Abstract

While the theoretical models of morphological processing in Roman alphabets indicate prelexical activation, a model established in Korean suggests postlexical activation. To extend the model of Korean morphological processing, this study examined within-scriptal (Hangul-Hangul prime-target pairs) and cross-scriptal (Hanja-Hangul prime-target pairs) priming effects on the recognition of Sino-Korean compound words in Hangul as a function of adult readers’ Hanja proficiency using priming lexical decision tasks. Experiment 1 (n = 54) examined the constituent morphemic effects of Hangul and Hanja primes, while Experiment 2 (n = 67) investigated morphemic decomposition in Hangul and Hanja primes. Participants with skilled Hanja proficiency showed robust constituent morphemic effects with both Hangul and Hanja primes in isolation, while less-skilled participants did not show the effects with Hangul and Hanja primes (Experiment 1). The skilled group showed efficient morphological decomposition in both within- and cross-script conditions. However, the less-skilled group did not show morphological effects in the cross-script condition but the same effect in the within-script condition (Experiment 2). The skilled group showed ortho-phonological inhibitory effects on Hangul recognition resulting from competitions among activated neighbors, but the less-skilled counterpart did not show the effect. Based on the findings of this study, two differing pathway models of morphological processing in Hangul are proposed for readers with different Hanja proficiency. Morphological processing in Sino-Korean compound words seems to be prelexical for skilled readers, whereas it is postlexical for less-skilled readers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The role of the structure and unit of compound words in visual word recognition has been of long interest in the psychology of reading. Morphological facilitation has been well documented in the Roman alphabet (Feldman et al., 2009; Marslen-Wilson et al., 2008; Rastle et al., 2004) and non-Roman script, especially in Chinese characters and Japanese mixed scripts (Chen et al., 2007; Hino et al., 2003; Joyce, 2002; Zhou et al., 1999). As orthography is a means to extract the morphological and semantic information of a given word, one way to understand the interaction between orthography and morphology is to winnow out how compound words are decomposed to access the meaning of a given word in visual word recognition using cross-scriptal presentations. An investigation of the effects of cross-scriptal morphological facilitation expands on the models of visual word recognition and the pathways of lexical access. This informs both universal processes and script constraints involved in word identification. To this end, we examined the effects of within- and cross-scriptal morphological facilitation in masked priming lexical decision tasks using Hangul (an alphabet) and Hanja (Chinese-derived morphosyllabary used in South Korea) primes for Hangul compound-word recognition as a function of readers’ Hanja proficiency. We also attempted to model the pathways of morphological access and processing for skilled and less-skilled Hanja groups.

Theoretical models of morphological processing

Morphology, access to morphemes, and morphemic processing are complex and multidimensional (Coch et al., 2020). A question as to whether polymorphemic compound words are processed as a whole or are decomposed into their constituent morphemes has been extensively addressed in the literature. General consensus on the morphological processing of polymorphemic words converges on the claim that words are decomposed into their constituent morphemes in Roman orthographies (Feldman et al., 1995; Marslen-Wilson et al., 2008; Rastle & Davis, 2008). However, the view on when and how polymorphemic words are segmented in the course of access to semantic information and the lexicon has been diverged. One view is that automatic morphological decomposition occurs at the early stage of lexical processing based on orthographic form (a.k.a. form-then-meaning account; Rastle & Davis, 2008; Taft, 2004). Rastle and Davis (2008) assert that the morphemic segmentation of morphologically complex words is based on the analysis of orthography as a general process rather than semantic information, which they refer to as morpho-orthographic decomposition. Marslen-Wilson et al. (2008) also assert that morphological decomposition occurs early in visual word recognition and is independent of semantic factors.

The other view is the model that morphological decomposition occurs simultaneously with orthographic and semantic access (a.k.a. form-and-meaning account; see Feldman et al., 2009; Schmidtke et al., 2017). Feldman et al. (2009) found that morphological facilitation was greater with transparent primes (coolant-COOL) than opaque primes (rampant-RAMP) in a priming lexical decision task, claiming that early morphological processes were morpho-semantic and were not simply morpho-orthographic. Schmidtke et al. (2017) reported that word frequency was the earliest lexical variable influencing lexical decision in the time-course of word recognition in English and Dutch-derived words (e.g., badness; bad +-ness), English pseudo-derived words (e.g., wander; wand+-er), and control words (e.g., ballad; ball+-ad). They also reported that semantic effects preceded or simultaneously emerged with morphological effects in the time-course of word recognition. These results supported the form-and-meaning view rather than the form-then-meaning account of complex word recognition. Although these two views have differing accounts, they share one point; that is, morphological access is prelexical.

A possibility of the language-specific variations of morphological processing has also been discussed. Of two morphological architectures, including a supralexical hypothesis (i.e., form-independent hierarchical processing wherein the morphemic unit is situated above the whole word unit) and a sublexical hypothesis (i.e., form-based hierarchical processing wherein the morphemic unit is situated below the whole word unit), Giraudo and Grainger (2000) reported supporting results for the supralexical representation of French derivational morphology within a hierarchically organized processing framework in masked morphological priming. They suggested a likelihood of language-specific processing depending on a given language’s average word length, the saliency of cueing word boundaries, and the transparency of morphological structures. These factors are likely to affect whether morphemes are processed in a whole-word top-down hierarchical fashion or a bottom-up form-meaning hierarchical way. In another study, Giraudo and Grainger (2001) supported a supralexical representation of morphology with morphemic codes situating above the lexicon rather than a sublexical representation in French.

As a theoretical extension, a model established in Korean demonstrates a language-specific morphological processing (see below for the specificity of the Korean language and script). Specifically, Yi (2009) offered an essential primer on the model of morphological processing in Sino-Korean word recognition, which manifested language constraints on morphological processing. A series of early studies of the morphological processing of Sino-Korean words have found the marginal effects of morphological facilitation, compared to other conditions employed in studies (Bae & Yi, 2010; Yi, Jung, & Bae, 2007; Yi & Yi, 1999). Response times of morpheme repetition in the first syllable of Sino-Korean words (e.g., 반대–반칙 prime-target pair; meaning opposition–violation with the first syllable /ban/ meaning against in both the prime and the target) were not significantly different from those of the unrelated condition (e.g., 학교–반칙 prime-target pair; school–violation). This nonsignificant morphological effect did not negate morphological processing involved in word recognition, however. Notably, the morphemic repetition condition (e.g., 반대–반칙) was more advantageous than orthographic repetition in the first syllable of the disyllabic words in recognizing the target (e.g., 반지–반칙; ring–violation; Yi & Yi, 1999). The absence of robust morphological facilitation effects could be explained with the inhibitory priming effects of neighbors due to lexical competitions among neighbors activated in the process (Nakayama et al., 2014). This explanation can be feasible especially when high frequency words are used as primes. High-frequency primes are likely to evoke competitions among activated neighbors upon the visual presentation of text, which leads to an inhibitory effect, and, at the same time, it is possible to facilitate morphological processing due to the shared morphological unit in the prime and the target. By considering the relations among letters, syllables, words, and morphemes, Yi (2009) proposed postlexical morphological representations in the mental lexicon especially for the processing of Sino-Korean words because competitive morphological cues can be resolved after lexical access in Korean. The postlexical route is particularly taken for the resolution of ambiguity between syllables and morphemes. It is possible that the idiosyncrasy of the Korean language and writing system places constraints on the morphological processing of Sino-Korean compound words. It is also possible that Hanja proficiency plays a crucial role in whether readers take a direct route for a syllable-morpheme correspondence or they rely on a postlexical route for morphological processing after analyzing lexical information. Although there has been a lack of research on prelexical versus postlexical processing in the word recognition of Korean words, a recent study suggests that individual differences be one of key factors affecting morphological decomposition of Sino-Korean words (Yi, 2009). Overall, what has been found in Korean is different from the prelexical morphological activation mostly found in Roman alphabetic scripts and non-alphabetic scripts (Feldman et al., 2009; Rastle & Davis, 2008; Schmidtke et al., 2017; Zhou et al., 1999). This warrants research that examines the role of constituent morphemes and the way in which morphological decomposition occurs in word recognition (which were examined in the current study).

