Abstract

This article examines the effects of joint venture’s exploitative knowledge acquisition on its innovation performance under the contexts of joint venture-parent similarity in technology, industry and country. We suggest that there is an inverse U-shaped relationship between joint venture’s exploitative knowledge acquisition and innovation performance. Moreover, the moderating role of joint venture-parent similarity in technology and country are recognized and are hypothesized as positively moderate the effect of exploitative knowledge acquisition on innovation performance, but industrial similarity is recognized and hypothesized as negative moderator. Negative binomial regression was used to test the hypotheses in a panel data of 183 joint venture cases and the findings support our prediction. The results of this study can help reconciling contradictory findings from previous studies by demonstrating the potential impact of exploitative knowledge acquisition on innovation performance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Exploitative knowledge acquisition is thought to be essential for the growth of the firm. This exploitation firms may be alliance partners, direct competitors, suppliers, and firms from other industrial sectors (Yang and Steensma 2014). In recent years, researchers are increasingly aware that combining their own critical expertise with that of their joint venture partners may provide a competitive advantage (Flint et al. 2008; Paulraj et al. 2008). Joint venture relationship could create superior value by leveraging knowledge stemming from strategic partners with indirect or direct access to product markets, cutting edge technology and other sources of innovation advantage.

There is a broad consensus that exploration and exploitation are important for organizational learning and adaptation (Koza and Lewin 1998; Sidhu et al. 2007). Exploitation and exploration have been characterized as fundamentally different search modes. Organization learning can be defined as continuum, ranging from exploitation on the one hand to exploration on the other. Exploitive knowledge learning involves local search that builds on an industrial existing technological trajectory to improve innovation efficiency. Exploration has been characterized as pursuit of new knowledge and boundary-spanning search for discovery of new approaches to technologies or organizational knowledge, this type of knowledge learning is the ability of a organization to create new knowledge through recombination of knowledge across organizational domains and may produce path-breaking innovations that depart from existing technological paradigms (McGrath 2001; Benner and Tushman 2002; Miller et al. 2007). Innovation is anchored in both exploitation from its parents’ knowledge and other firms to generate new possibilities through exploration.

In the context of knowledge exploitation, joint ventures are formed when parent firms contribute resources to create a new entity. They are widely regarded as an efficient mechanism to facilitate the creation and acquisition of knowledge across borders in order to minimize the transaction costs associated with the acquisition and exchange of resources and knowledge. A joint venture that engages in an equity-relationship establishment with its parents has the opportunity to develop capacity through exploitation with that parents’ firm, assimilation of the new knowledge, and further utilize this new knowledge. Consequently, equity-relationship establishment have the potential to develop capabilities of joint ventures and increase innovation performance. Knowledge exploitation obtained from parents enhances the joint venture’s organizational innovation capability to respond to its technology environment, and presumably to innovation performance for the joint venture (Park et al. 2015).

Second, for those firms originating from equity relationship, the positive relationship should be particularly vulnerable to certain joint venture-parents similarity contingences and sensitive to specific joint venture characteristics. We explore joint venture-parent similarity as moderators of the performance effects on exploitative knowledge acquisition. Because inter-organization similarity has not the main focus of earlier research, researchers have not been able to uncover how joint venture-parent similarity may impact the performance consequences of exploitative knowledge acquisition. In this study, we also highlight the existing research gap around the moderating role of inter-organizational exploitative knowledge acquisition, critical for gaining external knowledge from parents, for its innovation. Several studies have analyzed the degree to which partners may benefit from the inter-organization similarity of their organizational cultures or the aligning of a set of legal and political systems. Technology similarity allows joint ventures to strategically align with parents to take advantage of knowledge exploitation and maximize capability development. However, the effect of inter-organizational similarity has received limited empirical attention as moderators of exploitative knowledge acquisition and even less so in a joint venture context. Therefore, we pose our second research question: What is the impact of organizational similarity on exploitative knowledge acquisition in a equity-relationship setting?

With the growing body of theoretical research and empirical studies addressing the issue of joint ventures as mechanisms for organizational learning (Kogut 1988; Hamel 1991), this stream of research has begun to address some of the important questions associated with how organizations exploit collaborate learning opportunities. However, the translation of the knowledge, following the exploitative knowledge acquisition, to superior performance requires more research (Zhan and Chen 2013). Little is known about the performance implications for joint venture’s ambidexterity learning form parent, but our current empirical examination intends to shed some light on this research topic. Based on the ambidexterity perspective of equity relationship, we expect a inverted-U relationship of exploitative knowledge acquisition and joint venture performance. Our research provides empirical evidence to support these arguments. The findings not only help to clarify the effect of joint venture’s learning ambidexterity in practice but also enrich our understanding of the uniqueness of joint venture established by equity relationship in strategic alliance. We believe that this is a topic of significant importance, yet has been under-researched.

Accordingly, the purpose of this paper explores the effects of joint venture’s exploitative knowledge acquisition on its innovation performance under the contexts of JV-Parent similarity in technology, industry and country. The rest of the paper is structured as follows. Section 2 considers the previous literature and sets out the hypotheses of this study. Section 3 is the methodology for the study. Section 4 presents the results of the empirical study in achieving the goals as those set out above. Conclusion and policy implication are provided in Sect. 5.

2 Background and hypotheses

2.1 Sourcing knowledge through FDI

Globalization, manifested by increasing interdependency among countries due to elimination of international trade and capital movement barriers, is often regarded as an evitable process of accreted social change beyond the control of any single state. After decades of debate, although scholars and practitioners have reached consensus on the benefits of free trade, the liberalization of capital movements still remains the most controversial and divergent issue of globalization (e.g., Alderson and François 2002; Fischer 2003; Stiglitz 2002), especially in the light of recent global financial crisis. Regulating capital movements was unanimously regarded as orthodox and correct before the 1970s, but as heretical in the 1980s and 1990s in both industrial and developing countries. Most research focuses on the impact of capital deregulation on firm performance, national economic growth, or income inequality, but pays little attention to its causes. The received wisdom has been that international capital deregulation is a diffusion process driven by international organizations like the International Monetary Fund as well as by the unilateral removal of U.S. capital controls to other countries, which was driven by interests of U.S. multinational enterprises (MNEs) and financial institutions (Simmons and Zachary 2004). However, research based on newly released archival documents casts doubt on this wisdom, arguing that a country’s domestic politics (especially in France) and the dynamics among MNEs, local businesses, and the state are vital to the country’s choice of capital deregulation (e.g., Abdelal 2007). Understanding a country’s domestic condition may help explain globalization, and complement the traditional international diffusion explanation. Indeed, Stiglitz (2002) argues that the failure to incorporate the characteristics of each country into the process of capital deregulation is at the root of globalization’s contemporary problems.

Two contrasting perspectives can be offered as explanations of capital deregulation based on a country’s domestic condition. Economic theories of regulation center on efficiency, which justifies capital deregulation on the grounds of either market failure (Pigou 1938) or government failure (Stigler 1971). Free movement of capital facilitates an efficient global allocation of value activities and allows resources to be used most productively. Most studies thus focus on the consequences of capital deregulation and infer the causes from its consequences. Yet, empirical results regarding the impacts of capital deregulation are mixed and inconclusive (see Kose et al. 2006 for an extensive review).

