Abstract

Political scientists and legal scholars debate the value of judicial elections, including the degree to which elections effectively hold incumbent judges accountable. In this paper, we provide a causally identified estimate of the incumbency advantage in judicial elections. We assemble an original dataset of over 5300 partisan, single-member trial court elections from six U.S. states. Employing a regression discontinuity design, we demonstrate that incumbents enjoy electoral advantages of more than twenty percentage points due solely to being an incumbent. In contrast to research from other electoral settings, we find that these advantages are due largely to a scare-off effect, where even a narrow victory dramatically decreases the probability that an incumbent party will be challenged in the next election. Our findings highlight the sizable electoral returns to holding judicial office, reveal how the nature of the incumbency advantage varies across electoral settings, and provide compelling evidence of the challenges to holding trial court judges accountable through elections.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

One of the most unique features of American democracy is the popular election of judges. More than forty states use popular elections to choose at least some of their judges, affording their citizens an opportunity to hold judges accountable that is absent in nearly every other democracy. It remains an open question, however, whether these elections actually function in a way that enhances accountability over other methods of judicial selection. Judicial elections are plagued by low levels of competition (Baum 1983; Nelson 2010) and voter engagement and knowledge (Dubois 1980); however, evidence suggests that certain institutional arrangements, campaign spending, and advertisements can mitigate these problems (Bonneau and Hall 2003, 2009; Hall and Bonneau 2008; Klein and Baum 2001).

An important prerequisite to holding incumbent officeholders accountable is capacity to vote them out of office. It is for this reason that the concept of an incumbency advantage—a built-in advantage afforded to incumbent officeholders that is due only to being an incumbent—has received considerable attention in studies of electoral politics (e.g., Erikson 1971; Gelman and King 1990; Lee 2008). In this paper, we provide, to our knowledge, the first estimate of the built-in incumbency advantage in judicial elections. In so doing, we provide two major contributions to the study of judicial elections. First, by uncovering the causal effect of incumbency on future electoral fortunes, we disentangle and directly quantify the normatively troubling aspect of incumbency—the degree to which judicial incumbents benefit solely from holding office—from the desirable components of incumbency, such as incumbent quality. Our findings illustrate the inherent challenge to accountability in judicial elections and build upon existing studies of judicial elections that explore the nature of incumbency in judicial elections but, because of their research designs, cannot adjudicate between these two components of incumbency (e.g., Baum 2003; Bonneau and Hall 2003; Bonneau 2005; Bonneau and Cann 2011; Hall and Bonneau 2005; Streb and Frederick 2009).

Second, our study reveals the presence of a significant scare-off effect in judicial elections. In the judicial elections of our study—in contrast to legislative, gubernatorial, and other electoral contexts (Hall et al. 2015)—the incumbency advantage is driven primarily by a dramatic decrease in the probability that an incumbent faces a contested election in the future. We thus reveal novel information about the function and structure of electoral institutions and speak to the unique aspects of judicial elections that distinguish the judiciary from other elected offices in American politics.

To estimate the incumbency advantage, we use a regression discontinuity design that allows us to credibly estimate the causal effect of incumbency on subsequent electoral fortunes. By comparing situations where a party barely wins or loses, resulting in as-if-random assignment to either incumbent or non-incumbent status, we are able to provide careful and credible estimates of the incumbency advantage. This approach allows us to ensure that the candidates are ex ante comparable on characteristics such as quality, and therefore isolates the built-in advantage afforded to incumbent judges by dint of holding office and the experience and name recognition that comes with it. Importantly, these close elections are those in which an incumbency advantage is of the most practical importance, as even a narrow victory could significantly affect a candidate’s future electoral fortunes. A series of validity checks indicate that our study likely satisfies the assumptions required for the use of the regression discontinuity design (de la Cuesta and Imai 2016).

We compile an original dataset of over 5300 trial court elections from states that use partisan elections to elect and re-elect these judges. Focusing on these elections provides at least four distinct benefits. First, focusing on partisan elections provides a tough test of the incumbency advantage in comparison to nonpartisan and retention elections, as partisan elections have been shown to spur voter engagement and contestation (e.g., Bonneau and Hall 2009; Hall and Bonneau 2008). Second, we provide much-needed insight into levels of accountability at the foundational level of the judicial hierarchy. Trial courts are the workhorse of the American judicial system—where the overwhelming majority of cases are heard, where the bulk of sentences and rulings are handed down, and where most citizens’ engagement with the judiciary takes place.Footnote 1 Despite the central role of trial courts in the American legal system, almost all studies of judicial elections, including studies that explore incumbent retention rates and vote shares (c.f. Nelson 2010), focus on state appellate and high courts. Third, our sample of six states allows us to be confident that our findings are not driven by a single state’s political or electoral climate. Finally, focusing on partisan elections allows us to apply the regression discontinuity design used in other electoral contexts to obtain credible causal estimates of the incumbency advantage in judicial elections.

Our analysis reveals a substantively significant incumbency advantage for trial court judges of more than twenty percentage points. Our findings are robust to a series of alternative model specifications and estimation strategies. The large incumbency advantage we identify serves as compelling evidence that elections for state trial courts have systematic limitations in their capacity to hold incumbent judges accountable. We then investigate the extent to which this incumbency advantage is driven by a scare-off effect—the deterrence of a challenger candidate entering to run against the incumbent. We find that an overwhelming share of the incumbency advantage we uncover is due to scare off; a narrow win results in over a 20-percentage point decrease in the likelihood that the winning party’s candidate receives a challenger in the next election. While Eggers (2017) shows that some of the incumbency advantage uncovered in regression discontinuity designs may be due to normatively desirable quality-based explanations, the large scare-off effect that we identify is suggestive of systematic limitations to accountability in judicial elections absent from other electoral settings in American politics. While we focus on only one (low) level of the judicial hierarchy, our results provide both new information about accountability at the level of the judiciary that citizens most directly engage with and also contribute to a more complete understanding of the dynamics of the incumbency advantage across electoral contexts.

Electoral Competition and the Incumbency Advantage

Electoral competition lies at the heart of the democratic process. The ability of the electorate to hold elected officials accountable for their behavior is limited without a choice between alternatives and the possibility of voting an incumbent out of office. Although scholars debate the degree to which competitiveness leads to a Downsian convergence of candidate positions to the median voter, contested elections appear to be associated with greater responsiveness to constituent preferences (Powell 2000).

