Abstract

This study investigates the meanings of the Japanese low-degree modifiers kasukani ‘faintly’ and honokani ‘approx. faintly’ and the English low-degree modifier faintly. I argue that, unlike typical low-degree modifiers such as sukoshi ‘a bit’ in Japanese and a bit in English, they are sense-based in that they not only semantically denote a small degree but also convey that the judge (typically the speaker) measures the degree of predicates based on their own sense (the senses of sight, smell, taste, etc.) at the level of conventional implicature (CI) (e.g., Grice (in: Cole, Morgan (Eds.), Syntax and semantics iii: speech acts, Academic Press, New York, 1975), Potts (The logic of conventional implicatures, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2005), McCready (Semant Pragmat 3:1–57, 2010. https://doi.org/10.3765/sp.3.8, Sawada (Pragmatic aspects of scalar modifiers. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Chicago, 2010), Gutzmann (Empir Issues Syntax Semant 8:123–141, 2011)). I will also show that there are variations among the sense-based low-degree modifiers with regard to (i) the kind of sense, (ii) the presence/absence of positive evaluativity, and (iii) the possibility of direct measurement of emotion and will explain the variations in relation to the CI component. A unique feature of sense-based low-degree modifiers is that they can indirectly measure the degree of non-sense-based predicates (e.g., emotion) through sense (e.g., perception). I show that the proposed analysis can also explain the indirect measurement in a unified way. This paper shows that like predicates of personal taste such as tasty (e.g., Pearson (J Semant 30(1):103–154, 2013. https://doi.org/10.1093/jos/ffs001), Ninan (Proc Semant Linguist Theory, 24:290–304, 2014. https://doi.org/10.3765/salt.v24i0.2413), Willer & Kennedy (Inquiry, 1–37, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1080/0020174X.2020.1850338)), sense-based low-degree modifiers trigger acquaintance inference. The difference between them is that, unlike predicates of personal taste, sense-based low-degree modifiers co-occur with gradable predicates and their experiential components signal the manner/way in which the degree of the predicate in question is measured.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

In recent years, the concept of experience/acquaintance has received increasing attention in the field of formal semantics, especially since the semantic study of predicates of personal taste. For example, predicates of personal taste such as tasty or fun differ from ordinary adjectives such as tall and deep in that the former elicits ‘acquaintance inference’: the utterance of simple sentences containing predicates of personal taste (such as tasty and fun) typically suggests that the speaker has first-hand knowledge of the item being evaluated as they have directly experienced it (e.g., MacFarlane, 2014; Ninan, 2014; Pearson, 2013; Willer & Kennedy, 2020; Kennedy &Willer, 2022). For example, the following sentence containing the adjective delicious draws the inference that the speaker has actually drunk matcha tea:

If the speaker does not have direct experience and only has indirect evidence (e.g., popularity of matcha), the speaker should use a modal (e.g., Matcha tea must be delicious).

By contrast, as many researchers have observed, this type of acquaintance inference does not arise obligatorily from sentences with ordinary adjectives. For example, from the following sentence with the adjective deep, we do not obligatorily receive the inference that the speaker has experienced the depth of Suruga Bay:

Here, sentence (2) is natural even if the speaker actually experienced (perhaps with special equipment) the depth of Suruga Bay.Footnote 1 However, such experience is not required, and the speaker can also utter this sentence based on some indirect evidence (e.g., information on a map).

In this paper, I will pursue the idea that this kind of distinction by the necessity of experience is also seen in low-degree adverbs. While there are various types of low-degree modifiers in Japanese and English, they can be broadly classified into two: Class 1 low-degree modifiers and Class 2 low-degree modifiers. For example, it seems that the English adverbs a bit, a little, and slightly and the Japanese adverbs sukoshi and chotto can be classified as Class 1 low-degree modifiers, while the English adverb faintly or the Japanese adverbs kasukani ‘faintly’ and honokani ‘approx. faintly’ can be classified as Class 2 low-degree modifiers:

Both Class 1 and Class 2 low-degree modifiers semantically represent a low degree. However, their distribution patterns are not the same.Footnote 2 Similar to Class 1 low-degree modifiers, Class 2 low-degree modifiers such as faintly, kasukani, and honokani can co-occur with gradable predicates such as sweet/amai ’sweet’ and bright/akarui ’bright’:

However, unlike Class 1 low-degree modifiers, Class 2 low-degree modifiers such as faintly, kasukani, and honokani cannot co-occur with gradable predicates such as takai ‘expensive’:Footnote 3

Since Bolinger (1972), many studies have investigated the meaning and distributions of degree modifiers (positive polarity minimizers) (e.g., Horn, 1989; Kennedy, 2007; Sawada, 2010; Kagan & Alexeyenko, 2011; Bylinina, 2012; Sassoon, 2012; Solt, 2012). However, these studies are concerned with Class 1 low-degree modifiers; to the best of my knowledge, no study has focused on Class 2 low-degree modifiers.

What are the differences between Class 1 and Class 2 low-degree modifiers? How can we explain the limited distribution of Class 2 low-degree modifiers? How does the distinction between Class 1 and Class 2 low-degree modifiers relate to the difference between predicates of personal taste and regular gradable predicates?

This study investigates the meanings and distribution patterns of Class 2 low-degree modifiers such as kasukani/honokani in Japanese and faintly in English to show that, unlike Class 1 low-degree modifiers, Class 2 low-degree modifiers are sense-based and need to co-occur with a sense-related expression to satisfy the requirement that they be sensory measurements.

After reviewing the basic semantic properties of Class 1 low-degree modifiers in Sect. 2, in Sect. 3 I will focus on the meaning and use of kasukani and claim that, unlike ordinary low-degree modifiers (Class 1), it requires that a judge (typically a speaker) measures the degree of the gradable predicate in question based on their own senses (e.g., the senses of sight, smell, and taste). More theoretically, the analysis in Sect. 4 and 5 shows that kasukani is mixed content (McCready, 2010; Gutzmann, 2011) in that it not only denotes a low scalar meaning in the at-issue component, but also implies that the judge (typically the speaker) has measured the degree based on their own senses (e.g., sight, smell, taste, and hearing) at the level of conventional implicature (CI) (e.g., Grice, 1975; Potts, 2005; McCready, 2010; Sawada, 2010, 2018; Gutzmann, 2011, 2012). Thus, I show that the experiential components of sense-based low-degree modifiers restrict the environments in which they can be used.

This means that sense-based low-degree modifiers trigger acquaintance inference similar to the predicate of personal taste such as fun or tasty. However, as we will discuss in detail in Sect. 4, sense-based low-degree modifiers have several different aspects from the usual predicate of personal taste. First, in terms of compositionality, sense-based low-degree modifiers belong to a new kind of acquaintance inference-triggering expression in that it can turn a neutral predicate into a predicate of personal taste. For example, akarui ‘bright’ is a sense-related adjective in that it has to do with light, but the expression itself does not obligatorily trigger an acquaintance inference. For example, we can say Kinsei-wa akarui ‘Venus is bright’ without actually looking/having looked at Venus. We can acquire the fact from a science book. However, if kasukani is combined with akarui ‘bright’ (i.e., kasukani akarui ‘faintly bright’), then it obligatorily triggers an acquaintance inference regarding the level of brightness.

Second, sense-based low-degree modifiers and predicates of personal taste have different properties in terms of projection. Previous studies of predicate of personal taste have reported that the experiential meaning of predicate of personal taste disappears in conditional, interrogative, and modality environments (e.g., Pearson, 2013; Ninan, 2014; Willer & Kennedy, 2020). However, in the case of sense-based low-degree modifiers, their experiential meaning is strongly projected even if they are embedded in these environments, and as a result, the resulting sentences often become odd because the acquaintance inference is not justified.Footnote 4 I will suggest that this strong projective property is due to sense-based low degree modifier’s function that they signal the ‘manner’ of measurement, and the experience is an immediate direct sensory experience.

