Abstract

The present study investigated self-reported impulsivity in gambling disorder (GD) and bipolar disorder (BD). Participants with GD (n = 31), BD (n = 19), and community controls (n = 68) completed diagnostic interviews and symptom severity and functioning assessments. Participants also completed the UPPS-P Impulsive Behavior Scale composed of five dimensions including urgency (i.e., acting rashly under conditions of negative or positive emotion), lack of perseverance (i.e., inability to maintain focus), lack of premeditation (i.e., inability to consider negative consequences), and sensation seeking (i.e., tendency to pursue novel and exciting activities). Multivariate analysis of variance showed overall significant differences among the diagnostic groups on the UPPS-P subscales. Follow-up analyses of variance showed that the groups differed on all subscales except sensation seeking. The gambling and bipolar groups had significantly higher levels of self-reported impulsivity on all subscales when compared to controls. In addition, the BD group showed higher levels of positive urgency when compared to the GD group. Positive and negative urgency showed the strongest association with GD and BD. Impaired emotion regulation mechanisms may underlie self-reported impulsivity in both disorders. Lack of premeditation and perseverance may be related to dysfunctional cognitive processes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Impulsivity is a central feature of both gambling disorder and bipolar disorder (Hodgins and Holub 2015; Najt et al. 2007). Investigating the traits that underlie impulsivity in gambling disorder and bipolar disorder can enhance our understanding of dimensions and potentially transdiagnostic mechanisms underlying these two conditions. However, there is little agreement on what the construct impulsivity actually represents (Evenden 1999). Behavioral tasks that measure impulsivity follow one of three broad conceptualizations (from Moeller et al. 2001). Extinction paradigms define impulsivity as the perseverance of an unrewarded (or punished) response, reward-choice paradigms define impulsivity as the preference for a small immediate reward over a larger delayed reward, and response disinhibition paradigms define impulsivity as the inability to withhold a premature response. Each of these paradigms measure one aspect of impulsivity, but fail to capture others. Self-report measures, unlike behavioral tasks, have the added advantage of being able to assess multiple facets of impulsivity simultaneously. To this end, Whiteside and Lynam (2001) conducted a factor analysis on data from several self-reported impulsivity measures, as well as the Revised NEO Personality Inventory (Costa and McCrae 1992). The result was the creation of a multifactorial measure of impulsivity, the UPPS-P (Lynam et al. 2006). According to this model, impulsivity is composed of five different dimensions:

-

1.

Positive urgency—the tendency to act rashly under conditions of positive emotion

-

2.

Negative urgency—the tendency to act rashly under conditions of negative emotion

-

3.

Lack of perseverance—the inability to remain focused on a task that is boring or difficult

-

4.

Lack of premeditation—the inability to consider negative consequences before engaging in an action

-

5.

Sensation seeking—the tendency to pursue novel and exciting activities which may or may not be hazardous

The current investigation aimed to explore the facets of self-reported impulsivity in gambling disorder and bipolar disorder using the five factor model of the UPPS-P.

Impulsivity in Gambling Disorder

Gambling disorder is characterized by persistent gambling behavior accompanied by addictive features like salience, tolerance, and withdrawal (APA 2013). Although impulsivity is not specified in the diagnostic criteria, impulsivity is one of the strongest etiological contributors to pathological gambling (MacKillop et al. 2014). Several studies have looked at impulsivity in gambling disorder. Michalczuk et al. (2011) reported that pathological gamblers have higher levels of positive and negative urgency, and the authors suggested that an impulsive decision-making style may affect cognitive functions by, for instance, increasing the acceptance of erroneous beliefs about gambling. Other studies using behavioral measures have found that impulsivity on tasks like delayed discounting is associated with problem gambling (Alessi and Petry 2003).

