Abstract

Weed control is fundamental in plantations of valuable broadleaved species. The most common weeding techniques are repeatedly applied herbicides and removable plastic mulching, both raising environmental concerns. We studied the performance of these techniques on a hybrid walnut plantation, compared with three biodegradable mulch alternatives: a prototype bioplastic film, a layer of composted woodchips and a layer of ramial chips. The durability and effect of the treatments on tree performance (survival, growth, physiological traits) and soil features (moisture and temperature) were evaluated over 4 years. Herbicide yielded the best results, while all the mulching treatments provided better results than controls for nearly all the variables. The performance of plastic and bioplastic films was similar, suggesting that the latter could replace plastic mulching. The performance of the two chip mulches was similar and slightly below that of the films, probably because of the excessive thickness of the former (13–14 cm). In summary, biodegradable mulches showed high effectiveness in controlling weeds and so could offer an alternative to herbicide application and plastic mulching when these are contra-indicated technically (accessibility, repeatability), economically (labour cost), legally or environmentally.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In Mediterranean conditions, the primary limiting factor for tree growth is water shortage during summer drought (Villar-Salvador et al. 2012) which is expected to worsen in the future (Vallejo et al. 2012; Dumroese et al. 2015), and whose negative effect can be exacerbated by a poor soil preparation (Löf et al. 2012) and by weeds. The competition effect of unwanted vegetation is especially intense on highly fertile sites such as former agricultural fields (Kogan and Alister 2010; Olivera et al. 2014), and is particularly harmful to young seedlings with underdeveloped root systems and insufficient leaf area to shade and control weed development unaided (Coll et al. 2003; Devine et al. 2007). The use of herbicides, especially glyphosate, is the most common weed control technique applied in forest plantations in Europe (Willoughby et al. 2009) and most temperate areas worldwide, because of its efficacy against a wide range of weed types (Kogan and Alister 2010). However, growing social and environmental concern about herbicides is curbing their use (Ammer et al. 2011). They are banned in public forests in Quebec (Thiffault and Roy 2011) and in a broad range of forest areas in various European countries, for example Germany, Denmark, Czech Republic and Slovakia (Willoughby et al. 2009). Also, the need for repeated application, at least once a year, and during one particular stage of weed development, limits herbicide use in plantations under low intensity management schemes, when minimizing invested resources is fundamental. Alternatives or supplements to herbicide application include the use of planting strategies to reduce water or nutrient stress from competing vegetation such as the use of nursery nutrient loading or direct application of controlled-release fertilizer to the root zone (Jacobs et al. 2005; Uscola et al. 2015; Schott et al. 2016). Another alternative to repeated, time-consuming chemical or mechanical weeding in tree plantations is one-time application of groundcover or “mulching” (Chalker-Scott 2007). This technique consists of covering the ground around the tree to prevent the germination and growth of weeds (Maggard et al. 2012), being a physical barrier that stops light reaching the soil (Bond and Grundy 2001). The most significant benefit of mulching is increased soil water content, especially during the driest periods (Maggard et al. 2012; McConkey et al. 2012), through preventing water transpiration by weeds and reducing soil water evaporation (Percival et al. 2009; Kumar and Dey 2010; Barajas-Guzmán and Barradas 2011; Zegada-Lizarazu and Berliner 2011). Other reported benefits are extreme temperature buffering (Cregg et al. 2009; Barajas-Guzmán and Barradas 2011; Arentoft et al. 2013) and improvement of soil physical properties (Chalker-Scott 2007), which helps trees regulate root respiration and favours water and nutrient uptake (Dodd et al. 2000). Organic mulches may increase soil nutrient and organic matter content during their decomposition (Merwin et al. 2001; Van Sambeek and Garrett 2004). The resulting positive effect of mulching on tree survival and growth is cumulative and perceptible over subsequent decades (George and Brennan 2002; Pedlar et al. 2006). To date, most studies on the use of this technique and its effects on vegetation and soil have been conducted in temperate conditions. In areas limited by water, such as prevail in Mediterranean sites, the efficacy of this technique is still unproven.

The most widespread mulching material is black polyethylene film (Barajas-Guzmán et al. 2006; Arentoft et al. 2013), a low-cost homogeneous material with proven positive effects on forest plantations (Green et al. 2003). Its use is, however, limited by concerns about using long-lifespan plastics in the open air, by its unsightliness, and especially by its high cost of removal and disposal (Shogren and Rousseau 2005). As a result, a wide range of biodegradable alternatives are being developed, including bio-based plastics (Álvarez-Chávez et al. 2012), notably polylactic acid (PLA) (Finkenstadt and Tisserat 2010) and polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA). These materials show homogeneous behaviour but have not yet been widely evaluated in outdoor conditions for forest restoration purposes. Other biodegradable mulches used in tree plantations include those based on locally abundant (often waste) organic materials, such as straw, woodchips and paper.

