Abstract

We analyze current account imbalances through the lens of the two largest surplus countries; China and Germany. We observe two striking patterns visible since the 2007/8 Global Financial Crisis. First, while China has been gradually reducing its current account surplus, Germany’s surplus has continued to increase throughout and after the crisis. Second, for these two countries, there is a remarkable reversal in the patterns of exchange rate misalignment: China’s currency has turned from being undervalued to overvalued, Germany’s currency has erased its level of overvaluation and become undervalued. Our empirical analyses show that the current account balances of these two countries are quite well explained by currency misalignment, common economic factors, and country-specific factors. Furthermore, we highlight the global financial crisis effects and, for Germany, the importance of differentiating balances against euro and non-euro countries.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

In recent years, large and sustained current account imbalances have been a focus of research in international economics. While there is a large literature on deficits and their economic implications (Cavallo et al. 2017), there is only limited research on large and sustained surpluses.Footnote 1 This is surprising in the light of a longstanding concern, for instance stressed by Keynes (1941) and Kaldor (1980), about the role of surplus countries in international adjustments. More recently, Christine Lagarde, the IMF’s managing director, aptly pointed out the link between deficits and surpluses when she said: “It takes two to tango.”Footnote 2 The deficits of some countries are matched by surpluses in others, and it is important to understand both phenomena.

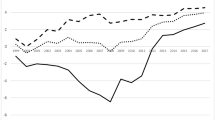

China and Germany are two prime examples of net exporters that have experienced large and sustained surpluses over the past 20 years; in 2015, they accounted for 42% of the world’s total surplus.Footnote 3 As Fig. 1 shows, Germany and China are unparalleled in their current account surpluses, even compared to other stereotype surplus economies, such as Japan, Korea, and Switzerland.Footnote 4

Aizenman and Sengupta (2011) is one of the few studies that investigated whether China and Germany have different causes of current account imbalances and their responses.Footnote 5 At the time of their writing, these authors observed China’s strong growth in surpluses, raised the question of whether “China is becoming the new Germany,” and concluded that the answer is likely to be a “no.”

In the current study, we update and extend the comparison of China and Germany. We illustrate that, during the post-global financial crisis (GFC) period, the two countries have displayed dis-similar current account behaviors (Fig. 2). While both countries have been running current account surpluses for most years over the past two decades, China’s surplus has started to shrink after the GFC. Germany’s current account surplus has, in contrast, stayed at a high level and even experienced a steady increase. Apparently, the current account balances of these two surplus countries exhibit a similar pattern before the GFC but have moved in different directions thereafter.

We investigate whether this new development is due to a “crisis effect” or the usual economic forces. Specifically, what is the role of exchange rate misalignment in determining the current account balances of these two surplus countries? Do these two countries display a similar pattern of exchange rate misalignment? We indeed observe that, although not often discussed by academics and policy makers, their exchange rate misalignment patterns have strikingly changed since 2007.Footnote 6

It is commonly believed that China has maintained an undervalued exchange rate,Footnote 7 whereas Germany has an overvalued one.Footnote 8 Figure 3, however, shows that in recent years, the valuations of these two currencies move in opposite directions according to estimates provided by the Centre d’Études Prospectives et d’Informations Internationales (CEPII). Specifically, these currency misalignment estimates show that the Chinese level of misalignment has been diminishing noticeably since 2007. Since 2012, the Chinese currency is better characterized as being overvalued than undervalued.Footnote 9 In Germany, the reverse pattern holds. Since the implementation of labor market reforms (“Agenda 2010” – see Sinn 2007 and 2014) in the early 2000s, Germany has considerably improved its competitive position vis-à-vis its trading partners, in particular within the euro area.Footnote 10 The currency’s degree of overvaluation has been declining accordingly and, finally, turned to an undervaluation in 2015, when the quantitative-easing policy of the European Central Bank contributed further to this development. Visually, these currency misalignment and current account balance movements are in line with the conventional wisdom that these two variables are inversely related.

Against this backdrop, we estimate the current account equations for both countries and assess the similarities and differences of the Chinese and German behaviors. For this purpose, we not only analyze the role of currency misalignment but also the effects of a wide range of explanatory variables.Footnote 11 These variables include canonical economic factors, monetary factors, and global factors. In addition, we analyze country-specific factors to capture effects of, for example, China’s liberalization policies and euro area specific institutional factors for Germany.Footnote 12

For both countries, currency misalignment plays a significant role in determining the current account balance. While for Germany, the effect is present over the whole sample period, we find that for China it became important after the global financial crisis of 2007/8. While the exact quantitative effect varies a bit with empirical specifications, the qualitative results on the currency misalignment effect, the post-crisis impact, as well as on other control variables taken from the literature, are robust to the choice of alternative measures of currency misalignment, the inclusion of different sets of control variables, and a seemingly unrelated regression specification. That is, our empirical findings buttress the negative correlation pattern observed from Figs. 1 and 2.Footnote 13

The currency misalignment variable together with selected canonical economic factors, monetary factors, global factors, and country-specific factors can explain over 90% of variations in the current account balances of these two countries. This high explanatory power implies that policy makers – should they decide to steer the current account in either direction – have the information and power to do so, based on the empirical knowledge of the underlying determinants.

Is China the new Germany? One could say that China is evolving towards the “old” Germany that was an overvalued exporter experiencing a moderate surplus. Germany, on the other hand, is becoming a country with increasing surpluses, both within the euro area and with respect to the rest of the world, with an undervalued exchange rate. In both cases, the surplus can be attributed to currency misalignment and other economic factors.

