Abstract

Using the Survey of Income and Program Participation from 2001, 2004, and 2008 and federal and state variation in earned income tax credit generosity over time, I investigate how changes in expected household earned income tax credit benefits associated with marriage affect cohabitation and marriage behavior among low-income single mothers. I simulate a marriage market to predict potential spouse earnings for a sample of single mothers in order to estimate the potential losses or gains in earned income tax credit benefits upon marriage. Using multinomial logistic regressions, I then analyze how the anticipated loss in earned income tax credit benefits upon marriage affects the likelihood of marrying or cohabiting. Results suggest that the average earned income tax credit-eligible woman can expect to lose approximately US$1,300 in earned income tax credit benefits in the year following marriage, or about half of pre-marriage benefits. Single mothers who expect to lose earned income tax credit benefits upon marriage are 2.5 percentage points less likely to marry their partners and 2.5 percentage points more likely to cohabit compared to single mothers who expect no change or to gain earned income tax credit benefits upon marriage. Despite recent policy efforts to reduce the size of the marriage penalty embedded in the earned income tax credit structure, these results suggest that the earned income tax credit still creates distortions in marriage and cohabitation decisions among low-income single mothers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The earned income tax credit (EITC) has become the largest cash transfer program in the United States, distributing over $60 billion dollars in benefits in recent years (Tax Policy Center 2011). In 2014, the maximum federal benefit for a household with three children was $6,143, which represents up to 45 % of household earnings among recipients. Cohabitation rates have also increased sharply over the last decade and have become less and less associated with marriage, particularly among the low-income population (Bumpass and Lu 2000; Kennedy and Bumpass 2011; Lichter et al. 2006). The expansion of the EITC over this time period may have played a role in the rise of cohabitation. Since the EITC is based on family earnings, it may discourage marriage for many dual-earner households, while encouraging traditional, single-breadwinner families.Footnote 1 While policy efforts have been made in recent years to eliminate the marriage penalty from the EITC by increasing the earnings thresholds for married couples, the current policy retains elements that create distortive incentives for marriage.

There has been a considerable amount of research analyzing how welfare benefits affect marriage decisions (Bitler et al. 2004; Grogger and Bronars 2001; Moffitt 1998), and how the tax structure more broadly incentivizes or discourages marriage (e.g., Alm et al. 1999; Alm and Whittington 2003). Many of these studies find either no effect or only modest impacts of welfare benefits and tax penalties on marriage. Others have studied the impact of the EITC on marriage and divorce (Dickert-Conlin and Houser 2002; Eissa and Hoynes 2000; Ellwood 2000; Fisher 2013; Herbst 2011), generally finding modest, negative effects on marriage.

In this analysis, I investigate how the EITC has impacted marriage and cohabitation among low-income single mothers, making the following contributions to the literature. First, this analysis adds to the literature on the EITC and family structure by quantifying the expected gains and losses in EITC benefits upon marriage for a sample of single mothers. Much of the EITC literature on this topic evaluates a marriage penalty for a sample of individuals already cohabiting or married, excluding single, non-cohabiting individuals. This paper is the first in the EITC literature to estimate a potential loss or gain in EITC benefits for individuals not currently cohabiting or married, providing the first descriptive picture of the distribution of expected gains or losses in EITC benefits associated with marriage for low-income single mothers. The federal policy changes to the EITC benefit structure over this time period provide variation for illustrating how the marriage penalty has changed over time.

Second, much of the previous work examining the impact of the EITC on marriage decisions either does not take into account the heterogeneity in the penalties or subsidies associated with the EITC, or measures these penalties after coresidential decisions have already been made, raising concerns of endogeneity of labor market decisions to marriage and cohabitation decisions. This analysis expands on prior work by simulating a marriage market to generate exogenous variation in spouse earnings in order to estimate potential gains or losses in EITC benefits associated with marriage. This method is advantageous in that earnings are evaluated prior to marriage and cohabitation decisions, reducing concerns of endogeneity of earnings with respect to coresidential decisions.

Third, with the exception of Dickert-Conlin and Houser (2002), which was based on data prior to the expansions of the EITC for married couples, many of the recent analyses of the marriage disincentives associated with the EITC estimate the impact of the EITC on the stock of existing marriages (Eissa and Hoynes 2000; Fisher 2013; Herbst 2011). Measuring the stock of marriages rather than transitions into marriage could bias estimates of the impact of the EITC on marriage decisions if households simultaneously make marriage decisions and adjust their earnings to minimize household tax burden. Using panel data, I estimate the impact of the EITC on transitions into marriage and cohabitation. This allows for a clean identification of how tax incentives affect family formation decisions because policy changes and household earnings are measured prior to the marriage decision.

Finally, this analysis builds on prior work by incorporating several different exogenous sources of variation in determining whether a single mother can expect to gain or lose EITC benefits upon marriage. The first source of variation comes from the random spouse match, which generates random variation in the earnings of potential spouses that is exogenous to single mother’s own earnings. Second, I incorporate exogenous variation generated by several federal policy changes to the EITC over the last decade that have affected the size and the likelihood of experiencing a marriage penalty. Finally, there have also been several states that have introduced their own EITCs over this time period, which also vary in generosity both across and within states over time. This variation will also lead to exogenous variation in the size of the expected loss in EITC benefits, and will amplify the effects of federal policy changes. Through these different sources of variation, this paper provides updated estimates on how policy-induced changes to the EITC affect marriage and cohabitation rates of low-income, single mothers.

To conduct this analysis, I first simulate a marriage market to predict the earnings of potential spouses using data on single men and women from the 2001, 2004, and 2008 Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP). Based on the matches made in this simulated marriage market, I calculate the expected household EITC within and outside of marriage for this hypothetical couple using federal and state tax laws. I then illustrate how federal and state policy changes to the EITC schedule for married couples have affected the marriage penalty in recent years. I use multinomial logistic regressions to analyze the effect of an expected loss or gain in EITC benefits upon marriage, on decisions for single mothers to cohabit or marry during the SIPP survey. I then conduct several alternate specifications of the expected loss function as well as alternate specifications of potential spouse earnings to further identify the population most likely to respond to expected losses in EITC benefits upon marriage.

Results from the simulated marriage market suggest that the average EITC-eligible single mother can expect to lose approximately $1300 in EITC benefits upon marriage, about 40 % of pre-marriage EITC benefits. The likelihood of losing benefits upon marriage, as well as the size of the marriage penalty have decreased in recent years due to the federal expansions to the EITC benefit schedule for married couples. In my sample, the marriage penalty declined from an average loss of $1600 in 2001 to $745 in 2009 (2014$). Single mothers who expect to lose benefits upon marriage are 2.5 percentage points less likely to marry their partners, and 2.5 percentage points more likely to cohabit with their partners compared to women who do not face a marriage penalty associated with the EITC. Results are concentrated among the least educated single mothers, as well as underrepresented minorities. These results suggest that the EITC affects the marriage and cohabitation decisions of low-income single mothers, contributing to the divergence in marriage and cohabitation patterns between low-income and higher-income women in the United States.

