Abstract

Purpose Health care providers (HCPs) play an important role in return to work (RTW) and in the workers’ compensation system. However, HCPs may feel unsure about their responsibilities in the RTW process and experience difficulty making recommendations about RTW readiness and limitations. This study examines the ways in which HCPs and case managers (CMs) perceive HCPs role in the RTW process, and how similarities and differences between these views, in turn, inform expectations of HCPs. Methods In-depth interviews were conducted with 69 HCPs and 34 CMs from 4 provinces. Data were double coded and a thematic, inductive analysis was carried out to develop key themes. Findings The main role of HCPs was to diagnose injury and provide patients with appropriate treatment. In addition, the majority of HCPs and CMs viewed providing medical information to workers’ compensation board (WCB) and the general encouragement of RTW as important roles played by HCPs. There was less clarity, and at times disagreement, about the scope of HCPs’ role in providing medical information to WCB and encouraging RTW, such as the type of information they should provide and the timelines for RTW. Conclusion Interviews suggest that different role expectations may stem from differing perspectives of HCPs and the CMs had regarding RTW. A comprehensive discussion between WCB decision-makers and HCPs is needed, with an end goal of reaching consensus regarding roles and responsibilities in the RTW process. The findings highlight the importance of establishing clearer role expectations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Health care providers (HCPs) play an important role in the return to work (RTW) process and in the workers’ compensation (WC) system [1,2,3]. In addition to diagnosis and treatment of injury and illness, HCPs provide important information to case managers (CMs) in the workers’ compensation board (WCB) about the work-relatedness of the injury and workers’ “fitness” for employment. They are expected to complete a health professional’s report and a functional abilities form based on workers’ capabilities. They are also responsible for recommending a RTW timeline [4]. Because of their close involvement in the process, HCPs are perceived by patients as trusted advisors [5] and can thus influence patients’ views around recovery and RTW. Research suggests that a positive HCP-patient relationship can help decrease a patient’s depression and anxiety [6], and proactive HCP communication can facilitate the patient RTW process [3, 7, 8]. For example, in a study that examined HCP communication with the patient and workplace post injury, Kosny et al. found that if a patient was given guidance on how to prevent recurrence and re-injury, they were more than twice as likely to RTW [8].

Research suggests, however, HCPs generally receive little training in medical school as it pertains to occupational health and WC [9, 10], and may have difficulty assessing functional abilities [11] and making recommendations about RTW readiness and limitations [12,13,14,15]. In addition, given their heavy workload and limited consultation time, HCPs can find assessments and making RTW recommendation difficult and time consuming [6, 8, 12]. Complicated and prolonged claims may be especially challenging for HCPs, including claims for complex conditions such as multiple injuries, chronic pain, or mental health issues [12, 16].

Although guidelines and policies have been developed for HCPs by WCBs, governments, and other professional organizations, these resources do not always provide adequate information about the HCP role in RTW and the WC system [17]. In an analysis of available Canadian resources, Kosny et al. found that materials in many jurisdictions did not sufficiently describe the mechanisms of HCP involvement in the RTW process [17]. Information was often confusing and conflicting—even within the same jurisdiction. For example, there was uncertainty around whether an HCP should determine work readiness, assess suitability of available jobs, or simply assess function and provide treatment [17]. The lack of formal training, coupled with insufficient information availability, can result in uncertainty around HCPs role in the RTW process [9, 12]. This role ambiguity has real-life consequences, as it may impact the ability of HCPs in helping injured workers (IWs) RTW, which can complicate and extend claims and result in hardship for IWs [12, 16].

The first aim of the study was to examine how HCPs perceive their role in the RTW process, and how their perception impacts the extent and nature of their involvement. Role theory suggests that, perceptions regarding the tasks individuals are responsible for influence their behaviour and level of engagement [18, 19]. These individual perceptions are especially important in situations where roles are not formally defined, as in the case with HCPs in RTW process. While the challenges of HCPs interacting with WC systems are well documented [12,13,14, 20] only a handful of studies have focused on how HCPs view their own role in the RTW and WC system [1, 12, 16]. Understanding how HCPs perceive their role can provide insights into the activities they expect to carry out and the overall responsibilities they assume. For example, some HCPs may see their role as being limited to providing treatment to IWs, and thus may have little engagement in the RTW process. Still other HCPs may perceive their roles to be more comprehensive, thus resulting in greater involvement in getting patients back in the workforce.

