Abstract

Patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder have a high prevalence of comorbid cannabis use disorder (CUD). CUD has been associated with poorer outcomes in patients. We compared doses of antipsychotic medications at the time of discharge from hospital among inpatients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder with or without concurrent cannabis use. We reviewed the medical records of patients (N = 8157) with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder discharged from the hospital between 2008 and 2012. The patients were divided into two groups; those with urine drug tests positive for cannabis and those negative for cannabis. Doses of antipsychotic medications were converted to chlorpromazine equivalents. Bivariate analyses were done with Student’s t test for continuous variables and χ 2 test for categorical variables. Linear regression was carried out to adjust for potential confounders. Unadjusted analysis revealed that the cannabis positive group was discharged on lower doses of antipsychotic medication compared with the cannabis negative group (geometric mean chlorpromazine equivalent doses 431.22 ± 2.20 vs 485.18 ± 2.21; P < 0.001). However, the difference in geometric mean chlorpromazine equivalent doses between the two groups was no longer significant after adjusting for sex, age, race, and length of stay (geometric mean difference 0.99; 95 % CI 0.92–1.10). Though limited by lack of information on duration, amount and severity of cannabis use, as well as inability to control for other non-antipsychotic medications, our study suggests that cannabis use did not significantly impact on doses of antipsychotics required during the periods of acute exacerbation in patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Schizophrenia is a severe, chronic psychiatric disorder with an estimated prevalence rate of 0.5–1 % [1]. Schizophrenia has a huge impact on the patients, their families, caregivers and the society at large. On average, people with schizophrenia die 15–20 years earlier than individuals in the general population and illicit drug use is one of the factors associated with the increased risk of mortality in the disorder [2]. Schizophrenia is also associated with a huge economic burden on the society and a recent study found that the average total claim cost per patient with schizophrenia was more than four times the average claim cost for a demographically adjusted population without schizophrenia [3]. Schizoaffective disorder is characterized by features of schizophrenia occurring concurrently with a mood episode; there is also a 2-week period (or more) in which psychotic symptoms persist in the absence of a mood episode during the lifetime duration of the illness [4]. There is a significant degree of overlap in the genes contributing to both schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder [5, 6] and resting state fMRI using group information guided independent component analysis revealed close similarity between the two disorders [7]. The relatedness between schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder is also reflected by the fact that both disorders have been grouped together under the “Schizophrenia Spectrum and Other Psychotic Disorders” section of DSM-5 [8].

Cannabis (commonly known as marijuana) is a psychoactive drug derived from the Cannabis plant, a species of the Cannabinaceae family. Globally, it is estimated that up to 4 % of all adults use cannabis [9]. The popularity of Cannabis can be partly attributed to its widespread availability and the associated euphorigenic effects. These euphorigenic properties are derived primarily from ∆9-tetrahydrocannabinol (∆9-THC). ∆9-THC is one of over 80 cannabinoids present in cannabis [10] and it exerts its effect by binding to cannabinoid CB1 receptors on pre-synaptic nerve terminals in the brain [11]. Whereas, the presence of THC in cannabis increases the risk of psychosis, cannabidiol (CBD), another key cannabinoid may reduce the risk of psychosis and also has mood stabilizing effects [12]. However, because most currently available cannabis preparations are high in THC, with little proportions of other cannabinoids, the overall outcome of cannabis usage is increased risk of psychosis [13, 14].

There is a strong comorbidity between both schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder and cannabis use disorder (CUD) [15]. Cannabis usage can impact negatively on individuals with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder and can potentially lead to a significantly lower quality of life [16, 17]. Individuals with schizophrenia may also be particularly vulnerable to the negative effects of ∆9-THC including increased learning and recall deficits, increased psychotic symptoms, perceptual alterations, and deficits in vigilance [18]. However, in some studies, patients with schizophrenia reported that cannabis provided relief from psychiatric symptoms, boredom and depression, and from the side effects of antipsychotic medications [19–22].

