Abstract

Numerous studies examined the association between character strengths—positive traits that comprise a good personality—and satisfaction with different aspects of life. However, few studies explored the connection between character strengths and marital satisfaction. The present study, conducted on a sample of 177 married couples, aims to examine this connection. Given the findings of previous studies, showing that both spouses’ personality traits contribute to relationship quality, we expect to find a connection between the spouses’ strengths and their marital quality. Using actor-partner interdependence model analyses, we examined the effects of three strengths factors (caring, self-control, and inquisitiveness) of both the individual and the partner on marital quality, evaluated by indices measuring marital satisfaction, intimacy, and burnout. Our findings revealed that the individual’s three strengths factors were related to all of his or her marital quality indices (actor effects). Moreover, women’s caring, inquisitiveness and self-control factors were associated with men’s marital quality, and men’s inquisitiveness and self-control factors were associated with women’s marital quality (partner effects). Our findings join the efforts of previous studies to understand the association between character strengths and the various elements of mental well-being, especially romantic relationships.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The Flourish model, one of the most famous theoretical models in the field of positive psychology, describes well-being as a structure comprising five factors: positive emotions, engagement, positive relationships, meaning, and accomplishments (PERMA). Each of the five factors independently contributes to well-being, and all are supported by 24 morally positively valued traits called “character strengths” (Peterson & Seligman, 2004; Seligman, 2012). The Flourish model expands on a previous theoretical model put forward by Seligman (2002), Authentic Happiness, offering several innovations, including the addition of accomplishments and positive relationships as necessary elements of well-being, and understanding character strengths as a mechanism that increases all of the PERMA factors—using character strengths will lead to more positive emotions, more engagement, better positive relationships, more meaning, and more accomplishments.

Many studies provide empirical support to the association between character strengths and well-being, linking character strengths with various positive indices such as resilience, academic success, work satisfaction, and life satisfaction (e.g., Littman-Ovadia et al., 2016; Martínez-Martí & Ruch, 2017; Park et al., 2004; Wagner et al., 2019). However, research examining the role of character strengths in positive relationships, especially marriage, remains limited.

Over the past several decades, the marital institution has undergone numerous changes. Following a rise in life expectancy and legislative, gender, and social changes, marriage was revolutionized when, for the first time in human history, the most common reason for its termination was no longer the death of one of the spouses, but divorce (Pinsof, 2002). These changes, which turned divorce into a simple and viable option, created circumstances in which ‘being married’ was no longer a satisfactory reason to stay married (Skerrett & Fergus, 2015). Since divorce has numerous negative implications for the couple and their children (Amato & Keith, 1991), we must search for and discover the qualities of an optimal marriage. A good relationship, in contrast to the negative effects of a bad relationship, is positively correlated with many indices, such as life satisfaction and self-esteem (Hawkins & Booth, 2005; Kiecolt-Glaser & Newton, 2001). Despite its benefits, much of the research and theoretical literature focuses more on the factors harming marriage than on what causes it to succeed (Fincham & Beach, 2010; Maisel & Gable, 2009; Skerrett & Fergus, 2015). In recent years, however, there has been a shift in this trend, with the publication of more and more studies concentrating on the positive elements of romantic relationships (Boiman-Meshita & Littman-Ovadia, 2020; Kashdan et al. 2018; Lavy et al. 2014; Maisel & Gable, 2009).

There is no single answer to the question what the contributing factors to marital quality are, but there is evidence suggesting that marital satisfaction is correlated with the personalities of the two spouses (Brau & Proyer, 2018; Dyrenforth et al., 2010; Javanmard & Garegozlo, 2013; Luo et al., 2008; Proyer et al. 2019; Robins et al. 2000; Shackelford et al., 2008; Watson et al. 2000; Weidmann et al. 2016). Character strengths are trait-like personality features that ‘exist in degrees and can be measured as individual differences’ (Park et al. 2004, p. 603). Indeed, since the character strengths model was developed almost two decades ago, there is a consensus among scholars on character strengths serving as personal assets and promoting various aspects of intrapersonal and interpersonal well-being (Freidlin & Littman-Ovadia, 2020; Russo-Netzer & Littman-Ovadia, 2019).

The character strengths model—which has been used in hundreds of theoretical and empirical studies—is expounded in the book Character Strengths and Virtues (Peterson & Seligman, 2004), which details 24 positive traits that are reflected or conveyed in the individual’s thoughts, emotions, and behavior (Park et al., 2004). These positive traits were selected from the variety of existing traits according to a number of criteria. A character strength, for example, is a trait that contributes to a person’s well-being and satisfaction, is valued in different cultures, and does not harm other people (Peterson & Seligman, 2004). In the original model, Peterson and Seligman (2004) proposed that the 24 strengths reflect six higher virtues: wisdom and knowledge, courage, humanity, justice, temperance, and transcendence.

While this division is grounded in theory, empirical advances present a more complex picture. Researchers examining the factorial structure of the VIA-IS have consistently found only 3–5 factors (Brdar & Kashdan, 2010; Littman-Ovadia & Lavy, 2012; Macdonald et al. 2008; McGrath, 2014; Singh & Chousbisa, 2010). It has been suggested that a factor analysis would not reflect the theoretical structure of the character strengths and virtues model, as it is not factorial to begin with (Ruch & Proyer, 2015). However, alternative methods, such as expert evaluations, have been shown to reconstruct the model almost in its entirety. While different validation methods yield different results, the most prevalent method in the literature is that of factor analysis.

