Abstract

Public reason is justified to the extent that it uses (only) arguments, assumptions, or goals that are allowable as “public” reasons. But this exclusion requires some prior agreement on domains, and a process that disallows new unacceptable reasons by unanimous consent. Surprisingly, this problem of reconciliation is nearly the same, mutatis mutandis, as that faced by micro-economists working on general equilibrium, where a conceit—tâtonnement, directed by an auctioneer—was proposed by Leon Walras. Gaus’s justification of public reason requires the “as if” solution of a Kantian Parliamentarian, who rules on whether a proposal is “in order.” Previous work on public reason, by Rousseau, Kant, and Rawls, have all reduced decision-making and the process of “reasoning” to choice by a unitary actor, thereby begging the questions of disagreement, social choice, and reconciliation. Gaus, to his credit, solves that problem, but at the price of requiring that the process “knows” information that is in fact indiscernible to any of the participants. In fact, given the dispersed and radical situatedness of human aims and information, it is difficult for individuals, much less groups, to determine when norms are publicly justified or not. More work is required to fully take on Hayek’s insight that no person, much less all people, can have sufficient reasons to endorse the relevant norm, rule or law.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

For enlightenment of this kind, all that is needed is freedom. And the freedom in question is the most innocuous form of all—freedom to make public use of one’s reason in all matters. But I hear on all sides the cry: Don’t argue! The officer says: Don’t argue, get on parade! The tax-official: Don’t argue--pay! The clergyman: Don’t argue, believe! All this means restrictions on freedom everywhere. But which sorts of restriction prevents enlightenment, and which, instead of hindering it, can actually promote it? I reply: The public use of man’s reason must always be free, and it alone can bring enlightenment among men. (Kant, 2010:3)

1 Introduction

Kant’s invocation of “public reason” seems paradoxical. On one hand, the freedom that enlightenment requires must allow any argument to be made, and so to be heard. But Kant himself placed strict limits on the form of arguments, and motivations for arguments, that can be allowed to be advanced as moral justifications. The society must be allowed to argue about any subject, but some arguments are out of order. Who determines what amendments are in order and which cannot be considered?

On first glance, Kant appears to be thinking…of himself. And maybe a few other really smart people, identified as being smart because they make the sort of arguments that smart people make: “[B]y the public use of one’s own reason I mean that use which anyone may make of it as a man of learning addressing the entire reading public.” (Kant, 2010: 3). But this would be a tendentious reading. Kant is actually thinking of standards and justification that the community over time has come to endorse. The advantage of this approach is obvious: “men of learning” only make the sorts of arguments that would be allowed in an informed debate that accepts cultural truths and respects norms that learned people would all agree should be respected.

Gaus (2011) is an extremely important book, one that takes seriously the problem of “public reason” for the purposes Kant laid out. After all, Kant claimed that this “spirit of freedom” was spreading fast, and that “Men will of their own accord gradually work their way out of barbarism so long as artificial measures are not deliberately adopted to keep them in it” (Kant, 2010: 9). But Gaus wants to argue that the origins and constraints on public reason can be decentralized, and that cooperation can emerge out of public reason in a way that really will allow societies to “work their way out of barbarism.”

Gaus’s process of decentralized emergence of agreement over norms and goals is surprisingly isomorphic with Hayek’s claims about the process of decentralized emergence of agreement over the values of resources in an economy using the price system. No one individual in an economy knows enough to be able to value all resources and thereafter direct them toward higher-valued uses. But the unfettered market system, “so long as artificial measures are not deliberately adopted” to prevent price adjustments, will adjust toward an aggregate summary of the subjective assessments of values held by all the individuals in the society. We don’t have to agree on “value,” because we can agree on a “price.” If your value of the object is greater than the price, and mine is less, you may well want to buy it from me, and I’ll be happy to sell it. Our agreement is on the mutual benefit resulting from that transaction. Our disagreement about subjective value is actually the source of the gains from trade: we disagree about a value, so we have good reasons to agree on a price.

What is the analogue to the market as a process for yielding subjective truths for public reason? The heart of Gaus’s project is to ask “whether free and equal persons can all endorse a common political order even though their private judgments about the good and justice are so often opposed.” (Gaus 2011: 2). In other words, given the initial disagreement, is there an institution that will lead to mutual benefit and cooperation in a justified moral system, as the disagreement over value leads in markets to an agreement over price?

