Abstract

Background

Maternal depression and anxiety occurring beyond the 1-year postpartum period can lead to significant suffering for both mother and child. This study aimed to systematically review and synthesize studies reporting the prevalence and incidence of maternal depression and anxiety beyond 1 year post-childbirth.

Methods

A systematic literature review of the PsycINFO, Medline, and Embase databases identified studies reporting on the prevalence and/or incidence of depression and/or anxiety among mothers between 1 and 12 years post-childbirth. The quality of the included studies was assessed. Findings were synthesized qualitatively.

Results

Twenty-one studies were identified that met the inclusion and exclusion criteria. All studies reported the prevalence of depression, with 31 estimates ranging from 6.6% at 3 to 11 years post-childbirth to 41.4% at 3 to 4 years post-childbirth. Five of these studies also reported the prevalence of depression in subgroups (e.g., ethnic origin, income, marital status). Four studies reported the prevalence of anxiety, with nine estimates ranging from 3.7% at 5 years post-childbirth to 37.0% at 3 to 4 years post-childbirth. Only one study reported incidence. The quality of the included studies was variable, with most studies scoring above 7/9.

Conclusion

Maternal anxiety and depression remain prevalent beyond the first year postpartum, particularly in marginalized subgroups. Current observational studies lack consistency and produce highly variable prevalence rates, calling for more standardized measures of depression and anxiety. Clinical practice and research should consider the prevalence of maternal anxiety and depression beyond this period.

Significance

Maternal depression and anxiety that occur beyond the first postpartum year, a commonly overlooked period in research and practice, can lead to adverse outcomes for women and their children. There is no systematic review of the prevalence of depression and anxiety in women after the first postpartum year. We identified 21 studies that reported the prevalence of maternal depression between 6.6 and 41.4% between 1 and 12 years post-childbirth. Four studies reported the prevalence of anxiety between 3.7 and 37.0%. Estimates were higher in marginalized groups. Our results may assist in identifying high-risk women and inform appropriate prevention and treatment strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

It is widely recognized that postpartum mental health impacts women and their families alike. For the women, postpartum depression and anxiety can impede daily functioning and quality of life. In addition to affective symptoms, women may experience a reluctance to breastfeed (Hatton et al., 2005), anxiety attacks (Beck, 1992), and impaired parenting behaviours (Flynn et al., 2004; McLearn et al., 2006). Maternal depression and anxiety have been linked to poorer social engagement (Feldman et al., 2009), depressive symptoms and psychiatric disorders (Priel et al., 2020), and insecure attachment style (Campbell et al., 2004) in their children. Maternal postpartum depression is also the strongest predictor of paternal postpartum depression in part due to impaired spousal support and diminished relationship satisfaction (Don & Mickelson, 2012; Goodman, 2004; Paulson & Bazemore, 2010).

Clinical practice and research often define postpartum depression as major depressive disorder with an onset within 1 year of giving birth (Gaynes et al., 2005). The estimated prevalence of depression in the first year postpartum ranges from 5.0 to 26.3% (Liu et al., 2022; O’hara & Swain, 1996; Underwood et al., 2016; Woody et al., 2017). The DSM-IV does not recognize postpartum anxiety, despite being highly comorbid with depression and the high prevalence of anxiety symptoms in postpartum women (Fawcett et al., 2019; Ross & McLean, 2006; Wenzel et al., 2003). Accordingly, anxiety is less frequently screened for in primary care despite an estimated prevalence in the first year postpartum ranging from 8.5 to 9.9% (Dennis et al., 2017; Goodman et al., 2016).

From a primary care and public health perspective, maternal depression and anxiety that beyond the 1-year postpartum period can still lead to suffering and adverse outcomes for women and their families. A large systematic review found that the maternal consequences of long-term postpartum depression and anxiety included difficulty maintaining social and marital relationships, depression recurrence, and risky behaviours (Slomian et al., 2019). Mental health problems in mothers of young children have also been associated with poorer school performance, stunting and underweight, and higher psychological problems in their children (Bennett et al., 2016; Closa-Monasterolo et al., 2017; Shen et al., 2016). Furthermore, the influence of parental mental health on child health is most prominent during the formative, pre-adolescent years of child development (i.e., up to age 12), where significant cognitive, emotional and social transitions occur (Collins & Madsen, 2019). For instance, Agnafors et al. (2013) demonstrated that persistent depressive symptoms in mothers were the strongest predictor of behaviour problems in children at age 12.

Understanding when in the 12 years following delivery women experience depression and anxiety has important implications for screening, treatment, and allocation of mental health resources, especially given the profound impact of maternal affect on child development. Further, understanding subgroups of women according to demographic or socioeconomic factors that experience an increased burden of anxiety and depression beyond the first postpartum year can assist in identifying women for targeted preventative action.

