Abstract

Purpose

Generic preference-based quality of life (PbQoL) measures are sometimes criticized for being insensitive or failing to capture important aspects of quality of life (QoL) in specific populations. The objective of this study was to systematically review and assess the construct validity and responsiveness of PbQoL measures in Parkinson’s.

Methods

Ten databases were systematically searched up to July 2015. Studies were included if a PbQoL instrument along with a common Parkinson’s clinical or QoL measure was used, and the utility values were reported. The PbQoL instruments were assessed for construct validity (discriminant and convergent validity) and responsiveness.

Results

Twenty-three of 2758 studies were included, of which the majority evidence was for EQ-5D. Overall good evidence of discriminant validity was demonstrated in the Health Utility Index (HUI)-3, EQ-5D-5L, EQ-5D-3L, 15D, HUI-2, and Disability and Distress Index (DDI). Nevertheless, HUI-2 and EQ-5D-3L were shown to be less sensitive among patients with mild Parkinson’s. Moderate to strong correlations were shown between the PbQoL measures (EQ-5D-3L, EQ-5D-5L, 15D, DDI, and HUI-II) and Parkinson’s-specific measures. Twelve studies provided evidence for the assessment of responsiveness of EQ-5D-3L and one study for 15D, among which six studies reached inconsistent results between EQ-5D-3L and the Parkinson’s-specific measures in measuring the change overtime.

Conclusions

The construct validity of the PbQoL measures was generally good, but there are concerns regarding their responsiveness to change. In Parkinson’s, the inclusion of a Parkinson’s-specific QoL measure or a generic but broader scoped mental and well-being focused measure to incorporate aspects not included in the common PbQoL measures is recommended.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Health state utilities or preference-based quality of life (PbQoL) values are an important parameter in economic evaluations due to their role in the calculation of quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) for economic evaluations. Typically, incremental QALYs are combined with incremental costs to calculate the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) in cost–utility analysis (CUA) [1]. CUA is the preferred form of economic evaluation of government advisory bodies such as the UK’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) for priority setting across disease areas [2].

To generate QALYs, PbQoL measures are needed. PbQoL measures often comprise a descriptive system (i.e., attributes (or dimensions) and levels) and a value set. The value set typically reflects the preferences of a representative population sample for each of the health states defined by the profile of attributes and levels. These values are commonly elicited using methods such as the standard gamble (SG) [3, 4] and time trade-off (TTO) [5]. PbQoL measures typically contain generic attributes, thus facilitating comparative analysis across health areas to assist priority setting. Widely used examples of generic measures include the EuroQoL EQ-5D (EQ-5D 3L and 5L versions) [6, 7], Short-Form 6 Dimension (SF-6D) [8], and Health Utilities Index (HUI) [9, 10]. The EQ-5D is recommended by UK’s NICE to be used in the reference case of economic evaluations [11].

However, the validity of applying such generic measures in some specific populations is the subject of some debate. Generic measures have sometimes been found to be less sensitive to detect changes in quality of life (QoL) in specific populations, for example mental health [12], schizophrenia [13], cancer [14], Alzheimer’s disease [15], and dementia [16]. One suggestion is that the generic attributes making up these measures may not be sufficiently relevant to the specific populations [17]. Longworth et al. [18] valued three condition-specific ‘bolt-on’ attributes as extensions to the EQ-5D related to hearing, tiredness, and vision, and found that the ‘bolt-on’ attributes had a significant impact on the values of the health states. Another reason posited for the limitation of the generic measures is that the values attached to the health states are generated from the general public (as recommended by NICE) rather than the specific population in the health states. It is argued that the general public does not have the same experience of the disease as patients and thus cannot reveal the true preference of the specific population being evaluated [19]. A further cited limitation is the discrepancies in utility values when measured with different preference-based instruments [20–24]. Richardson et al. [25] compared the utilities in patients from seven disease areas and compared them with values from healthy members from the public using six instruments, including the EQ-5D, SF-6D, HUI3, 15D, Quality of Well-Being, and Assessment of Quality of Life (AQoL). The results revealed that the magnitude of utility difference varied with the choice of instrument by more than 50% for every disease group. Such evidence raises concerns about the external comparability of the values generated by different measures and their ability to reflect true QoL in patients affected by certain conditions.

In comparison with generic QoL measures, condition-specific QoL measures are designed to be more sensitive in their ability to capture the impact of specific diseases or conditions on QoL of the population being affected. However, the QoL scores generated from such condition-specific measures are, by definition, restricted to the specific condition-specific profile of attributes and levels and as such cannot be compared meaningfully with scores obtained from other condition-specific QoL measures. Furthermore, those condition-specific QoL measures are typically not valued, i.e., not preference-based, and hence their use is restricted to ‘within-disease’ priority setting, i.e., cost-effectiveness analysis rather than broader priority setting frameworks such as CUA and cost-benefit analysis (CBA). The summary scores from condition-specific measures are typically unweighted aggregates (additive summation of scores to responses) rather than incorporating preference weights to responses. For example, in Parkinson’s, the Parkinson’s Disease Questionnaire-39-item (PDQ-39) is a common condition-specific non-preference-based QoL questionnaire for use in people with Parkinson’s (PwP). Its summary index (PDQ-39-SI) is calculated by averaging the eight attribute scores [26, 27]. Despite accurately measuring the key condition attributes in PwP, this instrument cannot be used in CUA due to the lack of valuation of attributes. Without such ‘valuation’ or ‘inclusion of preferences’ for the health states, no information on how much society would be willing to pay for improvements in scores is obtained. In recent years, research has begun to bridge the condition-specific measures/attributes with valuations, examples of which include condition-specific preference-based measures (CS-PBM) [28] and adding condition-specific ‘bolt-on’ attributes to EQ-5D [18]. Despite issues around comparability across disease areas [29], such research is an attempt to complement the limitations of current methods.

Parkinson’s is the second most common neurodegenerative disorder in elderly people, after Alzheimer’s disease [30]. QoL in PwP is affected by motor and non-motor symptoms, as well as medication side effects [31–37]. Utility values in PwP were shown to be the lowest among 29 chronic conditions being evaluated [38]. To our knowledge, there are three published reviews of QoL measures in Parkinson’s [39–41]. Martinez-Martin et al. [39] assessed and classified the generic and specific health-related QoL scales by psychometric quality to three groups, ‘recommended,’ ‘suggested,’ or ‘listed.’ Soh et al. [40] grouped the commonly used health-related QoL measures into ‘health utility,’ ‘health status,’ and ‘well-being’ and overviewed the use of these measures. Dodel et al. [41] discussed several approaches in economic evaluations in Parkinson’s including the utility instrument. In this study, EQ-5D, SF-6D, 15D, and HUI were assessed according to six criteria of psychometric properties, based on which the authors recommended the use of EQ-5D and HUI to generate utilities along with SG and TTO. However, these studies are not scoped exceptionally for PbQoL, and details were not provided for the assessment of psychometric properties due to the limited space given to PbQoL. Providing these details will benefit the interpretation of the recommendations considering that the process for the assessment of psychometric properties is context-sensitive in that the choice of external criteria may have substantial impact on the judgment of the properties.

