Abstract

Primary care physicians are uniquely positioned to assist ill and injured workers to stay-at-work or to return-to-work. Purpose The purpose of this scoping review is to identify primary care physicians’ learning needs in returning ill or injured workers to work and to identify gaps to guide future research. Methods We used established methodologies developed by Arksey and O’Malley, Cochrane and adapted by the Systematic Review Program at the Institute for Work & Health. We used Distiller SR©, an online systematic review software to screen for relevance and perform data extraction. We followed the PRISMA for Scoping Reviews checklist for reporting. Results We screened 2106 titles and abstracts, 375 full-text papers for relevance and included 44 studies for qualitative synthesis. The first learning need was related to administrative tasks. These included (1) appropriate record-keeping, (2) time management to review occupational information, (3) communication skills to provide clear, sufficient and relevant factual information, (4) coordination of services between different stakeholders, and (5) collaboration within teams and between different professions. The second learning need was related to attitudes and beliefs and included intrinsic biases, self-confidence, role clarity and culture of blaming the patient. The third learning need was related to specific knowledge and included work capacity assessments and needs for sick leave, environmental exposures, disclosure of information, prognosis of certain conditions and care to certain groups such as adolescents and pregnant workers. The fourth learning need was related to awareness of services and tools. Conclusions There are many opportunities to improve medical education for physicians in training or in continuing medical education to improve care for workers with an illness or injury that affect their work.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Primary care physicians are in a strategic position to assist ill and injured workers to stay-at-work (SAW) or return-to-work (RTW) [1, 2]. Work has many health benefits and is associated with improved mental and physical health. Likewise, being unemployed can have negative impacts on health and wellbeing [3]. Positive and encouraging messages from physicians are associated with better RTW outcomes and patients who receive information about injury prevention, pain management and work accommodation are more likely to RTW [4, 5].

The role of the physician in the RTW process has, over the last decade, been firmly established. In 2013, the Canadian Medical Association released a policy “to diagnose and treat the illness or injury, to advise and support the patient, to provide and communicate appropriate information to the patient and the employer, and to work closely with other involved health care professionals to facilitate the patient’s safe and timely return to the most productive employment possible” [6]. In 2019, the UK Academy of Medical Royal Colleges committed to a consensus statement for action around health and work [7]. It states that all physicians should be able to identify work-related diseases and offer support and advice to enable work participation for patients who wish to work. The American Medical Association encourages all physicians “to advise patients to RTW at the earliest date compatible with health and safety and recognizes that physicians can, through their care, facilitate patient’s return to work” [8]. In Australia, a return-to-work flowchart was developed in 2016 at WorkSafe Victoria and the Transport Accident Commission, Victoria, to provide a systematic method for primary care physicians [9].

However, it has been noted that many physicians feel uncomfortable addressing medical questions in the assessment of disability for their patients [10]. Medical training in North America is inconsistent in providing structured training for residents and fellows on the medical aspects of disability, and some physicians do not feel competent to assess patients’ functional abilities [10]. Furthermore, primary care physicians have limited time to spend with patients, which impedes the assessment of patients’ capabilities and limitations [11].

Work-related injuries and illnesses represent a large burden to society. In 2015 there were over 230,000 claims filed at workers’ compensation systems in Canada [12]. Data from the International Labour Organization suggest that 2 million people die worldwide from work-related diseases (not accidents) every year and that these diseases cost at least 145 billion euros annually [13]. Many diseases have an occupational cause and they are mostly unrecognized due to lack of proper diagnosis by healthcare providers. There are estimates that 15% of all adult asthma, 15% of all chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, 10% of all lung cancers, 37% of all low back pain and 15% of all hearing loss cases are due to occupational causes [14,15,16,17,18].

There is evidence that providing structured education to primary care physicians changes their perceptions and intentions related to work-related injuries, but weak evidence of behaviour change [19]. However, there is not much known about primary care physicians’ needs in returning ill or injured workers to work; therefore, there is a need to identify topics and methods to teach physicians how to assist their patients to SAW or RTW.

The goals of this scoping review were to identify primary care physicians’ learning needs in returning ill or injured workers to work, and to identify gaps, inconsistencies, and key areas to guide future research. This review is a component of a larger project to develop and test an educational intervention about occupational and environmental medicine for primary care physicians in Ontario, Canada.

Methods

We used established methodologies for conducting scoping reviews developed by Arksey and O’Malley [20], Cochrane [21], and adapted by the Systematic Review Program at the Institute for Work & Health (IWH) [22]. We used Distiller SR©, an online systematic review software to screen for relevance and perform data extraction and followed the PRISMA for Scoping Reviews checklist for reporting [23].

The search strategies were designed according to the P.I.C.O. inclusion criteria (See Online Appendix 1).

The search strategy was drafted in MEDLINE (Ovid) by the IWH librarian with input from the research team. Searches were adapted according to the database being searched and its controlled vocabulary; there were no language restrictions (Online Appendix 1). As a preliminary check of the search strategy’s accuracy, the team put together a list of 37 potentially relevant articles obtained from draft searches, of which 33 “must have” articles were captured by the search strategy. Peer-reviewed articles from the following electronic databases were searched from 2016–2021: Ovid MEDLINE: Epub Ahead of Print, In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations, Ovid MEDLINE® Daily and Ovid MEDLINE® < 1946-Present > , Embase Classic + Embase < 1947 to 2021 February 15 > , ERIC, Cochrane Library, and CINAHL. The search was run on February 16th, 2021 and was limited to the last 5 years due to constraints in time and resources for this project.

To supplement the searches, reference lists of articles meeting our inclusion criteria were manually scanned for references not previously captured.