Secondarily, this study examined how CMs—key stakeholders in the RTW process—perceive the role of HCPs. In most jurisdictions across Canada (except Quebec), CMs act as the ultimate decision maker in the RTW process, overseeing claim compensation and RTW planning. HCPs are bound by the legislative requirements of their provincial WC system, and their engagement in the RTW process can be influenced by their relationship to WCB decision makers [17, 20]. On the other hand, CMs rely heavily on the input of HCP and communicate with them regularly to get IWs back to work [20]. Successful RTW depends on various stakeholders—WCB, employers, IWs, and HCPs—working together [21, 22]. According to role theory, when individuals are responsible for working together to achieve a desired outcome, they may have different perceptions of given roles [18, 23]. Although WCBs have specific expectations from HCPs in the RTW process, little is known about how WC decision makers perceive the roles of HCPs. Given CMs and HCPs dependence on one another to achieve successful RTW, understanding how CMs perceive the roles and responsibilities of HCPs can shed light on what is expected of them in the RTW process.

The overall aim of the study was to examine how HCPs and CMs perceive the HCP role in the RTW process, and the extent of HCP involvement. By incorporating the perspectives of relevant stakeholders, we can begin to understand the similarities and differences surrounding perceptions of the HCP role, and how these views, in turn, inform broader expectations of HCPs.

Workers’ Compensation in Canada

Each province and territory in Canada has its own WCB. These WC systems are based on a historical compromise where IWs gave up the right to sue their employers in exchange for benefits (e.g. wage replacement, health care) and employers pay regular premiums in exchange for protection against lawsuits. WC systems in Canada are no-fault and publicly administered. WCBs pay health care professionals for their services (e.g., treating an IW, filling out forms). After treating an IW, HCPs can bill their relevant WCB for their services as outlined in the WCB fee schedule. In order for an IW to receive workplace compensation benefits, the injury or condition must be a direct result of the employment. However, what is recognized as a compensable condition varies by jurisdiction. For example, in some provinces gradual onset work-related mental health claims are permitted, while other jurisdictions only permit mental health claims for conditions that arise due to sudden and unexpected traumatic events (e.g. post-traumatic stress disorder). Each jurisdiction uses medical evidence to help with decision making and claim management, however, only in Quebec is the HCP decision binding [20]. In the four provinces where this study took place (British Columbia, Manitoba, Newfoundland and Labrador, and Ontario), the ultimate decision maker regarding RTW issues is the WC decision maker, typically the CM. Most WCBs have a specific section of their websites for HCPs, however, these do not necessarily clearly outline the expected role of HCPs in the WC and RTW process [17].

Methods

The findings come from data collected as a part of a larger qualitative study examining HCPs experiences with their respective provincial WCB. Interviews with HCPs and CMs explored the experiences of HCPs with the WC system. These interviews also explored the RTW of compensation claimants and CMs interactions with, and perceptions of, HCPs in RTW. This analysis specifically focusses on HCPs’ (general practitioners and specialists) and CMs’ perception of the role of HCPs in the RTW process.

Recruitment and Sampling

The study sample included CMs and HCPs from four provinces (British Columbia, Manitoba, Newfoundland and Labrador, and Ontario), from both rural and city centres, with varying volumes of IW patients to ensure diversity of experiences with the WCBs. The sampling of participants was based on analytical grounds and emerging concepts. That is, the data were collected and analyzed simultaneously and participant recruitment continued until no new themes emerged in the data [24, 25].

HCPs were recruited through clinics and healthcare centres, as well as researchers’ pre-existing contacts in professional networks and medical associations. In order to participate in the study, HCPs had to have seen at least one patient with a workplace injury in the previous year. Those interested in being interviewed contacted the research team.

CMs were recruited through the WCBs in British Columbia and Manitoba. WCBs in Ontario and Newfoundland and Labrador declined to assist with recruitment and have their current staff participate in the study. No CMs were recruited in Newfoundland and Labrador. In Ontario, only CMs working in private companies were recruited, although they may have been former WC CMs. In participating WCBs (British Columbia and Manitoba), the organization provided the research team with a list of individuals to contact after gaining their consent. Researchers directly contacted the individuals on the list in order to render potential participants less identifiable to those who may have referred them.

An email was sent to the appropriate individuals with information about the study. This was followed up with phone calls to determine interest levels and to answer any questions. An invitation was then issued to participate in the study, which included a consent form. Limits to confidentiality were discussed with all participants and included in the study information sheet. Ethical review and approval was provided by the University of Toronto. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Procedure

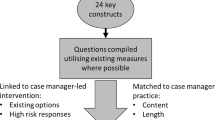

One-on-one semi-structured interviews were conducted between May and November 2015 by experienced interviewers who were hired in each of the four provinces. An interview guide was developed collaboratively with the research team and study advisory committee, which included representatives from a number of the WCBs, HCPs, workers, and employers. Interviews with HCPs focused on their involvement in RTW, their experiences with IW patients, interactions with the WCB in their jurisdiction and other stakeholders (CMs, employers, allied HCPs). Interviews with CMs focused on their experience interacting with IWs, their use of medical evidence, and their views on the role of HCPs. The semi-structured interview format allowed for follow-up questions and new avenues of inquiry.

