Abstract

Purpose

To identify HIV clinicians’ needs for the clinical use of a new patient-reported outcome measure (PRO) on barriers to antiretroviral therapy (ART) adherence.

Methods

In 2015, five focus groups with 31 clinicians from France were transcribed, coded with Atlas.ti, and submitted to a typological analysis.

Results

The analysis identified seven patient profiles, each tied to distinct barriers to adherence and to specific needs for the PRO’s content, data collection and transmission. Clinicians preferred, for the patient who is: (1) ‘passive,’ that the PRO collect information on ART knowledge, to ensure that the prescription’s instructions are being respected; (2) ‘misleading,’ that it be able to detect adherence to ART and socially desirable responses; (3) ‘stoic,’ that questions challenge the patient to recognize treatment-specific side effects; (4) ‘hedonistic,’ that the PRO contains content on lifestyle and risk-taking; (5) ‘obsessive,’ that the PRO captures quality of life and stressful life events; (6) ‘overburdened,’ that the PRO provides information on the person’s home environment, socioeconomic status and cultural constraints. For all or most patient profiles, the clinicians wished that the PRO be completed, minimally, prior to the medical consultation and to receive alerts, under varying conditions, when problematic scores were detected. Depending on the profile, there was preference for the inclusion of open-ended questions and transmission of cross-sectional, periodic or longitudinal PRO data.

Conclusion

Overall, this study’s findings suggest that to support the clinical management of ART adherence, our PRO must meet the needs of a wide variety of patients and must perform multiple functions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

For people living with HIV, daily adherence to antiretroviral therapy (ART) is crucial to therapeutic success [1, 2]. Barriers to adherence are numerous and can change over time [3, 4]. These include side effects, HIV stigma [5], and a poor patient–provider relationship [6]. The use of a patient-reported outcome measure (PRO) in HIV clinical practice centering on patients’ perceived barriers to ART adherence may improve the quality of care and adherence management. It could improve the knowledge base of HIV impacts and treatment effects for clinical decision-making and enhance the detection of patients’ challenges with ART adherence [7], thus helping to foster adherence, health and quality of life [8]. Surprisingly, few validated HIV-specific PROs comprehensively examine barriers to ART adherence [9]. Our study, conducted in Canada and France, is devoted to the development and implementation of such a PRO (the I-Score Study, clinicaltrials.gov identifier: NCT02586584). However, ensuring that the PRO is relevant to both patients and HIV clinicians was deemed necessary. PRO development research in HIV has more commonly integrated the perspective of patients relative to that of clinicians, while the role of patients is often passive, confined to that of study participant or respondent [10] and vulnerable patient populations are rarely included [11]. Nevertheless, attending to the needs of clinicians, key players in the implementation of PRO use in healthcare settings, may help ensure its success and sustainability [12].

Several studies highlight that clinicians may be reluctant to integrate the use of PROs in their clinical practice [13]. Among the main challenges are a lack of resources and time for administering the PRO, difficulties receiving PRO data, [14] and doubts about the relevance of the information collected for orienting practice or treatment [15]. Conversely, some have advanced that positive attitudes towards PRO use may increase when clinicians are consulted on practical considerations (e.g., collection and analysis of PRO data, PRO administration), methodology (e.g., data interpretation and transmission) and applications for patient care (e.g., patient education, shared decision-making, screening and monitoring of health and therapeutic problems) [16].

For these reasons, we conducted a needs assessment among HIV-specialized clinicians. Our early analyses established that they agreed on the general features of the PRO to be developed. They mentioned needing a PRO that can: (1) provide information that they have difficulty accessing during consultations; (2) adapt to individual patients’ abilities; (3) guide decision-making and save time; and (4) help to personalize follow-up [17]. They also viewed the PRO as having the potential to encourage patients to become active participants in their own health and to contribute to more individualized, comprehensive and patient-centered care [18].

In addition, it became apparent that the clinicians’ specific needs for the PRO were interpreted through seven implicit profiles of patients with adherence challenges [19]. These profiles were detailed in a prior publication, highlighting their potential role in ART adherence management [19]. In summary, they are the patients who is: (1) ‘passive,’ whose lack of initiative may limit comprehension of their doctor’s adherence instructions; (2) ‘misleading,’ who says what the clinician wants to hear, mentioning no adherence barriers; (3) ‘stoic,’ who requests the most potent ART available and may minimize side effects; (4) ‘hedonistic,’ who gives priority to their personal life and pleasurable pursuits over care and ART; (5) ‘obsessive,’ who has an irrational fear of ART failure and cannot discern their ‘true’ adherence barriers; (6) ‘overburdened,’ who faces life priorities that take precedence over ART and; (7) ‘underprivileged,’ who has limited education, income and housing, compromising access to care and ART. In this article, we describe how the profiles informed clinicians’ specific needs for the new PRO in terms of content, data collection, transmission and administration.