The aim of this work was to evaluate, on a 5-year basis, whether groundcover based on renewable, biodegradable materials could offer a suitable alternative to herbicide application or plastic-based mulches on valuable broadleaf plantations in Mediterranean conditions. Such plantations are being increasingly considered as an alternative use, with both economic and environmental advantages, for agricultural land facing abandonment (Aletà et al. 2003; Coello et al. 2009) in Mediterranean areas.

Our hypothesis was that these novel mulches would yield technical outcomes similar to those of plastic mulching for tree performance and micro-site features, while being more environmentally friendly and not needing removal. They could also usefully replace herbicide application, being cost-saving (less labour-intensive) and ecologically and socially more acceptable.

Methods

Study area and experimental design

The study was conducted in Solsona, NE Spain (41°59′N; 1°31′E), in a flat, homogeneous, former agricultural field, located at an elevation of 670 m a.s.l., and farmed until the year of planting for winter cereal production (wheat, barley and oats). The study area had a Mediterranean continental sub-humid climate (Martín-Vide 1992) or Mediterranean continental Csb (Temperate, dry mild summer) in the Köppen classification. Mean annual temperature is 12.0 °C and mean annual and summer precipitation are 670 mm and 171 mm, respectively (Ninyerola et al. 2005). The analysis of soil samples taken at three different points at depth 5–30 cm revealed a loamy texture (21% clay, 45% silt, 34% sand) and pH 8.2. Initial soil organic matter content was 2.3% and active limestone was 5.2%. The main weed species were first Avena fatua and second Lactuca serriola.

One experimental plantation was set up in March 2011 with 1-year-old hybrid walnut (Juglans × intermedia) MJ-209xRa, 40–60 cm high, bare-rooted, planted on a 4 × 4 m frame. Soil preparation consisted in deep (50 cm), crossed sub-soiling with a 150 HP tractor with chisel, and pits were opened manually just before tree establishment. Six different vegetation control conditions were then applied: (1) chemical weeding (glyphosate, 22.5 cm3/tree at 1.25%) applied yearly in May with a backpack sprayer (HERBICIDE), (2) commercial black polyethylene film, treated against UV radiation, 80 µ thick (PLASTIC), (3) prototype black PHA (polyhydroxyalkanoate) film, 100% biodegradable, 80 µ thick (BIOFILM), (4) a layer of woodchips made with woody debris from pine forest harvesting operations, composted for 8 months, size 15/35 mm, layer thickness 13/14 cm (WOODCHIPS), (5) a layer of fresh ramial woodchips (branches and twigs from urban pruning), size 15/35 mm, layer thickness 13/14 cm (RAMIALCHIPS), and (6) no treatment (CONTROL). Each weeding treatment was applied on 100 × 100 cm of soil (centred on the tree). No artificial watering or fertilization was applied to the experimental area.

These treatments were deployed in a randomized complete block design with subsamples. Each of the five blocks consisted on six randomly distributed plots (one per treatment) with 12 trees each (192 m2), for a total of 72 trees per block (1152 m2) and 360 experimental trees in all (5760 m2).

Weather and soil variables

Daily temperature and precipitation data were obtained during the study period from a nearby weather station belonging to the Catalan Meteorological Service, located less than 1 km away from the study site at a similar altitude. The first two vegetative periods (lasting normally from April–May to October), namely 2011 and 2012, were notably drier and warmer than the historical average, especially during summer, with precipitation 60 and 70% lower than the historical average. Precipitation was not only low but also unevenly distributed, with few episodes of significant rainfall. However, 2013, 2014 and 2015 were much wetter, with summer precipitation close to the historical average (2013 and 2015) and 36% higher (2014) and with a fairly regular distribution of rainfall episodes (Table 1).

Soil volumetric water content (l water per l soil) at depth 5–20 cm was estimated gravimetrically on two different dates: June 2012 and August 2014. Each sampling campaign was conducted after at least 2 weeks without rain, and consisted of the extraction of four soil samples per treatment in 3 blocks (144 in all). Sampling points were located 30 cm away from the tree stem at aspect 225° (SW); approximately 150 g of soil was collected with a soil auger. Samples were kept in tared, zip-closed plastic bags, and weighed within 3 h at the laboratory on a precision scale (0.1 g) to obtain fresh weight, after subtracting the bag weight. Dry weight was obtained after leaving the bags fully open at 65 °C for 96 h, using the same procedure.

Soil temperature at depth 7.5 cm was recorded continuously from the time of tree planting using thermometers with built-in dataloggers. There were three thermometers per treatment (one per block, in 3 blocks), located 30 cm away from the tree in aspect 225° (SW), each tied to a short rope for easy retrieval. The results for soil temperature are shown for three key periods: a representative flushing period (1–20 May 2012), the warmest spell (11–26 August 2011) and the coldest spell (2–23 February 2012) after the time of planting.