We developed title and abstract (TA) and full-text (FT) screening tools to facilitate the process of including relevant articles. The screening tools and operational definitions are located in Appendix 2. Both tools were pilot tested by the team before use. Rotating pairs of reviewers screened references for relevance at both stages and disagreements were discussed until consensus was achieved. If agreement could not be reached, a third reviewer was consulted.

We pilot tested the data extraction (DE) tool on 5 studies, double reviewed 10% of the included studies and single reviewed the rest; a third reviewer reviewed all extracted data. Data was extracted on the following: author, year, country, study design, and study population. An additional item was related to the author’s interpretation, conclusions, or findings from the study.

Evidence synthesis was according to the learning needs. Two authors mapped the learning needs and assigned tags to them. The framework for learning needs is shown in Table 1.

Results

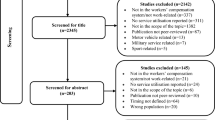

The search retrieved 3309 records. After duplicates were removed, we screened 2106 titles and abstracts; 1731 were excluded as they did not fit our inclusion criteria (primary care physicians) and 375 full-text papers were screened for relevance. We extracted data from 44 studies and synthesized the evidence. Figure 1 shows the PRIMSA flow chart.

Study Characteristics

The 44 included studies were all published in English and conducted in the US, Canada, UK, Ireland, Norway, Finland, Sweden, Denmark, Netherlands, Belgium, Germany, Australia; one study was conducted in 12 European countries. Although we initially aimed to include studies from Canada and similar jurisdictions, we also included a study conducted in Israel due to its relevance to the research question. We included a study from grey literature that was found through screening reference lists of included studies [24]; this study was included as it was clearly relevant to the learning needs of Ontario physicians related to RTW. The target population were general practitioners, residents, fellows, practicing primary care physicians and family doctors. There were 21 qualitative, 20 quantitative and 3 mixed method studies. Four studies were randomized trials. See Table 2 for characteristics of included studies.

Findings

The findings are summarized in Table 1. We categorized the learning needs into four groups: administrative tasks, attitudes and behaviours, specific knowledge, and awareness of services and tools.

Learning Needs Related to Administrative Tasks

Administrative tasks relate to how physicians manage their practices and handle the paperwork associated with their patients’ workplaces, insurances and medical evaluations. It also includes how physicians communicate and collaborate with involved parties and stakeholders to promote a successful RTW. These learning needs include record keeping, time management, communication, coordination and collaboration.

Record Keeping

Physicians need to learn how to record patients’ risk of work disability and when a visit to primary care is work-related or not in their patients’ charts. A randomized controlled trial in Finland aimed at evaluating an intervention designed to improve recording and follow-up of occupational health and safety primary care visits and its impact on sickness absences found that although the intervention did not show any effect on sickness absences, it produced a promising indication of the effectiveness of education on improving occupational health professionals’ practices of recording work-related visits in primary care. This effect was supported by a change in electronic information systems [25].

Time Management

Primary care clinicians need to schedule time to review occupational information during clinical encounters, book longer appointments, and receive more training in occupational medicine. Simmons et.al. conducted a study with physicians, physician assistants, nurse practitioners, nurse midwives, community health workers and other personnel from community health centres in the US. Clinicians cited workers’ compensation as a source of confusion and frustration. However, most participants recognized occupation as an important social determinant of health and expressed interest in additional training and resources [26].

Communication

Three studies reflected the importance of communication. Aarseth et.al. described the importance of general practitioners’ need to provide clear, sufficient, and relevant factual information and coherent medical evaluations to justify the patient’s claims of disability pension [27] while Gray et.al. found that the interactions between GPs and compensation systems need to be improved to better manage differing opinions and streamline the certification processes to overcome issues such as patient advocacy, conflicting opinions and certification of RTW capacity [28]. Kosny et.al. found a need for better alignment between the views of healthcare providers and case managers concerning the timing and appropriateness of RTW [24].

Coordination

Two studies found the need for coordination of services. Specifically, general practitioners, caregivers, employer representatives, occupational therapists and clinical commissioners need to improve coordination between the different stakeholders in the RTW process [29]. In addition, there is a need for coordination between primary and secondary care, especially around transitions home from hospital after injury. Whereas Christie et.al. identified gaps in coordination and information regarding pain control, RTW, psychological problems, services, and a lack of information about the recovery process and persistence of severe symptoms [30].

Collaboration

One study found a need to improve collaboration among mental health professionals, employers and insurers. It found that Information was never exchanged directly with employers, mostly to preserve the confidentiality of information, and was not seen as relevant. Exchange of information with the insurer was considered important, but solely to facilitate access to specialized services such as rehabilitation that would be otherwise difficult to access [31].

There is a need to improve information transfer, particularly electronic transfer, to improve collaboration between physicians involved in the RTW process. Collaboration between general practitioners, occupational physicians and social insurance physicians participating in the study appeared to be problematic, but the participants correctly identified the need for common training [32].

Additionally, there is a need to establish models of teamwork among occupational physicians, oncologists, oncology nurses, social workers, psychologists, and family physicians treating oncology patients. A study showed that teamwork among healthcare professionals to address RTW might contribute to the success of RTW and convey the message that RTW is part of the role of all healthcare professionals [33].

Learning Needs Related to Attitudes and Beliefs

These learning needs refer to physicians’ attitudes and beliefs that could be improved by providing them with education and training. They involve intrinsic biases related to patients’ socioeconomic status (SES), ethnicity, gender, and educational level. Another area was their lack of self-confidence and role-clarity. We also identified a need to learn how to avoid a culture of blaming the patient for not working and not being motivated to RTW.