Methods

Design, setting and study context

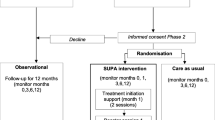

For this qualitative needs assessment [20], five focus groups were conducted with HIV clinicians across France. Their purpose was, in part, to ensure the relevance of the PRO to clinicians in France, to understand what they wanted from it, and to better ascertain the context of its eventual use. A needs assessment among Canadian HIV clinicians is underway. Focus groups were chosen as they are a recognized method for gathering opinions, expectations and needs of people on health topics [21] and for generating new and unexpected ideas [22]. Note that the PRO’s content is expected to be based primarily on a conceptual framework derived from a synthesis of qualitative studies with people living with HIV on ART adherence barriers in developed countries [23].

Recruitment and sampling

The principal investigator of the I-Score Study, BL, recruited participants via an electronic personal invitation that explained that the PRO, as conceived, is intended to measure factors perceived by HIV-infected persons to impede proper adherence (not adherence itself). It also included a description of the needs assessment’s objectives and details on the focus group (i.e. date, location, duration, interview schedule). Informed consent was obtained and no direct compensation was provided to participants.

The focus groups were carried out from February to September 2015, with the size of focus groups ranging from five to nine participants. All participants needed to be fluent in French and to have at least a year’s experience practicing HIV care. Purposive sampling guaranteed consideration of different clinical practice experiences [24]. Three focus groups were conducted at HIV clinics in Paris, Tours, and Clermont-Ferrand. These cities differed widely in both physician density and clinic caseload size and composition, representing diverse medical contexts in France. Two other focus groups were held in Paris and Nancy, organized by BL during an event that assembled HIV clinicians from across France. For all focus groups, a meal was provided by our pharmaceutical partner.

Data collection and analysis

BL led hour-long focus groups using a semi-structured interview schedule [25]. Before proceeding, he explained that the focus groups were part of the groundwork for designing the PRO and planning its implementation. Questions addressed clinicians’ needs regarding: (1) the PRO’s content; (2) how best to collect and transmit PRO data; and; (3) the logistics of the tool’s administration. Limited sociodemographic and clinical practice information was collected from participants with a short survey. Digital audio recordings of the focus groups were transcribed verbatim and reviewed and analyzed by IT. Analysis proceeded first with thematic analysis [26] and the coding with Atlas.ti version 7.0 of all content with themes derived closely from the interview schedule. Codes were clarified and refined by IT and DL [27]. Heterogeneity in the codes’ content suggested another pattern of organization around patient characteristics. Hence, typological analysis [28] was used, constituting a series of patient profiles with distinct barriers to adherence. As mentioned, these not only proved useful for explaining clinicians’ ART adherence management practices [19] but also their preferences for the PRO, as will be presented here. These analyses were revised by KE, DL, and BL. The labels attached to the profiles were either taken from participants’ own terms (e.g., ‘passive,’ ‘obsessive,’ ‘underprivileged’) or chosen by our team (i.e., ‘misleading,’ ‘stoic,’ ‘hedonistic,’ ‘overburdened’). The latter, nevertheless, translate summarily and faithfully the clusters of patient characteristics described by the clinicians.

Results

Study participants

The sample (n = 31) is described in Table 1. Most clinicians were hospital-based (71%), almost as many had a decade or more experience treating patients with HIV/AIDS (68%) and routine HIV care occupied 50% of their clinical activities. Almost half were infectious disease specialists (48%) and 42% were women. The largest HIV patient population that they served was men who have sex with men (40%), followed by women (35%), people from an HIV-endemic country (30%), and immigrants (30%).

HIV clinicians’ needs for the PRO in relation to the patient profiles

The clinicians’ needs for the PRO per patient profile are described below. Illustrative focus group excerpts are presented in Table 2. These were translated from French to English by a bilingual co-investigator (KE).

The ‘passive’ patient

For the clinicians, the adherence of this type of patient is vulnerable to a lack of initiative and a potentially incomplete understanding of the doctor’s instructions. Therefore, to them, the PRO must essentially collect information on ART knowledge, to make sure that the prescription’s instructions are being respected and, if necessary, to reorient the patient appropriately. Closed questions that are easy to understand and visual aids (e.g., for ART recognition) must be favored to make PRO completion and content simple and to facilitate accurate self-reporting of their adherence barriers. These patients should complete the PRO before each medical consultation to monitor and maintain their understanding of ART. PRO data collection and analysis will provide the clinician with immediate alerts of specific changes in routine which may impact how passive patients understand and adhere to their treatment.