As an alternative, some scholars propose that capital deregulation is inherently a political process. They contend that the essence of capital deregulation is a power struggle, not the improvement of efficiency (Abdelal 2007; Simmons and Zachary 2004; Wilson 1980). Power is more than coercion; it is the ability to shape the way in which others view the world and their own interests. Power theorists have argued that the purpose of antitrust law in the U.S. was not to construct an efficient market (Perrow 2002), the evolution of corporate control was not driven by business efficiency (Fligstein 1990), and the variations of international corporate governance did not emerge from maximization of shareholder value. Instead, they all represent the legacy of power struggles. This perspective does not rely on assumptions about market efficiency, but rather views regulatory change as a contested terrain of conflicting interests.

FDI has grown in significance in recent years, becoming a predominant source of external finance for developing countries (Kose et al. 2006). There is also a strong presumption that FDI yields more benefits than other types of capital flows due to technology transfer and spillover effects. Nevertheless, the literature tends to focus on the effects of FDI deregulation rather than the causes, and on inward rather than outward FDI (Kose et al. 2006).

2.1.1 Internal organization of industry

Firms’ capacity to influence FDI regulation depends on both resources they collectively control and their capability to mobilize those resources. The capability to mobilize resources is determined by the degree to which firms can cooperate and coordinate their actions (Ingram and Rao 2004; McCarthy and Zald 1977). Cooperation is concerned with alignment of interests, and coordination with alignment of actions. The issue of cooperation in a movement arises due to lack of incentive to solve the free-riding problem inherent in collective actions; the issue of coordination arises from the interdependency of participants’ actions and outcomes. Although resources available to a movement potentially increase with the number of firms with a shared interest, so does the difficulty of coordination. As such, firms become more heterogeneous and it becomes harder for them to arrive at consensus toward collective actions. The smaller share of gains for each firm resulting from the increasing number of firms exacerbate the free-riding problem due to lack of incentive to contribute (Olson 1965). Indeed, the outcomes of movements depend upon solidarity and coordination of movement participants.

To realize mobilization potential resulting from resource availability, there must be a way to facilitate strategic leadership (Morris and Staggenborg 2004). A strategic leadership structure, or the organization of a group that can facilitate firms’ ability to initiate a movement and shape its processes, is critical to explaining why some movements with abundant resources failed where those with limited resources succeeded. As McCarthy and Zald (1977) have long argued, the internal organization of an industry can influence both the coordination of a variety of activities across firms and the tendency to be a free rider in collective actions by affecting each firm’s costs and benefits in its involvement in social movement activity.

The differential abilities to profit from a movement among firms are an important structural factor influencing the strategic leadership behavior. When the distribution of actor abilities is highly skewed, the problems with coordination and cooperation problems become less severe for two reasons. First, the clear identification of dominant and weaker firms helps settle the market order of firm behaviors, thereby reducing coordination failure. The firms with lower market shares often emulate dominant firms, since doing so is consistent with their interests (Scherer 1982). The relationship between concentration and coordination rests on solid empirical ground, as numerous studies have found a statistically significant relationship between the Herfindahl–Hirschman Index and prices. Second, facing the highly asymmetric distribution of actor abilities, large dominant firms are less susceptible to the free-riding problem. As Olson (1965) suggests, viewing the outcome of a movement as a collective good, smaller firms may see no incentive to provide the good. Yet, the good is more likely to be voluntarily provided by larger firms who find that their reward for contributing the good is easily outweighs the cost.

2.1.2 Resources available to and technology capabilities controlled by the state

An autonomous state can generate its own interests and policy preferences, and mobilize the resources to pursue them. The kinds of power vested in the state helps the state to influence the social behaviors of its constituents (Scott 2001). The state, however, distinguishes itself from organizations such as interest groups and corporations by monopolizing the potential for legitimate violence, its mandate to design rules that regulate the economy, and by being subject to different organizing principles and rules of political competition. More narrowly, the state has the privilege to formulate policy in favor of its interests and goals unless it faces significant challenges from civil society or corporations. The ability of the state to regulate an industry increases with the ratio of resources it controls to resources controlled by firms in the industry. Such a resource advantage confers upon the state the autonomy and ability to influence the private sector in accordance with its goals and to face conflicts with and grievances from challengers. The state can also use its technology capabilities and its joint R&D with private firms as policy instruments to affect private sectors.

2.2 Learning from parents: sourcing knowledge for innovation of joint ventures

Innovation is important source of firm’s competitive advantage, Innovation requires that firms continually acquire and develop new knowledge and skill. However, as the business environment changes so rapidly, a firm’s self-sufficiency in creating knowledge will bear tremendous risks and may not bring success. The sources of knowledge and the process of innovation are rarely confined within the boundaries of individual firms (Dodgson and Rothwell 1994). Innovation is such a complex and uncertain activity; it commonly requires the combination of knowledge from a multiplicity of sources, with the help of other firms can considerably improve the ability to learn knowledge for innovation (Inkpen and Dinur 1998; Glaister and Buckley 1996). Successful firms may not only rely on internal developments within their boundaries, but also choose to acquire knowledge and capabilities from other firms (Leonard-Barton and Sinha 1993; Leonard-Barton 1995).

Exploitation and exploration have been characterized as fundamentally different approaches to learning modes. With the growing body of theoretical research and empirical studies addressing the issue of exploration and exploitation for organizational learning, we identify three separate domains of exploration and exploitation that together describe an alliance, some studies have employed objective proxies for intra-organizational learning(He and Wong 2004; Atuahene-Gima 2005; Auh and Menguc 2005; Mc Namara and Baden-Fuller 2007; Groysberg and Lee 2009), or as the learning mechanism for inter-organization(Ahuja and Lampert 2001; Rosenkopf and Nerkar 2001; Uotila et al. 2009; Katila and Ahuja 2002; Holmqvist 2004; Sidhu et al. 2007; Wu and Shanley 2009). Others have used two constructs’ to evaluate learning between organizations with relationship (Rothaermel 2001; Rothaermel and Deeds 2004; Schildt et al.2005; Lavie and Rosenkopf 2006; Im and Rai 2008; Hill and Birkinshaw 2008), Such as corporate venturing, supply chain, strategic alliance and joint venture.

Joint ventures are distinctive in that they create competitive advantage by using a separate, shared organization to create, stored, and apply knowledge (Lane et al. 1998). Since equity arrangements are more difficult to dissolve, parents may align their interests and find themselves more embedded in joint venture relationship and hence become less opportunistic(Das and Teng 2000; Teng 2007). They have been regarded as the conduit for the flow of knowledge among the equity strategic alliance parents. Thus, the relationship between parents and joint venture is analogous to that of parents and a child: the child could learn quickly and effectively especially from the parents (Lyles and Salk 1996; Inkpen and Beamish 1997).

The important implication that follows is that joint venture has to reconcile two potentially conflicting tasks. On the one hand, joint ventures need to develop access to sources of knowledge from parents, as exploitating these sources yields a potential for the development of new innovation. On the other hand, they need to explore novel knowledge and absorb for their innovation (Cohen and Levinthal 1990). In other words, the creation of technological innovation implies a balancing this dual task for both exploitation and exploration, although it operates somewhat differently in each of the two learning sources. As pointed out by March (1991), knowledge exploration reflects an entrepreneurial search process for learning opportunities in technological areas that are new to joint ventures. Within the context of innovation, this entails expanding into new domains and yields technological innovations in areas that are novel to the joint venture. It entails non-parents innovation that determines joint venture’s continuity progress in the long run. In contrast, knowledge exploitation can be characterized as adding to the existing knowledge base from their parents and competence set of parents’ firms without changing the nature of their knowledge domains. In comparison with exploration, exploitation requires a deeper understanding of specific information and entails the deepening of a joint venture’s innovation generation in areas which its parents are familiar. It leads to further improvement in the core knowledge of their parents, which strengthens a joint venture’s existing innovation and enhancing its survivals and competiveness in the short term. Hence, a central concern of managing JV-Parent exploitative knowledge acquisition is the important source of innovation performance of the joint venture.