Morphological processing in visual word recognition

Morphological processing seems to be different depending on the types of morphemes. While suffixes are coded position-specifically, stem morphemes are position-independent in processing polymorphemic words (Crepaldi et al., 2010, 2013). Coch et al. (2020) found that bound stem morphemes were recognized faster than free morphemes, suggesting that all morphemes were processed differently. Kim et al. (2015) also found that prefixed and suffixed words were processed differently in Korean. While suffixed primes exerted significant priming effects on the recognition of stems, irrespective of the lexicality or interpretability of primes, prefixed primes showed significant priming effects only with real-word primes. They suggested that there might be two different mechanisms involved in processing derivational-morphemic words in Korean, including one with prelexical morphological decomposition for suffixed words and the other with supralexical morphological decomposition for prefixed words.

The effects of morphological facilitation were also examined in logographic Chinese beyond alphabetic scripts. Zhou et al. (1999) investigated Chinese compound words using masked priming and visual-visual priming lexical decision tasks. Shared common morphemes showed facilitatory effects with a modulation by the spatial overlap of orthographic forms in the prime-target pair. Compound words with homographic-homophonic characters also showed significant priming effects. However, these significant facilitatory effects disappeared when the SOA was long and when the competing morphemes appeared at the initial position of the prime and the target. An inhibitory effect was found in words with homographic but non-homophonic characters. Words with orthographically different homophonic morphemes did not show significant effects. The results suggest that lexical representation incorporates morphological structures into visual recognition. It seems that the way in which morphological, orthographic, and phonological information interacts among them constrains the semantic activation of constituent morphemes in compound words.

Morphological facilitation was also found in Japanese Kanji recognition. Hirose (1992) found facilitatory effects in prime-target pairs that shared Kanji characters in digraph Kanji words using a long SOA (3000 ms). In a follow-up study using five different word formation types (i.e., modifier+modified, verb+compliment, complement+verb, associative pairs, and synonymous pairs), Joyce (2002) found similar effects when the long 3000 ms and shorter SOA of 250 ms were employed. Nakayama et al. (2014) also found a similar result. They used Kanji compound words (e.g., 支障, trouble) as targets with initial-character primes (e.g., 支) and control primes (e.g., 引) to find faster RTs and lower error rates with initial-character primes than controls.

The findings reviewed above indicate that morphological facilitation effects are observed not only in alphabetic scripts but also in nonalphabetic scripts. This suggests that meaning processing might go through universal processing, independent of script characteristics. Since previous studies used the same script in both primes and targets, however, it is still unknown whether priming effects would be different across different scripts used in the prime and the target. Using different scripts in the prime-target pair would offer a better understanding of the role of script in morphological processing.

Effects of cross-scriptal priming

Research shows that unique characteristics that each writing system entails tend to shape networks and pathways to lexical access, which hints at different processes involved in alphabetic scripts and non-alphabetic scripts. Perea et al. (2017) used alternating-script priming within Japanese Kana (i.e., Hiragana and Katakana) to investigate whether the models of visual word recognition established in the Roman alphabet could extend to Japanese Kana. The basis on which they relied for their study was the finding that the magnitude of masked priming effects was similar across lowercase, uppercase, and alternating-case primes (e.g., beard–BEARD, BEARD–BEARD, and BeArD–BEARD prime-target pairs). Their results found in the Kana system were different from those found in the Roman alphabet. The alternating-script repetition of Hiragana and Katakata in primes and targets did not produce similar priming effects to those of same-script repetition prime-target pairs. This indicated that, even within the Kana system, Hirakana and Katakana scripts were likely to go through different routes due to different abstract character-level representations. The findings suggested different pathways engaged in lexical access depending on scriptal characteristics across scripts, which was consistent with Giraudo and Grainger’s (2000) notion.

Another study took advantage of the duality of the Kana system in Japanese. Okano et al. (2013) used repeated and unrelated prime-target pairs of Japanese words for an ERP investigation in within-script pairs (i.e., Hiragana-Hiragana pair and Katakana-Katakana pair, Exp. 1) and cross-script pairs (Hiragana-Katakana pair and Katakana-Hiragana pair, Exp. 2). Results showed that the prime types modulated the N250 (sublexical processing) and N400 (lexical–semantic processing) components. The effects of visual feature processing were observed only in the shared within-script priming. The results suggested that different writing systems might undergo similar neurocognitive processes with some variabilities involved in visual word recognition.

The Japanese writing system further offers an opportunity to investigate the effects of cross-scriptal priming on morphological processing due to being multi-scripts. Kana are phonetic syllabaries in which each character represents a mora, while Kanji are Chinese-derived logograms in which each character represents a morpheme. Kanji are used for content words and compound words (a.k.a., Jukugo, 熟語, idioms). Kana consist of Hiragana (used for function words and proper nouns) and Katakana (used for foreign or loan words). Although Perea et al. (2017) and Okano et al. (2013) used cross-script prime-target pairs of Kana, they did not use Kanji. Chen et al. (2007) investigated homophonic and semantic priming effects among native Japanese readers using cross-scripts of Kanji and Hiragana. They compared the priming effects of homophonic, semantically related, and unrelated prime-target pairs in short (85 ms) and long (150 ms) intervals in within-script (i.e., Kanji-Kanji pair, Experiment 1) and cross-script (i.e., Hiragana-Kanji pair, Experiment 2). When meaning-based Kanji were primed, semantically related primes facilitated Kanji target recognition at both intervals, while phonologically-related Hiragana primes did not show significance. In contrast, when sound-based Hiragana were primed for Kanji targets, homophonically-related Hiragana facilitated Kanji target recognition at both intervals, but semantic relatedness exerted a significant priming effect only at the longer interval. Taken together, these results indicated that phonology might not be mandatory to access meaning from print in Kanji processing, which suggests different pathways to the lexicon involved in word recognition according to the script being used.

Orthography-based input into lexical decision was also examined using a cross-scriptal priming paradigm. Hino et al. (2003) investigated cross-scriptal priming (Kanji-Katakana pairs and Katakana-Kanji pairs) and word frequency effects for Japanese words and nonwords in lexical decision and naming tasks. Stimuli were digraph Kanji nouns (familiar words) and their corresponding three- or four-syllable words in Katakana (transcribed unfamiliar words because the words are typically written in Kanji). Lexical decision data showed that repetition priming effects were salient only for word targets but not nonward targets. The effect was greater in the pair of familiar Kanji word primes and unfamiliar Katakana-transcription targets than vice versa for both high frequency and low frequency conditions. Hino et al. (2003) suggested that the significant Kanji priming effects were attributable to the pre-activation of orthographic codes and orthography-based input effects. Specifically, the Kanji primes activated its phonological representation, which in turn activated its orthographic codes that were consistent with the phonological representation of the unfamiliar Katakana target.

