Abstract

Prior research finds that mandatory risk factor disclosures are informative in that they increase investors’ assessments of the volatility of a firm’s cash flows. However, the literature is silent as to whether these disclosures provide information about the level of future cash flows and, ultimately, their implications for firm value. We address this question by examining the association between Form 10-K risk factor disclosures and future cash flows levels and stock returns. We use the setting of taxes because it is relatively easier to identify the specific income and cash flow statement line items to which these risks relate, and offer two main results. First, we find that tax risk factor disclosures are positively associated with future cash flows. This suggests that, on average, tax risk factor disclosures relate to tax positions that are rewarded with future tax savings. Second, we find that investors incorporate this relation into stock prices. In additional analysis, we find no evidence of a drift in stock prices, suggesting that investors incorporate the implications of tax risk factor disclosures in a timely manner. Overall, our results suggest that risk factor disclosures provide information about the level of a firm’s future cash flows, that the risks discussed in these disclosures are – on average – value-increasing, and that investors incorporate this information into current stock prices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Beginning in 2005, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) instituted a requirement for firms to include a risk factor section in their Form 10-Ks and 10-Qs to discuss “the most significant factors that make the company speculative or risky.” Prior research finds that mandatory risk factor disclosures are informative in that they increase investors’ assessments of the volatility of a firm’s expected future cash flows (Kravet and Muslu 2013; Campbell et al. 2014; Hope et al. 2016). However, the dividend discount model implies that disclosure can impact firm value by updating beliefs not only about the volatility of a firm’s future cash flows, but also about the level of a firm’s future cash flows. Prior research does not examine whether these disclosures provide a signal about the level of future cash flows and, ultimately, their implications for firm value.

We address this gap in the literature by examining two research questions. First, are firms’ risk factor disclosures associated with future cash flow levels? Second, if so, do investors’ expectations, as reflected in stock prices, reflect this association? We focus our examination on risk factor disclosures about a firm’s taxes because the future cash flow implications of other risk factors (i.e., idiosyncratic risk, systematic risk, financial risk, and legal and regulatory risk) are dispersed throughout the income and cash flow statements. In contrast, cash flows from taxes are more cleanly captured in cash taxes paid and cash effective tax rates.

We first examine whether tax-related risk factor disclosures in the Form 10-K are associated with the level of a firm’s future tax-related cash flows. Higher levels of tax-related risk factor disclosures could indicate that, on average, a firm has taken tax positions that will result in lower taxes paid in the future. If so, then after controlling for taxes paid in the current year, tax-related risk factor disclosures will be negatively related to taxes paid in the future. On the other hand, higher levels of tax-related risk factor disclosures could indicate that a firm has taken tax positions that, on average, draw regulatory scrutiny and result in disallowed tax benefits, fines, and penalties that more than offset any sustainable tax benefits. If so, then tax-related risk factor disclosures will be positively related to taxes paid in the future. Finally, it is possible that, on average, any allowed tax savings are effectively offset by fines and penalties. In this case, the disclosures increase the uncertainty (i.e., volatility) about future cash flows without providing any information about the level of future cash flows.

Using a sample of firms disclosing risk factors from 2005 to 2010, we measure managements’ assessment of tax risks that may impact firm performance with a textual analysis of the Form 10-K risk factor disclosures (i.e., Item 1A). We find a negative association between currently disclosed tax risk factors and firms’ future tax-related cash payments over the next three years. This result is consistent with the notion that managers disclose tax risks that are not excessive (in that they are not associated with higher future tax payments). That is, tax risk factor disclosures reflect tax positions that, on average, result in positive future cash flows. In terms of the economic significance, our evidence suggests that a one-standard-deviation increase in the level of tax risk factor disclosure results in an approximate 1% decrease in the cash effective tax rate (an average $1.6 million, or approximately 50 basis points per year, increase in tax cash flow).

Next, we examine the extent to which investors’ expectations, as reflected in stock prices, reflect this association between tax risk factor disclosures and future cash tax payments. Consistent with investors understanding that tax risk disclosures convey information about future cash flows, we find a positive association between firms’ risk factor disclosures related to taxes and current year stock returns. In additional analysis, we find no evidence of a drift in stock prices, suggesting that investors incorporate the implications of tax risk factor disclosures in a timely manner.

Our results cannot be explained by traditional quantitative measures associated with tax planning such as R&D spending, foreign operations, SG&A and advertising costs, intangible assets, the presence of net operating losses, unrecognized tax benefits, book-tax differences, or cash effective tax rate volatility. Furthermore, our cash flow analyses are robust to specifying a changes regression model, and our returns analyses are robust to the inclusion of firm fixed effects—mitigating the likelihood of a time-invariant correlated omitted variable. Finally, we find that tax risk factor disclosures are associated with higher future tax settlements with the IRS. However, the disclosures are not associated with the future volatility of the cash effective tax rate. Combined with our previous evidence, these results further underscore that tax risk factor disclosures reflect reasonable levels of risk-taking (that is value increasing), rather than excessive risk-taking (that is value decreasing). Overall, our results suggest that risk factor disclosures convey to shareholders that management engages in risk-taking that is, on average, value increasing and that investors appear to incorporate this information into current stock prices.

A few caveats are in order. First, tax risk factor disclosures may be a signal that managers have taken nontax-related operational or investing decisions that also happen to result in tax savings. If so, our tests would nevertheless provide evidence that the disclosures identify those managers who take appropriate levels of risk and earn future returns that are commensurate with that risk. Second, the relation we document between tax risk factor disclosures and future profitability may not generalize to risk factor disclosures of other types (i.e., disclosures about systematic, idiosyncratic, litigation, or financial risks). Future research may wish to examine whether that is indeed the case. Finally, our future profitability tests require that all firms in our sample survive into future time periods. Therefore, our results are subject to a survivorship (or, more specifically, a look-ahead) bias.

We offer several contributions to the literature. First, prior research examines the value relevance of quantitative financial statement disclosures (Amir 1996; Bartov and Mohanram 2014) as well as the effect of quantitative disclosures on market-based assessments of firm risk (Lang and Lundholm 1996; Botosan 1997; Francis et al. 2005a; Francis et al. 2005b; Ashbaugh-Skaife et al. 2009). Specifically related to taxes, research examines the effect of quantitative tax disclosures on market-based assessments of firm risk (Hutchens and Rego 2015; Goh et al. 2016; Guenther et al. 2017). Our study is the first to examine the future cash flow effect and related valuation implications of qualitative risk information (i.e., Form 10-K tax-related risk factor disclosures). Prior research suggests that qualitative disclosure can be more forward-looking and thus have greater predictive ability than quantitative disclosure (e.g., Li 2006). Controlling for the level of a firm’s quantitative disclosures, we provide evidence that, at least in the tax setting, investors incrementally use qualitative risk factor disclosures in current firm valuation decisions and their future cash flow expectations, as reflected in current stock prices, appear to reflect the implications of these disclosures.

Second, we contribute to the literature on qualitative risk factor disclosures. Prior research finds that these disclosures increase investors’ assessments of the uncertainty (or volatility) of a firm’s future cash flows (e.g., Kravet and Muslu 2013; Campbell et al. 2014; Hope et al. 2016). However, the literature is silent as to whether these disclosures provide information about the level of a firm’s future cash flows and, ultimately, their effect on firm value. Our results suggest that, at least in the tax setting, risk factor disclosures not only provide information about the uncertainty of a firm’s cash flows but are also useful in predicting the level of future cash flows and thus in financial statement analysis. More importantly, our results indicate that the information conveyed by tax risk factor disclosures suggests that managers take risks that are value-increasing and thus positively associated with firm value.

