Abstract

This study investigates interpretations of the Japanese initial mora-based minimizer “X.Y...”-no “X”-no ji-mo ‘lit. even the letter “X” of “X.Y...”.’ Although initial mora-based minimizers have a literal interpretation of ji ‘letter’, they have a non-literal interpretation as well. The non-literal interpretation has several distinctive features that are not present in ordinary minimizers. First, it is highly productive in that various expressions can appear in the form “X.Y...”-no “X”-no ji. Second, non-literal minimizers typically co-occur with predicates that relate to knowledge, information, concepts, thought, and habituality, as seen in the corpus data (Balanced Corpus of Contemporary Written Japanese [BCCWJ]).

I argue that in the non-literal use, X refers to the minimum on the scale of the main predicate concerning “X.Y...”. I suggest that the non-literal use was developed as a result of the conventionalization of the pragmatic inference derived from the literal reading, and that the co-occurrence with predicates related to knowledge, information, knowledge, concepts, thought, or habituality is due to the interpretation of “X.Y...”, which were originally interpreted as letters as an abstract concept.

The theoretical implication of this study is that, in addition to a non-compositional (lexically specified) minimizer whose scale is lexically fixed (e.g., give a damn, lift a finger), there also exists a compositional (lexically unspecified) minimizer in natural language, whose scale is specified via the predicate with which the minimizer co-occurs. The last section of this paper briefly discusses similar/related phenomena in Bosnian/Croatian/Serbian, Korean, and English from a cross-linguistic perspective.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Many expressions in natural languages can be used to emphasize negation, including so-called minimizers. A minimizer (which behaves as a negative polarity item [NPI]) is a word or phrase denoting a very small quantity and usually appears in a negative sentence to reinforce the negation. It is an emphatic way of expressing ‘zero’ (Bolinger 1972, p. 120) and represents the presence of no quantity at all (Horn 1989, p. 400). For example, a word or a bit in English and hito-koto-mo ‘even a word/single comment’ or sukoshi-mo ‘even a bit’ in Japanese are typical minimizers:

-

(1)

(English)

-

a.

The spokesman didn’t say a word about the earthquake.

-

b.

Mary didn’t drink a bit of water.

-

a.

-

(2)

(Japanese)

These minimizers are used at the level of specific words or phrases.

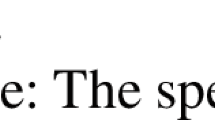

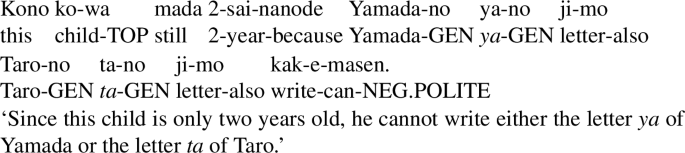

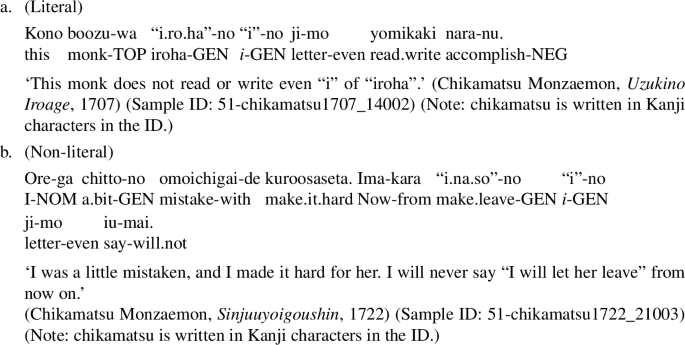

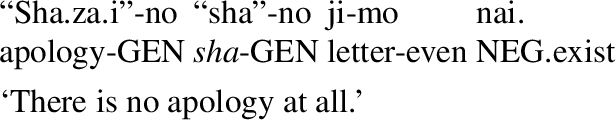

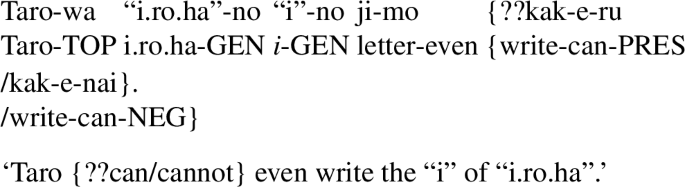

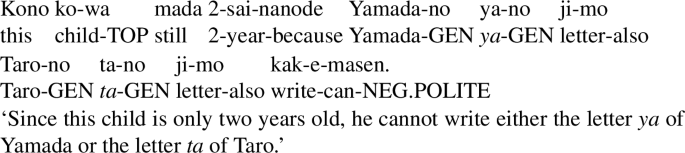

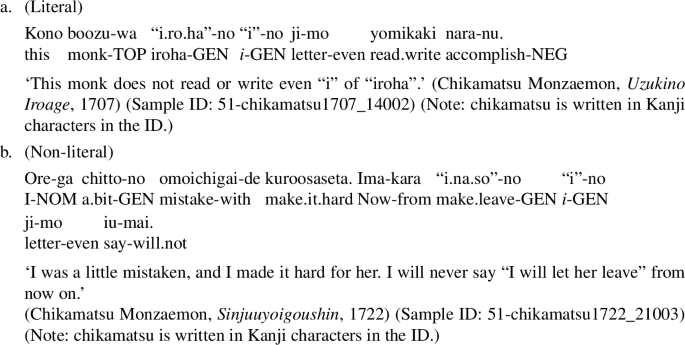

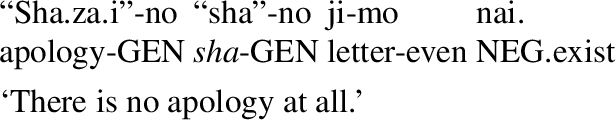

However, there exists a mora-based minimizer in Japanese, in the form “X.Y...”-no X-no ji-mo ‘lit. even the letter X of “X.Y...’’’, where “X.Y...” represents some arbitrary word consisting of two or more moras, and X corresponds to the first mora. There are two types of initial mora-based minimizers: literal and non-literal. In the following example, the initial mora-based minimizer is interpreted literally:

-

(3)

(Initial mora-based minimizer, literal)

In contrast, in the following examples, initial mora-based minimizer is non-literal:

-

(4)

In (4), ge.n.go.ga.ku-no ge-no ji and ka.i.sa.n-no ka-no ji are interpreted non-literally.Footnote 1 In other words, (4a) means that “Taro does not even have minimal knowledge of linguistics”, and (4b) means that “The prime minister is not thinking about a breakup at all”. In (4b), the word ji ‘letter’ cannot be interpreted literally. Since the minimizers in (3) and (4) are made based on an initial mora of a target expression, I call the minimizers in (3) and (4) an initial mora-based minimizer (or mora-based minimizer for short) in this paper.

The non-literal initial mora-based minimizer has several distinctive properties that normal minimizers do not. First, although the initial mora-based minimizer is idiomatic in nature, it is highly productive, and its scalar meaning is not specific. This lack of specificity is radically different from typical idiomatic minimizers. For example, the English lift a finger and give a damn are typical minimizers and they each have a specific idiomatic meaning:

-

(5)

-

a.

He never lifted a finger to get Jimmy released from prison. (Oxford Dictionary of English)

-

b.

People who don’t give a damn about the environment. (Oxford Dictionary of English)

-

a.

Descriptively, lift a finger means “to make the slightest effort to do something (especially to help someone)” and posits a scale of effort; give a damn means “to take a minimum degree of care” and posits a scale of care. Each has a specific form and specific scalar meaning. The non-literal initial mora-based minimizer is special because although its meanings are highly idiomatic, the formation is rule-based and its scalar meanings are non-specific. That is, its scale is specified by the interaction with the main predicate. For example, gengogaku-no ge-no ji-mo ‘the letter ge of gengogaku (linguistics)’ is not a fixed expression in itself. It just happens to be that form because gengogaku ‘linguistics’ is the input for “X.Y...”. Furthermore, unlike lift a finger and give a damn, non-literal mora-based minimizers do not have specific scalar meanings. For example, in (4a) the scale of the amount of knowledge is posited, but if we change the verb from shira-nai ‘don’t know’ to hanasa-nai ‘don’t speak’, (4a) can be interpreted as “Taro didn’t speak about linguistics at all”. The scale now concerns the amount of information transmission, which is different from the one related to the amount of knowledge.

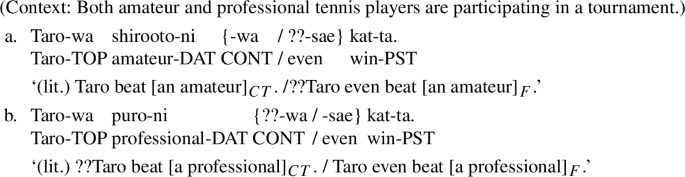

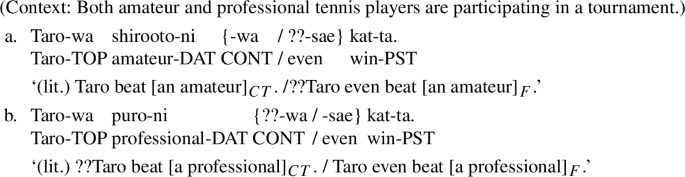

Another unique feature of non-literal initial mora-based minimizers is that although they are highly productive, they are restricted in terms of the types of predicate they can co-occur with.

For example, although it can co-occur with predicates related to information or knowledge (e.g., iwa-nai ‘don’t say’, shi-ttei-nai ‘don’t know’) as in (4), the mora-based minimizer cannot co-occur with predicates such as tabe-ru ‘eat’, nom-u ‘drink’ as in (6) and (7). This clearly is in contrast with ordinary minimizers such as a “1-classifier plus mo”:

-

(6)

-

(7)

What exactly does a non-literal initial mora-based minimizer mean? Is there a relationship between the literal and non-literal minimizers, in terms of meaning? How can we account for the distribution patterns of the non-literal mora-based minimizer? What do the differences between the non-literal initial mora-based minimizer and other minimizers suggest for research on minimizers?

In this study, I investigate the meaning and interpretation of the non-literal initial mora-based minimizer in Japanese, and claim that it has fundamentally different properties from ordinary minimizers in terms of scalarity and compositionality. I argue that it belongs to a new category in the typology/classification of minimizers.

After reviewing previous descriptive studies of the mora-based minimizer and its basic property as an NPI in Sect. 2, I consider the difference between the literal and non-literal mora-based minimizers based on various diagnostics, including the predicate-argument relationship, a denial test, and the behavior of a single Chinese character with multiple moras.

In Sect. 3, I look at the distribution pattern of the initial mora-based minimizer using corpus data (Balanced Corpus of Contemporary Written Japanese, or BCCWJ), and confirm that the non-literal minimizer tends to co-occur with predicates related to knowledge, information, concepts, thought, and habituality. At the same time, we observe cases in which seemingly literal usages are interpreted as having non-literal meanings.