The objective of this systematic review was to identify, summarize, and assess the psychometric properties including construct validity and responsiveness of PbQoL measures in PwP.

Methods

Search strategy

Electronic databases were searched to identify studies which measured preferences in PwP. The databases included PubMed, MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, PsycINFO, Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts (ASSIA), Social service abstracts (CSA), AgeInfo, Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE), and NHS EED database. The initial search was conducted in November 2013 and updated in July 2015. A search strategy was developed together with an expert information scientist to maximize the chance of retrieving potential relevant studies (Appendix in ESM).

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

Studies were included if the utility value for people with Parkinson’s (PwP) was measured using a PbQoL instrument and sufficient data were provided to allow the assessment of construct validity and responsiveness. Studies that were eligible for the assessment of convergent validity and responsiveness must also contain a reference measure. The reference measure could be another PbQoL measure, non-preference-based QoL measure, or commonly used clinical measures in Parkinson’s. There are two commonly used clinical measures of Parkinson’s, Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS) and Hoehn and Yahr scale (H&Y). The UPDRS assesses clinical status of Parkinson’s in four domains including, mood and cognition, activities of daily living, motor symptoms severity, and complications of treatment [42]. The H&Y describes the progression of motor function in Parkinson’s population, ranging from stage I (mildest) to stage V (most severe) [43].

For the assessment of discriminant validity, at least two groups had to be available, divided based on clinical characteristics related to Parkinson’s. PbQoL measure index scores had to be available for those groups. For the assessment of convergent validity, correlation coefficients should be reported between the PbQoL measure and the reference measure. For the assessment of responsiveness, at least two measurements or difference over a period of time (e.g., baseline and primary end point) of both PbQoL measure and the reference measure should be reported. Given this, studies were therefore excluded if the population being measured were patients without a confirmed diagnosis of Parkinson’s; the utilities of PwP were not measured, measured but not reported, not appropriately presented (e.g., EQ-5D index value not on a −0.59–1 scale), or not adequately presented for the assessment purpose, and a full result published later covering the shorter term result in previous papers.

Data extraction

After screening (YX), included studies were reviewed and the following study characteristics were extracted (YX): first author and publication year, country, study type, number of participants, clinical characteristics, and length of follow-up (when applicable). Moreover, for the purpose of assessing psychometric properties, study objectives, methods, the measures used, and their scores were also extracted.

Assessment of construct validity and responsiveness

Construct validity and responsiveness of the PbQoL approaches used in the included studies were assessed (YX) with methods used in previous studies [18]. Construct validity represents the ability that an instrument measures the construct it is intended to measure [44, 45]. Construct validity is typically assessed by examining both discriminant validity and convergent validity [18, 45–49]. Discriminant validity is the extent to which a measure can discriminate across groups that are theoretically known to differ [45, 50]. This method is also known as the ‘known group method’ [50]. In this review, we examined to what extent the utility values distinguished between patients with different clinical characteristics of Parkinson’s, with the premise that the QoL of the patients were expected to differ according to these characteristics. Good evidence of discriminant validity deemed to be demonstrated by a statistically significant difference (e.g., t test). Given that statistical significance is dependent on sample size, appropriate differences with near significance were also considered as weaker evidence for discriminant validity. Convergent validation is another test of construct validity which is defined as the extent to which one measure correlates with another measure of the same or similar construct [45, 49–51]. In this research, convergent validity is deemed to be demonstrated if the test measure is highly correlated (correlation coefficient (r) ≥ 0.5) with a measure of similar concept. A very high correlation (r > 0.7) is not expected in this research due to the inherent difference between the different types of QoL measures. Of the studies that used two or more QoL approaches, we examined the correlation between the approaches; this included both PbQoL and non-preference-based QoL measures. In this assessment, correlations above 0.5 were considered as strong, between 0.3 and 0.5 as moderate, and below 0.3 as weak. Responsiveness is the capacity of an instrument to accurately detect a change when it has occurred over a longitudinal time period [52, 53]. We examined the extent to which PbQoL measures were able to detect changes in health states overtime as measured by clinical measures or Parkinson’s-specific QoL measures. The change could be due to the health intervention or natural progression of Parkinson’s. As with discriminant validity, good evidence of responsiveness is demonstrated with shown or nearly shown statistically significant difference between the baseline and longest follow-up time point.

Results

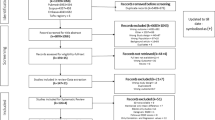

A total of 2758 records were retrieved after removing duplicates. Titles and abstracts were screened to identify relevant studies, and 2536 records were excluded based on eligibility criteria. Full text of the remaining 222 studies was further screened from which 23 studies were included in this review. A flowchart of the screening process is shown in Fig. 1.

Included studies were classified into two groups based on their study type for our assessment: Group A: cross-sectional studies [54–63] (including two case–control studies [59, 63]) for assessing discriminant and convergent validity (n = 10, Tables 1, 2); Group B: longitudinal studies [64–76] for assessing responsiveness (n = 13, Table 3).

Among the included studies, one study specifically targeted people with early Parkinson’s [69], three targeted advanced Parkinson’s [70, 73, 76], and the remaining studies recruited PwP with a wide range of severity levels. Five studies explored the relationship between QoL and specific symptoms of Parkinson’s, including apathy [54], depression [56, 62], life stress [56], the presence of dyskinesia [57], the presence of ‘wearing off’ period of drugs [57], and sweating dysfunction [63]. Among the longitudinal studies, there were seven RCTs [64, 66, 67, 69, 70, 73, 75], five prospective self-comparison study [65, 68, 71, 74], and one cohort study [72]. Three studies conducted CUA [69, 70, 76], and one study conducted cost–consequence analysis [75]. Two studies measured patients’ natural progression over a period [68, 71]. Eleven studies conducted various interventions, including drugs [65, 69, 70, 73], provision of community-based nurse specialists [66], provision of instructions of clinical guidelines to neurologists [67], standardized pharmaceutical care [72], adherent therapy [64], deep brain stimulation (DBS) surgery [76], and multidisciplinary rehabilitation [74].