The ‘misleading’ patient

For this type of patient, the PRO must be able to detect adherence to ART (not merely adherence barriers) and socially desirable responses to questions. The use of indirect questions on the same topics, using different wording, is deemed essential to detect responses aimed at pleasing the clinician. Given that suboptimal clinical outcomes are perceived as common with this patient profile, clinicians believed combining both open and closed questions could help to better understand the circumstances underlying ART failure. To them, a more frequent administration (e.g., weekly) of the PRO should also be considered, with periodic analysis providing the basis for alerts sent to the clinician on any changes in daily life that may affect adherence. This would allow clinicians to schedule preventive medical appointments with the aim of averting ART failure, which would improve patient care between regularly scheduled visits. In addition, clinicians preferred that the PRO be administered before each routine medical consultation, the results of which should be accompanied by biomarker test results (e.g., CD4 cell count, viral load). This would help clinicians to understand any occurrence of therapeutic failure.

The ‘stoic’ patient

For this type of patient who essentially ‘tolerates the intolerable,’ clinicians highlight that the PRO must target problems experienced with their ART, given that adherence here may be compromised by side effects or a poorly adapted treatment. Closed questions are suggested to challenge the patient to recognize treatment-specific side effects, exploring a variety of possible adverse reactions. This is important as this patient type is presented as demanding the most potent ART available, possibly to the detriment of their physical and emotional health. In addition, open questions are proposed to capture details and subtleties related to the patient’s personal experiences with ART and adverse reactions. With this, clinicians hope to assess whether their ART is sufficiently adapted or if it generates excessive side effects that could impact adherence. Minimally, clinicians wish that the PRO be completed before each visit to evaluate if the treatment needs to be changed. More frequent PRO administration, as requested by the clinician (e.g., monthly), is also suggested to provide a more complete picture of the patient’s experience with their ART. A longitudinal analysis of scores is deemed necessary to provide information about side effects that persist, increase or decrease over time, and may affect this patient’s adherence. In addition, alerts must be sent to the clinician, according to the perceived or actual severity of side effects.

The ‘hedonistic’ patient

For the clinicians, with this type of patient, the PRO must contain questions on lifestyle issues (e.g., partying) and risk-taking (e.g., recreational drug use, unprotected sex), as these factors may interfere with their adherence. As these patients are deemed pleasure-oriented, to encourage completion, the PRO must have a stimulating graphic user interface, such as a video game, to create an engaging, interactive and entertaining experience. Furthermore, to ensure that the patient is motivated to accurately complete the questionnaire, it is proposed that the PRO be administered at a moment chosen by the patient. Clinicians also believed that a report on patient answers, including a summary of recreational and sexual activities, should be transmitted to both patient and clinician. This was perceived as facilitating discussion about the patient’s issues, including their life priorities and concerns for care, and as possibly increasing patient satisfaction and involvement in care. Clinicians wanted alerts to be sent to both clinician and patient, using a colored chart (i.e., low, moderate, high), when one or more problematic scores suggest that the patient’s adherence could be compromised, putting their own health and that of their sexual partners at risk. The colored chart was seen as an effective way of guiding clinical intervention and of communicating with the patient and increasing their awareness of relevant issues.

The ‘obsessive’ patient

For the clinicians, the PRO must capture quality of life and stressful life events with this type of patient. As the patient’s health-related worries are pervasive and can dominate patient–clinician discussions, genuine barriers to adherence may not receive sufficient attention. Clinicians wished most questions to be close-ended, providing a range of possible answers to help the patient report significant adherence barriers. For assessing both quality of life and stressful events, they wanted some open questions with space provided for a textual response, which would allow the patient to clarify their answers to the close-ended questions. Clinicians wanted access to the patient’s current and previous scores for each dimension to facilitate their assessment of the patient’s adherence challenges. Textual clarifications were deemed useful for understanding the nature of any barrier and how it may impact ART adherence. With this patient, clinicians preferred that the PRO be administered sparingly (e.g., monthly) to avoid overwhelming the clinician with PRO data and to prevent the patient from becoming anxious should there be a lack of feedback from the clinician. Collection of patient scores over time were presented as useful, however, clinicians believed it necessary to determine, for each obsessive patient, what difference in consecutive scores merits an alert to the clinician.

The ‘overburdened’ patient

For this type of patient, perceived to juggle many life priorities, clinicians ask that the PRO provides information on the person’s family/domestic environment, socioeconomic status and cultural constraints (e.g., HIV stigmatization) that may conflict with adequately taking ART. They prefer that the PRO be administered before the consultation to ensure that it is filled out completely and properly; its completion at home could be compromised by the patient’s fear of disclosing their HIV status or other responsibilities (e.g., work, childcare). Short closed questions, using a Likert scale to capture agreement or disagreement, were proposed to allow the overburdened patient to adequately respond to as many questions as possible within a short period of time. To the clinicians, longitudinal analysis of the PRO’s data is required because the barriers most often encountered by the patient are likely to be an integral part of their daily life. Alerts, sent to the clinician based on repeated episodes of adherence-threatening conflicts between life priorities, were deemed essential.

