Abstract

This study investigates the relationship between public officials’ perceptions of organizational culture and their job attitudes, particularly emphasizing a mediating role of job satisfaction under the new public management reform in South Korea. Data collected from Korean civil servants indicate that perceptions of the competing values rooted in different organizational culture types—clan, market, hierarchy, and adhocracy—differentially affect their job attitudes. In addition, the findings show the mediating influence of job satisfaction between public officials’ perceptions of organizational culture and organizational commitment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In contrast to the popular belief that “Happy workers are productive” the organizational behavior literature argues that direct and distinct relationships between job attitudes and job performance are generally poor (Latham 2007; Bowling 2007) and instead vary considerably across contexts and with job complexity (Judge et al. 2001; Triandis 1994). Studies investigating this relationship within the context of relational dynamics such as leader-member exchange have indicated that a job environment is more important to understand the effects of employees’ attitudes on job performance (Harris et al. 2009; Triandis 1994).

Although organizational culture has not been a major focus of research examining job attitudes, and there have been few references to organizational culture among the major reviews and meta-analyses on the antecedents, correlates, and consequences of job attitudes (Bowling 2007; Judge et al. 2001; Meyer et al. 2010), a growing body of research includes organizational culture, one aspect of the job environment, particularly as an antecedent of job attitudes (Farh et al. 2007; Jackson 2002; Kim 2014; Ng et al. 2009; Saari and Judge 2004). Furthermore, in spite of great diversity among definitions and measures of organizational culture, some researchers have argued that organizational culture provides a lens for a better understanding of job attitudes, in that organizational culture directly and indirectly influences job attitudes, as well as their antecedents (Martin 1992; Trice and Beyer 1992). Nonetheless, there are only few established frameworks that explain how organizational culture affects employees’ job attitudes and, in turn, their behaviors in public management research (Ajzen 2006; Jackson 2002). Although several studies (e.g., Goulet and Frank 2002; Moon 2000; Wright and Davis 2003) have found different results in levels of job attitudes across different sectors, studies have not generally examined differences associated with organizational culture, and there have been a dearth of studies simultaneously investigating direct and indirect relationships among organizational culture, job satisfaction (JS), and organizational commitment (OC) in the public sector. Investigating the relationships between cultural elements and job attitudes could provide new understandings, particularly because values, which are seen as the core of organizational culture (Peters and Waterman 1982), have been shown to affect job attitudes (Eby and Dobbins 1997; Locke 1976). This study sheds light on the notion that culture, which includes shared values, is an important factor influencing job outcomes but there is variation in how employees perceive culture within an organization and the variation can lead to different outcomes with respect to job attitudes. This is important because perception, rather than an “objective reality,” will influence attitudes and behaviors.

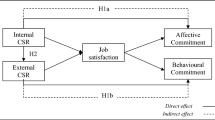

The goal of this research is to increase our understanding of how employee perception of cultural elements, i.e., values, influences their job attitudes in the context of the New Public Management (NPM, hereafter) Reform in South Korea. First, this study investigates the relationship between employee perception of organizational culture and job attitudes in the public sector, focusing specifically on whether values associated with different types of organizational culture have different impacts on employee attitudes. Second, this study examines whether JS mediates the relationship between employee perception of organizational culture and OC.

The following section introduces the research context and the theoretical background of this study. Then empirical evidence used to develop the conceptual model is presented (see Fig. 1). Next, the methods used for this study are described and the results of data analyses are reported. Lastly, findings and implications for theory and practice are discussed.

Research Context

To explore the relationship between public employees’ perception of culture and job attitudes, this research studies civil servants from a Korean government ministry during a time that involved a number of mergers and reorganizations. Since the governmental restructuring in 2008 by Lee Myoung-bak administration, most of the government ministries were reorganized in order to achieve a small but practical government that is effective and serves people first. During this process, the 18-Ministry and 4-Office system of the previous administration was reorganized into a 15-Ministry and 2-Office system through the integration or relocation of departments and offices. This reorganization, which was in line with themes of NPM, pointedly emphasized values and attributes of market and adhocracy cultures. Its stated goals—to attain efficiency and effectiveness, decrease redundant organizations, and ultimately to decrease the number of employees, while emphasizing that government needs to serve its citizens (Min 2008)—are clearly line with NPM principles. It should be noted that NPM, a globally prevailing managerial paradigm to enhance efficiency in the public sector, has proliferated in Korea since the 1990s, and has shifted the focus of public management from an emphasis on the implementation of formal rules based on hierarchical structures to an emphasis on client-oriented performance improvement in market-oriented and entrepreneurial ways (Osborne and Gaebler 1992; Parker and Bradley 2000). This period of organizational change provides an interesting context for surfacing the effect of organizational culture on employee attitudes in the public sector.

Organizational Culture and Values

Over the past three decades, there have been varying conceptions of culture (Martin 1992; Schein 1991). Nevertheless, there is a clear message from scholars in a variety of fields that culture plays a critical role with respect to organizational performance. Much of the literature regarding organizational culture emphasizes the notion of shared assumptions (Schein 2010), attitudes and perceptions that bind organizational members together and influence how they think about themselves, their coworkers, and their work (Alvesson 2002; Palthe and Kossek 2003), as well as values and behaviors and environmental and organizational realities that influence an organization (Kopelman et al. 1990). Schein’s (1981, 1990, 2010), conceptual framework of culture, which has been especially influential in the study of organizational culture, defines culture as “things that group members share or hold in common” (2010, p. 16), and emphasizes that culture involves assumptions, values, beliefs, adaptations, perceptions, and learning.