Although Class 2 sense-based low-degree modifiers (kasukani, honokani, and faintly) are all related to sense, their meanings and distribution patterns are not the same. As shown in Sect. 6, honokani is more restricted than kasukani (and faintly), and I claim that honokani only allows a judge to measure the degree based on their sense of “brightness”, “perfume”, or “sweetness”. It also has a positive evaluative meaning toward the degree. By contrast, English faintly has a broader distribution pattern than kasukani (and honokani). Based on corpus data (the British National Corpus (BNC) and the Corpus of Contemporary American English (COCA)) and examples in dictionaries and on the Internet, I will observe in Sect. 7 that, unlike kasukani/honokani, faintly can directly combine with not only sense-related gradable predicates such as sweet and visible, but also emotive predicates:

I will explain these points by assuming that each sense-based low-degree modifier has a different selectional restriction in the non-at-issue domain.

An important feature of the sense-based measurement is that there is a case of indirect measurement. For example, although kasukani cannot directly combine with an emotive predicate as in (9a), it can combine with an emotive predicate if there is a sense-related expression such as mie-ru ‘look’ at a structurally higher level as shown in (9b):

In (9b), kasukani is syntactically/semantically modifying an emotive predicate and denoting that the degree of surprise is slightly greater than zero, but the measurement is done through the speaker’s perception (sense of sight). Section 8 investigates the mechanism of this kind of “indirect measurement” based on the data of kasukani and faintly, showing that the proposed CI-based analysis can also successfully explain its mechanism.

This study shows that, like a predicate of personal taste such as tasty (e.g., Pearson, 2013; Ninan, 2014; Willer & Kennedy, 2020), a sense-based low-degree modifier triggers the acquaintance inference. The difference between them is that, unlike a predicate of personal taste, a sense-based low-degree modifier co-occurs with a predicate and its experiential component signals the manner/way of measurement concerning the predicate (i.e., immediate sensory experience). I will argue that the experiential component of sense-based low-degree modifiers is satisfied via their interaction with other (sensory-related) elements in the sentence, suggesting that it is a kind of concord phenomenon.

2 Meanings of typical (Class 1) low-degree modifiers

Before looking at the meaning and distribution patterns of sense-based low-degree modifiers (Class 2), let us first consider the meaning of a typical low-degree modifier and the environment in which it occurs as a starting point for discussion. This section will particularly focus on the following low-degree modifiers: a bit, a little, and slightly in English and sukoshi and chotto in Japanese.

2.1 English typical (Class 1) low-degree modifiers

Kennedy (2007) argues that slightly is sensitive to the scale structures of gradable adjectives and serves as a diagnostic for distinguishing relative adjectives and lower-closed absolute gradable predicates. As the following examples show, slightly can naturally combine with an absolute gradable adjective that inherently has a minimum standard (\({\text {S}_{min}}\)) (lower-closed scale), but it cannot naturally combine with a relative adjective that posits a norm-related contextually determined standard \(\text {S}_{n}\)(a so-called distributional standard):Footnote 5

Figure (11) graphically shows the scale structure of absolute gradable predicates and Figure (12) shows the scale structure of relative gradable predicates; here, only the former is suitable for the use of slightly:

However, it has been claimed recently that slightly can combine with a relative gradable adjective if the adjective is coerced to have a “functional reading” (Kagan & Alexeyenko, 2011; Solt, 2012; Bylinina, 2012):

In a functional reading, there is a functional standard (\({S_{f}}\)) that corresponds to the maximum degree that is suitable for a given function or purpose, and it is considered similar to the interpretation of an excessive degree (e.g., too long/tall/deep), as shown in:

Solt (2012) and Bylinina (2012) consider that a bit and a little also trigger a functional reading if they are combined with a relative gradable adjective. Solt (2015: 116) also claims that the felicity of relative gradable adjectives under a functional reading suggests that these standards are potentially precise. According to Sassoon (2012), slightly + ADJECTIVE are interpreted in relation to a fine granularity level \({g_p}\). With regard to a standard, Sassoon (2012) also claims that, when slightly is combined with relative adjectives such as tall, it requires an external specific threshold for the standard of measurement.

2.2 The meaning and distribution of Japanese sukoshi/chotto

Let us now turn our attention to Japanese low-degree modifiers. As the following examples show, both chotto and sukoshi can naturally combine with a relative gradable predicate and an absolute gradable predicate:

Notice that as the examples in (16) show that both chotto and sukoshi can have both a functional reading and a norm-related reading (Sawada, 2019). This point is different from the English slightly.Footnote 6

Regarding the difference between sukoshi and chotto, descriptive grammars and dictionaries often mention that chotto is more colloquial or casual than sukoshi (e.g., (Kamiya, 2002). Sawada (2018) claims that sukoshi conventionally implicates that the speaker has measured a degree precisely, while chotto conventionally implicates that the speaker is measuring a degree imprecisely.Footnote 7

While there is a semantic difference between sukoshi and chotto and a difference with respect to pragmatic function, an important thing to note here is that both can co-occur with any predicate of degree and, in particular, with both sensory and non-sensory adjectives. In this respect, they differ significantly from the sense-based low-degree modifier, which will be discussed in detail in this paper.

3 Basic properties of Japanese kasukani ‘faintly’

Let us now start considering the meaning of sense-based low-degree modifiers. In doing so, the meaning and distribution of Japanese kasukani ‘faintly’ will be considered first, which will be a foundation for considering other types of sense-based low-degree modifiers.

3.1 Sensory and experiential properties of kasukani

To the best of my knowledge, there have been no studies on the Japanese kasukani in the field of semantics, but a dictionary search reveals several noteworthy descriptions of the word. For example, Koujien, a well-known Japanese dictionary, has an entry for the nominal adjective kasuka and states that kasuka expresses “the way in which the shape, color, sound, smell, etc. of an object can be slightly recognized.” It also states that kasuka describes “a situation that is difficult to recognize.” The Meikyo Japanese Dictionary defines the meaning of kasuka ‘faint’ as “a state of being barely recognizable by the senses, memory, etc.” and “an extremely feeble appearance.”Footnote 8

Kasukani is an adverb with-ni attached to kasuka ‘faint’. As the following examples show, kasukani can combine with various kinds of expressions that involve senses:

Notice that kasukani can also be used for measuring the degree of memory as in (17f). The degree of memory is not measured based on a physical sense, but I assume that memory is also connected to sense.

Although kasukani is sense-based, typical low-degree modifiers such as sukoshi and chotto are also fine in these examples. Thus, looking at these sentences alone does not clearly distinguish between kasukani and sukoshi/chotto. The contrast arises when we consider sentences with a non-sense-related predicate. Unlike typical low-degree modifiers, kasukani cannot combine with a gradable predicate that has nothing to do with sense:

Intuitively, kasukani is used to indicate that the degree is not zero (although it is close to zero). As such, it does not fit with measurements based on a functional standard or a contextual norm. For example, when I say, as a functional measurement, that a T-shirt is a little big for me, I am not reporting that in relation to zero degree. Moreover, when we measure price as a norm-related reading, we do not measure it in relation to zero degree.

From this point, it seems correct to say that kasukani is sensitive to scale structure. It cannot combine with a relative gradable predicate that posits a “contextual standard”. However, sensitivity of scale structure alone is not enough for the explanation of the use of kasukani. Even if a gradable predicate lexically posits an end (zero) point, kasukani cannot combine with it if it is not sense related. For example, katamui-tei-ru ‘inclined’ and magat-tei-ru ‘bent’ have a lower-closed scale but cannot naturally combine with kasukani:

The examples (19) with kasukani are strange because katamui-tei-ru ‘inclined’ and magat-tei-ru ‘bent’ are not sense related. Note, however, that, if we add mie-ru ‘look’ at the end of the sentences, the sentence with kasukani becomes more natural:

In this sentence, the speaker is measuring the degree of inclination through perception. We will discuss this type of indirect measurement in detail in Sects. 3.3 and 8.