Although the cross-script effects found in Japanese mixed scripts are meaningful, one problem associated with the task materials is the different levels of familiarity and frequency of words written in Kanji and Kana. Some words are always written in Kanji in Japanese (e.g., Jukugo, idioms), while others always written in Kana. If Jukugo words are written in Kana, not only do the levels of familiarity and frequency decrease, but also the morphological boundary gets blurry. Hence, it is difficult to tease out Kanji priming effects from Kana priming effects. This issue is not found in the Korean writing system because the same Sino-Korean word can be written in either Hangul or Hanja. However, there has been a paucity in research into cross-scriptal morphological priming effects in Korean. A brief description of the Korean script and its use in Korea is in order.

Script use in South Korea

The official writing system in Korea is Hangul, which is an alphabet. The Korean government upholds the Hangul-only policy in public school textbooks, official documents, and online and paper-based newspapers and magazines. Since Hangul is a relatively recent cultural invention promulgated in the fifteenth century, compared to other writing systems, however, the Koreans have a cultural legacy of Chinese-derived Hanja (for more information, see Pae, 2020). Hanja are technically different from Hanzi used in China because, although the origin is of Chinese characters, Hanja are an adapted and modified version of traditional characters to accord with the Korean language and pronunciation. About 70% of the Korean lexicon can be written in either Hanja and Hangul (Lee, 1980) due to their origin tracing back to Chinese characters. The majority of Sino-Korean words are disyllabic compound words. Given the large portion of Sino-Korean words in the inventory of Korean vocabulary, there has been a heated debate for decades over whether the Hangul-only policy should sustain or a co-use of Hangul and Hanja should be adopted. The debate still continues.

Since Hanja have been used in a supplemental way by a segment of the public, the prevalence of their use varies significantly across individuals and contexts. In virtue of Hangul being a script that is easy to master, children learn to read in Hangul from an early age, mostly before or in kindergarten. Hanja are taught in secondary schools as an elective. Since Hanja are not included in the college entrance exam, most students, except those who wish to major in Hanja in college, are not motivated to learn Hanja. A lack of Hanja knowledge does not cause inconvenience for everyday business. As a result, a considerable disparity in Hanja skills exists in the Korean public. Public agencies administer Hanja certification exams, under the Korean government’s endorsement, conferring Level 8 (lowest) to Level 1 (highest) certificates. Level 1 requires a mastery of more than 3,500 characters, which is a skill level necessary for Hanja specialists or teachers. The certification exam is a criterion-referenced test rather than a norm-referenced test.

With respect to research, even though Japanese mixed scripts offer a great opportunity to compare scriptal effects on word recognition, each type of the Japanese multi-scripts, such as Kanji and Kana (Hiragana and Katakana), is used for different purposes (e.g., Kanji are used for content words, while Kana are used for function words or loan words). In Korean, only Sino-Korean words can be written in either Hangul or Hanja. Native Korean words and loan words are written only in Hangul because they do not have Hanja equivalencies. The writing duality of Sino-Korean words makes Korean ideal to investigate cross-scriptal priming effects of morphology on compound word recognition.

Since Hangul and Hanja are written in blocks, the length of a written disyllabic Sino-Korean word in Hangul is corresponding to that written in Hanja. This helps equalize the length of the prime and the target in the design of a priming task. This utility is not found in Japanese, as shown in the two-character Sino-Japanese word “展示” becoming the three-character Kana word “てんじ”. This kind of inequality in the length of Kanji and Kana is considerably found in the Japanese writing systems. In addition, while the body of the literature has found the salient effects of morphological decomposition in Roman alphabets, Chinese, and Japanese, it is still unclear, due to a lack of empirical data, whether this holds true for the Korean language.

Current study

The aim of this study was to model the organization of morphological information and pathways of access to polymorphemic Sino-Korean words. This study pitted Hangul primes and Hanja primes against each other in a masked morphological priming test with within- and cross-scriptal presentations.

It is possible that the pathways of recognizing Hangul and Hanja are similar to each other, and, at the same time, are different from each other due to universal processes involved in reading as well as the different levels of representations engaged in word identification depending on the script being read. This also hints at differences in how and when a morphological decomposition occurs in visual word recognition across different scripts. Two research questions were formulated for this study.

Research Question 1: How do independent constituent morphemes operate in the recognition of Sino-Korean compound words as a function of Hanja proficiency (i.e., skilled vs. less-skilled)?

This question was posed to examine the role of constituent morphemes in compound word recognition in Korean. It also addressed whether morphological facilitation or inhibition occurred at the sublexical level or at the scriptal level. If the onset constituent morpheme of the target that was presented in isolation as a prime in either Hangul or Hanja facilitated the recognition of the Hangul target, the results could be interpreted as positive constituent priming effects at the sublexical level. If constituent morphemes that were presented in Hangul and Hanja primes exerted the different patterns of faciliatory effects, the results could be interpreted as positive constituent priming effects at the scriptal level. This was compatible with the view that repetition in cross-scripts was likely to activate the target’s lexical representation irrespective to the script being presented due to the shared morphology (and phonology) of the syllable or word (Hino et. al., 2003).

Research Question 2: How does morphological decomposition occur in Sino-Korean compound word recognition as a function of Hanja proficiency (skilled vs. less-skilled)?

This question was posed to investigate how morphological information was to be activated through sublexical decomposition when the prime showed a partial repetition of morphology and ortho-phonology beyond scriptal differences between the prime and the target. If morphemes in compound words were efficiently segmented into constituent morphemes early in the process, facilitatory effects would be observed in both morphologically- and ortho-phonologically-related priming conditions. If the constituent morpheme in the prime was not sufficient enough in the lexical context to extract practical morphological information for the target, facilitatory priming effects would not be observed.

Regarding the role of Hanja proficiency in compound word recognition, learning Hanja is likely to promote an understanding of relations between constituent syllables and a given word by virtue of the morphosyllabic charaterisitics. Therefore, it is reasonable to assume that the representation of Sino-Korean words in the mental lexicon would be different across individuals who have differing levels of Hanja skills. We expected that a Hanja skilled group would perform better on Hanja morphological processing than a less-skilled counterpart. However, there has been no behavioral data that support or rebut the prediction. This study was designed to fill this gap in the literature.

Experiment 1

The first research question was addressed in Experiment 1. A constituent morpheme (the onset syllable of the target) was independently presented in either Hangul or Hanja as the prime. The target was always presented in Hangul. The Hangul-Hangul prime-target pair showed both within-script morphological and ortho-phonological repetitions (i.e., identical stimuli in terms of morphology, orthography, and phonology), while the Hanja-Hangul prime-target pair showed cross-script morphological and phonological repetition (i.e., identical stimuli in terms of morphology and phonology but different in orthography). We hypothesized that, although Hangul and Hanja primes would not yield significant differences between them due to shared phonological and semantic cues provided in the prime, the priming effects of constituent morphemes would be significantly greater for participants who had optimal Hanja proficiency than less-skilled counterparts.