2 EITC

2.1 Background on the EITC

The EITC benefit structure is made up of three segments—a phase-in, a plateau, and a phase-out region. For a household with two children in the phase-in region, every dollar of earned income increases the EITC benefit by 40 cents. Once earnings reach a certain threshold, benefits remain constant until earned income reaches a second threshold, at which point benefits are phased out at approximately 20 cents for each additional dollar of earnings. Figure 1 illustrates the federal EITC benefit structure for the 2014 tax year. The solid lines indicate the benefit structure for an unmarried tax payer, while the dotted lines illustrate the structure for a married couple. Beginning in 2002, the plateau region of the benefit structure was extended for married couples in an effort to reduce the marriage penalty associated with the EITC. In 2002, the plateau region was extended for an extra $1000 for married couples and by 2014, married couples could earn an extra $5430 before the phase-out took effect. These changes in the benefit structure for married couples provide one source of exogenous variation used in this analysis.

In addition to the federal EITC, several states provide supplemental EITCs that are calculated as a percent of the federal EITC, ranging from 3–45 % of the federal EITC. A list of states that had implemented EITCs by 2009, along with information on when they implemented the EITC and the generosity of the EITC in 2001 and 2009 can be found in Supplementary appendix Table A1. This table illustrates the variation in when states implemented credits along with the variation in the generosity of these credits both across states and within states over time. State EITCs provide another source of variation for this analysis, as the federal policy changes to the benefit structure for married couples over the last decade will be amplified for individuals living in states with their own EITCs.

2.2 Marriage incentives and the EITC

Since EITC benefits are based on household-level earnings, the EITC benefit structure creates marriage distortions. Since the benefit structure is non-linear, these distortions are also non-linear. Working single mothers may have an incentive to remain single if their potential spouses’ earnings would reduce EITC benefits or render them ineligible entirely. In contrast, non-working single mothers may have incentives to marry working partners in order to receive benefits. To illustrate, a single mother with two children earning $13,000 in 2014 (roughly full-time employment at the minimum wage) is eligible for an EITC benefit of $5200. A single, childless man earning $13,000 is not eligible for the EITC. If she marries this single man, bringing their total family income to $26,000, their household benefit falls slightly to $4882—a loss of $318. This same hypothetical couple would be penalized to a much greater extent under the 2001 laws than the 2014 laws. In 2001, the benefit structure for a head of household filer was the same for a married couple. This same single mother in 2001 would be eligible for an EITC of about $5358 (2014$) if she remained single, but her EITC would fall to $0 were she to marry. Under this scenario, the couple might choose to remain unmarried in order to collect the higher benefit and still share income.

Not all couples would lose their EITC benefits were they to marry—many could actually receive a larger EITC within marriage than if they were to remain unmarried. For example, a non-working single mother with two children would receive a $5200 EITC by marrying a single man earning $13,000. In fact, many women located on the phase-in portion of the benefit structure could receive higher EITC benefits were they to marry their partners than if they remained unmarried. In this way, the EITC creates different incentives for individuals to marry or remain unmarried depending on where they lie on the benefit structure and what their potential spouses earn. Because of this, women of similar earnings levels may be eligible for very different EITC benefits within marriage based on the earnings of their potential spouses, the state they reside in, and the tax year.

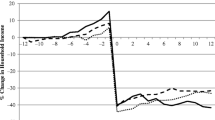

Figure 2 illustrates how the marriage penalty has changed for these two hypothetical couples since 2000 for the federal benefit as well as a few select states that offer their own EITCs: New York, Iowa, and Michigan. New York has a fairly generous state EITC, worth 30 % of the federal benefit in recent years. Iowa has also had a state EITC over this entire time period, but is worth only 7 % of the federal benefit. Michigan did not have a state EITC until 2008, and subsequently made several changes to the credit. Michigan’s EITC was initially worth 10 % of the federal benefit in 2008, rose to 20 % of the federal benefit in 2009, and then fell to 6 % of the federal benefit by 2012.

Panel A of Fig. 2 illustrates how the marriage penalty has changed over time for a dual-earner household where each individual earns $13,000.Footnote 2 The black, solid line shows the size of the expected change in the federal benefit, which represents the size of the loss or gain for individuals living in states without EITCs. In 2000, a dual-earner household with two children where each partner earns $13,000 would experience a loss of $5200 in EITC benefits were they to marry rather than cohabit and file taxes separately. This loss would have been exacerbated if the couple lived in New York, where the same hypothetical couple would lose $6400 in EITC benefits upon marriage. Couples would also experience a larger marriage penalty in Iowa, losing approximately $5600. Couples in Michigan would experience the same loss as those in states without EITCs since Michigan did not have an EITC in 2000. The size of the marriage penalty falls steadily over the next 14 years, and by 2014, dual-earner households with two children earning $13,000 each would only lose about $300 by marrying.

For a single mother with two children and no earnings, marrying a single man who earns $13,000 (2014$) would increase the household EITC. These gains have increased over time with the reduction in the marriage penalty through the federal policy changes over the last decade (see panel B). In 2000, this hypothetical couple would have gained $3800 (2014$) in federal EITC benefits if they resided in a state with no EITC. In a state like New York, with a generous EITC, this couple would gain $4700 in benefits upon marriage. By 2014, this couple would gain $5200 in EITC benefits if they lived in a state with no EITC, and $6700 if they lived in New York.

Not only does the magnitude of the marriage penalty change over time, but some couples who would have faced a loss under the 2001 laws would face no change or a marriage bonus under the 2014 laws. Panel C of Fig. 2 illustrates how the federal marriage penalty changes over time for a single mother earning $13,000 matched to a spouse earning either $1000, $5000, or $10,000. While the magnitude of the marriage penalty falls steeply for all spouse earnings thresholds, all the hypothetical couples presented in panel C would face a penalty under the 2000 laws, but either no change or a slight marriage bonus under the 2014 laws. This figure illustrates the substantial variation in the size and presence of the marriage penalty associated with the EITC both over time as well as across states.

3 Previous literature

The traditional economic framework for analyzing marriage behavior began with the Becker model in 1974. Under the Becker (1974) model, individuals choose to marry if their utility within marriage exceeds their utility outside of marriage. If two individuals are able to combine their resources and improve the total wellbeing of the household, then these two individuals marry.