The most comprehensive study utilizing factor analysis was conducted by McGrath (2015), who used data collected from more than a million subjects in four different samples. All samples replicated the three-component solution proposing that character strengths can be divided into three factors: caring, associated with strengths reflecting emotional and interpersonal issues, such as gratitude, kindness, love, teamwork, social intelligence, and leadership; self-control, associated with strengths that reflect the regulation and adoption ability in achieving values and goals, such as prudence, perseverance, self-regulation, honesty, and modesty; and inquisitiveness, associated with intellectual strengths driving inquiry and innovation, such as curiosity, creativity, zest, bravery, love of learning, and hope. Since its initial use, this three-component model has been replicated in numerous other samples (Duan & Bu, 2017; McGrath et al. 2017). Using these three higher-order factors instead of the 24 specific strengths, which has become more and more accepted in recent years (Cheng et al. 2020; Kashdan et al. 2018; Li et al. 2017), allows to cut down the number of statistical analyses, thus reducing the risk of errors. Consequently, these three factors were also used in the present study.

According to the PERMA model (Seligman, 2012), using character strengths leads to better relationships. When discussing marriage, Seligman spotlighted specific character strengths as having special significance. He listed several strengths associated with the self-control factor, such as prudence, self-regulation, modesty, and honesty; a number of strengths from the caring factor, like gratitude, forgiveness, and kindness; and the character strength of zest from the inquisitiveness factor as character strengths whose nurture and use in the marriage framework will improve marital quality (Seligman, 2002).

Indeed, a review of the literature points to a possible correlation between marital quality and any one of the three factors. For example, the caring factor is predicted to be related to marital quality of both spouses because it includes character strengths involving interactions with others, which have a strong theoretical and empirical link to relationships. The strength of love, for instance, characterizes people who can maintain and value relationships with others (Peterson & Seligman, 2004). A person with high expressions in this character strength is likely to take care, protect, and support his or her spouse and their joint children (Steen, 2003). In many respects, love represents commitment (Steen, 2003), an integral part of any relationship. Similarly, the kindness strength describes people who tend to help and take care of others (Peterson & Seligman, 2004). It is a form of altruism, involving concern for the welfare and feelings of the other (Reis et al., 2014), and helps contain differences between spouses in temperament, beliefs, values, and hobbies (Stosny, 2004). Studies conducted in recent years found that kindness is positively correlated with marital satisfaction in both spouses, and negatively correlated with marital conflicts and risk of separation (Dew & Bradford-Wilcox, 2013; Veldorale-Brogan et al., 2010; Wallace-Goddard et al., 2016). The forgiveness and gratitude strengths belonging to the caring factor are also important to maintaining the relationship and were found in numerous studies to correlate with marital quality in both spouses (Algoe et al., 2010; Braithwaite et al., 2011; Fincham et al., 2004; Gordon & Baucom, 2003; Gordon et al., 2011; Joel et al., 2013; Paleari et al., 2005; Wallace-Goddard et al., 2016).

Self-control is another factor with theoretical and empirical connections to marital quality. This factor includes strengths, like perseverance, prudence, and self-regulation, that urge one to carry on despite obstacles along the way, strengths that lead one to resist momentary gratification in order to achieve long-term goals and carefully consider the pros and cons of every situation before making a decision. The level-headed person looks ahead, being target-oriented and responsible (Peterson & Seligman, 2004). People with high self-control are perceived as more reliable (Righetti & Finkenauer, 2011), and they are better at managing their anger (DeWall et al., 2007). Indeed, a study by Vohs et al. (2011) found that as the sum of both partners’ self-control increases, so does their relationship quality.

The third factor, inquisitiveness, associated with intellectual strengths that spur inquiry and innovation, is also predicted to correlate with marital quality. The strengths encompassed by this factor emphasize mental abilities, like curiosity, love of learning, and creativity, that are important to the relationship. Curiosity, for example, could increase the attention paid to the interlocutor and to the topics of conversation during an interpersonal interaction (Kashdan & Roberts, 2004). A person characterized by curiosity is likely to be more responsive, showing interest and asking questions, than a person with low levels of curiosity, thus making the interlocutor feel understood, important, and valued. Consequently, as studies show, the feeling of closeness between the two interlocutors will increase (Kashdan & Roberts, 2004; Kashdan et al., 2012). Moreover, it is possible that a person with intellectual strengths like creativity could find new ways to reinvigorate the relationship, preserve the passion, and settle conflicts. The inquisitiveness factor also includes bravery and hope, characterizing people unafraid of challenges (Peterson & Seligman, 2004), which is important considering the many challenges involved in marital life.

Despite theoretical connections between the strengths factors and marital quality, only little empirical support has been provided. An exception is the study by Kashdan et al. (2018), which examined participants’ perceptions of the benefits and costs of their romantic partner’s strengths, and their associations with the quality of the relationship. In this study, participants’ strengths factors were treated as covariates, and it found that both appreciation and perceived cost of a partner’s strengths are correlated with several relationship outcomes, beyond the partner’s strengths factors. While this study examined a number of outcomes and provided an important assessment tool, it left unanswered the question of the relationship between both partners’ character strengths factors and their marital quality. Another study on the association between character strengths and the quality of the romantic relationships has been conducted by Lavy et al. (2014), studying the associations between both partners’ character strengths (endorsement) and the opportunities they have to use these strengths in the relationship (deployment), with the partners’ relationship satisfaction. Their findings showed that both the partners’ strengths endorsement and their strengths deployment are associated with their relationship satisfaction. However, in that study, the researchers chose to treat all strengths as a single unit, leaving a gap in our knowledge of the link between specific character strengths factors and relationship quality.