2 Empirical Analysis

2.1 Basic Specification

The behaviors of the Chinese and German current account balances are investigated using the following empirical specification, inspired by Aizenman and Sengupta (2011):Footnote 14

The dependent variable Yt is the current account balance normalized by gross domestic product. CM denotes the currency misalignment and C07 the post-GFC dummy variable. The other explanatory variables that are common to the China and Germany specifications are collected under θt − 1, they include canonical economic variables and monetary and global factors. All explanatory variables enter the model with lagged values to minimize potential endogeneity. A lagged term of the current account is included to capture any remaining autocorrelation. The regression exercise is based on annual data from 1982 to 2016.Footnote 15

The data on currency misalignment are drawn from the “EQCHANGE” database provided by the French CEPII. Currency misalignment (CM) is defined as the relative deviation of the real effective exchange rate (REER) from its estimated equilibrium value based on fundamental variables. Estimated equilibrium exchange rates are based on a worldwide panel regression explaining the REER by information on (i) relative sectoral productivity (Balassa-Samuelson effect), (ii) the country’s net foreign asset position (intertemporal budget constraint), and (iii) the economy’s terms of trade (income and substitution effect). The estimated coefficients are then used to predict an individual country’s equilibrium exchange rate. The CEPII’s currency misalignment estimates are highly correlated with those provided by the IMF or Brussels European and Global Economic Laboratory (Bruegel).Footnote 16

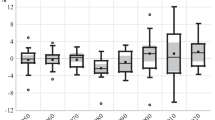

Two things are noteworthy about the data: First, the CEPII’s CM estimates are not technically linked to a “balanced” current account, and thus do not induce endogeneity in the regression. This is in contrast to the early currency misalignment literature, originating from Williamson (1983), which first proposed the concept of an equilibrium exchange rate that is compatible with a balanced (or any another normatively preferred) current account.Footnote 17 Second, estimates of currency misalignment are known to come with a considerable degree of estimation uncertainty (for instance, Cheung et al. (2007, 2009), Qin and He (2011), Garroway et al. (2012)). In Section 3.1, we therefore test the sensitivity of our results using alternative measures of currency misalignment from the literature.

We have included a large collection of determinants that are motivated by a multitude of theoretical and empirical considerations.Footnote 18 In addition to currency misalignment, we consider the effects of canonical economic variables, monetary variables, and global factors. The set of canonical economic variables consists of the age dependency ratios (young, old), the government balance, domestic GDP growth, changes in de-facto trade openness, as well as the US current account, excluding China and Germany. Monetary variables include – next to the currency misalignment – the change in domestic credit. The global factors consist of the world GDP growth rate and the US current account, excluding China and Germany. For these variables and others used in the subsequent analyses, additional information including their sources is provided in Appendix Table 6.

To operationalize an empirical strategy, we first assess the effects of the explanatory variables jointly before eliminating insignificant variables in a stepwise regression approach to form the selected parsimonious specification.

Initially, we estimate the current account balance eq. (1) separately for the Chinese and German data using ordinary least squares. Then, we adopt the feasible generalized least squares (FGLS) approach to generate estimates of a Seemingly Unrelated Regression (SUR) model comprising the Chinese and German current account balance equations (Aizenman and Sengupta 2011).

In anticipating these two surplus countries can display considerable differences in the determinants of their current account positions, and in their behaviors after the GFC, we in subsection 3.2 investigate the role of country-specific factors (and the possible limitation of a one-size-fits-all approach) in determining China’s and Germany’s current account behaviors and the effect of the GFC. Specifically, for the German case, we evaluate the importance of differentiating balances against euro and non-euro countries; a point that is not typically considered by existing studies.

2.2 Empirical Results

Table 1 presents the results of our baseline regression. Columns (1) and (3) report the results when all variables are included jointly, and Columns (2) and (4) display the results after dropping insignificant variable from the regression. The empirical findings include several points that are noteworthy.

First, currency misalignment is a significant determinant – undervaluation (overvaluation) tends to improve (deteriorate) current account balance. The finding is in accordance with theoretical considerations, although China and Germany have different post-crisis experiences.

The Chinese currency misalignment effect is much stronger in the post-GFC sample – a period in which China has stepped up its financial market reform. This post-crisis effect is independent of the specific crisis year chosen (2007/8/9).Footnote 19 The insignificant effect observed before the GFC, while not in line with the political debate and media commentaries, is not at odds with the academic studies that report difficulties of modeling China’s trade equations and assessing the degree of the RMB misalignment. For instance, it is usually found that the Chinese exports and imports do not follow the textbook exchange rate effects and do not empirically satisfy the Marshall-Lerner condition – that is, a strong RMB does not necessarily reduce surpluses (Cheung et al. 2012; Marquez and Schindler 2007).Footnote 20 Further, it is reported that the Renminbi misalignment estimate can span a wide range that covers both under- and overvaluation (Bineau 2010; Cheung and He 2019). These findings, which are typically attributed to China’s heavy-handed approach, imply that the link between currency misalignment and the current account surpluses is weak. As discussed above, China has adopted a more market-oriented approach after the GFC; thus, it is more likely to reveal and observe the link in the later part of the sample.

Germany, in contrast, does not experience a significant change in its currency misalignment effect. Apparently, the crisis experience does not affect the dynamics of German current account balance; both the Crisis07 and its interaction term are not significant in the German equation. The result suggests that the overvaluation prior to 2007 may have constrained the current account balance from becoming even larger, and the post-crisis undervaluation has induced further increases in the surplus.

