Abstract

Rumination predicts wellbeing and is a core construct in the cognitive vulnerabilities to depression literature. Traditional measures of depressive rumination (e.g., Ruminative Responses Subscale, RRS; Treynor et al., 2003) rarely include items capturing thoughts about problems or events, even though these thoughts are in measures of related constructs (e.g., co-rumination, post-event processing). We created the Rumination on Problems Questionnaire (RPQ) for use on its own and with the RRS to capture rumination about problems and to align with measures of other ruminative and repetitive thinking processes. Our cross-sectional study of 927 undergraduates revealed the RPQ had a single factor, good internal reliability, convergent and discriminant validity, and significantly predicted depression, anxiety, and stress controlling for the RRS and co-rumination. Researchers and clinicians interested in rumination or cognitive vulnerabilities may wish to include the RPQ in their assessments. Measuring and addressing problem-focused rumination may be an important transdiagnostic treatment and prevention goal.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

According to Response Styles Theory (Nolen-Hoeksema & Morrow, 1991), rumination is the tendency to respond to distress by passively and repetitively thinking about one’s negative symptoms (e.g., feeling down), as well as the causes and consequences of those symptoms. Originally conceptualized as key process in the development and maintenance of depression, rumination has not only become a critical construct in the cognitive vulnerability to depression literature (Smith & Alloy, 2009), but has also shown consistent relations to a range of mental health problems. For example, rumination has been shown to prospectively predict the onset of depression symptoms and depression severity (see Nolen-Hoeksema, 2012; Rood et al., 2009 for reviews in adults and adolescents respectively) as well as to predict related mental health outcomes such as anxiety (e.g., McLaughlin & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2011; Olatunji et al., 2013) and alcohol use (e.g., Caselli et al., 2010; Wolitsky-Taylor et al., 2021). Rumination is believed to contribute to the development, maintenance, and exacerbation of these mental health challenges through mechanisms such as magnifying and/or prolonging negative emotions, reducing effective problem-solving behaviors (e.g., more difficulty generating and implementing solutions), reducing willingness to engage in positive or mood-enhancing activities, impairing concentration, and contributing to interpersonal difficulties (e.g., less social support, more social friction) (see Nolen-Hoeksema et al., 2008; Watkins & Roberts, 2020, for reviews).

Perhaps the most frequently used measure of rumination - the Ruminative Responses Subscale of the Response Styles Questionnaire (RRS; Treynor et al., 2003) – specifically assesses repetitive thoughts about symptoms of depression, their causes, and their consequences. Although the focus on ruminating on symptoms of depression is in line with Response Styles Theory (Nolen-Hoeksema, 1991), which asserts that rumination occurs in response to negative affect, notably absent from this popular measure are items tapping repetitive thoughts about problems or events, which may also occur when individuals feel down or face challenges.

The process of repetitively processing events or problems has been well-elaborated in the social anxiety literature (e.g., post-event processing, Clark & Wells, 1995), yet problem- or event-focused aspects of rumination are absent from the RRS and thus from much of the literature on depressive rumination. Given the links between exposure to negative events and depression (e.g., Hammen, 2005), as well as evidence that exposure to stressful life events predicts rumination (e.g., Michl et al., 2013), the comparative lack of assessment of ruminative thoughts about problems or events is striking. It is worth noting that the original and popular measure of co-rumination (i.e., when individuals excessively discuss problems and negative affect with a peer) - the Co-Rumination Questionnaire (Rose, 2002) – also explicitly captures co-rumination on problems (e.g., re-hashing the problem, choosing problem talk over other activities, speculation about problems, etc.), in addition to other aspects of co-rumination (e.g., dwelling on negative feelings). Further, in their review of the rumination literature, Smith and Alloy (2009) suggest that examining rumination about problems or stressors may be a useful complement to Response Styles Theory in order to tap a broader conceptualization of rumination. Additionally, in our clinical experience (e.g., depression prevention in early adolescent girls, Gillham & Chaplin, 2011), we also observed that ruminative thought often presented as problem-focused in nature (e.g., repeatedly going over details of a negative event), yet these aspects were not captured in our measurement tools.

In order to address this gap in the measurement of problem-focused aspects of rumination, we created the Rumination on Problems Questionnaire (RPQ). The RPQ was designed for use on its own and/or in combination with the RRS to capture rumination about events or problems, and to align with measures of other ruminative or repetitive thinking processes (e.g., co-rumination, post-event processing) that capture thoughts about challenges individuals face. The goals of the present study were: (1) Develop the RPQ to measure rumination focused on problems or events and to easily combine it with the RRS; (2) Examine RPQ’s psychometric properties; (3) Test if the RPQ relates to other measures of rumination and well-being; and (4) Determine if the RPQ accounts for unique variability in depression and related outcomes, over and above other measures of rumination and related constructs.

While much of the research exploring Response Styles Theory and rumination has used the RRS, thereby not capturing problem-focused aspects of rumination, there are measures of rumination and related processes that do capture problems or events. As noted above, much of this work has arisen from the social anxiety literature targeting post-event processing (Clark & Wells, 1995). Post-event processing includes persistent, repetitive, negative thinking (or rumination) about social situations specifically (Clark & Wells, 1995). Not surprisingly, the measures of rumination in the post-event processing literature focus on social situations (e.g., Abbott & Rapee, 2004; Blackie & Kocovski, 2017; Edwards et al., 2003; Fehm et al., 2008; Mellings & Alden, 2000; Rachman et al., 2000) and include items that focus on anxious and socially anxious ruminative processes (e.g., “How anxious I felt,” “I didn’t make a good impression,” Edwards et al., 2003; “To what extent did you think about the anxiety you felt during the interaction?”, Mellings & Alden, 2000; “How much anxiety did you experience?”, Rachman et al., 2000). While ideal for the study of repetitive thinking in social anxiety, these measures do not readily extend to rumination in other contexts.

Beyond the post-event processing in social anxiety literature, some existing measures of rumination do capture rumination on problems or events. The Ruminative Thought Style Questionnaire (RTSQ; Brinker & Dozois, 2009) includes a few items that mention rumination on negative events or problems. However, this questionnaire was designed to measure the general tendency to ruminate (across positive, neutral, or negative experiences in the past, present, and future) and was not intended as a measure of rumination on negative events or problems, specifically. Other measures of rumination on problem or events tend to focus on specific situations such as interpersonal offenses (Wade et al., 2008), or highly stressful or disruptive events (Cann et al., 2011). Further, similar to the RTSQ, some measures of rumination on problems include processes that are not typically considered rumination (e.g., avoidance behaviors, memory perspectives, Fehm et al., 2008; Rachman et al., 2000; whether thoughts were positive, negative or neutral, Mellings & Alden, 2000; experiencing shame, Fehm et al., 2008; reflecting on whether one has learned anything from a stressful event, forcing self to “deal with” feelings resulting from the event, Cann et al., 2011), and others include only a very small number of items tapping rumination on problems, events, or challenges (e.g., Garnefski et al., 2001; Ruscio et al., 2015). Further, some rumination measures focus on narrow or unique aspects of rumination (e.g., rumination on emotions after an event, Garnefski et al., 2001; ruminative thoughts that specifically reflect a hopeless or negative inferential style, Robinson & Alloy, 2003) or are vulnerable to similar criticisms of the RRS (Treynor et al., 2003) about “cross-contamination” between items on the rumination measure and on measures of mental health problems (e.g., Edwards et al., 2003; Mellings & Alden, 2000; Fehm et al., 2008; Rachman et al., 2000). Lastly, many rumination measures are state rather than trait focused (e.g., Abbott & Rapee, 2004; Edwards et al., 2003; Fehm et al., 2008; Mellings & Alden, 2000; Rachman et al., 2000; Wade et al., 2008). Thus, the RPQ was designed to capture trait or dispositional depressive rumination (i.e., an overall tendency to ruminate across time and situations) about a flexible range of problems or events (e.g., not exclusively social situations), to focus specifically on negative rumination on these problems, and to use a robust number of items that do not elicit concerns about cross-contamination with mental health symptoms.