So far, we have observed the examples of kasukani that relate to a specific sense. However, sensory measurement by kasukani does not always need to be specific. Observe the following sentence:

Although the predicate kanji-ru ‘feel’ is concerned with sense, it does not lexically specify sense. Depending on the context/situation, a relevant sense can be sight, smell, touch, etc. Note also that a measurement by multiple senses is also possible when the main predicate is kanji-ru ‘feel’:

Here, the degree of kanji-ru ‘feel’ is measured based on the senses of smell and taste.Footnote 9

Similar to kanji-ru ‘feel’, the verb su-ru ‘lit.do’ also naturally co-occurs with kasukani. The Meikyo Japanese Dictionary mentions that this kind of su-ru means “to be able to feel sound, taste, smell, etc. through the sense organs.”Footnote 10

The examples in (20)–(23) clearly show that kasukani is deeply related to the judge’s (usually the speaker’s) direct experience. It also predicts that if a speaker does not have direct experience of a sense, they cannot use kasukani. As the following examples show, this prediction is borne out:

(24) is natural because the speaker measures the degree of sweetness based on their own sense. In contrast, (25) sounds odd with kasukani because the speaker does not measure the degree of sweetness of coffee based on their own sense.Footnote 11

The above discussions suggest that kasukani is very similar to predicates of personal taste that require direct experience (e.g., Pearson, 2013; Ninan, 2014; Willer & Kennedy, 2020; Kennedy & Willer, 2022), particularly a sense-related predicate of personal taste such as tasty:Footnote 12

For example, Pearson (2013) describes the requirement of direct sensory experience in predicates of personal taste as follows:

In the following sections, we will discuss the similarities and differences between a predicate of personal taste and a sense-based low-degree modifier when they become relevant. One puzzling point is the fact that kasukani cannot naturally co-occur with oishii ‘tasty’:

I will address this issue in Sect. 5 and explain it in terms of the scale structures of kasukani and taste predicates.

3.2 The barely-recognizable component of kasukani

Another important feature of kasukani is that it is used in situations where the speaker is somehow aware of the low degree. According to Nihon Kokugo Daijiten, kasukani represents the degree of a thing, such that it can barely be recognized through the exercise of perception or memory. In other words, kasukani ‘faintly’ not only has a low degree meaning but also denotes that the degree in question is barely recognizable. One might consider that kasukani is semantically similar to bonyari ‘dimly’:

Kasukani and bonyari share the meaning of “barely”. However, they are not semantically the same. Kasukani has a low degree meaning but bonyari does not. Furthermore, unlike kasukani, bonyari can only be used in contexts relevant to visual perception or memory and cannot be used in situations relevant to smell, hearing, or touch:

3.3 Distributions of kasukani: Corpus studies

In the previous sections, we observed that kasukani measures degrees based on the senses. In this section, we confirm the validity of this observation using NINJAL-LWP for BCCWJ. We show that some corpus data may appear to be counterexamples at first glance, but closer observation shows that they are not counterexamples.

In looking at data, we searched for examples in which kasukani and “adjectival form” co-occurs, and found 54 hits. Strictly speaking, there are two patterns of “adjectival forms”: i-form (an adjective) and ku-form (an adverbial form of adjective). After eliminating examples with annotation problems (six examples), two examples from haiku and poetry collections, and cases in which kasukani is linearly adjacent to an adjective but structurally modifies a verb rather than an adjective (two examples), 44 examples remained.

Table 1 lists the adjectival forms that co-occurred with kasukani with a frequency of 2 or more.

The following are some of the examples that appeared in the corpus:

Noteworthy here is the following example in which araku nat-ta ‘became ruffled’ was used. At first glance, this example may seem to be a counterexample, since arakuna-ru ‘become ruffled’ itself has no inherent sensory meaning. However, as can be seen in the entire example, those degrees are weighed through the senses. In other words, in this sentence, the degree of “roughness” is being measured through the sense-related expression yoo-da ‘seem’:

The same can be said for adjectives with a frequency of a frequency of 1 listed in Table 2.

In the following examples, kasukani co-occurs with an adjectival/adverbial expression, which is related to the senses:

The following examples may appear to be counterexamples because gradable predicates are not related to sense, but the meaning of the modified noun phrase indicates that kasukani measures the degree based on sense.

For example, in (34a) marui ‘round’ itself is not related to a sense, but since there is a noun kanji-o ukeru ‘lit. receive a feeling’ in the sentence, we can assume that kasukani is measuring the degree of roundness based on the sense of sight (appearance). Similarly, in (34b), the adjective ii ‘good’ itself is not related to a sense, but the use of the sensory noun kaori ‘perfume’ and the verb suru ‘to experience’ indicates that ‘faint’ measures the degree of goodness based on the sense of smell.

In the following examples in which kasukani ‘faintly’ is embedded in the complement of the verbs kanji-ru ‘feel’ and kizuk-u ‘notice’ in the main clause, the presence of these verbs in the main clause guarantees that kasukani is sensory-based:

The following are cases where it is guaranteed that the degree of the adjective in question is measured through vision by the sense-related suffixes -ge ‘look’ and -soo ‘look’:

Thus, whether kasukani is measuring the degree based on sense must be determined by not only the nature of the adjective (gradable expression) co-occurring with it, but also the presence or absence of sensory nouns, verbs, or modalities used in the sentence. As in the examples in (37), kasukani can measure the degree of emotion through sight; in that case, kasukani is related to sense in an indirect fashion. In this paper, we call such a case of indirectly measuring the degree of a non-sensory adjective through a sense “indirect measurement.” The semantic interpretation mechanism of indirect measurement will be discussed later in Sect. 8.

4 Non-at-issue (CI)/projective properties of kasukani

4.1 Status of the experiential/sensory meaning of kasukani

Let us now consider the status of the meaning of kasukani. I argue that kasukani induces a CI (Grice, 1975; Potts, 2005) that the judge (typically the speaker) measures the degree of which based on their own sense (sight, smell, taste, etc.). More specifically, I assume that kasukani ‘faintly’ is mixed content in that it has an at-issue scalar meaning and the CI (McCready, 2010; Gutzmann, 2011) inside the lexical items:

I consider that sense-based low-degree modifiers belong to a new kind of acquaintance inference-triggering expression in that it can turn a neutral gradable predicate into a predicate of personal taste.Footnote 13

For example, akarui ‘bright’ is an adjective relating to light, but the expression does not obligatorily trigger the inference that the judge is actually measuring the degree of brightness based on the judge’s own sense. This is supported by the fact that the following continuation is natural:

However, if kasukani is combined with akarui ‘bright’, then the whole expression obligatorily triggers an acquaintance (immediate direct experiential) inference. Thus, the continuation in (40) sounds strange:

The following examples with ugok-u ‘move’ also suggest that it is kasukani ‘faintly’ that triggers acquaintance inference:

The motion verb ugoku ‘move’ does not require a speaker’s sensory experience as in (41a). However, when kasukani is combined with the verb, it requires the immediate sensory experience of the judge as in (41b).

Let us now consider the CI-ness of the sensory experiential meaning in detail. In the Gricean pragmatics, CIs are considered a part of the meaning of words, but they are independent of “what is said” (at-issue meaning) (e.g., Grice, 1975; Potts, 2005; McCready, 2010; Gutzmann, 2011; Sawada, 2010, 2018). Furthermore, it is often assumed that CIs are speaker-oriented by default (Potts, 2007).

The experiential component is a CI because it is independent of “what is said” (at-issue meaning). This is supported by a denial test. Let us consider this point in comparison with other semantic components of kasukani. First, as shown in the following example, it is safe to say that the low degree can be deniable:

Furthermore, the following examples suggest that the vague component is also deniable:

However, as shown below, it is impossible to reject the experiential meaning by saying, “No, that’s false”:

This supports that the experiential component is a CI (not at-issue).Footnote 14

Another piece of evidence for the idea that kasukani has a CI and is logically independent of “what is said” comes from the fact that the experiential meaning triggered by kasukani projects even if kasukani is embedded under the verb omou ‘think’ or the modal kamoshirenai ‘may’:

The CI components of (47) are not within the semantic scope of omou ‘think’ or kamoshirenai ‘may’.Footnote 15

One important point to be mentioned is that, although the experiential meaning of kasukani has a projective property, in many cases, the resulting sentences become unnatural when kasukani is embedded under logical operators. Before considering this point, let us first observe the typical examples of projection based on the expressive damm (which is often analyzed as a CI triggering expression):

In the above examples, although damn is syntactically embedded under negation, a modal, a conditional, or a question operator, the negative motive meaning that the speaker has a negative attitude toward Sheila’s dog is projected. (Note that there is a presupposition that Sheila has a dog, which is triggered by the possessive marker and it also projects.)

