Abstract

Objectives

Despite Hispanics’ high prevalence of breastfeeding compared to other racial/ethnic groups, contributing factors remain unclear. This study examines the complex relationship among Hispanic nativity, acculturation, income, and breastfeeding.

Methods

The Fragile Families Child Wellbeing Study baseline (1998–2000) and Year 1 data (1999–2001) were used, including 4,077 women (933 non-Hispanic white, 2,046 non-Hispanic Black, 352 US-born Mexicans [USM], 299 US-born other Hispanics [USH], 302 foreign-born Mexicans [FBM], and 145 foreign-born other Hispanics [FBH]). Logistic regression estimated odds ratios(OR) and 95% confidence intervals(CI) for associations between Hispanic nativity and breastfeeding initiation and 4-month and 6-month breastfeeding, accounting for acculturation (Spanish language use, cultural engagement, religiosity, and traditional gender role attitudes), demographics, income, and health factors. Models were run for the overall sample and stratified by low vs. high income (above median: $21,600).

Results

FBM(OR:2.35, 95%CI 1.33,4.15) and FBH(OR:2.28, 95%CI 1.23,4.24) had higher odds, while USM(OR:0.55, 95%CI 0.41,0.73) and USH(OR:0.50, 95%CI 0.37,0.67) had lower odds of breastfeeding initiation, compared to white women. USM had lower odds of 4-month(OR:0.53, 95%CI 0.36,0.80) and 6-month breastfeeding(OR:0.38, 95%CI 0.23,0.63), as did USH for 4-month(OR:0.64, 95%CI 0.42,0.99) and 6-month breastfeeding(OR:0.50, 95%CI 0.30,0.85). In stratified models, low-income (vs. high-income) FBH had higher odds of breastfeeding initiation(OR:3.73 95%CI 1.43,9.75) and 4-month(OR:3.01 95%CI 1.12,8.04) and 6-month breastfeeding(OR:3.08 95%CI 1.07,8.88), yet effects of acculturation across income strata are inconsistent.

Conclusions for Practice

The Hispanic paradox operates differentially due to nativity, income, and acculturation. Breastfeeding intervention and promotion may require tailored approaches to Hispanic subgroups.

Significance

What is Already Known? The Hispanic paradox suggests Hispanic women have higher rates of breastfeeding initiation and longer duration than women of other racial/ethnic backgrounds, despite a relatively lower socioeconomic status. However, evidence of the Hispanic paradox in breastfeeding does not disaggregate Hispanic women by immigration and nativity, nor investigate the role of income.

What this Study adds? The Hispanic paradox in breastfeeding is present when disaggregating Hispanic women by immigration and nativity. Acculturation may be a more important predictor of breastfeeding among foreign-born Hispanic women, and low-income foreign-born women may be driving the Hispanic paradox in breastfeeding.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The Hispanic paradox refers to the phenomenon of Hispanic populations tending to show better health outcomes comparable to non-Hispanic white populations, despite their lower socioeconomic status (Franzini et al., 2001; McDonald et al., 2008). The Hispanic paradox is documented in preterm birth (Schaaf et al., 2013) and infant mortality (Mathews & Driscoll, 2017).

Breastfeeding provides mothers and infants a range of physical, psychological, economical, and environmental benefits (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2011). Data regarding breastfeeding initiation and duration is in line with the Hispanic paradox, as Hispanic women have higher rates of breastfeeding initiation and duration than women from other racial/ethnic groups, including white women of higher socioeconomic status (McKinney et al., 2016).

Acculturation, the process where immigrants’ values and lifestyles are modified when they come into contact with another culture, may be an important factor in the Hispanic paradox (Beck, 2006). Breastfeeding initiation rates were highest among immigrant women least acculturated to U.S. culture (Ahluwalia et al., 2012; Eilers et al., 2020; Harley et al., 2007; Kimbro et al., 2008; Sebastian et al., 2019; Singh et al., 2007). For instance, Mexican immigrants’ low level of acculturation accounted for Mexican immigrants’ higher breastfeeding initiation and longer breastfeeding duration than Mexican American and white mothers (Kimbro et al., 2008). Strong adherence to Hispanic cultural values, or low level of acculturation to the U.S., could promote positive health outcomes among Hispanics (Almeida et al., 2009).

Despite current evidence regarding acculturation and breastfeeding, Bigman et al. (2018) identified areas for future research: (1) disaggregation of Hispanic communities by acculturation, country of origin, and immigration status, (2) multidimensional approach to measuring acculturation, and (3) empirical focus on six-month breastfeeding duration. Moreover, Bigman et al. (2018) concluded that, “higher acculturation leads to lower breastfeeding rates, and it appears that this association is independent of income levels” (p. 1275). Yet, low socioeconomic status, especially among foreign-born Hispanic women in the U.S., may lead to low levels of assimilation and reliance on traditional breastfeeding practices (Franzini et al., 2001).