Impulsivity has been associated with the presence and severity of problematic gambling behavior (Krueger et al. 2005; Steel and Blaszczynski 1998). Even in healthy populations, impulsivity may serve as a predictor of future gambling problems. A longitudinal study (Cyders and Smith 2008a) of 418 college students showed that positive urgency predicted longitudinal increases in frequency of gambling behaviors like participation in horse racing, casinos, etc., while sensation seeking predicted increases in frequency of general risky behaviors like mountain climbing, scuba diving, etc. An even larger study of 1004 males found that impulsivity at age 14 was associated with both depression and gambling problems at age 17 (Dussault et al. 2011; see Vitaro et al. 1999).

Impulsivity in Bipolar Disorder

Impulsivity is a core feature of manic and hypomanic episodes, and therefore it is virtually impossible to meet criteria for bipolar disorder without impulsivity. However, impulsivity in bipolar disorder has not been investigated as thoroughly as in gambling research. Current evidence suggests that impulsivity is pervasive in bipolar mania (Swann et al. 2001b) and depression (Swann et al. 2008), as well as being associated with risk of illness onset (Alloy et al. 2008; Kwapil et al. 2000) and a more severe course of illness (Swann et al. 2009a, b). Impulsivity in bipolar disorder is related to increased risk for suicides (Swann et al. 2005) and substance abuse (Swann et al. 2004). Impulsivity has even been found to be elevated in bipolar patients who are not actively symptomatic, indicating that impulsivity has both state and trait-dependent components (Najt et al. 2007; Swann et al. 2003, but see Lewis et al. 2009). However, we do not know whether inter-episode impulsivity should be considered a risk factor, or a consequence, of multiple episodes (Moeller et al. 2001).

Impulsivity in Gambling and Bipolar Disorder

Gambling and bipolar disorders can both be conceptualized, at least in part, as disorders of impulsivity. Of note, studies have found a higher prevalence of disordered gambling in bipolar disorder patients (Kennedy et al. 2010; McIntyre et al. 2007), as well as a higher prevalence of bipolar disorder in problem gamblers (Kim et al. 2006; Lorains et al. 2011). No studies have directly compared patterns of self-reported impulsivity between gambling and bipolar disorders.

Hypotheses

We hypothesized that gambling disorder and bipolar disorder would be associated with higher levels of self-reported impulsivity when compared to community controls. We further explored commonalities and differences between gambling disorder and bipolar disorder.

Methods

Participants

The sample consisted of gambling disorder participants (GD) (n = 31), bipolar disorder patients (BD) (n = 19), and community controls (n = 68) (Table 1). All participants were recruited from the community through media announcements, notices at treatment agencies, existing registry of individuals interested in research, and through word-of mouth. Bipolar disorder patients were additionally recruited from the Mood Disorders Clinic at Foothills Medical Center. Potential participants completed a screening phone interview to determine eligibility for the study. The participants were recruited from two different projects. As it had been decided a priori to combine data from both projects, all participants were assessed for psychosis, mood disorders, gambling disorder, and family history of gambling and/or mood disorders. Inclusion criteria for gambling disorder included the presence of lifetime gambling disorder, and absence of bipolar disorder or psychosis. Inclusion criteria for bipolar disorder included a lifetime diagnosis of bipolar disorder and absence of gambling disorder. For all groups (including controls), participants were excluded if their age was less than 18, IQ was less than 80, or they suffered from neurological or other conditions that could affect cognitive functioning (e.g., epilepsy, stroke, multiple sclerosis, AIDS, traumatic brain injury). Participants were excluded if they suffered from any medical conditions that made it impossible to participate in the study (chronic pain, blindness, etc.). All but one bipolar disorder participant were on medications (Table 1) and 13 (41.9%) gambling disorder participants reported seeking professional help or attending self-help groups.

Procedure

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. All data for the current analysis were collected over two sessions. A trained investigator conducted the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 disorders (SCID-5). The Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) and Problem Gambling Severity Index (PGSI) scales were used to collect data on gambling symptoms. All diagnoses and Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale (SOFAS) ratings were made by consensus after case discussions, which were attended by one or both principal investigators (V.M.G and D.C.H).

