Abstract

Purpose: The objective of this study was to explore how workers’ compensation policies related to healthcare provision for workers with musculoskeletal injuries can affect the delivery and trajectories of care for injured workers. The principal research question was: What are the different ways in which workers’ compensation (WC) policies inform and transform the practices of healthcare providers (HCPs) caring for injured workers? Methods: We conducted a cross-jurisdictional policy analysis. We conducted qualitative interviews with 42 key informants from a variety of perspectives in the provinces of Ontario and Quebec in Canada, the state of Victoria in Australia and the state of Washington in the United States. The main methodological approach was Framework Analysis. Results: We identified two main themes: (1) Shaping HCPs’ clinical practices and behaviors with injured workers. In this theme, we illustrate how clinical practice guidelines and non-economic and economic incentives were used by WCs to drive HCP’s behaviours with workers; (2) Controlling workers’ trajectories of care. This theme presents how WC policies achieve control of the workers’ trajectory of care via different policy mechanisms, namely the standardization of care pathways and the power and autonomy vested in HCPs. Conclusions: This policy analysis shed light on the different ways in which WC policies shape HCP’s day-to-day practices and workers’ trajectories. A better understanding and a nuanced portrait of these policies’ impacts can help support reflections on future policy changes and inform policy development in other jurisdictions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In jurisdictions where workers’ compensation systems exist, musculoskeletal injuries and disorders typically account for a large portion of these claims [1,2,3,4,5]. Previous studies in the field of musculoskeletal disorders and injuries have explored the various roles and responsibilities of healthcare providers (HCPs) caring for injured workers in the compensation system. These studies shed light on difficulties faced by HCPs when offering care to workers supported by a workers’ compensation system including compensation administrative hurdles, lack of both communication between the different stakeholders and coordination of care, inadequacy of remuneration fees, restrictions in professional autonomy and marginality of opinions within the system [6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15]. Kosny and her team, via a Canadian multi-province project, summarized the problem by describing the apparent rigidity of compensation systems that pose significant challenges for professionals involved [9]. Our recent critical interpretive synthesis of articles addressing first-line HCPs’ policies in four jurisdictions illustrated some ways in which workers’ compensation policies can affect healthcare provision [16]. The most salient themes related to how policies modulate access to care services for workers and affect the roles of HCPs (e.g. gatekeeping, advocacy, form filling). MacEachen and Ekberg also suggest that HCPs are more and more “accountable to government-benefit providers and less directly accountable to workers as patients and benefit claimants” [17]. They also raised the issue of reduced autonomy of treating healthcare providers across different jurisdiction in providing and organizing care for injured workers as per recent changes in workers’ compensation policies [17].

Amidst the important body of literature presenting the challenges faced by HCPs when caring for injured workers, very few comparative empirical projects have been specifically designed to compare, at the policy level, the impact of workers’ compensation policies on HCPs’ work with injured workers and its ripple effect on workers’ care [6, 9, 18]. For example, in their 2016 study, Lippel and colleagues investigated the relationship between the roles, practice and experiences of physicians and the features of workers’ compensation systems in two distinct Canadian provinces (Ontario and Quebec) [6]. The authors demonstrated that, in both workers’ compensation systems, physicians lack decision-making power with respect to decisions on about the work relatedness of a claim and that their role and input are usually constrained and limited by the administrative forms from WCB (e.g., only tick-box available for some questions). In both provinces, physicians also described being reluctant to treat injured workers because of bureaucracy associated with the systems. Similar findings about reluctance to treat were found for physiotherapists in Quebec, Ontario and British-Colombia in a study by Hudon and colleagues [18] and in an Australian study based in Victoria, by Brijnath and colleagues [14]. Lippel and colleagues also highlighted provincial differences with regard to the weight accorded to physicians’ opinions by the WCB (heavier weight in Quebec, lesser weight in Ontario), for example, with regard to the determination of diagnosis, treatments prescribed and recommendations for modified work [6]. These elements were found to have different impacts on workers’ trajectories of care in the two jurisdictions; for instance, potential for rejection of the claim and increased likelihood of medico-legal disputes in Quebec, and outsourcing of workers’ assessment and bypass of physicians’ opinions in Ontario. The authors showed how the complex dynamics at play in these two systems affected the provision of care for workers and concluded that “findings in any given jurisdiction may reflect a system effect rather than the effect of the actual [healthcare] intervention” [6]. (p. 15). Kosny and colleagues in their 2016 report described results of qualitative interviews with 97 healthcare providers and 34 case managers across four Canadian provinces (British Columbia, Manitoba, Ontario and Newfoundland and Labrador) [9]. Although the findings demonstrate important challenges for healthcare providers across provinces, very few specific distinctions were presented between them, which limits the possibility of comparisons and the capacity to envision the impact of the different policies at play in each province. In their 2018 paper, Hudon and colleagues highlighted several differences between WCBs’ policies with regards to physiotherapy care [18]. They showed that predetermined blocs of physiotherapy treatment, restricted to a set number of weeks could induce professionals to pressure patients into returning to work before they are ready to do so. They also showed that this type of policy led some physiotherapy clinics in British Columbia and Ontario to internally limit the number of treatment sessions provided by their therapists within the bloc of care, regardless of the patients’ conditions. Even if some policies were judged to have some negative repercussions on the workers, other policies were perceived positively, such as a WCB policy in Ontario requiring physiotherapy to use a specific and well-recognized functional outcomes measure to re-evaluate the workers’ progression in physiotherapy. Overall, similar to the 2016 Lippel study, the participants in this comparative study were most often unaware of the different ways in which the WCB policies in their own province shaped their everyday practices.

It is important to note that, although these studies investigated the experiences of HCPs and compared them across compensation systems, they did not include the perspectives of other important stakeholders in the workers’ compensation realm, namely the injured workers themselves, the policy-makers from the WCB and the views of researchers. The inclusion of these other stakeholders would certainly provide a more comprehensive view of the influences of workers’ compensation policies on the provision of healthcare to injured workers. All of these qualitative studies also compared jurisdictions situated within the same country (Canada), and this is also the case for recent quantitative studies comparing outcomes of care for workers in different jurisdictions [19,20,21]. Indeed, it is interesting to see that a growing number of quantitative studies have recently been published in the workers’ compensation field using available compensation data to better highlight the impacts of policy differences on workers’ outcomes [22,23,24]. However, very few studies have taken a qualitative approach to try to investigate the perspectives of the different stakeholders whose work and health are affected by the workers’ compensation policies in place.

This article’s systemic perspective on the current policies informing healthcare services provided to injured workers thus responds to important identified gaps in the workers’ compensation literature. By expanding the number of groups of stakeholders included in the project and by employing a qualitative stance to explore these people’s perspectives in three different countries, it is well designed to shed light on the distinct ways in which workers’ compensation policies influence the work of HCPs and ultimately impact the workers’ trajectories of care and return to work.

Context of Study

The main objective of this study was to explore how workers’ compensation policies related to healthcare provision for workers with musculoskeletal injuries can affect the delivery and trajectories of care for injured workers.

To provide interesting comparisons that allow for exploration of similarities and distinctions in the policies governing healthcare provision in compensation systems, we focused our work on four jurisdictions situated in three countries: the provinces of Ontario and Quebec in Canada, the state of Victoria in Australia and the state of Washington in the United States. Table 1 describes the main features of the compensation systems in these jurisdictions.