This study addressed knowledge gaps regarding the Hispanic paradox of breastfeeding by testing three hypotheses: (1) The Hispanic paradox in breastfeeding extends to non-Mexican Hispanic women; (2) Multidimensional acculturation accounts for greater proportion of odds of breastfeeding among foreign-born Hispanic women than U.S.-born counterparts; and (3) Foreign-born status and low levels of acculturation are stronger predictors of breastfeeding among low-income women than high-income women. Examining the complex relationship among Hispanic nativity, acculturation, income, and breastfeeding suggested by Bigman et al. (2018), this study advances the Hispanic paradox literatures.

Methods

Research Design

Data were extracted from the Fragile Families & Child Wellbeing Study (FFCWS) baseline and Year 1 data responded by mothers only. The FFCWS baseline and Year 1 data were selected because of its comprehensive data regarding breastfeeding and socio-cultural, psychological, and health characteristics among Hispanic nativity groups. FFCWS is a longitudinal cohort study of nearly 5,000 children born between 1998 and 2000 and their parents. Baseline data (1998–2000) were collected within 48 h of birth, and Year 1 data were collected approximately one year later (1999–2001). The FFCWS was approved by participating institutions, and the current analysis was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the authors’ institution.

Sample

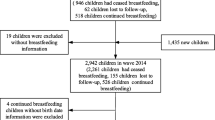

Of 4,898 mothers in the baseline survey, 4,364 mothers completed the Year 1 survey (Bendheim-Thoman Center for Research on Child Wellbeing, 2008). Among those 4,364 mothers, 4,108 identified as one of six Hispanic nativity groups (i.e., non-Hispanic white (NHW), non-Hispanic Black (NHB), US-born Mexicans (USM), US-born other Hispanics (USH), foreign-born Mexicans (FBM), and foreign-born other Hispanics (FBH)). Complete-case analysis included 4,077 mothers for the breastfeeding initiation analysis, and 2,062 mothers for the 4-month and 6-month breastfeeding duration analysis. Given the low number of missing variables, complete-case analysis was deemed appropriate. No power analysis was conducted as prior studies of breastfeeding using FFCWS data restricted the sample to 2,000 participants and estimated odds ratios up to 3.84 (Kimbro et al., 2008). We determined our minimum sample size of 2,062 participants was sufficient.

Measurement

Breastfeeding Initiation and Duration

Breastfeeding initiation was measured in Year 1 survey by asking the following yes/no question: “Did you ever breastfeed (CHILD)?” Breastfeeding duration was measured in Year 1 survey with the following question: “How old was (CHILD) when you stopped breastfeeding (him/her)?” Responses were recorded as months, recoded into two dichotomous variables: breastfeeding for four months (≥ 4 months vs. < 4 months) and for six months (≥ 6 months vs. < 6 months). Breastfeeding for six months is recommended (American Academy of Pediatrics, 2012), yet breastfeeding for four months may reduce the incidence of asthma and eczema among infants (Ip et al., 2007).

Hispanic Nativity Groups

Six Hispanic nativity groups were created based on race/ethnicity (white, Black/African-American, Asian/Pacific Islander, American Indian/Eskimo/Aleut, Other/not specified), Hispanic heritage (Mexican/Mexican-American and other Hispanics—Puerto Rican, Cuban, and Other Hispanic/Latino), and nativity measuring whether participants were born in the United States. A total of 4,077 mothers included in the analytic sample consisted of 933 non-Hispanic white (NHW), 2,046 non-Hispanic Black (NHB), 352 US-born Mexicans (USM), 299 US-born other Hispanics (USH), 302 foreign-born Mexicans (FBM), and 145 foreign-born other Hispanics (FBH). 256 women who identified themselves as Asian/Pacific Islander, American Indian/Eskimo/Aleut, or Other/not specified were not included in analyses similar to previous studies (Kimbro et al., 2008).

Acculturation

Acculturation consists of four variables measured in the FFCWS (Driver & Shafeek Amin, 2019; Kimbro et al., 2008): Spanish language use (yes, no), which was based on use of the Spanish language survey. Cultural engagement was determined by summing two 4-point scales, ranging from “strongly disagree (1)” to “strongly agree (4)”: “I feel an attachment towards my ethnic heritage” and “I participate in cultural practices of my own group, such as special food, music, or customs.” Low vs. high categories were based on the median cultural engagement value of 6. Adherence to traditional gender role was quantified by summing two 4-point scales, ranging from “strongly disagree (1)” to “strongly agree (4)”: “It is much better for everyone if the man earns the main living and the woman takes care of the home and family” and “The important decisions in the family should be made by the man of the house.” Low vs. high categories were based on the median adherence to traditional gender role value of 4. Religious service attendance was collected as four categories: never, a few times per year, a few times per month, and once a week or more.