To explain these phenomena, I base my arguments on the invited inference theory of semantic change (Traugott and Dasher 2002) that (i) the non-literal mora-based minimizer was developed by the conventionalization of a pragmatic inference derived from the sentence with a literal reading, and (ii) the co-occurrence with predicates related to knowledge, information, concepts, etc. is due to the interpretation of the target “X.Y...” originally interpreted as letters as an abstract concept.

In Sects. 4 and 5, I formally analyze the meaning of the literal and non-literal initial mora-based minimizers based on Chierchia’s (2013) alternative semantics-based analysis of minimizers/NPIs and the theory of quotation (Potts 2007) (for the semantics of the non-literal minimizer). In the form “α-no β-no ji”, the literal mora-based minimizer requires that β corresponds to the first mora of the target α and β is construed as the minimum on a scale arranged according to the phonological sequence in α. In contrast, the non-literal mora-based minimizer requires that β corresponds to the first mora of the target α and β refers to the minimum degree concerning β on the scale associated with the predicate (which measures the degree of {knowledge, information, concept, thought, habituality}). These points suggest that to interpret the minimum value of “α-no β-no ji”, we need to posit a mechanism that captures the relationship between sound and meaning (scale).

In this paper, I extend the lexical approach to NPI/minimizers proposed in Chierchia (2013) (where each NPI/minimizer is assumed to have a lexical requirement with regard to the type of alternatives [scalar alternatives/domain alternatives]), and argue that mora-based minimizers have a broader set of requirements, based on the syntactic frame of “α-no β-no ji”. The literal minimizer involves a lexical constraint on phonology. On the other hand, the non-literal minimizer not only involves a phonological constraint, but also constraints on syntax and semantics (constraints on the nature of α and the scalar properties of β and the predicate). These constraints allow us to properly interpret the meaning of certain forms of the mora-based minimizer, derive its alternatives, and explain the distribution patterns of the non-literal initial mora-base minimizer.

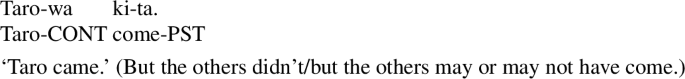

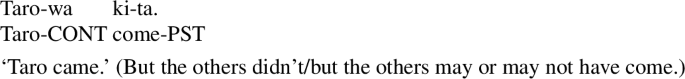

Note that there are also mora-based minimizers that behave as positive polarity items (PPIs). In Sect. 6, I show that if a (scalar) contrastive wa is used (rather than mo), the mora-based minimizer becomes a PPI, and its meaning can be compositionally derived in a systematic manner.

The phenomenon of mora-based minimizers is cross-linguistically important. In Sect. 7, I show that the phenomenon is not unique to Japanese, but can be found in Korean and Bosnian/Croatian/Serbian. In this study, I also discuss a phenomenon that is seemingly similar to, but different from, mora-based minimizers.

As a theoretical implication, this paper suggests that in addition to non-compositional (lexically specified) minimizers whose scale is lexically fixed (e.g., give a damn, lift a finger), 1-classifier-mo ‘even 1 classifier’), there are compositional (lexically unspecified) minimizers in natural language whose scale is specified via the information contained in the main predicate. This paper also provides a new perspective on the variation of the lexical requirements of minimizers, in terms of the interface between sound and meaning.

2 Some preliminary empirical discussions

In this section, I discuss the existing work on mora-based minimizers, and then look at their basic properties as polarity-sensitive items.

2.1 Previous descriptive studies of mora-based minimizers

Although little research has been conducted on mora-based minimizers, some descriptive observations have been made, especially regarding their phonetic and phonological properties.

Niino (1993) briefly mentions that a mora-based minimizer corresponds to a “frame idiom” (productive idiom) that contains varying parts, based on the following example:

-

(8)

(Non-literal reading)

Niino (1993) claims that “A-no B-no ji-mo nai” is a productive idiom that includes varying parts (wakugumiteki kanyooku ‘frame idiom’) (Kunihiro 1989). The meaning of “A-no B-no ji-mo nai” is a total denial of the existence of A (where A is a word, and B is the first syllable of A).

Okajima (1996) comments on Niino’s (1993) observations with additional examples in a post on his homepage on August 22, 1996 (http://www.let.osaka-u.ac.jp/~okajima/menicuita/9608.htm#22), stating that B corresponds to a mora rather than to a syllable. If B corresponds to a syllable, B can be “kon” rather than “ko”, but as the following example shows, B cannot be “kon”:

-

(9)

(Non-literal reading)

Notably, mora-based minimizers are somewhat similar to metalinguistic focus (Selkirk 1984; Rochemont 1986; Artstein 2004; Li 2017), as exemplified below:

-

(10)

(Context: Both stalagmites and stalactites are salient)

John only brought home a stalagMITE from the cave. (Artstein 2004: 2)

-

(11)

(Mandarin)

In (10) and (11), the focus is placed below the word level. In this sense, the metalinguistic focus is similar to a mora-based minimizer. However, the two differ in that the former has the pragmatic function of correction. Furthermore, unlike the metalinguistic focus, the rule always targets the first mora of a word with a mora-based minimizer. Therefore, there are some differences between metalinguistic focus and mora-based minimizers.

2.2 Note on the polarity sensitivity of mora-based minimizers

Before considering the meaning and interpretation of mora-based minimizers, I would like to confirm certain aspects of their polarity sensitivity.

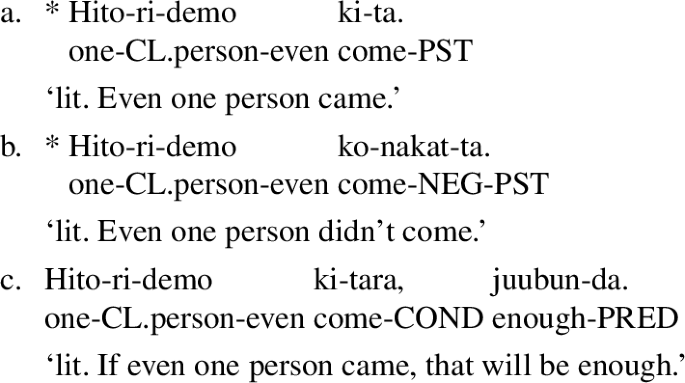

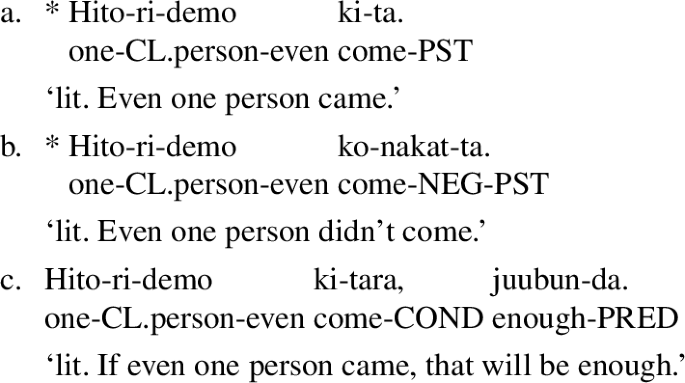

First, the mora-based minimizer “X.Y...no X-no ji-mo” is an NPI. As observed earlier, it cannot appear in a positive environment:

-

(12)

(Literal)Footnote 2

-

(13)

(Non-literal)

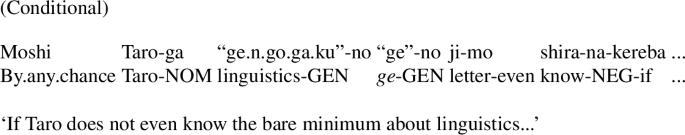

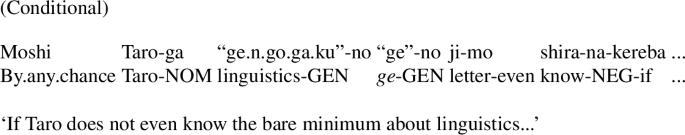

More specifically, it is a strict NPI (Giannakidou 2011), as it is only allowed with negation. For example, it cannot appear in downward-entailing or non-veridical environments, such as the antecedent of a conditional or a question:Footnote 3,Footnote 4

-

(14)

(Conditional)

-

(15)

(Question)

With the mora-based minimizer, mo plays an important role in its behavior as an NPI.Footnote 5 If mo is omitted and an appropriate case marker is inserted, the polarity sensitivity disappears and i-no ji means ‘letter i’:

-

(16)

In the case of the non-literal minimizer, if there is no scalar particle mo, the sentence becomes ungrammatical:

-

(17)

(Non-literal)

Although this study focuses on minimizer NPIs with mo, there are also mora-based NPIs that involve the exceptive shika ‘only’:

-

(18)

As the translations show, shika...nai can be paraphrased as sentences using “only.” Compared to minimizer NPIs with mo, mora-based minimizers with shika are much less frequent, but the existence of this co-occurence suggests that mora-based minimizer NPIs are highly compositional and systematic.Footnote 6

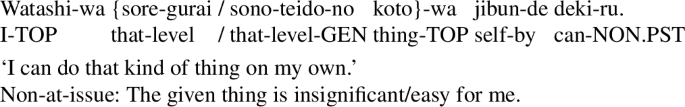

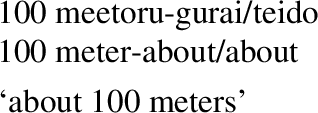

Furthermore, as I discuss in Sect. 6, the mora-based minimizer can be used as a PPI. If contrastive wa and degree expressions such as teido ‘degree’ or gurai ‘level’ co-occur with X.Y..-no X-no ji (instead of mo), it functions as a PPI:

-

(19)

(With contrastive wa and gurai/teido)

I discuss this phenomenon in Sect. 6.

3 Literal and non-literal mora-based minimizers

In this section, I consider the differences between literal and non-literal mora-based minimizers based on various diagnostics. We also look at the distribution patterns of each based on the BCCWJ corpus, and discuss the manner in which the non-literal mora-based minimizer developed.

3.1 The diagnostics for literal vs. non-literal readings

Let us first consider the difference between the two readings of the mora-based minimizer. Several empirical diagnostics distinguish between these two readings.

The first diagnostic concerns predicate-argument relationship. In the case of the literal use, ji ‘letter’ is construed as an argument of the main predicate.

-

(20)

(Literal reading)

As a reviewer pointed out, ji naturally co-occurs with the verbs kaku ‘write’ or nai ‘do not exist’, but not usually with verbs such as kangaeru ‘think’ and iu ‘say’:

-

(21)

-

a.

ji-o kaku ‘letter-ACC write’; ji-ga nai ‘letter-NOM not.exist’

-

b.

#ji-o kangaeru ‘letter-ACC think’; #ji-o iu ‘letter-ACC say’

-

a.

However, in the non-literal use, it naturally co-occurs with verbs such as kangaeru ‘think’ and iu ‘say’. The following sentences are natural, even though at the literal level, the verbs kangaeru ‘think’ and iu ‘say’ usually cannot take ji ‘letter’ as an argument:

-

(22)

(Non-literal reading)

In these examples, ji is not interpreted literally. In (22a), “ka” denotes a minimum level of thought about a breakup, and in (22b), “he” denotes a minimum mention of the Henoko District.