For each of these four jurisdictions, a workers’ compensation law or act exists at the provincial/state level. The workers’ compensation act formally enshrines in legislation the rights of workers following work-related injury or illness and the duties of the different parties with regard to compensation following this injury. Across jurisdictions, these laws vary because each has been established historically by the government holding power in each jurisdiction at the time of their adoption and are based on the local socio-political context. Each of the four laws displayed in Table 1 is thus intrinsically linked to the social paradigms at play during their adoption in the jurisdiction. In Ontario, Quebec, Victoria and Washington, the state/provincial-level WCB is the regulatory agency responsible for establishing specific policies flowing from these laws, as well as for orchestrating the day-to-day operations supporting workers’ compensation process. The compensation laws in the province or state thus articulate the larger principles of the compensation processes, while the WCBs have the mandate of enforcing these laws. To do so, WCBs have some discretionary authority to develop specific policies that will regulate the functioning of the compensation system, in accordance with the overarching law. In these four jurisdictions, apart from insuring the operationalization and enforcement of the compensation law, the WCBs are also responsible for administering the insurance fund and insuring the financial viability and sustainability of the compensation scheme.

In this study, we selected four jurisdictions where support following a work injury is situated within a cause-based paradigm. A cause-based paradigm in the workers’ compensation realm means that claimants can receive coverage and compensation (e.g., salary support, medical benefits and rehabilitation) only if they can demonstrate that their injury, condition or illness has been caused by their work [25]. Thus, workers can only be compensated under these systems if the aetiology of their condition can be linked to their work. Cause-based workers’ compensation systems mainly exist in North America and in Australia, and are Bismarck-type systems [26]. These systems present similar broad characteristics in terms functioning (e.g., have a form of workers’ compensation law and are modelled on similar premises) which makes them easier to compare on systemic and paradigmatic levels. This is why we selected four compensation systems that operated with a cause-based paradigm for this project. However, it is important to note that each workers’ compensation system across states and provinces in the United States, Canada and Australia also present important dissimilarities with regards to their legislation and policies, as shown in Table 1. This allows for interesting comparisons between these systems. In this project, we were specifically interested to investigate how, among cause-based workers’ compensation systems, differences in compensation policies could influence the work of HCPs and the trajectories of workers.

In contrast, disability-based income support systems, mainly present in Scandinavian countries and United Kingdom, provide support to people injured at work or living with a disability regardless of cause (these are Beveridge-type systems) [26]. This is also the case in the Netherlands, for example, where there exists a disability and insurance scheme that does not differentiate between work-related and non-work-related disability. It is important to note that in other European countries, such as France and Belgium, some workers’ compensation systems do exist, but the emphasis on the work-related nature of the injury is much less, and benefits receive only minimally differ between those with work or non-work injuries or illnesses [25].

All in all, this classification of systems helps improve our understanding of the major commonalities and differences between the systems and provides a rationale for our study’s focus on jurisdictions that were situated within the same overarching paradigm. Our selection of the jurisdictions of Ontario, Quebec, Victoria and Washington was thus based on major similarities within their workers’ compensation systems: notably, that they are cause-based, financed by employers’ premiums and administered by a WCB that has the mandate to oversee the operationalization of the compensation legislation. They were also chosen because they are situated within three different countries, each with an important body of scientific literature available on the work of healthcare providers within the workers’ compensation system [16] and presented interesting differences with regards to healthcare policy.

Methods

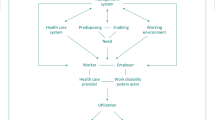

We conducted a cross-jurisdiction policy analysis using key informant qualitative interviews. In this project, key informants were conceptualized as people with different perspectives (i.e., workers’, employers’, workers’ compensation’, healthcare providers’ perspectives and researchers) who could speak of their wide ranging and informed experiences of healthcare provision for injured workers in their jurisdiction’s workers’ compensation system. Two methodological approaches and frameworks framed this policy analysis. The main approach used was Framework Analysis, for policy review [27, 28]. To accomplish the policy analysis, we also used analytical steps derived from Grounded Theory [29]. Framework Analysis (FA) is an approach that was developed to conduct applied qualitative policy research. It is a dynamic and structured process that creates a comprehensive picture of the policy aspects studied, relying on the original accounts of key informants [27, 28]. In this project, we borrowed from FA concepts to facilitate comparisons between the four jurisdictions studied and to highlight important features of workers’ compensation’s policies and procedures from the groups of people that they affect. The Grounded Theory (GT) approach aims to construct an emergent conceptual understanding of the studied phenomena through constant comparative analysis [29]. It aims to move beyond description of the concept by providing an analysis that brings innovative insights to the object of research. In this project, we used mostly analytical techniques from this approach (constant comparative technique, initial coding and categorizing) to add depth to the analysis and to better conceptualize the key informants’ data to bring new understandings of the policy schemes studied. We also consulted and used compensation laws in each of the selected jurisdictions to supplement our understanding of the policy context. As well, we consulted the websites of the workers’ compensation boards in each of the four jurisdictions.

Findings emerging from this study are grounded within the social, political and ideological complexities of practice and ultimately aim to generate applied reflections on current policies and their clinical and social impacts [28]. In this study, the following key question led our research endeavour: “What are the different ways in which workers’ compensation boards and policies, in the four different jurisdictions studied, inform and transform the practices of healthcare providers caring for injured workers?” An important sub-question was “How can these policies and consequent HCPs’ practices affect the trajectories of care for workers?”.

The cross-jurisdictional policy analysis supported by the two identified methodological frameworks helped us to ground our analysis in policy contexts and to unearth the rich and varied perspectives of the key informants included in the study. Together, these shed light on the impact of compensation policies on healthcare for injured workers in a situated and contextualized manner.

Recruitment Process

We aimed to recruit seven to 10 participants per jurisdiction. A purposive sampling strategy was used to recruit key informants between June 2018 and February 2019. These key informants had to belong to at least one of these five predetermined categories or “social locations”: (1) injured worker representative or advisor; (2) healthcare provider, (3) workers' compensation board employee in a policy role or person in a leadership position or committee at the WCB, (4) person in a leadership position in an organization supporting or advising employers, and (5) researcher working in the field of workers’ compensation policies and/or healthcare services. We used three different recruitment strategies to target these groups in each jurisdiction: (1) emails to our contacts to help identify informants; (2) consultation of websites of key organizations in each jurisdiction and emails to their generic address, and; (3) snowball sampling where some participants directly referred us to others who might provide relevant input on the subject. We also sought to include HCPs from the four main professions highly involved with workers with MSK injuries across these jurisdictions: physicians (general practitioners and specialists), physiotherapists, chiropractors and osteopaths. To be included as informants in this project, participants had to be in a position that would allow them to have good knowledge of the object of the study (i.e. workers’ compensation policies in their respective jurisdiction) and had to be knowledgeable about the work of HCPs in relation to injured workers and of policies overseeing the provision of healthcare for injured workers in their jurisdiction.

Sample

We recruited 42 participants. Table 2 presents their distribution across jurisdictions and participant categories. No formal demographic data was collected from the participants since many of them occupied strategic policy or research positions and we wanted to preserve their anonymity. However, to obtain a rich understanding of the social location of each participant, which is a crucial element in FA and GT qualitative approaches, each participant described his or her role and current and past experiences in the field at the beginning of each interview. All five categories were represented in each jurisdiction, except in Quebec where we were unable to secure a WCB interview.

