Abstract

We provide an analysis of focus and exhaustive focus in the Grassfields Bantu language Awing. We show that Awing provides an exceptionally clear window into the syntactic properties of exhaustive focus. Our analysis reveals that the Awing particle lə́ (le) realizes a left-peripheral head which, in terms of its syntactic position in the functional sequence, closely corresponds to the Foc(us) head in standard cartographic analyses (e.g., Rizzi 1997). Crucially, however, we show that le is only used if the focus it associates with receives a presuppositional exhaustive (cleft-like) interpretation. Other types of focus are not formally encoded in Awing. In order to reflect this semantic specification of le, we call its syntactic category Exh rather than Foc. Another point of difference from what one would consider a “standard” cartographic Foc head is that the focus associated with le is not realized in its specifier but rather within its complement. More particularly, we argue that le associates with the closest maximal projection it asymmetrically c-commands. The broader theoretical relevance of the present work is at least two-fold. First, our paper offers novel evidence in support of Horvath’s (2010) Strong Modularity Hypothesis for Discourse Features, according to which information structural notions such as focus cannot be represented in narrow syntax as formal features. We argue that the information structure-related movement operations that Awing exhibits can be accounted for by interface considerations, in the spirit of Reinhart (2006). Second, our data support the generality of the so-called closeness requirement on association with focus (Jacobs 1983), which dictates that a focus-sensitive particle be as close to its focus as possible (in terms of c-command). What is of special significance is the fact that Awing exhibits two different avenues to satisfying closeness. The standard one—previously described for German or Vietnamese and witnessed here for the Awing particle tśɔ’ə ‘only’—relies primarily on the flexible attachment of the focus-sensitive particle. The Awing particle le, in contrast, is syntactically rigid. For that reason, the satisfaction of closeness relies solely on the flexibility of other syntactic constituents.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

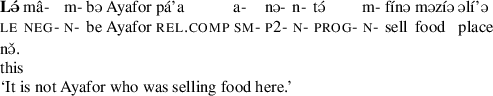

The Grassfields Bantu language Awing marks exhaustive focus by the morphological marker lə́ (henceforth referred to by the gloss le), which precedes the in-situ focused expression, as illustrated in (1). The translation suggests that sentences with le roughly correspond to clefts in English. The sentence in (1) does not represent a general focus-marking strategy: it can be used, for instance, in a correction setting (saying that Ayafor went to the house rather than, say, to school), but not as an answer to a simple wh-question (‘Where did Ayafor go with his money?’).Footnote 1

-

(1)

The sentence in (1) is a prototypical example of how the le particle is used: it immediately precedes the focused constituent. Indeed, if nɨ́ ŋkáp Ʒíə̀ ‘with his money’ is exhaustively focused, it is that constituent that the le particle precedes, as shown in (2).

-

(2)

From this state of affairs, it is tempting to jump to the conclusion that le is syntactically attached (adjoined) to the focus. Yet, once subjects are considered, this simple and perhaps appealing generalization breaks down. In particular, if the subject is exhaustively focused, le occurs pre-verbally, as illustrated in (3). Three further differences are notable: (i) the postverbal position of the subject, (ii) the lack of the subject marker, and (iii) verb doubling.

-

(3)

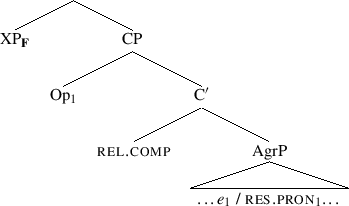

We argue that the puzzling positioning characteristics of the le particle in Awing receives a natural and unified explanation if one analyzes le as the realization of a left-peripheral functional head Exh, which appears between T and Agr. More specifically, Exh selects a TP, and the ExhP it projects can in turn be selected by Agr. The focused constituent with which le associates is located within the TP. The proposed configuration is schematically illustrated in (4).

-

(4)

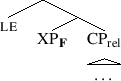

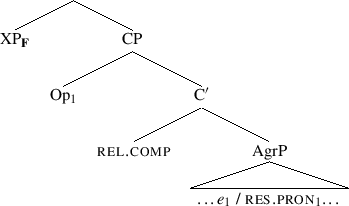

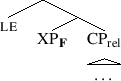

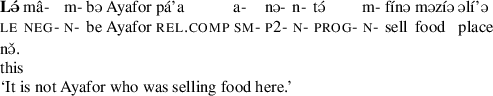

Before we move on, we should point out that Awing has an alternative strategy of exhaustive focus marking, what we will call the biclausal strategy (i.e., essentially a cleft construction). A biclausal alternative to the monoclausal (1) is illustrated in (5). Here, the combination of le and the focused constituent are placed sentence-initially and are followed by a relative-clause-like structure with a gap (or a resumptive pronoun) in place of the focused expression.

-

(5)

We will argue that the analysis sketched in (4) provides an adequate account of the biclausal strategy, despite the apparent absence of any (extended) verbal projections to which le could attach.

Our paper is primarily devoted to a detailed analysis of the morphosyntax of exhaustive focus in Awing. This entails a careful description of various relevant aspects of the Awing grammar, especially because Awing is understudied and its grammatical properties do not always neatly fit one’s expectations. In order to keep the discussion coherent, we cannot do full justice to the many theoretically relevant issues raised by our discussion, issues such as verb doubling, subject–verb (or subject–object) inversion, or the immediately-after-the-verb (IAV) position for focus. While these issues are briefly discussed, we believe that taking a more pronounced comparative and cross-linguistic perspective of them would make the paper too digressive and long. There is one issue, however, that merits closer discussion because it is of particular importance and generality: the issue of the relation between syntax and information structure.

The past twenty years have witnessed a lively discussion concerning how exactly syntax and information structure are related. On the one hand, the influential work of Rizzi (1997) kick-started the so-called cartographic program for analyzing syntactic manifestations of information structure.Footnote 2 Within this program, information structure properties of constituents are fully integrated into narrow syntax, being embodied in relations (esp. Spec-Head) with devoted left-peripheral heads like Foc(us) or Top(ic). Syntactic movement is then utilized to yield the “feature checking” configurations required by information structure. On the opposite side of the spectrum stands the seminal work of Reinhart (1995, 1997, 2006), who argued that information structural notions such as focus are peripheral to syntax. She maintained that focus is related to prosody and that the function of “focus-related” syntactic movement (e.g., scrambling in Dutch) is to yield a configuration in which nuclear stress can be applied without violating the so-called stress-focus correspondence. Let us refer to these approaches to the syntax–information structure interface as “direct” and “indirect,” respectively.

The competing approaches have been explicitly contrasted in a series of papers by Horvath (2000, 2005, 2007, 2010), a proponent of the indirect approach (albeit not a prosody-based one).Footnote 3 Horvath argues that what was traditionally conceived of as “focus movement” in Hungarian, i.e., movement to the specifier of a functional projection directly involved in focus licensing (e.g., Brody 1995; Horvath 1995), should rather be analyzed as movement associated with the semantic (not information structural) process of exhaustive identification (a notion that goes back to Kenesei 1986).Footnote 4 For example, the movement of Jánost in (6) (and the accompanying movement of the verb hívták, crossing the particle meg) gives rise to the inference that János is the only person who got invited. Using a slightly more technical formulation, the movement plays a role in the exhaustive identification of the entity (or entities) in the extension of the background (the set of entities that got invited). Crucially, Horvath argues that it holds that (i) the displaced constituent need not be focused at all (as long as it is interpreted exhaustively), and (ii) only a proper subset of focused constituents in Hungarian undergo this type of movement (non-exhaustively interpreted foci stay in situ).

-

(6)

Based on facts like these, Horvath proposes an analysis where the cartographic Foc(us) head is “replaced” by what she labels an EI head (abbreviating Exhaustive Identification). More generally, an information structure-related head is replaced by a head relevant for semantic interpretation (the computation of truth-conditions and presuppositions). Horvath (2010) then generalizes this idea by formulating the hypothesis in (7).

-

(7)

. The Strong Modularity Hypothesis for Discourse Features

No information structure notions—i.e., purely discourse-related notions—can be encoded in the grammar as formal features; hence no “discourse-related features” are present in the syntactic derivation. They are available only outside the CHL [the computational system of human language ≈ narrow syntax]. (Horvath 2010:1349)

The present paper can be seen as providing further support to this modularity hypothesis. The empirical evidence can be summarized as follows. First, we will show that Awing exhibits no formal encoding of focus whatsoever and as such, the language provides no empirical justification for postulating a formal focus feature (see Sect. 3). Second, our analysis of the particle le reveals that it does not encode focus but rather exhaustive identification (see Sect. 4.5), analogously to the pertinent movement operation in Hungarian. Third, despite the fact that Awing exhibits information structure-related movements, esp. a movement “out of focus” (but arguably also a movement “into focus”), we will argue that these syntactic operations should, in the spirit of Reinhart’s work, be perceived as motivated by interface requirements, rather than by the requirements of narrow syntax (Sect. 4.4).

