Abstract

Purpose

To assess experiences of sexuality and of receiving sexual healthcare in cervical cancer (CC) survivors.

Methods

A qualitative phenomenological study using semistructured one-on-one interviews was conducted with 15 Belgian CC survivors recruited in 5 hospitals from August 2021 to February 2022. The interviews were audiotaped and transcribed verbatim. Data were analyzed using inductive thematic analysis. COREQ and SRQR reporting guidelines were applied.

Results

Most participants experienced an altered sexuality after CC treatment with often long-term loss/lack of sex drive, little/no spontaneity, limitation of positions to avoid dyspareunia, less intense orgasms, or no sexual activity at all. In some cases, emotional intimacy became more prominent. Physical (vaginal bleeding, vaginal dryness, dyspareunia, menopausal symptoms) and psychological consequences (guilt, changed self-image) were at the root of the altered sexuality. Treatment-induced menopause reduced sex drive. In premenopausal patients, treatment and/or treatment-induced menopause resulted in the sudden elimination of family planning. Most participants highlighted the need to discuss their altered sexual experience with their partner to grow together toward a new interpretation of sexuality. To facilitate this discussion, most of the participants emphasized the need for greater partner involvement by healthcare providers (HPs). The oncology nurse or sexologist was the preferred HP with whom to discuss sexual health. The preferred timing for information about the sexual consequences of treatment was at treatment completion or during early follow-up.

Conclusion

Both treatment-induced physical and psychological experiences were prominent and altered sexuality. Overall, there was a need for HPs to adopt proactive patient-tailored approaches to discuss sexual health.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

Cervical cancer (CC) is the fourth most common cancer in women worldwide, resulting in 604,121 new cases in 2020 [1]. Approximately 600 patients per year are diagnosed with CC in Belgium, with an average age of 55 years at diagnosis. Seventy-six percent of these newly diagnosed CC patients are classified as TNM stage I to III and are treated with curative intent. With a 5-year relative survival rate of 69.6%, most CC patients will live for many years [2]. Human papillomavirus (HPV) is the main cause of CC. More than 90% of women clear this sexually transmitted infection, yet a small percentage of patients with persistent chronic HPV infection ultimately develop CC after 5 to 20 years [3]. CC treatment with curative intent depends on the stage and may consist of (a combined approach of) surgery, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy [4]. Unfortunately, CC treatment comes with a cost, as increased long-term bladder, bowel, and vaginal/sexual morbidity have been reported [5]. Many CC patients are sexually active at the time of diagnosis, so sexuality and sexual health is of special concern.

Sexual health is defined by the WHO as a state of physical, emotional, mental, and social well-being in relation to sexuality; it is not merely the absence of disease, dysfunction, or infirmity. Sexual health requires a positive and respectful approach to sexuality and sexual relationships, as well as the possibility of having pleasurable and safe sexual experiences, free of coercion, discrimination, and violence. For sexual health to be attained and maintained, the sexual rights of all persons must be respected, protected, and fulfilled [6].

Sexual health and experiences of sexuality may become more important during survivorship. As a global definition of ‘the cancer survivor’ is lacking, the term often has been restricted to participants who were free of cancer after treatment completion with curative intent.

Quantitative studies of CC survivors have reported significantly less sexual interest, more sexual dysfunction, and lower sexual satisfaction compared to women without a history of CC [7,8,9]. The prevalence of sexual dysfunction in CC survivors is estimated to be between 33 and 80% [10,11,12,13]. A main predictor of sexual health is the receipt of radiotherapy [5, 7, 9, 10, 14,15,16,17,18,19,20]. Furthermore, sexual dysfunction has been shown to impact health-related quality of life (HRQoL) [16, 21, 22]. Juraskova et al. demonstrated that overall sexual function was predicted more strongly by the perceived quality than the quantity of sexual interactions in CC and endometrial cancer survivors; moreover, a small change in perceived quality had a large impact on overall sexual function [22]. Qualitative data about how CC survivors experience altered sexuality are scarce. The few available reports confirmed the presence of sexual dysfunction, which often led to sexual distress [9, 23, 24]. The obtained quantitative insights should be supplemented with qualitative findings about the experiences of potentially altered sexuality in CC survivors. These qualitative insights can inform healthcare providers (HPs) regarding barriers and needs in sexual healthcare during CC survivorship and enhance tailored interventions and recommendations for practice to address them. As standardized sexual health care for CC survivors is lacking in Belgium, each hospital depends on its own knowledge and skills to implement this in daily practice resulting in HPs to decide for themselves when, how often, to what extent, etc. to discuss sexual health.

Therefore, the present study aimed to assess CC survivors’ experiences of sexuality and (unmet) needs when receiving sexual healthcare.

