterprise Institute. http://www.aei.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/10/20060719_MedicalBillsAndBankruptcy.pdf.

Mazumder, B., & Miller, S. (2016). The effects of the Massachusetts health reform on household financial distress. American Economic Journal: Economics Policy, 8(3), 284–313.

Meer, J., & West, J. (2015). Effects of the minimum wage on employment dynamics. Journal of Human Resources, 51(2), 500–522.

Miller, S., & Wherry, L. R. (2017). Health and access to care during the first 2 years of the ACA Medicaid expansions. New England Journal of Medicine, 376, 947–956.

Morrison, ER., Uettwiller, A. (2018). Race and bankruptcy. Columbia Law and Economics Working Paper.

Moulton, B. R. (1990). An illustration of a pitfall in estimating the effects of aggregate variables on micro units. Review of Economics and Statistics, 72(2), 334–38.

Slusky D., Ginther D. (2018). Did Medicaid expansion reduce medical divorce? NBER Working Paper No. 23139.

Sommers, B. D., Arntson, E., Kenney, G. M., & Epstein, A. M. (2013). Lessons from early Medicaid expansions under health reform: interviews with Medicaid official. Medicare & Medicaid Research Review, 3(4), E1–E23.

Staiger, D., & Stock, J. H. (1997). Instrumental variables regression with weak instruments. Econometrica, 65(3), 557–586.

The Bureau of Labor Statistics (2019a). Local area unemployment statistics. The Bureau of Labor Statistics. https://www.bls.gov/lau/#cntyaa.

The Bureau of Labor Statistics (2019b). Statewide data, annual average series. Employment status of the civilian noninstitutional population, annual averages. The Bureau of Labor Statistics. https://www.bls.gov/lau/rdscnp16.htm.

U.S. Bankruptcy Courts (2019). Business and Nonbusiness Cases Filed, by Chapter of the Bankruptcy Code, District, and County. 2013–2016. https://www.uscourts.gov/data-table-numbers/f-5a.

U.S. Bankruptcy Courts. (2019). Business and personal cases filed, by chapter of the bankruptcy code, district, and county. 2013-2018. U.S. Bankruptcy Courts. https://www.uscourts.gov/data-table-numbers/f-5a.

U.S. Census Bureau (2019a). Annual county resident population estimates by age, sex, race, and hispanic origin: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2018. U.S. Census Bureau. https://www.census.gov/data/datasets/time-series/demo/popest/2010s-counties-total.html.

U.S. Census Bureau (2019b). Small area income and poverty estimates (SAIPE) program. U.S. Census Bureau. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/saipe/data/datasets.html.

U.S. Census Bureau (2019c). Annual state resident population estimates for 5 race groups by age, sex, and hispanic origin: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2018. U.S. Census Bureau. https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/popest/2010s-state-detail.html.

U.S. Census Bureau (2020). The Small Area Health Insurance Estimates. U.S. Census Bureau. https://www.census.gov/data/datasets/time-series/demo/sahie/estimates-acs.html.

Wherry, L., & Miller, S. (2016). Early coverage, access, utilization, and health effects of the Affordable Care Act Medicaid expansions: a quasi-experimental study. Annals of Internal Medicine, 164(12), 795–803.

Wing, C., Simon, K., & Bello-Gomez, R. A. (2018). Designing difference in difference studies: best practices for public health policy research. Annual Review of Public Health, 39(1), 453–469.

Wolfers, J. (2006). Did unilateral divorce laws raise divorce rates? A reconciliation and new results. American Economic Review, 96(5), 1802–20.

Acknowledgements

The author is grateful to two anonymous referees for their useful comments and suggestions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The author declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Timing of Medicaid expansion by state, 2010–2018. Most California counties expanded before 2014. New York, Vermont, Massachusetts, and Delaware have adopted Medicaid expansion under the Affordable Care Act but will be treated as control states due to their generous eligibility levels prior to the ACA Medicaid expansion

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kuroki, M. The effect of health insurance coverage on personal bankruptcy: evidence from the Medicaid expansion. Rev Econ Household 19, 429–451 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-020-09492-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-020-09492-0