Despite the absence of formal encoding of focus, the distribution of focus is grammatically constrained in Awing once it associates with le. In particular, we will argue that the focused constituent must be as close to le as possible, where closeness is defined in terms of asymmetric c-command.Footnote 5 This suggests that some elementary grammatical encoding of focus is necessary in Awing, after all. We characterize this encoding in terms of the classical notion of an F-marker (Jackendoff 1972; Rooth 1992), which we believe to be substantially different from a formal focus feature (see the discussion in Sect. 4.3).Footnote 6 Despite the limited distribution of focus associated with le, it remains the case that there is no dedicated focus position in Awing. Associated foci can, in principle, appear anywhere in the structure, as long as they satisfy the closeness requirement.

Finally, there is a sense in which our work provides evidence supporting the cartographic program, albeit with an important proviso. In particular, Awing morphosyntax affords some striking evidence showing that the particle le has a fixed position in the functional domain of the Awing clause. The facts are naturally captured by the assumption that le spells out a functional head (which we call Exh) strictly placed between Agr and T. This position roughly corresponds to the position usually attributed to the left-peripheral Foc head.Footnote 7 If Horvath’s reanalysis of Foc in terms of a head encoding exhaustive identification is on the right track, i.e., if Foc and Exh (or Horvath’s EI) are in fact one and the same head, then the Awing facts presented in this paper can be perceived as further evidence for the reality of a functional head like Foc. The important proviso is that this head does not encode focus but merely associates with focus.Footnote 8

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 provides some background on the Awing language, paying special attention to the basic word order and the verbal morphology. Section 3 concentrates on focus marking in Awing. We show that focus as such (in the sense of Rooth 1985, 1992) typically receives no formal encoding at all—irrespective of whether the focus is “free” (as in answers to wh-questions) or “bound” (when associated with focus-sensitive particles ‘also’ and ‘only’) and irrespective of whether it concerns a subject, an object, or an adjunct (the only exception being verb focus associated with ‘only’). Section 4 spells out the core proposal, namely that le is a realization of a left-peripheral head Exh (located between Agr and T), which associates with the closest following maximal projection, and semantically contributes presupposed exhaustivity. Section 5 summarizes the paper and explores some general consequences of our proposal.

2 Background on Awing

Awing is a Narrow Grassfields Bantu language spoken by about 20,000 native speakers in the Mezam division of the Northwest region of Cameroon.Footnote 9 It belongs to the group of 9 Ngembaic languages, together with, e.g., Mbili (Biloa 2015) or Bafut (Tamanji 2009).Footnote 10 The Ngembaic languages belong to Nka languages, which in turn is a sub-group of Mbam-Nkam languages (another sub-group of which are the Bamileke languages). As far as we are aware, there is no comprehensive grammar of Awing and overall, the linguistic literature on Awing is scarce: the phonology of Awing received attention in Azieshi (1994) and van der Berg (2009); Fominyam (2012) provided a description of the Awing left periphery and Fominyam (2015) deals with the syntax of focus and interrogation in Awing.

Like many other (Grassfields) Bantu languages, Awing is an SVO language with a rich agglutinating verbal morphology, a nominal class system, and lexico-grammatical tone. We adopt a number of notational conventions that deserve mentioning. We refrain from glossing noun classes, as they are in no way essential to the present contribution. Our glossing of the verbal complex, on the other hand, is very detailed. We consistently distinguish between prefixes (x-), suffixes (-x), and free morphemes (x). We are aware that the affixal vs. free nature of some verbal morphemes might be a controversial issue. The decisive criteria for us are (i) the fixed relative position to the verb and (ii) its indivisibility from the verb. As for tone, Awing has four tones: falling (à), rising (á), fall-rising (ǎ), and rise-falling (â). For the sake of simplicity, we leave the falling tone unmarked.

2.1 Basic word order

The examples in (8) illustrate the basic sentential form in Awing: an intransitive unergative sentence in (8a), an intransitive unaccusative sentence in (8b), and transitive sentences in (8c)–(8e). We see that the word order is consistently SV and SVO.

-

(8)

There are no strictly ditransitive sentences in Awing in the sense that the indirect object is always introduced by a preposition, even if it is pronominal, as shown in (9). The example also shows that if adjuncts are present, they are located after the direct and indirect object.

-

(9)

Awing exhibits various word order alternations, i.e., deviations from the canonical SV(O) orders. Some will be discussed and analyzed below. We assume that word order alternations are derived by interface-driven syntactic movements.

2.2 Verbal morphology

Awing verbal morphology deserves extra attention because it plays a crucial role in our argumentation. The morphology of the Awing finite verb is templatic. The verb takes at most one suffix and up to four types of prefixes, schematically summarized in (10), using standard syntactic categories to represent them (the asterisk on Asp- indicates that more aspect prefixes can be present at once). We consider the functional morphemes affixes (rather than free morphemes) because in general, (i) they have a fixed position with respect to the verb and with respect to each other and (ii) no constituent can be placed between the verb and the affixes or between any two of the affixes.Footnote 11 A particular example of the template in (10) is given in (11). The correspondence between the prefixes in (11) and the morphosyntactic categories in (10) should be self-explanatory (see fn. 1 for the list of abbreviations); let us just make clear that we take the subject marker (sm-) to be of category Agr-.

-

(10)

. Agr- T- Neg- Asp-* V -v

-

(11)

None of the affixes is a necessary component of the verb. As illustrated in (12a), a finite verb can well appear in its bare stem form, provided that it delivers the intended meaning. Dropping agreement (subject marker) is only an option, however, if the subject is overtly realized; see (12b). We further note that the affixes are not contingent on one another; for instance, T- can appear without Asp- and Asp- without T-, as illustrated in (12c) and in (12d), respectively. (We will get to the prefix m-, glossed as n-, at the end of this section.)

-

(12)

Each category has at most one affix exponent at a time (for instance, multiple little -v suffixes or multiple Neg- prefixes are disallowed), the only systematic exception being Asp-. Example (13) illustrates this by combining the progressive and habitual aspect within one verbal complex.

-

(13)

The Asp- slot hosts not only canonical aspectual markers (such as progressive or perfective), but also what one could call “light adverbs,” in particular kə́- ‘also’, pɨ- ‘again’, zaŋkə̂- ‘quickly’, and po’nə- ‘slowly’. When they appear together, they do so in a strict order, which means that the Asp- slot should in principle be further divided into subslots, as shown in (14). For the purpose of illustration, we provide the two examples in (15).

-

(14)

. Asp- ≈ also- again- prog- hab- quickly-/slowly-

-

(15)

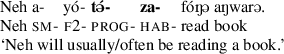

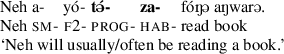

There are two negation strategies in Awing: plain negation and discontinuous negation. There is no clearly discernible semantic difference between these two strategies. The plain negation, illustrated in (16a), involves the prefix mâ-. The discontinuous negation is illustrated in (16b). It involves two negation markers: the prefix kě- (glossed neg1), located in the same templatic position as mâ-, and the morpheme pô (glossed neg2), located in the clause-final position. Discontinuous negation strategies of this sort are fairly common in Bantu languages; see Devos and van der Auwera (2013) (whose glossing convention we follow).

-

(16)

The use of discontinuous negation typically results in a word order alternation: the verb, or more precisely the verbal complex that follows kě (neg1), is realized clause-finally—just before pô (neg2). This is illustrated in (17)—a word order variant of (16b). (Note that we do not write a hyphen after kě because technically, it is not a prefix in this case.) The verb-final order is considered unmarked in discontinuous negation, though the nature of the markedness is difficult to put the finger on.Footnote 12 , Footnote 13

-

(17)

Finally, we would like to draw attention to a special prefix that is sometimes attached to V, Asp, or Neg. The prefix takes the form of a nasal consonant that is homorganic with the first consonant of the category it attaches to, i.e., either n-, m-, or ŋ-. (Awing verbs or prefixes never have a vowel in the onset.) We uniformly gloss it as n-. This prefix sometimes triggers a phonological alternation on the initial consonant of the host category. For instance, attaching n- to the habitual prefix za- (which has a fricative in the onset) results in n-dza- (turning the fricative into an affricate).Footnote 14 The distribution of n- can be characterized as follows: In future-tensed verbal complexes, there is no n- whatsoever; otherwise, any overt prefix of category T, Neg, or Asp triggers the occurrence of n- on the linearly following element. Four illustrative examples are provided below. In (18a), simple present tense is used (unmarked) and the verb fóŋə ‘read’, preceded only by the subject marker a-, occurs in its base form. In (18b), the habitual aspect prefix is used, triggering the prefix n- (realized as m- because of the labiality of the onset) on the verb. In (18c), the aspect prefix is preceded by a past tense prefix, which in turn triggers the occurrence of n- on the aspect prefix (turning the fricative z onset to the affricate dz). Finally, in (18d), the past tense prefix is replaced by a future tense prefix. In effect, no n- prefix is used anywhere (not even on the verb which follows the aspect marker).Footnote 15