These normative implications have led to the development of a literature that examines competition across electoral contexts. One key concept in this literature is that of the incumbency advantage: the benefit that accrues to incumbents simply by holding office. Focusing primarily on legislative contexts, most prominently the U.S. House, scholars have sought to measure and quantify the incumbency advantage (e.g., Gelman and King 1990), track its size across time (e.g., Jacobson 2015) and explain its sources (Cox and Katz 1996; Levitt and Wolfram 1997) and consequences (King and Gelman 1991; Erikson 2017). Subsequent scholarship has identified the existence of an incumbency advantage across a variety of elected offices in the United States, including state legislative (Hall et al. 2015), gubernatorial and other statewide (Ansolabehere et al. 2002), mayoral (de Benedictis-Kessner 2017), and city council offices (Trounstine 2011). The presence of a built-in electoral advantage endowed to officeholders has clear implications for democratic accountability and representation. The incumbency advantage is normatively troubling insofar as it reduces the need for incumbents to be accountable to constituents (King and Gelman 1991), contributes to the weakening of the candidate pool (Cox and Katz 1996), and leads to pathological behavior—such as designing institutions that perpetuate incumbent success at the expense of good governance—by those holding elected office (Fiorina 1989). Recent work, however, has highlighted the possibility that the existence of an incumbency advantage merely reflects an election process that accurately selects higher-quality candidates (Ashworth et al. 2008; Eggers 2017).

Students of American judicial elections have long concerned themselves with questions of accountability. An ongoing debate considers the degree to which voters are engaged in judicial elections, with critics pointing to generally low levels of voter engagement in and knowledge of judicial candidates as evidence that judicial elections cannot generate accountability and as reasons to reform or altogether abolish judicial elections (Dubois 1980; Geyh 2003). Others have pointed to certain electoral institutions, such as partisan elections and the role of campaign spending and advertisements, in boosting voter participation in elections (Bonneau and Hall 2009; Hall and Bonneau 2008; Klein and Baum 2001). Another important line of inquiry regards competition in judicial elections, with more pessimistic views suggesting that low levels of competition inhibit the accountability mechanism (Nelson 2010) and rosier views highlighting the role of institutions and campaign spending in leveling the playing field for candidates who challenge incumbent judges (Bonneau and Hall 2003, 2009; Bonneau and Cann 2011).

As part of this inquiry, a set of important scholarship has explored a series of questions related to incumbency in judicial elections. These studies have focused primarily on two outcomes: incumbent judges’ electoral success, as measured by reelection rates or vote shares, and the rate at which incumbent judges are challenged. In explorations of incumbent electoral success in state appellate and high court elections, scholars have highlighted challenger quality, partisan electoral systems, and challenger campaign spending as important constraints on an incumbent’s electoral success (Baum 2003; Bonneau 2005; Bonneau and Cann 2011; Streb and Frederick 2009). Studies of challenger entry show that challenges to incumbents arise more often when incumbents won a smaller proportion of the vote in previous elections, were appointees seeking election for the first time, and in partisan and district (rather than statewide) elections (Bonneau and Hall 2003; Hall and Bonneau 2005; Streb and Frederick 2009). Taken together, these studies reveal the institutional and candidate-specific conditions under which voters are more or less likely to be able to and actually choose to hold judges accountable and suggest there is reason to expect a sizable built-in incumbency advantage in judicial elections.

Importantly, however, these measures are conceptually and methodologically distinct from a measure of the incumbency advantage in ways that shape the substantive and normative insight that studies using these measures can provide. Measures such as a high incumbent vote share or reelection rate can be normatively desirable—they can mean, for example, that well-qualified office holders remain in office. These measures could also reflect more normatively troubling conclusion—that incumbents are advantaged solely due to incumbency. Similarly, if an incumbent does not face a challenger, this might be due to the fact that a high-quality incumbent deters challengers, or it might be that incumbency itself is a deterrent to challengers, regardless of incumbent quality. While existing studies and measures thus provide insight into the conditions under which incumbent judges are more and less likely to be held accountable for their behavior in office, and are suggestive of the presence of an incumbency advantage, they do not quantify the incumbency advantage and therefore do not offer direct insight into the extent to which judges are advantaged due solely to being an incumbent. In our study, we look to measure this incumbency advantage directly and therefore clarify the challenges to holding judges accountable for their behavior.Footnote 2

A relatively recent innovation in the study of the incumbency advantage is the use of the regression discontinuity design, in which winning candidates who fall just above the 50% vote threshold are considered, on average, otherwise comparable to losing candidates who fall just below the victory threshold (Lee 2008). This research design avoids the need to specify a strong functional form or employ control variables (such as candidate quality, fundraising ability and partisan strength in the electorate), and allows the researcher to estimate an internally valid causal estimate of the effect of incumbency on subsequent electoral outcomes. Applications of this method have added important insight into the source and nature of the incumbency advantage in a series of electoral contexts in the United States, such as the U.S. Senate (Cattaneo et al. 2015), state legislative elections (Fowler and Hall 2014), and local offices (Trounstine 2011). Despite these recent innovations, scholarship on the incumbency advantage remains focused on legislative and executive elections.

Due to the particular nature of judicial elections, we expect the sources of the incumbency advantage in judicial elections to be of a somewhat different form than that uncovered in other electoral contexts. Cox and Katz (1996) show that the incumbency advantage is composed of two general components—one direct, from the resources afforded to incumbents that can be used in ways that help electoral prospects (e.g., name recognition or legislative staff performing casework), and one indirect, where potential challengers are scared off by the resources of the incumbent. This indirect effect is magnified for high-quality challengers, who have a higher opportunity cost to seeking election. Studies of the incumbency advantage in federal and state legislative settings have found little evidence of a “scare-off” effect, showing that these indirect effects account for less than 30% of the total incumbency advantage (Cox and Katz 1996; Hall et al. 2015).