Methods

Study design

A qualitative phenomenological research design using semistructured interviews was performed. The consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ) and standards for reporting qualitative research (SRQR) were applied [25, 26].

Sample and participant recruitment procedures

Adult Dutch-speaking CC survivors were eligible, regardless of sexual symptoms, if treatment with curative intent was completed more than 6 months prior, if they had follow‐up after treatment completion, and if there was no suspicion of recurrence. This implies that our definition of cancer survivor has been restricted to participants who were managed with curative intent and free of cancer after treatment completion. Participants with a recurrence of CC or with a maintenance therapy were not considered for this study as this would result in a small subset of the sample potentially impacting generalizability. Moreover, our aim was to include participants with similar mindsets, considering potential different reflections regarding sexuality in participants treated with curative versus palliative intent. Written and oral informed consent was obtained from all individual participants prior to the audio-recorded interviews.

Participants were recruited from five hospitals (1 university and 4 general hospitals) in Belgium. CC survivors were informed about this study by their attending physician and received an informative flyer with contact information. After the patient contacted the main investigator (first author, E.N.), an appointment for an individual interview was arranged. E.N. is a female PhD student working as a medical oncologist at Ghent University Hospital. The current role of the researcher was emphasized to the participants before the interview. E.N. did not have a therapeutic relationship with any of the participants. Data were anonymized for the other authors, as therapeutic relationships existed with some of the participants.

The study protocol was approved by the Ghent University Hospital Ethical Committee in Belgium (B.U.N.: B6702021000492).

Data collection and interview topics

A single individual semistructured interview with open-ended questions was conducted face to face by E.N. Data collection took place between August 2021 and February 2022, either in a private room designed for conversations about treatment at the hospital or at the participant’s home without any other persons present. All interviews were audiotaped using a voice recorder. Field notes were made during the interview. The topics that were discussed are included in the interview guide (Table 1). The interview guide was developed based on problems faced in our clinical practice. As we also aimed to potentially improve sexual healthcare delivery, the topic guide also contained questions regarding preferences besides questions related to experiences. There was no patient involvement nor framework or model at the base. However, several health care providers (gynecologist, radiation-oncologist, medical oncologists, specialized nurses) and an experienced researcher in qualitative research with nursing background took part in the development to warrant content validity of the interview guide. All were considered as (clinical) experts in the field of CC or in qualitative research. We examined the sexuality experiences of CC survivors, communication about the impact of treatment on sexual health, how sexuality relates to other long-term side effects of therapy, factors that influence sexuality and healthcare needs concerning sexual health. Demographic characteristics and treatment information were collected at the end of the interview. Pilot interviews (n = 2) were conducted to discuss the quality of the interview technique and were included in the analysis. During the interviews, member checking was performed by means of rephrasing and summarizing what participants said. Sampling took place by performing intermediate data analysis to check whether no new information was obtained, i.e., data saturation. Recurring major themes were re-questioned in subsequent interviews until no new information was reached (data saturation). Interviews lasted on average 61 min (range 43–88 min) (Table 2).

Data analysis

Data collection and analysis were performed in a cyclic and alternating process. An inductive thematic analysis was performed using the stepped approach by Giorgi [27]. First, all interviews were transcribed verbatim by a working student who signed a confidentiality declaration. Transcripts were stored on a protected server at Ghent University Hospital; audio tapes were removed after all interviews were transcribed. The transcripts were imported into NVivo R1.6 to support the analysis and were not returned to participants for comment [28]. Then, E.N. and H.V.H. read and reread the transcripts to get the total picture. Subsequently E.N. and H.V.H. independently assigned meaning units to the data and structured these units into common themes. The meaning units and themes (Fig. 1) were checked and rechecked in previous transcripts to ensure the correct translation between the meaning of a participant and the written statement and that no insights were missed. E.N. and H.V.H. met to discuss the analysis and to interpret the findings to prevent ambiguities that might detract from the trustworthiness of the findings. A third researcher, L.M. K additionally read three interviews and participated in the discussion for interpretation of the findings as a researcher triangulation strategy.

Results

Participant characteristics

Fifteen patients approached E.N. to participate, and all gave consent. Table 2 presents an overview of the patients’ characteristics and the recruitment per pseudonymized center. The median age of the participants was 48.0 years. Fourteen participants had a partner at the time of the interview, and 14 participants had been sexually active after completing CC treatment. The one participant who was not sexually active had a partner. The median interval since completion of treatment was 4.0 years. Sixty-six percent of the women were highly educated. A multimodal approach consisting of surgery, radiotherapy, and/or chemotherapy was reported in 80% of the participants. All patients were of Caucasian race, and all stated implicitly to have a heterosexual preference referring to partners as their husbands.

Overview of main findings

An overview of the themes is shown in Fig. 1.