Interviews lasted between 30 and 60 min and were held in-person or via telephone, depending on participant location and availability. All interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. Written consent to record the interview was obtained prior to the start of the interview. Participants were given an honorarium as a thank you for their time. Some participants declined the honorarium.

Participants

In total, 69 HCPs and 34 CMs were interviewed. The HCP sample included 50 general practitioners and 19 specialists (e.g., surgeons, oncologists, industrial and sports medicine) (see Table 1). Although the original sample of the study included a more diverse group of HCPs (e.g. internal HCPs to WCBs, allied HCPs), allied HCPs and internal medical consultants (IMCs) are not included in this analysis. The majority of the IMCs were physicians who were paid by the WCBs to review and provide expertise on patient files. They only review case files and do not examine workers. Allied HCPs (e.g., chiropractors, physiotherapists) provided specific treatments to IWs, and IWs were often referred to them when needed. For the purposes of this paper, the focus was on the perceptions of physicians and specialists, who are often the first point of contact for workers following an injury. Many HCPs had experience working in different settings; for example, as both a walk-in clinic physician and a general practitioner. This ensured diverse perspectives on RTW and WC process. Almost half of the HCPs studied had over 15 years of tenure, whereas 20% had been practicing < 5 years. More than half of the HCPs (67%) practiced in large city centres, while the rest were from medium-sized cities and small towns. 33% of the CMs had over 15 years of experience (within or outside of WCBs), while 22% had < 5 years of experience. CMs worked in a range of roles, including vocational rehabilitation, adjudication of long-term claims, and adjudication of mental health claims.

Data Analysis

A thematic content analysis was used to organize data systematically and to identify, analyze, and report themes [26]. Thematic analysis shares many similarities with grounded theory. An important difference is that thematic analysis does not always lead to a theoretical model [26]. This type of analysis involves reading interview transcripts and assigning codes, inductively. That is, researchers do not use predetermined themes when analyzing the data. During our analysis, both thematic and descriptive codes were used. Transcripts were entered into NVivo (qualitative data analysis software) for storage and coding [27]. In the first phase of coding, three researchers read a sample of interview transcripts and established a preliminary list of codes [28]. The content assigned to these codes was reviewed by the research team and a coding manual was developed. It included a definition for each code and an explanation for how its content would apply to the research objectives. Transcripts were then coded in two rounds by two researchers. Common themes and concepts across codes that captured key insights were identified. Any discrepancies in coding and interpretative differences were discussed in team meetings and resolved through discussion until a 100% agreement was reached. This was required for a theme to be included as part of the final analysis. When needed, a third researcher was involved in these discussions as an independent coder. Data pertaining to each of the codes was then reviewed and common themes were identified [28]. Contradictions, silences, and gaps in the data were considered and discussed [29]. An ongoing review of the data led to a deeper understanding of HCPs’ experiences, challenges, and strategies regarding the compensation processes and RTW [30]. A second analysis was carried out by the first author with a specific focus on the role of HCPs in the RTW process and the compensation system more broadly.

Findings

Almost all participants agreed that the main role of HCPs was to diagnose injuries and provide appropriate treatment. In addition, the majority of HCPs and CMs viewed providing medical information to WCB and the general encouragement of RTW as important roles played by HCPs. However, unlike the medical role of injury assessment and treatment, there was less clarity—and at times disagreement—about the role of the HCPs in providing medical information to WCB and encouraging RTW. For the most part, CMs and HCPs had different expectations regarding these roles. In the next section, we will discuss these similarities and differences, as well as the challenges HCPs experience in performing these roles.

Diagnoses and Treatment of Injury

All HCPs described the treatment of the injury, whether work-related or not, as their foremost priority.

Work related injury, whether it’s work related or some other injury that happened, we treat it the same way as any other injury. We try to treat the medical problem, or the mental problem, and whether the insurer is the provincial insurance or the WC insurance is the same thing for us, it don’t matter, right, we treat the individual, we treat the person, we try to provide what’s available and what’s fit for that particular injury, whether its mentally or physically. (P#53, HCP, NL)

Similarly, most CMs described the key role of HCPs as the diagnosis and treatment of injury. They shared the perception that HCPs have the ability to diagnose injuries and prescribe treatments. HCPs were usually the first contact for patients in the RTW process and were relied on by the WCB in the diagnosis of injuries or conditions.

General Encouragement of RTW

Encouragement of RTW was viewed by both HCPs and CMs as an important part of the HCP role. Part of the reasoning behind this belief was the shared recognition that employment is economically and socially beneficial to IWs. Many HCPs described how having early conversations with their patients about RTW was an effective means of encouraging them to start planning their return while undergoing treatment. Many CMs believed that by leveraging the positive relationships HCPs have with their patients, HCPs could help ensure that RTW is a central focus during recovery. They recognized that HCPs were uniquely positioned to support the RTW process by establishing RTW as an expectation of their patients.