-

(18)

3 Focus and focus-sensitive particles in Awing

We have the classical Roothian (1985, 1992) understanding of focus. In Krifka’s (2007) words, focus is the expression that “indicates the presence of alternatives that are relevant for the interpretation of linguistic expressions.” (p. 18) This relatively underspecified semantic notion of focus, taken by Rooth to be expressed by prosodic prominence in English (and many other languages), is compatible with a wide range of uses, including the indication of question–answer congruence, contrast, or association with focus-sensitive particles such as ‘only’ and ‘also’. In what follows, we prepare the ground for our analysis by investigating how (and if at all) focus is formally expressed in Awing. We illustrate three types of focus—answerhood focus, focus associated with ‘only,’ and focus associated with ‘also’—and for each type we consider four types of focused expressions: direct objects, subjects, verb phrases, and (transitive) verbs. Postverbal constituents like adjuncts and various kinds of PPs (including indirect objects) behave on a par with direct objects.Footnote 16 , Footnote 17

3.1 Answerhood focus (“free” focus)

Focus used in answers to wh-questions is considered by many the prototypical kind of focus.Footnote 18 The alternatives indicated by answerhood focus correspond to the possible answers to the wh-question under discussion. In the simple conversation A: Who came? B: John F came, for instance, the focus on John—expressed by prosodic prominence in English—indicates alternative propositions like Mary came, Dave came, Mary and Dave came, etc. These alternative propositions are “relevant for the interpretation” of B’s utterance because they correspond to the possible answers to A’s question. This so-called question–answer congruence contributes to discourse coherence.

In Awing, answerhood focus is not formally encoded: there is no discernible change in prosody, no dedicated syntactic construction, word order alternation, or morphological marking, irrespective of which constituent is in focus. Examples are provided below.Footnote 19 , Footnote 20

-

(19)

-

(20)

-

(21)

-

(22)

It is worth pointing out that the general absence of focus encoding in Awing (reinforced in the upcoming subsection) seems rather unusual from a cross-linguistic or cross-Bantu perspective, esp. with regard to subject focus. There is a significant body of literature strongly suggesting that subject focus is always accompanied by some sort of formal encoding (see fn. 24 for some references). Zeller (2008:239), for instance, conjectured that the canonical SV order (accompanied by the presence of an agreeing subject marker on the verb) is incompatible with subject focus in Bantu. Awing is clearly different, as (20) demonstrates (see also (24) below). We perceive this state of affairs as fortunate for the current undertaking, as it allows us to strictly distinguish between “plain” focus and what we call exhaustive focus.

3.2 Focus associated with exclusive and additive particles (“bound” focus)

So-called focus-sensitive particles—of which we consider ‘only’ and ‘also’ here—convey something about the alternatives indicated by focus. The exclusive particle ‘only’ conveys that the asserted sentence corresponds to the strongest true proposition among the alternatives indicated by focus. For instance, John only loves Mary F conveys that John loves Mary and rules out that John loves anybody else, effectively by negating all other focus alternatives (John loves (Mary and) Sue, John loves (Mary and) Dave, etc.). The additive particle ‘also’ conveys that at least one focus alternative other than the asserted one is true. For instance, John also loves Mary F conveys that John loves Mary and, in addition, somebody else. The contributions of ‘only’ and ‘also’ differ in that the former is asserted, while the latter is presupposed.

The particles under discussion are both present in the Awing lexicon, though each has a different grammatical status and each exhibits a different relation to the focus that it associates with. Tśɔ’ə ‘only’ is a free-standing morpheme that left-adjoins to the focus that it associates with (to be qualified for the case of VP focus).Footnote 21 Kə́- ‘also’, on the other hand, is a verbal prefix realized in the Asp-slot of the template (see Sect. 2.2), which does not exhibit any structural relation to the focus it associates with. Below, we provide a range of examples of focus associated with tśɔ’ə ‘only’ and kə́- ‘also’. Due to the lack of any formal cue about where the focus is located, we stick to using the contextual cue and present the sentences as answers to wh-questions.

-

(23)

-

(24)

-

(25)

-

(26)

A number of remarks are in order. First, the reader will have noticed that the prefix kə́- ‘also’ does not only function as ‘also,’ but can also perform the role of a coordinator between two clauses. In some cases, the prefix is located in between the two clauses it coordinates, but this is not necessary, as demonstrated by the case of subject focus. Moreover, let us remind the reader that kə́- need not play the role of a conjunction; see example (15b) above, where kə́- simply serves as an additive marker in a mono-clausal structure. Second, the case of VP focus seems to violate our conjecture that tśɔ’ə left-adjoins to the focus that it associates with: it appears not to attach to the VP but to the object that belongs to the VP, thus ending up “within” the focus. However, there is a good reason to believe that tśɔ’ə does in fact attach to the VP (or some relatively low functional projection of the verb), but this attachment is blurred by a subsequent movement of the verb to a higher position. In Sect. 4, we present independent evidence that the Awing finite verb moves to the highest functional verbal projection available, which is, typically, Agr. For clarity, (27) presents the assumed (simplified) structure of B1 in (25), where xVP denotes some extended projection of VP.Footnote 22

-

(27)

Our third and last remark concerns verb focus associated with tśɔ’ə ‘only’, i.e., B1 in (26). This is the only case encountered thus far in which focusing requires a non-canonical structure. Superficially, what happens is that the whole clause is uttered (possibly to the exclusion of adjuncts), after which the verb in its bare stem form (note the absence of the n- prefix) appears, modified by tśɔ’ə ‘only’ (possibly followed by adjuncts). We hypothesize that this verb-doubling strategy arises as a solution to the conflict of two mutually independent requirements, namely that tśɔ’ə left-adjoins to its focus associate and that the verb itself cannot be separated from its functional morphemes. In analytical terms, we take the doubled verb to be an overt realization of the trace/copy left after verb movement, as indicated by the schematic structure in (28).

-

(28)

One question raised by the above discussion is why the verb is doubled in cases of verb focus, but not in the case of VP focus. We have no definitive answer, but would like to suggest that some sort of overtness requirement might be at play here, prohibiting the covertness of the whole constituent modified by ‘only.’

We include a brief but theoretically informed discussion of verb doubling when we get to the exhaustive particle le, which exhibits a similar pattern; see Sect. 4.4.

3.3 Summary and discussion

We have seen that in general, Awing does not encode focus at all. This state of affairs is expected for objects and perhaps VPs, the focusing of which represents, in some sense, the default information structure of sentences. On the other hand, it is somewhat surprising to find no marking of subject and verb focus, which have frequently been shown to require some marking or another; see e.g., Fiedler et al. (2010) for a survey of subject–object asymmetries in focus marking in West African languages and Güldemann (2003) or van der Wal and Hyman (2017) for investigations of verb/predicate focus in Bantu languages.

The only situation where some kind of encoding is obligatory is the case of verb focus associated with the particle tśɔ’ə ‘only’, in which case Awing exhibits a strategy of verb doubling. We hypothesized that this follows from two independent requirements: (i) that ‘only’ in Awing must adjoin directly to the focused constituent and (ii) that the main verb is inseparably connected to the functional prefixes. Doubling the verb in its bare-stem form is an elegant solution to this problem: the doubled verb stands (structurally) on its own and can therefore be directly modified by ‘only’. In what follows, we will see that verb doubling of this sort is a process that is independently attested in Awing. From that perspective, verb doubling does not represent a specialized verb-focusing strategy. Rather, it is a more general phenomenon of the Awing grammar, which can be utilized for the purpose of verb-focusing.

4 The exhaustive particle le in Awing

We now turn to the core of this paper: an analysis of the particle le. Our core syntactic proposal is introduced in Sect. 4.2. The functional sequence we assume for Awing is schematized in (29). The Exh head, hosting the le particle, differs from all the other heads in that it is not realized as an affix (marked by the lack of a hyphen on the Exh head), but rather as a free-standing particle. Due to this property, the verb is incapable of incorporating into the Exh head and skips it on its way upward (unless Agr is missing, in which case the verb lands in T).

-

(29)

In Sect. 4.3, we discuss another core ingredient of our analysis, namely the requirement that le must be in a certain structural relationship with the focus that it associates with. In particular, le obeys the so-called “closeness requirement” and always associates with the closest asymmetrically c-commanded maximal projection. We also address the question of how association with focus is ever possible in a language with no formal focus encoding.

