Abstract

The existence of negative descriptions denoting events is controversial in the literature, since it implies enriching the semantic ontology with negative events. The goal of this article is to argue that the readings that have been called ‘negative events’—in contrast to sentential negation reading—should be analysed as inhibited eventualities. We will argue that the inhibited eventuality reading emerges when negation scopes over the verbal domain. Sentential negation, in contrast, scopes above the existential closure of the event variable. We will implement the analysis in a framework where the verbal domain combines symbolic objects that yield partial event-descriptions. These descriptions do not entail the existence of a Davidsonian eventuality with time and world parameters until they transition to the aspectual level. We will show that an analysis on these terms can capture the empirical properties of non-sentential negation without the need to propose negative events as objects in the ontology.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

“Is there any point to which you would wish to draw my attention?”

“To the curious incident of the dog in the night-time.”

“The dog did nothing in the night-time.”

“That was the curious incident,” remarked Sherlock Holmes.

The Memoirs of Sherlock Holmes (1893)

1 Introduction: ‘Negative event’ readings without negative events

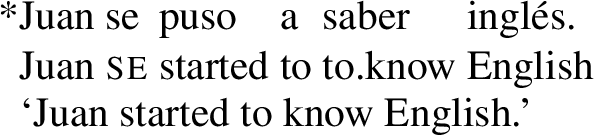

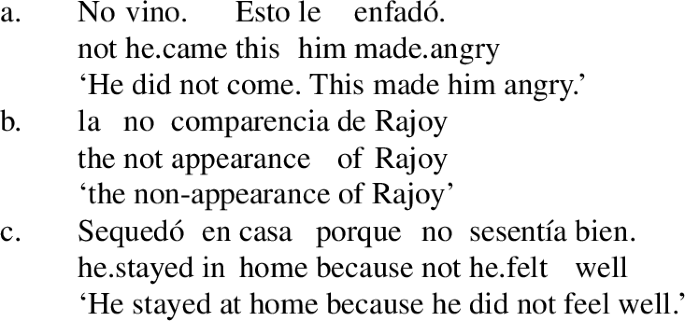

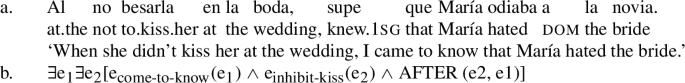

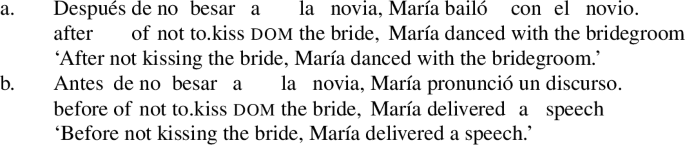

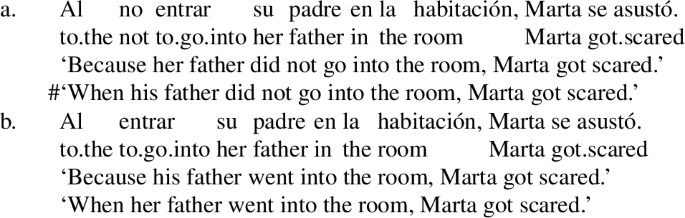

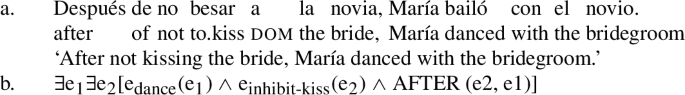

One of the most debated issues in the syntax and semantics of aspect is whether natural languages can refer to events through negative descriptions. This question goes, at minimum, back to the 1970s, when Stockwell et al. (1973:250–251) pointed out that negative verbal phrases such as not paying taxes, not getting up early, not going to church, etc. should be treated as events, specifically, as “negative events” that denote the absence of an otherwise expected event. An example for a negative event as proposed by Stockwell et al. (1973)—the type of reading that we will argue is in fact an inhibited eventuality—is provided in (1).Footnote 1

-

(1)

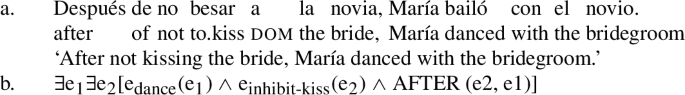

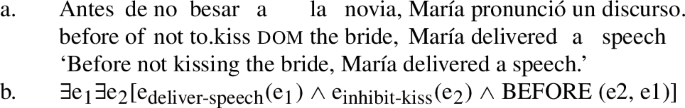

Imagine a context in which the expectation that María kisses the bride exists; for instance, a wedding, where it is expected for the guests to compliment the bride (Higginbotham 2000). In such a context, reporting a situation in which María refrains from kissing the bride is relevant: (1) describes that the speaker saw that María failed to kiss the bride.Footnote 2

Soon after this proposal, other scholars noted that allowing negative events in the ontology is problematic both from the perspective of what negation denotes and of how the truth conditions of the sentence would be defined. Alternative proposals treating such examples as denoting states or facts (Horn 1989:51–55; Asher 1993:215–221; Verkuyl 1993:163; Kamp and Reyle 1993; de Swart and Molendijk 1999:5) promptly emerged. Despite the current consensus that negative verbal phrases cannot denote negative events, several works have provided evidence for the opposing point of view (Higginbotham 1983; Cooper 1997; Przepiórkowski 1999; Weiser 2008; Arkadiev 2015, 2016).

We agree that including negative events in the semantic ontology is problematic. The goal of this article is to provide an account of cases originally described as ‘negative events’ using negation scope. We will provide evidence that even though it is possible for negative verbal phrases to denote eventualities—at least in the case of SpanishFootnote 3—this reading should rather be analysed as an inhibited eventuality.Footnote 4 In our analysis, an inhibited eventuality reading is obtained when the negative operator scopes over the initiation subevent within the eventuality description, therefore denoting the inhibition of the causal relation leading to the processual part of the event. We will show that this proposal captures the main properties of so-called negative events without needing to posit that they are members in the semantic ontology.

The article is structured as follows. In the next section (Sect. 2), we will present different structures that allow us to differentiate the syntactic and semantic properties of the inhibited eventuality reading from the sentential negation reading. The section will provide syntactic evidence that the inhibited eventuality reading correlates with a low syntactic position for negation in the structure in Spanish; if it is placed in a structurally high position, such as Laka’s (1990) Negative Phrase, the sentential negation reading—or negated event reading—emerges. In Sect. 3 we will discuss the aspectual and the argument structure properties of inhibited eventualities and show that they do not denote facts. In fact, these eventualities pattern with events in most of their properties, while sharing some properties with states—leading some authors (such as Horn 1989; Verkuyl 1993) to argue that they actually denote states. Section 4 presents our analysis, where we follow Ramchand (2018) in making a crucial distinction between two different domains: a lower domain, where symbolic objects are combined producing descriptions of events, and a higher one, where these descriptions are used to convey an eventuality. We will propose that inhibited eventualities involve negation over the lower domain. More specifically, we contend that negation denies the causal link between initiation and process (Init and Proc in Ramchand 2008). This yields an inhibition relation that is used to convey an event whose existence is asserted, later on. In Sect. 5, we will show how our account explains the properties of inhibited events, in particular, that they refer to eventualities and share properties with both events and states.

2 Disentangling the inhibited eventuality reading from sentential negation

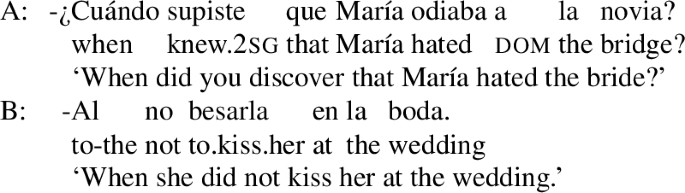

The literature generally accepts that negation can have a second reading—in addition to sentential negation (negated event reading)—when it takes scope over a phrasal verb. We, too, defend that negation may give rise to two readings in this context. In line with Klein (1994:49), we, more specifically, claim that negation can be used to either negate that an event took place or to affirm that an inhibited eventuality occurred. A negative sentence such as El niño no comió ‘The boy didn’t eat’ therefore, receives two interpretations: ‘It did not happen that the boy ate’ (sentential negation reading) and ‘It happened that the boy didn’t eat’ (inhibited eventuality reading). While it is difficult to disentangle the two readings through their truth conditions in this type of structure, we will show that there are syntactic environments where these two readings are clearly distinguished, in this section. This constitutes evidence in favour of the existence of the inhibited eventuality reading.

Spanish provides environments where negated event and inhibited eventuality readings are, in fact, distinguishable by the syntactic position of negation (see also Ramchand 2005 for the case of Bengali, Arkadiev 2015 for the case of the perfect form in Lithuanian and González Rodríguez 2015 for the case of some Spanish periphrases).

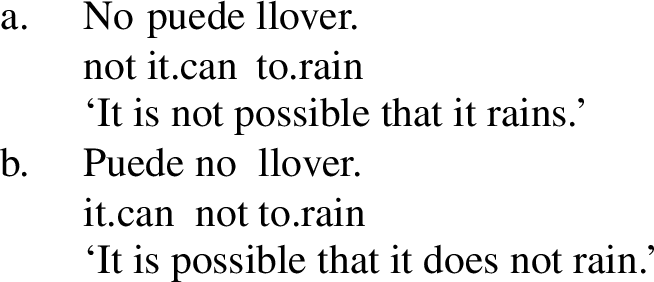

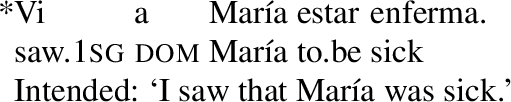

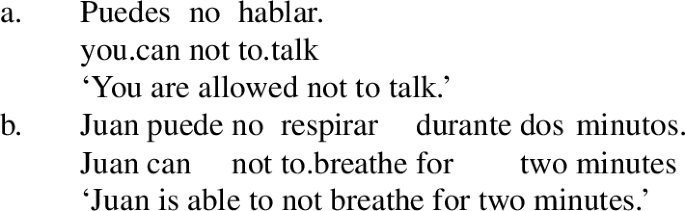

The first environment consists of the modal periphrases poder ‘can’ and deber ‘must’. Note that both the auxiliary and the main verb can be preceded by negation, in these periphrases. Crucially, this difference in position leads to distinct interpretations.Footnote 5 Consider the examples in (2):

-

(2)

While we assert that there is no possible situation where it rains in (2a), we assert something different in (2b): that there is a possible situation where it will not rain. In this second case, we contend, what it is asserted is the possibility of an inhibited eventuality occurring.Footnote 6 That (2a) and (2b) receive different interpretations is shown by the fact that different contexts satisfy their truth conditions. Imagine a sunny day without clouds in the sky, for example. In this context, the utterance in (2a) is appropriate, whereas (2b) sounds awkward. In the described context, we hope that it does not rain. Therefore, we can refute the possibility of the event of raining taking place, but it is infelicitous to affirm that the inhibited eventuality of not raining could take place.