Among the PbQoL measures, the EQ-5D was predominantly used, reported in 20 studies [41, 54, 55, 57, 60–69, 71–76], while the HUI-3 was reported in two studies [56, 59], HUI-2 in one [62], 15D in two [55, 70], and the Disability and Distress Index (DDI) (often referred to as the Rosser Index) in one [62]. The DDI, developed by Rosser and colleagues in 1970s, is comprised of eight levels of disability (loss of function and mobility) and four levels of subjective distress, describing 29 disability/distress states [77, 78]. One single index score is available for each state, which is generated through valuation process using ranking and relative magnitude of severity exercise [79]. The 15D is a less commonly used instrument developed in Finland [80]. It was chosen in the Norwegian and Swedish studies due to its wider spectrum aspects of QoL, higher sensitivity with five levels on each attribute, and availability of value sets in the specific country where the study was conducted [81, 82]. Among the reference measures for the assessment of psychometric properties, the PDQ-39 was the most widely used Parkinson’s-specific QoL measure, reported in 9 studies [62–64, 66, 67, 70, 71, 75, 76], followed by the short version of the PDQ-39, the PDQ-8 in 6 studies [55, 57, 58, 61, 68, 72], the Parkinson’s Disease Quality of Life Scale (PDQUALIF) was used in one study [69], the Parkinson’s disease quality of life questionnaire (PDQL) [71] in one, and the generic QoL instrument, and the SF-36 in one [75]. The measures used in each of the included studies are presented in Table 4. The characteristics of the QoL measures in the included studies are summarized in Table 5. For transparency, we presented the evidence used for the assessment of discriminant validity in Table 1, convergent validity in Table 2, and responsiveness in Table 3, along with the study characteristics.

Assessment of construct validity and responsiveness

Assessment of discriminant validity

Four studies provided adequate evidence for the assessment of the discriminant validity of the EQ-5D-3L [54, 57, 62, 63], two studies for the HUI-3 [56, 59], one study for the EQ-5D-5L and 15D [55], and one study for the DDI and HUI-II [62]. For the EQ-5D-3L, groups were defined by the presence of apathy (‘with’ or ‘without’) [54], the presence of dyskinesia (‘with’ or ‘without’) [57], the presence of ‘wearing off’ period (‘with’ or ‘without’) [57], and a case–control design (‘PwP with sweating disturbances,’ or ‘healthy controls’) [63]. EQ-5D-3L index scores achieved statistically significant differences between the above-defined groups. One remaining study by Siderowf et al. [62] assessed the ability of EQ-5D-3L, DDI, and HUI-2 to discriminate between clinically different groups as defined by a list of criteria. It was found that all of the three measures could differentiate between groups with upper (severe) and lower (mild) halves of UPDRS score (p < 0.001) and between first (mildest) and fourth (most severe) quartiles (p < 0.001); however, no difference was found in the EQ-5D-3L and HUI-2 between groups with first and second quartiles of UPDRS scores (p = 0.88, p = 0.85, respectively) while a statistically significant difference was shown in the DDI (p = 0.03). All three measures were found to be sensitive to symptoms including falling, freezing, visual hallucinations and depression with a statistically significant unadjusted mean difference between groups divided based on these symptoms (p < 0.05). However, no difference was found between groups stratified by dyskinesia or fluctuations for all the three measures, and HUI-2 failed to show difference between groups with and without swallowing difficulty (p = 0.20) [62].

For the HUI-3, one case–control study identified a statistically significant difference between PwP and general population, with the HUI-3 score being 0.56 (95% CI 0.48, 0.63) and 0.87 (95% CI 0.87, 0.88), respectively [59]. Another study reported a statistically significant and clinically important difference in HUI-3 values between the groups with and without depression after adjusting for several confounders such as age, sex, and duration of Parkinson’s [56]. This study also evaluated the impact of life stress on HUI-3 utility values and identified statistically significant adjusted mean difference between not at all/not very stressful and quite a bit/extremely stressful (adjusted mean difference 0.19 (p < 0.05)), but no difference found between a bit stressful and quite a bit/extremely stressful groups (0.14, p < 0.05) [56].

One study reported EQ-5D-5L and 15D values for groups with varied severity of Parkinson’s stratified with H&Y stages, and both instruments showed a statistically significant difference between the groups [55].

Assessment of convergent validity

Six studies presented correlation coefficients between a PbQoL measure and a reference measure for the assessment of convergent validity [55, 57, 58, 60–62]. The EQ-5D-3L score showed strong correlation (r = −0.75) with the PDQ-8 summary score [57], moderate to strong correlation with H&Y staging (r = −0.32 [57], r = −0.53 [58]), and moderate to strong correlation with the UPDRS total score (absolute r ranging from 0.39 [57] to 0.72 [58, 61]).

Two studies compared multiple PbQoL measures in terms of their correlations with Parkinson’s-specific QoL measures, and the results were mixed [55, 62]. Garcia-Gordillo et al. [55] found that the utility score from the 15D had a stronger correlation than the EQ-5D-5L with PDQ-8 summary score, with coefficients being −0.710 and −0.679, respectively. The authors explained that this could be due to the broad attributes of 15D such as leisure activities, housework, communication, worries about the future, which are likely to be substantially affected by Parkinson’s [55]. Siderowf et al. [62] compared DDI, EQ-5D-3L, and HUI-II and found that the utility score from EQ-5D-3L correlated strongly with PDQ-39 while DDI showed the weakest correlation. Specifically, they found that the EQ-5D-3L correlated strongly with ADL attribute (r = −0.69) and weakest with social support (r = −0.27), HUI-II correlated strongly with mobility (r = −0.62) and weakest with stigma (r = −0.12), and DDI correlated strongly with mobility and ADL (r = −0.42 for both) and weakest with stigma (r = 0.067) [62].

Assessment of responsiveness

Thirteen studies provided adequate information to allow an assessment of responsiveness of the PbQoL measures, including 12 studies for the EQ-5D-3L [64–69, 71–76] and one study for the 15D [70]. The one 15D study by Nyholm et al. [70] demonstrated improved QoL in the duodenal levodopa infusion arm compared to conventional oral polypharmacy arm on both PDQ-39 and 15D (both p < 0.01). Six studies showed consistency between the EQ-5D-3L and the reference measures in terms of the evidence for whether there was a statistically significant change overtime; the reference measures included UPDRS part II ADL [65], PDQ-39 [66, 67, 76], PDQ-8 and H&Y [68], and HAD depression [74].