Socioeconomic Status

Socioeconomic status (SES) was measured by household income, using the median as cut-point: high ≥$21,600 vs. low <$21,600.

Covariates

Covariates were informed by existing literature: maternal age (continuous), marital status (married/romantically involved with the child’s father vs. not), number of children (one child vs. multiple children), mental health (diagnosed depression or anxiety vs. not diagnosed), partner/domestic abuse (yes, no), and substance use (smoking, alcohol use, or drug use during pregnancy vs. no substance use at all during pregnancy) (Gibson-Davis & Brooks-Gunn, 2007; Kimbro, 2006; Pilkauskas, 2014; Silverman et al., 2006; Wouk et al., 2017).

Data Analysis

Descriptive analyses were obtained overall and by Hispanic nativity. Logistic regression models estimated odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for the association between Hispanic nativity groups and breastfeeding initiation and 4-month and 6-month breastfeeding. First, models included maternal demographic and health factors. Next, acculturation was included in the model. Fully adjusted models included household income. To test effect modification by income, interaction terms for each Hispanic nativity group*income and acculturation*income were included in models. If the p-value for an interaction term was ≤ 0.20, we interpreted it as a significant interaction term, suggesting the association between Hispanic nativity and breastfeeding or acculturation and breastfeeding differed by income. Power for interaction terms is lower than power for main effects, and higher thresholds for interaction p-values has been used in prior epidemiologic investigations (Hall et al., 2005; Kwan et al., 2004; Sansbury et al., 2005; Selvin, 2004; Williams et al., 2021). If any interaction terms were statistically significant, models were stratified by income. All analyses were completed with SPSS version 26.

Results

Table 1 presents the prevalence of breastfeeding outcomes and maternal characteristics, overall and by Hispanic nativity group. Breastfeeding initiation was highest among FBH (87%), followed by FBM (86.1%), NHW (67.4%), USM (55.5%), USH (53%), and NHB (44.8%) (p < .01). FBH and FBM also had the highest prevalence of 4-month and 6-month breastfeeding compared to other Hispanic nativity groups (p < .01). Foreign-born Hispanic women had lower levels of acculturation, compared to US-born counterparts. For income, 77.6% of NHW and 50.4% of USM were in the high-income group, while less than 50% of all other Hispanic nativity groups were in the high-income group (p < .01).

H1: The Extension of the Hispanic Paradox in Breastfeeding to non-Mexican Hispanic Women

For breastfeeding initiation, compared to NHW, USM (OR = 0.55, 95%CI 0.41,0.73) and USH (OR = 0.50, 95%CI 0.37,0.67) had lower odds of breastfeeding initiation, while the odds were higher among FBM (OR = 2.35, 95%CI 1.33,4.15) and FBH (OR = 2.28, 95%CI 1.23,4.24) (Model 3, Table 2).

For 4-month breastfeeding, compared to NHW, USM (OR = 0.53, 95%CI 0.36,0.80) and USH (OR = 0.64, 95%CI 0.42,0.99) had lower odds of 4-month breastfeeding. FBH (OR = 1.70, 95%CI 0.97,2.96) and FBM (OR = 1.14, 95%CI 0.67,1.94) had higher odds of 4-month breastfeeding, yet confidence intervals were wide.

For 6-month breastfeeding, compared to NHW, USM (OR = 0.38, 95%CI 0.23,0.63) and USH (OR = 0.50, 95%CI 0.30,0.85) had lower odds of 6-month breastfeeding. Results suggest FBH (OR = 1.57, 95%CI 0.89,2.78) and FBM (OR = 1.29, 95%CI 0.74,2.24) had higher odds of 6-month breastfeeding compared to NHW, yet estimates were not precise.

H2: Multidimensional Acculturation Accounting for Breastfeeding more for foreign-born Women

For breastfeeding initiation, when acculturation was added (Model 2, Table 2), odds of breastfeeding initiation decreased by 11% among USM (OR = 0.50, 95%CI 0.38,0.66), 9% among USH (OR = 0.45, 95%CI 0.34,0.61), 22% among FBM (OR = 2.06, 95%CI 1.18,3.60), and 24% among FBH (OR = 2.08, 95%CI 1.12,3.85) compared to Model 1. In addition, compared to no religious participation, yearly (OR = 1.42, 95%CI 1.15,1.76), monthly (OR = 1.42, 95%CI 1.12,1.79), and weekly (OR = 1.70, 95%CI 1.35,2.12) religious participation and high cultural engagement (OR = 1.39, 95%CI 1.20,1.61) were associated with higher odds of breastfeeding initiation (Model 3, Table 2).