Measures

Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 The SCID-5 (First et al. 2015) is a diagnostic interview administered by a trained professional to arrive at Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5; APA 2013) diagnoses. All participants were administered the modules for mood disorders, psychotic disorders, substance use disorders, and anxiety disorders. In addition, the gambling study participants were administered the modules on eating disorders, ADHD, OCD, and trauma and stress-related disorders.

Composite International Diagnostic Interview The CIDI semi-structured interview was used to diagnose gambling disorder. The CIDI collects information about the symptoms of gambling disorder, as well as the frequency and severity of gambling behavior. The CIDI is based on the diagnostic criteria outlined in the 4th edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Kessler et al. 2008; Kessler and Üstün 2004). Therefore, information from the CIDI was used in conjunction with the DSM-5 criteria to determine the diagnosis. The interview was modified slightly to determine whether the participant also met criteria for current gambling disorder (Table 2).

Problem Gambling Severity Index The PGSI (Ferris and Wynne 2001) is a 9-item Likert scale used to assess problem gambling severity in the past 12 months. A score of 8 or more indicates severe problem gambling with negative consequences and possible loss of control (Currie et al. 2013). The PGSI was used along with the CIDI to determine the presence and severity of current gambling disorder.

Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale The SOFAS (Morosini et al. 2000) provides a measure of the participant’s social and occupational functioning on a scale of 0–100, where lower scores represent worse functioning. SOFAS rating for each participant was made by consensus of all interviewers and at least one of the principal investigators.

Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAMD) The HAMD (Hamilton 1960) is a 17-item scale used to assess symptoms of depression including changes in mood, appetite, sleep patterns, and suicidality.

Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS) The YMRS (Young et al. 1978) is a 11-item scale used to assess symptoms of mania including changes in mood, psychomotor activity, sleep, and sexual functioning.

UPPS Impulsive Behavior Scale (UPPS-P) The UPPS-P (Whiteside and Lynam 2001) is a 59-item self-report questionnaire designed to measure five facets of impulsive behaviors:

-

Positive urgency (e.g., ‘When overjoyed, I feel like I can’t stop myself from going overboard’)

-

Negative urgency (e.g., ‘Sometimes when I feel bad, I can’t seem to stop what I am doing even though it is making me feel worse’)

-

Lack of perseverance (e.g., ‘I finish what I start’)

-

Lack of premeditation (e.g., ‘I usually make up my mind through careful reasoning’)

-

Sensation seeking (e.g., ‘I would enjoy the sensation of skiing very fast down a high mountain slope’)

Each statement is rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from strongly agree (1) to strongly disagree (4). The sub-scales were recoded such that higher scores represented higher levels of impulsivity.

Statistical Analysis

All data analysis was carried out using IBM SPSS™ 24.0. Correlations were used to examine the association between potential covariates (age, education, sex) and the dependent variable (UPPS-P subscales). Multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) was used to analyze the effect of group on the dependent variables. Bonferroni correction was used in interpreting the follow-up ANOVAs and Games-Howell post-tests were used to make pairwise comparisons between the groups (e.g., bipolar patients vs community controls).

Results

To ensure that the gambling disorder, bipolar, and control populations remained well separated, one bipolar patient who reported gambling during manic episodes was excluded. Similarly, one control participant was excluded for having a family history of gambling disorder. In the final sample, none of the gambling disorder participants suffered from bipolar disorder, none of the bipolar patients suffered from gambling disorder, and none of the controls participants had a personal or family history of problem gambling or bipolar disorder.

