Abstract

The close contact between patients and community pharmacists, along with the extensive geographical distribution of pharmacies in Portugal, offer exceptional conditions to detect and report adverse drug reactions (ADR). This study aimed to evaluate the motivation and knowledge of spontaneous reporting of ADR by community pharmacists of Porto, Portugal. Secondly, we aimed to generate real-world evidence on the main factors determining ADR report and at raising potential alternatives to the current reporting procedure in community pharmacy. We performed a descriptive, cross-sectional, observational, anonymous web survey-based study. Between April and July 2021, a web survey was implemented, targeting community pharmacists in the Porto district, Portugal. We validated 217 surveys from pharmacists. Regular notifiers seem to be more familiarised than non-regular notifiers with the Portuguese Pharmacovigilance System (PPS), with the Portal RAM for reporting suspected ADR, and with the update of the concept of ADR. Moreover, regular notifiers seem to be more proactive with their care in questioning patients about ADR and have more self-knowledge to identify suspected ADR. Conversely, non-regular notifiers, seem to be more reluctant to be judged by their ADR reporting activities. Respondents suggested to simplify and optimise the reporting process (31% of the suggestions), or to integrate a reporting platform into the pharmacy’s software (27%). This study identified opportunities to promote the ADR reporting process by community pharmacists, namely receiving feedback from the PPS on the reported case and its regulatory implications, implementing training programs in pharmacovigilance, and creating solutions to simplify the reporting process.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Adverse drug reactions (ADR) are a public health problem related to noxious or unintended responses to a medicinal product [1]. Indeed, ADR differs from adverse events since ADR denotes a possible causal relationship between the occurrence and the medicinal product [1,2,3]. ADR contributes to the morbidity and mortality of human populations, responsible for a greater demand for healthcare services and higher health costs [3,4,5,6,7,8].

Pharmacovigilance is a fundamental science in the drug life cycle and comprises a set of activities focused on medicine-related problems [2, 4, 7, 9, 10]. The World Health Organization (WHO) defines pharmacovigilance as “the science and activities relating to the detection, assessment, understanding and prevention of adverse effects or any other possible drug-related problems” [11]. Thus, pharmacovigilance plays a consequential role in the surveillance of ADR, although it is a real challenge for physicians, healthcare providers, the WHO and pharmaceutical industries since. Despite the growth of pharmacovigilance structures worldwide, several studies have estimated reporting rates of around 10%, supporting the already identified problem of underreporting [3, 8, 12,13,14,15,16,17].

Community pharmacists play an important role in drug safety. Given the straight contact between drug consumers and community pharmacists and the extensive geographical distribution of community pharmacies in Portugal, they represent an exceptional place to detect and report ADR. However, there is also evidence of underreporting among pharmacists [4, 8, 18,19,20,21] and, in particular, among community pharmacists [4, 18,19,20].

Some authors have studied the underlying reasons for underreporting among healthcare professionals (HCP), namely among pharmacists [9]. The main contributing factors among HCP seem to be lack of time, uncertainty on drug-event causality, lack of interest, the distance between HCP and patient, and lack of report forms [9, 17]. Other barriers were also identified, such as unawareness of the ADR reporting process and non user-friendly ADR reporting form [22]. Knowledge about pharmacovigilance and the ADR reporting process among HCP still seems to be a very significant barrier, although less among pharmacists compared to physicians and nurses (73.5%, 18.7% and 13.8%, respectively) [23]. Other studies also report that community pharmacists, like general practitioners, have basic knowledge about ADR, although they are unfamiliar with the ADR report guidelines [24, 25]. Despite this, it is also known that both the wrong and the deficient report of ADR can lead to the loss of relevant clinical information, with consequences of different levels, such as health costs [7].

The primary aim of this study was to evaluate the motivation and knowledge of spontaneous reporting of ADR by community pharmacists of Porto, Portugal. Secondly, we aimed to generate real-world evidence on the main factors determining ADR report and at raising potential alternatives to the current reporting procedure in community pharmacy.

Methods

Study Design

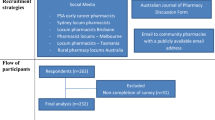

We performed a descriptive, cross-sectional, observational, anonymous web survey-based study. Between April and July 2021, a web survey was implemented, targeting community pharmacists in the Porto district, Portugal (see “study population” section). The GoogleTM® Forms platform was used, since it is an easy-to-use, free and open-source online survey application that enables users to develop and publish online surveys and collect responses without doing any programming. More details are available on the completed Checklist for Reporting Results in Internet E-Surveys (CHERRIES) (Table 1) [26].

The survey was sent by the Portuguese Pharmaceutical Society to the email of each pharmacist, with a reminder every three weeks, totalling eight emails received per pharmacist. Other channels for disseminating the study were also activated, namely medical dissemination platforms that are standard tools for consultation by community pharmacists. Each participant only had the opportunity to answer a single questionnaire during the period considered for data collection.

Study Population

All pharmacists who met the following eligibility criteria were invited to participate in the study: (i) valid enrolment in the Portuguese Pharmaceutical Society and (ii) active professional practice in community pharmacy in the Porto district, Portugal. These eligibility criteria included both community pharmacists who graduated with a 5-year curriculum, resulting in an Integrated Master's degree on Pharmaceutical Sciences and pre-Bologna community pharmacists, who graduated with a 6-year curriculum, resulting in a Graduate’s degree in Pharmaceutical Sciences. Exclusion criteria were not considered. The first two survey questions aimed to ensure that pharmacists who did not meet all inclusion criteria were not admitted to the study.

According to the Portuguese Pharmaceutical Society, the district of Porto (in the Northern region of Portugal) had 1908 community pharmacists with professional activity in this area at the time of data collection for this study.