The ‘underprivileged’ patient

As this type of patient is understood to face multiple vulnerabilities, clinicians considered that the PRO must collect data on material circumstances (e.g., housing) and socio-economic situation (e.g., education, income, employment). In addition, to accommodate a language barrier or lack of literacy, they preferred that the PRO be administered before the consultation, under the supervision of medical staff to offer assistance, when necessary. They wanted closed questions to be constructed with basic vocabulary to ensure that they are easily understood. Similarly, answer options with emoticons were offered as potentially better translating what the patient wishes to communicate to their doctor. Given purported vulnerability to loss to care due to life circumstances, clinicians doubted the accessibility of longitudinal PRO data on all such patients. Nevertheless, cross-sectional data and analysis were seen as helping to detect the patient’s socio-economic instability which may otherwise have gone unnoticed. Alerts sent to the clinician were wanted, depending on the severity of the problem and its potential impact on adherence.

Discussion

Since HIV is considered a chronic condition, the scientific literature has increasingly emphasized strategies to improve HIV-infected patients’ well-being, quality of life, health, and adaptation to HIV treatment [7, 29, 30]. Early identification of potential adherence problems can help, in part, to achieve these goals [31]. The DHHS treatment guidelines [31] recommend that clinicians identify patients with ART adherence problems and provide them with adherence support. However, little is known about what they may deem helpful in this regard [32]. We addressed this gap with our project to develop a PRO for HIV clinical care focused on barriers to ART adherence. We identified clinicians’ preferences for the PRO’s content, data collection, transmission, and administration, as filtered through the perceived needs of seven patient profiles.

These patient profiles may be perceived as judgmental or questionable. However, other research has shown HIV health providers to “classify” patients into profiles [33]. In addition, studies on ART adherence suggest that clinicians draw on characteristics of the individual patient (e.g., sex, race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, risk group, chronic illness diagnoses) in treatment-related decision-making (e.g., ART prescription) [34, 35], despite there being mixed results regarding their statistical association with adherence [34, 36,37,38]. Patient profiles, as conceived by clinicians, should be addressed. These profiles can be viewed as heuristics [39], in the complex decision-making involved in clinical care [39]. Still, clinicians must recognize that implicit biases towards patients may influence their clinical and treatment decisions, in part, by affecting patient/clinician communication [40]. Indeed, studies on biases and stigma in care show that misconceptions about patients can reduce patient-centered care in quality and quantity [41, 42]. Furthermore, patients’ view of, and compliance with, clinicians’ recommendations may be affected if they perceive that they have been attributed a stigmatized identity. Along these lines, some of the approaches suggested by clinicians to manage adherence may not be optimal. For example, given the ‘misleading’ patient’s concerns with social desirability, increased surveillance to improve their adherence may cause stress and guilt, if the patient concludes that the clinician does not trust them [43, 44]. Hence, clinicians’ preferences for the PRO will need to be weighed against other considerations, including feedback received from our patient advisory committee [17] and affiliated experts in information technology development.

Some clinicians’ suggestions for the PRO converged or diverged with the research team’s initial vision for the measure. Clinicians, like the research team, preferred a multidimensional PRO. While the concept targeted for the PRO by the team was HIV-specific [39] -patient-identified ART adherence barriers (e.g., characteristics of the ART regimen [23])—some clinicians suggested the use of generic measures (e.g., quality of life, substance use, sexual practices, socioeconomic characteristics, stressful events). These are not direct measures of barriers, may be less likely to capture concerns specific to the patient population [45], and may pose challenges for guiding ART adherence barrier management and related clinical intervention [40]. However, the possibility of capturing information to generate a more general patient profile to accompany the PRO’s results will need to be considered.

We initially planned to include mainly close-ended questions. Closed questions are easier and quicker to complete, response rates are often higher than with open questions and they can be used to perform statistical analyses [46]. Clinicians preferred them exclusively for three patient profiles, but suggested a mix of closed and open questions for three others. Open questions can capture patients’ logic and frames of reference for adherence barriers, which could help clinicians to customize care. Using both question types may allow clinicians to compare quantitative and qualitative data and offer a more complete understanding of patient-relevant adherence barriers [47]. However, interpreting the answers to open questions may be time-consuming and compromise the use of the PRO in clinical practice.