Not all researchers define culture as the ‘thing’ that holds the organization together. Martin (1992), for example, argues that organizational cultures are not necessarily unifying. She notes that culture is not static over time and that several different cultures can exist in the same organization. Thus, any definition of culture needs to take into account the possibility of competing subcultures that are a fact of life in the organization. In this regards, the Competing Values Framework (CVF) (Cameron and Quinn 2011) is noteworthy because it provides an organizing mechanism that sees organizations as having a dominant culture, but also recognizes that culture may change over time. Moreover, focusing on cultural values, CVF recognizes that subunits within an organization can have their own unique culture. Shared cultural values can be regarded as the crucial source of variation among organizational groups.

Competing Values Framework (CVF)

The Competing Values Framework (CVF) was developed using multidimensional scaling by Quinn and Rohrbaugh (1981) in an attempt to make sense of the organizational effectiveness literature, which provided contradictory definitions of organizational effectiveness and explanations of what makes an organization effective. The framework explains how people evaluate organizations and how organizations are characterized by a particular set of shared beliefs and values (Arsenault and Faerman 2014; Hartnell et al. 2010; Lund 2003). CVF also clarifies how values, as a key component of organizational culture, are communicated in organizations (Gregory et al. 2009; Helfrich et al. 2007; Mohr et al. 2012).

According to CVF, organizational culture can be measured along two dimensions or axes. The first focuses on the level of flexibility and individuality versus stability and organizational structuring; the second focuses on the degree to which attention is paid to internal organizational dynamics versus the external environment and the organization’s competitive position (Cameron and Quinn 2011). When juxtaposed, the two axes create four domains that represent four distinct cultures: Hierarchy, Clan, Adhocracy, and Market (see Fig. 2).

Competing values framework (K. S. Cameron and Quinn (2011))

The four cultures depicted in CVF represent a member’s values about an organization; what they define as good, right, and appropriate; and which core values are used for forming judgments and taking action (Goodman et al. 2001). The clan culture is characterized by cohesion, morale and an emphasis on human resource development. The adhocracy culture reflects a dynamic, entrepreneurial, and creative work environment that aims to grow and acquire resources through flexibility and readiness. The market culture focuses on getting the job done, and achieving productivity and efficiency. Finally, the hierarchy culture emphasizes a clear organizational structure, effective information management, and well-defined responsibilities and bureaucratic structures. Examining organizational culture based on the cultural attributes associated with the two value dimensions—internal/external focus and flexibility/stability—sheds light on how culture might influence employees’ attitudes (Cameron and Quinn 2011).

Although there is no one superior or ideal culture, organizations tend to develop a dominant orientation over time as they respond to challenges and changes in the environment (Schein 1991). As is true of individuals, organizations tend to respond to challenges and changes by amplifying their core cultural values so that various attributes of organizational culture become more solidified and prominent (Cameron and Quinn 2011). Cameron et al. (2007) note that while some organizations have a dominant type of culture, others have multiple cultures working simultaneously in different locations and departments.

Organizational Commitment (OC)

OC is a theoretical construct that examines employee-organization psychological linkages. According to Mowday et al. (1982), OC includes employees’ acceptance of organizational values and goals, their willingness to make strong efforts to support their organization in order to attain organizational goals, and their intention to maintain organizational membership. In contrast, Allen and Meyer’s (1990) definition of OC, which is one of the most commonly referred to in recent studies, examines three components of commitmentFootnote 1—affective commitment, continuance commitment, and normative commitment—only one of which focuses on employees’ acceptance of organizational goals. Common to these three components of OC, however, is the idea of a “psychological state that links an individual to an organization” (Allen and Meyer 1990, p. 14).

In extant OC studies, change initiatives, managerial paradigms, sectoral differences, and job insecurity have been shown to be antecedent variables of OC (e.g., Siegel et al. 2005; Perryer and Jordan 2005). In addition, OC has been found to predict organizational effectiveness and job performance (Riketta 2008; Sturges et al. 2005), as well as such job-related behaviors as turnover (e.g., Stinglhamber and Vandenberghe 2003; Sturges et al. 2005), intention to quit (e.g., Cole and Bruch 2006; Powell and Meyer 2004), and extra-role behaviors (e.g., Carmeli 2005; Mowday et al. 1982). Based on empirical evidence of affective commitment as the strongest and the most consistent construct related to organizational behaviors, this study focused on affective commitment as outcome in the research model.

Job Satisfaction (JS)

Job satisfaction (JS) is arguably one of the most explored work orientation variables in organizational studies over the last five decades (Anderson et al. 2001). In general, JS has been defined as the “emotional state of liking one’s job,” which results from employees’ job experiences (Locke 1976, p. 1300). Additionally, Ivancevich et al. (2007) point out that JS reflects employees’ perception of whether they fit into their organizations.

A substantial amount of empirical research has presented JS as an antecedent to affective commitment (e.g., Mowday et al. 1982; Vandenberg and Scarpello 1990). In addition, JS has been found to be a strong predictor of such organizational outcome variables as absenteeism, turnover, work performance, and prosocial behaviors (e.g., Tett and Meyer 1993; Trevor 2001). JS has also been studied as a dependent variable that is influenced by employees’ personal characteristics and job characteristics such as pay, promotion, job design, and having influence over goal setting (Agho et al. 1993; O’Leary-Kelly and Griffin 1995).

Relationships among Perception of Organizational Culture and OC, and JS

Only a few studies have employed CVF to investigate the relationship between employee perception of organizational cultures and employees’ job attitudes (e.g., Lund 2003). However, as Howard (1998) notes, CVF provides us with a “descriptive content” (p. 232) of organizational culture; it specifies configurations of organizational culture; and it provides tools for measuring and analyzing organizational culture. Moreover, values, which are central to CVF, have been regarded as a key element of organizational culture (Boxx et al. 1991; Braunscheidel et al. 2010; Robert and Wasti 2002), and are considered to be more tangible than assumptions and more stable than artifacts (Howard 1998). Thus, this study contributes to the literature by using an organizational culture framework that explicitly reflects values.