Beliefs about sexuality

When participants were asked for how they perceived ‘sexuality’, this term was seen more broadly than expected stating it meant more to them than only intercourse (Table 3, quote 1). It entailed emotional and physical intimacy, such as foreplay, going out for a date, feeling attractive, and being attentive to each other. Having had a CC diagnosis did not change their conception of sexuality but rather how participants experienced sexuality. A more prominent place for emotional intimacy was described, often because of an altered sexuality experience. In most cases, dyspareunia led to less frequent penetration and less sexual enjoyment. Participants admitted having little interest in a new sex episode, resulting in an evolution to no penetrative sex at all in some participants over time. In some of these cases, the loss of sex with their partner was replaced with emotional connection within the relationship (quotes 2 and 3).

Sexual health experiences

The participants stated to have an altered sexuality experience. This altered experience was caused by several physical consequences of the treatment such as vaginal dryness, dyspareunia, and vaginal bleeding during intercourse (quotes 4, 5, 6, and 7). In some participants dyspareunia declined over time which enhanced sexual activity, whereas other participants reported persistence over the years which negatively impacted the penetrative part of sex. Moreover, menopause, induced by CC treatment, was retrospectively associated by the participants to loss of sex drive, bodily changes, and loss of fertility, and impacted largely long-term sexual experience (quotes 8 and 9). The need for hormone replacement to prevent worsening menopausal complaints bothered some patients as they would never take it voluntarily and the administration of the medication confronted them with the history of CC.

The altered experience of sexuality was mentioned in terms of long-term loss or lack of sex drive, little or no spontaneity, limitation of positions to avoid dyspareunia, less intense orgasms, or no sexual activity at all (quotes 10, 11 and 12). Participants stated that they feared dyspareunia and vaginal bleeding during intercourse as a reason for reduced spontaneity, whereas dyspareunia and menopause were stated to induce the loss or lack of sex drive.

The realization that CC diagnosis and treatment could impact further sexual activity differed between participants in terms of timing. For some participants, this occurred shortly after the diagnosis. This was mainly in participants who directly or indirectly mentioned having a high libido (quote 13). For other participants, sexuality became more important in the period after treatment completion. These participants stated that they mostly focused on survival during their treatment (quotes 14 and 15). To our feeling, most participants were relatively at peace with their new sexual situation. Some stated that they had no other choice than to accept the present situation although they had some frustrations about specific aspects of the altered sexuality.

Different coping strategies to overcome sexual discomfort were cited by participants. They varied from the use of lubricants prior to and during intercourse and prolonged foreplay to the prevention of long-term vaginal stenosis by the regular use of vaginal dilators. Additionally, some participants mentioned avoiding certain positions during intercourse to avoid dyspareunia (quote 6). Others stated the need for an in-depth conversation with their partner after encountering physical barriers about how they want to find their way as a sexually active couple. Moreover, participants considered it necessary to inform their new partner of (potential) vaginal bleeding prior to first intercourse.

Psychosocial consequences

The psychological impact and consequences of CC diagnosis and treatment related to sexuality mentioned by participants were rather diverse. Some of the participants directly or indirectly described feelings of fear of the new sexual situation after diagnosis. Some were afraid without giving details of what they were specifically afraid of, while others were anxious about specific experiences such as vaginal bleeding, dyspareunia, or restriction of sexual positions (quotes 16 and 17). In some participants, the diagnosis of CC was established because of vaginal bleeding. This vaginal bleeding was therefore a traumatic experience. Facing again vaginal bleeding after CC treatment threw them back to the diagnosis. Participants stated to be afraid of relapse.

A subset of participants with a desire to have children stated that the sudden loss of fertility was difficult to overcome. These participants described a mourning process and an unfulfilled long-term children’s desire (quote 18). Some of those participants admitted the need of long-term psychological assistance to learn to deal with this loss of fertility. Moreover, some participants expressed struggling with the HPV etiology of CC and referred to this as the possibility of promiscuous behavior by their (former) partner (quote 19). This induced often temporary feelings of anger given that the diagnosis of CC could possibly have been avoided. Participants stated that this knowledge about the etiology did not lead to confrontation with the (former) partner about this fact. Some of them consulted their physician or oncology nurse for an in-depth conversation. One participant stopped all sexual activity with her husband without confronting him with her motives.

Some participants expressed feelings of guilt due to their reduced sex drive and the effect on their partners who were unwillingly involved in this situation (quote 20). The unwilling involvement of the partner in the new sexual situation led to resentment and negative impact on the relationship in some participants (impossibility to find each other in the new situation) whereas other participants admitted a stronger emotional connection with their partner as a result.

Divergent results were achieved regarding the feeling of being a woman, ranging from the explicitly acknowledging feeling less feminine to participants who completely denied this feeling. Most of them assigned this less feminine feeling to being the root of a forced altered experience of sexuality within the couple, to the removal of the uterus and ovaries and to the consequences of therapy-induced menopause (quotes 21 and 22).