The analogy to market equilibrium is important because, as in the convergence to public reason, the mechanism used to animate convergence in general equilibrium theory—the “Walrasian Auctioneer” (Walras 1877, 1899) –gives an “as if” role to human agency. I will argue that Gaus needs an analogous sentient human actor—the “Kantian Parliamentarian”—to make his system converge to workable “public reasons.”.Footnote 1

For Hume, and then for Hayek, the process of emergence of laws (as opposed to legislation) is based on trial and error, using as a selection mechanism the relative prosperity and success of groups who organize their societies using just those rules. Other groups might mimic the good rules, or the good rules might win out through expansion of territory or prosperity. But the important thing is that the (ex post) good consequences could not have been known in advance because of pervasive ignorance and dispersed knowledge. Gausian public justifications are known in advance, and in fact must be justified in advance by reason. But the society can’t proceed without information necessarily unavailable to it. Vallier (2011) called this problem “the indiscernibility of justificatory reasons.” No one individual has enough moral knowledge to be able to do what public reason requires if it is going to work as Gaus proposes. For an outcome to qualify as a fully justified public reason, the society must solve a large-scale coordination problem with many independent agents who have never met, have different information and different experiences, and who disagree about both ends and means.

Gaus is clear about how the equilibrium—once chosen—can be policed by social opinion and disapproval.

The problem is not mutual authority but dispersed authority. Once a society of free and equal persons has coordinated on specific moral rules and their interpretation, the point of invoking moral authority is to police this equilibrium selection against “trembling hands”—individuals who make mistakes about what rule is in equilibrium—and those who otherwise fail to act on their best reasons. In these cases the overwhelming social opinion concurs in criticizing deviant behavior. An individual who violates the social equilibrium will not simply be able to check demands on her, for she will meet the same demand from almost all others. In Mill’s terms, the deviant will not simply confront the opinion of other individuals but of “society.” (pp. 47-48; emphasis added).

The problematic assumption is italicized. How does this initial coordination take place, and by what rules, if we have not yet agreed on rules, and know that we disagree? We cannot simultaneously have (1) a set of moral intuitions in a society arrived at by some essentially random historical process and therefore justified ex post; (2) a publicly justified justificatory reason arrived at using a priori reasoning; and (3) a societal judgment that will police deviants who disagree. The problem is that societal judgments are actually derived from traditions, and defend traditions. If these traditions are optimal, then all is well. But “optimal” is a high standard, and in any case the needs of society are dynamic, so that optimality if it exists is evanescent. How can a large group of people preserve good rules and yet move to better rules if deviance is punished?

Gausian public reason requires that public justifications be more rationally or epistemically accessible to members of the public than can reasonably be expected, given how the dispersed nature of reasoning makes it extremely hard to reconcile or even discuss. I will argue that to make this work one needs an additional actor, the Kantian Parliamentarian, to police both the original equilibrium selection and subsequent resolution of disagreements at the stage of convergence, ruling certain claims out of bounds. To see how this might work we must first examine the use of the “Auctioneer” in economics, to understand the analogy.

2 The “single price” doctrine: an auctioneer vs. human action

One of the core laws of economics is the so-called “doctrine of single price.” This might be stated several ways, but the essential insight is that any “equilibrium,” or steady state of market processes, must allow no unexploited arbitrage opportunities. Therefore, subject to costs of time, transportation, and information, it must be true that no units of a homogeneous commodity (or financial asset) can be offered at different prices. The proof is by contradiction: suppose not. Then there exists either a buyer who pays more than the minimum price available, or a seller who accepts less than the maximum price available, for the same commodity. Barring the operation of some other motive (charity, irrationality, etc.), such a difference in prices is not consistent with the exhaustion of all available mutually beneficial trades.