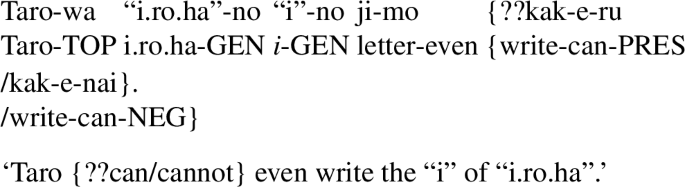

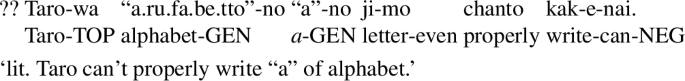

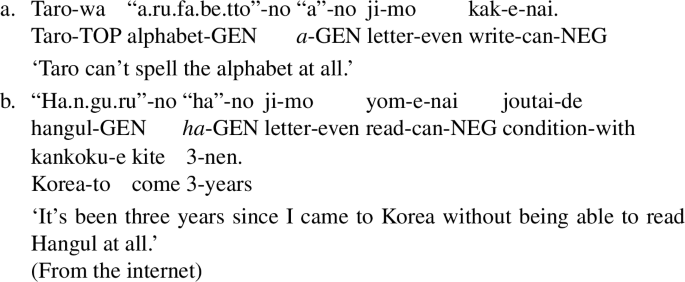

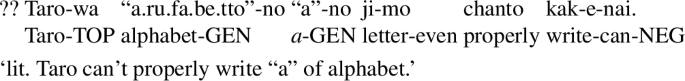

The diagnosis, based on the relationship between arguments and predicates, seems to be clear. However, it is not a perfect test because some instances of the seemingly literal minimizer behave like non-literal instances. The following sentences may appear to have a literal reading, but should be considered to be non-literal:

-

(23)

(Non-literal reading)

(23a) conveys that Taro cannot spell the alphabet at all, and (23b) conveys that the speaker cannot read any Hangul. Here “a” in (23a) and “ha” in (23b) cannot be interpreted literally, even though ji can be an argument of the verbs kak-u ‘write’ and yom-u ‘read’. (Note that the letter ‘a’ in the English alphabet is pronounced /ei/.) These examples should be analyzed as non-literal.Footnote 7 I return to these seemingly puzzling examples in Sect. 3.2 and discuss the relationship between literal and non-literal minimizers.

The second diagnostic involves a denial test. The literal reading of a minimizer can be denied. For example, in (24), if a hearer says Iya, sore-wa uso-da ‘No, that’s false’ in Japanese after (24A), then the denial is interpreted as a rejection of the idea that Taro cannot write the letter “i” (hiragana i). The hearer can reply by saying “He can write ‘i.’’’:

-

(24)

(Literal reading)

In contrast, in (25), the denial rejects the non-literal meaning of A’s utterance, as given below:

-

(25)

(Non-literal reading)

Here Speaker B is rejecting the idea that Taro does not know anything about linguistics.

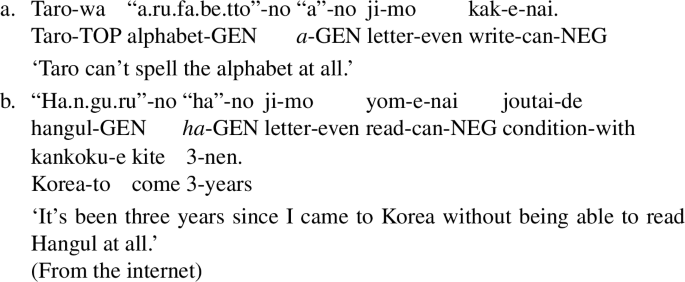

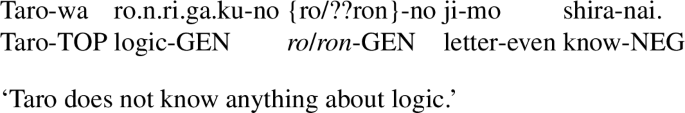

The third diagnostic is concerned with the possibility of using a Chinese character with multiple moras. For literal readings, the X in “X-no Y-no ji” could actually be a single Chinese character with multiple moras. For example, the proper name Keita has three moras (three hiragana), “ke.i.ta,” and consists of two Chinese characters (kanji), [kei][ta]. In this case, either “ke” or “kei” could be X under a literal reading:

-

(26)

(Literal reading)

In contrast, only mora-based formations are possible in non-literal readings. For example, ronrigaku ‘logic’ has five moras (ro.n.ri.ga.ku) and is written with three Chinese characters, [ron][ri][gaku]. To employ this word in a non-literal use of the “X.Y...”-no “X”-no ji” expression (= mora-based), X must be “ro” (not “ron”):

-

(27)

(Non-literal reading)

Finally, let us consider literal and non-literal minimizers in terms of the meaning of mo. As a reviewer suggested, in when non-literal, mo is interpreted as ‘even’, but in the literal interpretation, mo could in principle be interpreted as ‘also’ in addition to ‘even’. For example, in the literal use, “X.Y...”-no “X”-no ji can be used in the additive non-scalar A-mo B-mo ‘either A or B’ construction:

-

(28)

This suggests that when interpreted literally, “α-no β-no ji-mo” itself is not dedicated to a minimizer.

Based on the above diagnostics, it is safe to consider that there is a difference between the literal and non-literal readings, which manifests in terms of both, meaning and formation.

3.2 Corpus data: extension from literal to non-literal

In the previous section, I discussed the difference between literal and non-literal readings of the mora-based minimizer based on several diagnostics. In this section, I examine the environment in which the mora-based minimizer occurs, using BCCWJ data and discuss the relationship between the literal and non-literal interpretations.

As elucidated in the previous section, the non-literal mora-based minimizer can co-occur with predicates that do not take ji ‘letter’ as an argument (in the literal sense). However, this does not imply that they can be used in any negative environment. The following sentences show that the mora-based minimizer naturally co-occurs with the verb shi-tei-ru ‘know’, but not with tabe-ru ‘eat’:

-

(29)

The non-literal mora-based minimizer typically co-occurs with predicates involving knowledge or information, such as shit-teiru ‘know’ or i-u ‘say’.

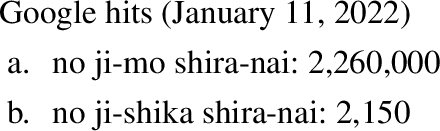

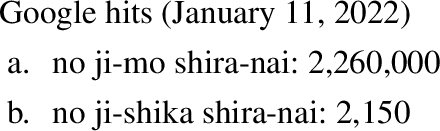

To check the environment of the mora-based minimizer, its environment was investigated using the BCCWJ corpus. In the BCCWJ corpus, I used the string search function to look for examples that match the string “no ji-mo”. This yielded 75 examples in which “no ji-mo” had been used as of February 4, 2020. Of these, 53 were examples of the word being used as a mora-based minimizer and 22 were unrelated to the mora-based minimizer.

The following table summarizes the environment in which the mora-based minimizer example occurs, in terms of predicate type and the distinction between literal and non-literal readings:

-

(30)

Predicate

Non-literal

Literal (or ambiguous)

Total frequency

1.

shira-nai ‘do not know’

13

1

14

2.

nai ‘do not exist’ (information, concept, emotion)

7

3

10

3.

de-nai ‘(information) does not appear, is not brought up’

4

4

4.

dete ko-nai ‘(information) does not appear, is not brought up’

3

1

4

5.

iwa-nai ‘do not say’

2

2

6.

kuchi-ni shi-nai ‘do not say’

2

2

7.

shi-nai ‘do not do something (habitually)’

2

2

8.

hai-tte i-nai ‘not including’

1

1

2

9.

miatara-nai ‘cannot find’

2

2

10.

kuchi-ni dasoo-to shi-nai ‘do not want to say’

1

1

11.

de-te i-nai ‘there is no’ (appearance)

1

1

12.

kokoroe-nai ‘do not know’

1

1

13.

wakara-nai ‘do not understand’

1

1

14.

omoi ukaba-nai ‘do not come to mind’

1

1

15.

ukagaw-ase-nai ‘do not give indication’

1

1

16.

toujou shi-nai ‘do not appear’

1

1

17.

mira-re-nai ‘cannot be seen’

1

1

18.

mi-taku-nai ‘do not want to see’

1

1

19.

kiji-ni nara-nai ‘do not become an article’

1

1

20.

agara-nai ‘increase’

1

1

The above table shows that there is a certain tendency for predicates to co-occur with the mora-based minimizer. Namely, the predicates that co-occur with the mora-based minimizer tend to be related to knowledge, information, and concepts/properties.

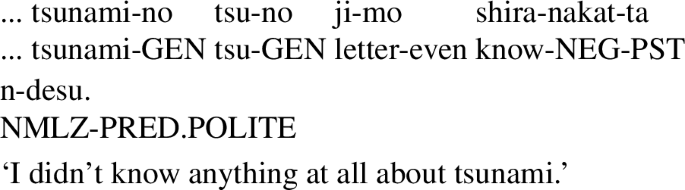

The most frequent negative predicate was shira-nai ‘don’t know’, 12 of the 13 cases of which were interpreted as non-literal, and only 1 could be interpreted as literal. The following are examples from the corpus:

-

(31)

(Non-literal)

I classified the following example as literal, but the sentence is, in fact, ambiguous and can have a literal or non-literal reading, depending on context:

-

(32)

(Literal)

I, ro, and ha are the first three letters of the old-style Japanese hiragana order (appearing at the beginning of a poem), but iroha can mean the entire hiragana system, and if we interpret iroha in the latter sense, then the above sentence can be interpreted in a non-literal way. (As I discuss later, iroha can also mean “the basics/the rudiments”.)

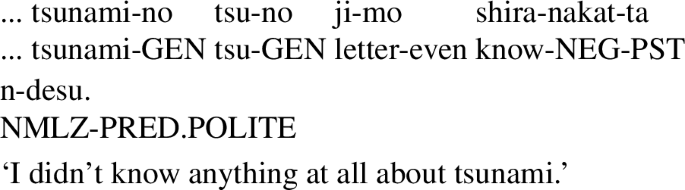

The next most frequent predicate is the negative predicate nai ‘do not exist’. In the data, this predicate is used to describe the absence of concepts, feelings, or properties:

-

(33)

The predicates de-nai ‘do not appear’ and dete ko-nai ‘do not come up’ also appear frequently with the mora-based minimizer and, importantly, are usually used in the context of information. The following is an example of de-nai ‘do not appear’ from BCCWJ:

-

(34)

(Absence of information)

Predicates such as iwa-nai ‘do not say’ and kuchi-ni shi-nai ‘do not say’ were also noticeable, as shown below:Footnote 8

-

(35)

Examples of the verb suru ‘do’ were also found in the corpus. Note that suru ‘do’ here refers to a habitual action, and the sentences in which they were used represent a complete lack of habituality:

-

(36)

Lack of habituality seems to be similar to lack of concepts/knowledge.

The above corpus data clearly show that the non-literal mora-based minimizer tends to co-occur with predicates that relate to information, knowledge, concepts, or habituality.