We expect that any incumbency advantage in judicial elections that we uncover will be driven to a greater extent by the indirect “scare-off" of challengers than in these other electoral settings. First, we expect the opportunity costs to running for judicial office to be particularly high, especially at the lower levels of the judicial hierarchy. The prospective pool of judges are attorneys, a professional class with a higher average earning potential than the potential pool of, say, state legislators.Footnote 3\(^,\)Footnote 4 Another challenge for fielding challengers in judicial elections is candidate recruitment and entry. While many local party chairs report playing a role in recruiting judicial candidates (Streb 2007), the number who do so is less than that for state legislative offices (Gibson et al. 1989). Furthermore, as incumbent judges do not engage in some of the activities that directly help their electoral prospects, such as constituency casework, the relative contribution of the direct effect of incumbency to a judge’s incumbency advantage should be lower than in other electoral settings. Finally, we note that empirical patterns uncovered in existing work—such as how trial court elections are often plagued by limited levels of competition (Nelson 2010)—are consistent with the presence of a scare-off effect.

Data and Methods

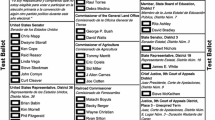

To examine competition in judicial elections, we construct an original dataset of election results for trial court judges that are elected in partisan elections. In our data collection efforts, we endeavored to gather all of the publicly-available data from these elections that we could find. Our full dataset of 5310 races come from six states—Alabama, Indiana, Kansas, Missouri, Texas, and West Virginia—that hold partisan elections and possibly contested partisan elections for incumbents (rather than retention elections) to fill single judicial seats. Our sample consists of trial courts of original jurisdiction with electorates ranging from less than 10,000 to well over 100,000 voters. Our earliest data come from 1988, and the bulk of the data is from 1992 to 2016. Details on our sample of data, including court-specific years and seat counts, can be found in Table 1.Footnote 5 Full summary statistics for our data are in Table B.1 in the Online Appendix.

We focus our attention on these particular elections for four reasons. First, partisan elections are the elections that ought to offer the greatest prospects for accountability and competition at this level of the judicial hierarchy. While most or all state-level judicial elections are low-information environments, party labels carry an important piece of information for voters to use in making a decision (Klein and Baum 2001), thus dramatically increasing the information available for voters to use beyond that in nonpartisan or retention elections. Unlike the latter category, partisan elections also (potentially) pit candidates against each other, increasing the capacity for voters to remove judges from office (Bonneau and Hall 2009). A second motivation for using these data is that little is known about the nature of accountability in lower-level judicial elections, despite the fact that these courts hear the vast majority of cases in the American political system. Additionally, despite being used in more than 20% of states, little systematic descriptive information is known about the partisan breakdown and competitiveness of partisan trial court races (c.f. Nelson 2010). Our study provides both causally-identified evidence of the incumbency advantage as well as new descriptive information to fill this informational gap. Third, the variety of states that compose our sample allow us to be confident that the results we uncover are not driven by a particular state and are generalizable to a wide array of judicial contests.Footnote 6 Finally, focusing on partisan single-member seat elections allows us to use the regression discontinuity design to reliably recover a causally-valid estimate of the (partisan) incumbency advantage.

We structure our data in a seat-by-election panel dataset, where each judicial seat-year is an observation. This allows us to make inferences based on temporally adjacent elections for the same judicial seat.Footnote 7 To illustrate the structure of our data, consider the state of Alabama, in which Circuit Court (Alabama’s trial courts of general jurisdiction) judges are elected in partisan contested elections. Each judicial seat on the Alabama Circuit Court is up for election every 6 years, and judges run for an individual seat. Our seat-by-election panel for the Alabama Third Judicial Circuit, which only has one seat, thus compares election results in this seat for each year an election was held (in our dataset, this is 2004, 2010, and 2016).

Figure 1 plots the Democratic candidate’s share of the vote for the races in our data. In our data, the majority of the races in our sample are uncompetitive. More than 2400 races are uncontested Republican victories and more than 1700 are uncontested Democratic victories. This leaves only 1132 races, or 21% of our sample, as contested. This figure reinforces and extends existing descriptive evidence from trial (Nelson 2010), intermediate (Streb et al. 2007), and state high courts (Hall 2007) about the lack of competition in judicial elections and suggest considerable limitations to judicial accountability at the lowest level of the judicial hierarchy. In addition to showing that most races are not contested, it also indicates that in most races the incumbent party retains the seat. We more formally demonstrate that incumbents enjoy a significant advantage in these elections below.

Empirical Strategy

We use a regression discontinuity design to measure the causal effect of incumbency on subsequent electoral returns in partisan judicial elections. This design is ideal for our application in a number of respects. First, it affords among the highest levels of internal validity across commonly used research designs that measure the incumbency advantage, helping ensure that our estimates accurately characterize the incumbency advantage and are free of potential confounders.Footnote 8 Second, the design is well-suited to the structure of our data: a relatively short panel with a high number of unique units. Other methods to estimate the incumbency advantage generally take advantage of control variables or over-time variation in incumbency status as in a fixed effects design; assembling covariates for geographies as unique and varied as the different court districts in our data would invariably result in high levels of missing data, and the short duration of our panel for most districts makes a within-district design suboptimal. Fortunately, the regression discontinuity design is both better-suited to our data and more credible than these alternative approaches.

The intuition behind the design is straightforward. In a two-party election in the United States, either a Democrat or a Republican will win. In the next election in that same district, that winning party will be the incumbent party. If there is an incumbency advantage, that party will do better in that second election than they would have in the counterfactual circumstance where it had not been the incumbent party. In the regression-discontinuity design, we focus on close elections in the first period, where the two parties were evenly matched, but one narrowly becomes the incumbent party. If there is no incumbency advantage, the parties should perform similarly in the next election; if there is an incumbency advantage, the party that narrowly won the first election should be advantaged in a second election. If we make the plausible assumption that, close to the 50% margin, the winner of the election—and thus incumbency status—is as-if randomly assigned, this design approximates an experiment in which parties are randomly assigned incumbency, and their subsequent electoral performance is compared.Footnote 9 The design helps ensure that winners—who become incumbents—are ex ante comparable to losers on characteristics such as quality; the incumbency advantage it estimates, however, possibly results from a variety of mechanisms, ranging from a simple voter preference for incumbents to now-higher incumbent quality due to learning on the job.