In order to explore the psychometric properties of the RPQ and better understand the role of problem-focused rumination in depression and related outcomes, we explored a number of hypotheses in a cross-sectional study of undergraduate students. First, we anticipated a single factor structure of the RPQ. Second, in support of convergent validity, we expected the RPQ to correlate strongly and positively with established measures of rumination such as the RRS and RRS Brooding subscale, and moderately positively with an established measure of reflective rumination (i.e., RRS Reflective Pondering subscale). Brooding and reflective pondering are subtypes of depressive rumination, with brooding involving a passive focus on symptoms of depression, and reflective pondering involving active attempts to gain insight (Treynor et al., 2003). There is some evidence that brooding is more maladaptive than reflective pondering (e.g., Burwell & Shirk, 2007; Kim & Kang, 2022; Miranda & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2007). As the RPQ was designed to capture potentially harmful aspects of rumination, we anticipated stronger correlations with brooding than reflective pondering. In support of discriminant validity, we expected the RPQ to have a weak positive correlation with introversion (e.g., being reserved, low sociability, sober, quiet). We selected introversion as it is a well-established construct with a brief, readily available and valid measurement tool that might be associated with rumination, yet also demonstrably distinct. Given that introversion (or low extraversion) involves low levels of sociability, affection, friendliness, and talkativeness, and rumination itself is an individual, non-social, inward-focused process, we expected a small association between the two constructs (e.g., perhaps individuals who are low in sociability and talkativeness would tend toward rumination rather than co-rumination, for example). Indeed, a positive association between rumination and introversion has been shown in prior work (e.g., Conway et al., 2000; Trapnell & Campbell, 1999). However, given that introversion is a personality trait focused primarily on sociability, and rumination on problems involves repetitive negative thoughts about events, they are distinct enough that our measure must be able to discriminate between the two. Third, we expected the RPQ to be moderately to strongly positively correlated with measures of depression, anxiety, and stress. Lastly, we expected that the RPQ would positively predict depression, anxiety, and stress over and above the RRS and the RRS Brooding and Reflective Pondering subscales. If these hypotheses are supported, the RPQ has the potential to allow greater exploration of problem-focused rumination, its relation to well-being, and ultimately, to inform preventive and intervention efforts to address depression and related constructs.

Method

Transparency and Openness

This article complies with the Level 1 (Disclosure) Transparency and Openness Promotion Guidelines (Nosek et al., 2015). The study – design, hypotheses, analytic plan, etc. - was not preregistered. All measures not developed by the authors are cited in the method section, are listed in the reference list, and are freely available online or by request from their respective developers. Raw data and syntax used for this manuscript are available upon request from the corresponding author, and the questionnaire developed for this paper – the Rumination on Problems Questionnaire – is included in the appendix. As recommended by Simmons et al. (2012), the method section reports how we determined sample size, all data exclusions, all manipulations (there were none), and all measures analyzed for this paper. Additional measures were collected on some or all participants for use in other projects, but no measures beyond those listed in the measures section were analyzed at any point for this manuscript.

Participants and Procedures

In the current nonexperimental cross-sectional study, participants were 927 undergraduate students (ages 18–24) at two post-secondary institutions in the northeastern United States: a small liberal arts college and a mid-sized university. Sample size was not determined in advance; each semester in which data were collected, we collected data from as many participants as we could. Target enrollments approved by the Institutional Review Boards per academic year per institution ranged from 75 to 150, with varying success in reaching those targets each year. The age breakdown was as follows: 18 (n = 340, 36.7%), 19 (n = 345, 37.2%), 20 (n = 113, 12.1%), 21 (n = 80, 8.6%), 22 (n = 43, 4.6%), 23 (n = 5, < 1%), and 24 (n = 1, < 1%). The median age of participants was 19 and the majority (73.9%) were 18 or 19 years old. The majority of participants (n = 570, 61.4%) identified as female, while 346 (37.3%) identified as male, 11 (1.2%) identified as non-binary, gender fluid, or other. A total of 926 participants provided information about race and ethnicity. Of these, 808 (87.2%) selected one racial or ethnic identity. Of these, the majority of participants (n = 425; 45.8%) identified as Caucasian, 240 (25.9%) identified as Asian or Pacific Islander, 78 (8.4%) as Black or African American, 51(5.5%) as Latinx or Hispanic, 2 (< 1%) as Native American, and 12 (1.3%) as other. One hundred and eighteen (12.7%) participants selected multiple racial and ethnic identities. Of these, the most common were Asian/Pacific Islander and Caucasian (n = 51, 5.5%), Latinx/Hispanic and Caucasian (n = 28, 3.0%), Black/African American and Caucasian (n = 13, 1.4%) and Latinx/Hispanic and Black (n = 4, < 1%), and Native American and Caucasian, (n = 3, < 1%). Ten participants (1.1%) identified with three or more of the racial and ethnic identities listed.

All students in Introductory Psychology courses ages 18 and older at both institutions were invited to participate in the study for course research participation credit. For the majority of the sample, interested students were provided with a link to an online Qualtrics survey that contained the informed consent document along with the study questionnaires. Participants completed the study at the time and location of their choosing. Online survey completion times were reviewed; all participants spent more than 15 min on the survey, suggesting at least a minimal level of attention to items. For a small subset of participants (n = 54), informed consent and the survey were completed using pencil and paper. Paper surveys were administered in a small quiet lab room with one to three participants completing the survey per session and were proctored by one of the investigators. All participants were required to provide their names in order to receive course research participant credit, but the names were stored separately from all other data and could not be tied to individual responses. Data were collected over several academic years between 2014 and 2021.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

The study complied with APA ethical standards in terms of treatment of participants and was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at both institutions. All individual participants provided informed consent. The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Measures

Rumination

Rumination about problems and negative events was assessed with the Rumination on Problems Questionnaire (RPQ), a new measure that was developed for this study. The RPQ uses the same response format as Nolen-Hoeksema’s Response Styles Questionnaire so that the measures can be easily combined if desired. The prompt encourages participants to think about how they respond when they “feel down, face challenges, or experience problems.” The RPQ has 19 self-report items describing patterns of thinking and behavior. See appendix for full scale. Participants indicate the frequency with which each item applies to them using a 4-point scale from almost never to almost always. Examples of items include “Even when I try to let go of past problems, my thoughts about them still persist”, “I think over and over again about how bad my situation is”, and “I can easily move past negative events” (reverse scored). Higher scores on the RPQ reflect higher levels of rumination about problems and events. The RPQ demonstrated strong internal consistency in this study (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.94).