The EITC could have an impact on the decision to marry or cohabit, particularly among low-income individuals. If two working individuals can enjoy the same benefits within cohabitation as in marriage, they may choose not to marry if marrying reduces their household EITC benefit. This assumes that cohabitation can be viewed as a substitute for marriage—that individuals can enjoy similar benefits within cohabitation as in marriage. This may be true for couples who risk losing social benefits, such as the EITC or temporary assistance for needy families (TANF), if they were to marry but also depends on differences in how finances are shared within marriage versus cohabitation. The literature on this topic is somewhat mixed, but most studies find some degree of income and expense pooling within cohabiting couples, though generally lower levels of resource pooling than for married couples (DeLeire and Kalil 2005; Kenney 2004; Oropesa et al. 2003).Footnote 3

While there have been several papers examining how the EITC affects marriage, findings are somewhat inconsistent. Some papers find little or no effect of the EITC on marriage (Dickert-Conlin and Houser 2002; Ellwood 2000). Some find effects for divorce but not marriage (Dickert-Conlin and Houser 2002), while others find effects on marriage but not divorce (Herbst 2011). Dickert-Conlin and Houser (2002) find effects are larger for married couples with children, while Eissa and Hoynes (2000) find larger effects among unmarried, childless couples. The empirical strategies also differ, with some analyses focusing on the overall generosity of the EITC (Dickert-Conlin and Houser 2002; Herbst 2011), while others calculate an individual-specific marriage penalty (Eissa and Hoynes 2000; Fisher 2013). With the exception of Dickert-Conlin and Houser (2002) and Ellwood (2000), all of these studies use cross-sectional data to analyze the stock of marriages as a function of EITC generosity, but are unable to observe couples’ transitions into marriage. This may be of particular concern in calculating the marriage penalty associated with the EITC if earnings are only measured after the union formation. Couples may simultaneously make decisions about labor force participation, cohabitation, and marriage leading to potentially biased estimates of the marriage penalty.

There has been some qualitative work examining the relationship between the EITC and marriage decisions (Tach and Halpern-Meekin 2013). This work suggests that while individuals do have some understanding of how the size of their EITC is affected by their marriage and childbearing decisions, most individuals expressed that they would not alter their living situation solely because of their EITC benefits. This work was based on a small sample of 115 individuals living in the Boston, Massachusetts area and therefore does not represent the national population of individuals who receive the EITC. Further, while individuals may not explicitly state that the EITC affects their marriage and cohabitation decisions, the incentives in the program structure may still affect behavior of the marginal recipient.

The EITC may also have an impact on marriage and cohabitation decisions through indirect channels. The EITC has been shown to have a positive impact on labor supply, particularly among single mothers (Ellwood 2000; Meyer and Rosenbaum 2001). This could in turn affect marriage decisions—if single mothers enter the labor force and find stable employment, they may be less likely to marry partners out of financial necessity. In particular, policy-induced expansions to the EITC may increase the propensity to work among single mothers, which may in turn decrease the propensity to marry. The EITC may also impact marriage and cohabitation through childbearing decisions. The expansions to the EITC over the last several decades, particularly for households with multiple children, may encourage women to have more children, which may also affect their decisions to marry and cohabit. Limited research on this topic suggests little impact of the EITC on fertility (Baughman and Dickert-Conlin 2009). In the analysis, I will test the robustness of results to the inclusion of baseline earnings controls and fixed effects for the number of children residing in the household. These controls will shed light on the extent to which marriage and cohabitation results are driven by changes in labor supply or childbearing.

4 Data

Data come from the 2001, 2004, and 2008 SIPP, a nationally representative survey of 36,700 households in 2001, 46,500 households in 2004, and 52,000 households in 2008. The data contain detailed information regarding income from various sources for each individual residing in the household. The data are also longitudinal, following individuals for 36 months in 2001, 48 months in 2004, and 60 months in 2008. Its large sample size, coupled with detailed information on earnings and household structure make the SIPP an ideal data source for analyzing marriage and cohabitation behavior in the context of the EITC.

I restrict the sample to women between the ages of 18 and 50 at the start of the SIPP survey who met all of the following characteristics (evaluated at the start of the survey): were the respondent of the household, had at least one child under the age of 19Footnote 4, were unmarried, had less than a college degree, and were eligible for the EITC based on their earnings in the first calendar year of the SIPP survey. These restrictions were meant to limit the sample to those most likely to be affected by incentives in the EITC and resulted in a sample size of 4783 individuals across the three panels. While previous literature on the EITC tends to limit the sample of interest to those without a high school degree, I include those with a high school degree or some college experience since approximately two-thirds of single mothers with a high school degree or some college were eligible for the EITC.Footnote 5

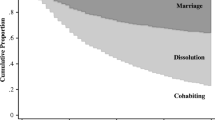

I then evaluate whether single mothers transition into either a cohabiting relationship or a marriage at any point during the survey window. No restrictions are made on whether the respondent remains in the survey for the entire panel or when the marriage or cohabitation occurs. Sample attrition does not affect whether an individual is included in the analysis; marital or cohabiting status is evaluated for the months when the individual is in the survey. No restrictions are made on whom the respondent marries—whether she marries the biological father of the children in the household or someone biologically unrelated to the children. As a robustness check, I excluded single mothers who partnered with (either cohabited or married) the biological father of any of the children in the household, as these decisions are likely different than decisions to partner with someone unrelated to the children in the household. Results are quite similar and presented in Supplementary appendix Table A3.Footnote 6 The outcome of interest, whether a single mother cohabits or marries at any point during the survey, is categorized into three groups: single (not cohabiting), cohabiting, or married. Each respondent contributes one observation to the analysis; background characteristics are measured at the start of the survey.

Using information about earnings in the first calendar year of the SIPP survey, I calculate the federal and state EITC the respondent expects to receive given her earnings and the number of qualifying children residing in the household in the first month of the survey using NBER’s TAXSIM model, assuming the single mother claims head of household status and takes the standard deduction.Footnote 7 After conducting the simulated marriage market (discussed in detail below), I compare the household EITC benefits of the recipient if she were to remain single to that if she were to marry and file her taxes jointly with her spouse. Respondents are then characterized into two groups: those who expect to lose benefits upon marriage and those who expect no change or to gain benefits upon marriage.Footnote 8

In addition to the primary covariate of interest, expectations to lose EITC benefits upon marriage, I also control for baseline earnings, race, a quadratic form of age, number of children living in the household, whether the individual was previously married, and whether the individual had any health insurance during the first year of the SIPP survey. Women who have never been married before may have unobservable characteristics that make them less likely to marry at all. Women who lack health insurance (either through their employers or through Medicaid) may be more likely to marry in order to gain health insurance coverage from a spouse.

When making marriage and cohabitation decisions, couples may also consider whether they will lose other forms of public assistance upon marriage. If expected EITC losses are correlated with receipt of other forms of public assistance, this would lead to an overestimation of the impact of the EITC on marriage and cohabitation decisions. To address this concern, I also control for whether the respondent reported receiving other benefits such as food stamps, welfare (TANF), or child support in the first month of the SIPP survey. All of these controls reflect receipt of benefits and cannot account for whether a respondent is eligible for one of these programs but does not report receiving benefits.

5 Empirical strategy

5.1 Predicting potential spouse income

Estimating the potential losses or gains in household EITC benefits associated with marriage requires estimating the earnings of the potential spouse. For the majority of the sample, spouse earnings are unobservable because individuals do not cohabit or marry during the survey window. For individuals who do cohabit or marry, there may be concern that couples adjust their labor force participation in response to the union formation, and thus any calculation of a loss or gain in the household EITC will reflect these post-coresidential labor force decisions. To address both of these concerns, I simulate a marriage market for all individuals in the sample, regardless of whether a partner is observed at any point in the survey. This reduces concerns of measuring spouse earnings after the marriage or cohabitation decision and also allows for calculation of the loss or gain in EITC benefits upon marriage for individuals who are never observed living with a partner during the survey window.