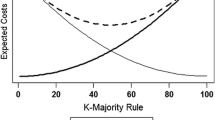

But could it be that all markets are simultaneously in equilibrium? If at least one equilibrium price vector exists, then somehow it must be identified and implemented. And it is not clear how this might be done. So a mythical creature, The Walrasian “Auctioneer,” was created as the moving part—the active agent—in the problem. The auctioneer follows a simple rule: observe the result of a particular price vector, chosen somehow. Some markets will exhibit negative excess demand (surpluses), and some will exhibit positive excess demand (shortages). And some markets will just clear, so that excess demand is zero. The auctioneer’s rule is to raise price in those markets where there is a shortage, and to cut price in markets where there is a surplus, and then announce the new price vector. To foreshadow, this is analogous to the problem that the Gausian project will have with harmonizing different norms. The fact that there are several, or many, potentially acceptable norms or publicly justified laws still requires reconciliation.

For the market process, at each stage there is the new suggestion at reconciliation, and then implementation to see if there is harmony. We observe what happens, and continue to use the “trial and error” method, raising price in whatever market has a shortage and cutting in whatever market has a surplus. Since we know (or have assumed) that the equilibrium exists, and since the auctioneer can move us toward the equilibrium, there is at least a tendency toward a steady state. There may be multiple equilibria, there may be a single equilibrium. The auctioneer’s job is to keep the process of reconciliation going until equilibrium is reached.

In summary: neo-classical economics starts with the assumption that prices, quantities, tastes, incomes, resource availability, labor effort, and technology are either known or are endogenously determined as parameters. The only exception is the selection of a vector of initial endowments for all participants. This endowment itself need not be a Pareto Optimum, because the welfare theorems indicate that the result of decentralized trading will be a Pareto Optimum. Further, given the ethically appropriate selection of the initial endowment vector, the outcome will be morally acceptable.

The ethical question presented to the society is how to choose that initial endowment. Neo-classicals generally avoid this question, precisely because it is a question of ethics. But some collective decision—made presumably behind some veil of ignorance where what is chosen is a distribution, not particular outcomes—is required to solve the problem.

The Austrian response is generally misunderstood, probably because it is mischaracterized by opponents. The objection is not that this approach is morally wrong, and that income redistribution is unethical or violates some theory of desert. Austrians might believe just that, or they might not. The real problem is that the data assumed to be given in the neo-classical formulation are not available. Starting with the assumption of single-price, arbitrage-proof equilibria in every market, with given levels of labor, capital, technology, tastes, and incomes is a very different problem from the problem that market economies are actually useful for. None of these things are known, and are not even knowable, ex ante. Markets are the means by which such information is created; competition is a discovery procedure, (following Mises, 2002). In a market setting, people make choices given their particular knowledge of local circumstances, and given their own goals.

One way of describing the problem of the neo-classical general equilibrium model, from the perspective of Austrian economics, is that it assumes, and in fact requires, far too much information about value of resources as means, and far too much agreement about the distribution of resources as ends. For an Austrian, there need be no agreement, in a market setting, about the value of a resource. If you think it’s more valuable than I do, then we agree on a price less than the maximum you are willing to pay, and more than the minimum I am willing to accept. We disagree completely on the value of the commodity; that’s the entire reason, in fact, that we are able to agree on a price. But there is nothing terribly special about that price as representing the value of the commodity, because the value of the commodity is based on the subjective assessments of market agents. The reason we can have a transaction is precisely that we disagree.

The essential problem, one that unites the market process and the public reason perspective, can be reduced (with all the dangers of reduction) to the following problem: Given two allocations of vectors of primary goods, which is better, and how would “we” know? We wouldn’t know. The problem is that answer seems to come from outside the process, and yet also be produced organically by the process. This criticism (see, for example, Fisher (1983)) is important, because it confronts an assumption—all actors are passive “price takers”—with an inconsistent conclusion—the process is dynamically convergent, with someone causing price vectors to harmonize by moving in the correct direction.

We will let x11 be the vector of m primary goods (x11 = [y111, y112, y113…y11m] received by person 1 in state of the world 1, and state of the world 2 is some other allocation of primary goods across persons, so person 1 would receive x21 in state of the world 2. State 2 need not be different for each of the n person that make up the “we,” but it must be different for at least one person for it to constitute a different “state.”

Economists generally throw up their hands at this point, because Paretian comparisons are no longer possible. What is needed is a doctrine of moral order, a consensus means of choosing among Pareto optima.