The distinction is more explicit with deontic modals.Footnote 7 Compare the two sentences in (3):

-

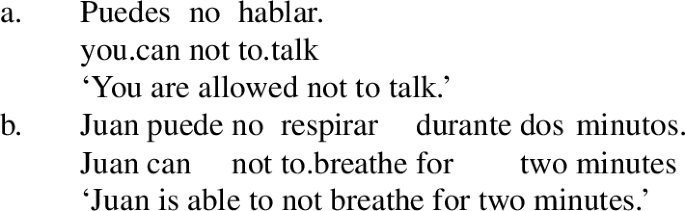

(3)

In (3a), the addressee’s permission to talk is denied: that is, we deny that the permission applies to him or her. For our purposes, (3b) delivers the crucial interpretation. Here, the addressee’s permission to perform an action is asserted. What action is permitted? The action not to talk, that is, to participate in an event of not talking.

Additionally, the presence of two negations is possible in this context: one modifying the auxiliary and one modifying the main verb. Thus, each negation must deny a separate thing:

-

(4)

(4) asserts that the addressee does not have permission to perform a particular action: the action of not paying taxes.

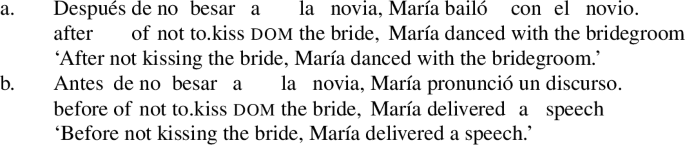

A second context differentiating the two readings by means of an auxiliary is the inchoative periphrasis <empezar a + infinitive>. (5) expresses the moment in which Fernando started to smoke.

-

(5)

In this periphrasis, the negative particle no ‘not’ can precede the auxiliary verb (see (6a)) or the infinitive (see (6b)) in a parallel fashion to modal periphrases.

-

(6)

When negation precedes the auxiliary (<no empezar a + infinitive>), an event is negated. Let us illustrate this point:

-

(7)

This construction includes three predicates (to read the literature, to make summaries and to study them), which constitute arguments for the conclusion ‘Paul was highly motivated.’ The first two arguments (to read the literature and to make summaries) point towards that conclusion because the events denoted by them occurred. In contrast, the last argument (to study them) is negated. Consequently, it reverses the argumentative orientation, as shown by the presence of the adverb however.

In contrast, when the negative particle precedes the infinitive (<empezar a no + infinitive>), an inhibited eventuality is asserted, because the last argument of the sequence occurred. Let us compare (7) to (8):

-

(8)

The conclusion associated with (8) is that Paul was not motivated. The arguments inviting this conclusion are the following: to enrol in only three subjects, to forget to buy the textbooks and not to attend class. It must be noted that the last argument in (8) is not a positive event—as in (7)—but the inhibited eventuality of not attending class; that is, the eventuality of Paul refraining from attending class. Negation, therefore, does not deny that the event has taken place. Instead, all arguments are affirmed. As a consequence, the argumentative orientation is not reversed, as shown by the impossibility of introducing sin embargo ‘however’:

-

(9)

3 The low negation reading involves inhibited eventualities with an initiator

There is strong disagreement with respect to whether the reading not corresponding to sentential negation denotes an event or another kind of semantic object. Some authors argue that the reading denotes an event (Cooper 1997; Przepiórkowski 1999; Weiser 2008; Arkadiev 2015, 2016, among others) while scholars such as Asher (1993, although with caveats) and Kamp and Reyle (1993) propose that it refers to higher-level objects, such as facts. Still others, such as Horn (1989), de Swart (1996) and de Swart and Molendijk (1999), propose that it denotes an eventuality, albeit a stative one. In this section, we will examine the empirical properties of that second reading and conclude that it involves an eventuality, not a fact (Sect. 3.1). The aspectual properties of this eventuality share many properties with events, but also exhibit some stative properties—hence our use of ‘eventuality’ rather than ‘event’—(Sect. 3.2). We will further show that the inhibited eventuality reading can only emerge when the predicate contains an initiator (Sect. 3.3).

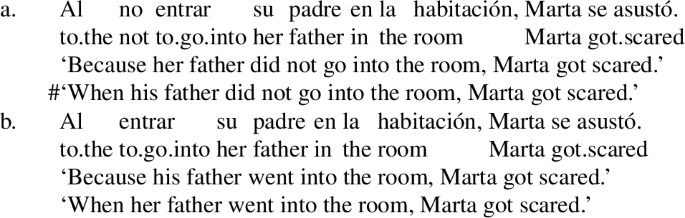

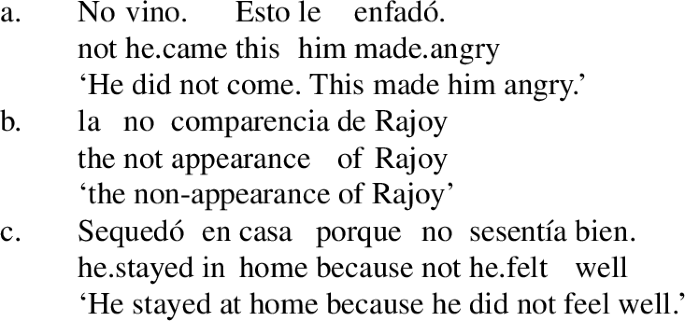

3.1 The low negation reading denotes eventualities, not facts

The empirical evidence for inhibited events denoting eventualities—reviewed in detail by Przepiórkowski (1999)—stems from the possibility of introducing verbal phrases modified by negation in contexts that reject facts.Footnote 8 The data introduced in this section are incompatible with negative descriptions denoting facts. The data do not allow us to determine whether they refer to states or events, however. We will discuss the aspectual properties of inhibited eventualities in the following section (Sect. 3.2).

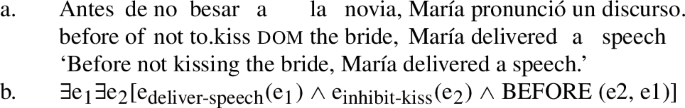

A first piece of evidence comes from temporal adverbials. As pointed out by Higginbotham (1996) and Asher (1993), these adverbials modify eventualities, not facts (see (10)). The grammaticality of (11), therefore, indicates that negative descriptions can refer to eventualities. The relevant reading states that an eventuality occurred. Thus, an eventuality can occupy a specific time period (Cooper 1997:12).

-

(10)

-

(11)

Note that the presence of durative modifiers also enables the selection of the non- sentential negation in contexts where the absence of a second verbal form makes it impossible to differentiate the two readings by the position of negation. Let us see why:

Sentential negation denies the existence of an eventuality and, consequently, the existence of an object with temporal extension. If the existence of an eventuality is denied, it is not possible to assert that the eventuality has a particular temporal extension. Once the durative modifier in (11) is present, there are only two possible readings of the sentence. Both exclude the sentential negation reading. Trivially, negation can affect only the durative modifier. In this case, it is asserted that the prisoner ate, but it is denied that it was during two days: this reading is forced in (12).

-

(12)

Excluding this reading, (11) can only be interpreted as non-sentential negation, more specifically as asserting that the event of the prisoner eating was inhibited for two days. In this reading, an eventuality carrying temporal duration exists, but corresponds to a negative description. Thus in this reading—the crucial one for our purposes—negative polarity items can be licensed.

-

(13)

The reading where negation only takes the durative phrase under its scope cannot license other polarity items, as expected from the properties of sentential negation.

-

(14)

We will return to these durative modifiers in Sect. 3.2, because their distribution provides evidence that the negation alters the Aktionsart of the verbal predicate, adding properties that are characteristic of states (de Swart 1993) in the negative description reading. For the time being, the relevance of these modifiers is grounded in the fact that they constitute an argument in favour of treating this reading as denoting an eventuality.

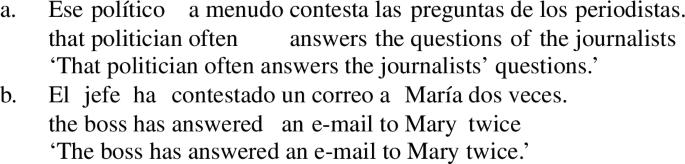

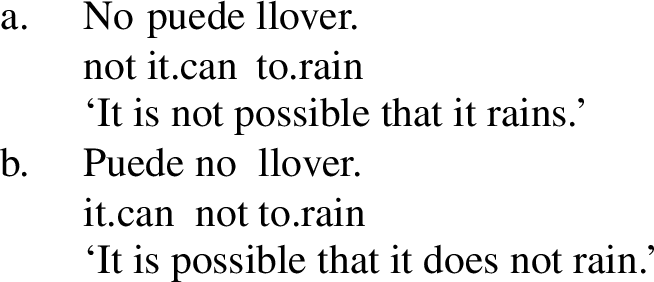

Consider now adverbs of frequency and iteration. As shown in (15a), where a menudo ‘often’ quantifies over the event denoting the frequency with which it occurs (Mourelatos 1978; Hoepelman and Rohrer 1980; Bertinetto 1986; de Swart 1993), adverbs of quantification modify eventualities. The same applies to cardinality adverbials as long as they are in postverbal position (see (15b)). Crucially, adverbs of quantification and cardinal adverbials cannot modify facts. This is illustrated by the ungrammaticality of (16).