Considering these gaps in the literature, the following questions arise: Do the partner’s strengths contribute to marital quality (partner effect) beyond the contribution of the individual’s own strengths (actor effect)? Would there be different effects in men and women? In order to answer these queries, we conducted the present study. In our study, we used the Actor-Partner Interdependence Model (APIM, Cook & Kenny, 2005). This method takes into account the interdependency between the two partners, both in predictor and outcome variables, and simultaneously calculates the within-person (actor) and between-person (partner) effects. Studies that utilized the APIM model demonstrated that despite the partners’ effects being generally smaller than those of the actors, they have a unique contribution in explaining relationship quality, for both partners (Kashdan et al., 2018; Lavy et al., 2014).

In the current study we used the APIM to simultaneously examine the effect of one’s individual strengths (actor effect) and the effects of their partner’s strengths (partner effect) on marital quality. Marital quality was examined through three different aspects: satisfaction, intimacy, and burnout.

2 Method

2.1 Participants

The study sample comprised 177 heterosexual married couples. All 354 participants were in their first marriage and reported that they did not have children from previous relationships. 93% of couples completed the demographic questionnaire, providing the information below. The duration of the relationship ranged from 1 to 48 years (M = 8.35, SD = 8.54), and that of the marriage ranged between 0.5 and 45 years (M = 4.85, SD = 8.41). The number of children ranged between 0 and 5 (M = 0.76, SD = 1.08), with 56.1% of couples not having children while completing the questionnaire, 24.4% had one child, 9.8% had two children, and the rest (9.7%) had three children or more.

With regards to income, 17.5% of couples reported very high income compared to the national average, 28.1% slightly higher income than average, 10.0% average income, 13.8% slightly lower income than average, and 30.6% reported very low income compared to the national average. All couples resided in Israel.

The age range of the men in the sample was 20–72 (M = 32.25, SD = 8.83) and that of the women was 20–67 (M = 30.18, SD = 8.15). Most participants (70.9%) had an academic degree, 15.3% had tertiary education, 13.0% had secondary education, and 0.8% had partial secondary education or primary education.

2.2 Instruments

2.2.1 The VIA Inventory of Strengths (VIA-120)

Character strengths were assessed using the Hebrew version of the VIA-120 inventory (Littman-Ovadia, 2015), a shorter version of the VIA-IS self-report questionnaire developed by Peterson and Seligman (2004). This version comprised 120 items, with each of the 24 strengths assessed by five items. Creativity, for example, was evaluated by items such as ‘I like to think of new ways to do things,’ and perseverance by items like ‘I never leave a task before it is completed.’ Participants were asked to rate on a five-point Likert scale how accurately did each item describe them, with 1 standing for ‘very much unlike me’ and 5 for ‘very much like me.’ The inventory yielded 24 scores for each participant, with each score being the mean rating of the five items comprising a character strength. In order to avoid the large number of statistical analyses necessary to assess all 24 strengths, we grouped the strengths into three factors, as is accepted in recent literature (Kashdan et al., 2018; McGrath, 2015; McGrath et al., 2017). The first, labeled Caring, includes the strengths of gratitude, kindness, love, teamwork, forgiveness, and leadership. The second, labeled Self-control, includes the strengths of prudence, perseverance, self-regulation, modesty, and honesty. The third, labeled Inquisitiveness, includes the strengths of curiosity, creativity, zest, bravery, love of learning, and hope. The grouping has been done by averaging strengths belonging to the same factor, according to the factor division suggested by McGrath et al., (2017).

The internal consistency of all three factors was satisfactory (caring: α = 0.80 for men, α = 0.77 for women; self-control: α = 0.71 for both men and women; and inquisitiveness: α = 0.79 for men, α = 0.77 for women).

2.2.2 Dyadic Adjustment Scale (DAS)

Marital satisfaction was assessed through the Hebrew version of the self-report DAS (Spanier, 1976), a questionnaire extensively used around the world (Christensen et al., 2010; Solomon et al., 2011). Despite being originally developed to evaluate marital adjustment, its central use in the literature has been to assess marital satisfaction (Christensen et al., 2010), as was done in the present study. The questionnaire included 32 items, asking participants to rate the level in which each item described their marriage (an example item: ‘How often do you and your partner quarrel?’). Due to the varying response scales of the questionnaire’s items, the total score was calculated by summing the 32 items (possible scores ranged between 0 and 151), with higher scores representing positive marital satisfaction. The DAS has been previously found to have good psychometric properties (Heyman et al., 1994; Montesino et al., 2013), as was the case in the present study (α = 0.92 for men and α = 0.90 for women).

2.2.3 The Personal Assessment of Intimacy in Relationships Inventory (PAIR)

We assessed intimacy between partners using four subscales—emotional intimacy, social intimacy, intellectual intimacy, and recreational intimacy—of the self-report PAIR inventory (Schaefer & Olson, 1981). Each subscale comprised six items (including three reverse scoring items), asking participants to rate their level of agreement on a scale ranging from 0 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). The total score was the mean rating of all the items, with higher scores representing higher intimacy. Internal consistency was high and equal for men and women (α = 0.83).

2.2.4 Burnout Measure (BM)

The participants’ burnout was evaluated using the Hebrew version of the self-report Burnout Measure (Pines & Aronson, 1988). This measure comprised 21 items describing different feelings in three dimensions of exhaustion: emotional, physical, and mental. Participants were asked to rate the frequency in which they experienced these feelings on a 7-point Likert scale with 0 standing for ‘never’ and 6 for ‘always.’ The score was the mean rating of all 21 items, with a higher score representing higher burnout. The reliability of the measure in the current study was high (α = 0.91 for men and α = 0.92 for women).