For 4-month breastfeeding outcome, when models were adjusted for acculturation (Model 2, Table 2), odds of 4-month breastfeeding stayed the same for USM (OR = 0.55, 95%CI 0.37,0.82), increased by 3% for USH (OR = 0.66, 95%CI 0.43,1.01), but decreased by 8% for FBH (OR = 1.71, 95%CI 0.98,2.99) and 13% for FBM (OR = 1.16, 95%CI 0.68,1.97). Moreover, weekly religious participation (OR = 1.62, 95%CI 1.16,2.26) was associated with higher odds of 4-month breastfeeding (Model 3, Table 2).

For 6-month breastfeeding outcome, after the introduction of acculturation (Model 2, Table 2), odds of 6-month breastfeeding decreased by 3% for USM (OR = 0.35, 95%CI 0.21,0.58), but increased by 4% for USH (OR = 0.47, 95%CI 0.28,0.79) compared to Model 1. The odds of 6-month breastfeeding decreased by 8% for FBH (OR = 1.51, 95%CI 0.86,2.67) and 4% for FBM (OR = 1.21, 95%CI 0.70,2.10) compared to Model 1. In addition, weekly religious participation (OR = 1.62, 95%CI 1.11,2.35) increased the odds of 6-month breastfeeding (Model 3, Table 2).

H3: Foreign-born Status and low Acculturation as Stronger Predictors of Breastfeeding for low-income Women

In models stratified by income (Table 3), low-income USM (OR = 0.98, 95%CI 0.63,1.54) were more likely to initiate breastfeeding than high-income USM (OR = 0.39, 95% CI 0.27,0.57) (interaction p < .01). Similarly, low-income USH (OR = 0.73, 95% CI 0.45,1.18) showed higher odds of breastfeeding initiation than high-income USH (OR = 0.44, 95% CI 0.29,0.66) (interaction p = .07). Low-income FBM (OR = 2.61, 95% CI 1.13,6.06) had higher odds of breastfeeding initiation than high-income FBM (OR = 2.11, 95% CI 0.96,4.66), yet the interaction p-value (interaction p = .71) was high. Similarly, low-income FBH (OR = 3.73, 95% CI 1.43,9.75) had higher odds of breastfeeding initiation than high-income FBH (OR = 1.97, 95% CI 0.86,4.53), yet interaction p-value (interaction p = .32) was high. Spanish language use was a stronger predictor of breastfeeding initiation among low-income women (OR = 2.35, 95% CI 1.10,5.02) than high-income women (OR = 0.52, 95% CI 0.25,1.07) (interaction p = .01).

For the 4-month breastfeeding outcome, low-income USH (OR = 1.21, 95% CI 0.57,2.56) were more likely to breastfeed their child for four months than high-income USH (OR = 0.49, 95% CI 0.27,0.91) (interaction p = .05). Similarly, low-income FBH (OR = 3.01, 95% CI 1.12,8.04) had higher odds of breastfeeding their child for four months compared to high-income FBH (OR = 1.54, 95% CI 0.73,3.23), yet interaction p-value was high (interaction p = .25). High cultural engagement showed a stronger association with 4-month breastfeeding among low-income women (OR = 1.43, 95% CI 1.06,1.95) than high-income women (OR = 0.92, 95% CI 0.71,1.20) (interaction p = .04).

For the 6-month breastfeeding outcome, low-income USH (OR = 0.97, 95% CI 0.39,2.42) showed higher odds of 6-month breastfeeding than high-income USH (OR = 0.41, 95% CI 0.20,0.86) (interaction p = .12). Low-income FBH (OR = 3.08, 95% CI 1.07,8.88) also showed higher odds of 6-month breastfeeding than high-income FBH (OR = 1.31, 95% CI 0.61,2.80) (interaction p = .16). High cultural engagement showed a stronger association with 6-month breastfeeding among low-income women (OR = 1.41, 95% CI 0.99,2.01) than high-income women (OR = 0.85, 95% CI 0.64,1.12) (interaction p = .04).

Discussion

In an effort to address knowledge gaps regarding acculturation and breastfeeding among Hispanics identified by Bigman et al. (2018), we tested three hypotheses regarding the Hispanic paradox in breastfeeding: (1) The Hispanic paradox in breastfeeding extends to non-Mexican Hispanic women; (2) Multidimensional acculturation accounts for greater proportion of odds of breastfeeding among foreign-born Hispanic women than U.S.-born counterparts; and (3) Foreign-born status and low levels of acculturation are stronger predictors of breastfeeding among low-income women than high-income women.