The design is not without limitations. In particular, the quantity estimated by the regression discontinuity design is unique in a number of respects. The RD design estimates the local average treatment effect—the effect of incumbency for units at the cutpoint. Fortunately for our purposes, the effect of incumbency at the 50% threshold is the quantity of greatest substantive interest—if a judge who wins with 70% of the vote enjoys a 5% incumbency advantage in their reelection bid, this is unlikely to affect the election outcome; if, on the other hand, a bare-winner enjoys such an incumbency advantage, this would more plausibly affect their likelihood of victory. A second limitation is that the estimates produced by the RD estimator map only imperfectly into the most common quantity of interest in the study of the incumbency advantage—the so-called “personal incumbency advantage.”Footnote 10 However, we feel the internal validity of the design and its suitability for the structure of our data make the regression discontinuity design the most appropriate for our purposes. Additionally, we show in the Robustness section below that our main results are similar to those obtained when estimating the personal incumbency advantage using an alternative estimation strategy, assuaging concerns about the particularities of the regression discontinuity design.

To estimate the causal effect of incumbency, we use local linear regression, a semi-parametric method with superior performance relative to OLS regression (Gelman and Imbens 2018), using Democratic vote share in time t as our predictor variable and Democratic vote share in the same district and seat in time \(t+1\) as our outcome variable.Footnote 11 We present estimates across a variety of bandwidths, which determine which observations (in terms of distance from the electoral threshold) will be included in the estimation and how they will be weighted. In addition to our primary specification, we perform a variety of robustness checks and extensions, discussed below.

As we mention above, the regression discontinuity design that we employ relies on a key identification assumption: that at the discontinuity, observations are comparable except for the treatment. Intuitively, this allows us to treat the winner of a close election (and therefore the status of being an incumbent) to be as-if randomly assigned, as if in an experiment. Verifying this assumption is important, especially in light of scholarship from Caughey and Sekhon (2011) and Grimmer et al. (2011) that calls into question the validity of the regression discontinuity design in the context of the U.S. House. These studies find evidence of candidate sorting for House elections, whereby better-resourced incumbents appear to be able to “manipulate” their electoral fortunes and systematically eke out close races.Footnote 12 Although Eggers et al. (2015) show that there is little evidence that this is a systematic feature of American electoral politics, it is nevertheless important to establish that this behavior does not occur in the elections under examination in our paper. To do so, in Online Appendix Section A we present evidence from a variety of tests to demonstrate that this assumption is likely to be met in our setting. We take three main approaches to demonstrate the validity of the regression design in our sample. First, we show that incumbents are not able to manipulate their electoral fortunes. Second, we show that there is no effect of crossing other arbitrary electoral thresholds—the effect we identify is unique to comparing near-winners and near-losers. Finally, we demonstrate that there is no effect on lagged outcomes—this suggests that our sample is balanced on overall partisanship and that there are not persistent differences between observations close to but on opposite sides of the discontinuity. Figure 2 plots this relationship visually; formal results are presented in the Online Appendix.

Results

In this section we first present our empirical evidence for our main result: that there is a substantial incumbency advantage in partisan trial court elections. We begin with our baseline results, based on the local linear specification described above. We then present results indicating that our estimated incumbency advantage is in large part due to “scare off,” measured in our case by whether any candidate from the marginal losing party contests the seat in subsequent elections. We then discuss a number of robustness checks and supplementary analyses, results for which are presented in the Online Appendix.

Main Results

We first present our results visually. Figure 3 presents the main analysis: the x-axis is the Democratic vote share in election t and the y-axis plots the Democratic vote share in election \(t+1\). Accordingly, if there were no incumbency advantage, we would expect the smooth fit to proceed unbroken across the discontinuity. As it is, our data reveal a sharp break, with vote shares just to the right of the discontinuity considerably higher than those just to the left. This suggests the existence of a sizable partisan incumbency advantage in our sample of trial court elections. A second takeaway from the figure is that this incumbency advantage appears to be driven largely by non-competitive elections in time \(t+1\); this is initial evidence in support of a scare-off effect. In contested elections in the second period (those with y-axis values between 0 and 1), there does not appear to be much of a gap across the discontinuity; looking at the extreme ranges of the y-axis (those with a vote share of 0 or 1 in time \(t+1\)), however, the dramatic transition in the number of uncontested elections at the cutpoint becomes clear. We explore this explicitly below.

Regression Discontinuity Plot: Partisan Incumbency Advantage in Judicial Elections Note: The figure plots the Democratic two-party vote share in time \(t+1\) on the y-axis against the Democratic two-party vote share in time t on the x-axis. A smooth curve is fit separately on each side of the discontinuity

We present the formal estimation of our main results in Fig. 4. While the purpose of the design is to find the difference in party performance at the discontinuity, we use data from near the discontinuity on either side to estimate this difference using local linear regression. The amount of data used is a function of the bandwidth—a bandwidth of 0.05, for example, indicates that we use only data within 5 percentage points of the threshold for estimation.Footnote 13 As this figure demonstrates, across bandwidths ranging from only half a percentage point to twenty percentage points, our estimation procedure consistently reveals a partisan incumbency advantage of approximately twenty percentage points, and possibly higher.Footnote 14

Estimates of the Partisan Incumbency Advantage in Judicial Elections Note: The figure plots the RD estimates of the incumbency advantage at bandwidths ranging from 0.01 to 0.2 at intervals of 0.01. Bars are 90 and 95% confidence intervals calculated based on seat-clustered standard errors, and numbers indicate the number of effective observations used in each estimation. Estimation undertaken using the RDestimate function from the rdd package in R

Judicial Incumbency’s Scare-Off Effect

Now we consider the degree to which our estimates can be explained through scare-off. While existing studies of the sources of the incumbency advantage in legislative and executive contexts have found limited evidence of a scare-off effect (Cox and Katz 1996; Hall et al. 2015), we expect that the relatively higher opportunity costs to seeking judicial as opposed to legislative or executive office, limitations to challenger entry in trial court elections, and the fact that judicial officeholders do not perform constituency casework should increase the likelihood of a scare-off effect in judicial elections. Existing studies of scare-off focus on challenger quality (Hall et al. 2015). While we lack data on challenger quality, the sizable rate of non-contestation presented in Fig. 3 suggests that substantial scare-off exists in the trial court elections we study by incumbency scaring away any challengers, rather than merely good ones.