A physician from BC explained that helping workers mentally prepare for RTW was a critical part of the support that was offered to patients, especially ones struggling with pain or mental health. This encouragement meant addressing pain issues, adjusting treatments, and providing ongoing assessments.

Diagnosis, treatment, lots of pain management, and I usually talk to the patient from the very first meeting about getting back to work and just preparing them mentally that this is an injury, you know, it’s self-limiting, it’s going to take a bit of time to heal from it, and I give them a time frame as to what it is, if it’s a fracture or a soft tissue injury, and then sort of what the normal expectations are in terms of healing and recovery. And just kind of set them up for “you’re going to get back to work” so, it’s not forever […] I feel like I do a lot of support and encouragement. (P#117, HCP, BC)

Despite the agreement on encouraging RTW, HCPs and CMs had different perceptions of “early” RTW, particularly when it came to IWs with complex and prolonged injuries. Most HCPs expressed that while encouraging RTW is important, their role as physicians is to recognize and incorporate individual circumstances into their treatment, rather than simply pushing for early RTW. They felt pressure from WCB to get IWs back on the job before they were ready, sometimes while factors such as individual readiness, the nature of the injury, and workplace conditions were overlooked.

My other random overriding difficult thing with WSIBFootnote 1 is I’ve talked with some of the WSIB physicians who at times have called me, and they’re pushing for this early return to work. They cite and there is obviously a lot of medical literature that says if you’re off work for a longer period of time you’re less likely to go back to work, which is out there. But I find that a lot of times whoever I’m talking to doesn’t put this in context of who the patient is because yes, if you’re off longer you’re less likely to go back. However, there’s also this correlation in part of people who are off longer, often they have a more severe injury so hence that may be why they’re less likely to go back and not just because they didn’t get pushed back sooner. (P#8, HCP, ON)

Conversely, most CMs viewed work as rehabilitation and had strong views on the positive impact of recovery at work: “the earlier somebody can RTW, in any capacity, get back to the workplace, the higher success rate” (P#103, CM, BC). As such, CMs often expected HCPs to encourage early RTW, and sometimes felt that HCPs relied too heavily on workers’ assessments of their own health status and RTW readiness. CMs were frustrated when HCPs suggested rest or prolonged time away from the workplace. This frustration was apparent in a number of the CMs’ statements arguing that HCP should only provide information, and not weigh in on RTW timelines.

It’s not up to the physician to make the decision that they can’t work. It’s up to the physician or the treaters to tell us what the function level is. (P#66, CM, MB)

Overall, CMs viewed early RTW as overwhelmingly positive for the health of IWs, and communicated that recovery at work should be encouraged by HCPs. HCPs, on the other hand, had a more tempered view of the benefits of early RTW, pointing to the importance of factors such as recovery time, the nature of the injury, and workplace conditions. Because HCPs are expected to provide an expected RTW date, this different approach to early RTW may result in frustration on the part of HCPs and disagreements between key stakeholders.

Providing Medical Information

Although both CMs and HCPs saw providing medical information as the core role for HCPs in the RTW process, they had different expectations regarding the type of information that HCPs should provide. CMs emphasized objective assessment as the most important factor for determining RTW readiness and expected HCPs to provide objective medical evidence and information on a patient’s functional limitations as part of their role. Objective evidence meant findings obtained by examinations and tests that identify the causes of injury and provide proof of disability. CMs criticized HCPs for relying on the IW’s subjective information—especially for issues such as pain—during their assessment and making recommendations based on non-medical factors. This resulted in, at times, CMs calling into question the capability of HCPs to determine functional limitations of IWs.

The information that [physicians] give us usually is a diagnosis, and a lot of subjective information. So, you know, in some instances it’s…if I can use the word, “Parroting”...they’re just telling us what the injured worker is telling them. You know, injured last week, can’t do this, can’t do that...but there’s no, there’s not a lot of objective information. There’s no physical examination findings. There’s no functional information and then you will get the limitations for work and it’ll just say “off work” or “light duties”, so you’re trying to connect the dots (P#126, CM, BC)

On the other hand, HCPs saw their role as taking into account the whole individual, and the unique situations faced by patients when providing information to the WCBs. There was recognition of the complexities of the medical conditions and IW’s subjective experience that shaped recovery and RTW. The issue of providing objective evidence was particularly challenging for more complex situations like chronic pain and mental health conditions, which rarely yielded objective, tangible findings to assess impairment or function.