Intrinsic Biases

Physicians need to be aware that there are significant race-by-SES interactions in their recommendations for chronic pain management. Secondary analysis of data from a large randomized controlled trial in the US showed that physicians in residency and fellowship training, who were practicing in outpatient settings, had significant race-by-SES interactions in their recommendations. For high SES patients, Black (vs. White) patients were rated has having more pain interference; the opposite race difference emerged for low SES patients. For high SES patients, Black (vs. White) patients were rated as being in greater distress; no race difference emerged for low SES patients. For low SES patients, White (vs. Black) patients were more likely to be recommended workplace accommodations while no race difference emerged for high SES patients. Additionally, providers were more likely to recommend opioids to Black (vs. White) and low (vs. high) SES patients and were more likely to use opioid contracts (a document signed by both patient and prescriber about rules for opioid prescriptions and use) with low (vs. high) SES patients. Providers’ implicit and explicit attitudes predicted some, but not all, of their pain-related ratings [34].

Physicians need to be aware that there are significant associations between fit note receipt and ethnicity. A longitudinal study with primary care physicians in the UK showed that all minority ethnic groups, except the Asian group, experienced increased fit note receipt [35].

Physicians also need to be aware that there is an association between gender and education and receipt of medication and counselling. A cohort study in Norway looked at the distribution of sickness absence certification from general practitioners across intersectional groups and found that highly educated women made up the largest group and their male counterparts the smallest. Among long-term absentees, highly educated women were less likely to receive medication compared to all other intersectional groups, and more likely to receive counselling, compared to women with low and medium education [36].

Self-Confidence in Treating Compensable Injury Patients

Brijnath et.al. showed that physicians in Australia refuse to treat patients with compensable injuries because they present with administrative and clinical complexities. The GPs in the study noted that their GP colleagues and medical specialists refused to treat compensable injury patients. A few GPs reported that they also refused treatment to patients with a compensable injury who presented to their clinic for the first time. However, as the inclusion criteria required GPs to have treated or be treating patients with compensable injuries at the time of the study, most GPs commented on their reluctance, rather than refusal, to treat patients with a compensable injury due to administrative and clinical reasons. In the case of compensable injury management, reluctance and refusal to treat is likely to have a domino effect by increasing the time and financial burden of clinically complex patients on the remaining clinicians. This may present a significant challenge to an effective, sustainable compensation system. Urgent research is needed to understand the extent and implications of reluctance and refusal to treat and to identify strategies to engage clinicians in treating people with compensable injuries [37].

However, GPs with more than 10 years of experience had higher confidence in assessing work capacity for disability benefit claims, better patient relations, and a more lenient practice. In addition, the GPs’ self-reported knowledge of workplace adaptations, as well as the importance they assign the task of sick-listing, were significantly associated with their experience of assessing work capacity among potential disability claimants [38].

General practitioners reported a need to deepen their knowledge of the sickness absence certification process. In a study by Hinkka et al., physicians reported they would prefer that these tasks were referred to the occupational healthcare professional and that they would support a national guideline concerning the duration of sickness absence [39].

Role Clarity

There is a need to clarify the physician’s role in providing medical information to workers compensation systems and encouraging RTW. Kosny et al. found that healthcare providers find administrative hurdles, disagreements about medical decisions and lack of role clarity impeded their meaningful engagement in RTW, which resulted in challenges for injured workers, as well as inefficiencies in the workers’ compensation system [11].

There seems to be agreement that the primary role of healthcare providers is to provide diagnosis and treatment of injured workers. However, aside from this established medical responsibility, there was less agreement regarding the healthcare provider’s involvement as it pertained to a number of other RTW issues, including acceptable evidence for claim adjudication, workplace readiness, and early RTW. The question of what role healthcare providers should play in the workers compensation process is without an easy answer. A dialogue between workers compensation boards’ decision-makers and healthcare providers is needed to bring clarity and consensus to their roles, and to ensure that a diversity of stakeholders can achieve a single goal: responsibly returning workers to safe employment [40].

Physicians are reticent to treat injured workers because of bureaucratic requirements associated with workers compensation procedures and because their role is exposed to scrutiny by various institutional actors. There is tension between the gatekeeping role and patient advocacy, resisting or rejecting such roles as incompatible with the doctor’s professional and moral responsibilities. Physicians dealing with workers compensation might benefit from greater understanding of the effect of their own practices on the compensation process, the experiences of their colleagues and, ultimately, on the health of workers [41].

There is a need to understand the role of general practitioners (GP) and occupational physicians (OP) in the RTW process. A study conducted with occupational physicians and general practitioners showed their respective responsibilities as clearly separated from each other but are interested in intensifying their cooperation. Both physicians’ groups rated many variables of potential interfaces to be important. Overall, no competition or rivalry seems to exist between OPs and GPs in Germany according to the present results. But in terms of remuneration in the field of primary prevention services there may be competition: GPs do not want to share certain resources with OPs. Some diametrical attitudes between the two physician groups may exist: OPs accused GPs of lacking knowledge of employees’ working conditions when issuing sick-leave certificates. According to OPs, work-related medical certificates issued by GPs often cause more harm than benefit. In addition, GPs seem to have misgivings about OPs, especially in terms of nonadherence to medical confidentiality towards employers in general and in cases of addictive disorders in employees. In contrast, OPs think they adhere to medical confidentiality [42].

Another similar study found that there is room for improvement with regard to (1) regulation (e.g. formalized role and obligatory input of occupational physicians), (2) finance (e.g. financial incentives for physicians based on the quality of the application), (3) technology (e.g. communication by email), (4) organizational procedures (e.g. provision of workplace descriptions to rehabilitation physicians on a routine basis), (5) education and information (e.g. joint educational programs, measures to improve the image of OPs), and (6) promotion of cooperation (e.g. between OPs and GPs in regards to the application process) [43].