We did not expect the finding that clinicians wanted alert when patients, regardless of their profile, had problematic PRO scores. An electronic PRO offers the opportunity to customize the type and intensity of alert one wants to receive, but alert management in clinical practice raises ethical and logistical considerations. In current HIV care, clinicians lack time and this could prevent them from answering PRO alerts in a timely manner, as observed in clinical trials [48]. Our team recognizes their potential to provide tailored individual care [49], according to the type and severity of adherence barrier faced by the patient. Yet this implies providing appropriate management instructions for clinicians on the assessment and follow-up of adherence barriers [49].

Both our team and clinicians prefer a self- and electronically-administered PRO, to be filled out minimally before each consultation (five patient profiles). For certain patients, clinicians considered using a more adapted completion schedule (e.g., before each medical visit and weekly, as required by the clinician, when the patient wants, monthly). Self-administered PROs can be easily implemented, but might not work for all patients (e.g., those with low literacy) [50, 51] as mentioned by the clinicians. They require that health providers have adequate training to do a summary assessment of the patient’s capacity to complete the questionnaire without being judgmental or stigmatizing [52]. With adapted schedules that include PRO completion outside of the clinic, a disadvantage is that staff assistance is not available. Thus, clinicians will need to assess both if patients find the schedule acceptable and if they are able to complete the PRO alone [53]. While frequent administration could provide a better picture of adherence barriers, this suggests that a short and non-burdensome PRO is required. In addition, depending on how scores (and alerts) are managed, more frequent data capture may require more clinic staff resources [52].

To improve the clinical management of adherence, the clinicians wanted the PRO to perform several functions: screen for previously undetected problems, monitor how treatments are working for patients, and favor more patient-centered care [15, 54]. The clinicians wanted a screening tool [54] providing cross-sectional scores (i.e. scores at a specific point in time’) [15], for example, to identify unnoticed adherence barriers related to socio-economic conditions (‘underprivileged’ patient). Periodic analyses of scores (e.g., score differences between two periods) were also requested notably to guide the clinician’s assessment of adherence barriers related to quality of life and stressful life events (‘obsessive’ patient) or changes in daily life (‘misleading’ patient). In addition, clinicians wanted a monitoring tool to longitudinally survey patients over time [52, 54], in part, to provide information about the evolution from baseline of personal skills (‘passive’ patient), life priorities (‘overburdened’ patient) or side effects (‘stoic’ patient), and to help assess whether the ART regimen is well adapted to the patient. Finally, they emphasized patient-centered care [54] by, for instance, proposing that data on recreational and sexual activities (‘hedonistic’ patient) be forwarded in summary form to both the clinician and patient, to facilitate communication between them and increase patient responsibility for their care and health.

Overall, this study’s findings suggest that to support the clinical management of ART adherence, our PRO must meet the needs of a wide variety of patients and must perform multiple functions. Our decision to develop an electronic PRO on smart devices and emerging information technology offers possibilities for accommodating this diversity, allowing flexibility and customizability in terms of data collection and analysis [55, 56]. This study’s limitations include its small purposive sample which limits the applicability of our results to other contexts in France, including rural health care centers. Data saturation was nevertheless achieved, suggestive of the transferability of these results, as no new data sufficiently stood out to justify additional focus groups [57].

Conclusion

Engaging clinicians in the I-Score Study through this needs assessment, not only provided important clinician feedback on the potential design of the PRO, it generated important contextual insight on HIV clinicians’ approach to ART adherence management. This underscores the value of clinician engagement in projects aiming to develop and implement new health technologies.

References

Ammassari, A., Trotta, M. P., Shalev, N., Marconi, P., & Antinori, A. (2012). Beyond virological suppression: The role of adherence in the late HAART era. Antiviral Therapy, 17(5), 785–792. doi:10.3851/IMP2084.

Lima, V. D., Harrigan, R., Bangsberg, D. R., Hogg, R. S., Gross, R., Yip, B., et al. (2009). The combined effect of modern highly active antiretroviral therapy regimens and adherence on mortality over time. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 50(5), 529–536. doi:10.1097/QAI.0b013e31819675e9.

Laws, M., Beach, M. C., & Lee, Y. (2012). Provider-patient adherence dialogue in HIV care: results of a multisite study. AIDS and Behavior, 17(1), 148–159.

Robert, K. (2000). Physician beliefs about antiretroviral adherence communication. AIDS Patient Care and STDs, 14(9), 477–484.

Katz, I. T., Ryu, A. E., Onuegbu, A. G., Psaros, C., Weiser, S. D., Bangsberg, D. R., et al. (2013). Impact of HIV-related stigma on treatment adherence: Systematic review and meta-synthesis. Journal of the International AIDS Society, 16(3 Suppl 2), 18640. doi:10.7448/IAS.16.3.18640.