Tree measurements and mulch durability

Seedling mortality was monitored at the end of each vegetative period (2011–2015), together with any signs of vegetative problems (death of the apical shoot or presence of basal sprouting). Plant basal diameter and total height were recorded at the time of planting, and then at the end of each growing season using a digital calliper and a measuring tape, respectively. The diameter and height growth of a living tree during a vegetative period was calculated as the difference between two consecutive measurements. Tree height growth was considered to be zero for a given year when the apical shoot was dead, but the height of the highest living bud was measured to have the initial size for the subsequent year.

Physiological variables were measured within the growing seasons. During July 2012, predawn (07:00 solar time) and midday (12:00 solar time) leaf water potential were measured with a pressure chamber (Solfranc technologies, Vila-Seca, Spain) using ten leaves per treatment collected from different trees from 3 blocks. In July and August 2014 midday leaf water potential was measured likewise. In all cases the measuring day was chosen after at least two weeks without rain. Finally, leaf chlorophyll content was estimated using a Minolta SPAD-502 instrument (Minolta Camera Co. Osaka, Japan) in both July 2012 and July 2014 on fully elongated leaves exposed to direct sunlight. For each treatment, 10 trees from 3 blocks were sampled, and the SPAD (Soil Plant Analysis Development) value, a relative indicator of leaf greenness (Djumaeva et al. 2012) was obtained for each tree as the average of three fully elongated, sun-exposed leaves.

Forty months after the start of the experiment (June 2014), the durability of the four mulching treatments was assessed by visual estimation of the percentage (rounded to tens) of mulched area free of weeds (chip mulches) or free of weeds and also physically intact (film mulches). Mulch status was rated effective (showing at least 80% intact surface), partially damaged (40–70% intact surface) or ineffective (30% or less intact surface).

Statistical analysis

The data related to soil moisture, tree growth, tree water status and leaf chlorophyll were analysed independently for each measuring date. We used an analysis of variance (ANOVA), considering both treatment and block as fixed factors, and following the model:

where Y is the dependent variable; µ is the population mean for all treatments; αi is the treatment effect; βj is the block effect; eij is plot error and δijk is subsample error.

Normality of residuals was confirmed with the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. To meet this condition we used a square root transformation of the diameter growth values and the zero values of height growth were transformed to 0.0000001 (Kilmartin and Peterson 1972). Differences between treatments were examined by a post hoc Tukey test with the significance threshold set at p < 0.05. All these analyses were performed with SPSS v.19.0 software (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Armonk, NY, USA 2010). The rest of variables (soil temperature, tree survival and mulch durability) were analysed with descriptive statistics.

Results

Plant survival and growth

In general, mortality rates were low, less than 6% for all the treatments together along the five growing seasons. Most mortality occurred in unweeded plants (CONTROL), which showed an overall mortality of 33% at the end of 2012. This year was the driest and warmest, showing 94% of all casualties; there was no mortality thereafter.

Vegetative problems (loss of apical shoot or basal sprouting) were especially frequent in the CONTROL (25% on average in the five vegetative periods) and chip groundcover (RAMIALCHIPS—26% and WOODCHIPS—23%) plots, with the other treatments below 15%. Most of the vegetative problems (90%) arose during 2011 to 2013, affecting 26% of the trees considering all treatments, this figure falling to 6% in 2014 and 4% in 2015 (Table 2).

Throughout the study period there was a consistent and remarkable treatment effect (p < 0.001 in all cases) on annual tree diameter and height growth. The HERBICIDE plots gave predominantly the best results of all the treatments in terms of seedling growth, while CONTROL gave the poorest results (Fig. 1). Mulching treatments provided intermediate outcomes, with films (PLASTIC and BIOFILM) resulting in higher growth rates than chip layers (WOODCHIPS, RAMIALCHIPS) during the driest years (2011 and 2012).

Diameter and height growth time course of hybrid walnut during the first five growing seasons. Growth was calculated as the difference between the basal diameter (mm) or total height (cm) at the end and at the beginning of each growing season. Significant differences (p < 0.05) between treatments found each year are indicated by different letters, and were grouped according to Tukey test

Through 2013–2015 the average annual diameter growth was 15.7 mm for HERBICIDE, 10.9 mm for the mulches taken together and 6.5 for CONTROL. Annual height growth values in the last three growing seasons showed similar trends, with HERBICIDE at 83 cm, followed by 65 cm for mulches and 39 cm for CONTROL.