Method

Participants

Fifty-four undergraduate students from a university in South Korea participated in the experiment. The participants were split into two groups based on their Hanja proficiency level. Since Hanja are not mandatory for secondary schoolers in Korea, as briefly indicated earlier, Hanja skills vastly varied across individuals who have obtained the Hanja certificate and who have not. The skilled group consisted of 27 students (mean age = 22.5, SD = 1.2; male: 12), who were Hanja Education or Chinese Language and Literature majors and obtained Level 2 or higher in the certification for Hanja proficiency. Level 2 in the Hanja certification requires a mastery of at least 2,500 Chinese characters. The less-skilled group comprised 27 students (mean age = 22.1, SD = 1.6; male: 14), who were Humanities majors but have not studied Hanja on their own after middle school, did not have a Hanja proficiency certificate, and expressed no plan to study Hanja in the future. Since the less-skilled group did not have a certified performance level of Hanja skills, we relied on a self-report on a 5-point Likert scale. The two groups’ scale scores of Korean vocabulary and reading comprehension were not different from each other. However, their scale scores of Hanja proficiency were different: t(52) = 32.29, p < 0.0001; mean scale scores: skilled group = 4.35; less-skilled group = 1.07). All participants’ vision or corrected vision was in the normal range.

Stimuli

Sino-Korean disyllabic compound words were selected from the Modern Korean Usage Frequency Survey 2 published by the National Institute of the Korean Language (Kim, 2005). The stimuli were composed of prime-target pairs in two conditions (morphologically related and unrelated conditions). The target stimuli included 80 Sino-Korean words (mean frequency = 10.14, SD = 9.76, per million words). Another set of 80 nonwords was also created by replacing one of the syllables of the real word. Four experimental lists were constructed, two of which had Hangul primes and the other two of which had Hanja primes. Each list included 80 items (40 words and 40 nonwords) in a different order of conditions to control for presentation order effects and to counterbalance items to avoid practice and fatigue effects. For the related condition, the initial syllables of 80 targets were used for 80 primes, which were written in either Hangul (40 items) or Hanja (40 items). For the unrelated condition, another set of 80 words was selected, but the primes did not share any lexical quality with the targets (see Table 1 for examples). The target was always presented in Hangul, while the prime was presented in either Hangul or Hanja depending on the condition at hand. We used the first syllable of the disyllabic word because it tended to serve as an anchor to the meaning of the entire compound word (e.g., Kwon, 2012; see Appendix 1 for the entire set of word stimuli).

Procedure

The experiment was presented using DMDX (Forster & Forster, 2003) on a IBM PC/AT compatible. Participants’ responses were collected using a button box connected with a PCI-DIO24 Interface Card (Measurement Computing Corporation). The stimuli were presented on a 20.92-in × 11.76-in screen, with a refresh rate of 100 Hz. The experiment was carried out in a laboratory that had soundproof facilities. The stimulus appeared in white at the center of the screen in a black background. The prime was presented in the 18-point Batang font, while the target was presented in the 20-point Gothic font. The participant sat comfortably in the distance of 60 cm from the computer screen.

The experimenter read out loud the direction of the task and answered the participant’s questions, if any, before beginning the experiment. The experiment began with a fixation point comprising six hash marks (######) for 500 ms. Each prime was presented with a 300 ms interval. The prime was presented for 40 ms in Hangul or Hanja depending on the condition. The target was presented after 10 ms after the prime disappeared. The participant pressed a button on the right if the target was a real word and the one on the left if the target was a nonword upon his/her lexical decision. Once one of the buttons was pressed, the target disappeared and the next prime appeared after 2000 ms. Prior to the main experiment, the participant practiced 30 items for practice and was given necessary feedback. The practice items were not included in the main experiment.

Results and discussion

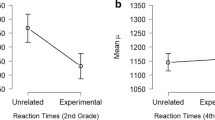

Data-trimming took place by eliminating one participant’s data that showed an error rate of more than 15% as well as response time (RT) falling below 300 ms and above 1300 ms, which accounted for 5% of the entire data. Table 2 shows the means and standard deviations of the RTs by condition and the participant’s proficiency level.

To address the first research question, linear mixed-effects modeling and generalised linear mixed-effects modeling were performed using R version 4.1.1 (R Core Team, 2021) and the R packages lme4 (Bates, Mächler, Bolker, & Walker, 2015). Subjects and targets were entered as random effect variables. The relatedness (morphologically related or unrelated), prime type (Hangul or Hanja), and Hanja proficiency (skilled or less-skilled) were used as explanatory variables, in which sum-to-zero contrasts were coded. The dependent variables were RTs and error rates. The RTs were normalized using an inverse transformation (− 1000/RT). The p value for the fixed effects was computed using the Satterthwaite approximation built in the lmerTest package (Kuznotsova et al., 2017). When interaction effects were significant, post-hoc comparisons were made using the estimated marginal means package (Lenth et al., 2018).

For RT analyses, a null model, a two-way interaction model (relatedness and prime type), and a three-way interaction model (condition, prime type, and Hanja proficiency) were compared. While a similarity was found in the null model and the two-way interaction model, the three-way interaction model showed the best fit, as indicated by AIC and deviances values. After taking trial, prior-item RT and error rates into account, log transformed onset-syllable frequency was not significant. However, the log-transformed word frequency was significant (b = − 0.037, SE = 0.015, t = − 2.561, p = 0.012). The main effect of the condition (related morphemes vs. unrelated morphemes) was significant (b = − 0.032, SE = 0.005, t = − 6.143, p < 0.001) such that morphologically-related stimuli yielded faster RTs than unrelated stimuli, regardless of other parameters in the model. However, the prime type (Hangul or Hanja) was not significant, indicating that RTs were not significantly different depending on whether the prime was Hangul or Hanja. As expected, Hanja proficiency yielded a significant main effect. Interaction effects between the condition and proficiency as well as among the condition, prime type, and Hanja proficiency were significant (see Table 2). Pairwise-comparisons made using the estimated marginal means (Lenth et al., 2018) showed significance only for the Hanja skilled group for both Hangul and Hanja primes (t = − 3.428, p = 0.006; t = − 7.836, p < 0.001, respectively). This indicated that the Hanja skilled group was able to take advantage of morphologically related primes written in both Hangul and Hanja for the target compound word written in Hangul. In contrast, the less-skilled group did not benefit from morphologically related primes either in Hangul or Hanja (Table 3).

Another set of generalized linear mixed models was fit for error rates. None of the explanatory variables was significant. Interaction effects were not significant except for the three-way interaction among the condition, prime type, and Hanja proficiency (b = 1.941, SE = 0.952, z = 2.040, p = 0.041). The contrasts of estimated marginal means indicated that the source of the significance resided in the Hanja prime type by the proficiency group (b = − 1.891, SE = 0.670, z = − 2.823, p = 0.0048). Since the majority of the variables and interactions were not significant for the error rates, the results are not provided in Table 2. The results of the error rates can be found in Appendix C.

In summary, while the less-skilled group did not show priming effects with Hanja and Hangul primes, the skilled group showed significant constituent priming effects in both Hanja and Hangul. This supported the hypothesis that semantic information elicited from the print was likely to activate related candidates from the mental lexicon and, in return, facilitated the recognition of the target word in Hangul. It was interesting to find no significant priming effects in the Hangul within-script pair for the less-skilled group. Hangul primes might not yield a significant priming effect for the less-skilled group because Hangul could not activate semantic information from the mental lexicon. It is notable that the skilled group performed better than the less-skilled counterpart in both Hanja and Hangul primes. This suggests that Hanja knowledge can serve as a catalyst for the efficient processing of Sino-Korean compound words regardless of which script being read. It also suggests that readers with high Hanja proficiency process and access to Sino-Korean polysyllabic words sublexically, whereas readers with less-skilled Hanja might process them lexically.