Bolsewicz, K., Debattista, J., Vallely, A., Whittaker, A., & Fitzgerald, L. (2015). Factors associated with antiretroviral treatment uptake and adherence: a review. Perspectives from Australia, Canada, and the United Kingdom. AIDS Care, 27(12), 1429–1438. doi:10.1080/09540121.2015.1114992.

Kozak, M. S., Mugavero, M. J., Ye, J., Aban, I., Lawrence, S. T., Nevin, C. R., et al. (2012). Patient reported outcomes in routine care: advancing data capture for HIV cohort research. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 54(1), 141–147. doi:10.1093/cid/cir727.

Simpson, K. N., Hanson, K. A., Harding, G., Haider, S., Tawadrous, M., Khachatryan, A., et al. (2013). Patient reported outcome instruments used in clinical trials of HIV-infected adults on NNRTI-based therapy: a 10-year review. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 11, 164. doi:10.1186/1477-7525-11-164.

Engler, K., Lessard, D., & Lebouche, B. (2017). A review of HIV-specific patient-reported outcome measures. Patient, 10(2), 187–202. doi:10.1007/s40271-016-0195-7.

de Wit, M. P., Kvien, T. K., & Gossec, L. (2015). Patient participation as an integral part of patient-reported outcomes development ensures the representation of the patient voice: a case study from the field of rheumatology. RMD Open, 1(1), e000129. doi:10.1136/rmdopen-2015-000129.

Hagell, P., Reimer, J., & Nyberg, P. (2009). Whose quality of life? Ethical implications in patient-reported health outcome measurement. Value in Health, 12(4), 613–617. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4733.2008.00488.x.

Kwan, B. M., Sills, M. R., Graham, D., Hamer, M. K., Fairclough, D. L., Hammermeister, K. E., et al. (2016). Stakeholder engagement in a patient-reported outcomes (pro) measure implementation: A report from the SAFTINet practice-based research network (PBRN). Journal of The American Board of Family Medicine, 29(1), 102–115. doi:10.3122/jabfm.2016.01.150141.

Valderas, J. M., Kotzeva, A., Espallargues, M., Guyatt, G., Ferrans, C. E., Halyard, M. Y., et al. (2008). The impact of measuring patient-reported outcomes in clinical practice: a systematic review of the literature. Quality of Life Research : An International Journal of Quality of Life Aspects of Treatment, Care And Rehabilitation, 17(2), 179–193.

Batty, M. J., Moldavsky, M., Foroushani, P. S., Pass, S., Marriott, M., Sayal, K., et al. (2013). Implementing routine outcome measures in child and adolescent mental health services: from present to future practice. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 18(2), 82–87.

Greenhalgh, J. (2009). The applications of PROs in clinical practice: what are they, do they work, and why? Quality of Life Research, 18(1), 115–123. doi:10.1007/s11136-008-9430-6.

Boyce, M. B., Browne, J. P., & Greenhalgh, J. (2014). The experiences of professionals with using information from patient-reported outcome measures to improve the quality of healthcare: a systematic review of qualitative research. BMJ Quality & Safety, 23, 508–518.

Engler, K., Lessard, D., Toupin, I., Lènàrt, A., & Lebouché, B. (2017). Engaging stakeholders into an electronic patient-reported outcome development study: on making an HIV-specific e-PRO patient-centered. Health Policy and Technology, 6(1), 59–66.

Toupin, I., Engler, K., Lessard, D., Wong, L., Lènàrt, A., Raffi, F., et al. (2016). Developing a patient reported outcome measure (PRO) for HIV care on perceived barriers to antiretroviral adherence: Assessing the needs of HIV clinicians through typological analysis. Paper presented at the Poster presented at HIV Drug Therapy, Glasgow.

Toupin, I., Engler, K., Lessard, D., Wong, L., Lènàrt, A., Raffi, F., et al. (2017). Patient profiles as organizing HIV clinicians’ ART adherence management: a qualitative analysis. AIDS Care. doi:10.1080/09540121.2017.1360995.

Van der Maren, J. M. (2006). Méthodes de recherche pour l’éducation (2ed.). Montreal: Presses de l’Université de Montréal et de Boeck.

Marchand, J., & Giroux, C. (2010). L’utilisation des groupes de discussion en marketing commercial et social. Recheches Qualitatives, 29(1), 99–109.

Kitzinger, J. (1995). Qualitative research. Introducing focus groups. BMJ (Clinical Research ed.), 311(7000), 299–302.

Engler, K., Lènàrt, A., Lessard, D., Toupin, I., & Lebouché, B. (2017). A synthesis of qualitative research with adults living with HIV on barriers to ART adherence (Abstract #118). Paper presented at the 12th International Conference on HIV Treatment and Prevention Adherence, Miami, USA, June 4–6.