Plant and soil water status and chlorophyll content

During the driest year of the study period (2012), HERBICIDE provided the highest levels of soil moisture and the least negative soil and plant water potential values, while CONTROL gave the poorest results for all these variables (Table 3). The only significant differences in the effects of mulching treatments on plant and soil water potential were obtained in 2012, when in June BIOFILM plots showed more favourable pre-dawn leaf water potential values (a proxy of soil water status) than the other mulches, and in July, a more favourable midday leaf water potential than RAMIALCHIPS. In 2014, a particularly wet year, both HERBICIDE and RAMIALCHIPS resulted in better plant water status than CONTROL, while the other treatments showed no significant difference. Finally, soil moisture produced minor differences between mulching treatments, consisting in prevalently higher values in the case of chip mulches compared with film mulches (Table 3). The measurements of leaf chlorophyll content made in July 2012 and July 2014 showed no significant difference between treatments. In 2012, HERBICIDE showed the highest value (35.4 ± 0.9) followed by CONTROL (34.5 ± 1.05), while the average value of mulch treatments ranged between 33.1 and 33.6. Trees showed slightly higher SPAD values in 2014, led by BIOFILM (41.3 ± 1.9), HERBICIDE (40.7 ± 2.2) and CONTROL (40.2 ± 1.7), while the rest of mulch treatments had averages ranging between 38.9 and 39.2.

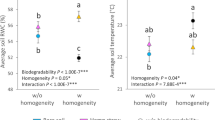

Soil temperature

Mulches had a remarkable buffer effect on soil temperature, especially chips (Fig. 2). For example, during a representative flushing period (May 2012) the minimum soil temperatures were 2 °C higher in chip mulch plots than in the other treatments. During the warmest period of the study (August 2011) the buffering effect of chip layer mulches was even stronger, with mean and average maximum temperatures respectively 4 °C and 6 °C lower than the average for the other treatments. Finally, during the coldest period of the series (February 2012) the effects of chip mulches were less noteworthy, with minimum soil temperatures 1 °C higher than in the case of film mulches, and 2 °C higher than for HERBICIDE and CONTROL, which were the only treatments in which soil temperatures fell below 0 °C. The most noticeable effect of film mulches was the increase, by 2–4 °C, in the maximum soil temperatures during the flushing period (May 2012) compared with CONTROL and chip layer mulches. Finally, HERBICIDE and CONTROL in general showed similar soil temperature trends, with slightly higher maximum temperatures during the flushing period for CONTROL, and during summer and winter for HERBICIDE.

Distribution of soil temperatures at depth 7.5 cm during the warmest spell (16 days in August 2011), the coldest spell (23 days in February 2012), and a representative flushing period (21 days in May 2012). The box length represents the interquartile range (Q1–Q3) while the horizontal line inside the box indicates the median

Durability of mulches

The durability assessment of mulching performed after 40 months (Fig. 3) gave PLASTIC the highest proportion of effective units: two-thirds of polyethylene mulches kept at least 80% of their surface being effective, whereas only 6% were rated ineffective (30% or less of their surface being effective). By contrast, approximately one-third of BIOFILM mulches were found effective at the evaluation time and a similar proportion were ineffective. The results for chip mulches fell between the two film mulches, with RAMIALCHIPS showing slightly higher durability than WOODCHIPS, with 47 and 37% of effective units and 6 and 14% of ineffective units.

Discussion

Hybrid walnut is characterised by late flushing, second half of May in our study area, which is four to five weeks after most weed emergence. This property allowed herbicide application to be postponed until early-to-mid-May. Chemical weeding was therefore applied on grown weeds (around 50–70 cm high on average), which left not a bare soil but a dry grass cover that was (1) free from transpiring vegetation, (2) dense enough to impede new weed proliferation and stop sunlight reaching the soil, thus mitigating soil water evaporation, and (3) highly permeable to water infiltration. These three features are especially beneficial during summers with infrequent precipitation distributed in low-volume episodes (typical in Mediterranean climates, and most common in 2011 and 2012 in our case) and might in part explain the outstanding results of the HERBICIDE treatment found in this study.

Mulching provided better results than CONTROL for most of the variables and measuring dates, as reported in most previous studies (Johansson et al. 2006; Abouziena et al. 2008; Maggard et al. 2012). Among the different mulching treatments, the relatively poor results of chip mulches during the dry years (2011 and 2012) might be linked to the thickness of the layer used (13–14 cm). This thickness was chosen based on previous studies (Granatstein and Mullinix 2008; Percival et al. 2009) carried out in wetter areas. Mulches made of chips and other organic materials need to be moistened adequately before they become permeable to water and let it through to the soil. In particularly dry summers with precipitation in small volume episodes as those which occurred in our study in 2011–2012, excessively thick organic mulches can prevent water reaching the soil (Gilman and Grabosky 2004). Film mulches (PLASTIC and BIOFILM) may also have kept water from reaching the soil during the low-volume rainfalls of 2011–2012. The two mulches yielded relatively similar results between them for both plant and soil variables. The similar mechanical properties of biofilms and plastic were also reported by Garlotta (2001). In general terms, black biofilm groundcover can be considered as a useful substitute for black polyethylene film: it is made from renewable raw materials and is biodegradable, so there is no disposal cost at the end of its service life. PHA belongs to the group of preferred bioplastics as regards environmental, health and safety impacts (Álvarez-Chávez et al. 2012) and highest production (Iles and Martin 2012). In addition, the growing demand for bioplastics in multiple applications is expected to bring down prices in the near future (Iles and Martin 2012). The choice of one formulation (plastic or bioplastic) over another could depend on differences in cost of purchase (lower for polyethylene) and removal (nil for biodegradable mulches).