To more formally estimate whether incumbency leads to a scare-off effect, we re-estimate our regression discontinuity design with two additional outcome variables: Democrat Running and Republican Running, which simply denote whether a Democrat and a Republican ran in time \(t+1\).Footnote 15 The results are presented in Fig. 5. As these figures make clear, even the narrowest of Democratic victories is associated with a massive swing in the likelihood of a member of both parties running: when a Democrat narrowly wins, there is a 20–30% increase in the probability that a Democrat contests the next election in that district, and a nearly symmetric decrease in the probability that a Republican contests the next election.Footnote 16\(^,\)Footnote 17

Effect of Narrow Democratic Victory on Subsequent Candidate Emergence Note: The figures plot the estimated change in the probability that a Democrat (panel a) or Republican (panel b) runs in the election held in time \(t+1\) after a Democrat won in time t. RD estimates are from bandwidths ranging from 0.01 to 0.2 at intervals of 0.01. Bars are 90 and 95% confidence intervals calculated based on seat-clustered standard errors, and numbers indicate the number of effective observations used in each estimation. Estimation undertaken using the RDestimate function from the rdd package in R

While our main finding parallels and extends scholarship that has uncovered an incumbency advantage across a series of other political offices and jurisdictions, this finding of a sizable scare-off effect shows that the dynamics of the incumbency advantage in judicial elections are unique in the study of American electoral politics. Prior studies that explicitly examine this phenomenon have found relatively little evidence of a scare-off effect across a series of electoral contexts. We document, however, that an overwhelming share of the incumbency advantage in the judicial elections we study is attributable to incumbency’s ability to simply drive off challengers. This is all the more striking when the local nature of the RD estimand is taken into account: these scare-off estimates are not the result of judges who receive 60 or 70% of the vote failing to draw a challenger, but rather those receiving 51 and 52% of the vote. Even in the districts with the most potential for competition, relatively little exists.

This result is particularly incisive in consideration of our motivating normative concern: whether judicial elections are an effective means for holding judges accountable to the wishes of their constituents. Our findings on candidate emergence indicate that incumbency significantly decreases the likelihood that voters have even the opportunity to hold incumbent judges accountable for their behavior. Importantly, our research design ensures that it is solely incumbency—and not ex ante candidate quality—that leads to this accountability deficit.

Robustness

We also employ a number of alternative approaches to estimating the effect of incumbency on subsequent electoral outcomes in trial court elections. A full set and discussion of the results from these alternative strategies are presented in Section B in the Online Appendix. First, we use a variety of alternative estimation strategies. We re-estimate the effect of incumbency using optimal bandwidth calculations and a more sophisticated approach to estimation (Calonico et al. 2020), a de-meaned outcome intended to approximate a fixed effects design, OLS regression, and differences-in-means tests using randomization inference (Cattaneo et al. 2015).Footnote 18 Second, we ensure that no particular part of our sample drives our results by re-estimating the effect of incumbency on subsets of the data. In Fig. 6 we show that the results are quite stable if we remove individual states and re-estimate the incumbency advantage. This leads us to have confidence that our estimates are not a function of our particular sample of states and courts.Footnote 19 We also show that the incumbency advantage was large and positive both before and after 2002, when the Supreme Court decision in Republican Party of Minnesota v. White formally untethered candidates in judicial elections from requirements to avoid making certain political and legal statements when running for office (Gibson 2008).Footnote 20 Taken together, these results provide confidence that our estimates are a reliable characterization of the incumbency advantage in partisan trial court elections.

Estimates of Incumbency Advantage While Iteratively Dropping States Note: Figure presents estimates of incumbency advantage while iteratively omitting each state in our sample. Point estimates are bias-corrected local linear regression estimates and 95% confidence intervals are based on robust seat-clustered standard errors. “BW” is the optimal bandwidth, selected using rdbwselect; “N” is the effective sample size within the optimal bandwidth. All estimation done using rdrobust package in R

Finally, we take an altogether different approach to estimating the incumbency advantage, using panel models to estimate the personal incumbency advantage. We match names within court over time, marking an individual as an incumbent if they won the previous election in that seat.Footnote 21 We use this to create a three-part incumbent indicator, taking a value of 1 for Democratic incumbents, a value of -1 for Republican incumbents, and a value of 0 for open-seat races. We then estimate models with both seat fixed effects (Ansolabehere et al. 2002) and lagged dependent variables (Gelman and King 1990). We discuss the specifications in more detail and present results in Section B.9 in the Online Appendix. In short, the models return estimates that are similar to those in the text, suggesting the existence of an incumbency advantage of approximately 29 percentage points. Because the regression discontinuity estimator actually doubles the incumbency advantage relative to the personal estimators (Erikson and Titiunik 2015),Footnote 22 this suggests that most of the incumbency advantage is a function of individual candidates’ incumbency statuses, rather than a party’s benefit from holding a seat. While these models are only identified under stronger assumptions than our preferred regression discontinuity specifications above, these results affirm the existence of a meaningfully large incumbency advantage in partisan trial court elections.Footnote 23

Implications of a Judicial Incumbency Advantage

Judicial elections provide Americans with an opportunity that citizens in almost every other democracy lack: to hold their judges accountable for their behavior. In this paper, we assess the capacity of judicial elections to serve as a mechanism of accountability. With an extensive dataset of partisan contested elections across over 5300 races in six U.S. states, our study reveals low levels of electoral competition across a series of metrics. Importantly, our empirical strategy—a regression discontinuity design—provides us with leverage to causally identify the electoral advantage that incumbent judges hold due to their status as an officeholder. Our findings show that judges in the American states benefit from a substantial incumbency advantage, with judicial candidates whose party won the previous election estimated to receive over twenty percentage points greater vote totals than those whose party lost the previous election. The magnitude of this incumbency advantage is comparable to or larger than that estimated in other electoral contexts. Unique to judicial elections, however, is the scare-off effect we uncover in our study. In contrast to studies in other electoral settings, we find that a narrow victory considerably decreases the odds that an incumbent judge will be faced with a challenger in the subsequent election. This suggests that scare off, rather than other, possibly less normatively troubling mechanisms (Eggers 2017), leads to the sizable incumbency advantage in these judicial elections. Importantly, our results are robust across states, office types, time periods, and a series of alternative methodological specifications. We hope that future work will explore other possible moderating factors, such as party competition, which might be expected to suppress the benefits of incumbency at either very narrow or very wide margins, and which waxes and wanes to meaningful degrees across states and time.