I employ a similar strategy to that used by Bertrand et al. (2013), where separate marriage markets are constructed based on the race, age, and education of the individuals in the sample and couples are randomly matched based on these demographic characteristics. I divide all single mothers in the SIPP into four race categories: white, black, Hispanic, and Asian; three education categories: less than high school degree, high school degree, and some college; and five age categories: 19–24, 25–29, 30–34, 35–39, and 40–50. I then randomly match each single mother to a single man in the same SIPP panel with the same age-race-education combination using a uniform random-number generator. I restrict the spouse match within panel such that women in each panel of the SIPP only match to men in their same panel to provide a more accurate representation of the marriage market and earnings distribution in a given year.Footnote 9 Results are not sensitive to this particular specification of the marriage market. Similar results were obtained when calculating the average spouse earnings within an age-race-education cell and estimating the marriage penalty based on this average of all potential spouse earnings.Footnote 10 The method employed here using a single spouse match generates larger variation in potential spouse earnings, thus providing more precise estimates. A kernel density representing the distribution of the number of men in each age-race-education-SIPP panel combination is shown in Supplementary appendix Fig. A1. The average number of single men in each cell was approximately 224; the average single man in the SIPP was matched to a single woman 1.38 times.

After conducting the spouse match, I then calculated a potential household EITC benefit within marriage for each match and quantified the expected loss or gain in EITC benefits upon marriage compared to the EITC benefit each single mother could expect to receive were she not married using federal and state EITC rules in each year. A kernel density of the expected change in EITC benefits upon marriage is shown in Fig. 3, which shows the difference between the household federal and state EITC benefit if the woman remained single and the household EITC benefit if the woman married her potential spouse. Positive numbers indicate that the EITC benefit when remaining single is higher than the benefit when married. The average change in EITC benefits upon marriage is a $1296 (2014$) loss in benefits, with some individuals in the sample losing over $6000 in EITC benefits upon marriage and a few individuals gaining $6000 in EITC benefits upon marriage. Approximately 60 % of single mothers in the sample would lose some of their EITC benefits upon marriage, while 20 % of single mothers would gain EITC benefits upon marriage.

Kernel density of expected change in EITC benefits upon marriage among EITC-eligible women (in thousands of 2014$). Source 2001, 2004, and 2008 SIPP. Single mothers with less than a college degree, eligible for the EITC in the first year of the survey, aged 18–50. Note Positive values correspond to higher benefits while single than while married (an expected loss in EITC benefits upon marriage). Negative values correspond to higher EITC benefits under marriage. Expected change in benefits measured in thousands of 2014$

5.2 Validation of spouse match

Identifying whether individuals can expect to gain or lose EITC benefits upon marriage partially relies on the quality of the spouse match. The average woman in the sample is matched to a potential spouse that earns approximately $24,000, while the average actual spouse earnings among women who married or cohabited with their partners was $18,000. To further check the quality of the matches made in the simulated marriage market, Supplementary appendix Fig. A2 compares the earnings distributions of the predicted spouses to the actual spouses or partners for the women in the sample who cohabit or marry. In all but the 70th and 80th percentiles of the earnings distribution, there are no significant differences between the earnings using the simulated marriage market and the earnings of the actual partners, suggesting that the simulated marriage market does an accurate job of predicting the expected spouse earnings upon marriage, at least for those observed marrying or cohabiting by the end of the SIPP survey. In the alternate specifications section, I test the robustness of results to different specifications of the spouse match.

5.3 Multinomial logistic regression

After assessing the change in EITC benefits upon marriage, I next use multinomial logistic regressionsFootnote 11 to estimate the likelihood of transitioning into cohabitation or marriage at some point throughout the survey window.Footnote 12 The conditional probability of marrying or cohabiting is modeled as:

where k represents the outcomes of interest, cohabiting or married, β 1k is the outcome-specific coefficient on the EITC variable of interest—a binary indicator for whether the respondent expects to lose benefits upon marriage (ΔEITC). X is a vector of personal characteristics including baseline earnings, education, race, a quadratic form of age, and receipt of other forms of assistance. Z st is a set of state-year level controls such as the top income tax bracket, the state unemployment rate, state GDP, and the maximum potential welfare benefit in each state-year. These control for other state-year factors that might be correlated with EITC losses and influence marriage and cohabitation rates in a state. θ c is a set of number of children fixed effects, intended to control for different propensities to marry or cohabit by the number of children residing in the household. γ s is a set of state fixed effects to control for state time-invariant factors that may influence marriage and cohabitation patterns across states. α t is a set of year fixed effects, which control for any differences in propensity to marry or cohabit across the three SIPP panels. These fixed effects control for time trends in marriage and cohabitation propensities that occur at the national level, such as a general increase in cohabitation rates across the country over time. Year fixed effects also account for the differential duration of the SIPP survey windows across panels. In 2001, for instance, respondents were followed for 36 months while respondents were followed for 60 months in 2008. As a robustness check, I restricted the sample window to 36 months for all three SIPP panels. Results are similar and presented in Supplementary appendix Table A4.Footnote 13

Variation in whether the respondent can expect to lose EITC benefits upon marriage comes from several sources, some of which may be endogenous to the marriage decision, while others are policy-driven and are plausibly exogenous to individual marriage decisions. The first is through the spouse match, where respondents are randomly matched to single men based on the race, age, and education of both the respondent and the spouse within a given panel. I control for these demographic characteristics in the analyses, so variation in expected spouse earnings will be driven by the random matching conducted in the spouse match within each age-race-education cell.

Second, the respondent’s characteristics will affect whether she expects to gain or lose EITC benefits upon marriage. Namely, a respondent’s earnings and the number of children she has will affect her positioning on the EITC benefit schedule, which will in turn affect whether she will gain or lose benefits upon marriage. A high-earning respondent may be less likely to marry because she has stable employment and does not need to marry or cohabit out of financial necessity. Because respondent earnings are also correlated with propensity to lose EITC benefits upon marriage, failing to control for earnings will confound my ability to determine whether the EITC loss itself is what is affecting marriage rates. In the main specification, I include controls for respondent’s baseline earnings (measured in the first year of the SIPP survey) and the number of children residing in the household to control for these factors.

Finally, there have been federal and state policy changes to the EITC benefit structure over the observed time period that generate potentially exogenous variation in whether the respondent can expect to lose EITC benefits. Starting in 2002, the EITC benefit structure was expanded to allow married couples to earn more than single individuals and maintain the same EITC. In 2001, there was no extra allowance for married couples, in 2004 there was a $1000 allowance for married couples before benefits were phased out, and in 2009 married couples could earn $5000 more than single filers before their benefits were phased out.