Development of the Survey Tool

The survey consisted of a questionnaire to assess sociodemographic data, motivation associated with spontaneous reporting of ADR, and knowledge about the Portuguese Pharmacovigilance System (PPS). The following question structure was considered: two questions to ensure compliance with the eligibility criteria; five sociodemographic questions to characterise the population (gender, age, educational level, title of community pharmacy specialist and the number of years of professional experience); four questions about previous habits in spontaneous reporting of ADR; thirty-five Likert scale questions on an agreement of statements about knowledge and motivations (ranged from 1 [“completely disagree”] to 5 [“completely agree”]); eleven Likert scale about measures that may increase spontaneous reporting of ADR (ranged from 1 [“completely disagree”] to 5 [“completely agree”]); and an open-ended question (“If you had the opportunity to make a change to the ADR suspect report process, what would you do?”).

The preliminary survey was developed by a team of pharmacists and physicians based on previous literature on this topic and the team's experience from the Porto Pharmacovigilance Centre, INFARMED, I.P.. The preliminary survey was pre-tested in ten community pharmacists outside the Porto district, with different geographic locations, age, gender, academic studies (pos- and pre-Bologna pharmacists), community pharmacy specialist and years of professional experience (Fig. 1). This pre-test allowed for identifying and correcting any critical issues in the drafting, spelling errors, ordering and structure of the survey. All decisions were made in a consensus meeting by all elements of the research team, with ultimate responsibility for the principal investigator.

Statistical Analysis

For the descriptive analysis, categorical variables were described with frequency and percentage, while the continuous variable was described with mean and standard deviation (SD).

Questions 8 (“Has ever reported an ADR?”) and 9 (“Usually reports ADR?”) were used to stratify users by familiarity on notifying ADR in three levels: “1. Never notified” (Q8 = No), “2. Doesn’t usually notify” (Q8 = Yes, Q9 = No), “3. Usually notifies” (Q8 = Yes, Q9 = Yes). Analysis to questions 1 to 35 was stratified according to these previously described levels, while questions 36 to 46 were analysed without stratification.

Firstly, we applied an analysis of variance combined with principal component analysis (ANOVA–PCA) to evaluate how different these three groups are regarding their answers to the survey. We start by performing a dimensionality reduction with Principal Components Analysis (PCA) and, from here, we perform an Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) to evaluate the differences among the groups. PCA was applied to questions 1 to 35, and ANOVA was applied to the resulting first three principal components, which accounted for 35.7% of the variance of the sample. Assuming only the first three components, ANOVA showed that there were statistically significant differences among the three groups defined initially (p < 0.001) but that the responses between groups “1. Never notified” and “2. Doesn’t usually notify” were similar (p = 0.683) and each different from responses from group “3. Usually notifies” (p < 0.001 in both cases). This suggests that the group of usual notifiers has a different perception of ADR reports than that of none or infrequent notifiers. Based on this, we assumed that it was meaningless to discriminate between groups 1 and 2, and those were then treated as a single group (non-regular notifiers).

For all 35 questions, the median values were presented as a measure of central tendency and the respective interquartile range (IQR) since it was observed that the data did not follow a normal distribution. We compared the response to each question between both groups using the Mann–Whitney U test. The Bonferroni adjustment for multiple comparisons was used for post hoc analysis; p < 0.05 indicated significant differences. The statistical analysis was performed using R version 4.1.0, with package ‘Likert’ version 1.3.5.

Qualitative Analysis

After the analysis of the suggestions for the open question, some key sentences were elaborated in order to be able to group similar suggestions. These sentences were read and grouped independently by two reviewers (R.FdS. and J.M.) and, by final consensus, key sentences were established. All authors reviewed and agreed with all sentences.

Results

Sample Characteristics

From April to July 2021, there were 461 attempts to respond to the survey, but only 220 met the eligibility criteria. Of the 220 surveys collected, only 217 were considered for stratification, given that three respondents did not fit any stratum, as answers to those questions were either missing or set as “Don’t know” (Q8 and Q9), hence being removed in the stratified analysis to subsequent questions.

Considering the population base of this study (n = 1908), the response rate was 11.5%. Of the 220 surveys from pharmacists included, 118 (85.5%) were female and 32 (14.5%) were male, with a mean age of 38.2 ± 9.55 years, as seen in Table 2. Regarding the academic degree, about half of the pharmacists presented an Integrated Master’s degree in Pharmaceutical Sciences (n = 115; 52.3%), and the others presented a Bachelor’s degree in Pharmaceutical Sciences (n = 105; 47.7%). 130 (59%) pharmacists presented a professional experience of 11 years or more, and only 13 (5.91%) of the respondents had less than one year of professional experience. Most respondents were not specialists in community pharmacy (n = 189; 85.9%) to the Portuguese Pharmaceutical Society.

As for reporting suspected ADR, 101 (45.9%) respondents have already reported some, while 117 (53.2%) did not. Regarding the habit of ADR reporting by community pharmacists, 42 (41.6%) said they usually report ADR, against 58 (57.4%) who never reported ADR. Considering the difficulties in reporting suspected ADR, 65 (64.4%) of the inquired consider that they have no difficulties in doing so.

Knowledge and Motivations of Pharmacists

Table 3 shows the degree of agreement for the questions regarding knowledge and motivations of the participants between each group (non-regular notifiers [n = 175] and regular notifiers [n = 42]). All participants in both groups responded to all 35 questions. As can be seen, regular notifiers seem to be more familiar with the PPS (QO1), with the Portal RAM (Q03) as an instrument for reporting suspected ADR, and with the update of the concept of ADR (QO5) than non-regular notifiers. In addition, regular notifiers seem to be more proactive with the care in questioning patients about ADR (Q13) and have more self-knowledge to identify suspected ADR (Q14). Non-regular notifiers, compared to regular notifiers, seem to be more reluctant to be judged by the report of a suspected ADR (Q23).