Finally, our findings should be of interest to investors and regulators. We provide evidence that tax risk factor disclosures provide insight into the cash-related costs and benefits associated with management risk-taking. Furthermore, as previously mentioned, in 2005 the SEC required firms to periodically disclose risk factors. Recently, the SEC incorporated a project into its agenda to re-examine the disclosure rules related to risk factors. The agency’s concern is that companies are not accurately disclosing their firm-specific risk but instead are providing “generic” and “mind-numbing risk factor discourse” (Johnson 2010). By providing evidence that tax risk factor disclosures are positively related to future cash flows, we provide the SEC with empirical evidence suggesting that firms are disclosing at least some of their specific risks and uncertainties in the newly created risk factor section and that this disclosure is informative to investors. Furthermore, the fact that investors appear to incorporate these disclosures into current stock prices suggests that firms are transparently disclosing the way in which their risk factors translate into future cash flows and thus firm value.

2 Background and hypothesis development

2.1 Background and prior literature on risk factor disclosures

Beginning in 2005, the SEC required the disclosure of qualitative risk information in quarterly and annual filings. Specifically, firms are now required to include in their Form 10-K filing a discussion of significant risk factors that “make the company speculative or risky” and thus might relate to future firm performance (SEC 2005). The requisite risk factor discussion is intended to provide financial statement users supplemental information about company risk and to reduce information asymmetry between management and users of the financial statements. To comply with the risk factor disclosure requirement, management must identify risks and uncertainties that the firm faces, assess the likelihood that those factors may impact the firm, and then choose the most important factors to discuss in the Form 10-K. The SEC’s goal for risk factor disclosures is “to provide investors with a clear and concise summary of the material risks to an investment in the issuer’s securities” (SEC 2005).

Critics of the risk factor disclosure requirements argued that the qualitative disclosures were unlikely to be informative for at least two reasons. First, firms do not have to estimate the likelihood that a disclosed risk will ultimately be realized. Second, firms do not have to quantify the impact that a disclosed risk might have on their current and future earnings or cash flows. Thus managers could simply disclose all possible risks and uncertainties, regardless of the likelihood that they ultimately affect the firm, and the disclosure around these risks and uncertainties is likely to be vague and boilerplate in nature (Malone 2005).

Focusing strictly on the new risk factor disclosure requirements (SEC 2005), Campbell et al. (2014) show that managers’ disclosures of risk factors meaningfully reflect the risks their firms face.Footnote 1 This finding contradicts critics’ assertions that risk factors would be uninformative, vague, and boilerplate.

2.2 Tax risk factor disclosures and future cash flows

In most valuation models (e.g., the dividend discount model), firm value increases with expected future cash flows and decreases with the expected volatility of those cash flows. Therefore disclosures can provide information about firm value in two ways. First, disclosure could indicate that the firm has taken an action that will result in a change in the expected level of a firm’s cash flows. Second, disclosure could indicate that the firm has taken an action that increases the uncertainty about (or volatility of) future cash flows.

Prior research finds that investors respond to risk disclosures through their assessments of the uncertainty (i.e., volatility) of a firm’s expected cash flows (Kravet and Muslu 2013; Campbell et al. 2014; Hope et al. 2016). For example, Kravet and Muslu (2013) investigate the association between changes in risk disclosures and changes in perceived riskiness by the market. They find that increases in risk disclosures are associated with increased stock return volatility and analyst forecast dispersion, suggesting that risk disclosures increase investor perceptions regarding the volatility of a firm’s future cash flows. In addition, Campbell et al. (2014) find that investors incorporate the risk factors into their valuation decisions. Hope et al. (2016) provide further support that, when risk factor disclosures are more specific, investors can better assess a firm’s fundamental risk. Thus prior findings suggest that firms accurately assess the factors that make the firm’s securities speculative and that analysts and investors incorporate this risk into assessments of firms’ fundamental and idiosyncratic risk.

However, prior research has not considered whether risk factor disclosures provide information about the expected level of a firm’s future cash flows. During time periods prior to the risk factor disclosure mandate, Li (2006) counts the number of times the words “risk,” “risks,” “risky,” “uncertain,” “uncertainty,” and “uncertainties” appear in the entire Form 10-K and finds a negative association with future profitability. A conclusion from this study is that managers use risk disclosures to signal bad news or only downside risk, rather than upside risk. However, this study is limited to a narrow set of rather generic words and only covers time periods prior to the mandated risk factor disclosure section (i.e., prior to time periods when managers are required to disclose detailed and specific information about factors that make their firm “particularly speculative or risky”).Footnote 2

As previously discussed, we focus on risk factors related to taxes. There are three possibilities for the association between tax risk factor disclosures and the level of future cash flows related to taxes. First, higher levels of tax-related risk factor disclosures could indicate that the firm has taken tax positions that will result in lower taxes paid in the future. If so, then after controlling for taxes paid in the current year, we would expect the current tax risk factor disclosures to be negatively (positively) associated with taxes paid (cash flows) in the future.Footnote 3

Second, higher levels of tax-related risk factor disclosures could indicate that the firm has taken tax positions that will draw IRS scrutiny and result in a disallowed tax position, fines, or penalties. If so, the disclosures indicate excessive risk-taking levels, and we would expect that current year tax-related risk factor disclosures are positively (negatively) associated with taxes paid (cash flows) in the future.

Finally, there may be no relation between tax-related risk factor disclosures and future tax cash flows, if, for instance, the relation is not strong enough for us to detect an empirical association. It is also possible that, for aggressive tax positions, some tax savings are permitted by the tax authorities while others are disallowed, offsetting such that we are unable to find a significant association. In this instance, the disclosures increase the uncertainty about future cash flows without providing any signal about the level of future cash flows.

We expect that, on average, management will take reasonable levels of tax risks that will result in commensurate positive returns or increases in firms’ future cash flows. That is, we do not expect that the tax positions reflected by risk factor disclosures are particularly aggressive and thus value decreasing. Accordingly, we hypothesize the following relation.

-

H1: Current year tax-related risk factor disclosures are negatively (positively) associated with future taxes paid (cash flow levels).

2.3 Tax risk factor disclosures and firm valuation

Next, we conduct tests to determine the extent to which investors understand the information conveyed by risk factor disclosures. The intention is to explore how the future cash flows implied by the tax risk factor disclosures are impounded into investors’ valuation decisions. Prior literature suggests that investors use quantitative information in their assessments of firm valuation and risk. For example, prior studies examine investors’ pricing of quantitative information disclosed outside of the income statement (Amir 1996), earnings quality (Francis et al. 2005a), and changes in investor pricing resulting from changes in income statement presentation (Bartov and Mohanram 2014).

Recent studies examine the effect of quantitative measures of risk specifically relating to income taxes on investors’ assessments of firm risk (Hutchens and Rego 2015; Goh et al. 2016; Guenther et al. 2017). To our knowledge, however, no empirical evidence exists regarding the association between qualitative Item 1A risk factor disclosures and stock returns. Qualitative risk disclosures may be incrementally important because they are more forward looking and thus better reflect uncertainty than historical, quantitative disclosures. Again, we focus on qualitative tax disclosures (i.e., tax risk factor disclosures) because investors can easily view the quantitative information in the financial statements relating to cash tax payments and associate the quantitative information with the qualitative disclosures.