In the UK, vocational services are integrated into primary care. Sanders et al. showed that physicians need to be knowledgeable of the role of a vocational clinical assistant that works alongside the general practitioner in supporting the management of patients’ work difficulties over and above the clinical problem. This study showed a shift from a solely biomedical to a social model of rehabilitation. Also, it was recognized that changing vocational assistant and GP behaviour to facilitate engagement in a new intervention is not only about removing organisational obstacles but also equipping professionals with the skills to negotiate occupational boundaries in complex multidisciplinary contexts [44].

Culture of Blaming the Patient

Lundberg and Melander found a push and pull framework to cover different motivational factors, societal and individual, that might push or pull patients from or toward work. General practitioners said that the difference between working and nonworking patients is their level of individual motivation while the patients’ stories showed that the main difference was the physical (non) ability to push themselves to work. The authors suggest that work-related support can be improved by addressing such differences in clinical practice [45].

Specific Knowledge and Skills

We identified various areas that relate to specific knowledge related to the practices of occupational medicine. These areas were categorized as performing capacity assessments, knowledge about environmental exposures, mental health disorders, prognosis after certain conditions and injuries, and care related to specific populations such as adolescents and pregnant workers.

Skills to Assess Work Capacity and Need for a Sick Note

A recent study demonstrated that interprofessional clinicians from community heath centers lack training regarding work-related injuries and the workers’ compensation processes. Clinicians recognized the adverse effects of work-related illness and injury on work, functional capacity, relationships, mental health, and income, which often results in depression, disability and adverse effects on family members [26].

Another study identified five categories in the assessment of sick-listed patients that physicians need to learn and include in their daily practice: (1) Identifying, understanding, creating, and fitting the pieces together. This means using previously acquired personal experiences and obtaining accurate information directly from the patient; (2) The significance of the disorder while assessing work capacity and sickness absence; (3) Identifying workplace-related pieces of information. This means identifying work setting, work tasks and work demands; identifying potential risk situations at work, and understanding the patient at work; (4) Identifying capacity in everyday life and contextual pieces of information; and (5) Assessing the need for sickness absence. This means issuing sickness absence certification in cases of decreased work capacity and using sickness absence as a means to having enough time for a thorough diagnostic procedure and assessment of work capacity, but also having time to allow recovery and/or the effect of medication [46].

General practitioners lack knowledge to advise patients specifically concerning their work environment and are not happy with their role in deciding about sick leave. This study found three areas where general practitioners agree about their role in the area of work and health: (1) integration of work context in consultation style; (2) counselling about sick leave; and (3) cooperation with occupational physicians [47]. However, this group conducted a cluster randomized controlled trial to assess the effect of training designed to improve the care of patients with work-related problems in general practice and they showed that training GPs did not improve patients’ work-related self-efficacy or GPs’ registration of work-related problems and occupation [48].

There is a need to address the challenges that GPs experience with the current sickness certification system and their attitudes toward the fit note, which has been in use in the UK since 2010. The fit note focuses on supporting GPs and employers in enabling patients’ RTW. Sixty-six percent of GPs report that sickness certification impacted adversely on the therapeutic relationship and 90% report a lack of available rehabilitation services for patients on sick leave. Fifty-three per cent of respondents who indicated a preference for introducing a fit note were significantly more likely to view the current sickness certification system as having an excessive focus on disability and to report that GPs lack training in completing sickness certification [49].

There is a need to develop guidance that will promote consistent, evidence-based advice about taking time off work because there is large variation on how primary care physicians advise their patients about taking time off work, which cannot be explained by differences in patient reported illness duration [50]. There is evidence of benefit for providing education and guidance using a case-specific discussion with a colleague that focused on the management of long-term sickness absence [51].

General practitioners need to be aware of their own limited skills in performing adequate assessments and how that impacts their patients. A cohort study showed that GPs with the highest case load (i.e., 49 and more claims per provider over the eight-year period) were more likely (by 16%) to issue an alternate/modified duties certificate to an injured worker than GPs who saw less than 13 injured workers over eight years. In addition, it showed that some groups of injured workers (i.e., older age, workers with mental health issues, in rural areas) were less likely to receive alternate/modified duty certificates [52].

There is a need to train and prepare residents to complete functional capacity assessments. Sekoni and Jamil demonstrated that a curricular intervention to prepare residents to complete a focused functional capacity assessment during a 30-min office visit can reduce anxiety, frustration and time required to complete related paperwork among family or internal medicine residents. This translates to practicing physicians that are more comfortable with the Social Security Administration process of disability determination. The societal benefits are timely and accurate information that will expedite the disability process, and in some cases may allow determination to be made without requiring additional resources [53].

Knowledge Regarding Environmental Exposures

There is a need to train physicians about environmental exposures and intolerances. A study with 14 women who attributed their symptoms and illness to either dental restorative materials and/or electromagnetic fields found that during consultations, caregivers feel frustrated when they can neither understand nor help patients with environmental intolerance and symptoms attributed to dental materials. Based on the informants’ descriptions, conflicts could have arisen from the fact that doctors or dentists did not understand the patient’s experience of illness [54].

Knowledge Regarding Disclosure of Relevant Medical Information

In the field of mental disorders, there are some arguments about disclosure of relevant medical information due to the risk of stigmatization. This study involved multiple healthcare professions and concluded that a stronger emphasis should be put on the communication between the stakeholders as well as respectful communication about the changed performance profile of the patient. All stakeholders acknowledged that open communication about common mental disorders is difficult due to the risk of stigmatization. The patient’s fear and communication of their performance profile (e.g., work-related limitations) would indirectly disclose their diagnosis. Therefore, stronger emphasis should be put on the communication between the stakeholders as well as trustful communication about the changed performance profile of the patient [55].