The Ruminative Responses Scale of the Response Styles Questionnaire (Davis & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2000; Nolen-Hoeksema & Morrow, 1991) was used to assess the tendency to ruminate or focus repetitively on one’s feelings of depression and the causes and consequences of those symptoms. Participants are asked to indicate how they respond when they feel “down, sad, or depressed” – there is no reference to problems, events, or challenges in the prompt. The RRS consists of 22 self-report items. Participants indicate the frequency with which each item applies to them (on a 4-point scale from almost never to almost always). Example items include “Think about how sad you feel” and “Think about all your shortcomings, failings, faults, and mistakes.” Several studies indicate that the RRS captures two different aspects of rumination: brooding, a passive focus on negative emotions and negativity towards the self (example item: Think “why do I have problems that other people don’t have”), and reflective pondering, a cognitive turning inwards to understand an experience and problem-solve (example item: “Go away by yourself and think about why you feel this way”) (Cox et al., 2001; Treynor et al., 2003). We calculated the total RRS score and scores representing the brooding and reflective pondering factors identified by Treynor et al. (2003). Higher RRS total scores, brooding scores, and reflective pondering scores reflect higher levels of rumination, brooding, and reflective pondering, respectively. The RRS and subscales demonstrated moderate to strong internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.93, 0.81, 0.77, for RRS, brooding, and reflective pondering, respectively).

Co-rumination

The Co-Rumination Questionnaire (CRQ; Rose, 2002) was used to measure the extent to which participants co-ruminate, or excessively and repetitively discuss and rehash personal problems and negative feelings with same-gender close friends. The CRQ contains 27 self-reported items. Participants rate the degree to which each statement describes them on a 5-point scale from “Not at all true” to “Really true”. Example items include: “When one of us has a problem, we talk to each other about it for a long time” and “We talk for a long time trying to figure out all of the different reasons why the problem might have happened”. Higher scores on the CRQ reflect higher levels of co-rumination. The instructions for the CRQ were slightly modified for use with an adult population and for online administration. Instead of instructing participants to “think about the way you usually are with your best or closest friends who are girls if you are a girl, or who are boys if you are a boy” (Rose, 2002), we asked participants to think about a friend of the same gender. The CRQ demonstrated strong internal consistency in this study (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.96).

Symptoms of Depression, Anxiety, and Stress

The Depression Anxiety and Stress Scale-21 (DASS-21; Lovibond & Lovibond, 1995) was used to assess participants’ experiences of symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress over the past week. The DASS-21 consists of three 7-item self-reported scales. The DASS-21 has been shown to have good psychometric properties and have several advantages relative to the full 42-item version, including shorter administration time, simpler factor structure, and lower interfactor correlations (Antony et al., 1998). Participants indicate how much each statement applied to them during the past week on a 4-point scale from “Did not apply to me at all” to “Applied to me very much, or most of the time”. Example items for depression, anxiety, and stress scales are “I couldn’t seem to experience any positive feeling at all”, “I was worried about situations in which I might panic and make a fool of myself”, and “I was intolerant of anything that kept me from getting on with what I was doing”, respectively. The DASS-21 yields 3 scores – one for each of its three subscales. Higher depression, anxiety, and stress scores reflect higher levels of depression, anxiety, and stress, respectively. The DASS-21 scales demonstrated moderate internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.88 for depression, 0.77 for anxiety, and 0.81 for stress).

Introversion

The Big Five Inventory - Extraversion scale (BFI-E; John et al., 1991) was used to assess participants’ levels of introversion. The BFI-E is designed to capture extraversion, a personality trait characterized by enthusiasm, sociability, talkativeness, and assertiveness. Low levels of extraversion indicate high levels of introversion, and vice-versa. The BFI-E consists of 8 self-reported items. Participants indicate the extent to which they agree with each item on a 5-point scale from “Disagree strongly” to “Agree strongly”. Example items include “I am a person who is talkative” and “I am a person who generates a lot of enthusiasm.” Scores on the BFI-E were recoded so that higher scores indicate a higher level of introversion. The BFI-E demonstrated moderate internal consistency in this study (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.87).

Data Analyses

Data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics, Version 28.0 (IBM Corp., 2012) and R statistical software version 4.0.2 (R Core Team, 2019). Prior to analysis, items were reverse-scored as needed, according to questionnaire scoring instructions. When at least 80% of the total number of items in a measure were completed, the measure score was prorated by averaging the available items. When more than 20% of the total number of items in a measure were identified as missing, the measure score was excluded from data analysis. Missing scores on study measures ranged from 0 (RPQ) to 17 cases (1.8%, Co-Rumination). Note that the Introversion measure was not administered to all cohorts of participants; it was administered in initial cohorts only to provide preliminary evidence of discriminant validity. The measure was subsequently dropped to shorten the administration time for participants. Thus, the sample size for this measure is smaller than the full sample (n = 466); there were no missing cases for Introversion among the participants who received the measure. Excluding introversion from missing values analyses (due to expected missingness), Little’s MCAR test demonstrated that all missing values (including age, gender, and race) were completely at random, χ2(15) = 10.31, p = .80. Note that due to all cases with missingness having more than 20% of the values missing, no permutation was performed. Missing data were excluded on a pair-wise basis. No other data exclusions were made.

Examining the Psychometric Properties of the RPQ

In addition to traditional examination of internal reliability, unidimensionality was also assessed in this study. Assessing unidimensionality, the existence of a single construct underlying all items in a measure, is critical in the scale development process (Hattie, 1985). A composite score is only meaningful if items in the measure are sufficiently unidimensional, reflecting a common construct (Gerbing & Anderson, 1988). The current study explored whether the RPQ is unidimensional using exploratory factor analysis (EFA) followed by confirmatory factor analyses (CFA). If both EFA and CFA results show that the single factor model fits the data well and the loadings of all items are sufficiently large, the RPQ can be considered to be unidimensional. As it is not recommended to apply EFA and CFA on the same dataset (Flora & Flake, 2017; Fokkema & Greiff, 2017), the original sample was randomly split into two subsamples for EFA (N = 275) and CFA (N = 652). We used approximately one third of the sample for EFA and 2/3rds of the sample for CFA as CFA requires a larger sample to yield robust results (Kyriazos, 2018).

After checking statistical assumptions for factorability (see results section), EFA was conducted on all 19 items using diagonally weighted least square estimator and an oblique (oblimin) rotation method, which allowed factors to correlate with each other. Number of factors to be retained was assessed using a visual scree plot in conjunction with parallel analysis (Howard, 2016). The plot test considers number points above the break or discontinuity of the graphical representation of eigenvalues (scree plot) as the number of factors to retain. In parallel analysis (Horn, 1965), the observed eigenvalues extracted are compared with the eigenvalues generated from a Monte-Carlo simulated dataset of the same size. A factor should be retained if the random order eigenvalues from parallel analysis are larger than the actual eigenvalues. Items with a primary factor loading of less than 0.40, or with an alternative factor loading of 0.30 or higher, or having a difference of 0.20 or less between their primary and secondary factor loadings were excluded from further analyses, as suggested by the 0.40-0.30-0.20 rule (Howard, 2016).