Van Sambeek (2010) analysed 50 papers for the effect in terms of growth and fruit production of different weeding techniques on walnut, expressed as a relative response. The herbicide/control response ratio was 178, i.e. trees treated with herbicide yielded 78% more than those that were unmanaged. The figure was 267 for synthetic mulches (mostly polyethylene) and 265 for organic ones. In our study the average growth response (diameter and height) of HERBICIDE relative to CONTROL (unmanaged) was 272, much higher than the above reported response. However, mulches resulted in poorer relative responses than in that study, with PLASTIC giving a value of 196 and chip mulches averaging 180. These divergences could arise from (1) the delayed application of the herbicide treatment adapted to a late-flushing tree species, and (2) the occurrence in our study of particularly dry summers with very infrequent rainfall events in the two first years after planting, when (as stated above) mulches may have hindered water infiltration into the soil.

The trial presented mortality rates below 6% considering all treatments, indicating the suitability of the species for the site, despite the unusually dry 2011 and 2012. While mortality in 2011 was negligible (one seedling in all), it rose to 15 further seedlings at the end of 2012, probably as a consequence of the poor root development in 2011 (Watson 2005) and the depletion of reserves after two consecutive harsh years. The CONTROL treatment accounted for 75% of the dead seedlings of the study, highlighting the effect of weeding on survival (Green et al. 2003; Van Sambeek and Garrett 2004). Similarly, Green et al. (2003) and Chaar et al. (2008) found that the positive effect of weeding with respect to unweeded trees was especially noticeable in the second year after plantation. Vegetative problems, especially loss of apical shoots and symptoms such as basal sprout emergence, were especially frequent (one-third of the trees) during the first vegetative period, probably owing to the particular harsh conditions in 2011 and post-transplant shock effects (Oliet et al. 2013). However, during the following years the number of trees with vegetative problems diminished, indicating sound acclimatisation of the trees to the site conditions. We found a clear difference in the time course of growth in the plots under weed management (HERBICIDE and mulching) and the CONTROL plots between 2011 and 2012. Whereas the weeded trees kept a relatively similar aboveground growth rate during both years, CONTROL tree growth slowed dramatically in 2012, as did survival rate, in line with the results of Coll et al. (2007) in hybrid poplar plantations established in forest sites. The ranking of treatment performance (HERBICIDE > mulching > CONTROL) was consistent throughout the period (Fig. 1).

With regard to plant and soil water status, HERBICIDE yielded better results than mulching during the driest year of the study period (2012), probably owing to the sparse rainfall episodes in that summer, which may have limited the amount of water reaching the soil in mulched trees. A similar situation was observed by Ceacero et al. (2012) in a dry year in southern Spain. However, during wet years (2014) only HERBICIDE only provided better plant water status than CONTROL, while not being consistently better than any of the mulch models. Similarly, in areas with moderate-to-high water availability, such as Central USA (Maggard et al. 2012) or in irrigated orchards in NW India (Thakur et al. 2012) and SW Russia (Solomakhin et al. 2012), mulching did not result in lower soil water content than after herbicide application. On the other hand, mulching increased soil moisture compared with CONTROL during warm dry years (2012) as a result of buffered maximum temperatures, lower evaporation and decreased transpiration due to weed suppression (Barajas-Guzmán et al. 2006; Zhang et al. 2009; Maggard et al. 2012; McConkey et al. 2012). The lack of effect of any treatment on the SPAD measurements indicates that weed competition did not affect the chlorophyll content of walnut leaves, a variable closely related to nutritional status, especially with regard to nitrogen. This was also found by Cregg et al. (2009) after 2 years with both polyethylene and chip mulches. In addition, the process of degradation of chip mulches did not lead to either an increase or a decrease in nitrogen content at plant level. Nitrogen release may be expected in subsequent years, especially with RAMIALCHIPS, composed mostly of thin branches of both broadleaf and conifer species, while nitrogen shortage is more likely with WOODCHIPS, rich in pine bark. Finally, the buffering effect of the mulches on extreme temperatures was especially noticeable in the case of chip mulches (WOODCHIPS, RAMIALCHIPS) in all seasons, in line with Cregg et al. (2009); Barajas-Guzmán and Barradas (2011) and Arentoft et al. (2013). By contrast, film mulches (PLASTIC, BIOFILM) did not buffer, but instead increased maximal summer soil temperatures (Díaz-Pérez and Batal 2002; Díaz-Pérez et al. 2005).