Given our expectation that tax-related risk factor disclosures are positively associated with the level of future cash flows (from H1) and an expectation that managers take risks and are rewarded commensurately (i.e., that the increase in future cash flows is greater than any increase in the discount rate), we expect that the risk factor disclosures will be positively associated with contemporaneous stock returns.Footnote 4 Our second hypothesis follows.

-

H2: Current year tax-related risk factor disclosures are positively associated with contemporaneous stock returns.

2.4 Textual analysis and our measure of risk factor disclosures

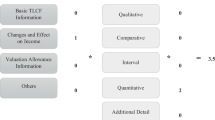

To gather the risk factor data used in our study, we first download annual Form 10-K filings from the SEC’s Electronic Data Gathering, Analysis, and Retrieval (EDGAR) database. We then follow the same procedures as do Campbell et al. (2014) to generate the appropriate risk factor measures. Using the key word dictionary created by Campbell et al. (2014), our qualitative risk factor measures are the aggregation of the number of times each keyword is found in a risk category (i.e., financial, idiosyncratic, systematic, legal/regulatory, and tax).

Campbell et al. (2014) do not explicitly focus on tax keywords, and the environment surrounding taxes has changed significantly since that study in light of the passage of Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) Interpretation Number 48, Accounting for Uncertainty in Income Taxes (FASB 2006). Therefore we augment Campbell et al. (2014)‘s keyword list to more thoroughly capture tax-related risk factors in the disclosure. Specifically, we add the following keywords: “assessment (audit or tax),” “apportion*,” “deductible/nondeductible,” “DTA,” “DTL,” “effective tax,” “foreign tax,” “haven*,” “income shift*,” “indefinitely reinvested,” “Interpretation Number 48,” “Interpretation No. 48,” “jurisdiction,” “permanently reinvested,” “PRE,” “pretax,” “rate difference,” “*repatriate*,” “settle*,” “statutory,” “tax basis,” “tax credit,” “tax expense,” “taxable income,” “tax law,” “tax plan*,” “tax position,” “tax provision,” “tax strategy*,” “transfer pric*,” “trapped cash,” “uncertain tax,” “undistributed foreign earnings,” “unrecognized tax benefit*,” “UTB,” and “valuation allowance.” We also augment Campbell et al. (2014)’s keyword list to remove “property taxes” and “excise taxes,” since these keywords do not relate to income taxes. Appendix A (Table 9) presents all keywords used in our analysis.

To get keyword counts, we require the risk factor disclosure to be in either an html or text file format. Using Perl programming language, we develop code that opens and scans each document for the keywords in Appendix A (Table 9), using regular expressions. The keywords are accessed by the Perl program via a .csv file containing the data in Appendix A (Table 9). After gathering keyword counts for all firm-years and for all risk factor types, we then create our risk factor variables based on the natural log of words in the risk factor disclosure that fall into each disclosure category (i.e., financial, idiosyncratic, legal and regulatory, systematic, and tax).Footnote 5

Appendix B (Table 10) provides descriptive statistics for the count of each individual tax keyword by year scaled by the number of firm observations in that year. The average firm in our sample appears to be disclosing additional tax-related key words over time, going from 12 tax key words in 2005 to 17 tax key words in 2010. This amount appears to increase after the financial crisis of 2008. Furthermore, the most common tax-related word in the risk factor section is the generic term “tax”— appearing approximately seven times in the average firm’s risk factor disclosures. To ensure our results are not driven by this generic term, we remove it from our measures, and all of our results hold. The next most common words appear to be: “apportion(s|ed),” “haven(s),” “jurisdiction,” “settle(s|ed),” and “tax law(s),” which on average appear once for every other firm in our sample. These words are associated with traditional tax planning strategies, such as income shifting and establishing tax havens, and reflect settlements regarding tax planning disputes. Overall, the evidence suggests that our tax key words reflect common tax planning strategies, and the disclosure of these words appears to be increasing over time (with perhaps a spike after the financial crisis of 2008). To alleviate any concerns about time trends in our regression analyses, we include year fixed effects throughout all of our models.

3 Research design and empirical results

3.1 Sample selection for H1

Because we examine future cash flow levels, our analyses require between one and three years of forward-looking information. The SEC mandated risk factor disclosures beginning in 2005. As a result, our sample of firms begins the year the disclosure was required (i.e., 2005) and continues through 2010 (with three-year-ahead data for 2013). We begin with all Compustat firms with available risk factor disclosures and remove any firm-year observations that do not have an industry classification. We remove observations that have negative pretax income or negative tax expense, because negative components make the interpretation of the ETR difficult and loss firms have different tax reporting and planning incentives than profitable firms (e.g., Gupta and Newberry 1997). We also remove observations in which the calculated cash ETR exceeds one (Dyreng et al. 2008). Finally, we remove observations missing necessary data to calculate our control variables and variables of interest. Table 1 Panel A presents details on how we arrive at the final sample for our regressions for H1, using our “One-Year Forward CashFlow sample,” which is the sample based on those observations where our future cash flow (i.e., tax) measures are available in year t + 1.

Panel B of Table 1 classifies our firms based on the Fama and French 12-industry classification method. For ease of presentation, we again present our “One-Year-Forward CashFlow sample.” However, the results are similar across all other samples used in our analyses. The largest industry in our sample is business equipment, which includes computers, software, and electronic equipment. Our sample does not include any utilities firms and has very few firms in the telephone and television transmission industry. Throughout our cash flow analyses, we use industry fixed effects to address any concerns relating to industry concentration.

Table 2 presents descriptive statistics for the variables in our cash flow regressions. In Panel A, we present descriptive statistics partitioned into one-, two-, and three-year forward-looking samples. We present descriptive statistics for our dependent variables, Cash_Taxes and CETR, in years t through t + 3, as well as all current year independent variables used in each analysis. The firms in our sample vary in the amount of cash taxes paid using both Cash_Taxes and CETR. They are also diverse in size and profitability. TaxRiskLog at the bottom quartile suggests that there are some firms in our sample that do not disclose tax risks in their annual risk factor disclosures.Footnote 6 Panels B and C of Table 2 show the mean values for tax-risk word count, TaxRiskLog, Cash_Taxes, one-year CETR, and three-year CETR for each quintile of tax risk disclosures. These panels indicate that cash taxes and cash ETRs decrease monotonically as the tax-risk disclosure quintiles increase. These results further highlight the economic significance and linearity of the relation between tax risk factor disclosures and future tax cash flows.

3.2 Research design for H1: Predictability of tax risk disclosures for future cash flows

Our first hypothesis predicts a negative association between current-year tax risk disclosures and future-year cash tax outflows. To examine H1, we model future cash tax outflows in years t + 1, t + 2, and t + 3 as a function of tax risk factor disclosures, current cash tax outflows, and a set of control variables. Specifically, to test H1, we estimate the following regression model.

where i,t = firm i in year t and CashFlow is our variable capturing cash tax outflows, defined as either Cash_Taxes or CETR. Cash_Taxes equals cash taxes paid (TXPD) scaled by lagged total assets (AT). CETR equals cash taxes paid (TXPD) scaled by pre-tax income (PI) less special items (SPI).Footnote 7 We control for CETR over two alternative periods in tests of Eq. 1. We initially control for a one-year measure of CETR in time t. We then replace the one-year measure with a three-year average measure of CETR calculated over t-2 to t to reduce variation in the year-to-year measure of CETR (Dyreng et al. 2008). We define TaxRiskLog as the natural log of key words identified that relate to tax risks and appear in the firm’s risk factor disclosure section. OtherTaxLog equals the natural log of key words identified in the Form 10-K outside of the firm’s risk factor disclosure section that relate to tax.