Although little research has examined the influence of perceived organizational culture on job attitudes using CVF, some studies contribute to our understanding of this relationship. For example, using Cameron and Freeman’s (1991) version of CVF to measure organizational culture, Lund (2003) found that overall JS is higher in perceived clan and adhocracy cultures, which focus on flexibility and spontaneity, than in perceived market and hierarchy cultures, which focus on control and stability. Similarly, researchers employing Wallach’s (1983) Organizational Culture Index to measure organizational culturesFootnote 2 have found that strong perceived bureaucratic cultures negatively affect employees’ JS and OC, whereas cultures valuing innovation and people in the organization positively influence employees’ job attitudes (Lok and Crawford 2001; Odom et al. 1990; Silverthorne 2004). Since JS and OC have been shown to have a positive relationship, Hypotheses 1a through 1d are suggested.

-

Hypothesis 1a: Perceived adhocracy culture will be positively associated with both their JS and OC.

-

Hypothesis 1b: Perceived clan culture will be positively associated with both their JS and OC.

-

Hypothesis 1c: Perceived hierarchical culture will be negatively associated with both their JS and OC.

-

Hypothesis 1d: Perceived market culture will be negatively associated with both their JS and OC.

This study also examines a mediating effect of JS on the relationship between perceived organizational culture and OC. While arguments have been made regarding their conceptual redundancy, JS and OC have been shown to be distinct variables in that OC focuses on employees’ attitudes toward the organization as a whole, whereas JS focuses on specific job characteristics (Vandenberg and Lance 1992). Investigating these two job attitudes in the context of their relationship to perceived organizational culture could thus be informative and further clarify their conceptual distinction.

Although some studies have found that JS and OS have a reciprocal relationship (e.g., Huang and Hsiao 2007), most research has assumed that JS influences OC (Buchanan 1974; Mowday et al. 1982; Reichers 1985) or that it plays a role as an intervening variable within relationships between other variables (e.g., structural determinants) and OC (e.g., Gaertner 1999; Lok and Crawford 2001; Markovits et al. 2010; Mueller and Lawler 1999; Wallace 1995). For example, using Meyer and Allen’s (1991) three-component model of OC, Clugston (2000) found that OC played a partially mediating role between JS and employees’ intent to leave. Similarly, Williams and Hazer (1986) found that JS mediates the relationship between all independent variables they studied (i.e., age, pre-employment expectations, perceived job characteristics, and the consideration dimension of leadership style) and OC. Arguably, JS, which is associated with job-specific characteristics, would more likely to be influenced by changes in working conditions than would OC, which would likely be more influenced by other components outside of the job (Mueller and Lawler 1999; Vandenberg and Lance 1992). Thus, we this study proposes that JS will mediate the relationship between perceived organizational culture and OC.

-

Hypothesis 2: The relationship between perceived organizational culture and OC will be mediated through JS.

Methods

According to the research purpose, this study included the ministries that were created by integrating two or more central government agencies.Footnote 3 That is, the ministries that were not merged were excluded from the data set. The survey was conducted by the Ministry of Public Administration and Security (MOPAS) including a wide range of information such as sex, age, positions, tenure, and so forth. The data collection method ensured that each employee could only respond once. In total, 421 of 749 public employees completed the survey, yielding a 56.07 % response rate.

As shown in Table 1, 73.5 % of the respondents were male and 25.6 % were female; 6.1 % were in the 20–29 age group, 37.5 % were in the 30–39 age group, 40.8 % were in the 40–49 age group, and 14.6 % were in the 50 or older age group. Regarding job position, 15.44 % of the respondents were at a managerial level (grade 4 or higher). In terms of years in current position, 22.1 % had been in their job less than 5 years, 13.7 % had been in their job between 6 and 10 years, 19.1 % had been in their job between 11 and 15 years, 18.5 % had been in their job between 16 and 20 years, and 25.5 % had been in their job over 20 years.

Since the data were not collected using random sampling, this study statistically tested whether sample proportions matched proportions of subgroups in the population, examining both the gender ratio and distributions of employees’ job grades in annual statistical reports of MOPAS. Our analyses showed no statistically significant differences in terms of gender ratio or ratio of managers to non-managers (two-sample proportion ratio test: z = −0.3547, p > .10 for gender ratio; z = −0.6857, p > .10 for manager ratio) (Table 2).

The survey used three instruments to measure the constructs in our conceptual framework. All instruments have previously shown acceptable levels of reliability and validity. Perceived organizational culture was measured using the 16 items of the Organizational Culture Assessment Instrument (OCAI)Footnote 4 (Cameron and Quinn 2011). Based on CVF, four attributes of culture—dominant characteristics, organizational leadership, organizational glue, management of employees—were measured. To measure affective commitment, Allen and Meyer’s (1990) Affective Commitment Scale (ACS) items were used. The items focus on employees’ feelings such as emotional attachment and dedication to the organization. A sample question is “I feel a strong sense of belonging to my organizations.”

Job satisfaction was measured using the Job Diagnostic Survey (JDS) (Hackman and Oldham 1975). This instrument measures both employees’ overall JS such as general satisfaction, internal work motivation, and growth satisfaction, and employees’ satisfaction with specific job facets—job security, compensation, co-workers, and supervisor. A sample question is “My job allows me be gone on my own to perform work my own.”

Results

Following a two-step analytical procedure, this study first examined the measurement model, and then used the structural model to test the proposed hypotheses. Covariation data was used as input to LISREL (Version 8.80). This section describes the results of data analyses, including descriptive statistics, reliability and validity statistics from the measurement structure, and results of the tests of the hypotheses.