Although there are single studies that have assessed anxiety and depression status in women beyond the first year postpartum, to our knowledge, no systematic review examining their prevalence and incidence exists. This review aims to systematically review and synthesize the studies on the prevalence and incidence of depression and anxiety in women 1 and 12 years after giving birth.

Methods

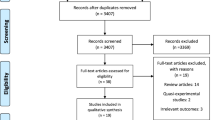

The systematic review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Moher et al., 2009). The PRISMA 2020 checklist can be found in Online Resource 1. The study protocol was published in the PROSPERO international prospective register of systematic reviews (CRD42022325002).

Search Strategies

A literature review was performed in Medline, Embase, and PsycINFO databases from their inception to December 22, 2022. The search used terms related to three themes: (1) incidence and prevalence, (2) depression and anxiety, and (3) mothers 1 to 12 years post-childbirth. Full search strategies are included in Online Resource 2.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Studies measuring the prevalence and/or incidence of depression and/or anxiety in women after 12 months and before 12 years post-childbirth using diagnostic criteria (e.g., DSM) or validated screening scales to measure anxiety and depressive symptoms were included. The exclusion criteria were: (1) review papers, non-full-text papers, and non-English papers; (2) studies that assessed women at or before 1 year postpartum; (3) studies analyzing secondary data from the same original cohort. In the case of multiple studies that analyzed anxiety and depression from the same cohort, only one study was included in the review. That choice of inclusion was made in consensus by the authors based on the recentness of the study, number of time points analyzed, measurement of both anxiety and depression, and study quality. In this way, two studies were excluded entirely (Barthel et al., 2017; Netsi et al., 2018), one study was excluded for one depression estimate (Woolhouse et al., 2015), and one study was excluded for one anxiety estimate (Woolhouse et al., 2019).

Screening

The review was conducted using Covidence systematic review software, which removed duplicate articles. Abstract screening was completed in duplicate by two independent reviewers with 93% agreement (TRH, BAC). Full-text articles were reviewed by a single author (TRH or BAC). A random selection of 20% of the reviewed full-text articles was reviewed by two authors (KA, SM) as a reliability check. Disagreements during abstract and full-text review were resolved in consensus by all authors. The included studies progressed to quality assessment and data extraction.

Quality Assessment

The quality of each study included was assessed using the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Critical Appraisal Checklist for Studies Reporting Prevalence Data (Joanna Briggs Institute, 2017). This tool was designed for systematic reviews and assesses the methodological quality of included studies with nine questions on the study design, conduct, and analysis. The questions were answered as Yes, No, or Unsure, and the total score was calculated. One reviewer (TRH) completed the critical appraisal of all studies, and 20% of the studies were assessed in pairs. Conflicts were resolved in consensus by all authors.

Data Extraction

We developed the data extraction tool, which was pilot tested with two studies by all authors. Extracted data included the country of study, publication year, journal of publication, objective, and study design. We also extracted information on the study setting, population characteristics, sampling technique, sample size, response rate, and reasons for non-response. For both mental health outcomes, we extracted details on the measurement tool, the data collection time point, and the prevalence estimates. When available, we extracted stratified prevalence estimates for demographic subgroups (e.g., parity, education status, income, race, age). One reviewer (TRH) completed the data extraction, with 20% of the studies done in pairs. Conflicts were resolved in consensus by all authors.

Analysis

Of the extracted data, information most relevant to the synthesis of prevalence data are presented in table. The prevalence rates and time point of assessment are narratively synthesized in table and text. We also narratively synthesized the prevalence of anxiety and depression by demographic subgroups in table and text. If the prevalence was reported as a fraction, the percentage calculation was performed by the author (TRH). No studies were excluded from the analysis based on the quality assessment score. We were unable to conduct a meta-analysis due to heterogeneity across studies for prevalence estimates. Since only one study measured incidence during the time-period of interest (Kothari et al., 2016), we were unable to narratively synthesize or discuss trends in incidence rates. Therefore, our results are strictly focused on point and period prevalence data.

Results

Characteristics of Included Studies

Figure 1 shows the PRISMA diagram of included studies. The literature search yielded 249 citations. After duplicate removal, abstract review, and full-text review, 21 studies were included for analysis. The key characteristics of the 21 included studies are summarized in Table 1. This includes the country of origin, study design, study setting, methods, sample size, and prevalence and incidence outcomes.

Included studies were from 14 countries, with eight from the USA. According to The World Bank Group (2021), four cohorts were identified from lower-middle-income countries, two from upper-middle-income countries, and 15 from high-income countries. Sixteen studies used a prospective cohort design and five studies were cross-sectional surveys. Regarding study setting, seven studies were conducted in a clinical setting (e.g., recruitment from hospitals or primary care centers), five were population-based, three were conducted online, three involved birth cohorts, and three were conducted in both community and clinical settings. All 21 studies assessed depression and four assessed both depression and anxiety (Table 1).