Experiment 2

Based on the findings of Experiment 1 that showed significant constituent priming effects only for the Hanja skilled group when constituent primes were presented in isolation, we attempted to further examine the mode of morphological decomposition in Sino-Korean compound words. Unlike Experiment 1, we presented within- and cross-script constituent primes embedded in compound words (i.e., only the onset syllable of the prime shared with the onset syllable of the target) in order to examine how morphological decomposition took place in the face of the whole lexical information of a compound word. In other words, the second research question was addressed in Experiment 2. We hypothesized that participants with high Hanja proficiency would make use of morphologically-related primes more than ortho-phonologically-related primes, while the counterpart with lower Hanja proficiency would not be efficient in taking advantage of morphemic information provided in primes.

Method

Participants

Sixty-seven undergraduate students took part in a priming lexical decision task from the same institution as in Experiment 1. The participants were broken down into two proficiency groups of Hanja. The skilled group comprised 33 students (mean age = 22.7, SD = 1.5; male: 7), whose majors were Hanja Education or Chinese Language and Literature and who obtained Level 2 or higher in the certification of Hanja proficiency. The less-skilled group comprised 34 students (mean age = 22.9, SD = 1.4; male: 9), whose majors were non-Hanja Education nor Chinese Language and Literature and who have not studied Hanja on their own after middle school, did not have a Hanja proficiency certificate, and expressed no intention to study Hanja in the future. Their self-rating scales for Korean vocabulary and reading comprehension were not different from each other. However, their ratings for Hanja skills were significantly different from each other (t (65) = 33.74, p < 0.0001; mean scale scores: skilled group = 4.5; less-skilled group = 1.08 on a 5-point scale). These participants did not participated in Experiment 1. All participants’ vision or corrected vision was in the normal range.

Stimuli

The stimuli were composed of 270 prime-target pairs of disyllabic Sino-Korean words. They were selected from the Modern Korean Usage Frequency Survey 2 (Kim, 2005). The mean frequency of the target items was 9.84 (SD = 10.76) occurrences per million. The primes comprised three types: (1) 90 morphologically related primes which had identical onset syllables with target words (mean frequency = 8.83; SD = 9.01), (2) 90 ortho-phonological primes whose first syllables had the same orthography and the same sounds as target words in Hangul but had different meanings from target words and written differently in Hanja (mean frequency = 8.67; SD = 8.81), and (3) 90 control items that had different onset and second syllables with different meanings and different orthography than target words (mean frequency = 7.14; SD = 8.16). Note that the prime was ortho-phonologically-related in the within-script Hangul-Hangul prime-target pair, while the prime was phonologically-related in the cross-script Hanja-Hangul pair. This resulted from the fact that when a Sino-Korean word is written in Hanja, the word is orthographically different from the corresponding word written in Hangul (i.e., form difference) but shares the same phonology as the given word.

We controlled for neighborhood-frequency effects and unnecessary semantic associations involved in the processes. First, we ensured that the frequency of prime items was lower than that of target items so that primes could not inhibit the processing of targets (see Nakayama et al., 2014). This was done in consideration that if the frequency of the prime was higher than that of the target, it would be possible to have salient neighborhood frequency effects resulting in inhibitory priming effects. Second, in order to pick out pairs of stimuli from the stimulus bank that had no or little semantic association between the prime and the target, 70 undergraduates who did not participate in the experiment rated semantic relatedness on a 7-point scale (1 = no relevance; 7 = high relevance). Pairs which were rated 3 or higher were excluded in the experiment. Each target word was assigned in a morphologically-related condition, ortho-phonologically-related (or phonologically-related in the cross-scriptal prime) condition, or control condition. This assignment yielded 270 pairs in total (90 items in each list × 3 conditions). The 270 stimulus pairs were counterbalanced by randomly assigning them in the three lists so that participants did not see the target twice or more. Within each list, there were two sub-lists, including three Hangul sub-lists that showed primes in Hangul and three Hanja sub-lists that showed primes in Hanja.

Table 4 displays the examples of stimuli used in each condition. To match the experimental conditions, we also constructed 270 nonword stimuli by changing one syllable of the target word into a nonword (see Appendix 2 for the entire set of word stimuli). In creating nonwords, we held the first syllable of the target word constant and changed the second syllable randomly. We went through several iterations to ensure that nonword stimuli were truly nonwords. Through the stimulus construction procedure, a total of six lists was prepared, each of which comprised 90 word stimulus pairs and 90 nonword stimulus pairs. Of the six lists, three lists included Hangul primes, while the other three lists included Hanja primes. The selection and order of the lists were randomly assigned and presented in the experiment.

Procedure

The procedure was the same as that of Experiment 1.

Results and Discussion

The same procedure of a data trimming scheme used in Experiment 1 was utilized. Two target items that showed error rates of 40% were eliminated. The dependent variables were RTs and error rates. The explanatory variables were onset-syllable frequency, target word frequency, script type (Hangul vs. Hanja), prime type (morphologically-related, orthographically/phonologically-related, or unrelated), and Hanja proficiency (skilled vs. less-skilled). Table 5 shows the mean RTs and error rates by Hanja proficiency group and prime type. Overall, both groups took advantage of morphological priming greater than orthographic priming, except for the Hanja priming for the less-skilled group.

For the RT data, linear mixed effects modeling was employed for the analyses of RTs and error rates. After taking trial, prior-item RTs and error rates into consideration, log transformed onset-syllable frequency was not significant. However, the frequency of log-transformed target words was significant. The other explanatory variables, including morphologically related, ortho-phonologically/phonologically related, prime type, and Hanja proficiency levels, were significant (see Table 4). Pair-wise comparisons for the skilled groups showed all significance (see Table 4). Notably, a significant inhibitory effect was found in the ortho-phonologically-related condition for the skilled group. However, pair-wise comparisons for the less-skilled group showed a different picture. They showed significant differences in priming effects between the morphologically related and ortho-phonologically-related conditions and between the morphologically related condition and the control condition for the Hangul primes. However, there was no significant difference between the ortho-phonologically-related condition and the control condition for the Hangul primes, meaning no inhibitory effect found for the less-skilled group. With the Hanja primes, the less-skilled group showed no significant differences in all contrasts.

A series of two-way interaction effects were also significant except for the interaction between orthographically/phonologically related and Hanja proficiency. The three-way interaction among morphologically related, prime type, and Hanja proficiency was significant (b = − 0.019, SE = 0.005, t = − 3.909, p < 0.001).

Regarding the error data, another set of models was fitted into linear mixed effects modeling. Word frequency and proficiency showed significant main effects (see the bottom half of Table 6). Unlike the RT data, the prime type did not show significance in the error rate data. Both morphologically-related and ortho-phonologically/phonologically-related conditions exerted significant priming effects (b = − 0.343, SE = 0.085, z = − 4.040, p < 0.000; b = 0.203, SE = 0.077, z = 2.65, p = 0.008, respectively). Given the significant results of Hanja proficiency as well as morphological and orthographic relatedness, pair-wise comparisons between the two groups were performed. Pair-wise contrasts showed that only skilled group demonstrated significant priming effects in the comparison between the morphologically-related condition and the ortho-phonologically/phonologically-related condition and between the morphologically-related condition and the control condition (b = − 0.761, SE = 0.223, z = − 341, p = 0.002; b = − 0.949, SE = 0.218, z = − 4.350, p < 0.001, respectively), but not between the ortho-phonologically/phonologically-related condition and the control condition. Of the two-way and three-way interactions, only the interaction between the morphologically-related condition and proficiency levels was significant (b = 0.238, SE = 0.085, z = 2.794, p = 0.005).