-

(15)

-

(16)

Thus, the ability of adverbs of quantification and postverbal cardinal adverbials to take scope over negation provides evidence against a facts account of the negative reading discussed here. These adverbial phrases must modify eventualities, as illustrated by the contrast between (15) and (16), and in (17), where adverbial phrases outscope negation implying that an eventuality must be found.Footnote 9 (17a) expresses that the frequency of the event of the politician not answering the journalist’s questions taking place is high; (17b) denotes that the event of the boss not replying to an e-mail to Mary has taken place twice.Footnote 10

-

(17)

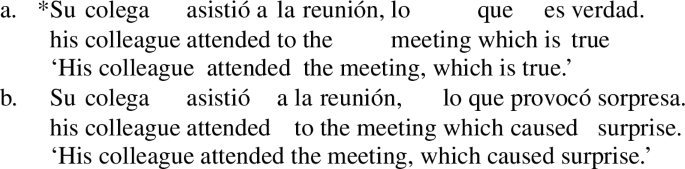

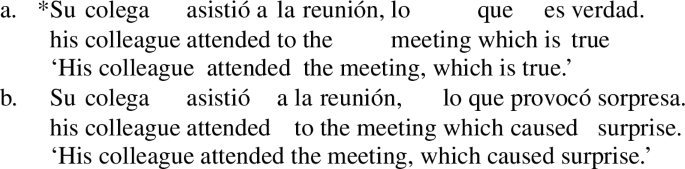

A third argument against relating the negative description to facts is based on relative clauses. Relative clauses can modify eventualities, but not facts, as Przepiórkowski (1999) points out. This is shown by the contrast in (18). (18a), where the predicate of the relative clause requires a proposition or a fact as an antecedent, is illicit. In contrast, the relative clause in (18b) does not select a proposition or fact, but an eventuality as its antecedent; more specifically, the antecedent of the relative clause is the eventuality introduced in the previous clause. Thus, the event of his colleague attending the meeting is that caused surprise.

-

(18)

Crucially, if a negation modifying the verbal phrase is introduced in (18b), the relative clause is still possible, as shown in (19). Because the relative clause in (19) must modify an eventuality, not a proposition or a fact, the grammaticality of the sentence provides evidence in favour of the claim that the non-sentential negation reading does not express a fact. The sentential negation reading, on the other hand, is excluded because an eventuality is required.Footnote 11

-

(19)

3.2 Inhibited eventualities have mixed properties between events and states

We will now discuss what kind of eventualities these negative descriptions denote, that is, whether they refer to states or events. As we will show, inhibited eventualities pattern with events in most diagnostics. They also display some stative-like properties, however. In this section, we describe their eventive and stative properties while we will leave the explanation of this mixed behaviour for Sect. 5.

Several tests show that inhibited eventualities pattern with events.Footnote 12 One such test involved anaphoric reference by esto sucede ‘this happens’. This test was proposed by Davidson (1969) in order to argue for the existence of an event variable in action sentences. Accordingly, stative verbs do not contain an event variable, if, and because, esto cannot refer to them. The same test is used by Maienborn (2005), who shows that esto sucede can refer back to eventive predicates (see (20b–d)) but not to states (see (20a)).

-

(20)

The behaviour of the reading attained when low negation is present patterns with events in this context. Consider (21), where the relevant reading is forced by a durative modifier.

-

(21)

Second, events, unlike states, can be referred to by the do-so anaphor in pseudo-cleft sentences (Lakoff 1966).

-

(22)

Also in this respect, inhibited eventualities behave like ‘regular’ events, as illustrated in (23). Notice that this example is only grammatical in the inhibited eventuality interpretation (‘it is the case that Juan fails to sell houses’).

-

(23)

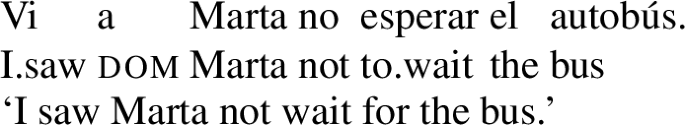

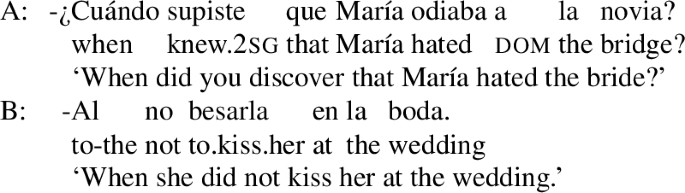

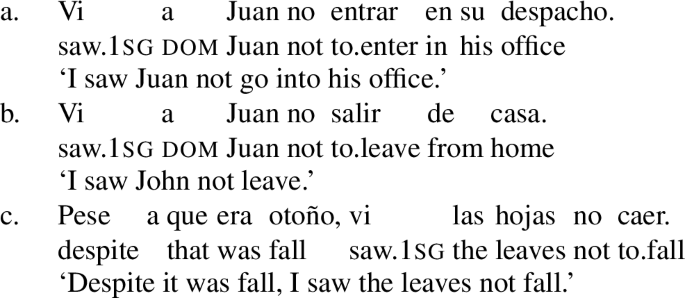

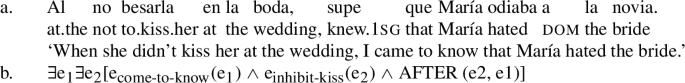

A third instance where inhibited eventualities have the properties of events is provided by perception verbs. These verbs can take DPs, infinitive clauses and finite clauses as complement, as illustrated in (24). As pointed out by Dretske (1969) and Mittwoch (1990) (cf. also Hintikka 1969; Thomason 1973; Barwise 1981) the interpretation of these complements varies. In (24a), the complement—a DP—denotes an entity; in (24b), the verb’s complement refers to an event; in (24c), the complement denotes a proposition, since the embedded clause is finite. Note that the different denotation of the complements in (24) is related to the interpretation of the perception verb. In (24a) and (24b), we get non-epistemic readings, in which the verb denotes direct sensorial perception. These sentences describe a situation in which John is conscious of the physical experience of seeing a book and the event of someone obeying, respectively, with his eyes. In contrast, the perception verb in (24c) carries the epistemic reading, since it refers to the acquisition of knowledge. The example refers to a situation in which John has acquired particular knowledge, specifically the knowledge that Mary obeyed. This reading does not imply that John saw Mary when she was obeying. It would, therefore, be appropriate in a context where someone ordered Mary to clean her room and John later sees that Mary’s room is clean, for example, and infers that she obeyed.

-

(24)

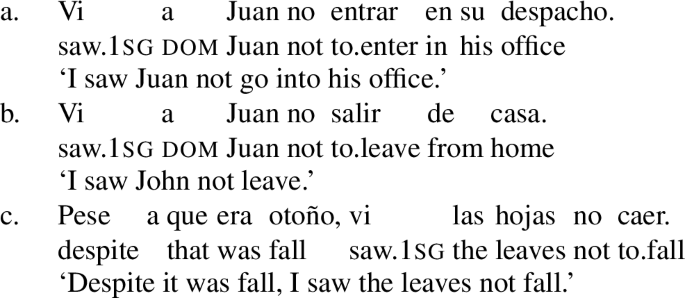

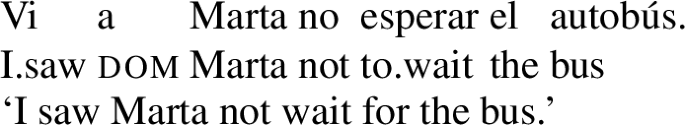

The difference between (24b) and (24c) is especially relevant for the low negation reading, since it provides a context which allows us to distinguish between eventualities and propositions. If the low negation reading involves eventualities, an infinitive modified by negation should, thus, be able to be embedded under a perception verb. This prediction is borne out, as illustrated in (25), where the complement must be interpreted as an eventuality.

-

(25)

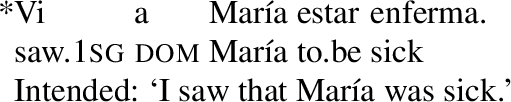

Inhibited eventualities also pattern with events in infinitival constructions. The ungrammatical examples in (26) involve infinitives denoting different kinds of states—some more obviously externally perceivable than others. The generalisation (at least) for (Peninsular) Spanish is that an infinitive acting as a complement of a perception verb must denote an eventFootnote 13 (De Miguel 1999; Jaque 2014). See also Maienborn (2003, 2005) for the observation that this structure only selects infinitives denoting events—dynamic or not—also in German. Spanish behaves in the same way as Maienborn reports for German and rejects all types of states:

-

(26)

Given the grammaticality of (1) and (25) in contrast to (26), we conclude that the object the negation and the infinitive express, here, must be an event, not a state.

Inhibited eventualities are compatible with temporal adverbials and adverbs of frequency and iteration as shown above. This property does not exclude the possibility of inhibited eventualities denoting states, given that at least Stage Level states (Carlson 1977) allow for frequency adverbials and temporal modification (27).

-

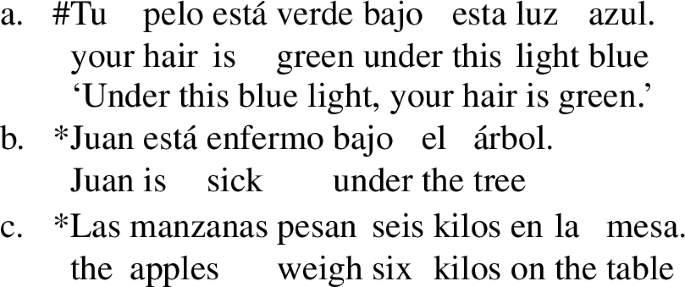

(27)

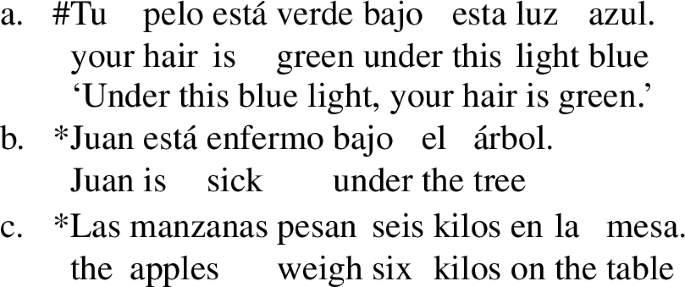

The ability to combine with locative modifiers, in contrast, is surprising for accounts where a negative description denotes a state. Maienborn (2003, 2005) distinguishes between pure or Kimian States, which lack any event variable in her account, and other predicates—dynamic or not—that denote events. Among the relevant tests, she notes that pure states cannot combine with real locative modifiers. They, at most, allow a conditional interpretation of a locative phrase, as in (28a), along the lines of ‘If you are under this blue light, your hair looks green’ (cf. also Rothmayr 2009).