The most common measurement tool used to assess depression was the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS; n = 8), followed by the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CESD; n = 5), Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ; n = 3), Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II; n = 2), Hopkins Symptom Checklist-25 (HSCL-25; n = 1), Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI; n = 1), and International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM; n = 1). Regarding anxiety, measurement tools included the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7; n = 2) and the Spielberger State Anxiety Inventory (SSAI; n = 1). One study used a condensed version of the HSCL (SCL-8), which assesses anxiety and depression. Regarding the method of survey administration, 13 studies administered these tools as self-reported questionnaires and six studies administered these tools via interviews. One study evaluated two separate cohorts with the EPDS; however, the EPDS was administered as an interview in the first cohort and as a self-reported measure in the second cohort (Matijasevich et al., 2009). Finally, one study diagnosed depression by board-certified psychiatrists (Chen et al., 2020) (Table 1).

The quality assessment of included studies using the JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist is summarized in Table 2. The quality ratings ranged from three to nine (out of nine). Most studies had scores equal to or greater than seven (n = 14). The most common reasons for failing to meet the checklist criteria included a lack of drop-out analysis (Q5), limited sample frame (Q1), and lack of reported denominator values or confidence intervals for prevalence estimates (Q8).

Prevalence of Depression 1 to 12 Years Post-childbirth

Twenty-one studies assessed the prevalence of depression and include 31 total time points of measurement beyond the first postpartum year. The prevalence of depression ranged from 6.6% measured at 3 to 11 years post-childbirth (Chen et al., 2020) to 41.4% measured at 3 to 4 years post-childbirth (Leiferman et al., 2021).

There were 14 estimates of depression prevalence within or including the second postpartum year, ranging from 7.0 to 30.8% (Adhikari et al., 2022; Chi et al., 2016; Guo et al., 2014; Hahn-Holbrook et al., 2013; Horwitz et al., 2007; Kothari et al., 2016; Matijasevich et al., 2009; Mayberry et al., 2007; Reay et al., 2011; Schmidt et al., 2006; Woolhouse et al., 2015; Ystrom et al., 2014). The prevalence within or including the third year was reported five times, ranging from 12.4 to 31.8% (Adhikari et al., 2022; Chi et al., 2016; Civic & Holt, 2000; Manuel et al., 2012; Ystrom et al., 2014). In the fourth postpartum year, depression prevalence was reported four times, ranging from 13.5 to 41.4% (Abdollahi & Zarghami, 2018; Leiferman et al., 2021; Schmidt et al., 2006; Woolhouse et al., 2019). There were four estimates of depression prevalence within or including the fifth postpartum year, ranging from 8.5 to 32.6% (Adhikari et al., 2022; Hall, 1990; Manuel et al., 2012; Ystrom et al., 2014). The prevalence at 8 years was reported once at 18.6% (Adhikari et al., 2022). Other prevalence measurements included 6.6% between 3 and 11 years (Chen et al., 2020) and 17.6% between 1 and 10 years (Wulsin et al., 2010). Finally, one study of women with children 12 years of age reported the prevalence of depression as 21.5% (Agnafors et al., 2013). These results are summarized in Table 1.

Seven studies analyzed the prevalence of depression at multiple time points beyond the first-year post-childbirth. Chi et al. (2016) reported a slight increase in depression prevalence from the second to third year post-childbirth from 30.8 to 31.8%. Mayberry et al. (2007) found an increase between 13–18 months and 19–24 months from 17.1 to 20.4%. Adhikari et al. (2022) also demonstrated an increase between 2 and 8 years post-childbirth from 12.5 to 18.6%. Two studies reported a decrease in depression prevalence: (1) 23.6 to 21.1% from 2 to 4 years (Schmidt et al., 2006); and (2) 21 to 17% from 3 to 5 years (Manuel et al., 2012).

Prevalence of Depression in Socio-demographic Subgroups

The prevalence of depression in multiple socio-demographic subgroups is reported in Table 3. Four studies reported the prevalence of depression in ethnic subgroups. The greatest difference in depression prevalence between ethnic subgroups was reported by Hall (1990), with 41.2% of Black women and 21.4% of white women reporting depressive symptoms at 5 to 6 years post-childbirth (Table 3).

Three studies reported the prevalence of depression in income subgroups. The greatest difference in depression prevalence between the highest and lowest recorded income subgroups was found in a Brazilian cohort. At 24 months post-childbirth, 22.7% of women in the first family income quintile reported depressive symptoms, compared to 8.9% of women in the fifth family income quintile (Matijasevich et al., 2009). In all studies that reported the prevalence of depression in subgroups based on income, a higher prevalence was found in women of lower income compared to higher income (Table 3).