Now let us consider the case of kasukani. First, the negative sentence with kasukani is ill-formed:

This suggests that kasukani is a positive polarity item (PPI), which cannot appear in a negative environment. The ill-formedness of (49) can be explained from the discrepancy between the experiential nature of kasukani and the at-issue meaning. In other words, while the at-issue meaning in (49) says that there is no slight, barely perceptible sweetness, it also says that the degree of sweetness is measured by the speaker’s sense of taste, creating a discrepancy between the at-issue component and the CI component. Namely, the CI meaning is projected, but since it is not justified, the sentence sounds strange.

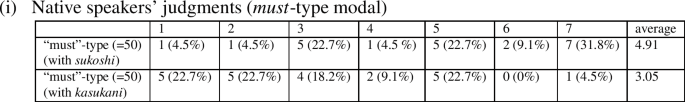

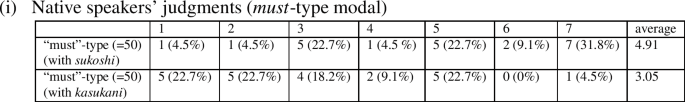

Compared with the case of negation the judgments becomes subtle, but usually it is also odd to use kasukani with the must-type of predicative modal nichigainai ‘must’ as shown in:Footnote 16

In this context the speaker is predicting the degree of bitterness based on indirect evidence. Since the speaker has not tasted the coffee, the CI meaning is not justified and the example is perceived as unnatural.

Similarly, in many cases it is odd to use kasukani in the antecedent of conditionals as shown in:Footnote 17

The sentence with kasukani sounds odd because the speaker has not experienced the degree via their own sense. (From the perspective of the shopkeeper, she/he cannot experience the speaker’s senses.)

This does not mean that kasukani cannot appear in any conditional clause; if the sensory experience is justified, it can appear in a conditional clause:Footnote 18

This sentence is natural because it is clear that the addressee (=the patient) is measuring the volume of sound based on their own auditory perception.Footnote 19

Finally, in the environment of question, usually kasukani does not naturally occur in questions:Footnote 20

In this situation, the person who experiences the degree of bitterness is the hearer. Given that the speaker is asking about the quality of coffee, it does not make sense if the judge is the speaker. However, even if the judge is shifted to the addressee, the sentence still sounds strange if we use kasukani because the addressee-oriented CI is not justified.

However, similar to the case of conditional sentences, kasukani can be used in interrogative sentences if the context is such that sensory experience is guaranteed. In the following sentence, which assumes a context in which a doctor is examining a patient’s hearing, it is natural to use kasukani in question:

Since the experience is justified, the CI of kasukani projects naturally.Footnote 21

We have so far considered the cases wherein the judge is a speaker or an addressee. However, if it is embedded under an attitude predicate and the subject of the sentence is a third person, the judge of kasukani is the subject (i.e., the attitude holder):

Similarly, if kasukani co-occurs with a hearsay evidential such as rashii ‘I hear’, then the judge of kasukani is someone who reported that the wine is faintly sweet, as shown below:

Although Potts (2005) claims that CIs are always speaker-oriented, various scholars have claimed that CI expressions such as expressives can have a non-speaker orientation (e.g., Amaral et al., 2007; Potts, 2007; Harris & Potts, 2009). The above examples suggest that this also applies to kasukani.

One might consider that the non-at-issue (experiential) component is a presupposition. A presupposition is an inference or proposition whose truth is taken for granted in the utterance of a sentence. Furthermore, presupposition is seen as knowledge shared between the speaker and the hearer. The presupposition-based account of kasukani will be similar to the CI-based account in that both approaches assume that the experiential component of kasukani is non-at-issue and projective.Footnote 22

Although this is a matter for careful consideration, I would like to take the position that the experiential element is a CI, not a presupposition. One piece of evidence is that this empirical meaning cannot be challenged by “Hey wait a minute!”

According to the “Hey, wait a minute” test, if p is a presupposition, it can be responded to by another discourse participant with “Hey wait a minute, {I didn’t know that p” (von Fintel, 2004; Shanon, 1976). For example, we can naturally utter “Hey wait a minute! I didn’t know that John has a dog!” in order to challenge the presupposition created by the possessive phrase John’s dog:

In contrast, in the case of the sense-based low degree modifier kasukani, it is not natural to use chotto matte! ‘Hey wait a minute’ in order to challenge (react to) the sense-related experiential component:

The above discussion suggests that the sense-based experiential component is not a presupposition but rather a CI. Intuitively, sense-based low-degree modifiers signal how a judge measures the degree of the predicate in question at the non-at-issue level, and it is not the kind of information that is taken for granted by the speaker and the hearer. Since the theoretical distinction between presupposition and CI is a difficult issue, we will not discuss it further in depth here. One point in common, whether one takes the presupposition approach or the CI approach, is that the experiential meaning of kasukani is non-at-issue, and this point is of utmost importance.

4.2 Notes on the difference with predicates of personal taste

Before closing this section, I would like to briefly discuss the difference between sense-based low-degree modifiers and typical predicates of personal taste such as tasty. Although both sense-based low-degree modifiers and predicates of personal taste have to do with the notion of experience, their properties are different.

First, there is a difference between sense-based low-degree modifiers and typical predicates of personal taste in terms of projectability/obviation. As already discussed in the literature of predicate of personal taste, the experiential meaning (acquaintance inference) triggered by the predicate of personal taste projects in the environment of negation:

However, the experiential inference simply disappears in the environments of conditional, modality, and question (e.g., Ninan, 2014; Ninan, 2013; Anand & Korotkova, 2018; Willer & Kennedy, 2020):Footnote 23\(^{,}\)Footnote 24

Ninan (2020) submits the following generalization for the obviation of the acquaintance inference (see also Ninan (2014); Pearson (2013); Anand and Korotkova (2018); Willer & Kennedy (2020)) (O corresponds to epistemic modals, indicative conditionals and questions):

This point is quite different from the sense-based low-degree modifiers. As I discussed in the previous section, the sensory experiential meaning triggered by the sense-based low-degree modifiers is highly projective (and because of this, relevant sentences in modal, conditional and question environments are often odd).

Furthermore, the predicate of personal taste and the sense-based low-degree modifier are different in terms of changeability of experience. While the direct sensory experiential meaning triggered by the sense-based low-degree adverbs cannot be challenged by “Hey wait a minute!” (see the previous section), the acquaintance inference triggered by the predicate of personal taste can be challenged by “Hey wait a minute!” (see also Ninan, 2014):

Where do these differences come from? I would like to consider that these differences are due to differences in the nature of experience. For sense-based low-degree modifiers, the experience is direct and sensory. Since it is an immediate experience, it is impossible to challenge it with “hey wait a minute!”, and it does not disappear. In contrast, the acquaintance inferences triggered by the predicate of personal taste is not necessarily an immediate direct sensory experience (see also Anand and Korotkova (2018)). Of course, in the case of the adjective oishii ‘delicious’, we can say “X is delicious” while actually eating X; in this case, the experience can be a direct sensory experience, but it can also be an episodic experience in the past. If the experience is an episodic experience in the past, it is possible to object to that experience with “Hey wait a minute! I didn’t know that you have eaten X before”. Although I do not have a clear explanation regarding the property of obviation of acquaintance inference triggered by a predicate of personal taste, it seems possible that the sense-based low-degree modifiers have an immediate direct sensory experience, which is strongly projective, while the predicates of personal taste are less immediate, and have a weaker projective property (see Ninan (2014, 2020); Anand and Korotkova (2018); Willer & Kennedy (2020) for the detailed discussions on the obviation of acquaintance inference).

5 Formal analysis of kasukani

Let us now consider how the meaning of kasukani can be analyzed formally using the following example:

I will analyze the meaning of sense-based low-degree modifiers based on multidimensional semantics (Potts, 2005) in which both an at-issue meaning, and a CI meaning are compositional but are interpreted along different dimensions (i.e., an at-issue dimension and a CI dimension). More specifically, it uses the logic of mixed content (McCready, 2010; Gutzmann, 2012) to analyze the meaning of kasukani. In this system, the meaning of mixed content is computed via a mixed application, as follows:

(Based on McCready (2010)).

The at-issue component is to the left of \(\blacklozenge \), and the non-at-issue component/CI is to the right. Superscript a stands for an at-issue type, and superscript s stands for a shunting type, which is used for the semantic interpretation of a CI involving an operation of shunting.Footnote 25

When the derivation of the CI component of mixed content completes, the following rule applies for the final interpretation of the CI part:

The bullet \(\bullet \) is a metalogical device for separating independent lambda expressions.

