Abstract

Rates of parental incarceration in the USA have increased dramatically over the past four decades. The Adverse Childhood Experiences study identified parental incarceration as one of several risk factors related to multiple health outcomes during childhood and adulthood. Parents and other caregivers are widely regarded as sources of resilience for children experiencing adversity, yet few studies have examined caregivers’ parenting practices as sources of resilience for children with incarcerated parents. This study used secondary data from a longitudinal randomized controlled trial of the prison-based parent management training program Parenting Inside Out (PIO). Specifically, it included 149 caregivers (i.e., the non-incarcerated parent, extended family member, or other adult who provides the day-to-day caretaking of a child during parental incarceration) of children aged 2–14 years whose incarcerated parents were randomly assigned to receive PIO or the control condition. Path analysis was used to examine associations between caregivers’ parenting, social support, self-efficacy, and change in child internalizing and externalizing symptoms across a 6-month period. Direct effects of caregivers’ parenting were found on improvements in child behavioral health from baseline (conducted when the parent was incarcerated) to the 6-month follow-up (conducted after most parents had been released). Indirect effects were found for caregiver social support and self-efficacy. The findings highlight the importance of caregivers’ adaptive parenting as a protective resource for children who experience parental incarceration and have implications for the design of preventive interventions for this underserved population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Millions of people in the USA have experienced the incarceration of one or more of their parents (Annie E. Casey Foundation, 2020), including about 1.5 million children who currently have an incarcerated parent (Maruschak et al., 2021). Rates of parental incarceration have increased dramatically over the past four decades (National Research Council, 2014; Sykes & Pettit, 2014). Parental incarceration disproportionately affects Black/African American, Native American, and Latinx children, compared to racial/ethnic majority children (Glaze & Maruschak, 2010; Khan et al., 2018; Kjellstrand & Eddy, 2011b; Sykes & Pettit, 2014; Turanovic et al., 2012).

Effects of Parental Incarceration on Children

The seminal CDC-Kaiser Permanente Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) study identified parental incarceration as one of seven risk factors with strong and cumulative impacts on multiple health outcomes through adulthood (Felitti et al., 1998). In that sample, there was a high correlation between parental incarceration and all other ACEs, with 86% of children with incarcerated parents exposed to at least one other ACE. More recently, in the 2016 National Survey of Children’s Health, children with incarcerated parents were found to be exposed to five times the number of ACEs as children without parental incarceration (Turney, 2018). Research is still quite limited, but, in several studies, parental incarceration is associated with an increased risk of a mental health diagnosis, including depression, anxiety, conduct problems, and substance use disorders, as well as suicidal ideation and attempts, and other negative psychosocial outcomes (Davis & Shlafer, 2017; Gifford et al., 2019; Khan et al., 2018; Rhodes et al., under review).

Theoretical Explanations of the Linkages Between Parental Incarceration and Child Behavioral Health Outcomes

Wildeman and colleagues (2018) point to selection, strain and stress, and stigma in explaining the linkage between parental incarceration and risk for child behavioral health outcomes. With respect to selection, prior to and following parental arrest, children with incarcerated parents are more likely to experience economic hardship, family instability, and conflict (Aaron & Dallaire, 2010; Felitti et al., 1998; Murray et al., 2012; Troy et al., 2018). In terms of strain and stress, parental separation in any form has been recognized as a traumatic event that places children at an extreme disadvantage in key developmental outcomes (Bisnaire et al., 1990; McCutcheon et al., 2018; Murray & Farrington, 2005). Children with incarcerated parents may also be exposed to trauma as a result of witnessing the parent’s crime or arrest process (Tasca et al., 2016). Across a variety of studies, high rates of substance use have been reported among incarcerated parents (e.g., 87 to 93%), which may confer risk to children through exposure to stress or modeling of substance use behaviors (Aaron & Dallaire, 2010; Kjellstrand et al., 2012; Shorey et al., 2013).

With respect to stigma, as compared to other causes of parental separation (e.g., parental death, divorce, or military deployment), parental incarceration is often described as “ambiguous loss,” in which children are deprived of an outpouring of community support common for other types of parental loss/separation (Arditti, 2012; Bocknek et al., 2009; Phillips & Gates, 2011). The stigma associated with parental incarceration transfers to children and other family members by nature of association, and often results in their attempts to conceal the incarceration, which reduces opportunities for social support and help-seeking (Phillips & Gates, 2011). Moreover, children’s internalization of stigma can yield feelings of shame, which may lead to engagement in risky behaviors (Murray et al., 2012; Phillips & Gates, 2011).

Families as a Source of Resilience

Selection, strain and stress, and stigma can place children at immediate and long-term risk for negative behavioral health outcomes (Fagan et al., 2014; Fosco & Feinberg, 2018; McCutcheon et al., 2018; Murray & Farrington, 2005; National Research Council, 2014; Shorey et al., 2013; Zimmerman & Kushner, 2017). Nonetheless, there is considerable heterogeneity in the outcomes of children with incarcerated parents (Arditti & Johnson, 2022; Turney & Wildeman, 2015). Calls have been made in support of research agendas focused on the factors that promote resilience for children experiencing parental incarceration, with a specific emphasis on family processes that can explain this heterogeneity (e.g., Arditti & Johnson, 2022; Poehlmann-Tynan & Eddy, 2019).

Parents and other caregivers are widely regarded as key sources of resilience for children experiencing various forms of adversity (Masten, 2001). A recent paper by Arditti and Johnson (2022) highlighted the utility of a “family resilience perspective” in understanding the developmental outcomes of children with incarcerated parents. The family resilience framework emphasizes the key role of relational functioning within families in protecting against adverse effects of environmental risk factors (Hadfield & Ungar, 2018; Walsh, 2003). In the context of parental incarceration and associated risk factors, such as family instability and financial hardship, adaptive parenting on the part of children’s caregivers (i.e., the non-incarcerated parents, extended family members, or others who provide the day-to-day caretaking role of children during the incarceration) is likely to support positive development by creating a nurturing proximal environment (Arditti & Johnson, 2022).