Let us now discuss the relationship between literal and non-literal uses. Non-literal use was predominant, but some examples could be considered to be literal. Interestingly, there were examples that suggested an extension from a literal reading to a non-literal reading. As shown in the above table, there are several examples classified as literal, but most of them can also be interpreted non-literally (ambiguous between literal and non-literal readings).

In the previous section, I proposed a criterion for whether ji ‘lit. letter’ can be an argument for a main predicate, as one of the diagnostics for distinguishing between literal and non-literal minimizers. If ji is construed as an argument of a predicate, the minimizer is literal. However, if ji is not construed as an argument of a predicate (at a literal level), then the minimizer is non-literal. This diagnostic was used to classify the uses of corpus data. However, careful observation of their meanings shows that there are cases in which the examples classified as literal (via the diagnostic) appear to be interpreted non-literally.

-

(37)

It is true that the predicates dete ko-nai ‘does not appear’, mi-taku-nai ‘do not want to see’, and nai ‘do not exist/there is no’ can take ji as their arguments. However, these examples seem to be interpreted non-literally. In fact, if we apply the second diagnostic (a denial test), we see that they behave like the non-literal mora-based minimizer. In the previous section, I argued (as a second diagnostic) that the literal mora-based minimizer, unlike non-literal one, can literally object to the “X-no-ji” part. However, as can be seen in the example below, no objection can be made to the literal meaning:

-

(38)

Theoretically, there can be a literal reading in (38B), but it would be unnatural from a pragmatic point of view. In this context, A and B are talking about Shiberia ‘Siberia’, and it does not make sense to only focus on ‘shi’.Footnote 9

To object to A’s utterance, we need to object to the idea that there is no information about Siberia in the song at all. Given that there can be various pieces of information about Siberia, the ways of objection are also multiple:

-

(39)

This point is radically different from that of the literal minimizer. As discussed in the previous section, with the literal minimizer, it is possible to object to the literal meaning of X-no ji:

-

(40)

(Literal reading)

The other three examples in (37) also cannot be objected to on a literal level. Thus, according to the diagnostics discussed in Sect. 3.1, the examples in (37) have the characteristics of both literal and non-literal mora-based minimizers. They are literal when viewed from the diagnostic of a predicate-argument structure, but when viewed from the denial test, they are construed as non-literal. These examples suggest something important when thinking about the relationship between literal and non-literal readings. These examples can be considered as intermediates between the two types (the source of the development of the non-literal reading).

In this study, I propose that the non-literal meaning was originally a purely pragmatic inference drawn from the literal mora-based minimizer and the mora-based minimizer (as an independent expression) developed because of the conventionalization of pragmatic inference (drawn from the literal meaning).

This idea is compatible with the theory of the so-called invited inference theory of semantic change (Traugott and Dasher 2002; Traugott and König 1991; Hopper and Closs Traugott 2003). The central idea of this theory is that semantic change proceeds through the conventionalization of pragmatic inference (see also Geis and Zwicky 1971). More specifically, Traugott and Dasher (2002) assumed the following steps:

-

(41)

-

a.

In the first stage, an item L possesses a coded meaning M.

-

b.

In concrete utterance situations, this item L can be used in sentences that give rise to certain pragmatic implicatures, referred to as Invited Inferences (IIN).

-

c.

These inferences are exploited innovatively in the associative stream of speech and re-weighted.

-

d.

These processes eventually lead to the conventionalization of certain inferences for sentences that contain the item L. (These conventionalized inferences are also called generalized invited inferences (GIIN).)

-

e.

Finally, in Stage II, the conventionalized invited inferences give rise to a new coded meaning for item L, which is ambiguous between meaning M and (new) meaning M. (Traugott and Dasher 2002, p. 38; Eckardt2006, p. 40)

-

a.

This approach is metonymic in the sense that the “semanticization” of pragmatics involves a profile shift from pragmatic status to coding status. However, Traugott and Dasher (2002) considered that this metonymic shift may be enabled by metaphors that already exist and serve as frames for the shift, and may result in what synchronically appears to be metaphors.

Using the above idea of the conventionalization of pragmatic inference, I assume that the following stages are involved in the development of the non-literal mora-based minimizer:

-

(42)

-

a.

In stage I “X.Y...”-no “X”-no ji (= L) has a literal meaning (by applying the input of a particular expression) (M1).

-

b.

In concrete utterance by saying that even the first letter X of “XY...” is not P, the inference that “the degree about the target “X.Y...” on the scale of the predicate P is zero” arises as an invited inference.

-

c.

As a result of the frequent appearance of such inferences along with various concrete examples, the inference has conventionalized and “X.Y...”-no “X”-no ji (= L) acquired a new meaning—“the minimum degree about the target “X.Y...” on the scale of the predicate P” as M.

-

d.

As a result, in Stage II, the conventionalized invited inferences give rise to a new coded meaning for “X.Y...”-no “X”-no ji (= L), and it became ambiguous with \(M_{1}\) (lexical usage) and \(M_{2}\) (non-lexical usage).

-

a.

Let us consider the mechanism based on example (37a), repeated below:

-

(43)

(Context: The speaker talks about a singer who had a difficult experience in Siberia.)

In Stage I, although at the literal level, the sentence only means that “even the letter “shi” of “Shiberia” does not come up”, we obtain the non-lexical inference that there is no information about Siberia in the song at all.

This kind of inference is not lexical, but through a frequent appearance of such inferences among various other examples, “X.Y...”-no “X”-no ji (L) acquired a new meaning where “the minimum degree about the target “X.Y...” on the scale of the main predicate P” was independent of the literal meaning, and now Shiberia-no shi-no ji ‘the letter shi of Shiberia’ is interpreted as the minimum degree about Siberia, on the scale of information of appearance (Stage II).

“X.Y.. -no X-no ji” (L) is a schematic lexical item. It is likely that this conventionalization has occurred through various concrete examples. For example, the following example also seems to be able to invoke an invited inference (in Stage I):

-

(44)

(Context: It is rumored that the party was exploring the possibility of an armed struggle, but its inner workings are unclear.)

Literally, this sentence only means that not even the letter bu of busoutousou ‘armed struggles’ is present in the released document. However, from this sentence, we can infer that there is no information about armed struggles at all in the document. Now busoutousou-no bu-no ji ‘the letter bu of busoutousou (armed struggles)’ is interpreted as the minimum degree about armed struggles on the scale of information of appearance/existence (Stage II). Thus, through various examples, we can consider that a schematic non-literal meanings of the mora-based minimizer have been created.

Consequently, the non-literal mora-based minimizer can now co-occur with predicates that cannot take ji as their object:

-

(45)

In these examples, it is not necessary to go through two steps to understand the meaning of these sentences. In fact, in these sentences, there are no literal meanings; they only have a non-literal meaning (\(M_{2}\)). In (45a) eigo-no e-no ji ‘the letter e of eigo (English)’ makes reference to an ability scale and conveys that Taro does not have even minimal speaking ability in English, and in (45b) kaisan-no ka-no ji ‘the letter ka of kaisan (dissolution)’ makes reference to a possibility/thought scale, and conveys that the prime minister has not given the slightest thought about dissolution.

Due to conventionalization, this new non-literal mora-based minimizer can also be naturally applied to the cases discussed in the previous section. A literal interpretation is impossible for these, even though the verb (i.e., kak-u ‘write’, yom-u ‘read’) can take ji ‘letter’ as its argument:

-

(46)

In these examples, the sentences are interpreted directly based on the non-literal mora-based minimizer (not from a literal reading).

Here, I describe the meaning of the non-literal mora-based minimizer as follows:

-

(47)

The meaning of the non-literal mora-based minimizer (Descriptive): In the mora-based minimizer “X.Y...”-no “X”-no ji, X denotes a minimum degree with respect to the target “X.Y...” on the scale associated with a predicate that is related to knowledge, information, concepts, and so on.

In the next sections, I investigate how the meaning and environment of the non-literal mora-based minimizer can be analyzed theoretically. Section 5 attempts a more detailed analysis of the non-literal mora-based minimizer, including examples that do not appear in the corpus.Footnote 10

4 Formal analysis of the literal mora-based minimizer NPI

Let us now turn to a more theoretical discussion of the compositionality of the mora-based minimizer’s meaning. Before analyzing the non-literal mora-based minimizer, we first analyze the meaning of the literal minimizer.

-

(48)

(Literal)

An important property of the literal mora-based minimizer is that the scalar meaning is computed based on its interaction with phonology. That is, in the form α-no β-no ji, β must correspond to the first mora of the target α, and β must be interpreted as the minimum value on a scale arranged according to the phonological sequence of α.

In this paper, I extend Chierchia’s (2013) theory of NPIs/minimizers, which posits a lexical requirement regarding the kind of alternatives (scalar alternatives or domain alternatives), and argue that the mora-based minimizer has broader requirements/constraints on the relationship between sound and degree (scale) based on the syntactic frame. Before considering this, let us first briefly review Chierchia’s theory of NPIs. Chierchia’s approach is characterized by the fact that the kind of alternative activated may differ from one polarity item to another. In this theory, any scalar term (i.e., quantifiers, numerals, minimizers, and, or, etc.) carries a feature bundle made up of two unvalued components [uσ, uD] (or simply, [σ,D]) (Chierchia 2013, p. 126). The former corresponds to the strictly scalar alternatives and the latter to the domain alternatives. Domain alternatives are all subdomains of the domain of disjunction/existential quantification. Chierchia (2013) assumes that minimizers posit strictly scalar alternatives (having the feature σ), and domains are irrelevant to the semantics of minimizers (i.e., they do not carry a D feature). Based on the above assumption, Chierchia analyzes the meaning of the minimizer give a damn as in (49a), which obligatorily triggers a set of scalar alternatives as in (49b) (s stands for state and d is a context-dependent free variable):Footnote 11

-

(49)

-

a.

give a damn= \(\lambda x \exists s [\text{care}_{w} (s, x, d_{min})] \)

-

b.

ALT(give a damn) = {\(\lambda x \exists s [\text{care}_{w} (s, x, d')]: d' > d_{min}\) (Chierchia 2013, p. 150)

-

a.

In this system, when alternatives are activated, they must be exhaustified by an alternative sensitive operator. Chierchia (2013) discusses this operation in terms of feature checking. The minimizer [give a damn]σ has an unvalued feature σ that must be checked by an alternative sensitive operator. Note that there can be two possibilities for the kind of alternative sensitive operator, O (a null counterpart of only) or E (a null counterpart of even). However, in the case of minimizers, a set of alternatives must be exhaustified by the focus operator EVEN (rather than ONLY).Footnote 12,Footnote 13

How can we analyze the initial mora-based minimizer? Given that the initial mora-based minimizer co-occurs with EVEN in negative environments, it is natural to assume that it evokes a scalar alternative, but the problem is that such stipulation alone is not sufficient. The particular alternatives of the initial mora-based minimizer depend on the phonological string of the word in question, but the system has nothing to do with sound (phonology). However, given that we need to posit lexical constraints in any case, it is possible to further broaden it to the domain of phonology.