If greater tax risk disclosures in one year predict less cash tax outflows in the future (i.e., as predicted by H1), we expect a negative coefficient on TaxRiskLog (i.e., β1< 0). We control for CashFlow in the current year to capture the incremental information provided by qualitative tax risk factor disclosures (e.g., Kim and Kross 2005) beyond the effects of tax strategies currently reflected in Cash_Taxes and CETR. We control for OtherTaxLog to capture additional sources of qualitative and quantitative tax information contained in the Form 10-K (i.e., all tax-related key words located outside of the Item 1A Risk Factors section of the 10-K, such as tax key words in the MD&A and footnotes). Given the range of other tax-related disclosures in the Form 10-K and the lack of prior literature upon which to base our expectations, we make no prediction for the coefficient on OtherTaxLog. It is also possible that the routine use of terms like “tax” and “taxes” within the 10-K inflate the word count for this variable. However, it would not be surprising if a greater number of other qualitative tax disclosures further indicated lower future cash tax savings. If other qualitative tax disclosures indicate firms engage in more value-increasing tax strategies, we expect a negative association between these disclosures and future cash taxes paid (Cash_Taxes) and cash effective tax rates (CETR).

To isolate the marginal impact of TaxRiskLog on future cash flows, we also control for sources of firm risk, firm-specific general complexity, and firm-specific tax complexity. To capture firm risk, we first control for the standard deviation of daily abnormal stock returns prior to the Form 10-K release date (StdRet). We also control for Beta to capture firm-specific risk, relative to the market. We calculate Beta as the slope from a regression of firm-specific daily returns on CRSP value-weighted returns. To the extent that riskier firms generally engage in net value-increasing risky activities, we expect a negative association between future cash tax payments (CashFlow) and our measures of firm risk (StdRet, Beta). If riskier firms generally engage in net value-decreasing risky activities, we expect a positive association between future cash tax payments (CashFlow) and our measures of firm risk (StdRet, Beta).

Prior research suggests that general complexity is associated with firm-specific levels of tax avoidance (e.g., Gupta and Newberry 1997; McGuire et al. 2012). We control for Leverage, defined as the firm’s book value of debt scaled by lagged total assets. Firms with greater leverage have larger tax deductions associated with cash interest paid, so we expect Leverage to be negatively associated with future cash taxes paid (Cash_Taxes) and cash effective tax rates (CETR). To capture firms’ growth opportunities, we control for the firm’s market-to-book ratio (MTB). Firms with greater growth opportunities tend to be earlier in their life cycles and earning larger economic rents, so we expect MTB to be positively associated with future cash taxes paid (Cash_Taxes) and cash effective tax rates (CETR). We control for firm size (Size), calculated as the natural log of total assets. Larger firms tend to have greater tax planning opportunities, so we would expect Size to be negatively associated with future cash taxes paid (Cash_Taxes) and cash effective tax rates (CETR). Finally, considering that complex firms may just generally have longer disclosures, we also control for the overall length of the Form 10-K (10KLength), calculated as the natural log of the total word count from the current year Form 10-K filing. We expect a negative association between 10KLength and future cash taxes paid because complex firms tend to have greater tax planning opportunities.

To further isolate the marginal impact of TaxRiskLog from other tax avoidance characteristics that could influence future cash flows, we control for an array of variables identified in prior literature as influencing firm-level tax avoidance. We include controls for research and development (RD); foreign operations (ForOp); capital expenditures (Capex); selling, general, and administrative expenses (SGA); advertising expenses (Adv); intangibles (Intang); tax loss carryforwards (NOL); unrecognized tax benefits (EndUTB); book-tax differences (BTD); and the volatility of cash ETRs (σCashETR) (e.g., Gupta and Newberry 1997; Dyreng et al. 2008; Dyreng et al. 2010; Guenther et al. 2017). We also include industry and year fixed effects to capture differences in the cash tax measures between industries as well as over time. Additionally, we use White (1980) standard errors clustered by firm to control for both heteroscedasticity and serial correlation in the error terms. Finally, we also estimate a changes model to test how changes in tax risk disclosures impact changes in future tax cash flows and to further address the concern that a time-invariant correlated omitted variable exists.

3.3 Results for H1: Predictability of tax risk disclosures for future cash flows

Table 3 presents multivariate evidence for tests of H1. Panel A presents results from estimating Eq. 1 using Cash_Taxes, one-year CETR, and three-year CETR as the dependent variables in time periods t + 1 through t + 3. We find a significant, negative association between Cash_Taxes and TaxRiskLog in years t + 1 through t + 3 (β1= −0.0003, −0.0005, and − 0.0006, t-statistics = −1.42, −2.07, and − 1.97, respectively). When we use a one-year measure of CETR, we find a significant, negative association between CETR and TaxRiskLog in years t + 1 through t + 3 (β1= −0.0038, −0.0040, and − 0.0046, t-statistics = −2.71, −2.56, and − 2.62, respectively). These results are consistent when we use a three-year average of CETR (β1= −0.0015, −0.0032, and − 0.0055, t-statistics = −1.83, −2.41, and − 3.40, respectively). This evidence is consistent with H1 and suggests that current year risk factor disclosures are associated with positive future cash flows.

Panel B of Table 3 presents results from estimating Eq. 1 as a changes specification. Our results indicate a significant negative association between changes in TaxRiskLog and changes in cash tax flows. These results are consistent with those in Panel A, showing that increased tax risk factor disclosures are associated with increased future cash tax flows.

Taken together, the results from Table 3 indicate that an increase in current year tax risk factor disclosures is associated with increases in the level of a firm’s future cash flows. These results suggest that, on average, firms take risks that are value-increasing. In other words, on average, risk factor disclosures do not reveal that managers have taken risks that are particularly aggressive or represent agency problems that destroy firm value.

3.4 Sample selection for H2

The sample of firms for our stock returns regressions begins with all Compustat firms with available risk factor disclosure data and an industry classification. We remove observations that have negative pretax income or negative tax expense and firms with cash ETR values that exceed one. Finally, we remove any firm-year observations missing data in Compustat needed to calculate control variables or missing data in CRSP necessary to compute buy-and-hold returns for our selected time period of interest. Table 4 Panel A contains details on the final sample for our stock returns analysis (tests of H2).

The sample size in our H2 tests differs from the sample size in our cash flow analysis for two reasons: (1) our cash flow analysis requires data to calculate both current-year and forward-looking measures of cash flows, and (2) our stock returns analysis requires a firm to be covered by CRSP. Therefore some firm-year observations may appear in our cash flow (stock returns) analysis and not appear in our stock returns (cash flow) analysis. However, an untabulated test of differences in the mean of variables common across regressions suggests that our two samples are largely similar. Table 4 Panel B presents descriptive statistics for dependent and independent variables in our stock returns tests. Similar to the descriptive statistics presented for our cash flow sample, TaxRiskLog at the bottom quartile suggests that some firms in our sample do not disclose any tax risks in their annual risk factor disclosures.