A cluster of adaptive parenting practices (i.e., positive relationship quality and effective discipline) has been show to prevent negative behavioral health outcomes for children across populations and contexts (e.g., Barrera et al., 2001; Eddy & Chamberlain, 2000; Fulkerson et al., 2008; Knutson et al., 2004; Mackintosh et al., 2006; O’Connell et al., 2009; Skinner et al., 2009; Tragesser et al., 2007). While research on the association between parenting and adjustment in the context of parental incarceration has been limited, there is some evidence that positive parent–child relationships can mitigate the negative impact of parental incarceration. Davis and Shlafer (2017), for example, found that close relationships with caregivers (i.e., parents or other primary caregivers) buffered the risk for elevated behavioral health concerns among adolescents who had previously or ever had a parent who was incarcerated. Parent–child closeness has also been found to predict flourishing for youth with a history of parental incarceration (Boch & Ford, 2021). Caregivers’ warmth has been concurrently linked with lower internalizing and externalizing symptoms for children with incarcerated mothers (Mackintosh et al., 2006). Morgan and colleagues (2021) found that praising good behavior, an element of effective discipline, was positively associated with child adjustment in the school setting. Unfortunately, studies that include both relationship and discipline aspects of parenting are rare in the context of research on children with incarcerated parents. In a notable exception, in a community-based sample drawn when children were in elementary school and then who were followed into young adulthood, Kjellstrand and Eddy (2011a) found that a latent construct of adaptive parenting, including multiple dimensions of relationship quality (i.e., involvement and quality of the parent–child relationship) and effective discipline (i.e., monitoring, praise, inappropriate discipline, and inconsistent discipline) mediated the relation between parental incarceration externalizing at 5th, 8th, and 10th grades, and delinquent behavior in 10th grade. Approximately 10% of youth in that study had experienced the incarceration of their parent.

Resources for Caregiver Engagement in Adaptive Parenting

For a majority of families affected by parental incarceration, children live with a primary caregiver who is either the non-incarcerated parent (84%) or another relative (21%), with only a small minority (3%) in foster care (Glaze & Maruschak, 2010). The Family Resilience Framework points to factors that affect caregivers’ ability to engage in adaptive parenting practices (Arditti & Johnson, 2022). Caregivers commonly report financial challenges, unsafe living conditions, difficult interactions with the incarcerated parent, limited time, and limited parenting or emotional support (Mackintosh et al., 2006; Tasca et al., 2014; Turanovic et al., 2012; Turney & Wildeman, 2013). Many caregivers also have a history of trauma themselves (Narayan et al., 2021). These stressors can serve as barriers to the use of adaptive parenting practices (Kjellstrand & Eddy, 2011a, b; Poehlmann, 2005; Wakefield, 2014). For example, caregivers who experience higher levels of parenting stress are less likely to engage in warm and accepting parenting (Mackintosh et al., 2006). Problematically, caregivers are denied access to resources available to formal foster care parents, including financial assistance and respite care, and stigma can deter access to formal or informal support (Phillips & Gates, 2011).

These findings point to the need to study factors associated with resilience for the caregiver, as well as for the child. Previous research with other minoritized populations (e.g., Izzo et al., 2000; Raikes & Thompson, 2005) suggests caregivers’ social support and parenting self-efficacy may increase resilience among caregivers and provide resources for their use of adaptive parenting strategies (Arditti, 2016). Given the frame of parental incarceration as an “ambiguous loss,” with little to no outpouring of support for the family, caregivers’ access to social support, including both emotional and tangible support, is likely to be critically important. Morgan and colleagues (2021) tested caregivers’ social support as a mediator of material hardship and child adjustment in school. Social support was not found to have a direct influence on child adjustment in that study, but there may be an indirect association between social support and child outcomes through the influence on adaptive parenting. In addition, there is extensive research on the link between parenting self-efficacy and adaptive parenting practices in other populations (Jones & Prinz, 2005). However, research has been limited for families experiencing incarceration and primarily centers on the self-efficacy and practices of the incarcerated parent, rather than the caregiver (e.g., Grella & Greenwell, 2006; Tremblay & Sutherland, 2017).

The Current Study

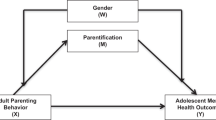

To assess caregiver-based sources of resilience for children with an incarcerated parent, we used secondary data from the Parent Child Study, a randomized controlled trial of the Parenting Inside Out (PIO) program (Eddy et al., 2008). PIO is an adaptation of cognitive-behavioral parent management training designed to promote adaptive parenting skills by incarcerated parents. We hypothesized that for children experiencing parental incarceration, caregivers’ adaptive parenting skills at baseline, when parents were incarcerated, would predict improvements in child behavioral health (internalizing and externalizing) symptoms across a 6-month period, at which point most parents had been released back into their communities (see Fig. 1). In addition, we hypothesized that caregivers’ reports of social support and parenting self-efficacy would be associated with higher levels of adaptive parenting and have positive indirect associations with improvements in child behavioral health.