Knowledge about Prognosis Related to RTW

There is a need to disseminate knowledge regarding prognosis to return to work for a variety of illnesses and injuries. A study showed that general practitioners’ referrals to orthopaedic surgery do not happen at the optimal time and the patients do not receive the best information pre-operatively to make informed decisions, especially around their future levels of work performance [56]. A study with healthcare providers from various occupations showed that there are disagreements between healthcare professions on some factors that predict RTW after surgery for a non-traumatic upper extremity condition [57]. A judgment analysis showed that GPs judgment of future risk of disability for chronic low back pain was less consistent than their judgments of current case severity and they were less able to base a judgment of future disability on the five information cues of self-esteem, motivation, sleep, pain right now, and mobility than they were then judging current case severity [58]. A randomized trial with medical students and GP trainees demonstrated that providing an educational intervention may result in gains in relevant biopsychosocial knowledge, overcoming potential attitude barriers to applying a biopsychosocial perspective and facilitating development of judgment-making more aligned with the biopsychosocial perspective when considering chronic low back pain patients’ future risks of disability [59]. A study with family medicine residents showed a lack of knowledge about counseling patients with concussion with respect to return to play, work, or learning [60].

Cancer patients returning to work may pose additional concerns to physicians. A study with multiple primary healthcare practitioners who provide cancer care, including 41 general practitioners, showed that most psychosocial topics are “sometimes” or “regularly” discussed, however sexuality and return to work are rarely mentioned [61]. Another study in oncology patients showed that the relationship between the perceived benefits of RTW and the perception that responsibility for RTW is part of one’s professional role is stronger when the healthcare team responsibility for RTW is low than when it is high [33]. A study including healthcare providers, vocational service providers, community service providers and health advocates in assisting cancer survivors found that stigma and discrimination can create many immediate and long-term negative consequences for cancer survivors. Survivors require guidance to decide whether to disclose their cancer, how to respond to discriminatory behaviours and how to best state their needs for workplace accommodations [62].

Knowledge Regarding Specific Populations

Physicians and interprofessional healthcare professionals need to be prepared to provide assistance with adolescents’ work-related injuries. A study showed that nurse practitioners serve as primary healthcare providers for adolescents who present with work-related injuries and 43% reported being uncomfortable or very uncomfortable treating them. Previous experience and male gender were associated with greater likelihood of feeling comfortable. This study demonstrates the need for educational and outreach efforts to better prepare nurse practitioners to treat adolescents’ with work-related injuries [63]. Another study showed that general practitioners need knowledge about how to help pregnant workers to SAW. Physicians are reluctant to prescribe medications to treat nausea and vomiting during pregnancy, and provide sick leave often or enable the woman to work part-time [64].

Awareness of Available Resources

This scoping review identified that physicians need to be aware of relevant services for injured or ill workers, and available tools to help them in the management of their patients with work-related injuries or diseases.

Awareness of Relevant Services

A study with general practitioners showed that primary care physicians were not aware of relevant services they could refer patients to, such as occupational therapy support. There was a lack of awareness of invisible impairments and uncertainty about how physicians could help in time-limited consultations; and the complexity of return-to-work issues [29].

Another study of general practitioners highlighted the important role of the RTW coordinator at the workplace in facilitating a successful RTW for injured workers [65].

Awareness of Relevant Tools

A study of healthcare providers from different clinical specialities showed that GPs perceived that an evidence-based medicine (EBM) tool in the workers’ compensation setting could potentially have some advantages, such as reducing inappropriate treatment or over-servicing, and providing guidance for clinicians. However, participants expressed substantial concerns that the EBM tool would not adequately reflect the impact of psychosocial factors on recovery. They also highlighted a lack of timeliness in decision making and proper assessment, particularly in pain management [66].

Discussion

We found four areas of physicians’ learning needs. One area was related to administrative tasks. These tasks refer to all activities of running their practice as a business, such as record keeping, time management, communication with other parties, and collaboration with other stakeholders. A second area of learning need relates to attitudes and beliefs that physicians have when facing a situation in which their patient needs their assistance to SAW or RTW. We found that there are intrinsic biases among healthcare professionals that may hinder the process. Many studies highlighted a lack of self-confidence among physicians, and barriers related to how physicians view their roles and their business. There is a need for clarity of physicians’ roles in the process of treating ill or injured workers. There appears to be a culture of blaming the patient for their lack of motivation to return to work. A third area relates to gaps in specific medical knowledge, such as assessments, environmental exposures, disclosure of relevant medical information, prognosis related to RTW, and special populations such as adolescents and pregnant women. Lastly, we found that physicians need to be aware of services and tools that exist to assist them in returning their patient to work.

Our scoping review focused on the learning needs of primary care physicians’ in helping workers to SAW or RTW after an injury or illness. The included studies used a variety of methods to identify these learning needs, including questionnaires, surveys, interviews, and focus groups. The 44 included studies were published in the past 5 years and were conducted in North America, Europe, Australia, and Israel. The compiled list of learning needs may not be exhaustive, but provides a general sense that there is a need to provide medical education to front line primary care providers on RTW and SAW. The topics generated by these 44 studies provide a comprehensive idea for a didactic curriculum that could be applied to teaching family medicine, general internal medicine, emergency medicine, rehabilitation medicine, nurse practitioners and allied healthcare professionals.