Section 4.4 applies the proposal to an array of Awing data. We deal with various types of foci (object, indirect object, adjunct, subject, V, and VP) and show the particular structural descriptions that our proposal entails for these individual cases. The bottom line of the section is that Awing exhibits various information structure-related movements but that these are motivated at the interface, rather than in the narrow syntax. Also, we conclude that there is no need for a dedicated syntactic position for exhaustive foci in Awing.

In Sect. 4.5, we provide empirical arguments supporting the position that le expresses presupposed exhaustivity of the focus it associates with.

Section 4.6 focuses on the biclausal variant of the Awing le construction. We will argue that the analysis developed up to that point is directly applicable to it.

But before we get to the proposal and the analysis, it is necessary to set up the empirical scene and state the core generalizations, which we turn to now.

4.1 Core data and generalizations

Example (30) illustrates the two basic strategies of expressing exhaustive focus in Awing: the monoclausal and the biclausal one. Both make use of the particle le and in both cases, the particle precedes the focus it associates with. The difference is that in the monoclausal strategy, the focused constituent appears to be in its canonical position, whereas in the biclausal strategy it is placed extra-clausally and is modified by a relative clause, much like in English clefts.

-

(30)

We postpone a closer discussion of the biclausal strategy to Sect. 4.6, where we argue that our proposal—based on an analysis of the monoclausal strategy—extends to it readily.

As already suggested in the introduction, examples like (30a) create the impression that le directly attaches to the focus that it associates with, much like the exclusive particle tśɔ’ə ‘only’ does (see Sect. 3.2). This parallelism is supported when one inspects the focusing of postverbal or verbal constituents more generally. Example (31a) shows the case of adjunct focus, (31b) the case of verb focus, and (31c) the case of VP focus. As the reader can verify by consulting Sect. 3.2, the behavior of ‘only’ and le appears entirely parallel: le simply attaches to the focus it associates with, be it a direct object, an adjunct, or a verb (in which case verb doubling is employed). Also VP-focusing behaves as expected: le attaches to the object, which, we hypothesized in Sect. 3.2, might reflect a VP attachment in the syntax, obscured by the evacuation of V.Footnote 23

-

(31)

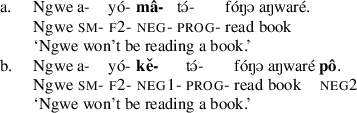

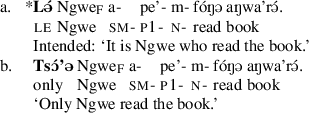

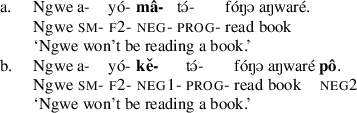

The simple generalization that le directly left-attaches to its focus breaks down when one considers the focusing of subjects. Example (32a) shows that attaching le to the subject results in ungrammaticality. Example (32b) reminds the reader that there is no problem with focusing preverbal subjects per se: modifying subjects by tśɔ’ə ‘only’ is grammatical.

-

(32)

Awing has two solutions to express the meaning intended in (32a): either it uses the biclausal strategy (see Sect. 4.6) or, using the monoclausal strategy, it places the subject postverbally, as shown in examples (33). These examples also show the two basic ways of dealing with canonically postverbal constituents in case the subject is postverbal: in (33a), the direct object and, more generally, all the postverbal constituents are placed clause-initially, and in (33b), the object and potentially other postverbal constituents appear in their canonical position, in which case, however, the verb must be doubled.Footnote 24

-

(33)

The discussion above brings us to the first core generalization, spelled out in (34).Footnote 25 The empirical pattern that follows from Generalization 1 is schematically represented in (35): (35a) is the licit case where the focus follows le and there is no maximal projection intervening; in the ungrammatical (35b), XP intervenes between le and the focused YP; and finally, in the ungrammatical (35c) the focused constituent does not follow le.

-

(34)

. Generalization 1: Relation between le and focus

The focus in Awing exhaustive constructions is the first maximal projection that follows le.

-

(35)

This generalization covers both the case where le and focus are immediately adjacent (the focusing of objects, adjuncts, and VPs), as well as the case where they are not adjacent, i.e., where the verb complex intervenes (the focusing of subjects)—both instances of (35a). Verb focus is covered by (34) on the assumption that what is focused is not a verb per se, but rather some maximal projection containing exclusively that verb. This stipulation is necessary to distinguish between in-situ verbs, which can be associated with le, and ex-situ verbs (verbs head-moved to T or Agr), which cannot be associated with le (see Sect. 4.4).

For completeness, we add a number of ungrammatical examples that support Generalization 1. The examples in (36) represent attempts to associate le with a constituent that follows it but not immediately. In (36a), the object intervenes between (a postverbal) le and the focused adjunct and in (36b), the subject intervenes between (a preverbal) le and the focused object. The examples in (37) (again, one with a postverbal and one with a preverbal le) represent attempts to associate le with a constituent that precedes it. All the examples violate Generalization 1 and all are ungrammatical under the intended interpretations (though of course, they have interpretations that are consistent with Generalization 1, as indicated).

-

(36)

-

(37)

Let us now turn back to the exhaustive focusing of subjects, where, as we illustrated in (33), the verb occurs between le and the focused subject. The ungrammatical data below complete the picture by demonstrating that le cannot be placed immediately before the subject.

-

(38)

This leads us to the second generalization, one that concerns the relative positioning of le, the verb, and the subject—see (39). Using “main verb” in the formulation avoids reference to a potential doubled occurrence of the verb. This generalization entails that out of the six possible permutations of S(ubject), V(erb), and le, only two are attested, as schematized in (40).

-

(39)

. Generalization 2: Relative position of le, V, and S

le and the subject are never on the same side of the main verb.

-

(40)

The data supporting Generalization 2 are summarized, for the reader’s convenience, in (41). Example (41a) corresponds to the SV pattern in (40a). It expresses exhaustive focusing of the object (and more generally, of (post)verbal material). Example (41b) corresponds to the VS pattern in (40b) and expresses exhaustive focusing of the subject. Example (41c) lists the various ungrammatical options corresponding to the SV patterns in (40c) and (40d); example (41d) lists the ungrammatical options corresponding to the VS patterns in (40e) and (40f). Notice that the presence/absence of the subject marker plays no role for the ungrammaticality and the sentences are ungrammatical under any imaginable information structure.

-

(41)

Another generalization implicit in the data above is that the availability of subject–verb agreement depends on the position of the subject with respect to the verb, as expressed in (42).Footnote 26 The consequences of Generalization 3, combined with independent properties of Awing (reported in Sect. 2.2), are listed in (43). Subject–verb agreement (i.e., the presence of a subject marker) is in principle optional in Awing. In the absence of agreement, the subject can in principle occur both preverbally and postverbally, as indicated by (43a) and (43b). Because Awing is a pro-drop language, the variant listed in (43c) is also allowed. However, if both the subject and subject–verb agreement are expressed overtly, the subject must be preverbal, as seen at the contrast between (43d) and (43e).

-

(42)

. Generalization 3: Subject agreement

Postverbal subjects never trigger agreement on the verb.

-

(43)

The data supporting Generalization 3 are in (44). Examples (44a) through (44e) correspond to the patterns in (43a) through (43e). The exhaustive marker le is optional with a preverbal subject or pro-drop (subject to a semantic alternation), but obligatory with a postverbal subject, as in (44b) (suggesting that the construction with a postverbal subject is a dedicated exhaustive focus construction).

-

(44)

The final relevant observation is that multiple le particles cannot be easily combined within a single clause. In order to illustrate this, let us again inspect the behavior of le as compared to the exclusive particle tśɔ’ə ‘only’: while (45a) is completely ungrammatical, the parallel (45b) is grammatical and felicitous (provided the right context is assumed).

-

(45)

Now, having multiple le particles in the postverbal position seems possible at first blush, as shown in (46a). However, there are two arguments that militate against allowing multiple le particles in the postverbal area. Firstly, the linearly second constituent modified by le in (46a) must be separated by an intonational break (which is not present by default). Examples like (46a) are therefore more likely to be analyzed as conjunctions of two clauses—each with its own le and with ellipsis in the second clause (similarly to the English translation). Secondly, once we consider a sentence with two postverbal constituents both of which are necessary for the grammaticality of the sentence, multiple le particles become ungrammatical, as shown in (46b).

-

(46)

We formulate this last observation as Generalization 4.

-

(47)

. Generalization 4: One le per clause

One clause can have at most one le particle.

Let us take stock. We saw that, despite an initial appearance, the exhaustive particle le does not directly attach (left-adjoin) to its focus. Instead, a slightly weaker generalization holds, namely that the focused constituent is the first maximal projection that follows le (Generalization 1). In many cases, this relation amounts to adjacency, but not so in the case of subject focus. We further showed that the exhaustive particle le interacts in non-trivial ways with independent phenomena in the Awing grammar. In particular, the particle le and the subject can never occur on the same side of the verb (Generalization 2) and a postverbal subject—one associated with le—never triggers agreement on the verb (Generalization 3). Finally, we noted that one clause can host at most one particle le (Generalization 4).