Poupart, J. (1997). L’entretien de type qualitatif: considérations épistémologiques, théoriques et méthodologiques. In J. Poupart, L.-H. Deslauriers, J.-P. Groulx, A. Laperrière, R. Mayer & A. P. Pires (Eds.), La recherche qualitative. Enjeux épistémologiques et méthodologiques. Montréal: Gaëtan Morin.

Baribeau, C. (2009). Analyse des données des entretiens de groupe. Recheches Qualitatives, 28(1), 133–148.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101.

Charmaz, K. (2000). Grounded theory: Objectivist and constructivist methods. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (2 ed., pp. 509–535). Californie: Sage Publications.

Schnapper, D. (2005). La compréhension sociologique. Démarche de l’analyse typologique. Paris: Presses de l’Université de France.

Harding, R., Liu, L., Catalan, J., & Sherr, L. (2011). What is the evidence for effectiveness of interventions to enhance coping among people living with HIV disease? A systematic review. Psychology Health and Medicine, 16(5), 564–587.

Mulkins, A. L., Ibanez-Carrasco, F., Boyack, D., & Verhoef, M. J. (2014). The Living Well Lab: A community-based HIV/AIDS research initiative. Journal of Complementary and Integrative Medicine, 11(3), 213–222. doi:10.1515/jcim-2013-0057.

Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents (2016). Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in HIV-1-infected adults and adolescents. In Health & Human Services (Eds.), (pp. 1–139).

Mosack, K. E., & Wendorf, A. R. (2011). Health care provider perspectives on informal supporters’ involvement in HIV care. Qualitative Health Research, 21(11), 1554–1566. doi:10.1177/1049732311413783.

Orchard, T., Salters, K., Palmer, A., Michelow, W., Lepik, K. J., & Hogg, R. (2015). Vets, denialists and rememberers: Social typologies of patient adherence and non-adherence to HAART from the perspective of HIV care providers. AIDS Care, 27(6), 758–761. doi:10.1080/09540121.2015.1005003.

Bogart, L. M., Catz, S. L., Kelly, J. A., & Benotsch, E. G. (2001). Factors influencing physicians’ judgments of adherence and treatment decisions for patients with HIV disease. Medical Decision Making: An International Journal of the Society for Medical Decision Making, 21(1), 28–36.

Phillips, L. A., Leventhal, E. A., & Leventhal, H. (2011). Factors associated with the accuracy of physicians’ predictions of patient adherence. Patient Education and Counseling, 85(3), 461–467. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2011.03.012.

Chesney, M. A. (2000). Factors affecting adherence to antiretroviral therapy. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 30 (Suppl 2), 171–176. doi:10.1086/313849.

Langebeek, N., Gisolf, E. H., Reiss, P., Vervoort, S. C., Hafsteinsdottir, T. B., Richter, C., et al. (2014). Predictors and correlates of adherence to combination antiretroviral therapy (ART) for chronic HIV infection: a meta-analysis. BMC Medicine, 12, 142. doi:10.1186/PREACCEPT-1453408941291432.

O’Connor, J. L., Gardner, E. M., Mannheimer, S. B., Lifson, A. R., Esser, S., Telzak, E. E., et al. (2013). Factors associated with adherence amongst 5295 people receiving antiretroviral therapy as part of an international trial. Journal of Infectious Diseases, 208(1), 40–49. doi:10.1093/infdis/jis731.

Marewski, J. N., & Gigerenzer, G. (2012). Heuristic decision making in medicine. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 14(1), 77–89.

Blair, I. V., Steiner, J. F., & Havranek, E. P. (2011). Unconscious (implicit) bias and health disparities: Where do we go from here? The Permanente Journal, 15(2), 71–78.

Jacoby, A. (1994). Felt versus enacted stigma: a concept revisited. evidence from a study of people with epilepsy in remission. Social Science & Medicine, 38(2), 269–274.

Phelan, S. M., Burgess, D. J., Yeazel, M. W., Hellerstedt, W. L., Griffin, J. M., & van Ryn, M. (2015). Impact of weight bias and stigma on quality of care and outcomes for patients with obesity. Obesity Reviews : An Official Journal of The International Association for the Study of Obesity International Association for the Study of Obesity, 16(4), 319–326. doi:10.1111/obr.12266.

Barfod, T. S., Hecht, F. M., Rubow, C., & Gerstoft, J. (2006). Physicians communication with patients about adherence to HIV medication in San Francisco and Copenhagen: a qualitative study using Grounded Theory. BMC Health Services Research, 6, 154. doi:10.1186/1472-6963-6-154.

Poppa, A., Davidson, O., Deutsch, J., Godfrey, D., Fisher, M., Head, S., et al. (2004). British HIV Association (BHIVA)/British Association for Sexual Health and HIV (BASHH) guidelines on provision of adherence support to individuals receiving antiretroviral therapy (2003). HIV Medicine, 5(Suppl 2), 46–60. doi:10.1111/j.1468-1293.2004.00215.x.