Collection of Data

We used in-depth, semi-structured interviews to collect data. An interview guide was first designed based on the results from our critical interpretive synthesis review [16]. The guide was successfully pilot tested with the first key informant participant. Forty-one semi-structured interviews with 42 participants were conducted (one interview included two participants). All interviews were conducted by the first author via videoconference (n = 21) or phone (n = 20), and conducted in English or French, according to the participant’s preference. The interviews lasted between 48 and 120 min, with a mean length of 76 min. They were audiotaped and transcribed verbatim by two professional transcriptionists (one for English and one French interviews). All participants provided informed consent to participate.

Data Analysis

As per the familiarization step of FA [27], the first author first relistened to all interviews to correct any mistakes in the transcripts and write analytic memos to start the analysis process. The first author then conducted initial coding for each transcript by selecting segments of data and inductively attributing code names, with the support of NVivo 11 software [29]. The codes represented key ideas or meanings in these segments (e.g., harm reduction, incentives). At this stage, constant comparative methods created links between transcripts to identify common or divergent patterns across the whole dataset. From this process, a thematic framework (step 2 in FA) started to emerge. Step 3 (indexing) and 4 (charting) from the FA approach were conducted in parallel to the coding process. Using the inductive codes and the ongoing organization of data through steps 3, 4, and 5 (mapping and interpretation), the FA approach was completed. This was mainly done through conceptual mapping exercises and through the use of matrices comparing data across jurisdictions. At different points during the analysis, results were discussed by the three authors and attention was paid to contextual and policy differences between jurisdictions and to outliers’ perspectives in the data. The participants’ social locations (e.g., role or title in organization) were also considered. The first author was involved in all aspects of the study, ensuring a thorough understanding and a long-lasting involvement with the data. She used an audit trail to register all decisions related to the study methods and to track the important steps of the project. At different points during the study, she reflected on how her own positionality as a researcher exploring workers’ compensation system and her background as a physical therapy clinician could influence the data. The memos she took in her personal audit trail were also used to foster this reflexivity, as she not only described methodological decisions, but also noted personal reflections and spontaneous thoughts about her own assumptions and positionality with respect to the object of the study. The monthly meetings with her supervisors (EM and KL) on the conduct of the project also served to enhance this reflexivity as authors shared similar, but also dissimilar views and positions towards the data.

Results

The interviews conducted in the four jurisdictions led to the identification of two main themes. First, the results show that WCBs’ healthcare policies are designed to shape HCPs’ clinical practices with injured workers. To illustrate this, we present two types of policy incentives used by WCBs and show how they each drive HCPs’ behaviours with workers. Secondly, our findings present how WCBs’ policies achieve control of the workers’ trajectory of care via different policy mechanisms in place that impact the care services offered to workers. We examine two key mechanisms in detail in our results, namely the standardizing of care pathways and the power and autonomy vested in HCPs.

Across both main themes, we describe similarities and distinctions between the four jurisdictions studied to support a rich and nuanced understanding of the findings. Supporting citations from the interviews are used to illustrate results. When originally in French, the quotes were translated by a bilingual member of the research team and checked for preservation of the original meaning.

Shaping HCPs’ Clinical Practices and Behaviors with Injured Workers

Across jurisdictions, although workers’ compensation systems and policies differ, many commonalities were identified regarding the influence of WCB policies on framing HCP’s clinical practices and behaviors with their patients. Although the compensation laws in the four jurisdictions studied did not formally dictate the day-to-day practices of HCPs, numerous participants described strategies used by WCBs to oversee and influence professionals’ practices. The two main strategies discussed took the form of “workers’ compensation approved” clinical guidelines, which were supplemented by both non-economic inducements and the use of monetary incentives.

Clinical Guidelines and Non-economic Inducements

In Washington, the Department of Labor and Industries issued guidelines about “provision of safe, effective and cost-effective treatments” [30]. These guidelines were developed by the Industrial Insurance Medical Advisory Committee (IMAC), a committee mostly constituted of medical physicians appointed by the Department of Labor and Industries director. When discussing these guidelines, a workers’ representative raised the danger of having the WCB enforce strong incentives for the HCPs to abide strictly by these guidelines in their clinical decisions. More specifically, this participant was worried about the ways in which these guidelines were currently used, being mostly seen as prescriptive about what the HCPs should and should not do, and limiting latitude for the clinicians’ own judgment about the most appropriate interventions. For example, he talked about the workers’ compensation not allowing some medical interventions (e.g., installation of a spinal stimulator) to move forward as solely based on these guidelines. This participant thus stressed the necessity for these guidelines to stay informative and not prescriptive, and to allow HCPs to provide the care that is deemed to be the most appropriate for each worker.

“We don’t think those guidelines should be used to overturn the legitimate medical opinion of an attending physician, […] You know, it shouldn’t be kind of misrepresenting the guidelines as anything but guidelines.” Washington4—Workers’ group.

In Australia, WorkSafe Victoria issued a ‘Clinical Framework’ intended for HCPs use. This framework presents a set of five main guiding principles that HCPs are expected to adopt in their clinical practice with injured workers. These principles include, among others, the importance of adopting a biopsychosocial approach, of implementing functional and return to work goals and the importance of measuring the effects of treatment with standardized and validated measures. HCPs offering care to injured workers were expected to practice according to these general principles. Healthcare participants from Victoria mentioned that they perceived this framework favourably as it is not particularly prescriptive and generally aligns with what is recognized as good practice in their field and is supported by some HCPs’ associations (e.g. Australian Physiotherapy Association).

Some participants discussed the need to involve a diversity of HCPs on WCB committees that develop policy recommendations or decisions regarding injured workers’ care. One participant from Washington mentioned that there are about 14 physicians sitting on the Industrial Insurance Medical Advisory Committee (IIMAC), of which only one is a family physician and the rest are surgeons and specialists.

In Quebec and Ontario, no such guidelines framing HCPs’ practices were discussed by the participants. However, a participant from Quebec voiced concern about the potential interference of the WCB in the day-to-care clinical practice matters.

“Also, as the care is paid for by a third party payer, that payer thinks they have a say on relevant treatment” Québec8—HCPs’ group

Across jurisdictions, most participants were not in favor of having WBCs determine or interfere with the specifics of treatment modalities and interventions provided by HCPs. However, participants affiliated with WCBs or employers felt that more guidance in the form of clinical or best-practice guidelines should be provided to HCPs. In Quebec, the need to rely on ‘evidence-based practice’ was often used as an argument to justify the application of healthcare guidelines. Participants from the researchers’ and employers’ groups mentioned that there are important gaps between what is known in occupational health literature and the way HCPs currently practice, which means that, according to them, ‘best-practices’ are currently not followed.

“My fundamental idea is that we should put in place administrative procedures that make it possible to make the scientific knowledge that we have coincide as much as possible with practice… And things as stupid as administrative forms” Québec5—Employers’ group.