The majority of HCPs recognized a connection between mental and physical health; often noting perception of pain or chronic pain as an influencing factor in recovery. However, for WCB decision-makers, ‘pain’ was viewed as a subjective phenomenon that was not accepted as a diagnosis or a reason to remain off work:

Well, I would say at least half of the cases that I see, that I feel have legitimate problems with the way the adjudication and claims recognition process went. A lot of it has to do with the ongoing pain and limitations from a work injury that the board no longer recognizes as their responsibility, and oftentimes, because it’s muscles, joints, and the tendons involved, it’s often best characterized as myofascial pain coming from muscles and connective tissue, but the board does not accept that as a diagnosis. They call it a descriptive term. And there’s a real mismatch between the clinical picture from the standpoint of the treating physician to what the board deems acceptable, and I feel that they remove themselves from the realities of many workers that do not recover well from their injury. (P#62, HCP, MB)

The different opinions regarding what constitutes acceptable evidence led to different role expectations. HCPs expressed that the requirement of objective evidence by CMs was problematic, especially when functional abilities are taken as the sole indicator of health status or RTW readiness. They expressed frustration, when, as the treating professional, their role was reduced to only providing information about physical function.

Some HCPs also reported challenges when it came to the assessment of functional limitations and RTW readiness. HCPs reported receiving almost no training in medical school related to work injury management and functional assessment. Similarly, most HCPs felt they had limited knowledge of a patient’s work environment or work demands, despite being expected to assess RTW readiness, and to initiate a RTW plan (e.g., schedule for graduated RTW) in some instances. As a result, most HCPs viewed the determination of specific RTW timelines and evaluating the suitability of work duties as outside the scope of their knowledge. WCB forms, however, require HCPs to provide functional limitation information and make recommendations regarding RTW, suggesting that this is an important part of the HCP role in RTW.

I guess I just find it sometimes funny that a physician’s expertise is called upon for this, even though the physician probably has the least knowledge of what is actually required of the patient at work, and whether or not their condition would limit them from doing it. (P#34, HCP, ON)

Overall, there was a lack of consensus on the scope HCPs’ role in providing medical information to the WCB, determining functional limitations, and assessing RTW readiness. Differing views on objective evidence, and HCPs’ lack of knowledge in functional limitations, were the major issues identified. HCPs felt ambiguity regarding their input in the decision-making process. Related to this, participant narratives revealed that some HCPs did not know whether their conclusions were accepted and expressed frustration at providing their medical opinion only to find out that it was not followed by the WCB.

I don’t really know what goes on behind the scenes. So when I send a claim, or any of my information, I don’t necessarily hear back from them, or I don’t sometimes know what’s happening. (P#107, HCP, BC)

On the other hand, CMs talked about using the recommendations provided by the HCPs as one of the information sources in making decisions. HCPs’ role was to provide information, but it was the CM who decided on the claim.

Advocacy

Another notable difference between HCPs and CMs was the perception of the advocacy role played by HCPs in the RTW process. CMs and HCPs had differing opinions on what constitutes advocacy and what measures HCPs should take in supporting their patients. Part of the challenge with having HCPs play an important role in RTW, and in the WC system more generally, had to do with a belief among some CMs that HCPs do what patients request, and not what is medically indicated.

For most HCPs, when advocacy was discussed, the term took on a different meaning. Many HCPs did view themselves as advocates for their patients, but this typically did not mean blindly doing what the patient desired. Rather, advocacy involved acting in a way that was in the best interest of the patient:

When a doctor writes that they don’t think a patient should go back to work, or ... when we write that we think they should stay off for one week and then return, whatever we write, you know, we don’t do that lightly.... I don’t take people off work just for fun, or because I’m being nice or bored, I take them off because I think they need the time off (P#29, HCP, ON)

For most HCPs, being a patient advocate meant keeping the patient’s best interest as the top priority. At times, this meant pushing workers out of their comfort zones as a way to help foster a timely RTW. For other HCPs, advocacy meant educating patients about their own needs and limitations, what is expected of them, and what they should watch out for during the RTW process.

And, especially if they’ve been off for a couple of months, getting them to push past their new comfort zone, based on their pain, based on their injury, and get them back to being more functional. It’s a little more motivational, perhaps, than medical. And I like to educate. Right. So I want my patient to leave understanding. I don’t want them to leave, saying, he had all these big words, all this clinical mumbo-jumbo, I don’t know what he talked about. So I want the patient to go away having a layman’s term conversation, knowing what’s wrong with them, so they have an understanding. If they have an understanding in what’s wrong with them, then they’re a key player in helping to fix that problem. So I think that’s the smoothest part of my practice. Is doing that. (P#85, HCP, MB)

CMs felt that patient advocacy sometimes resulted in negative outcomes for the patient, such as delayed RTW and a declining patient health. Some CMs even viewed patient advocacy as resulting in a dangerous ‘us vs. them’ dynamic, with the WCB and the HCP/IW on opposite sides.

Some physicians fall into the advocacy role, they don’t understand their role as being professionals and not trying to be advocates all the time. Sometimes, people are starting from, I’ve got to protect this person from the large organization, syndrome. But, when you explain to them what it’s all about, then they go, oh, well, if that’s the way you’re going at it that suits me fine. (P#5, CM, ON)

These divergent views could create an atmosphere of tension and adversity between the CMs and HCPs. The below HCP statement illustrates the tension surrounding the advocacy role.