All items retained after the EFA procedure were subjected to further analysis using CFA. The diagonally weighted least squares estimation method was used to estimate model statistics. The following criteria were used to evaluate model fit: (1) Root Mean Squared Error of Approximation (RMSEA) < 0.05, (2) Comparative Fit Index (CFI) > 0.95, (3) Tucker Lewis Index (TLI) > 0.95, (4) Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) < 0.08. Due to its dependence on sample size, Chi-square values tend to increase with a large sample size and degrees of freedom. Thus, a non-significant Chi-square value was also considered as an indicator of model fit; however, it was not a deciding factor on whether the model would be accepted or rejected (Schermelleh-Engel et al., 2003). In the current study, items with factor loadings of 0.4 or higher were retained (Stevens, 2012). Internal consistency of the RPQ was then assessed using Cronbach’s alpha coefficient, corrected inter-total correlations, and alpha coefficient “if item deleted” analyses.

Relationship of the RPQ to Other Measures

We examined the RPQ’s relationship to other study measures using Pearson correlations. We expected the RPQ to correlate strongly and positively with established measures of rumination, especially the RRS and RRS Brooding scale. We expected the RPQ to be moderately to strongly positively correlated with measures of depression, anxiety, and stress scores (DASS). We expected the RPQ would only be weakly related to introversion which is a more distant construct.

RPQ as a Predictor of Unique Variability in Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Symptoms

We used regression analyses to examine whether the RPQ predicted unique variability in depression, anxiety, and stress (when controlling for the effects of other rumination and co-rumination measures). In these analyses, the DASS score was predicted from rumination (RRS), co-rumination, (CRQ), and RPQ. We conducted two sets of analyses, one using the RRS total score and the other examining RRS Brooding and Reflective Pondering scores. These analyses were conducted separately for each DASS scale (depression, anxiety, and stress). Prior to our primary regression analyses, we examined the variance inflation factor (VIF) for each of our predictors to screen for potential multicollinearity, given that the predictors are correlated. Recommended cut-offs for the VIF range from about 2.5 (Johnston et al., 2018) to 10 (Cohen et al., 2003); our VIF scores ranged from 1.126 to 2.143, reducing concerns about the potential effects of multicollinearity in our analyses.

Results

Factor Analyses of the RPQ

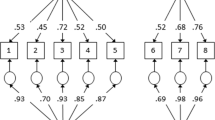

Before conducting EFA on our subsample (n = 275), a data assumption check was completed. The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure of sampling adequacy indicated that the strength of the relationships among variables was high (overall KMO = 0.95; range 0.93-0.98). Bartlett’s test of sphericity indicated high overall significance of all the correlations within the correlation matrix (χ2 (171) = 2673.38, p < .001). These indicators confirmed that it was acceptable to proceed with factor analysis. The scree plot and parallel analysis (Fig. 1) yielded a one-factor solution as the best fit for the data, accounting for 44.7% of variance. No item had a loading coefficient lower than 0.53. Thus, all 19 items were retained. The obtained pattern matrix is displayed in Table 1.

CFA with one-factor solution was employed on our second subsample (n = 652) to confirm the unidimensionality of the RPQ. The results with 19 items indicated a good fit of the data: χ2 (152) = 253.93, p < .05; RMSEA = 0.03, p > .05; CFI = 0.99; TFI = 0.99; SRMR = 0.05. No item had a loading of less than 0.4. Factor loadings ranged from 0.43 to 0.73.

Reliability Analyses for the RPQ

The overall value of Cronbach’s alpha for the resulting RPQ with 19 items was 0.94, which is considered excellent. All items were moderately to strongly correlated with the total score with correlation coefficients ranging from 0.50 to 0.71. No item removal resulted in an increase of the obtained Cronbach’s alpha.

Descriptive Statistics

Means and standard deviations for study variables are reported in Table 2. On the DASS, depression, anxiety, and stress scores spanned the full range from no symptoms to extremely severe levels of symptoms. Using the recommended DASS cut-off values (Lovibond & Lovibond, 1995), average scores were in the normal range for stress and between the normal and mildly elevated range for depression and anxiety. Note that “mild” elevation on the DASS is intended to reflect that the person is above the population mean, but well below what would be considered a diagnosable disorder and below what is common among individuals seeking mental health treatment.

Correlations of RPQ with Other Measures

Table 2 shows correlations among study variables using Pearson correlations. All correlations with the RPQ except for introversion were statistically significant. As predicted, the RPQ showed strong positive relationships with the RRS and the RRS brooding subscale. The RPQ showed moderate positive relationships with the RRS reflective pondering subscale and with co-rumination. These findings are in line with hypotheses and provide support for convergent validity of the RPQ. The nonsignificant correlation between the RPQ and introversion was anticipated and provides evidence of discriminant validity. Lastly, as anticipated, the RPQ was moderately positively correlated with depression, stress, and anxiety.

Examining RPQ as a Unique Predictor of DASS Outcomes

The RPQ significantly positively predicted depression, anxiety, and stress scores over and above RRS rumination and co-rumination scores (see Tables 3 and 4). RRS (total score as well as the brooding and reflective pondering subscales) positively predicted depression, anxiety, and stress in all analyses. Co-rumination positively predicted anxiety and stress, and negatively predicted depression when controlling for RPQ and RRS scores.

Discussion

In the current study, we explored the psychometric properties and predictive utility of the RPQ, a new measure of depressive rumination focused on the tendency to repetitively think about problems or negative events. Arguably the most popular measure of rumination – the Ruminative Response Scale from the Response Styles Questionnaire (Davis & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2000; Nolen-Hoeksema & Morrow, 1991) – focuses on repetitive thoughts about symptoms of depression, their causes, and their consequences, but does not capture ruminative thoughts focused on the problem or challenge itself. Although the RRS is intentionally in line with Response Styles Theory (Nolen-Hoeksema, 1991; Nolen-Hoeksema, 2004), Smith and Alloy (2009) noted examining rumination about problems or stressors would serve as a valuable complement to traditional Response Styles Theory. The RPQ is poised to provide this complement, as it focuses on rumination about problems when individuals experience negative events, challenges or depressed mood, allowing for a broader conceptualization of rumination.

Results from the current study were in line with hypotheses. First, results indicate that the RPQ has high internal consistency and a single factor structure. Second, as anticipated, the RPQ was significantly positively correlated with measures of rumination (i.e., RRS, RRS brooding subscale, RRS reflective pondering subscale) and co-rumination, providing evidence of convergent validity. Third, the RPQ was more weakly related to introversion than to established measures of rumination, providing initial evidence of discriminant validity. Lastly, the RPQ positively predicted depression, anxiety and stress, both in correlational analyses and in regressions, over and above the RRS, the RRS subscales, and co-rumination. The regression analyses in particular indicate that ruminating about events or problems is uniquely associated with important mental health outcomes.