Based on the above setup, I propose that kasukani has the following meaning (the variable G is an abbreviated variable for a gradable predicate (measure function) of type \(\langle d^a, \langle e^a,t^a\rangle \rangle \) and j stands for a judge and “\( > rapprox \)STND\(_{MIN.G}\)” slightly greater than a minimum standard of G):

In the at-issue dimension, kasukani takes a gradable predicate G and an individual x and denotes that there is some degree d such that d is slightly greater than a minimum standard of G and barely recognizable. In the CI component, it takes G and conventionally implies that the judge j (typically the speaker) has measured the degree of G based on their senses of sight, smell, taste, hearing, touch, or memory.Footnote 26

As for the meaning of gradable predicates such as amai ‘sweet’, I assume that they represent relations between individuals and degrees (e.g., Seuren, 1973; Cresswell, 1977; von Stechow, 1984; Klein, 1991; Kennedy & McNally, 2005):Footnote 27

Kasukani and amai are subsequently combined via mixed application. Note that as the CI component of kasukani is complete (i.e., its denotation is of type \(t^s\)), kasukani takes the argument amai only at the at-issue component. Figure (68) shows the logical structure of sentence (63) (I have omitted the information of tense and world for the sake of simplicity):

One seemingly puzzling point is the fact that kasukani cannot co-occur with a gradable predicate, such as oishii ‘delicious’, samui ‘cold’ and urusai ‘noisy’ despite the fact that they are sense-related (taste/touch/hearing)(see also Sect.3.1):

Kasukani cannot be combined with oishii ‘delicious’, samui ‘cold’, or urusai ‘noisy’ because these adjectives are relative gradable adjectives that posit a contextual standard (norm) and cannot measure degrees from a minimum point. Whether something is tasty, cold, or noisy is determined by a contextually determined norm. Contrariwise, kasukani is fine with the adjective amai ‘sweet’ because it is an absolute adjective that has a minimum degree (zero point) (Kagan & Alexeyenko, 2011).Footnote 28\(^{,}\)Footnote 29

One puzzling point is that it seems to be a bit difficult for kasukani to arise in comparatives in some environment (especially when a given adjective is a “negative adjective”):Footnote 30

In the case of the comparatives with nigai ‘bitter’, it may be difficult to set the standard of comparison at the derived zero point. The sentence does not seem to fit with the meaning of “barely recognizable in degree” because the coffee being compared is already bitter to some degree. I would like to leave this point for future study.

6 Japanese honokani

We have focused so far on Japanese kasukani. In this section, we consider another Japanese sense-based low-degree modifier, honokani (see also Oki (1983)). Although honokani is similar to kasukani in that it is sense-based, there are also some differences between them. First, the use of honokani is more restricted than kasukani. As the following examples show, honokani can measure degrees based on the senses of sight (color), taste, smell, and touch:

However, honokani cannot measure sound; moreover, at least for some native speakers, measuring the degree of memory based on honokani is a bit odd:

Second, unlike kasukani, honokani has a positive evaluative meaning. As the following examples show, it is odd to use honokani if a predicate does not have a positive meaning:

The above two differences suggest that honokani has a more restricted non-at-issue/CI meaning: Honokani conventionally implies that a judge j measures degree based on a sense of brightness, perfume, or sweetness, and evaluates the experience positively (cf. kasukani):Footnote 31

The sense of brightness, perfume, or sweetness is more specific than the sense of sight, smell, or taste. The positive evaluative component seems to be connected to a specific sense.

7 English faintly

Let us now investigate the meaning and distribution of English faintly. It will be shown that the meaning and distribution patterns of faintly are similar to kasukani but it has a wider distribution pattern than kasukani in that it can directly combine with an emotive predicate.

7.1 Sense and emotion

English faintly is similar to the Japanese kasukani and honokani in that it has a sense-based meaning:

Similar to the other sense-based low-degree modifiers, faintly cannot combine with regular relative gradable predicates such as expensive and tall, as shown in (78):Footnote 32

However, interestingly, faintly can also combine with an emotive predicate:

This characteristic is not found in kasukani or honokani:

7.2 Corpus data of faintly

To understand the distributional tendency of faintly and whether it is dialectal, I examined the collocations of “faintly + ADJECTIVE” in the BNC and COCA.Footnote 33

As for the BNC, the results for the top 20 adjective collocates with faintly (among 100) are shown in Table 3. The following examples are part of the BNC examples:

In COCA, on the other hand, the results of the top 20 adjective collocates with faintly are shown in Table 4.

The following examples are part of the examples from COCA:

The above examples suggest the following observations. First, there is a difference between the BNC and the COCA in terms of the most frequent pattern. The most frequent pattern in the BNC is “faintly ridiculous,” which is an emotive measurement. In contrast, the most frequent pattern in COCA is “faintly visible,” which is a sense-based measurement, and the frequency of “faintly visible” is much higher than the other patterns. Second, in terms of the proportion of emotive and sense-based measurements, of the top 20 adjective collocates, 14 and 7 are based on an emotive adjective in the BNC and COCA, respectively. These results suggest that the use of faintly with an emotive predicate is more often used in British English than in American English. However, we should also acknowledge the fact that faintly can be used in both British and American English for both emotive and sensory measurements, and this does not hold for the Japanese kasukani and honokani.

The question is how we can analyze the meaning of faintly. Based on the philosophical view that emotions are a kind of perception (Roberts, 2003), I assume that faintly has a wider selectional restriction regarding the specification of sense:

Both emotion and sense have to do with a speaker’s experience, and it seems that it is not a coincidence that faintly can measure degrees of emotion and sense. One point we should notice is that the corpus data contain the following examples of indirect measurement:

In these examples, the speaker is not directly measuring the degree of emotion but rather measuring it through sight. In the next section, we will consider the phenomenon of indirect measurement in detail.

8 Indirect measurement

So far, we have mainly discussed the examples of sense-based low-degree modifiers that directly combine with sense-related gradable predicates. However, as we observed in Sects. 1, 3.3 and 7, there are examples of sense-based low-degree modifiers where they combine with non-sense-related gradable predicates and measure their degrees indirectly through a sense that is linguistically expressed by expressions outside the domain of a gradable predicate. In this section, we will consider how we analyze the phenomenon of indirect measurement in a theoretical fashion with special reference to the mechanism of indirect measurement of emotion through perception based on the examples of kasukani and faintly.

8.1 Indirect measurement in the case of kasukani

As we observed in the Introduction, kasukani cannot directly combine with an emotive predicate, but if there is a sense-related expression in the main clause, it can co-occur with an emotive predicate:Footnote 34

In (85b) and (86b), kasukani syntactically and semantically modifies an emotive predicate, denoting that the degree of surprise/sadness is slightly greater than zero, but the measurement is made through the speaker’s perception (sense of sight). Intuitively, examples (85a) and (86a) with kasukani are odd because of the lack of a perception-related expression, whereas (85b) and (86b) appear natural because kasukani interacts with mie-ru ‘look’ or ukabe-ru ‘express’, which are related to perception. In Sect. 3.3, we defined this kind of measurement of non-sensory degree through the senses as indirect measurement.

Some might consider kasukani to be semantically modifying the verb in the main clause (i.e., ukabe-ta ‘express’, mie-ru ‘look’), rather than an emotive predicate. However, I do not see such a possibility for the following reasons. First, if we place kasukani before the main predicate, the sentences become a bit odd:

Second, semantically, the indirect measurement sentence with mie-ru ‘look’ is equivalent to the sentence with perceptive yooda ‘appear’, but since yooda is a suffix (not a verb), kasukani cannot modify yoo-da:

These empirical facts support the idea that kasukani in (85b) and (86b) is measuring the degree of emotion through perception rather than measuring the degree of perception.

Note that yoo-da also has a hearsay evidential use but it does not license kasukani indirectly. If we replace the perception verb mie-ru ‘look’ with the hearsay evidential use of yooda, the sentence sounds less natural:

This makes sense given that hearsay evidence is not related to sense in a physical sense.

The question is how we can analyze these indirect measurements. I claim that the proposed multidimensional approach can successfully capture this. The key point is that, although kasukani directly modifies an emotive predicate, its CI is interpreted (satisfied) at a root level. In the Potts/McCready system, we can capture this using the parsetree interpretation.