The results of Experiment 2 showed that morphological decomposition in Sino-Korean compound word recognition was dependent upon the reader’s Hanja proficiency. Specifically, while the skilled Hanja group took advantage of morphological primes provided both in Hangul and Hanja primes, the less-skilled group did not make use of morphological information provided in Hanja primes. The less-skilled group’s Hanja knowledge might not be substantial enough to exert a significant effect. However, the Hangul primes were facilitatory. This means that the less-skilled group was cognizant of partial constituent morphology when it was provided in the lexical form of Hangul. In contrast, partial ortho-phonological/phonological repetition in the within- and cross-script prime conditions did not exert significant effects for the less skilled group, meaning that ortho-phonological/phonological information was not as salient as morphological information for the recognition of Sino-Korean compound words. This finding is noteworthy. Specifically, the less-skilled group showed a facilitatory effect only in the morphological repetition condition in Hangul but no inhibitory effect in the ortho-phonological repetition in Hangul. This means no lexical competition involved among less-skilled participants, as opposed to the skilled counterpart that showed lexical competition evoked in the processes.

These results are consistent with the findings of Chen et al.’s (2007) and Perea et al. (2017) studies that different pathways are engaged in word recognition depending on the script being read. The finding also suggests that less skilled participants might be able to retrieve morphological information after the whole lexicon is accessed in Sino-Korean compound word recognition; that is morphological processing is post-lexical, which is consistent with Yi's (2009) model. This was described under the secion of theoretical models above.

The results of the skilled group are interesting. In the Hangul prime condition, a morphological facilitatory effect and an orthographic inhibitory effect were observed. This indicates that morphological facilitation is robust in Hangul word recognition. The inhibitory effect found in the orthographic repetition condition suggests competitions among words that share the same first syllables at the lexical level, which resulted in longer RTs in the target recognition. The magnitude of morphological facilitation with Hangul primes was smaller than that of the less-skilled group (28 ms vs. 46 ms), which might have resulted from inhibition among neighbors. The lack of orthographic repetition effects in the less-skilled group might have stemmed from the absence of competition among neighbors. What was notable for the skilled group was that the morphological facilitatory effect was larger in the Hanja (less usage in everyday activities) primes than the Hangul (prevalent usage in everyday activities) primes, and that no inhibition effect was found in the phonologically-related cross-scriptal condition. It seems that no competition takes place among word neighbors when the same word is written in different scripts (i.e., Hangul or Hanja) for the skilled group. As a result, the phonological effect gets smaller, but the morphological effect gets larger in the Hanja-Hangul cross-script priming condition for Hangul recognition among skilled readers.

General discussion

The main finding of this study was significant cross-scriptal priming effects on Sino-Korean compound word recognition for the Hanja skilled group. The magnitude of facilitatory priming effects was larger when the prime was presented in Hanja than in Hangul. This was robust both when the prime was a constituent morpheme that was presented in isolation (Experiment 1) and when the prime was a constituent morpheme that was embedded in a compound word (Experiment 2).

For the less-skilled group, the findings were different from those of the skilled counterpart. Less-skilled participants did not show priming effects when the constituent-morpheme prime was presented in isolation in neither within-script (Hangul-Hangul pair) nor cross-script (Hanja-Hangul pair) prime-target pairs (Experiment 1). However, they showed a different pattern of priming effects when Hangul primes were partially repetitive (i.e., the onset syllable of the prime shared with the onset syllable of the target). When the constituent-morpheme prime was provided in Hangul within a disyllabic compound word, facilitatory effects were observed (Experiment 2). The nonsignificant cross-scriptal priming effect found in both experiments among the less-skilled participants can be attributable to the lack of exposure to Hanja. As indicated earlier, Hanja are one of elective subjects in secondary schools in South Korea, and are not included in the entrance exam to college. Therefore, students in secondary education do not have high intrinsic motivation or demand to study Hanja. Another detractor is a preconception that Hanja does not have utility for their language use and college majors. However, the findings of this study do not support this practice and preconception. The skilled group was superior to the less-skilled counterpart not only in overall speed and accuracy of compound word recognition even in Hangul, but also in the decomposition into constituent morphemes of the compound word in both Hangul and Hanja.

The findings have several implications. First, notable is the fact that, even though Hanja were less familiar than Hangul for the participants, constituent primes provided in the Hanja stimuli yielded greater cross-scriptal priming effects than within-scriptal priming effects on compound word recognition in Hangul. What aspect of Hanja information did influence Hangul word recognition? Of Hanja characteristics that could possibly affect Hangul word recognition, phonological information and semantic information that could extract from Hanja stimuli are two probable factors that account for the contribution to Hangul compound word recognition. The results of Experiment 2 showed that, in the cross-script priming condition, phonologically-related priming effects were 19 ms, while the morphologically-related priming effect was 45 ms, showing that the magnitude of Hanja’s phonological information was significantly smaller than that of morphological information. It is possible that the extraction of semantic information from Hanja was much easier than the extraction of phonological information from Hanja, especially in the masked priming lexical decision.Footnote 1 This finding is in line with Japanese studies that found that phonological processing was not obligatory and played a marginal role in the recognition of Japanese Kanji (see Chen et al., 2007).

On the other hand, it is difficult to dismiss the meaning extraction from Hanja in masked priming and its further facilitation of target recognition, given that the results of Experiments 1 and 2 showed significant priming effects in Hanja-Hangul cross-scriptal pairs. One interpretation is that meaning extraction from Hanja activates related morphemic candidates from the mental lexicon and then further activates word candidates that contain relevant morphemes. For example, the prime 反 (/bɑn/ against) activates Hanja morpheme 反, and its activation extends to all words that contain the morpheme 反. In the course of this activation, if the target that includes the morpheme 反 (/bɑn/against), such as 반대 (/bɑndæ/opposition) and 반항 (/bɑnhɑŋ/resistance), is presented, the activated prime is likely to facilitate the target recognition. What is noteworthy is the finding that the activation of the Hanja constituent morpheme occurred regardless of whether a constituent prime was presented in isolation or embedded within a lexicon (i.e., partial repetition).

Second, relatedly, the results of the skilled group showed an effect of script type in word recognition. Skilled participants produced a larger effect in the Hanja prime condition than in the Hangul prime condition in Experiment 1. This means that morphemic processing in the Hanja prime is more reliable than in the Hangul prime. Although the prime type (Hangul vs. Hanja) did not show significant effects in both experiments, the interaction effects between the prime type and Hanja proficiency levels were significant in both experiments. Skilled participants took advantage of primes presented in both Hanja and Hangul regardless of whether the constituent prime was presented in isolation or embedded in the lexical context. Given that the within-scriptal condition (Hangul-Hangul pair) has the higher level of repetition in terms of orthographic, phonological, and morphological representations, the fact that the skilled group showed greater effects in the cross-scriptal condition than the within-scriptal condition suggests that Hanja’s advantage in Hangul recognition goes above and beyond the orthographic and phonological effects (note the inhibitory effects of ortho-phonology found in Experiment 2).