Second, the Chinese and German current account balance equations have some other common explanatory factors, though these factors can exhibit different effects. For China, we find that the lagged old-age dependency ratio is significant. For Germany on the other hand, in the parsimonious specification, the young-age dependency ratio is statistically significant at the 5% level.Footnote 21 The young-age (Germany) and old-age (China) dependency ratios have opposite signs; a remarkable pattern that remains throughout the paper.Footnote 22 Most studies refer to Modigliani’s life-cycle hypothesis and expect a dissaving behavior of the youngest and oldest members of the society. This implies a negative coefficient of the dependency ratios – as we indeed confirm in the case of the young-age dependency ratio for Germany. The positive old-age dependency effect for China, in contrast, can be an exemplification of non-typical life-cycle behaviors. The saving behavior may be modified when the life expectancy increases as, say, the quality of healthcare improves, under a low-interest rate environment. The increasing life expectancy (and the accompanying increase in old-age dependency) can induce saving to meet retirement needs (Li et al. 2007; Cooper 2008). Cheung et al. (2016) finds that the interest rate affects private saving negatively if the old-age dependency ratio exceeds a certain threshold.Footnote 23 The precautionary savings channel may be especially relevant for China, as life expectancy increased by 8.6 years (12.8%) over the sample period.Footnote 24

Another common determinant of the two countries is the lagged domestic GDP growth, which displays a negative partial correlation with the current account balance. While it is indeed expected to observe a negative influence, mixed empirical results are reported in earlier empirical studies (Chinn and Prasad 2003; Gruber and Kamin 2007; Ca’Zorzi et al. 2012).

Also, the lagged current account variable is significant for both countries, which reflects the gradual changes that have occurred in recent years as visible in Fig. 2. For China, the post-2007 dummy variable is significant by itself, capturing the decline in surpluses after the beginning of the GFC.

Third, there are some factors that affect the Chinese (German) current account but not the German (Chinese) one.Footnote 25 Specifically, China but not Germany is affected by the government budget balance. On the other hand, Germany is affected by world GDP growth, but not China.Footnote 26 Further studies are warranted to investigate the causes of these differences.

Fourth, the bulk of current account balance variability is accounted for by the selected parsimonious specifications; 74% and 91% of the variations in China’s and Germany’s current account surpluses are explained. That is, the surpluses experienced by these two countries have roots in economics, and, if desired, these imbalances can be corrected with appropriately designed policies.

2.3 Other Monetary and Global Factors

In Table 2, we analyze the roles of other monetary and global factors, which are not part of the standard set of control variables in other studies. Starting from the significant variables in Table 1, we add the lagged change in M3 and M1, both domestically, as wells as in the US and in the world’s aggregate. Furthermore, we add the real interest rate, inflation rate, and the oil price.

As Table 2 shows, for China, there are only two further significant factors; the domestic change in M3 and domestic inflation. For Germany, on the other hand, the domestic change in M1 and the real interest rate are statistically significant at the 1% and 5% level, respectively.Footnote 27 In both countries, these variables appear to have complementary power in explaining current account balance, as these additional factors do not crowd out the impact of exchange rate misalignment, and they improve the model explanatory power over the specification in Tables 1 to 80% (China) and 94% (Germany), respectively. In fact, for China, the additional variables sharpen the picture and allow us to illustrate the currency misalignment effect also for the pre-2007 period, although only at the 10% level.

Interestingly, both countries’ current account balances do not react significantly to the US money growth; In the post-GFC period, the US money supply increase followed the quantitative-easing policy reflects a weak US (and global) economy, which in principle can shrink the Chinese and German current account surpluses.

The Chinese and German current account behaviors might be driven by some common forces that induce correlation between the Chinese and German regression equations. To exploit this information, we adopt a SUR framework for the two current account balance equations and estimate it using FGLS. While the coefficient estimates reported in Table 3 are largely comparable to the corresponding values in Table 2, they are expected to be more precisely estimated. Comparing the parameters, we do not observe substantial differences in the magnitude of the coefficients or the significance levels. However, the SUR estimates give an even better explanatory power; especially for the Chinese case, in terms of the goodness of fit measure.Footnote 28

Overall, for both the Chinese and German cases, the number of significant canonical economic variables is relatively larger than those of the monetary and global factors. That is, the usual economic reasoning is still a relevant framework for understanding current account dynamics.

3 Additional Analyses

A few additional regressions are performed to assess the robustness of the empirical results presented in the previous section.Footnote 29

3.1 Alternative Measures of Misalignment

The currency misalignment variable used in the previous section is one of the misalignment variables compiled by CEPII. In constructing misalignment measures, CEPII considers different combinations of choices of fundamental variables, trading partners, and country weights. The misalignment variable used in the previous section is derived from three fundamental determinants and a broad group of 186 trade partners with fixed trade weights (see Section 2.1 for a more detailed description). In Table 4, we check the sensitivity of our results regarding the choice of the methodology used to estimate currency misalignment. First, we replace it with those CEPII estimates derived from fixed trade weights based on the most recent 5-years. Second, we consider the measure of Cheung et al. (2017), which is based on the well-known “Penn-effect” (the linear version, by income group).Footnote 30 Finally, we take the standard real effective exchange rate as a control variable, as computed by the International Financial Statistics of the IMF.Footnote 31

Table 4 shows that with minor exceptions, the use of alternative currency misalignment variables does not qualitatively change the estimation results; especially, the pre- and post-GFC coefficient estimates of alternative currency misalignment measures are quite similar. The alternative currency misalignment variable by Cheung et al. (2017), based on the Penn-effect, display coefficient estimates with the same signs, a broadly similar order of magnitude and statistical significance level. Also, the adjusted R2 estimates are quite similar to the previous tables. Our benchmark specification is chosen, as it has the largest number of observations and it is available for a broad spectrum of countries from the CEPII institute.