Among the questions that showed statistically significant differences between the two groups with different reporting habits, we sought to understand the influence of other variables on the knowledge and attitudes of community pharmacists. To a significance level of 0.05, we observed that there is a statistically significant association between the years of professional experience and the answers to Q05 (“I am familiar with the update of the concept of ADR”) (p = 0.008, χ2 = 32.888). Community pharmacists between 4 and 10 years old of professional experience and between 11 and 20 years old of professional experience present lower scores of knowledge about the evolution of the ADR concept than the other three professional experience ranges (27.77% and 27.27% negative answers, respectively, compared to 16.67–21,57% in the remaining professional experience ranges) (Table 4).

Measures that Can Increase the Reporting of Suspected ADR

Figure 2 presents the results related to the questions intended to identify strategies that could encourage or improve the ADR reporting process by community pharmacists. Notably, most pharmacists do not defend the act of reporting as payable to the reporter (Q36). On the other hand, they would be more willing to report ADR if they got feedback from the PPS regarding the assessment of the reported case (Q38) or implications of the ADR and actions taken by regulatory authorities (Q39). The relevance of implementing awareness campaigns for both community pharmacists (Q41) and patients (Q42), as well as training actions by the Portuguese Pharmaceutical Society (Q44), was a point of agreement among the answers. The existence of a mobile/tablet application for ADR reporting (Q40) and the implementation of a tool in the software of community pharmacies for the automatic reporting of ADR to the PPS (Q45) was also a convergence point. Finally, community pharmacists strongly agree with an internal dynamic within pharmacy teams for a more organised reporting of ADR (Q46).

The questionnaire featured an open-ended question which aimed to understand what community pharmacists would change about the process of reporting suspected ADR. The results are shown in Table 5. The most prevalent suggestions were related to simplifying and optimising the reporting process (31% of the suggestions), followed by integrating a spontaneous reporting platform into community pharmacy software (27%). Also, 11% of the suggestions fall on a more significant investment in training in pharmacovigilance and providing feedback to the pharmacist regarding the reported case (10%). The suggestions given by 5% or fewer participants, although not less important, were related to valuing the spontaneous act of ADR reporting as a pharmaceutical act (5%), promoting patient awareness for self-reporting of ADR (4%), promoting multidisciplinarity among the different health professionals (pharmacists, physicians, nurses), users, and the pharmaceutical industry itself in ADR management and follow-up (3%). The informatisation (1%), the development of a hotline for ADR reporting (1%), the payment of the spontaneous report act (1%), and the awareness of the topic among the technical directions of community pharmacies (1%) were other suggestions left by community pharmacists.

Discussion

Our study showed that community pharmacists from Porto, Portugal, are quite active in reporting ADR although there are still some that are not so familiar with the process. Importantly, our study identified pharmacists-raised potential improvements to the current reporting procedure, which can be used to counteract the underreporting seen in the routine activity of our pharmacovigilance centre.

Community pharmacies are the healthcare network with the most significant coverage in Portugal, assuming a central position in managing medication and patients' illnesses. In line with this, community pharmacists are close to patients and are present in their treatment plans since the drug is dispensed and during monitoring [9, 10, 27]. In the United Kingdom, community pharmacists are the second most reporting ADR (19%) after hospital pharmacists (65%), despite 13% of reports did not identify the origin of the pharmaceutical activity [28]. Also, pharmacists have an inherent responsibility to detect and monitor ADR [27], since their wide-ranging education includes areas like clinical pharmacy, pharmacology, pharmacotherapy and toxicology. But, although a retrospective analysis of 20 years of activity of the Porto Pharmacovigilance Centre showed that pharmacists are the seconds that most report among HCP (n = 2,790; 28.7%) [29], underreporting is evident among Portuguese community pharmacists, for whom the number of annual reports per pharmacist is lower than 1% versus 43% in the case of Dutch [30]. In fact, the prevalence of ADR reports from pharmacists is among the highest in Portugal [31, 32]. For that reason, we wanted to characterise the motivation and knowledge of spontaneous reporting of ADR by community pharmacists of Porto, Portugal. Surprisingly, it was clear that community pharmacists from Porto demonstrated a positive attitude towards ADR reporting. Indeed, our results show that about 46% of the community pharmacists surveyed have reported a suspected ADR at least once, and about 42% usually do so. Still, most respondents have never reported suspected ADR (58%), which might contribute to the low reporting rates of ADR described in the literature (around 10%) [3, 8, 12,13,14,15,16,17]. These low ADR reporting rates (14–44%) are consistent among studies conducted across Europe, Asia and Africa [33,34,35,36,37,38]. Spontaneous reporting is a suitable method for early detection of safety problems, providing regulatory authorities with real-world evidence [3,4,5, 7,8,9]. However, the spontaneous nature of this reporting method contributes to underreporting precisely because it is a method that depends on the proactivity of the notifier [39].

The reasons for underreporting are known, but local and national needs are highly conditioned by the characteristics of the pharmacovigilance system implemented and the dynamics established throughout the process. Since 2000 the PPS has been decentralised, reaching the milestone of ten regional units in 2021, which are responsible for all processes associated with the management of ADR reports [9]. PPS is mainly based on spontaneous ADR reports performed by HCP or consumers. In 1976, Inman [40] first proposed a list of "seven deadly sins" as the potential reason of ADR underreporting. However, although later studies were dedicated to the analysis of these relationships [41,42,43,44,45], most studies failed to identify associations or, when identified, only one or two attitudes were associated with underreporting [45,46,47].