3.5 Research design for H2: The association between tax risk disclosures and stock returns

H2 predicts that current year tax risk disclosures are positively associated with stock returns. To test this hypothesis, we examine investor reaction to tax risk disclosures using buy-and-hold returns. Specifically, we follow prior literature (e.g., Dhaliwal et al. 1999; Campbell 2015) and estimate the following model.

where R equals either (1) the annual buy-and-hold return, (2) the annual market-adjusted return for each firm using monthly stock return data from CRSP in year t, or (3) the annual size-adjusted return for each firm. Consistent with prior research, we include delisting returns when available from CRSP. If a return is missing for a delisted return, we assume a − 30% delisting return such that we are certain to have returns for all observations (Shumway 1997). We cumulate returns from month three of year t through month two of year t + 1. We continue our window through month two of year t + 1 so that our return data includes the release of the current year Form 10-K filing, giving investors the opportunity to view the tax-related risk factor disclosures for the current year.Footnote 8 Consistent with prior literature (Dhaliwal et al. 1999; Campbell 2015), we control for ROA, defined as current year income before extraordinary items scaled by lagged total assets, and ΔROA, defined as ROA at time t less ROA at time t-1. Similar to Eq. (1), we control for OtherTaxLog, Leverage, MTB, Size, Beta, and 10KLength.

Similar to H1, we make no prediction for the coefficient on OtherTaxLog. If investors fully incorporate qualitative information from other tax disclosures into their forecasts of taxes paid, then OtherTaxLog should be positively associated with current returns. If investors fail to fully incorporate the information from other current tax disclosures, then OtherTaxLog may be positively associated with future returns as well. We make no prediction on Leverage. Prior research finds that leverage (and default risk) is positively related to expected returns (Dhaliwal and Reynolds 1994). However, prior research also suggests that firms shift away from tax planning strategies and increase levels of debt around changes in tax disclosure requirements (Song and Tucker 2008). If investors perceive an increase in debt as a decrease in net-cash saving tax planning, we may find a negative relation between Leverage and returns.

The coefficient on MTB will be positive if growth opportunities are positively related to firm risk and thus higher expected returns (Fama and French 1993). However, if market participants have a negative outlook for the firm’s future prospects, the firm could be riskier, and we would find a negative coefficient on MTB. Therefore we do not predict the sign of the coefficient on MTB. We expect the coefficient on Size to be negative if larger firms are more stable and thus have lower expected returns (Fama and French 1993). However, larger firms may face a greater risk of litigation and thus would experience higher expected returns (i.e., the political cost hypothesis from Watts and Zimmerman 1986). Prior research finds that investors demand greater returns for riskier firms, so we would expect Beta to be positively associated with stock returns (e.g., Fama and MacBeth 1973). We make no prediction on 10KLength. If investors fully incorporate the information from the Form 10-K, then 10KLength should be associated with current returns. If, however, investors fail to fully incorporate the information from the Form 10-K, then 10KLength may be associated with future returns as well.

Finally, similar to Eq. (1), we control for an array of variables identified in prior literature as influencing firm-level tax avoidance. We control for these variables to capture any investor pricing of tax information contained in quantitative disclosures. We include controls for research and development (RD); foreign operations (ForOp); capital expenditures (Capex); selling, general, and administrative expenses (SGA); advertising expenses (Adv); intangibles (Intang); tax loss carryforwards (NOL); unrecognized tax benefits (EndUTB); book-tax differences (BTD); cash ETRs (CETR); and the volatility of cash ETRs (σCashETR) (e.g., Gupta and Newberry 1997; Dyreng et al. 2008; Dyreng et al. 2010; Guenther et al. 2017). We include firm and year fixed effects and use White (1980) standard errors clustered by firm to control for both heteroscedasticity and serial correlation. If investors positively value tax risk disclosures (as predicted by H2), we expect β1 to be positive (i.e., β1>0).

3.6 Results for H2: The association between tax risk disclosures and current stock returns

Table 5 presents multivariate evidence for buy-and-hold returns (Raw Returns), market-adjusted returns (Market-Adjusted Returns), and size-adjusted returns (Size-Adjusted Returns). We find a significant, positive association between each of these return measures and TaxRiskLog (β1 = 0.0301, 0.0233, and 0.0220, t-statistics = 1.99, 1.79, and 1.80, respectively for raw, market-adjusted, and size-adjusted returns). A one standard deviation increase in TaxRiskLog translates into an increase in raw (market-adjusted, size-adjusted) returns of 4.2% (3.3%, 3.1%). This evidence is consistent with H2 and suggests that investors incorporate the information conveyed by tax risk disclosures in their contemporaneous assessments of firm value. Taken together, our results for H1 and H2 suggest that tax risk factor disclosures are qualitative predictors of increases in the level of a firm’s future cash flows, reflecting the fact that otherwise risk-averse managers are engaging in reasonable (and value increasing) levels of tax planning, rather than excessive (and value destructive) risk-taking.

4 Additional analysis

In this section, we perform a number of additional analyses and sensitivity tests regarding the inferences from our two formal hypotheses. First, we examine future stock returns to assess whether investors fully price the information about future cash flows that is conveyed by tax risk factors at the time the disclosure is made or whether there is a predictable drift in stock prices once the realizations of future cash flows occur. Next, we reconcile our stock price results with the prior literature that finds that risk factor disclosures are positively associated with firms’ cost of capital (Campbell et al. 2014). We then consider whether risk factor disclosures provide information about particularly “risky” tax strategies by assessing whether they are associated with income tax rate volatility, settlements with the IRS, or both. Then we ensure that our results related to tax risk factor disclosures are robust to controlling for risk factor disclosures from other types of risk (i.e., systematic, idiosyncratic, financial, and litigation risks). Finally, we discuss the potential for correlated omitted variables and the limitations and caveats that are necessary for a complete understanding of our analyses.

4.1 Additional analysis—Future stock returns

First, we examine whether investors fully price information from the tax risk factor disclosures in the current year. Investors may not fully incorporate the implications of currently disclosed risk factors into firm value if they do not fully understand the disclosures or consider them as relevant at the time. This possibility exists given the complex nature of the risk disclosure information, the way in which it is presented, and the lack of extensive preparation guidance for firms. Even though the SEC published a “Plain English Disclosure” document to assist firms in making their risk factor disclosures easier to read, many firms continue to obscure risks by presenting information in excessive detail, combining several related risks under one subheading, using vague or generic subheadings, and presenting risks that could apply to any firm (SEC 1999). Further, the tax-related risk factor disclosures may be particularly ambiguous, as they have the potential to reflect tax policies and strategies that are inherently complex (Neuman et al. 2013).

Prior theoretical, archival, and experimental research suggests that investors underreact to information that is costly to process, complex, or less salient (Bloomfield 2002; Hirshleifer and Teoh 2003). Additionally, research shows that expectations of unsophisticated investors can affect asset prices (Ayers et al. 2011) and that high arbitrage risk and transaction costs prevent sophisticated investors from correcting accounting-based anomalies (Collins et al. 2003; Ali et al. 2003). If investors do not fully understand the future cash flow implications of tax risk factor disclosures and underreact to the disclosures in the current period, they will be surprised once the impacts on cash flows begin to emerge as cash taxes paid.