Knowledge base research addresses internal and external knowledge transfer (Cohen and Levinthal 1989, 1990; Kogut and Zander 1992, 1996; Grant 1996). Knowledge learning and flow occur by entities throughout cooperative systems. A knowledge based view on the firm provides insight as to how the level of organizational interdependence used to exploitative knowledge acquisition with parents may interact with some basic characteristics of knowledge to influence a joint venture’s innovation. With the growing body of theoretical research and empirical studies addressing the issue of exploitation and exploration as mechanisms for organizational learning, this stream of research has begun to address some of the inter-organizational relationship form associated with how organizations exploit and explore learning opportunities.

Despite a broad consensus concerning the importance of joint venture in cross-border knowledge exploitation with its parents, there is little empirical evidence of the innovation effectiveness of joint venture. Thus the premise of a knowledge based view and resource dependence theory induced our research explores how knowledge obtainment within a joint venture relationship depends upon exploitative knowledge acquisition under the contexts of JV-Parent similarity in technology, industry and country. Overall, this study integrated exploitation and exploration, JV-Parent similarity in technology, country and industry as different performance drivers into one comprehensive model and to explain the improvements in innovation performance of joint venture.

2.3 Exploitative knowledge acquisition and innovation performance

By viewing joint venture innovation creation through the lens of a learning perspective, the learning strategy becomes a key variable of interest. With joint venture focus on needed knowledge resource to innovative, resource dependence theory contributes to our understanding that when resources and competences are not readily or sufficiently available for joint ventures, they are more likely to established learning ties with their related parents (Pfeffer and Salancik 2003).

Exploitative knowledge acquisition refers to joint venture engaging in processes to transfer and learn from parents’ knowledge (Wu and Shanley 2009). It is associated with refining and extending existing competence; it has predictable returns, reduction of learning time and cost, and avoidance of potential experimentation mistakes (Wu and Shanley 2009). Joint ventures gaining from refinement of existing parents’ knowledge and learning from experience reduce transaction costs and thereby expedite to transfer and to be absorbed for learning-curve effect: (Child and Faulkner 1998). Joint venture and its parents’ interaction, by their very nature as social systems, is the environment in which learning take place. The joint venture permits the exploitation of knowledge with parent firms in the following way. The joint venture may be staffed by top executives from the various parent firms and strategic linkages, tacit knowledge can be shared (Inkpen 1995a, b). Thus, since these executes obviously retained their contacts with the parent organizations, Finally, exploitative knowledge acquisition can happen through interactive activities such as buying or transferring technology, observing and imitating technology used by the joint ventures (Berdrow and Lane 2003).

Path dependence in exploitative learning facilitates routine-based experiential learning. It increases its efficiency and likelihood of desirable outcome, which in turn further reinforce joint venture’s knowledge (Lavie and Rosenkopf 2006). The common elements of entrepreneurial innovation behavior in joint venture have to discover and pursue opportunities in an environment. As such, the parents play a critical role in creating an environment for joint venture that fosters exploitative knowledge acquisition and the development of innovation.

A joint venture’s knowledge exploitation to learn from parents appears as a necessary first step to initiate knowledge process of innovation creation. Knowledge exploitation from its parents is relatively easy to transfer and to be absorbed (Child and Faulkner 1998). Joint ventures typically exploit technology and knowledge assets from parents as their preferred strategy. The ability to exploit parents’ knowledge provides an incentive for joint venture’s higher returns to innovation.

The establishment of the joint venture relationship is likely to result in ease of coordination. The strategic control of technological development avoid unnecessary duplication of efforts and efficiently exploit available capabilities, and combine existing technological knowledge and find useful combinations (Katila and Ahuja 2002). The smooth communication for the information sharing and exchange is made easier by the joint venture and the parents through the exchange of information through various media. The knowledge domain could be better understood. It provides cues to joint ventures on how to act in an innovation context.

Exploitative knowledge acquisition could allow a joint venture to combine knowledge from parents with its internal knowledge, thereby restructuring its knowledge portfolios and achieving from the external and internal knowledge. Knowledge assimilation, combination, reconfiguration can assist a joint venture in realizing the potential value embedded in its parents’ knowledge base. Specifically, these knowledge management processes can broaden the focal joint venture’s view of understanding, upgrade its problem-solving ability, and further enhance innovation performance. More importantly, exploitative knowledge acquisition can grant the focal joint venture the benefits at extremely low cost. The relational capital for joint venture relationship facilitates close and repeated interaction and then breeds mutual commitment, reliability and faithfulness. Opportunistic behaviors would reduce and knowledge acquisition and sharing process can become more effectively.

Access to parent knowledge eases the constraints imposed on joint ventures by scarcity of internal resources (Katila and Ahuja 2002). Knowledge exploitative acquisition enhances the breadth and depth of relevant knowledge available to the joint venture and increases its willingness to explore new ideas and develop new innovation. As a joint venture learn along with its parents, they better understand each other’s needs, ensuring smooth operation in the equity-relationship system. These assimilation mechanisms take advantage of the pipeline of projects and ideas for improving the equity collaboration relationship. During this process, exploitative knowledge acquisition converts assimilated knowledge into action and thus propels superior performance in terms of innovation (Tsai 2001).

The joint venture at the initial stage invests in radical or breakthrough innovation by exploring outside its parents may achieve a certain degree of success, but limit their growth potential and put their survival at risk (Meyer and Roberts 1986; Day 1994). Conversely, by being first to recognize and exploit knowledge from parents for experimental innovation, joint venture can control the direction of the innovative progress to its competitive advantage (Tushman and Nadler 1986). Since joint ventures can perform a limited number of actions due to limited available resources, uncertainty, or bounded rationality, they tend to focus more on exploitation of parent’s knowledge in the early stage. Learning-from-parents by exploitation for a joint venture is likely to arise in the early stages and may represent a phase of experimentation before technology can engender understanding, or knowledge extend to know how.

Although the importance of knowledge exploitation from parents in the face of innovational, the relevance of parents’ contributors in the innovation process may change depending on whether the early or in the latter stage of innovation is considered. The pursuit of exploitation tends to focus on more certain innovational activities from parents. But when a group of knowledge is repeatedly used, the potential for future combinations among these knowledge sets become exhausted and diminished ability of joint ventures to conceive of new innovation (Fleming 2001; Kim and Kogut 1996). On the contrary, exploration enlarges a joint venture’s learning scope and gets access to different areas to bring more new knowledge elements. Thus the potential innovation can increase (Henderson and Cockburn 1994; Katila and Ahuja 2002).

When JV is well established and managed after a few years, it may be able to reduce its resource dependency over time through the superior learning process (Hamel 1991), and reliance on exploiting parents’ knowledge may result in missing opportunities to explore competitors and others new innovation advantages. The fact that the learning takes the form of imitation from parents’ might indicate some limitation in the quality and quantity of innovational process (Child and Markoczy 1993). Innovation provides joint venture with options for both exploiting parents’ knowledge or generating new possibilities through exploration in the moment (March 1991; Teece et al. 1997; Benner and Tushman 2002).