Methods

Design

The Parent Child Study was conducted within four minimum and medium security level adult correctional facilities (i.e., one for women, three for men) operated at the time as “releasing” institutions by the Oregon Department of Corrections (DOC). Parents were recruited from all DOC facilities in the state and had to meet the following requirements to be eligible: (1) had at least one child between the ages of 3 and 11 years old, (2) have the legal right to contact their child, (3) had some role in parenting their child(ren) in the past and expected some such role in the future, (4) had not committed either a crime against a child or any type of sex offense, (5) had contact information for the caregiver of at least one of his/her young children, and (6) had less than 9 months remaining before the end of their prison sentence. For eligible potential participants who consented to participate, but who did not currently reside in one of the study facilities, a request was made to the DOC for their transfer to a study facility. Most such requests were granted.

Once residing at a study facility and after the initial baseline assessment, incarcerated parents were randomized to experimental condition (i.e., intervention or control) within institution, blocking by race and ethnicity, prior to the launch of each new series of intervention sessions. Participants assigned to the intervention condition were offered the PIO program, a 36-session cognitive-behavioral parent management training (PMT) program (Reid et al., 2002) adapted across a 3-year period of development and refinement for and with incarcerated parents (Eddy et al., 2008). The program focused on traditional PMT topics such as communication skills, positive reinforcement and involvement, monitoring, discipline, and problem-solving. In addition, it included contextually specific content for families affected by parental incarceration recommended during focus groups and interviews with incarcerated parents, caregivers, and parent educators who work with incarcerated parents around the USA (e.g., child development, child health and safety, and personal and family decision-making). The program was delivered through brief presentations, video clips, role plays, large and small group discussions, and class projects conducted both inside and outside of sessions. Sessions were 2.5 h long and held three times per week across a 3-month period.

Caregivers were not directly involved in the intervention, but upon request by the incarcerated parent, intervention materials (i.e., handouts that incarcerated parents received during sessions) were sent to caregivers via US mail, and parents were encouraged to discuss them with the caregiver either via phone and/or during in-person visits. Participants assigned to the control group were not allowed to enroll in PIO, but as with participants in the intervention condition, were allowed to access all other psychosocial services that they were eligible to receive, including other parent education programs. Of note, there were few other parenting programs per se available during the course of the study in the participating institutions, and those that were available were typically designed by the person who was delivering them, were not evidence-informed, and served only a small number of parents (see Eddy et al., 2008).

After incarcerated parents enrolled in the study, attempts were made to contact the caregivers of their children and invite both caregivers and children to participate in study interviews. Both incarcerated parent participants and caregiver participants were assessed at multiple points. Analyses here focus on information collected at two points: during the baseline assessment while incarcerated parents were in prison, and at a 6-month follow-up, when most parents had been released. Data were collected via in-person interviews. Participants were compensated for their time in participating in each assessment; for incarcerated parents, amounts were $30 for in-prison interviews and $100 for out-of-prison interviews, and for caregivers, $100 for each interview. Additional information about the study is available in Eddy et al. (2013) and Eddy et al. (2022).

Sample

Participants of interest in the present analyses are the primary caregivers of children with incarcerated parents. These 149 adults represent a subsample of the families of the 359 incarcerated parents enrolled in the Parent Child Study. Recruitment of caregivers was challenging due to the following circumstances. Despite obtaining contact information (i.e., addresses, phone numbers) for caregivers from all incarcerated parents enrolled in the study, this information was not always correct, and when it was, many caregivers did not answer our queries despite repeated attempts at contact. Eventually, 203 (56% of the full sample) caregivers were reached, and 149 (73% of those reached) consented to participate. The reasons for active decline varied, with the most common reasons being too busy to participate, not interested in the study, and/or no desire to be associated with the incarcerated parent in any way (even though the requirements of caregiver participation in the study did not require any contact). The incarcerated parents connected to the caregiver subsample were evenly split between the intervention condition (49%) and the control condition (51%).

Demographic characteristics for the full sample are available in Kjellstrand et al. (2012). Of note, there were no significant differences between the full study sample and the caregiver subsample on caregiver, child, or incarcerated parent race/ethnicity, nor on child or incarcerated parent gender. However, there were significant differences between the full sample and the caregiver subsample based on caregiver demographics/role. For example, male caregivers and biological fathers were less likely to participate. Biological grandparents were more likely to participate. Caregivers who were former spouses of the incarcerated parent were less likely to participate whereas caregivers who were the biological mother, mother-in-law, or unmarried female romantic partner of the incarcerated parent were more likely to participate.

Caregiver self-reported gender included 85% women and 13% men. Self-reported race/ethnicity was 57% non-Latino White, 7% multiracial, 5% Black/African American, 4% Native American, 4% Latino, and < 1% Asian/Pacific Islander. Data were missing for 2% on gender and 23% on race/ethnicity. Caregivers were related to the children in their care in a variety of ways, including biological mother (36%), biological grandparent (40%), biological father (7%), biological aunt/uncle (5%), stepparent/grandparent (3%), and non-relative caregivers (3%). Most caregivers reported they were either the incarcerated parents’ mother (28%) or current or ex-romantic partner (current married, 12%; current unmarried, 11%; former never married, 7%). Caregiver-child relationship data were missing for 5% of caregivers, and caregiver-incarcerated parent relationship data were missing for 12%. Only one child was the focus of this study; if there was more than one child in that age range, the primary child of focus was randomly chosen. Race/ethnicity of the children was reported by incarcerated parents as 59% non-Latino White, 9% Black/African American, 19% multiracial, 6% Native American, and 7% Latino. Children were 8 years old on average (SD = 2.7, range = 2–14; 50% boys and 48% girls; 2% missing).

Demographics for the incarcerated parents connected to these caregivers were as follows. Self-reported gender was 51% women and 46% men; self-reported race/ethnicity was 58% non-Latino White, 14% Black/African American, 10% Native American, 8% multiracial, and 7% Hispanic or Latino. Data were missing for 3% on gender and 3% on race/ethnicity. A majority (84%) had been released from prison and were living in the community when the 6-month post-release assessment was conducted. During the follow-up period, just over half of the children’s previously incarcerated parents returned to live with them either full time (42.7%) or part time (9.1%). The child’s contact with the parent at follow-up was missing for 26% (n = 39).