Our study is a pioneer since we performed a stratified analysis based on previous habits of reporting suspected ADR, in order to look for differences on subpopulations that could guide future interventions to fight underreporting. Although all respondents recognise the importance of pharmacovigilance and are familiar with the reporting process, pharmacists who have reporting habits are more familiar with the PPS and the Portal RAM, and with the evolution of the RAM concept. In addition, they seem to be more proactive in questioning patients about potential ADR, and refer to have more self-knowledge to identify suspected ADR, probably supporting the data showing that they are less reluctant to be judged by the report of a suspected ADR. Interestingly, these issues were not influenced by either the academic degree, the duration of professional experience, or the title of specialist in community pharmacy, except the familiarity with the update of the concept of ADR, for which recent graduates (less than 4 years of practise) and older pharmacists (more than 20 years of experience) showed higher scores than others. This suggests that continuous education on pharmacovigilance is a valuable tool to improve scientific and technical skills on reporting ADR [35]. In line with this view, it was interesting to note that community pharmacists of our study ranked in third that training in pharmacovigilance would be helpful to promote ADR reporting. This formative strategy also finds support in published literature, with final-year pharmacy students having insufficient knowledge about pharmacovigilance [48, 49] that extends over the years of work, leading to the finding that postgraduate pharmacists show almost the same knowledge of expert pharmacists [9]. A study by Tucklu et al., [36] found that only 17% of the community pharmacists defined the concept of “pharmacovigilance” correctly, and only 26% defined the concept of “ADR” correctly. This might be associated with the undergraduate education curriculum since only about 37% of pharmacy students consider themselves prepared to report ADR in their future professional practice [48], a finding reported in other studies [50]. The association between awareness, knowledge and underreporting may well indicate that providing education and training in pharmacovigilance is essential to improve ADR reporting rate32. Published data also report that when faced with an ADR, professionals show several uncertainties about the type of information they should report and how and to whom they should report [8, 51]. According to Vessal et al. [37], the main reason for non-reporting in a group of community pharmacists who have never reported is the uncertainty of the association of ADR with certain drugs. Thus, the difficulty of detecting ADR could be overcome with new educational approaches such as hands-on involvement with real cases, to place ADR reporting closer to the day-to-day reality of work in community pharmacies.

In the systematic review of Hazell et al., [52], common reasons for not reporting among HCP included lack of time, different care priorities, uncertainty about the drug causing ADR, difficulty accessing forms, lack of awareness of requirements for reporting and lack of understanding of the purpose of spontaneous reporting systems. Some studies reported lack of time as an important reason for failure to report among the pharmacists [21, 53]. Even so, Cavaco et al., [54] concluded that lack of time was not a primary barrier, although it is a variable of a particularly subjective nature because the perception of time is very variable. In our study, participants also referred lack of time as an obstacle to reporting, despite not being a primary barrier, with no statistically significant differences between regular and non-regular notifiers. Moreover, our study showed that both groups have similar attitudes concerning the identification of the drug causing the putative ADR, although non-regular notifiers tend to have a more cautious approach. In addition, the process’s simplicity is widely described in the literature as one of the main factors to report by pharmacists [10, 19].

Community pharmacists in Porto city are, therefore, not different in terms of issues such as time pressure and difficulties in identifying causative drugs [4, 55, 56]. Most pharmacists’ respondents agreed that they would only report ADR if they were sure on the association with a medical drug and that serious ADR are already well described before a drug is put on the market. This evidence has been previously reported in the literature [4, 8, 19]. According to Suyagh et al., [35], only 6% of the pharmacists report serious ADR and prefer to contact the physician or forward the patient to an emergency department. In our study, community pharmacists find it essential to report ADR described in the SmPC, unexpected ADR not described in the SmPC, frequent ADR and non-severe ADR. As such, they find it important to report the severity or frequency of ADR.

The pharmacists in our study state that they frequently report to the medical sales representatives who visit them in pharmacies, agreeing with Toklu et al., [36], in which 46,2% of the respondents inform the medical sales representatives or the drug company verbally. Also, 13% of community pharmacists believed that ADR reporting was primarily the prescriber's responsibility and directed the patient to the prescriber.

In our study, judgment was not a genuine concern among the community pharmacists, mostly among regular notifiers, and participants knew they had deontological and ethical obligations to report suspected ADR. These results are in line with some studies [30, 37] but in opposition with others that undercover the fear of legal liability when reporting ADR [10] or the idea that pharmacists do not have this responsibility [38], which is quite worrying.

We also aimed at raising potential alternatives to the current reporting procedure in community pharmacy. One of the measures to increase reporting seems to be the payment of ADR reporting, although not supported by most respondents. This measure had already been evaluated previously by Herdeiro et al., [4] and Hughes et al., [28], with results agreeing with ours. This was also highlighted during the structured face-to-face interview study[18] with United Kingdom community pharmacists in the late 1990s, with 37% of respondents believing a fee would increase reporting rates. Although the reasons that led many pharmacists to want to be paid have not been studied, this may reflect their point of view based on the time they spend and the work involved with this task [28]. From a deontological point of view, it can be questionable since Portuguese law states that health professionals communicate “as quickly as possible (…) the ADR and serious or unexpected ADR suspicions of which they are aware resulting from the use of medicines” [57].

Porto community pharmacists showed more willingness to report ADR if there were more campaigns related to medicines safety aimed at both HCP and users and the development of educational material for pharmacies and training accredited by the Portuguese Pharmaceutical Society. According to Tocklu et al., [36], pharmacists enrolled on a pharmacovigilance course had more knowledge about this theme. Granas et al., [51] evaluated the impact that educational programmes in pharmacovigilance had on a group of community pharmacists. It was possible to see that it positively impacted their adopted position after the training. So, this could be an option to increase the community pharmacists’ knowledge and enrol them in this subject.