The current findings are consistent with prior literature in a number of ways. First, the RPQ was associated with a range of mental health problems (depression, anxiety, stress) which mirrors past research showing rumination predicts various key mental health outcomes (e.g., depression, anxiety, alcohol use, suicide; Caselli et al., 2010; Olatunji et al., 2013; McLaughlin & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2011; Rogers & Joiner, 2017; Wolitsky-Taylor et al., 2021) and may be an important transdiagnostic risk factor (e.g., McLaughlin & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2011; Watkins & Roberts, 2020). Further, these findings are similar to past work looking at related constructs involving repetitive negative thoughts such as post-event processing (Clark & Wells, 1995) showing that high levels of post-event processing are associated with higher levels of mental health problems such as social anxiety (e.g., Abbott & Rapee, 2004; Blackie & Kocovski, 2017; Edwards et al., 2003; Fehm et al., 2008; Rachman et al., 2000), anxiety in general (e.g., Fehm et al., 2008) and depressive symptoms (e.g., Edwards et al., 2003; Rachman et al., 2000).

Taken together, these findings reinforce prior work on the links between rumination and mental health problems, provide data on the psychometric properties of the RPQ, and newly highlight that ruminating on problems or events specifically may be an important aspect of the rumination process. Although some past measures of rumination have captured rumination on problems, these measures have either focused narrowly on specific types of problems (e.g., Wade et al., 2008), are state rather than trait focused (e.g., Abbott & Rapee, 2004), include other constructs beyond rumination (e.g., Fehm et al., 2008), or have very few items (e.g., Mellings & Alden, 2000; Ruscio et al., 2015). The RPQ is unique in its focus on trait rumination on any type of problem(s) and its use of several items; its use will allow the field to more fully explore the links between rumination on problems and wellbeing, or, if used in combination with the RRS, to explore a broad conceptualization of rumination.

Although not the primary focus of our paper, we did find interesting results for co-rumination. In previous research, co-rumination has typically positively predicted depression (e.g., Rose, 2002; Spendelow et al., 2017; Stone et al., 2011), at times over and above rumination (e.g., Bastin et al., 2018; Rose, 2002; Rose et al., 2014; Stone et al., 2011). However, measures of rumination are not consistently included in the co-rumination literature (e.g., Rose et al., 2007; Waller & Rose, 2013), and when they are controlled for in analyses, sometimes the effects of co-rumination on depressive symptoms become nonsignificant (e.g., Rose et al., 2014; Stone & Gibb, 2015) or change to a negative relation (e.g., Rose, 2002). These changes in significance (and even changes in sign) prompted explorations of mediational models, and indeed there is evidence that rumination mediates the links between co-rumination and depression (e.g., Bastin et al., 2021; Stone & Gibb, 2015). In our analyses, while co-rumination continued to positively predict anxiety and stress with both the RRS and the RPQ in the regression model, co-rumination significantly negatively predicted depressive symptoms once the rumination measures were included. That is, more co-rumination was associated with less depression, not more. On the one hand, this finding is unexpected given that co-rumination has been shown to be a risk factor for depression even when controlling for rumination (e.g., Bastin et al., 2018; Stone et al., 2011). On the other hand, it is not entirely surprising that co-rumination negatively predicted depression when controlling for the RPQ and the RRS, given that it has also occurred in prior analyses (Rose, 2002). This change in sign may highlight a suppression effect (i.e., when an effect grows stronger or changes sign when an additional predictor is included in an equation; MacKinnon et al., 2000) in which co-rumination has competing indirect effects on depression – it leads to more depression through encouraging rumination (e.g., Bastin et al., 2021) yet may lead to less depression by strengthening friendships (e.g., Bastin et al., 2018, 2021; Felton et al., 2019; Rose, 2002, 2021). Once we partial out the effects of broadly defined rumination, the more adaptive aspects of co-rumination such as feeling more connected to your friend(s) (e.g., Felton et al., 2019; Rose, 2021) may emerge. Along these lines, past research has shown that some aspects of co-rumination are adaptive for depression (e.g., co-reflection as opposed to co-brooding, Bastin et al., 2014; Bastin et al., 2018), and rumination researchers have long proposed that both adaptive and maladaptive aspects of responding to/coping with stress can co-exist, although the presence of maladaptive strategies can reduce the beneficial effects of adaptive strategies on psychopathology (Aldao & Nolen-Hoeksama, 2012).

Given the role of interpersonal processes in depression (e.g., Bird et al., 2018; Coyne, 1976; Hames et al., 2013; Joiner, 2002; Joiner & Metalsky, 1995), it is also interesting to consider that the possible interpersonal benefits of co-rumination appeared to protect against depression but not anxiety or stress in our results. The strengthening of connections with friends through co-ruminative episodes may be particularly helpful for depression. However, we must be cautious in any interpretation as the inverse relationship between co-rumination and depression was significant but relatively small (β =-0.06). Further, although our collinearity diagnostics did not indicate problematic levels of collinearity, having correlated predictors can still result in more unstable regression coefficients (e.g., Johnston et al., 2018); replication of our findings is especially important.

Constraints on Generality

It is important to note that a major limitation of this study is the diversity of our sample. The sample is 61% female, 46% Caucasian, and 100% undergraduate students from post-secondary institutions in the Northeast United States that primarily (but not exclusively) serve US citizens, thereby limiting our ability to generalize to more diverse samples and the broader population in terms of age, race, ethnicity, sex, gender identity, nation of origin, and education levels. Replication of the work in more heterogenous samples in terms of a range of diversity factors even beyond those mentioned above (e.g., socioeconomic status, clinical status) will be important in the further validation of the measure, and in terms of understanding how the construct of rumination on problems relates to mental health symptoms more broadly. Understanding predictors of mental health in college populations and the development and validation of assessment tools for this group is still highly relevant and valuable given the rates of mental health problems and increasing mental health service utilization in this population (Center for Collegiate Mental Health, 2022; Gress-Smith et al., 2015; Lipson et al., 2019; Pedrelli et al., 2015), but researchers and clinicians should be wary of extending our conclusions beyond this group pending further investigation.

Additional Limitations, Clinical Implications, and Future Directions

There are two additional limitations to this study that are important to note. First, the study is cross-sectional and involves a single reporter; this design precludes conclusions about the direction of effects and raises concerns about shared method variance. Replication in future work – ideally longitudinal work and/or studies using multiple reporters – will be important. Second, we did not measure diagnoses of depression or anxiety, limiting the conclusions we can draw for clinical populations. Third, it is worth noting that a minority of participants (n = 92) participated in the study during the first full academic year of the COVID 19 pandemic (i.e., Spring 2021). It is possible that these individuals experienced more elevated levels of depression, anxiety, and stress than they normally would have; US adults in general showed higher levels of anxiety and depression during this time period (National Center for Health Statistics, 2020–2023). Also, given the increased likelihood of feeling isolated from friends and family during this time (e.g., quarantine, social distancing, remote learning, reduced in-person interactions), it is also possible they exhibited higher rates of rumination than they otherwise would have. However, we do not anticipate that the relations between rumination and mental health problems would differ during this time, even if mean levels were elevated.