We conclude with a consideration of the consequences of our findings and possibilities for further research. Our findings reveal a limited level of competition in the elections for the trial courts in our study. In this way, our findings shed light on the ongoing debate over whether, and how, American judges should be elected. Proponents of judicial elections proffer numerous arguments in support of electing judges, but perhaps the most important of these is that elections serve as a mechanism of accountability for officials who make political decisions. Accountability is particularly important for trial court judges, as they are responsible for the overwhelming majority of decisions issued by state courts. Our findings reveal important limitations in this accountability mechanism. As we show descriptively, only 21% of the races in our dataset are contested, a significantly lower number than the 90% of partisan state high court elections that are contested (Bonneau and Hall 2009). Our estimate of the incumbency advantage—approximately 20 to 30 percentage points—is substantively impressive and reveals important limitations to the ability of Americans to effectively sanction their judges. That we uncover this sizable incumbency advantage in partisan elections—those most likely to be competitive—suggests the capacity for judges to be held accountable is possibly even more limited in judicial settings with alternative electoral rules, such as nonpartisan and retention systems. Indeed, the scare-off effect we find signifies that trial court partisan elections are unable to consistently provide opportunities for voters to hold their elected officials accountable. Given the importance of challenger entry for providing voters with alternatives to incumbents and allowing the most qualified candidates to hold office, the scare-off effect present in trial court elections inhibits accountability.

However, we wish to strike a note of caution in drawing normative conclusions about the merits of judicial elections, even in light of the large incumbency advantage our study reveals. First, although our findings reveal the challenges to holding judges accountable through electoral means, the value of judicial elections should be considered in light of the alternative institutional arrangements used to select judges. In other words, would a counterfactual appointment system be a net benefit or loss for judicial accountability? Despite their flaws, judicial elections still provide the public with the capacity to directly select and remove their judges. This stands in contrast to appointment systems, where opportunities for removal are rare and preferences must be transmitted through other political officials—institutional hurdles that can introduce slippage into the representation relationship between the public and judges (e.g., Brace and Boyea 2008).

Institutional change can happen, however, within an electoral system. The high incumbency advantage we quantify suggests the potential for reforms to lessen the incumbency advantage and improve the capacity of the public to hold elected judges accountable. Initiatives to improve candidate entry and competitiveness, such as public funding programs (see discussion in Bonneau and Kane 2016), as well as to improve public knowledge of judicial elections and candidates, such as loosening restrictions on campaign spending (Bonneau and Hall 2009), may provide opportunities for reducing the incumbency advantage we uncover. Nevertheless, these reforms too introduce tradeoffs. It is worth considering the potential positives associated with sustained incumbency even if it inhibits accountability—particularly as it relates to the judiciary. The start-up costs necessary to adjust to life on the judicial bench mean that newcomer judges may be less efficient, more ideologically inconsistent, and more deferential to their colleagues than senior judges (Hagle 1993; Hettinger et al. 2003). Voters might therefore very reasonably prefer an incumbent judge to a more ideologically-proximate challenger. In addition, given the importance of productivity and caseload management in the judiciary, particularly in the often-understaffed lower courts (Resnik 1982), experience on the bench could improve the day-to-day function of the institution. Moreover, judges in the courts we analyze may face a relatively “practical,” rather than ideological, caseload, thus downplaying the role of ideology in the choice voters face. This is in marked contrast to discussion of the incumbency advantage in legislative elections, where competition between candidates from ideologically distinct, programmatic parties is often normatively valued. Finally, electoral pressures may generate incentives that lead to punitive or discriminatory sentencing behavior (Huber and Gordon 2004; Park 2017). Taken together, these factors suggest that even a sizable incumbency advantage may provide benefits. Future research should endeavor to quantify the gains from incumbency and weigh them against the increased levels of accountability and competition that a lesser incumbency advantage would bring to judicial elections.

In closing, we note that our analysis has some key limitations. Our focus on partisan, trial court, single-seat competitive elections provides a stringent test for the incumbency advantage in judicial elections and allows us to apply conventional methods to estimate the incumbency advantage in these settings. Left unexamined, however, are a rich array of judicial electoral institutions—nonpartisan elections, retention elections, high courts—each with unique mechanisms that shape the ability of the electorate to hold judges accountable for their behavior. Future studies should explore competition and the incumbency advantage in greater depth in these electoral settings, especially considering that many of these alternative institutional characteristics may well increase the barriers to entry for non-incumbent judges. Relatedly, given the high degree of competition documented in many state high court elections (Hall and Bonneau 2005; Hall 2007), studies of the role of incumbency in these elections may reveal different patterns than we uncover in our analysis.

Notes

The National Center for State Courts reports that over 99.5% of case filings in the American states in 2016 were at the trial court level: https://perma.cc/VY8L-PX33.

As Lee (2001, pp. 4–6) describes, speaking about the U.S. House: “[I]ncumbent candidates... enjoy a high electoral success rate... The casual observer is tempted to take [this] as evidence that there is an electoral advantage to incumbency... But winning candidates prevailed over their opposition for various reasons. Perhaps they are more charismatic, or they had more campaign resources... Establishing whether or not the differences in electoral outcomes between incumbents and non-incumbents represent a true causal effect or a simple artifact of selection is important first step to assessing the empirical relevance of theories that adopt a principal-agent approach to modeling politician-voter interactions”.

For example, roughly 37% of state legislators have a graduate degree, including the 15% with law degrees (Zoch 2020). Additionally, as many state legislatures only meet part time, legislators in these states face a relatively low opportunity cost to holding office.

Importantly, however, this disparity in opportunity costs may be reduced if the types of lawyers that select into running for judicial office have different career goals or face lower opportunity costs than the broader pool of attorneys. Indeed, Williams (2008) shows that women view the judiciary as providing greater opportunities for advancement than legal practice, which may help explain why women exhibit greater ambition for judicial as opposed to legislative office.

For many courts, especially high courts, multiple seats are elected at one time, complicating an RD analysis of incumbency. As we focus on trial courts, we do not include data from elections in Michigan or Ohio, nonpartisan election states that have a hybrid system for electing their high court judges that contains aspects of partisan systems (Nelson et al. 2013).

We formally test this claim below. One benefit of looking at multiple states is that we can generalize across states with a variety of levels of two-party competition. As Dumas (2011) finds evidence that judges in Alabama strategically switch parties in response to changing electoral alignments in their constituencies, drawing upon a variety of states helps guard against this behavior systematically shaping our findings.