The effectiveness of mulching techniques was evaluated after 40 months, a period long enough to let trees develop a root system and/or sufficient leaf area to shade and mitigate weed development unaided (Coll et al. 2003; Devine et al. 2007), and thus adequate to estimate whether or not the mulches had reached their expected service life (Coello and Piqué 2016). PLASTIC mulches were found to be especially durable, with 66% still effective (80% or more intact surface), as in Haywood (2000), who observed 70% of plastic mulches free of weeds after 5 years. RAMIALCHIPS and WOODCHIPS were close to the end of their service life in view of the incipient weed development on their areas, with roughly 50 and 40% of effective units, respectively. Finally, BIOFILM was approaching the end of acceptable service life, given that approximately one-third of the mulches fell into each of the three damage categories (effective, partially damaged or ineffective). This particular model of a pre-commercial prototype probably needs slight modification in composition or thickness to offer the desirable durability for afforestation in areas subject to higher sun and heat radiation.

These results correspond to a single trial installed in a homogeneous, flat field, representative of Mediterranean continental sub-humid conditions. However, they are to be complemented by further research in additional trials and pedoclimatic conditions in order to have more consistent results on the efficacy of the treatments tested.

Conclusion

Our study shows that on highly productive Mediterranean continental sites, weed control is critical for the success of valuable broadleaf plantations since it has a decisive effect on survival, growth and vigour of young seedlings. The optimized application of herbicides to late-flushing hybrid walnut gave the best results of all the techniques with regard to tree performance (all 5 years of study) and soil moisture (during dry years). However, mulching proved an effective alternative, especially considering that repeated weeding interventions are obviated, which could be a major advantage in minimal management schemes. The case of biodegradable mulches (biofilm, chips) is particularly beneficial in this regard, as they do not need to be removed at the end of their service life. This advantage, together with their composition based on waste or renewable raw materials, makes them a socially and environmentally valuable alternative to plastic mulching. However, further studies are needed to investigate the optimal properties of biodegradable mulches, both film and particle-based, in various sites, especially in terms of water balance (notably permeability) and durability. We also need to study, from an economic and operational point of view, the relation between the productive outcomes of each treatment and the inputs linked to their repeated application (e.g. herbicide) or need for removal (e.g. plastic mulching), compared with one-time mulch application (e.g. biodegradable models).

References

Abouziena HF, Hafez OM, El-Metwally IM, Sharma SD, Singh M (2008) Comparison of weed suppression and mandarin fruit yield and quality obtained with organic mulches, synthetic mulches, cultivation, and glyphosate. Hort Sci 43(3):795–799

Aletà N, Ninot A, Voltas J (2003) Caracterización del comportamiento agroforestal de doce genotipos de nogal (Juglans sp.) en dos localidades de Cataluña. For Syst 12(1):39–50

Álvarez-Chávez CR, Edwards S, Moure-Eraso R, Geiser K (2012) Sustainability of bio-based plastics: general comparative analysis and recommendations for improvement. J Clean Prod 23:47–56

Ammer C, Balandier P, Scott-Bentsen N, Coll L, Löf M (2011) Forest vegetation management under debate: an introduction. Eur J For Res 130:1–5

Arentoft BW, Ali A, Streibig JC, Andreasen C (2013) A new method to evaluate the weed-suppressing effect of mulches: a comparison between spruce bark and cocoa husk mulches. Weed Res 53(3):169–175

Barajas-Guzmán MG, Barradas VL (2011) Microclimate and sapling survival under organic and polyethylene mulch in a tropical dry deciduous forest. Bol Soc Bot Méx 88:27–34

Barajas-Guzmán MG, Campo J, Barradas VL (2006) Soil water, nutrient availability and sapling survival under organic and polyethylene mulch in a seasonally dry tropical forest. Plant Soil 287(1–2):347–357

Bond B, Grundy AC (2001) Non-chemical weed management in organic farming systems. Weed Res 41:383–405

Ceacero CJ, Díaz-Hernández JL, del Campo AD, Navarro-Cerrillo RM (2012) Evaluación temprana de técnicas de restauración forestal mediante fluorescencia de la clorofila y diagnóstico de vitalidad de brinzales de encina (Quercus ilex sub. ballota). Bosque 33(2):191–202

Chaar H, Mechergui T, Khouaja A, Abid H (2008) Effects of treeshelters and polyethylene mulch sheets on survival and growth of cork oak (Quercus suber L.) seedlings planted in northwestern Tunisia. For Ecol Manage 256:722–731

Chalker-Scott L (2007) Impact of mulches on landscape plants and the environment—a review. J Environ Hort 25(4):239–249

Coello J, Piqué M (2016) Soil conditioners and groundcovers for sustainable and cost-efficient tree planting in Europe and the Mediterranean. Centre Tecnològic Forestal de Catalunya

Coello J, Piqué M, Vericat P (2009) Producció de fusta de qualitat: plantacions de noguera i cirerer: aproximació a les condicions catalanes - guia pràctica. Generalitat de Catalunya, Departament de Medi Ambient i Habitatge, Centre de la Propietat Forestal