Measures

Caregivers’ Adaptive Parenting

As part of a baseline interview, caregivers responded to items regarding their parenting of the child with an incarcerated parent, developed by Kjellstrand and Eddy (2011a) for a prior study. Items spanned across six dimensions of parenting, including relationship quality (2 items rated on a 5-point scale from 1 [not well at all] to 5 [very well]; e.g., “how well do you and the child get along?”), monitoring (8 items rated on a 5-point scale from 1 [always true] to 5 [always false]; e.g., “during a typical weekend day, how much of the time do you know where the child is?”), involvement (4 items rated on a 5-point scale from 1 [never] to 5 [every day]; e.g., “how often do you talk with child about what they do with friends?”), inappropriate discipline (4 items assessing different discipline behaviors [e.g., physical punishment] rated on a dichotomous scale of 0 [no] and 1 [yes]; e.g., “what do you do if the child won’t listen or obey?”), inconsistent discipline (2 items rated on a 5-point scale from 1 [never] to 5 [always]; e.g., “how often does the child get around the rules you set for them?”), and effective discipline (2 items rated on a 5-point scale from 1 [never] to 5 [always or almost always]; e.g., “how often do you feel the discipline you use improves the child’s behavior?”). Items were standardized and mean scored within the six dimensions of parenting. We conducted preliminary work to create a latent variable that would represent caregiver adaptive parenting. We used confirmatory factor analysis to test a series of models and determine the best factor structure, determined by good fit to the data and significant factor loadings. Our final model comprised five subscales (relationship quality, monitoring, inappropriate discipline, inconsistent discipline, and effective discipline) that loaded on one latent factor (adaptive parenting). Based on prior literature on parenting, we considered separating the factor into two related constructs of discipline and relationship quality, but they were so highly correlated (r = 0.76) that we did not believe these factors had sufficient discriminant validity. The model fit the data well: χ2 = 6.742, p < 0.001, RMSEA = 0.048 (0.000; 0.131), CFI = 0.991, SRMR = 0.033. We saved a factor score to represent caregiver adaptive parenting in the structural path models. This approach facilitates convergence, which can be a problem for studies with smaller sample sizes.

Caregiver Social Support

At baseline, caregivers completed the 19-item Social Support Survey (Sherbourne & Stewart, 1991), which contains four dimensions of social support: emotional/informational support (8 items, α = 0.96, i.e., “someone you can count on to listen to you when you need to talk”), tangible support (4 items, α = 0.90; i.e., “someone to take you to the doctor”), affectionate support (3 items, α = 0.92; i.e., “someone who hugs you”), and positive social interaction support (3 items, α = 0.95; i.e., “someone to do something enjoyable with”). Items were mean scored to create an overall index (19 items, α = 0.98).

Caregiver Parenting Self-efficacy

At baseline, caregivers completed the 8-item Self-Efficacy and Parenting Scale, which comprised questions about perceptions of themselves as parents, such as “in general how good of a parent do you feel you are?” and “when your child is upset, sad, or crying, how good are you at soothing her/him?” Items were mean scored to create an overall index (8 items, α = 0.81).

Child Internalizing and Externalizing Problems

At baseline and at 6 months, caregivers completed the 112-item Child Behavior Checklist (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001). This study used the Withdrawn, Somatic Complaints, and Anxiety/Depressed Problems subscales to create an internalizing construct (32 items; α = 0.88, i.e., “worries,” “cries a lot”) and Delinquent and Aggressive Behaviors subscales to create an externalizing construct (35 items; α = 0.92, i.e., “argues a lot,” “gets in fights”). Items were mean scored to create internalizing and externalizing scores.

Child Contact with the Formerly Incarcerated Parent

At the 6-month assessment, incarcerated parents reported on their contact with their child. Response options rated on an ordinal scale included living with child full time, living with child part time, visiting child more than one time per week, visiting child once per week or less, or phone or email contact only.

Analytic Approach

Study hypotheses were tested using structural equation modeling in Mplus (Muthén & Muthén, 2020). Full information maximum likelihood (FIML) procedures were used to address missing data (Enders & Bandalos, 2001). Multiple fit indices were examined to evaluate the adequacy of model fit, including a non-significant χ2 or a combination of SRMR ≤ 0.08, RMSEA ≤ 0.08, and/or CFI ≥ 0.90 (Hu & Bentler, 1999). Standardized regression coefficients (βs) were used to assess the strength of the hypothesized relations between caregiver parenting, self-efficacy, social support, and child behavioral health, controlling for baseline. We controlled for random assignment of the incarcerated parents to condition, as well as the degree of contact between the child and incarcerated parent at follow-up. Baseline variables were allowed to covary. We used bias-corrected bootstrap confidence intervals to assess the significance of the standardized indirect effects, as specified in Fig. 1. Mediation was considered significant if the 95% CIs did not cross zero (Fritz & MacKinnon, 2007; MacKinnon et al., 2002; Taylor et al., 2008).

Results

Descriptives

Table 1 displays descriptive statistics and correlations among all study variables. At baseline, correlations between caregiver social support, parenting self-efficacy, and adaptive parenting were positive and significant. These three variables were negatively correlated with child internalizing and externalizing at baseline and the 6-month follow-up. The control variables, intervention condition and contact between the child and the (formerly) incarcerated parent, were not related to any of the other study variables.