-

(28)

Inhibited eventualities, however, freely allow locative modifiers without a conditional reading:

-

(29)

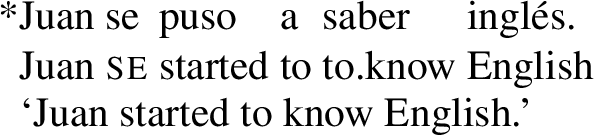

Finally, it can be shown that some auxiliaries that reject states can allow low negation. Like modal periphrases and <empezar a + infinitive>, the inchoative periphrasis <ponerse a + infinitive> allows two positions for negation (30a), (30b).Footnote 14

-

(30)

At the same time, the inchoative periphrasis rejects states (Gómez Torrego 1988:110–111; De Miguel 1999:3030–3039; García Fernández et al. 2006:222–223).

-

(31)

While negative eventualities pattern with events with regards to several properties, they cannot be classified as dynamic events because they also share several properties with stative predicates. This fact has prompted some authors to classify them as states instead (cf. Bennett and Partee 1972; Dowty 1979; Verkuyl 1993; de Swart 1996 and de Swart and Molendijk 1999).

First, inhibited eventualities differ from their positive counterparts, and pattern with states, regarding the (strict) subinterval property: “while processes involve a lower bound on the size of subintervals that are of the same type, states have no such lower bound. [...] If for a certain time interval I it is true that, for example, Eva is standing at the window, sleeping, or the like, this is also true for every subinterval of I.” (Maienborn 2005; for the original formulation that distinguished between telic and atelic predicates, see Bennett and Partee 1972; Dowty 1979; Krifka 1989). Consider the examples in (32). The stative predicate in (32a) does not denote any internal change or dynamic action. As a result, if it is true that the child has a toy for a time interval I, it is also true for any subinterval of I, no matter how small; to put it in intuitive terms, the eventuality ‘to have a toy’ can be verified with any photo showing the child with the toy because every instant included in the time period during which the state holds is an instant where the state holds. In contrast, this does is not true for (32b) in contrast: if we go down to a sufficiently small level of temporal granularity, the event will not be described as ‘running in the park,’ because, in a single instant the child will not be moving:

-

(32)

As noted by de Swart (1996), inhibited eventualities, like states, also meet the strict subinterval property. Regarding this property, inhibited eventualities such as ‘not building houses’ (see (33a)) and ‘not cleaning the floor’ (see (33b)) clearly differ from the corresponding positive predicates, which are dynamic (see (34)):

-

(33)

-

(34)

‘Building houses’ or ‘cleaning the floor’ do not meet the strict subinterval property, as there are intervals short enough that do not involve any proper building or cleaning—that is, single instances without movement or change. Any subinterval of ‘not building houses,’ no matter how small, however, consists of ‘not building houses.’ As a reviewer notes, this test might be considered not strong enough due to its conceptual nature. However, there are other tests that clearly argue in favour of inhibited eventualities possessing stative properties.

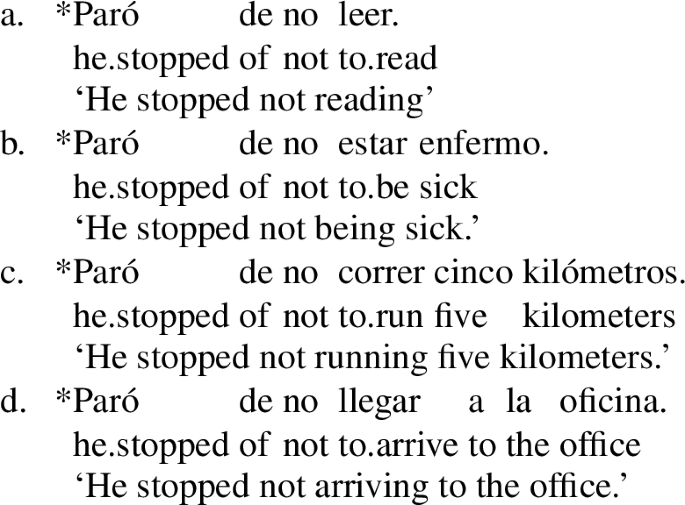

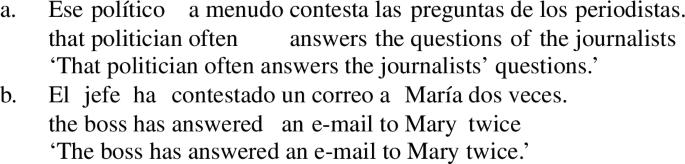

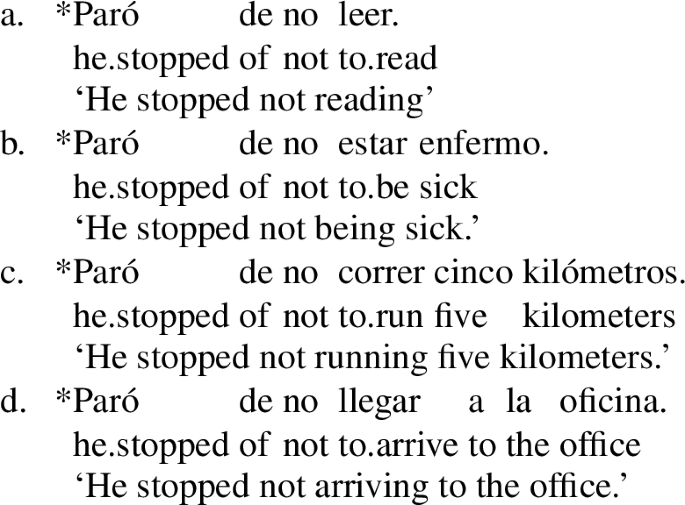

A second test is based on the periphrasis <parar de ‘to stop’ + infinitive>. It combines with dynamic durative events (de Miguel 1999; Marín 2004; Arche 2006 and Marín and McNally 2011), and is therefore compatible with activities (see (35a)) and accomplishments (see (35b)), but rejects states (see (35c)) and achievements (see (35d)) because they are not dynamic or durative, respectively.

-

(35)

Inhibited eventualities reject this periphrasis, regardless of the Aktionsart of the infinitive combining with negation.

-

(36)

The ungrammaticality of (36) indicates that inhibited eventualities are neither activities nor accomplishments, since they are incompatible with parar de. However, it does not allow us to determine whether they behave similarly to states or achievements. Yet, if we take the compatibility of inhibited events with <dejar de ‘to leave of’ + infinitive> into account, we can, nonetheless, conclude that these events pattern with states. The periphrasis is compatible with states (see (37a)), but not with accomplishments (see (37b)) and, crucially, does not reject negative eventualities (see (37c)).

-

(37)

Third, as we already mentioned in Sect. 3.1, inhibited eventualities, in contrast to their positive counterparts, are compatible with temporoaspectual modifiers. It has, in fact, been pointed out in prior literature that negation is a stative operator (Mittwoch 1977 and de Swart and Molendijk 1999, among others) because of the fact that events accept for- and until-phrases in combination with negation.

Mittwoch’s and de Swart and Molendijk’s proposals build on the behaviour of for- and until-phrases. The former are compatible with atelic (see (38a)), but not with telic predicates (see (38b)); the latter can only appear with durative predicates, as is shown by the contrast in (39). Both are allowed by stative verbs (see (40)), and, crucially, become compatible with the predicates in (38b) and (39b) if we introduce negation (see (41)):

-

(38)

-

(39)

-

(40)

-

(41)

The existing proposals explain these contrasts by arguing that negation yields a durative predicate, specifically, a state. Since states are atelic and durative, for- and until-phrases can occur in (41).Footnote 15 Note that the change in the compatibility with temporoaspectual modifiers occurs under the inhibited eventuality reading, but not under the negated event reading involving sentential negation. This is due to the presence of an eventuality in the former, but not in the latter. Consider the following examples:

-

(42)

The presence of for-phrases forces a negative eventuality reading because for-phrases measure the duration of the time period during which an inhibited eventuality takes place. In a negated event, there is no time period during which the event takes place; a non-existent time period cannot have duration. Thus, the association between the for-phrase and the inhibited eventuality reading is intuitive.

3.3 Inhibited eventualities require an initiator

Not every event possesses an inhibited eventuality counterpart in Spanish. (43b) could be expected to mean that the speaker saw that the milk did not boil, for instance when reporting why the custard did not come out right. It is ungrammatical, however.

-

(43)

In this section, we will argue that (43b) is ungrammatical because the infinitive describes an eventuality lacking an agent or causer. We furthermore argue that the inhibited eventuality interpretation is only licensed with predicates in which the entity denoted by the subject has the teleological capacity to initiate the event. For explicitness, we will define this sense of ‘initiator’ as the entity whose properties or behaviour is responsible for the eventuality coming into existence, following Ramchand (2008:33–37). Notice that there is no implication that an initiator is volitional in, or even conscious of, initiating the event. This definition encompasses the traditional notions of volitional agents, nonvolitional causers and instrumental subjects whose facilitating properties allow an event to happen.Footnote 16

If the predicate does not license an initiator, the inhibited eventuality reading is impossible. In (43b), the absence of an inhibited eventuality interpretation is related to the fact that the internal properties of the milk cannot initiate the boiling event.

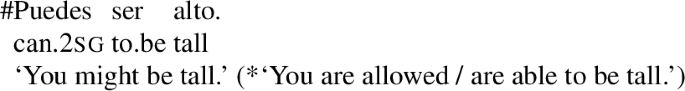

In the following, we will show that this restriction determines whether a predicate can get an inhibited eventuality reading. This can be illustrated through two types of contrasts: (i) with verbs describing events without a controller, the inhibited eventuality readings are illicit; (ii) in verbs alternating between a causative and inchoative reading, the inhibited eventuality reading is restricted to the first.