Too much reliance on exploitation forms competence traps and leads to core rigidity. Core rigidity originates from local search along a firm existing technological trajectory and from ignorance of external technological dynamics (Leonard-Barton 1995). When face with external technological change, the joint venture become more rigid, restrictive, and close dependent, rather than responsive (Makino and Inkpen 2003). The primary sources of core rigidities lie in the difficult-to-change nature of the JV-Parent innovation system suggest that obstacles to innovation are embedded barriers to changes. The failure to discard old dominant logics is one of the main reasons why joint ventures find it so difficult to change, even if they seen clear evidence of change in its environments (Bettis 1991; Miller et al. 2007).

Thus at high levels of exploitation, innovation opportunities to act entrepreneurially arise outside the parents’ knowledge reservoir. Joint ventures need to keep the balance between knowledge exploitation and exploration. Access to a broader knowledge base through exploring external learning and providing room for a new one increases the innovation and long-term competitive position of the joint venture (Grant 1996). External relationships such as suppliers, customers, and research institution are an important source of learning. They link with the technological community to maintain an open-ended social interaction and learning process, thus contribute to speed up innovation and also broaden the boundary of knowledge base for joint venture.

Building on the preceding arguments, this study predicts that exploitative knowledge acquisition between the joint venture and its parents are likely to have a nonmonotonic influence on the subsequent innovation performance of joint venture. Accordingly, we offer the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1

Exploitative knowledge acquisition has a curvilinear (inverted U-shaped) relationship with innovation performance of joint venture, with the slope positive at low levels of exploitative knowledge acquisition and negative at high levels of exploitative knowledge acquisition.

2.4 JV-Parent technology similarity, exploitative knowledge acquisition and innovation performance

Technology similarity is the extent of overlap in the fields of knowledge of the joint venture and its parents. Joint ventures are especially appealing when they provide strategic opportunities to gain access to technology resources that are not available within the boundaries of a firm. As such, Joint ventures can utilize equity-relationship learning mechanisms to acquire, manage, and create new knowledge from parent firms (Yao et al. 2013). Moreover, the knowledge exploitative acquisition and innovation creation process can be enabled by specific adaptation mechanisms, such as organizational similarity in technology, country and industry. These inter-organizational similarities enhance the joint venture’s ability to leverage parents’ knowledge, skills, and other valuable resources.

First, technology similarity in a JV setting brings in complementary knowledge bases that may be combined and integrated to create innovation value for joint venture. It is the extent of overlap in the fields of knowledge of the joint venture and its parents. Thus, technology similarity is defined as the joint venture technology portfolio in the same technology field with parents’. They are in the form of similar product development knowledge and skills, which comprise a large potential for learning and innovation creation through the combination of these existing technologies and knowledge resources. In other words, technology similarity emphasizes the knowledge synergies that exist between joint venture and parents. Realizing complementarity knowledge benefits cause higher degree of a joint venture’s knowledge exploitative acquisition. Technology similarity in an JV setting brings in complementary knowledge bases that may be combined and integrated to create innovation value for joint venture. Thus, technology similarity is defined as the joint venture technology portfolio in the same patent class with two parents’. They are in the form of similar product development knowledge and skills, which comprise a large potential for learning and innovation creation through the combination of these different technologies and knowledge resources. In other words, technology similarity emphasizes the knowledge synergies that exist between joint venture and parents. Realizing complementarity knowledge benefits cause higher degree of a joint venture’s knowledge exploitative acquisition. Technology similarity is considered to be a critical source of inter-firm knowledge synergy in equity relationship. Parent firms possess a sufficient foundation of similar knowledge that includes related skills, technological understanding, and language, to enable effective communication and overcome cognitive barriers for joint venture in exploitative knowledge acquisition (Yao et al. 2013). The resulting synergy is achieved when equity-relationship provides access to parents’ knowledge resources that can be utilized to improve joint venture’s innovation advantage.

Second, we propose that technology similarity significantly help the joint ventures to utilize and build exploitative knowledge acquisition effectiveness. When technology similarity is high, joint venture can trigger new ideas, better exploit and integrate parents’ knowledge so as to create new innovation (Kogut and Zander 1992). In other words, technology similarity can improve the development of knowledge exploitation effectiveness by integrating synergistic knowledge bases. The synergistic nature of parents’ knowledge facilitates the generation of new innovation. One joint venture’s ability to exploit the knowledge of another depends on the familiarity with parents’ technological knowledge (Henderson and Cockburn 1994; Lane and Lubatkin 1998). Technology similarity permits the joint venture to comprehend the assumptions that shape parents’ knowledge and thereby be a better understanding to exploit the important of the new knowledge (Cohen and Levinthal 1990; Lane and Lubatkin 1998).

Finally, relying on technology knowledge that is similar and already resides within the parents is more cost-effective and has a higher probability of innovation success, compared with searching unfamiliar technology domains(Yang and Steensma 2014). Technology similarity also promotes economics of learning for joint ventures to approach to the knowledge exploitation. Such as the experience curve must be taken into account on joint venture’s innovation (Winter 1984). A joint venture may become more efficient in knowledge exploitation as experienced is gained from parents. A joint venture may also be able to draw on that knowledge by seeking the help of parents when they encounter difficulties (Clark et al. 2013). We proposed that technology similarity allow joint ventures to specialize their knowledge base, and then to exchange this specialized knowledge with parents. Thus the more receptive exploitative knowledge acquisition by joint venture are to existing knowledge of parents, the more likely it is to learn and knowledge exploitation, and then induces higher innovation performance of joint venture. The above reasoning leads to following hypothesis: In this manner, learning from parents with technology similarity allows each joint venture to acquire and develop knowledge exploitation effectiveness. In this manner, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 2

JV-Parent technology similarity positively moderates the relationship between exploitative knowledge acquisition and innovation performance of joint venture. In such a way that a high level of JV-Parent technology similarity increases innovation performance of joint venture gains attributable to exploitative knowledge acquisition.

2.5 JV-Parent country similarity, exploitative knowledge acquisition and innovation performance

The country location between sender and recipient also influence the efficacy of knowledge exploitation (Szulanski 1996). A moderating factor determining the relationship between exploitative knowledge acquisition and innovation performance is whether the joint venture and parents are from the same country or different ones. A joint venture will be better able to exploit parents’ knowledge when the organizations have country similarity with its parents. First, when highlighting the role of norms, values and cultural compatibility as a relevant antecedent for making sense of parent’s knowledge, country similarity could induce knowledge exploitative acquisition, which in turn shapes benefits for innovation. More specifically, country similarity identifies the degree to which joint venture and its parents share a set of norms or values that constitute an inter-organizational similar culture, common goals and objectives, business philosophies, or management styles, for achieving strategic exploitation alignment between joint venture and its parents.

Second, when they are from different countries, the managers of the joint ventures perceived that geographic distance, language barriers, communication style differences and different legal and political systems are all to be the barriers to exploitative knowledge acquisition between joint venture and its parents. For example, employees in western firms almost all lacked Japanese language skills and culture experience in Japan limited their access to their Japanese partners’ know how (Hamel 1991). Besides, regional economists suggest that not only do knowledge spillovers generate externalities, but that they also tend to geographically bounded (Henderson 1992; Krugman 1999). In other words, country similarity is important for exploitative knowledge acquisition from its parents.