Although different clinical guidelines exist to guide some aspects of HCPs practice with injured workers, many participants described the difficulty of HCPs implementing the recommendations from these guidelines in their day-to-day practices and receiving training about occupational health knowledge. With regard to clinical guidelines, some participants from the HCPs and researchers group mentioned that these are generally very broad and thus vague in terms of implementation of clinical practices. For participants from the HCPs’ group, the balance between providing care that has been labeled by the WCB as ‘evidence-based’ and using their contextual knowledge of the particular condition and situation to make decisions on care interventions was highlighted. A researcher participant described the ‘black and white’ nature of these guidelines as a factor that could lead to difficulties of uptake by HCPs, saying that these guidelines should incorporate more nuances. Many participants affiliated with WCBs and from the research field said that providing HCPs with guidelines and training about occupational health practices was generally not effective enough to influence and change their behaviour with injured workers. Some participants mentioned that HCPs have many competing educational and training requirements as part of their regular practice and that occupational health aspects are often not a priority for them. This was mentioned for physicians as the next quote illustrates, but it was also said for other HCPs such as chiropractors, physiotherapists and osteopaths.

“In terms of GPs, I know that GPs are notoriously difficult to upskill in this space. And that they’re time poor, in terms of … they’re very busy; they’ve got a lot of demands, and their knowledge base is really quite broad […] so I can understand why it’s actually difficult to, I guess, get some penetration with that training.” Victoria3—Researcher.

A participant from the employers’ group complained that the most recent evidence on occupational injuries was not incorporated in the work of HCPs, and that new ways to bring the evidence closer to HCPs’ practice should be envisioned.

Monetary Incentives to Change Healthcare Providers’ Behaviours

Linked to the lack of engagement in training and the difficult uptake of clinical guidelines by HCPs, some participants discussed the use of financial incentives by the WCB to modify targeted HCPs’ clinical and administrative behaviours. These monetary incentives were mainly used to incentivize the implementation of WBC’s policy goals regarding treatment provision. More specifically, they were: incentives to train, incentives for rapid healthcare uptake and rapid return to work and incentives to have HCPs treat injured workers within the system. Each of these elements are described below.

Incentives to Train

In Victoria, the WCB created a special reimbursement fee for physiotherapists who completed a standard training module on injured workers’ care. Only physiotherapists who successfully completed the module could be paid a higher reimbursement fee by the WCB.

“We have a structure where there are physiotherapists who can do extra training, and can then, effectively, call themselves occupational physiotherapists, and they have a different fee structure when they’re treating worker’s compensation and traffic accident clients, and we put together an online training package, the idea being that physiotherapists would have to complete the training to qualify for that title and be able to bill for, slightly more for their services when treating compensable clients.” Victoria3—Researcher.

A participant affiliated with the Department of Labor and Industries in Washington also spoke about developing a certification with higher pay for the HCPs who completed it. He provided the example of Colorado that has a workers’ compensation 101 certification system in place as a potential model.

Incentives for Rapid Healthcare Uptake and Rapid Return to Work

One participant described how the Washington Department of Labor and Industries began using monetary incentives to encourage HCPs to meet specific indicators. Interestingly, after originally wanting to incentivize clinical practice indicators (i.e., elements that are directly related to clinical best-practices, such as the need to do a nerve conduction test before envisioning a carpal tunnel surgery, or providing prophylactic antibiotics to a patient if they have a compound fracture), the Washington WCB created a payment structure to incentivize four specific administrative occupational health indicators that aim to facilitate rapid uptake of the claim and return to work. These are: (1) filling and sending the initial claim form within two days of the injured worker’s visit to the physician, (2) determining at the first and second visits, for workers on lost time, what they can and can’t do at work using an activity prescription form, (3) having somebody from the physician’s office communicate with the employer about return-to-work options, and (4) determining the barriers to return to work if the worker is still not working at four weeks after injury. A participant affiliated with the WCB in Washington mentioned that the three first indicators had been fairly straightforward to implement and had demonstrated good uptake and results, while the fourth one was more complex and needed operationalization.

In Ontario, a participant from an injured workers’ support group mentioned that a recent Workplace Safety and Insurance Board (WSIB) policy prompts a decrease in the reimbursement fees for HCPs when their patient has not returned to work after a certain point in time in certain programs of care (e.g., low back pain). According to this participant, these decreasing monetary incentives could lead to potentially unsafe practices by professionals as they could try to push the workers back to work faster to avoid decreasing fees.

“[…] but, for example, in these programs for treatment of musculoskeletal injuries, they will impose sliding scale fee structures that pay less as the treatment takes longer. They say that is paying for results, meaning they’re paying less if physicians are not being successful or physiotherapists or chiropractors are not being, quote/unquote, “successful” in getting workers out of treatment and back to work. We say they’re … disincentivizing longer term treatment because a physician or a physiotherapist who needs to recommend more treatment is going to face the reduction of the fee structure […]. Really, we’re not a fan of that in the worker community ‘cause we worry about physicians being incentivized in bad ways to rush things—to rush treatment; to rush report’”. Ontario1—Workers’ group.

Incentives for Healthcare Providers to Treat Injured Workers

In Victoria, two participants from two workers’ support groups also discussed the problem of physicians refusing to see injured workers compensated by the WCB. They proposed that monetary incentives could be used to incentivize physicians to care for injured workers.

“P2: Maybe they should be rewarded when they take on Work Cover recipients, and given ?-

P1: Dangle a carrot.

P2: You know, incentives to take them on. Be more patient with them, knowing that these injured workers are gonna require more time of theirs. Maybe that might be the answer because, financially, we all know that’s what will do the thing. They’ll do the number crunching, and they’ll say ‘Oh, that’s financially viable; that’s a good idea; we should take on more.” Victoria8a and Victoria8b—Workers’ groups.

Financial incentives were also used to negotiate with groups of HCPs that originally did not want to care for injured workers. For example, a group of orthopedic surgeons was requesting higher reimbursement fees for their surgeries performed on injured workers. The Department of Labor and Industries agreed to increase their fees if these surgeons would abide by some ‘quality’ indicators:

“[…] and we developed some quality indicators for surgery and we agreed to pay them the amount they were asking for, but not more for the surgery, only if they did these quality indicators. So, one of the quality indicators was to use generic drugs instead of brand-name drugs […] So, having these incentives for the physicians, they didn’t care… whether they were writing a prescription for a generic or a brand-name drug, so it was like almost 100% in that pilot that wrote for generic drugs, so that’s just a small example with a sort of big impact of a quality indicator as part of a quality improvement program with incentives for orthopedic surgeons.” Washington5—WCB’s group.

This initiative with one group of surgeons led to the Orthopedic and Neurological Surgeon Quality Project that expanded statewide and provided higher fees to surgeons who abided by six ‘quality best practices’: (1) Complete activity prescription form before and after surgery; (2) Document and track rehabilitation plans and goals; (3) Only write ‘dispense as written’ prescriptions when formulary alternatives are unavailable or clinically inappropriate; (4) Offer injured workers timely access to care; (5) Offer injured workers timely surgery; (6) Maintain and report continuing education units [31]. Interestingly, many of these indicators enforced by the compensation system in Washington in exchange for surgeons treating injured workers at a higher reimbursement rate also represented important cost-saving mechanisms for the WCB.

In Quebec and Ontario, some participants from the workers, researchers and healthcare providers’ groups also discussed the tendency for HCPs to be reluctant to treat injured workers, mainly because of administrative hurdles and frustrations with the workers’ compensation system. In Ontario, a workers’ representative clearly illustrated this, however, in that province, no specific incentive was mentioned to induce HCPs to take on injured workers as patients.