2.3 Procedure

After receiving approval for the study from the Ariel University Ethics committee, we proceeded with participant recruitment. Participants were recruited in two ways: most participants (139 couples) were recruited using advertisements on notice boards and social media; the rest (38 couples) participated as part of the requirements for completing a B.A. degree in behavioral sciences and psychology. After participants signed an informed consent form, they received an email with links to the questionnaires and explanations on how to complete them. Each subject completed the questionnaires anonymously and individually, with identification done using two subject numbers: the personal subject number and the partner’s number. The subject numbers were the last four digits of each participant’s I.D. number, the full I.D. number remaining unknown to the experimenters. This method of identification allowed us to match spouses’ questionnaires while maintaining the subjects’ anonymity and preventing exposure of personal information.

2.4 Data Analysis

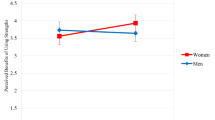

The Actor-Partner Interdependence Model (APIM; Cook & Kenny, 2005) is a model of dyadic relationships that considers the interdependence between the dyad’s members and employs a statistical method for evaluating predictors and outcomes for both partners simultaneously. The effect of one’s own strengths on one’s marital quality is termed actor effect, while the effect of the partner’s strengths on one’s marital quality indices is termed partner effect (see Fig. 1). In the present study we conducted nine APIMs (Kenny et al., 2006), in which each of the three strengths factors separately predicted marital satisfaction, intimacy, and burnout. In the first stage, we examined all models twice—once treating dyad members as distinguishable by gender, and once treating them as indistinguishable. We compared the two methods by using chi-square difference tests, which were significant in all comparisons (i.e., p < 0.20; Kenny & Ledermann, 2010). Therefore, we concluded that gender makes a statistically meaningful difference. In the second step, we explored this gender difference in each of the effects (actor and partner). When no significant gender differences were detected, we reported the general effects; when significant gender differences were detected, we reported each spouse’s effect separately. In all analyses we computed coefficient Δ, which describes the changes in the outcome measure in units of SD when the predictor variable is changed by one point (see Brauer & Proyer, 2018). The coefficient Δ was computed separately for each gender to account for their difference variance. In all models, years of marriage were included as a between-dyad covariate. We performed these analyses using the APIM_SEM free application (Stas et al., 2018).

3 Results

Table 1 presents mean averages, standard deviations, and paired samples t-test scores of study variables by gender. As seen in Table 1, and in line with the findings of previous studies (Maslach et al., 2001), a significant difference was found between women and men in burnout, according to which women had higher levels of burnout than men had. Additionally, a significant effect was found for inquisitiveness, according to which men had higher levels of inquisitiveness than women had. No significant differences between men and women were found in the other study variables.

Table 2 presents correlations between spouses’ strengths factors. As demonstrated in Table 2, all correlations between the different strengths factors are significant, except for the correlation between inquisitiveness among men and self-control among women.

Prior to exploring the research questions, we assessed the couples’ interdependence in the outcome variables using Pearson correlations. All correlations were significant (r(176) = 0.69, p < 0.001 for marital satisfaction; r(176) = 0.62, p < 0.001 for intimacy; and r(176) = 0.34, p < 0.001 for burnout), representing statistical interdependence between partners.

To test our research questions, we conducted nine APIMs (Kenny et al., 2006), using the APIM_SEM free application (Stas et al., 2018). Results are presented in Table 3, demonstrating that all actor effects were significant for both men and women. The three strengths factors were positively correlated with marital satisfaction and intimacy and negatively correlated with burnout. Gender differences were found for three paths: caring and marital satisfaction, caring and intimacy, and inquisitiveness and intimacy.

In addition, we found four significant partner effects: two for women, and two in common. Specifically, we found positive significant paths between women’s caring factor and men’s marital satisfactions and intimacy, and a positive common path for both men and women between inquisitiveness and self-control factors and the partner’s marital satisfaction.

APIM analyses for each of the 24 strengths are presented in the Supplementary Information As seen in the Supplementary Information, most actor and partner effects for marital satisfaction were significant for both men and women. Examination of the actor effects showed that women’s marital satisfaction was most highly related to love, gratitude, zest, honesty, and social-intelligence; and men’s marital satisfaction was most highly related to love, honesty, social-intelligence, prudence, and hope. The analysis of the partner effects revealed that women’s marital satisfaction was most highly related to men’s honesty, social-intelligence, prudence, perseverance, and judgment; and men’s marital satisfaction was most highly related to women’s love, kindness, gratitude, forgiveness, and honesty. For intimacy and burnout analyses, please see the Supplementary Information.

4 Discussion

The goal of the present study was to empirically examine the relationship between character strengths and marital quality among married heterosexual couples. Our findings suggest that the individual’s strengths factors correlate with marital quality for both men and women. The strengths factors were positively correlated with marital satisfaction and intimacy and negatively correlated with burnout.

Especially interesting are the findings concerning the dyadic level—the associations between the partner’s strengths and the individual’s marital quality (partner effect). Our findings suggest that the partner’s strengths factors were associated with the individual’s marital quality beyond the individual’s own strengths, and that this effect, in some outcomes, is different in men and women. Specifically, women’s caring was associated with men’s satisfaction and intimacy: the higher the woman’s level of caring is, the higher her spouse’s levels of intimacy and marital satisfaction are. In addition, partner effects were found for self-control and marital satisfaction, as well as for inquisitiveness and marital satisfaction, for both partners: the higher the partner’s inquisitiveness and self-control are, the higher their spouse’s marital satisfaction is. The association between men’s caring and women’s marital satisfaction, as well as the association between one’s self-control and his or her partner’s burnout, had a robust size (Δ > 0.20), but they did not reach the threshold for significance.