Finally, the joint venture would discount input knowledge coming from parents if it do not perceive message rightly. Mutual clarity is extremely hard to achieve without an understanding because of country differences. We consider that country similarity helps joint ventures exchange information openly and capitalize on the knowledge exploitation potential. Drawing upon the argument and empirical evidence, the following hypothesis is developed.

Hypothesis 3

JV-Parent country similarity positively moderates the relationship between exploitative knowledge acquisition and innovation performance of joint venture. In such a way that a high level of JV-Parent country similarity increases innovation performance of joint venture gains attributable to exploitative knowledge acquisition.

2.6 JV-Parent industry similarity, exploitative knowledge acquisition and innovation performance

The JV-Parent similarity in industry may also affect exploitative knowledge acquisition. When a joint venture and its parents in the same industry could share a similar competence base (Rumelt et al. 1991), similarity in the product resource endowments of factors such as technologies, engineering and production capabilities provide new skills to learn and may be used for combining assistant knowledge through exploitative knowledge acquisition, and then create the innovation for the joint venture in early stage. In order to purse new innovational opportunities, a joint venture with assistant product endowments potentially has significant opportunities to learn from its parents. If they belong to different industrial area, the joint venture relationship as a means of acquires new knowledge from its parents have deficiencies. There would be a drop between accumulation of knowledge from its parents and a joint venture’s ability to comprehend and exploit it (Lyles and Salk 1996).

Although relying on industry similarity may seem easy and relatively efficient for knowledge exploitative acquisition; however, it may be so effective in practice, especially in case where industry environment have changed to the point where parents existing knowledge is rendered irrelevant for new innovation. The joint venture becomes trapped within parents restricted technology domains and risk simply exploitative knowledge acquisition from its parents.

Furthermore, in a high level of exploitation, JV-Parent industry similarity will be less new product knowledge to absorb and lacks strategic value. There will be result in overlapping and redundant research and fewer knowledge synergies for producing different products (Rindfleisch and Christine 2001), therefore exploitative knowledge acquisition would go down and leads to decreases innovation performance of joint venture. Thus the generation of JV-Parent industry similarity becomes a crucial negative moderator between exploitative knowledge acquisition and innovation performance. The above reasoning leads the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 4

JV-Parent industry similarity negatively moderates the relationship between exploitative knowledge acquisition and innovation performance of joint venture. In such a way that a high level of JV-Parent industry similarity decreases innovation performance of joint venture gains attributable to exploitative knowledge acquisition.

3 Methods

3.1 Research setting and sample

We examine the effect of exploitative knowledge acquisition on innovation under different conditions of joint venture’s similarity with parents in technology, industry and country. Because differences in age may indicate differences in experience with the knowledge exploitation process (Lane et al. 1998), in this study the unit of analysis is the joint venture which had been operating for 6 years after is established. Following earlier research in joint venture, we first relied on the SDC (Securities Data Corporation) database in compiling records of joint ventures and parents between 1985 and 1996. Because the case of two parents differs from cases with three or more parents as the degree of complexity in interactions, the sample accounts for only one joint venture and two formed parents.

The unit of analysis is the newly established joint venture in a given year. We use the two-digit sic code groupings for our industries by 28, 35, 36 and 38, and has proved to be representative of industrial innovation. Therefore, the joint venture formed in these industries is an appropriate setting for testing our research model and hypothesis. A total of joint venture and parents US patents and their patent citations were extracted from the NBER (National Bureau of Economic Research, USA) database during the targeted period, and then used the U.S. patent information of the selected industries from the NBER database because this comprehensive database of U.S. patents is publicly available and has been recognized in the technology management literature (e.g. Hall et al. 2001; Miller et al. 2007).

To compile our sample, this study corrects these patent records by searching assignees in NBER (National Bureau of Economic Research, USA) database. The data that we use are cross-validated by SDC and NBER databases. Following these procedures, joint venture records are deliberated and eliminated, the effective sample size that we identified is 183 joint ventures involving 366 ultimate parents during the 11-year period. Patent granted for joint venture would be some years later, to facilitate causal inference we sum up the measures of the independent, control and dependent variables by 6-years window after established as the unit of analysis in our case, that is, the time period for all the variables is 1985–1996 while for variable value is 1986–2002, thus limiting potential biases that may have arisen from the lack of patent information for joint venture. All the variables in this study are measured by aggregating the parent data for each of the targeted joint ventures. Table 1 shows the location for the joint venture in our research.

3.2 Data construction with details

The NBER patent data set used for the empirical analysis consists of successful patents granted and forward and backward citation published by the US Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO). This data set, constructed by Hall et al. (2001), contains detailed information on almost four million patents granted by the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) between 1963 and 2002. It includes annual information on patent assignee names, the number of patents, the number of citations received by each patent, the technological class of the patent, and the year that the patent application was filed and granted. This data set contains more than 20 million citations made between 1975 and 2002. Information contained in patent data makes it ideal for tracking the impact of knowledge acquisition and inventive activities, indicating the knowledge learning in which these activities took place, and for gauging the extent to which they resulted from knowledge inflow and outflow between JVs from the parents or other firms. Therefore, patent data comprehensively covers the innovative activities of firms and is a better proxy for innovation in this context (Hall et al. 2005).

Our dataset is constructed by merging data on patents obtained directly from the NBER database and joint venture data from SDC database. For the purpose of this research we have brought together two large datasets and linked those via an elaborate process. Data collection took a long time. A major challenge with research that relies on patent data is matching each joint venture and parent companies to all the patents they granted. This is due to the absence of identical key identifiers in the NBER and SDC database. To ascertain whether a specific innovation should be considered as originating from joint ventures or from parent companies operating in the equity relationship, we need to know what its assignee name’s relationship is. For instance, International Business Machines could also be International Business Machines Corp. or IBM, or even the name of one of its foreign subsidiaries. As with other studies, several steps are taken to clean the data, thereby obtaining a more accurate account of all the patents that are assigned to each joint venture and parent companies. We use The Directory of Multinationals to verify the list of multinational firms that have substantial capital investments in foreign countries. The Directory of Multinationals describes the relationship between companies worldwide, showing parent companies and their subsidiaries, and provides the company’s name and address of the parent firm, and the names and addresses of its foreign subsidiaries and affiliates. Thus, the matching of the two datasets by joint venture and related parents’ name proved to be a formidable, large-scale task that tied up a great deal of our research.

Data that is made available from the NBER patent data set is used to match SDC database with name consistency. Each variation in the names of the 183 joint ventures of the 366 parent companies retrieved from the SDC database is compared against the names of more 200,000 assignees that were granted a USPTO patent between 1985 and 2002. A patent from a German subsidiary of IBM could appear as being owned by the parent company, IBM, or a separate assignee name such as IBM Japan, or something else whose affiliation to IBM is not apparent. To construct our JV–Parents database, we had to design programs to match and manually verify the consistence of the two-sided assignee names.

Finally, the database by the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) for patent information of U.S. industries, which this study uses as its empirical setting, provides an excellent context for testing hypotheses. The United States is the largest single market in the world, so foreign and native firms often protect their intellectual property rights with US patents (Penner-Hahn and Shaver 2005). In addition, the United States is significant in the development of innovation. For more than 200 years, “the USPTO has been at the cutting edge of the nation’s technological progress and achievement. The strength and vitality of the U.S. economy depends directly on effective mechanisms that protect new ideas and investments in innovation, and disclose new technology worldwide. So the USPTO promotes and facilitates technological progress in the United States and the development and sharing of new technologies worldwide” (USPTO 2008). Therefore, USPTO patent information is appropriate for the innovation, and fits objectives for this research.