Three studies reported the prevalence of depression in subgroups based on marital status. Consistently, the prevalence of depression was lower in married women compared to single or divorced women. For instance, Hall (1990) found at 5 to 6 years post-childbirth, depressive symptoms were reported by 33.3% of never married women, 31.1% of divorced or separated women, and 24.8% of married women. The prevalence of depression in women with > 12 years of education ranged from 15.2% (measured at 5 to 6 years) (Hall, 1990) to 19.9% (measured at 3 years) (Manuel et al., 2012). In women 1 to 10 years post-childbirth, 16.2% of those living in a rural area and 18.8% of those living in an urban area reported depressive symptoms (Wulsin et al., 2010). Furthermore, Hall (1990) found that at 5 to 6 years post-childbirth, 33.8% of unemployed and 30.4% of employed women reported depressive symptoms (Table 3).

Finally, no association could be found between the income level of the country and depression prevalence. Both the highest and lowest prevalence estimates (6.6 to 41.4%) were found in high-income countries. Only six prevalence estimates came from low-income countries, ranging from 7.0 and 31.8%.

Prevalence of Anxiety 1 to 12 Years Post-childbirth

As shown in Table 1, four studies assessed the prevalence of anxiety and included nine total time points of measurement beyond 1 year post-childbirth. The prevalence of anxiety ranged from 3.7%, measured at 5 years (Ystrom et al., 2014), to 37%, measured at 3 to 4 years (Leiferman et al., 2021). Other prevalence estimates were 3.9% at 2 years (Guo et al., 2014), 5.1% at 1.5 years (Ystrom et al., 2014), and 5.8% at 3 years (Ystrom et al., 2014). None of the included studies reported the prevalence of anxiety by population subgroups.

Adhikari et al. reported an increasing prevalence of anxiety at four time points post-childbirth. The prevalence at 2, 3, 5, and 8 years post-childbirth was 15.4%, 15.2%, 16.4%, and 17.4%, respectively.

Discussion

The current systematic review identified 21 studies reporting the prevalence of depression and/or anxiety in women between 1 and 12 years post-childbirth. Only one study reported the incidence of depression. Prevalence estimates of depression were much more abundant, with 31 total estimates across 21 studies. The prevalence of depression ranged from 6.6 to 41.4%. There were nine prevalence estimates of anxiety across four studies, ranging from 3.7 to 37%. Overall, our results indicate a vast range of anxiety and depression prevalence estimates.

Five studies reported the prevalence of depression in demographic subgroups. The prevalence of depression varied in subgroups based on ethnic origin, but was as high as 41.2% in Black women and as low as 9.5% in white women. The prevalence of depression was consistently higher in women of lower income compared to higher income, ranging from 6.7% in women in the top family income quintile in England to 41.7% in American women with the lowest annual family income. The prevalence of depression was also consistently higher in unmarried women than in married women, ranging from 9.3% in married women to 33.3% in never married women.

Overall, the review findings show that maternal depression and anxiety remain prevalent years beyond the immediate postpartum period. It is essential for healthcare professionals, researchers, and policy makers to be aware of the chronicity of maternal anxiety and depression and its high prevalence in select subgroups, as this may assist in identifying high-risk women and inform prevention and intervention strategies. Current clinical practice focuses on the screening and treatment of women within the first postpartum year, highlighting a gap and opportunity to address maternal mental health beyond this period. Given our results, the extension of maternal mental health assessments and screening to beyond this period should be considered by those in primary care, especially since early management of maternal mental health problems can significantly improve child outcomes (Weissman et al., 2015). Moreover, stronger coordination between prenatal care and long-term mental health care is essential to ensure continuity of care for affected women into the late post-childbirth period.

It is also evident the lack of studies on the prevalence and incidence of anxiety beyond the first post-partum year. Since anxiety and depression are typically comorbid, a holistic understanding of maternal mental health is incomplete without additional studies about anxiety (Ross et al., 2003). We also identified a lack of studies assessing the incidence of depression and anxiety. Incidence is a stronger indicator than prevalence, since incidence indicates in which post-childbirth year women are most vulnerable to develop anxiety and depression symptoms, further informing targeted screening and prevention strategies. Future studies that assess depression and anxiety at multiple time points should likewise include documentation of incidence rates. Furthermore, there remains a lack of studies on women with older children. Older childhood is a unique developmental period also highly influence by present and previous exposure to parental depression and anxiety. For instance, adolescents who were exposed to postnatal depression in infancy may have impaired cognitive and psychosocial outcomes (Sanger et al., 2015) and adolescent depression is linked to concurrent exposure to maternal depression (Hammen et al., 2008).