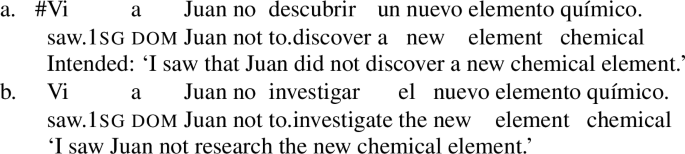

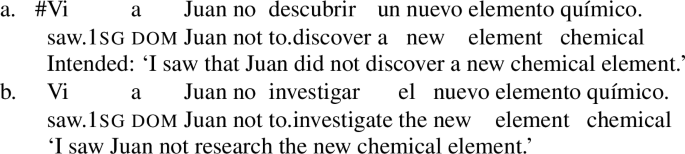

Let us start by showing that predicates denoting uncontrollable events cannot get an inhibited eventuality reading. The evidence comes from ‘accidental discovery’ scenarios. We can agree that discovering a new chemical element is not triggered by the internal properties of the subject, under normal circumstances. Hence, the awkwardness of (44a) vs. (44b):

-

(44)

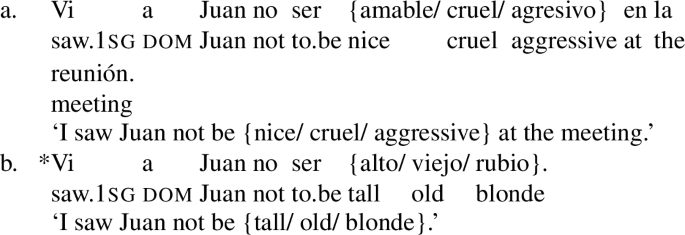

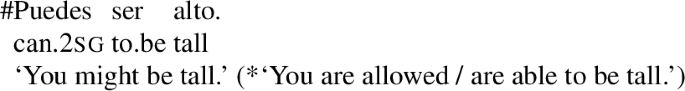

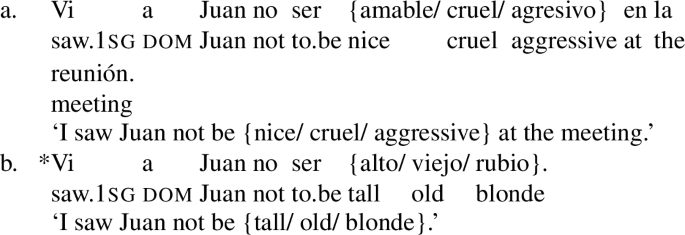

The situation is even clearer with predicates involving copulative verbs. Evaluative adjectives (Stowell 1991; Fernald 1999; Bennis 2000; Geuder 2002; Kertz 2006; Oshima 2009; Landau 2010), such as amable ‘nice’, cruel ‘cruel’, sincero ‘sincere’, atento ‘courteous’, fiel ‘loyal’ or agresivo ‘aggresive’, involve situations controlled by the subject, when they are interpreted as denoting types of human behaviour. Their analysis is controversial (see the references above). Here, however, we are solely interested in their empirical behaviour, which shows that they can trigger an inhibited eventuality reading (see (45a)), unlike adjectives that cannot be interpreted as expressing controlled behaviours, such as alto ‘tall’, verde ‘green’, ancho ‘wide’, viejo ‘old’ or metálico ‘metallic’ (see (45b)).

-

(45)

Consider now predicates alternating between causative and inchoative readings as a second parameter. Ramchand (2008:78, 82–89) differentiates between two types of verbs traditionally considered as non-causative verbs: those containing an initiator, such as arrive, leave or enter, and those lacking one, such as the inchoative versions of melt, break or empty. She differentiates them through a linguistic test: the first class cannot be further causativised, because its members already contain an initiator, while the second class allows for a causative version involving (in English) a silent verbal head introducing the initiator. The contrast in (46), taken from Ramchand (2008:85–86), illustrates this point.

-

(46)

.

-

a.

Alex broke the stick.

-

b.

*Kayleigh arrived Katherine.

-

a.

Moving to Spanish, where we assume the same distinction to apply (see (47)), non-alternating (unaccusative) predicates systematically allow the inhibited eventuality reading (see (48)):

-

(47)

.

-

a.

Alex rompió la rama.

-

b.

*Kayleigh llegó a Katherine.

-

a.

-

(48)

We claim that the inhibited eventuality reading is available with these verbs for the same reason that they cannot be causativised: they already contain an initiator. In contrast, with the following verbs (49)–(51), which allow causativisation, the inhibited eventuality reading is out for the inchoative version and grammatical for the causative one, when an initiator is present.

-

(49)

-

(50)

-

(51)

Consequently, there is evidence that the inhibited eventuality reading is only grammatical when the eventuality is initiated by a subject that, consciously or unconsciously, volitionally or non-volitionally, triggers the event.Footnote 17 Keeping this particular property in mind, and having shown that inhibited eventualities share properties with both events and states, let us move to the analysis.

4 Analysis: Negation above and below existential closure of the event

At this point, we hope to have provided evidence that the reading we call inhibited eventuality is distinct from sentential negation, by means of several syntactic contexts specifically expressing it (Sect. 2) and aspectual and argument structure properties where the reading denotes an eventuality, not a fact (Sect. 3). In this section, we provide an analysis of inhibited eventualities in terms of the scope of negation. Specifically, and similar to previous accounts (Cooper 1997), we argue that the negated eventuality reading involves low negation with a scope restricted to the descriptive properties of the event. Following Ramchand and Svenonius (2014) and Wiltschko (2014), we associate the VP region with a classifying function and leave the specification of the eventuality’s time and world parameters to a higher region. We implement the technical aspects of the analysis within Ramchand’s (2018) proposal.

The section is divided in the following parts. Section 4.1 provides an overview of previous accounts relating the scope of negation to the reading we call inhibited eventuality, frames the problem within accounts based on the claim that the VP level and the temporoaspectual layers constitute two separate domains, and presents Ramchand’s (2018) specific implementation. Section 4.2 presents the analysis, showing, step by step, how the inhibited eventuality reading is obtained, and how it contrasts with the derivation producing sentential negation.

4.1 Two levels for negation in event semantics

We will put forward an analysis of inhibited eventualities as configurations where negation does not scope over the event as an object with time and world parameters, but over the description denoted by the lexical predicate which is conveyed in the event.

An immediate antecedent of the division between the descriptive content of the predicate—the essence of the eventuality—and the assertion that an eventuality, as an object with time and world parameters, exists is found in situational semantics, more specifically in Cooper (1997). Cooper (1997) proposes two levels of meaning; situations are construed as complex entities of the form (52), where s is the situation and σ denotes the infon, which corresponds to the descriptive content exemplified within the situation (Cooper 1997:2). Infons are descriptions of states of affairs or, in other words, (abstract) types of situations, while situations are particular instantiations of infons. The graphic in (52), taken from Cooper (1997), captures these two levels of meaning and, in particular, the proposal that situations tag the infon with temporal and worldly information that particularize the descriptive content provided by the infon, anchoring it to a time and world.

-

(52)

.

Even though we will not base our account on situation semantics, Cooper’s proposal reflects the same type of intuition we will implement. Throughout the extensive literature on situations starting in the early 80s (Barwise 1981, 1988; Barwise and Perry 1983; Barwise and Etchemendy 1987; Kratzer 1989, 2002, 2007; Doron 1990; Gawron and Stanley 1990; Barwise and Cooper 1993; Kamp and Reyle 1993; Cooper 1996, 1997; Ginzburg and Sag 2000; Elbourne 2005; Ginzburg 2005), situations are understood as partial world descriptions defined by two properties: they are particulars that exemplify a state of affairs, and they involve relations and individuals involved in those relations. Depending on which of the two aspects is considered to be more prominent, situations are either taken as substitutes to eventualities or as instantiations of the descriptive content of eventualities. In the first view, situations subsume the properties normally associated with Davidsonian events: as objects instantiating in particular times and worlds relations between entities. This makes the notion of ‘event’ redundant (cf. in particular Kratzer 1989, 2002, 2007).

Cooper exemplifies a second view where situations are particulars exemplifying or instantiating descriptions of states-of-affairs—technically ‘infons,’ although see Przepiórkowski (1999:248–249) for the observation that the time of the entity instantiated in the situation is orthogonal to this theory to some extent—(Récanati 1986/1987; Barwise and Etchemendy 1987; Cooper 1996, 1997). In this proposal, the descriptive content of the situation and the particularisation of that descriptive content in a time and a world are on separate levels.

Treating the infon as a separate domain contained within the situation allows negation to apply at two distinct levels in Cooper’s (1997) proposal. The narrow scope negation produces the reading that had been called ‘negative event’ and has scope over the infon. If this is the case, then the situation is a particular that exemplifies this negative relation: see (53a) in opposition to the negated event reading in (53b), where negation takes wide scope over the situation.Footnote 18

-

(53)

.

Our account follows the same intuition, although we will frame it in Ramchand’s (2018) event semantics in order to avoid multiplying the objects in the ontology by means of a division between situation and eventuality. Specifically, we take the ‘infon’ level in Cooper to correspond to the descriptive content of the eventuality, in a way that we will make explicit immediately. We view the material introduced in the verbal domain as descriptive symbolic objects denoting generalisations about particular events (Ramchand 2018:14). This account shares its spirit with Wiltschko (2014), who argues that the sole function of the verbal domain is to classify the eventualities of the world by their relations between actants, their Aktionsart, and their remaining, speaker identified, cognitive and perceptual properties identified (cf. also Ramchand and Svenonius 2014, where situations and eventualities are distinguished, however).

Those denotative symbolic objects form a vocabulary of primitives used to express argument relations and Aktionsart notions, and provide the eventuality with descriptive content. They do not denote events themselves, but, rather, are used by speakers to convey an event with time and world parameters: an exemplification of the descriptive content with time and world particulars. In Ramchand’s (2018) implementation, a property of the eventuality e is built through a syntactic head Event (Evt). This head takes the conventional content of the lexical items building the predicate (represented as u) and uses it to convey an event which is demonstrated in a performing act of communication d (Henderson 2016; see also Eckhardt’s 2012 Davidsonian event variable).

In our account, the relation between u—specifically, the semantic part of the lexical items, represented as [u] —and e, a standard Davidsonian event with time and world parameters, is of utmost importance. The intuition is that the symbolic objects combined to define predicates do not denote events until they combine with the head Evt at the edge of the verbal domain.

(54) reproduces the denotation of EvtP (Ramchand 2018:16), which is the syntactic head at the edge of the verbal domain, taking any material that has been used to classify the eventuality as its complement.