“The system does not pay much attention to what the primary physician says, and the physician is more and more frustrated with the WSIB bureaucracy and filling out forms, and, often, physicians say, ‘If it’s a compensation case, I don’t want it. I don’t want to deal with it’ because they see themselves as dealing with complicated case situations in a frustrating bureaucracy, but the person that loses in the end is the injured worker who says, ‘Where do I go?’.” Ontario4—Workers’ group.

In Quebec, one physician participant working for employers mentioned that physicians are adequately paid to fill in forms from the Commission des normes, de l’équité et de la santé et de la sécurité du travail (CNESST), the WCB in Quebec, and that that is appreciated. However, he said that if the WCB wanted to implement specific practices or indicators, physicians’ practices could easily be changed by adding reimbursement codes that would financially reward them for specific behaviours:

“You know, there is nothing easier to change the practice of physicians than to add a billing code used by Medicare (the universal public health insurance system that exists in Quebec and in Canada). If money was payable if the physician spoke with the employer for the return to work, $60 per 15 min, my God, we would talk to employers. It would be easy to encourage this kind of behaviour by making changes in the billing system.” Québec9 – Employers’ group.

Controlling Workers’ Trajectories of Care

Data analysis clarified that WCBs not only used incentives to modify HCPs’ practices in their work with injured workers, but also used other mechanisms to control the overall workers’ trajectories of care in the compensation system. Depending on the participant’s social location (e.g., participants representing workers or the WCB), the discourse was different and sometimes opposed. Across jurisdictions, two aspects were more lengthily discussed: (1) the practice of standardizing, organizing and predefining care pathways for injured workers and (2) the ways and extent to which WCBs’ laws and policies confer powers to HCPs to oversee and shepherd injured workers’ care trajectories.

Standardizing and Predefining Care Pathways

When discussing workers’ healthcare and rehabilitation trajectories, a researcher participant from Washington discussed the importance of standardizing some aspects of the care pathway for injured workers as this could help prevent longer episodes of disability by detecting risk factors of chronicity, help limit unnecessary medical and/or rehabilitation interventions and could help better tailor the interventions to the pre-identified patients’ phenotype or group. According to one participant, this standardization could be done using validated stratifying tools to better predict and guide the trajectory of the workers, based on some of their individual characteristics. For example, many researchers interviewed for this study spoke about the need to rapidly eliminate red flag conditions, avoid the use of opioids and unnecessary imaging, and determine broad pathways for care (e.g., conservative care without consultation for surgery).

“An injured worker with low back pain and after the initial screening, […] I think, taking note of that group, especially if they’re sort of a low risk group, and then just saying that, you know, if there’s no concern about serious injury, that they’re not getting an x-ray; they’re not getting opioids, um, and they’re going to—you know, you could have treatment A, B or C, or they can go to physio; they can go to something else or depending on what is appropriate or they want, but sort of having that kind of standardization, rather than be like, ‘Well, maybe we’ll get an x-ray in this case’, or ‘Maybe we’ll prescribe the opioids ‘cause you’re really asking for them’, you know, so I guess that’s what I’m … talking about when I’m talking about standardized pathways, and that’s just one example.” Washington1—Researcher.

The need for WCBs and HCPs to foresee potential chronicization of the worker’s condition was discussed by many participants. According to a participant from Washington, the WCB was in the process of using a screening tool called the Functional Recovery Questionnaire [32] to detect chronicity factors at the opening of the claim. This participant mentioned that this tool had been developed based on well-known musculoskeletal triage tools based on scientific work and used in HCPs’ practice. The use of this ‘chronicity detection tool’ had been validated with a large sample of workers in the state. The goal with this tool is to detect chronicity factors at the start of the claim so that the WCB can rapidly adjust the type of services offered to workers (e.g. psychological consultation earlier than what would have been proposed without the use of the detection tool).

In Quebec, a researcher participant mentioned that such a detection tool was currently used by the Quebec WCB to detect chronicity factors at the beginning of the claim. However, to their knowledge, the scientific bases and processes for its development were unknown. A Quebec participant expressed concern regarding this tool, mentioning that it had not been well validated and had not been the object of a formal evaluation, which could, in his view, impede its potential to positively impact workers’ care trajectories and affect the acceptability of the tool by the HCPs.

Apart from early chronicity detection tools, many participants in the researchers’ group were in favor of better structuring the care pathway for workers compensated for a work injury. A researcher participant from Quebec mentioned that more verifications should be done at predetermined points in time after the onset of the claim to evaluate the rehabilitation progress of a worker. Known risk factors should be identified and different actions taken to prevent chronicity.

When discussing the need to improve the trajectory of care for injured workers, several participants’ views aligned with the need to prevent harmful consequences of not having foreseen potential barriers to recovery in the first weeks following the compensation claim. Another researcher participant clearly expressed that the first weeks after an injury were crucial and that, instead of relying on a ‘disability management approach’, workers’ compensation systems should rely on a ‘disability prevention approach’.

In Washington and Victoria, HCPs and other participants specifically spoke about the need to prevent surgeries happening rapidly when conservative care has not been tried with the worker. In these two jurisdictions, it is possible for injured workers to consult a surgeon directly as a first-line provider. This is not possible in Ontario and Quebec, where family medicine or general practitioners will generally be the first point of contact. In the cases described above, according to participants in favor of this surgery-prevention approach, better defining the care pathways for injured workers entering the workers’ compensation system should be done to prevent harmful consequences such as prescribing too many diagnostic tests when it is not judged necessary or performing a surgery early when this might not lead to better outcomes for the worker. One major example of control exerted on the workers’ plan and trajectory of care concerns the prescription of opioids by treating physicians of injured workers. A workers’ representative from Washington spoke very positively of the measures imposed by the Department of Labor and Industries some years ago to control opioids prescriptions. This WCB policy says that a physician can’t prescribe more than three days of opioids at the initial visit of the injured worker.

“Labor and Industries have the policy now where they will not pay for more than three days’ worth of opioids at an initial visit, so workers are not walking away with a giant bottle of oxycotin after a slip, trip or fall, a breaking of a leg or whatever. They’ll get three days with opioids, and then they have to go back and kind of reassess with their medical professional, and L&I keeps a pretty tight track of what they’re paying for when it comes to opioids as a pain management strategy. Some of my affiliated unions […] they have some heart burn about this policy. I mean, what they see is their members in pain, but I think everybody is kind of recognizing that worker’s compensation access to opioids is sort of a gateway to a larger opioid addiction and you know, they’re seeing people, more struggling with their opioid addiction, now, than they are with their pain management, and so I think we’ve come a long way, as the labor movement, in recognizing—and we were opposed to the opioid management program, early on, ‘cause we wanted our members to get the pain medication that they needed, but the metrics that the department has been tracking have demonstrated, pretty clearly, that very, very few workers now die from opioid overdoses as a result of their injury.” Washington4—Workers’ group.

However, according to some participants, restrictions placed on healthcare usage do not only have positive consequences. A nurse participant from Washington mentioned that, at times, the necessary medications prescribed to injured workers were not automatically reimbursed by WCB. Some participants felt that these forms of interference in the plan of care, driven by standardization and harm reduction protocols, were deleterious for workers.