The few clinical trials of antipsychotic medications in individuals with a dual diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder and cannabis use disorder CUD involved the use of second generation antipsychotics which resulted in a reduction in cannabis use [23, 24]. However, there is currently a paucity of studies designed to evaluate the impact of cannabis use on doses of antipsychotic medications in individuals with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder during periods of acute exacerbation of psychosis. Furthermore, the few available studies have yielded conflicting results; one study reported higher doses of antipsychotics in patients with schizophrenia without CUD [25] in comparison with those with CUD and another reported no difference between individuals with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder with or without CUD [26]. To further the understanding of the impact of cannabis on doses of antipsychotic medications in schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder, we have now carried out a comparison of doses of antipsychotic medication at the time of discharge from hospital, between individuals with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder with urine drug screen (UDS) results positive for cannabis (CP) and those with negative UDS results (CN). Based on our expectation that individuals with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder with CUD will be more difficult to treat during periods of exacerbation of psychosis, we hypothesized that CP patients will be discharged on higher doses of antipsychotic medication when compared with CN patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder.

Methods

Population and Setting

We examined the medical records of adults (N = 8157) discharged from hospital between 2008 and 2012 and diagnosed with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder by a psychiatrist according to Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 4th Edition (DSM-IV) criteria. The hospital is a stand-alone psychiatric hospital located in a major city in the United States and affiliated with a University Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences. In an attempt to reduce the probability of including cases of substance-induced psychosis, we did not include individuals with a diagnosis of schizophreniform disorder or psychotic disorder not otherwise specified. All the patients were admitted due to acute exacerbation of psychosis and were treated with antipsychotic medications. To facilitate the comparison of doses of antipsychotic medications between patient groups, we converted the discharge doses of antipsychotic medications (for each individual patient) to chlorpromazine equivalents [27]. The various antipsychotic medications prescribed in this sample included Haloperidol, Fluphenazine, Aripiprazole, Ziprasidone, Olanzapine, Risperidone, Clozapine and Quetiapine. We gathered data on patient’s age, gender, race, and UDS results (at admission). This study was approved by the Institutional review board of the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston.

Urine Drug Testing

Immunoassay was used as an initial screening process to test for the presence or absence of cannabis in urine specimens collected at the time of admission. Gas chromatography/mass spectrometry (GC/MS) was used to confirm positive cannabis screening specimens and to provide quantitative results, expressed in nanograms per milliliter. The initial immunoassay screening cutoff level for cannabis was 50 ng/ml. The GC/MS confirmation cutoff level for cannabis was 15 ng/ml [28].

Statistical Analyses

We applied logarithmic transformation to chlorpromazine equivalent doses and length of hospital stay (both variables were skewed to the right) in an attempt to normalize the distribution of both variables. T tests and χ 2 tests were used to compare demographic variables between CP patients and CN patients. Unadjusted comparison of discharge chlorpromazine equivalent doses between CP and CN patients involved the use of t test while adjusted analysis was carried out using linear regression (adjusting for differences in age, gender, race, and length of stay in hospital). We have presented geometric mean doses with 95 % confidence intervals (obtained by calculating the antilog of the log-transformed mean differences) for the difference in chlorpromazine equivalents between the two patient groups. The analyses were also repeated after excluding readmissions. All significance levels reported are two-sided with P < 0.05 considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were carried out using IBM SPSS version 20 (Armonk, NY: IBM CorP).

Results

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of the Sample

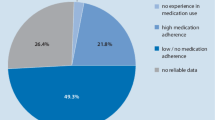

Between 2008 and 2012, 8157 individuals were discharged from the hospital with either a diagnosis of Schizophrenia or Schizoaffective disorder. Out of the 8157 individuals, 7838 had complete data with 5106 individuals having a discharge diagnosis of schizophrenia and 2732 individuals having a discharge diagnosis of schizoaffective disorder according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition (DSM-IV). Upon exclusion of individuals with Urine drug screening positive for other illicit substances besides cannabis, 660 CP and 4871 CN individuals with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder were included in the final analyses.