3.3 Measures

3.3.1 Dependent variable

3.3.1.1 Innovation performance

The performance outcomes impute to learning (whether or not that learning has been directly measured or traced) vary greatly in the literature (Salk and Simonin 2003). Prior research in the innovation management literature has widely used patent statistics to evaluate innovation performance (Griliches 1984, 1990). A number of prior studies use the raw count of the number of granted patents to measure innovative output (e.g., Griliches et al. 1988; Breitzman and Mogee 2002; Penner-Hahn and Shaver 2005) and as a way of how much is learned (Lane and Lubatkin 1998). Most of the time, the financial performance has not been collected before joint venture goes public (Ohmae 1989). Accordingly, the innovation performance is operationalized as the sum up number of patents granted to a joint venture i by 6 years after established in year t. We obtain the data for the computation of innovation performance from the NBER database.

3.3.2 Independent variables

3.3.2.1 Exploitative knowledge acquisition

There is a broad consensus that exploration and exploitation are important for organizational learning and adaptation (Koza and Lewin 1998; Sidhu et al. 2007). Exploitation has been characterized as fundamentally different search modes from exploration. Innovation is anchored in both exploitative knowledge acquisition from related parents and from others innovations to generate new possibilities through exploration. In this study, The exploitative knowledge acquisition is defined as the ratio of the sum of patent that have cited from parents to the number of total citing patents in later 6 year after joint venture is established.

3.3.2.2 JV-Parents technology similarity

Technology similarity refers to the patent portfolio of joint venture technological development in the same patent class with two parents’. We measure the joint venture technology similarity construct as the ratio of the sum number of patents in the same patent class held by parents to the total number developed by joint venture in later 6 years after established.

3.3.2.3 JV-Parents country and industry similarity

JV-Parents similarity may influence the innovation of joint venture because of at least two interpretations for this result. One interpretation is that there are higher levels of knowledge flows or knowledge stock in the same industry or country. So this variable is an index measuring differences among the nation and industry for joint venture and its parents. The information has been provided that joint venture and its parents come from by SDC database. The JV-Parents similarity measures is defined as 0 as country dummy if joint venture is located in different country with two parents, 1 otherwise. Industrial dummy uses the same measurable way as country.

3.3.3 Control variables

To empirically test the effects of exploitative knowledge acquisition and JV-parents similarity on innovation performance, we control the difference of ownership, industry-year factor and Host country GDP (Gross domestic product), difference of ownership, industrial effects, year effects and Host country GDP effects, which might influence the dependent variable.

Since we have panel data of our set of joint ventures over time, there may be certain unaccounted joint venture effects that are fixed over time or vary randomly with time that influence innovation. To control for these effects we take use of joint venture’s fixed effects and random effects in our panel data. The advantage of apply these methods is they control for many joint venture’s characteristics such as business’s culture of innovation, structure and the speed of technology adaptation, that may influence innovation performance. To overcome the characteristics which might or might not be observable and measurable to the researchers (Almeida and Phene 2004; Penner-Hahn and Shaver 2005).

It has long been argued that a parent’s level of equity ownership in a joint venture is reflective of its commitment to the investment (Anderson and Gatignon 1986; Lu and Beamish 2006). To some extent, equity is like hostages which can help mitigate opportunism in joint venture relationship (Dhanaraj and Beamish 2004; Lu and Beamish 2006). From the broader perspective of difference of ownership, bargaining power is reflected in ownership shares, and thus could induce change in joint venture learning priorities, location, board of directors and reporting relationships (Makhija and Ganesh 1997). There is a need to control the effect on difference of ownership and consequently on innovation performance.

Following Minbaeva et al. (2003), we control for industry characteristics since some industries in our research could be more innovative among all analytical industries. The use of industry dummies is for fixed industry effect to capture various patent application and citation behavior in different industrial technological progress. Besides, the innovation performance may increase or decrease over time. Accordingly, we included fixed year effects that control for differences in year when patents granted in the beginning of this research by using dummy variables for year n − 1 in the testing period (Nerkar and Paruchri 2005; Wadhwa and Kotha 2006). Finally, we included 6-year host country GDP where joint venture located as a control variable, and the data is taken from International Monetary Fund (IMF). Joint venture role may be driven by the local environmental context. We therefore include a control variable related to the host country to mirror the demands for technological sophistication and innovation that could influence joint venture’s innovation (Almeida and Phene 2004). All of the measure descriptions of the variables are presented in Table 2.

3.4 Model and estimation

Since the dependent variable, innovation performance, is a count variable and takes on non-negative integer values, a nonlinear regression approach to avoid heteroskedastic, nonnormal residuals is more appropriate to be used. Studies involving patents and their citations poses a number of econometric and measurement issues, which stem from the count nature of the dependent variable (Allison 2001; Hausman et al. 1984; Almeida and Phene 2004). In this research we use negative binomial regression, to test the hypotheses because the variance of the dependent variable is larger than its mean, indicating overdispersion in the data. When there is overdispersion, the Poisson estimates are inefficient with standard errors biased downward yielding spuriously large z-values, causing underestimation of stand errors and inflation of significance levels. Negative binomial regression is appropriate to use when the overdispersion in an otherwise Poisson model is thought to be take the form of a gamma distribution. It deals with cases in which there is more variation than would be expected of the process is Poisson.

The Negative binomial regression is a generalization of the Poisson model by including an individual unobserved disturbance term (Allison 2001). The model takes the form: ln λi = βXi + εi, where λi equals to the mean and variance of yi, Xi is the vector of regressors, and exp(εi) has a standard gamma distribution (Agresti 1990). In addition, since we have no prior information about the unobserved heterogeneity, we first conducted a Hausman (1978) test to check whether fixed or random effects models are more appropriate. The results are inconclusive as the Hausman test did not converge for our data. Accordingly, we use both fixed and random effects estimators in the following analyses.

Finally, according the result of negative binomial regression, in this study we construct three-dimensional simulated diagrams to illustrate the curvilinear relationship between exploitative knowledge acquisition with its parents and innovation performance, and show how such curvilinear relationship moderated under the JV-Parents similarity in technology, country and industry.

4 Results

This study attempts to understand the role of exploitative knowledge acquisition and similarity with its parents in determining innovation performance by using a firm-year unit of analysis. Table 3 presents correlations and descriptive statistics for all measured variables in this study. The values of variance inflation factors (VIFs) associated with each of the predictors are within a range from 1.010 to 1.052 with a mean of 1.022. The effects of multicollinearity are within acceptable limits, and do not suggest any potential for concern with respect to serious multicollinearity in the negative binomial regression (Hair et al. 1998).

We report the results of the fixed-effects and random-effects of the negative binomial regression analysis in Tables 4 and 5 when the data on all research samples are considered. Models 1 are the models that include only the exploitative knowledge acquisition as linear term and Models 2 introduce the linear term and quadratic terms of the exploitative knowledge acquisition to test Hypothesis 1. Model 4 and Model 10 incorporates the interaction effects between Joint venture technology similarity and exploitative knowledge acquisition to test Hypothesis 2. Finally Model 6 and Model 12 represent to incorporate the moderating effects between exploitative knowledge acquisition and the two factors of JV-parent similarity, country similarity and industry similarity, to test Hypothesis 3 and 4. Respectively, although the values of industry and year effect not reported, all models include industry and year dummies to control for unobserved heterogeneity and time-varying factors. As shown in F values and Wald \( \chi^{2} \) statistics in Tables 4 and 5, these twelve models are all significant.