To examine whether investors underreact to information in the tax risk factor disclosures, we expand our analysis from Table 5 over two additional time horizons (following Campbell 2015). All information necessary to compute the variables in our future returns analyses is available at the time the return window opens. In the first set of columns in Panel A of Table 6, we cumulate returns from month three of year t through month two of year t + 2 (one-year horizon). In the second set of columns in Panel A, we cumulate returns from month three of year t through month two of year t + 3 (two-year horizon). If investors underreact to the information in tax risk factor disclosures, we should see that the association between risk factor disclosures and returns (β1) is significantly more positive than it is in Table 5 and that it becomes increasingly more positive as the horizon increases. In Panel A of Table 6, we continue to find a significant, positive association between R and TaxRiskLog over the one-year horizon. (β1 = 0.0374, 0.0242, and 0.0249 and t-statistics = 1.81, 1.71, and 1.83, respectively, for raw, market-adjusted, and size-adjusted returns). Also in Table 6 Panel A, we find a positive association between R and TaxRiskLog over the two-year horizon (β1 = 0.0395, 0.0259, and 0.0258 and t-statistics = 1.75, 1.70, and 1.75). However, our untabulated tests suggest that the associations with current and future returns documented in Panel A of Table 6 are not statistically different from the associations with current returns documented in Table 5.

To further isolate whether investors underreact to the information conveyed by tax risk factor disclosures, in Table 6 Panel B, we estimate Eq. (2) cumulating returns over two single-year horizons. That is, we examine whether there is any statistical association between tax risk factor disclosures and one-year-ahead returns (returns beginning in month three of year t + 1 and running through month two of year t + 2) and two-year-ahead returns (returns beginning in month three of year t + 2 and running through month two of year t + 3). We find no evidence of any association between tax risk factor disclosures and future returns in these regressions.Footnote 9

Taken together, the results in Tables 5 and 6 lead to the following conclusions. First, contemporaneous stock prices appear to reflect the information conveyed by current year tax risk factor disclosures. Second, we find no evidence of a drift in stock prices, suggesting that investors incorporate the implications of tax risk factor disclosures in a timely manner.

4.2 Reconciliation between stock returns and cost of capital/discount rate

As previously discussed, prior research documents that risk factor disclosures are positively associated with firms’ cost of capital (Campbell et al. 2014). Ceteris paribus, this would lead to a decrease in firm value as the uncertainty of expected future cash flows increases. However, because the risks that managers take appear to yield positive future cash flows (H1) and a contemporaneous increase in firm value (H2), our results imply that any increases in cost of capital are offset by increases in future cash flows (i.e., risk factor disclosures suggest that managers take reasonable amounts of risk that increases firm value overall). Nevertheless, if we strictly focus our empirical tests on a firm’s cost of capital, we should be able to replicate Campbell et al. (2014)’s finding that tax risk disclosures are associated with increases in cost of capital.

Following Campbell et al. (2014), we measure cost of capital as firm beta, equal to the slope in a regression of firm-specific daily returns on CRSP value-weighted returns over the 60 days following the year t Form 10-K release. In Table 7, we document a positive association between tax risk disclosures and changes in firms’ cost of capital soon after the Form 10-K release date (β1 = 0.0092, t-statistic = 1.87). These results confirm prior findings and—together with our tests of H1 and H2—suggest that tax risk factor disclosures (1) increase the uncertainty of firms’ expected future cash flows (i.e., cost of capital), (2) are associated with increases in the level of firms’ expected future cash flows (i.e., H1), and (3) indicate that the effect of increases in the level of firms’ expected future cash flows dominates the effect on their uncertainty, resulting in an increase in firm value (i.e., H2).

4.3 Tax risk factors—Efficient risk taking or excessive risk taking?

Our measure is based on disclosures of tax risk, rather than actual tax risk, and the possibility exists that firms may not be forthcoming with their risk disclosures (particularly if those risks might be perceived as excessive). Therefore an alternative explanation to the notion that firms are taking reasonable (and sustainable) tax risks is that firms in our sample only disclose tax risks that are reasonable (and sustainable) in the first place. To mitigate the likelihood that firms are taking tax risks and not disclosing those risks, we control for quantitative measures of tax risk (e.g., cash ETR volatility, UTBs, and BTDs as well as other determinants of these items). Further, we do not conclude that firms are optimizing their tax risks. That is, because we do not know a firm’s optimal level of tax risk taking, firms may take excessive (greater than optimal) tax risks. In this section, we further examine whether management engages in reasonable levels of risk taking by assessing the association between current tax risk disclosures and a measure of excessive tax risk taking.

4.3.1 Predictability of current tax risk disclosures for future cash ETR volatility

To assess whether tax risk factor disclosures are associated with excessive tax risk taking, we examine the association between tax risk factor disclosures (TaxRiskLog) and the volatility of a firm’s cash effective tax rate (CETR_Std). Specifically, we re-estimate Eq. (1), replacing CashFlow with CETR_Std, calculated as the five-year standard deviation of the annual cash effective tax rate measured over time t + n to t + n-4. If risk factor disclosures convey that managers are taking excessive risks, we expect a positive relation between TaxRiskLog and CETR_Std. If, however, tax risk factor disclosures indicate that managers have taken reasonable levels of risk, we would not expect to find an association between TaxRiskLog and CETR_Std.

Panel A of Table 8 presents the results of estimating Eq. (1) using CETR_Std as the dependent variable. We find no statistical significance between tax risk factor disclosures and effective tax rate volatility. Taken with our previous evidence, these results suggest that managers’ risk factor disclosures accurately reflect current risks taken by the firm, that these risk factor disclosures reflect tax strategies that are net value-increasing, and that these disclosures provide information on firms’ reasonable tax strategies (i.e., managers do not appear to take positions that are unsustainable).

4.3.2 Informativeness of tax risk disclosures for tax authorities

While research on risk factor disclosures has focused on investors’ use of the information (e.g., Kravet and Muslu 2013; Campbell et al. 2014; Hope et al. 2016), other parties, such as tax authorities, may also use this information. To the extent that tax authorities find these disclosures informative, we would expect that firms with more tax keywords in their risk factor disclosures would have larger future payouts to tax authorities, resulting from tax audits. To examine whether tax authorities find these disclosures informative, we re-estimate Eq. (1), replacing CashFlow with Settle, calculated as the decrease in unrecognized tax benefits relating to settlements with taxing authorities scaled by lagged total assets. If taxing authorities find these disclosures informative, we expect to find a positive association between current tax risk factor disclosures and future tax settlements paid (Settle). If, however, taxing authorities do not use these risk factor disclosures in their audit decisions, we may fail to find a significant association.

Panel B of Table 8 presents the results of re-estimating Eq. (1) using Settle as the dependent variable. Consistent with the risk factor disclosure being informative to taxing authorities, we find a positive, significant association between TaxRiskLog and Settle in both t + 1 and t + 2 (β1 = 0.0001 and 0.0001, t-statistic = 2.21 and 2.52, respectively). This evidence supports the argument that firms’ tax risk disclosures are positively associated with future cash flows because firms benefit from such increased risk taking. That is, while these results suggest that taxing authorities challenge firms’ future risky tax positions, combined with our results in Table 3, our overall evidence indicates that firms are engaging in net cash flow-increasing and firm value-increasing tax strategies that account for taxing authority settlements.