Figure 3 shows the perceived cultural profile of the sample organization. Overall, attributes associated with each cultural type emerged and no one culture dominates over the others. Nevertheless, employees perceive attributes of market culture to be the strongest across the four types of culture, followed by attributes of hierarchy, clan, and adhocracy cultures, although the differences are generally small (Market: 4.52, hierarchy: 4.48, clan: 4.50, adhocracy: 4.20).

The Measurement Model

Prior to testing the study hypotheses, tests of reliability and validity were conducted to ensure that the measures used in the study had appropriate psychometric properties (Kaplan 2008). Inter-construct correlation coefficient estimates, Cronbach alpha (α) coefficients (Cronbach 1951; Cronbach and Shavelson 2004), and factor loadings from a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) were all examined. Table 2 shows inter-construct correlations and Cronbach α coefficients along with descriptive statistics.

To examine convergent validity for each factor, average variance shared between each construct and its measure was calculated (Gall 2003). According to Fornell and Larcker (1981), the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) should be 0.50 or above. As seen in Table 2, all AVE statistics were greater than 0.50. In addition, the Cronbach α coefficients for all measurement constructs are acceptable (above .80), indicating that all measures have appropriate levels of reliability.

Since the four attributes of culture show high correlations with one another, a multicollinearity test was conducted using the variance inflation factor (VIF) to verify the existence of four distinct organizational cultures (see Table 3).Footnote 5 The VIFs for the four culture dimensions fell in the range of 3.16 to 4.67, which are smaller than 10, the standard criterion suggested by Pedhazur (1997). Thus, this study concludes that multicollinearity problem does not exist.

Finally, a second-order confirmatory factor analysis of the OCAI measures was conducted (see Table 4) using the following indices to test the model: (1) goodness-of-fit index (GFI); (2) adjusted goodness-of-fit index (AGFI); (3) comparative fit index (CFI); (4) normed fit index (NFI); and (5) root mean square residual (RMR). The CFA analysis results substantiate the adequacy of the item-to-factor associations and the number of dimensions underlying the proposed model (Hair et al. 2009), providing further evidence of construct validity in the OCAI model.

The Structural Model

To test the hypotheses, the data was analyzed based on the structural model (see Fig. 4) using the maximum likelihood method to estimate the model. Figure 4 shows estimated path coefficients and the associated t-values of the paths. The fit statistics indicate that the research model provides a good fit to the data (CFI = .97; NFI = .97; RMR = .03). The indices are within the range that suggests a good model fit. This study therefore proceeded to test the specified paths for the specific hypotheses.

Collective associations among the exogenous and endogenous variables, path coefficient estimates for all relationships among the constructs, and standardized path coefficient estimates were examined to determine the overall effect sizes of each relationship (Hair et al. 2009; Kline 2010). As the standard determinant for the statistical significance of standardized path coefficients, a cut-off t-value (t-value ≥ |1.96|) was applied (Kline 2010).

Figure 4 shows that not all types of perceived organizational culture have a significant effect on employees’ attitudes. In particular, a non-significant direct paths were found for the adhocracy culture (γ1 = −.23; |t| = 1.08 and γ2 = 0.26; |t| = 1.37). Employees’ perceptions of clan and hierarchy culture in their organizations have a statically significant direct effect on both JS (γ5 = 1.16; |t| = 6.07 and γ7 = −.50; |t| = 3.33, respectively) and OC (γ6 = −0.45; |t| = 2.77 and γ8 = 0.86; |t| = 6.84, respectively). Market culture perceived by individuals do not have a significantly negative effect on JS (γ3 = 0.06; |t| = 0.29), but do have a significantly negative effect on employees’ OC (γ4 = 0.44; |t| = 2.81).

Although perceived clan culture appears to have a negative effect on OC, there is a need to consider the total effects of the cultural dimensions on OC, which are composed of both direct effects and indirect effects through JS. Table 5 shows that employees’ perceptions of the attributes of the clan culture ultimately have a positive effect on OC because the indirect effects through JS are larger than the negative direct effect.

Finally, according to the path coefficients estimates (β 1 = .60; |t| = 17.82), overall JS plays mediating role in the relationship between organizational culture and employees’ OC. Table 6 shows the summarized results for the hypothesis tests.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to explore the direct and inverse relationship between perceived organizational culture and employees’ attitude. Overall, our findings showed that different attributes of organizational culture differently affect JS and OC. Perceived values of clan culture positively affect employees’ JS, but negatively affect employees’ commitment to their organization in terms of the direct effect, whereas perceived attributes of hierarchy culture negatively influence employees’ JS but positively affect their OC. Moreover, perceived values of market culture in the organization did not affect JS but negatively affected OC.

It is interesting that the directions of the path coefficients from perceived organizational culture to JS were in line with the hypotheses, while the path coefficients from perceived organizational culture to OC, except in the case of market culture, were not. That is, our findings indicate that employees’ perception of clan culture decreases the level of OC [through a direct path] whereas their perception of hierarchical culture enhances their commitment. In addition, values associated with market culture—competition and a result-orientation—appear to negatively affect employees’ commitment. Thus, despite the fact that Korean government has adopted NPM practices that emphasize market-oriented values and customer-oriented performance, public employees might thus still prefer organizational stability and integration values over competitiveness and change.

Interestingly, the directions of path coefficients to JS and OC are opposite although JS mediates the relationship between perceived organizational culture and OC. The negative relationship in the direct path between attributes of clan culture and OC might be related to the specific focus of commitment. Clan culture focuses on teamwork and concern for people, which might induce employees to commit to coworkers or supervisors rather than to their organization.