Test of the Hypothesized Model

The non-significant χ2 suggested concordance between the hypothesized model and the data: χ2(8) = 5.40, p = 0.71. Standardized βs supported the significance of the hypothesized effects (see Fig. 2). Caregiver adaptive parenting predicted a significant decrease in children’s externalizing problems and internalizing problems from baseline to the 6-month follow-up. Social support and parenting self-efficacy were positively associated with parenting at baseline. Social support and parenting self-efficacy did not directly predict improvements in externalizing or internalizing. However, significant indirect effects were found in the association between social support and child externalizing (β = − 0.047, 95%CI = − 0.113; − 0.002) and internalizing problems (β = − 0.060, 95%CI = − 0.143; − 0.010) through adaptive parenting. The indirect effects from parenting efficacy to child externalizing problems (β = − 0.108, 95%CI = − 0.246; − 0.008) and internalizing problems (β = − 0.138, 95%CI = − 0.284; − 0.049) through adaptive parenting were also significant. The model accounted for a significant amount of the variance for caregivers’ parenting (R2 = 0.31), children’s internalizing (R2 = 0.54), and children’s externalizing (R2 = 0.53).

Discussion

Given the growing number of children exposed to parental incarceration in the USA, and the potential for lasting effects of parenting incarceration on multiple indices of child health throughout their life course, research is needed to find effective ways to prevent the negative consequences of this particular ACE. The Family Resilience Framework highlights the important role of caregivers in promoting the behavioral health and well-being of children with incarcerated parents (Arditti & Johnson, 2022). A cluster of adaptive parenting practices, including relationship quality and effective discipline, has been shown to promote child health across populations and contexts. The results of this study support the linkage between caregivers’ use of adaptive parenting and child behavioral health outcomes. Such a finding contributes to the literature on parenting in families affected by incarceration, which has largely focused on the incarcerated parent and aspects associated with warmth and support, to the exclusion of everyday caregivers and positive discipline strategies (see Kjellstrand & Eddy, 2011a, for an exception).

This study overcomes the methodological challenges of much of the previous research, which has made use of large statewide or national datasets that were not designed for studying resilience mechanisms in families affected by incarceration (Arditti & Johnson, 2022). For example, national datasets often use a cross-sectional design and assess parental incarceration via a single item as to whether the child has ever had a parent incarcerated and for any length of time. This creates three challenges. First, it precludes an understanding of the impact of various aspects of time (e.g., child age when the incarceration began, length of the incarceration, time since incarceration) on child outcomes. Second, it is unclear whether the parenting practices assessed were implemented by the incarcerated parent or another caregiver. Third, it is unclear as to whether parenting practices influence child outcomes or whether parents/caregivers are responding to children’s behaviors, which may be influenced by previous traumatic experiences. This study attempts to overcome these challenges in that (1) all children in the study had an incarcerated parent at baseline, (2) the parenting practices assessed are specifically attributed to the caregivers while the parent was incarcerated, and (3) we controlled for child outcomes at baseline to model the prospective association between parenting and change in child outcomes over time. The results of this study have clear implications for the importance of caregivers’ parenting while a parent is incarcerated; yet, to date, there are no “evidence-based” preventive interventions that have been specifically designed to address the needs of caregivers.

A second contribution of this study relates to the assessment of resources for caregivers’ parenting. Caregivers of children with incarcerated parents face disproportionate challenges to their parenting (Arditti & Johnson, 2022; Kjellstrand & Eddy, 2011b; Mackintosh et al., 2006; Poehlmann, 2005; Wakefield, 2014). Many caregivers experience stressors prior to the incarceration (e.g., poverty, history of ACEs), which are further compounded by losses at the time of incarceration, including financial, emotional, and/or parenting support (Mackintosh et al., 2006; Tasca et al., 2014; Turanovic et al., 2012). Furthermore, social stigma may prevent families from accessing various formal or informal supports (Phillips & Gates, 2011). Given these unique challenges, social support and parenting self-efficacy may bolster the use of adaptive parenting by caregivers (Arditti, 2016). To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the direct and indirect effects of social support and parenting self-efficacy for caregivers of children with incarcerated parents. As hypothesized, these had positive direct associations with parenting and had indirect effects on improvement in child behavioral health over time. As such, preventive interventions focused on caregivers’ parenting should be designed to promote self-efficacy and social support.

This study was not specifically focused on the parent who had been incarcerated or the effects of the PIO program. However, given the fact that data were collected as part of a randomized trial, we felt that it was necessary to control for the parents’ random assignment to the study condition, as well as contact between the parent and child, to clearly demonstrate the effects of caregivers’ parenting on child outcomes. Previous analyses with these data found significant effects of PIO on parent stress and depression, parent–child relationships (Eddy et al., 2013), as well as post-release parental substance use and rearrest rates (Eddy et al., 2022), indicating the potential of parenting interventions to improve predictors of adolescent substance use in this highly stressed population. While these effects are promising, a review of programs for incarcerated parents suggests the lack of contact between incarcerated parents and children is a major barrier to program effects on child outcomes (Troy et al., 2018). A core component of many parenting programs is home practice of program skills with children between sessions (Berkel et al., 2018; Kaminski et al., 2008). Without the ability to regularly practice parenting skills, these skills are less likely to be routinized parts of family life and children receive a limited dose of the protective influence of parenting. It may be the case that the effects of intervening with parents would emerge over time; however, offering support to caregivers, who have day-to-day opportunities to practice skills with children, may have a more immediate robust impact on child outcomes. Nonetheless, nearly all parenting programs designed to address parental incarceration have focused on the incarcerated parent, rather than the caregiver (Troy et al., 2018).