First, our observations support the notion that the Hispanic paradox extends to non-Mexican Hispanic women, as FBH had increased odds of all breastfeeding outcomes compared to NHW women. Odds of breastfeeding initiation and duration were also increased among FBM women, which is consistent with prior research (Eilers et al., 2020; Jones et al., 2015; Kimbro et al., 2008; Sebastian et al., 2019; Singh et al., 2007). Secondly, acculturation accounted for a greater amount of breastfeeding among FBH and FBM than among USM and USH, supporting previous studies (Bigman et al., 2018; Kimbro et al., 2008). Lastly, low-income women, regardless of nativity, had higher odds of all breastfeeding outcomes, and yet the interactions between income and acculturation were not consistent across breastfeeding outcomes.

Our findings demonstrate the Hispanic paradox in breastfeeding extends to non-Mexican Hispanic women by identifying various Hispanic nativity groups (Eilers et al., 2020; Kimbro et al., 2008). Prior research has largely compared Mexican-origin Hispanics with non-Hispanic white or Black groups (Bigman et al., 2018). Despite the well-acknowledged heterogeneity of an aggregated Hispanic population (Anderson et al., 2004; Jones et al., 2015) and differences by nativity in adverse perinatal outcomes among Hispanic women (Montoya-Williams et al., 2021), non-Mexican Hispanics have largely been understudied (Centers for Disease Control & Prevention, 2010, 2020). This exploratory analysis provides initial data regarding the Hispanic paradox in breastfeeding among the heterogenous population of Hispanics in the U.S., and we encourage additional investigation of these differences.

Our results are similar among FBH and FBM, however, suggesting nativity may be more important than country of origin in regard to acculturation. In all analyses, weekly religious service attendance was the acculturation variable with the strongest positive association with breastfeeding initiation and 4-month and 6-month breastfeeding outcomes, similar to previous studies (Kimbro et al., 2008). Similar to prior research on religiosity and positive perinatal outcomes (Burdette & Pilkauskas, 2012), our result suggests that high levels of religious involvement, including weekly religious service attendance in collective worship, is associated with positive health behaviors (Page et al., 2009).

Despite the complex nature of acculturation construct (Beck, 2006; Hunt et al., 2004; Thomson & Hoffman-Goetz, 2009), prior research on the role of acculturation in breastfeeding focused on the use of Spanish language as the sole measure (Ahluwalia et al., 2012; Sebastian et al., 2019; Thomson & Hoffman-Goetz, 2009), except for one study that used the FFCWS data (Kimbro et al., 2008). Addressing measurement concerns regarding acculturation (Hunt et al., 2004; Thomson & Hoffman-Goetz, 2009), we incorporated various measures of acculturation, ranging from behavioral measures (e.g., religious service attendance) to social-psychological characteristics (e.g., cultural engagement). This conceptual richness allowed us to demonstrate that the degree to which Hispanics are acculturated to the American culture is not only dependent on language, but also frequency of religious participation, levels of cultural engagement, and traditional gender role perceptions. Opposed to creating an acculturation index, as some have recommended (Bigman et al., 2018), we kept acculturation variables separate, which allowed for identification of specific aspects of acculturation which may be more important than others. Independent of other acculturation factors, frequency of religious participation was most strongly associated with positive breastfeeding outcomes in overall and income-stratified analyses.

Within this sample of relatively low-income individuals (median income $21,600), results suggest that income may play an important role in breastfeeding outcomes. Apart from USM for the 6-month breastfeeding results, the odds of all breastfeeding outcomes were higher among low-income Hispanic women than among high-income Hispanic women. Although income is an explicit component of the Hispanic paradox, little research examined the role of income in the Hispanic paradox of breastfeeding. In fact, prior research has focused on one stratum (e.g., low-income women) only (Chapman & Perez-Escamilla, 2013). Additionally, the findings among NHB women also support the notion that low-income women may use breastfeeding to a greater degree than their high-income counterparts, and the importance of income in breastfeeding may extend across cultural backgrounds. Our findings suggest that the Hispanic paradox in breastfeeding may not uniformly apply to all Hispanic women and may depend on income level. Even within the relatively low-income sample of the FFCWS, the low-income stratum may be driving the Hispanic paradox in breastfeeding.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the role of acculturation in breastfeeding outcomes by income level, as prior studies included income as a covariate, not a variable of inquiry (Bigman et al., 2018). A review by Bigman et al. (2018) concluded acculturation operates uniformly across income levels regarding the Hispanic paradox and breastfeeding (Bigman et al., 2018). Our observations contrast Bigman et al.’s (2018) conclusions and suggest the effect of acculturation may differ by income level. However, the relationship between acculturation and breastfeeding differs across breastfeeding outcomes. For instance, the use of Spanish language is a stronger predictor of breastfeeding initiation among low-income women, yet use of Spanish language is a stronger predictor of 4- and 6-month breastfeeding among high-income women. Given our income cut point of $21,600 ($37,256 in 2022 U.S. dollars) (CPI Inflation Calculator, 2022), women who may be considered low income among the general U.S. population were likely included in the high-income stratum of our study. If the true effect of acculturation is stronger among low-income women, it suggests that low-income women may not have enough dispensable income that would allow them to adopt a new lifestyle or become highly assimilated to American culture (Franzini et al., 2001). Low-income may serve as the protective mechanism by which low-income women show high breastfeeding initiation and duration rates (Almeida et al., 2009).