In this paper, I propose that the initial mora-based minimizer has additional requirements regarding the relationship between sound and scale as a syncategorematic rule in the syntactic frame “α-no β-no ji”, as in (50).Footnote 14 Based on the constraints, the ordinary semantic value (at-issue meaning) is interpreted, and its alternatives (the focus semantic value; Rooth 1992) are derived from the ordinary semantic value and focus marking, as in (50a) and (50b):

-

(50)

A set of alternatives is created by replacing the focused element β (the first mora of α) with elements of the same type (Rooth 1992). Given the phonological requirements that (i) α consists of an ordered list of moras and (ii) β is the initial mora in α, and the lexical requirement that the alternatives of the initial mora-based minimizer are strictly scalar (having the feature σ), it is possible to consider that the alternative x will be β itself and a series of moras which include β (contained in α). It is important to note that this type of mora-based scale (literal minimizer) is different from a typical scale. In the case of the literal mora-based minimizer, the linguistic expressions (morae) are ordered (not denotations/meanings).Footnote 15,Footnote 16

Let us consider the meaning of the literal mora-based minimizer in (48a). First, it can represent the lexical information of “i.ro.ha” as follows:

-

(51)

〈 [i.ro.ha]; NP; the first three letters of the old-style Japanese hiragana order: e 〉

(52) shows the ordinary and focus semantic values of “i.ro.ha”-no [“i”]-no ji:

-

(52)

-

a.

The ordinary semantic value of “i.ro.ha”-no [“i”]-no ji:

〚“i.ro.ha”-no [“i”]-no ji\(]\!\!]^{o}\) = the letter “i” of the word “i.ro.ha”

-

b.

The focus semantic value of “i.ro.ha”-no [“i”]-no ji:

〚“i.ro.ha”-no [“i”]-no ji\(]\!\!]^{f}\) = {the letter x of the word “i.ro.ha” : x is a mora or a series of moras contained in “i.ro.ha”}

= {“i”, “i.ro”, “i.ro.ha”}

-

a.

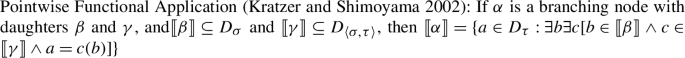

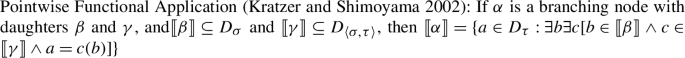

Here the alternatives of “i.ro.ha”-no “i” will be the set {“i”, “i.ro”, “i.ro.ha”}. The alternatives in (52) are computed in the same way as the ordinary semantic meaning, that is, in a pointwise manner (Kratzer and Shimoyama 2002), as shown in (53):Footnote 17

-

(53)

-

a.

at-issue propositional meaning: ¬ can(write(“i” of the word “i.ro.ha”) (Taro))

-

b.

alternatives: = {¬ can(write(“i” of the word “i.ro.ha”)(Taro)), ¬can(write(“i.ro” of the word “i.ro.ha”)(Taro)), ¬can(write(“i.ro.ha” of the word “i.ro.ha”)(Taro))}

-

a.

As for the meaning of mo ‘even’, building on the ideas of Karttunen and Peters (1979) and Lahiri (1998), I assume that mo morphosyntactically combines with X-no ji, but in the logical structure it behaves as a proposition taking an operator, as shown below:

-

(54)

I then assume that mo introduces a set of alternative propositions and presupposes that p is the most unlikely among the relevant alternatives (see also Karttunen and Peters 1979), as shown in (55) (mo also entails that p is an at-issue meaning):Footnote 18,Footnote 19

-

(55)

〚mo〛 = \(\lambda p:~\forall q[C(q) \wedge q \neq p \rightarrow p >_{unlikely} q].~p\)

Thus, in the final stage of semantic derivation, mo combines with the at-issue proposition in (53a), and we obtain both the at-issue meaning and scalar presupposition, as shown in (56):

-

(56)

〚mo〛 (〚¬ can(write(“i” of the word “i.ro.ha”, Taro))〛) =

∀q[C(q)∧q ≠ ¬can(write(“i” of the word “i.ro.ha”, Taro))→¬can(write(“i” of the word “i.ro.ha”, Taro)) \(>_{unlikely} q\)]. ¬ can(write(“i” of the word “i.ro.ha”, Taro))

The above analysis has important theoretical implications regarding the variations of alternatives in NPIs. By extending Chierchia’s idea of lexical stipulation for NPIs and establishing additional lexical requirements (constraints) for the phonological component, more complex types of minimizers can also be formally analyzed. In Sect. 5, to facilitate the interpretation of the non-literal initial mora-based minimizer, I extend the approach that lexical stipulation can be even broader and posit further constraints regarding the relationship between sound and meaning.

5 Formal analysis of the non-literal initial mora-based minimizer

We now analyze the meaning of the non-literal mora-based minimizer. In Sect. 5.1, we consider its structural, phonological, and semantic properties and analyze its compositionality, based on the idea of Potts’s quotation and alternative semantics. Sections 5.2 and 5.3 further extend the analysis of the non-literal mora-based minimizer when it co-occurs with an eventive noun or a speech act-oriented noun. Section 5.4 explains the distributional difference between the mora-based minimizer and other typical minimizers.

5.1 Compositionality of the non-literal minimizer

As shown in the following examples, the scalar meaning of the non-literal mora-based minimizer is specified by the information (scale structure) of the main predicate:

-

(57)

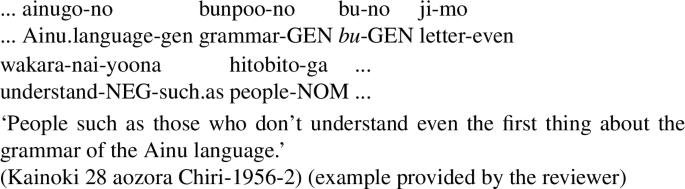

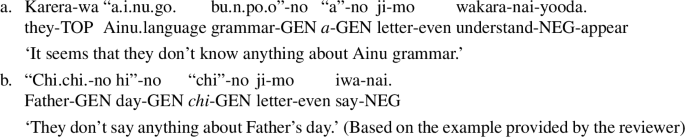

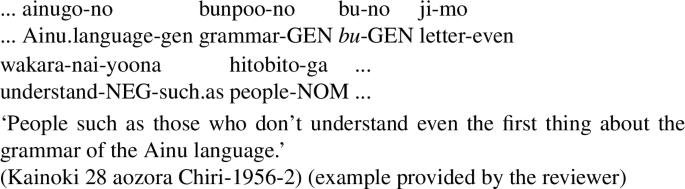

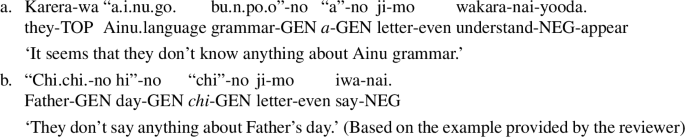

One point that needs to be clarified here is that α cannot be a compound expression containing a modifier and must be syntactically the head of an expression. This point becomes clear if we look at an example with a modifier. As a reviewer pointed out, although (58) is natural, (59) is not despite the fact that “a” is the first mora of the complex expression ainugo-no bunpoo ‘the grammar of the Ainu language’:

-

(58)

-

(59)

In the above examples, the syntactic head of the complex expression ainugo-no bunpoo ‘the grammar of the Ainu language’ is bunpoo ‘grammar’. Thus bunpoo corresponds to α and bu corresponds to β in the form “α-no β-no ji.”Footnote 20

Let us now consider how we can analyze the meaning of the non-literal initial mora-based minimizer. In the on-literal use of “α-no \([\beta ]_{F}\)-no ji”, β phonologically corresponds to the initial mora of α, similar to the literal use. However, semantically, β is not interpreted literally and is taken to be a minimal degree of a gradable predicate about the target α. For example, in (57a) “ge.n.go.ga.ku”-no “ge”-no ji ‘lit. the letter ge of ge.n.go.ga.ku (= linguistics)’ represents the minimum degree of knowledge about linguistics, and in (57b) “ka.i.ka.ku.”-no ka-no ji” ‘lit. the letter ka of ka.i.ka.ku (= reformulation)’ represents the minimum degree of talking about reform.

How can we capture the correspondence between sound and meaning in this schematic representation? In this paper, I use Potts’s (2007) idea of quotation. Potts (2007) assumes that linguistic entities are triples, 〈Π;Σ;α:τ〉, where Π is a phonological representation, Σ is a syntactic representation, and α is a semantic representation of type τ. Potts (2007) further assumes that it is possible to access the semantic representations in the triple, through the function SEM:

-

(60)

SEM (〈Π;Σ;α:τ〉) = α

(Potts 2007)

Building on Potts’s (2007) idea I assume that each of the phonological, semantic, and syntactic representations of a linguistic entity X can be accessed by the functions SYN, SEM, and PHON.

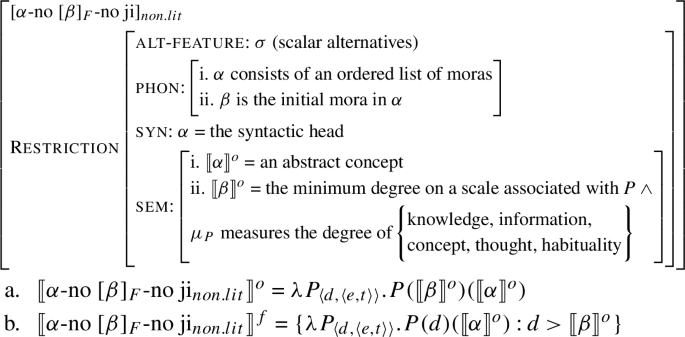

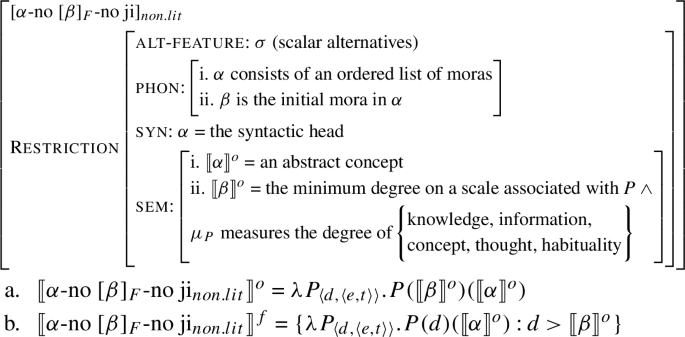

I propose that there are phonological, syntactic, and semantic constraints (as syncategorematic constraints) in the syntactic frame of the non-literal initial mora-based minimizer [ [X α]-no \([\beta ]_{F}\)-no ji]\(_{non.lit}\), as in (61):

-

(61)

(Syntactic frame of the non-literal initial-mora-based minimizer)

Let us consider each of these constraints one by one. First, the non-literal initial mora-based minimizer has a σ feature just like typical minimizers and posits strictly scalar alternatives. Second, there are phonological constraints that (i) α consists of an ordered list of moras, and (ii) \(\beta _{phon}\) is the first mora of \(\alpha _{phon}\). This phonological component is the same as that of the literal minimizer.