Limitations

This study has a few noteworthy limitations. First and foremost was the fact that of the 359 incarcerated parents in the RCT, only 203 caregivers were successfully contacted, and only 149 caregivers were ultimately willing to participate. Due to the limited information available, we are unable to determine whether there may be contextual differences between the caregivers who were willing to participate and those who were not. It is possible, for example, that caregivers with limited or conflictual relations with the incarcerated parent were less likely to agree to participate. Furthermore, with only two waves of data, we were unable to test full mediation between social support and parenting self-efficacy and child behavioral health outcomes. Nonetheless, the lack of direct association between these variables provides support for the hypothesized model. Finally, common method bias may be present as all data were obtained via caregiver report. Despite these challenges, given the limited research that has been conducted with children who have incarcerated parents, this study contributes to our very limited understanding of the factors that promote resilience for this population.

Conclusions

This study demonstrated the importance of caregivers’ adaptive parenting as a protective resource for children who experience parental incarceration. Given that many caregivers experience ACEs themselves, and the loss of emotional and coparenting support due to the incarceration of the child’s parent, social support and parenting efficacy may bolster the use of adaptive parenting practices. To the best of our knowledge, to date, no evidence-based programs exist that were explicitly developed to meet the unique needs of the caregivers involved in the day-to-day caregiving while a parent is incarcerated. These results support the utmost importance of focusing on improving adaptive parenting, as well as on social supporting and parenting self-efficacy, when designing such a program.

Data Availability

The de-identified data that support the findings of this study may be made available from the trial PI (JME), upon reasonable request.

References

Aaron, L., & Dallaire, D. H. (2010). Parental incarceration and multiple risk experiences: Effects on family dynamics and children’s delinquency. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 39(12), 1471–1484.

Achenbach, T. M., & Rescorla, L. A. (2001). Manual for the ASEBA school-age forms & profiles.

Annie E. Casey Foundation. (2020). Kids Count Data Center. https://datacenter.kidscount.org/data#AZ/2/0/char/0

Arditti, J. A. (2012). Child trauma within the context of parental incarceration: A family process perspective. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 4(3), 181–219.

Arditti, J. A. (2016). A family stress-proximal process model for understanding the effects of parental incarceration on children and their families. Couple and Family Psychology, 5(2), 65–88.

Arditti, J. A., & Johnson, E. I. (2022). A family resilience agenda for understanding and responding to parental incarceration. American Psychologist, 77(1), 56–70.

Barrera, M., Jr., Biglan, A., Ary, D., & Li, F. (2001). Replication of a problem behavior model with American Indian, Hispanic, and Caucasian youth. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 21(2), 133–157.

Berkel, C., Sandler, I. N., Wolchik, S. A., Brown, C. H., Gallo, C. G., Chiapa, A., Mauricio, A. M., & Jones, S. (2018). “Home practice is the program:” Parents’ practice of program skills as predictors of outcomes in the New Beginnings Program effectiveness trial. Prevention Science, 19(5), 663–673.

Bisnaire, L. M., Firestone, P., & Rynard, D. (1990). Factors associated with academic achievement in children following parental separation. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 60(1), 67–76.

Boch, S. J., & Ford, J. L. (2021). Protective factors to promote health and flourishing in Black youth exposed to parental incarceration. Nursing Research, 70(5S Suppl 1), S63–s72.

Bocknek, E. L., Sanderson, J., & Britner, P. A. (2009). Ambiguous loss and posttraumatic stress in school-age children of prisoners. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 18(3), 323–333.

Davis, L., & Shlafer, R. J. (2017). Mental health of adolescents with currently and formerly incarcerated parents. Journal of Adolescence, 54, 120–134.

Eddy, J. M., & Chamberlain, P. (2000). Family management and deviant peer association as mediators of the impact of treatment condition on youth antisocial behavior. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68(5), 857.

Eddy, J. M., Martinez, C. R., & Burraston, B. (2013). Relationship processes and resilience in children with incarcerated parents: VI. A randomized controlled trial of a parent management training program for incarcerated parents: Proximal impacts. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 78(3), 75–93.

Eddy, J. M., Martinez, C. R., Burraston, B. O., Herrera, D., & Newton, R. (2022). A randomized controlled trial of a parent management training program for incarcerated parents: Post-release outcomes. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(8), 4605.

Eddy, J. M., Martinez, C. R., Schiffmann, T., Newton, R., Olin, L., Leve, L., Foney, D. M., & Shortt, J. W. (2008). Development of a multisystemic parent management training intervention for incarcerated parents, their children and families. Clinical Psychologist, 12(3), 86–98.

Enders, C. K., & Bandalos, D. L. (2001). The relative performance of full information maximum likelihood estimation for missing data in structural equation models. Structural Equation Modeling, 8(3), 430–457.

Fagan, A. A., Wright, E. M., & Pinchevsky, G. M. (2014). The protective effects of neighborhood collective efficacy on adolescent substance use and violence following exposure to violence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 43(9), 1498–1512.

Felitti, V. J., Anda, R. F., Nordenberg, D., Williamson, D. F., Spitz, A. M., Edwards, V., Koss, M. P., & Marks, J. S. (1998). Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The adverse childhood experiences (ACE) study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 14(4), 245–258.

Fosco, G. M., & Feinberg, M. E. (2018). Interparental conflict and long-term adolescent substance use trajectories: The role of adolescent threat appraisals. Journal of Family Psychology, 32(2), 175–185.

Fritz, M. S., & MacKinnon, D. P. (2007). Required sample size to detect the mediated effect. Psychological Science, 18(3), 233–239.

Fulkerson, J. A., Pasch, K. E., Perry, C. L., & Komro, K. (2008). Relationships between alcohol-related informal social control, parental monitoring and adolescent problem behaviors among racially diverse urban youth. Journal of Community Health, 33(6), 425–433.