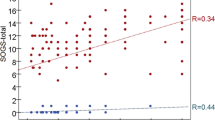

Table 1 shows demographic characteristics and Table 2 shows the comorbid diagnoses for each group. There were significant group differences on age, education, PGSI, SOFAS, HAMD and YMRS scores (Table 1). Education was negatively correlated with positive urgency (r (115) = − 0.24, p = .008) and negative urgency (r (115) = − 0.38, p < .001). Age (r (115) = − 0.19, p = .04) and sex (r (115) = − 0.34, p < .001) were negatively correlated with sensation seeking. However, including age, sex and education as covariates did not significantly change the results. Therefore, the results are presented below without the inclusion of covariates.

Means and standard deviations on the UPPS-P for all groups are shown in Table 3. Multivariate analysis of variance showed there was a significant effect of group on the dependent variables (Pillai’s Trace = 0.61, F (10, 224) = 9.90, p < .001). Follow up ANOVAs (Bonferroni correctted) showed a significant effect for positive urgency (F (2, 115) = 37.79, p < .001, η 2 p = 0.40), negative urgency (F (2, 115) = 36.11, p < .001, η 2 p = 0.38), lack of premeditation (F (2, 115) = 10.47, p < .001, η 2 p = 0.15), and lack of perseverance (F (2, 115) = 12.37, p < .001, η 2 p = 0.18), but not sensation seeking (F (2, 115) = 1.54, p = .220, η 2 p = 0.03).

Games-Howell post hoc tests showed that both gambling and bipolar disorder groups scored significantly higher than community controls on positive urgency, negative urgency, lack of premeditation, and lack of perseverance (p < .01 for all pairwise comparisons). Gambling and bipolar disorder groups only differed on positive urgency, with bipolar disorder patients scoring significantly higher than gambling disorder participants (p = .05).

Discussion

We found that participants with gambling and bipolar disorders had higher scores on positive urgency, negative urgency, lack of perseverance and lack of premeditation when compared to controls. There were no significant differences on sensation seeking. Effect sizes were largest for positive and negative urgency. The gambling and bipolar disorder groups only differed on one dimension—positive urgency—with bipolar patients scoring higher than gambling disorder participants.

Urgency

Higher levels of positive urgency is one of the most consistent findings in gambling disorder (Albein-Urios et al. 2012; Cyders and Smith 2008b; Michalczuk et al. 2011) and bipolar disorder (Giovanelli et al. 2013; Moeller et al. 2001; Muhtadie et al. 2014). Higher negative urgency has also been reported in gambling disorder (Michalczuk et al. 2011) and bipolar disorder (Muhtadie et al. 2014). In agreement with previous studies, we found that gambling and bipolar disorder participants had higher levels of positive and negative urgency when compared to community controls. Our findings further show that gambling and bipolar disorder participants are distinguishable on self-reported impulsivity in that bipolar patients have significantly higher levels of positive urgency than community controls and problem gamblers. The difference between the bipolar and gambling groups is remarkable given that less than half of the bipolar participants met criteria for current bipolar disorder, and all but one bipolar participants were currently on medications. A previous study of medicated inter-episode bipolar patients (Swann et al. 2001a) found that bipolar patients had higher levels of impulsivity when compared to healthy controls, suggesting that impulsivity is a state, as well as a trait-characteristic of bipolar disorder (Moeller et al. 2001).

Impulsive actions in gambling disorder may result from impaired emotion regulation mechanisms (Billieux et al. 2010; Cyders et al. 2010; Michalczuk et al. 2011). Emotional dysregulation has been well-documented in bipolar disorder (Gruber et al. 2011; Talbot et al. 2009) and may affect impulsivity in bipolar disorder, especially with regard to positive emotions (see Muhtadie et al. 2014). In fact, given that bipolar disorder is characterized by extremes of positive emotions (more so than gambling disorder), it is not surprising that our results showed significantly higher levels of positive urgency in bipolar patients.