-

(54)

. [[EvtP]] = λdλe[Utterance(d) & Thδ(d)=u & Convey (d,e)]

Chiefly, this denotation of EvtP captures the intuition that by performing an act of communication d the speaker conveys an eventuality e whose content is described by the symbolic objects represented as u. The theme of the act of communication d is the conventional meaning of u:

-

(55)

. Thδ(d) = u & Convey(d,e) –> [u] (e)

4.1.1 Representations at the symbolic level

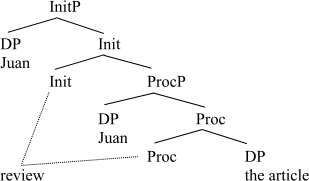

Now consider the representation of the event ‘essence’—in Ramchand’s terms—before its combination with EvtP. We assume Ramchand (2008:39–42), specifically, the existence of three primitives that build descriptive content that convey an event. She argues that the event-structure syntax involves three functional projections:

-

a)

InitiationP (InitP), which specifies the causation subevent

-

b)

ProcessP (ProcP), which introduces change or process

-

c)

ResultP (ResP), which codifies the result state of the event.

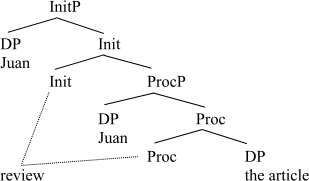

Depending on the predicate, the structure involves all three projections or a subset of them. The hierarchical relation between the three projections in a lexical item identifying all three, as is the case of an achievement like arrive, is shown in (56):

-

(56)

.

(56) shows that the specifier of each projection is occupied by a particular actant whose entailments are determined by the meaning of the head. The initiator of the event is placed in the specifier of the cause projection, that is, in the specifier of InitP. The entity undergoing the change or process denoted by the event is placed in the projection that specifies change or process, ProcP. The entity holding the result state occupies the specifier of ResP. Once the structure is built, and assuming Late Insertion, the structure is identified by specific lexical items that lexicalise the series of heads.

The causative structure of John rolled the ball into the house, for example, involves all three projections, since there is a causative subevent (John initiates the process), a process subevent (a change takes place), and a resultative subevent (the change conveys a result state). The specifier position of InitP is occupied by John, the entity whose behaviour is responsible for the event coming into existence. The specifier positions of ProcP and ResP are occupied by the same DP, the ball. This is due to the fact that the entity denoted by this phrase both undergoes the change and comes to hold the result state of being in the house. The verbal item roll identifies the Init and Proc heads.

-

(57)

.

Let us compare the causative structure in (57) with the inchoative version of the same verb (The ball rolled into the house). (58) also involves a change of state. Crucially, however, it does not have a causative component and the structure, therefore, only contains two projections: ProcP and ResP.

-

(58)

.

This difference in the descriptive content of the event is crucial to our account. Remember that the inhibited eventuality reading is only possible when the eventuality contains an initiatior as part of its descriptive content. Inchoative versions of causative verbs do not contain Init. Therefore, they will not be compatible with an inhibited eventuality reading. We derive this fact from the proposal that the inhibited eventuality reading is obtained by denying the Init event description, as we will immediately see.

The syntactic structure in (56) is associated to combinatorial semantics which only involves the combination of event-descriptive fragments without temporal properties, symbolised by lexical items, at this level. Thus—by hypothesis—it only involves generalised abstractions over eventualities that do not have wordly or temporal properties at this level. (59) represents the semantics of the combination for the verbal predicate in (57).

-

(59)

. λe, e1, e2[e = e1→ e2 & rollinit (e1) & rollproc(e2) & Initiator(e1)=John & Undergoer(e2)=the ball & Path(e2) = into the house)]

The arguments of the verbal predicate are part of the descriptive properties of the event, but the description is not endowed with worldly properties at this level. Let us now see what happens at its combination with EvtP and afterwards.

4.1.2 Creating an event particular from the generalised event description

EvtP is built, at the edge of the verbal phrase and above the event description presented in (56). It deploys the symbolic content of the previously built Init-Proc structure, identified by the lexical item roll, in a performing act of communication d that conveys event e.

-

(60)

.

-

(61)

. λdλe[Utterance(d) & Thδ(d)=rollinit & Convey (d,e) –> [roll]init (e)]

The head, then, builds a property of eventualities with time and world parameters on top of the timeless and worldless generalisations expressed by the material in its complement, which provides the description of that eventuality. At this point, the verbal phrase denotes a Davidsonian event able to possess time and world properties. Following Ramchand (2018), we furthermore assume that the DP corresponding to the initiator of the event moves to spec, EvtP, where it is interpreted as the causer of a full-fledged Davidsonian event with time and world parameters. Argument-wise, this turns EvtP into the equivalent of the VoiceP found in other theories, for example in Harley (2013).

At this point, it has not yet been asserted that an event corresponding to the u description exists, however. In Ramchand (2018:19), the head existentially binding the event variable is Aspect (following Champollion’s 2015 proposal that the eventuality’s existential closure is performed below the sentence level). AspP existentially binds the event variable and expresses a relation f between an eventuality and the anchoring utterance d, corresponding to the spatiotemporal properties of e rooted in d. (62) presents the denotation of AspP according to Ramchand (2018:19).

-

(62)

. [[AspP]] = λfλd∃e[Utterance(d) & [u](e) & f(d)(e)]

Once Asp combines with EvtP, we obtain the following structure

-

(63)

.

At the level of AspP, a speaker, thus, asserts that the eventuality corresponding to the content expressed by u exists.

With this background in mind, let us move to a step by step discussion of how our account differentiates the negated event reading from the inhibited eventuality reading.

4.2 Inhibited eventualities vs. negated events: Two syntactic positions for negation

In short, we claim that the two readings are differentiated by the scope of negation. The inhibited eventuality reading is obtained when negation is introduced below EvtP and, therefore, operates on the descriptive content of the event; the negated event reading—corresponding to the standard sentential negation reading—is produced when negation occupies the standard Negative Phrase position (cf. Laka 1990, with negation being an instantiation of sentential polarity) above AspP, therefore denying the existence of an eventuality. Schematically, (64a) corresponds to the negated event reading; the negative operator, positioned above AspP, takes scope over the existential closure of the situational variable. (64b), in contrast, corresponds to the inhibited eventuality reading.

-

(64)

.

Let us proceed to show step by step how the two readings are derived, from these two derivations. Take (65), with its two interpretations, as the relevant example.

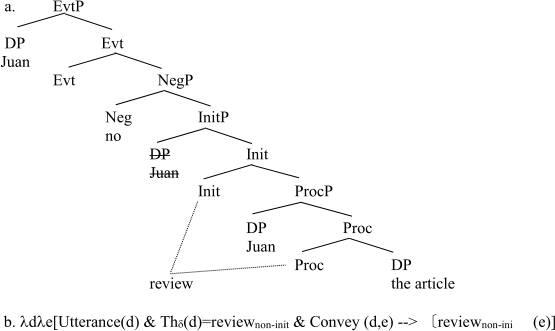

-

(65)

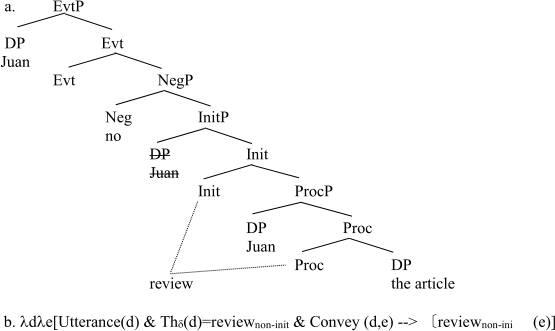

The derivation for both readings will be identical up to InitP, that is, identical in what refers to the symbolic units that combine to define the actant relations and Aktionsart of the event description. The event description ‘Juan reviews the article’ contains two Aktionsart heads: Init and Proc. Init introduces the external argument, Juan, who initiates the event of reviewing an article. Proc provides the dynamic part of the event. Following Ramchand (2008), the complement of the Proc head is ‘the article,’ which measures the development of the event as a bounded path. As specifier of ProcP, Juan receives undergoer entailments as the subject of the article-reviewing process. (66) presents the syntactic structure, and (67) presents the semantic denotation of this event description that has not yet become an event particular with time and world parameters.

-

(66)

.

-

(67)

. λe, e1, e2[e = e1→ e2 & reviewinit (e1) & reviewproc(e2) & Initiator(e1)= Juan & Undergoer(e2)=Juan & Path(e2)= the article]

The inhibited eventuality reading and the negated event reading begin to differ at the next derivational step. Let us first present the negated event reading, ‘It was not the case that Juan kissed the bride,’ with sentential negation.

In this reading, EvtP is merged over InitP, and the initiator DP is moved to the specifier of EvtP in the next derivational step. This results in the entailment that the event is conveyed in an act of communication whose theme is the semantic content of the items up to InitP. The semantic formula is presented in (68b).

-

(68)

.

In the next step, AspP is introduced and the eventuality is existentially bound.

-

(69)

.

At this point, Asp has created a property of spatiotemporal properties of the event, allowing for the introduction of modal, aspectual and temporal modifiers, which we ignore here. Crucially, however, negation is introduced above TP within the Negative Phrase NegP. The negation, thus, scopes over the existential operator and denies the existence of the event corresponding to the description below EvtP.

-

(70)

.

Thus, the sentential negation reading is obtained by denying the existence of an event corresponding to the description provided by the verbal predicate, as it is standardly assumed. Now consider the inhibited eventuality reading. The crucial difference consists of the fact that negation is introduced immediately above InitP, and thus is merged in the structure before EvtP in this case. (71) reproduces this step.

-

(71)

.

Note that the negation in this configuration operates over the head Init, which expresses a cause relation, reversing the cause relation, which, in turn, becomes an inhibition relation; that is, the logical opposite of causing an event is to inhibit the event. Denying the head Init, then, produces the entailment that the Init subevent, identified by the lexical item review, is not an initiating reviewing-event, but an inhibiting reviewing-event. This produces the following event description.