Theoretical Implications

Given that public and private sector organizations are distinct with regard to organizational culture, structures, work environments, job characteristics, and job attitudes (Moon 2000; Rainey 2009), there is a need to investigate these relationships further in the public sector. This study suggests several important implications for theory. Overall, the findings present additional empirical support for the notion that perceived values associated with organizational culture influence employees’ attitudes (Howard 1998). Our finding that attributes of the different cultures differently affect employees’ job attitudes raises questions regarding value congruence between existing organizational values and values emphasized through organizational change initiatives. In particular, the negative effects of perceived market culture on OC and the nonsignificant effects of perceived adhocracy culture on job attitudes imply that NPM might not be effective in Korean public organizations or that these values are not viewed positively by public employees.

Most importantly, study provides additional empirical support for the notion that perceived organizational culture should be considered as an important influence on job attitudes, and sheds light on the relationship between perceived organizational culture and job attitudes in public sector organizations. As noted earlier, organizational culture has not received much attention as a determinant of job attitudes relative to structural antecedents of job attitudes. In that public sector organizations have been regarded as different from private sector organizations in terms of job characteristics, employees’ motivation, work environment and so forth, studies examining the influence of perceived organizational culture on work-related variables in public sector organizations are much needed. Overall, this study contributes to the organizational behavior literature by examining the relationship between perceived organizational culture and job attitudes of public sector employees, an area that has received little attention in previous literature.

Lastly, this study empirically demonstrated that JS precedes OC and plays a mediating role between perceived organizational culture and OC. As mentioned above, this is consistent with the majority of studies examining the relationship between JS and OC, although there is still not full consensus regarding the relationship between the two job attitudes. In this regard, this study contributes to the literature by providing additional empirical evidence for the relationship between JS and OC.

Practical Implications

Our findings also offer important implications for public management practitioners. First, the finding that perceived market culture negatively affect OC implies that the current emphasis on NPM in public sector organizations might be less effective in the long run than is currently assumed. If NPM conflicts with shared values of employees and perceived cultures in public organizations, as indicated in several previous studies (Harrow and Willcocks 1990; Parker and Bradley 2000), the implementation of NPM might not lead to expected increases in productivity and efficiency in the public sector.

The finding that perceived values associated with clan culture positively affect both JS and OC imply that public management practices valuing participation, teamwork, and sense of family enhance employees’ job attitudes in a more effective and stable way, especially in comparison with attributes of cultures having an opposite directional influence on these job attitudes. Interestingly, although perceived values associated with hierarchy culture negatively influence JS, they have a large positive effect on OC. Hence, managerial practices associated with values of hierarchy culture, such as order, formal rules and regulation, still might be effective or necessary in public sector organizations. For example, one would expect that public employees’ tasks should be in accordance with the law and regulatory rules. Thus, managerial practices overemphasize competition and efficient performance might conflict with cultural values emphasizing accountability and formal procedures.

Limitations

This study has several certain limitations. First, findings are based on the perceptions of employees who voluntarily responded to the questionnaire, and may not be representative of all the employees in the Ministry. In addition, our sample is drawn from one central public agency in Korea, and so the findings may not be generalizable to private sector organizations, other Korean central government agencies, government organizations at the local level, or organizations in other national settings.

Second, the data reflect these employees’ perceptions of attributes of organizational culture, rather than objective measures of these variables. Third, the model did not consider subcultures, but rather looked at the Ministry as a whole. Although cultures often differ across departments, divisions, or teams, analyses were not conducted for subunits of the organization. Finally, it should be noted that the data were collected from the sample during a specific time span, and so the analyses do not reflect longitudinal changes. All of these limitations suggest that results must be interpreted with caution.

Areas for Further Research

The theoretical implications and limitations of this study suggest several ideas for further research. First, the differential directions of effects of perceived organizational culture on the two job attitudes raise important questions. This finding is counterintuitive and in contradiction to the study hypotheses, which were derived from current theory and empirical research, which suggests that job attitudes will be affected in the same direction (e.g., Gaertner 1999; Lok and Crawford 2001). Further research is necessary to examine specific conditions that might lead to such results.

Second, more research comparing private, public or nongovernment (nonprofit) sector organizations will be needed. Building on findings presented in this study, future research on whether perceived hierarchical culture influences job attitudes differently across settings would be particularly valuable.

Third, this study examined organizational culture using individual perceptions of organizational-level culture. Future studies might examine the relationships between organizational culture and job attitudes at the subunit level.

Finally, this study examined OC. Employees can, however, be committed differentially to the organization as a whole, their supervisors, coworkers, career, and so on (Meyer et al. 1993; Reichers 1985). Our finding of a negative direct effect of employees’ perception of clan culture on their OC might be associated with the specific focus of employee commitment. Arguably, clan culture, which values warmness and caring between people, might lead employees to commit more to their coworkers or team than to the organization as a whole. Future studies considering foci of commitment might provide more tailored explanations.

Concluding Remarks

This study investigated the relationship between perceived organizational culture and employees’ job attitudes in a Korean central agency in the context of the NPM Reform. The findings indicate that employees’ perception of attributes of organizational culture differentially affect employees’ job attitudes. Moreover, the findings provide additional empirical support for the proposition that JS precedes employees’ OC and plays a mediating role for JS within a relationship between perceived cultural values and OC. Overall, this study contributes to public management theory in that the findings support the impact of perceived organizational culture on employees’ job attitudes in the public organization context, an area where there has been a relative lack of empirical research. In addition, our findings suggest a need for managers and those developing organizational policies for public organizations to look more closely at whether managerial practices aligned with values associated with NPM fit well into public organizations where traditional values are still appreciated.

Notes

“Affective commitment refers to the employee’s emotional attachment to, identification with, and involvement in the organization… Continuance commitment refers to an awareness of the costs associated with leaving the organization… Finally, normative commitment reflects a feeling of obligation to continue employment.” (Meyer and Allen 1997, p. 11).