The robustness test with the real exchange rate as a dependent variable, which also yields similar results, indicates that the CM-effect is largely driven by changes in the observed real exchange rate itself, and probably only to a lesser extent to changes in the equilibrium exchange rate or its determinants. Table 8 of the Appendix follows up on this interpretation and shows that for both, China and Germany, the real effective exchange rate is a highly significant determinant of the CEPII currency misalignment estimate (significant at the 1% level in Columns (1) to (4)). As further control variables in this regression, we include either the (estimated) equilibrium exchange rate, or the components relied upon in its estimation, i.e. the relative productivities (capturing the Balassa-Samuelson Effect), the terms of trade (capturing income and substitution effects) and the net foreign asset position (as a proxy for the intertemporal budget constraint). The four regressions in Table B2 can, thus, be interpreted as cointegrating relationships, as currency misalignment is defined as the deviation of the real effective exchange rate from its equilibrium value. As Table B2 shows, all subcomponents are indeed statistically significant with the expected signs, except for the net foreign asset variable for China, which is insignificant.

In sum, the significant determinants of the two country’s current account balances – especially the currency misalignment factor itself – are quite robust with respect to different approaches in controlling for currency misalignment.

3.2 Country-Specific Factors

In this subsection, we consider the roles of China- and Germany-specific factors using the following specification:

where country-specific factors are collected in the vector X.

For China, the vector Xt − 1 includes a) a dummy variable to capture the period in which the Chinese currency is tightly linked to the US dollar, b) a dummy variable for the 1997 Asian financial crisis (AFC), c) a financial liberalization variable (Chinn and Ito 2006), and d) a dummy variable for the post-1988 export-rebate (full refund) period.Footnote 32 For Germany, it includes a) the TARGET2 balances, both in levels and first differences, b) Germany’s relative misalignment within the euro area, and c) Germany’s current account position against other euro area countries. These factors are meant to disentangle some euro area specific forces on Germany’s external balances.

The individual effects of these China-specific factors are presented in Column (1) and (2) of Table 5. Conditional on the significant currency misalignment and other economic variables, the Asian financial crisis dummy variable, the financial liberalization, and export-rebate dummy variables do not affect China’s current account balance in a statistically significant way.Footnote 33 The dummy variable that captures the heavily managed exchange rate is indeed statistically significant, but it does not improve the adjusted R2 estimate.

Columns (3) and (4) of Table 5 present the individual Germany-specific factors. The TARGET2-balance of Germany normalized by GDP measures the cumulative net capital inflows from other euro area countries into Germany since the beginning of the 2010 European sovereign debt crisis and is widely regarded as one of the key indicators of financial tension among euro area member countries. The TARGET2-balance variable yields the expected negative sign, albeit not statistically significant.

The annual change in the TARGET2-balance variable is the net financial flow that affects Germany’s borrowing constraints, and can potentially facilitate a level of consumption beyond income (Sinn and Wollmershäuser 2012). The coefficient estimate of the change in the TARGET2-balance, however, is very small and statistically insignificant. The finding is in line with those of Auer (2014), who reports that TARGET2 funds have been used primarily to finance capital flight, not current account deficits.

It is known that Germany’s level of currency misalignment against the rest of the world can be different from that against other euro area member countries. For instance, Germany was in the overvaluation position against the rest of the world including other euro area member countries in the 1990s. In the early 2000s, Germany became undervalued within the euro area though it was still on the average overvalued to countries outside of the euro area. Since the GFC, Germany has gradually moved to an undervalued position against countries both within and outside the euro area as depicted in Fig. 3.Footnote 34 Do the different patterns of currency misalignment within and outside the euro area affect Germany’s current account behavior? We address this issue by including a relative misalignment variable given by the ratio misalignment against the euro area countries and against the rest of the world in the regression. Our results show that the relative misalignment effect is quite small and statistically insignificant.

Column 4 of Table 5 also presents the implication of incorporating the German current account balance against other euro area countries in the regression. The euro area specific balance has a significant coefficient estimate that is quite close to 1; that is, the balance against other member countries contributes almost one-to-one to Germany’s overall balance. If it is the case, then the remaining explanatory variables are there to explain Germany’s current account balance excluding euro area countries. It is of interest to note that the German currency misalignment effect is significantly stronger in the post-GFC period – a result similar to the one found in the Chinese data – in presence of the euro area current account-balance variable. That is, if the intra-euro area linkages are accounted for, the pattern of German currency misalignment effect before and after the GFC is comparable to the Chinese one. For the other significant factors, the presence of the balance against other member countries does not change the signs of their impacts though, apparently, weakens their magnitudes.

This last result is also relevant in the context of the policy implications that can be drawn from the analysis. Aizenman and Sengupta (2011), for instance, made an observation that during the last 30 years the average current account of the euro area was close to a balanced position. As opposed to China, concerns about the German current account surplus would thus be more of an intra-European issue, rather than contributing to global imbalances. If that observation would still reflect today’s current account patterns, then our conclusion that ‘Germany is becoming the new China’ would be weakened.

Figure 4 of the appendix shows that Germany has indeed changed in this regard: Germany’s increase in its current account surplus is mainly due to trade with non-euro countries. This is related to the ECB following a monetary and exchange rate policy as a compromise solution for the aggregate monetary union. With increased heterogeneity of the euro area countries (and, recently, a strong German business cycle), this necessarily means that the Euro is undervalued for Germany – pushing Germany’s current account surpluses vis-à-vis the non-euro countries to new heights. Appendix Fig. 4 illustrates that both views are correct: As in Aizenman and Sengupta (2011), the pre-2007 period – which their paper mainly covers – Germany’s imbalances were mostly vis-à-vis other member countries of the European Monetary Union. After 2007, Germany is mainly characterized by external imbalances.