Coll L, Balandier P, Picon-Cochard C, Prévosto B, Curt T (2003) Competition for water between beech seedlings and surrounding vegetation in different light and vegetation composition conditions. Ann For Sci 60:593–600

Coll L, Messier C, Delagrange S, Berninger F (2007) Growth, allocation and leaf gas exchanges of hybrid poplar plants in their establishment phase on previously forested sites: effect of different vegetation management techniques. Ann For Sci 64:275–285

Cregg BM, Nzokou P, Goldy R (2009) Growth and physiology of newly planted Fraser fir (Abies fraseri) and Colorado blue spruce (Picea pungens) Christmas trees in response to mulch and irrigation. Hort Sci 44(3):660–665

Devine WD, Harrington CA, Leonard LP (2007) Post-planting treatments increase growth of Oregon white oak (Quercus garryana Dougl. Ex Hook) Seedlings. Restor Ecol 15(2):212–222

Díaz-Pérez JC, Batal KD (2002) Coloured plastic film mulches affect tomato growth and yield via changes in root-zone temperature. J Am Soc Hort Sci 127(1):127–135

Díaz-Pérez JC, Phatak SC, Giddings D, Bertrand D, Mills HA (2005) Root zone temperature, plant growth, and fruit yield of tomatillo as affected by plastic film mulch. Hort Sci 40(5):1312–1319

Djumaeva D, Lamers JPA, Martius C, Vlek PLG (2012) Chlorophyll meters for monitoring foliar nitrogen in three tree species from arid Central Asia. J Arid Environ 85:41–45

Dodd IC, He J, Turnbull CGN, Lee SK, Critchley C (2000) The influence of supra-optimal root-zone temperatures on growth and stomatal conductance in Capsicum annuum L. J Expt Bot 51:239–248

Dumroese RK, Williams MI, Stanturf JA, St. Clair JB (2015) Considerations for restoring temperate forests of tomorrow: forest restoration, assisted migration, and bioengineering. New For 46:947–964

Finkenstadt VL, Tisserat B (2010) Poly(lactic acid) and Osage Orange wood fiber composites for agricultural mulch films. Ind Crops Prod 31(2):316–320

Garlotta D (2001) A literature review of poly(lactic acid). J Polym Environ 9:63–84

George BH, Brennan PD (2002) Herbicides are more cost-effective than alternative weed control methods for increasing early growth of Eucalyptus dunnii and Eucalyptus saligna. New For 24:147–163

Gilman EF, Grabosky J (2004) Mulch and planting depth affect live oak establishment. J Arboricult 30(5):311–317

Granatstein D, Mullinix K (2008) Mulching options for northwest organic and conventional orchards. Hort Sci 43(1):45–50

Green DS, Kruger EL, Stanosz GR (2003) Effects of polyethylene mulch in a short-rotation, poplar plantation vary with weed-control strategies, site quality and clone. For Ecol Manage 173:251–260

Haywood JD (2000) Mulch and hexazinone herbicide shorten the time longleaf pine seedlings are in the grass stage and increase height growth. New For 19(3):279–290

Iles A, Martin AN (2012) Expanding bioplastics production: sustainable business innovation in the chemical industry. J Clean Prod 45:38–49

Jacobs DF, Salifu KF, Seifert JR (2005) Growth and nutritional response of hardwood seedlings to controlled-release fertilization at outplanting. For Ecol Manage 214:28–39

Johansson K, Orlander G, Nilsson U (2006) Effects of mulching and insecticides on establishment and growth of Norway spruce. Can J For Res 36:2377–2385

Kilmartin RF, Peterson JR (1972) Rainfall–runoff regression with logarithmic transforms and zeros in the data. Water Resour Res 8(4):1096–1099

Kogan M, Alister C (2010) Glyphosate use in forest plantations. Chil J Agric Res 70(4):652–666

Kumar S, Dey P (2010) Effects of different mulches and irrigation methods on root growth, nutrient uptake, water-use efficiency and yield of strawberry. Sci Hort 127:318–324

Löf M, Dey DC, Navarro RM, Jacobs DF (2012) Mechanical site preparation for forest restoration. New For 43:825–848

Maggard AO, Will RE, Hennessey TC, McKinley CR, Cole JC (2012) Tree-based mulches influence soil properties and plant growth. Hort Technol 22(3):353–361

Martín-Vide J (1992) El Clima. Geografia General dels Països Catalans. Enciclopèdia Catalana, Barcelona

McConkey T, Bulmer C, Sanborn P (2012) Effectiveness of five soil reclamation and reforestation techniques on oil and gas well sites in northeastern British Columbia. Can J Soil Sci 92(1):165–177

Merwin IA, Hopkins MA, Byard RR (2001) Groundcover management influences nitrogen release, retention, and recycling in a New York apple orchard. Hort Sci 36(3):451

Ninyerola M, Pons X, Roure JM (2005) Atlas Climático Digital de la Península Ibérica. Metodología y aplicaciones en bioclimatología y geobotánica. Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona, Bellaterra