Next, as syntactic constraints, there are constraints that (i) α is the syntactic head, and (ii) X in [X α]-no is a possibly null expression embedded in the phrase headed by α. These syntactic constraints are necessary to ensure that α is not an expression containing a modifier. (Based on this constraint, we can explain the linguistic facts that the target α cannot be a compound expression containing a modifier.)

Finally, as a semantic constraint, there are restrictions that (i) \([\!\![\alpha ]\!\!]^{o}\) = an abstract concept and (ii) \([\!\![\beta ]\!\!]^{o}\) = the minimum degree on a scale associated with P and the measure function of P (i.e., \(\mu _{P}\)) measures the degree of {knowledge, information, concept, thought, habituality}. The first restriction, that the object be interpreted as an abstract concept, and the second one, regarding the type of predicate, appear to be interrelated. Ji, which originally meant letter, is now interpreted as a more abstract concept (relating to knowledge, information, thought, etc.).

The ordinary semantic value of the non-literal initial mora-based minimizer is interpreted based on these constraints, and the focus semantic value (alternatives) is derived based on the ordinary semantic value and focus marking. At the level of ordinary semantic value “α-no \([\beta ]_{F}\)-no ji\(_{non.lit}\)” takes a predicate P and an individual x, and returns \(P([\!\![\beta ]\!\!]^{o})([\!\![\alpha ]\!\!]^{o})(x)\). Here the predicate P is a three-place gradable predicate that takes β (the minimum degree), α (the object), and x (the subject). At the level of focus semantic value, “α-no \([\beta ]_{F}\)-no ji\(_{non.lit}\)” activates a set of alternatives. Formally, it is the set of “\(\lambda P_{\langle d, \langle e,\langle e, t\rangle \rangle \rangle }\) \(\lambda x. P(d)([\!\![\alpha ]\!\!]^{o})(x)\)” such that d is greater than \([\!\![\beta ]\!\!]^{o}\) (i.e., a minimum degree).

As a case study, let us consider the compositional mechanism of the non-literal mora-based minimizer, based on the following example:

-

(62)

(Non-literal)

First, I assume that gengogaku ‘linguistics’ has a representation like (63):

-

(63)

〈 [ge.n.go.ga.ku]; NP; linguistics: e 〉

(64) shows the ordinary and focus semantic values of “ge.n.go.ga.ku-no ge-no ji”:

-

(64)

(Constraints [relevant parts]: “ge.n.go.ga.ku” consists of an ordered lit of moras ∧ “ge” is the initial mora ∧ “ge.n.go.ga.ku” = the syntactic head ∧ “ge.n.go.ga.ku” = abstract concept \(\wedge \,[\!\![ge]\!\!]^{o}\) = the minimum degree on a scale associated with P ∧ \(\mu _{P}\) measures the degree of {knowledge, information, concept, thought, habituality})

-

a.

〚“ge.n.go.ga.ku”-no [“ge”]-no ji\(_{non.lit}]\!\!]^{o}\) = \(\lambda P \lambda x. P([\!\![ge]\!\!]^{o})(\text{linguistics})(x)\)

-

b.

〚“ge.n.go.ga.ku”-no [“ge”]-no ji\(_{non.lit} ]\!\!]^{f}\) = {\(\lambda P \lambda x. P(d)(\text{linguistics})(x): d > [\!\![ge]\!\!]^{o})\)}

-

a.

Note that “ge.n.go.ga.ku-no ge-no ji” itself does not inherently have a specific scale (dimension), and it is defined only through the relationship with the scale of P. For instance, in (62) the scale is concerned with knowledge. I define the meaning of shit-teiru as follows (\(\mu _{know}\) stands for the measure function of know):

-

(65)

〚shit-teiru〛: 〈d,〈e,〈e,t〉〉〉 = λdλxλy.know(y)(x) ≥ d

(where \(\mu _{know}\) measures the degree of knowledge)

The predicate shit-teiru ‘know’ takes a degree d and individuals x and y and denotes that x’s knowledge of y reaches at least d.

(66) shows the at-issue proposition and its alternatives:

-

(66)

-

a.

ordinary semantic value (at-issue proposition): ¬(know(Taro)(linguistics) ≥ \([\!\![ge]\!\!]^{o}\))

-

b.

focus semantic value (alternative propositions): {¬(know(Taro)(linguistics) \(\geq d): d > [\!\![ge]\!\!]^{o}\)}

-

a.

If mo in (67) is combined with the at-issue proposition in (66) as in the structure (68), we obtain the scalar presupposition, and the at-issue meaning, as shown in (69):

-

(67)

〚mo〛 = \(\lambda p:~\forall q[C(q) \wedge q \neq p \rightarrow p >_{unlikely} q].~p \)

-

(68)

-

(69)

〚mo(¬(know(Taro)(linguistics) \(\geq [\!\![ge]\!\!]^{o}\)))〛=

∀q[C(q)∧q ≠ ¬(know(Taro)(linguistics) \(\geq [\!\![ge ]\!\!]^{o}\)) →¬(know(Taro)(linguistics) \(\geq [\!\![ge ]\!\!]^{o}\)) \(>_{unlikely} q]. \neg\)(know(Taro)(linguistics) \(\geq [\!\![ge ]\!\!]^{o}\))

The above analysis suggests that the non-literal mora-based minimizer is quite different from the literal one, in that it involves a special type of degree modifier. It takes a gradable predicate and not only supplies a degree, but also fills in the first argument of the predicate.

One potential problem is that, as one reviewer pointed out, the mora-based minimizer seems to be able to co-occur with another degree modifier, like mattaku ‘at all’:

-

(70)

How can we analyze this kind of example? If we assume that mattaku is a degree modifier that combines with a gradable predicate, it is not clear how the two kinds of scalar modifiers interact with the gradable predicate (here shit-teiru ‘know’).

It seems that the sentence of mora-based minimizer with mattaku ‘at all’ is semantically the same as one of mora-based minimizer without mattaku ‘at all’. There seems to be no interaction between the initial mora-based minimizer and mattaku ‘at all’:

-

(71)

Intuitively, the speaker is paraphrasing the mora-based minimizer with mattaku ‘at all’. It may be theoretically possible to consider that there is some kind of concord between the mora-based minimizer and mattaku ‘at all’. This is simply an observation, and I would like to leave the analysis of these examples for future study.Footnote 21

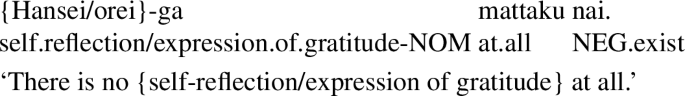

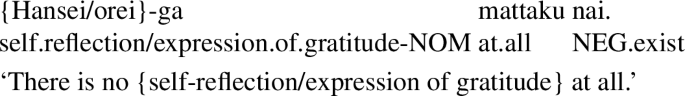

5.2 Example with an eventive noun and a predicative nai ‘lit. do not exist’

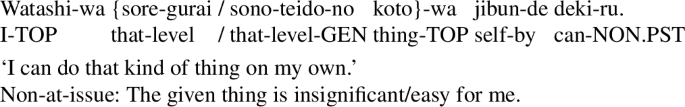

We now analyze an example with an eventive noun and the predicative nai ‘do not exist’:

-

(72)

Similar to the other cases, the predicate nai behaves as a gradable predicate, and posits a degree of existence. This idea is supported by the fact that adverbs of various degrees, such as mattaku, can co-occur with the predicative nai (Sawada 2008):

-

(73)

Note that the degree phenomenon of (non)-existential sentences is quite common in Japanese. For example, the following unmodified non-existence sentence is also assumed to have a degree meaning:

-

(74)

The sentence (74a) does not (usually) mean ‘I now have a non-zero amount of money.’ Instead, it usually means that ‘the actual amount of money is greater than a contextually determined standard.’ The sentence (74b) does not usually mean ‘I now have zero amount of money.’ Instead, it usually means that ‘the actual amount of money is less than a contextually determined standard’.

What is at issue here is the negative nai. Regarding the predicative nai in (74b), I assume that nai is a gradable adjective which means that “it is not the case that x’s existence reaches at least d”:

-

(75)

〚nai〛 = λdλx.¬(exist(x)≥d)

(where \(\mu _{exist}\) measures the quantity of entity/concept)

The fact that the predicative nai is gradable is supported by the fact that it can be modified by various degree adverbs, such as amari ‘all that’ and mattaku ‘at all’:

-

(76)

I assume that in the case of a simple unmodified sentence, it is possible to assume that the unmodified nai (of type 〈d,〈e,t〉〉) combines with a ‘null degree morpheme’ pos, whose function is to relate the degree argument of the gradable predicate to an appropriate standard of comparison (Cresswell 1977; von Stechow 1984; Kennedy and McNally 2005, among others). (77) shows the semantic derivation for the sentence (74b)(STAND\(_{(c)(DIM.G)}\) stands for a contextually determined standard in the dimension associated with G):

-

(77)

In this case, the dimension associated with nai is the dimension of existence. The exact nature of the contextually determined standard needs to be more precise (i.e., it may be a contextual standard for a specific purpose or it may correspond to the average of the members of a comparison class (see, e.g., Kennedy 2007; Kagan and Alexeyenko 2011; Solt 2012), but the semantics of (77) appropriately captures the meaning of (74b), that the existence (quantity) of money is less than a contextually determined standard.

How can we analyze the eventive nai in (72)? For the eventive nai, I assume the following lexical entry (v is a type for an event, and e is a variable for the type v):

-

(78)

\([\!\![\text{nai}_{PRED}]\!\!]\): 〈d,〈v,t〉〉 = λdλe.¬ (exist(e) ≥ d)

(where \(\mu _{exist}\) measures the degree of event (thought-related))

In prose, the eventive nai means it is not the case that e’s existence reaches at least d. Note that in the case of the eventive nai in (72) it is measuring the degree of event that is related to thought.

As for the meaning of hansei ‘self-reflection’, I assume that it denotes an event of type v:

-

(79)

〈 [ha.n.se.i]; NP; self-reflection: v 〉

This suggests there is a slightly different lexical item of a non-literal mora-based minimizer for an event type, as shown in (80):

-

(80)

(Syntactic frame of non-literal initial-mora-based minimizer)

The following shows the meaning of “ha.n.se.i”-no [“ha”]-no ji\(_{non.lit}\):

-

(81)

-

a.

〚“ha.n.se.i”-no [“ha”]-no ji\(_{non.lit}\)\(]\!\!]^{o}\) = \(\lambda P_{\langle d, \langle v, t\rangle \rangle }. P([\!\![ha]\!\!]^{o})(\text{self-} \text{reflection})\)

-

b.

〚“ha.n.se.i”-no [“ha”]-no ji\(_{non.lit}\)\(]\!\!]^{f}\) = {\(\lambda P_{\langle d, \langle v, t\rangle \rangle }. P(d)(\text{self-reflection}): d > [\!\![ha ]\!\!]^{o}\)}

-

a.

If nai is combines with the at-issue and its alternatives, we obtain the following:

-

(82)

〚“ha.n.se.i”-no [“ha”]-no ji\(_{non.lit}\)〛(〚nai〛) =

-

a.

At-issue: ¬(exist(self-reflection) \(\geq [\!\![ha]\!\!]^{o})\)

-

b.