Strengths and Limitations

Our methods to conduct this scoping review followed recommended methodologies to avoid bias in the searches, selection and synthesis of data. However, our scoping review is limited to publications since 2016 due to constraints in time and resources for this project. The wide number of countries from which we found literature on this topic is both a strength and a limitation. It is limiting because there may be jurisdiction and health system-specific issues. However, it is a strength because despite any national differences, a commonality has been revealed in the four themes identified. There is no doubt that being in well supported and safe work is good for people, and family physicians need to advocate for their patients in an informed manner. The burdens of time constraints and what can be seen as bureaucracy are universal. Our findings are similar to Kosny et al., that physicians and other healthcare professionals can improve outcomes for injured workers, however, many of these opportunities are missed due to uncertainties about physician’s roles, vagueness and lack of clarity in various resources aimed at physicians, lack of knowledge about complex and invisible conditions (chronic pain, mental health, substance use), and barriers to effective collaboration [24].

Future Research

We identified various studies that included an educational intervention aimed at physicians. It is important that future studies include detailed follow-up of patients with a workplace component [25]. There is a need to explore the role of various healthcare professionals such as vocational rehabilitation and medical assistants on the RTW process, especially in practices where physicians do not have access to an interprofessional team or specialized occupational medicine consultants [26]. Future research needs to consult all interested stakeholders, including insurers and employers [31]. Studies need to have an adequate sample size to allow exploration of the potential variables in terms of professional experiences and workplaces.

The extant evidence supports rehabilitation professionals’ role in RTW yet their limited knowledge may be a barrier to this process [67,68,69,70]. Our results indicate examining the learning needs of rehabilitation professionals in the coordination of services between different stakeholders in supporting RTW. Moreover, demonstrating the potential utility of investigating the learning needs of rehabilitation professionals through an interdisciplinary perspective in improving the transition of care. Specifically, future studies may explore the need to further improve interprofessional education, training, and mentorship of health professionals to address gaps in improving the coordination of services between different stakeholders.

Large numbers of participants for each professional group will enable examination of each profession separately [33]. It is also important to explore cross-cultural differences in the extent to which healthcare professionals view RTW as part of their role. Issues related to healthcare professionals’ education, workload and role definitions, as well as cultural characteristics, such as collectivistic vs. individualistic orientation, might affect professionals’ views regarding responsibility for RTW [33].

Some interpretations of intrinsic biases need to be confirmed in future studies [34]. Future work is needed to elucidate which pain-related decisions are most influenced by patient race and SES and provider attitudes, as well as the environmental conditions that amplify or diminish these effects [34]. Other race/ethnic groups and SES categories (e.g., blue collar, middle class) should be considered in future studies. Additionally, other indicators of SES (e.g., education) may affect provider decisions in real clinical settings [34].

There is a need for larger scale research to explore the extent and impact of reluctance and refusal to treat, and how to effectively address it, so that patients with compensable injuries can access the care they need [37]. Future research should include the experiences of GPs from various locations alongside the views of specialists and allied health professionals.

More research is needed to improve our knowledge of the occupational health needs of the population that the fit note is designed to support [35].

Future research is needed to determine how to support physicians in coping with the sickness absence certification problems that are only partly related to the medical profession [39].

Conclusions

There are opportunities to improve primary care for workers with an illness or injury that affect their work. We identified various learning needs that could be included in didactic curricula to physicians in residency or in continuing medical education. More research is needed to test interventions aimed at filling these gaps in learning needs.

References

Carey TS, Hadler NM. The role of the primary physician in disability determination for social security insurance and workers’ compensation. Ann Intern Med. 1986;104(5):706–710.

Kosny A, MacEachen E, Ferrier S, et al. The role of health care providers in long term and complicated workers’ compensation claims. J Occup Rehabil. 2011;21(4):582–590.

Wanberg CR. The individual experience of unemployment. Annu Rev Psychol. 2012;63:369–396.

Hildebrandt J, Pfingsten M, Saur P, et al. Prediction of success from a multidisciplinary treatment program for chronic low back pain. Spine. 1997;22(9):990–1001.

Scheel IB, Hagen KB, Oxman AD. Active sick leave for patients with back pain: all the players onside, but still no action. Spine. 2002;27(6):654–659.

Canadian Medical Association. The treating phyisicians role in helping patients return to work after an illness or injury 2013. https://policybase.cma.ca/documents/policypdf/PD13-05.pdf Accessed 15 Mar 2022.

Academy of Medical Royal Colleges. 2019 Healthcare professionals’ Consensus Statement for Action Statement for Health and Work 2019. https://www.aomrc.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/Health-Work_Consensus_Statement_090419.pdf Accessed 1 Oct 2020.

Talmage JB, Mehorn J, Hyman M (2011) Why staying at work or returning to work is in the patient’s best interest. In: Talmage JB, Mehorn J, Hyman M, editors. AMA guides to the evaluation of work ability and return to work. 2nd ed. Chicago, IL

Papagoras H, Pizzari T, Coburn P, et al. Supporting return to work through appropriate certification: a systematic approach for Australian primary care. Aust Health Rev. 2018;42(2):164–167.

Alvino EC, Ahmad TM. How to determine whether our patients can function in the workplace: a missed opportunity in medical training programs. Permanente Journal. 2019;23:18–259.

Kosny A, Lifshen M, MacEachen E, et al. What are physicians told about their role in return to work and workers’ compensation systems? An analysis of Canadian resources. Policy and Practice in Health and Safety. 2019;17(1):78–89.

The Association of Worker’s Compensation Boards of Canada. National work injury, disease and fatality statistics Mississauga, ON, Canada: The Association of Worker’s Compensation Boards of Canada; 2015. https://awcbc.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/2012-2014-NWISP-Publication-for-2015.pdf Accessed 15 Mar 2022.