Patients with cannabis-positive urine test results were younger than patients with cannabis-negative test results (29.67 ± 9.55 vs 38.62 ± 12.67 years, respectively; P < 0.001). In terms of ethnicity, there were more blacks (63.7 vs 55.1 %; P < 0.001) and Hispanics (17. 6 vs 15.9 %; P < 0.001) but fewer whites (17.2 vs 24.4 %; P < 0.001) and Asians (1.1 vs 4.1 %; P < 0.001) in the cannabis-positive group versus the cannabis negative group. There were gender differences between the two groups with males being more represented (83.5 vs 67.3 %; P < 0.001) in the cannabis positive group. The geometric mean hospital length of stay was less in the cannabis-positive patients (Table 1).

Comparison of Discharge Antipsychotic Doses

Unadjusted analysis revealed that the cannabis positive group was discharged on lower doses of antipsychotic medication compared with the cannabis negative group (geometric mean chlorpromazine equivalent doses 431.22 ± 2.20 vs 485.18 ± 2.21; P < 0.001). However, the difference in geometric mean chlorpromazine equivalent doses between the two patient groups was no longer significant after adjusting for sex, age, race, and length of stay (geometric mean difference 0.99; 95 % CI 0.92–1.10). Similar results were obtained after excluding readmission.

Discussion

Our results suggest that current cannabis use was not related to the discharge doses of antipsychotic medications for patients with either schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder who were also either positive or negative for cannabis. Even though several studies have reported co-morbid cannabis use disorder in patients with psychotic spectrum illnesses including schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder [29–31], there is a paucity of studies evaluating the required amount of antipsychotic medications in the acute psychiatric inpatient setting where patients with exacerbation of psychotic symptoms are treated. The decision to focus on doses of discharge antipsychotic medications was based on our assumption that the dose of antipsychotic medication a patient receives at the time of discharge from hospital is likely to be highest dose required to stabilize the patient. Furthermore, the highest dose of antipsychotic medication required by a patient could also be a proxy measure of severity of illness. We had therefore expected that the patients with urine drug tests positive for cannabis would require higher doses of antipsychotic medication based on our expectation that cannabis would have worsened their psychotic symptoms to a significant degree [32] and that their psychotic symptoms would be more difficult to treat in comparison with the patients that did not test positive for cannabis.

A previous study by Makkos et al. [25] found that cannabis-using individuals with schizophrenia required lower doses of antipsychotic medications. We also observed this finding in our bivariate analysis but after adjusting for potential confounders, we did not observe any statistically significant differences in the amount of antipsychotic medications at discharge. However, it is important to note some important differences between the current study and the one by Makkos et al. including the fact that Makkos et al. had a smaller sample size (N = 85) and even though they observed significantly lower dosing requirement in Quetiapine, Olanzapine and Risperidone they did not base their analysis on chlorpromazine equivalent doses.

Although the exact mechanisms that can explain the failure to elicit any significant difference in the amount of antipsychotic medication prescribed during periods of exacerbation of psychosis among cannabis positive versus cannabis negative patients in our sample are not known to us, we will proffer a number of possible mechanisms. First, the patients that tested positive for cannabis might indeed have had exacerbations of their symptoms precipitated by their recent cannabis use. However, as cannabis was metabolized and cleared from their system, their symptoms might have improved, which subsequently eliminated the need for doses of antipsychotic medications higher than that required by patients that tested negative for cannabis. Second, it is possible that the use of other concomitant medications such as mood stabilizers and benzodiazepines may not have been evenly distributed between the two patient populations which could have therefore confounded the relationship between cannabis use and doses of antipsychotic medications in this sample. Lastly, it could just be that cannabis does not impact the neurobiology of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder in such a way as to have an effect on required doses of antipsychotic medications during periods of exacerbation of psychosis, i.e. even though cannabis might worsen psychosis in schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder, the symptoms still remain responsive to medications just as in patients that do not use cannabis.