The actor effects we found adhere to the primary criterion for defining a personal trait as a character strength: traits that contribute to satisfaction and to a better and more fulfilling life. Consequently, these effects provide some support for Seligman’s PERMA model (Seligman, 2012), according to which using character strengths will contribute to better relationships.

The PERMA model is further supported by our findings displaying the contribution of the partner’s strengths to the individual’s marital quality, beyond the individual’s own strengths. These findings highlight the importance of these strengths not only to the person who endorses them, but also to that person’s significant other (Peterson & Seligman, 2004). These effects expand previous findings that point to the link between the partner’s strengths and the individual’s life satisfaction and marital satisfaction (Kashdan et al., 2018; Lavy et al., 2014; Weber & Ruch, 2012).

Interestingly, the partner effects of inquisitiveness and self-control on marital satisfaction were similar in both spouses, despite the slight difference in the sizes of the effects. A possible explanation for the relation between self-control and marital satisfaction comes from Gottman and Gottman’s theory (2008), whereby there are several behaviors that could harm the marriage when displayed during a conversation between spouses about a loaded topic in the relationship. A partner characterized by self-control, capable of not doing or saying things that he or she will later regret, would be able to avoid destructive responses, thus preventing damaging the relationship and contributing to its quality.

In addition, a person with better self-control is perceived as more reliable (Righetti & Finkenauer, 2011), making it easier for others to trust him or her. Trust is one of the most important components in a relationship and is correlated with relationship satisfaction (Atta et al., 2013). Therefore, trust may be a mediating variable between self-control and marital satisfaction; future studies are advised to examine this possibility.

The relation between both partners’ inquisitiveness and their marital satisfaction could be explained in several ways: first, partners with high inquisitiveness factor may have more flexible thinking compared to partners with low inquisitiveness. This could allow them to think about more effective ways to manage conflicts, come up with new ways to ‘spice up’ the relationship, thereby leaving their partner more satisfied with the relationship. In addition, according to the self-expansion model (Aron & Aron, 1997), relationships that offer their members opportunities for self-expansion are satisfying, because people often achieve self-expansion through the inclusion of the other in the self. Therefore, compared to a partner with low inquisitiveness, one with high levels of this factor would have more opportunities to expand the self, allowing them to feel better about their relationship.

In line with the findings of other studies (e.g., Algoe et al., 2010; Braithwaite et al., 2011; Fincham et al., 2004; Gordon et al., 2011; Joel et al., 2013; Reis et al., 2014), our findings emphasize the relation between the caring factor and marital quality, for both partners, through actor effects. However, the partner effect for caring was found only for women, showing that men’s marital quality is related to both partners’ interpersonal and emotional qualities.

Gender differences were also found in inquisitiveness, a factor expressing curiosity and creativity, with women found to have lower levels of this factor than men. It is important to mention that despite differences in averages between men and women were found in this factor, its association to relationship quality does not change as dependent on gender (apart from differences in size, but not in direction, in actor effects of inquisitiveness and intimacy). Several studies examined gender differences in the 24 character strengths (Heintz et al., 2019; Linley et al., 2007; Littman-Ovadia & Lavy, 2012), and they have indeed found that women have higher levels than men in most strengths, apart from creativity. Yet as far as we know, gender differences in the three strengths factors have yet to be researched. Follow-up studies should examine whether this is a difference characterizing the population as a whole or unique to married couples.

Our findings also provided initial evidence that partners show similarity in the three strength factors. This finding is in line with previous findings in relationship research which found similarities between partners’ personality traits (e.g., Brauer & Proyer, 2018; Luo, 2017), and even similarities between partners’ specific character strengths (like honesty, hope, spirituality, and fairness in Weber & Ruch, 2012). Our findings are embedded within previous studies in this important topic in relationship research and suggest that in strengths factors, too, there is a similarity between partners. Future studies are recommended to examine whether this similarity has a unique contribution to predicting relationship quality, beyond the contributions of the strengths themselves.

The current study has important theoretical and practical implications. As far as we know, this is the first study to examine the link between the three strengths factors and marital quality, thus joining previous research efforts to understand the importance of character strengths to marriage (e.g., Kashdan et al., 2018; Lavy et al., 2014; Steen, 2003; Weber & Ruch, 2012) and expanding the theoretical body of knowledge on this subject.

From a practical perspective, identifying the strengths factors relevant to marital quality is essential for advancing strengths-based couples therapy, and for understanding which strengths should be nurtured in order to improve the relationship. However, since ours was a correlative research, its findings should be treated with caution.

4.1 Study Limitations and Proposals for Future Research

This study had several limitations. First, our sample was comprised mostly of couples in which both spouses volunteered for the study. This may point to certain personality traits, such as higher than average altruism, that may limit the ability to draw general conclusions from our findings.

Second, we only used self-report measures in this study. In self-report questionnaires, the subjects’ responses could have a possible deviation due to social desirability (Macdonald et al., 2008). In order to avoid such a deviation, we maintained the anonymity of participants, thinking that a subject whose details are unknown will not feel the need to embellish existing reality. Another possible criticism of these questionnaires concerns their subjective nature and the lack of objective scales with which to measure the dependent variables and marital quality. In this regard, it is important to note that marital satisfaction, intimacy, and burnout are all subjective variables, so this was the most natural, and therefore most common, way to measure them.