4 Concluding Remarks

China and Germany are the two countries that account for the lion’s share of global current account imbalances. They have experienced large and sustained surpluses in the last two decades. Before the GFC, Germany is deemed to be a country that has an overvalued currency and a sizeable current account surplus. China, on the other hand, is accused of building up current account balances with an undervalued currency. In the post-GFC period, the German currency has been gradually moved from overvaluation to undervaluation, while the Chinese one has gradually become an overvalued currency. The current accounts of these two countries have evolved accordingly – the German current account surplus has been steadily increased and the Chinese surplus steadily declined in the post-GFC period.

Our sample period allows us to draw additional insights about the evolution of current account balances after the crisis. One finding is that, for these two surplus countries, they have different current account determinants and some of them are country-specific, and have behaved differently after the GFC. That is, our exercise points out the importance of country-specific knowledge and the possible limitation of a one-size-fits-all approach. Further, for the German case, we document the importance of differentiating balances against euro and non-euro countries; a point that is not typically considered by existing studies.

In view of these developments, one can say China is reminiscent of the “old” Germany, and Germany is remarkably becoming more and more similar to the conventional view of the “old” China. These results update and extend the comparisons of China and Germany in Aizenman and Sengupta (2011) and Ma and McCauley (2014). Further, global imbalances are not passé. While Feldstein (2011) was right that natural forces would ultimately bring China’s currency and current account back closer to equilibrium, it now seems Germany may be about to assume China’s old role in the global economy.

Currency misalignment and current account imbalances are contentious issues. While persistently large current account deficits are considered symptoms of economic ills, their counterparts – substantial and sustained current account surpluses also have critical economic and welfare implications for both surplus countries and their trading partners. In the early debate – often echoed in today’s policy discussions, Keynes had argued that “the social strain of an adjustment downwards is much greater than that of an adjustment upwards” (Keynes 1941, p. 28).

Our empirical findings show that the usual culprit currency misalignment affects China’s and Germany’s current account dynamics – though its marginal explanatory power in the former country is weak and becomes significant in the post-2007 period only, while in the latter, it has been present over the whole sample period. Also, the currency misalignment effect is observable in the presence of other explanatory variables and across different definitions of currency misalignment.

Of course, one needs to keep in mind that, while China has authoritative control over its currency, Germany can only indirectly influence it via its one-country-one-vote representation in the ECB’s Governing Council. Nevertheless, slightly over 90% of variations in these two countries’ surpluses can be explained by currency misalignment and other relevant economic factors. Our analyses, thus, indicate that appropriate economic policies, including foreign exchange policy, can be formulated to rectify or alleviate global imbalances.

There are a few related questions that warrant discussion in future studies of China’s and Germany’s current account dynamics. One interesting question is: what is the implication of China’s continuous economic reform for its external position? For Germany, a key question is: Can it sustain the high level of current account surpluses under the current institutional arrangements? And, what are the repercussions on other euro area countries, as well as on the welfare of its own citizens?

Notes

In 2018, Christine Lagarde specifically addressed Germany’s role in reducing global imbalances in the post-crisis period: “We need to ask why German households and companies save so much and invest so little, and what policies can resolve this tension” (Speech at the joint IMF-BBk conference “Germany-Current Economic Policy Debates”, January 2018).

In 2015, China’s surplus was USD 304.2 bn., while that of Germany was USD 288.2 bn. The US deficit in the same year was USD 434.6 bn., accounting for 35% of the world’s current account deficits.

Since China’s current account surplus started bourgeoning at the beginning of the twenty-first century, its foreign exchange policy has been scrutinized and criticized. The US is arguably the most vocal critic and threatens to impose various retaliation measures including the 2005 Schumer–Graham bipartisan bill that proposes to impose an across the board tariff on all imports from China to force China to stop currency manipulation. More recently, also Germany has been in the focus of criticism, both vis-a-vis the US and its European trading partners.

Ma and McCauley (2014) compares the evolution processes of the Chinese and German imbalances.

For China, Giannellis and Koukouritakis (2018) is an exception.

Currency undervaluation and the resulting misalignment lead to contentious policy debate and academic discussions (Mattoo and Subramanian 2009; Staiger and Sykes 2010; Marchetti et al. 2012; Engel 2011; Corsetti et al. 2018). Engel (2011), for example, argues that maintaining the exchange rate at its fundamental equilibrium level should be an additional independent policy objective of central banks.

For instance, Hans-Jürgen Schmahl, the former member of the German Council of Economic Experts criticized the German overvaluation (“Die teure D-Mark behindert deutsche Exporteure – vor allem in Europa”, Die Zeit, April 16th, 1993).

“Why Germany’s current-account surplus is bad for the world economy”, The Economist, July 8th, 2017.

Some studies examine the real effective exchange rate effect on current account balances; see, for example, Khan and Knight (1983), Edwards (1989), Lee and Chinn (2006), and Arghyrou and Chortareas (2008). Some studies consider currency misalignment instead of real effective exchange rate; see, for example, Freund and Pierola (2012), Algieri and Bracke (2011), Di Nino et al. (2011), and Haddad and Pancaro (2010). Gnimassoun and Mignon (2015) and Gnimassoun (2017) suggest that the use of currency misalignment measures alleviates endogeneity concerns.