I would remind the people at the WSIB that the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario regulations stipulate that a physician has to play an advocacy role for a patient. Yet what the WSIB does is completely ignores any doctor who is taking care of a patient precisely because they are advocates. So, this just makes this an absurd situation. This is the kind of thing that Franz Kafka would have dreamt up. We’re supposed to be advocates but we’re not supposed to be advocates. Okay? And, the assumption is that we’re not going to be objective about the patient. Oh, right, as if the doctors who used to be on their payrolls, or the nurses who are still on their payrolls, are objective, when their work incentives are related to how many people can they kick off the payroll. (P#35, HCP, ON)

As the HCP quote above illustrates, the CMs’ perception that the WCB’s IMCs (HCPs hired by the WCB to review medical files and help CMs make decisions) are objective, but treating HCPs are biased, was an issue raised by a number of HCPs. Some HCPs were concerned that IMCs—given that they were paid by the WCB—were not independent, and having them weigh in on work readiness, treatment, or benefit entitlement was problematic. Some HCPs believed that CMs could cherry pick opinions offered by internal consultants, choosing those favourable to the WCB (e.g. ones that reduced costs). Conversely, CMs tended to view IMCs as being independent and not influenced by pre-existing doctor-patient relationships.

Our doctors… treat it as a claim, a claim is a claim is a claim, they don’t treat it as a claim who happens to be my neighbour or a claim that I happen to have dealings with their father and their grandfather. And they basically look at the condition and the natural history of such a progression of a condition. They look at the case and all the medically relevant information and the other stuff of the other doctors that are treating these people. Formally, they have some type of unbiased opinion hopefully [So they can objectively look at the claim?] Yes. (P #79, CM, MB)

Discussion

Among the workplace compensation stakeholders examined in this study—CMs and HCPs—it is agreed upon that the primary role of HCPs is to provide diagnosis and treatment of IWs. However, aside from this established medical responsibility, there was less agreement regarding HCP involvement as it pertained to a number of other RTW issues, including acceptable evidence for claim adjudication, workplace readiness, and early RTW.

In many instances, CMs discussed the importance of evidence in determining the work readiness of an IW, which is determined primarily by functional abilities assessments. CMs saw that the primary role of HCPs was to provide objective evidence to inform the adjudication process. CMs expressed frustration when HCPs included subjective patient feedback when making recommendations. On the other hand, HCPs viewed it as important to incorporate individual experience in the RTW preparation. Some HCPs felt that their role was reduced to providing information about physical function and were frustrated when their diagnoses were ignored by CMs. This disagreement in what type of information should be provided, coupled with challenges experienced by HCPs in assessing functional abilities, may lead HCPs to feel disengaged from the RTW process and confused about their role. In addition, dismissing patient input as subjective and irrelevant may be counterproductive, ignoring valuable first-hand accounts that can shape RTW readiness [31].

Despite the general agreement that HCPs’ primary role should not be determining RTW readiness, different views on treatment and recovery at times led to conflicting role expectations. Almost all CMs discussed work as a form of therapy and focused on early RTW whenever possible. As a result, CMs expected HCPs to encourage early RTW in most cases, and they were frustrated when HCPs had different opinions on their patients rejoining the workforce. Although HCPs agreed on the positive impact that RTW has on IWs, they were cautious about pushing RTW prematurely, emphasizing the importance of considering individual (e.g. pain) and work-related (e.g., appropriately modified work) conditions.

Role theory suggests that differing role expectations and lack of role clarity may have consequences for role occupants, such as negative affect [32, 33] and impaired performance [34, 35]. This is especially true in situations where individual roles are characterized by a high degree of interdependence [23]. When relations between HCPs and WC decision makers become strained or when the demands placed on HCPs become onerous, HCPs may avoid participating in RTW [13].

There is a need for WC decision-makers to consider the views of HCPs when it comes to appropriateness of RTW, particularly in complicated cases such as mental health or chronic back pain. Although most HCPs lack of knowledge of employment conditions, they may be well positioned to recognize the factors that complicate recovery. This type of insight should not be ignored; rather it should be thoughtfully integrated into treatment and RTW planning.

The study findings highlight the importance of establishing clear role definitions for HCPs. When stakeholders with distinct views and distinct backgrounds work together, it is normal to expect some degree of confusion. But when confusion becomes the norm, there may be bigger issues at play. The narratives of HCPs and CMs revealed a lack of cohesion around the HCP role, which lead to uncertainty, frustration, and most importantly, has the potential to impede the RTW process.