4.1 Direct effect

Hypothesis 1 posits an inverted U-shaped relationship between exploitative knowledge acquisition and innovation performance. The results in Models 1–2 and Model 7–8 indicate that the coefficients for exploitative knowledge acquisition are positive and significant (p < 0.001) while its squared terms are negative and significant (p < 0.001). The coefficients for exploitative knowledge acquisition and exploitative knowledge acquisition squared are significant in both fixed-effect and random-effect negative binomial regressions. Hypothesis 1 is strongly supported, indicating that the relationship between exploitative knowledge acquisition and innovation performance is nonlinear. These findings indicate that exploitative knowledge acquisition exhibits a curvilinear relationship with innovation performance. A middle level of exploitative knowledge acquisition results in a better innovation performance than a lower or a higher level of exploitative knowledge acquisition does.

4.2 Moderator effects

Hypothesis 2 posits that the factor of JV-parents technology similarity positively moderates the relationship between exploitative knowledge acquisition and innovation performance. We test the hypothesis by adding the interaction term of exploitative knowledge acquisition and JV-parents technology similarity in Models 4 and Model 10. The interaction terms are positive and statistically significant (p < 0.001), and a log-likelihood test shows that inclusion of the interaction further improves model explanation. Hence, Hypothesis 2 is also supported. In addition, hypothesis 3 and 4 examine the moderating role of JV-parents country and industry similarity on the exploitative knowledge acquisition-innovation performance relationship. The interaction terms, exploitative knowledge acquisition by JV-parents country similarity and industrial similarity, are one positively and the other negatively signed in Models 6 and Model 12, both of them are statistically significant (p < 0.05). These findings modestly confirm the prediction of Hypothesis 3 and indicate that country similarity positively moderate the relationship between exploitative knowledge acquisition and innovation performance, on the contrary, the results for industry similarity negatively moderate the relationship between exploitative knowledge acquisition and innovation performance.

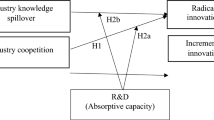

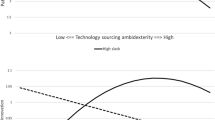

To gain further insights into the nature of the moderating effects between knowledge exploitation and innovation performance, we utilize a separate regression based on the results obtained in Model 4 to plot the inverse U-shaped curve. In Fig. 1, we constructed a three-dimension diagram to illustrate the curvilinear relationship between exploitative knowledge acquisition and innovation performance under different levels of joint venture technology similarity. Innovation performance is first increases, as the degree of exploitative knowledge acquisition continuously increases. A higher level of exploitative knowledge acquisition would result more innovation outcome under a given level of JV-parents technology similarity. As exploitative knowledge acquisition increases, the optimal level of exploitative knowledge acquisition moves toward the right side. These results further confirm that JV-parents technology similarity positively moderates the relationship between exploitative knowledge acquisition and innovation performance.

Similarly, Figs. 2 and 3 are two three-dimension diagrams, based on the results of Model6, to illustrate the curvilinear relationship between exploitative knowledge acquisition and innovation outcome under different levels of JV-Parent similarity in country and industry. Figure 2 is similar with Fig. 1. The level of innovation performance is promoted as JV-Parent country similarity increase. A higher level of country similarity would result more innovation outcome under a given level of country similarity. As country similarity increases, the optimal level of exploitative knowledge acquisition moves toward the right side. These results further confirm that country similarity positively moderates the relationship between exploitative knowledge acquisition and innovation performance.

Figure 3 also depict a curvilinear relationship that innovation performance increases initially and then decreases as exploitative knowledge acquisition increases. However, the increase of industry similarity worse the loss and delay the progress to get the positive gain, the optimal level of exploitative knowledge acquisition moves toward the left side. In addition, as exploitative knowledge acquisition encourage more knowledge acquisition from its parents, the arc of exploitative knowledge acquisition becomes flatter before the peak and becomes steeper after the peak. These results further confirm that industry similarity negatively moderates the relationship between exploitative knowledge acquisition and innovation performance.

5 Conclusion and policy implication

To better understand how joint ventures exploits knowledge from its parents, we use on panel data of four industries from 1985 to 1996 by combining NBER and SDC database. A dataset of 183 joint ventures is collected to test hypotheses. Three main conclusions are summarized here:

First, this study examines the relationships among exploitative knowledge acquisition, JV-parents similarity in technology, country and industry, and how they affect innovation performance. Literature on knowledge learning recognized the positive effect on innovation performance (e.g. He and Wong 2004; Atuahene-Gima 2005; Auh and Menguc 2005; Mc Namara and Baden-Fuller 2007; Flint et al. 2008; Paulraj et al. 2008; Groysberg and Lee 2009; Yang and Steensma 2014; Park et al. 2015). In this study, we echo the suggestion there is a significant conversion loss exists between exploitative knowledge acquisition and innovation performance, and propose that there are inverted U-shaped relationship which suggests the existence for an optimal level of exploitative knowledge acquisition for joint venture’s innovation performance. One of our major contribution of this study relates to the introduction of negative forces that opens up an interesting avenue of theory and research that are yet explored. Thus, in the short term, a joint venture may accelerate its innovation performance through exploitative knowledge acquisition from its parents which they already possess experience, technology and knowledge. Conversely, in the long term, the greater the learning from parents in which the joint venture operates, it tends to slow the innovation performance down. An optimal level of exploitation would exist to achieve better innovation performance due to the conciliation between the positive and negative forces governing the relationship.

Before the optimal level, the increase of exploitation from parent’s knowledge would enhance joint venture’s innovation performance. Higher level of exploitation may benefit sufficiently from wide-range advantages. Exploitative knowledge acquisition from its parents is relatively easy to transfer and to be absorbed. Joint ventures gaining from refinement of existing parents’ knowledge and learning from experience reduce transaction costs and thereby expedite to transfer and to be absorbed (Child and Faulkner 1998). Because of equity association between joint venture and its parents, the establishment of the joint venture relationship is likely to result in ease of coordination. Joint venture relationship facilitates close and repeated interaction and then breeds mutual commitment, and help joint venture acquire and assimilate knowledge from the parents due to the reliability and faithfulness. Opportunistic behaviors would reduce and knowledge acquisition and sharing process can become more effectively. The strategic control of technological development avoids unnecessary duplication of efforts and efficiently exploits available capabilities, and combines existing technological knowledge. The communication for the knowledge exchange and acquisition is made easier by the joint venture and the parents through the exchange of information through various media, and then develop the deeper understanding necessary to develop new innovation (Katila and Ahuja 2002). Path dependence in exploitative learning facilitates routine-based experiential learning. It increases its efficiency and likelihood of desirable outcome, and avoid putting his survival at risk in early stage (Lavie and Rosenkopf 2006).