The findings of this study provide implications for public health professionals to effectively promote breastfeeding education to women with different cultural backgrounds (Wright et al., 1997). Similar to previous efforts gearing toward low-income women (Mersky et al., 2021), the disaggregation of Hispanic communities by nativity and income level is warranted for breastfeeding promotion. For instance, the Hispanic paradox of breastfeeding was not observed among low-income USM and USH women, showing lower breastfeeding rates compared to their high-income and foreign-born counterparts. Instead of trying to directly reach out to USM and USH women to increase breastfeeding rates, opinion leaders, including FBM and FBH, could be used as an indirect source of breastfeeding promotion (Baker et al., 2013).

Limitations

Acculturation was measured at the individual-level due to the unavailability of family and community-level variables. The lack of statistically significant interaction terms and wide confidence intervals for some strata-specific results may be due to low statistical power. However, the considerable differences in odds ratios between the low- and high-income strata suggest a qualitatively important role of income in the Hispanic paradox. As country of origin is an important factor in acculturation (Beck, 2006), additional research is warranted among US-born and foreign-born respondents. Black Hispanic women were not included as a unique Hispanic nativity group due to small sample size. Future research should investigate the intersection of race and ethnicity among Hispanic women.

Conclusions

This study addressed knowledge gaps regarding acculturation and breastfeeding among Hispanic women in the U.S. (Bigman et al., 2018). Foreign-born Hispanics, including both Mexican and non-Mexican descendants, were more likely to breastfeed, whereas US-born Mexican and non-Mexican descendants were less likely to do so when compared with NHW. Furthermore, low-income Hispanic women were more likely to breastfeed their children and continue to breastfeed them for four or six months, compared to their high-income counterparts. The relationship between acculturation and breastfeeding may differ by income level, yet it is not consistent across breastfeeding outcomes potentially due to FFCWS being a relatively low-income sample. These findings contribute to the understanding of the interplay of income, acculturation, and nativity in the Hispanic paradox of breastfeeding.

Data Availability

The Fragile Families & Child Wellbeing Study (FFCWS) baseline and Year 1 data responded by mothers only were used for analyses and they are publicly available at https://opr.princeton.edu/archive/restricted/Default.aspx.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

References

Ahluwalia, I. B., Morrow, B., D’Angelo, D., & Li, R. (2012). Maternity care practices and breastfeeding experiences of women in different racial and ethnic groups: Pregnancy risk Assessment and Monitoring System (PRAMS). Maternal and Child Health Journal, 16(8), 1672–1678. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-011-0871-0.

Almeida, J., Molnar, B. E., Kawachi, I., & Subramanian, S. V. (2009). Ethnicity and nativity status as determinants of perceived social support: Testing the concept of familism. Social Science & Medicine, 68(10), 1852–1858. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.02.029.

American Academy of Pediatrics. (2012). Breastfeeding and the use of human milk. Pediatrics, 129(3), e827–e841.

Anderson, A. K., Damio, G., Himmelgreen, D. A., Peng, Y. K., Segura-Perez, S., & Perez-Escamilla, R. (2004). Social capital, acculturation, and breastfeeding initiation among puerto rican women in the United States. Journal of Human Lactation, 20(1), 39–45. https://doi.org/10.1177/0890334403261129.

Baker, J., Sanghvi, T., Hajeebhoy, N., Martin, L., & Lapping, K. (2013). Using an evidence-based approach to design large-scale programs to improve infant and young child feeding. Food Nutr Bull, 34(3 Suppl), 146–155. https://doi.org/10.1177/15648265130343S202.

Beck, C. T. (2006). Acculturation: Implications for perinatal research. MCN: The American Journal of Maternal/Child Nursing, 31(2), 114–120. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005721-200603000-00011.