Some of the suggested measures are consistent with the evidence published in several studies [9, 58,59,60]. Perhaps it makes sense to think of joint solutions between the PPS and the technology supply companies of pharmacies, developing new digital tools to report directly through the pharmacy’s internal software. Developing an app for ADR reporting is also not an innovative idea [61], as is the example of VigiBIP® developed by the Toulouse University Pharmacovigilance Centre [62]. VigiBIP® is a free smartphone app available on Android and Apple stores to report ADR and request drug safety information. Also, an app developed for two-way risk communication—may reduce the time between experiencing and reporting an ADR and lead to more informed patients and HCP. The Web-RADR project [63] is an example of this and aims to improve traditional pharmacovigilance activities by using new tools to identify potential new ADR earlier and improve drug safety communication (mobile app).

HCP such as physicians, nurses and pharmacists should be considered players in improving the outcome of the pharmacologic therapeutic plans. The professionals who have pharmacotherapeutic and pharmacology knowledge are essential to obtaining ADR reports of higher quality [36]. Pharmacists must be more involved in the reporting process, and regulatory authorities need to encourage pharmacists to be an active part of the system. This idea was emphasised in the answers in the sense that pharmacists consider that there should be feedback from the PPS regarding the assessment of the reported case and the implications and measures taken by the regulatory authorities themselves. While PPS feedback on reported cases has been a reality for many years, there is an identified need to make the reporter’s response more targeted and personalised. However, the Portal RAM back office is not yet fully user-friendly in automatically generating feedback based on case data. Lastly, community pharmacy teams should have well-established ADR reporting dynamics, which is only achieved after proper training of employees and optimisation of the process.

In line with the “Knowledge-Attitude-Practice (KAP) model” as the theoretical underpinning for developing the hypothesised relationships [64] and previous studies, we suggest that modifying some attitudes and knowledge should improve the participation of community pharmacists in the spontaneous reporting system.

Weaknesses and Strengths

Compared with other studies, one strength of our study is its comprehensiveness in relating global scope and the topics covered. Moreover, our study includes a set of suggestions to reverse underreporting, constituting a strong contribution to the implementation of new national policies supported by the Portuguese Pharmaceutical Society. Finally, it is a pioneer in analysing subgroups based on the reporting habits of suspected ADR. No study was identified in the literature that performed this analysis based on this variable.

However, this study also has some limitations. The methodology used for disseminating the survey focused on intercepting the target audience (i.e., those who meet the eligibility criteria), but many surveys were eliminated for not meeting the eligibility criteria (n = 240). This might have resulted from a “snowball” phenomenon generated by forwarding the invitation to participate among pharmacists outside the target population. The identification and consequent exclusion of some of these surveys of respondents outside the target population will have minimised the impact of this bias. Also, the fact that the survey was done online did not allow the researchers to confirm the veracity of the answers, namely the eligibility criteria. Although we are dealing with an instructed population, and the answers to this survey do not impact their personal or professional activity, the response bias associated with self-report must be considered when interpreting the results. Finally, the low response rate (11.5%) may limit the representativeness of the population and, consequently, the results obtained. However, this response rate is similar among surveys of pharmacists regarding ADR [37, 55, 65], and the sample included active community pharmacists with different sociodemographic characteristics, thus presenting very different points of view.

Conclusion

This study identified some opportunities to promote the ADR reporting process by community pharmacists, namely receiving feedback from the PPS on the reported case and its putative regulatory implications, implementing training programs in pharmacovigilance, and creating solutions to simplify the reporting process.

Data Availability

Not applicable.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

References

European Medicines Agency (2017). Guideline on Good Pharmacovigilance Practices (GVP): Annex I - Definitions. Available on: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/scientific-guideline/guideline-good-pharmacovigilance-practices-annex-i-definitions-rev-4_en.pdf.

Matos, C., Rodrigues, L., & Joaquim, J. (2017). Attitudes and opinions of Portuguese community pharmacy professionals towards patient reporting of adverse drug reactions and the pharmacovigilance system. Drugs & Therapy Perspectives, 33(4), 188.

dos Santos Pernas, S. I., Herdeiro, M. T., Lopez-Gonzalez, E., da Cruz e Silva, O. A. B., & Figueiras, A. (2012). Attitudes of Portuguese health professionals toward adverse drug reaction reporting. International Journal of Clinical Pharmacy, 34(5), 693–698. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-012-9675-6

Herdeiro, M. T., Figueiras, A., Polonia, J., & Gestal-Otero, J. J. (2006). Influence of pharmacists’ attitudes on adverse drug reaction reporting : A case-control study in Portugal. Drug Safety, 29(4), 331–340. https://doi.org/10.2165/00002018-200629040-00004

Lopez-Gonzalez, E., Herdeiro, M. T., & Figueiras, A. (2009). Determinants of under-reporting of adverse drug reactions. Drug Safety, 32(1), 19–31. https://doi.org/10.2165/00002018-200932010-00002

Mendes Marques, J. I. O., Polónia, J. M. J., Figueiras, A. G., Costa Santos, C. M. N., & Herdeiro, M. T. F. (2016). Nurses’ attitudes and spontaneous adverse drug reaction reporting: A case–control study in Portugal. Journal of nursing management, 24(3), 409–416.