Autonomy and Power Vested in Healthcare Providers

Many discussions with participants led to conversing about the autonomy and power that HCPs caring for injured workers really have in determining their care and support through their recovery and rehabilitation trajectories. Most participants affiliated with employers in the four jurisdictions mentioned that they would like WCB policies to be more stringent about the number of treatments that can be provided by HCPs. For example, employers’ representatives situated in Quebec and Victoria more often mentioned the need to restrict allied health treatments (such as physiotherapy) and to provide stronger policy orientations to HCPs to restrict frequency of treatments and duration of care. Workers’ representatives and HCPs on the other end, mentioned the importance for HCPs to have the necessary autonomy and leeway to pursue the treatment modalities and trajectory that they believe are the most appropriate for each worker, without restrictions imposed by the WCB.

Depending on the jurisdiction, HCPs’ opinions and recommendations could be largely ignored by the WCB, or, in contrast, be followed as prescribed by the law. For example, Ontario participants from workers’ support groups mentioned that the clinical opinions of the treating physicians are routinely set aside by the WCB. One participant suggested that physicians and HCPs in Ontario have practically no control over workers’ care. What HCPs propose and prescribe are only considered as suggestions by the WSIB, who are not required to follow, address or fund any of their recommended services.

“Well, the policy, on the surface, says that it takes into account what primary care providers say to the board. However, in practice, their role is minimal. They’re really not listened to, other than for the initial reporting—the form 8. What they say after that, is mostly irrelevant to the system.” Ontario4—Workers’ group.

Ontario was not the only jurisdiction where the healthcare trajectory was presented as strongly influenced by the WCB. A participant from Washington also mentioned that the claim managers had the power to close claims and alter the workers’ care trajectory and that with such power came the need for sensitivity.

“You know, the claim manager really calls a lot of the shots, so they’re in a very important, powerful position and I was thinking that they really do need to have sensitivity training because they’ll close claims; they’ll refer for these independent examinations […].” Washington6—HCPs’ group.

The fact the HCPs could not always directly pursue important clinical interventions for their patients because of the necessity for the WCB to approve diagnostic imaging or medications, for example, was perceived very negatively by a clinician participant who said that the lack of decisional autonomy further increased delays for appropriate care for workers.

“For example, if I want to get an MRI of whatever body part, it will probably take two weeks to go through the approval process and they will frequently do things like say, ‘Oh, you have to get an x-ray first’, right? If I’m concerned about a rotator cuff tear, I’m pretty sure that getting an x-ray will show me nothing useful, increases cost, and have my patient radiated when they don’t need to be. So, they have some rules in place that are… out of date, that I believe are designed simply to act as roadblocks so that we do not have an easy way to get something approved, […] If it’s inexpensive, it’ll get approved quicker; if it’s more expensive, then the more expensive it is, the longer they’re going to delay even considering it.” Washington2—HCPs’ group.

A similar concern was raised in Victoria where HCPs have to get approval from WorkSafe Victoria for testing and interventions prescribed. A participant from the researchers’ group said that the WCB should trust the expertise and respect the autonomy of the HCPs and this would lead to better care for workers.

“Well, I think it’s just more about the ability to be able to say a particular service is needed and not necessarily have to go through an administrative process to have that approved. So, I guess it’s an acknowledgement of the expertise […] So, it’s acknowledging the skill set of that person, to identify what services are needed and relying on that to be the approval process, if you like, and not necessarily having to go through too many hoops.” Victoria3—Researcher.

In Quebec, those concerns were not voiced by participants. Participants from workers’ representation groups and healthcare professionals from Quebec mentioned that the historic addition of an article in the revision of the compensation law in 1985 made the opinion of the medical physician binding for the WCB on five distinct elements of the workers’ care (i.e., diagnosis, treatment, date of maximum medical recovery, functional limitations, and permanent impairment) [33, 34]. This legal provision was perceived as key in preventing WCB interference in medical and clinical matters, and for ensuring that the power to prescribe appropriate medications and healthcare interventions for the workers stayed vested in the physicians’ hands. In Quebec, participants from injured workers’ groups and physicians clearly saw this rule as the cornerstone of an independent medical practice in the compensation system.

On the other hand, Quebec employers’ representatives mentioned that this rule often led to “complacency”, supporting physicians to allow rehabilitation treatments go on for periods of time judged as being excessive. These participants were in favor of a system where the WCB is given more power to make decisions regarding the workers’ care trajectory. According to some participants affiliated with employers’ groups, injured workers’ benefits and healthcare treatments should be revised more rapidly after the onset of compensation and healthcare treatment to prevent abuse in healthcare usage. One participant went further and said that healthcare treatments should be revised and managed on a basis of average healing times, even if the person’s disability is not completely resolved. Stricter restrictions on care decisions were mostly discussed by participants affiliated with employers. These participants often made comparisons with private insurance schemes that implement more stringent controls on care for the people insured.

“But I imagine that even within Canada, I find it hard to believe that we wouldn’t be able to come up with a single table for the duration of consolidation for injuries. Once you have a list like that, well, it's easy to have technicians because the compensation officers at the WCB are technicians. They are not professionals, they apply policies that are written in black and white. So, it would be easy to provide them with very clear policies where "well, in your file, from the moment you are at six weeks of compensation, and off from work for a lumbar sprain—it's time to go for medical expertise"”. Québec11—Employers’ group.

An Ontarian participant affiliated with a workers’ support group did not agree with defining care pathways according to fixed standards established by the WCB. In their view, such pathways were mainly based on the views and decisions from stakeholders from the WCB who aim to manage claims more rapidly to be able to close the file. In that regard, this participant stated:

“WSIB used to have an approach that was a lot more based on what the family doctor thought was the right treatment. Like, it was much more individualized. It was much less standardized, so there was a lot more flexibility for individual—for the reality that individuals heal differently, that they come into injuries with different bodies and stressors, and that they will come out of them differently as well, and a drive towards rigor and standardization and discipline so that claims can be managed more aggressively and successfully and closed, which, generally, is bad. Of course, there is sometimes, like an advantage, I suppose in a system that’s more rigorous because it’s faster or more efficient, but generally, it’s a worse—certainly for our workers who, if they don’t—generally, we see people who don’t recover as expected, right […]we’re not seeing all the people with uncomplicated claims okay, but for people who don’t recover—which is the people we see—this system lacks an ability to comprehend the individual experience they’re having.” Ontario1—Workers’ group.

In two jurisdictions with a fee-for-service reimbursement model for rehabilitation care (Victoria and Washington) some participants mentioned that WCBs perform utilization reviews and audit professionals’ reports to oversee HCPs’ practice and to retain some control over the trajectory of care. These reviews are usually undertaken by a clinical panel consisted of people from different healthcare disciplines, which reviews files and poses a judgment on the ‘appropriateness’ of the care provided to a worker. These reviews can be made after a fixed number of healthcare treatments (e.g. 12–20 visits) or more specifically target workers who have prolonged healthcare utilization. These reviews are mainly based on reviewing paper or digitalized files and not by examining patients directly. Some healthcare professionals’ participants perceived these reviews as fundamental for avoiding abuse in the system or prolonged care that would not be justified. Some employers’ representatives wished that such auditing could be done more often and more stringently to avoid unnecessary treatments. However, participants from the workers’ group stressed that these clinical reviews should be undertaken with caution as decisions are mainly taken based on paper files and not based on a thorough understanding of the worker’s condition based on a direct examination.