Bendheim-Thoman Center for Research on Child Wellbeing (2008). Introduction to the Fragile Families Public Use Data: Baseline, One-Year, Three-Year, and Five-YearCore Telephone Datahttps://fragilefamilies.princeton.edu/sites/fragilefamilies/files/ff_public_guide_0to5.pdf.

Bigman, G., Wilkinson, A. V., Perez, A., & Homedes, N. (2018). Acculturation and Breastfeeding among hispanic american women: A systematic review. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 22(9), 1260–1277. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-018-2584-0.

Burdette, A. M., & Pilkauskas, N. V. (2012). Maternal religious involvement and breastfeeding initiation and duration. American Journal of Public Health, 102(10), 1865–1868. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2012.300737.

Centers for Disease Control & Prevention. (2010). Racial and ethnic differences in breastfeeding initiation and duration, by state - national immunization survey, United States, 2004–2008. Morbidity & Mortality Weekly Report, 59(11), 327–334.

Centers for Disease Control & Prevention (2020). Rates of Any and Exclusive Breastfeeding by Sociodemographics Among Children Born in 2017. https://www.cdc.gov/breastfeeding/data/nis_data/rates-any-exclusive-bf-socio-dem-2017.html

Chapman, D. J., & Perez-Escamilla, R. (2013). Acculturative type is associated with breastfeeding duration among low-income Latinas. Maternal and Child Nutrition, 9(2), 188–198. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1740-8709.2011.00344.x.

CPI Inflation Calculator (2022). CPI Inflation Calculator. Retrieved March 3 from https://www.officialdata.org/us/inflation/1998?amount=21600

Driver, N., & Shafeek Amin, N. (2019). Acculturation, Social Support, and maternal parenting stress among U.S. hispanic mothers [Article]. Journal of Child & Family Studies, 28(5), 1359–1367. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-019-01351-6.

Eilers, M. A., Hendrick, C. E., Perez-Escamilla, R., Powers, D. A., & Potter, J. E. (2020). Breastfeeding initiation, duration, and supplementation among mexican-origin women in Texas. Pediatrics, 145(4), https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2019-2742.

Franzini, L., Ribble, J. C., & Keddie, A. M. (2001). Understanding the hispanic paradox. Ethnicity & Disease, 11, 496–518.

Gibson-Davis, C. M., & Brooks-Gunn, J. (2007). The association of couples’ relationship Status and Quality with Breastfeeding initiation [Article]. Journal of Marriage & Family, 69(5), 1107–1117. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2007.00435.x.

Hall, I. J., Moorman, P. G., Millikan, R. C., & Newman, B. (2005). Comparative analysis of breast cancer risk factors among african-american women and white women. American Journal Of Epidemiology, 161(1), 40–51. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwh331.

Harley, K., Stamm, N. L., & Eskenazi, B. (2007). The effect of time in the U.S. on the duration of breastfeeding in women of mexican descent. Maternal And Child Health Journal, 11(2), 119–125. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-006-0152-5.

Hunt, L. M., Schneider, S., & Comer, B. (2004). Should “acculturation” be a variable in health research? A critical review of research on US Hispanics. Social Science & Medicine, 59(5), 973–986. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2003.12.009.

Ip, S., Chung, M., Raman, G., Chew, P., Magula, N., DeVine, D., & Lau, J. (2007). Breastfeeding and maternal and infant health outcomes in developed countries. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment, 153, 1–186.

Jones, K. M., Power, M. L., Queenan, J. T., & Schulkin, J. (2015). Racial and ethnic disparities in breastfeeding. Breastfeeding Medicine, 10(4), 186–196. https://doi.org/10.1089/bfm.2014.0152.

Kimbro, R. T. (2006). On-the-job moms: Work and breastfeeding initiation and duration for a sample of low-income women. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 10(1), 19–26. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-005-0058-7.

Kimbro, R. T., Lynch, S. M., & McLanahan, S. (2008). The influence of Acculturation on Breastfeeding initiation and duration for Mexican-Americans. Population Research and Policy Review, 27(2), 183–199. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-007-9059-0.

Kwan, M. L., Block, G., Selvin, S., Month, S., & Buffler, P. A. (2004). Food consumption by children and the risk of childhood acute leukemia. American Journal Of Epidemiology, 160(11), 1098–1107. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwh317.

Mathews, T. J., & Driscoll, A. K. (2017). Trends in Infant Mortality in the United States, 2005–2014.NCHS Data Brief(279),1–8.

McDonald, J. A., Suellentrop, K., Paulozzi, L. J., & Morrow, B. (2008). Reproductive health of the rapidly growing hispanic population: Data from the pregnancy risk Assessment Monitoring System, 2002. Maternal And Child Health Journal, 12(3), 342–356. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-007-0244-x.