Lack of Premeditation and Perseverance

Lack of premeditation (Cyders and Smith 2008a) and perseverance (Michalczuk et al. 2011) have been previously reported in gambling disorder. Although they are conceptually related to the symptoms of mania (e.g., foolish business investments, distractibility), this is the first study to report a significant difference on these dimensions of impulsivity between bipolar patients and community controls. Lack of premeditation and perseverance may be related to cognitive/self-control mechanisms (Bechara and Van der Linden 2005; Mobbs et al. 2010; Rochat et al. 2013). Lack of premeditation, in particular, may be the result of dysfunctional decision-making processes (Bøen et al. 2015). This suggests the possibility that these dimensions of impulsivity may respond to cognitive remediation more so than urgency and sensation seeking.

Sensation Seeking

While findings on urgency in gambling and bipolar disorder have been consistent, findings on sensation seeking have been equivocal. While some studies have reported an association between sensation seeking and problem gambling (Cyders and Smith 2008a; Ledgerwood and Petry 2006; Slutske et al. 2005), there have been others which have not found an association (Clarke 2004; Michalczuk et al. 2011), or have even found a negative relationship (Coventry and Constable 1999). No previous studies have investigated sensation seeking in bipolar disorder. Our study found that sensation seeking in gambling and bipolar disorders does not significantly differ from controls. One partial explanation for this discrepancy has been suggested by Bøen et al. (2015) who pointed out that the UPPS is better able to discriminate between sensation seeking behavior that springs from a genuine search for exciting experiences from sensation seeking that results from other factors. For instance, sensation seeking that results from the need to alleviate negative emotions is more likely to be accurately classified as negative urgency by the UPPS questionnaire. An alternative theory, specific to gambling disorder, suggests that sensation seeking may play a role in initial engagement with gambling rather than the development of problematic gambling, and may be less relevant to individuals who have already transitioned to disordered gambling (see Hodgins and Holub 2015; Michalczuk et al. 2011; Prince van Leeuwen et al. 2011).

Limitations

The primary limitation of this study is the small sample size of the bipolar patients. In spite of the small sample size, we found significant differences between bipolar patients and controls on positive urgency, negative urgency, lack of premeditation and lack of perseverance. Despite the small sample size, our findings even showed significant differences between bipolar disorder and gambling disorder on positive urgency. However, given that gambling disorder participants and bipolar patients both have high levels of impulsivity, a larger sample size might be required to identify differences between the two groups on other dimensions of impulsivity.

Conclusions

In the present study, we found that bipolar disorder and gambling disorder participants had higher levels of impulsivity when compared to community controls. We also found that bipolar patients have higher levels of positive urgency when compared to gambling disorder participants. Our findings show that while impulsivity is central to both gambling disorder as well as bipolar disorder, specific types of impulsivity (like positive urgency) may help distinguish between them. Furthermore, some types of impulsivity, like lack of perseverance and lack of premeditation, may be related to cognitive deficits and may therefore be amenable to cognitive remediation. Future research should investigate the relationship between self-reported impulsivity and behavioral measures of cognition, including response inhibition, in disorders where impulsivity is a key feature. A better understanding of how phenomena such as impulsivity presents in gambling disorder and bipolar disorder may help us refine our diagnostic categories and understand underlying transdiagnostic mechanisms.

References

Albein-Urios, N., Martinez-González, J. M., Lozano, Ó., Clark, L., & Verdejo-García, A. (2012). Comparison of impulsivity and working memory in cocaine addiction and pathological gambling: Implications for cocaine-induced neurotoxicity. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 126(1–2), 1–6.

Alessi, S. M., & Petry, N. M. (2003). Pathological gambling severity is associated with impulsivity in a delay discounting procedure. Behavioural Processes, 64(3), 345–354.

Alloy, L. B., Abramson, L. Y., Walshaw, P. D., Cogswell, A., Grandin, L. D., Hughes, M. E., et al. (2008). Behavioral Approach System and Behavioral Inhibition System sensitivities and bipolar spectrum disorders: Prospective prediction of bipolar mood episodes. Bipolar Disorders, 10(2), 310–322.

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM 5. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing.

Bechara, A., & Van der Linden, M. (2005). Decision-making and impulse control after frontal lobe injuries. Current Opinion in Neurology, 18(6), 734–739.