In Quebec and Victoria, participants also discussed the re-evaluation of workers by a third-party medical physician as a common mechanism used by WCBs and employers to set aside the opinion of the HCPs and to modify workers’ care trajectories. In Quebec, some participants explained that these second opinions aim to put pressure on the treating physician so that they change their opinion and the care trajectory. In Victoria, these medical evaluations are often used by the WCB to support the WCB in disputations on ceasing healthcare treatment services. A researcher participant from Washington also mentioned the use of ‘independent’ medical examinations. In these three jurisdictions, participants from the workers’ and researchers’ groups shared the perception that these medical examiners were not ‘independent’ as they are usually paid for and their services are requested by employers and/or the WCB.

“[…] but at any given point during the life of the claim, if an insurance company physician examines an injured worker and then changes their opinion to what’s on the certificate, then they will push the GP’s opinion to the side, and they will always go with what their own physician says is now the current situation that it’s—an example might be it’s no longer work related, and the injury has resolved. So, once they’ve got a physician on their side, saying that they will disregard what the GP says, even though the GP is the one seeing them every month, on a regular basis, and the insurance company physician may have only seen this injured worker once in ten months, and often that medical examination might be a 15-min examination to base their opinion. So that is the crux of what our WorkCover system is based on.” Victoria8—Workers’ group.

“What ends up happening sometimes, then, at least in Washington, is the insurance company sends them to people called independent medical examiners. Basically, it’s someone who is like hired by the insurance company to give them opinions that may be related to causation, may be related to treatment. And what’s complicated about that, from my opinion—again, it’s my opinion here—is that an independent medical examiner, you know, they’re supposed to be completely objective; supposed to provide the information to the insurance company. But there’s just sort of things that undermine their objectivity, you know, whether or not it’s continued relationships with the insurance company; whether or not it’s other incentives to limit care. Who knows exactly what’s going on, but they don’t have that sort of obligation to form a patient and physician relationship that, you know, is to yield the best outcome for the individual worker.” Washington3—Researchers’ group.

In Ontario where the trajectory of care is more strictly defined, workers who do not improve according to WCB standards are sent to specialty clinics designated and funded by the WCB to be evaluated by an interdisciplinary team. In those cases, some interview participants mentioned that the treating HCPs might not be informed of their patient transitioning to such facility and often don’t stay involved in the care of the worker following this transition because of a lack of communication. Some workers’ participants from Ontario said that these clinics “marginalize” (Ontario4-worker’s group) the treating physician as they are pushed out of the workers’ case and the ongoing relationship is only established between the specialty clinic and the WCB. However, some participants from the workers’ group said that these clinics could provide quality care and help the worker progress more in their recovery.

Discussion

This four-jurisdiction key informant policy analysis study shed light on the different ways in which workers’ compensation system policies actually frame the work of HCPs in their practice with injured workers. This study helps demonstrate and illustrate, using situated informants’ inputs and concrete examples across systems, the many incentives that are embedded in compensation policies to frame these practices. Key informant interviews also provided a better picture of how healthcare policies concretely shape workers’ care trajectories in these systems. This study adds to the current scientific literature that aims to better understand the effects of workers’ compensation policies on workers’ care and trajectories [35, 36].

This study reinforces the fact that HCPs offering care to injured workers are incentivized, either overtly or more subtly, to practice and provide care in certain ways. With regard to economic and non-economic inducements embedded in WC policies, the need to adhere to specific clinical practice guidelines and training sessions on occupational health were generally perceived positively by informants interviewed from the employers, researchers, HCPs and WBCs’ groups. However, according to most participants, these educational policies did not seem to create concrete changes to HCPs’ practices as many elements could limit their uptake. This is interesting as a recent publication in the WC domain showed that the implementation of guidelines and educational measures are perceived by HCPs as having many limitations and need to be used with caution [37]. In their cross-sectional mixed-method design, Elbers and colleagues quantitatively investigated HCPs’ (psychologists; physicians in general practice, pain, musculoskeletal and occupational health; physiotherapy; chiropractors; rheumatologists; surgeons) attitudes toward evidence-based medicine and also qualitatively explored HCP’s perceptions of the implementation of an evidence-based medicine tool that would orient healthcare treatment in the workers’ compensation field [37]. The results of the qualitative methodology part of the project demonstrated that HCPs were worried that the use of an evidence-based medicine tool in their practice would not allow them to exercise their clinical judgment [37]. Some HCPs in Elbers’ study were also unsure about the capacity of such an evidence-based tool to take into account psychosocial and environmental factors along with individual differences, which are key predictors of patients’ outcome, a concern that was also raised in our study. Some HCPs in Elbers’ study also saw the potential for such a tool to limit inappropriate interventions (e.g. magnetic resonance imagery) and mentioned that it might help with discussing the patient’s expectations towards progression and return to work; however, most raised important concerns about the use of such tool [37]. In order to improve policy changes, this study concluded that the use of clinical practice guidelines based on evidence-based medicine should take into account the clinicians’ clinical judgment, should be flexible in its use and be adapted to patients’ individual differences and psychosocial and environmental contexts. Interestingly, the authors also discuss the need to improve communication and trust between HCPs and workers’ compensation claim managers before trying to implement any such tool, due to elevated concerns of potential misuse of the tool among the healthcare participants.

Economic incentives to return injured workers rapidly to work were also highlighted in this study. Such economic incentives were criticized as they can lead to unsafe or hastened return to work [38,39,40,41]. For example, a critical review of studies investigating the effect of experience-rating in workers’ compensation systems demonstrated perverse effects on claim management techniques and on healthcare providers’ behaviours, such as sending workers back to work when no modified work is available [40]. Premature return to work and lack of consideration for the injured workers’ condition was said to lead to workers’ re-injury and/or feelings of distress because of high pressure and dissatisfaction from co-workers [42]. In our study, some participants from the workers and HCPs’ groups mentioned the importance of establishing safe conditions for the workers to return to work. More specifically, decreasing fee scales for HCPs returning workers later than a preselected set number of weeks in Ontario was seen as creating an incentive to push workers back to work too quickly and as potentially leading to adverse health consequences.

Economic incentives to have HCPs abide by administrative processes in Washington were also discussed, such as incentives that attempt to prompt HCPs to send in the medical claim report rapidly after the first encounter with the injured worker. As recently shown by robust studies in the compensation field, policies that incorporate such incentives could have positive consequences for workers if they, for example, help decrease the delays before initiating the claim and receiving healthcare services [43]. Indeed, longer delays in processing claims for injured workers have been associated with prolonged disability duration and development of chronicity [44, 45]. However, such incentives could prompt HCPs to provide brief and incomplete reports [9, 46].

Although HCPs aim to offer individualized care for their patients, several mechanisms stemming from compensation policies constrain their professional autonomy and decisional power. In Ontario, Washington and Victoria, the HCPs provide their medical and rehabilitation opinions on what is judged necessary for the workers, but the compensation board retains most of the power to adjudicate or enact these treatments. Indeed, it has been shown that WCBs tend to discount the treating HCP’s opinions with the assumption that they are lenient on their patients [6, 47]. This can be deleterious for workers as decisions relating to healthcare matters are then vested in the hands of persons or entities, such as claims adjudicators, who do not necessarily have medical or rehabilitation expertise or that base their decisions solely on pre-established recovery guidelines [47, 48]. This can, in turn lead to unnecessary delays for workers in receiving important medical interventions, because of wait for approval or denial of services. The lack of power and autonomy of HCPs could potentially lead to increased stress and negative perceptions from the workers. This is important as negative experiences of care by the workers have been shown to be associated with workers health and self-reported work status [49]. These elements have also been shown to be associated with prolonged disability [50]. Lack of professional autonomy can also lead to significant ethical struggles for professionals who cannot do what they consider best for their patients [8, 18, 51,52,53]. Also, this lack of autonomy can lead HCPs to avoid taking on injured workers as patients [9, 46].