Study population recruitment approaches may influence prevalence rates. The highest prevalence of anxiety and depression were both reported by Leiferman et al.. Participants were recruited through social media such as Facebook, Momforum.com, and Mothering.com. Similarly high results were reported by Chi et al. (2016), who distributed a questionnaire on multiple chat platforms popular among women after delivery. In the second and third postpartum years, they reported the prevalence of depression to be upwards of 30%. Women with depression or anxiety seeking help online may be more likely to participate in studies with online recruitment strategies. Alternatively, women who are social media users may be at higher risk of adverse mental health outcomes. The recruitment strategy should be carefully considered in future prevalence and incidence studies.

The method of questionnaire administration may influence prevalence rates. Generally, the studies that collected data via interview reported lower depression and anxiety estimates than those that used self-reported questionnaires. The Matijasevich et al. (2009) study evaluated two cohorts that used different administration methods– the ALSPAC cohort was administered a self-reported EPDS and the Pelotas cohort was administered the EPDS via in-home interviews. The lower prevalence of depression in Pelotas (9.9%) than ALSPAC (16%) may be partly explained by the difference in questionnaire delivery. Participants may be less likely to disclose socially undesirable mental health information in an interview environment (Locke & Gilbert, 1995; Richman et al., 1999). The method of questionnaire administration should be addressed by future studies.

A lack of or ineffective treatment of depression and anxiety after childbirth may explain its persistence through the early and middle childbearing years. Furthermore, psychotherapy in depressed women may improve parenting distress and child mental health, but may not improve maternal perceptions of or responsiveness to their child (Cuijpers et al., 2015; Forman et al., 2007). Information on whether women were receiving treatment for depression and anxiety would contextualize the prevalence rates and symptom persistence in future studies. While most of our included studies did not provide this information, Reay et al. (2011) found that the majority (63%) of women who were depressed prenatally or immediately postpartum received some type of treatment within the following 2 years. Additionally, Woolhouse et al. (2019) found that at 4 years post-childbirth, 13.9% of all women and 32.5% of women with depressive symptoms answered positively to psychotropic medication use within the past month.

A strength of this paper is that we systematically reviewed studies on the prevalence of anxiety and depression beyond 1 year post-childbirth, which, to our knowledge, is the first review in this regard. This paper offers extensive information on this topic, as previous systematic reviews in the field are focused on either anxiety or depression, prevalence or incidence, or the first postpartum year only (Dennis et al., 2017; Goodman, 2004; Goodman et al., 2016; Woody et al., 2017). The search strategies we used were comprehensive, as we consulted with librarians and other experts in the field. We further synthesized the findings with respect to the social determinants of health (e.g., race, income, education, urban/rural), which furthers our understanding of the women at higher risk for mental health problems.

A limitation of this review is that we limited studies to those published in English. The full-text review, study quality assessment, and data extraction were not done in pairs by the authors. This should not impact the quality of the review process because a portion of studies was reviewed by a second author, and consensuses were made by all authors. Finally, we were unable to quantitatively summarize or provide a pooled estimate of the prevalence of depression and anxiety using meta-analysis due to data limitations.

Conclusion

The current systematic review identified 21 studies reporting the prevalence of depression and anxiety in women between 1 and 12 years post-childbirth. We concluded that maternal anxiety and depression remain prevalent beyond the first postpartum year, particularly in marginalized demographic subgroups. These results may assist in identifying high-risk women and inform targeted prevention and intervention strategies. There remains a lack of research analyzing the incidence and prevalence of anxiety and depression. Future directions include more longitudinal and cross-sectional studies addressing this lack of studies. Moreover, current clinical practice, which is focused on the first postpartum year, should expand the scope of maternal mental health screening, prevention, and treatment beyond this period.

Data Availability

Data and materials of this systematic review can be obtained from the corresponding author.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

References

Abdollahi, F., & Zarghami, M. (2018). Effect of postpartum depression on women’s mental and physical health four years after childbirth. Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal, 24(10), 1002–1009. https://doi.org/10.26719/2018.24.10.1002

Adhikari, K., Racine, N., Hetherington, E., McDonald, S., & Tough, S. (2022). Women’s mental health up to eight years after childbirth and associated risk factors: Longitudinal findings from the all our families cohort in Canada. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1177/07067437221140387

Agnafors, S., Sydsjö, G., Dekeyser, L., & Svedin, C. G. (2013). Symptoms of depression postpartum and 12 years later-associations to child mental health at 12 years of age. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 17(3), 405–414. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-012-0985-z

Barthel, D., Kriston, L., Fordjour, D., Mohammed, Y., Kra-Yao, E. D., Kotchi, C. E. B., Armel, E. J. K., Eberhardt, K. A., Feldt, T., Hinz, R., Mathurin, K., Schoppen, S., Bindt, C., Ehrhardt, S., & Group, on behalf of the I. C. S. (2017). Trajectories of maternal ante- and postpartum depressive symptoms and their association with child- and mother-related characteristics in a West African birth cohort study. PLoS ONE, 12(11), e0187267. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0187267

Beck, C. T. (1992). The lived experience of postpartum depression: A phenomenological study. Nursing Research, 41(3), 166–170.