In addition to the federal policy changes, several states have implemented their own EITCs over this time period, providing an additional source of potentially exogenous variation in expected EITC losses. Because state EITCs are based on the federal EITC, if individuals expect a reduction in their federal EITC upon marriage, they will also experience a reduction in their state EITC benefit. States that implement EITCs may be fundamentally different than states that do not have EITCs, which may confound the relationship between state EITC policies and marriage and cohabitation patterns. I address these concerns by including state fixed effects in the main specification. I am able to incorporate state fixed effects along with the specific state tax rules to calculate expected EITC losses because there is variation both in the generosity of state EITCs and the timing of when states implemented EITCs. Additionally, many states change the generosity of their EITCs over time. With state fixed effects in the model, variation in expectations to lose EITC benefits upon marriage is identified off of within-state changes to both the federal and state EITC policies over time.

5.4 Summary statistics

Summary statistics are shown in Table 1, illustrating differences in characteristics between those who expect to lose benefits, gain benefits, or experience no change in benefits upon marriage based on the simulated marriage market. Underlined terms indicate significant differences between those who expect to lose EITC benefits and those who expect to gain benefits upon marriage. Consistent with predictions that losses in EITC benefits upon marriage should deter marriage, marriage rates are significantly lower among those who expect to lose EITC benefits upon marriage compared to those who gain benefits (13 % compared to 16 %), and cohabitation rates are slightly higher (10 % compared to 9 %). Among those who lose EITC benefits upon marriage, the average loss in benefits was $2500, or about three-quarters of pre-marriage EITC benefits. Those who expect to gain EITC benefits upon marriage had significantly lower earnings than those who lose benefits ($3600 in earnings compared to $17,000), which would place them on the phase-in portion of the EITC benefit schedule. These women would experience an approximate 70 % increase in their EITC benefits were they to marry, increasing their EITC benefits from $2000 to $3500.

Demographic differences are also apparent between individuals expecting to lose benefits and those expecting to gain benefits upon marriage. Individuals who expect to lose EITC benefits upon marriage are significantly more likely to have a high school diploma or some college, have fewer children, and are less likely to receive other public assistance compared to women who expect no change or an increase in EITC benefits upon marriage.

5.5 How does the marriage penalty change over time?

To illustrate how the marriage penalty has changed over time due to federal policy changes, Table 2 presents descriptive statistics on EITC benefits separately for each of the three SIPP panels. Marriage penalties are expected to be largest in the 2001 SIPP and smallest in the 2008 SIPP. This is evident in comparing trends across the three SIPP panels. In the 2001 panel, 72 % of single mothers expected to lose EITC benefits upon marriage, while just over half of single mothers in the 2008 panel expected to lose benefits (54 %). The size of the expected marriage penalty was also smaller in the 2008 panel compared to the 2001 panel: $744 compared to $1623 (2014$). This is despite the fact that single mothers were eligible for similar EITC benefits in all three panels (approximately $3000), had similar earnings levels (about $14,000), and were matched to similarly-earning spouses (average combined respondent and spouse earnings of approximately $35,000 in all three panels).

Summing up the total expected losses in EITC benefits over the course of each of the three SIPP panels, single mothers in the 2001 SIPP could expect to lose $4000 in EITC benefits over three years, while those in the 2004 SIPP could expect to lose $3500 in benefits, and those in the 2008 panel could expect to lose $2000 over the course of three years. While changes to the EITC benefit structure over this time period substantially reduced the size of the marriage penalty associated with the EITC, a significant penalty still exists for many low-income, single mothers. I next examine how these marriage penalties affect transitions into marriage and cohabitation.

6 Results

Table 3 presents results from the multinomial logistic regressions predicting decisions to remain single, cohabit, or marry as a function of expected losses in EITC benefits upon marriage. All models use the sample of women who remain single throughout the survey as the reference category; standard errors are clustered at the state level. All values reported are average marginal effects, which are calculated at the mean for continuous variables. For indicator variables, the coefficient represents the discrete change in the outcome when the indicator variable increases from 0 to 1. The first model uses only an indicator for whether the respondent expects to lose EITC benefits upon marriage based on the simulated marriage market. Variation in the expectation to lose benefits upon marriage is generated by respondent characteristics, potential spouse earnings, federal variation in the marriage penalty over time, and state variation in EITC generosity. With no other controls included, those who expect to lose benefits upon marriage are 1 percentage point less likely to marry and 1.4 percentage points more likely to cohabit by the end of the survey, though the latter term is insignificant at conventional levels.

Model 2 includes demographic controls, controls for respondent earnings at the start of the SIPP panel, potential spouse earnings, and child fixed effects. With these controls, variation in the expectations to lose EITC benefits upon marriage is driven by federal changes to the EITC over time as well as variation in EITC generosity across and within states over time. After including these demographic controls, single mothers who expect to lose benefits are 2.3 percentage points more likely to cohabit and 3.1 percentage points less likely to marry throughout the SIPP panel compared to those who expect no change or to gain benefits upon marriage.

Spouse earnings have a slight positive association with marriage—a $1,000 increase in spouse earnings increases one’s likelihood of marrying by 0.1 percentage points. This suggests that potential losses in EITC benefits upon marriage are partially offset by increases in household earnings, though this relationship is only marginally significant. In contrast, potential spouse earnings have no clear association with the propensity to cohabit. This supports findings that low-income women look for men with stable jobs and financial stability when choosing marriage partners (Edin and Kefalas 2005) and that these characteristics are not a necessary condition to cohabit with a partner (Edin 2000; Smock et al. 2005).

Demographic controls perform as expected—women with no college experience are significantly more likely to cohabit and less likely to marry compared to women with some college. Black women are significantly less likely to marry and cohabit than white women, and Hispanic women are less likely to cohabit than white women. Women who have never been married before are nearly 7 percentage points less likely to marry and 6 percentage points more likely to cohabit compared to women who had been married before.

Receiving other forms of financial assistance is negatively associated with transitions into cohabitation but not marriage. Women who receive food stamps are 4 percentage points less likely to cohabit; those who receive child support are 2 percentage points less likely to cohabit. These forms of assistance may afford single mothers the ability to live on their own rather than with a romantic partner out of financial necessity. State-year controls are associated with transitions into marriage. Higher state top tax brackets are associated with lower marriage rates; we might expect this pattern if high top tax brackets are also correlated with larger marriage penalties in the tax code.

Finally, in the fully specified model (model 3), I include state and year fixed effects. With state and year fixed effects in the model, variation in the expectation to lose EITC benefits upon marriage is driven by within-state policy changes to the EITC over time. Results are qualitatively very similar to those presented in model 2. Those who expect to lose benefits upon marriage are 2.5 percentage points more likely to cohabit and 2.7 percentage points less likely to marry compared to those who expect no change or a gain in EITC benefits upon marriage. These results provide evidence that low-income single mothers do respond to financial incentives associated with the EITC benefit structure in their marriage and cohabitation decisions. I next test the robustness of these findings for different subgroups, different specifications of the expected loss function, and different assumptions regarding the spouse match.