4.2 The Awing clause structure and the position of le

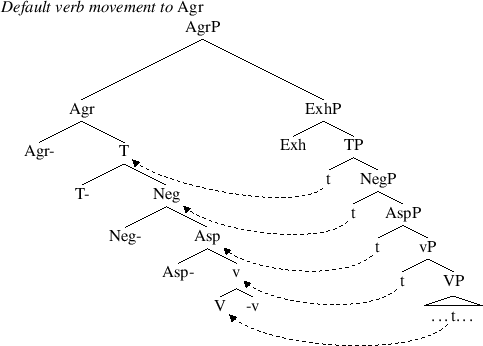

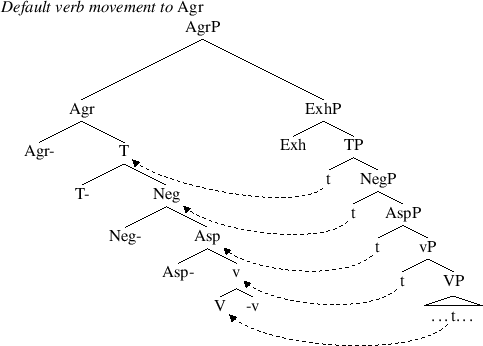

We propose that in the default case, the Awing verb moves to “collect” all of its affixes—from the suffix -v (verbal extension), through the prefixes Asp-, Neg-, T-, all the way to the topmost prefix Agr-, as schematized in (48).Footnote 27 If the Exh head is present, as in (48), the verb skips it on its way from T to Agr, in violation of Travis’s (1984) classical Head Movement Constraint. We can think of two reasons for why Exh is skipped by the verb: a morphological and a syntactic one. The morphological (superficial) reason would be that the exponent of the Exh head—the particle le—is simply lexically specified as a free morpheme rather than an affix.Footnote 28 The syntactic (deep) reason would be that the Exh head lacks the features needed to attract the verbal complex. As such, it would neither attract the verb, nor would it intervene for its movement (assuming standard relativized minimality). In the absence of relevant evidence, we shy away from choosing one option over the other.

-

(48)

As described in Sect. 2.2, not all of the verbal affixes need to be present all the time. In general, we remain agnostic about (i.e., have no evidence to decide) whether the lack of an affix entails the lack of the corresponding syntactic head. Crucially, however, we assume that the Agr head can be genuinely missing. In that case, the verbal complex “lands” in T and therefore follows the Exh head. This situation is schematized in (49).

-

(49)

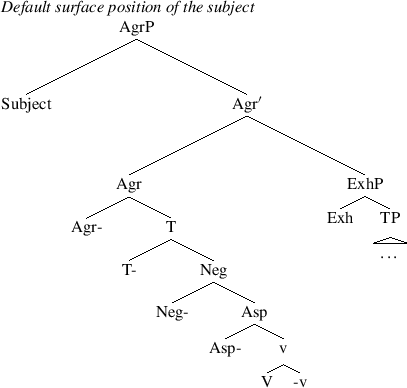

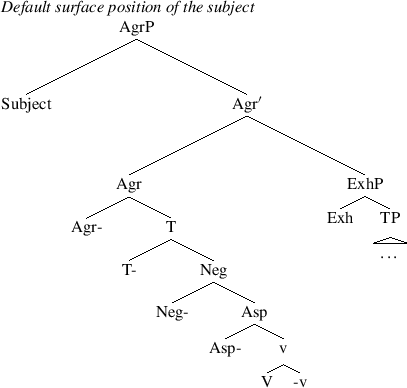

In the default case, the subject appears in SpecAgrP, as schematized in (50) (verb movement steps are ignored for simplicity). We take this to be a derived position of the subject and assume without discussion that it is base-generated within the vP.

-

(50)

When AgrP is missing and the verb stays in T, the subject surfaces lower in the structure, as schematized in (51). For the purpose of this paper, we set aside the question of where exactly the low subject is located. We believe that the issue is non-trivial and requires a proper analysis of verb doubling and the position of internal arguments in Awing, which goes beyond the scope of the present work.

-

(51)

Our analysis entails a direct dependency between the presence of Agr (whether overt or covert) and obligatory subject-movement to SpecAgrP. In feature-based terms, one could say that Agr has a subject-related EPP feature.Footnote 29 AgrP is always projected in Awing, the only exception being the case where the subject is exhaustively focused and remains in a low structural position.

In summary, our proposal consists of the following irreducible assumptions about Awing:Footnote 30

- A1 :

-

The exhaustive particle le spells out the functional head Exh (located between Agr and T).

- A2 :

-

The verb moves to the highest extended verbal projection available (Agr by default).

- A3 :

-

Exh is invisible for purposes of verb movement.

- A4 :

-

The presence of Agr forces subject movement to SpecAgrP (EPP on Agr).

- A5 :

-

The absence of Agr entails an AspP-internal subject (no EPP on T).

Let us now see how these assumptions derive Generalizations 2–4 from Sect. 4.1. Consider first Generalization 4, namely that there is at most one le in a clause. This follows from the assumption that le is an exponent of the functional head Exh (A1) rather than a free-standing modifier (as, arguably, the word for ‘only’ in Awing). Now consider Generalization 2, namely that le and the subject are never on the same side of the verb. If Agr is present, the verb moves to it (by A2), thereby moving to the left of le (Exh) (by A3). At the same time, the subject must move to SpecAgrP (by A4), thereby moving to the left of the verb. This derives the S V le order. If Agr is absent, the verb moves to T (by A2), thereby staying to the right of le. At the same time, the subject stays within the AspP (by A5). This derives the le V S order. No other possibilities are allowed. Finally, consider Generalization 3, namely that postverbal subjects never trigger agreement. The only way to derive a postverbal subject is by not projecting Agr, since Agr would force movement of the subject to a preverbal position (A4). Since Agr is the locus of subject–verb agreement, it can never occur with postverbal subjects.Footnote 31

4.3 Association of le with focus

What remains to be discussed is Generalization 1, which states that le associates with the closest constituent following maximal projection. In this section, we suggest how Generalization 1 could be captured and discuss some theoretical implications of the proposal.

In Sect. 3, we showed that there is no general prosodic, morphological, or syntactic strategy of encoding focus in Awing, certainly not one that would be comparable to focus encoding by prosodic prominence, well-known from European languages. The implication is that focus structure is contextually determined. However, we have witnessed two cases in which focus is, at least in part, determined morphosyntactically. This is the case of focus associated with the particle tśɔ’ə ‘only’ and with the particle le. Here we concentrate on le, but an analogous reasoning applies to tśɔ’ə, too.Footnote 32

Since Jackendoff (1972) it has been commonly assumed that focus is marked in syntax—by a diacritic marker F placed on syntactic constituents. We use boldface for “syntactic” F-markers in order to distinguish them from the mere indication of where semantic focus is located. (The distinction can be appreciated by considering the fact that a verb can be semantically focused, but it cannot, under our proposal, be syntactically F-marked.) For English (and many other languages), F-marking is, albeit not unambiguously, expressed by prosodic prominence. Roughly, it holds that prosodic prominence (nuclear stress) must be realized within the F-marked constituent. Even though these core assumptions are part of Rooth’s (1992) alternative semantics for focus, whose basic tenets we subscribe to, it does not seem adequate to us to assume any kind of free F-marking for Awing, simply because we see no empirical evidence for it. Obviously, this leads to a fundamental problem in applying Rooth’s theory of focus association to the Awing data.Footnote 33 Rooth’s basic idea is that there is an operator, namely ∼ (“squiggle”), which “associates with focus” or, more technically, it operates on the focus semantic value of its syntactic complement. The focus semantic value, in turn, is determined by F-marking. Two identical syntactic structures with two different F-markings have two different focus semantic values (marked by  ), as illustrated schematically in (52). If appropriate particles are used, such as the exclusive only or the additive also, the difference in the focus semantic value can translate to a semantic difference.

), as illustrated schematically in (52). If appropriate particles are used, such as the exclusive only or the additive also, the difference in the focus semantic value can translate to a semantic difference.

-

(52)

The problem is that if we want to stick to the assumption that there is no F-marking in Awing, then a focus sensitive operator in this language, or le in particular, has nothing to associate with (nothing to operate on). One could object that focus sensitive operators are, in fact, not focus sensitive but rather “question sensitive”, as in Beaver and Clark (2008), who propose that these operators associate with the current “question under discussion”. But this would not solve the problem fully. We saw that there is a clear structural condition on what the focus can be in the Awing le construction. This condition ultimately overrides any contextual cues.