In terms of clinical implications and future directions from the current study, there are a number of possibilities to consider. If the findings are replicated in longitudinal and especially experimental work, clinicians may want to use a broader conceptualization of rumination in their practice, beyond that described in Response Style Theory. Attending to the repetitive processing of problems or past events – in addition to rumination on symptoms of depression and their causes and consequences - may be helpful in prevention and intervention efforts and is in line with recommendations from Smith and Alloy (2009). It is worth noting, however, that clinicians may already use a broader understanding of rumination that includes rumination on problems in their clinical work, as we ourselves noted these types of repetitive thoughts on problems in our preventive intervention work with early adolescent girls (Gillham & Chaplin, 2011). However, having measures that better capture the types of rumination that are seen clinically will help future research better match clinical needs. Researchers can consider including the RPQ on its to own to explore rumination on problems specifically, or in addition to the more traditional RRS in their measurement of rumination, as both measures capture different aspects of the construct and can easily be compared or combined if desired given their use of the same rating scale.

In addition to longitudinal and experimental research, future studies should explore other psychometric properties of the RPQ (e.g., test-retest reliability) and its association with a broader range of wellbeing factors (e.g., alcohol use, suicidality, life satisfaction, happiness). Given past work identifying gender effects in rumination (e.g., Johnson & Whisman, 2013; Krause et al., 2018; Nolen-Hoeksema, 2012), it will also be important to examine the moderating role of gender on the link between rumination on problems and mental health outcomes. Further, future work exploring the RRS, the RPQ, and co-rumination simultaneously may help us better understand how co-rumination relates to depressive symptoms, while controlling for a broader conceptualization of rumination that also includes ruminating on problems, just as measures of co-rumination do. Lastly, exploration of rumination on problems as a mediator between stressful life events and depression may further elucidate the well-established links between stress and depression and identify targets for intervention.

In summary, the current study provides initial evidence for the psychometric strengths and predictive utility of the RPQ, a measure of the tendency to ruminate or dwell on problems or negative events and experiences. Analyses indicate that the RPQ has high internal consistency, a single factor structure, good convergent and discriminant validity, and predicted depression, anxiety, and stress symptoms over and above traditional measures of rumination and co-rumination. Adding a trait rumination measure that captures rumination on problems is in line with recommendations about important directions for rumination research (Smith & Alloy, 2009), allows for a more nuanced understanding of rumination and perhaps co-rumination in terms of their risk for mental health problems, and may better inform clinicians’ preventive and intervention work.

Appendix: Rumination on Problems Questionnaire (RPQ)

Instructions:

“People think and do many different things when they feel down, face challenges, or encounter problems. Please read each of the items below and indicate whether you almost never, sometimes, often, or almost always think or do each one when you feel down, sad, or face challenges or problems. We’re interested in what you generally do, not what you think you should do.”

Item # | Text |

|---|---|

1. | I think about all the things I should’ve done but didn’t. |

2. | I can easily move past negative events. |

3. | Even when I try to let go of past problems, my thoughts about them still persist. |

4. | Even if I realize I may never fully understand why something negative happened, I keep thinking about it over and over again. |

5. | Even if I have already thought about all the details of a problem before, I still think about what went wrong. |

6. | I can’t help but think about the things I’ve done wrong. |

7. | When I have a problem, I think about every single aspect of the problem over and over again. |

8. | When things go wrong, I focus on how I intensified the problem. |

9. | I beat myself up over things I’ve done wrong. |

10. | Once I start thinking about negative things in my life, I get completely sucked in. |

11. | I can’t help but think about things I didn’t do well. |

12. | When I have a problem, I think about all the negative things about me that made things go so badly. |

13. | When I find myself thinking about bad things that have happened, I can easily get my mind off of them and think about other things. |

14. | When I have a problem, it’s hard for me to control my thoughts even when I try to. |

15. | I think over and over again about how bad my situation is. |

16. | I get so wrapped up in thinking about my problems that I don’t even notice what’s going on around me. |

17. | When problems come up, I intentionally replay them in my head. |

18. | It’s easy for me to stop focusing on my problems. |

19. | It’s difficult to do anything else when I start thinking about my problems. |

Response Options:

Text | Value |

|---|---|

Almost never | 1 |

Sometimes | 2 |

Often | 3 |

Almost always | 4 |

Scoring Information:

The RPQ yields one total score, which is a sum of all items. Items 2, 13, and 18 need to be reverse coded prior to scoring.

References

Abbott, M. J., & Rapee, R. M. (2004). Post-event rumination and negative self-appraisal in social phobia before and after treatment. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 113(1), 136. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.113.1.136.

Aldao, A., & Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (2012). When are adaptive strategies most predictive of psychopathology?. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 121(1), 276–281. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0023598

Antony, M. M., Bieling, P. J., Cox, B. J., Enns, M. W., & Swinson, R. P. (1998). Psychometric properties of the 42-item and 21-item versions of the Depression anxiety stress scales in clinical groups and a community sample. Psychological Assessment, 10(2), 176. https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.10.2.176.

Bastin, M., Bijttebier, P., Raes, F., & Vasey, M. W. (2014). Brooding and reflecting in an interpersonal context. Personality and Individual Differences, 63, 100–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2014.01.062.

Bastin, M., Luyckx, K., Raes, F., & Bijttebier, P. (2021). Co-rumination and depressive symptoms in adolescence: Prospective associations and the mediating role of brooding rumination. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 50(5), 1003–1016. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2014.01.062.

Bastin, M., Vanhalst, J., Raes, F., & Bijttebier, P. (2018). Co-brooding and co-reflection as differential predictors of depressive symptoms and friendship quality in adolescents: Investigating the moderating role of gender. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 47(5), 1037–1051. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-017-0746-9.

Bird, T., Tarsia, M., & Schwannauer, M. (2018). Interpersonal styles in major and chronic depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 239, 93–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2018.05.057.

Blackie, R. A., & Kocovski, N. L. (2017). Development and validation of the trait and state versions of the post-event processing inventory. Anxiety Stress & Coping, 30(2), 202–218. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615806.2016.1230668.

Brinker, J. K., & Dozois, D. J. A. (2009). Ruminative thought style and depressed mood. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 65, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20542.

Burwell, R. A., & Shirk, S. R. (2007). Subtypes of rumination in adolescence: Associations between brooding, reflection, depressive symptoms, and coping. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 36(1), 56–65. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374410709336568.

Cann, A., Calhoun, L. G., Tedeschi, R. G., Triplett, K. N., Vishnevsky, T., & Lindstrom, C. M. (2011). Assessing posttraumatic cognitive processes: The event related rumination inventory. Anxiety Stress & Coping, 24(2), 137–156. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615806.2010.529901.

Caselli, G., Ferretti, C., Leoni, M., Rebecchi, D., Rovetto, F., & Spada, M. M. (2010). Rumination as a predictor of drinking behaviour in alcohol abusers: A prospective study. Addiction, 105(6), 1041–1048. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.02912.x.