Third, this was a correlative study, which examined the link between variables at one time point, and therefore does not allow to draw conclusions about causality. Hence, it is recommended that future studies will conduct longitudinal research that will allow to draw conclusions about the direction of the link. Furthermore, this study examined the relationship between marital quality and endorsement of strengths, but not the opportunity to actively use them. We suggest that follow-up studies examine if and how using the strengths found in the current study relates to the relationship, and whether it is possible to over- or under-use these strengths within the marital framework (Niemiec, 2013). Moreover, we did not examine whether couples’ strengths change in different stages of the relationship, in same-sex couples, or following shifts in marital quality (as suggested by McNulty & Fincham, 2012). We recommend that future studies will examine these points.

References

Algoe, S. B., Gable, S. L., & Maisel, N. C. (2010). It’s the little things: Everyday gratitude as a booster shot for romantic relationships. Personal Relationships, 17(2), 217–233. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6811.2010.01273.x.

Amato, P. R., & Keith, B. (1991). Parental divorce and the well-being of children: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 110(1), 26–46. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.110.1.26.

Aron, A., & Aron, E. N. (1997). Self-expansion motivation and including other in the self. In S. Duck (Ed.), Handbook of personal relationships: Theory, research and interventions. Wiley.

Atta, M., Adil, A., Shujja, S., & Shakir, S. (2013). Role of trust in marital satisfaction among single and dual-career couples. International Journal of Research Studies in Psychology, 2(4), 53–62. https://doi.org/10.5861/ijrsp.2013.339.

Boiman-Meshita, M., & Littman-Ovadia, H. (2020). The marital version of three good things: A mixed-method study. Journal of Positive Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2020.1716046.

Braithwaite, S. R., Selby, E. A., & Fincham, F. D. (2011). Forgiveness and relationship satisfaction: Mediating mechanisms. Journal of Family Psychology, 25(1), 551–559. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0024526.

Brauer, K., & Proyer, R. T. (2018). To love and laugh: Testing actor-, partner-, and similarity effects of dispositions towards ridicule and being laughed at on relationship satisfaction. Journal of Research in Personality, 76, 165–176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2018.08.008.

Brdar, I., & Kashdan, T. B. (2010). Character strengths and well-being in Croatia : An empirical investigation of structure and correlates. Journal of Research in Personality, 44(1), 151–154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2009.12.001.

Cheng, X., Bu, H., Duan, W., He, A., & Zhang, Y. (2020). Measuring character strengths as possible protective factors against suicidal ideation in older chinese adults: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health, 20(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-8457-7.

Christensen, A., Atkins, D. C., Baucom, B. R. W., & Yi, J. (2010). Marital status and satisfaction five years following a randomized clinical trial comparing traditional versus integrative behavioral couple therapy. Journal of Counseling and Clinical Psychology, 78(2), 225–235. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018132.

Cook, W. L., & Kenny, D. A. (2005). The Actor-Partner Interdependence Model: A model of bidirectional effects in developmental studies. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 29(2), 101–109. https://doi.org/10.1080/01650250444000405.

Dew, J., & Bradford-Wilcox, W. (2013). Generosity and the maintenance of marital quality. Journal of Marriage and Family, 75(5), 1218–1228. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12066.

DeWall, C. N., Baumeister, R. F., Stillman, T. F., & Gailliot, M. T. (2007). Violence restrained: Effects of self-regulation and its depletion on aggression. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 43(1), 62–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2005.12.005.

Duan, W., & Bu, H. (2017). Development and initial validation of a short three-dimensional inventory of character strengths. Quality of Life Research, 26(9), 2519–2531. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-017-1579-4.

Dyrenforth, P. S., Kashy, D. A., Donnellan, M. B., & Lucas, R. E. (2010). Predicting relationship and life satisfaction from personality in nationally representative samples from three countries: The relative importance of actor, partner, and similarity effects. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 99(4), 690–702. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020385.

Fincham, F. D., & Beach, S. R. H. (2010). Of memes and marriage: Toward a positive relationship science. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 2(1), 4–24. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1756-2589.2010.00033.x.

Fincham, F. D., Beach, S. R., & Davila, J. (2004). Forgiveness and conflict resolution in marriage. Journal of Family Psychology, 18(1), 72–81. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.18.1.72.

Freidlin, P., & Littman-Ovadia, H. (2020). Prosocial behavior at work from the lens of character strengths. Frontiers in Psychology., 10, 3046. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.03046.

Gordon, C. L., Arnette, R. A. M., & Smith, R. E. (2011). Have you thanked your spouse today?: Felt and expressed gratitude among married couples. Personality and Individual Differences, 50(3), 339–343. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2010.10.012.

Gordon, K. C., & Baucom, D. H. (2003). Forgiveness and marriage: Preliminary support for a measure based on a model of recovery from a marital betrayal. The American Journal of Family Therapy, 31(3), 179–199. https://doi.org/10.1080/01926180301115.

Gottman, J. M., & Gottman, J. S. (2008). Gottman method couple therapy. In A. S. Gurman (Ed.), Handbook of couple therapy. (4th ed.). Guilford Press.

Hawkins, D. N., & Booth, A. (2005). Unhappily ever after: Effects of long-term, low-quality marriages on well-being. Social Forces, 84(1), 451–471. https://doi.org/10.2307/3598312.

Heintz, S., Kramm, C., & Ruch, W. (2019). A meta-analysis of gender differences in character strengths and age, nation, and measure as moderators. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 14(1), 103–112. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2017.1414297.

Heyman, R. E., Sayers, S. L., & Bellack, A. S. (1994). Global marital satisfaction versus marital adjustment: An empirical comparison of three measures. Journal of Family Psychology, 8(4), 432–446. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.8.4.432.