Communication with and support from partners

Participants expressed a variable need to discuss sexual experience and alteration of sexuality with their partner. Some participants perceived openness in communication about the new sexual situation as a bridge to relieve psychological distress, which often accompanied their sexual health issues and new sexual situation (quotes 23 and 24). However, one patient who was not sexually active after CC diagnosis stated that there was absolutely no need for her to start the discussion with her husband, and another participant mentioned that the lack of discussion with her partner about sexual issues had resulted in growing apart sexually and in emotional connection as well (quote 25).

Some participants discussed with their partners how they could adapt sexual activities to the new sexual situation as well as the usefulness of continuing sexual activity when experiencing sexual discomfort. During a discussion with their partner, it became clear that partners feared inducing pain or bleeding, which hindered participants in reinitiating sexual activity. For these participants, an open discussion was crucial given that remaining sexually active was important to them and for their relationship with their partner (quote 26).

The need for greater partner involvement by HPs was strongly emphasized by the participants as discussions about sexual consequences of CC diagnosis or treatment impact the partner as well (quote 27). However, some participants felt they could not speak freely with their HP if their partner was present (quote 28). Some participants stated, however, that partners did not share the same vision on being involved in discussions with HPs about sexual activity, as they considered these to be a women’s issue. Additionally, partners could not always be present at consultations where this topic could be discussed. This was mainly due to partners that could not easily get free time at work to attend consultations (quote 29).

Communication with healthcare providers and sexual healthcare provision

Participants expressed differences in the perceived attention by HPs to sexual consequences of the treatment prior to the treatment. Some participants stated that an HP paid attention prior to treatment, whereas others stated that there was no attention at all to this topic. This conversation took place with the oncology nurse, the gynecologist, the radiation-oncologist, and sexologist.

Most participants stated that trust in their HPs lowered the threshold to ask questions related to sexuality during follow-up. Nevertheless, they emphasized that they had to overcome a threshold to ask the question mostly driven by embarrassment about this topic (quote 30). The oncology nurse turned out to be the preferred person to address questions related to sexuality. The main reasons to prefer the oncology nurses was at first that participants desired that physicians mainly focus on the disease. Second, participants believed that physicians lacked time during consultation to talk about sexual issues. Participants also stated that they had built a trusting relationship throughout the cancer trajectory with the oncology nurse, which enhanced the discussion of the topic (quote 31).

Participants emphasized the need for proactive information and counseling by the HP about sexual consequences, the availability of specific information about these consequences, and the opportunity to meet the sexologist (quote 30). The fact that participants should not have to take the first step themselves was seen as liberating. Second, participants proposed tailored communication, i.e., the content and timing of discussion had to be tailored to patients’ wishes and needs. Third, participants emphasized the need for a safe environment and sufficient time to communicate about sexual health. They often had the impression of insufficient time during a consultation (quote 32).

The participants agreed that the HP’s attitude was the determining factor to feel safe discussing sexual health (i.e., being open, not judging).

There was unanimity between the participants that information about the sexual consequences of treatment should not be included in the discussion of diagnosis and treatment unless the treatment was only surgical. A focus on survival restricted them from listening attentively to matters of lesser importance at that time (quote 15). In the case of (chemo)radiotherapy, there was a clear preference to be informed at the end of the treatment, during the oncological rehabilitation program or at the first follow-up consultation.

Discussion

The experience of altered sexuality is one of the most difficult aspects of cancer survivorship and distinctly affects HRQoL [15, 18, 19, 29]. Striving for better patient care starts with identifying barriers in current care and subsequently finding an appropriate approach to overcome them. This qualitative study aimed to describe the psychological and behavioral experiences and preferences of sex and sexual healthcare care among CC survivors in Belgium.

Our results confirmed the presence of various physical and psychosocial obstacles that impacted the experience of sexuality. Participants mostly reported vaginal dryness and dyspareunia resulting in reduced spontaneity and limitation of positions. Moreover, dyspareunia and menopause triggered loss of sex drive. Finally, the altered sexuality experience was accompanied by guilt and fear in some participants, whereas others adjusted to the new situation. Participants sometimes mentioned a shift from sexual acts to other types of intimacy. This distinction of sexual health before and after CC could explain the altered experience of sexuality present in our results because it is a consequence of negative physical and emotional sensations as well as changed roles and intimate relationships within a couple [30, 31].