The agreement between the EQ-5D and reference measures in the remaining six studies was concerned with various degrees [64, 69, 71–73, 75]. Daley et al. [64] reported statistically significant better QoL as shown on PDQ-39 summary score, mobility, ADL, emotional well-being, cognition, communication, and bodily discomfort after adherence therapy as compared to routine care in a RCT, but the change in EQ-5D-3L was small and not statistically significant (mean difference 0.07, 95%CI −0.1, 0.2). Similarly, Schroder et al. [72] detected an improvement (p = 0.034) in PDQ-8 score in the group with standardized community pharmaceutical care for eight months and deterioration (p = 0.019) in the group with usual care, but the statistically significant difference was not shown in EQ-5D-3L score for either groups. Stocchi et al. [73] compared adjunctive ropinirole prolonged release and immediate release in a RCT and reported an improved UPDRS total motor score (p = 0.022), but a non-significant improved UPDRS ADL score (p = 0.270) and EQ-5D-3L score (p = 0.165). Reuther et al. [71] evaluated the change in QoL and clinical measures over one year among 145 PwP and found that clinical scores deteriorated (H&Y, p = 0.000, and UPDRS, p = 0.019); however, the scores of PDQ-39 and PDQL improved (PDQ-39, p = 0.000, and PDQL, PDQL, p = 0.030), and there was no difference in the EQ-5D (p = 0.488). In contrast, two studies showed statistically significant change overtime in the EQ-5D but not in the reference measures [69, 75]. Noyes et al. [69] compared pramipexole and levodopa in a RCT over four years and did not detect a difference in PDQUALIF, but EQ-5D showed a difference between the arms from year 2 to 3 (0.048, p = 0.03) and 3 to 4 (0.071, p = 0.04). Wade et al. [75] compared multidisciplinary rehabilitation program versus usual care, in which statistically significant difference was shown between the arms in the SF-36 physical score and EQ-5D score, while no difference found for PDQ-39 and SF-36 mental score.

Discussion

This study systematically reviewed and assessed the psychometric properties of PbQoL measures in PwP. The EQ-5D-3L was found to be predominantly used as the PbQoL measure in Parkinson’s while the PDQ-39 was the most widely used Parkinson’s specific QoL measure among included studies. EQ-5D-3L has achieved statistically significant difference between the known groups divided based on clinical characteristics in most studies, but it may have limited sensitivity to detect differences in QoL among patients with mild Parkinson’s as evidenced by the subgroup analysis in the included studies [62]. Good evidence of discriminant validity has also been demonstrated in the HUI-3, EQ-5D-5L, 15D, HUI-2, and DDI despite limited evidence being available to allow the assessment. HUI-2 may be less sensitive among patients with mild Parkinson’s as it cannot differentiate between patients with first and second quartile UPDRS scores [62]. In terms of convergent validity, overall moderate to strong correlations were shown between the PbQoL measures (EQ-5D-3L, EQ-5D-5L, 15D, DDI, and HUI-II) and Parkinson’s specific QoL measures/clinical measures. It was found that the EQ-5D-3L, DDI, and HUI-II all correlated strongest with the physical attributes (i.e., mobility and ADL) of PDQ-39 and weakest with mental and well-being attributes (i.e., social support and stigma). For responsiveness, most evidence was found for the EQ-5D-3L. The agreement between EQ-5D-3L and the Parkinson’s-specific QoL/clinical measures varied across studies. Half of the studies showed that EQ-5D-3L scores reflected changes in clinical status overtime as shown on the reference measures, while the other half failed to reach consistent conclusions between the measures.

There is evidence from this review that the generic PbQoL measures correlate more strongly with the physical attributes than mental/well-being attributes of PDQ-39. Parkinson’s is a chronic, progressive condition which has been shown to affect mental/well-being aspects of QoL and as such it is important to include appropriate valuations for improvements in such attributes within priority setting decisions. The importance of these mental/well-being aspects is demonstrated by consistent presence of such attributes within Parkinson’s-specific QoL measures and by previous literature examining the effect of the mental and well-being aspects on PwP’s QoL [33, 83]. With approximately half of the domains in PDQ-39/PDQ-8, PDQUALIF, and PDQL relating to aspects other than physical health, such domains, e.g., social communication, stigma/self-image, emotional functioning, cognition, and outlook, are highly likely to have a substantial impact on PwP’s QoL. A recent systematic review found that depression was the most frequently identified determinant of health-related QoL in PwP among all the demographic and clinical factors [84]. Therefore, sufficient incorporation of valuations for these broader attributes is crucial when measuring PbQoL in Parkinson’s. The utilities from the PbQoL measures generally discriminated well between groups and correlated well with Parkinson’s clinical and QoL measures. However, the inconsistency in findings of responsiveness between those measures cautioned that the change shown on clinical measures may not necessarily lead to the same change in QoL scores. Reuther et al. [71] assumed that there might be other undetected factors leading to the opposite change in QoL scores to the clinical measures. One reason might be the fact that clinical measures such as H&Y and UPDRS focus mostly on the physical symptoms of Parkinson’s while QoL measures are subjective to individuals and based on overall experience of health and well-being. This may also help explain our finding that the PbQoL measures that focused on physical health should be theoretically able to discriminate between groups defined by clinical factors. Besides this, as clinical status or objective health status is usually one of the primary predictors of QoL, it is reasonable to expect that PbQoL measures would display discriminant and convergent validity.

Responsiveness of PbQoL measures is crucial to economic evaluations. In a bid to measure resource use and QALYs, economic evaluations often need to be carried out longitudinally over an appropriate and meaningful time horizon depending upon the intervention being assessed. Previous studies have suggested that the results of economic evaluations are sensitive to the change in utility values when chronic conditions or long-term sequelae are involved [85]; Parkinson’s is one of those conditions. Therefore, lack of definite evidence of responsiveness may critically undermine the results of CUA analysis in Parkinson’s and thus decision making as QALY gains may differ depending on the derivation of utility values. To overcome the limited responsiveness of generic PbQoL measures in certain populations, CS-PBM has been developed in recent years, e.g., in patients with asthma [86] and urinary incontinence [87]. Researchers were concerned that CS-PBM would lose the ability of comparability across disease areas, sometimes insensitive in measuring the side effects which have differed symptoms from the condition, and lack of comprehensiveness in people with comorbidities due to the narrow scope [29, 88]. However, the development of CS-PBM is argued to be valuable as it enriches the database of utilities measured by different approaches in a disease area where it exists limitations with current methods [29] and may provide valuable supplements to existing generic measures [88].