Center for Collegiate Mental Health (2022, January). 2021 Annual Report (Publication No. STA 22–132). https://ccmh.psu.edu/assets/docs/2021-CCMH-Annual-Report.pdf

Clark, D. M., & Wells, A. (1995). A cognitive model of social phobia. In R. G. Heimberg, M. R. Liebowitz, D. A. Hope, & F. R. Schneier (Eds.), Social phobia: Diagnosis, assessment and treatment (pp. 69–93). Guilford Press.

Cohen, J., Cohen, P., West, S. G., & Aiken (2003). Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Conway, M., Csank, P. A., Holm, S. L., & Blake, C. K. (2000). On assessing individual differences in rumination on sadness. Journal of Personality Assessment, 75(3), 404–425. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327752JPA7503_04

Cox, B. J., Enns, M. W., & Taylor, S. (2001). The effect of rumination as a mediator of elevated anxiety sensitivity in major depression. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 25(5), 525–534. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1005580518671.

Coyne, J. C. (1976). Toward an interactional description of depression. Psychiatry, 39(1), 28–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/00332747.1976.11023874.

Davis, R. N., & Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (2000). Cognitive inflexibility among ruminators and nonruminators. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 24(6), 699–711. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1005591412406.

Edwards, S. L., Rapee, R. M., & Franklin, J. (2003). Postevent rumination and recall bias for a social performance event in high and low socially anxious individuals. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 27(6), 603–617. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1026395526858.

Fehm, L., Hoyer, J., Schneider, G., Lindemann, C., & Klusmann, U. (2008). Assessing post-event processing after social situations: A measure based on the cognitive model for social phobia. Anxiety Stress & Coping, 21(2), 129–142. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615800701424672.

Felton, J. W., Cole, D. A., Havewala, M., Kurdziel, G., & Brown, V. (2019). Talking together, thinking alone: Relations among corumination, peer relationships, and rumination. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 48, 731–743. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-018-0937-z.

Flora, D. B., & Flake, J. K. (2017). The purpose and practice of exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis in psychological research: Decisions for scale development and validation. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science/Revue canadienne des sciences du comportement, 49(2), 78–88. https://doi.org/10.1037/cbs0000069

Fokkema, M., & Greiff, S. (2017). How performing PCA and CFA on the same data equals trouble. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 33(6), 399–402. https://doi.org/10.1027/1015-5759/a000460

Garnefski, N., Kraaij, V., & Spinhoven, P. (2001). Negative life events cognitive emotion regulation and emotional problems. personality and individual differences, 30(8), 1311–1327. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(00)00113-6

Gerbing, D. W., & Anderson, J. C. (1988). An updated paradigm for scale development incorporating unidimensionality and its assessment. Journal of Marketing Research, 25(2), 186–192. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378802500207.

Gillham, J. E., & Chaplin, T. M. (2011). Preventing girls’ depression during the transition to adolescence. In T. J. Strauman, P. R. Costanzo, & J. Garber (Eds.), Preventing depression among adolescent girls: From basic research to effective intervention (pp. 275-317). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Gress-Smith, J. L., Roubinov, D. S., Andreotti, C., Compas, B. E., & Luecken, L. J. (2015). Prevalence, severity and risk factors for depressive symptoms and insomnia in college undergraduates. Stress and Health, 31(1), 63–70. https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.2509.

Hames, J. L., Hagan, C. R., & Joiner, T. E. (2013). Interpersonal processes in depression. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 9(1), 355–377. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050212-185553

Hammen, C. (2005). Stress and depression. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 1, 293–319. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.143938.

Hattie, J. (1985). Methodology review: Assessing unidimensionality of tests and items. Applied Psychological Measurement, 9(2), 139–164. https://doi.org/10.1177/014662168500900204.

Howard, M. C. (2016). A Review of Exploratory Factor Analysis Decisions and Overview of Current Practices: What We Are Doing and How Can We Improve?. International Journal of Human-Computer Interaction, 32(1), 51–62. https://doi.org/10.1080/10447318.2015.1087664

IBM Corp. (2012). Released 2011. IBM SPSS statistics for Windows, Version 21.0. IBM Corp.

John, O. P., Donahue, E. M., & Kentle, R. L. (1991). The big five inventory - versions 4a and 54. University of California, Berkeley, Institute of Personality and Social Research.

Johnson, D. P., & Whisman, M. A. (2013). Gender differences in rumination: A meta-analysis. Personality and Individual Differences, 55(4), 367–374. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2013.03.019.

Johnston, R., Jones, K., & Manley, D. (2018). Confounding and collinearity in regression analysis: A cautionary tale and an alternative procedure, illustrated by studies of British voting behaviour. Quality & Quantity, 52(4), 1957–1976. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-017-0584-6.

Joiner, T. E. Jr. (2002). Depression in its interpersonal context. In I. H. Gotlib, & C. L. Hammen (Eds.), Handbook of depression (pp. 295–313). The Guilford Press.

Joiner, T. E., & Metalsky, G. I. (1995). A prospective test of an integrative interpersonal theory of depression: Anaturalistic study of college roommates. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69(4), 778–788. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.69.4.778

Kim, B. N., & Kang, H. S. (2022). Differential roles of reflection and brooding on the relationship between perceived stress and life satisfaction during the COVID-19 pandemic: A serial mediation study. Personality and Individual Differences, 184, 111169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2021.111169.

Krause, E. D., Vélez, C. E., Woo, R., Hoffmann, B., Freres, D. R., Abenavoli, R. M., & Gillham, J. E. (2018). Rumination, depression, and gender in early adolescence: A longitudinal study of a bidirectional model. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 38(7), 923–946. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272431617704956.

Kyriazos, T. A. (2018). Applied psychometrics: Sample size and sample power considerations in factor analysis (EFA, CFA) and SEM in general. Psychology, 9(08), 2207.

Lipson, S. K., Lattie, E. G., & Eisenberg, D. (2019). Increased rates of mental health service utilization by US college students: 10-year population-level trends (2007–2017). Psychiatric Services, 70(1), 60–63. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201800332.

Lovibond, S. H., & Lovibond, P. F. (1995). Manual for the Depression anxiety stress scales (2nd. ed.). Psychology Foundation.

MacKinnon, D. P., Krull, J. L., & Lockwood, C. M. (2000). Equivalence of the mediation, confounding and suppression effect. Prevention Science, 1(4), 173–181. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1026595011371.

McLaughlin, K. A., & Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (2011). Rumination as a transdiagnostic factor in depression and anxiety. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 49(3), 186–193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2010.12.006.

Mellings, T. M., & Alden, L. E. (2000). Cognitive processes in social anxiety: The effects of self-focus, rumination and anticipatory processing. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 38(3), 243–257. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7967(99)00040-6.

Michl, L. C., McLaughlin, K. A., Shepherd, K., & Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (2013). Rumination as a mechanism linking stressful life events to symptoms of depression and anxiety: Longitudinal evidence in early adolescents and adults. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 122(2), 339–352. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0031994.

Miranda, R., & Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (2007). Brooding and reflection: Rumination predicts suicidal ideation at 1-year follow-up in a community sample. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 45(12), 3088–3095. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2007.07.015.