Billieux, J., Gay, P., Rochat, L., & Van der Linden, M. (2010). The role of urgency and its underlying psychological mechanisms in problematic behaviours. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 48(11), 1085–1096.

Bøen, E., Hummelen, B., Elvsåshagen, T., Boye, B., Andersson, S., Karterud, S., et al. (2015). Different impulsivity profiles in borderline personality disorder and bipolar II disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders, 170, 104–111.

Clarke, D. (2004). Impulsiveness, locus of control, motivation and problem gambling. Journal of Gambling Studies, 20(4), 319–345.

Costa, P. T., & McCrae, R. R. (1992). Professional manual: revised NEO personality inventory (NEO-PI-R) and NEO five-factor inventory (NEO-FFI). Odessa FL Psychological Assessment Resources.

Coventry, K. R., & Constable, B. (1999). Physiological arousal and sensation-seeking in female fruit machine gamblers. Addiction (Abingdon, England), 94(3), 425–430.

Currie, S. R., Hodgins, D. C., & Casey, D. M. (2013). Validity of the Problem Gambling Severity Index interpretive categories. Journal of Gambling Studies, 29(2), 311–327.

Cyders, M. A., & Smith, G. T. (2008a). Clarifying the role of personality dispositions in risk for increased gambling behavior. Personality and Individual Differences, 45(6), 503–508.

Cyders, M. A., & Smith, G. T. (2008b). Emotion-based dispositions to rash action: Positive and negative urgency. Psychological Bulletin, 134(6), 807–828.

Cyders, M. A., Zapolski, T. C. B., Combs, J. L., Settles, R. F., Fillmore, M. T., & Smith, G. T. (2010). Experimental effect of positive urgency on negative outcomes from risk taking and on increased alcohol consumption. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 24(3), 367–375.

Dussault, F., Brendgen, M., Vitaro, F., Wanner, B., & Tremblay, R. E. (2011). Longitudinal links between impulsivity, gambling problems and depressive symptoms: A transactional model from adolescence to early adulthood. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines, 52(2), 130–138.

Evenden, J. (1999). Impulsivity: A discussion of clinical and experimental findings. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 13(2), 180–192.

Ferris, J., & Wynne, H. (2001). The Canadian Problem Gambling Index : Final report. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse.

First, M. B., Williams, J. B. W., Karg, R. S., & Spitzer, R. L. (2015). Structured clinical interview for DSM-5—Research version. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association.

Giovanelli, A., Hoerger, M., Johnson, S. L., & Gruber, J. (2013). Impulsive responses to positive mood and reward are related to mania risk. Cognition and Emotion, 27(6), 1091–1104. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2013.772048.

Gruber, J., Eidelman, P., Johnson, S. L., Smith, B., & Harvey, A. G. (2011). Hooked on a feeling: Rumination about positive and negative emotion in inter-episode bipolar disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 120(4), 956–961.

Hamilton, M. (1960). A rating scale for depression. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry, 23, 56–62.

Hodgins, D. C., & Holub, A. (2015). Components of impulsivity in gambling disorder. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 13(6), 699–711.

Kennedy, S. H., Welsh, B. R., Fulton, K., Soczynska, J. K., McIntyre, R. S., O’Donovan, C., et al. (2010). Frequency and correlates of gambling problems in outpatients with major depressive disorder and bipolar disorder. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 55(9), 568–576.

Kessler, R. C., Hwang, I., Labrie, R., Petukhova, M., Sampson, N. A., Winters, K. C., et al. (2008). DSM-IV pathological gambling in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Psychological Medicine, 38(9), 1351–1360.

Kessler, R. C., & Üstün, T. B. (2004). The World Mental Health (WMH) Survey Initiative version of the World Health Organization (WHO) Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI). International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 13(2), 93–121.