Again, to foreshadow the reason I am spending so much time on this point, “public reason” is one means by which a moral order might be derived. Public reason and neoclassical economics do not merely appeal to parallel equilibrium models of reconciling persons with different value scales, but public reason can be motivated by the failure of market processes to reach equilibrium without outside assistance in the form of the “auctioneer.” This makes it all the more important that the Gausian project goes through: Public reason is required to set the basis of moral order in order to allow us even to sensibly apply the Pareto standard in the first place.

3 The “single order of public reason” doctrine: a Kantian Parliamentarian

A society needs to choose, or maintain, a set of institutions, norms, and moral intuitions that will form the basis of our interactions with each other. These norms are the foundation of our expectations in how we will be treated and how we may treat others. Can a group of people reach a consensus in public reason, in a process analogous to (but using different institutions than) price convergence in a market? Gaus is explicit about the requirements for a “Principle of Public Justification” (p. 262). My summary here is less precise than his, but mine requires fewer definitions. A principle is publicly justified if it is agreed to by “normal moral agents.” Each normal moral agent has “sufficient reasons” to agree that the principle is universally held among all (enfranchised) moral agents, that the principle requires particular actions in particular settings, and that setting is relevant, and that other moral agents actually conform to the rule. Thus, public reason requires that we all agree, but the agreement is of a particular kind: we need not agree that one or another public reason is best, but we can require that reasons be justified, and the process of public justification of reasons requires that everyone accepts sufficient reasons as the currency of public discourse.Footnote 2 Reasons that are not sufficient, that no reasonable person could justify, are counterfeit and are not allowed as currency.

Still, there may be many reasons that are publicly justified; Gaus wants to narrow the domain until only publicly justified reasons have standing in the discussion. Thus, it might seem that the allowable moral discourse would be the intersection of all the principles held by each person with standing, which means the person is “enfranchised” as I have put it above. But this is not a voting process; the intersection of all the core values held by all people in the group is likely empty, because people disagree. What Gaus means is something broader: “my values” are not those that I think are uniquely best, but all of those values that I accept as acceptable, or allowable reasons.

Can people do that? Can they forebear dismissing reasons that are sufficient, but with which they happen to disagree? The problem, I want to argue, is analogous to the problem of existence and convergence to agreement in market settings. Given the simultaneous recognition of the situatedness of individuals and the dispersed nature of justified reasons, no one person can both advocate his or her own position and harmonize all the different positions argued by others. Just as price-takers cannot be counted on to cause prices to change in the correct direction to reconcile market processes to equilibrium without the assistance of a (mythical) auctioneer, moral agents who believe in the values and norms they use to publicly justify their reasons cannot be counted on to harmonize their disagreements without an (equally mythical) parliamentarian.Footnote 3

My argument, then, is that the process Gaus outlines requires both that the answer emerge organically from equals and yet at the same be subject to restrictions that only a “Parliamentarian” could impose. And the Parliamentarian, like the Auctioneer, does not actually exist. If this argument is correct, then Gaus has made less progress than he had hoped toward solving the problem.

3.1 The Kantian Parliamentarian

A Parliamentarian, in the real world, is an expert on universally-agreed rule of procedural by-laws and order. In the present paper, a “Parliamentarian” would be a process, a software platform, or a group of actual people who would possess, without having been in any way selected by a social choice process, the authority to identify and enforce domain restrictions on reasons that can be publicly justified. Gaus’s Kantian Parliamentarian would need to be able to limn the set of good reasons and then act as a referee—not a player, but a referee—over convergence to one, rather than another, of these good reasons for the implementation of an actual set of implied moral rules.Footnote 4 As Gaus states the problem:

Kant’s method for determining moral laws as universal laws of freedom involves an individual decision procedure: each individual is to propound universal laws. Of course, as universal laws of morality regulating the realm of ends to which all free persons are subject, these laws are to be the same for all. How are different individuals, each acting as moral sovereign, to arrive at the same set of laws? …[Kant’s answer is that we] must abstract from our differences and “private ends.” For this abstraction strategy to succeed, we must have good reasons to bracket the considerations that set us apart (our private ends), and having done this, we must still have available to us some common considerations that can serve as the basis of individual deliberations about what laws to legislate. (Gaus 2011: 37; emphasis added).