4.4 Informativeness of risk factor disclosures that are unrelated to taxes

Our tests focus on future tax-related cash flows (i.e., Cash_Taxes and CETR), and that is why we use tax risk factor disclosures as our main variable of interest. If our results were explained by risk-taking (and risk disclosures) unrelated to tax, it is not clear why we would find associations with future tax-related cash flows. Nevertheless, to further validate that our results cannot be explained by nontax risk-taking (i.e., risk factors related to financial, idiosyncratic, legal/regulatory, and systematic risk), we perform two additional tests.

First, we use principal component analysis to identify the number of broad constructs of risk represented by risk factor disclosures. Our untabulated results suggest that all five risk factor categories meaningfully contribute to one common component (each with loadings >0.40). Perhaps more importantly, the results from our principal component analysis suggest that the tax risk factor disclosure is incremental to the risk levels explained by this common component.

Second, we expand our original tests of Eq. (1) to control for the additional four categories of risk factors. If the tax risk factor disclosure is incrementally informative about future cash flows, we should continue to find a significant, negative relation between TaxRiskLog and Cash_Taxes (CETR), even after controlling for the additional four categories of risk factors. In untabulated results, we find that our inferences are unaffected by the inclusion of these additional control variables.

Overall, the results in this section provide reasonable assurance that our results are due to the effects of tax-related risk taking on future tax-related cash flows. However, it is fundamentally difficult to separate the tax effects from the underlying operating/investing decisions that generate those tax effects. Thus tax risk factor disclosures may predict future cash flows beyond tax-specific cash flows because they are useful in identifying managers who take appropriate risks and earn commensurate returns.

4.5 Correlated omitted variables, limitations, and caveats

As with all empirical research, we cannot fully rule out the possibility that a correlated omitted variable exists. We have included all control variables known to be related to future performance as well as to tax planning. To further mitigate the likelihood that a correlated omitted variable exists, we specify a changes model for our future cash flows tests (in Panel B of Table 3), and we include firm fixed effects in our stock returns regression models. These specifications control for any time-invariant correlated omitted variable concern. Our test results are also robust to the inclusion of year fixed effects.

Finally, we note some necessary limitations and caveats related to our results. First, tax risk factor disclosures may be a signal that managers have taken nontax related operational or investing decisions that also happen to result in tax savings. If this is the case, our tests would nevertheless provide evidence that the disclosures identify those managers that take appropriate levels of risk and earn future returns that are commensurate with that risk. Second, the relation we document between tax risk factor disclosures and future profitability may not generalize to risk factor disclosures of other types (i.e., disclosures about systematic, idiosyncratic, litigation, or financial risks). Future research may wish to examine whether that is indeed the case. Finally, our future profitability tests require that all firms in our sample survive into future time periods. Therefore our results are subject to a survivorship (or, more specifically, a look-ahead) bias.

5 Conclusion

Prior research finds that mandatory risk factor disclosures are informative in that they increase investors’ assessments of the uncertainty (or volatility) of a firm’s future cash flows (Kravet and Muslu 2013; Campbell et al. 2014; Hope et al. 2016). However, the literature is silent as to whether these disclosures provide information about the level of future cash flows and, ultimately, their effect on firm value. We address this question by examining the association between risk factor disclosures and future cash flows levels as well as current and future stock returns. We focus on the setting of taxes because it is easier to identify the specific income statement and cash flow statement line items to which these risk disclosures relate.

We offer two main results. First, we find that tax risk factor disclosures are positively associated with future cash flows. This finding suggests that, on average, managers are taking reasonable levels of risk, as risky tax positions are rewarded with future tax savings. Second, we find that investors appear to incorporate this relation into stock prices at the time of the risk factor disclosure. In additional analysis, we find no evidence of a drift in stock prices, suggesting that investors incorporate the implications of tax risk factor disclosures in a timely manner. Overall, our results suggest that risk factor disclosures provide information about the level of a firm’s future cash flows, that the risks discussed in these disclosures are—on average—value-increasing, and that investors incorporate this information into current stock prices.

We acknowledge that it is fundamentally difficult to separate the tax effects from the underlying operating/investing decisions that generate those tax effects and therefore our evidence in this regard cannot be definitive. In fact, tax risk factor disclosures may predict future cash flows beyond tax-specific cash flows because they are useful in identifying managers who take appropriate risks and earn commensurate returns. We document that, on average, qualitative tax risk disclosures predict positive future cash flows and stock returns. Future research may wish to examine cross-sectional settings where qualitative risk disclosures provide signals that managers have taken overly aggressive risks that result in a reduction in future cash flows and stock returns. Furthermore, future research may wish to examine the extent to which qualitative nontax risk disclosures predict future cash flows and stock returns.

Notes

Campbell et al. (2014) identify five major categories of risk factors that are disclosed in the Form 10-K filing. They are financial risk, idiosyncratic risk, systematic risk, legal and regulatory risk, and tax risk. They define financial risk as those risks related to liquidity, debt, and capital structure, while idiosyncratic risk and systematic risk relate to firm stock price volatility and market volatility, respectively. Legal and regulatory risk encompasses issues related to legal matters, lawsuits, and intellectual property, and tax risk includes accounting for taxes or tax avoidance schemes.

In untabulated results, we control for Li (2006)’s risk word measure, and our results are unchanged.

Our research design uses the firms themselves as their own benchmarks with respect to tax risk disclosures and tax-based cash flows, and our models include controls for current year taxes paid and quantitative tax risk variables as well as other important firm-level characteristics and industry and year fixed effects.

If the discount rate increases (as suggested by Campbell et al. 2014) and investors do not anticipate a change in a firm’s cash flows, initially a firm’s stock price would decrease. Our expectation in H2 is that investors will anticipate the increase in future profitability and that the overall effect on firm value is increasing. In Table 7, when we focus strictly on empirical tests of the discount rate, we can replicate the findings of Campbell et al. (2014) of an increase in cost of capital in the months around the 10-K filing date. See Section 5.2.

To account for any instances where a firm has zero keywords identified in a particular category, we add one to all word count variables prior to taking the natural log of the word count in our variable creation (i.e., Log(1 + x)). For our tax risk factor disclosure variable classification into quintiles, we include the portion of the sample with zero tax risk disclosures in the lowest quintile prior to separating all other word count observations into quintiles.

To compute TaxRiskLog, we take the raw count of words relating to “tax” in a firm’s risk factor disclosure and add one. We then take the natural logarithm of the resulting value. Therefore a value of 0 for TaxRiskLog indicates that the firm had zero words relating to tax risks in its risk factor disclosure.

Dyreng, Hanlon, Maydew, and Thornock (Dyreng et al. 2017) use an alternative CETR measure, whereby special items (SPI) are not adjusted out of the CETR denominator but are included as a regression control variable in the model. Our results are robust to this alternative variable specification.

For all firms in our sample, we confirm that the return window excludes the prior year 10-K and includes the current year 10-K. We calculate returns over the entire year because firms must update their risk factor disclosures in interim periods and research confirms that such updates occur and are timely (Filzen 2015).

In an untabulated analysis, we control for the four other categories of risk factor disclosures (financial, idiosyncratic, systematic, and legal/regulatory) using the keyword dictionary of Campbell et al. (2014). Our results remain unchanged.

References

Ali, A., Hwang, L., & Trombley, M. A. (2003). Arbitrage risk and the book-to-market anomaly. Journal of Financial Economics, 69, 355–373.

Amir, E. (1996). The effect of accounting aggregation on the value-relevance of financial disclosures: The case of SFAS no. 106. The Accounting Review, 71(4), 573–590.