Alternatives: {¬(exist(self-reflection) ≥d)\(: d > [\!\![ha ]\!\!]^{o}\)}

-

a.

At the end of derivation, the scalar particle mo is combined with an at-issue proposition:

-

(83)

Logical structure

5.3 The non-literal minimizer can target a speech act

Interestingly, the non-literal mora-based minimizer can also target a speech act that consists of one word (not just an individual/event-denoting noun):Footnote 22

-

(84)

In this paper, I assume that the speech act targeted by the mora-based minimizer is nominalized. For example, I assume gomennasai ‘I am sorry’ when it is used in an initial mora-based minimizer is syntactically an NP (nominal). This is because it combines with the genitive marker no, which can only combine with a noun. The utterance gomensanasai is a speech act (more specifically an expressive), but when it is used in the frame of initial mora-based minimizer, it becomes nominalized. In (84a), the expressive ‘I am sorry’ is not a genuine speech act, because it is not performed. In fact, the sentence means that there is no apology at all. This means that the nominalized speech act is a part of meaning. Semantically, I treat the nominalized speech act as an individual:

-

(85)

(Nominalized speech act)

〈 [go.me.n.na.sa.i]; NP; I am sorry: e 〉

Note that any speech act expression that combines with the initial mora-based minimizer should be a short, fixed expression, without any additional elements, such as a modifier. For example, if the intensifier hontooni ‘really’ is combined with gomennasai ‘I am sorry’, then the sentence becomes ill-formed even if we neglect the intensifier part and focus on the initial mora of “gomennasai“ as in (86b)Footnote 23:

-

(86)

This differs from the usual non-literal initial mora-based minimizer, which allows modifiers to be added before the object (see Sect. 5.1). In this paper, I assume that there is no slot X for a modifier in the syntactic frame of the (non-literal) initial mora-based minimizer with nominalizing speech acts (presumably because the speech act must be a canonical one-word expression):

-

(87)

(Syntactic frame of speech act-oriented initial-mora-based minimizer)(non-literal)

In this view, we can analyze the meaning of “go.me.n.na.sa.i-no go-no ji” as follows:

-

(88)

-

a.

〚“go.me.n.na.sa.i”-no [“go”]-no ji\(_{non.lit}\)\(]\!\!]^{o}\) = \(\lambda P. P([\!\![go]\!\!]^{o})\)(“I-am-sorry”)

-

b.

〚“go.me.n.na.sa.i”-no [“go”]-no ji\(_{non.lit}\)\(]\!\!]^{f}\) = {λP.P(d)(“I-am-sorry”)\(: d > [\!\![go]\!\!]^{o}\)}

-

a.

For example, the meaning of “go.me.n.na.sa.i-no go-no ji” in (84a) can be represented as follows:

-

(89)

-

a.

〚“go.me.n.na.sa.i”-no [“go”]-no ji\(_{non.lit}\)\(]\!\!]^{o}\) = \(\lambda P. P([\!\![go]\!\!]^{o})\)(“I-am-sorry”)

-

b.

〚“go.me.n.na.sa.i”-no [“go”]-no ji\(_{non.lit}\)\(]\!\!]^{f}\) = {λP.P(d)(“I-am-sorry”)\(: d > [\!\![go]\!\!]^{o}\)}

-

a.

I posit the following lexical item for nai, in a sentence with a nominalized speech act:

-

(90)

〚nai\(_{PRED}\)〛: 〈d,〈e,t〉〉 = λdλx.¬(exist(x) ≥ d)

(where \(\mu _{exist}\) measures the degree of information/thought)

If nai is combined with the at-issue and its alternatives, we obtain the following:

-

(91)

〚“go.me.n.na.sa.i”-no [“go”]-no ji\(_{non.lit}]\!\!]\) (〚nai〛) =

At-issue: ¬(exist(“I-am-sorry”) \(\geq [\!\![go]\!\!]^{o}\))

Alternatives: {¬(exist(“I-am-sorry”) ≥ d) \(: d > [\!\![go]\!\!]^{o}\)}

In the final part of the derivation, mo is combined with the at-issue proposition, and we obtain the following presuppositional and at-issue meanings:

-

(92)

〚mo(¬(exist(“I-am-sorry”) \(\geq [\!\![go]\!\!]^{o}))]\!\!]\) =

∀q[C(q)∧q ≠ ¬(exist(“I-am-sorry”) \(\geq [\!\![go]\!\!]^{o}\)) →¬(exist(“I-am-sorry”) \(\geq [\!\![go]\!\!]^{o})>_{unlikely} q]. \neg\)(exist(“I-am-sorry”) \(\geq [\!\![go]\!\!]^{o}\))

5.4 Explaining the odd examples: the difference from ordinary emphatic NPIs

In this section, I discuss cases in which the non-literal mora-based minimizer is unnatural and elaborate on its differences from normal minimizers.

Unlike ordinary minimizers such as a “1-classifier” phrase plus mo, the mora-based minimizer cannot co-occur with verbs such as tabe-ru ‘eat’, nomu-ru ‘drink’, and i-ru ‘be’:

-

(93)

-

(94)

-

(95)

The oddness of (93a), (94a), and (95a) can be explained based on the semantics of the non-literal mora-based minimizer. These sentences violate the requirement that the measure function of P measures the degree of knowledge, information, concept, thought, or habituality.Footnote 24

For example, the predicate tabe-ru ‘eat’ denotes that x’s amount of food consumption of y reaches at least d and it does not fit the frame of the non-literal initial-mora-based minimizer:

-

(96)

〚tabe-ru〛: 〈d,〈e,〈e,t〉〉〉 = λdλxλy. eat(y)(x) ≥ d

(where \(\mu _{eat}\) measures the amount of food consumption)

We can say that the predicate “know” fits the initial mora-based minimizer frame, but the predicate “eat” does not.

Note that if we replace the verbs tabe-ru ‘eat’, nom-u ‘drink’, and i-ru ‘be’ in (93a), (94a), and (95a) with wadai-ni na-ru ‘become the subject’, then sentences with the mora-based minimizer become natural:

-

(97)

6 The initial mora-based minimizer as PPI

Thus far, we have discussed the mora-based minimizer behaving as an NPI. However, sometimes, the mora-based minimizer also behaves as a PPI:

-

(98)

(Non-literal initial mora-based minimizer, PPI)

A feature of the PPI mora-based minimizer is that it co-occurs with contrastive wa, rather than mo ‘even’. Intuitively, if we use contrastive wa, the phrase is used in affirmative sentences and behaves like English at least. Theoretically, this means that at least in the case of the initial mora-based minimizer, an alternative feature can be checked by focus operators other than EVEN.Footnote 25 Following Sawada (2007), I assume that there are two types of contrastive wa—scalar and non-scalar—and the contrastive wa that combines with the mora-based minimizer is scalar.Footnote 26

Sawada (2007, 2022) argues that scalar contrastive wa has a low scalar value, which is a mirror image of the scalar value of even/mo. More specifically, Sawada (2007, 2022) proposes that it introduces a set of alternative propositions and assumes that (i) there are some alternative propositions q such that q are (possibly) not the case, and (ii) p is the least unlikely (most likely) among the relevant alternatives (“wa stands for the scalar type of contrastive wa) (“wa stands for a scalar type of contrastive wa):

-

(99)

\([\!\![\text{wa}_{CTscalar}]\!\!]\) = \(\lambda p: \exists q[C(q) \wedge q \neq p \wedge (\diamondsuit )\neg q] \wedge \forall q[C(q) \wedge q \neq p \rightarrow q >_{unlikely} p]. p\)

This contrasts with the scalar particle mo, which construes the at-issue proposition p to be the most unlikely among the relevant alternatives.Footnote 27

-

(100)

\([\!\![\text{mo}_{scalar}]\!\!]\) = \(\lambda p: \exists q[C(q) \wedge q \neq p \wedge q] \wedge \forall q[C(q) \wedge q \neq p \rightarrow p >_{unlikely} q]. p\)

Next, we consider the semantic derivation of sentences with a PPI mora-based minimizer using the following sentence as an example:

-

(101)

(Non-literal)

In this approach, PPI and NPI mora-based minimizers share the same meaning, with their interpretive difference lying in the difference of meaning between scalar contrastive wa and mo ‘even’.

-

(102)

(Syntactic frame of the non-literal initial mora-based minimizer)

The at-issue meaning and its alternatives of ge.n.go.ga.ku-no ge-no ji are shown in (103), which is exactly the same for the case where it is used in the context of a minimizer NPI (cf. (64)):

-

(103)

-

a.

〚“ge.n.go.ga.ku”-no [“ge”]-no ji\(_{non.lit}\)\(]\!\!]^{o}\) = \(\lambda P \lambda x. P([\!\![ge]\!\!]^{o})(\text{linguistics})(x)\)

-

b.

〚“ge.n.go.ga.ku”-no [“ge”]-no ji\(_{non.lit}\)\(]\!\!]^{f}\) = {\(\lambda P \lambda x. P(d)(\text{linguistics})(x): d > [\!\![ge]\!\!]^{o}\}\)

-

a.

Ge.n.go.ga.ku-no ge-no-ji is then combined with gurai ‘level’. Here, we assume that gurai ‘level’ does not semantically contribute to the interpretation; rather, it is optional.Footnote 28

Combining the ordinary semantic value and the focus semantic value of gengogaku-no ge-no ji with the verb shit-teiru in (104) and the other at-issue meaning elements in a point-wise manner, an at-issue proposition and its alternatives are obtained, as given below:

-

(104)

〚shit-teiru〛: 〈d,〈e,〈e,t〉〉〉 = λdλxλy.know(y)(x) ≥ d

(where \(\mu _{know}\) measures the degree of knowledge)

-

(105)

-

a.

At-issue meaning: know(Taro)(linguistics) ≥ \([\!\![ge]\!\!]^{o}\)

-

b.

Propositional alternatives: {know(Taro)(linguistics) \(\geq d: d > [\!\![ge ]\!\!]^{o}\)}

-

a.

Finally, the at-issue proposition is combined with the scalar contrastive wa. Similar to mo, there is a mismatch between the surface and logical structures:

-

(106)

The scalar contrastive wa is combined with the at-issue proposition to yield the following at-issue meaning and presupposition:

-

(107)

\([\!\![\text{wa}_{CTscalar}\)(know(Taro)(linguistics) ≥ \([\!\![ge]\!\!]^{o}) ]\!\!]=\)

Presupposition: ∃q[C(q)∧q≠ know(Taro)(linguistics) ≥ \([\!\![ge]\!\!]^{o}\) ∧(♢)¬q]∧∀q[C(q)∧q≠ know(Taro)(linguistics) \(\geq [\!\![ge]\!\!]^{o}\) \(\rightarrow q >_{unlikely}\) know(Taro)(linguistics) \(\geq [\!\![ge]\!\!]^{o}\)]

At-issue: know(Taro)(linguistics) \(\geq[\!\![ge]\!\!]^{o}\)

The scalar component conveys that “the degree to which Taro knows linguistics is greater than or equal to the minimum degree” and the least unlikely (i.e., the most likely) among the alternatives. The polarity component conveys that the stronger alternatives are possibly not the case. As a result, we can infer that Taro knows a minimum amount about linguistics, but does not (potentially) know more than that.