This seems like a problem of collective or social choice, threatening Arrowian indeterminacy, or worse, because the process will be subject to information problems and agenda control.Footnote 5 But Gaus argues that the process of deciding can be both decentralized and admit disagreement, and yet avoid the social choice problem. The argument proceeds (I’m simplifying) in two stepsFootnote 6:

-

(1)

Something like Rawls’s (1971) “veil of ignorance,” where people ignore information about private ends. This means that everyone either has one goal, or that differences in goals are legitimate differences about rules that are based in general, rather than particular, reasons.

-

(2)

People are assumed to have a common concern for primary goods, which provides the basis for their deliberation.

Of course, the unanimity in Rawls’s system is achieved by reducing the set of allowable reasons, and abstracting from goals. We are to consider the perspective of moral agents, and then ask what goods and rights any moral agent would need to realize their agency. The collective choice problem facing people who disagree for allowable reasons is reduced to one person, or a large army of clones, or any number in between. Since everyone’s views are identical, in Rawls’s original position, we can reduce the problem to Rousseau’s famous claim about unanimity about the general will.Footnote 7

Gaus’s alternative solution—trying to preserve what is useful about Rawls while mending its deficiencies--restores the social decision problem to its problematic status. But then the problem of social choice still has to be solved. Gaus makes very few assumptions to restrict the process of justification for public reasons, to his credit. However, my claim is that his process for reconciliation is insufficient, in the sense that more would need to be assumed. Though the agent I have called the “Kantian Parliamentarian” may not be necessary to solve the problem—dictatorship would also work!—I would argue that the Kantian Parliamentarian is the minimally restrictive condition that allows Gaus’s project to go through. The system requires an animating agent (Kant’s “learned man”) to make philosophically informed judgments about whether particular rules are allowable.

Vallier (2011) is sympathetic to what he calls “public reason liberalism,” which Gaus (2011) is advocating and extending. He gives credit to Gaus for avoiding the common standard for “reasonableness,” which he calls “accessibility.”

Accessibility: A’s reason X is accessible to the public if and only if members of the public (at the right level of idealization) can see that X is justified according to common evaluative standards. (p. 369).

Gaus is trying to avoid the requirement of accessibility, which is too restrictive. Vallier suggests that we call the weaker standard “intelligibility,” meaning more like the reason makes sense, and that a reasonable person might find it persuasive, even if the person who finds it intelligible does not.

There are several interesting parts to Vallier’s critique, but the two most important aspects for present purposes are (1) justification and (2) the “right level of idealization.” Vallier claims (p. 370) that claims are justified if they are “permissibly affirmed.” And he argues (p. 371) that conceptions of idealization in the public reason project can be thought of as possessing four dimensions: reasonableness, rationality, coherence, and information.

The reason that these two aspects of accessibility are important is that the requirements placed on the group relying on public reason are substantial. Justification requires something more than “I understand your reasons.” In fact, I have to grant that your reasons are allowable and potentially persuasive, even if it happens that I am not persuaded by them, and for reasons that are also justified. And the “right level of idealization” is important because I need to be able to take my reasons outside of the particular context and reason about general principles. Of Vallier’s four “dimensions,” reasonableness and rationality might be attributed to Kant’s “entire reading public,” because they could be individual characteristics. But coherence and information are more difficult, because they are features that individuals are not very good at judging for themselves. Coherence requires that we somehow “wipe out contradictions” (in Vallier’s terms, p. 372) in subjective beliefs and motivations, and information requires that the citizen either knows what must be known to give good reasons, or knows that she does not know.

But this is simply Hayek’s “knowledge problem,” raised in a different institutional setting. To be fair, Hayek himself argued that the knowledge problem was the reason emergent rules, which he called laws, were always superior to legislation. And he was careful to claim that people could not be counted to understand the reasons why this was true, because the value of the emergent laws and traditions is not obvious and may in fact be fully understood by anyone in its entirety. Nonetheless, the rules that emerge from Hayek’s extended social order had a character—in Hayek’s view, at least—that made such laws contain more information, be more coherent, and be better means of serving social goals than rules that were laid on or consciously formulated.Footnote 8

Gaus tries to solve the problem this way:

-

1.