Potlog Shchory, M., Goldstein, L. H., Arcavi, L., Shihmanter, R., Berkovitch, M., & Levy, A. (2020). Increasing adverse drug reaction reporting-How can we do better? PLoS ONE, 15(8), e0235591. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0235591

Green, C. F., Mottram, D. R., Rowe, P. H., & Pirmohamed, M. (2001). Attitudes and knowledge of hospital pharmacists to adverse drug reaction reporting. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, 51(1), 81–86. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2125.2001.01306.x

Duarte, M., Ferreira, P., Soares, M., Cavaco, A., & Martins, A. P. (2015). Community pharmacists’ attitudes towards adverse drug reaction reporting and their knowledge of the new pharmacovigilance legislation in the southern region of Portugal: A mixed methods study. Drugs & Therapy Perspectives, 31(9), 316–322. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40267-015-0227-8

Li, R., Curtain, C., Bereznicki, L., & Zaidi, S. T. R. (2018). Community pharmacists’ knowledge and perspectives of reporting adverse drug reactions in Australia: A cross-sectional survey. International Journal of Clinical Pharmacy, 40(4), 878–889. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-018-0700-2

Organisation WH: The importance of pharmacovigilance: safety Monitoring of medicinal products. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/10665-42493 (2002). Accessed.

Pirmohamed, M., Breckenridge, A. M., Kitteringham, N. R., & Park, B. K. (1998). Adverse drug reactions. BMJ, 316(7140), 1295–1298. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.316.7140.1295

Smith, C. C., Bennett, P. M., Pearce, H. M., Harrison, P. I., Reynolds, D. J., Aronson, J. K., et al. (1996). Adverse drug reactions in a hospital general medical unit meriting notification to the Committee on Safety of Medicines. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, 42(4), 423–429. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2125.1996.04376.x

Rawlins, M. D. (1995). Pharmacovigilance: Paradise lost, regained or postponed? The William Withering Lecture 1994. Journal of the Royal College of Physicians of London, 29(1), 41–49.

Rawlins, M. D. (1988). Spontaneous reporting of adverse drug reactions. I: the data. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, 26(1), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2125.1988.tb03356.x

Ibanez, L., Laporte, J. R., & Carne, X. (1991). Adverse drug reactions leading to hospital admission. Drug Safety, 6(6), 450–459. https://doi.org/10.2165/00002018-199106060-00005

Herdeiro, M. T., Figueiras, A., Polonia, J., & Gestal-Otero, J. J. (2005). Physicians’ attitudes and adverse drug reaction reporting : A case-control study in Portugal. Drug Safety, 28(9), 825–833. https://doi.org/10.2165/00002018-200528090-00007

Green, C. F., Mottram, D. R., Raval, D., Proudlove, C., & Randall, C. (2011). Community pharmacists’ attitudes to adverse drug reaction reporting. International Journal of Pharmacy Practice, 7(2), 92–99. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2042-7174.1999.tb00955.x

Generali, J. A., Danish, M. A., & Rosenbaum, S. E. (1995). Knowledge of and attitudes about adverse drug reaction reporting among Rhode Island pharmacists. Annals of Pharmacotherapy, 29(4), 365–369. https://doi.org/10.1177/106002809502900404

Yousuf, S. A., Alshakka, M., Badulla, W. F. S., Ali, H. S., Shankar, P. R., & Mohamed Ibrahim, M. I. (2019). Attitudes and practices of community pharmacists and barriers to their participation in public health activities in Yemen: Mind the gap. BMC Health Services Research, 19(1), 304. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-019-4133-y

Sweis, D., & Wong, I. C. (2000). A survey on factors that could affect adverse drug reaction reporting according to hospital pharmacists in Great Britain. Drug Safety, 23(2), 165–172. https://doi.org/10.2165/00002018-200023020-00006

Kitisopee, T., Assanee, J., Sorofman, B. A., & Watcharadmrongkun, S. (2022). Consumers’ adverse drug event reporting via community pharmacists: Three stakeholder perception. Journal of Pharmaceutical Policy and Practice, 15(1), 19. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40545-022-00417-z

Sharif, M. J. H., Farrukh, M. J., Khan, F. U., Khan, Q., Ahmed, S. S., Kousar, R., et al. (2022). Exploring the factors and barriers of healthcare professionals in tertiary care hospitals toward pharmacovigilance: A multicenter study from Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Pakistan. Current Medical Research and Opinion, 38(4), 595–605. https://doi.org/10.1080/03007995.2022.2042992

Li, R., Curtain, C., Bereznicki, L., & Zaidi, S. T. R. (2018). Community pharmacists’ knowledge and perspectives of reporting adverse drug reactions in Australia: A cross-sectional survey. International Journal of Clinical Pharmacy, 40(4), 878–889. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-018-0700-2

Valinciute-Jankauskiene, A., & Kubiliene, L. (2021). Qualitative Study of Community Pharmacists’ and General Practitioners’ Views toward Pharmacovigilance in Lithuania. Healthcare, 9(8), 1072.

Eysenbach, G. (2004). Improving the quality of Web surveys: The checklist for reporting results of internet E-surveys (CHERRIES). Journal of Medical Internet Research, 6(3), e34. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.6.3.e34

De Meestere, D., & Saevels, J. (2019). Belgian community pharmacists’ pharmacovigilance perspective and practice. Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy., 15(12), 1446–1452. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sapharm.2019.01.007

Hughes, M. L., & Weiss, M. (2019). Adverse drug reaction reporting by community pharmacists—the barriers and facilitators. Pharmacoepidemiology and drug safety., 28(12), 1552–1559.

Ferreira-da-Silva, R., Ribeiro-Vaz, I., Silva, A. M., Marques, J., & Polonia, J. J. (2021). Looking back on 20 years of work at the Porto Pharmacovigilance Centre, Portugal. Cadernos de Saúde Pública, 37(10), e00304420. https://doi.org/10.1590/0102-311X00304420

Grootheest ACV. (2003). Improving pharmacovigilance and the role of the pharmacist. Groningen: s.n., (pp. 230).