In this approach, the polarity sensitivity of the mora-based minimizer can be explained based on its compatibility with the presupposition of scalar particles. If the contrastive wa is used in a negative sentence, it sounds strange as a result of the incompatibility of the at-issue meaning and its presupposition:

-

(108)

(Non-literal)

Here, a presupposition that “I do not know the bare minimum of linguistics” is construed as the least unlikely (i.e., most likely) of alternatives, which contradicts our intuition. On the other hand, if mo is used instead of kurai-wa, this sentence becomes a natural sentence (see (62)), because in this case, the proposition that I do not know the bare minimum of linguistics is construed as the most unlikely among the alternatives.

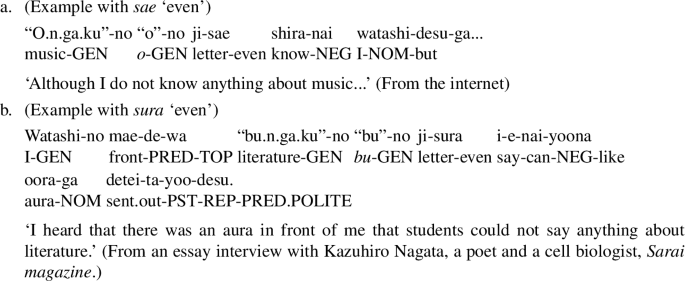

7 Mora/syllable-based minimizers in other languages and related phenomena

Thus far, we have considered the phenomenon of the Japanese mora-based minimizer. In this section, I briefly consider mora-based minimizers from a cross-linguistic perspective and show that a similar phenomenon can also be found in Korean and Bosnian/Croatian/Serbian. We also observe related phenomena concerned with “letter” (such as English ABC(s) and Japanese iroha) and discuss their differences from mora-based minimizers.

7.1 Similar phenomena in Korean and Bosnian/Croatian/Serbian

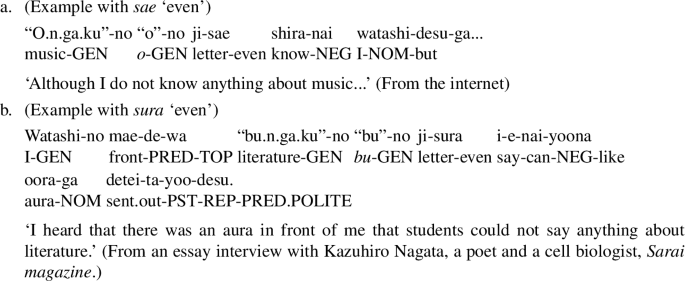

As evident from the following examples, Korean has a phenomenon similar to the Japanese mora-based minimizer:Footnote 29

-

(109)

Note that it is possible to paraphrase (109b) as (110) using “kiyek”:

-

(110)

In Hangul, the letter “k” is named or referred to as “kiyek.”Footnote 30

Wayles Browne (p.c.) commented that in Bosnian/Croatian/Serbian there is a very similar phenomenon to the Japanese mora-based minimizer (or something very similar to this minimizer). The following examples are from the books/articles written by Midhat Ridjanovic (Wayles Browne p.c.):

-

(111)

As can be seen in the above examples, Bosnian/Croatian/Serbian seem to target initial consonants rather than initial moras, and are not dependent on the exact same rules at the phonetic level as the Japanese mora-based minimizer. However, they seem to have very similar meanings and functions to the Japanese mora-based minimizer. Perhaps they could be called consonant-based minimizers.

7.2 Related but different phenomena: Iroha and ABCs

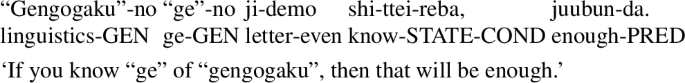

Let us now consider some related but different phenomena in Japanese and English. First, we consider the non-literal use of Japanese iroha. As discussed in this paper, iroha represents the first three characters of the old hiragana order, or the hiragana system itself, but it also has the non-literal meaning of ‘the basics/the rudiments’, as shown in:

-

(112)

When iroha appears in a negative sentence with the scalar particle mo, it functions as a nonliteral mora-based minimizer. We can paraphrase the sentences of the non-literal mora-based minimizer using iroha in NP-no iroha ‘the basics/rudiments of an NP’:

-

(113)

However, NP-no iroha is more restricted than the non-literal mora-based minimizer, in that it can only be used in contexts where the scale of mastery/skill is relevant. For example, (114b) sounds odd because of the mismatch between the meaning of the verb and that of iroha:

-

(114)

As NP-no iroha posits a scale/dimension of “mastery/level”, it can be assumed to constitute a non-compositional (lexically specified) minimizer whose scale is lexically fixed. In contrast, the non-literal mora-based minimizer can be viewed as a compositional minimizer whose scales are specified via the information of scalarity, in the predicate with which the minimizer co-occurs.

Note that iroha can combine with the mora-based minimizer as well:

-

(115)

Iroha in iroha-no i-no ji means ‘basics/rudiments’ and the sentence means “you do not understand even the minimum level of basic management”. It is possible to express a similar meaning by simply using iroha ‘rudiments/basics’, as shown below, but with a slightly different meaning:

-

(116)

The former (=(115)) means that you don’t even have minimum knowledge about the basics of management, whereas the latter (=(116)) means that you don’t even know the rudiments of management.

Interestingly, in English the ABC(s) can also mean “the basics,” and suggests a scale of degrees of mastery:

-

(117)

-

a.

But clearly, she doesn’t even know the ABCs of her job.

(From the internet)

-

b.

It’s almost like they don’t even know the ABC of security.

(From the internet)

-

a.

The English phrase, the ABC(s) is similar to the Japanese non-literal iroha, in that it lexically posits a scale of mastery. However, it differs from mora-based minimization in that the scale is highly fixed.Footnote 31

8 Conclusions

This study investigated the meanings and interpretations of the Japanese initial mora-based minimizer of the form “X.Y...”-no “X”-no ji ‘even the letter “X” of “X.Y...”, and considered the difference between the literal reading and the non-literal reading of the initial mora-based minimizer, the development and compositional mechanism of the literal minimizer, and the difference compared to typical minimizers.

I showed that while the literal initial mora-based minimizer posits a scale on the number of morae and construes the first mora X to be a minimum on the scale, the non-literal minimizer posits a scale concerning a degree associated with the main predicate. In other words, for the non-literal minimizer, X corresponds to the minimum degree with respect to the target “X.Y...” on a scale associated with P.

Based on the BCCWJ corpus, I showed that although the initial mora-based minimizer is highly productive, it tends to co-occur with predicates that relate to information, knowledge, or concepts. I argued that this restriction is due to the conventionalization of a pragmatic inference arising from a literal reading related to letters.

With respect to compositionality, I extended Chierchia’s (2013) NPI/minimizers approach (in which each NPI/minimizer is assumed to have a lexical requirement for the type of alternatives) (i.e., strictly scalar alternatives/domain alternatives), and argued that each mora-based minimizer has broader lexical constraints on the relationship between sound (phonology) and degree (meaning), based on the syntactic frame. For the non-literal minimizer, I claimed that it has various constraints on form and meaning (concerned with modification structure, concept, and the relationship between degree and predicate) as syncategorematic rules. I showed that these constraints properly capture the meaning and distribution patterns of the non-literal initial mora-based minimizer.

It is theoretically important that the initial mora-based minimizer is highly productive, and the scalar meaning is derived by interaction with the main predicate information. The phenomenon of the non-literal initial mora-based minimizer suggests that there is a compositional (lexically unspecified) minimizer in natural language whose scale is specified via the information of scalarity in the predicate with which the minimizer co-occurs. This is in addition to a non-compositional (lexically-specified) minimizer that posits a lexically determined scale (Chierchia 2013).

Since Bolinger (1972), many important studies have been conducted on the meanings and distributions of minimizer NPIs, based on examples such as English a word, budge an inch, and lift a finger and the Japanese 1-classifier-mo) (e.g., Ladusaw 1980; Heim 1984; Krifka 1995; Giannakidou 1998; Lahiri 1998; Nakanishi 2006; Chierchia 2013; Csipak et al. 2013; Tubau 2020, among many others). However, these minimizers are “non-compositional (lexically specified)” minimizers, in that their scalarity is lexically fixed. The initial mora-based minimizer can be considered idiomatic in the sense that it has abstract constraints inside the syntactic frame. However, its scalar meaning is not lexically specified and is derived compositionally.

The phenomenon of the non-literal mora-based minimizer also provides a new perspective on variations of minimizers in terms of interface. This paper considered that the initial mora-based minimizer has broader lexical constraints on the interface between sound and degree.

The final part of this study examined similar phenomena in other languages and showed that the mora (syllable)-based minimizers are also pervasive in natural language, based on data from Bosnian/Croatian/Serbian and Korean, thereby suggesting a new typology of minimizers. More empirical and theoretical investigations will be necessary regarding the variation of mora-based minimizers and related phenomenon.

Abbreviations: The following abbreviations are used for example glosses: ACC: accusative, BEN: benefactive, CL: classifier, COMP: complementizer, COND: conditional, CONT: contrastive, DAT: dative, GEN: genitive, LOC: locative, MIR: mirative; NEG: negation, negative, NMLZ: nominalizer, NOM: nominative, NON.PST: non-past tense, PASS: passive, PL: plural, POLITE: polite, PRED: predicative, PRES: present, PRF: perfective, Prt: particle, PST: past, REP: reported/reportative, STATE: state/stative, TE: Japanese te-form, TEIRU: Japanese teiru (effectual) form, TOP: topic.

Notes

In principle, (4a) can also be read literally. However, I think that the literal reading is not salient in this example. If we attempt to interpret the sentence literally, it will convey that “ge” is the most likely letter known, but it does not seem natural from a pragmatic point of view.

Regarding (12), i, ro, and ha are the first three letters of the old-style Japanese hiragana order (appearing at the beginning of a poem). However, iroha can also mean “hiragana system in general” as a generic term. If iroha is understood as the entire hiragana system, then the sentence can be interpreted non-literally to mean: ‘Taro cannot write hiragana system at all’.

English minimizers like lift a finger can appear in various non-negative environments, including antecedents of conditionals or questions. In addition, English minimizers are appropriate in the environment of only and emotive factive verbs (see, e.g., Giannakidou 2011 for an overview of previous studies).

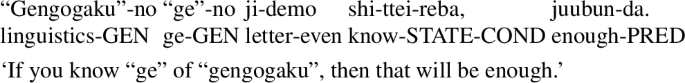

As one reviewer pointed out, if we use demo ‘approx. even’ instead of mo ‘even’, the mora-based minimizer can appear in a conditional clause, even without negation:

-

(i)

In the literature, it is observed that the distribution of “1-classifier-demo” is different from that of “1-classifier-mo” (Nakanishi 2006; Yoshimura 2007), in that the former cannot appear in a pure negative sentence and usually appears in other downward-entailing/non-veridical contexts such as a conditional, imperative, or question:

-

(ii)