Wallach’s (1983) supportive culture, innovative culture, and bureaucratic culture, with orientations of culture related to people, innovation, and [stable] bureaucratic structure, respectively, are close to clan culture, adhocracy culture, and hierarchy culture from CVF, in terms of what each culture values in an organization.

To ensure confidentiality as requested, we will not reveal actual name of the ministry here.

Since we focused on intra-organizational variability with regard to employee perception of culture, we used individual-level data and used individuals as the level of analysis.

Although the four cultures are conceptually distinct, one should expect high statistical correlations among the cultural measures because the four cultures emerge from two dimensions, and so overlap in focus. For example, clan and adhocracy share an emphasis on flexibility; clan and hierarchy are both internally-focused; and so on. Tests of multicollinearity allow us to examine the degree to which this affects the statistical analysis.

References

Agho, A. O., Mueller, C. W., & Price, J. L. (1993). Determinants of employee job satisfaction: an empirical test of a causal model. Human Relations, 46(8), 1007–1027. doi:10.1177/001872679304600806.

Ajzen, I. (2006). Perceived behavioral control, self-efficacy, locus of control, and the theory of planned behavior. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 32(4), 665–683.

Allen, N. J., & Meyer, J. P. (1990). The measurement and antecedents of affective, continuance and normative commitment to the organization. Journal of Occupational Psychology, 63(1), 1–18. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8325.1990.tb00506.x.

Alvesson, M. (2002). Understanding organizational culture. London: Sage.

Anderson, N., Ones, D., Sinangil, H. K., & Viswesvaran, C. (2001). Handbook of industrial, work & organizational psychology (Vol. 1 & 2). CA: Sage.

Arsenault, P., & Faerman, S. R. (2014). Embracing paradox in management: the value of the competing values framework. Organization Management Journal, 11(3), 147–158.

Bowling, N. A. (2007). Is the job satisfaction-job performance relationship spurious? A meta-analytic examination. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 71(2), 167–185. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2007.04.007.

Boxx, W. R., Odom, R. Y., & Dunn, M. G. (1991). Organizational values and value congruency and their impact on satisfaction, commitment, and cohesion: an empirical examination within the public sector. Public Personnel Management, 20(2), 195–205. doi:10.1177/009102609102000207.

Braunscheidel, M. J., Suresh, N. C., & Boisnier, A. D. (2010). Investigating the impact of organizational culture on supply chain integration. Human Resource Management, 49(5), 883–911. doi:10.1002/hrm.20381.

Buchanan, B. (1974). Building organizational commitment: the socialization of managers in work organizations. Administrative Science Quarterly, 19(4), 533–546.

Cameron, K. S., & Freeman, S. J. (1991). Cultural congruence, strength, and type: relationships to effectiveness. Research in Organizational Change and Development, 5, 23–58.

Cameron, K. S., & Quinn, R. E. (2011). Diagnosing and changing organizational culture: based on the competing value framework (3rd ed.). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Cameron, K. S., Quinn, R. E., DeGraff, J., & Thakor, A. V. (2007). Competing values leadership: creating value in organizations. MA: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Carmeli, A. (2005). Perceived external prestige, affective commitment, and citizenship behaviors. Organization Studies, 26(3), 443–464. doi:10.1177/0170840605050875.

Clugston, M. (2000). The mediating effects of multidimensional commitment on job satisfaction and intent to leave. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 21(4), 477–486. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1099-1379(200006)21:4<477::AID-JOB25>3.0.CO;2-7.

Cole, M. S., & Bruch, H. (2006). Organizational identity strength, identification, and commitment and their relationships to turnover intention: does organizational hierarchy matter? Journal of Organizational Behavior, 27(5), 585–605.

Cronbach, L. J. (1951). Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika, 16(3), 297–334. doi:10.1007/BF02310555.

Cronbach, L. J., & Shavelson, R. J. (2004). My current thoughts on coefficient alpha and successor procedures. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 64(3), 391–418. doi:10.1177/0013164404266386.

Eby, L. T., & Dobbins, G. H. (1997). Collective orientation in teams: an individual and group-level analysis. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 18, 275–295. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1099-1379(199705)18:3<275::AID-JOB796>3.0.CO;2-C.

Farh, J. L., Hackett, R., & Liang, J. (2007). Individual-level cultural values as moderators of perceived organizational support-employee outcome relationships in China: comparing the effects of power distance and Traditionality. The Academy of Management Journal, 50(3), 715–729.

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: algebra and statistics. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(3), 382–388. doi:10.2307/3150980.

Gaertner, S. (1999). Structural determinants of job satisfaction and organizational commitment in turnover models. Human Resource Management Review, 9(4), 479–493. doi:10.1016/S1053-4822(99)00030-3.

Gall, M. (2003). Educational research: an introduction. Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

Goodman, E. A., Zammuto, R. F., & Gifford, B. D. (2001). The competing values framework: understanding the impact of organizational culture on the quality of work life. Organization Development Journal, 19(3), 58–68.

Goulet, L. R., & Frank, M. L. (2002). Organizational commitment across three sectors: public, non-profit, and for-profit. Public Personnel Management, 31(2), 201–210. doi:10.1177/009102600203100206.

Gregory, B. T., Harris, S. G., Armenakis, A. A., & Shook, C. L. (2009). Organizational culture and effectiveness: a study of values, attitudes, and organizational outcomes. Journal of Business Research, 62(7), 673–679. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2008.05.021.

Hackman, J. R., & Oldham, G. R. (1975). Development of the job diagnostic survey. Journal of Applied Psychology, 60(2), 159–170. doi:10.1037/h0076546.

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2009). Multivariate data analysis. New Jersey: Prentice Hall.