Ashbaugh-Skaife, H., Collins, D. W., Kinney Jr., W. R., & LaFond, R. (2009). The effect of SOX internal control deficiencies on firm risk and cost of equity. Journal of Accounting Research, 47(1), 1–43.

Ayers, B. C., Li, O. Z., & Yeung, P. E. (2011). Investor trading and the post-earnings-announcement drift. The Accounting Review, 86(2), 385–416.

Bartov, E., & Mohanram, P. S. (2014). Does income statement placement matter to investors? The case of gains/losses from early debt extinguishment. The Accounting Review, 89(6), 2021–2055.

Bloomfield, R. J. (2002). The "incomplete revelation hypothesis" and financial reporting. Accounting Horizons, 16(3), 233–243.

Botosan, C. (1997). Disclosure level and the cost of equity capital. The Accounting Review, 72(3), 323–350.

Campbell, J. L. (2015). The fair value of cash flow hedges, future profitability, and stock returns. Contemporary Accounting Research, 32, 243–279.

Campbell, J. L., Chen, H., Dhaliwal, D. S., Lu, H., & Steele, L. B. (2014). The information content of mandatory risk factor disclosures in corporate filings. Review of Accounting Studies, 19(1), 396–455.

Collins, D. W., Gong, G., & Hribar, P. (2003). Investor sophistication and the mispricing of accruals. Review of Accounting Studies, 8, 251–276.

Dhaliwal, D., & Reynolds, S. (1994). The effect of the default risk of debt on the earnings response coefficient. The Accounting Review, 69(2), 412–419.

Dhaliwal, D., Subramanyam, K. R., & Trezevant, R. (1999). Is comprehensive income superior to net income as a measure of firm performance? Journal of Accounting and Economics, 26, 43–67.

Dyreng, S. D., Hanlon, M., & Maydew, E. L. (2008). Long-run corporate tax avoidance. The Accounting Review, 83(1), 61–82.

Dyreng, S. D., Hanlon, M., & Maydew, E. L. (2010). The effects of executives on corporate tax avoidance. The Accounting Review, 85(4), 1163–1189.

Dyreng, S. D., Hanlon, M., Maydew, E. L., & Thornock, J. R. (2017). Changes in corporate effective tax rates over the past 25 years. Journal of Financial Economics, 124(3), 441–463.

Fama, E., & French, K. (1993). Common risk factors in the returns on stock and bonds. Journal of Financial Economics, 33, 3–56.

Fama, E., & MacBeth, J. (1973). Risk, return, and equilibrium: Empirical tests. The Journal of Political Economy, 81(3), 607–636.

Filzen, J. (2015). The information content of risk factor disclosures in quarterly reports. Accounting Horizons, 29(4), 887–916.

Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB). (2006). Interpretation No. 48 (FIN 48): Accounting For Uncertainty in Income Taxes: An Interpretation of FASB Statement No. 109. Norwalk, CT: Financial Accounting Standards Board.

Francis, J., Khurana, I. K., & Pereira, R. (2005a). Disclosure incentives and effects on cost of capital around the world. The Accounting Review, 80(4), 1125–1162.

Francis, J., LaFond, R., Olsson, P., & Schipper, K. (2005b). The market pricing of accruals quality. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 39(2), 295–327.

Goh, B. W., Lee, J., Lim, C. Y., & Shevlin, T. (2016). The effect of corporate tax avoidance on the cost of equity. The Accounting Review, 91(6), 1647–1670.

Guenther, D. A., Matsunaga, S. R., & Williams, B. M. (2017). Is tax avoidance related to firm risk? The Accounting Review, 92(1), 115–136.

Gupta, S., & Newberry, K. (1997). Determinants of the variability in corporate effective tax rates: Evidence from longitudinal data. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 16(1), 1–34.

Hirshleifer, D., & Teoh, S. H. (2003). Limited attention, information disclosure, and financial reporting. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 36, 337–386.

Hope, O.-K., Hu, D., & Lu, H. (2016). The benefits of specific risk-factor disclosures. Review of Accounting Studies, 21(4), 1005–1045.

Hutchens, M., & Rego, S. (2015). Does greater tax risk lead to increased firm risk? Working paper, Indiana University.

Johnson, S. (2010). SEC pushes companies for more risk information. CFO Magazine. http://ww2.cfo.com/risk-compliance/2010/08/sec-pushes-companies-for-more-risk-information/.

Kim, M., & Kross, W. (2005). The ability of earnings to predict future operating cash flows has been increasing-not decreasing. Journal of Accounting Research, 43(5), 753–780.

Kravet, T., & Muslu, V. (2013). Textual risk disclosures and investors’ risk perceptions. Review of Accounting Studies, 18, 1088–1122.

Lang, M. H., & Lundholm, R. J. (1996). Corporate disclosure policy and analyst behavior. The Accounting Review, 71(4), 467–492.

Li, F. (2006). Do stock market investors understand the risk sentiment of corporate annual reports? Working paper, University of Michigan.

McGuire, S. T., Omer, T. C., & Wang, D. (2012). Tax avoidance: Does tax-specific industry expertise make a difference? The Accounting Review, 87(3), 975–1003.

Neuman, S., Omer, T., & Shelley, M. (2013). Corporate transparency, sustainable tax strategies, and uncertain tax activities. Working Paper, Texas A&M University.

Malone, S. (2005). Refco risks boiler-plate disclosure. Reuters. http://w4.stern.nyu.edu/news/news.cfm?doc_id=5094.

Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). (1999). Division of Corporation Finance: Updated Staff Legal Bulletin No. 7, “Plain English Disclosure.” June 7, 1999. https://www.sec.gov/interps/legal/cfslb7a.htm.

Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). (2005). Securities and exchange commission final rule, release no. 33–8591 (FR-75). http://www.sec.gov/rules/final/33-8591.pdf.

Shumway, T. (1997). The delisting bias in CRSP data. Journal of Finance, 52(1), 327–340.

Song, W., & Tucker, A. L. (2008). Corporate tax reserves, firm value, and leverage. Working paper, Louisiana State University, Pace University.

Watts, R., & Zimmerman, J. (1986). Positive accounting theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

White, H. (1980). A heteroskedasticity-consistent covariance matrix estimator and a direct test for heteroskedasticity. Econometrica, 48(4), 817–838.

Acknowledgements

We are thankful for helpful comments and suggestions from an anonymous reviewer, Ted Christensen, James Chyz, Dan Dhaliwal, Jenna D’Adduzio, Josh Filzen, Xinjiao “Jenny” Guan, Lisa Hinson, Jeff Hoopes (discussant), Jing Huang (discussant), Todd Kravet, Hai Lu, Russ Lundholm, Volkan Muslu, Santhosh Ramalingegowda, Bob Resutek, Bridget Stomberg, Jake Thornock, Karen Ton (discussant), Erin Towery, Ben Whipple, the University of Georgia tax readings group, and workshop participants at the American Accounting Association (AAA) Southeast Regional Meeting, the American Accounting Association (AAA) Annual Meeting, and the Financial Accounting and Reporting Section (FARS) Midyear Meeting. John Campbell gratefully acknowledges the financial support of a Terry Sanford Research Grant from the Terry College of Business at the University of Georgia.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Campbell, J.L., Cecchini, M., Cianci, A.M. et al. Tax-related mandatory risk factor disclosures, future profitability, and stock returns. Rev Account Stud 24, 264–308 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11142-018-9474-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11142-018-9474-y