For the lack of anything better, we propose that the F-marking on the constituent that le associates with (deriving the focus semantic value of le’s complement), is introduced by le (Exh) itself. This is done by the rule (53).Footnote 34 Relative distance is defined in terms of asymmetric c-command; see (54).Footnote 35

-

(53)

. F-marking by Exh

Place an F-marker on one of the closest maximal projections asymmetrically c-commanded by Exh.

-

(54)

. Relative distance to Exh

X is closer to Exh than Y if both are c-commanded by Exh and X asymmetrically c-commands Y.

Note that the rule implies that there can be more maximal projections that are “closest” to Exh. This follows from the standard assumption that c-command excludes dominance (see e.g., Rizzi 2013): if two constituents are in a dominance relationship, then they are not in a c-command relationship and therefore, one cannot be closer than the other. If both are asymmetrically c-commanded by Exh, both are eligible for F-marking. The situation is schematized in (55), where XP, YP, and ZP all equally qualify for being F-marked, since all are asymmetrically c-commanded by Exh and it holds for all of them that there is no projection that is closer to Exh. WP cannot be F-marked because it is asymmetrically c-commanded by YP. We will see in Sect. 4.4 how this underspecification leads to focus ambiguities of certain structures.

-

(55)

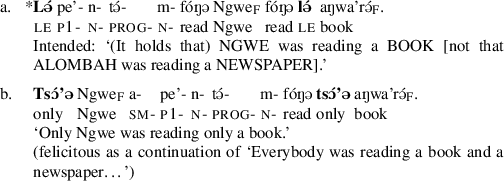

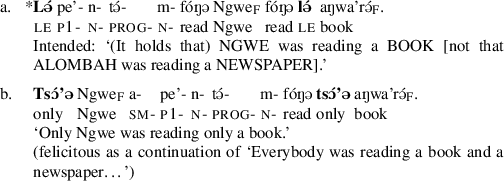

A few theoretical remarks are in order. To start with, we should note that the minimality-based focus association that our proposal entails is not a novel theoretical concept and it is not specific to Awing. It has been observed for German (Jacobs 1983; Büring and Hartmann 2001) and for Vietnamese (Erlewine to appear) that focus-sensitive particles associate with the closest possible constituent. This “closeness requirement” accounts for the pattern in (56), illustrated on German. In (56a), the focus-sensitive particle sogar ‘even’ associates with the subject Rufus (capitals mark prosodic prominence). (56b) shows that the same syntactic configuration does not allow for an association with dem Mädchen ‘the girl’ (despite it being prosodically prominent) because it is not close enough to sogar. In order for the intended association to work, sogar has to be placed lower, as shown in (56c).

-

(56)

There is a notable difference between this pattern (which could, by the way, also be illustrated by using the Awing exclusive particle tśɔ’ə ‘only’) and the patterns involving le: while the position of German sogar ‘even’ is flexible, i.e., it can be placed as close to the focus as possible, the position of the Awing le is fixed. Consequently, the intended association configurations can only be achieved by phrasal movements in Awing, in particular movements “out of focus” and, potentially, “into focus”; see Sect. 4.4. The broader theoretical implication of the Awing facts is that closeness is not contingent on the positional flexibility of the focus-sensitive particle.

Let us now move on to another theoretical concern: Is the present proposal compatible with the Strong Modularity Hypothesis for Discourse Features, which we endorsed in the introduction? The worry one might have is that F-markers are focus features of sorts (as suggested, e.g., by Szendrői 2005; but see Horvath 2013 for a view compatible with ours). This is even more articulated in our proposal where F-marking seems driven by a functional head and is constrained by minimality. Together with an anonymous reviewer, we can ask: How is the proposed process of F-marking different from feature checking/valuation in probe-goal configurations?Footnote 36 We do not want to deny the similarities, which are obvious, but would like to highlight a number of important differences, which make us believe that F-markers are fundamentally different from formal features. Firstly, formal features are, by definition, lexical. F-markers are not: being focused is hardly a lexical (i.e., inherent) property of linguistic expressions. The second point, closely related to the first one, is that formal features are located on heads (minimal projections); F-markers, on the other hand, are located on maximal projections (at least in Awing and if our proposal is correct). Thirdly, F-markers can be placed on a constituent of virtually any syntactic category. As opposed to that, formal features are usually highly constrained in terms of the syntactic categories they “live on”.

If F-markers are not formal features, the next logical question is what they are. It seems conceptually unsatisfactory to assume that F-markers are entities sui generis and that their properties are ad hoc and cannot be deduced from anything more general. Our view is that an F-marker is a species of a referential index.Footnote 37 Referential indices, like F-markers, are highly unselective in terms of the syntactic category they represent: there are pronouns that stand for NPs, DPs, APs, VPs, CPs, etc.Footnote 38 Also, the use of referential indices can be context dependent (and hence non-lexical): whether a VP or CP will figure in (co-)referential discourse relations is certainly not a lexical choice. Finally, see Kratzer (1991) for arguments to the effect that mere F-marking is not sufficient; according to Kratzer, F-markers must be indexed, just like pronouns.Footnote 39

4.4 Structural descriptions of constructions with le

In this section, we show how our general and unified analysis of le yields syntactic structures of sentences with exhaustive focus placed on a variety of constituents: object, indirect object, subject, verb, and verb phrase. What all these structures have in common is that le is located in Exh (Sect. 4.2) and that the focus is (one of) the closest maximal projection(s) asymmetrically c-commanded by le (Sect. 4.3). Beyond that, our analysis implies no specific syntactic position of exhaustive focus in Awing.

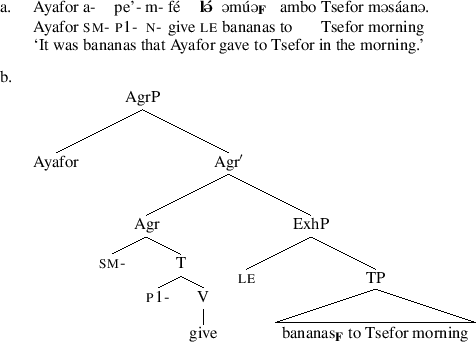

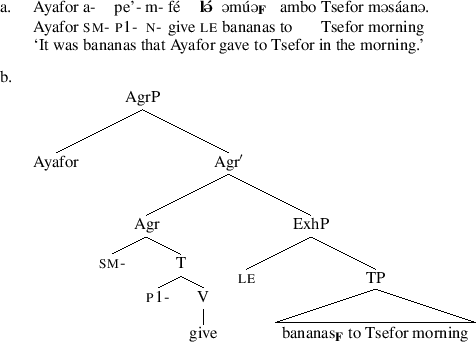

Let us start with the simplest case: exhaustive focus on the direct object, as in (57a). This sentence receives the structural description in (57b) (we use glosses as terminals for readability). The focused object əmúə ‘bananas’ is in its canonical position, somewhere in the TP (and presumably within the vP). It receives the intended exhaustive interpretation because it is the closest maximal projection in the asymmetric c-command domain of le.

-

(57)

Now consider example (58a), where the indirect object ambo Tsefor ‘to Tsefor’ is exhaustively focused and hence directly preceded by le. The direct object is sandwiched between the verb and le. How does this word order arise? Our analysis strongly implies that le is in Exh and that the verb is in Agr. The only possibility, therefore, is that the direct object is located above ExhP but below Agr. There are two options—either it is left-adjoined to ExhP or it is in SpecExhP. We choose the former, mainly to avoid the implication that the object is attracted by Exh. We take the movement of the object from within TP to the edge of ExhP to be a kind of scrambling licensed at the interface. It takes place in order to create a configuration that is in line with Generalization 1, namely that the focus be the closest constituent asymmetrically c-commanded by le. At this point, this movement might seem ad hoc, but we will soon see that it is available more generally (in particular also in the case of subject focus). It is also worth pointing out that the focus itself—ambo Tsefor ‘to Tsefor’ in this case—occupies no designated focus position. Under our analysis there is no need to abandon the null hypothesis that it is simply in situ.Footnote 40

-

(58)

Finally, let us consider a slightly more complex case, represented by the adjunct focus example (59a), where there are, apparently, two constituents between the verb and le: the direct and the indirect object. We can think of two analytical possibilities. One is that these constituents move independently to the edge of ExhP, as illustrated in (59b). The other is that both objects are part of a single constituent—a remnant xVP (some extended projection of VP), as illustrated in (59c).