There are a number of limitations of this research. Previous studies have argued that given that no gold standard has been established for measuring PbQoL, the test of validity can only provide a reference of a measure’s performance rather than leading to a rigorous conclusion [46]. Our study assumed that the PDQ-39 or other Parkinson’s-specific measures was a ‘benchmark’ since those measures were designed specifically for Parkinson’s and hence they should be the most relevant measures to Parkinson’s. Another related limitation of the assessment methods relates to the test of convergent validity. Correlating the PbQoL against another non-preference QoL measure is arguably not the best test of convergent validity since the former is a weighted/valued measure while the latter is not. Despite this, as both instruments were designed to measure QoL, the trend of the scores (i.e., higher value represents better QoL) should be similar and therefore the validity of the test should still provide useful information. The third limitation is that floor and ceiling effects were not assessed in this study. It was found that the EQ-5D and HUI-2 have limited ability to discriminate between patients with varied levels of mild Parkinson’s. This may be related to the ceiling effect of the EQ-5D and HUI-2 as found in other studies [24, 89–91]. This ceiling effect, if present, will affect the discriminant validity and responsiveness of the PbQoL measure so that it cannot discriminate between people who all produce 1 (full health) but have different QoL in real life. Similarly, the indicator for convergent validity, the correlation coefficient will become lower if there are ceiling effects, because when the reference score is higher, the PbQoL would not change along since it is capped at 1. This effect however may not have large impact in a Parkinson’s population in general. This is because the QoL for this population is usually at low middle to upper middle range as shown in the included studies, and thus it is not likely to have large proportion of responses of full health. A final note is that the ‘minimal clinically important difference’ (MCID) was not specified in the criteria for responsiveness due to the lack of information regarding how much MCID could be in the Parkinson’s population for the PbQoL measures. There is one published study assessing MCID for PDQ-39 and suggested that the MCID differs across dimensions [92]. One conference abstract estimated MCID for EQ-5D based on the PDQ-39 scores and the UPDRS to be 0.11 (range: 0.08–0.14) and 0.10 (range: 0.04–0.17), respectively [93]. As no other information was found regarding the MCID for PbQoL in Parkinson’s, MCID was not used in our assessment criteria. Nevertheless, our criteria were not rigid on ‘statistically significant difference’ considering the sample size issue and thus ‘nearly significance’ was also accepted.

Conclusion

The construct validity of the PbQoL measures identified in this review was generally good, but there were concerns regarding their responsiveness to the change in QoL overtime. Given the current requirement in countries such as the UK to report QALY (typically using the EQ-5D instrument) as the preferred outcome measure in economic evaluations, it is therefore important to ensure adequately broader estimation of PwP’s utilities for resource allocation decisions in Parkinson’s. The development of methods to incorporate broader aspects into health care decision making may represent a valuable research development in this area. In addition, incorporation of the Parkinson’s specific QoL measures would be beneficial alongside a generic PbQoL measure in longitudinal studies as to sensitively capture the full impact of QoL by Parkinson’s.

Abbreviations

- AQoL:

-

Assessment of Quality of Life

- CBA:

-

Cost-benefit analysis

- CS-PBM:

-

Condition-specific preference-based measure

- CUA:

-

Cost-utility analysis

- DDI:

-

Disability and Distress Index

- EQ-5D:

-

EuroQoL EQ-5D

- HAD:

-

Hospital Anxiety and Depression scale

- HUI:

-

Health Utilities Index

- H&Y:

-

Hoehn and Yahr scale

- ICER:

-

Incremental cost-effectiveness ratio

- MCID:

-

Minimal clinically important difference

- NICE:

-

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence

- PbQoL:

-

Preference-based quality of life

- PDQ-39:

-

Parkinson’s Disease Questionnaire-39-item

- PDQ-39-SI:

-

Parkinson’s Disease Questionnaire-39-item-Summary Index

- PDQL:

-

Parkinson’s Disease Quality of Life questionnaire

- PDQUALIF:

-

Parkinson’s Disease QUAlity of LIFe scale

- PwP:

-

People with Parkinson’s

- QALY:

-

Quality-adjusted life-years

- QoL:

-

Quality of life

- RCT:

-

Randomized controlled trials

- SF-6D:

-

Short-Form 6-Dimension

- SF-36:

-

Short-Form 36-item

- SG:

-

Standard gamble

- TTO:

-

Time trade-off

- UPDRS:

-

Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale

- VAS:

-

Visual analogue scale

References

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Glossary—QALYs. https://www.nice.org.uk/glossary?letter=q. Accessed 09 Apr 2015.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. (2012). Appendix G: Methodology checklist: economic evaluations (PMG6B). https://www.nice.org.uk/article/pmg6b/chapter/appendix-g-methodology-checklist-economic-evaluations. Accessed 07 April 2016.

von Neumann, J., & Morgenstern, O. (1944). Theory of games and economic behaviour. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Holloway, C. (1979). Decision making under uncertainty: models and choices. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall.

Torrance, G. W., Thomas, W. H., & Sackett, D. L. (1972). A utility maximization model for evaluation of health care programs. Health Service Research, 7(2), 118–133.

EuroQol Group. (1990). EuroQol–a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy, 16(3), 199–208.

Herdman, M., Gudex, C., Lloyd, A., Janssen, M., Kind, P., Parkin, D., et al. (2011). Development and preliminary testing of the new five-level version of EQ-5D (EQ-5D-5L). Quality of Life Research, 20(10), 1727–1736.

Brazier, J., Roberts, J., & Deverill, M. (2002). The estimation of a preference-based measure of health from the SF-36. Journal of Health Economics, 21(2), 271–292.

Torrance, G. W., Feeny, D. H., Furlong, W. J., Barr, R. D., Zhang, Y., & Wang, Q. (1996). Multiattribute utility function for a comprehensive health status classification system. Health Utilities Index Mark 2. Medical Care, 34(7), 702–722.

Feeny, D., Furlong, W., Torrance, G. W., Goldsmith, C. H., Zhu, Z., DePauw, S., et al. (2002). Multiattribute and single-attribute utility functions for the health utilities index mark 3 system. Medical Care, 40(2), 113–128.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. (2013). PMG9 guide to the methods of technology appraisal. 5.3 measuring and valuing health effects. https://www.nice.org.uk/article/pmg9/chapter/the-reference-case#measuring-and-valuing-health-effects. Accessed 07 April 2016.

Brazier, J. (2010). Is the EQ-5D fit for purpose in mental health? British Journal of Psychiatry, 197(5), 348–349.

Papaioannou, D., Brazier, J., & Parry, G. (2011). How valid and responsive are generic health status measures, such as EQ-5D and SF-36, in Schizophrenia? A systematic review. Value in Health, 14(6), 907–920.

Garau, M., Shah, K., Towse, A., Wang, Q., Drummond, M., Mason, A. (2009). Assessment and appraisal of oncology medicines: Does NICE’s approach include all relevant elements? What can be learnt from international HTA experiences? Report for the Pharmaceutical Oncology Initiative (POI). Office of Health Economics, London. https://www.ohe.org/publications/assessment-and-appraisal-oncology-medicines-nices-approach-and-international-hta. Accessed 16 Aug 2015.