McKinney, C. O., Hahn-Holbrook, J., Chase-Lansdale, P. L., Ramey, S. L., Krohn, J., & Reed-Vance, M. (2016). . Community Child Health Research, N. Racial and Ethnic Differences in Breastfeeding. Pediatrics, 138(2). https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2015-2388

Mersky, J. P., Janczewski, C. E., Lee, P., Gilbert, C., McAtee, R. M., C., & Yasin, T. (2021). Home visiting effects on breastfeeding and bedsharing in a low-income sample. Health Education & Behavior, 48(4), 488–495. https://doi.org/10.1177/1090198120964197.

Montoya-Williams, D., Williamson, V. G., Cardel, M., Fuentes-Afflick, E., Maldonado-Molina, M., & Thompson, L. (2021). The Hispanic/Latinx Perinatal Paradox in the United States: A scoping review and recommendations to Guide Future Research. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 23, 1078–1091. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-020-01117-z.

Page, R. L., Ellison, C. G., & Lee, J. (2009). Does religiosity affect health risk behaviors in pregnant and postpartum women? Maternal and Child Health Journal, 13(5), 621–632. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-008-0394-5.

Pilkauskas, N. V. (2014). Breastfeeding initiation and duration in coresident grandparent, mother and infant households. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 18(8), 1955–1963. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-014-1441-z.

Sansbury, L. B., Millikan, R. C., Schroeder, J. C., Moorman, P. G., North, K. E., & Sandler, R. S. (2005). Use of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs and risk of colon cancer in a population-based, case-control study of African Americans and Whites. American Journal Of Epidemiology, 162(6), 548–558. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwi248.

Schaaf, J. M., Liem, S. M., Mol, B. W., Abu-Hanna, A., & Ravelli, A. C. (2013). Ethnic and racial disparities in the risk of preterm birth: A systematic review and meta-analysis. American Journal of Perinatology, 30(6), 433–450. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0032-1326988.

Sebastian, R. A., Coronado, E., Otero, M. D., McKinney, C. R., & Ramos, M. M. (2019). Associations between Maternity Care Practices and 2-Month Breastfeeding Duration Vary by Race, ethnicity, and Acculturation. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 23(6), 858–867. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-018-02711-2.

Selvin, S. (2004). Statistical analysis of epidemiologic data. Oxford University Press.

Silverman, J. G., Decker, M. R., Reed, E., & Raj, A. (2006). Intimate partner violence around the time of pregnancy: Association with breastfeeding behavior. Journal of Women’s Health, 15(8), 934–940. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2006.15.934.

Singh, G. K., Kogan, M. D., & Dee, D. L. (2007). Nativity/immigrant status, race/ethnicity, and socioeconomic determinants of breastfeeding initiation and duration in the United States, 2003. Pediatrics, 119, S38-46. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2006-2089G

Thomson, M. D., & Hoffman-Goetz, L. (2009). Defining and measuring acculturation: A systematic review of public health studies with hispanic populations in the United States. Social Science & Medicine, 69(7), 983–991. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.05.011.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2011). The Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Support Breastfeedinghttps://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK52682/pdf/Bookshelf_NBK52682.pdf

Williams, A. D., Kanner, J., Grantz, K. L., Ouidir, M., Sheehy, S., Sherman, S., & Mendola, P. (2021). Air pollution exposure and risk of adverse obstetric and neonatal outcomes among women with type 1 diabetes. Environmental Research, 197, 111152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2021.111152.

Wouk, K., Stuebe, A. M., & Meltzer-Brody, S. (2017). Postpartum Mental Health and Breastfeeding Practices: An analysis using the 2010–2011 pregnancy risk Assessment Monitoring System. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 21(3), 636–647. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-016-2150-6.

Wright, A. L., Naylor, A., Wester, R., Bauer, M., & Sutcliffe, E. (1997). Using cultural knowledge in health promotion: Breastfeeding among the Navajo. Health Education & Behavior, 24(5), 625–639. https://doi.org/10.1177/109019819702400509.

Acknowledgements

The first author thanks Dr. Joonghwa Lee and Aaron Johnsen for their support.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: SK & AW; Formal analysis: SK & AW; Methodology: SK & AW; Supervision: AW; Writing - original draft: SK; Writing – review & editing: SK & AW.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest/Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethics Approval (include appropriate approvals or waivers)

Approved by the Institutional Review Board at the authors’ institution on December 11, 2020 (IRB number: IRB-202012-080).

Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, S., Williams, A.D. Roles of Income and Acculturation in the Hispanic Paradox: Breastfeeding Among Hispanic Women. Matern Child Health J 27, 1070–1080 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-023-03643-2

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-023-03643-2