National Center for Health Statistics (2020–2023). U.S. Census Bureau, Household Pulse Survey, 2020–2023. Anxiety and Depression. Generated interactively from https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/covid19/pulse/mental-health.htm.

Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (1991). Responses to depression and their effects on the duration of depressive episodes. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 100(4), 569–582. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.100.4.569.

Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (2004). The response styles theory. In C. Papageorgiou, & A. Wells (Eds.), Depressive rumination: Nature, theory, and treatment (pp. 107–124). Wiley.

Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (2012). Emotion regulation and psychopathology: The role of gender. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 8, 61–87. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032511-.

Nolen-Hoeksema, S., & Morrow, J. (1991). A prospective study of depression and posttraumatic stress symptoms after a Natural Disaster: The 1989 Loma Prieta Earthquake. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61(1), 115. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.61.1.115.

Nolen-Hoeksema, S., Wisco, B. E., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2008). Rethinking rumination. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 3(5), 400–424. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6924.2008.00088.x.

Nosek, B. A., Alter, G., Banks, G. C., Borsboom, D., Bowman, S. D., Breckler, S. J., & Yarkoni, T. (2015). Promoting an open research culture. Science, 348(6242), 1422–1425. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aab2374.

Olatunji, B. O., Naragon-Gainey, K., & Wolitzky-Taylor, K. B. (2013). Specificity of rumination in anxiety and depression: A multimodal meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 20(3), 225–257. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0101719.

Pedrelli, P., Nyer, M., Yeung, A., Zulauf, C., & Wilens, T. (2015). College students: Mental health problems and treatment considerations. Academic Psychiatry, 39(5), 503–511. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40596-014-0205-9.

Rachman, S., Grüter-Andrew, J., & Shafran, R. (2000). Post-event processing in social anxiety. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 38(6), 611–617. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7967(99)00089-3.

R Core Team (2019). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. https://www.R-project.org/.

Robinson, M. S., & Alloy, L. B. (2003). Negative cognitive styles and stress-reactive rumination interact to predict depression: A prospective study. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 27(3) 275–291. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1023914416469

Rogers, M. L., & Joiner, T. E. (2017). Rumination suicidal ideation and suicide attempts: A meta-analytic review. Review of General Psychology, 21(2), 132–142. https://doi.org/10.1037/gpr0000101

Rood, L., Roelofs, J., Bögels, S. M., Nolen-Hoeksema, S., & Schouten, E. (2009). The influence of emotion-focused rumination and distraction on depressive symptoms in non-clinical youth: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 29(7), 607–616. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2009.07.001.

Rose, A. J. (2002). Co–rumination in the friendships of girls and boys. Child Development, 73(6), 1830–1843. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00509.

Rose, A. J. (2021). The costs and benefits of co-rumination. Child Development Perspectives, 15(3), 176–181. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdep.12419.

Rose, A. J., Carlson, W., & Waller, E. M. (2007). Prospective associations of co-rumination with friendship and emotionaladjustment: considering the socioemotional trade-offs of co-rumination. Developmental Psychology, 43(4), 1019–1031. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.43.4.1019

Rose, A. J., Schwartz-Mette, R. A., Glick, G. C., Smith, R. L., & Luebbe, A. M. (2014). An observational study of co-rumination in adolescent friendships. Developmental Psychology, 50(9), 2199–2209. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0037465.

Ruscio, A. M., Gentes, E. L., Jones, J. D., Hallion, L. S., Coleman, E. S., & Swendsen, J. (2015). Rumination predicts heightened responding to stressful life events in major depressive disorder and generalized anxiety disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 124(1), 17. https://doi.org/10.1037/abn0000025.

Schermelleh-Engel, K., Moosbrugger, H., & Müller, H. (2003). Evaluating the fit of structural equation models: Tests of significance and descriptive goodness-of-fit measures. Methods of Psychological Research Online, 8(2), 23–74.

Simmons, J. P., Nelson, L. D., & Simonsohn, U. (2012, October 14). A 21 Word Solution. SSRN. https://ssrn.com/abstract=2160588 or https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2160588.

Smith, J. M., & Alloy, L. B. (2009). A roadmap to rumination: A review of the definition, assessment, and conceptualization of this multifaceted construct. Clinical Psychology Review, 29(2), 116–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2008.10.003.

Spendelow, J. S., Simonds, L. M., & Avery, R. E. (2017). The relationship between co-rumination andinternalizing problems: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 24(2), 512–527. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.2023

Stevens, J. P. (2012). Applied multivariate statistics for the social sciences. Routledge.

Stone, L. B., & Gibb, B. E. (2015). Brief report: Preliminary evidence that co-rumination fosters adolescents’ depression risk by increasing rumination. Journal of Adolescence, 38(C), 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2014.10.008.

Stone, L. B., Hankin, B. L., Gibb, B. E., & Abela, J. R. (2011). Co-rumination predicts the onset of depressive disorders during adolescence. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 120(3), 752. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0023384.

Trapnell, P. D., & Campbell, J. D. (1999). Private self-consciousness and the five-factor model of personality: Distinguishing rumination from reflection. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 76(2), 284–304. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.76.2.284

Treynor, W., Gonzalez, R., & Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (2003). Rumination reconsidered: A psychometric analysis. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 27(3), 247–259. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1023910315561.

Wade, N. G., Vogel, D. L., Liao, K. Y. H., & Goldman, D. B. (2008). Measuring state-specific rumination: Development of the rumination about an interpersonal offense scale. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 55(3), 419. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.55.3.419.

Waller, E. M., & Rose, A. J. (2013). Brief report: Adolescents’ co-rumination with mothers, co-rumination with friends,and internalizing symptoms. Journal of Adolescence, 36(2), 429–433. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2012.12.006

Watkins, E. R., & Roberts, H. (2020). Reflecting on rumination: Consequences, causes, mechanisms and treatment of rumination. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 127, 103573.

Wolitsky-Taylor, K., Sewart, A., Zinbarg, R., Mineka, S., & Craske, M. G. (2021). Rumination and worry as putative mediators explaining the association between emotional disorders and alcohol use disorder in a longitudinal study. Addictive Behaviors, 119, 106915. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2021.106915

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose. Funding for this project was provided by internal faculty research grants from Swarthmore College and Quinnipiac University. Study approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Boards of Swarthmore College and Quinnipiac University. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants in the study. All authors contributed to the writing of the manuscript. Additional author contributions to this manuscript are as follows: (1) Vélez: Conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, funding acquisition, investigation, methodology, project administration, and supervision. (2) Hoang: Data curation, formal analysis, investigation, and project administration. (3) Krause: Conceptualization. (4) Gillham: Conceptualization, data curation, funding acquisition, investigation, methodology, project administration. Materials, data, and syntax for this study are available by emailing the corresponding author.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Vélez, C.E., Hoang, K.N., Krause, E.D. et al. The Rumination on Problems Questionnaire: Broadening our Understanding of Rumination and its Links to Depression, Anxiety, and Stress in Young Adults. J Psychopathol Behav Assess 46, 191–204 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10862-023-10103-2

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10862-023-10103-2