Riepe, M. W., Mittendorf, T., Forstl, H., Frolich, L., Haupt, M., Leidl, R., et al. (2009). Quality of life as an outcome in Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias–obstacles and goals. BMC Neurology, 9, 47.

Hounsome, N., Orrell, M., & Edwards, R. T. (2011). EQ-5D as a quality of life measure in people with dementia and their carers: evidence and key issues. Value in Health, 14(2), 390–399.

Wailoo, A., Davis, S., & Tosh, J. (2010). The incorporation of health benefits in cost utility analysis using the EQ-5D. Report by the decision support unit http://www.nicedsu.org.uk/PDFs%20of%20reports/DSU%20EQ5D%20final%20report%20-%20submitted.pdf. Accessed 20 July 2015.

Longworth, L., Yang, Y., Young, T., Mulhern, B., Hernandez Alava, M., Mukuria, C., et al. (2014). Use of generic and condition-specific measures of health-related quality of life in NICE decision-making: a systematic review, statistical modelling and survey. Health Technology Assessment, 18(9), 1–224.

Rowen, D., Mulhern, B., Banerjee, S., Tait, R., Watchurst, C., Smith, S. C., et al. (2015). Comparison of general population, patient, and carer utility values for dementia health states. Medical Decision Making, 35(1), 68–80.

Moock, J., & Kohlmann, T. (2008). Comparing preference-based quality-of-life measures: results from rehabilitation patients with musculoskeletal, cardiovascular, or psychosomatic disorders. Quality of Life Research, 17(3), 485–495.

Barton, G. R., Sach, T. H., Avery, A. J., Jenkinson, C., Doherty, M., Whynes, D. K., et al. (2008). A comparison of the performance of the EQ-5D and SF-6D for individuals aged > or = 45 years. Health Economics, 17(7), 815–832.

McDonough, C. M., Grove, M. R., Tosteson, T. D., Lurie, J. D., Hilibrand, A. S., & Tosteson, A. N. (2005). Comparison of EQ-5D, HUI, and SF-36-derived societal health state values among spine patient outcomes research trial (SPORT) participants. Quality of Life Research, 14(5), 1321–1332.

Brazier, J., Roberts, J., Tsuchiya, A., & Busschbach, J. (2004). A comparison of the EQ-5D and SF-6D across seven patient groups. Health Economics, 13(9), 873–884.

Macran, S., Weatherly, H., & Kind, P. (2003). Measuring population health: a comparison of three generic health status measures. Medical Care, 41(2), 218–231.

Richardson, J., Khan, M. A., Iezzi, A., & Maxwell, A. (2015). Comparing and explaining differences in the magnitude, content, and sensitivity of utilities predicted by the EQ-5D, SF-6D, HUI 3, 15D, QWB, and AQoL-8D multiattribute utility instruments. Medical Decision Making, 35(3), 276–291.

Jenkinson, C., Fitzpatrick, R., Peto, V., Harris, R., & Saunders, P. (2008). The Parkinson’s disease questionnaire PDQ-39 user manual (including PDQ-9 and PDQ summary index): Health Services Research Unit (2nd ed.). Oxford: University of Oxford.

Jenkinson, C., Fitzpatrick, R., Peto, V., Greenhall, R., & Hyman, N. (1997). The Parkinson’s disease questionnaire (PDQ-39): development and validation of a Parkinson’s disease summary index score. Age and Ageing, 26(5), 353–357.

Brazier, J. E., Rowen, D., Mavranezouli, I., Tsuchiya, A., Young, T., Yang, Y., et al. (2012). Developing and testing methods for deriving preference-based measures of health from condition-specific measures (and other patient-based measures of outcome). Health Technology Assessment, 16(32), 1–114.

Versteegh, M. M., Leunis, A., Uyl-de Groot, C. A., & Stolk, E. A. (2012). Condition-specific preference-based measures: benefit or burden? Value in Health, 15(3), 504–513.

de Lau, L. M., & Breteler, M. M. (2006). Epidemiology of Parkinson’s disease. Lancet Neurology, 5(6), 525–535.

Rahman, S., Griffin, H. J., Quinn, N. P., & Jahanshahi, M. (2008). Quality of life in Parkinson’s disease: The relative importance of the symptoms. Movement Disorders, 23(10), 1428–1434.

Gallagher, D. A., Lees, A. J., & Schrag, A. (2010). What are the most important nonmotor symptoms in patients with Parkinson’s disease and are we missing them? Movement Disorders, 25(15), 2493–2500.

Martinez-Martin, P., Rodriguez-Blazquez, C., Kurtis, M. M., & Chaudhuri, K. R. (2011). The impact of non-motor symptoms on health-related quality of life of patients with Parkinson’s disease. Movement Disorders, 26(3), 399–406.

Chapuis, S., Ouchchane, L., Metz, O., Gerbaud, L., & Durif, F. (2005). Impact of the motor complications of Parkinson’s disease on the quality of life. Movement Disorders, 20(2), 224–230.

Winter, Y., von Campenhausen, S., Gasser, J., Seppi, K., Reese, J. P., Pfeiffer, K. P., et al. (2010). Social and clinical determinants of quality of life in Parkinson’s disease in Austria: A cohort study. Journal of Neurology, 257(4), 638–645.

Behari, M., Srivastava, A. K., & Pandey, R. M. (2005). Quality of life in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism and Related Disorders, 11(4), 221–226.

Gomez-Esteban, J. C., Zarranz, J. J., Lezcano, E., Tijero, B., Luna, A., Velasco, F., et al. (2007). Influence of motor symptoms upon the quality of life of patients with Parkinson’s disease. European Neurology, 57(3), 161–165.

Saarni, S. I., Harkanen, T., Sintonen, H., Suvisaari, J., Koskinen, S., Aromaa, A., et al. (2006). The impact of 29 chronic conditions on health-related quality of life: A general population survey in Finland using 15D and EQ-5D. Quality of Life Research, 15(8), 1403–1414.

Martinez-Martin, P., Jeukens-Visser, M., Lyons, K. E., Rodriguez-Blazquez, C., Selai, C., Siderowf, A., et al. (2011). Health-related quality-of-life scales in Parkinson’s disease: critique and recommendations. Movement Disorders, 26(13), 2371–2380.

Soh, S. E., McGinley, J., & Morris, M. E. (2011). Measuring quality of life in Parkinson’s disease: Selection of-an-appropriate health-related quality of life instrument. Physiotherapy, 97(1), 83–89.