Our results are in line with a systematic review that concluded that vaginal dryness, dyspareunia, short vagina, and sexual dissatisfaction were prominent issues in CC survivors [17]. A more recent cross-sectional study of CC survivors reported that the significantly affected domains of the Female Sexual Functioning Index questionnaire were lubrication and pain [16]. A negative correlation between dyspareunia and sexual enjoyment in locally advanced CC survivors observed by Kirchheiner et al. was similarly mentioned by the participants in our qualitative study [32]. Shankar et al. reported an altered sex life in 25% of CC survivors, consisting mainly of an alteration in sexual interest [33]. However, Grion et al. reported that only one-third of women with CC prior to radiotherapy were sexually active in the previous three months. This finding was driven by disease-related factors and pointed out that sexual activity at diagnosis should not always be considered baseline sexual activity [34]. Although this finding suggests a less abrupt time demarcation for changed sexual activities than reported in our study, we did not systematically inquire about baseline sexual activity or sexual activity at diagnosis in our study participants.

Our results show that patients experience barriers in discussing psychological and sexual health complaints due to CC treatment. According to the participants in this study, HPs seemed to experience a threshold for discussing this, which is in line with prior research [35, 36]. However, intervention programs to enhance breast cancer patients’ and HPs’ sexual health communication behavior have been successfully studied [37, 38]. Communication pitfalls regarding sexual health were similarly described in our study. The most striking recommendation from the patient’s point of view was for the HP to facilitate and initiate the topic with the content and timepoint customized to the patient’s desires. Similar results were obtained by Chapman et al., who reported a suboptimal provision of tailored discussions about sexuality in patients who received radiotherapy for gynecologic cancer [39]. The timepoint to discuss the sexual consequences of therapy is crucial and is patient dependent. In our study, there was a clear preference to be informed at completion or shortly after completion of the treatment. Our results show that patients move to an overpowering survival mode shortly after diagnosis. Consequently, discussion of the topic during this period is not optimal. This was confirmed by Vermeer et al. who reported that psychosexual support was most desired between 6 and 12 months after treatment, and by Ye et al. who reported a time interval between treatment and regular sexual activity of 5 months [23, 40]. This suggested a sexual trial period during which increased awareness and proactive sexual support from the HP seems important. Our results also highlighted that specific attention should be given to the sexually transmitted etiology of the disease by framing the prevalence of HPV in the global population and reassuring patients that CC does not necessarily mean the partner has cheated. Furthermore, 2 of the 6 patients who received brachytherapy described its huge mental impact, mainly due to pain, total dependence (during the time the applicator was inserted in situ) and the emotional impact of the unnatural position. Additional focus on this therapy component was spontaneously suggested, consisting of visualization of the applicator prior to first brachytherapy and the availability of photographs illustrating the effect on the vagina. Ultimately, patients suggested motivating future CC survivors to participate in an oncological rehabilitation program since contact with fellow sufferers was a great source of support.

Our study did not show a preference regarding the sex of the person who communicated about sexuality. However, Chapman et al. reported that 62.7% of their female participants preferred to have this discussion with female providers [39].

Even though all communicative strategies contribute to greater knowledge about sexual health, we cannot avoid the fact that there are limitations to the new sexual situation inherent in diagnosis and treatment. A major stumbling block is often learning to accept this new situation. Moreover, we know that sexual satisfaction per se is not impaired when sexual dysfunction is present [8, 23]. Strikingly, a systematic review by Fugman et al. demonstrated that cancer is associated with a slightly decreased divorce rate, except for CC, which seems to be associated with an increased divorce rate [27].

The support of a psychologist and sexologist can facilitate this acceptance, although the threshold for consulting them may vary between patients. Investigating the impact of intervention by a sexologist during the aftercare process for the patient seems indispensable. Furthermore, Pizetta et al. offered in their systematic review the use of an individualized sexuality care plan by a multidisciplinary team next to the development of rehabilitation programs for sexuality complaints after gynecologic cancer [41]. Progress has been made recently to implement these measurements in daily practice. In the recently updated ESGO/ESTRO/ESP Guidelines for the management of patients with CC by Cibula et al. specific recommendations about sexual health care were formulated for the first time. These recommendations ranged from the inclusion of sexual dysfunction and menopausal symptoms as potential main side effects in patient survivorship monitoring and care plan to the incorporation of sexual rehabilitation measures after radiotherapy [42]. In the recently published ESGO/ESTRO quality indicators for radiation therapy of CC by Chargari et al. quality indicator 19 consists of ‘Patients are offered a sexual rehabilitation program’ with the target of minimum 80% to achieve [43]. However, these guidelines should still be implemented in daily practice in many hospitals treating CC.