Bennett, I. M., Schott, W., Krutikova, S., & Behrman, J. R. (2016). Maternal mental health, and child growth and development, in four low-income and middle-income countries. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 70(2), 168–173. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2014-205311

Campbell, S. B., Brownell, C. A., Hungerford, A., Spieker, S. J., Mohan, R., & Blessing, J. S. (2004). The course of maternal depressive symptoms and maternal sensitivity as predictors of attachment security at 36 months. Development and Psychopathology, 16(2), 231–252. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579404044499

Chen, L.-C., Chen, M.-H., Hsu, J.-W., Huang, K.-L., Bai, Y.-M., Chen, T.-J., Wang, P.-W., Pan, T.-L., & Su, T.-P. (2020). Association of parental depression with offspring attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and autism spectrum disorder: A nationwide birth cohort study. Journal of Affective Disorders, 277, 109–114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.07.059

Chi, X., Zhang, P., Wu, H., & Wang, J. (2016). Screening for postpartum depression and associated factors among women in china: A cross-sectional study. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 1668. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01668

Civic, D., & Holt, V. L. (2000). Maternal depressive symptoms and child behavior problems in a nationally representative normal birthweight sample. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 4(4), 215–221. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1026667720478

Closa-Monasterolo, R., Gispert-Llaurado, M., Canals, J., Luque, V., Zaragoza-Jordana, M., Koletzko, B., Grote, V., Weber, M., Gruszfeld, D., Szott, K., Verduci, E., ReDionigi, A., Hoyos, J., Brasselle, G., & Escribano Subías, J. (2017). The effect of postpartum depression and current mental health problems of the mother on child behaviour at eight years. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 21(7), 1563–1572. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-017-2288-x

Collins, W. A., & Madsen, S. D. (2019). Parenting during middle childhood. Handbook of parenting (3rd ed.). Routledge.

Cuijpers, P., Weitz, E., Karyotaki, E., Garber, J., & Andersson, G. (2015). The effects of psychological treatment of maternal depression on children and parental functioning: A meta-analysis. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 24(2), 237–245. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-014-0660-6

Dennis, C.-L., Falah-Hassani, K., & Shiri, R. (2017). Prevalence of antenatal and postnatal anxiety: Systematic review and meta-analysis. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 210(5), 315–323. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.116.187179

Don, B. P., & Mickelson, K. D. (2012). Paternal postpartum depression: The role of maternal postpartum depression, spousal support, and relationship satisfaction. Couple and Family Psychology: Research and Practice, 1(4), 323–334. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029148

Fawcett, E. J., Fairbrother, N., Cox, M. L., White, I. R., & Fawcett, J. M. (2019). The prevalence of anxiety disorders during pregnancy and the postpartum period: A multivariate Bayesian meta-analysis. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 80(4), 1181. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.18r12527

Feldman, R., Granat, A., Pariente, C., Kanety, H., Kuint, J., & Gilboa-Schechtman, E. (2009). Maternal depression and anxiety across the postpartum year and infant social engagement, fear regulation, and stress reactivity. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 48(9), 919–927. https://doi.org/10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181b21651

Flynn, H. A., Davis, M., Marcus, S. M., Cunningham, R., & Blow, F. C. (2004). Rates of maternal depression in pediatric emergency department and relationship to child service utilization. General Hospital Psychiatry, 26(4), 316–322. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2004.03.009

Forman, D. R., O’hara, M. W., Stuart, S., Gorman, L. L., Larsen, K. E., & Coy, K. C. (2007). Effective treatment for postpartum depression is not sufficient to improve the developing mother–child relationship. Development and Psychopathology, 19(2), 585–602. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579407070289

Gaynes, B. N., Gavin, N., Meltzer-Brody, S., Lohr, K. N., Swinson, T., Gartlehner, G., Brody, S., & Miller, W. C. (2005). Perinatal depression: Prevalence, screening accuracy, and screening outcomes. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US).

Goodman, J. H. (2004). Postpartum depression beyond the early postpartum period. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic & Neonatal Nursing, 33(4), 410–420. https://doi.org/10.1177/0884217504266915

Goodman, J. H., Watson, G. R., & Stubbs, B. (2016). Anxiety disorders in postpartum women: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 203, 292–331. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2016.05.033

Guo, N., Bindt, C., Te Bonle, M., Appiah-Poku, J., Tomori, C., Hinz, R., Barthel, D., Schoppen, S., Feldt, T., Barkmann, C., Koffi, M., Loag, W., Nguah, S. B., Eberhardt, K. A., Tagbor, H., Bass, J. K., N’Goran, E., Ehrhardt, S., & The International CDS Study Group. (2014). Mental health related determinants of parenting stress among urban mothers of young children—Results from a birth-cohort study in Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire. BMC Psychiatry, 14(1), 156. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-14-156