Infarmed – National Authority of Medicines and Health Products IP: Notificação de reações adversas a medicamentos - Desempenho do Sistema Nacional de Farmacovigilância. https://www.infarmed.pt/web/infarmed/entidades/medicamentos-uso-humano/farmacovigilancia/desempenho-do-snf (2022). Accessed 30 May 2022.

Renato Ferreira-da-Silva, I.R.-V., Silva, A. M., Marques, J., & Polónia, J. J. (2021). Retrospectiva de 20 anos de atividade da Unidade de Farmacovigilância do Porto Portugal. Cadernos de Saúde Pública. https://doi.org/10.1590/0102-311X00304420

Xu, H., Wang, Y., & Liu, N. (2009). A hospital-based survey of healthcare professionals in the awareness of pharmacovigilance. Pharmacoepidemiology and Drug Safety, 18(7), 624–630. https://doi.org/10.1002/pds.1752

Su, C., Ji, H., & Su, Y. (2010). Hospital pharmacists’ knowledge and opinions regarding adverse drug reaction reporting in Northern China. Pharmacoepidemiology and Drug Safety, 19(3), 217–222. https://doi.org/10.1002/pds.1792

Suyagh, M., Farah, D., & Abu, F. R. (2015). Pharmacist’s knowledge, practice and attitudes toward pharmacovigilance and adverse drug reactions reporting process. Saudi Pharm J, 23(2), 147–153. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsps.2014.07.001

Toklu, H. Z., & Uysal, M. K. (2008). The knowledge and attitude of the Turkish community pharmacists toward pharmacovigilance in the Kadikoy district of Istanbul. Pharmacy World & Science, 30(5), 556–562. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-008-9209-4

Vessal, G., Mardani, Z., & Mollai, M. (2009). Knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions of pharmacists to adverse drug reaction reporting in Iran. Pharmacy World & Science, 31(2), 183–187. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-008-9276-6

Mahmoud, M. A., Alsowaida, Y., Alshammari, T., Khan, T. M., Alrasheedy, A., Hassali, M. A., et al. (2014). Community pharmacists’ knowledge, behaviors and experiences about adverse drug reaction reporting in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Pharm J, 22(5), 411–418. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsps.2013.07.005

Organization WH: Safety Monitoring of Medicinal Products: Guidelines for setting up and running a pharmacovigilance centre 2000—section 5.3 under-reporting. https://digicollections.net/medicinedocs/#p/home (2020). Accessed 20 Jan 2022.

Inman, W. (1976). Assessment drug safety problems. Epidemiological issues in reported drug-induced illnesses (pp. 17–24). McMaster University Library Press Honolulu.

Rogers, A. S., Israel, E., Smith, C. R., Levine, D., McBean, A. M., Valente, C., et al. (1988). Physician knowledge, attitudes, and behavior related to reporting adverse drug events. Archives of Internal Medicine, 148(7), 1596–1600.

Figueiras, A., Tato, F., Fontaiñas, J., & Gestal-Otero, J. J. (1999). Influence of physicians’ attitudes on reporting adverse drug events: A case-control study. Medical Care, 37(8), 809–814. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005650-199908000-00010

Eland, I. A., Belton, K. J., van Grootheest, A. C., Meiners, A. P., Rawlins, M. D., & Stricker, B. H. (1999). Attitudinal survey of voluntary reporting of adverse drug reactions. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, 48(4), 623–627. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2125.1999.00060.x

Bateman, D. N., Sanders, G. L., & Rawlins, M. D. (1992). Attitudes to adverse drug reaction reporting in the Northern Region. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, 34(5), 421–426.

Belton, K. J., Lewis, S. C., Payne, S., Rawlins, M. D., & Wood, S. M. (1995). Attitudinal survey of adverse drug reaction reporting by medical practitioners in the United Kingdom. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, 39(3), 223–226. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2125.1995.tb04440.x

Bäckström, M., Mjörndal, T., Dahlqvist, R., & Nordkvist-Olsson, T. (2000). Attitudes to reporting adverse drug reactions in northern Sweden. European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, 56(9), 729–732. https://doi.org/10.1007/s002280000202

McGettigan, P., Golden, J., Conroy, R. M., Arthur, N., & Feely, J. (1997). Reporting of adverse drug reactions by hospital doctors and the response to intervention. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, 44(1), 98–100. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2125.1997.00616.x

Elkalmi, R. M., Hassali, M. A., Ibrahim, M. I., Widodo, R. T., Efan, Q. M., & Hadi, M. A. (2011). Pharmacy students’ knowledge and perceptions about pharmacovigilance in Malaysian public universities. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 75(5), 96. https://doi.org/10.5688/ajpe75596

Smith, M. P., & Webley, S. D. (2013). Pharmacovigilance teaching in UK undergraduate pharmacy programmes. Pharmacoepidemiology and Drug Safety, 22(3), 223–228. https://doi.org/10.1002/pds.3311

Medeiros, J. C., Ferreira, S. C., & Paixão, MNd. J. (2017). Knowledge about adverse drug reaction between pharmacy and nursing students. Revista de Pesquisa em Saúde, 18(1), 13–17.

Granas, A. G., Buajordet, M., Stenberg-Nilsen, H., Harg, P., & Horn, A. M. (2007). Pharmacists’ attitudes towards the reporting of suspected adverse drug reactions in Norway. Pharmacoepidemiology and Drug Safety, 16(4), 429–434. https://doi.org/10.1002/pds.1298

Hazell, L., & Shakir, S. A. (2006). Under-reporting of adverse drug reactions : A systematic review. Drug Safety, 29(5), 385–396. https://doi.org/10.2165/00002018-200629050-00003

Green, C. F., Mottram, D. R., Rowe, P. H., & Brown, A. M. (1997). An investigation into adverse drug reaction monitoring by United Kingdom hospital pharmacy departments. International Journal of Pharmacy Practice, 5, 202–208.