-

(59)

Both of the analyses are plausible, though they also have their issues. The former analysis faces the problem of order preservation, i.e., that the objects keep their base order, despite both having moved. An account of order preservation that we consider compatible with our assumptions can be found in Fox and Pesetsky (2005). The latter analysis implies that the objects form a constituent to the exclusion of the adjunct. Such a configuration could obtain already in the base-generated structure, provided that temporal adjuncts right-adjoin to some xVP, containing both objects.Footnote 41 Alternatively, it could involve an intermediate step, one where the adjunct scrambles out of the relevant xVP before that xVP remnant-moves to merge with ExhP. Interestingly, there is evidence that such type of scrambling is attested in Awing, as shown in (60). Example (60a) shows that the canonical direct object–indirect object order can be reversed and example (60b) shows that the adjunct can be placed in front of both objects.Footnote 42

-

(60)

It is notable that these non-canonical orders exhibit restricted information structuring possibilities. First, the question–answer test reveals that while the scrambled constituent can be interpreted as focused, the constituents that are crossed by the scrambling cannot. For instance, (60a) could be preceded by the question in (61a), but not by (61b). Second, as illustrated by (62) (a modification of (60a)), only the scrambled constituent can be preceded by le, which also supports the backgrounded (non-focus) status of the constituents crossed by scrambling.Footnote 43

-

(61)

-

(62)

These findings raise the question of what forces scrambled constituents to be interpreted as focused and, relatedly, what kind of focus is being implied by the construction at hand. We can only speculate at this point that le has a covert counterpart, projected by a variant of the Exh head. The presence of such a covert head would only be obligatory if it were needed to satisfy the effect-on-output condition (Chomsky 2001): Scrambling as an optional operation is prohibited as uneconomical, unless it produces an output (interpretation) that would not be possible without the scrambling. This in turn implies that scrambled foci are somehow semantically different from non-scrambled ones. For the present paper, we leave open the issue of how different they are and concentrate further on constructions with le.

We now turn to the case of subject focus. We saw that there are essentially two options to express subject focus within the monoclausal strategy, both of which share the property that the subject, located somewhere within the extended VP, is the first maximal projection asymmetrically c-commanded by le.Footnote 44 In one of them, illustrated in (63), the canonically postverbal material moves to a preverbal and pre-le position. We assume that this is the same position that objects move to when they “clear out” the space for another postverbal focused constituent. In the other option, illustrated in (64), the canonically postverbal material remains postverbal, but is accompanied by a doubled verb.

-

(63)

-

(64)

The examples below show that these two options can in fact be combined: one constituent can stay in situ, while another one moves to the edge of ExhP. The examples also illustrate that as long as some constituent stays in the post-subject position, the verb must be doubled.

-

(65)

The reason why the verb doubles in cases like (64) and (65) remains unclear. The issue requires further investigation, which goes beyond this paper.Footnote 45 The question that we would like to address, at least superficially, is what motivates the choice among the word order alternatives that Awing makes available in the exhaustive subject focus construction. To a certain extent at least, the choice is information-structurally driven. In particular, it seems that pre-le constituents receive a contrastive topical (CT) interpretation (where contrastive topic is understood in the classical sense of Büring 2003). For instance, (65a) would be a particularly natural continuation to ‘As for the riceCT, it was NgweF that gave it to Tsefor’ (CT on direct object) and (65b) would be a natural continuation to ‘As for NgweCT, it was AlombahF that gave him bananas’ (CT on indirect object). Having said that, we believe that this does not constitute evidence for a specialized contrastive topic position in Awing. First, there is no categorical (grammatical) requirement for contrastive topics to be placed there. Second, the pre-le position can remain unfilled, as demonstrated by (64). This means that our “weak” assumption that pre-le constituents are simply adjoined to ExhP, seems to carry over to these cases well.Footnote 46

Let us move on to the exhaustive focusing of verbal categories. Consider first our example of verb focus—(66a) (repeated from Sect. 4.1). In this case, the verb—in its bare stem form—gets doubled in a position after le, thus achieving the required association. We propose that this doubling instantiates a spellout of a lower copy of the verb.Footnote 47 The object (or any other preverbal material) moves out of the way to the edge of ExhP. We can only speculate why the object moves out of the TP obligatorily. Either the object would intervene between le and the doubled verb, disrupting the relation between le and the focused verb (suggesting that Awing is, at some level of representation, an OV language; see fn. 12 and Kandybowicz (2008) for some relevant discussion), or, if the object stayed in the complement of le, the verb would not be prominent enough to be interpreted as focused (which in turn would require an additional constraint on the association of le with focus). The resulting structure is in 66b (the unclear base order is indicated by placing the xVP-internal material into curly brackets).Footnote 48

-

(66)

Spelling out multiple copies of an expression is certainly a marked strategy but it is well-motivated in this case because it represents the only strategy that satisfies the independent requirements of exhaustive verb focusing. Let us briefly consider the potential alternatives. In the canonical word order S V le O, or S V O le, le does not precede the intended focus. The order S le V O (a violation of Generalization 2) cannot be derived because V moves to Agr which is higher than Exh. The alternative which one could expect to be successful is le V S (V O) or O le V S. In these cases—reserved for subject focus—the verb follows le. However, verb focus interpretation of these structures is not available. This follows from our assumption that le can only “see” maximal projections.

Verb doubling as a strategy of verb or verum focus marking is in fact a fairly common phenomenon cross-linguistically (see Kandybowicz 2008 for a comprehensive discussion). A particularly popular analysis of this phenomenon is the so-called parallel chain analysis, in which both overt verb copies head a movement chain of their own (Aboh 2006; Collins and Essizewa 2007; Kandybowicz 2008; Aboh and Dyakonova 2009). Consider Collins and Essizewa’s Kabiye (Gur) example in (67). The pattern looks superficially very similar to the one in Awing: a standard transitive structure (VO) is followed by an infinitival copy of the main verb. That copy is preceded by the marker kí, which the authors analyze as a focus marker. The authors argue that two types of V(P) movement have taken place in the derivation of (67). First, V moves to a low SpecFocP (“low” in the sense of Belletti 2004), which is selected by a head realized by the focus marker kí, labeled simply as KI, after which the remnant VP moves to SpecKIP. Last, V gets extracted from within the fronted remnant VP and moves to I, headed by the imperfective marker. As a result, both the finite and the infinitival copy of the verb head their own movement chain: the lower (infinitival) one is located in SpecFocP and the higher (finite) one in I. Standard spell-out rules apply and both copies get overtly spelled out.

-

(67)

As far as we can tell, there is nothing that would explicitly militate against the use of parallel chains in Awing verb focus structures, which could in principle be analyzed along the lines of Collins and Essizewa’s analysis of Kabiye. At the same time, however, we see no independent evidence supporting this idea: as we have argued, Awing exhaustive foci remain, by default, in situ. It is therefore unclear what would force a focus-related verb movement in Awing.

In sum, our current informal analysis has it that Awing focus-related verb doubling is an interface-conditioned realization of both copies of one and the same chain. While such an analysis may be non-standard, we see no explicit support for parallel chains. More research has to be done to gain a solid understanding of verb doubling in Awing, which, as we have seen, does not only occur in verb focus environments, but also in subject focus environments.

The type of exhaustive focus remaining to be discussed is VP focus, an example of which is given in (68a). The syntactic structure we propose for VP focus is entirely parallel to the one assumed for object focus, as shown in (68b): the structure/word order is canonical, with le following the verb and preceding the object. We propose that in this case le associates with the whole VP (or some extended projection of the VP). Even though the object is the only constituent overtly spelled out within the VP, it seems natural to assume that the verb (or its covert copy) is available for interpretation in the VP.

-

(68)

The only problem that remains to be discussed is the problem of focus ambiguity: the configuration in (68b) (or (57b)) is ambiguous between VP focus and object focus. Our definition of relative distance to le in terms of asymmetric c-command, introduced in Sect. 4.3, provides an adequate account of this phenomenon: There is no c-command relation between the VP and the object contained in it. For that reason, neither counts closer to le than the other. And since both count as being closest, both can be F-marked.

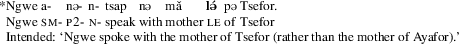

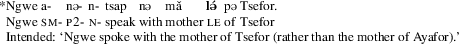

Perhaps it comes as no surprise that the type of ambiguity considered is observed more generally. For instance, the sentence in (69) is four-way ambiguous, depending on whether the exhaustive focus is on the whole VP, on the larger NP ‘mother of Tsefor’, the smaller NP ‘mother’, or on the possessor phrase ‘of Tsefor’. (While ‘mother’ and ‘of Tsefor’ are not in a dominance relation, they are not in an asymmetric c-command relation either.)Footnote 49 , Footnote 50

-

(69)

Finally, let us point out that examples like (68a) or (69) do not allow for an interpretation whereby the whole clause (including the subject) is in focus (see also fn. 44 for a related issue). In other words, the subject must be interpreted as part of the background. We can only speculate why this is the case. It could be that it is pragmatically odd to place a whole clause (proposition) into an exhaustive focus without providing any overt background: there would be no formal source of restricting the focus alternatives. A second option is that the subject cannot reconstruct for focus interpretation to a position within the extended VP; notice that reconstruction to SpecTP would not be of help because TP, which is not asymmetrically c-commanded by le, cannot be F-marked under our proposal from Sect. 4.3. We leave this issue for future research.