For example, in (86b), the CI component of kasukani is embedded (situated below the bullet) as shown in (91). However, if we apply this rule, we can see both the at-issue and CI meanings on the root node, as shown in (92):

In this approach, (85b) and (86b) with kasukani are natural because the sense-related component of kasukani is true in these sentences. Contrariwise, kasukani in (85a) and (86a) sounds odd because the sentences do not ensure that the CI component of kasukani is true.

Indirect measurement can also be found in the nominal domain. In Sect. 3.3, we also observed the following examples of indirect measurements in the BCCWJ corpus.

In these examples, the degree of the emotion (i.e., shame, sadness, and disgust) is measured through a perception that is linguistically expressed by the sense-related suffixes-soo ‘look’ or-ge ‘look’. The crucial point here is that, although -soo and-ge morphologically attach to the stem of emotive adjectives, they semantically take scope over “kasukani + the emotive adjective” (I assume that na is semantically null). Morphologically, na changes the adjectival noun (here kanashi-ge) into to an attributive adjective), as shown in the following figure:

The above examples in (93) are the examples of indirect measurement where kasukani measures the degree of emotion through perception, but there are various examples of indirect measurement concerning other senses. In Sect. 3.3, we observed the following corpus examples, and these can also be analyzed as examples of indirect measurement:

In (95a), kasukani is measuring the degree of goodness through a sense of smell. In (95b), it is measuring the degree of roundness based on a sense of sight or unspecified feeling. In (95c), kasukani is measuring the degree of amusement based on a sense of hearing. Although the syntactic structures of (95) are different from those of (85b) and (86b), these examples can be analyzed in the same way as the above examples of indirect measurements. In other words, the experiential component of kasukani is satisfied outside the domain of adjective.

The question is to what extent indirect measurement is general. For example, one might wonder whether kasukani can combine with a regular adjective, such as furui ‘old’ (not an emotive adjective), if we add a sense-related expression, such as mie-ru ‘look’. While such a pattern seems to be theoretically possible, as shown by the following example, it is odd:

I consider that this combination is odd because of the scale structure of furui ‘old’. Just like the example of oishii ‘delicious’ (see Sect. 5), furui is a relative adjective that posits a contextually determined standard, and this conflicts with the restriction of kasukani in that it measures degree from a minimum standard.Footnote 35

8.2 Indirect measurement in the case of faintly

Let us consider the indirect measurement in faintly. As we observed in Sect. 7, faintly can not only modify sense-related adjectives (e.g., faintly visible) as in (97) but also directly modify emotive predicates as in (98):

Examples in (98) are natural because faintly can directly measure the degree of emotion through j’s sense of emotion (without the aid of other sense-related expressions). I proposed the following lexical item for faintly and claimed that it has a wider selectional restriction regarding the kinds of sense than kasukani:

A crucial point is that faintly can also be used as an indirect measurement. Observe the following examples:

The proposed analysis can also naturally explain the interpretation of faintly in embedded context. In (100a), the judge (j) of faintly corresponds to the subject Bill (not the speaker), and he measures the degree of embarrassment through his emotion. In contrast, in (100b), the judge of faintly is the speaker, who cannot directly measure the degree of amusement. Thus, the only possible reading is where the judge measures the degree of emotion through their sense of sight. The interpretation in (100b) is similar to that of indirect measurement by kasukani:

The indirect measurement is possible because the sense-related experiential component is a CI and can be satisfied globally. The proposed multidimensional approach can successfully capture their interpretations and distributions and judge-dependent/projective behaviors.

9 Conclusion

In this study, I investigated the meaning and use of the Japanese and English sense-based low-degree modifiers kasukani, honokani, and faintly, and claimed that they have sense-related experiential requirements at the non-at-issue level, unlike typical low-degree modifiers. In other words, they not only semantically denote a small degree but also conventionally implicate that the judge (typically the speaker) measures the degree based on their own sense. This means that there are two types of low-degree modifiers in natural language: a “neutral degree modifier” that does not lexically specify the source of measurement (such as the typical low-degree modifiers a bit in English and sukoshi ‘a bit’ in Japanese), and a “sense-based degree modifier” that lexically specifies the source of measurement (i.e., specifies that the measurement is made based on a judge’s own sense).

This study also clarified that there are variations among sense-based low-degree modifiers regarding (i) the kind of sense, (ii) the presence/absence of evaluativity, and (iii) the possibility of the combination with an emotive predicate, as shown in Table 5. I suggested that these variations can be analyzed based on the differences in CI (non-at-issue) components.

I have also discussed the phenomenon of indirect measurement via sense and shown that the experiential requirements of sense-based low-degree modifiers can be satisfied not only directly (locally) but also indirectly (globally). In the direct (local) case, a sense-based low-degree modifier combines with a gradable predicate P, and the experiential component is satisfied in relation to the gradable predicate, which is sense-based (e.g., This sake is faintly sweet). In the indirect (global) case, a sense-based low-degree modifier combines with a gradable predicate P and denotes that the degree of P is very small, but its experiential requirement is satisfied through the predicate that is placed higher (e.g., He looks faintly amused).

These points are theoretically significant because they suggest that there can be a mismatch between the at-issue and the CI levels in the modification structure. Thus, a multidimensional approach can successfully and uniformly capture the direct (local) and indirect (global) measurements.

This study has also clarified the similarities and differences between a sense-based degree adverb and a predicate of personal taste. The literature states that predicates of personal taste, such as tasty, require direct experience (e.g., Pearson 2013; Ninan 2014; Kennedy and Willer 2022). The sense-based low-degree modifiers are similar to predicates of personal taste such as oishii ‘tasty’/tasty in that they have an experiential component, but unlike a predicate of personal taste, the experiential component is satisfied via their interaction with other experience-related elements in the sentence irrespective of whether the measurement is local or global. This suggests that they are a kind of concord phenomenon, and we have analyzed this based on the non-at-issue/CI properties of sense-based low-degree modifiers.

This study will contribute to the expansion of research on experiential semantics and the understanding of evidentiality and experientiality in natural language.

In a future study, more empirical and theoretical investigations should be carried out for the semantics/functions of sense-based low-degree modifiers. In this paper we focused on cases where a sense-based low-degree modifier functions as an adverb and modifies a gradable predicate. However, the sense-based low-degree modifier also has a noun-modifying use as well. As the following examples show, it is possible to paraphrase the sentence with the adverbial kasukani into the sentence with the adjective-modifying kasukana:Footnote 36

The adjective kasukana can modify the sensory nouns such as oto ‘sound’, kaori ‘perfume’, hikari ‘light’.Footnote 37

Note that the noun modifying kasukana ‘faint’ can co-occur with nouns that describe psychological states, such as fuan ‘anxiety’ and fuman ‘dissatisfaction’.

This point is different from the adjective/predicate modifying kasukani ‘faintly’. As we discussed in Sect. 8, kasukani cannot directly modify an emotive predicate:

The noun modifying kasukana ‘faint’ seems to have a wider selectional restriction than the adjective/predicate modifying kasukani ‘faintly’. I would like to leave the mechanism behind this asymmetry for a future study.

Furthermore, there is a question of whether the sense-based measurement can also be found in non-low degree modifiers including high-degree modifiers. As for high-degree modifiers, there are various expressions in natural languages such as totemo ‘very’ and kiwamete ‘extremely’ in Japanese and very and extremely in English, but there seem to be no sense-related high-degree modifiers.Footnote 38 It may be that sense-based degree modifiers are more likely to develop in a situation where the degree in question is so subtle that the senses must be sharpened. More extensive empirical and theoretical investigation is needed.

Abbreviations ATTRI: attributive form, ACC: accusative, COMP: complementizer, COND: conditional, CONF: confirmation, CONT: contrastive, DAT: dative, EVID: evidential, GEN: genitive, HON: honorific, IMP: imperative, LOC: locative, MIR: mirative, NEG: negation, negative, NMLZ: nominalizer, NOM: nominative, Non.PST: non-past tense, PASS: passive, PRF: perfective, POLITE: polite, PRED: predicative, PRES: present, PROG: progressive, Prt: particle, PST: past, Q: question, QUOT: quotative, STATE: state/stative, TE: Japanese te-form, TOP: topic.