In 2005, China modified its exchange rate policy from a de facto dollar peg to a “managed floating exchange rate regime,” which put the RMB on a gradual appreciation path. China replaced the managed float with a stable RMB/dollar rate policy in the midst of the global financial crisis, reestablished the managed float and allowed the RMB to appreciate in 2011. In 2015, China revamped its RMB central parity formation mechanism to enhance the role of market forces. In the same year, the IMF indeed stated that the RMB is at a level that is no longer undervalued in its Article IV consultation mission press release. Over time, China, either because of domestic or external considerations, has loosened its grip on the RMB and led to changes in the misalignment pattern.

For some observers, the limited role of currency misalignment in China in the pre-crisis period may appear surprising, as there is an abundance of news reports on the alleged use of currency misalignment to stimulate exports. However, it is not uncommon that academic studies reported the Chinese exports and imports do not follow the textbook exchange rate effects and do not empirically satisfy the Marshall-Lerner condition (Cheung et al. 2012; Devereux and Genberg 2007; Marquez and Schindler 2007), and that the Renminbi misalignment estimate can span a wide range that covers both under- and overvaluation (Bineau 2010; Cheung and He 2019).

Compared to the Aizenman and Sengupta (2011) specification, there are several contributions. First, we extend the sample period beyond the global financial crisis and obtain additional insight about the evolution of current account balances after the crisis. Secondly, the use of currency misalignment instead of real exchange rates as an important explanatory factor alleviates endogeneity concerns. Third, we include additional controls (e.g. China- and Germany-specific factors), and, fourth, we consider a full multivariate specification.

The beginning of the sample period is mainly determined by the availability of Chinese data. We consider the same sample period for both China and Germany to facilitate the joint estimation and comparison.

See Couharde et al. (2017) for a detailed discussion of the database.

The literature covers a diverse set of determinants of current account balances. Our choices are based on existing studies including Ca’Zorzi et al. (2012), Algieri and Bracke (2011), Karunaratne (1988), Calderon et al. (2002), Chinn and Prasad (2003), Gruber and Kamin (2007), Liesenfeld et al. (2010), Aizenman and Sengupta (2011), Duarte and Schnabl (2015), Unger (2017).

Results obtained from alternative choices of crisis years for the dummy variable are available upon request. Among the alternative crisis variables, the Crisis07 dummy variable yields the highest R-squares and, thus, is used in all subsequent regressions.

Analytically, Devereux and Genberg (2007), for example, show that an RMB depreciation will have an immediate reverse effect and little short-run effect on the current account balance.

The (total) age dependency variable, which is the sum of the young and old age dependency variables is not included to avoid multicollinearity.

Other empirical studies on the determinants of the current account came up with similarly mixed results. While, for example, Gruber and Kamin (2007) mostly found negative coefficients for both, the young and old age dependency ratio, Aizenman and Sengupta (2011) report heterogeneous results across the two countries and their age profiles.

Similarly, Horioka et al. (2007) report a positive old-age dependency effect in Chinese saving data.

For Germany, the statistically insignificant old-age dependency ratio is not surprising given the well-documented non-standard saving behavior of Germans. Börsch-Supan et al. (2001), for instance, document the “German savings puzzle” of relatively flat saving rates across age profiles in Germany. A recent study by the Deutsche Bank even finds the savings rate to increase in the second half of retirement. According to survey data, two motives stand out in explaining this finding: i) German retirees are eager to hedge longevity risk and ii) more than half of them would prefer passing their savings to descendants rather than consuming it by themselves (Kaya and Mai 2019).

To account for the effect of a slowdown in global growth after the GFC, we considered adding an interaction term of the global growth variable with our crisis dummy. For both countries, the interaction term is insignificant, and its inclusion does not change our main results. These results are not reported for brevity but are available upon request.

The theoretical effects of these variables are mostly ambiguous. Expansionary monetary policy may exert expenditure-switching and opposing income-absorption effects. Monetary aggregates are, furthermore, often considered to be proxies of financial depth. Empirically, Kim (2001) finds positive short-term effects on the trade balance (of small open) economies. The coefficients of the inflation and real interest rate variables are in line with what the savings literature surmises (Loayza et al. 2000; Masson et al. 1998).

In passing, we note that the residual estimates of these specifications a) pass the stationarity test; that is, we cannot reject the hypothesis that they are stationary, and b) pass the serial correlation test; that is, we cannot reject the hypothesis that these residuals are not serially correlated. The results are available upon request.

In addition to the two robustness exercises reported below, we assessed whether trade barriers play a marginal effect. However, as reported in Table B1 of Appendix B, neither the average tariff rates nor the accession to the WTO help to explain these two countries’ current account balances.

We also experimented with other CEPII estimates based on i) a smaller set of fundamental variables (i.e. relative sectoral productivity alone, or relative sectoral productivity and net foreign assets), ii) a smaller set of trade partners (top-30), and iii) time-varying trade weights based on a rolling 5-year window. Regarding the estimates by Cheung et al. (2017), we alternatively included pooled estimates over all income groups and quadratic regression equations (instead of linear regressions, separately estimated for developing and developed countries). The results are remarkably robust across these choices (with minor exceptions) and are available upon request.

China established the export tax rebate policy in 1985 and implemented the “full refund” in 1988. See Liu (2013) and references therein for the evolution of China’s export VAT rebate policies.

The insignificant financial liberalization effect is likely attributed to the fact that the Chinn-Ito index is an aggregate measure of financial openness. Different aspects of financial regulations can have opposing effects on the current account (Moral-Benito and Roehn 2016).