Kim, S. W., Grant, J. E., Eckert, E. D., Faris, P. L., & Hartman, B. K. (2006). Pathological gambling and mood disorders: Clinical associations and treatment implications. Journal of Affective Disorders, 92(1), 109–116.

Krueger, T. H. C., Schedlowski, M., & Meyer, G. (2005). Cortisol and heart rate measures during casino gambling in relation to impulsivity. Neuropsychobiology, 52(4), 206–211.

Kwapil, T. R., Miller, M. B., Zinser, M. C., Chapman, L. J., Chapman, J., & Eckblad, M. (2000). A longitudinal study of high scorers on the hypomanic personality scale. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 109(2), 222–226.

Ledgerwood, D. M., & Petry, N. M. (2006). Psychological experience of gambling and subtypes of pathological gamblers. Psychiatry Research, 144(1), 17–27.

Lewis, M., Scott, J., & Frangou, S. (2009). Impulsivity, personality and bipolar disorder. European Psychiatry, 24(7), 464–469.

Lorains, F. K., Cowlishaw, S., & Thomas, S. A. (2011). Prevalence of comorbid disorders in problem and pathological gambling: Systematic review and meta-analysis of population surveys. Addiction, 106(3), 490–498.

Lynam, D. R., Smith, G. T., Whiteside, S. P., & Cyders, M. A. (2006). The UPPS-P: Assessing five personality pathways to impulsive behavior. Wesr Lafayette, IN: Purdue University.

MacKillop, J., Miller, J. D., Fortune, E., Maples, J., Lance, C. E., Campbell, W. K., et al. (2014). Multidimensional examination of impulsivity in relation to disordered gambling. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology, 22(2), 176–185.

McIntyre, R. S., McElroy, S. L., Konarski, J. Z., Soczynska, J. K., Wilkins, K., & Kennedy, S. H. (2007). Problem gambling in bipolar disorder: Results from the Canadian Community Health Survey. Journal of Affective Disorders, 102(1–3), 27–34.

Michalczuk, R., Bowden-Jones, H., Verdejo-Garcia, A., & Clark, L. (2011). Impulsivity and cognitive distortions in pathological gamblers attending the UK National Problem Gambling Clinic: A preliminary report. Psychological Medicine, 41(12), 2625–2635.

Mobbs, O., Crépin, C., Thiéry, C., Golay, A., & Van der Linden, M. (2010). Obesity and the four facets of impulsivity. Patient Education and Counseling, 79(3), 372–377.

Moeller, F. G., Barratt, E. S., Dougherty, D. M., Schmitz, J. M., & Swann, A. C. (2001). Psychiatric aspects of impulsivity. American Journal of Psychiatry, 158(11), 1783–1793.

Morosini, P. L., Magliano, L., Brambilla, L., Ugolini, S., & Pioli, R. (2000). Development, reliability and acceptability of a new version of the DSM-IV Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale (SOFAS) to assess routine social functioning. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 101(4), 323–329.

Muhtadie, L., Johnson, S. L., Carver, C. S., Gotlib, I. H., & Ketter, T. A. (2014). A profile approach to impulsivity in bipolar disorder: The key role of strong emotions. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 129(2), 100–108.

Najt, P., Perez, J., Sanches, M., Peluso, M. A. M., Glahn, D., & Soares, J. C. (2007). Impulsivity and bipolar disorder. European Neuropsychopharmacology, 17(5), 313–320.

Prince van Leeuwen, A., Creemers, H. E., Verhulst, F. C., Ormel, J., & Huizink, A. C. (2011). Are adolescents gambling with cannabis use? A longitudinal study of impulsivity measures and adolescent substance use: The TRAILS study. Journal of studies on alcohol and drugs, 72(1), 70–78.

Rochat, L., Billieux, J., Juillerat Van der Linden, A. C., Annoni, J. M., Zekry, D., Gold, G., et al. (2013). A multidimensional approach to impulsivity changes in mild Alzheimer’s disease and control participants: Cognitive correlates. Cortex, 49(1), 90–100.