Dodel, R., Jonsson, B., Reese, J. P., Winter, Y., Martinez-Martin, P., Holloway, R., et al. (2014). Measurement of costs and scales for outcome evaluation in health economic studies of Parkinson’s disease. Movement Disorders, 29(2), 169–176.

Martinez-Martin, P., Gil-Nagel, A., Gracia, L. M., Gomez, J. B., Martinez-Sarries, J., & Bermejo, F. (1994). Unified Parkinson’s disease rating scale characteristics and structure. The Cooperative Multicentric Group. Movement Disorders, 9(1), 76–83.

Hoehn, M. M., & Yahr, M. D. (1967). Parkinsonism: Onset, progression and mortality. Neurology, 17(5), 427–442.

Maccorquodale, K., & Meehl, P. E. (1948). On a distinction between hypothetical constructs and intervening variables. Psychological Review, 55(2), 95–107.

Cronbach, L. J., & Meehl, P. E. (1955). Construct validity in psychological tests. Psychological Bulletin—American Psychological Association, 52(4), 281–302.

Tosh, J., Brazier, J., Evans, P., & Longworth, L. (2012). A review of generic preference-based measures of health-related quality of life in visual disorders. Value in Health, 15(1), 118–127.

Janssen, M. F., Pickard, A. S., Golicki, D., Gudex, C., Niewada, M., Scalone, L., et al. (2013). Measurement properties of the EQ-5D-5L compared to the EQ-5D-3L across eight patient groups: A multi-country study. Quality of Life Research, 22(7), 1717–1727.

Bowling, A., & Ebrahim, S. (2005). Handbook of health research methods. Investigation, measurement and analysis. Open University Press, Maidenhead.

Brazier, J., Deverill, M., Green, C., Harper, R., & Booth, A. (1999). A review of the use of health status measures in economic evaluation. Health Technology Assessment, 3(9), 1–164.

Hattie, J., & Cooksey, R. (1984). Procedures for assessing the validities of tests using the “known-groups” method. Applied Psychological Measurement, 8(3), 295–305.

Carmines, E. G., & Zeller, R. A. (1979). Reliability and validity assessment. Beverly Hills: Sage.

Beaton, D. E., Bombardier, C., Katz, J. N., & Wright, J. G. (2001). A taxonomy for responsiveness. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 54(12), 1204–1217.

Stratford, P. W., Binkley, J. M., Riddle, D. L., & Guyatt, G. H. (1998). Sensitivity to change of the Roland-Morris back pain questionnaire: Part 1. Physical Therapy, 78(11), 1186–1196.

Benito-Leon, J., Cubo, E., & Coronell, C. (2012). Impact of apathy on health-related quality of life in recently diagnosed Parkinson’s disease: The ANIMO study. Movement Disorders, 27(2), 211–218.

Garcia-Gordillo, M. A., Del Pozo-Cruz, B., Adsuar, J. C., Sanchez-Martinez, F. I., & Abellan-Perpinan, J. M. (2013). Validation and comparison of 15-D and EQ-5D-5L instruments in a Spanish Parkinson’s disease population sample. Quality of Life Research, 23(4), 1315–1326.

Jones, C. A., Pohar, S. L., & Patten, S. B. (2009). Major depression and health-related quality of life in Parkinson’s disease. General Hospital Psychiatry, 31(4), 334–340.

Luo, N., Low, S., Lau, P. N., Au, W. L., & Tan, L. C. (2009). Is EQ-5D a valid quality of life instrument in patients with Parkinson’s disease? A study in Singapore. ANNALS Academy of Medicine Singapore, 38(6), 521–528.

Martinez-Martin, P., Rodriguez-Blazquez, C., Forjaz, M. J., Alvarez-Sanchez, M., Arakaki, T., Bergareche-Yarza, A., et al. (2014). Relationship between the MDS-UPDRS domains and the health-related quality of life of Parkinson’s disease patients. European Journal of Neurology, 21(3), 519–524.

Pohar, S. L., & Allyson Jones, C. (2009). The burden of Parkinson disease (PD) and concomitant comorbidities. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 49(2), 317–321.

Rodriguez-Blazquez, C., Forjaz, M. J., Frades-Payo, B., de Pedro-Cuesta, J., & Martinez-Martin, P. (2010). Independent validation of the scales for outcomes in Parkinson’s disease-autonomic (SCOPA-AUT). European Journal of Neurology, 17(2), 194–201.

Rodriguez-Blazquez, C., Rojo-Abuin, J. M., Alvarez-Sanchez, M., Arakaki, T., Bergareche-Yarza, A., Chade, A., et al. (2013). The MDS-UPDRS Part II (motor experiences of daily living) resulted useful for assessment of disability in Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism & Related Disorders, 19(10), 889–893.

Siderowf, A., Ravina, B., & Glick, H. A. (2002). Preference-based quality-of-life in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Neurology, 59(1), 103–108.

Swinn, L., Schrag, A., Viswanathan, R., Bloem, B. R., Lees, A., & Quinn, N. (2003). Sweating dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease. Movement Disorders, 18(12), 1459–1463.

Daley, D. J., Deane, K. H., Gray, R. J., Clark, A. B., Pfeil, M., Sabanathan, K., et al. (2014). Adherence therapy improves medication adherence and quality of life in people with Parkinson’s disease: a randomised controlled trial. International Journal of Clinical Practice, 68(8), 963–971.

Ebersbach, G., Hahn, K., Lorrain, M., & Storch, A. (2010). Tolcapone improves sleep in patients with advanced Parkinson’s disease (PD). Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 51(3), e125–e128.

Jarman, B., Hurwitz, B., Cook, A., Bajekal, M., & Lee, A. (2002). Effects of community based nurses specialising in Parkinson’s disease on health outcome and costs: Randomised controlled trial. BMJ, 324(7345), 1072–1075.

Larisch, A., Reuss, A., Oertel, W. H., & Eggert, K. (2011). Does the clinical practice guideline on Parkinson’s disease change health outcomes? A cluster randomized controlled trial. Journal of Neurology, 258(5), 826–834.

Luo, N., Ng, W. Y., Lau, P. N., Au, W. L., & Tan, L. C. (2010). Responsiveness of the EQ-5D and 8-item Parkinson’s disease questionnaire (PDQ-8) in a 4-year follow-up study. Quality of Life Research, 19(4), 565–569.

Noyes, K., Dick, A. W., & Holloway, R. G. (2006). Pramipexole versus levodopa in patients with early Parkinson’s disease: Effect on generic and disease-specific quality of life. Value in Health, 9(1), 28–38.

Nyholm, D., Nilsson Remahl, A. I., Dizdar, N., Constantinescu, R., Holmberg, B., Jansson, R., et al. (2005). Duodenal levodopa infusion monotherapy versus oral polypharmacy in advanced Parkinson disease. Neurology, 64(2), 216–223.