We recommend that WCB policy-makers and HCPs work diligently to define and communicate the HCP role in the RTW process in their jurisdiction. Ideally, an open dialogue can lead to consensus and more effective, structured guidelines for RTW stakeholders to follow. Clarified roles and responsibilities should acknowledge that HCPs have different levels of capacity for RTW planning, functional assessment, and other relevant activities. The following are possibilities for the role of health-care providers: ongoing treatment of injury, championing appropriate RTW timelines and targets, identifying and flagging issues that may complicate recovery. Certain types of HCPs (for example, those specializing in occupational medicine or disability management) may be in a good position to take an active role in RTW planning. For example, some allied HCPs can conduct functional ability assessments and can gather further information about workplace conditions, such as job demands analyses that could guide HCPs in RTW recommendations.

The role ambiguity of HCPs suggests that additional work needs to be done to promote a more comprehensive understanding of the requirements of WC systems (e.g., reporting, assessments), how the WC system works, and how decisions are made. This information can be outlined in provincial WC websites. Some stakeholder frustrations might be mitigated with a more streamlined operations process, namely around issues such as the role that medical evidence plays in the decision-making process. For example, in all Canadian jurisdictions (except Quebec), the CM is typically the final decision maker, yet forms in many jurisdictions require HCPs to provide information about work readiness and in some cases, a concrete RTW date and recommended modified hours. It is possible that the questions posed on forms shape HCP perceptions about the decision-making role they should be playing in RTW and the WC process more broadly. It would be difficult to parse exactly who is best positioned to answer what question; the findings of this study suggest a need for collaborative decision-making process for RTW. Further investigation is recommended to explore the ways HCPs and CMs can work together in facilitating RTW decisions.

The question of what role HCPs should play in the WC process is without an easy answer. A dialogue between WCB decision-makers and HCPs is needed to bring clarity and consensus to their roles, and to ensure that a diversity of stakeholders can achieve a single goal: responsibly returning workers to safe employment.

Study Limitations and Strengths

This study was a part of a large qualitative study that provided valuable information from HCPs from four provinces who had different levels of involvement within the RTW process. In-depth, semi-structured interviews led to rich findings about how HCPs perceived their role in the RTW process. We were also able to access CMs who provided us with valuable insight into their expectations from HCPs roles.

As with all qualitative studies, this research does not tell us about the prevalence of particular events or about the percentage of HCPs experiencing the themes discussed. However, the fact that many of the themes discussed were repeated across jurisdictions lends credence to our findings. We did not interview other important stakeholders, IWs or employers, who interact with HCPs and may have different perspectives about the role of HCPs in RTW. Rather, the study provides insights into perceptions of two key stakeholders—HCPs and CMs—in the RTW process. Successful RTW depends on collaboration between all stakeholders (e.g., IWs, HCPs, insurers, employers) involved in the process -- a clear understanding of their roles, expectations, and responsibilities is needed for these stakeholders to work together to provide IWs with safe and timely RTW.

Notes

The Workplace Safety and Insurance Board.

References

Pransky G, Katz JN, Benjamin K, Himmelstein J. Improving the physician role in evaluating work ability and managing disability: a survey of primary care practitioners. Disabil Rehabil. 2002;24(16):867–874.

Ratzon N, Schejter-Margalit T, Froom P. Time to return to work and surgeons’ recommendations after carpal tunnel release. Occup Med. 2005;56(1):46–50.

Dasinger LK, Krause N, Thompson PJ, Brand RJ, Rudolph L. Doctor proactive communication, return-to-work recommendation, and duration of disability after a workers compensation low back injury. J Occup Environ Med. 2001;43(6):515–525.

Workplace Safety and Insurance Board. Guidelines for health care practitioners [Internet]. 2017. http://www.wsib.on.ca/WSIBPortal/faces/WSIBArticlePage?fGUID=835502100635000399&_afrLoop=2079797567126000&_afrWindowMode=0&_afrWindowId=null#%40%3F_afrWindowId%3Dnull%26_afrLoop%3D2079797567126000%26_afrWindowMode%3D0%26fGUID%3D835502100635000399%26_adf.ctrl-state%3D4f9qx5oxh_4. Accessed 24 Aug 2017.

O’Brien K, Cadbury N, Rollnick S, Wood F. Sickness certification in the general practice consultation: the patients perspective, a qualitative study. Fam Pract. 2008;25(1):20–26.

Nordin M, Cedraschi C, Skovron ML. 4 Patient-health care provider relationship in patients with non-specific low back pain: a review of some problem situations. Bailliere’s Clin Rheumatol. 1998;12(1):75–92.

Deyo RA. The role of the primary care physician in reducing work absenteeism and costs due to back pain. Occup Med (Philadelphia). 1988;3(1):17–30.

Kosny A, Franche ReL, Pole J, Krause N, Cote P, Mustard C. Early healthcare provider communication with patients and their workplace following a lost-time claim for an occupational musculoskeletal injury. J Occup Rehabil. 2006;16(1):25–37.

Schweigert MK, McNeil D, Doupe L. Treating physicians’ perceptions of barriers to return to work of their patients in Southern Ontario. Occup Med. 2004;54(6):425–429.