Third, the results of nonsignificant constituent morphemic priming effects in Experiment 1 for the Hanja less-skilled group in the Hangul-Hangul within-script condition were also deemed important. Although it was possible to reap morphemic information from the constituent morpheme presented independently in Hangul, the less skilled group was not able to take advantage of it (Experiment 1). This might have resulted from ambiguity in the correspondence between Hangul representation and morphemes. Specifically, Hangul syllable “사” /sɑ/ corresponds to more than 40 morphemes, which creates ambiguity in the Korean syllable-morpheme correspondence. When the level of ambiguity is high, morpheme processing could be hampered without a top-down semantic cue from the whole word. It is possible to have the extraction of orthographic information and phonological information from Hangul syllable at the prelexical stage, and, in turn, the extracted information invokes morphemic information to resolve neighbor competitions for word recognition. Based on the findings of Experiment 1, however, this mechanism does not seem to work for readers who have lower Hanja skills.

Fourth, we were able to identify true morphological effects in this study by controlling for orthographic/phonological repetition effects, as ruling out orthographic/phonological information was a necessary condition for examining the effect of morphemic processing. Since previous research presented both primes and targets in the same script, morphemic repetition was overlapping with orthographic repetition (Bae & Yi, 2010; Yi, Jung, & Bae, 2007; Yi & Yi, 1999). By virtue of utilizing different scripts in the prime and the target in this study, however, the overlapping effects could be eliminated. Since the Hanja-Hangul cross-scriptal presentation allowed us to examine true morphemic processing after ruling out orthographic information, the facilitatory effect of Hanja primes found in this study suggests an independence of morphemic processing in Sino-Korean word recognition.

Last, taken together, this study showed that individual differences manifested by proficiency are a central factor affecting Sino-Korean word recognition. Although we expected that the two proficiency groups would show the different effects of constituent primes in Hanja, the finding of different patterns of priming effects in the Hangul-Hangul within-script condition between the Hanja skilled group and the less-skilled group was surprising, which was a new finding. The skilled group showed a facilitatory effect in the morpheme repetition but an inhibitory effect in the orthographic/phonological repetition. Since Hangul is the only official script in South Korea, all individuals, irrespective of Hanja skills, are exposed to and use Hangul in everyday business. However, the two groups of university students, who had differing Hanja proficiency but passed the college entrance exam written in Hangul at the same level (which suggests similar level of Hangul reading skills; this was supported by the nonsignificant difference in vocabulary and reading comprehension in Korean between the two groups compared in this study, as indicated earlier in the Subject section), showed different patterns of constituent morpheme processing in Hangul. How could this be explained? It is possible that Hanja skilled group has a deeper understanding or knowledge of morphemes and thus it contributes to significant constituent-morpheme priming effects. Bae, Yi, and Masuda’s (2016) study showed that the morphological knowledge of college students was positively correlated with word recognition and academic performance, supporting the notion that Hanja morphological knowledge affects Sino-Korean compound-word recognition. This suggests that the sensitivity to morphological constituents within the word and efficient access to the mental lexicon can vary according to Hanja proficiency in the recognition of Sino-Korean compound words. This points toward the possibility that morphological access is pre-lexical for individuals with high Hanja proficiency, while it is post-lexical for individuals with lower Hanja proficiency.

Figure 1 depicts differing models for the two groups. The skilled group has stronger multidimentional interactions and pathways, whereas the less-skilled group has limited pathways. Since readers with high Hanja proficiency rely on Hanja to extract the morphological information of Sino-Korean compound words before accessing to the lexicon, they seem to less rely on Hangul for morphology, as shown in the weak interaction between Hangul and morphology. In contrast, for readers with low Hanja proficiency, since they cannot utilize Hanja input, they solely rely on Hangul but need to access the lexicon first in order to settle on the correct morpheme among activated morphemes of a given word. Note that morphemic access occurs before the lexicon for the skilled group, whereas it occurs after lexical access for the less-skilled group. The latter is consistent with Yi’s (2009) model, which explains a postlexical route that is taken for the resolution of ambiguity between syllables and morphemes in Sino-Korean words.

Adapted from Yi (2009)

The pathway models of Sino-Korean word recognition.

To summarize, the findings of this study extend the existing models and accounts for the morphological processing of Sino-Korean words. Prelexical routes involved in word recognition have been well documented in English (Rastle & Davis, 2008) and in Chinese (Marslen-Wilson et al., 2008). The utilization of prelexical or postlexical routes can also be subjected to individual differences, including proficiency levels. The ramifications of this study’s results point toward proficiency-dependent processing routes and pathways especially for the morphological decomposition of a given compound word. In other words, skilled readers can utilize both routes efficiently with a skewed prelexical route (i.e., relying on the postlexical route only for words that have a high degree of ambiguity between the syllable and the morpheme). However, less-skilled readers rely on the postlexical route because they utilize lexical information to extract the meaning of morphemes. Another contribution of this study gives rise to a corroboration of an additional route (i.e., form-after-meaning, which was suggested by Guiraudo & Grainger, 2000, 2001 with French data) involved in the recognition of compound word recognition beyond the early accounts for morphological processing of form-then-meaning (Rastle & Davis, 2008; Taft, 2004) and form-and-meaning (Feldman et al., 2009). The utilization of these different routes is dependent upon language systems, scripts, and individual differences including proficiency levels.

Future directions

We have addressed the effects of constituent morphemes and decomposition on the recognition of Sino-Korean compound words among native Korean readers in two experiments to propose two pathway models for Hanja skilled and less-skilled groups. Further studies should continue in Korean given the relative paucity in the body of knowledge, compared to other languages and scripts. Recommendations for future studies are as follows. First, since research shows that different types of morphemes, such as bound morphemes, free morphemes, derived morphemes, and inflected morphemes, have different processing advantages (Coch et al., 2020; Kim et al., 2015), future research into the role of different types of morphemes in Korean word recognition is in need. Relatedly, the same scheme of research can also extend to the recognition of native Korean words versus Sino-Korean words.

Second, this study did not consider the morphological structure within the compound words. As Joyce (2002) did in his study, using the five different word formation types (e.g., modifier + modified, verb + complement, complement + verb, associative pairs, and synonymous pairs) will provide a deeper understanding of morphological access and processing in Sino-Korean compound words.

Third, we used constituent morphemes in the intial position only. Since too many conditions or variables could cloud the focus of our study, we did not address syllable position effects in the current study. Follow-up research is warranted to address position effects in morphological processing in Korean.

Next, both facilitatory effects and inhibitory effects found among the skilled participants suggest individual differences in the structure and processing mode of the mental lexicon. It is possible that there are qualitative differences across readers in the orthographic, phonological, and semantic representations of the mental lexicon (especially according to different scripts being read). It would be useful to investigate how Hanja knowledge contributes to the optimal development of cognitive ability among Korean children. A longitudinal study will she light on the trajectory of the reader’s cognitive development from childhood to young adulthood.

Last, this study focused on isolated word recognition without context provided. Hanja primes significantly facilitated the rapid recognition of Hangul compound words, despite the saliently different visual representations between Hanja and Hangul. This line of research should continue in sentence processing and reading comprehension. Expanding on this line of research to the sentence level will help settle on the long debate over the Hangul-only policy versus a mixture of Hangul-Hanja usage in text, which has been controversial for decades in the circles of the Korean academia and government administrations. Research in this area also provides a better understanding of reading mechanisms underlying within-script and cross-script reading, and, in turn, contributes to the body of knowledge in the science of reading.