Slutske, W. S., Caspi, A., Moffitt, T. E., & Poulton, R. (2005). Personality and problem gambling: A prospective study of a birth cohort of young adults. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62, 769–775.

Steel, Z., & Blaszczynski, A. (1998). Impulsivity, personality disorders and pathological gambling severity. Addiction, 93(6), 895–905.

Swann, A. C., Anderson, J. C., Dougherty, D. M., & Moeller, F. G. (2001a). Measurement of inter-episode impulsivity in bipolar disorder. Psychiatry Research, 101(2), 195–197.

Swann, A. C., Dougherty, D. M., Pazzaglia, P. J., Pham, M., & Moeller, F. G. (2004). Impulsivity: A link between bipolar disorder and substance abuse. Bipolar Disorders, 6(3), 204–212.

Swann, A. C., Dougherty, D. M., Pazzaglia, P. J., Pham, M., Steinberg, J. L., & Moeller, F. G. (2005). Increased impulsivity associated with severity of suicide attempt history in patients with bipolar disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry, 162(9), 1680–1687.

Swann, A. C., Janicak, P. L., Calabrese, J. R., Bowden, C. L., Dilsaver, S. C., Morris, D. D., et al. (2001b). Structure of mania: Depressive, irritable, and psychotic clusters with different retrospectively-assessed course patterns of illness in randomized clinical trial participants. Journal of Affective Disorders, 67(1–3), 123–132.

Swann, A. C., Lijffijt, M., Lane, S. D., Steinberg, J. L., & Moeller, F. G. (2009a). Increased trait-like impulsivity and course of illness in bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disorders, 11(3), 280–288.

Swann, A. C., Lijffijt, M., Lane, S. D., Steinberg, J. L., & Moeller, F. G. (2009b). Severity of bipolar disorder is associated with impairment of response inhibition. Journal of Affective Disorders, 116(1–2), 30–36.

Swann, A. C., Pazzaglia, P., Nicholls, A., Dougherty, D. M., & Moeller, F. G. (2003). Impulsivity and phase of illness in bipolar disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders, 73(1–2), 105–111.

Swann, A. C., Steinberg, J. L., Lijffijt, M., & Moeller, F. G. (2008). Impulsivity: Differential relationship to depression and mania in bipolar disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders, 106(3), 241–248.

Talbot, L. S., Hairston, I. S., Eidelman, P., Gruber, J., & Harvey, A. G. (2009). The effect of mood on sleep onset latency and REM sleep in interepisode bipolar disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 118(3), 448–458.

Vitaro, Frank, Arsenault, Louise, & Tremblay, R. E. (1999). Impulsivity predicts problem gambling in low SES adolescent males. Addiction, 94(4), 565–575.

Whiteside, S. P., & Lynam, D. R. (2001). The five factor model and impulsivity: Using a structural model of personality to understand impulsivity. Personality and Individual Differences, 30(4), 669–689.

Young, R. C., Biggs, J. T., Ziegler, V. E., & Meyer, D. A. (1978). A rating scale for mania: reliability, validity and sensitivity. British Journal of Psychiatry, 133(11), 429–435.

Acknowledgements

The current study was funded by the Gambling Family Study of Clinical and Cognitive Functioning (Alberta Gambling Research Institute Grant 68) and Cell Membrane Alterations in Bipolar Disorder: A Neuroimaging, Peripheral Lipid, and Cognitive Biomarkers Study (Hotchkiss Brain Institute/Pfizer Award). Dr. Goghari was funded by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research New Investigator Salary Award.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethics Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the University of Calgary Conjoint Faculties Research Ethics Board and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Shakeel, M.K., Hodgins, D.C. & Goghari, V.M. A Comparison of Self-Reported Impulsivity in Gambling Disorder and Bipolar Disorder. J Gambl Stud 35, 339–350 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-018-9808-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-018-9808-5