Wickizer TM, Franklin G, Plaeger-Brockway R, Mootz RD. Improving the quality of workers’ compensation health care delivery: the Washington State Occupational Health Services Project. Milbank Q. 2001;79(1):5–33.

Soklaridis S, Tang G, Cartmill C, Cassidy JD, Andersen J. Can you go back to work? Can Fam Physician. 2011;57(2):202–209.

Kosny A, MacEachen E, Ferrier S, Chambers L. The role of health care providers in long term and complicated workers’ compensation claims. J Occup Rehabil. 2011;21(4):582–590.

Brijnath B, Mazza D, Singh N, Kosny A, Ruseckaite R, Collie A. Mental health claims management and return to work: qualitative insights from Melbourne, Australia. J Occup Rehabil. 2014;24(4):766–776.

Kilgour E, Kosny A, McKenzie D, Collie A. Healing or harming? Healthcare provider interactions with injured workers and insurers in workers’ compensation systems. J Occup Rehabil. 2015;25(1):220–239.

Mazza D, Brijnath B, Singh N, Kosny A, Ruseckaite R, Collie A. General practitioners and sickness certification for injury in Australia. BMC Fam Pract. 2015;16(100):1–9.

Kosny A, Lifshen M, Tonima S, Yanar B, Russel E, MacEachen E, et al. The role of health-care providers in the workers’ compensation system and return-to-work process: final report. Toronto: Institute for Work and Health; 2016.

Kosny A, Lifshen M, MacEachen E, Furlan A, Koehoorn M, Beaton D, et al. What are physicians told about their role in return to work and workers’ compensation systems? An analysis of Canadian resources. Policy and Practice in Health and Safety. 2018, forthcoming.

Biddle BJ. Recent developments in role theory. Annu Rev Sociol. 1986;12(1):67–92.

Katz D, Kahn RL. The social psychology of organizations. 2nd ed. New York: Wiley; 1978.

Lippel K, Eakin JM, Holness DL, Howse D. The structure and process of workers compensation systems and the role of doctors: a comparison of Ontario and Quebec. Am J Ind Med. 2016;59(12):1070–1086.

Franche ReL, Cullen K, Clarke J, Irvin E, Sinclair S, Frank J, et al. Workplace-based return-to-work interventions: a systematic review of the quantitative literature. J Occup Rehabil. 2005;15(4):607–631.

MacEachen E, Clarke J, Franche RL, Irvin E. Workplace-based Return to Work Literature Review Group. Systematic review of the qualitative literature on return to work after injury. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2006;32(4):257–269.

Kahn RL, Wolfe DM, Quinn RP, Snoek JD, Rosenthal RA. Organizational stress: studies in role conflict and ambiguity. New York: Wiley; 1964.

Glaser BG. Basics of grounded theory analysis: emergence vs forcing. Mill Valley: Sociology Press; 1992.

Quinn PM. Qualitative research and evaluation methods. California EU: Sage Publications Inc; 2002.

Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101.

NVivo 10 [software program]. Version 10. QSR International; 2012 [computer program]. AJPE; 2014.

Thomas DR. A general inductive approach for analyzing qualitative evaluation data. Am J Eval. 2006;27(2):237–246.

Poland B, Pederson A. Reading between the lines: interpreting silences in qualitative research. Qual Inq. 1998;4(2):293–312.

Glaser BG, Strauss AL. The discovery of grounded theory. New York: Aldine; 1967.

Franche ReL, Krause N. Readiness for return to work following injury or illness: conceptualizing the interpersonal impact of health care, workplace, and insurance factors. J Occup Rehabil. 2002;12(4):233–256.

Lagace RR. Role-stress differences between salesmen and saleswomen: effect on job satisfaction and performance. Psychol Rep. 1988;62(3):815–825.

Terry DJ, Nielsen M, Perchard L. Effects of work stress on psychological well-being and job satisfaction: the stress-buffering role of social support. Aust J Psychol. 1993;45(3):168–175.

Abramis DJ. Work role ambiguity, job satisfaction, and job performance: meta-analyses and review. Psychol Rep. 1994;75(3_Suppl):1411–1433.

Sohi RS, Smith DC, Ford NM. How does sharing a sales force between multiple divisions affect salespeople? J Acad Mark Sci. 1996;24(3):195–207.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the members of the study advisory committee who provided feedback and input at key points of the study: Dan Holland, Ann Lovell, David McCrady, Peter Rothfels, Kim Roer, Michael Zacks and Alec Farquhar.

Funding

This study was funded by the Workers Compensation Board of Manitoba through the Research and Workplace Innovation Program.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Yanar, B., Kosny, A. & Lifshen, M. Perceived Role and Expectations of Health Care Providers in Return to Work. J Occup Rehabil 29, 212–221 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-018-9781-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-018-9781-y