Humans can be modeled as rule-following creatures. This is not an “as if” assumption, but is intended to be actually descriptive of human nature.

-

2.

The selection of rules, or the choice of one set of rules over another, must be justified. The mechanism for justification Gaus advocates is “public reason.”

-

3.

Any set of actual rules chosen by the society is binding, provided it is justified and was itself selected according to the rules for choosing rules. Public reasons, as the justificatory standard, then work as substitutes for what would be, in the Public Choice tradition, actual consent. Public reason is an account of what we have most practical reason to do; what we would agree to do is a different question. Still, if the public reason approach is to form a justification for political authority, it has to be the case that rules justified by public reason can then be enforced through coercion, as if they had been formally consented.

It that’s true, then “public reason” needs a Parliamentarian, someone who rules on whether certain amendments, bills, or arguments are “in order,” in the sense they qualify as usable, or justified, claims. Instead of enforcing Robert’s Rules, or whatever rules of procedure an assembly might normally use to guide its Parliamentarian, public reason stands in need of an authority to license proposals as justified, in the precise sense described by Vallier (2011), or “reasonable,” in the sense intended by Rawls (1971).Footnote 9 Once such judgments about admissible reasons have been registered, it is plausible for justified reasons to substitute for consent in precisely the way Gaus describes.Footnote 10 But the conditions for reaching a consensus on public reasons is no more plausible than the neo-classical claim that markets reach full and stable equilibrium. In both cases, an additional bit of organization is required, an Auctioneer for the Walrasian problem and a Parliamentarian for the Rawlsian problem.

What’s interesting is that the Hayekian criticism—that the process assumes information as an input that is actually an output, perhaps the key output, for the process—is the same in both instances. Neo-classicals take prices as given, when competition is a discovery process.Footnote 11 My central claim is that Gaus is unable (fully) to solve the analogous problem for public reason, because he wants both to have the process be emergent and yet constrained by “planned” rules agreed on (or agreeable) in advance.

Importantly, precisely the same criticism could be made, and for the same reasons, of Hayek’s optimism about “the law.” Many in the Public Choice tradition, but especially James Buchanan, felt that Hayek’s insistence on decentralized choice and emphasis on spontaneous order was simply unworkable at the level of rules. Rules, according to Buchanan, need to be chosen, which itself requires rules, or rather metarules, rather than just emerging. Buchanan was fond of quoting T.D. Weldon, from States and Morals, as saying “... government is not something which just happens. It has to be “laid on” by somebody.” (Buchanan and Tullock 1962, p. 57).

Gaus works hard to avoid the problem, and to his credit does so in just the way that Hayek proposed. But to converge on a set of rules is difficult, without social choice. Groups of people lack both information and the mechanisms for harmonizing competing desires and different considerations that are the hallmark of markets. Gaus’s project would need an additional agent, a universally trusted and endorsed mechanism for endorsing, or disallowing, reasons that are candidates for justification. For the sake of argument, I have called this mythical agent, to emphasize the parallel with the Walrasian Auctioneer, the Kantian Parliamentarian.

4 Conclusions

Gaus’s overall project is to identify possibilities for convergence on a set of shared rules endorsed by a process of public justification. I have tried to make an analogy, comparing the convergence of disagreements about prices in a general equilibrium setting, using both the neo-classical and Austrian conceptions of price adjustments. In particular, I have argued that Gaus, like the neo-classicals, needs the services of an “auctioneer,” or disinterested (and, unfortunately, nonexistent) referee whose job it is to manage and oversee the adjustment process.

Political authority, for Hayek, was based on the accumulated wisdom of tradition, norms, and deference to prices as guides to the scarcity of resources. Hayek was skeptical that any individual could possess all, or even much, of the information required to make system-level decisions. He expanded this insight from application to a market setting only to a view of tradition and “knowledge” embodied in “laws” discovered by trial and error and spread either by mimicry or other group selection processes. Hayek summarized this argument in the introduction to his book The Fatal Conceit.