-

(72)

. λe, e1, e2[e = e1 inhibit e2 & reviewnon-init (e1) & reviewproc(e2) & Initiator(e1)=Juan & Undergoer(e2)=Juan & Path(e2)= the article]

At this point, the description of the event denotes a situation where the agent, which in principle possesses the capacity to initiate a process, instead inhibits that process in this case. Consequently, no process of reviewing the article undertaken by Juan takes place.

The following step introduces EvtP and creates a performing act of communication that conveys the eventuality described as the inhibition of article-reviewing undertaken by Juan.

-

(73)

.

AspP is built at the following step and the event described as the inhibition of the article-reviewing by Juan becomes existentially bound.

-

(74)

.

Consequently, the speaker asserts that a particular event exists and occupies a particular extension in time. That event corresponds to a negative description where the cause relation has been denied and turned into an inhibition relation. This triggers the interpretation that the argument in spec, DP corresponds to the entity that controls the inhibition of an event. In this sense, negative event descriptions—which we argue to underlie the so-called ‘negative event’ interpretation—are reminiscent of events such as hinder or prevent (cf. also Wolff 2007; Wolff and Shepard 2013), that is, what Talmy (1988) called ‘blocking events’: events where the agent’s force dynamic is manifested through the inhibition of an otherwise expected change or action.

The reading that has been described as ‘negative event,’ then, simply involves negating the cause relation established by Init. Thus, any event description which lacks the head Init will not be able to trigger the so-called ‘negative event reading’—a misnomer representing what should be interpreted as a negative description conveyed by an event that is asserted to exist.

This explains the intuitive truth conditions of Juan no revisó el artículo ‘Juan did not review the article’ in the inhibited eventuality reading. It is enough to satisfy the eventuality description ‘not review the article,’ that Juan did not initiate the process of reviewing the article, even though he had the capacity to be its initiator. It is, for instance, not stated that no article-reviewing events by other agents took place. Other participants might have initiated the reviewing event; we just state that Juan was not one of them. Remember that the notion of initiator can—but does not need to—have volitional entailments. This demonstrates, furthermore, that the inhibited eventuality still holds in both situations where Juan might have consciously chosen not to review the article and in situations where he might have failed to do so unintentionally.Footnote 19

Empirically, InitP is the subevent component that must be under the scope of negation, because only predicates containing it can participate in the inhibited eventuality reading (Sect. 3.3). Although we cannot think of a general principle that forcefully restricts negation within the event description to InitP, there is an intuitively plausible reason for this restriction. Imagine that ProcP was being negated, instead. ProcP does not denote a stative relation of causation, but a dynamic activity that develops through time. The resulting denotation would be truthful in any context where a type of change or activity that is not the one denoted by the denied Proc takes place; negating the process of running would, hence, be truthful in any context where a process of walking, eating, reading, sleeping, and so on is described. Negating Proc would therefore have truth conditions too weak to result in an informative situation altogether. Only Init, whose only content is the causative relation, produces an all-or-nothing type of interpretation that results in an informationally valid utterance in combination with negation.Footnote 20

This proposal accounts for the syntactic and semantic properties of inhibited eventualities presented in Sects. 2 and 3. In the next section, we will discuss the aspectual properties presented in Sect. 3 in more detail, while we will concentrate on the syntactic properties noted in Sect. 2, below. Remember that, in the presence of auxiliary verbs, the inhibited eventuality reading can be distinguished from the negated event reading by means of noting the syntactic position of the negation. Our analysis expects this, because negation is introduced at different heights in each of the two readings; namely above and below AspP, where existential closure of the event takes place. The inhibited eventuality reading is related to syntactic low negation (see (75a) and (76a)) because negation must be introduced below AspP to obtain this reading and all modal and temporoaspectual auxiliaries are introduced above AspP (see, among others, Eide 2006). The negated event reading requires high negation above the auxiliary (see (75b) and (76b)) because the negative phrase that yields the reading is introduced above TP.Footnote 21 We even correctly predict that the two negations can co-occur, in which case one denies the existence of an event corresponding to an inhibit relation (77).

-

(75)

-

(76)

-

(77)

The two positions for negation further compositionally explain the interpretation of each combination. In the case of the modal, the subject has the possibility to participate in a negative event when negation is below the deontic modal (roughly, ◊¬E); when negation is introduced above the deontic modal (¬◊E), the possibility to participate in an event is denied. It is, of course, also possible to have double negation (no puedes no pagar ‘you cannot not pay’), in which case it is denied that there is the possibility to participate in an inhibited eventuality (¬◊¬E).

Here, we end our presentation of the core analysis and how it accounts for the argument restriction of inhibited events (Sect. 3.3) and of the two positions of negation, each one related to one reading (Sect. 2). In the next section we will give a detailed account for how this approach explains the aspectual properties of inhibited eventualities (Sect. 3.1. and Sect. 3.2).

5 How the properties of inhibited eventualities are explained

In this section, we discuss how the different properties of inhibited eventualities, presented in Sect. 3, are explained by our analysis. We divide the discussion of its properties into three sections: the fact that inhibited eventualities have duration, frequency and other event properties follows from their being negative descriptions conveying an eventuality whose existence is asserted (Sect. 5.1), their eventive properties follow from the negative description involving a Proc head (Sect. 5.2), and their stative properties follow from the inhibition of the event (Sect. 5.3).

Before we proceed, it is important to remind the reader that the diagnostics presented in Sect. 3 are formulated within a system where two different domains exist: the lower domain combines symbolic elements producing a description that does not convey an event until it transitions to the higher domain. Thus, the temporal properties of the event are not defined until interaction with the second domain. The diagnostic tests in Sect. 3.1 that we applied in order to distinguish between facts and eventualities, diagnose properties of the higher domain where the symbolic objects convey eventualities with time and world parameters. In contrast, the tests that we used to differentiate between their event and state properties (Sect. 3.2) apply to properties defined in the symbolic area of the lower domain.

5.1 Inhibited eventuality readings assert the existence of an event

In our account, an inhibited eventuality conveys an event which is existentially bound and not denied. In other words, in the inhibited eventuality reading an eventuality conveyed by the negative description exists. We repeat the relevant formulas here for convenience; (78a) corresponds to the negated event reading and (78b) to the inhibited eventuality reading.

-

(78)

.

-

a.

λfλd¬∃e[Utterance(d) & [uinit] (e) & f(d)(e)]

-

b.

λfλd∃e[Utterance(d) & [unon-init] (e) & f(d)(e)]

-

a.

In (78a), the negated event reading involves negating that there is an event corresponding to the description denoted at the lower domain; in (78b) it is asserted that there is an event that conveys the negative description built in the lower domain. Remember that time and world parameters are introduced only at the point when the symbols convey the event in Ramchand (2018).

The fact that the inhibited eventuality reading asserts the existence of an eventuality naturally accounts for the properties introduced in Sect. 3.1; namely, the possibility of relative clauses referring back to it, and its compatibility with temporal adverbials and adverbs of frequency and iteration—as well as the existence of negative temporal clauses (cf. footnote 10). Let us explain how these properties follow from our analysis.

Regarding relative clauses, we showed that relative clauses require an eventuality as antecedent (79).

-

(79)

This requirement is due to the fact that the clause refers back to a particular eventuality that exists in a time and world. The proposal that the test is sensitive to the assertion that the eventuality exists, independently of the description that conveys it, is supported by the grammaticality of (80), in case of a state (see (80a)), an activity (see (80b)), an accomplishment (see (80c)) and an achievement (see (80d)). According to Ramchand (2008) and Ramchand and Svenonius (2014), the predicates in (80) share precisely that there is an eventuality corresponding to a particular description; however, they differ regarding their subeventive structures, that is, the description of the eventualities.

-

(80)

Inhibited eventualities assert the existence of an eventuality in a particular time and world; lo que refers back to the eventuality, (see (81)), in parallel fashion to (79).

-

(81)

The compatibility of inhibited eventualities with temporal adverbials is also accounted for by inhibited eventualities asserting the existence of an eventuality. As there is an eventuality in a time and world, temporal adverbials, such as for-phrases, can measure its extension (see (82)).

-

(82)

In parallel fashion, adverbs of frequency and iteration can take scope above the negation in the inhibited eventuality reading, as illustrated in (17) and repeated in (83). This is predicted under our analysis: if the adverbs count instances of an eventuality, the inhibited eventuality can occur a number of times. (83a), thus, denotes that the eventuality in which the politician does not initiate the process of answering the journalist’s questions occurs often (see (84a)). (83b) expresses that the eventuality that conveys the negative description has occurred twice (see (84b)).Footnote 22

-

(83)

-

(84)

.

-

a.

λfλd∃e[Utterance(d) & [answernon-init] (e) & f(d)(e) & often(e)]

-

b.

λfλd∃e[Utterance(d) & [answernon-init](e) & f(d)(e) & twice(e)]

-

a.

We now shift our attention to the eventive properties of inhibited eventualities.

5.2 The event properties of inhibited eventualities

We have seen several pieces of evidence showing that the inhibited eventuality reading patterns with events. Our proposal is that these properties naturally follow from the fact that inhibited eventualities contain Proc. In our account, the inhibited eventuality involves the negation of the symbolic part InitP with the negation not blocking event identification. If the predicate contains ProcP, the e argument of Init identifies with the e argument of Proc, and both are related through an inhibition relation. Like this, inhibited eventualities are differentiated from states. Let us explain how this captures their event properties.

To begin with, we have seen that esto ‘this’ as the subject of suceder ‘happen’ is specialised in taking events as antecedent. We assume that suceder ‘happen’ imposes the condition that it refers to an event containing a Proc subevent on its subject. In this case, esto satisfies this condition because it refers to an inhibited eventuality. Through event identification, the e corresponding to esto ‘this’ contains the processual information carried by Proc-e.

-

(85)

That inhibited eventualities involve Proc also explains that the do-so anaphor can refer back to them. This is an expected result, assuming that the structure is sensitive to the presence of the e argument of Proc and assuming event identification.

-

(86)

The third property introduced in order to support the claim that inhibited eventualities pattern with events was the possibility of infinitive negative events being embedded under perception verbs (see (87)), which select events as opposed to states.

-

(87)

For explicitness, we assume that ver ‘see’, in its perception interpretation, selects e<proc> as its complement.Footnote 23 Given that the inhibited eventuality denotes an e that contains a Proc e, a perception verb can select inhibited events as its internal argument.