Our study had several limitations. The most important limitation was selection bias during recruitment given the rather delicate topic; participants who were relatively at ease talking about sexuality were more likely to participate. Moreover, participants had to contact E.N. to express their interest. This barrier can negatively influence the participation of potential candidates, impacting transferability and data saturation. Second, recall bias was present because the longest interval between treatment and the interview was 13 years. Third, the number of participants was not distributed in a homogeneous way over the 5 hospitals, which may impact the transferability of certain interview themes (e.g., communication with HPs). Fourth, there was a limited heterogeneity of the participant characteristics especially regarding other sexual (LGBTQI+), cultural, religious, and ethical preferences as well as treatment with palliative intent which can impact participant’s views on sexuality, and which may influence transferability and generalizability of the findings from this study. In future research, a heterogenous sample including a diverse population should be aimed for. Fifth, data saturation was achieved for the major themes but might not be achieved on the experience of HPV as etiology of CC. However, this was not part of the topic guide and is very interesting for future research. Sixth, there was no patient involvement in the development of the interview topic guide nor transcripts were returned to patients for comments. In future research, more patient participation should be aimed for. Our study also had several key strengths, including the use of multicentered participation within Flanders, Belgium; the number of interviews, which was found to be sufficient to obtain credible impressions; and the rigorous methodology with independent coding by two researchers, which led to enhanced transferability of our findings.

Conclusion

Most of the CC survivors reported physical and/or psychological discomfort linked to diagnosis or treatment that impacted sexual activity and the experience of sexuality. This was accompanied by guilt and fear in some participants, whereas others adjusted to the new situation. In some participants, it induced a shift from (physical) sex to other types of intimacy. A common thread was the importance of a proactive patient-tailored approach from HPs regarding the negotiability, timing and content of treatment-induced sexual consequences. Extra attention should be given to the sexually transmitted etiology of the disease.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Sung, H., Ferlay, J., Siegel, R. L., Laversanne, M., Soerjomataram, I., Jemal, A., & Bray, F. (2021). Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 71(3), 209–49.

Belgian Cancer Registry 2019. https://kankerregister.org/media/docs/CancerFactSheets/2019/Cancer_Fact_Sheet_CervicalCancer_2019.pdf

World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cervical-cancer

Cibula, D., Potter, R., Planchamp, F., Avall-Lundqvist, E., Fischerova, D., Haie Meder, C., et al. (2018). The European Society of Gynaecological Oncology/European Society for Radiotherapy and Oncology/European Society of Pathology Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Cervical Cancer. International Journal of Gynecological Cancer: Official Journal of the International Gynecological Cancer Society, 28(4), 641–55.

Pieterse, Q. D., Kenter, G. G., Maas, C. P., de Kroon, C. D., Creutzberg, C. L., Trimbos, J. B., & Ter Kuile, M. M. (2013). Self-reported sexual, bowel and bladder function in cervical cancer patients following different treatment modalities: Longitudinal prospective cohort study. International Journal of Gynecological Cancer: Official Journal of the International Gynecological Cancer Society, 23(9), 1717–25.

Donovan, K. A., Taliaferro, L. A., Alvarez, E. M., Jacobsen, P. B., Roetzheim, R. G., & Wenham, R. M. (2007). Sexual health in women treated for cervical cancer: Characteristics and correlates. Gynecologic Oncology, 104(2), 428–34.

Aerts, L., Enzlin, P., Verhaeghe, J., Poppe, W., Vergote, I., & Amant, F. (2014). Long-term sexual functioning in women after surgical treatment of cervical cancer stages IA to IB: A prospective controlled study. International Journal of Gynecological Cancer: Official Journal of the International Gynecological Cancer Society, 24(8), 1527–34.

Lammerink, E. A., de Bock, G. H., Pras, E., Reyners, A. K., & Mourits, M. J. (2012). Sexual functioning of cervical cancer survivors: A review with a female perspective. Maturitas, 72(4), 296–304.

Zhou, W., Yang, X., Dai, Y., Wu, Q., He, G., & Yin, G. (2016). Survey of cervical cancer survivors regarding quality of life and sexual function. Journal of Cancer Research and Therapeutics, 12(2), 938–44.

Correa, C. S., Leite, I. C., Andrade, A. P., de Souza Sergio Ferreira, A., Carvalho, S. M., & Guerra, M. R. (2016). Sexual function of women surviving cervical cancer. Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics, 293(5), 1053–63.

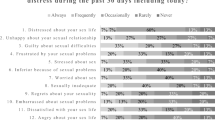

Bakker, R. M., Kenter, G. G., Creutzberg, C. L., Stiggelbout, A. M., Derks, M., Mingelen, W., et al. (2017). Sexual distress and associated factors among cervical cancer survivors: A cross-sectional multicenter observational study. Psycho-oncology, 26(10), 1470–7.

Tsai, T. Y., Chen, S. Y., Tsai, M. H., Su, Y. L., Ho, C. M., & Su, H. F. (2011). Prevalence and associated factors of sexual dysfunction in cervical cancer patients. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 8(6), 1789–96.