Cavaco, A. M., & Krookas, A. A. (2014). Community pharmacies automation: Any impact on counselling duration and job satisfaction? International Journal of Clinical Pharmacy, 36(2), 325–335. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-013-9882-9

Rouleau, B., Lavoie, L., Leblanc, J., Moretti, S., & Collin, C. (2011). Reporting of adverse drug reactions by community pharmacists: A qualitative study in quebec. Drug Information Journal., 45, 627–639.

Irujo, M., Beitia, G., Bes-Rastrollo, M., Figueiras, A., Hernández-Díaz, S., & Lasheras, B. (2007). Factors that influence under-reporting of suspected adverse drug reactions among community pharmacists in a Spanish region. Drug Safety, 30(11), 1073–1082. https://doi.org/10.2165/00002018-200730110-00006

República Dd: Decreto-Lei n.º 176/2006 - Regime jurídico dos medicamentos de uso humano. https://dre.pt/dre/detalhe/decreto-lei/176-2006-540387 Accessed.

Tabali, M., Jeschke, E., Bockelbrink, A., Witt, C. M., Willich, S. N., Ostermann, T., et al. (2009). Educational intervention to improve physician reporting of adverse drug reactions (ADRs) in a primary care setting in complementary and alternative medicine. BMC Public Health, 9, 274. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-9-274

Parrella, A., Braunack-Mayer, A., Gold, M., Marshall, H., & Baghurst, P. (2013). Healthcare providers’ knowledge, experience and challenges of reporting adverse events following immunisation: A qualitative study. BMC Health Services Research, 13, 313. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-13-313

Khalili, H., Mohebbi, N., Hendoiee, N., Keshtkar, A. A., & Dashti-Khavidaki, S. (2012). Improvement of knowledge, attitude and perception of healthcare workers about ADR, a pre- and post-clinical pharmacists’ interventional study. British Medical Journal Open, 2(1), e000367. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000367

de Vries, S. T., Wong, L., Sutcliffe, A., Houyez, F., Ruiz, C. L., Mol, P. G., et al. (2017). Factors influencing the use of a mobile app for reporting adverse drug reactions and receiving safety Information: A qualitative study. Drug Safety, 40(5), 443–455. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40264-016-0494-x

Montastruc, F., Bagheri, H., Lacroix, I., Damase-Michel, C., Chebane, L., Rousseau, V., et al. (2018). Adverse drug reaction reports received through the mobile app, VigiBIP((R)): A comparison with classical methods of reporting. Drug Safety, 41(5), 511–514. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40264-017-0630-2

Ghosh, R., & Lewis, D. (2015). Aims and approaches of Web-RADR: A consortium ensuring reliable ADR reporting via mobile devices and new insights from social media. Expert Opinion on Drug Safety, 14(12), 1845–1853. https://doi.org/10.1517/14740338.2015.1096342

Herdeiro, M. T., Polónia, J., Gestal-Otero, J. J., & Figueiras, A. (2004). Factors that influence spontaneous reporting of adverse drug reactions: A model centralized in the medical professional. Journal of evaluation in clinical practice, 10(4), 483–489.

Prakasam, A., Nidamanuri, A., & Kumar, S. (2012). Knowledge, perception and practice of pharmacovigilance among community pharmacists in South India. Pharmacy Practice (Granada), 10, 222–226.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the collaboration of the ten Portuguese community pharmacists who cooperated in the pre-test phase, contributing to the improvement of the final version of the survey: Ema Paulino, Natacha Vilanova, José Carlos Maduro, Bruno Guerreiro, Sandra Magro, Joana Oliveira, Diana Lia, José Pais, Flávio Correia and Marisa Botelho. However, the content of the final survey reflects consensus from members of the research team, who have full editorial control. The authors are also grateful the Portuguese Pharmaceutical Society, and the media partners Netfarma and News Farma for disseminating the survey among the eligible population.

Funding

This manuscript was supported by the PhD scholarship 2020.10231.BD (DOCTORATES 4 COVID-19), funded by Portuguese national funds and Community funds from the European Social Fund (ESF) through FCT – Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia (Portugal). The Porto Pharmacovigilance Centre is a regional centre of the Portuguese Pharmacovigilance System, funded by INFARMED, I.P., as the National Authority for Medicines and Health Products of Portugal.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualisation, RFdS and IRV; Methodology, RFdS and IRV; Data Curation and Validation: RFdS, JMA, CV, AMS, JM, JJP and IRV; Formal Analysis, JMA; Writing-Original Draft Preparation, RFdS and CV; Writing-Review & Editing, AMS, JM, MM, JJP and IRV; Review and Approval, all authors. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures followed the ethical standards of the ethics committee of the Centro Hospitalar e Universitário de São João and the Helsinki Declaration of 1964 and its later amendments. This ethics committee approved the study (CE-82-21).

Consent to Participate

Informed consent was obtained from the participants for being included in the study.

Consent for Publication

Informed consent was obtained from the participants to publish data in an aggregated form under scientific publication.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Ferreira-da-Silva, R., Alves, J.M., Vieira, C. et al. Motivation and Knowledge of Portuguese Community Pharmacists Towards the Reporting of Suspected Adverse Reactions to Medicines: A Cross-Sectional Survey. J Community Health 48, 295–308 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-022-01168-3

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-022-01168-3