Yet another property of events, in opposition to states, is that the former can be located in space. Given that the inhibited eventuality is an eventuality still containing Proc as long as the corresponding positive predicate contains it, this result is expected. (88) presents the denotation of the sentence María no besó a la novia en la cocina ‘María did not kiss the bride in the kitchen’ in the relevant reading: that the event corresponding to the inhibition of the kissing event took place in the kitchen. Note that e, which contains Proc, is available as an argument of the locative modifier in (88).

-

(88)

. λfλd∃e[Utterance(d) & [kissnon-init| (e) & f(d)(e) & in-the-kitchen(e)]

Finally, the presence of Proc in inhibited eventualities also captures their compatibility with <ponerse a + infinitive>, which rejects states (see (89)). Assuming that this periphrasis requires a predicate containing a Proc e, this requirement is satisfied by inhibited eventuality readings. As a result, (89a) is grammatical.

-

(89)

5.3 Consequences of the initiation component being denied: Stative properties

Section 3.2 shows that even though inhibited eventualities behave like events regarding many properties, they pattern with states regarding the subinterval property, their (in)compatibility with periphrases such as <parar de + infinitive>, and the distribution of durative modifiers. In this subsection, we will show how the inhibition of the initiation relation accounts for these stative properties.

Before we proceed, it is important to point out that given the proposed position for negation in the inhibited eventuality reading—within the domain where the description of the event, including its Aktionsart properties, is built—it is plausible that negation can be conceived as an operator over the aspectual properties of the eventuality, as de Swart (1993) and de Swart and Molendijk (1999) suggest. While our proposal is compatible with approaches where negation can alter the aspectual properties of the eventuality, that role should be restricted to syntactic configurations where the negative operator is within the verbal domain, in our opinion.

Let us start by discussing the strict subinterval condition, which is satisfied by inhibited eventualities. Note, again, that any subinterval of the negative description ‘Marta does not initiate the event of studying’ is of the same type.

-

(90)

This is due to the fact that the dynamic change denoted by Proc—or its associated result—is never effectively triggered. Remember that the inhibited eventuality reading negates the initiation relation, reversing it to an inhibition relation. If initiation is negated, the process is not triggered. By transitivity, there is no result, since a causal chain between these components exists (91). In other words, the inhibition of an event implies that both the process and the result are inhibited.

-

(91)

.

-

a.

Positive description

e= e1→ (e2→ e3 ): [initiate-P (e1 ) & process-P(e2) & result-P(e3)]

-

b.

Negative description

e= e1 inhibits e2 (no causation of e3): [inhibit-P (e1) & process-P(e2) & result-P(e3)]

-

a.

Even if the predicate denotes a change or an action in its positive counterpart, there would, therefore, not be any change in the properties described during the time period when the eventuality holds, because the change or action is inhibited. As a result, any instant contained inside the time period will satisfy the description of the inhibited eventuality.

Given that the change or action is inhibited, inhibited eventualities lack dynamicity. In other words, while they involve a Proc and the e argument of Init identifies with the e argument of Proc, the inhibition of Proc implies a lack of dynamicity, which lead to the stative properties of inhibited eventualities. Thus the inability of inhibited eventualities to combine with <parar de + infinitive> is also explained by the construction’s requirement for dynamic predicates.

-

(92)

We predict that any Spanish auxiliary requiring dynamic events as the auxiliated predicate will reject combining with inhibited eventualities. This prediction is borne out, as shown by the contrast in (93) and (94) (see Fábregas and González Rodríguez 2019). (93a) and (93b) illustrate that the periphrasis <andar + gerund> allows eventive predicates but rejects states. As our proposal predicts, the construction also is incompatible with inhibited predicates (93c). The same pattern is found regarding <ir + gerund> (see (94)).

-

(93)

-

(94)

The absence of dynamicity, furthermore, explains why inhibited eventualities cannot combine with adverbs modifying the way in which the process takes place, such as rápidamente ‘fast’ and lentamente ‘slow’. Notice that (95) is ungrammatical unless negation takes narrow scope over these adverbs: once the initiation component is negated, the process is also inhibited.

-

(95)

Inhibited eventualities allow for subject-oriented modification, because the subject is still an external argument—perhaps, even a volitional agent—within the causative relation that is denied. Someone can, for instance, act cunningly in not initiating an event, provided he or she consciously controls the non-initiation of that event. Imagine that María wants to make sure that nobody thinks that she is having an affair with the bridegroom and cunningly decides not to initiate the event of kissing him.

-

(96)

Subject-oriented adverbial modification is possible to the extent that the subject can control the non-initiation of the event.

Finally, let us explain how our proposal accounts for the distribution of durative modifiers and, in particular, for the compatibility between telic predicates and for-phrases if negation is introduced, as shown by the contrast in (38b) and (41a), repeated here in (97).

-

(97)

As shown in Sect. 3.2, these durative modifiers force the inhibited eventuality reading. Under this reading, the initiation component is denied, however, which means that the process is not triggered. By transitivity, there is no result. The inhibition of the change or action necessarily conveys the lack of telicity. This follows from the assertion that telicity arises when Proc takes as its complement Resp or a bounded path in Ramchand’s (2008) system. In (97), these components are inhibited (see (91)). At the Asp level an eventuality described as the inhibition of the reading and arriving events, that is, an atelic event description, is existentially bound. Thus, the durative modifier is required by this type of description (durante una hora ‘for one hour’).

-

(98)

. λfλd∃e[Utterance(d) & [readnon-init] (e) & f(d)(e) & for-one-hour(e)]

6 Conclusions

In this article, we have provided evidence that the so-called ‘negative event’ reading proposed in the literature should be analysed as involving inhibited eventualities. Inhibited eventualities are eventualities corresponding to negative event descriptions whose existence is asserted. We have identified a number of contexts where sentences with negation must have an inhibited eventuality reading, showing that there is a syntactic difference in the position occupied by negation in the inhibited eventuality reading in contrast to the sentential negation reading. We have also shown that inhibited eventualities possess their own aspectual properties that contrast with positive eventualities and that they can only be built over verbs containing an initiation component. If the predicate does not involve an initiation component, the inhibited eventuality reading is impossible.

We have argued that, while sentential negation involves denying that there is an eventuality, the inhibited eventuality reading asserts that there is an event corresponding to a negative description where negation denies the causal link between initiation and process, turning it into an inhibition relation. This explains that an otherwise dynamic event description becomes a non-dynamic eventuality with crucial stative properties.

Our analysis does not need to propose two kinds of negation. Rather, there are two positions in the spine of the clause where negation can be merged; each one takes scope over distinct items, by pure syntactic constituency. While the negated event reading involves negation scoping above the existential closure of the event, the inhibited eventuality reading involves negation composing a negative description that conveys an event at the EvtP level whose existence in a time and world is asserted at the Asp level. With regard to the argument structure restrictions of inhibited eventualities, having an initiation component is necessary because negation refutes the causative subevent expressed by Init.

There are several open questions raised by this novel view of inhibited eventualities. Perhaps the most central one among them concerns the nature of the negative phrase. It has always been considered a puzzling fact of negation that it seems to be a functional head that—unlike tense or determiner—does not have a unique, designated position in the spine of the clause, or, for that matter, in the extended projection of one single category. Our proposal puts this problem in the centre, as two negative phrases can simultaneously be present in the same clausal spine. At this point, we have nothing but speculations, but a suggestive future avenue of research would be to explore the idea that there are no designated negative phrases in UG and particular grammars use other kinds of projections, such as FinP or InitP, to introduce polarity markers, such as the negative adverbial no. We are in no position, however, to make claims about this matter here. We hope to, at least, have been able to show that negative expressions can refer to eventualities and that their syntactico-semantic properties can be formalised in a parsimonious way.

Notes

Unless otherwise noted, the data in this paper were elicited from 25 native speakers whose intuitions are reported to belong to different varieties of European Spanish. Namely, they stem from Andalucía, Asturias, Catalunya, Castilla La Mancha, Castilla y León, Madrid and the Basque Country. Their intuitions have, additionally, been checked with two speakers from Perú, and one speaker from México, but sufficient data about Latin American varieties of Spanish is lacking.

It is of course clear that there are pragmatic conditions on the felicitousness of this type of perception report. There are many instances of María not kissing the bride where the utterance in (1) is not felicitous—for instance, when María is sleeping at her place. This article will abstract away from the pragmatic conditions, however, instead concentrating on the syntactic and semantic conditions of sentences such as (1). As we will see in Sect. 3.3, there are argument structure restrictions on inhibited eventualities that have no obvious explanation in pragmatic terms.

See Cooper (1997:12–13) on the claim that some structures that license the inhibited event reading in English do not produce grammatical results in Swedish, for instance.

A note is in order with respect the term ‘eventuality.’ We use this term in the same sense as Bach (1986), that is, to refer to eventive predicates as well as to stative predicates. In Sect. 3.2, we will focus on the aspectual properties of inhibited eventualities and discuss if they denote events (Cooper 1997; Przepiórkowski 1999; Weiser 2008; Arkadiev 2015, 2016) or states, as has been argued by a number of authors (Bennett and Partee 1972; Dowty 1979; Verkuyl 1993; de Swart and Molendijk 1999).

As the careful reader will note, we are appealing to an inhibited eventuality in order to describe the interpretation of (2b) for expository reasons. The same applies throughout this section. For now, it suffices to note that (2a) and (2b) receive different readings. We will provide a more detailed discussion of the semantic object denoted by the reading in (2b) in Sect. 3.

We assume here Picallo’s (1990) proposal that deontic modals are introduced lower than epistemic modals, close enough to the verbal complex so that they can still be sensitive to the argumental entailments of the external argument—hence the informal term ‘root modal’ that is sometimes used in the literature. The picture shown in (3) is also found with the other class of auxiliaries typically classified as root modals, dynamic modals: cf. Juan sabe no meterse en líos ‘lit. Juan knows not to.get into trouble, Juan knows how not to get into trouble.’

We will not discuss some of the arguments offered in the literature because they have been interpreted by other authors as compatible with an analysis in terms of facts. In particular, we exclude the following tests: the anaphoric reference to a negative sentence (see (ia)), the existence of nominal phrases such as the one in (ib), and the possibility of a negative clause having causal efficacy (see (ic)). As noted by Asher (1993), these constructions could involve also facts.

-

(i)

-

(i)