Different ways in which healthcare trajectories for injured workers are currently or could be reorganized were discussed by key informants. This reorganization, via novel workers’ compensation policies, was mainly discussed in the aim for compensation systems to become more responsive to well-established predictors of chronicity early in the workers’ care pathway. Perspectives diverged on the most appropriate ways to do so, but it seemed important in designing such policies to find a delicate balance between standardizing some aspects of care that could benefit the worker, for example, favoring conservative care before more invasive procedures such as surgeries [24] or refraining from performing imagery tests early [54], while maintaining individualized care [47]. Indeed, previous work has highlighted how WCBs’ policies sometimes played a leading role in saving patients from unnecessary or harmful surgical procedures [47]. Evaluating the implementation of such standardization policies on workers’ outcomes, as occurred with the policy restricting opioid prescriptions in Washington for injured workers [55] and incorporating the main groups of stakeholders in this endeavor (e.g. workers’ and employers’ groups, healthcare providers, WCB representatives and researchers), could lead to transparent and constructive discussions and decisions on such new policy initiatives.

By analyzing the perspectives of different actors in four jurisdictions, similarities and differences were noted between systems. One important point to highlight is that many of the healthcare policies in place during the study and discussed by the key informants had emerged from changes to workers’ compensation systems in these jurisdictions in the past 10–20 years. According to several participants in this project, these changes and reforms mainly aimed to reduce WCBs’ expenses and ensure economic performance of the workers’ compensation system. This trend has been shown to exist in the United States where workers’ compensation systems have made several policy changes to reduce their costs in the last two decades [48]. A historical and contextualized perspective on policy development is important in situating the incentives and mechanisms currently framing healthcare practices in workers’ compensation systems. Several key informants had long years of experience studying, exploring or dealing with the compensation systems in their own jurisdiction. In our study, we witnessed that some workers’ compensation systems had developed, and formalized policies, based on thorough evaluation of the outcomes and had largely shared these outcomes publicly, while other systems seemed to have made policy decisions without transparent or concrete feedback on workers’ outcomes or perceptions. This is interesting since the four compensation systems studied are para-governmental organisms that should be accountable to workers, employers, healthcare professionals and the public in terms of policy decisions and their impacts. Previous work has suggested that, since WC operate with a “captive clientele”, i.e., the workers under compensation, they pay less attention to patients’ satisfaction and their perception of quality of care [47]. Recent examinations of the workers’ compensation system decision-making process in Victoria demonstrated serious problems in the administration of the workers’ files and brought to light the deleterious impacts of decisions and actions from the WCB [56, 57]. Investigation of the workers’ compensation system by an ombudsman is another important way in which the voice of injured workers can be heard and through which policy changes could be supported. For example, the ombudsman’s recommendations in Victoria following the official report led to concrete policy changes at the state level, since changes required at the WCB level had not led to concrete improvement in the management of complex claims [56].

In his seminal work on WC structures, Terrence Ison concluded his paper by stating that the therapeutic significance of WC structures on workers’ care and trajectories were sufficiently important to be taken in consideration in any system redesign. He said that “This consideration is most likely to occur when a system is revised through careful contemplation by people who can see the impact of the options on the system as a whole, and on interaction with other systems. It is least likely to occur when a system is revised by ad hoc responses to lobbying pressures, guided primarily by the political pragmatism of the moment” [47]. (p. 636) With regard to workers’ compensation policy reform across jurisdictions, it seems crucial for policymakers to be able to clearly understand the distinction between the ‘impact’ policies have on people and society from the ‘outcomes’ that are compiled and measured by the WCBs. All WCBs ultimately report outcomes and these outcomes most often serve as the basis for reforming systems. However, these outcomes should not be positioned as the basis for informing and transforming policies. Instead, policymakers should aim to gather a thorough understanding of the broader impacts that the current policies do have on the workers and on society more broadly. This is what our exploration and comparison of current workers’ compensation policies with regard to healthcare aimed to do. This study brings to light important impacts of current WCB policies on healthcare providers’ work and on workers’ trajectories in four jurisdictions. These findings also help reflect on the ingrained values underpinning workers’ compensation policies that should be made more transparent and be more largely discussed in the public space and the scientific literature to support further policy changes.

Strengths and Limits

Although this project aimed to present an in-depth and situated portrait of the influence of WCBs’ healthcare policies on HCPs and workers, it mainly relied on the experiences and views of the participants interviewed. As such, it is possible that some important aspects of these policies and systems were not discussed by the participants. To mitigate this limitation, increase the rigor of the project, and allow for interesting comparisons, we included differently positioned participants with a diversity of experiences on the subject in each jurisdiction. We also consulted and used compensation laws in each of the selected jurisdiction to supplement the data and our understanding of the policy context. Further, we consulted the websites of the four workers’ compensation boards. However, we did not conduct a formal legal analysis in the four jurisdictions studied. When analyzing and reporting the results, as much as possible, we preserved and presented the different views in a nuanced way. Considering that we used qualitative data in this policy analysis, we decided to depict a rich variety of concrete examples to illustrate the varied ways in which policies affect HCP’s work and workers’ trajectories. These examples facilitate contextualization of care offered to injured workers in each of the four systems. However, we did not collect quantitative empirical data on HCPs’ practices nor on injured workers care to supplement the qualitative findings.

Conclusion

The complexity of workers’ compensation systems and their disparity across jurisdictions make empirical comparisons difficult. This policy analysis with key informants from Ontario, Québec, Victoria, and Washington shed light on the different ways in which workers’ compensation policies frame HCPs’ day-to-day practices and how these policies can shape workers’ care trajectories. This project demonstrated that HCPs are incentivized, either overtly or more subtly, to practice and provide care in certain ways. WCBs in these four jurisdictions use different mechanisms such as non-econonomic (clinical guidelines and training to HCPs) and economic inducements (higher reimbursement rates), and strategies of standardization (preventing the use of certain tests or interventions and predefining care pathways) to influence workers’ trajectories. An important finding from this study is that future changes in workers’ compensation policies should not only rely on available outcomes collected and compiled by the WCBs but should also be informed by thorough investigation of the concrete impacts these policies have on providers, workers and on society more globally. Our study also demonstrated that, even across three different countries, similar policy mechanisms have similar impacts on HCPs and workers. Future research in the field should thus focus on exploring and determining which specific ‘policy types’ or ‘policy mechanisms’ have the most positive impact on workers’ care trajectories. This type of research could then lead to significant changes in designing future workers’ compensation laws and policies based on what really has been shown to have a positive impact. Because of this change in focus, the thorough understanding of policies leading to better process in the system and better impact for workers could stimulate reflections across countries with similar compensation systems. A better understanding and a nuanced portrait of these policies’ impacts on HCPs and workers could thus concretely help support future policy changes and inform the revision of workers’ compensation policies in other jurisdictions.

Data Availability

To preserve the participants’ anonymity, we do not and will not make the data available. Readers of the papers that might have questions about data can contact the corresponding author (anne.hudon@umontreal.ca).

Code Availability