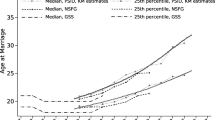

6.1 Subgroup analysis

I next examine heterogeneous effects by educational attainment, race, and prior marital status (see Table 4). Each row of Table 4 represents a separate regression conducted on the subgroup of interest. All models represent the full specification from model 3 of Table 3. The first panel of Table 4 replicates the results presented in model 3 of Table 3. The second panel of Table 4 illustrates how results differ by educational attainment. Results are strongest among respondents with a high school degree or less, who are most likely to receive the EITC. Those with less than a high school degree who expect to lose EITC benefits upon marriage are 10 percentage points less likely to marry and 4 percentage points more likely to cohabit relative to those who expect no change or to gain benefits upon marriage. Those who have completed a high school degree are also quite responsive to expected changes in EITC benefits upon marriage: those who expect to lose benefits are 4 percentage points less likely to marry and 4 percentage points more likely to cohabit relative to high school graduates who expect no change or to gain benefits upon marriage. I find no significant effects among those with some college. While there is a significant association between expectations to lose EITC benefits upon marriage and marriage decisions among college graduates, there are very few single mothers with college degrees who are eligible for the EITC; results should be interpreted with caution for this group.

Analyzing results by race or ethnic origin, Hispanic women are the most responsive to the marriage disincentives associated with the EITC. Hispanic women who expect to lose benefits upon marriage are 7 percentage points less likely to marry and 3 percentage points more likely to cohabit relative to those who expect no change or to gain benefits upon marriage. White women are also less likely to marry when they expect to lose benefits upon marriage. Black women do not appear to base their marriage decisions on expected changes in EITC benefits upon marriage, though they are 2 percentage points more likely to cohabit when they expect to lose EITC benefits upon marriage compared to those who expect no change or to gain benefits upon marriage.

I also examine whether results differ for women who have never been married and those who had been married before. Marriage effects are concentrated among women who were never married before. Cohabitation effects are present among both women who have never been married and those who had, though results are only marginally significant for women who had previously been married.

6.2 Alternate specifications of the loss function

The analysis thus far has utilized a dichotomous indicator for whether the respondent expects to lose any EITC benefits upon marriage to evaluate whether expected losses in EITC benefits impact marriage and cohabitation decisions. As depicted in Fig. 3, however, there is quite a bit of variation in how much respondents expect to gain or lose in EITC benefits. In this next section, I explore different specifications of the expected loss function on marriage and cohabitation patterns by including a linear specification of the dollar amount of the expected loss in EITC benefits, modeling the expected loss in quintiles, and using a dichotomous indicator for whether a respondent expects to lose at least $500 or at least $1000.

I first examine whether the dollar amount of the expected loss in EITC benefits affects marriage and cohabitation decisions. Table 5 presents results of a multinomial logistic regression parallel to that presented in model 3 of Table 3, but includes a linear function of the dollar amount of the expected loss in EITC benefits upon marriage in addition to the indicator for whether the respondent expects to lose EITC benefits upon marriage.Footnote 14 Results suggest a curvilinear association between the size of the expected loss and marriage and cohabitation decisions. Those who expect to lose EITC benefits upon marriage are 3.5 percentage points less likely to marry and 3.5 percentage points more likely to cohabit. A $1000 increase in the amount of EITC benefits a respondent expects to lose upon marriage leads to an insignificant, 0.3 percentage point increase in the propensity to marry, and a significant 0.3 percentage point decrease in the propensity to cohabit. This suggests that the loss itself plays a larger role in marriage and cohabitation decisions than the actual dollar amount of the loss. This might be expected if there is some uncertainty among EITC-eligible households regarding the precise change in EITC benefits upon marriage. This may also arise if there is measurement error in the dollar amount of the expected change in EITC benefits upon marriage.

As an alternative to the linear specification of the expected loss in EITC benefits upon marriage, I also conducted an analysis using a quintile specification, where the expected change in EITC benefits upon marriage were modeled as five categories. Respondents in the bottom quintile of expected change in EITC benefits upon marriage were those who expected to gain benefits upon marriage, on average of $2000. Those in the second quintile were those who expected small gains in benefits, averaging $200. Those in the third, fourth, and fifth quintiles all expected to lose benefits upon marriage, averaging $440, $2350, and $4400, respectively. Using these quintiles, I then regressed the outcome of interest on indicators for the quintile of expected change in EITC benefits upon marriage, with the bottom quintile serving as the reference category. All demographic controls, state, and year fixed effects are also included in the model.

Figure 4 presents the coefficients on the quintile of expected change in EITC benefits on the propensity to marry or cohabit at some point throughout the SIPP survey. Ninety-five percent confidence intervals are indicated by the vertical bars. Results corroborate evidence from Table 5 that there is a slight curvilinear relationship between the size of the expected loss in EITC benefits and the propensity to marry or cohabit. Respondents who expect to lose moderate amounts of benefits (those in the third and fourth quintiles) are about 1.5–2.5 percentage points less likely to marry compared to those in the bottom quintile (comprised of those who expect to gain benefits upon marriage). Those who expect to lose large amounts (over $4000 on average) are only about 1 percentage point less likely to marry compared to those in the bottom quintile. These results are not statistically significant from each other, though they provide some suggestive evidence of diminishing effect of the size of the loss on marriage rates. A similar pattern is observed for cohabitation. Those in the third and fourth quintile of expected loss in EITC benefits upon marriage are most likely to cohabit, on the order of 1–1.5 percentage points. Those in the top quintile of expected losses are about 0.6 percentage points more likely to cohabit, though this is not significant at conventional levels.

Finally, I also replicate the results from Table 3 using different thresholds for the expected loss in EITC benefits upon marriage. There may be some concern that due to the random spouse match, there is some measurement error associated with the indicator for whether a respondent can expect to gain or lose EITC benefits upon marriage, particularly if the expected change in EITC benefits upon marriage is relatively small. I address this concern by redefining an expected loss in EITC benefits upon marriage as a loss of at least $500 or at least $1000. Individuals who expect to lose EITC benefits less than these amounts are considered part of the reference category for this analysis. Defining a loss as one where at least $500 or $1000 is lost provides more confidence that results are driven by respondents who expect moderate losses in EITC benefits upon marriage and not by individuals experiencing very small changes in EITC benefits upon marriage, which may be contaminated by measurement error.

Results of this exercise are presented in Supplementary appendix Table A5. In panel A, I replicate the results from Table 3, while panel B and panel C illustrate the results of redefining a loss as one of at least $500 or at least $1000. While two-thirds of the sample expected to lose any EITC benefits upon marriage, 58 % expected to lose at least $500 and half expected to lose at least $1000. Marriage results are quite similar to those presented in Table 3: respondents who expect to lose at least $500 or at least $1000 are about 2–2.5 percentage points less likely to marry compared to those who expect to lose less than that amount.Footnote 15 Results for the propensity to cohabit are a bit more sensitive to the definition of a loss, but coefficients remain in the expected, positive direction.