Javanmard, G. H., & Garegozlo, R. M. (2013). The study of relationship between marital satisfaction and personality characteristics in Iranian families. Procedia: Social and Behavioral Sciences, 84(9), 396–399.

Joel, S., Gordon, A. M., Impett, E. A., Macdonald, G., & Keltner, D. (2013). The things you do for me: Perceptions of a romantic partner’s investments promote gratitude and commitment. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 39(10), 1333–1345. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167213497801.

Kashdan, T. B., Blalock, D. V., Young, K. C., Machell, K. A., Monfort, S. S., McKnight, P. E., & Ferssizidis, P. (2018). Personality strengths in romantic relationships: Measuring perceptions of benefits and costs and their impact on personal and relational well-being. Psychological Assessment, 30(2), 241–258. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0000464.

Kashdan, T. B., McKnight, P. E., Fincham, F. D., & Rose, P. (2012). When curiosity breeds intimacy: Taking advantage of intimacy opportunities and transforming boring conversations. Journal of Personality, 79(6), 1369–1402. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.2010.00697.x.

Kashdan, T. B., & Roberts, J. E. (2004). Trait and state curiosity in the genesis of intimacy: Differentiation from related constructs. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 23(6), 792–816. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.23.6.792.54800.

Kenny, D. A., Kashy, D. A., & Cook, W. L. (2006). Dyadic data analysis. Guilford Press.

Kenny, D. A., & Ledermann, T. (2010). Detecting, measuring, and testing dyadic patterns in the Actor-partner interdependence model. Journal of Family Psychology, 24(3), 359–366. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0019651.

Kiecolt-Glaser, J. K., & Newton, T. L. (2001). Marriage and health: His and hers. Psychological Bulletin, 127(4), 472–503. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.127.4.472.

Lavy, S., Littman-Ovadia, H., & Bareli, Y. (2014). My better half : Strengths endorsement and deployment in married couples. Journal of Family Issues, 37(12), 1730–1745. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X14550365.

Li, T., Duan, W., & Guo, P. (2017). Character strengths, social anxiety, and physiological stress reactivity. PeerJ, 5, e3396. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.3396.

Linley, P. A., Maltby, J., Wood, A. M., Joseph, S., Harrington, S., Peterson, C., Park, N., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2007). Character strengths in the United Kingdom: The VIA inventory of strengths. Personality and Individual Differences, 43, 341–351. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2006.12.004.

Littman-Ovadia, H. (2015). Brief report: Short form of the VIA inventory of strengths: Construction and initial tests of reliability and validity. International Journal of Humanities, Social Sciences and Education, 2(4), 229–237.

Littman-Ovadia, H., & Lavy, S. (2012). Character strengths in Israel. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 28(1), 41–50. https://doi.org/10.1027/1015-5759/a000089.

Littman-Ovadia, H., Lavy, S., & Boiman-Meshita, M. (2016). When theory and research collide: Examining correlates of signature strengths use at work. Journal of Happiness Studies, 18, 527–548. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-016-9739-8.

Luo, S. (2017). Assortative mating and couple similarity: Patterns, mechanisms, and consequences. Social and Personality Psychology Compass. https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12337.

Luo, S., Chen, H., Yue, G., Zhang, G., Zhaoyang, R., & Xu, D. (2008). Predicting marital satisfaction from self, partner, and couple characteristics: Is it me, you, or us? Journal of Personality, 76(5), 1231–1266. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.2008.00520.x.

Macdonald, C., Bore, M., & Munro, D. (2008). Values in action scale and the Big 5: An empirical indication of structure. Journal of Research in Personality, 42, 787–799. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2007.10.003.

Maisel, N. C., & Gable, S. L. (2009). For richer in good times and in health: Positive processes in relationships. In S. L. Lopez & C. R. Snyder (Eds.), Oxford handbook of positive psychology. (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press.

Martínez-Martí, M. L., & Ruch, W. (2017). Character strengths predict resilience over and above positive affect, self-efficacy, optimism, social support, self-esteem, and life satisfaction. Journal of Positive Psychology, 12(2), 110–119. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2016.1163403.

Maslach, C., Schaufeli, W. B., & Leiter, M. P. (2001). Job burnout. Annual Review of Psychology, 52(1), 397–422. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.397.

McGrath, R. E. (2014). Scale- and item-level factor analyses of the VIA Inventory of Strengths. Assessment, 21(1), 4–14. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191112450612.

McGrath, R. E. (2015). Integrating psychological and cultural perspectives on virtue: The hierarchical structure of character strengths. Journal of Positive Psychology, 10(5), 407–424. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2014.994222.

McGrath, R. E., Greenberg, M. J., & Hall-Simmonds, A. (2017). Scarecrow, Tin Woodsman, and Cowardly Lion: The three-factor model of virtue. Journal of Positive Psychology, 13(4), 373–392. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2017.1326518.

McNulty, J. K., & Fincham, F. D. (2012). Beyond positive psychology? Toward a contextual view of psychological processes and well-being. American Psychologist, 67(2), 101–110. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0024572.

Montesino, M. L. C., Gómez, J. L. G., Fernández, M. E. P., & Rodríguez, J. M. A. (2013). Psychometric properties of the Dyadic Adjustment Scale (DAS) in a community sample of couples. Psicothema, 25(4), 536–541. https://doi.org/10.7334/psicothema2013.85.

Niemiec, R. M. (2013). VIA character strengths: Research and practice (The first 10 years). In H. H. Knoop & A. Delle Fave (Eds.), Well-being and cultures: Perspectives on positive psychology. Springer.