Harding, Y., Ooyama, T., Nakamoto, T., Wakayama, A., Kudaka, W., Inamine, M., et al. (2014). Radiotherapy- or radical surgery-induced female sexual morbidity in stages IB and II cervical cancer. International Journal of Gynecological Cancer: Official Journal of the International Gynecological Cancer Society, 24(4), 800–5.

Wu, X., Wu, L., Han, J., Wu, Y., Cao, T., Gao, Y., et al. (2021). Evaluation of the sexual quality of life and sexual function of cervical cancer survivors after cancer treatment: A retrospective trial. Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics, 304(4), 999–1006.

Correia, R. A., Bonfim, C. V. D., Feitosa, K. M. A., Furtado, B., Ferreira, D., & Santos, S. L. D. (2020). Sexual dysfunction after cervical cancer treatment. Revista da Escola de Enfermagem da USP, 54, e03636.

Ye, S., Yang, J., Cao, D., Lang, J., & Shen, K. (2014). A systematic review of quality of life and sexual function of patients with cervical cancer after treatment. International Journal of Gynecological Cancer: Official Journal of the International Gynecological Cancer Society, 24(7), 1146–57.

Pfaendler, K. S., Wenzel, L., Mechanic, M. B., & Penner, K. R. (2015). Cervical cancer survivorship: Long-term quality of life and social support. Clinical Therapeutics, 37(1), 39–48.

Sung Uk, L., Young Ae, K., Young-Ho, Y., Yeon-Joo, K., Myong Cheol, L., Sang-Yoon, P., et al. (2017). General health status of long-term cervical cancer survivors after radiotherapy. Strahlentherapie und Onkologie: Organ der Deutschen Rontgengesellschaft [et al]., 193(7), 543–51.

Tramacere, F., Lancellotta, V., Casa, C., Fionda, B., Cornacchione, P., Mazzarella, C., et al. (2022). Assessment of sexual dysfunction in cervical cancer patients after different treatment modality: A systematic review. Medicina (Kaunas, Lithuania), 58(9), 1223.

Bae, H., & Park, H. (2016). Sexual function, depression, and quality of life in patients with cervical cancer. Supportive Care in Cancer: Official Journal of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer, 24(3), 1277–83.

Juraskova, I., Bonner, C., Bell, M. L., Sharpe, L., Robertson, R., & Butow, P. (2012). Quantity vs quality: An exploration of the predictors of posttreatment sexual adjustment for women affected by early stage cervical and endometrial cancer. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 9(11), 2952–60.

Vermeer, W. M., Bakker, R. M., Kenter, G. G., Stiggelbout, A. M., & Ter Kuile, M. M. (2016). Cervical cancer survivors’ and partners’ experiences with sexual dysfunction and psychosexual support. Supportive Care in Cancer: Official Journal of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer, 24(4), 1679–87.

Roussin, M., Lowe, J., Hamilton, A., & Martin, L. (2023). Sexual quality of life in young gynaecological cancer survivors: A qualitative study. Quality of Life Research. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-023-03553-4

Tong, A., Sainsbury, P., & Craig, J. (2007). Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care: Journal of the International Society for Quality in Health Care, 19(6), 349–57.

O’Brien, B. C., Harris, I. B., Beckman, T. J., Reed, D. A., & Cook, D. A. (2014). Standards for reporting qualitative research: A synthesis of recommendations. Academic Medicine: Journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges, 89(9), 1245–51.

Giorgi, A. (1985). Phenomenology and Psychological Research. Duquesne University Press.

International Q. NVivo. Melbourne, Australia1990–2013.

Membrilla-Beltran, L., Cardona, D., Camara-Roca, L., Aparicio-Mota, A., Roman, P., & Rueda-Ruzafa, L. (2023). Impact of cervical cancer on quality of life and sexuality in female survivors. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(4), 3751.

Perz, J., Ussher, J. M., & Gilbert, E. (2014). Feeling well and talking about sex: Psycho-social predictors of sexual functioning after cancer. BMC Cancer, 14, 228.

Hawkins, Y., Ussher, J., Gilbert, E., Perz, J., Sandoval, M., & Sundquist, K. (2009). Changes in sexuality and intimacy after the diagnosis and treatment of cancer: The experience of partners in a sexual relationship with a person with cancer. Cancer Nursing, 32(4), 271–80.

Kirchheiner, K., Smet, S., Jurgenliemk-Schulz, I. M., Haie-Meder, C., Chargari, C., Lindegaard, J. C., et al. (2022). Impact of vaginal symptoms and hormonal replacement therapy on sexual outcomes after definitive chemoradiotherapy in patients with locally advanced cervical cancer: Results from the EMBRACE-I study. International Journal of Radiation Oncology, Biology, Physics, 112(2), 400–13.

Shankar, A., Patil, J., Luther, A., Mandrelle, K., Chakraborty, A., Dubey, A., et al. (2020). Sexual dysfunction in carcinoma cervix: Assessment in post treated cases by LENTSOMA Scale. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention: APJCP, 21(2), 349–54.