We recognize several limitations of our study, including: the cross sectional design; diagnosis by psychiatrist based on DSM IV but not by the structured clinical interview for DSM-IV; inability to adjust for concurrent use of other medications (such as mood stabilizers, anti-depressants, anxiolytics) or symptom severity. Moreover, our determination of cannabis use was based solely on UDS, so we could not account for the amount, duration, length and severity of cannabis use. The strengths of our study include the large sample size, heterogeneity of patient population providing good external validity, validation of cannabis use status by UDS rather than self report, and adjustment for several potential confounders including length of stay during hospitalization.

In conclusion, our adjusted analysis did not reveal any significant difference in doses of antipsychotic medication at the time of discharge from hospital in patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder positive or negative for cannabis. Longitudinal studies are needed to further evaluate this association and such studies should aim to gather information on duration, amount and severity of cannabis use as well as information on other classes of medication used in this patients including, anxiolytics, antidepressants and mood stabilizers.

References

Black DW, Andreasen NC: Introductory Textbook of Psychiatry, 6th edn., Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc, 2014.

Reininghaus U, Dutta R, Dazzan P, Doody GA, Fearon P, Lappin J, Heslin M, Onyejiaka A, Donoghue K, Lomas B, Kirkbride JB, Murray RM, Croudace T, Morgan C, Jones PB: Mortality in schizophrenia and other psychoses: A 10-year follow-up of the ӔSOP first-episode cohort. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 2014 [Epub ahead of print].

Fitch K, Iwasaki K, Villa KF: Resource utilization and cost in a commercially insured population with schizophrenia. American Health & Drug Benefits 7(1):18–26, 2014.

Malaspina D, Owen MJ, Heckers S, Tandon R, Bustillo J, Schultz S, Barch DM, Gaebel W, Gur RE, Tsuang M, Van Os J, Carpenter W: Schizoaffective disorder in the DSM-5″. Schizophrenia Research 150(1):21–25, 2013. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2013.04.026.

Cardno AG, Rijsdijk FV, Sham PC, Murray RM, McGuffin P: A twin study of genetic relationships between psychotic symptoms. American Journal of Psychiatry 159(4):539–545, 2002.

Cardno AG, Owen MJ: Genetic relationships between schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and schizoaffective disorder. Schizophrenia Bulletin 40(3):504–515, 2014.

Du Y, Liu J, Sui J, He H, Pearlson GD, Calhoun VD: Exploring difference and overlap between schizophrenia, schizoaffective and bipolar disorders using resting-state brain functional networks. IEEE Conference on Proceedings of Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society 2014:1517–1520, 2014.

American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edn., Arlington, American Psychiatric Publishing, 2013.

Rodrigo C, Rajapakse S: Cannabis and Schizophrenia spectrum disorders: A review of clinical studies. Indian Journal of Psychological Medicine 31(2):62–70, 2009.

Golub AL (Ed): The Cultural/Subcultural Contexts of Marijuana Use at the Turn of the Twenty-First Century. New York, Routledge, 2005.

Yamamoto T, Takada K: Role of cannabinoid receptor in the brain as it relates to drug reward. The Japanese Journal of Pharmacology 84(3):229–236, 2000.

Schubart CD, Sommer IE, Fusar-Poli P, de Witte L, Kahn RS, Boks MP: Cannabidiol as a potential treatment for psychosis. European Neuropsychopharmacology 24(1):51–64, 2014.

ElSohly MA, Ross SA, Mehmedic Z, Arafat R, Yi B, Banahan 3rd BF: Potency trends of delta9-THC and other cannabinoids in confiscated marijuana from 1980-1997. Journal of Forensic Sciences 45(1):24–30, 2000.

Radhakrishnan R, Wilkinson ST, D’Souza DC: Gone to Pot—A review of the association between cannabis and psychosis. Front Psychiatry 5:54, 2014.

Koskinen J, Löhönen J, Koponen H, Isohanni M, Miettunen J: Rate of cannabis use disorders in clinical samples of patients with schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Schizophrenia Bulletin 36(6):1115–1130, 2010.

Linszen DH, Dingemans PM, Lenior ME: Cannabis abuse and the course of recent-onset schizophrenic disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry 51(4):273–279, 1994.

Foti DJ, Kotov R, Guey LT, Bromet EJ: Cannabis use and the course of schizophrenia: 10-Year follow-up after first hospitalization. American Journal of Psychiatry 167(8):987–993, 2010.