6.3 Alternate specifications of expected spouse earnings

While results are not sensitive to the particular specification of the expected loss in EITC benefits upon marriage, it remains a possibility that potential spouse earnings, and therefore expected changes in EITC benefits upon marriage, are overestimated. Single mothers may be less desirable marriage partners than single childless women, and therefore tend to match with lower-earning spouses than women without children. One concern with the analysis thus far is that the spouse match generates matches that overestimate the earnings a single mother can expect from a partner. I next illustrate that results are robust to specifying the spouse match to matching single mothers to very low-earning spouses.

I do this by simulating what the EITC marriage penalty would be if all women in the sample were matched to men of very low earnings, alternately simulating a spouse earning $1000, $5000, or $10,000. This exercise serves two purposes. First, it reduces the concern that the estimated losses in EITC benefits upon marriage are unrealistically high. Second, it eliminates the variation in the expectation to lose EITC benefits that is driven by the random spouse match altogether. By constraining all women in the sample to marry men of the same earnings levels, the variation in whether a respondent can expect to gain or lose EITC benefits upon marriage is driven by her own earnings, the number of children residing in the household, and the federal and state variation in EITC generosity. I further control for baseline earnings, number of child, state, and year fixed effects to constrain the variation to be driven solely by within-state changes in EITC policies over time.

Results of this exercise, presented in Table 6, suggest that the marriage results are concentrated among women who would experience losses in EITC benefits even if they were matched to spouses who earned $1000. These are women with earnings that would place them on the very end of the plateau region or the phase-out region of the EITC schedule, depending on the tax year. In 2001, a single mother earning $13,000 would experience a loss in EITC benefits if household earnings increased by $1000 through marriage, but a single mother in 2009 with the same level of earnings would experience no change in EITC benefits upon marrying a spouse earning $1000.Footnote 16 Results for marriage are much weaker when simulating a spouse earning $5000 or $10,000. For these levels of earnings, there is less federal variation over time in the likelihood of experiencing a loss in EITC benefits. A single mother in 2001 earning $13,000 would face a loss in benefits upon marrying a spouse earning $5000. Similarly, a single mother in 2004 with the same level of earnings would also face a loss in EITC benefits upon marrying a spouse earning $5000 since the marriage threshold was only extended by $1000 in 2004. Cohabitation effects, on the other hand are primarily driven by women who expect to lose benefits when their spouses earn larger amounts—$5000 or $10,000. Cohabiting women tend to have lower initial earnings at the start of the survey compared to women who remain single, so this effect may partially be driven by the fact that women who eventually cohabit have lower earnings (and are less likely to lose EITC benefits upon marriage) than women who remain single. This exercise illustrates that marriage and cohabitation results are not sensitive to the particular specification of the spouse match.

7 Conclusion

The EITC is a widely popular program due to its success in lifting millions of households out of poverty. Prior work finds that it increases the labor supply of single mothers (Ellwood 2000, Meyer and Rosenbaum 2001) and evidence suggests positive outcomes for child test scores (Dahl and Lochner 2012) and maternal health (Evans and Garthwaite 2010). The extent to which the EITC also influences marriage and cohabitation decisions could influence how we interpret these findings. Previous evidence on the effect of the EITC on marriage and divorce suggests small, negative impacts on marriage and virtually no impact on divorce (Dickert-Conlin and Houser 2002, Eissa and Hoynes 2000, Ellwood 2000, Fisher 2013, Herbst 2011).

This analysis builds on prior work by incorporating information on potential losses and gains in EITC benefits associated with marriage for a sample of low-income, single mothers. Results indicate that most single mothers can expect to lose some of their EITC benefits upon marriage. Among those who expect to lose benefits, the average single mother can expect to lose $2600 in EITC benefits upon marriage, a 75 % decline in pre-marriage EITC benefits. This result in itself reflects a system that lacks horizontal equity—two individuals who are unmarried pay lower taxes than if they had the same level of earnings but were married and filing their taxes jointly. For the purposes of horizontal equity, efforts to reduce the marriage penalty associated with the EITC would reduce marriage distortions.

In analyzing how these losses affect subsequent marriage and cohabitation decisions, results from the multinomial logistic regression analysis suggest significant declines in the propensity to marry and increases in the propensity to cohabit among single mothers who expect to lose EITC benefits upon marriage. Single mothers who expect to lose EITC benefits upon marriage are 2.7 percentage points less likely to marry and 2.5 percentage points more likely to cohabit compared to women who expect no change or to gain benefits upon marriage. These effects are similar to recent estimates by Fisher (2013) that find a 1.7 percentage point decline in the stock of marriages associated with a $1000 increase in the marriage penalty in the tax code. These results were calculated using different identification strategies among different samples of individuals, providing further confidence in the connection between the tax code and marriage and cohabitation.

Results from this analysis have implications for the interpretation of previous work examining the effect of the EITC on other household processes. For instance, much of the early research on the labor supply impacts of the EITC focuses on single mothers (e.g., Ellwood 2000; Meyer and Rosenbaum 2001). The extent to which the EITC affects the composition of single mothers due to its marriage disincentives affects the interpretation of these results. More work is needed in this area to determine the extent to which previous findings in the literature are driven by changes in family structure.

Results from this analysis imply EITC recipients do respond to financial incentives to marry or cohabit with their partners and the benefit structure of the EITC may influence these decisions. Results are robust to the size of the expected loss in EITC benefits, the window of observation, and to some alternate specifications of the spouse match. Results are also concentrated among demographic groups one would expect: the least educated, racial minorities, and those who have never been married before. As nearly two-thirds of this sample of single mothers would lose EITC benefits upon marriage, eliminating the marriage disincentives in the EITC structure could have an impact on the marriage and cohabitation decisions of millions of low-income families.

Notes

Recent studies have found that marginal tax rates for a second earner approach nearly 70 %, once accounting for the phase out of the EITC and other means-tested programs such as food stamps (Kearney and Turner 2013).

All dollars are scaled to 2014 dollars using the consumer price index.

Many of these studies focus on cohabiting couples where both individuals are the biological parents of the children in the household. In my sample, approximately half of the women who cohabit do so with the biological father, while only 25 % of women who marry do so with the biological father of her children.

I focus on single mothers, as they are the primary recipients of the EITC, but results are quite similar including childless single women in the analysis as well (see Supplementary appendix Table A2).

I exclude single mothers with a college degree from the analysis since there were very few that were eligible for the EITC, and those that were eligible are likely quite different from lower-educated single mothers. Results are robust to including college-educated single mothers and are available upon request.

Approximately half of the single mothers who cohabit during the survey window do so with a man who is biologically related to at least one child in the household. Approximately 25 % of the single mothers who married married the biological father of at least one of the children in the household. The biological father was determined by whether any children of the respondent reported having a biological father in the household.

A qualifying child is a biological child, adopted child, sibling, or descendent of any of these (such as grandchild or niece/nephew) who resides in the home for at least 6 months, or a foster child who lives in the house for the entire year (Internal Revenue Service 2013).