On the development of misalignment within the euro area see, for example, Coudert et al. (2013).

References

Aizenman J, Sengupta R (2011) Global imbalances: is Germany the new China? A skeptical view. Open Econ Rev 22(3):387–400

Algieri B, Bracke T (2011) Patterns of current account adjustment—insights from past experience. Open Econ Rev 22(3):401–425

Almås I, Grewal M, Hvide M, Ugurlu S (2017) The PPP approach revisited: a study of RMB valuation against the USD. J Int Money Financ 77:18–38

Arghyrou MG, Chortareas G (2008) Current account imbalances and real exchange rates in the euro area. Rev Int Econ 16:747–764

Auer, RA (2014) What drives TARGET2 balances? Evidence from a panel analysis. Econ Policy 29(77):139–197

Bagnai A, Manzocchi S (1999) Current-account reversals in developing countries: the role of fundamentals. Open Econ Rev 10(2):143–163

Bineau Y (2010) Renminbi's misalignment: a meta-analysis. Econ Syst 34(3):259–269

Börsch-Supan A, Reil-Held A, Rodepeter R, Schnabel R, Winter J (2001) The German savings puzzle. Res Econ 55(1):15–38

Bussière M, Fratzscher M, Müller GJ (2006) Current account dynamics in OECD countries and in the new EU member states: an intertemporal approach. J Econ Integr 21:593–618

Ca’Zorzi M, Chudik A, Dieppe A (2012) Thousands of models, one story: current account imbalances in the global economy. J Int Money Financ 31(6):1319–1338

Calderon CA, Chong A, Loayza NV (2002) Determinants of current account deficits in developing countries. BE J Macroeconomics: Contributions to Macroeconomics 2:1

Cavallo E, Eichengreen B, Panizza U (2017) Can countries rely on foreign saving for investment and economic development? Rev World Econ:1–30

Cheung Y-W, Fujii E (2014) Exchange rate misalignment estimates—sources of differences. Int J Financ Econ 19(2):91–121

Cheung Y-W, He S (2019) Truths and myths about RMB misalignment: a meta-analysis. Comp Econ Stud forthcoming

Cheung Y-W, Chinn MD, Fujii E (2007) The overvaluation of renminbi undervaluation. J Int Money Financ 26(5):762–785

Cheung Y-W, Chinn MD, Fujii E (2009) Pitfalls in measuring exchange rate misalignment. Open Econ Rev 20(2):183–206

Cheung Y-W, Chinn MD, Qian XW (2012) Are Chinese trade flows different? J Int Money Financ 31(8):2127–2146

Cheung, Y-W, Aizenman J, and Ito H (2016) The interest rate effect on private saving: alternative perspectives. NBER Working Paper #22872

Cheung Y-W, Chinn MD, Nong X (2017) Estimating currency misalignment using the Penn effect: it is not as simple as it looks. International Finance 20(3):222–242

Chinn MD, Ito H (2006) What matters for financial development? Capital controls, institutions, and interactions. J Dev Econ 81(1):163–192

Chinn MD, Prasad ES (2003) Medium-term determinants of current accounts in industrial and developing countries: an empirical exploration. J Int Econ 59(1):47–76

Cooper, RN (2008) Global imbalances: globalization, demography, and sustainability. J Econ Perspect 22(3): 93–112

Corsetti, G, Dedola L, and Leduc S (2018) Exchange rate misalignment, capital flows, and optimal monetary policy trade-offs. CEPR discussion papers #12850, March 2018

Coudert V, Couharde C, Mignon V (2013) On currency misalignments within the euro area. Rev Int Econ 21(1):35–48

Couharde C, Delatte A-L, Grekou C, Mignon V, and Morvillier F (2017) EQCHANGE: a world database on actual and equilibrium effective exchange rates. Working paper CEPII no. 2017–14, 2017

Devereux MB, Genberg H (2007) Currency appreciation and current account adjustment. J Int Money Financ 26(4):570–586

Di Nino V, Eichengreen B, and Sbracia M (2011) Real exchange rates, trade, and growth: Italy 1861–2011. Quaderni di storia economica (Economic History Working Papers) 10. Bank of Italy.

Duarte P, Schnabl G (2015) Macroeconomic policy making, exchange rate adjustment and current account imbalances in emerging markets. Rev Dev Econ 19(3):531–544

Edwards S (1989) Real exchange rates, devaluation, and adjustment exchange rate policy in developing countries. MIT Press

Edwards S (2004) Thirty years of current account imbalances, current account reversals, and sudden stops. IMF Staff Pap 51(1):1–49

Edwards S (2008) On current account surpluses and the correction of global imbalances. In: current account and external Financing, Cowan, Kevin; Edwards, Sebastian and Valdes, Rodrigo O. Santiago: Central Bank of Chile, 2008

Engel C (2011) Currency misalignments and optimal monetary policy: a reexamination. Am Econ Rev 101(6):2796–2822

Feldstein M (2011) The role of currency realignments in eliminating the US and China current account imbalances. J Policy Model 33(5):731–736

Freund C, Pierola MD (2012) Export surges. J Dev Econ 97(2):387–395

Garroway C, Hacibedel B, Reisen H, Turkisch E (2012) The renminbi and poor-country growth. World Econ 35(3):273–294

Giannellis N, Koukouritakis M (2018) Currency misalignments in the BRIICS countries: fixed vs. floating exchange rates. Open Econ Rev 29(5):1123–1151

Gnimassoun B (2017) Exchange rate misalignments and the external balance under a pegged currency system. Rev Int Econ 25(5):949–974