D’Souza DC, Abi-Saab WM, Madonick S, et al.: Delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol effects in schizophrenia: Implications for cognition, psychosis, and addiction. Biological Psychiatry 57(6):594–608, 2005.

Addington J, Duchak V: Reasons for substance use in schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 96(5):329–333, 1997.

Brunette MF, Mueser KT, Xie H, Drake RE: Relationships between symptoms of schizophrenia and substance abuse. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 185(1):13–20, 1997.

Fowler IL, Carr VJ, Carter NT, Lewin TJ: Patterns of current and lifetime substance use in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 24(3):443–455, 1998.

Goswami S, Mattoo SK, Basu D, Singh G: Substance‐abusing schizophrenics: Do they self‐medicate? The American Journal on Addictions 13(2):139–150, 2004.

Schnell T, Koethe D, Krasnianski A, Gairing S, Schnell K, Daumann J, Gouzoulis-Mayfrank E. Ziprasidone versus clozapine in the treatment of dually diagnosed (DD) patients with schizophrenia and cannabis use disorders: A randomized study. American Journal on Addictions 23(3):308–312, 2014.

Baker AL, Hides L, Lubman DI: Treatment of cannabis use among people with psychotic or depressive disorders: A systematic review. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 71(3):247–254, 2010.

Makkos Z, Fejes L, Inczédy-Farkas G, Kassai-Farkas A, Faludi G, Lazary J: Psychopharmacological comparison of schizophrenia spectrum disorder with and without cannabis dependency. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology & Biological Psychiatry 35(1):212–217, 2011. doi:10.1016/j.pnpbp.2010.11.007.

Dervaux A, Laqueille X, Bourdel MC, Leborgne MH, Olié JP, Lôo H, Krebs MO: [Cannabis and schizophrenia: demographic and clinical correlates]. Encephale 29(1):11–17, 2003.

Andreasen NC, Pressler M, Nopoulos P, Miller D, Ho BC: Antipsychotic dose equivalents and dose-years: A standardized method for comparing exposure to different drugs. Biol Psychiatry 67(3):255–262, 2010.

Paul BP, Mell LD, Mitchell JM, McKinley RM: Detection and quantification of 11-nor-delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol-9-carboxylic acid, A metabolite of tetrahydrocannabinol, by capillary gas chromatography and electron impact mass spectrometry. Journal of Analytical Toxicology 11:1–5, 1987.

Di Forti M, Marconi A, Carra E, Fraietta S, Trotta A, Bonomo M, Bianconi F, Gardner-Sood P, O’Connor J, Russo M, Stilo SA, Marques TR, Mondelli V, Dazzan P, Pariante C, David AS, Gaughran F, Atakan Z, Iyegbe C, Powell J, Morgan C, Lynskey M, Murray RM: Proportion of patients in south London with first-episode psychosis attributable to use of high potency cannabis: A case-control study. Lancet Psychiatry 2(3):233–238, 2015.

Power R, Verweij K, Zuhair M, et al: Genetic predisposition to schizophrenia associated with increased use of cannabis. Molecular Psychiatry 19:1201–1204, 2014.

Giordano GN, Ohlsson H, Sundquist K, Sundquist J, Kendler K: The association between cannabis abuse and subsequent schizophrenia: A Swedish national co-relative control study. Psychological Medicine 45:407–414, 2015.

Volk DW, Lewis DA: The role of endocannabinoid signaling in cortical inhibitory neuron dysfunction in schizophrenia. Biological Psychiatry, 2015. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2015.06.015.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

This study was retrospective in nature and for this type of study formal consent is not required. All the participants were de-identified and only aggregated data was used to analyze and report results.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Babatope, T., Chotalia, J., Elkhatib, R. et al. A Study of the Impact of Cannabis on Doses of Discharge Antipsychotic Medication in Individuals with Schizophrenia or Schizoaffective Disorder. Psychiatr Q 87, 729–737 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11126-016-9426-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11126-016-9426-2