[T]he extended order resulted not from human design or intention, but spontaneously; it arose from unintentionally conforming to certain traditional and largely moral practices, many of which men tend to dislike, whose significance they usually fail to understand, whose validity they cannot prove, and which have nonetheless fairly rapidly spread by means of an evolutionary selection - the comparative increase of population and wealth - of those groups that happened to follow them. The unwitting, reluctant, even painful adoption of these practices kept these groups together, increased their access to valuable information of all sorts, and enabled them to be ‘fruitful, and multiply, and replenish the earth, and subdue it’ (Genesis 1:28). This process is perhaps the least appreciated facet of human evolution. (Hayek 1988, p. 6).

The Hayekian criticism, and the larger Austrian criticism, of the general equilibrium approach is that the Walrasian Auctioneer cannot possibly have all the information necessary to solve all the disagreements over value. There will remain large numbers of “errors” to be corrected by entrepreneurship, though the tendency toward agreement, directed by profit and loss, is the key argument for the institution of markets.

But the same criticism applies, and for the same reason, to the problem of achieving agreement through public reason. I have argued that it is difficult, and perhaps impossible, to determine authoritatively when individual moral and legal conventions--not to mention political institutions, as complex wholes of these conventions--are publicly justified, in the absence of an authority that everyone accepts. An additional authoritative agent, a mythical entity that I have dubbed the Kantian Parliamentarian, would be required to make the system work, and all agents would have to consent to this stage of rule-making. In the absence of consent to an authority who can judge whether reasons can be justified because they are “accessible,” in Vallier’s sense, individuals—even members of the “reading public”—lack the information and the capacity to know the structure of their own views.

Notes

Of course, there is the purely decentralized alternative, but that leads simply to the Humean observation that many possible conventions are possible outcomes of human society and the interaction over time of individuals. Public reason, to be useful, has to be something much more than conventions justified by the “folk theorem.”

When another demands that you comply with a rule, she is demanding that you do what you have sufficient reasons to do; she is appealing to your rational nature, not demanding that you put it aside. She must be saying: “You have reasons to comply that you are ignoring. My demand is not simply a demand that you live as I see fit, but as you would see fit if you adequately employed your reason.” And she says this not just to you, but to any violator that she comes across. How can she be so confident of her judgment, instructing each of us violators to do as we have reason to do, and thus to perform the morally autonomous action, even though we disagree? (Gaus 2011, 263).

Grynaviski and Munger (2017) describe the process by which economic slavery became racial slavery in the American South, in the era around 1830. It is debatable, of course, whether one would concede that this was an instance of the use of the “public reason” approach. But Grynaviski and Munger claim that “public reason” was precisely what Southern elites saw themselves as constructing.

It is not obvious that either of my two claims is correct, of course. First, Gaus needs a Kantian Parliamentarian. Second, nothing of the sort does, or could, exist. I am confident about the first claim. The second claim is a bit like Hayek’s claim about the knowledge problem, which is that a planned system cannot possibly have enough information to be able to arrive at anything like the correct answer. But it is possible that Gaus’s approach might be saved if a set of rules could be “laid on” from outside, perhaps by a computerized expert system. Still, this would vitiate the claim that all the information for justified public reasons is contained in the system of deliberation itself.

For a recent summary of the Arrow problems of indeterminacy and information, see Munger and Munger (2014), especially chapter 7.

First (via the veil of ignorance), we abstract away “private ends” that would lead us to legislate different universal laws. One excludes “knowledge of those contingencies which set men apart.” Second, we attribute to the parties a concern with primary goods [true human needs] that provide a basis for their common deliberation….When abstracted to the common status of agents devoted to their own (unknown) evaluative standards (values, comprehensive conceptions of the good, and so on), because “everyone is rational and similarly situated, each is convinced by the same arguments.” So although the original position begins by posing a problem of collective choice, the problem is reduced to the Kantian problem of public legislation by one person. The result is a unanimous choice on a specific conception of justice. (Gaus 2011, pp. 37–8).