Notes

However, we cannot rule out the possibility that phonological information was extracted from masked primes in the process of lexical deicison. It is still an open question whether, even though phonological information was extracted, it was not sufficient enough to contribute to the recognition of the target. This speculation is raised because phonological priming effects have been rarely found in Korean, unlike salient phonological priming effects that have been found in English. Studies of Hangul show a zero effect or even an inhibition effect of phonological priming effect (see Park, 1999). Therefore, it is possible that phonological information could not contribute to the target recognition, even though it was activated to a certain degree in the course of Hangul lexical decision.

References

Bae, S., & Yi, K. (2010). Processing of orthography and phonology in Korean word recognition. The Korean Journal of Cognitive and Biological Psychology, 22(3), 369–385.

Bae, S., Yi, K., & Masuda, H. (2016). Morphological processing within the learning of new words : A study on individual differences. Korean Journal of Cognitive Science., 27(2), 303–323.

Bates, D., Mächler, M., Bolker, B., & Walker, S. (2015). Fitting linear mixed-effects Models using lme4. Journal of Statistical Software, 67(1), 1–48.

Chen, H.-C., Yamauchi, T., Tamaoka, K., & Vaid, J. (2007). Homophonic and semantic priming of Japanese Kanji words: A time course study. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 14(1), 64–69.

Coch, D., Hua, J., & Landers-Nelson, A. (2020). All morphemes are not the same: Accuracy and response times in a lexical decision task differentiate types of morphemes. Journal of Research in Reading, 43(3), 329–346.

Crepaldi, D., Rastle, K., Davis, C. J., & Lupker, S. J. (2013). Seeing stems everywhere: Position-independent identification of stem morphemes. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 39, 510–525.

Crepaldi, D., Rastle, K., Coltheart, M., & Nickels, L. (2010). ‘Fell’ primes ‘fall’, but does ‘bell’ prime ‘ball’? Masked priming with irregularly-inflected primes. Journal of Memory and Language, 63(1), 83–99.

Feldman, L. B., Frost, R., & Pnini, T. (1995). Decomposing words into their constituent morphemes: Evidence from English and Hebrew. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 21(4), 947.

Feldman, L. B., O’Connor, P. A., & del Prado Martín, F. M. (2009). Early morphological processing is morphosemantic and not simply morph-orthographic: A violation of form-then-meaning accounts of word recognition. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 16(4), 684–691.

Forster, K. I., & Forster, J. C. (2003). DMDX: A Windows display program with millisecond accuracy. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers, 35(1), 116–124.

Giraudo, H., & Grainger, J. (2000). Effects of prime word frequency and cumulative root frequency in masked morphological priming. Language and Cognitive Processes, 15, 421–444.

Giraudo, H., & Grainger, G. (2001). Priming complex words: Evidence for supralexical representation of morphology. Psychonomic Bulletin and Review, 8(1), 127–131.

Hino, Y., Lupker, S. J., Ogawa, T., & Sears, C. R. (2003). Masked repetition priming and word frequency effects across different types of Japanese scripts: An examination of the lexical activation account. Journal of Memory and Language, 48, 33–66.

Hirose, H. (1992). An investigation of the recognition process for jukugo by use of priming paradigms. Japanese Journal of Psychology, 63, 303–309.

Joyce, T. (2002). Constituent-morpheme priming: Implications from the morphology of two-kanji compound words. Japanese Psychological Research, 44(2), 79–90.

Kim, H. S. (2005). The modern Korean usage frequency survey 2. Seoul: National Institute of the Korean Language.

Kim, S. Y., Wang, M., & Taft, M. (2015). Morphological decomposition in the recognition of prefixed and suffixed words: Evidence from Korean. Scientific Studies of Reading, 19(3), 183–203.

Kwon, Y. (2012). The dissociation of syllabic token and type frequency effect in lexical decision task. Korean Journal of Cognitive and Biological Psychology, 24(4), 315–328.

Kuznetsova, A., Brockhoff, P. B., & Christensen, R. H. (2017). lmerTest package: Tests in linear mixed effects models. Journal of Statistical Software, 82(13), 1–26.

Lee, E.-B. (1980). kwuk-e sacen ehwi uy lyupyel kwusenghwa lo pon hanca-e uy cwung-yoto wa kyoyukmwuncey. The Society for Korean Language & Literary Research, 8, 136–141. (in Korean).

Lenth, R., Singmann, H., Love, J., Buerkner, P., & Herve, M. (2018). Emmeans: Estimated marginal means, aka least-squares means. R package version, 1(1), 3.

Marslen-Wilson, W. D., Bozic, M., & Randall, B. (2008). Early decomposition in visual word recognition: Dissociating morphology, form, and meaning. Language and Cognitive processes, 23(3), 394–421.

Nakayama, M., Sears, C. R., Hino, Y., & Lupker, S. J. (2014). Do masked orthographic neighbor primes facilitate or inhibit the processing of Kanji compound words? Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 40(2), 813–840.

Okano, K., Grainger, J., & Holcomb, P. J. (2013). An ERP investigation of visual word recognition in syllabary scripts. Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neuroscience, 13(2), 390–404.

Pae, H. K. (2020). Script effects as the hidden drive of the human mind, cognition, and culture. New York, NY: Springer.

Park, K. (1999). Is phonology obligatory in visual access to word meaning? Negative evidence from associative homophone priming in Korean word naming task. Korean Journal of Cognitive and Biological Psychology, 11(1), 17–28.

Perea, M., Nakayama, M., & Lupker, S. J. (2017). Alternating-script priming in Japanese: Are Katakana and Hiragana characters interchangeable? Journal of Experimental Psychology, 43, 1140–1146.

R Core Team (2021). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. https://www.R-project.org/.

Rastle, K., & Davis, M. H. (2008). Morphological decomposition based on the analysis of orthography. Language and Cognitive Processes, 23(7–8), 942–971.

Rastle, K., Davis, M. H., & New, B. (2004). The broth in my brother’s brothel: Morpho-orthographic segmentation in visual word recognition. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 11(6), 1090–1098.

Schmidtke, D., Matsuki, K., & Kuperman, V. (2017). Surviving blind decomposition: A distributional analysis of the time-course of complex word recognition. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 43(11), 1793–1820.

Taft, M. (2004). Morphological decomposition and the reverse base frequency effect. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology Section A, 57(4), 745–765.

Yi, K. (2009). Morphological representation and processing of Sino-Korean words. In Chungmin Lee, Greg B. Simpson, & Youngjin Kim (Eds.), The handbook of East Asian psycholinguistics (pp. 398–408). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Yi, K., & Yi, I. (1999). Morphological processing in Korean word recognition. Korean Journal of Experimental and Cognitive Psychology, 11(1), 77–91.

Yi, K., Jung, J., & Bae, S. (2007). Writing system and visual word recognition: Morphological representation and processing in Korean. The Korean Journal of Experimental Psychology, 19(4), 313–327.

Zhou, X., Marslen-Wilson, W., Taft, M., & Shu, H. (1999). Morphology, orthography, and phonology in reading Chinese Compound words. Language and Cogniive Processes, 14(5/6), 525–565.

Funding

This work was supported by the Ministry of Education of the Republic of Korea and the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF-2020S1A5B5A16083065).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no potential conflict of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bae, S., Pae, H.K. & Yi, K. Modeling morphological processing in Korean: within- and cross-scriptal priming effects on the recognition of Sino-Korean compound words. Read Writ 37, 943–972 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-021-10199-6

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-021-10199-6