Hahn-Holbrook, J., Haselton, M. G., Dunkel Schetter, C., & Glynn, L. M. (2013). Does breastfeeding offer protection against maternal depressive symptomatology?: A prospective study from pregnancy to 2 years after birth. Archives of Women’s Mental Health, 16(5), 411–422. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-013-0348-9

Hall, L. A. (1990). Prevalence and correlates of depressive symptoms in mothers of young children. Public Health Nursing, 7(2), 71–79. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1446.1990.tb00615.x

Hammen, C., Brennan, P. A., & Keenan-Miller, D. (2008). Patterns of adolescent depression to age 20: The role of maternal depression and youth interpersonal dysfunction. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 36(8), 1189–1198. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-008-9241-9

Hatton, D. C., Harrison-Hohner, J., Coste, S., Dorato, V., Curet, L. B., & McCarron, D. A. (2005). Symptoms of postpartum depression and breastfeeding. Journal of Human Lactation: Official Journal of International Lactation Consultant Association, 21(4), 444–449. https://doi.org/10.1177/0890334405280947

Horwitz, S., Briggs-Gowan, M. J., Storfer-Isser, A., & Carter, A. S. (2007). Prevalence, correlates, and persistence of maternal depression. Journal of Women’s Health, 16(5), 678–691. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2006.0185

Joanna Briggs Institute. (2017). The Joanna Briggs institute critical appraisal tools for use in JBI systematic reviews: Checklist for prevalence studies. https://jbi.global/sites/default/files/2019-05/JBI_Critical_Appraisal-Checklist_for_Prevalence_Studies2017_0.pdf

Kothari, C., Wiley, J., Moe, A., Liepman, M. R., Tareen, R. S., & Curtis, A. (2016). Maternal depression is not just a problem early on. Public Health, 137, 154–161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2016.01.003

Leiferman, J. A., Jewell, J. S., Huberty, J. L., & Lee-Winn, A. E. (2021). Women’s mental health and wellbeing in the interconception period. MCN the American Journal of Maternal Child Nursing, 46(6), 339–345. https://doi.org/10.1097/nmc.0000000000000767

Liu, X., Wang, S., & Wang, G. (2022). Prevalence and risk factors of postpartum depression in women: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 31(19–20), 2665–2677. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.16121

Locke, S. D., & Gilbert, B. O. (1995). Method of psychological assessment, self-disclosure, and experiential differences: A study of computer, questionnaire, and interview assessment formats. Journal of Social Behavior and Personality, 10(1), 255–263.

Manuel, J. I., Martinson, M. L., Bledsoe-Mansori, S. E., & Bellamy, J. L. (2012). The influence of stress and social support on depressive symptoms in mothers with young children. Social Science & Medicine, 75(11), 2013–2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.07.034

Matijasevich, A., Golding, J., Smith, G. D., Santos, I. S., Barros, A. J., & Victora, C. G. (2009). Differentials and income-related inequalities in maternal depression during the first two years after childbirth: Birth cohort studies from Brazil and the UK. Clinical Practice and Epidemiology in Mental Health: CP & EMH, 5, 12. https://doi.org/10.1186/1745-0179-5-12

Mayberry, L. J., Horowitz, J. A., & Declercq, E. (2007). Depression symptom prevalence and demographic risk factors among U.S. women during the first 2 years postpartum. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, and Neonatal Nursing: JOGNN, 36(6), 542–549. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1552-6909.2007.00191.x

McLearn, K. T., Minkovitz, C. S., Strobino, D. M., Marks, E., & Hou, W. (2006). The timing of maternal depressive symptoms and mothers’ parenting practices with young children: Implications for pediatric practice. Pediatrics, 118(1), e174–e182. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2005-1551

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., & Altman, D. G. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Annals of Internal Medicine, 151(4), 264–269. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135

Netsi, E., Pearson, R. M., Murray, L., Cooper, P., Craske, M. G., & Stein, A. (2018). Association of persistent and severe postnatal depression with child outcomes. JAMA Psychiatry, 75(3), 247–253. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.4363

O’hara, M. W., & Swain, A. M. (1996). Rates and risk of postpartum depression—A meta-analysis. International Review of Psychiatry, 8(1), 37–54. https://doi.org/10.3109/09540269609037816

Paulson, J. F., & Bazemore, S. D. (2010). Prenatal and postpartum depression in fathers and its association with maternal depression: A meta-analysis. JAMA, 303(19), 1961–1969. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2010.605

Priel, A., Zeev-Wolf, M., Djalovski, A., & Feldman, R. (2020). Maternal depression impairs child emotion understanding and executive functions: The role of dysregulated maternal care across the first decade of life. Emotion, 20(6), 1042–1058. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000614