Gifford, E. J., Eldred Kozecke, L., Golonka, M., Hill, S. N., Costello, E. J., Shanahan, L., & Copeland, W. E. (2019). Association of parental incarceration with psychiatric and functional outcomes of young adults. JAMA Network Open, 2(8), e1910005–e1910005.

Glaze, L. E., & Maruschak, L. M. (2010). Parents in prison and their minor children (Rev. 1, 198, 2009. ed.). U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs.

Grella, C. E., & Greenwell, L. (2006). Correlates of parental status and attitudes toward parenting among substance-abusing women offenders. The Prison Journal, 86(1), 89–113.

Hadfield, K., & Ungar, M. (2018). Family resilience: Emerging trends in theory and practice. Journal of Family Social Work, 21(2), 81–84.

Hu, L.-T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6(1), 1–55.

Izzo, C., Weiss, L., Shanahan, T., & Rodriguez-Brown, F. (2000). Parental self-efficacy and social support as predictors of parenting practices and children’s socioemotional adjustment in Mexican immigrant families. Journal of Prevention & Intervention in the Community, 20(1–2), 197–213.

Jones, T. L., & Prinz, R. J. (2005). Potential roles of parental self-efficacy in parent and child adjustment: A review. Clinical Psychology Review, 25(3), 341–363.

Kaminski, J. W., Valle, L. A., Filene, J. H., & Boyle, C. L. (2008). A meta-analytic review of components associated with parent training program effectiveness. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 36(4), 567–589.

Khan, M. R., Scheidell, J. D., Rosen, D. L., Geller, A., & Brotman, L. M. (2018). Early age at childhood parental incarceration and STI/HIV-related drug use and sex risk across the young adult lifecourse in the US: Heightened vulnerability of Black and Hispanic youth. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 183, 231–239.

Kjellstrand, J. M., Cearley, J., Eddy, J. M., Foney, D., & Martinez, C. R. (2012). Characteristics of incarcerated fathers and mothers: Implications for preventive interventions targeting children and families. Children & Youth Services Review, 34(12), 2409–2415.

Kjellstrand, J. M., & Eddy, J. M. (2011a). Mediators of the effect of parental incarceration on adolescent externalizing behaviors. Journal of Community Psychology, 39(5), 551–565.

Kjellstrand, J. M., & Eddy, J. M. (2011b). Parental incarceration during childhood, family context, and youth problem behavior across adolescence. Journal of Offender Rehabilitation, 50(1), 18–36.

Knutson, J. F., DeGarmo, D. S., & Reid, J. B. (2004). Social disadvantage and neglectful parenting as precursors to the development of antisocial and aggressive child behavior: Testing a theoretical model. Aggressive Behavior, 30(3), 187–205.

MacKinnon, D. P., Lockwood, C. M., Hoffman, J. M., West, S. G., & Sheets, V. (2002). A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychological Methods, 7(1), 83–104.

Mackintosh, V. H., Myers, B. J., & Kennon, S. S. (2006). Children of incarcerated mothers and their caregivers: Factors affecting the quality of their relationship. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 15(5), 579.

Maruschak, L. M., Bronson, J., & Alper, M. (2021). Survey of prison inmates, 2016: Parents in prison and their minor children. https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/pptmcspi16st.pdf

Masten, A. S. (2001). Ordinary magic: Resilience processes in development. American Psychologist, 56(3), 227–238.

McCutcheon, V. V., Agrawal, A., Kuo, S. I. C., Su, J., Dick, D. M., Meyers, J. L., Edenberg, H. J., Nurnberger, J. I., Kramer, J. R., Kuperman, S., Schuckit, M. A., Hesselbrock, V. M., Brooks, A., Porjesz, B., & Bucholz, K. K. (2018). Associations of parental alcohol use disorders and parental separation with offspring initiation of alcohol, cigarette and cannabis use and sexual debut in high-risk families. Addiction, 113(2), 336–345.

Morgan, A. A., Arditti, J. A., Dennison, S., & Frederiksen, S. (2021). Against the odds: A structural equation analysis of family resilience processes during paternal incarceration. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(21), 11592.

Murray, J., & Farrington, D. P. (2005). Parental imprisonment: Effects on boys’ antisocial behaviour and delinquency through the life-course. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 46(12), 1269–1278.

Murray, J., Farrington, D. P., & Sekol, I. (2012). Children’s antisocial behavior, mental health, drug use, and educational performance after parental incarceration: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 138(2), 175–210.

Muthén, B. O., & Muthén, L. K. (2020). Mplus, version 8.4. In Muthén & Muthén.

Narayan, A. J., Lieberman, A. F., & Masten, A. S. (2021). Intergenerational transmission and prevention of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs). Clinical Psychology Review, 85, 101997.

National Research Council. (2014). Consequences for families and children. In The growth of incarceration in the United States: Exploring causes and consequences. The National Academies Press.

O’Connell, M. E., Boat, T., & Warner, K. E. (Eds.). (2009). Preventing mental, emotional, and behavioral disorders among young people: Progress and possibilities. National Academies Press.

Phillips, S. D., & Gates, T. (2011). A conceptual framework for understanding the stigmatization of children of incarcerated parents. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 20(3), 286–294.

Poehlmann-Tynan, J., & Eddy, J. M. (2019). A research and intervention agenda for children with incarcerated parents and their families. In J. M. Eddy & J. Poehlmann-Tynan (Eds.), Handbook on children with incarcerated parents: Research, policy, and practice (pp. 353–371). Springer International Publishing.

Poehlmann, J. (2005). Children’s family environments and intellectual outcomes during maternal incarceration. Journal of Marriage and Family, 67(5), 1275–1285.

Raikes, H. A., & Thompson, R. A. (2005). Efficacy and social support as predictors of parenting stress among families in poverty. Infant Mental Health Journal, 26(3), 177–190.