Paleari, F. G., Regalia, C., & Fincham, F. (2005). Marital quality, forgiveness, empathy, and rumination: A longitudinal analysis. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 31(3), 368–378. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167204271597.

Park, N., Peterson, C., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2004). Strengths of character and well-being. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 23(5), 603–619. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.23.5.603.50748.

Peterson, C., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2004). Character strengths and virtues: A handbook and classification. Oxford University Press.

Pines, A., & Aronson, E. (1988). Career urnout: Causes and cures. Free Press.

Pinsof, W. M. (2002). The death of “till death us do part”: The transformation of pair-bonding in the 20th century. Family Process, 41(2), 135–157. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1545-5300.2002.41202.x.

Proyer, R. T., Brauer, K., Wolf, A., & Chick, G. (2019). Adult playfulness and relationship satisfaction: An APIM analysis of romantic couples. Journal of Research in Personality, 79, 40–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2019.02.001.

Reis, H. T., Maniaci, M. R., & Rogge, R. D. (2014). The expression of compassionate love in everyday compassionate acts. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 31(5), 651–676. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407513507214.

Righetti, F., & Finkenauer, C. (2011). If you are able to control yourself, I will trust you: The role of perceived self-control in interpersonal trust. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 100(5), 874–886. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021827.

Robins, R. W., Caspi, A., & Moffitt, T. E. (2000). Two personalities, one relationship: Both partners’ personality traits shape the quality of their relationship. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79(2), 251–259. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.79.2.251.

Ruch, W., & Proyer, R. T. (2015). Mapping strengths into virtues: The relation of the 24 VIA-strengths to six ubiquitous virtues. Frontiers in Psychology., 6, 460. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00460.

Russo-Netzer, P., & Littman-Ovadia, H. (2019). “Something to live for” Experiences, resources and personal strengths in late adulthood. Frontiers in Psychology. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02452.

Schaefer, M. T., & Olson, D. H. (1981). Assessing intimacy: The PAIR inventory. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 7(1), 47–60. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1752-0606.1981.tb01351.x.

Seligman, M. E. P. (2002). Authentic happiness. New York: Free Press.

Seligman, M. E. P. (2012). Flourish: A visionary new understanding of happiness and well-being. Simon and Schuster.

Shackleford, T. K., Besser, A., & Goetz, A. T. (2008). Personality, marital satisfaction, and probability of marital infidelity. Individual Differences Research, 6(1), 13–25.

Singh, K., & Choubisa, R. (2010). Empirical validation of values in action-inventory of strengths (VIA-IS) in Indian context. Psychological Studies, 55(2), 151–158. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12646-010-0015-4.

Skerrett, K., & Fergus, K. (2015). Couple resilience: emerging perspectives . Springer.

Solomon, Z., Debby-Aharon, S., Zerach, G., & Horesh, D. (2011). Marital adjustment, parental functioning, and emotional sharing in war veterans. Journal of Family Issues, 32(1), 127–147. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X10379203.

Spanier, G. B. (1976). Measuring dyadic adjustment: New scales for assessing the quality of marriage and similar dyads. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 38(1), 15–28. https://doi.org/10.2307/350547.

Stas, L., Kenny, D. A., Mayer, A., & Loeys, T. (2018). Giving dyadic data analysis away: A user-friendly app for actor-partner interdependence models. Personal Relationships, 25(1), 103–119. https://doi.org/10.1111/pere.12230.

Steen, T. A. (2003). Is character sexy? The desirability of character strengths in romantic partners. Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: The Sciences and Engineering, 64(2–B), 1006.

Stosny, S. (2004). Compassion power: Helping families reach their core value. The Family Journal: Counseling and Therapy for Couples and Families, 12(1), 58–63. https://doi.org/10.1177/1066480703259041.

Veldorale-Brogan, A., Bradford, K., & Vail, A. (2010). Marital virtues and their relationship to individual functioning, communication, and relationship adjustment. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 5(4), 281–293. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2010.498617.

Vohs, K. D., Finkenauer, C., & Baumeister, R. F. (2011). The sum of friends’ and lovers’ self-control scores predicts relationship quality. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 2(2), 138–145. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550610385710.

Wagner, L., Gander, F., Proyer, R. T., & Ruch, W. (2019). Character strengths and PERMA: Investigating the relationships of character strengths with a multidimensional framework of well-being. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 15(2), 307–328. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-018-9695-z.

Wallace-Goddard, H., Olson, J. R., Galovan, A. M., Schramm, D. G., & Marshall, J. P. (2016). Qualities of character that predict marital well-being. Family Relations, 65(3), 424–438. https://doi.org/10.1111/fare.12195.

Watson, D., Hubbard, B., & Wiese, D. (2000). General traits of personality and affectivity as predictors of satisfaction in intimate relationships: Evidence from self- and partner-ratings. Journal of Personality. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6494.00102.

Weber, M., & Ruch, W. (2012). The role of character strengths in adolescent romantic relationships: An initial study on partner selection and mates’ life satisfaction. Journal of Adolescence, 35(6), 1537–1546. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2012.06.002.

Weidmann, R., Ledermann, T., & Grob, A. (2016). The interdependence of personality and satisfaction in couples. European Psychologist. https://doi.org/10.1027/1016-9040/a000261.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr. Boris I. Mints for his generous support of this research.

Funding

The first author received financial support for her Ph.D. studies from Ariel University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

This study is based on the dissertation of the first author, carried out under the supervision of the second author.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Boiman-Meshita, M., Littman-Ovadia, H. Is it me or you? An Actor-partner Examination of the Relationship between Partners’ Character Strengths and Marital Quality. J Happiness Stud 23, 195–210 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-021-00394-1

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-021-00394-1