Harris, K. J., Wheeler, A. R., & Kacmar, K. M. (2009). Leader-member exchange and empowerment: direct and interactive effects on job satisfaction, turnover intentions, and performance. The Leadership Quarterly, 20(3), 371–382. doi:10.1016/j.leaqua.2009.03.006.

Harrow, J., & Willcocks, L. (1990). Public services management: activities, initiatives and limits to learning. Journal of Management Studies, 27(3), 281–304. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6486.1990.tb00248.

Hartnell, C. A., Ou, A. Y., & Angelo, K. (2011). Organizational culture and organizational effectiveness: a meta-analytic investigation of the competing values Framework’s theoretical suppositions. Journal of Applied Psychology, 96(4), 677–694. doi:10.1037/a0021987.

Helfrich, C. D., Li, Y. F., Mohr, D. C., Meterko, M., & Sales, A. E. (2007). Assessing an organizational culture instrument based on the competing values framework: exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses. Implementation Science, 2(1), 13–26. doi:10.1186/1748-5908-2-13.

Howard, L. W. (1998). Validating the competing values model as a representation of organizational cultures. International Journal of Organizational Analysis, 6(3), 231–253.

Huang, T., & Hsiao, W. (2007). The causal relationship between job satisfaction and organizational commitment. Social Behavior and Personality, 35(9), 1265–1276. doi:10.1108/eb028886.

Ivancevich, J. M., Konopaske, R., & Matteson, M. T. (2007). Organizational behavior and management. McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc.

Jackson, T. (2002). The Management of People across cultures: valuing people differently. Human Resource Management, 41(4), 455–475. doi:10.1002/hrm.10054.

Judge, T. A., Thoreson, C. J., Bono, J. E., & Patton, G. K. (2001). The job satisfaction-job performance relationship: a qualitative and quantitative review. Psychological Bulletin, 127(3), 376–407. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.127.3.376.

Kaplan, D. W. (2008). Structural equation modeling: foundations and extensions. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Kim, H. (2014). Transformational leadership, organizational clan culture, organizational affective commitment, and organizational citizenship behavior: a case of South Korea’s public sector. Public Organization Review, 14(3), 397–417. doi:10.1007/s11115-013-0225-z.

Kline, R. B. (2010). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. NY: Guilford Press.

Kopelman, R. E., Brief, A. P., & Guzzo, R. A. (1990). The role of climate and culture in productivity. In B. Schneider (Ed.), Organizational climate and culture. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Latham, G. P. (2007). Work motivation: history, theory, research, and practice. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Locke, E. A. (1976). The nature and causes of job satisfaction. In M. D. Dunnette & L. M. Hough (Eds.), Handbook of industrial and organizational psychology. Palo Alto: Consulting Psychologists Press.

Lok, P., & Crawford, J. (2001). Antecedents of organizational commitment and the mediating role of job satisfaction. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 16(8), 594–613. doi:10.1108/EUM0000000006302.

Lund, D. B. (2003). Organizational culture and job satisfaction. Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, 18(3), 219–236. doi:10.1108/0885862031047313.

Markovits, Y., Davis, A. J., Fay, D., & van Dick, R. (2010). The link between job satisfaction and organizational commitment: differences between public and private sector employees. International Public Management Journal, 13(2), 177–196. doi:10.1080/10967491003756682.

Martin, J. (1992). Cultures in organizations: three perspectives. Oxford University Press.

Meyer, J. P., & Allen, N. J. (1991). A three-component conceptualization of organizational commitment. Human Resource Management Review, 1(1), 61–89. doi:10.1016/1053-4822(91)90011-Z.

Meyer, J. P., & Allen, N. J. (1997). Commitment in the workplace: theory, research, and application. CA: Sage.

Meyer, J. P., Allen, N. J., & Smith, C. A. (1993). Commitment to organizations and occupations (Extension and test of a three-component conceptualization). Journal of Applied Psychology, 78(4), 538–551. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.78.4.538.

Meyer, J. P., Hecht, T. D., Gill, H., & Toplonytsky, L. (2010). Person–organization (culture) fit and employee commitment under conditions of organizational change: a longitudinal study. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 76(3), 458–473.

Min, J. (2008). A case study on the reorganization of Korean central government, Lee Administration, February 2008. Journal of Korean Organizational Studies, 5(2), 267–292.

Mohr, D. C., Young, G. J., & Burgess Jr., J. F. (2012). Employee turnover and operational performance: the moderating effect of group-oriented organisational culture. Human Resource Management Journal, 22(2), 216–233.

Moon, M. J. (2000). Organizational commitment revisited in new public management: motivation, organizational culture, sector, and managerial level. Public Performance and Management Review, 24(2), 177–194. doi:10.2307/3381267.

Mowday, R. T., Porter, L. W., & Steers, R. M. (1982). Employee-organization linkages: the psychology of commitment, absenteeism, and turnover. Academic Press.

Mueller, C. W., & Lawler, E. J. (1999). Commitment to nested organizational units: some basic principles and preliminary findings. Social Psychology Quarterly, 62(4), 325–346. doi:10.2307/2695832.

Ng, T. W. H., Sorensen, K. L., & Yim, F. H. K. (2009). Does the job satisfaction-job performance relationship vary across cultures? Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 40(5), 761–796.

O’Leary-Kelly, A. M., & Griffin, R. W. (1995). Job satisfaction and organizational commitment. In N. Brewer and C. Wilson (eds.). Psychology and Policing, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Odom, R. Y., Boxx, W. R., & Dunn, M. G. (1990). Organizational cultures, commitment, satisfaction, and cohesion. Public Productivity and Management Review, 14(2), 157–169. doi:10.2307/3380963.

Osborne, D., & Gaebler, T. (1992). Reinventing government: how the entrepreneurial spirit is transforming the public sector. Addison-Wesley.