Notes

Suruga Bay, the deepest bay in Japan, is 2,500 meters at its deepest point.

In terms of polarity sensitivity, sukoshi, chotto, kasukani, and honokani are all positive polarity items (PPIs) in that they cannot appear in negative environments:

Note that, in the case of sukoshi and chotto, adding mo ‘even’ after the items make them a negative polarity (NPI) (with phonological change in chitto-mo):

Note also that chotto ‘a bit’ also has a speech act use, which weakens the degree of illocutionary force and functioning at a pragmatic/speech act level (e.g., Matsumoto, 1985; Sawada, 2010, 2018); in such cases, chotto can be used in negative environments:

Another possibility is that chotto has an at-issue meaning of ‘a bit’, but it modifies yoku-nai. In such cases, yoku-nai is understood as a single negative grabable predicate meaning ‘bad’ and nai is not construed as regular negation. I thank a reviewer for providing the example.

As with the Japanese low-degree modifiers, the English faintly is a PPI in that it does not appear with negation:

As for a little and slightly, they normally behave as a PPI, but can appear with negation if the sentence is interpreted as a metalinguistic reading/litotes (see Bolinger 1972: 122; Horn 1989: 401; for the detailed discussions on the behavior of a little).

As for a bit, as discussed in Bolinger (1972) and Horn (1989), it can occur in both positive and negative environments, and when it occurs with negation, the negation denotes the absence of a minimal quantity (Bolinger, 1972; Horn, 1989):

Some native speakers may think that a little can be used to convey the meaning of (vib). I thank a reviewer for bringing this to my attention.

Here only some of the Class 1 and Class 2 modifiers are listed; for the behavior of slightly, see Sect. 2.

I thank the editor and a reviewer for their valuable comments regarding this point.

Japanese also has wazukani ‘slightly’ that is used in the context of extremely precise measurement, and there is only a functional reading in that case:

Historically, kasuka ‘faint’ also meant ‘shabby looking’ or ‘poor looking’.

Note that the following example is odd because the first and second parts are unrelated:

Note that su-ru is not compatible with the sense of sight.

Note that the sentence with kasukani amai sounds natural if a speaker is looking at a label that explicitly says “this coffee is faintly sweet”:

I consider this sentence to be metalinguistic as opposed to a pure measurement. The speaker is not measuring degrees themself, but states a fact furnished by another. In this paper, I will not discuss this kind of example.

A predicate such as fun is also considered to be a typical example of a personal taste (see, e.g., Lasersohn, 2005), but it seems that, unlike tasty, fun is not dependent on a particular sense.

I thank a reviewer for the valuable comment regarding this point.

Note that the sensory experiential meaning derived from kasukani is not cancellable:

This suggests that the sensory experiential meaning is not a conversational implicature.

Kamoshirenai ‘may’ in this example is not a typical modality expression in that it does not express the speaker’s inference, but rather the speaker’s confirmatory judgment of reality.

In order to check the interpretation of this sentence, I administered a questionnaire survey to 22 undergraduate and graduate students at Kobe University on May 19 and 25, 2023, via Google form. All of them are native speakers of Japanese. In the questionnaire I asked the informants how natural sentence (50) with sukoshi and sentence (50) with kasukani are based on a 7-point scale (where 1 = completely odd and 7 = completely natural). The results show that many native speakers consider the sentence with kasukani to sound unnatural:

In the same questionnaire, I asked the informants the naturalness of sentence (51). Similar to (50), many informants found the sentence with kasukani unnatural:

As a reviewer pointed out, if we use the (no)nara conditional, which indicates that the speaker is taking into account what the hearer has said, then kasukani can be used more naturally in conditional sentences:

In this case, the content of the conditional clause is assumed to be true and the experiential component is also assumed to be satisfied. As shown in the table below, naturalness has improved:

The following figure shows the informants’ judgments on (52):

The following results show the same informants’ judgments on (53):

The following results show the same informants’ judgments on (54):

In the case of predicates of personal taste, the acquaintance inference is often analyzed as a presupposition (e.g., Pearson, 2013; Ninan, 2014, 2020), while Muñoz (2019) analyzes the evidentiality of predicates of personal taste based on the notion of CI. However, to the best of my knowledge, there is no substantial discussion on whether the acquaintance inference is a CI or presupposition. For example, Ninan (2014), when considering the direction of analyzing the acquaintance inference of predicates of personal taste using the concept of presupposition, argues that it is not a CI as Potts (2005) proposes. This is because, compared with typical CIs (e.g., expressive, supplemental, etc.), acquaintance inference has a limited number of environments in which it can be projected. However, CI does not always project in any embedding environment (Amaral et al., 2007; Harris & Potts, 2009; Sawada, 2018), making it not a substantial criteria. Ninan (2014) notes that the “hey, wait a minute” test also suggests that the acquaintance inference is a presupposition, but there are various views/analyses for the semantic status of predicate of personal taste. See also Sect. 4.2.

Note that, as Ninan (2014) observes, the question in (60d) does not imply that the speaker has tasted the lobster rolls, but it does suggest that the hearer has. (In the literature, the non-speaker-oriented reading is often called an exocentric reading, which contrasts with the more usual autocentric reading (see Lasersohn, 2005: 670ff; Ninan, 2014).

As Ninan shows, the above special behavior of projective behavior strongly contrasts with the typical presupposition triggered by, for example, stop:

The following figure shows the shunting application:

The shunting application is different from Potts’ (2005) CI application, where it is resource sensitive. Potts’s CI application is resource insensitive, as shown in (ii):

The superscript c represents the CI type, which is used for CI application. Here, the \(\alpha \) of \(\langle \sigma ^a,\tau ^c\rangle \) takes a \(\beta \) of type \(\sigma ^{a}\) and returns \(\tau ^{c}\). Simultaneously, a \(\beta \) is passed on to the mother node.

Here, the CI of kasukani is taken as information related to the act of how the judge is weighing the degree in question. Kasukani is not evaluative in the sense that it does not express the speaker’s attitude toward the degree of the at-issue. Rather, the act of measurement based on the sense and measurement at the at-issue level are taking place simultaneously. This point is different from the mixed content Kraut, which denotes German in the at-issue domain and additionally conveys that the speaker has a negative attitude toward German people (McCready, 2010; Gutzmann, 2011).

Here, I consider that the unmodified adjective sweet/amai is of the same type as the usual gradable adjective, and no judge variable (j) is assumed. In positive adjective sentences, sweet/amai is evaluated in relation to the speaker’s minimum standard, and I assume that the standard is introduced by a positive form (pos) or a degree modifier. This is where the judge variable is introduced. In comparative sentences, the unmodified adjective is attached to the comparative morpheme.

In order to check the naturalness of the example in (69), a questionnaire was administered to 22 native speakers (undergraduate and graduate students at Kobe University) on May 25 and 26, 2023, through a Google form. The following are the results:

In the same questionnaire, I also asked about the naturalness of the following typical examples of sense-based low-degree modifiers:

Unlike the examples in (69), these examples were judged as very natural:

Kagan & Alexeyenko (2011) argue that the Russian adjective sladkij ‘sweet’ posits a lower-bound closed scale based on the modification test by slegka ‘slightly’ and soveršenno ‘absolutely’:

The fact that the sentence with soveršenno ‘absolutely’ is odd suggests that skadkij ‘sweet’ does not posit an upper-closed scale (which has a maximum endpoint).

The following are the result of the native speakers’ judgment on (70) and (71) (the examples were all provided in the same questionnaire).

The Japanese adverb honnori has the same semantic characteristics as honokani.

One of the anonymous reviewers and a participant of LSA 2021 suggested that examples such as “The violin sounds faintly expensive” and “This wine is faintly expensive” could be natural if the judge has some knowledge of how acoustic properties of a violin/qualities of a wine map to the expensiveness of the violin/wine.

The BNC is designed to represent a wide cross-section of British English, both spoken and written, from the late 20th century. (http://www.natcorp.ox.ac.uk/). COCA is a large, genre-balanced corpus of American English (https://www.english-corpora.org/coca/).

Even if the subject is in the first person, kasukani ‘faintly’ cannot modify an emotive predicate:

Some native speakers consider that the following example sounds natural, although there is no perception verb in the main clause:

This sentence seems to be relatively natural because the verb omoi-dasu ‘remember’ is present in the when-clause, which is concerned with memory and experience. However, the sentence may still sound a bit unnatural because it is not clear how the speaker relates to the degree of sadness and memory.