Reid, J. B., Patterson, G. R., & Snyder, J. (Eds.). (2002). Antisocial behavior in children and adolescents: A developmental analysis and model for intervention. American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/10468-000

Rhodes, C. A., Thomas, N., O’Hara, K. L., Hita, L., Blake, A., Wolchik, S. A., Fisher, B., Freeman, M., Chen, D., & Berkel, C. (under review). Enhancing the focus: How does parental incarceration fit into the overall picture of Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) and Positive Childhood Experiences (PCEs)?

Sherbourne, C. D., & Stewart, A. L. (1991). The MOS social support survey. Social Science & Medicine, 32(6), 705–714.

Shorey, R. C., Fite, P. J., Elkins, S. R., Frissell, K. C., Tortolero, S. R., Stuart, G. L., & Temple, J. R. (2013). The association between problematic parental substance use and adolescent substance use in an ethnically diverse sample of 9th and 10th graders. The Journal of Primary Prevention, 34(6), 381–393.

Skinner, M. L., Haggerty, K. P., & Catalano, R. F. (2009). Parental and peer influences on teen smoking: Are White and Black families different? Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 11(5), 558–563.

Sykes, B. L., & Pettit, B. (2014). Mass incarceration, family complexity, and the reproduction of childhood disadvantage. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 654(1), 127–149.

Tasca, M., Mulvey, P., & Rodriguez, N. (2016). Families coming together in prison: An examination of visitation encounters. Punishment & Society, 18(4), 459–478.

Tasca, M., Turanovic, J. J., White, C., & Rodriguez, N. (2014). Prisoners’ assessments of mental health problems among their children. International Journal of Offender Therapy & Comparative Criminology, 58(2), 154–173.

Taylor, A. B., MacKinnon, D. P., & Tein, J.-Y. (2008). Tests of the three-path mediated effect. Organizational Research Methods, 11(2), 241–269.

Tragesser, S. L., Beauvais, F., Swaim, R. C., Edwards, R. W., & Oetting, E. R. (2007). Parental monitoring, peer drug involvement, and marijuana use across three ethnicities. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 38(6), 670–694.

Tremblay, M. D., & Sutherland, J. E. (2017). The effectiveness of parenting programs for incarcerated mothers: A systematic review. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 26(12), 3247–3265.

Troy, V., McPherson, K. E., Emslie, C., & Gilchrist, E. (2018). The feasibility, appropriateness, meaningfulness, and effectiveness of parenting and family support programs delivered in the criminal justice system: A systematic review. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 27(6), 1732–1747.

Turanovic, J. J., Rodriguez, N., & Pratt, T. C. (2012). The collateral consequences of incarceration revisited: A qualitative analysis of the effects on caregivers of children of incarcerated parents. Criminology, 50(4), 913–959.

Turney, K. (2018). Adverse childhood experiences among children of incarcerated parents. Children and Youth Services Review, 89, 218–225.

Turney, K., & Wildeman, C. (2013). Redefining relationships: Explaining the countervailing consequences of paternal incarceration for parenting. American Sociological Review, 78(6), 949–979.

Turney, K., & Wildeman, C. (2015). Detrimental for some? Heterogeneous effects of maternal incarceration on child wellbeing. Criminology & Public Policy, 14(1), 125–156.

Wakefield, S. (2014). Accentuating the positive or eliminating the negative? Paternal incarceration and caregiver–child relationship quality. Journal of Criminal Law & Criminology, 104(4), 905–927.

Walsh, F. (2003). Family resilience: A framework for clinical practice. Family Process, 42(1), 1–18.

Wildeman, C., Goldman, A. W., & Turney, K. (2018). Parental incarceration and child health in the United States. Epidemiologic Reviews, 40(1), 146–156.

Zimmerman, G. M., & Kushner, M. (2017). Examining the contemporaneous, short-term, and long-term effects of secondary exposure to violence on adolescent substance use. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 46(9), 1933–1952.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the parents and caregivers who participated in this study for their willingness to share their experiences with us; to the leadership and staff members of the Oregon Department of Corrections and of each of the participating correctional facilities for their engagement and support; to the leadership and staff members of The Pathfinders Network of Portland, Oregon for their partnership in conducting this study; and to the members of the Parent Child Study research team at the Oregon Social Learning Center of Eugene, Oregon.

Funding

Funding for the Parent Child Study was provided by Grants MH46690 and MH65553 from the Division of Epidemiology and Services Research, NIMH; by Grant HD054480 from the Social and Affective Development/Child Maltreatment and Violence, NICHD, U.S. PHS; by the Edna McConnell Clark Foundation; and by the legislature of the State of Oregon. O’Hara’s involvement in the preparation of this manuscript was supported by a career development award (K01MH120321) from NIMH. Rhodes and Blake’s involvement was supported by a training grant (2T32DA039772) from NIDA. Thomas’ involvement was supported by ASU’s Substance use and Addiction Translational Research Network (SATRN). Wolchik’s work on this paper was supported by a grant from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R01HD094334).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

This trial was designed in accordance with the basic ethical principles of autonomy, beneficence, justice, and non-maleficence and conducted in accordance with the rules of Good Clinical Practice outlined in the most recent Declaration of Helsinki. The project was approved by the Oregon Social Learning Center Institutional Review Board (IRB00000586). The use of deidentified secondary data was approved by the Arizona State University Institutional Review Board (IRB00013797; STUDY00013797).

Consent to Participate

Consent was obtained from all participants.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Berkel, C., O’Hara, K., Eddy, J.M. et al. The Prospective Effects of Caregiver Parenting on Behavioral Health Outcomes for Children with Incarcerated Parents: a Family Resilience Perspective. Prev Sci 24, 1198–1208 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-023-01571-9

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-023-01571-9