Palthe, J., & Kossek, E. E. (2003). Sub-cultures and employment modes: translating HR strategy into practice. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 16(3), 287–309. doi:10.1108/09534810310475532.

Parker, R., & Bradley, L. (2000). Organisational culture in the public sector: evidence from six Organisations. International Journal of Public Sector Management, 13(2), 125–141. doi:10.1108/09513550010338773.

Pedhazur, E. J. (1997). Multiple regression in behavioral research: explanation and prediction. Orlando: Harcourt Brace.

Perryer, C., & Jordan, C. (2005). The influence of leader behaviors on organizational commitment: a study in the Australian public sector. International Journal of Public Administration, 28(5), 379–396. doi:10.1081/PAD-200055193.

Peters, T., & Waterman, R, H. (1982). In search of excellence, New York: Harper and Row.

Powell, D. M., & Meyer, J. P. (2004). Side-bet theory and the three-component model of organizational commitment. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 65(1), 157–177. doi:10.1016/S0001-8791(03)00050-2.

Quinn, R. E., & Rohrbaugh, J. (1981). A competing values approach to organizational effectiveness. Public Productivity Review, 5(2), 122–140. doi:10.2307/3380029.

Rainey, H. G. (2009). Understanding and managing public organizations. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Reichers, A. E. (1985). A review and reconceptualization of organizational commitment. The Academy of Management Review, 10(3), 465–476.

Riketta, M. (2008). The causal relation between job attitudes and performance: a meta-analysis of panel studies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93(2), 472–481. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.93.2.472.

Robert, C., & Wasti, S. A. (2002). Organizational individualism and collectivism: theoretical development and an empirical test of a measure. Journal of Management, 28(4), 544–566. doi:10.1177/014920630202800404.

Saari, L. M., & Judge, T. A. (2004). Employee attitudes and job satisfaction. Human Resource Management, 43(4), 395–407. doi:10.1002/hrm.20032.

Schein, E. H. (1981). Does Japanese management style have a message for American managers? Sloan Management Review, 21(1), 55–68.

Schein, E. H. (1990). Organizational Culture. American Psychologist, 45(2), 109–119. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.45.2.109.

Schein, E. H. (1991). What is culture? In P. Frost, L. Moore, M. Louis, C. Lundberg, & J. Martin (Eds.), Reframing organizational culture. Newbury Park: Sage.

Schein, E. H. (2010). Organizational culture and leadership (4th ed.). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Siegel, P. A., Post, C., Brockner, J., Fishman, A. Y., & Garden, C. (2005). The moderating influence of procedural fairness on the relationship between work-life conflict and organizational commitment. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(1), 13–24. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.90.1.13.

Silverthorne, C. (2004). The impact of organizational culture and person-organization fit on organizational commitment and job satisfaction in Taiwan. Leadership and Organization Development Journal, 25(7), 592–599. doi:10.1108/01437730410561477.

Stinglhamber, F., & Vandenberghe, C. (2003). Organizations and supervisors as sources of support and targets of commitment: a longitudinal study. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 24(3), 251–270. doi:10.1002/job.192.

Sturges, J., Conway, N., Guest, D., & Liefooghe, A. (2005). Managing the career deal: the psychological contract as a framework for understanding career management, organizational commitment and work behavior. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 26(7), 821–838. doi:10.1002/job.341.

Tett, R. P., & Meyer, J. P. (1993). Job satisfaction, organizational commitment, turnover intention, and turnover: path analyses based on meta-analytic findings. Personnel Psychology, 46(2), 259–293. doi:10.1111/j.1744-6570.1993.tb00874.x.

Trevor, C. O. (2001). Interactions among actual ease-of-movement determinants and job satisfaction in the prediction of voluntary turnover. The Academy of Management Journal, 44(4), 621–638. doi:10.2307/3069407.

Triandis, H. C. (1994). Culture and social behavior. New York: McGraw-Hill Press.

Trice, H., & Beyer, J. (1992). The culture of work organizations. NJ: Simon & Schuster.

Vandenberg, R. J., & Lance, C. E. (1992). Examining the causal order of job satisfaction and organizational commitment. Journal of Management, 18(1), 153–167. doi:10.1177/014920639201800110.

Vandenberg, R. J., & Scarpello, V. (1990). The matching model: an examination of the processes underlying realistic job previews. Journal of Applied Psychology, 75(1), 60–67.

Wallace, J. E. (1995). Organizational and professional commitment in professional and nonprofessional organizations. Administrative Science Quarterly, 40(2), 228–255. doi:10.2307/2393637.

Wallach, E. J. (1983). Individuals and organizations: the cultural match. Training and Development Journal, 37(2), 28–36.

Williams, L. J., & Hazer, J. T. (1986). Antecedents and consequences of satisfaction and commitment in turnover models: a reanalysis using latent variable structural equation methods. Journal of Applied Psychology, 71(2), 219–231. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.71.2.219.

Wright, B. E., & Davis, B. S. (2003). Job satisfaction in the public sector. The American Review of Public Administration, 33(1), 70–90. doi:10.1177/0275074002250254.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Professor Sue R. Faerman for her invaluable advice and critical comments on an earlier draft and to Dr. Geunpil Ryu for his help on data collection for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

This work was supported by the Ministry of Education of the Republic of Korea and the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF-2015S1A3A2046562).

Additional information

The original version of this article was revised: The caption of Fig. 2 is not correct. Figure 2 caption should read as 'Fig. 2 Competing values framework (K. S. Cameron and Quinn (2011))'

An erratum to this article is available at http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11115-017-0382-6.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, J.S., Han, SH. Examining the Relationship between Civil Servant Perceptions of Organizational Culture and Job Attitudes: in the Context of the New Public Management Reform in South Korea. Public Organiz Rev 17, 157–175 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11115-016-0372-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11115-016-0372-0