In some analyses, I also model the dollar amount of expected gain or loss as a linear function or parameterized into quintiles of expected change in EITC benefits upon marriage.

Sample size limitations prevent conducting separate spouse matches within each state.

As an additional robustness check, I also test the sensitivity of results to matching all respondents to spouses earning either $1000; $5000; or $10,000. This eliminates the variation in the expectation to lose benefits generated by the spouse match and instead relies on variation generated by federal and state policy changes to the EITC, as well as respondent earnings and number of children.

Results were quite similar using a logistic regression to predict the likelihood of marrying compared to remaining unmarried. Results available upon request.

A few individuals experience a transition to both cohabitation and marriage over the time period, so I code these individuals as married by the end of the survey. Approximately 4 % of the sample experiences both a cohabitation and a marriage within the 36–60 month surveys.

I also restricted the window to the first 12 months of the survey. Results are also presented in Supplementary appendix Table A4 and indicate no significant marriage patterns in the first year of the SIPP panel for women who expect to lose benefits upon marriage. Expectations to lose EITC benefits upon marriage may not be immediately realized, households may take a few years to respond to policy changes in the tax code.

Those who expect no change or to gain benefits upon marriage have a zero for the dollar amount of the expected loss in EITC benefits.

A parallel analysis modeling whether a respondent expects to gain benefits upon marriage is presented in Supplementary appendix Table A6 and provides consistent results with those discussed thus far. Women who expect to gain EITC benefits upon marriage are more likely to marry compared to those who expect to lose benefits upon marriage. Far fewer single mothers expect to gain EITC benefits upon marriage than the share who lose benefits, thus these results are somewhat less precise. Only 22 % of the sample expects to gain any benefits upon marriage, with just 12 % gaining more than $1000.

See Fig. 2 for an illustration of how the marriage penalty changes over time.

References

Alm, J., Dickert-Conlin, S., & Whittington, L. A. (1999). Policy watch: The marriage penalty. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 13(3), 193–204.

Alm, J., & Whittington, L. A. (2003). Shacking up or shelling out: Income taxes, marriage, and cohabitation. Review of Economics of the Household, 1(3), 169–186.

Baughman, R., & Dickert-Conlin, S. (2009). The earned income tax credit and fertility. Journal of Population Economics, 22, 537–563.

Becker, G. (1974). A theory of marriage: Part II. Journal of Political Economy, 82(2), 511–26.

Bertrand, M., Kamenica, E., & Pan, J. (2013). Gender identity and relative income within households (No. w19023). National Bureau of Economic Research.

Bitler, M. P., Gelbach, J. B., Hoynes, H. W., & Zavodny, M. (2004). The impact of welfare reform on marriage and divorce. Demography, 41(2), 213–236.

Bumpass, L., & Lu, H. (2000). Trends in cohabitation and implications for children’s family contexts in the United States. Population Studies, 54(1), 29–41.

Dahl, G. B., & Lochner, L. (2012). The impact of family income on child achievement. American Economic Review, 102(5), 1927–1956.

DeLeire, T., & Kalil, A. (2005). How do cohabiting couples with children spend their money?. Journal of Marriage and Family, 67(2), 286–295.

Dickert-Conlin, S., & Houser, S. (2002). EITC and marriage. National Tax Journal, 55, 25–40.

Edin, K. (2000). What do low-income single mothers say about marriage?. Social Problems, 47(1), 112–133.

Edin, K., & Kefalas, M. (2005). Promises I can keep: Why poor women put motherhood before marriage. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Eissa, N., & Hoynes, H. W. (2000). Tax and transfer policy, and family formation: Marriage and cohabitation. Mimeo

Ellwood, D. (2000). The impact of the earned income tax credit and social policy reforms on work, marriage, and living arrangements. National Tax Journal, 54(4), 1063–1105.

Evans, W. N., & Garthwaite, C. L. (2010). Giving mom a break: The impact of higher EITC payments on maternal health. National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper: 16296.

Fisher, H. (2013). The effect of marriage tax penalties and subsidies on marital status. Fiscal Studies, 34(4), 437–465.

Grogger, J., & Bronars, S. G. (2001). The effect of welfare payments on the marriage and fertility behavior of unwed mothers: Results from a twin experiment. Journal of Political Economy, 109(3), 529–545.

Herbst, C. M. (2011). The impact of the earned income tax credit on marriage and divorce: Evidence from flow data. Population Research Policy Review, 30(1), 101–128.

Internal Revenue Service. (2013). Qualifying child rules. http://www.irs.gov/Individuals/Qualifying-Child-Rules. Accessed 12 February 2013

Kearney, M. S., & Turner, L. J. (2013). Giving secondary earners a tax break: A proposal to help low- and middle-income families. The Hamilton Project Discussion Paper.

Kennedy, S., & Bumpass, L. (2011). Cohabitation and trends in the structure and stability of children’s family lives. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Population Association of America, Washington, DC.

Kenney, C. (2004). Cohabiting couple, filing jointly? Resource pooling and U.S. poverty policies. Family Relations, 53, 237–247.

Lichter, D. T., Qian, Z., & Mellott, L. M. (2006). Marriage or dissolution? Union transitions among poor cohabiting women. Demography, 43(2), 223–240.

Meyer, B., & Rosenbaum, D. T. (2001). Welfare, the earned income tax credit, and the labor supply of single mothers. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 116(3), 1063–1114.

Moffitt, R. A. (1998). The effect of welfare on marriage and fertility. In: Robert A. Moffitt (Ed.), Welfare, the family, and reproductive behavior: Research perspectives (p. 50). Washington DC: National Academies Press.

Oropesa, R. S., Landale, N. S., & Kenkre, T. (2003). Income allocation in marital and cohabiting unions: The case of mainland Puerto Ricans. Journal of Marriage and Family, 65(4), 910–926.

Smock, P. J., Manning, W. D., & Porter, M. (2005). Everything’s there except money: How money shapes decisions to marry among cohabitors. Journal of Marriage and Family, 67(3), 680–696.

Tach, Laura, & Halpern-Meekin, Sarah (2013). Tax code knowledge and behavioral responses among EITC recipients: Policy insights from qualitative data. Journal of Policy Analysis and Mangement, 33(2), 413–439.

Tax Policy Center. (2011). EITC, TANF, and food stamp participation rates, 1990–2004. Taxpolicycenter.org. http://www.taxpolicycenter.org/taxfacts/displayafact.cfm?Docid=273. Accessed 30 April 2011, http://www.taxpolicycenter.org/taxfacts/displayafact.cfm?Docid=36 Historical EITC parameters. Accessed 30 April 2011

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Michael Lovenheim, Kelly Musick, Sharon Sassler, and Laura Tach for helpful advice and comments. She would also like to acknowledge support from the Institute for Education Sciences on grant R305B110001. Any remaining errors are the author’s own.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Michelmore, K. The earned income tax credit and union formation: The impact of expected spouse earnings. Rev Econ Household 16, 377–406 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-016-9348-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-016-9348-7