Previous studies have not actively highlighted that exploitative knowledge acquisition come with inherent downsides, such as limited opportunity cost perspective, organizational core rigidities, and loss of exploration. Innovation performance would be down as exploitation increases after optimal level. Higher level of exploitation is more likely to miss opportunities to explore competitors and other new innovation advantages (Child and Markoczy 1993). When a group of knowledge is repeatedly used, the potential for future combinations among these knowledge sets become exhausted and diminished ability of joint ventures to conceive of new innovation (Fleming 2001; Kim and Kogut 1996). The primary sources of core rigidities lie in the difficult-to-change nature of the JV-Parent innovation system suggest that obstacles to innovation are embedded barriers to changes (Makino and Inkpen 2003). External relationships such as suppliers, customers, and research institution are an important source of learning. They link with the technological community to maintain an open-ended social interaction and learning process, thus contribute to speed up innovation and also broaden the boundary of knowledge base for joint venture.

Second, we argues that interesting evidence for a moderating relationship with the contingent role of JV-parents technological similarity, country similarity and industrial similarity in affecting the relationship between exploitative knowledge acquisition and joint venture’s innovation performance. JV-Parent technology similarity and country similarity positively moderates the relationship between knowledge exploitation and innovation performance of joint venture. In such a way, high level of JV-Parent technology and country similarity increases innovation performance of joint venture gains attributable to exploitative knowledge acquisition. Besides, industrial similarity would achieve a better improvement effect on innovation performance when they are in a lower degree of exploitative knowledge acquisition.

Third, when moving knowledge learning from a general context to the more specific equity-relationship, we narrow down the major sources of external knowledge. The alliance literature highlights that superior value creation extends beyond the boundaries of one organization and involves integrating business processes among strategic partner (Paulraj et al. 2008). Value creation is not limited to traditional operational improvements but also includes strategic benefits such as innovation through the development of new idea and knowledge (Im and Rai 2008). In a joint venture setting, external knowledge is gleaned from parents through the building of deep equity relationships. This relationship facilitates social interaction, exchange of knowledge, and joint development of new ideas. Moreover, they aid productive learning, because the relationship broadens the array of possible experiences of the company’s involved. Thus, a research gap exists in understanding how joint ventures create knowledge exploitation relationships with its parents to achieve strategic and innovation benefits.

Finally, this paper advances understanding of the role of exploitative knowledge acquisition as individual joint venture capability in equity-relationship with external knowledge coming from its parents, focusing on specific learning processes that dynamically change and upgrade the knowledge resource base. The implications of exploitative knowledge acquisition on performance are explored in terms of innovation efficiency. While most of the studies on alliance relationship have focused on the partners about their parents’ company, the joint venture’s perspective is equally relevant strategic importance because parents are usually engaged in alliance relationship dynamics, with different partner expectations in different settings. Consequently, this research provides empirical evidence of the role of exploitative knowledge acquisition in equity-relationship from the joint venture’s perspective.

In addition to the theoretical contributions above, our study also contributes to practice by providing new insights for managers. The present evidences imply that managers should realize that to be too centered on or too removed from parent’s knowledge exploitation can neither achieve higher innovation performance. Instead, in the course of exploitation evolution after a few years, the optimal level exploitation for innovation needs exploration to play the engine role and drive the innovation progress. Managers need to understand and govern the inevitable trade-off between the positive and negative forces of learning from parents. The positive powers for exploitative knowledge acquisition are learning-curve effect, ease of coordination, smooth communication, relational capital and path dependence perspective. However, such efforts will subsequently face direct conflict with exploitative knowledge acquisition from its parents. Such as opportunity cost perspective, source of core rigidities and loss of exploration. This calls for a cautious cost–benefit analysis for the managers when seeking knowledge from parents’ knowledge base with a special attention to their learning status, specifically when joint venture is well established and managed after a few years. In addition, managers need to recognize the interaction effect of similarity between joint venture and its parents with exploitative knowledge acquisition on innovation performance. Managers are advised to match technology and country similarity for joint ventures to do exploitative activities and thus can stimulate knowledge learning from its parents. On the other hand, managers need to be careful in matching industry similarity in the higher level as industry similarity would cause less new knowledge to absorb, lacks strategic value, overlap and redundant research and thus result in less effective innovation activities. In summary, while the previous literature mainly focuses on how to develop and expand the knowledge base for inter-organizational relationship, our study suggests that considering their strategic equity collaboration positions, managers need to find optimal solutions to the trade-off between the positive forces to acquire parents’ knowledge and the protection method of negative forces that causing damage to innovation for joint venture’s exploitative knowledge acquisition perspective. Such generations about the knowledge learning evolution could be considered the results of opening the black box of the speed of joint venture’s innovation. These possible downsides of joint venture’s innovation may imply that academic researchers needed further investigation on the topic of parents’ knowledge acquisition at the firm level.

6 Future avenues of research

This research explores the usefulness of patent and patent citations as a measure of the important of a joint venture’s exploitative knowledge acquisition and innovation performance (Jaffe et al. 1993, 2000; Hu and Jaffe 2003). There is a considerable literature that Patents have long been recognized as a very rich and potentially fruitful source of data for the study of innovation and knowledge exploitation. Indeed, there are numerous advantages to the use of patent data (Hall et al. 2005). For example, if the firm decides to apply for a patent, it recognizes the potential value of the invention, of course, this does not mean that the non-patented knowledge is worthless, but we should advocate that the patented knowledge is the one most likely to be commercialized (Lukach and Plasmans 2005). If a patent is granted, an extensive public document is created. The front page of a patent contains detailed information about the invention, all of which can be accessed in computerized form (Trajtenberg et al. 1997). Each patent contains highly detailed information on the innovation, patent display extremely wide coverage in terms of technologies, the assignee and geography; there are already millions of them, the amount of over 150,000 USPTO (U.S. patent and Trademark Office) patent grants per year; and the data contained in patents are supplied entirely on a voluntary basis (Hall et al. 2005). Knowledge exploitation sometimes leave a paper trail by the form of citations in patents. Because patents contain detailed geographic information about their inventors, examining these trail actually allow us to use citation patterns to test the exploitative knowledge acquisition.

There are also a number of potential limitations to the use of patent data. First, the most glaring being the fact that not all patented inventions result in innovations and all technological innovations may not be patented, simply because not all inventions meet the patentability criteria and because the inventor has to make a strategic choice to patent, as opposed to rely on secrecy or other means of appropriability (Penner-Hahn and Shaver 2005; Hall et al. 2005). Second, not all measuring of exploitative knowledge acquisition of organization knowledge are captured by patent citations; at best, citations capture only codifiable knowledge and cannot capture transfers of tacit knowledge such as organizational routines. Patent citation is only a rough measure of knowledge exploitation (Hu and Jaffe 2003; Almeida and Phene 2004). Third, an important limitation of our research is that it has information only on patents granted by the U.S. Patent office, and on citations to patents granted by the U.S. Patent office. If there are systematic country-specific differences in the patenting or citation practice among different countries, this study limits the rate of citations bias which may be citied by non-U.S. firms and could be a potential source of bias (Hu and Jaffe 2003). Any above bias is likely to have an impact on the results of this research.

References

Abdelal, R. (2007). Capital rules: The construction of global finance. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University.

Agresti, A. (1990). Categorical data analysis. New York: Wiley.

Ahuja, G., & Lampert, C. M. (2001). Entrepreneurship in the large corporation: A longitudinal study of how established firms create breakthrough inventions. Strategic Management Journal,22, 521–543.

Alderson, A. S., & François, N. (2002). Globalization and the great U-Turn: Income inequality trends in 16 OECD countries. American Journal of Sociology,107, 1244–1299.

Allison, P. D. (2001). Logistic regression using the SAS system: Theory and application. New York: Wiley.