Strictly speaking, kasukana consists of the adjectival noun kasuka plus na that makes the adjectival noun an attributive adjective.

Note that the adjective kasukana ‘faint’ can also modify a modality-related noun kanousei ‘possibility’:

The Japanese noun-modifying adjective houjun-na ‘well-mellowed, mellow’ represents a high degree of mellowness and is related to perfume and taste (e.g., houjun-na wain ‘well-mellowed wine’, houjun-na kaori ‘mellow aroma’), but it cannot modify adjectives and thus does not seem to be a typical degree modifier.

References

Amaral, P., Roberts, C., & Smith, A. E. (2007). Review of the logic of conventional implicatures by Chris Potts. Linguistics and Philosophy, 30(6), 707–749. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10988-008-9025-2

Anand, P., & Korotkova, N. (2018). Acquaintance content and obviation. Proceedings of Sinn und Bedeutung, 22(96), 55–72.

Bolinger, D. (1972). Degree words. Mouton.

Bylinina, L. (2012). Functional standards and the absolute/relative distinction. Proceedings of Sinn und Bedeutung, 16, 141–157.

Cresswell, M. J. (1977). The semantics of degree. In B. Partee (Ed.), Montague grammar (pp. 261–292). Academic Press.

Grice, P. H. (1975). Logic and conversation. In P. Cole & J. Morgan (Eds.), Syntax and semantics III: Speech acts (pp. 43–58). Academic Press.

Gutzmann, Daniel. (2012). Use-conditional meaning. Ph.D. thesis, University of Frankfurt.

Gutzmann, D. (2011). Expressive modifiers and mixed expressives. Empirical Issues in Syntax and Semantics, 8, 123–141.

Harris, J. A., & Potts, C. (2009). Perspective-shifting with appositives and expressive. Linguistics and Philosophy, 32(6), 523–552. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10988-010-9070-5

Horn, L. R. (1989). A natural history of negation. University of Chicago Press.

Kagan, O., & Alexeyenko, S. (2011). Degree modification in Russian morphology: The case of the suffix-ovat. Proceedings of Sinn und Bedeutung, 15, 321–355.

Kamiya, T. (2002). The handbook of Japanese adjectives and adverbs. Kodansha.

Kennedy, C. (2007). Vagueness and grammar: The semantics of relative and absolute gradable adjectives. Linguistics and Philosophy, 30(1), 1–45. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10988-006-9008-0

Kennedy, C., & McNally, L. (2005). Scale structure, degree modification, and the semantics of gradable predicates. Language, 81, 345–381. https://doi.org/10.1353/lan.2005.0071

Kennedy, C., & Willer, M. (2022). Familiarity inferences, subjective attitudes and counterstance contingency: Towards a pragmatic theory of subjective meaning. Linguistics and Philosophy, 45, 1395–1445. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10988-022-09358-x

Klein, E. (1991). Comparatives. In A. von Stechow & D. Wunderlich (Eds.), Semantik: Ein internationales Handbuch der zeitgenössischen Forschung (pp. 673–691). Walter de Gruyter.

Lasersohn, P. (2005). Context dependence, disagreement, and predicates of personal taste. Linguistics and Philosophy, 28(6), 643–686. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10988-005-0596-x

MacFarlane, J. (2014). Assessment sensitivity: Relative truth and its applications. Oxford University Press.

Matsumoto, Y. (1985). A sort of speech act qualification in Japanese: Chotto. Journal of Asian Culture, 9, 143–159.

McCready, E. (2010). Varieties of conventional implicature. Semantics and Pragmatics, 3, 1–57. https://doi.org/10.3765/sp.3.8

Muñoz, P. (2019). On tongues: The grammar of experiential evaluation: Ph.D. thesis, University of Chicago.

Ninan, D. (2014). Taste predicates and the acquaintance inference. Proceedings of Semantics and Linguistic Theory, 24, 290–304. https://doi.org/10.3765/salt.v24i0.2413

Ninan, D. (2020). The projection problem for predicates of taste. Proceedings of Semantics and Linguistic Theory, 31, 753–778. https://doi.org/10.3765/salt.v30i0.4809

Oki, H. (1983). Chiisana teido o arawasu fukushi no matorikkusu [The matrix of the adverbs that represent a small degree]. In M. Watanabe (Ed.), Fukuyougo no kenkyuu [Studies of adverbial expressions] (pp. 199–215). Meiji Shoin.

Pearson, H. (2013). A judge-free semantics for predicates of personal taste. Journal of Semantics, 30(1), 103–154. https://doi.org/10.1093/jos/ffs001

Potts, C. (2005). The logic of conventional implicatures. Oxford University Press.

Potts, C. (2007). The expressive dimension. Theoretical Linguistics, 33, 165–197. https://doi.org/10.1515/TL.2007.011

Roberts, R. C. (2003). Emotions: An essay in aid of moral psychology. Cambridge University Press.

Sassoon, G. (2012). A slightly modified economy principle: Stable properties have non-stable standards. In Proceedings of the Israel Association of Theoretical Linguistics (IATL) 27. MIT working papers in linguistics, pp. 163–182.

Sawada, O. (2010). Pragmatic aspects of scalar modifiers. Ph.D. thesis, University of Chicago.

Sawada, O. (2018). Pragmatic aspects of scalar modifiers: The semantics-pragmatics interface. Oxford University Press.

Sawada, O. (2019). Varieties of positive polarity minimizers in Japanese: Granularity, multidimensionality, and the modes of measurement. Kobe University.

Seuren, P. A. M. (1973). The comparative. In K. Ferenc & R. Nicolas (Eds.), Generative grammar in Europe (pp. 528–564). Reidel.

Shanon, B. (1976). On the two kinds of presupposition in natural language. Foundations of Language, 14, 247–249.

Solt, S. (2012). Comparison to arbitrary standards. Proceedings of Sinn und Bedeutung, 16, 557–570.

Solt, S. (2015). Vagueness and imprecision: Empirical foundations. Annual Review of Linguistics, 1, 107–127. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-linguist-030514-125150

von Fintel, K. (2004). Would you believe it? The King of France is back! Presuppositions and truth-value intuitions. In M. Reimer & A. Bezuidenhout (Eds.), Descriptions and beyond (pp. 315–341). Oxford University Press.

von Stechow, A. (1984). Comparing semantic theories of comparison. Journal of Semantics, 3, 1–77. https://doi.org/10.1093/jos/3.1-2.1

Willer, M., & Kennedy, C. (2020). Assertion, expression, experience. Inquiry, 65(7), 821–857. https://doi.org/10.1080/0020174X.2020.1850338

Acknowledgements

I am very grateful to the editor Regine Eckardt and the reviewers of Linguistics and Philosophy for their valuable and constructive comments and suggestions, which significantly improved the manuscript. I am also very grateful to Daisuke Bekki, Patrick Elliot, Thomas Grano, Richard Harrison, Ikumi Imani, Wesley Jacobsen, Chris Kennedy, Hideki Kishimoto, Ai Kubota, Yusuke Kubota, Sophia Malamud, Yo Matsumoto, Yoko Mizuta, Kenta Mizutani, Harumi Sawada, Jun Sawada, Koji Sugisaki, Eri Tanaka, and Satoshi Tomioka for their valuable comments and discussions on the current or earlier versions of this paper. Parts of this paper were presented at the International Conference on English Linguistics (2020), the seminar at Kwansei Gakuin University (2021), ICU Linguistics Colloquium (2021), LSA (2021), LENLS 18 (2021), Oxford Kobe Linguistics Symposium (2023), and Evidence-based Linguistics Workshop (2023), the audiences at which I also thank for their valuable comments. This study was supported by JSPS KAKENHI (Grant numbers JP21K00525, JP22K00554) and the NINJAL collaborative research project, “Evidence-based Theoretical and Typological Linguistics.” All remaining errors are, of course, my own.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The author declares that there are no conflict of interest associated with this manuscript.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Sawada, O. Sense-based low-degree modifiers in Japanese and English: their relations to experience, evaluation, and emotions. Linguist and Philos 47, 653–702 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10988-023-09404-2

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10988-023-09404-2