Gnimassoun B, Mignon V (2015) Persistence of current-account disequilibria and real exchange-rate misalignments. Rev Int Econ 23(1):137–159

Gruber JW, Kamin SB (2007) Explaining the global pattern of current account imbalances. J Int Money Financ 26(4):500–522

Haddad M, Pancaro C (2010) Can real exchange rate undervaluation boost exports and growth in developing countries? Yes, but not for long. The World Bank, Economic Premise

Horioka CY, Junmin W (2007) The determinants of household saving in China: a dynamic panel analysis of provincial data. J Money, Credit, Bank 39(8):2077–2096

Isard P (2007) Equilibrium exchange rates: assessment methodologies. IMF Working Paper No. 7-296. International Monetary Fund, 2007

Kaldor N (1980) The foundations of free trade theory and their implications for the current world recession. In: Unemployment in Western countries, Malinvaud, Edmond and Fitoussi, Jean-Paul (Eds), International Economic Association Publications. Palgrave Macmillan, London, 1980

Karunaratne ND (1988) Macro-economic determinants of Australia’s current account, 1977–1986. Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv 124(4):713–728

Kaya O, Mai H (2019) Why do elderly Germans save? Deutsche Bank research focus, March 5, 2019

Keynes, JM (1941) Memorandum on post war currency policy, September 8, 1941. Reprinted in: the collected writings of John Maynard Keynes. Vol. 25: The Origins of the Clearing Union, 1940–1942, Johnson, Elizabeth and Moggridge, Donald (Eds.), Royal Economic Society, London 1978

Khan MS, Knight MD (1983) Determinants of current account balances of non-oil developing countries in the 1970s: an empirical analysis. Staff Papers 30(4):819–842

Kim S (2001) Effects of monetary policy shocks on the trade balance in small open European countries. Econ Lett 71(2):197–203

Lane PR, Milesi-Ferretti GM (2018) The external wealth of nations revisited: international financial integration in the aftermath of the global financial crisis. IMF Economic Review 66(1):189–222

Lee J, Chinn MD (2006) Current account and real exchange rate dynamics in the G7 countries. J Int Money Financ 25(2):257–274

Li H, Zhang J, Zhang J (2007) Effects of longevity and dependency rates on saving and growth: evidence from a panel of cross countries. J Dev Econ 84(1):138–154

Liesenfeld R, Valle Moura G, Richard J-F (2010) Determinants and dynamics of current account reversals: an empirical analysis. Oxf Bull Econ Stat 72(4):486–517

Liu X (2013) Tax avoidance through re-imports: the case of redundant trade. J Dev Econ 104:152–164

Loayza N, Schmidt-Hebbel K, Servén L (2000) What drives private saving across the world? Rev Econ Stat 82(2):165–181

Ma G, McCauley RN (2014) Global and euro imbalances: China and Germany. China & World Economy 22(1):1–29

Marchetti J, Ruta M, and Teh R (2012) Trade imbalances and multilateral trade cooperation. CESifo Working Paper #4050

Marquez J, Schindler J (2007) Exchange-rate effects on China's trade. Rev Int Econ 15(5):837–853

Masson PR, Bayoumi T, Samiei H (1998) International evidence on the determinants of private saving. World Bank Econ Rev 12(3):483–501

Mattoo A, Subramanian A (2009) Currency undervaluation and sovereign wealth funds: a new role for the World Trade Organization. World Econ 32(8):1135–1164

Moral-Benito E, Roehn O (2016) The impact of financial regulation on current account balances. Eur Econ Rev 81:148–166

Qin D, He X (2011) Is the Chinese currency substantially misaligned to warrant further appreciation? World Econ 34(8):1288–1307

Sinn, H-W (2007) Can Germany be saved? The malaise of the world's first welfare state. MIT Press: Cambridge

Sinn, H-W (2014) The euro trap: on bursting bubbles, budgets, and beliefs. Oxford University Press: Oxford

Sinn H-W, Wollmershäuser T (2012) Target loans, current account balances and capital flows: the ECB’s rescue facility. Int Tax Public Financ 19(4):468–508

Staiger RW, Sykes AO (2010) Currency manipulation’and world trade. World Trade Rev 9(4):583–627

Steinkamp S, Westermann F (2014) The role of creditor seniority in Europe's sovereign debt crisis. Econ Policy 29(79):495–552

Svensson LEO, Razin A (1983) The terms of trade and the current account: The Harberger-Laursen-Metzler effect. J Polit Econ 91(1):97–125

Unger R (2017) Asymmetric credit growth and current account imbalances in the euro area. J Int Money Financ 73:435–451

Williamson J (1983) The exchange rate system, policy analyses in international economics 5. Washington DC: Institute for International Economics

Acknowledgments

We would especially like to thank two anonymous referees and the editor for their constructive comments and suggestions, which substantially improved the paper. We also thank Joshua Aizenman, Philippe Bacchetta, Angela Capolongo, Woo Jin Choi, Paul Luk, Xingwang Qian, Kishen S. Rajan, and participants of the Bank of Finland Institute for Economies in Transition (BOFIT) Seminar in Helsinki, as well as the conference on “Current Account Balances, Capital Flows and International Reserves” in Hong Kong for their comments and suggestions. Cheung gratefully thanks The Hung Hing Ying and Leung Hau Ling Charitable Foundation for its support. Westermann thanks BOFIT for its hospitality during the research visit in 2018.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1

Appendix 2: Additional Figures and Regression Results

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cheung, YW., Steinkamp, S. & Westermann, F. A Tale of Two Surplus Countries: China and Germany. Open Econ Rev 31, 131–158 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11079-019-09537-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11079-019-09537-7