International Labour Organization. The prevention of occupational diseases Switzerland: International Labour Organization; 2013. https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_protect/---protrav/---safework/documents/publication/wcms_208226.pdf Accessed 1 Oct 2020.

Nelson DI, Nelson RY, Concha-Barrientos M, et al. The global burden of occupational noise-induced hearing loss. Am J Ind Med. 2005;48(6):446–458.

Punnett L, Prüss-Ütün A, Nelson DI, et al. Estimating the global burden of low back pain attributable to combined occupational exposures. Am J Ind Med. 2005;48(6):459–469.

Trupin L, Earnest G, San Pedro M, et al. The occupational burden of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur Respir J. 2003;22(3):462–469.

Morabia A, Markowitz S, Garibaldi K, et al. Lung cancer and occupation: results of a multicentre case-control study. Br J Ind Med. 1992;49(10):721–727.

Blanc PD, Toren K. How much adult asthma can be attributed to occupational factors? Am J Med. 1999;107(6):580–587.

Beach J, Cherry N. Course participation and the recognition and reporting of occupational ill-health. Occup Med. 2019;69(7):487–493.

Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32.

Cochrane Training. Scoping reviews: what they are and how you can do them: Cochrane; 2017. https://training.cochrane.org/resource/scoping-reviews-what-they-are-and-how-you-can-do-them Accessed 1 Oct 2020.

Irvin E, Van Eerd D, Amick BC 3rd, et al. Introduction to special section: systematic reviews for prevention and management of musculoskeletal disorders. J Occup Rehabil. 2010;20(2):123–126.

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA Extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–473.

Kosny A, Lifshen M, Tonima S, et al. (2016) The role of health-care providers in the workers' compensation system and return-to-work process: final report. Toronto: Institute for Work & Health

Atkins S, Reho T, Talola N, et al. Improved recording of work relatedness during patient consultations in occupational primary health care: a cluster randomized controlled trial using routine data. Trials. 2020;21(1):256.

Simmons JM, Liebman AK, Sokas RK. Occupational health in community health centers: practitioner challenges and recommendations. New Solut. 2018;28(1):110–130.

Aarseth G, Natvig B, Engebretsen E, et al. “Working is out of the question”: a qualitative text analysis of medical certificates of disability. BMC Fam Pract. 2017;18(1):55.

Gray SE, Brijnath B, Mazza D, et al. Australian general practitioners’ and compensable patients: factors affecting claim management and return to work. J Occup Rehabil. 2019;29(4):672–678.

Balasooriya-Smeekens C, Bateman A, Mant J, et al. How primary care can help survivors of transient ischaemic attack and stroke return to work: focus groups with stakeholders from a UK community. Br J Gen Pract. 2020;70(693):e294–e302.

Christie N, Beckett K, Earthy S, et al. Seeking support after hospitalisation for injury: a nested qualitative study of the role of primary care. Br J Gen Pract. 2016;66(642):e24–e31.

Sylvain C, Durand MJ, Maillette P, et al. How do general practitioners contribute to preventing long-term work disability of their patients suffering from depressive disorders? A qualitative study BMC Fam Pract. 2016;17:71.

Vanmeerbeek M, Govers P, Schippers N, et al. Searching for consensus among physicians involved in the management of sick-listed workers in the Belgian health care sector: a qualitative study among practitioners and stakeholders. BMC Public Health. 2016;16(1):164.

Yagil D, Eshed-Lavi N, Carel R, et al. Return to work of cancer survivors: predicting healthcare professionals’ assumed role responsibility. J Occup Rehabil. 2019;29(2):443–450.

Anastas TM, Miller MM, Hollingshead NA, et al. The unique and interactive effects of patient race, patient socioeconomic status, and provider attitudes on chronic pain care decisions. Ann Behav Med. 2020;54(10):771–782.

Dorrington S, Carr E, Stevelink SAM, et al. Demographic variation in fit note receipt and long-term conditions in south London. Occup Environ Med. 2020;77(6):418–426.

Riiser S, Haukenes I, Baste V, et al. Variation in general practitioners’ depression care following certification of sickness absence: a registry-based cohort study. Fam Pract. 2021;38(3):238–245.

Brijnath B, Mazza D, Kosny A, et al. Is clinician refusal to treat an emerging problem in injury compensation systems? BMJ Open. 2016;6(1): e009423.

Mandal R, Dyrstad K. Explaining variations in general practitioners’ experiences of doing medically based assessments of work ability in disability benefit claims a survey-based analysis. Cogent Medicine. 2017;4(1):1368614.

Hinkka K, Niemela M, Autti-Ramo I, et al. Physicians’ experiences with sickness absence certification in Finland. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health. 2019;47(8):859–866.

Yanar B, Kosny A, Lifshen M. Perceived role and expectations of health care providers in return to work. J Occup Rehabil. 2019;29(1):212–221.

Lippel K, Eakin JM, Holness DL, et al. The structure and process of workers’ compensation systems and the role of doctors: a comparison of Ontario and Quebec. Am J Ind Med. 2016;59(12):1070–1086.

Moßhammer D, Michaelis M, Mehne J, et al. General practitioners’ and occupational health physicians’ views on their cooperation: a cross-sectional postal survey. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2016;89(3):449–459.

Stratil J, Rieger MA, Voelter-Mahlknecht S. Optimizing cooperation between general practitioners, occupational health and rehabilitation physicians in Germany: a qualitative study. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2017;90(8):809–821.

Sanders T, Wynne-Jones G, Nio Ong B, et al. Acceptability of a vocational advice service for patients consulting in primary care with musculoskeletal pain: a qualitative exploration of the experiences of general practitioners, vocational advisers and patients. Scandinavian J Public Health. 2019;47(1):78–85.