We focus throughout the paper on the two-party vote share. We omit any race in which third-party, independent, or write-in candidates received more than 15% of the vote.

A particular concern is that incumbents may be strategic in their decision to run (or not run) for reelection. In our sample, 76.2% of all races feature an incumbent. Descriptively, there is little indication that those who won by narrow margins are less likely to seek reelection (see Fig. B.1 in the Online Appendix).

While this “local randomization” assumption is sufficient for causal identification in the regression-discontinuity framework, it is actually a stronger assumption than is required (de la Cuesta and Imai 2016).

In particular, the regression discontinuity design compares a Democratic incumbent to the counterfactual of a Republican incumbent—not “no incumbent” as a traditional regression model might—so the estimates produced represent the effect of a different change in incumbency status than those models. Additionally, the estimator focuses only on whether a party is the incumbent party, and ignores whether a given judge actually chooses to stand for reelection.

We implement the design using the RDestimate function from the rdd package in R.

Nevertheless, de la Cuesta and Imai (2016) illustrate how the regression discontinuity design may still be valid in the case of the U.S. House. In particular, the authors show that the evidence for the violation of this assumption is dependent on model selection and weakens when correcting for multiple testing.

We use a triangular kernel, which weights data closer to the threshold more highly than that further away.

We also present estimates at the “optimal bandwidth” using the bias-corrected point estimate and robust inference suggested by Calonico et al. (2020) in Table B.2. The estimate using this procedure is 0.258.

Hall et al. (2015) perform a similar test.

As with our main result, in the Online Appendix we present placebo tests using lagged outcomes for this analysis (see Fig. A.4).

If we limit our sample to contested elections—and thus make the exceedingly strong assumption that elections are contested without regard to the incumbent’s strength—we find that our estimated incumbency advantage all but disappears (see Fig. B.2 in the Online Appendix).

These results are presented in Table B.2, Fig. B.3, Fig. B.4, and Table B.3, respectively.

In particular, these results show that our findings are consistent across states with different levels of two-party competition.

See Fig. B.5.

We rely on last names for an initial match, and then when possible we check full names to avoid false matches.

The regression discontinuity estimates are for the comparison between a Democratic incumbent and a Republican incumbent; the panel models compare an incumbent to a reference category of no incumbent.

We also use this personal incumbency advantage design in order to compare the incumbency advantage for elected versus appointed incumbents. The results, presented in Table B.5, indicate that while being an appointed incumbent does not completely attenuate the incumbency advantage, it does diminish it between five and ten percentage points, consistent with existing scholarship (e.g., Bonneau 2005; Streb and Frederick 2009).

References

Ansolabehere, S., & Snyder, J. M., Jr. (2002). The incumbency advantage in U.S. elections: An analysis of state and federal offices, 1942–2000. Election Law Journal, 1(3), 315–338.

Ashworth, S., Bueno, E., & de Mesquita. (2008). Electoral selection, strategic challenger entry, and the incumbency advantage. The Journal of Politics, 70, 1006–1025.

Baum, L. (1983). The electoral fates of incumbent judges in the Ohio court of common pleas. Judicature, 66(9), 420–430.

Baum, L. (2003). Judicial elections and judicial independence: The voter’s perspective. Ohio State Law Journal, 64, 13.

Bonneau, C. W. (2005). Electoral verdicts: Incumbent defeats in state supreme court elections. American Politics Research, 33(6), 818–841.

Bonneau, C. W., & Cann, D. M. (2011). Campaign spending, diminishing marginal returns, and campaign finance restrictions in judicial elections. The Journal of Politics, 73(4), 1267–1280.

Bonneau, C. W., & Hall, M. G. (2003). Predicting challengers in state supreme court elections: Context and the politics of institutional design. Political Research Quarterly, 56(3), 337–349.

Bonneau, C. W., & Hall, M. G. (2009). In defense of judicial elections. New York: Routledge.

Bonneau, C. W., & Kane, J. B. (2016). Proposals for reforms. In C. W. Bonneau & M. Gann Hall (Eds.), Judicial elections in the 21st century (pp. 249–261). New York: Routledge.

Brace, P., & Boyea, B. D. (2008). State public opinion, the death penalty, and the practice of electing judges. American Journal of Political Science, 52(2), 360–372.

Calonico, S., Cattaneo, M. D., & Farrell, M. H. (2020). Optimal bandwidth choice for robust bias-corrected inference in regression discontinuity designs. The Econometrics Journal, 23(2), 192–210.

Cattaneo, M. D., Frandsen, B. R., & Titiunik, R. (2015). Randomization inference in the regression discontinuity design: an application to party advantages in the U.S. senate. Journal of Causal Inference, 3(1), 1–24.

Caughey, D., & Sekhon, J. S. (2011). Elections and the regression discontinuity design: Lessons from close U.S. house races, 1942–2008. Political Analysis, 19(4), 385–408.

Cox, G. W., & Katz, J. N. (1996). Why did the incumbency advantage in U.S. house elections grow? American Journal of Political Science, 40(2), 478–497.

de Benedictis-Kessner, J. (2017). Off-cycle and out of office: Election timing and the incumbency advantage. Journal of Politics, 80(1), 119–132.

de la Cuesta, B., & Imai, K. (2016). Misunderstandings about the regression discontinuity design in the study of close elections. Annual Review of Political Science, 19, 375–396.

Dubois, P. L. (1980). From ballot to bench: Judicial elections and the quest for accountability. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Dumas, T. L. (2011). Community preferences and trial court decision-making: The influence of political, social, and economic conditions on litigation outcomes. Dissertation: Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College.

Eggers, A. C. (2017). Quality-based explanations of incumbency effects. The Journal of Politics, 79(4), 1315–1328.

Eggers, A. C., Fowler, A., Hainmueller, J., Hall, A. B., & Snyder Jr, J. M. (2015). On the validity of the regression discontinuity design for estimating electoral effects: New evidence from over 40,000 close races. American Journal of Political Science, 59(1), 259–274.

Erikson, R. S. (1971). The advantage of incumbency in congressional elections. Polity, 3(3), 395–405.