Oliet J, Puértolas J, Planelles R, Jacobs D (2013) Nutrient loading of forest tree seedlings to promote stress resistance and field performance: a Mediterranean perspective. New For 44(5):649–669

Olivera A, Bonet JA, Palacio L, Liu B, Colinas C (2014) Weed control modifies Tuber melanosporum mycelial expansion in young oak plantations. Ann For Sci 71(4):495–504

Pedlar JH, McKenney DW, Fraleigh S (2006) Planting black walnut in southern Ontario: midrotation assessment of growth, yield, and silvicultural treatments. Can J For Res 36(2):495–504

Percival GC, Gklavakis E, Noviss K (2009) The influence of pure mulches on survival, growth and vitality of containerised and field planted trees. J Environ Hort 27(4):200–206

Schott KM, Snively AEK, Landhäusser SM, Pinno BD (2016) Nutrient loaded seedlings reduce the need for field fertilization and vegetation management on boreal forest reclamation sites. New For 47(3):393–410

Shogren RL, Rousseau RJ (2005) Field testing of paper/polymerized vegetable oil mulches for enhancing growth of eastern cottonwood trees for pulp. For Ecol Manage 208:115–122

Solomakhin AA, Trunov YV, Blanke M, Noga G (2012) Organic mulch in apple tree rows as an alternative to herbicide and to improve fruit quality. Acta Hortic 933:513–522

Thakur A, Singh H, Jawandha SK, Kaur T (2012) Mulching and herbicides in peach: weed biomass, fruit yield, size, and quality. Biol Agric Hortic 28(4):280–290

Thiffault N, Roy V (2011) Living without herbicides in Quebec (Canada): historical context, current strategy, research and challenges in forest vegetation management. Eur J For Res 130(1):117–133

Uscola M, Salifu KF, Oliet JA, Jacobs DF (2015) An exponential fertilization dose response model to promote restoration of the Mediterranean oak Quercus ilex. New For 46:795–812

Vallejo RV, Smanis A, Chirino E, Fuentes D, Valdecantos A, Vilagrosa A (2012) Perspectives in dryland restoration: approaches for climate change adaptation. New For 43:561–579

Van Sambeek JW (2010) Database for estimating tree responses of walnut and other hardwoods to ground cover management practices. In: McNeil DL (ed), VI International Walnut Symposium

Van Sambeek JW, Garrett HE (2004) Ground cover management in walnut and other hardwood plantings. In: Michler CH, Pijut PM, Van Sambeek JW, Coggeshall MV, Seifert J, Woeste K, Overton R, Ponder F Jr. (eds) Proceedings of the 6th Walnut Council Research Symposium. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, North Central Research Station. St. Paul

Villar-Salvador P, Puértolas J, Cuesta B, Peñuelas JL, Uscola M, Heredia-Guerrero N, Rey Benayas JM (2012) Increase in size and nitrogen concentration enhances seedling survival in Mediterranean plantations. Insights from an ecophysiological conceptual model of plant survival. New For 43(5–6):755–770

Watson WT (2005) Influence of tree size on transplant establishment and growth. Hort Technol 15(1):118–122

Willoughby I, Balandier P, Bentsen NS, McCarthy N, Claridge J (eds) (2009) Forest vegetation management in Europe: current practice and future requirements. COST Off, Brussels

Zegada-Lizarazu W, Berliner PR (2011) The effects of the degree of soil cover with an impervious sheet on the establishment of tree seedlings in an arid environment. New For 42(1):1–17

Zhang S, Lovdahl L, Grip H, Tong Y, Yong X, Wang Q (2009) Effects of mulching and catch cropping on soil temperature, soil moisture and wheat yield on Loess Plateau of China. Soil Tillage Res 102:78–86

Acknowledgements

The experimental design was prepared in collaboration with Philippe Van Lerberghe (IDF-Midi-Pyrénées, France) and Eric Le Boulengé (UCL, Belgium). The authors thank Guillem Martí, Eduard Mauri, Sílvia Busquet, Carla Fuentes, Miquel Sala, Fernando Valencia, Rosalía Domínguez, Sónia Navarro, Àngel Cunill, Alejandro Borque, Sergio Martínez, Toni Gómez and Aleix Guillén for indispensable support during field trial design and/or data collection, Aitor Améztegui for support on data analysis and Terrezu SL and Groencreatie BVBA for providing the prototype biofilm for the trial.

Funding

This work was supported by project Poctefa 93/08 PIRINOBLE: Valuable broadleaves for restoring and enhancing economic development of rural areas: innovation and technology transfer on sustainable plantation techniques.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Coello, J., Coll, L. & Piqué, M. Can bioplastic or woodchip groundcover replace herbicides or plastic mulching for valuable broadleaf plantations in Mediterranean areas?. New Forests 48, 415–429 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11056-017-9567-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11056-017-9567-7