Reay, R., Matthey, S., Ellwood, D., & Scott, M. (2011). Long-term outcomes of participants in a perinatal depression early detection program. Journal of Affective Disorders, 129(1–3), 94–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2010.07.035

Richman, W. L., Kiesler, S., Weisband, S., & Drasgow, F. (1999). A meta-analytic study of social desirability distortion in computer-administered questionnaires, traditional questionnaires, and interviews. Journal of Applied Psychology, 84, 754–775. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.84.5.754

Ross, L. E., Evans, S. E. G., Sellers, E. M., & Romach, M. K. (2003). Measurement issues in postpartum depression part 1: Anxiety as a feature of postpartum depression. Archives of Women’s Mental Health, 6(1), 51–57. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-002-0155-1

Ross, L. E., & McLean, L. M. (2006). Anxiety disorders during pregnancy and the postpartum period: A systematic review. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 67(8), 1175.

Sanger, C., Iles, J. E., Andrew, C. S., & Ramchandani, P. G. (2015). Associations between postnatal maternal depression and psychological outcomes in adolescent offspring: A systematic review. Archives of Women’s Mental Health, 18(2), 147–162. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-014-0463-2

Schmidt, R. M., Wiemann, C. M., Rickert, V. I., & Smith, E. O. (2006). Moderate to severe depressive symptoms among adolescent mothers followed four years postpartum. The Journal of Adolescent Health: Official Publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine, 38(6), 712–718. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.05.023

Shen, H., Magnusson, C., Rai, D., Lundberg, M., Lê-Scherban, F., Dalman, C., & Lee, B. K. (2016). Associations of parental depression with child school performance at age 16 years in Sweden. JAMA Psychiatry, 73(3), 239–246. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.2917

Slomian, J., Honvo, G., Emonts, P., Reginster, J.-Y., & Bruyère, O. (2019). Consequences of maternal postpartum depression: A systematic review of maternal and infant outcomes. Women’s Health, 15, 1745506519844044. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745506519844044

The World Bank Group. (2021). World Bank country and lending groups—World Bank Data help desk. https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups

Underwood, L., Waldie, K., D’Souza, S., Peterson, E. R., & Morton, S. (2016). A review of longitudinal studies on antenatal and postnatal depression. Archives of Women’s Mental Health, 19(5), 711–720. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-016-0629-1

Weissman, M. M., Wickramaratne, P., Pilowsky, D. J., Poh, E., Batten, L. A., Hernandez, M., Flament, M. F., Stewart, J. A., McGrath, P., Blier, P., & Stewart, J. W. (2015). Treatment of maternal depression in a medication clinical trial and its effect on children. American Journal of Psychiatry, 172(5), 450–459. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.13121679

Wenzel, A., Haugen, E. N., Jackson, L. C., & Robinson, K. (2003). Prevalence of generalized anxiety at eight weeks postpartum. Archives of Women’s Mental Health, 6(1), 43–49. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-002-0154-2

Woody, C. A., Ferrari, A. J., Siskind, D. J., Whiteford, H. A., & Harris, M. G. (2017). A systematic review and meta-regression of the prevalence and incidence of perinatal depression. Journal of Affective Disorders, 219, 86–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2017.05.003

Woolhouse, H., Gartland, D., Mensah, F., & Brown, S. J. (2015). Maternal depression from early pregnancy to 4 years postpartum in a prospective pregnancy cohort study: Implications for primary health care. BJOG: an International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 122(3), 312–321. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.12837

Woolhouse, H., Gartland, D., Papadopoullos, S., Mensah, F., Hegarty, K., Giallo, R., & Brown, S. (2019). Psychotropic medication use and intimate partner violence at 4 years postpartum: Results from an Australian pregnancy cohort study. Journal of Affective Disorders, 251, 71–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2019.01.052

Wulsin, L., Somoza, E., Heck, J., & Bauer, L. (2010). Prevalence of depression among mothers of young children in Honduras. International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine, 40(3), 259–271. https://doi.org/10.2190/PM.40.3.c

Ystrom, E., Reichborn-Kjennerud, T., Tambs, K., Magnus, P., Torgersen, A. M., & Gustavson, K. (2014). Multiple births and maternal mental health from pregnancy to 5 years after birth: A longitudinal population-based cohort study. Norsk Epidemiologi, 24(1–2), 1–2. https://doi.org/10.5324/nje.v24i1-2.1823

Funding

The authors received no funding for this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

TRH contributed to the implementation, literature search, data analysis, and writing. BAC contributed to the implementation and data analysis. KA and SM contributed throughout to the design, implementation, data analysis, and writing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

Ethical Approval

Not applicable.

Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Hunter, T.R., Chiew, B.A., McDonald, S. et al. The Prevalence of Maternal Depression and Anxiety Beyond 1 Year Postpartum: A Systematic Review. Matern Child Health J 28, 1283–1307 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-024-03930-6

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-024-03930-6