.as it becomes necessary to issue new [laws], the necessity is universally seen. The first man to propose them merely says what all have already felt, and there is no question of factions or intrigues or eloquence in order to secure the passage into law of what every one has already decided to do, as soon as he is sure that the rest will act with him. (Rousseau, 2003; Book IV; emphasis added)

In fairness, what I have identified as “Hayekian” was not even fully endorsed by Hayek himself. It’s worth pointing out that Hayek, (1978; pp. 15–29), expressly embraces a kind of Kantian contractualism as a standard for assessing evolved moral conventions. For more on this subject, see Sugden (1993). Thus it would be incorrect to say that Gaus’s approach is “non-Hayekian, at least in the process he envisions. The question is whether the process Gaus envisions is sufficient for his purposes.

Under these conditions, a social order that respects the freedom and equality of all must show that individuals who care deeply about their divergent conceptions of value nevertheless have strong reason to endorse and abide by shared moral rules. Now to say that they have strong reason to endorse such shared rules only when they reason on the basis of shared concerns and they are unaware of their divergent conception is not an especially compelling conclusion. [If I can agree with everyone else if I suppress what I actually care about most], the reasonable query is, “And what will be my view of these rules when I do know what I deeply care about?” (Gaus 2011, 39–40)

References

Buchanan, J., & Tullock, G. (1962). The Calculus of Consent: Logical Foundations of Constitutional Government. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Fisher, F. M. (1983). Disequilibrium foundations of equilibrium economics, econometric society monographs in pure theory. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Gaus, G. (2011). The Order of Public Reason: A Theory of Freedom and Morality in a Diverse and Bounded World. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Grynaviski, Jeffrey, and Michael Munger. (2017). Reconstructing Racism: Transforming Racial Hierarchy from “Necessary Evil” Into “Positive Good.” Social Philosophy and Policy, forthcoming.

Hayek, F. A. (1978). Law, Legislation and Liberty, Volume 2: The Mirage of Social Justice. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Hayek, F. A. (1988). The Fatal Conceit: The Errors of Socialism. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Kant, Immanuel. (1784/2010). An Answer to the Question: 'What Is Enlightenment?' H.B. Nesbitt (Translator/Editor). New York: Great Ideas Series, Penguin-Random House Publishers.

Kirzner, I. M. (1984). Economics Planning and the Knowledge Problem. Cato Journal, 4(2), 407–418.

Mises, Ludwig von. (2002). “Competition as a Discovery Procedure.” Translated by Marcellus Snowe. Quarterly Journal of Austrian Economics. 5(3): 9–23.

Munger, M., & Munger, K. (2014). Choosing in Groups. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Rawls, J. (1971). The Theory of Justice. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Rawls, J. (1997). The Idea of Public Reason Revisited. The University of Chicago Law Review, 64(3), 765–807.

Rousseau, Jean-Jacques. The Social Contract. (1762 / 2003). Translated by G. D. H. Cole. London: Dover Thrift Editions.

Sugden, R. (1993). Normative Judgments and Spontaneous Order: The Contractarian Element in Hayek's Thought. Constitutional Political Economy, 4(3), 393–424.

Vallier, K. (2011). Against Public Reason Liberalism’s Accessibility Requirement. Journal of Moral Philosophy, 8, 366–389.

Walras, Léon. (1877). Trans. 1954. Elements of Pure Economics. Translated by William Jaffe. Homewood, Ill.: Irwin (for American Econ. Assoc. and Royal Econ. Soc.).

Walras, L. (1899). Equations de la circulation. Bull. Soc. Vaudoise Sci. Naturelles, 35, 85–103.

Acknowledgments

Prepared for “Hayekian Themes on Gaus’s Order of Public Reason,” a symposium for the Review of Austrian Economics, guest-edited by Kevin Vallier. I thank, but in no way implicate, Jonathan Anomaly, Geoffrey Brennan, Peter Boettke, Michael Gillespie, and Ricardo Guzman, as well as (least implicated of all) Gerry Gaus himself. Mostly, however, I thank Kevin Vallier, who improved and focused the paper immensely, in addition to suggesting improvements in language and an embarrassing number of outright errors. The flaws in the paper are largely the result of my inability to implement all of his suggestions completely.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Munger, M.C. Human agency and convergence: Gaus’s Kantian Parliamentarian. Rev Austrian Econ 30, 353–364 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11138-016-0357-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11138-016-0357-9