In summary, we have showed that the basic proposal introduced in Sects. 4.2 and 4.3, together with a number of additional assumptions, generates a set of syntactic structures that are plausible structural descriptions of sentences containing le and an exhaustive focus that it associates with. The additional assumptions introduced in this section are summarized below.

- A6 :

-

Canonically postverbal constituents (objects, adjuncts, VP) can move to the edge of ExhP in Awing. This movement is not feature-driven (optional from the perspective of syntax) and is licensed at the interface.

- A7 :

-

The verb can be spelled out twice—once incorporated in the functional complex and once in its bare stem form in the VP.

We showed that A6 is needed quite generally, to account for the focusing of canonically postverbal material such as indirect objects or adjuncts that are preceded by something else in the postverbal position, for the focusing of subjects, as well as for the focusing of verbs. Assumption A7 is needed for verb focus, but might also be helpful in one of the subject focusing strategies. The exact nature of verb doubling in Awing remains an open issue.

4.5 Evidence for presupposed exhaustivity

We have stated and further assumed that the construction under investigation involves exhaustive rather than “plain” focus. In this section, we provide empirical evidence which supports this assumption and justifies translating the Awing le construction with the help of the English cleft construction.

According to the state-of-the-art proposal of Velleman et al. (2012), English clefts convey two meanings.Footnote 51 They assert that the prejacent is true and presuppose that any focus alternative stronger than the prejacent is false. We refer to the latter inference as presupposed exhaustivity. Consider a simple example: (70a) asserts that the prejacent, i.e., ‘Dave and Sue smoke’ is true, and presupposes that any stronger alternative, e.g., ‘Dave, Sue, and Lynn smoke,’ is false. In other words, (70a) exhaustively identifies the smokers: Dave and Sue smoke, but nobody else does. The presuppositional nature of the exhaustive inference is illustrated by (70b) and its continuations. While the prejacent, namely ‘Dave and Sue smoke’ is targeted by negation, the presupposition that no stronger alternative is true survives, as indicated by the infelicity of the continuation in (70biii).

-

(70)

We will now go through a number of tests showing (i) that the Awing le construction is exhaustive and (ii) that its exhaustivity is presupposed rather than asserted.

If sentences with le express exhaustivity, they should be logically incompatible with continuations that deny the exhaustive inference. If Dave and Lynn smoke is true and exhaustive, i.e., it conveys that Dave and Lynn and nobody else smokes, it is a contradiction for the speaker of this proposition to follow up with and Sue smokes, too. Consider first an Awing sentence without le, as in (71a), and suppose that it is uttered as an answer to a question like ‘What did Ayafor kill?’ The sentence is composed of two conjoined clauses where the first states that Ayafor killed a chicken and the second adds—using the additive prefix kə́-—that he also killed a goat. Example (71b) differs only by employing the particle le, associated with the direct object ŋgəbə́ ‘chicken’. In this case, it is incoherent to follow up by saying that Ayafor also killed a goat. The intuition is that the two conjoined clauses contradict each other—just as expected under our semantic analysis of le.

-

(71)

To draw a fuller picture, we add an analogous minimal pair, this time employing subject focus. Again, the variant with le is intuitively a contradiction. This lends further support to our unified analysis of le—whether it is postverbal or preverbal.

-

(72)

The examples below compare the behavior of focus associated with tśɔ’ə ‘only’ vs. le. The exclusive particle ‘only’ asserts the exhaustivity of its prejacent. The particle le, by assumption, presupposes the prejacent’s exhaustivity.Footnote 52 There are a number of ways in which the difference between assertion and presupposition can be tested. We illustrate two of them below. In (73), we see that the initial assertion, namely that Ngwe bought a goat, can be followed up by the same proposition modified by ‘only,’ given in (73a). This is possible because the exhaustivity of the proposition is asserted, which is the proper (or at least prototypical) way of conveying new information (updating the common ground). The clause in (73a) directly contrasts with the one in (73b), which is inappropriate as a continuation to the initial assertion. The reason is the particle le presents the exhaustivity of the focus as presupposed, which is (typically) a very marked way of conveying new information.Footnote 53

-

(73)

The examples in (74) and (75) bring out the differential status of exhaustivity by using negation and continuations with ‘also’ and le. Example (74) is a combination of negation with the exclusive particle tśɔ’ə ‘only’ (modifying the direct object mbiŋə́ ‘goat’). The exhaustivity of the exclusive particle is asserted and therefore targeted by negation, ultimately conveying that a goat was not the only thing that Ngwe bought. Consequently, the additive continuation that Ngwe also bought a chicken, see (74a), is a natural one. By contrast, continuing with the le statement (74b) is infelicitous. This is expected under our present analysis, under which le presupposes exhaustivity. Consider this in more detail: The initial statement (74) entails that Ngwe bought a goat and, in addition, something else. And even though the continuation with le suggests that Ngwe bought a chicken (potentially satisfying the ‘something else’ entailment of the previous statement), it also presupposes that he bought nothing else than a chicken—directly contradicting an entailment of the initial statement.

-

(74)

Now, consider the case of negation combined with the le particle, as in (75). According to our proposal, the exhaustivity of le is presupposed and is therefore expected to survive the embedding under negation. What the negation targets is only the prejacent, conveying that Ngwe didn’t buy a goat. The continuations support this view. In contrast to (74a), the additive continuation in (75a) is infelicitous because it entails that Ngwe bought something else besides a chicken. This entailment, however, is not supported by (75). The continuation with le in (75b), on the other hand, is felicitous: it naturally picks up on the exhaustive presupposition of the statement with le, reiterating it and at the same time filling in the information on which proposition is the strongest true one, namely that Ngwe bought a chicken.

-

(75)

In summary, we have presented evidence supporting the assumption that le conveys presupposed exhaustivity (also known as exhaustive identification). For reasons of space, we have not provided a semantic lexical entry for le and a compositional analysis of how le combines with its prejacent. It can in principle be shown, however, that le closely corresponds to the operator cleft proposed by Velleman et al. (2012).

4.6 Biclausal strategy

In the introduction and in Sect. 4.1, we showed that besides the monoclausal strategy of expressing exhaustive focus, Awing exhibits a biclausal strategy, too. The relevant minimal pair is repeated below. It is worth highlighting that these strategies differ syntactically, but not semantically: there is no truth-conditional or presuppositional difference between (76a) and (76b). (We refrain from showing this explicitly for reasons of space.) This constitutes a strong argument that le in both structures is one and the same element.

-

(76)

In this section, our aim is to show that despite apparent problems, the biclausal strategy is readily accounted for by our proposal.

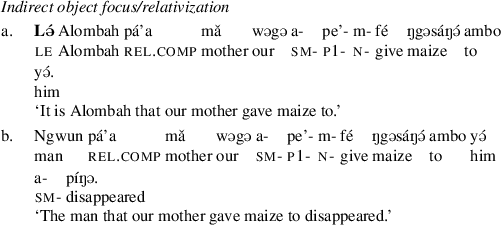

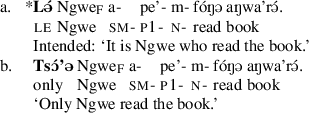

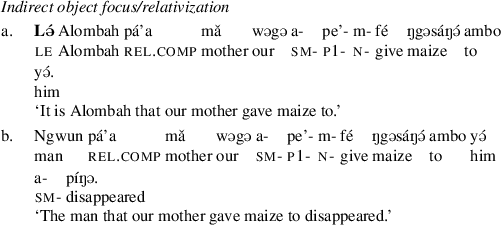

The biclausal structure consists of two main parts (two clauses, as we will argue): (i) a focused constituent preceded by the le particle (lə́ aŋwa’rə́-əsé ‘le Bible’ in (76b)) and (ii) a relative clause with a gap or a resumptive pronoun that corresponds to the focused constituent (pá’a Ngwe a- nə- m- fóŋə ‘that/which Ngwe read’ in (76b)).Footnote 54 Let us first concentrate on the relative clause part of the structure. The following examples make it transparent that this structure perfectly matches the corresponding relative clause. In subject and direct object relatives, (77) and (78) respectively, there is a gap in the relativization site. When the relativization site is embedded in a PP, as in (79), it is filled by a resumptive pronoun.

-

(77)

-

(78)

-

(79)

This empirical pattern makes it highly plausible that the focused constituent in the biclausal le construction functions as a head of a relative clause, providing a value for the operator-bound variable in the relativization site. The general schema for such an analysis is provided in (80).

-

(80)