Reuther, M., Spottke, E. A., Klotsche, J., Riedel, O., Peter, H., Berger, K., et al. (2007). Assessing health-related quality of life in patients with Parkinson’s disease in a prospective longitudinal study. Parkinsonism & Related Disorders, 13(2), 108–114.

Schroder, S., Martus, P., Odin, P., & Schaefer, M. (2012). Impact of community pharmaceutical care on patient health and quality of drug treatment in Parkinson’s disease. International Journal of Clinical Pharmacy, 34(5), 746–756.

Stocchi, F., Giorgi, L., Hunter, B., & Schapira, A. H. (2011). PREPARED: Comparison of prolonged and immediate release ropinirole in advanced Parkinson’s disease. Movement Disorders, 26(7), 1259–1265.

Trend, P., Kaye, J., Gage, H., Owen, C., & Wade, D. (2002). Short-term effectiveness of intensive multidisciplinary rehabilitation for people with Parkinson’s disease and their carers. Clinical Rehabilitation, 16(7), 717–725.

Wade, D. T., Gage, H., Owen, C., Trend, P., Grossmith, C., & Kaye, J. (2003). Multidisciplinary rehabilitation for people with Parkinson’s disease: A randomised controlled study. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry, 74(2), 158–162.

Zhu, X. L., Chan, D. T., Lau, C. K., Poon, W. S., Mok, V. C., Chan, A. Y., et al. (2014). Cost-effectiveness of subthalmic nucleus deep brain stimulation for the treatment of advanced Parkinson disease in Hong Kong: A prospective study. World Neurosurgery, 82(6), 987–993.

Rosser, R. M., & Watts, V. C. (1972). The measurement of hospital output. International Journal of Epidemiology, 1(4), 361–368.

Rosser, R., & Kind, P. (1978). A scale of valuations of states of illness: Is there a social consensus? International Journal of Epidemiology, 7(4), 347–358.

Gudex, C., & Kind, P. (1989). The QALY tool kit—Discussion Paper 38. York: Centre for Health Economics, University of York. http://www.york.ac.uk/che/pdf/dp38.pdf. Accessed 01 April 2016.

Sintonen, H. (2001). The 15D instrument of health-related quality of life: Properties and applications. Annals of Medicine, 33(5), 328–336.

Kristiansen, I. S., Bingefors, K., Nyholm, D., & Isacson, D. (2009). Short-term cost and health consequences of duodenal levodopa infusion in advanced Parkinson’s disease in Sweden: An exploratory study. Applied Health Economics and Health Policy, 7(3), 167–180.

Lundqvist, C., Beiske, A. G., Reiertsen, O., & Kristiansen, I. S. (2014). Real life cost and quality of life associated with continuous intraduodenal levodopa infusion compared with oral treatment in Parkinson patients. Journal of Neurology, 261(12), 2438–2445.

Martinez-Martin, P., Rodriguez-Blazquez, C., Abe, K., Bhattacharyya, K. B., Bloem, B. R., Carod-Artal, F. J., et al. (2009). International study on the psychometric attributes of the non-motor symptoms scale in Parkinson disease. Neurology, 73(19), 1584–1591.

Soh, S.-E., Morris, M. E., & McGinley, J. L. (2011). Determinants of health-related quality of life in Parkinson’s disease: A systematic review. Parkinsonism & Related Disorders, 17(1), 1–9.

McDonough, C. M., & Tosteson, A. N. (2007). Measuring preferences for cost-utility analysis: How choice of method may influence decision-making. Pharmacoeconomics, 25(2), 93–106.

Yang, Y., Brazier, J. E., Tsuchiya, A., & Young, T. A. (2011). Estimating a preference-based index for a 5-dimensional health state classification for asthma derived from the asthma quality of life questionnaire. Medical Decision Making, 31(2), 281–291.

Brazier, J., Czoski-Murray, C., Roberts, J., Brown, M., Symonds, T., & Kelleher, C. (2008). Estimation of a preference-based index from a condition-specific measure: The King’s Health Questionnaire. Medical Decision Making, 28(1), 113–126.

Brazier, J., & Tsuchiya, A. (2010). Preference-based condition-specific measures of health: What happens to cross programme comparability? Health Economics, 19(2), 125–129.

Luo, N., Johnson, J. A., Shaw, J. W., & Coons, S. J. (2009). Relative efficiency of the EQ-5D, HUI2, and HUI3 index scores in measuring health burden of chronic medical conditions in a population health survey in the United States. Medical Care, 47(1), 53–60.

McDonough, C. M., Tosteson, T. D., Tosteson, A. N., Jette, A. M., Grove, M. R., & Weinstein, J. N. (2011). A longitudinal comparison of 5 preference-weighted health state classification systems in persons with intervertebral disk herniation. Medical Decision Making, 31(2), 270–280.

Sung, L., Greenberg, M. L., Doyle, J. J., Young, N. L., Ingber, S., Rubenstein, J., et al. (2003). Construct validation of the health utilities index and the child health questionnaire in children undergoing cancer chemotherapy. British Journal of Cancer, 88(8), 1185–1190.

Peto, V., Jenkinson, C., & Fitzpatrick, R. (2001). Determining minimally important differences for the PDQ-39 Parkinson’s disease questionnaire. Age and Ageing, 30(4), 299–302.

Winter, Y., Lubbe, D., Oertel, W. H., & Dodel, R. (2012). Determining minimal clinically important difference for healthrelated quality of life scales in Parkinson’s disease. Movement Disorders, 27, S106.

Ware, J. E., Jr., & Sherbourne, C. D. (1992). The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Medical Care, 30(6), 473–483.

Welsh, M., McDermott, M. P., Holloway, R. G., Plumb, S., Pfeiffer, R., & Hubble, J. (2003). Development and testing of the Parkinson’s disease quality of life scale. Movement Disorders, 18(6), 637–645.

de Boer, A. G., Wijker, W., Speelman, J. D., & de Haes, J. C. (1996). Quality of life in patients with Parkinson’s disease: Development of a questionnaire. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry, 61(1), 70–74.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Dr. Emma McIntosh is funded by a Parkinson’s UK Senior Fellowship. Yiqiao Xin declared no conflict of interest.

Human and animal rights

This manuscript is a systematic review which only contains data from previously published studies. No clinical trials were conducted nor patient data were collected for this research.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Xin, Y., McIntosh, E. Assessment of the construct validity and responsiveness of preference-based quality of life measures in people with Parkinson’s: a systematic review. Qual Life Res 26, 1–23 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-016-1428-x

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-016-1428-x