Lundberg T, Melander S. Key push and pull factors affecting return to work identified by patients with long-term pain and general practitioners in sweden. Qual Health Res. 2019;29(11):1581–1594.

Bertilsson M, Maeland S, Love J, et al. The capacity to work puzzle: a qualitative study of physicians’ assessments for patients with common mental disorders. BMC Fam Pract. 2018;19(1):1–4.

de Kock CA, Lucassen PLBJ, Spinnewijn L, et al. How do Dutch GPs address work-related problems? A focus group study. European Journal of General Practice. 2016;22(3):169–175.

de Kock CA, Lucassen P, Bor H, et al. Training GPs to improve their management of work-related problems: results of a cluster randomized controlled trial. European Journal of General Practice. 2018;24(1):258–265.

King R, Murphy R, Wyse A, et al. Irish GP attitudes towards sickness certification and the “fit note.” Occup Med. 2016;66(2):150–155.

Godycki-Cwirko M, Nocun M, Butler CC, et al. Family practitioners’ advice about taking time off work for lower respiratory tract infections: a prospective study in twelve European primary care networks. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(10): e0164779.

Nordhagen HP, Harvey SB, Rosvold EO, et al. Case-specific colleague guidance for general practitioners’ management of sickness absence. Occup Med. 2017;67(8):644–647.

Ruseckaite R, Collie A, Scheepers M, et al. Factors associated with sickness certification of injured workers by General Practitioners in Victoria. Australia BMC Public Health. 2016;16:298.

Sekoni KI, Jamil H. Completing disability forms efficiently and accurately: curriculum for residents. Primer. 2018;2:9.

Marell L, Lindgren M, Nyhlin KT, et al. “Struggle to obtain redress”: women’s experiences of living with symptoms attributed to dental restorative materials and/or electromagnetic fields. Int J Qual Stud Health Well Being. 2016;11:32820.

Scharf J, Angerer P, Muting G, et al. Return to work after common mental disorders: a qualitative study exploring the expectations of the involved stakeholders. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(18):6635.

Coole C, Nouri F, Narayanasamy M, et al. Total hip and knee replacement and return to work: clinicians’ perspectives. Disabil Rehabil. 2021;43(9):1247–1254.

Peters SE, Coppieters MW, Ross M, et al. Health-care providers’ perspectives on factors influencing return-to-work after surgery for nontraumatic conditions of the upper extremity. J Hand Ther. 2020;33(1):87–87.

Dwyer CP, MacNeela P, Durand H, et al. Judgment analysis of case severity and future risk of disability regarding chronic low back pain by general practitioners in Ireland. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(3): e0194387.

Dwyer CP, MacNeela P, Durand H, et al. Effects of biopsychosocial education on the clinical judgments of medical students and GP trainees regarding future risk of disability in chronic lower back pain: a randomized control trial. Pain Med. 2020;21(5):939–950.

Mann A, Tator CH, Carson JD. Concussion diagnosis and management: knowledge and attitudes of family medicine residents. Can Fam Physician. 2017;63(6):460–466.

Schouten B, Bergs J, Vankrunkelsven P, et al. Healthcare professionals’ perspectives on the prevalence, barriers and management of psychosocial issues in cancer care: a mixed methods study. Eur J Cancer Care. 2019;28(1): e12936.

Stergiou-Kita M, Pritlove C, Kirsh B. The, “Big C”: stigma, cancer, and workplace discrimination. J Cancer Surviv. 2016;10(6):1035–1050.

Graves JM, Klein TA. Nurse practitioners’ comfort in treating work-related injuries in adolescents. Workplace Health Saf. 2016;64(9):404–413.

Heitmann K, Svendsen HC, Sporsheim IH, et al. Nausea in pregnancy: attitudes among pregnant women and general practitioners on treatment and pregnancy care. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2016;34(1):13–20.

Bohatko-Naismith J, Guest M, James C, et al. Australian general practitioners’ perspective on the role of the workplace Return-to-Work Coordinator. Aust J Prim Health. 2018;24(6):502–509.

Elbers NA, Chase R, Craig A, et al. Health care professionals’ attitudes towards evidence-based medicine in the workers’ compensation setting: a cohort study. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2017;17:1–12.

King J, Cleary C, Harris MG, et al. Employment-related information for clients receiving mental health services and clinicians. Work. 2011;39(3):291–303.

Unger D, Kregel J. Employers’ knowledge and utilization of accommodations. Work. 2003;21(1):5–15.

McDowell C, Fossey E. Workplace accommodations for people with mental illness: a scoping review. J Occup Rehabil. 2015;25(1):197–206.

Corbière M, Mazaniello-Chézol M, Bastien MF, et al. Stakeholders’ role and actions in the return-to-work process of workers on sick-leave due to common mental disorders: a scoping review. J Occup Rehabil. 2020;30(3):381–419.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Joanna Liu for library support and to acknowledge the following people for helping to determine relevance of non-English language studies: Morgane Le Pouesard, Heather Johnston, Paolo Maselli, Joanna Liu, Hitomi Suzuki, Rina Shoki, Sylvia Snoeck-Krygsman, Mariska de Wit, and Tania Bruno.

Funding

This project was funded by a Research Grant from the Ontario Workplace Safety and Insurance Board (WSIB).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Furlan, A.D., Harbin, S., Vieira, F.F. et al. Primary Care Physicians’ Learning Needs in Returning Ill or Injured Workers to Work. A Scoping Review. J Occup Rehabil 32, 591–619 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-022-10043-w

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-022-10043-w