McKenna, S. P. (2011). Measuring patient-reported outcomes: Moving beyond misplaced common sense to hard science. BMC Medicine, 9, 86. doi:10.1186/1741-7015-9-86.

Meadows, K. A. (2003). So you want to do research? 5: Questionnaire design. British Journal of Community Nursing, 8(12), 562–570. doi:10.12968/bjcn.2003.8.12.11854.

Lagu, T., Goff, S. L., Hannon, N. S., Shatz, A., & Lindenauer, P. K. (2013). A mixed-methods analysis of patient reviews of hospital care in England: implications for public reporting of health care quality data in the United States. The Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety, 39(1), 7–15.

Kyte, D., Ives, J., Draper, H., & Calvert, M. (2016). Management of patient-reported outcome (PRO) alerts in clinical trials: A cross sectional survey. PLoS ONE, 11(1), e0144658. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0144658.

Kyte, D., Draper, H., & Calvert, M. (2013). Patient-reported outcome alerts: Ethical and logistical considerations in clinical trials. JAMA: The Journal of The American Medical Association, 310(12), 1229–1230. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.277222.

Fowler, F. J. (1996). Jr. Data collection methods. In B. Spilker (Ed.), Quality of Life and Pharmacoeconomics in Clinical Trials (2 ed.). Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven.

Naughton, M. J., Shumaker, S. A., Anderson, R. T., & Czajkowski, S. M. (1996). Psychological aspects of health-related quality of life measurement: tests and scales. In B. Spilker (Ed.), Quality of life and pharmacoeconomics in clinical trials (2 ed.). Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven.

Van Vliet, L. M., Harding, R., Bausewein, C., Payne, S., Higginson, I. J., & EUROIMPACT (2015). How should we manage information needs, family anxiety, depression and breathlessness for those affected by advanced disease: development of a clinical decision support tool using a Delphi design. BMC Medicine, 13, 263. doi:10.1186/s12916-015-0449-6.

Snyder, C. F., Jensen, R., Courtin, S. O., & Wu, A. W. & Website for Outpatient, Q. O. L. A. R. N. (2009). Patient viewpoint: a website for patient-reported outcomes assessment. Quality of Life Research, 18(7), 793–800. doi:10.1007/s11136-009-9497-8.

Aaronson, N. K., Elliott, T. E., Greenhalgh, J., Halyard, M. Y., Hess, R., Miller, D. M., et al. (2015) User’s guide to implementing patient-reported outcomes assessment in clinical practice. International Society for Quality of Life Research, Version.

Fredericksen, R. J., Tufano, J., Ralston, J., McReynolds, J., Stewart, M., Lober, W. B., et al. (2016). Provider perceptions of the value of same-day, electronic patient-reported measures for use in clinical HIV care. AIDS Care, 28(11), 1428–1433. doi:10.1080/09540121.2016.1189501.

Segal, C., Holve, E., & Sabharwal, R. (2013). Collecting and using patient-reported outcomes (pro) for comparative effectiveness research (CER) and patient-centered outcomes research (pcor): Challenges and opportunities. Issue Briefs and Reports. Paper 10.

Pourtois, J. & Desmet, H. (1997). Épistemologie et instumentation en sciences humaines (2nd ed.). Sprimont: Margada Editeur.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the participants of this study for their valuable input. We also thank Chantal Burelle for her administrative support and Roy Nitulescu for his feedback on the manuscript’s results.

Funding

IT, DL and AL are the recipients of a Mitacs Accelerate Postdoctoral Internship award (#05857). BL is supported by a Research Scholar award of the FRQS (Quebec Health Research Funds) and holds a Strategy for Patient-Oriented Research (SPOR) Mentorship Chair in Innovative Clinical Trials awarded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (http://www.cihr-irsc.gc.ca; CIHR: #383427). This study was conducted as a part of a larger study (The I-Score Study, clinicaltrials.gov identifier: NCT02586584) which is supported in part by both the CIHR’s HIV Clinical Trials Network (CTN 283) and by a research Grant from the Investigator Initiated Studies Program of Merck Canada Inc. (IISP-53538).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Disclosure

The opinions expressed in this manuscript are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of Merck Canada Inc. or its affiliates or related companies.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was granted by the Biomedical Research Ethics Board of the McGill University Health Centre (Study Code 14-229-PSY).

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Toupin, I., Engler, K., Lessard, D. et al. Developing a patient-reported outcome measure for HIV care on perceived barriers to antiretroviral adherence: assessing the needs of HIV clinicians through qualitative analysis. Qual Life Res 27, 379–388 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-017-1711-5

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-017-1711-5