Grion, R. C., Baccaro, L. F., Vaz, A. F., Costa-Paiva, L., Conde, D. M., & Pinto-Neto, A. M. (2016). Sexual function and quality of life in women with cervical cancer before radiotherapy: A pilot study. Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics, 293(4), 879–86.

Sporn, N. J., Smith, K. B., Pirl, W. F., Lennes, I. T., Hyland, K. A., & Park, E. R. (2015). Sexual health communication between cancer survivors and providers: How frequently does it occur and which providers are preferred? Psycho-oncology, 24(9), 1167–73.

Ussher, J. M., Perz, J., Gilbert, E., Wong, W. K., Mason, C., Hobbs, K., & Kirsten, L. (2013). Talking about sex after cancer: A discourse analytic study of health care professional accounts of sexual communication with patients. Psychology & Health, 28(12), 1370–90.

Reese, J. B., Sorice, K. A., Pollard, W., Handorf, E., Beach, M. C., Daly, M. B., et al. (2021). Efficacy of a multimedia intervention in facilitating breast cancer patients’ clinical communication about sexual health: Results of a randomized controlled trial. Psycho-oncology, 30(5), 681–90.

Reese, J. B., Lepore, S. J., Daly, M. B., Handorf, E., Sorice, K. A., Porter, L. S., et al. (2019). A brief intervention to enhance breast cancer clinicians’ communication about sexual health: Feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary outcomes. Psycho-oncology, 28(4), 872–9.

Chapman, C. H., Heath, G., Fairchild, P., Berger, M. B., Wittmann, D., Uppal, S., et al. (2019). Gynecologic radiation oncology patients report unmet needs regarding sexual health communication with providers. Journal of Cancer Research and Clinical Oncology, 145(2), 495–502.

Ye, S., Yang, J., Cao, D., Zhu, L., Lang, J., Chuang, L. T., & Shen, K. (2014). Quality of life and sexual function of patients following radical hysterectomy and vaginal extension. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 11(5), 1334–42.

Pizetta, L. M., Reis, A. D. C., Mexas, M. P., Guimaraes, V. A., & de Paula, C. L. (2022). Management strategies for sexuality complaints after gynecologic cancer: A systematic review. Revista brasileira de ginecologia e obstetricia: revista da Federacao Brasileira das Sociedades de Ginecologia e Obstetricia, 44(10), 962–71.

Cibula, D., Rosaria Raspollini, M., Planchamp, F., Centeno, C., Chargari, C., Felix, A., et al. (2023). ESGO/ESTRO/ESP Guidelines for the management of patients with cervical cancer—Update 2023. Radiotherapy and Oncology: Journal of the European Society for Therapeutic Radiology and Oncology, 184, 109682.

Chargari, C., Tanderup, K., Planchamp, F., Chiva, L., Humphrey, P., Sturdza, A., et al. (2023). ESGO/ESTRO quality indicators for radiation therapy of cervical cancer. Radiotherapy and Oncology: Journal of the European Society for Therapeutic Radiology and Oncology, 183, 109589.

Acknowledgements

We thank all the women, their families, and their caregivers for participating in this study. E.N. is a clinical PhD Fellow of the Research Foundation-Flanders (FWO) (Grant Number: 1703020N). E.N. is supported by a grant from the Fund of Innovation and Research of Ghent University Hospital. E.A.D. is an “aspirant” (PhD Fellow) of the FWO (Grant Number: 1195919N) (https://www.fwo.be/en/).

Funding

The authors did not receive support from any organization for the submitted work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: EN, HV, PT, KV, HGD; methodology: EN, L-MK, HV, PT, KV, HGD; investigation: EN; data curation: EN, HVH, L-MK; project administration: HV, PT, KV, HGD; validation: EN, HVH, L-MK, HV, PT, KV, HGD; formal analysis: EN, HVH, L-MK; visualization: EN, HV, PT, KV, HGD; writing—original draft: EN; writing—review & editing: HVH, EADJ, MRPO, SR, RS, KJT, KW, L-MK, HV, PT, KV, HGD; supervision: HV, PT, KV, HGD.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors have no relevant financial or nonfinancial interests to disclose.

Ethical approval

Approval was obtained from the ethics committee of Ghent University Hospital, Belgium (B.U.N.: B6702021000492). The procedures used in this study adhere to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent to participate

Written informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent to publication

The authors affirm that all individual participants provided informed consent for the publication of results. No identifying information is included in this manuscript.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Naert, E., Van Hulle, H., De Jaeghere, E.A. et al. Sexual health in Belgian cervical cancer survivors: an exploratory qualitative study. Qual Life Res 33, 1401–1414 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-024-03603-5

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-024-03603-5