Erikson, R. S. (2017). The congressional incumbency advantage over sixty years: Measurement, trends, and implications. In A. S. Gerber & E. Schickler (Eds.), Governing in a polarized age. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Erikson, R. S., & Titiunik, R. (2015). Using regression discontinuity to uncover the personal incumbency advantage. Quarterly Journal of Political Science, 10(1), 101–119.

Fiorina, M. P. (1989). Congress: Keystone of the Washington establishment. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Fowler, A., & Hall, A. (2014). Disentangling the personal and partisan incumbency advantages: Evidence from close elections and term limits. Quarterly Journal of Political Science, 9(4), 501–531.

Gelman, A., & Imbens, G. (2018). Why high-order polynomials should not be used in regression discontinuity designs. Journal of Business& Economic Statistics, 37(3), 447–456.

Gelman, A., & King, G. (1990). Estimating incumbency advantage without bias. American Journal of Political Science, 34(4), 1142–1164.

Geyh, C. G. (2003). Why judicial elections stink. Ohio State Law Journal, 64, 43–79.

Gibson, J. L. (2008). Challenges to the impartiality of state supreme courts: Legitimacy theory and “New Style’’ Judicial Campaigns. American Political Science Review, 102(1), 59–75.

Gibson, J. L., Frendreis, J. P., & Vertz, L. L. (1989). Party dynamics in the 1980s: Change in county party organizational strength, 1980–1984. American Journal of Political Science, 33(1), 67–90.

Grimmer, J., Hersh, E., Feinstein, B., & Carpenter, D. (2011). Are close elections random? Unpublished Manuscript .

Hagle, T. M. (1993). Freshman effects’ for supreme court justices. American Journal of Political Science, 37(4), 1142–1157.

Hall, A. B., & Snyder, J. M., Jr. (2015). How much of the incumbency advantage is due to scare-off? Political Science Research and Methods, 3(3), 493–514.

Hall, M. G. (2007). Competition as accountability in state supreme court elections. In M. J. Streb (Ed.), Running for judge: The rising political, financial, and legal stakes of judicial elections. New York: New York University Press.

Hall, M. G. (2007). Voting in state supreme court elections: Competition and context as democratic incentives. Journal of Politics, 69(4), 1147–1159.

Hall, M. G., & Bonneau, C. W. (2005). Does quality matter? Challengers in state supreme court elections. American Journal of Political Science, 50(1), 20–33.

Hall, M. G., & Bonneau, C. W. (2008). Mobilizing interest: The effects of money on citizen participation in state supreme court elections. American Journal of Political Science, 52(3), 457–470.

Hettinger, V. A., Lindquist, S. A., & Martinek, W. L. (2003). Acclimation effects and separate opinion writing in the U.S. courts of appeals. Social Science Quarterly, 84(4), 792–810.

Huber, G. A., & Gordon, S. C. (2004). Accountability and coercion: Is justice blind when it runs for office? American Journal of Political Science, 48(2), 247–263.

Jacobson, G. C. (2015). It’s nothing personal: The decline of the incumbency advantage in U.S. house elections. Journal of Politics, 77(3), 861–873.

King, G., & Gelman, A. (1991). Systematic consequences of incumbency advantage in the U.S. house elections. American Journal of Political Science, 35(1), 110–138.

Klein, D., & Baum, L. (2001). Ballot information and voting decisions in judicial elections. Political Research Quarterly, 54(4), 709–728.

Lee, D. S. (2001). The electoral advantage to incumbency and voters’ valuation of politicians’ experience: A regression discontinuity analysis of elections to the U.S. house. National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper. Retrieved from https://perma.cc/Q3CM-4FFX (August).

Lee, D. S. (2008). Randomized experiments from non-random selection in U.S. house elections. Journal of Econometrics, 142(2), 675–697.

Levitt, S. D., & Wolfram, C. D. (1997). Decomposing the sources of incumbency advantage in the U. S. house. Legislative Studies Quarterly, 22(1), 45–60.

Nelson, M. J. (2010). Uncontested and unaccountable-rates of contestation in trial court elections. Judicature, 94, 208.

Nelson, M. J., Caufield, R. P., & Martin, A. D. (2013). Oh, Mi: A note on empirical examinations of judicial elections. State Politics& Policy Quarterly, 13(4), 495–511.

Park, K. H. (2017). The impact of judicial elections in the sentencing of black crime. Journal of Human Resources, 52(4), 998–1031.

Powell, G. B. (2000). Elections as instruments of democracy: Majoritarian and proportional visions. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Resnik, J. (1982). Managerial judges. Harvard Law Review, 96, 374.

Streb, M. J. (2007). Partisan involvement in partisan and nonpartisan trial court elections. In M. J. Streb (Ed.), Running for judge: The rising political, financial, and legal stakes of judicial elections (pp. 96–114). New York: New York University Press.

Streb, M. J., & Frederick, B. (2009). Conditions for competition in low-information judicial elections: The case of intermediate appellate court elections. Political Research Quarterly, 62(3), 523–537.

Streb, M. J., Frederick, B., & LaFrance, C. (2007). Contestation, competition, and the potential for accountability in intermediate appellate court elections. Judicature, 91, 70.

Trounstine, J. (2011). Evidence of a local incumbency advantage. Legislative Studies Quarterly, 36(2), 255–280.

Williams, M. S. (2008). Ambition, gender, and the judiciary. Political Research Quarterly, 61(1), 68–78.

Zoch, A. (2020). The ‘Average’ state legislator is changing, slowly. National conference of state legislatures. Retrieved from https://perma.cc/85LY-7UNH.

Acknowledgements

We thank Eric Beerbohm, Benjamin Kassow, Claire Lim, Abigail Matthews, Scott Peters, Jim Snyder, and participants in the poster session of the 2018 Toronto Political Behaviour Workshop for helpful comments, suggestions, and assistance. Previous versions of this paper were presented at the 2019 Annual Meeting of the Southern Political Science Association and the 2019 Annual Meeting of the Midwest Political Science Association

Funding

No funding was received to assist with the preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Replication Data

Replication data and code can be found in the Political Behavior Dataverse at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/7IW6JF.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Olson, M.P., Stone, A.R. The Incumbency Advantage in Judicial Elections: Evidence from Partisan Trial Court Elections in Six U.S. States. Polit Behav 45, 1333–1354 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-021-09764-0

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-021-09764-0